The business of elections should be seen as a marathon, not as a sprint race.

—Dr. Kimmo Kiljunen, Special Envoy of the Organization of Security and Co-operation in Europe1

THE PREVIOUS CHAPTER found that good elections are more likely when monitors are present. However, this says nothing about whether improvements are sustained. Nor does a focus on single elections make it possible to explore whether, despite several persistently bad monitored elections, improvement may occur in the long run. To examine this, it is necessary to research individual countries over longer periods of time. No study has ever systematically compared how several countries respond to recommendations by monitors in the long run, and whether the overall quality of elections improves throughout multiple monitored elections. That is what this chapter does.

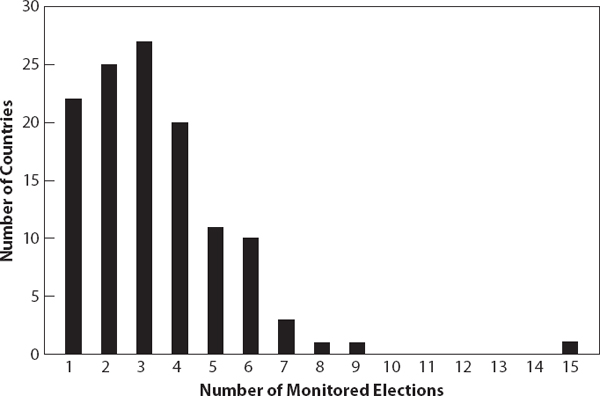

A long-term perspective is important for several reasons. First of all, changes often take time. Second, international election monitoring is rarely limited to a single election experience in a country. Most countries that invite monitors do so more than once; several do so repeatedly and over many years. The Dominican Republic, for example, has one of the longest histories; monitors first observed elections in 1978 and attended eight more elections between 1990 and 2004. Figure 8.1 shows the number of countries that had multiple elections monitored between 1975 and 2004. (Serbia is the outlier country, with fifteen monitored elections.2) This repeated engagement makes it compelling to also consider possible long-term outcomes over numerous elections in a country.

Indeed, most monitoring efforts aim not simply to deter overt cheating in a single round of elections, but to bring changes in the long run. This is one reason many organizations invest considerable time on the ground. More than half of monitored elections have at least one pre-election visit by an organizational delegation, and in about 40 percent of elections at least one organization arrived a month or more in advance. Most important, international election monitors usually include many recommendations in their reports. These recommendations call attention to current problems in the legal and administrative framework for elections and often make concrete suggestions about how to address them. For example, monitors may note that the current law inadequately addresses election finance issues and suggest a process of overview. Or they may recommend that a country adopt a particular form of voter identification, or revise the ballot-counting system. They may also make specific legal recommendations about the electoral system itself, for example, about the selection and composition of the electoral commission, or about ways to eliminate systematic disenfranchisement of certain voters. Often they also make recommendations about how to improve the transparency of the election process or offer suggestions on how to achieve a smoother administration of the balloting.

Figure 8.1: Number of countries with multiple monitored elections, 1975–2004

As discussed in Chapter 6, the long-term activities of international election monitors may be able to improve elections by exposing domestic politicians to important norms and practices of competitive elections and by reinforcing the expectations of the international community. And although it is likely to be harder for monitors to facilitate change in countries with very low administrative capacity, they may be part of the solution to building new capacity and skills. This chapter considers whether there is any evidence that this actually works by examining the long-term engagement of monitors in several countries in depth. Does the long-term engagement of monitors show results in countries over time? What factors condition their effectiveness? What does a long-term focus on countries reveal about the ways that international election monitors may influence election conduct?

It is of course possible simply to look at the trajectory of the quality of elections in monitored countries over time. Such an overview suggests that about half the countries that have hosted monitors at some point in time have improved at least some since monitors first arrived, but that in about half of these countries huge problems persist. Overall, this says very little about whether monitors have helped these countries to improve their elections.

Rather than merely looking at trends, the goal of the country studies is to systematically examine the response of various countries to monitors’ recommendations over time. Such analysis can show when monitors had no effect, and it can highlight instances when monitors may have had an effect. However, they cannot definitively prove that monitors caused any of the changes, because changes in election quality may have several causes that are difficult to disaggregate. However, studying the details of the recommendations and the actions countries take can make the causal role of monitors more or less plausible. Moreover, in some cases there is evidence of fairly direct connections. The substance of the changes may align quite specifically with the recommendations of monitors. There may also be testimony that the recommendations played an active role in the reforms. In Armenia, for example, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) continued to work with officials on the recommendations in its 1996 final report. In follow-up meetings with the chairman of the Standing Committee for State and Legal Affairs, the chairman said he was leading a group to draft a new law and that International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) personnel were present at all the meetings. He noted that each of the OSCE recommendations was being discussed during the drafting of the new law.3 Similarly, after Russia’s 1993 referendum, the vice chairman of Russia’s central election commission (CEC) said that the International Republican Institute (IRI) report “served as the roadmap for the CEC in making improvements in the election law.”4 Eighteen of the twenty recommendations related directly to election law were adopted partially or substantially.5

The country case studies therefore provide context and continuity that improve inferences about the effects of monitors. Importantly, they can suggest factors that may condition the influence of monitors—something this chapter discusses extensively. The case studies can also highlight alternative factors that may be driving the changes within countries. For example, in the case of Bangladesh, a caretaker government installed after a domestic crisis in 2007 implemented an impressive round of reforms. Many of these aligned with prior recommendations of international monitors, but the monitors could hardly take all the credit. The practical situation had made the reforms painfully necessary and domestic groups also were pushing hard for them.

