“While composing these Sonatas I thought especially of beginners and of those amateurs who, on account of their years or of other business, have neither patience nor time enough to practice much,” writes Bach toward the end of the famous preface to the publication of his Sechs Sonaten fürs Clavier mit veränderten Reprisen (Berlin: George Ludewig Winter, 1760). “Apart from giving them something easy I wanted to provide them with the pleasure of performing alterations [Veränderungen] without having to resort either to inventing them themselves or to getting someone else to write them and then memorizing them with much difficulty.”1

But the argument put forward in its opening paragraph is of a different kind. Concerned less with the pragmatics of the thing than its theoretical underlay, it interrogates current practice, and unwittingly sets a mirror to the relationship between composer and performer. Here is the full text of that familiar paragraph:

It is indispensable nowadays to alter repeats. One expects it of every performer. A friend of mine goes to endless trouble to play a piece as it is written, flawlessly and in accordance with the rules of good performance; how can one not applaud him? Another, often pressed by necessity, makes up by his audacity in alteration for the lack of expression he shows in the performance of the written notes; the public nevertheless extols him above the former. Almost every thought is expected to be altered in the repeat, irrespective of whether the arrangement of the piece or the capacity of the performer permits it. But then it is just this altering which makes most hearers cry Bravo, especially when it is accompanied by a long and at times exaggeratedly ornate cadenza. This leads to much abuse of those two true ornaments of performance! Such players have not even the patience to play the notes as written the first time; the overlong delay of Bravo is unendurable. These untimely alterations, an annoyance to most composers, are often quite contrary to the grammer, contrary to the affect and contrary to the relation of one thought to another. Even granting that the performer has all the qualities required for altering a piece as it should be done, will he also at all times be so disposed? Will not unknown pieces present him with new difficulties? Is not the main purpose of alterations to reflect honorably on both the performer and the piece? Should he not therefore produce ideas at least as good the second time? Despite these difficulties and the abuses mentioned, good alterations keep their value always. For the rest, I refer the reader to what I said on this subject at the end of the first part of my Versuch [über die wahrer Art das Clavier zu spielen].2

Often reprinted and commonly cited, Bach’s preface is itself an indispensable document, both for what it tells us about the composition of these sonatas as a response to praxis and, much to my purpose here, for what it suggests of a dialectic of sonata in 1760, wherein the act of composition is itself to be understood as a kind of performance: composer and performer as Doppelgänger, the composer as player, the performer as composer. A dialectic of composition and improvisation is embedded here as well. However we think to read Bach’s text, it cannot be dismissed as a plain and easy caveat to the performer. There is something deeper in it.

For one, there is the question of improvisation. What, precisely, is meant by it? If the answer seems self-evident at the outset, by the end of Bach’s preface the distinction between the “composed” piece and these Veränderungen that the performer improvises has been narrowed appreciably. “Oft sind diese unzeitigen Veränderungen wider den Satz, wider den Affect und wider das Verhältniss der Gedanken unter sich,” Bach writes, exposing the composer’s abiding fear of mis-reading in the hands of the performer. What is at stake here are the actual notes, the substance, the guts of the work, and more, for Bach worries about the disposition of the performer, who must somehow manage to affect—to wear, as though in mask—the temperament of the composer in the act of composing this music: “Gesetzt aber, der Ausführer hat alle nöthige Eigenschaften, ein Stück so, wie es seyn soll, zu verändern: ist er auch allezeit dazu aufgelegt?” Here, the boundary between composition and performance is imperceptible. Performance in its deepest sense is understood not as an imitation of the creative act or as a recreation, but as creation itself. In Bach’s account, the act of Veränderung is an extension of the primary act of composition. Indeed, there is a permanence to these alterations—“good alterations keep their value always”—that elevates them to a sphere beyond the ephemeral, and suggests that they belong now to the work in a defining, textual sense.

There is of course another issue here, having to do with the friction between the rituals of what is commonly called “performance practice” and the epistemology of a new rhetoric of sonata. When Bach writes “wider den Satz, wider den Affect und wider das Verhältniss der Gedanken unter sich,” he is protecting the integrity of the work. More than that, these sonatas—each in its own way—explore how the imperatives of large-scale binary form, historically ingrained, in which the two divisions of the work are to be repeated literally, might be deployed in the service of this new rhetoric. The idea of development, of narrative unfolded in a sequence of events, abhors literal repetition, and yet the historical legacy of such repetition is powerfully inscribed as an axiom of instrumental form. There is a conflict, then, between these axiomatic repetitions and the scripting of a new narrativity that together forge in sonata a genre that will dominate music through the death of Schubert.

