The Late Paleozoic Ice Age is the only time in Earth history, other than the Neogene, when vegetated land masses were subjected to climate fluctuations associated with extended intervals of polar glaciation.

—Gastaldo, Purkyňová, Šimůnek, and Schmitz (2009, 336)

THE STRANGE CARBONIFEROUS TREES

Our modern rainforests are dominated by flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (pinophytes), both of which are spermatophyte lignophyte euphyllophytes—that is, “seed-reproducing woody leafy trees” in the precise language of modern evolutionists (table 3.1). Like the rainforests in the cool Carboniferous world, our modern rainforests evolved in a cool Neogene world, where the South Pole has been glaciated for 12 million years, since the late Miocene, and the North Pole has been variously glaciated for three million years, since the late Pliocene (table 1.6). However, in stark contrast to the trees in our modern rainforests, the giant trees of the Carboniferous rainforests did not reproduce with seeds (they were not spermatophytes), did not have woody trunks (they were not lignophytes), and did not have large leaves (they were not euphyllophytes). In addition, there were no flowers of any kind in the Carboniferous rainforests—the angiosperms, the flowering plants, would only evolve some 140 million years later in the Early Jurassic.1 To understand just how strange the giant Carboniferous rainforest trees were, we need first to examine the sequence of the evolution of plants on land (table 3.1).

TABLE 3.1 Land-plant lineages of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| EMBRYOPHYTA (land plants) |

| – Marchantiophyta (liverworts) |

| – STOMATOPHYTA (stomate plants) |

| – – Anthocerophyta (hornworts) |

| – – Hemitracheophyta |

| – – – Bryophyta sensu stricto (mosses) |

| – – – POLYSPORANGIOPHYTA (branched-sporophyte plants) |

| – – – – Horneophyta† |

| – – – – TRACHAEOPHYTA (vascular plants) |

| – – – – – Rhyniopsida† |

| – – – – – Eutracheophyta |

| – – – – – – LYCOPHYTA (microphyll-leafed plants) |

| – – – – – – – Zosterophyllopsida† |

| – – – – – – – Asteroxylales |

| – – – – – – – – Drepanophycales† |

| – – – – – – – – Lycopodiales |

| – – – – – – – – – Protolepidodendrales† |

| – – – – – – – – – Lycopodiaceae (club mosses) |

| – – – – – – – – – – Selaginellales (spike mosses) |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Lepidodendrales† (scale trees) |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Lepidodendraceae†: Lepidodendrid scale trees |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Sigillariaceae†: Sigillarian scale trees |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Selaginellaceae |

| – – – – – – – – – – Isoetales (quillworts) |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Chaloneriaceae† |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Isoetaceae |

| – – – – – – EUPHYLLOPHYTA (megaphyll-leafed plants) |

| – – – – – – – Moniliformopses |

| – – – – – – – – Cladoxylopsida† |

| – – – – – – – – – Pseudosporochnaceae†: Wattieza (Eospermatopteris) erianus trees |

| – – – – – – – – Equisetophyta (horsetails) |

| – – – – – – – – – Calamitaceae†: Calamitean horsetail trees |

| – – – – – – – – – Sphenophyllaceae† |

| – – – – – – – – – Equisetaceae |

| – – – – – – – – Filicophyta (true ferns) |

| – – – – – – – – – Marattiales: Marattialean tree ferns |

| – – – – – – – LIGNOPHYTA (woody plants) |

| – – – – – – – – Aneurophytales† |

| – – – – – – – – Archaeopteridales† |

| – – – – – – – – – Archaeopteridaceae†: Archaeopterid spore trees |

| – – – – – – – – SPERMATOPHYTA (seed plants) |

| – – – – – – – – – Lyginopteridales† |

| – – – – – – – – – – Lyginopteridaceae†: Lyginopterid seed-fern trees |

| – – – – – – – – – Medullosales† |

| – – – – – – – – – – Medullosaceae†: Medullosan seed-fern trees |

| – – – – – – – – – Gigantopteridales† |

| – – – – – – – – – – Gigantopteridaceae†: Gigantopterid seed-fern trees |

| – – – – – – – – – Core seed plants |

| – – – – – – – – – – Ginkgophyta (ginkgos) |

| – – – – – – – – – – Pinophyta (conifers) |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Cordaitales† |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Cordaitaceae†: Cordaitean conifer trees |

| – – – – – – – – – – Cycadophyta (cycads) |

| – – – – – – – – – – Gnetophyta (gnetophytes) |

| – – – – – – – – – – [ANGIOSPERMAE (flowering plants) not present in Paleozoic!] |

Source: Phylogenetic classification modified from Kenrick and Crane (1997a, 1997b), Donoghue (2005), and Lecointre and Le Guyader (2006).

Note: Important tree groups are in bold italics; extinct lineages are marked with a dagger (†); major clades are in capitals. The classification given in this table is a phylogenetic one, where the taxa listed are monophyletic clades. In the older literature the reader will encounter non-phylogenetic classifications of plants containing groupings of plants that are now recognized as paraphyletic. To help the reader translate the older plant classifications, here is a helpful list of the major paraphyletic groups that have been used in the past: “Pteridophytes” = non-spermatophyte tracheophytes, “Progymnosperms” = non-spermatophyte lignophytes, “Gymnosperms” = non-angiosperm spermatophytes, “Pteridosperms” = non-core seed plants (“seed ferns”); for discussions, see Niklas (1997) and Donoghue (2005).

Land plants, the Embryophyta, evolved from freshwater filamentous green algae, and it appears that the first tiny land plants emerged from the aquatic world in the Middle Ordovician (Lecointre and Le Guyader 2006; McGhee 2013). The most primitive of the land plants are the marchantiophytes, the liverworts (table 3.1). The oldest known spores and cuticular fragments that are believed to be from liverworts are found in strata dated to the Dapingian Age of the Middle Ordovician (see table 1.4 for the Ordovician Age divisions of the geologic timescale), around 470 million years ago (Rubinstein et al. 2010; Wellman 2010). About 15 million years later, definite proof that the liverworts had evolved comes from fossils of Katian Age of the Late Ordovician, about 453 million years ago (Wellman et al. 2003). These fossils include not just isolated spores but also tissue fragments of the sporangia, the structures that held the spores together in life. Some of these fossil sporangia hold as many as 7,450 spore tetrads together, and the shape of the spherical sporangia fragments suggest that they could have held as many as 95,000 spore tetrads in the living plant. The ability to produce large numbers of spores is considered to be an adaptation to living in harsh terrestrial environments and, apart from the terrestrial strata in which they are found, is further evidence that these fossils were from land plants. Finally, the microscopic ultrastructure of the walls of the spores reveals parallel-arranged lamellae of a type that is found only in the spores of living liverworts, providing further evidence that the plants that produced them were indeed liverworts, the most primitive of the land plants (Wellman et al. 2003; Wellman 2010). Today, these simple liverwort land plants resemble lichen, the terrestrial algal-fungal symbionts that are not really plants, and like lichen, they can encrust rocks or tree trunks.

The liverworts have no roots, no vascular system, no true stomata (these plant structures will be discussed shortly), and are confined to humid environments. The next step in the evolution of land plants was the evolution of the Stomatophyta (table 3.1), plants so named because they possess stomata to regulate gas exchange in dry air. Stomata are openings in the wall tissues of the plant that can be opened and closed by two guard cells; they allow the plant to regulate gas and water vapor exchange between it and the atmosphere around it. It is critical to a land plant (as opposed to a water plant) to prevent as much water loss as possible to the surrounding dry atmosphere of the land regions, and the stomata are key anti-dehydration structures in this effort. The most primitive or least derived members of the stomatophyte clade are the anthocerophytes, the hornworts, and fossil Stomatophytes hornwort spores demonstrate that the stomatophytes had evolved by the Katian Age of the Late Ordovician, about 453 million years ago (Lecointre and Le Guyader 2006).