Because the country studies rely on information from multiple election visits and explore long-term effects, it is most useful to examine countries with well-documented long-term experience with monitors. If monitors only began to visit a country recently, for example, or if documentation was only available for one election, it is harder to learn anything from the case. Choosing countries with a long-term engagement with monitors does not by definition mean that the countries are more likely to have failed to respond to monitoring. Indeed, in the time span of the study, few countries ever “graduated” from monitoring, meaning monitors entirely stopped visiting their elections. Even some of the European countries have continued to receive monitors after their democratic credentials were well established. For example, the OSCE monitored Bulgaria in 2009. Thus, most countries continued to receive monitors even if their elections improved considerably. Therefore, repeated visits do not mean that the country by definition has not improved. Still, the selection of cases clearly is not random. This is not a big problem, however, because the purpose of the case studies is not to determine how often the presence of monitors and election improvements are associated, as in the previous chapter. Rather, the purpose is to identify the factors that may influence whether countries follow monitor recommendations in the long run and to examine how plausible it is that monitors are part of the reason changes occur.

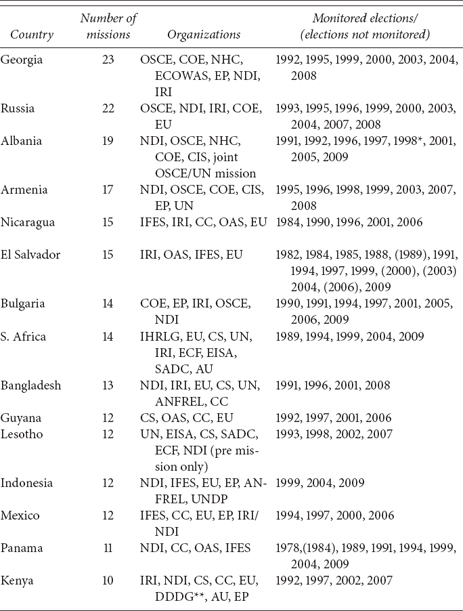

About twenty countries had sufficient documentation and interest to be selected for in-depth study. Of these, fifteen were selected to create a sample that was regionally diverse and varied on several dimensions such as population size, income, geopolitical status, ethnic composition, and electoral systems. Table 8.1 shows the cases included, the number of monitoring missions, the elections attended by international observers, and the organizations involved in each country.

For each country, all the reports were read with special attention to recording the recommendations made and the performance in subsequent elections. Sometimes information on a given prior recommendation was missing in subsequent reports. Secondary sources were then consulted, but it was not possible to track down relevant information, and in such cases it was not possible to draw any conclusions on those particular issues. For each case, a table was created to keep track of recommendations over time. In most elections, the recommendations were too numerous and extensive to be logged individually, and therefore larger categories were often used. Based on this research, detailed individual country case studies ranging from six thousand to ten thousand words were written. Country experts were asked to comment on the cases. Appendix E summarizes each of these case studies.

Note: For abbreviations, see page xix.

* Constitutional referendum.

**Donors Democratic Development Group.

The cases are not complete accounts of the political developments in a country. Rather, they distill insights about electoral conduct and the role of international monitors in improving specific aspects of elections in a country. Including so many cases favors breadth over depth. This no doubt sometimes forfeits some detail and accuracy, but it offers a cross-national comparison that can yield more general insights.

The case studies underscore that the engagement of international monitors in a country is very much a long-term project. Seldom are the recommendations of monitors implemented immediately, although it does occur. After Russia’s 1993 referendum, for example, the IRI documented that “a number of IRI’s suggested improvements were adopted by the time of the December 12, 1993 parliamentary elections.”6 In Panama, the Carter Center (CC) called for fairer regulation of access and use of printed media in 1994, and by the 1997 election this had been adopted. And sometimes monitors make recommendations after pre-election visits and are able to prompt changes in time for the election. More commonly, however, monitors point to weaknesses in the electoral process repeatedly before any changes occur. Often changes are only partial. In Albania, for example, the IRI and National Democratic Institute (NDI) recommended increased independence for the electoral commission in 1991. Partial improvements occurred by the 1995, 2001, and 2005 elections, but by 2009 the OSCE was still criticizing the institutional setup.