How, then, can these varied reprises be said to be indispensable (unentbehrlich)? Written into the text of the music, they are made so by the act itself. And if in some instances one wants to speak of “variation” in the commonplace sense as mere decorative cover, the cumulative function of these variants is of greater substance. The drama of sonata engages the imperative of repetition. The variant is made an event of significance.

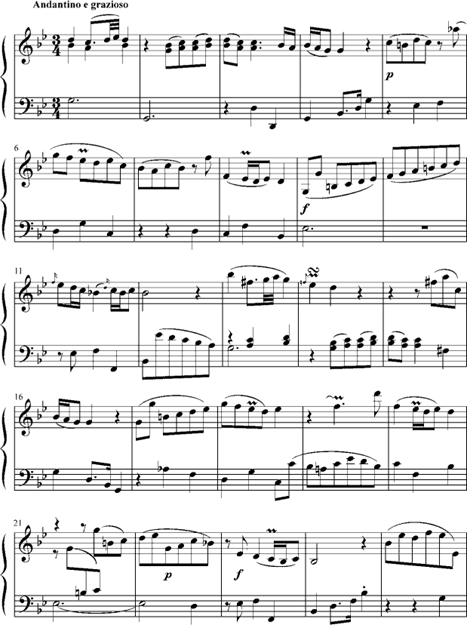

These issues are played out with microcosmic intensity in Bach’s Kurze und leichte Klavierstücke mit veränderten Reprisen, first published in two sets in 1766 and 1768.3 In the “Andantino e grazioso” from the second set, the subtle unfolding of its thematics is made to depend upon Veränderungen of high sophistication. (The complete piece is shown in ex. 3.1.)

The compression of form in the Andantino intensifies the affect of the Veränderungen, which consequently come to stand for something more than the embellishment of thematic archetypes. Heard in retrospect through the prism of the Veränderung starting at m. 13, the very opening of the piece seems distracted, so many wisps of phrase in search of a theme. At m. 13, the incise that marks this first repetition, a true theme comes. The music originally in the treble is rendered subordinate. The repetition of mm. 9–10, whose harmony is a first inversion triad, is bolder still. Here, at m. 21, the striking intervallic figure is intensified, isolated in a momentary flare of imitation. But there is more to this salient gesture, for the figure has been anticipated in the thematic continuation of the verändert opening phrase: the phrase at m. 17, analogous to m.5, recollects the figure first heard at m. 9. And so the music of m. 21 is significant both as an intensification of its analogue at m. 9 and as an echo, formally misplaced, at m. 17. Finally, the figure is embedded in the continuation of the phrase in m. 22, forcing a change of harmony on the third beat, itself an alteration of a higher order.

EXAMPLE 3.1 C. P. E. Bach, Kurze und leichte Klavierstücke mit veränderten Reprisen, II (1768), no. 2 (H 229).

A recapitulation of sorts begins at m. 33, where a sense of return, tentative and fragmentary, is suggested in the motivic detritus of the opening bars, as though to point up the fragility with which the piece begins. And just as the varied reprise at m. 13 formulates something of thematic substance from the barren opening bars, so, too, does the music at m. 49, the analogue to m. 33, play upon this process. The figure isolated and made prominent in m. 21 now becomes the principal thematic agent. Finally, its telling interval is expanded to a diminished seventh and augmented in its temporal dimension in the bass at mm. 53–55: verändert to conspicuous purpose.

Picture for a moment how the piece would go if written in the conventional mode, with double bars and repeat marks. By the assumptions set forth in Bach’s preface to the sonatas of 1760, this unvaried form and the published version with its Veränderungen are two versions of a single piece. The variants written out here, exemplary though they may be, constitute but one permutation of a staggering number of possible alternatives. Apprehended minimally as Veränderungen, we have then to contend with the composer, through whose agency these varied reprises—and none of the imaginary alternatives—have purpose. The very meaning of the piece hinges upon a process of thematic discovery—of revelation. There is a continuity in the process of the piece. Return the piece to its state of innocence before the Veränderungen, and we feel ourselves in the presence of a draft, an Entwurf, of a design yet incomplete.