The bryophytes, the mosses, are more advanced stomatophytes of the hemitracheophyte clade (table 3.1). Both the hornworts and the mosses have upright sporophytes; that is, the sporangium is held up in the air on a thin vertical stem. Upright sporophytes are another adaptation to life in dry air, but it is debated whether this adaptation evolved once in the hornworts and was simply inherited by the mosses, or whether the mosses independently evolved upright sporophytes and thus this adaptation is convergent in the two groups (Lecointre and Le Guyader 2006; for an extensive discussion of convergent evolution in plants, see McGhee 2011). The next step in the evolution of land plants was the evolution of plants with sporophytes that were branched—that is, vertical stems that supported more than one sporangium. These plants are the Polysporangiophyta (table 3.1), which evolved in the Early Silurian. The most primitive polysporangiophytes were the now extinct horneophytes and include the fossil species Horneophyton lignieri and Aglaophyton major from the Early Devonian Emsian Age (for more information about these fossil species, see McGhee 2013).

Following the evolution of plants with erect, multibranched stems, the next step in the evolution of land plants was the evolution of the vascular plants—that is, plants possessing water-conducting tubes that transport water up the stem against the force of gravity. These tubes are called tracheids, hence the name Tracheophyta (table 3.1) for these plants. The tracheophytes also evolved in the Early Silurian, and the most primitive members of the tracheophyte clade are another extinct group, the rhyniopsids, such as the fossil species Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii from the Early Devonian Pragian Age (for more information about these fossil species, see McGhee 2013).

The basal, leafless tracheophytes gave rise to the more derived Eutracheophyta, the first land plants to evolve leaf-like structures. The eutracheophytes are divided into two major clades: the microphyll-leafed vascular plants, the Lycophyta, which have numerous tiny leaves; and the megaphyll-leafed vascular plants, the Euphyllophyta, which have less numerous big leaves (table 3.1). The clade of the tiny-leafed lycophyte plants includes modern-day small club mosses, spike mosses, and quillworts. It also includes the gigantic Carboniferous trees of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. The evolutionary split between the lycophytes and the euphyllophytes appears to have occurred by the Middle Silurian Homerian Age, as fossils of the basal lycophyte species Cooksonia pertoni and Baragwanathia longifolia are found in strata of that age (for more information about these fossil species, see McGhee 2013).

The clade of the large-leafed plants, the euphyllophytes, includes most of the land plants that are familiar to us in our modern world. This large clade is itself divided into two major subclades: the Moniliformopses and the Lignophyta (table 3.1). The clade of the moniliformopses includes the cladoxylopsids, an extinct group of fernlike plants; the equisetophytes, the modern-day horsetails; and the filicophytes, the modern-day true ferns. All of these plants still reproduce by spores and have very little, if any, woody tissue.

The other clade of the euphyllophytes, the Lignophyta, are known as the woody plants as they contain substantial amounts of wood tissue. The lignophytes also evolved “bifacial cambium,” an advanced trait that will be discussed in more detail below. The most primitive or least derived members of the lignophyte clade, the Aneurophytales and the Archaeopteridales (table 3.1), still reproduced by spores, and both groups of plants are now extinct. The more derived lignophytes, the Spermatophyta, evolved the first seeds in the Late Devonian Famennian Age. The evolution of seed-reproducing plants was a major innovation in the geologic history of plants; the implications of this evolutionary innovation in reproductive type will be discussed in more detail below. The last major innovation in plant evolution was the evolution of the flowering plants, the Angiospermae (table 3.1), but that did not occur until the early Jurassic in the Mesozoic Era. Life in the ancient Paleozoic world saw no flowers.

Now let us consider the evolution of trees. Trees are a characteristic adaptation of plants to life on land (McGhee 2011, 2013). Simple plant growth in a two-dimensional plane soon leads to crowding and overgrowth, with one plant shading out another in the competition for light from the sun, the energy source for plant survival. When crowding occurs in the two-dimensional plane of the land surface, the solution is to move into the third dimension above the land surface, to evolve plants with single vertical stems, then branched stems, and then branched stems with leaves—hence the evolution of the Stomatophyta, the Polysporangiophyta, and the Euphyllophyta (table 3.1).

Even now, however, crowding will again become a problem when these types of plants cover the surface of the land. And, just as in human cities when crowding occurs in a region of low buildings, the solution is to move even higher into the third dimension above the land surface—to construct towering skyscraper buildings or, in the case of plants, to evolve trees. The force of gravity has to be reckoned with, and new support structures had to be evolved in order to create a massive central structure, a tree trunk, that rises vertically from the land surface. At some distance above the ground, branches extend out from the tree trunk in order to capture as much sunlight as possible for the survival of the tree and, in order to ensure the survival of the species, to facilitate fertilization and dispersal of the tree’s offspring. All of these structures are heavy, and the tree trunk must be strong enough to support them without breaking or bending. Given these difficulties, one might think that only one advanced clade of plants would successfully evolve a tree. Thus it is astonishing that not one, but no less than nine separate phylogenetic lineages of plants independently, convergently, evolved the tree form, each with its own different solution to the problem of growing a sufficiently strong central trunk structure (Niklas 1997; McGhee 2011). The lycophytes, cladoxylopsid moniliformopses, and lignophytes all separately evolved the tree form in the Middle Devonian Givetian Age. Then the equisetophyte and filicophyte moniliformopses independently evolved the tree form in the Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous. The other four convergently evolved tree forms occurred later in geologic time, after the end of the Paleozoic Era (twice more in the filicophytes, and twice more in the lignophytes) (Niklas 1997; McGhee 2011).

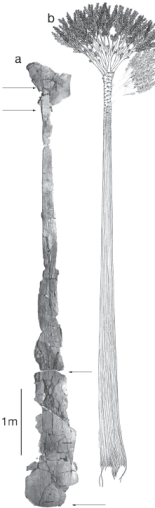

The oldest tree fossils yet known are of the extinct cladoxylopsid Wattieza (Eospermatopteris) erianus trees (table 3.1), found in the famous Gilboa fossil forest in New York State (Stein et al. 2007). These ancient trees stood eight meters (26 feet) tall and looked like thin, tall poles topped with a shaving brush (fig. 3.1)! They had no horizontal branches and no woody tissue—in contrast, the trunk of the tree was probably hollow like a reed. More significantly, down in the understory of the Gilboa forest were other smaller, thin, pole-like trees covered with numerous tiny leaves—the first lycophyte trees, ancestors of the giant Carboniferous trees (Stein et al. 2012).

FIGURE 3.1 The extinct cladoxylopsid-lineage fernlike tree Wattieza (Eospermatopteris) erianus: (a) the reassembled tree fossils; (b) a reconstruction of the living tree. The living tree was about eight to ten meters (26 to 33 feet) tall.

Source: From Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature (Stein et al., 2007), copyright © 2007. Reprinted with permission.