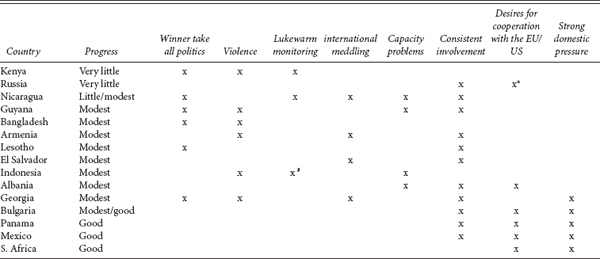

As Table 8.1 shows, in several cases monitors have been involved for multiple elections, sending numerous missions, yet the improvement in the quality of elections has been minimal. In Kenya and Russia, despite temporary improvements, elections continue to be highly problem-filled. Nicaragua’s electoral administration has remained mired in political battles. As Table 8.2 shows, this does not mean that there have not been areas of success. Kenya, for example, altered regulations permitting electoral rallies and where to conduct the counting, and Russia did accomplish several legal reforms, just as Nicaragua made some administrative and logistical improvements. What is striking about these countries, however, is that, even after so many monitoring missions, progress has been quite limited and regression has occurred. As the CC noted about Nicaragua, “Repeated recourse to international election observation even after national organizations have developed a demonstrated capacity to fulfill their role should be a cause for concern.”7 Thus, a country such as Kenya may have held a marginally better election in 2002, but as the 2007 election demonstrated all too sadly, in the longer term such single-election gains do not necessarily translate into better elections in the long term.

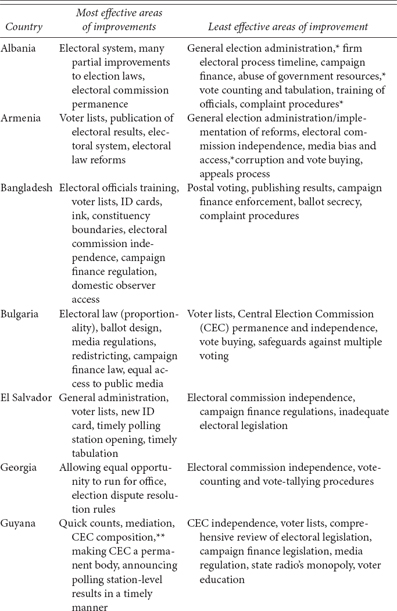

TABLE 8.2

Least and most effective areas of improvement as of 2009

*Improvement, then deterioration.

**Some improvements occurred, although not independence.

#Some improvements.

## Russian election observation reports from 2008 and 2009 by the Council of Europe do not cover many of the issues of past reports, making it difficult to know the actual state of practice and legislation.

In yet other countries, including Armenia, Guyana, El Salvador, Bangladesh, Lesotho, Indonesia, Albania, and, perhaps, Georgia, despite intermittent gains, the overall progress has been modest. Of course, one can quibble about categories such as “little” versus “modest,” and indeed they hide considerable variation: Georgia has clearly made greater improvements than Armenia, for example. In these countries, however, monitoring organizations have on several occasions expressed satisfaction that the countries had addressed some important monitor recommendations. These often included important amendments to electoral laws, as in Albania and Armenia; improvements to voter lists, as in El Salvador and Bangladesh; de-politicization and independence of the electoral commission, as in Guyana and Bangladesh; or improvements in vote counting and tabulation procedures, as in El Salvador. Thus, some success has occurred.

However, in these countries the progress was often offset by evasive implementation or, even if meaningful, by failures to follow other equally consequential recommendations. The case studies in Appendix E thus show that many of these countries continued to exert influence over the electoral commissions, control the media, maintain poor voter lists, and repeat many other problems that clearly had the capacity to change the outcome of the election. Indeed, it is notable that such problems as electoral commission independence and voter lists seemed particularly resistant to monitor influence.

Although it is possible to point to several instances of specific reforms that monitors encouraged in various countries, only four of the fifteen countries made and maintained significant overall progress. These are South Africa, Mexico, Panama, and Bulgaria. In addition, Bangladesh also made significant progress in 2008, but this progress has not yet been tested in subsequent elections. Elections in these countries are by no means perfect now—Bulgaria being perhaps the most problematic with some backsliding after the nation joined the European Union (EU) and no longer had to be as careful to assure admission. Thus Bulgaria still struggles with faulty voter lists, lacks a permanent and independent central election commission, suffers from vote buying, and lacks safeguards against multiple voting. Yet these countries have all made major strides since the onset of international election monitoring, and have, perhaps with the caveat about Bulgaria, sustained their progress in the most recent election. Notably, South Africa, Panama, and Mexico have all tackled the sensitive—but central—issue of electoral commission independence and conduct. They have improved their voter lists, and Panama and South Africa have vastly improved their administrative procedures. Progress in these cases has thus been notable, but the case studies also suggest that international election monitors played only a supportive role in this progress. In South Africa, for example, the main international influence was through the independent electoral commission, not election observers. In Mexico, domestic actors clearly played the central role.

Table 8.2 summarizes some of the least and most effective areas of improvements in these countries over time. The table is illustrative, not exhaustive. It highlights instances where the information is reasonably clear and where improvements have been noticeably present or absent. In many other areas these countries have made partial changes that could be characterized as the cup being half full or half empty, depending on one’s perspective.