The exercise of Veränderung in the Sonatas of 1760 is rigorous and complex, and from it emerges an idea of sonata whose essence will survive the specificity of 1760. Whatever else we might learn from these sonatas, the actual practice of varying the reprise of the exposition—the playing through of Bach’s reprise—induces the expectancy that the second half will of necessity be subject to the same mode of Veränderung. This is not a question of symmetry, but again of thematic engagement, of process. Not that each and every Veränderung in all six sonatas is of a quality and import to bolster a claim for indispensability, for the teleology of narrative, for the celebration of event. Some are merely decorative, perhaps even didactic. They do not evidently contribute to the work as Sonata in the new sense in which it was coming to be defined.

Others do, insinuating themselves into the fiber of the piece, now subtly and imperceptibly, now aflame in the rhetoric of the form. In Sonata VI (H 140)—a single movement of the “double variation” type (tonic minor, tonic major)—these distinctions are exhibited in sharp clarity. Veränderungen, by formal definition, are deployed at three levels: in the internal phrase structure of the theme itself; in the conventional bipartite repetitions of the closed formal “frames” of the theme; and in the subsequent repetitions of the entire theme. There is a sense in which the return of the opening theme in C minor, following upon the new music in C major, is made to feel like the da capo after the trio, this in turn followed by a reprise of the trio (and the da capo) a second time. Unlike the seriate process of the conventional “tema con variazione,” the sonata movement puts great emphasis on the recall of event and the signals of closure.4

EXAMPLE 3.2 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C minor, H 140.

The most emphatic of these signals comes, logically, at the very end (see ex. 3.2). A newly inflected harmony at the third beat of m. 228—a diminished seventh that signals a dominant ninth on C—sets things off. Struck fortissimo, its tones gripped in two hands (the only such éclat in the piece), the music erupts for an instant, violating the formal constraints of Veränderung. The descending sixths and the solitary B♮ in the bass play on this moment in the theme itself (see ex. 3.3). By simple parsing, mm. 230 and 231 are interpolations. The form is perfectly respected when they are omitted. But that is not how the passage is heard. Rather, the B♮ in m. 230 fails to move as all its predecessors have moved. Its repetition at the lower octave in m. 231 is the lowest note in the piece, and very nearly in the entire set. In somber isolation, sounded just this once, it invites all the burr and Bebung that Bach’s clavichord would bring to it. Too soon (as Bach shrewdly calculated) the right hand breaks in, peremptorily striking the highest note in the piece, from which the figure in big intervals descends.

EXAMPLE 3.3 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C minor, H 140.

The second part of Theme II trades in similar intensifications. The deployment of the figures, the spacing of the intervals, is suggestive even in the first instance (mm. 64–72; ex. 3.4A). At the repetition of these bars (mm. 78–86; ex. 3.4B) expression is wrung out of each interval: the drooping third is inverted to a vaunting sixth, and the lower register is more firmly delineated in the process; in the answering dyads, diminished sevenths are now formed, with implications as dominant ninths. The sheer tactile pleasures of the music are exploited in a dizzying counterpoint of displaced accents. At the first iteration in the da capo (mm. 156–164; ex. 3.4C), each alteration touches the music in minimalist gestures that again exercise the physical act of performing. The registral reversal in the answering phrase is “felt” in the echoing dyad at the precise middle of m. 159, where the two hands argue against the slur. Stunningly, the three diminished intervals earlier sounded at the expiration of a slur are here articulated in distinct isolation, each now inflected with the flatted ninths that imply roots even as they displace them in affective dissonance, now in three real voices, and fortissimo.

The rhetorical incision of Veränderung speaks out in the first movement of Sonata I (H 136; Wq 50/1). This is perhaps most evident in its final bars, one of those characteristic passages in Bach’s sonatas that negotiates between one movement and the next. It is worth noting how the music at the close of the movement dissolves (see ex. 3.5). This bare fifth, faintly sounded at the downbeat of m. 47, has to do with liquidation. It is an effect of paradox and deception. All good sense grasps the simple harmonic facts here: the E is not the harmonic fifth above a root A, but rather, an appoggiatura that displaces the F above it, while the A must be understood as the third degree, here inverted beneath the displaced root. And yet the disposition of these tones deep in the bass repudiates this commonsense view, for the emptiness of the harmony incites a purely intervallic hearing, and so, too, does the motion of the bass to the lower F, suggesting a brief patch of austere counterpoint in pure intervals.