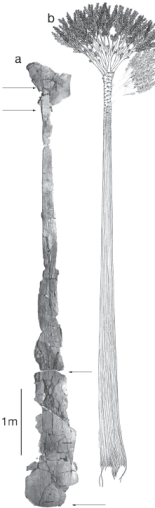

The Gilboa fossil forest is of Givetian Age in the Middle Devonian, and in the later Givetian, the woody lignophytes also convergently evolved a tree form—the archaeopteridalean Archaeopteris (table 3.1). An Archaeopteris tree was much more like the trees that are familiar to us in the modern world (fig. 3.2) in that it had a trunk with a core of heartwood, and it had numerous horizontal branches with leaves. However, it was unlike any modern lignophyte trees in that it still reproduced with spores, not seeds. Unlike the short-lived Wattieza-type cladoxylopsid trees, the Archaeopteris spore trees could tower 30 meters (100 feet) into the sky. Archaeopteris trees became very numerous in the Late Devonian, and by the middle Frasnian Age vast areas of the Earth were covered with Archaeopteris forests. Then, mysteriously, all of the Archaeopteris trees died out in the end-Devonian biodiversity crisis (McGhee 2013).

FIGURE 3.2 The extinct archaeopterid-lineage spore tree Archaeopteris was about 30 meters (100 feet) tall, here compared to a four-meter- (13-foot-) tall male African elephant.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

In the Early Carboniferous Tournaisian Gap (table 2.1), following the End-Famennian Bottleneck, the tallest trees on the Earth were only two meters (6.6 feet) high (DiMichele and Hook 1992; McGhee 2013). The lignophytes had not lost the ability to produce trees, however, and in the later Visean Age of the Early Carboniferous, the first of the lignophyte seed-fern trees evolved (table 3.1), such as the 40-meter-tall (131-foot-tall) Pitus primaeva, discussed in chapter 2. The lycophytes also would begin to produce large trees—the gigantic tropical scale trees—starting in the Serpukhovian Age of the Early Carboniferous (table 2.3).

Having summarized the evolutionary events that led to the origin of trees on Earth, we now turn specifically to the types of trees that were present in the great rainforests of the Carboniferous. Five types of trees were dominant: the lycophyte scale trees, the equisetophyte horsetail trees, the filicophyte tree ferns, the medullosan seed-fern trees, and the cordaitean pinophyte trees (table 3.1) (Pfefferkorn et al. 2008). In that order, let us examine each of these five types of tree in detail. Only the last two tree types were seed plants with woody core tissue like our modern trees—and the first two were unlike any trees alive on Earth today.

The Lycophyte Scale Trees

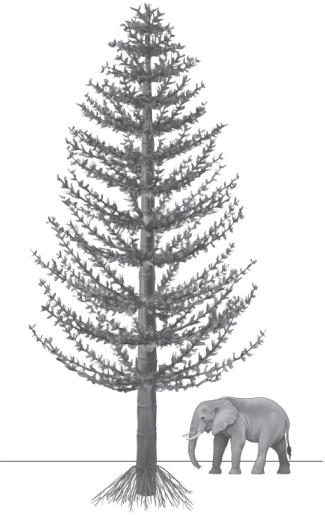

The strangest trees in Carboniferous rainforests—from our modern perspective—were the towering, pole-like lepidodendrid lycophytes (fig. 3.3). First, their gigantic size is difficult to understand. The lycophytes are still alive today, but they are quite small plants. A fairly large modern lycophyte, the stag’s horn club moss Lycopodium clavatum, stands only 12 centimeters (five inches) high (fig. 2.4). In contrast, an average Lepidodendron tree could tower 50 meters (160 feet) into the sky (Cleal and Thomas 2005). How could a lycophyte plant in the Carboniferous grow to be over 400 times taller than any living lycophyte on the Earth today?

FIGURE 3.3 The lycophyte scale tree Lepidodendron was about 50 meters (160 feet) tall, here compared to a four-meter- (13-foot-) tall male African elephant.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

Second, the lycophyte trees had determinate growth, a mode of plant growth that is unusual in plants in our modern world. Consider, for example, the mode of growth of a modern dandelion weed, Taraxacum officinale, in your lawn. For many days the dandelion plant has bladelike leaves that are low to the ground, and eventually it develops a bright yellow flower that is also located low to the ground. Then, suddenly, the plant shoots up a long stem as much as 15 centimeters (six inches) high, crowned with a fuzzy white globe of tufted seeds. This is the seed-dispersal phase in the reproductive cycle of the dandelion in which it elevates its seeds above ground level in order to more efficiently expose the seeds to wind currents that will carry the tufted seeds considerable distances away from the parent plant.

The mode of growth of the Lepidodendron tree was even stranger than that of the modern dandelion: after it reproduced, it died. Like a young dandelion plant, the young Lepidodendron tree grew low to the ground—but for many years, not just for a few weeks. During this time it resembled a low stump, but it was green rather than bark-brown as it was covered with the tiny scalelike leaves of the lycophytes. Below ground, however, it was constantly expanding its peculiar rootlike stigmarian system: in Lepidodendron trees even the stigmarian rootlets could photosynthesize, and they often protruded above ground in order to catch sunlight.

When the Lepidodendron tree reached its reproductive phase, similar to the development of a stem by a dandelion plant, it began to grow a pole-like trunk that stretched into the sky (fig. 3.3). This trunk could reach heights of 50 meters (160 feet) but was quite slender, only about one meter (3.3 feet) in diameter—in essence a thin, towering pole covered with tiny, green, scalelike leaves. As the trunk grew taller and taller, it would begin to shed the leaves in its lower reaches, leaving only the leaf-cushion bases while thickening the trunk. Fossil trunks of these trees are covered with leaf-cushion bases that look like the pattern of scales seen on the body of a snake, hence these trees are often given the common name of “scale trees.” But the scalelike leaf-cushion bases could still photosynthesize—even without leaves—and hence produce food locally on the trunk.

Only when the trunk reached its maximum height would it then begin to produce branches in pairs, drooping on either side of the central trunk, and to develop cones on the branches. Like the upper trunk, these branches were covered with sleeves of leaves, but they were smaller than those found on the trunk. The Lepidodendron tree would then rapidly produce spores in its cones, which would be dispersed by winds at a height of 50 meters above ground level. The tree’s microspores were small and lightweight; thus they could easily be carried by the wind and did not need structures like the tufts of the much larger dandelion seed, which increase the surface area available to catch wind current for support in transporting the seed through the air. After its spores were all shed, the Lepidodendron tree would die. The towering dead trunks of the Lepidodendron trees would remain standing for a while before they began to rot and then, one by one, the great trunks would fall to the swamp waters below.

Astonishingly, the trunks of the gigantic lycophyte trees were not supported by woody tissue like our modern giant trees, such as the giant redwood Sequoiadendron giganteum, which can stand 90 meters (300 feet) high. Most modern trees belong to the clade of the lignophytes, the woody plants (table 3.1). Woody trees possess a bifacial cambium, with secondary xylem tissue toward the center of the trunk and secondary phloem tissue toward the outside (Donoghue 2005). The secondary phloem of a modern woody tree transports food produced by the photosynthesizing leaves in the crown of the tree down to the trunk and underground root regions, and the woody tissue supports the mass of the trunk, branches, and photosynthetic needles or leaves against the downward pull of gravity.

In contrast, the trunks of the lycophyte trees were constructed in a most peculiar manner. They had only a unifacial cambium with no secondary phloem. Without secondary phloem, the tree could not transport food and nutrients for long distances; thus the tree developed photosynthesizing structures—tiny leaves and even the bases holding the leaves—all over its branches and trunk to provide living tissues with food that was locally produced. Even the peculiar stigmarian rootlike tissues of the tree could photosynthesize food. Thus, unlike modern woody trees with food production confined to the crown of the tree with its photosynthesizing leaves, the lycophyte tree produced food over just about its entire surface (Donoghue 2005).