In either case, as the above discussion suggests, countries sometimes do address monitor recommendations, but often the quality of elections nevertheless remains highly problematic because the countries still have not addressed many important concerns or new problems crop up. Furthermore, in some cases, even with as many as twenty-two monitoring missions, as in the case of Russia, there is little international monitors can actually do to improve the election in meaningful terms. In several cases, such as Armenia and Albania, international monitors may face a paper compliance problem: they may have extensive influence over the legislative framework, only to find problems in implementation.

Furthermore, the cases herein also demonstrate that changes often do take very long. Even in Mexico and Bulgaria this has been the case. Few countries show as rapid progress as Panama and South Africa, and when progress does occur, the main role of international monitors usually is to reinforce domestic actors.

The country variation discussed above and elaborated further in the case study summaries in Appendix E raises the question of which factors influence the effectiveness of international monitors. What factors facilitate their influence and what factors hinder it? The rest of this chapter turns to this discussion.

Chapter 6 discussed several factors that may diminish or strengthen the influence of international monitors. In the previous chapter we saw that there was indeed some support for the argument that high-quality monitors are more effective than low-quality monitors. The case studies make it possible to look more closely at some of the remaining conditions.

Several countries that struggled to progress shared two characteristics: violence and a winner-take-all political system that leave little voice for election losers. Indeed, this combination is probably one of the biggest obstacles to progress. Kenya, Guyana, Bangladesh, and Georgia all fall in this category. With only a slight lull in 2002, ethnic violence has dominated the Kenyan democratization process, and incumbent leaders and their followers benefited economically and politically from continuing unrest and the dysfunctional institutional and political environment. The Kenya African National Union (KANU), representing the numerous Kikuyu and Luo ethnic groups, were long able to use majoritarian laws to exclude other ethnic groups from power.8

In Guyana the transition has similarly been hampered by deep, historic, ethnic divisions that solidified into the main cleavage between political parties, accompanied by violence as the primary tool for resolving differences. The People’s Progressive Party (PPP), which represents the more sizable ethnic Indian population, has won all four elections in Guyana since the end of authoritarianism in 1992. Because the constitution gives the winning party the very powerful presidency, the losers fear exclusion from decision making and are therefore always prepared to challenge the outcome.9 This has led to a series of disputed elections. Thus, Guyana has been stuck in a recurrent pattern of voting along ethnic lines, poor administration of elections, and violent electoral aftermath.

In Bangladesh, the bitter rivalry between the two major parties, the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), has been fueled mainly by the personal rivalry between their dynastic leaders. Politics has remained focused on political families, laudation of party history, and vague promises of economic growth and social stability. This has produced a pattern where the ruling party refuses a meaningful role for the opposition, the opposition walks out, and society is paralyzed by strikes and boycotts.10 This constant rivalry long paralyzed Bangladesh’s ability to improve the electoral process.

In these cases, violence and winner-take-all systems and mindsets have made it very difficult for international monitors to be heard, as following their recommendations would tend to open political competition further. As mentioned earlier, in Bangladesh international monitors were sometimes able to help persuade the opposition to accept defeat,11 but only the crisis and caretaker government in 2007–8 was able to break the pattern somewhat and bring substantial reforms. As the Guyana case summary discusses, in Guyana only the most recent election has shown a reason for hope. Kenyan elections, unfortunately, have remained mired in ethnic conflict.

In Georgia a slightly different situation has played out, although it shares the characteristics of violence and political deadlock. The continuing tension in South Ossetia and Abkhazia has hampered Georgia’s democratic transition. At the same time the tone between opposing parties has been excessively confrontational. According to the OSCE, the lack of political dialogue often resulted in complete inattention to any opposition demands, leaving the impression that there was a lack of political debate. This concern was most recently voiced following the 2008 constitutional reform plebiscite. In reality this meant that the political process came to a halt and no reforms were implemented.

An extreme winner-take-all system that frequently leads to massive riots has also hampered the effectiveness of international monitors in Lesotho. The contest has not been about ethnicity or ideology—Lesotho is ethnically homogenous—but about competition for jobs,12 because of “the high premium placed on being in government.”13 However, a combination of a heavy-handed response from South Africa and extensive involvement by the South African Development Community (SADC), as well as the Commonwealth Secretariat (CS) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), has been able to promote some administrative changes to the election process as well as important changes to the electoral system. Nevertheless, even the new proportional representation system has produced deadlock as the parties have found ways to evade its true intent by forming coalitions to evade the rules. The domestic battles over the electoral system have distracted from other reforms that monitors have suggested over the years. Thus, abuse of government resources continues, media still require regulation, and Lesotho has repeatedly ignored monitors’ recommendations regarding campaign finance regulation.

These examples illustrate that it is extremely difficult for international monitors to influence election quality in winner-take-all systems, particularly when violence is common. The stakes are too high for the parties to adapt recommendations that may lessen their chance of holding on to power, the recurrence of violence distracts from political substance, and the political deadlock makes it difficult to pass reforms. In contrast, cessation of violence may give monitors, or other international actors, a window of opportunity, as in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and even South Africa.