EXAMPLE 3.4 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C minor, H 140.

EXAMPLE 3.5 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F major, H 136, first movement.

The moment is further striking because it grows directly out of the music of mm. 44–45—is more precisely a nearly literal repetition, at a lower octave, of one of the figures embedded in this passage. And even though the interval between the two tones of the fifth at the downbeat of m. 45 is greater by an octave, we emphatically do not hear these tones as anything other than the suggestion of a tonic triad in first inversion.

The figure that guides this passage is itself a Veränderung (see ex. 3.6). In relation to its prototype, the figure is incisive, conveying a deliberate intensification of expression. Intervals are widened and hollowed out, the descending seventh an evident commentary on the sixth with which the piece opens. Dissonances are prolonged. A connectedness emerges—nothing more salient, perhaps, than a linking of intervallic peaks in a high register: the high G in mm. 20 and 21 leading the ear to the climactic A at m. 22. By analogue, the Veränderung at mm. 44–45 ought to have established a high C at precisely this point, a transposition of the motive at m. 21. The B♭ in its place, as dissonant (implied) seventh, refusing the move up by step to the high D, seems instead to hang suspended. In the continuation of music after the formal cadence in m. 46, we hear why. The B♭ in this highest register now inspires a descent (illustrated in ex. 3.5): not, emphatically, a descent toward linear closure, but a descent to the F as a dissonance within the augmented sixth at the cadence that opens into the Largo.

EXAMPLE 3.6 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F major, H 136, first movement.

Such relationships, born of the practice of Veränderung, are about composition in its deepest sense. Without them, the piece is flat, its story untold. It would be a very short story indeed: in its formal brevity, the movement seems to have been conceived so that its thematic fullness is actually dependent on the varied reprises.

In among a folder of loose leaves marked on its cover “Veränderungen und Auszierungen über einige meiner Sonaten” is a page in Bach’s hand with a set of alterations for the second movement, the Largo, of Sonata I: “Erster Theil der Reprisen Sonaten, ex F, pag. 2,” Bach wrote at the top of the page, referring to the pagination in the Winter publication.5 These are not the only “Veränderungen und Auszierungen” that Bach wrote for the various movements of the sonatas in this collection (and, as well, in the two collections called “Fortsetzungen” that Winter published in 1761 and 1762 as sequels to the Reprise Sonatas). For reasons that remain obscure, the variants for the Largo were not entered into the Handexemplar (a working copy) of the Winter publication, now at the British Library, into whose margins Bach entered variants for movements from the Sonatas III, IV, and V.6

The variants in the Handexemplar have recently been the subject of lively dispute. Etienne Darbellay, in his 1976 edition of the Reprise Sonatas, actually incorporated all these Veränderungen into the principal text, understanding them precisely as revisions toward a “Fassung letzter Hand.”7 In an inquiry into the entire range of Bach’s revisions, Darrell Berg argues from a broader perspective: such Veränderungen were meant by Bach “to serve as alternatives rather than replacements.”8 Viewing the matter from another angle, Howard Serwer argues compellingly that the Veränderungen in the Reprise Sonatas were motivated by an endeavor to discourage an unauthorized reprint by Johann Karl Friedrich Rellstab.9

If true, Serwer’s hypothesis might be thought to substantiate Darbellay’s claim that these variants were intended by Bach as replacements. Instead, it merely complicates the matter, suggesting as it does that Bach’s revisions were motivated not out of a sense that the sonatas of 1760 were, some twenty-five years later, in need of revision, but rather that a new version would legitimate the author’s proprietary claims on these works. To have established Bach’s motive—if that is what Serwer has done—is to have reasoned only the first cause for having set pen to paper. Such reasoning leaves unexamined Bach’s actual engagement with the process of Veränderung.

The Largo, in its two versions, is a study in the complexity of this dialectic, wherein the plain speech of an original conception defers to an enhanced rhetoric. What is the relationship between them? Is the one demonstrably an improvement upon the other, meant to supersede it in some textual hierarchy? If that were not the intention, we must then ponder whether the Veränderung means to gather its meaning in juxtaposition with the prototype from which it emanates: to ponder, that is, whether the two constitute a single conception—two alternatives for performance. (The two versions are shown in ex. 3.7.)