The unusual growth mode of the trunk of the lycophyte tree was probably due to the absence of secondary phloem and lack of sufficient woody tissue to support the trunk against the force of gravity. The weight of the tree was held up by an outer layer, called the periderm, of cortex and leaf bases—in essence, the external bark of the tree, rather than an internal wood core, was its structural support. The trunk of the tree was produced only when it was needed, in the reproductive phase, when the spores were developed high above the surface of the Earth to be dispersed by wind. Once the spores of the tree were dispersed, the trunk was no longer needed, and it died and fell to the Earth. In contrast, modern-day woody trees go through decades of reproductive cycles before dying.

The Equisetophyte Horsetail Trees

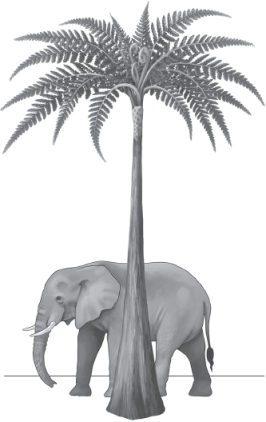

The second strange type of trees present in the Carboniferous rainforests that do not exist today were the equisetophyte trees (fig. 3.4). Like the lycophytes, equisetophyte plants still exist today, but most are quite small. The modern field horsetail Equisetum arvense stands 25 centimeters (ten inches) high and is abundant in many moist environments today, such as roadside ditches (Lecointre and Le Guyader 2006). In contrast, Carboniferous horsetail trees were gigantic—some Calamites trees stood 20 meters (65 feet) tall—80 times taller than our modern small horsetail rushes (fig. 3.4) (Taylor and Taylor 1993).

FIGURE 3.4 The equisetophyte horsetail tree Calamites was about 20 meters (65 feet) in height, here compared to a four-meter- (13-foot-) tall male African elephant.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

Although the calamitean horsetail trees belonged to the clade of the euphyllophytes (table 3.1), they still possessed microphylls—small leaves that were whorled about jointed branches attached to trunks that were also jointed. These jointed trunks grew upwards from large rhizomes buried in the soil, rather than from rootlike stigmarian systems as in the lycophyte trees (fig. 3.4). Like the modern-day field horsetail, these underground rhizomes had rootlet clusters at the nodes where the erect stems, or trunks as in the case of Calamites, were produced.2

Like the lycophyte trees, the ancient equisetophyte trees had a unifacial cambium and no secondary phloem; also like the peculiar lycophyte trees, they possessed the unusual trait of determinate growth (Donoghue 2005). Unlike the lycophyte trees, the segmented trunks of the equisetophyte trees were structurally supported by internal wedges of wood (Niklas 1997). Although the equisetophyte trees possessed more woody support than the lycophyte trees, the inward-pointing wedges of wood that were arranged around the circular interior of the trunk of the equisetophyte trees were very different from the massive amount of heartwood and sapwood found in the core of the trunk of a lignophyte tree.

The Filicophyte Fern Trees

The third major type of tree found in Carboniferous forests, the tree ferns, are not so strange to us as the extinct lycophyte and equisetophyte trees because some tree ferns, such as the Australian tree fern Cyathea cooperi, still exist today. However, most living ferns are small herbaceous plants, or more rarely shrub sized. They are easily recognizable by their characteristic large fronds of leaves that unfurl from fiddlehead-shaped spirals and the clusters of dark spores that periodically develop on the undersides of their leaves. In contrast, the Carboniferous tree ferns were large: the marattialean tree fern Psaronius (fig. 3.5) stood ten meters (33 feet) high (Taylor and Taylor 1993).

FIGURE 3.5 The marattialean true tree fern Psaronius was about ten meters (33 feet) tall, here compared to a four-meter- (13-foot-) tall male African elephant.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

The true ferns, the filicophytes (table 3.1), reproduce by spores and are not lignophyte plants. Thus the living tree ferns still exhibit those traits that they share with their extinct Carboniferous relatives, the equisetophyte trees. Unlike the equisetophytes, which evolved only a single type of tree, the filicophytes have convergently evolved tree forms no less than three separate times: Psaronius-type tree ferns in the Carboniferous, Tempskya-type tree ferns in the Cretaceous, and the tree ferns that survive today (McGhee 2011). Each group invented a different type of trunk in their evolution: the Carboniferous tree ferns had trunks supported by an outer mantle of adventitious roots; the Cretaceous tree ferns had trunks consisting of interwoven stems bound together by adventitious roots; and living tree ferns have a lower columnar base of adventitious roots and an upper trunk supported by an outer layer of cortex and external layer of leaf bases (Niklas 1997). Thus all three types of tree ferns construct their trunks in a very different manner than either the lycophyte or equisetophyte trees: they modify their root-growth systems for usage as support structures above ground.

The Medullosan Seed-Fern Trees

Only two of the five major tree types found in the great Carboniferous rainforests were spermatophyte lignophytes—seed plants with woody core tissue like our modern trees. These were the seed-fern trees and the pinophyte conifer trees (table 3.1). The evolution of the lignophyte plants in the Middle Devonian introduced a typical tree-trunk construction—having a structural support core of heartwood in the center of the trunk—that is very familiar to us in the modern world, but it could be argued that this construction is less mechanically efficient than the tree-trunk construction of the ancient non-lignophyte lycophyte, equisetophyte, and filicophyte trees in the Carboniferous forests. Karl Niklas, a paleobotanist at Cornell University, notes: “Engineers have long known that the best location for mechanically supportive materials is just beneath the surface of a vertical column, where mechanical bending and torsional forces reach their maximum intensities. This strategy is particularly important when the quantity of the stiffest building material is limited, perhaps for economy in design. It is no coincidence that the stiffest tissues in a variety of plants tend to develop just beneath or very near the external surface of vertical stems … the stiff lycopod periderm produced by the lepidodendrids … and the pertinacious mantle of adventitious roots around the stems of Psaronius are but a few examples of this mechanical strategy” (Niklas 1997, 331–333).

On the other hand, the evolution of bifacial cambium—one in which both secondary xylem and phloem tissues are produced—in the lignophytes was an adaptive innovation (Donoghue 2005). The secondary phloem in lignophytes makes possible the long-distance transport of food from the leaves high up in the crown of the tree down to the roots located far underground at the other end of the tree. The lycophyte and equisetophyte trees had a unifacial cambium and did not possess secondary phloem (Donoghue 2005). The growth consequences of possessing only a unifacial cambium for the lycophyte and equisetophyte trees have been noted previously.

The evolution of the seed plants, the spermatophyte lignophytes, in the Late Devonian Famennian Age was a major adaptive innovation in the geological history of plants. The key adaptation of the seed plants is their freedom from needing water in reproduction, unlike the spore-reproducing plants, and the spermatophytes could now colonize the dry highlands and mountains that were out of reach for non-spermatophyte plants. The evolution of the seed in plants was the ecological equivalent of the evolution of the amniote egg in vertebrates (Niklas 1997). a key adaptation that also freed the synapsid and reptilian amniotes (ancestors of modern-day mammals and reptiles, table 2.4) from needing water in their reproduction. These two groups, the seed plants and the amniote vertebrates, would become the victorious plant and vertebrate conquerors of the terrestrial realm of the Earth in the Carboniferous (McGhee 2013).