Another factor that can diminish the influence of monitors is their own unwillingness to push very hard or be explicit in their criticisms. As Chapter 5 discussed, international monitors may tone down their criticisms for several reasons, ranging from fear of conflict to political pressures. In some of the selected case studies the lack of effectiveness can be partly traced to halfhearted monitoring efforts. In particular, it is striking that it was apparent in two of the worst cases, Russia and Kenya.

The lackluster performance of Russia in terms of improving the quality of elections surely cannot be attributed solely to the weak efforts of international monitors. Far greater forces, such as increased centralization and concentration of power in the Kremlin likely controlled events. However, international monitors have been quite timid in their approach to Russian elections.14 As a result, they were useful and welcomed by Russian politicians in the first years after transition when they brought legitimacy and were fairly hesitant to criticize officials. In these years there were even some signs of apparent success as Russia followed several recommendations to improve the election law, as discussed in the case summary in Appendix E.15 In these years, international monitors were willing to give Russia the benefit of the doubt and to encourage the transition despite difficulties. For example, monitors were rather hesitant in their criticisms of the 1996 Russian election although Boris Yeltsin abused state resources, manipulated the media, and repressed the opposition.16 The international monitors remained optimistic through the 2000 presidential election, arguing that “it marked the conclusion of a transitional period forged by President Yeltsin since 1991.”17 The more critical message that Vladimir Putin had consolidated his power fell on deaf ears. Even since then, after Russia made observation so difficult that the OSCE chose to stay away, remaining groups such as the Council of Europe (COE) have had a hard time articulating just how bad Russia’s system is. Thus, after the 2008 election the COE noted that the election was “a reflection of the will of an electorate whose democratic potential was, unfortunately, not tapped.”18 The report is very critical, but such a statement reveals profound ambiguity.

In Kenya the dilemmas of international monitoring organizations and their subsequent ambiguity in assessing the elections has also circumscribed the leverage of international monitors. Chapter 3 already discussed how President Daniel arap Moi responded to international pressure in the early 1990s and began to dismantle the one-party system, and how he orchestrated interethnic violence to divide the opposition along ethnic lines19 and used other fraudulent practices.20 Criticism was nevertheless muted.21 After ethnic clashes Moi suspended the new Parliament for about six weeks and gained the upper hand. However, just a year later the international donor group resumed aid to Kenya, citing the positive economic and political reforms. The lesson for Moi and other Kenyan politicians: Attending to the recommendations of international monitors is not really required. The 1997 election was essentially a repeat of this pattern.22

In Indonesia monitors have suffered from excessive optimism. The international monitors put in strong efforts in 1999 and 2004, only to drop the ball in 2009. After massive efforts in the early elections, international monitoring organizations such as the EU appeared eager to assume that the world’s largest Muslim democracy was on track. Thus, in 2009, only the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) returned in full force. The CC sent a “limited observation mission.”23 Yet, many of the problems that monitors had pointed out in the 1999 election were still present ten years later. The lackluster showing of monitoring groups for the 2009 election suggests that international election monitoring organizations have been too quick to assume progress and ease their pressure on the authorities to reform.

In some elections the behavior of other countries has made it difficult for international monitors to address problems. In these case monitors may have appeared unsuccessful, but in reality powerful countries meddled in the politics and restricted their effectiveness. In Nicaragua, for example, the United States, due to its past support of the Contras, the counterinsurgency movement that opposed the Sandinistas, continued to actively support the Conservative Party of Labor (PCL) after 1990, while the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) drew support and funding primarily from Venezuela.24 The foreign involvement persisted and reached a new high in 2006, prompting the CC to state, “Attempts by foreign countries to influence Nicaragua’s election outcome reached a depth and visibility unmatched since 1990. While the U.S. government once again maneuvered to unify the Liberal forces to thwart a comeback by Daniel Ortega, Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez came to Ortega’s aid as a key ideological ally.”25 In practice, both parties resisted reforms to prevent other factions from competing. In Nicaragua, domestic struggles between political strongmen were the greatest hindrance to reforms. However, the larger-scale opposing support for different sides by external actors also made it harder for monitors to press for reforms.

A similar tale can be told about El Salvador. After the 1991 election, the United Nations (UN), USAID, and several other international actors were heavily involved in resolving issues in order to consolidate the peace. However, throughout the 1990s the incumbent Alianza Republicana Nacionalista (ARENA) was able to shrug off most of the monitors’ criticisms and indeed their presence altogether, as the international community focused more on the success of the peace agreements and the continued holding of passable elections than on pushing hard for improvements. Improvements began with the presidential election in 2004. These changes and the changes in 2009 were brought about by the gradual erosion of support for ARENA—domestically as well as internationally (by traditional supporters such as the United States). With 2009 bringing consecutive elections for Parliament and president, the attention of the international community refocused and the efforts to address longstanding criticisms made by the international monitors increased.