There are good grounds for understanding the new music as considerably more than a varied alternative to the original. In its new fluency of diction, the Veränderung can be thought to realize the expressive potential of a movement otherwise awkwardly constrained, even mute. Consider, for example, the music at the new incise beginning at m. 14. The iterated Cs, rhythmically enlivened, seem now to probe and to clarify the very similar music beginning at m. 5—whose original rhythm, now complicated in the Veränderung, is in a sense reclaimed in the revision at m. 14.

Most impressive of all is the elegance of the new m. 20: how it sweeps up the first three notes of the bar into a rhythmic figure that transforms the rote repetition of the original Lombard rhythm into a moment of pure expression, reaching back to the intervals and the figure of the new mm. 15 and 17, and at the same time, rehearing the new rhythms of mm. 5 and 6. The lithe unfolding of the Neapolitan at the end of the bar, in its simple arpeggiation to the high D♭, is very fine.

In that same folder of unpublished “Veränderungen und Auszierungen” is a variant reading of the moving Molto adagio, a soliloquoy in eight ample bars that negotiates between the lean, sinewy outer movement of the Sonata in C minor, H 127 (Wq 51/3). Its opening phrase—a phrase that never returns—sings the plaintive figure of some lonesome cavatina. Precisely its second interval, the fall from the E to the A, is the subject of the second incise, beginning at m. 5. For once in the pages of this folder of “Veränderungen,” Bach writes out the entire movement in all its voices. The autograph portrays a confident and supple hand that never once stumbles through its thicket of thirty-second and sixty-fourth notes. (It is reproduced as fig. 3.1.) The chaste opening phrase is made a subject of inquiry, its expressive intervals salted with new dissonance, its rhythms intensified, its harmonies enriched. Even the opening anacrusis, the solitary G whose gruppetto launches the phrase, is renotated: the eighth note is replaced by two sixteenths, tied (see ex. 3.8A). If the two versions of the anacrusis will sound imperceptibly the same in performance, the variant nevertheless inspires new thought. How, we ask, are the two sixteenths to be made audible? What nuance of performance can make these two tones distinct? The notation sets us to thinking, and this abstruse process of mind will somehow be conveyed in performance—even if it is only the solitary performer, alone with his clavichord, who will notice. The striking B♭ in the Veränderung that interrupts the clean fifth E—A in the soprano in m. 1 is now invoked at the incise beginning at m. 5, in an arpeggiation that mordantly stresses a dissonant B♮, the A then inflected by B♭ three times, in two registers, before the end of this plenteous measure (ex. 3.8B). Again, the Veränderung is no mere embellishment. It speaks to the gist of the music.

EXAMPLE 3.7 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in F major, H 136, Largo, with Veränderungen.

FIGURE 3.1 C. P. E. Bach. Veränderung for the Molto adagio from Sonata in C minor, H 127. © Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin–Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv. Mus. Ms. Bach P 1135, fol. 9. By kind permission.

This Sonata in C minor, published by George Ludewig Winter in 1761, is the third in a volume titled Fortsetzung [continuation] von Sechs Sonaten fürs Clavier von Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach—misleadingly titled, one must say, for those anticipating another set of sonatas with varied reprises would have found such Veränderungen only in the first movement of the fifth sonata. But the first sonata in the collection—Sonata in C major, Wq 51/1—was subjected to a broader, external process of Veränderung in an instance that must be unique in the entire repertory. At some point after its appearance in Winter’s print, Bach was inspired to rewrite the entire sonata twice: “2 mal durchaus verändert,” Bach notes against its entry in the Nachlaßverzeichnis.10 The manuscript conveying these later variants bears an inscription on its cover in Bach’s hand: “die erste Sonata aus der Fortsetzung meiner Reprisen-Sonaten 2mahl durchaus verändert.”11 (For the sake of convenience I speak here of three distinct sonatas, identified by their numbers in the Helm Thematic Catalogue: H 150 [= Fortsetzung]; H 156, H 157.) These two later versions were not published during Bach’s lifetime. Nor can we ascertain with any precision when they were written.12 Why were they written? Why did Bach single out this sonata for extensive Veränderung, and then subject it to the same process a second time? A deeply ingrained pedagogical calling is evident here, and so is the compulsive need to exhaust the resources of Veränderung. Are they adequate to an explanation why Bach went to considerable lengths to write out the entire sonata two times, in effect recomposing as he wrote?

EXAMPLE 3.8 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C minor, H 127, Molto adagio.