The ancient seed-fern trees were not true ferns (table 3.1), the spore-reproducing filicophytes (fig. 3.5), but rather were seed-reproducing plants that possessed foliage that looked very similar to that of a true fern. Seed ferns were also not a monophyletic clade in that three separate clades of spermatophyte lignophytes are often called “seed ferns”—the lyginopteridales, the medullosales, and the gigantopteridales (table 3.1)—all three of them extinct. The lyginopterids produced some fairly large seed-fern trees in the Early Carboniferous, such as Pitus, but the most important seed-fern trees in the Late Carboniferous were the medullosans, trees such as Medullosa and Sutcliffia. Medullosa was a small seed-fern tree that stood only about five meters (16 feet) tall, about half as tall as the true fern tree Psaronius (fig. 3.5). Smaller seed ferns like Neuralethopteris and Alethopteris also contributed to ground cover in the Carboniferous rainforests, as will be discussed shortly.

The Cordaitean Conifer Trees

The only other modern-type lignophyte trees found in the great Carboniferous rainforests were the pinophyte conifer trees (table 3.1). It is in the clade of the pinophytes that we finally find modern trees that are even more gigantic than the Carboniferous giants. The giant redwood trees of western North America, such as Sequoiadendron giganteum, can reach a height of 90 meters (300 feet)—almost twice the 50-meter (160-foot) height of the peculiar Carboniferous Lepidodendron scale trees.

The important conifer trees in the Late Carboniferous were the cordaitean pinophytes, trees such as Cordaites and Walchia. Cordaites was a small conifer tree that stood only about five meters (16 feet) tall, about half as tall as Psaronis (fig. 3.5).3 Some cordaitean trees had a tree-on-stilts appearance much like a modern mangrove tree, such as Rhizophora mangle, in that the trunk of the tree was elevated above ground by an extensive root system, the upper part of which was subaerial. Also like a modern mangrove tree, Cordaites trees are thought to have lived in wet environments on the margins of swamps and in coastal areas.

The Peculiar Carboniferous Rainforests

In summary, walking or boating in most of the great Carboniferous rainforests of the ancient Earth would have been quite a different experience than walking or boating in a modern rainforest. In a modern rainforest, the forest floor is in perpetual gloom as sunlight is shaded out by the canopy of leaves of the giant woody seed trees. A distinct canopy ecosystem exists up in the air of the modern rainforest, an ecosystem inhabited by vertebrate and arthropod carnivores and herbivores that live their lives in the sunlit canopy of leaves high above the Earth’s surface.

In contrast, in most of the Carboniferous rainforests the forest floor was illuminated, not shrouded in gloom, as the towering lycophyte and equisetophyte spore trees did not have large leaves that would shade out the forest floor below (fig. 3.6). The lycophytes also developed their canopies of branches only in the reproductive phase of their life cycle, so that any shading effect produced by their canopies of branches existed only for a fraction of the lifetime of the tree. Thus, much of the time, the rainforest may have had the peculiar appearance of being filled with many tall, pod-topped green poles without branches.

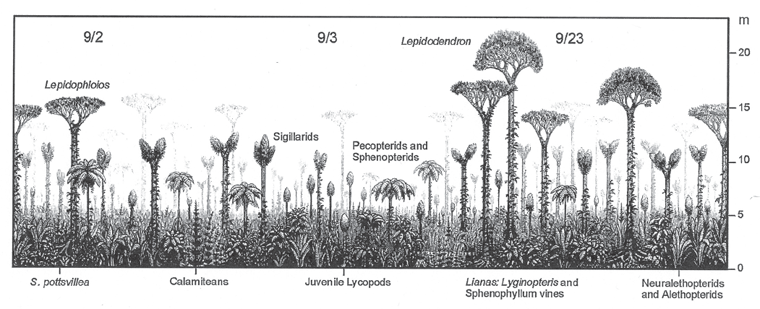

FIGURE 3.6 In situ reconstruction of a lycophyte tropical rainforest of Bashkirian Age, early Late Carboniferous, in present-day Alabama in North America. Characteristic flora are labeled, and the vertical scale in meters (right margin of the figure) gives the height of the plants in the foreground; see text for discussion.

Source: From Gastaldo, R. A., I. M. Stevanović-Walls, W. N. Ware, and S. F. Greb, “Community Heterogeneity of Early Pennsylvanian Peat Mires,” Geology vol. 32, pp. 693–696, copyright © 2004 Geological Society of America. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 3.6 illustrates a painstaking, labor-intensive reconstruction of a Late Carboniferous, Bashkirian Age, North American rainforest in Alabama (Gastaldo et al. 2004). The Colby College paleobotanist Robert Gastaldo and his colleagues descended into old coal mines in Alabama and took a careful census of in situ trees and plants embedded in the roofs of the mines, located immediately above the mined-out coal layer. This sampling procedure not only allowed the paleobotanists to census the species composition of the rainforest plants that existed at a single instant in time, but it also allowed them to spatially map the geographic distribution of the plants within the rainforest.

Rainforest reconstructions from three of their 17 field sites are shown in figure 3.6, labeled “9/2”, “9/3”, and “9/23”. Site 9/3, in the middle of the figure, shows the rainforest region with the least number of trees in canopy stage and greatest number of juvenile pole-like trees (94 percent). Taller Sigillaria lycophyte scale trees and lower Psaronis Marattialean tree ferns (Pecopteris leaf fossils) and Sphenopteris seed-fern trees are labeled in this region of the figure. Site 9/2, on the left in the figure, shows the rainforest with taller, mature Lepidophloios scale trees that have gone into canopy stage, with branches at the top of the pole-like trunk that itself is covered with a sleeve of leaves. Below the Lepidophloios and Sigillaria lycophyte trees are shown lower Calamites equisetophyte horsetail trees and a ground cover of Sphenopteris pottsvillea seed ferns. On the right in figure 3.6, at site 9/23, the rainforest is shown with a 53 percent canopy cover with still taller, mature Lepidodendron lycophyte trees—note again the fuzzy appearance of the trunk of the tree, which is covered in a sleeve of leaves. Below the canopy of Lepidodendron and Lepidophloios lycophyte trees—a canopy that covers only half of the sky in the rainforest—vinelike Lyginopteris seed ferns and Sphenophyllum equisetophytes are shown on the left, and ground cover Neuralethopteris and Alethopteris seed ferns are shown on the right.

This Alabama rainforest was overwhelmingly dominated by juvenile trees, with 95 percent juveniles in the youngest forests and 89 percent juveniles in the field sites with the greatest number of mature lycophyte trees. The youthfulness of the forest may have been a function of its origin: the forest formed when the mire basin subsided, water and sediment flooded in, and the new trees took root directly on top of the older, buried forest debris that would become the massive coal bed that was mined out by humans some 320 million years later. The lycophyte trees in this Alabama rainforest are also smaller than those in many other lycophyte-dominated forests, as the Lepidodendron scale trees are only 23 meters (75 feet) high—in other rainforests, these lycophyte trees could be twice that height. Unlike in a modern rainforest, there was no vertical stratification of specific lycophyte and equisetophyte tree species adapted to capturing light at different height zones in the ancient Carboniferous rainforests (Cleal 2010). Given their determinate mode of growth, the differing heights of the lycophyte and equisetophyte trees within the forest reflected the differing ages of the trees instead (fig. 3.6).