Russia has sometimes played a similarly interfering role. In Armenia, the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh crippled the economy in the mid-1990s, wiping out 85 percent of the country’s trade after Azerbaijani security forces blockaded its railroad system.26 Importantly, the blockade also increased Armenia’s dependence on Russian military assistance. Thus, while the incentives for democratization from the West were amorphous, Russian influence in the military and economy was tangible and strong, and diminished much of the impact of the legislative reforms that international monitoring organizations such as the OSCE had a clear hand in pushing through.

Thus, international monitors sometimes play second fiddle to other international actors intent on meddling in domestic affairs. If these meddlers favor reforms, then the monitors gain strong backing and leverage. If not, their efforts are curtailed.

Capacity is a catch-22 problem. If countries lack basic elements of election infrastructure and struggle simply to get ballots printed, to distribute materials, and so forth, it will also be harder for them to follow the recommendations of international monitors—especially those recommendations pertaining to capacity issues. Of course, nearly all of the countries in Table 8.2 have struggled with lack of capacity at some point, but some much less than others. For example, Panama’s fast economic recovery and large service-based industry enabled the government to react to administrative recommendations and implement sophisticated computerized vote counting systems. Such resource availability facilitates the influence of international monitors by making it easier for governments to follow up with implementation.

In several other countries, such as Lesotho and El Salvador, lack of capacity was very debilitating in the early years, but showed some improvement. In some cases, however, a capacity deficit does present a significant barrier to effective reforms. In Guyana lack of capacity has several times contributed to actual postponements of the scheduled polling date. As discussed in the following chapter, Guyana has struggled with issuing voter ID cards on time and officials have struggled to cope with their duties. Elections have been disastrous in so many respects because the extremely low administrative capacity could not keep up with legislative reforms and requirements. This poor capacity has been one of the reasons monitors’ effectiveness in improving the administration of elections in Guyana has been modest.

In Indonesia, capacity problems also loom large: With more than 171 million voters and half a million polling stations, the challenges in organizing singleday elections in such a vast and poor country are enormous. It is perhaps no wonder that it has been difficult to get accurate voter lists. Indonesia has also struggled to adequately train enough polling officials, to implement automated tallying systems, and to address other logistical issues. Voter education has been another continually lagging area of performance in an environment of low civil society capacity.27 Despite massive international financial assistance, in such a vast, poor country, capacity is an enormous practical barrier to progress.

However, capacity problems cannot take all the blame. In Albania, for example, the inability to administer elections and enforce reforms has been closely related to lack of capacity, in terms of infrastructure, as well as logistical and institutional deficiencies. These problems were most evident in the early period, but persist due to underdevelopment of the country. In 1997, the collapse of a fraudulent investment scheme brought the country to the brink of economic collapse and prompted the UN Security Council to authorize humanitarian assistance. The monitors repeatedly note, however, that at the core, Albania’s failure to meet international election standards is not foremost about capacity, but a matter of lack of political will. Thus, lack of administrative capacity does make it harder for monitors to get governments to implement reforms, but monitors could possibly also be part of the solution to rectifying capacity problems.

Theory about political conditionality suggests that international election monitors should be able to assert greater influence when the country wants to cooperate with the West somehow. This was evident in several cases.

In Russia the greatest opening was between 1994 and 1999, when Russia received substantial International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans.28 This period also saw the greatest improvements in the electoral framework and administration of elections. This period also coincided with Russia’s efforts to join the COE. Indeed, the “generally positive” evaluation of the 1995 election led to the recommendation for Russia’s admission.29 Of course, the downside of this conditionality mechanism is that backsliding may occur, as indeed it did in Russia and in Bulgaria, another case where the desire to join the EU most surely allowed the international monitors greater influence.

Mexico’s participation in the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development allowed greater international influence over that nation’s democratization process, as Mexico needed to be perceived as stable to maintain vital international investment.30 The improvements in Albania’s 2009 election also came after repeated admonition of repercussions for Albania’s relationship with European organizations. Before the 2009 election, the EU clearly stated that the election would be seen as a litmus test for Albania’s democracy.31 And of course, in South Africa the very decision to hold elections where all could participate in 1994 was predicated on intense international sanctions.

EU conditionality also played an important role in Bulgaria, where the EU used a bottom-up approach to democratization through election assistance.32 Opposition parties used progress reports issued by organizations like the European Commission to discredit the government during the mid-1990s. The activities and approval of the OSCE and COE were important mechanisms for gaining entry to the EU. Thus, conditionality was a “benign yet effective tool of democracy promotion.”33 More problems resurfaced, however, when Bulgaria no longer faced the conditionality incentives derived from the pre-accession criteria put forward by the EU. It remains to be seen whether the robust backlash by Bulgarian media, which extensively covered vote buying practices, will manage to resolve the problems that surfaced in 2009.