Again, we confront an apparent confusion of purpose, the pragmatics of pedagogy faced off against the deeper impulse of Veränderung at play in Bach’s creative imagination. Perilously difficult to discriminate in this or that instance, the two phenomena seem ever at odds in Bach’s decision-making. If by some critical measure we might be inclined to understand either or both of these later versions as recompositions superseding, intentionally or not, the sonata published in 1761, we’d need to remind ourselves that all three sonatas comprise precisely the same number of measures in each of their three movements and in all of their parts. A template of syntactical identity implicates an underlying deep structure, the three sonatas collapsed into a single one.

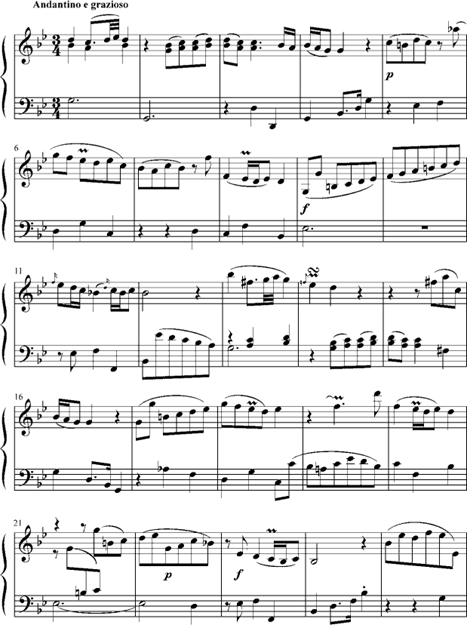

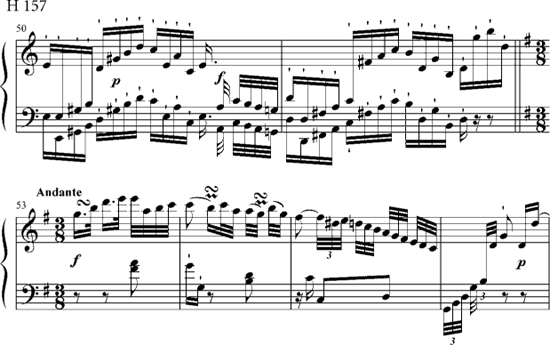

The locked-tight grip of these constraints must have set loose an impulse to break away, to compose with freer hand. Several passages in particular are worth contemplating in this regard, and will have to stand in for a good many others. The first is the music that negotiates between the end of the first movement and the beginning of the second (see ex. 3.9). A bumpy, baroque-like sequencing and a full stop before the upbeat to the Andante, common to both H. 150 and 156, are refused in H 157. The new music of mm. 50–51, complex in registral layering, now dwells on dominants, picking out its pitches with an ear to nonclosure. The final three notes, no ordinary anacrusis, formulate something motivic, a figure drawn from the complex arpeggiations that precede it. It will imprint itself on the music that follows.

EXAMPLE 3.9 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C major, in three versions; final bars of first movement, opening bars of second.

Indeed, the opening bar of the Andante establishes a sense of theme that differs radically from its predecessors. The initial G, a dissonant appoggiatura in H 150 and H 156, is now set loose, responding to the new motivic impetus through which it is prepared. A tempo is established in relation to the Allegro moderato of the first movement, whose final sixteenths fix a kind of tactus that controls the complex new rhythmic contour of the Andante. However one thinks to play those final sixteenths of the first movement, the temptation to crescendo through them to the forte at the downbeat of the Andante is hard to resist. These notes actually play into the Andante, so that the one seems to emerge from the other.13 Finally, a new thematic figure is established at m. 5 subtly tuned to the shape of those final sixteenths before the Andante. The figure imprints the movement with a bold sense of articulation, its recurrences at mm. 29 and 47 opening up intervallic spaces that simply do not exist in the earlier versions (see ex. 3.10; m. 47 not shown). Its profile is felt even in the exquisite final bars of the movement.

Again in these final bars (shown in ex. 3.11), the sense of the three sonatas as simple variants in synchrony with one another is pointedly challenged. These are the five bars of music with which the Andante avoids its final cadence, moving off to the dominant of C in preparation for the final Allegro. And yet to apprehend the three writings of this passage as a chronicle in which the symptoms of a new attitude are registered, a new style augured, is to conjure an old parable in the historical imagination. How, then, to explain the conceptual leap in H 157: the solitary E♭ in the bass at m. 52; these austere harmonies; the fine voicing of the diminished seventh above the C in m. 54, the empfindsame augmented sixth, fortissimo, at the end of m. 53? Perhaps it is in the recognition of something here beyond the expression of words, a music finally in need of interpretation, that we identify in this second Veränderung the symptom of a music of another kind.