It has generally been argued that geographic variation in the composition of the lycophyte and equisetophyte trees species within the Carboniferous rainforests were a function of the areal distribution of different soil types and conditions such as waterlogged regions, muddy-margin regions along riverbanks, better-drained regions between rivers, dry upland regions, and so on (Cleal 2010). In particular, it has been argued that Lepidophloios trees preferred waterlogged regions, Lepidodendron trees preferred better-drained regions, and Sigillaria trees preferred drier upland regions. In contrast, the Alabama rainforest contained species of all three of these lycophyte tree genera coexisting in the same area (fig. 3.6). Gastaldo and colleagues suggest that the previously argued soil-moisture gradient for lycophyte tree species could be a sampling artifact, as previous reconstructions of Carboniferous rainforests were made from coal-ball assemblages—assemblages that are time averaged, with floras that “represent the resistant biomass contribution from several plant generations to the peat,” so that “resistant plant parts that accumulate and are buried may represent a century or more of biomass concentration in any one coal ball” (Gastaldo et al. 2004, 693). Alternatively, Gastaldo and colleagues suggest that the absence of a soil-moisture gradient in lycophyte tree distributions in the Alabama rainforest may be a function of the early geologic age of the forest in the Bashkirian, at the dawn of the Late Carboniferous. They suggest that a soil-moisture preference by the lycophyte trees may have evolved later, a result of “increasing habitat specialization as peat mires became more extensive in the Late Pennsylvanian” (Gastaldo et al. 2004, 696).

THE SPREAD OF THE GREAT RAINFORESTS

The lycophytes first evolved tree forms in the Middle Devonian Givetian Age, but it was not until the Early Carboniferous Serpukhovian Age that the first of the lycophyte-dominated tropical rainforests formed (table 2.3). The most extensive of these early tropical rainforests formed in what is now central Asia and northwest China, with smaller rainforests scattered in northern Europe and in North America. Best estimates of the original geographic extent of these rainforests indicate that they probably covered almost a half-million square kilometers (almost 200,000 square miles) of the tropical region of the Early Carboniferous Earth (table 3.2). In the Late Carboniferous Bashkirian and Moscovian Ages, the lycophyte-dominated rainforests progressively expanded in the Earth’s tropical region until they reached a maximum geographic extent of almost 2.5 million square kilometers (almost a million square miles; table 3.2) in the late Moscovian (fig. 3.7) (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

TABLE 3.2 Climatic events, area of rainforest coverage, and biological events during the Carboniferous phase of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| Age |

Geologic Time (Ma) |

Climatic Events |

Areal Extent of Rainforests |

Biological Events |

| |

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

| (Permian) |

298 |

ICE |

ICE-P1 |

|

1,255,000 km2 |

← Recovery in the rainforests |

| GZHELIAN |

299 |

|

|

|

1,087,000 km2 |

|

| |

300 |

|

|

|

1,095,000 km2 |

|

| |

301 |

|

|

|

1,110,000 km2 |

|

| |

302 |

|

|

|

1,111,000 km2 |

|

| |

303 |

|

|

|

1,120,000 km2 |

|

| KASIMOVIAN |

304 |

|

|

|

1,131,000 km2 |

|

| |

305 |

|

|

|

1,131,000 km2 |

|

| |

306 |

|

|

|

1,131,000 km2 |

|

| |

307 |

|

|

|

1,131,000 km2 |

← Extinction in the rainforests |

| MOSCOVIAN |

308 |

|

ICE |

|

2,395,000 km2 |

|

| |

309 |

|

ICE |

|

2,170,000 km2 |

|

| |

310 |

|

ICE |

|

1,945,000 km2 |

|

| |

311 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,721,000 km2 |

|

| |

312 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,840,000 km2 |

|

| |

313 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,822,000 km2 |

|

| |

314 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,804,000 km2 |

|

| |

315 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,786,000 km2 |

|

| BASHKIRIAN |

316 |

ICE |

ICE-C4 |

ICE? |

1,456,000 km2 |

|

| |

317 |

ICE |

|

|

1,258,000 km2 |

|

| |

318 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

1,060,000 km2 |

|

| |

319 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

826,000 km2 |

|

| |

320 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

664,000 km2 |

|

| |

321 |

ICE |

ICE-C3 |

|

467,000 km2 |

|

| |

322 |

ICE |

|

|

467,000 km2 |

|

| |

323 |

ICE |

|

|

467,000 km2 |

|

| SERPUKHOVIAN |

324 |

ICE |

ICE |

ICE? |

450,000 km2 |

|

| |

325 |

ICE |

ICE |

ICE? |

450,000 km2 |

|

| |

326 |

ICE |

ICE-C2 |

Cold |

450,000 km2 |

← First rainforests |

| |

327 |

ICE |

|

|

|

|

| |

328 |

ICE |

|

|

|

|

| |

329 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

|

|

| |

330 |

ICE |

ICE-C1 |

|

|

|

| VISEAN (pars) |

331 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

332 |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Gondwana data from Isbell et al. (2003), Frank et al. (2008), and Fielding, Frank, Birgenheier et al. (2008); Siberian data from Epshteyn (1981a), Chumakov (1994), and Raymond and Metz (2004). Rainforest data are from Cleal and Thomas (2005); timescale modified from Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Climatic events column (1) is West and Central Gondwana and column (2) is East Gondwana (Australia), both in the Southern Hemisphere; column (3) is Siberia (northeastern Russia) in the Northern Hemisphere. Bold type indicates the existence of continental glaciers, and normal type indicates the presence of alpine glaciers; glaciations in eastern Gondwana are designated C1 through C4, from oldest to youngest.

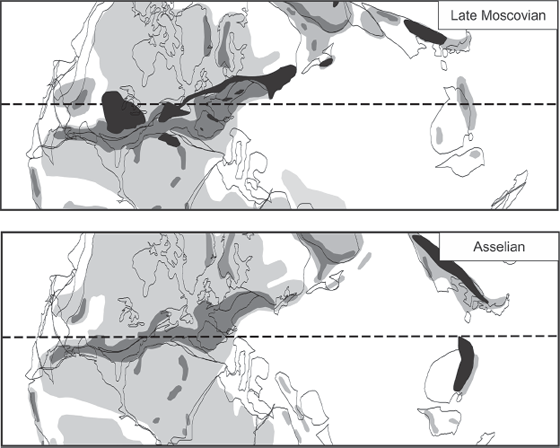

FIGURE 3.7 Paleogeographic distribution of lycophyte rainforests in the Late Carboniferous late Moscovian Age (upper figure) contrasted with the Early Permian Asselian Age (lower figure). Rainforest areas are shown in black, highland areas are shown in dark gray, lowland areas are shown in light gray, and areas under marine waters are shown in white; see text for discussion.

Source: Thanks to Dr. Christopher Cleal, Department of Biodiversity and Systematic Biology, National Museums and Galleries of Wales, for creating this figure for this book (modified from Cleal and Thomas, 2005).

In the late Moscovian Age, huge expanses of lycophyte-dominated tropical mires stretched across the continental-interior and Appalachian-basin regions of the present-day United States (fig. 3.7). To the east, lycophyte rainforests stretched continuously from eastern Canada in North America across southern Ireland, through Wales and England, across northern Europe, to vast tropical mires in Kazakhstan. Along the way, large isolated basins filled with lycophyte-dominated mires existed in northern Africa, Spain, and middle Europe. Further to the east, lycophyte rainforests existed in basins in western Asia and in vast mires on the Sino-Korean continental block (present-day Korea and North China; fig. 3.7).

The spread of the great rainforests is clearly correlated with the onset of the major Carboniferous phase of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. Massive continental ice sheets formed first in western and central Gondwana in the early Serpukhovian (glacial phase GII of Frank et al. 2008), with alpine ice sheets in the highlands of eastern Gondwana (table 3.2) (glacial phase C1 of Fielding, Frank, Birgenheier et al. 2008). By the late Serpukhovian, lowland continental ice sheets had formed in eastern Gondwana (glacial phase C2 of Fielding, Frank, Birgenheier et al. 2008), and the northern hemisphere of the Earth had become glaciated as well, with a polar sea-ice cap in Laurasia (off modern-day Siberia, northeastern Russia) (Epshteyn 1981a; Frakes et al. 1992; Stanley and Powell 2003; Raymond and Metz 2004).