In other cases the importance of conditionality is illustrated by its absence. Regarding Armenia, the COE was too concerned about security to use the leverage of admission to press for reforms. Instead, the COE hoped that admitting both Armenia and Azerbaijan would promote peace between them. But after admitting Armenia in 2000, the COE lost much leverage. Although the COE was still joining the OSCE in efforts to push for legal reforms, the list of changes that the COE had considered as a matter of urgency prior to admission in the organization focused primarily on legislation to improve human rights violations.34

As discussed in Chapter 6, the prevailing theme in the international democracy promotion literature is the pre-eminence of domestic factors.35 Thus, domestic factors should also influence the effectiveness of international monitors. This is clearly the case. Several countries show that domestic pressures for reforms help international monitors promote better elections. This factor is not only important, but probably also necessary. In cases where the international community has pushed strongly for elections without domestic preparedness, such as in Kenya, efforts have backfired. Certainly the international community was no match for overcoming the strong antidemocratic pressures in Russia given Russia’s low level of civil society development.36 Lesotho’s population has been among the least enthusiastic supporters of democracy in African opinion polls,37 and the current deadlock is therefore not so surprising. Nicaragua’s lack of progress is likewise mired in domestic troubles.

If the willingness to undertake meaningful reforms is absent, there is not much monitors can do. As the old saying goes, “You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink.” Thus, even if Armenia has invited advice from international monitors and followed several of their legal recommendations, implementation has been lacking, and the reforms have had little real effect, prompting the OSCE to hint that the authorities are not taking the concerns seriously.38 In Indonesia numerous unfavorable domestic conditions have hampered the ability of monitors to improve the administration of elections, such as political power struggles, endemic corruption, terrorism, poverty, the impeachment of the president in 2001, the insurgency in Aceh, and the tsunami in December 2004 that claimed 169,000 lives.

The importance of domestic pressures is clearest in the most successful cases such as Mexico and Panama. In Panama, the ability of monitors to work with the domestic opposition and the Catholic Church to organize a parallel vote count was highly influential in discrediting the 1989 election and bringing on the American invasion that brought the opposition to power. Starting in 1999, Panama’s electoral process was deemed to be of very good quality.39 Other important domestic conditions have been its fast economic recovery and large service-based industry, which have enabled the government to react to administrative recommendations and implement sophisticated computerized vote counting systems.

In Mexico, domestic factors also drove the political opening and transformation. The CC was particularly adroit at using the domestic political opening to gain access. Domestic observer groups and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) deserve most of the credit for the tremendous transformation of Mexican elections since 1988, but international observers such as the CC were instrumental in building up this domestic capacity.40 Not only did they help form these national groups and train them, but they also facilitated their visits to observe elections in the United States.41 The CC sent missions, offered advice, and exposed central Mexican civil society activities to experiences overseas to bolster their capacities to build domestic observation.42 However, it was because of domestic mistrust prior to the 1994 election that the government decided the election had little chance of being viewed as legitimate without international monitors. Furthermore, together with domestic actors, international observers placed campaign and party finances on the political agenda and encouraged the government to permit a televised debate between the main presidential candidates.43

Similarly, the marked decrease in post-election violence in Guyana after the 2006 election was driven not only by the presence of monitoring efforts, such as the violence reporting by IFES,44 but by widespread efforts by domestic politicians to appeal for calm and peace and condemn violent methods. And in Georgia, any role that the monitoring organizations were able to play in the historic Rose Revolution rested on the dramatic domestic mobilization.45

Indeed, in some cases the domestic impetus for change has been so strong that monitors played only a small, complementary role. For example, the international community played a large role in bringing South Africa’s 1994 election about, but already by the next national election in 1999 the government had addressed most of the weaknesses and international monitors faded from the scene. Thus these cases underscore that international monitors tend mostly to reinforce domestic pressures.

Even if domestic conditions play a large role in facilitating the influence of monitoring, the cases also show, however, that even in quite difficult situations such as Armenia, Guyana, and Lesotho international monitors have at least been able to claim some partial successes. In other cases international monitors play some role in helping to create conducive conditions. There is a longstanding debate about the extent to which external players can impose outright reforms on countries.46 However, Panama illustrates that intervention can provide a window of opportunity for democratization. In 1989, monitors helped the NDI and the Catholic Church set up parallel vote counts and legitimize claims that the election had been stolen. This provided former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, who was working with the NDI/IRI joint mission, with enough support to publicly denounce the official voting results.47 It was also at the core of official statements made by U.S. President George H. W. Bush and spurred the Organization of American States (OAS) to denounce the situation in Panama. Thus, it helped pave the way for the 1989 invasion, which permitted a more receptive political environment for monitors in years to come.

Chapter 6 argued that the long-term engagement of monitors might help improve elections by reinforcing the expectation of the international community, teaching and socializing actors, and building capacity and skills. Most of the cases studied did have rather consistent visits by the same monitoring organization(s). However, it is striking how some organizations invest heavily in a mission in a country, making long lists of recommendation, only to fail to show up for the next election. This is more understandable for NGOs that depend on varying funding opportunities. However, intergovernmental organizations(IGOs) also drop the ball at times. Thus, the EU went to Guyana in 2001, but did not return in 2006. The EU likewise went to Indonesia in 1999 and 2004, yet did not return in 2009. The IRI observed election in Nicaragua in 1984, 1990, 1996, and 2001, but did not go in 2006.