In her pioneering study of the “Veränderungen und Auszierungen” that is our general topic, Darrell Berg concluded that on the evidence, “Bach intended [the entire corpus of variant versions] to serve as alternatives rather than replacements… .Surely, in any case, they were to be applied at the pleasure of the performer and not to be regarded as mandatory alterations.”14 This is a temperate, cautious reading. And yet it leaves unexamined a tension that continues to sound well beneath the surface of the music, where the composer is glimpsed, however obscurely, doing battle with himself in an unforgiving process of reflection, of criticism. Veränderung and Auszierung, we must remind ourselves, are not synonyms. It is a commonplace to hold that when Bach subjects a piece to embellishment, he sustains a venerable practice that has more to do with the ephemera of performance than with the fundamental decision-making of composition, a practice very close to the ancient notion of diminution. But Veränderung, while it may encompass the practice of Auszierung, means something else again. When, in the final bars of the Andante in H 157, the music strips away all diminution to home in on harmonies and inner voices, the process engaged is critical, creative in some higher sense. No handbook of embellishment can contain it. The sense of the passage in H 157 is not heard as a “reading” of the passage in H 150—does not depend on it for its meaning.

EXAMPLE 3.10 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C major, from the Andante.

EXAMPLE 3.11 C. P. E. Bach, Sonata in C major, in three versions, Andante, final bars.

To return once again to those unanswerable questions posed earlier, one might venture to think that Bach went to such lengths to write out two completely altered versions of H 150 because publication in Winter’s Fortsetzung made irrevocably public a work that Bach now felt to be less inspired—less original, less exemplary of an idiosyncratic Einbildungskraft (a characteristic imagination) than its companions. To write down the sonata twice more is in a sense to undo the published version. Did Bach intend, by this act, to replace the sonata in some categorical textual sense? The material permanence of the Winter print argues against such a view, even as the evidence marshaled by Howard Serwer regarding a putative revision of the first volume in the Winter series allows that Bach may indeed have contemplated a revised edition of the Fortsetzung as well. But then one must ask why Bach admitted all three versions, without further discrimination, into his catalogue as a single sonata “2 mal durchaus verändert.”

These are troubling contradictions, but they seem to me perfectly normal ones. “Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the Restless Composer”: in her provocative title, Rachel Wade hints at some interior compulsion underlying the complex and manifold processes of alteration that Bach imposed upon his works. “Bach was restless because he was a perfectionist,” she concludes.15 Surely, there is ample evidence in support of this view of the man. Perfection, however, is illusory in the arts, an abstraction invoked both as an attribute of the work and, in metaphor, as the critic’s yardstick. Wade perhaps means by it nothing more than the modest notion of grammatical correctness. By that measure, one might contend that each of the three versions of the Sonata in C is “perfect” by the criteria implicit in each. But perfection has its discomforting aspect. In the leap from H 150 to H 157, impatient with the limiting “perfection” of the original conception, Bach writes music that now challenges its limits, that strains the very notion of perfection. Certainly, there is a compulsive aspect to Bach’s enterprise, situated in this obsessive self-criticism that Wade means to identify, and made manifest across the wide range of compositional projects that consumed Bach during a very long career.

In these Veränderungen, one senses the playing out of some inner crisis, perhaps only vaguely intuited, in the conceptualizing of sonata, bound up with a shift, paradigmatically, in the idea of Veränderung itself, from the notion of inexhaustible variation, an aesthetic comfortably at home in the music of an earlier generation, toward a firmer control of diction, of gesture and feeling, and of narrative. The function of variation is redefined. No longer the decorative embellishing of structure, variation now infiltrates to thematic bedrock. When Bach renders an original work in subsequent Veränderungen, he puts on public display a process that will have its echo in the private pages of the Beethoven sketchbooks, where a sequence of drafts suggestive of a process at once evolutionary and dialectical enacts a similar rush of decision-making, even while the formal matrix that regulates the process for Bach is now sprung. For Beethoven, the act of Veränderung penetrates to form itself, and to the constraints of genre.