Why was the spread of the great rainforests correlated with the onset of the massive-ice-formation phase of the Carboniferous glaciation? The huge accumulation of frozen water on land in massive glaciers had the effect of lowering global sea levels, and as the seas drained off of the land, vast areas of once flooded shallow marine shelf were exposed to subaerial conditions in the tropics. Thus vast areas of flat, miry, wetland habitats were created, in what the Kentucky Geological Survey geologist Stephen Greb and colleagues call the “largest tropical peat mires in Earth history” (Greb et al. 2003, 127)—perfect habitats for the lycophyte trees in particular.

Not only did the falling sea level expose vast areas of land that was once under water, it also had the effect of lowering the base level of erosion in the uplands. Rivers that once had been near sea level were now at an elevation considerably higher than sea level, and they began to incise their valleys, cutting downward toward the new sea level. This increased erosion transported huge amounts of sediment outward over the newly exposed flatlands, creating large river deltas like our modern-day Amazon delta—again, perfect habitats for the lycophyte trees in particular.

Plants are photoautotrophic organisms; that is, they produce their own food by using energy from the sun. In this process, they extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, split hydrogen atoms from water molecules in their leaves, and combine the hydrogen and carbon dioxide molecules to produce hydrocarbon molecules like sugar. Once the hydrogen is split from water molecules, the oxygen in the water molecules is left over as a waste product and the plants simply dump it into the atmosphere.4

The spread of the great rainforests had profound consequences for the Earth’s atmosphere. Huge amounts of carbon dioxide were being extracted from the atmosphere to form food for the land plants in the forests. At the same time, huge amounts of oxygen were being produced by the plants and dumped into the atmosphere. Hour after hour, day after day, year after year, for millions and millions of years, this process took place in the great rainforests. The carbon-dioxide content of the Earth’s atmosphere must have declined as a result, and the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere must have increased—but how can we measure these changes in the atmosphere of the Earth in the Carboniferous, over 300 million years ago?

THE GREAT RAINFORESTS AND ATMOSPHERIC OXYGEN

We know that the concentration of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere was very low in the Frasnian Age of the Late Devonian but that the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere began to increase following the Famennian Gap. How do we know this? The empirical data that support this conclusion come from the distribution of charcoal deposits in the sedimentary rock record. Charcoal is produced by wildfires, and wildfires do not occur unless quite specific levels of oxygen are present in the atmosphere. Despite extensive stratigraphic searches, the Frasnian Age is known for the rarity of charcoal deposits in its strata. The absence of wildfires in the Frasnian is quite striking, given the spread of Earth’s first forests during this same time interval. The geologists Andrew Scott, of the University of London, and Ian Glasspool, of the Field Museum of Natural History, comment: “Archaeopteris, the first large woody tree, evolved in the Late Devonian and spread rapidly. By the Mid-Late Frasnian, monospecific archaeopterid forests dominated lowland areas and coastal settings over a vast geographic range. Despite this extensive wood biomass, charcoal occurrences are rare with only isolated fragments of charred Callixylon (archaeopterid) wood reported from this interval and small amounts of inertodetrinite (microscopic charcoal fragments) preserved in early Late Devonian Canadian coals” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10863). In fact, the entire interval of the Eifelian Age through the Frasnian Age has been termed the “charcoal gap,” as there is very little evidence of any wildfires anywhere during this period (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10862, 10864).

In contrast, the Famennian Age is well known for numerous charcoal deposits in its strata, deposits that demonstrate that wildfires were common. The oldest Famennian charcoal deposits yet discovered come from strata in Pennsylvania dated to about 362.7 million years ago.5 Charcoal data from around the world indicate that frequent wildfires occurred in widely separated regions of the Earth in the last 3.5 million years of the Famennian (Scott and Glasspool 2006, fig. 1; Marynowski and Filipiak 2007; Marynowski et al. 2010). An oxygen level of at least 13 percent has to be present in the atmosphere in order for wildfires to ignite (Scott and Glasspool 2006). Thus hard empirical data exist to demonstrate that the atmosphere of the Earth contained 13 percent oxygen, or more, in the last 3.5 million years or so of the Famennian. The absence of charcoal in strata in the Famennian Gap, and in the mid to late Frasnian, can be used to argue that oxygen levels present in the Earth’s atmosphere were below 13 percent during this span of time. Woody plant material was abundant in the Frasnian; if wildfires occurred, then charcoal should be present in Frasnian strata—but it is not.

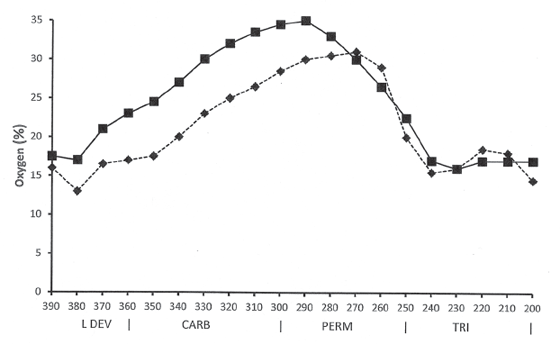

In addition to the empirical charcoal data, another type of evidence supports the previous conclusion concerning oxygen levels in the Earth’s atmosphere during the Late Devonian: the “empirical model,” a model whose predictions depend not only on the mathematics of the model’s assumptions but also on input from empirical data. The geochemist Robert Berner of Yale University and his colleagues have constructed two empirical models, Rock-Abundance and Geocarbsulf, in an attempt to predict atmospheric oxygen concentrations throughout the span of the Phanerozoic on Earth (Berner et al. 2003; Berner 2006). Both models predict that the concentration of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere increased from the Frasnian into the Famennian—thus matching the charcoal data—and then continued to increase throughout the Carboniferous into the Permian (fig. 3.8). Specifically, both models predict minimum oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere in the early Frasnian (380 million years ago): 17 percent in the Rock-Abundance model and 13 percent in the Geocarbsulf model, and higher oxygen concentrations in the Famennian: 21–23 percent in the Rock-Abundance model and 16–17 percent in the Geocarbsulf model.

FIGURE 3.8 Modeled fluctuations in atmospheric oxygen content from the Late Devonian through the Triassic. The square data points and solid line show the predictions of the Rock-Abundance model, and the diamond data points and dotted line show the predictions of the Geocarbsulf model; see text for discussion. Geologic timescale abbreviations: L DEV, Late Devonian; CARB, Carboniferous; PERM, Permian; TRI, Triassic.

Source: Data from Berner et al. (2003) and Berner (2006).

However, Scott and Glasspool urge some caution in accepting either model’s predictions: “Predictions of the degree to which O2 fluctuated [in the Late Devonian] are based on data-driven models. However, the complexity of the feedback mechanisms that govern O2 levels results in a large degree of uncertainty in these models, as is evident in their frequent refinement. Additional data sets are invaluable to these refinements” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10861). They note that the empirical models’ predictions of lower oxygen concentrations in the Frasnian atmosphere fit with the evidence of the “charcoal gap” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10862) in the strata of this time period. However, given the frequency of charcoal occurrences in late Famennian strata, they suggest that oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere in the late Famennian may have been higher than the 17 percent predicted by the Geocarbsulf model and more in accord with the 23 percent concentration predicted by the Rock-Abundance model. The discrepancy between the charcoal data set and the Geocarbsulf model becomes even more marked in the Carboniferous: “Collectively, these data suggest levels of O2 modeled for this interval rising from 17 percent to 23.5 percent [in the Geocarbsulf model] are inappropriate and instead favor prior, higher levels modeled at ≈23–31.5 percent [in the Rock-Abundance model], values further supported by the occurrence of very large arthropods at this time” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10863). The appearance of gigantic arthropods on Earth in the Carboniferous will be considered in detail in chapter 4.