That said, the benefits of repeated and continued involvement were evident in cases like Armenia and Albania and even Russia, where the OSCE and the COE in particular were persistent in pushing for legal changes. However, these cases also show that the progress was still modest, so continued engagement was by no means a guarantee of success.

The statistical analysis in the previous chapter showed that internationally monitored elections are more likely to be representative, to be of better quality, and to produce a turnover in power. Isolating a statistical impact on some elections, however, may be possible without monitors really having any sustained influence on the quality of elections and the long-term development of the countries’ electoral institutions. Such analysis may also overlook country-specific factors that do not generalize well across elections, but nevertheless contribute to the quality of elections. To complement this focus on individual elections, this chapter then asked: Is there any evidence that the long-term engagement of monitors improves the electoral process in countries over time? And what factors appear to affect the monitors’ effectiveness?

Expectation of long-term persistent effects is of course a much higher bar to set for evaluating effectiveness. Even if some efforts improve only one election—that is still something. But in reality it is also true that temporary gains may not add up to much, so it is important to examine whether monitoring organizations are able to sustain improvements in the long run. The bottom line is again that the cases illustrate that monitors can indeed strengthen some reforms over time. There are many examples of international election monitoring organizations giving advice that has informed subsequent reforms. In at least four of the fifteen countries the overall quality of elections also improved after multiple rounds of monitoring.

But were the cases discussed in this chapter really representative of election monitoring results in general? It appears reasonably so. The rate of improvements in the case studies discussed in this chapter compares well with a more superficial analysis of all the countries that have been monitored. Such an analysis suggests that about half of the monitored countries displayed little to no improvement in aggregate measures of election quality.48 It should be noted, however, that these aggregate measures often do not register smaller improvements in electoral procedures. In about another one-quarter of countries, improvements occurred since monitors arrived, but considerable problems persist. Importantly, however, about one-quarter of cases showed significant improvements—a rate not that different from the cases in this chapter and much higher than for countries without the presence of monitors.

The country case studies also illustrate many of the mechanisms that Chapter 6 argued monitors use to influence elections. Monitors play a variety of roles, from mediators to confidence builders to legal experts to capacity builders. Furthermore, the case studies confirm that several conditions modify the influence of international monitors. Monitors are more effective in countries that are already progressing toward democracy, and when international monitors are connected with organizations or donors that have something to offer the country. However, monitors are less effective in countries with violent, winner-take-all politics and where domestic capacity is greatly strained.

Thus, overall, the case studies support the central argument in Chapter 6 that international election monitors can play a reinforcement role by building on existing domestic potential and enhancing the effectiveness of other international leverage. Although monitors rarely have decisive influence, this does not mean monitors are inconsequential. That countries have potential for change in and of itself does not guarantee that improvements will happen. Monitoring organizations can increase the likelihood that reforms occur and are implemented.

Unfortunately, the case studies also show that there is ample room for pessimism. In the long term, more countries disappoint than succeed. Reforms often do not have a cumulative effect on progress over time. One good election is not necessarily followed by more of the same kind. This is partly the monitors’ fault: Low credibility and lack of consistency reduce monitors’ effectiveness. Lukewarm monitoring leaves openings for further electoral abuses. International meddling can overrule the efforts of international monitors. But countries also weaken the efforts: Often countries ignore the recommendations of monitors, follow them only partly, or regress. Some successes are very piecemeal: One can identify successful reforms that monitors helped promote, but somehow they do not add up to much better elections over time; the corrections are made mechanically without the entirety of the democratic progress keeping up and problems simply arise in other areas.

TABLE 8.3

Primary factors affecting long-term results

*During the mid-1990s.

#Easing monitoring efforts too early.

The piecemeal progress in many countries is cause for concern. In several cases elections have passed the threshold where monitors say they are acceptable, but in reality the elections continue to suffer from many problems that add up to a messy and problematic process. These are not necessarily patently false endorsements, as discussed in Chapter 5, but in many cases the borderline is ill defined. In these situations, there is a danger that election monitors contribute to a false sense of security: As long as the elections squeeze by in terms of minimum standards, the country can maintain a reputation as democratic.

Still, many reforms, although slow, are significant. As today’s well-established democracies testify, becoming a full-fledged democratic society takes time. Indeed, even the so-called established democracies today are far from perfect, and one need only recall the 2000 U.S. presidential election and the infamous “hanging chads” to see that even longstanding democracies can still have big problems running elections. It is important to recall that, as John F. Kennedy commented on the “gradual evolution of human institutions,”49 change takes time. Countries with little experience in holding proper elections will not conduct perfect elections instantaneously. Thus, the case studies show that at least in some countries, under some conditions, improvements may be slow, but by reinforcing the domestic reform efforts, the activities of international monitoring organizations and their interaction have hastened some reforms as well as informed their substance.50