Thus we have two lines of evidence that oxygen was in short supply in the atmosphere of the Frasnian world: the charcoal-distribution data and the empirically based geochemical models. This evidence leads immediately to the question: why was oxygen in short supply? One obvious way to address this question is to consider the organisms that were producing the oxygen in the first place—the plants. As outlined in chapter 1, it is known that land plants suffered a major loss in diversity in the end-Frasnian biodiversity crisis. The number of known macrofossil genera dropped to 13, a minimum diversity level that persisted unchanged through the Famennian Gap. Taking a look at longer timescales, Anne Raymond and Cheryl Metz, paleobotanists at the University of Texas, have shown that land plants were losing diversity through the entire Middle Devonian into the Frasnian (Raymond and Metz 1995), though the loss was not as severe as the diversity loss that occurred in the late Frasnian. Land-plant macrofossil diversity was at its maximum in the Early Devonian Emsian, with 38 genera known. Diversity dropped to 31 genera in the Middle Devonian Eifelian, dropped further to 24 genera in the middle Frasnian, and then dropped precipitously to a low of 13 genera in the late Frasnian. In summary, the decline in land-plant diversity seen in the fossil record roughly parallels the decline in oxygen levels in the atmosphere predicted by the geochemical models for the Frasnian, suggesting a causal relationship between land-plant diversity and atmospheric oxygen levels.

The reverse of this argument is also true: the increase in land-plant diversity and the geographic spread of the great rainforests in the Carboniferous and their persistence in the Permian should have produced a major increase in atmospheric oxygen levels on the Earth. And indeed, the geochemical models predict that just such an increase did in fact occur (fig. 3.8). But, as Scott and Glasspool have cautioned, the two geochemical models give different predictions: the Rock-Abundance model predicts that a maximum concentration of 35 percent oxygen in the atmosphere occurred about 290 million years ago, in the Artinskian Age of the Early Permian, whereas the Geocarbsulf model predicts that a maximum concentration of 31 percent oxygen in the atmosphere occurred much later, about 270 million years ago, in the Wordian Age of the Middle Permian. More important, the Geocarbsulf model predicts that the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere did not increase to 30 percent or higher until the Artinskian Age of the Early Permian—atmospheric oxygen concentrations for the entire Late Carboniferous are predicted to have been below 30 percent (fig. 3.8).6 The biological implications of these model differences in the predicted oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere in the Carboniferous will be explored in detail in chapter 4, where we will consider the evolution of animal gigantism in the Carboniferous.

THE EARTH UP IN SMOKE?

Wildfires are common in our present-day world with its atmosphere of 21 percent oxygen—we are all familiar with scenes of firefighters battling blazes in California or Arizona in western North America, or in Spain or Greece in Mediterranean Europe. However, truly massive wildfires are confined to these generally arid regions of the Earth. In contrast, in a world with an atmosphere of 25 percent oxygen, wildfires will become widespread even in wet climatic regions (Scott and Glasspool 2006). And in a world with an atmosphere of 30 percent oxygen, almost every single tree struck by lightning during a storm will catch fire—regardless of how wet it may be. A large thunderstorm with multiple lightning strikes in a localized area would result in a raging wildfire, burning even swamp foliage down to the water level.

The Rock-Abundance model predicts that the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere (fig. 3.8) exceeded 25 percent around 340 million years ago in the Visean Age of the Early Carboniferous, and the Geocarbsulf model predicts a somewhat later date of 320 million years ago in the Bashkirian Age of the Late Carboniferous. Moreover, the Rock-Abundance model further predicts that oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere reached the 30 percent level around 330 million years ago, in the Serpukhovian Age of the Early Carboniferous, and remained above 30 percent until 260 million years ago, in the Late Permian.

Were wildfires almost constantly present in the great rainforests of the Late Carboniferous Earth? Two lines of empirical evidence suggest that they were. First, the University College London biochemist Nick Lane notes that over 15 percent of the volume of some Late Carboniferous coals is charcoal, “an extraordinary amount if we consider that coal beds are formed in swamps, which under modern conditions virtually never catch fire” (Lane 2002, 95).7 The abundant presence of charcoal in Carboniferous coal strata is hard fossil evidence that the wet, tropical mires of the Earth were frequently on fire. At present atmospheric levels of 21 percent oxygen, our modern rainforests and swamps in Indonesia and Malaysia are constantly wet and virtually fire free; thus the atmosphere of the Earth must have contained much more oxygen in order for tropical mires to catch fire in the Carboniferous.

Second, Lane notes that empirical evidence exists that Late Carboniferous wildfires burned exceedingly hot compared to our present-day wildfires, a point that further explains how wet foliage could burn so frequently:

Coals that formed during periods of hypothetically high oxygen, such as the Carboniferous and Cretaceous, contain more than twice as much charcoal as the coals that formed during low-oxygen periods like the Eocene (54 to 38 million years ago). This implies that fires raged more frequently in time of high oxygen and were not related to climate alone. Some of the properties of the charcoal support this interpretation. The shininess of charcoal depends on the temperature at which it was baked. Charcoals formed at temperatures about 400°C are shinier than those that cooked at lower temperatures, and so reflect back more of the light directed at them. The difference can be detected with great accuracy using a technique known as reflection spectroscopy. The shininess of fossil charcoals from both the Carboniferous and Cretaceous implies that they formed at searing temperatures, almost certainly above 400°C and perhaps as high as 600°C, in fires of exceptional intensity. (Lane 2002, 95–96)

Fueled by a rich oxygen atmosphere, flames burning at 400°C (752°F) to 600°C (1,112°F) could sweep through even the soggiest rainforest foliage in the Late Carboniferous. These two empirical data—the amount of charcoal present in Carboniferous coals and the high temperature at which that charcoal was formed—strongly suggest that the Rock-Abundance model for the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere in the Carboniferous and Permian is more accurate than the Geocarbsulf model (fig. 3.8).

The Late Carboniferous sky was probably almost always yellow-beige in color, somewhat similar to the present-day orange-beige color of the sky on Mars that we see in the numerous photographs taken by our robot rovers on the Martian surface. The Martian sky is colored by dust; the Carboniferous sky was colored by smoke. If we could have viewed the Earth from space in the Late Carboniferous, we would have seen thick black plumes of smoke rising from numerous spots in the green band of the great rainforests, smearing out to long streaks of brown where the rising smoke plumes encountered higher-level atmospheric winds. The faint smell of smoke was probably almost constantly detectable in the air around the world, even in higher-latitude localities far away from the tropical band straddling the equator that contained the great rainforests and their numerous wildfires.

WHY DID SO MUCH COAL FORM IN THE LATE CARBONIFEROUS?

Nick Lane points out that 90 percent of the Earth’s coal strata were deposited in the time span from the Serpukhovian Age in the Early Carboniferous to the Wuchiapingian Age in the Late Permian, and marvels at the “riddle posed by this 70-million-year period, which lasted from around 330 to 260 million years ago. [This means that] 90 percent of the world’s coal reserves date to a period that accounts for less than 2 percent of the Earth’s history. The rate of coal burial was therefore 600 times faster than the average for the rest of geological time” (Lane 2002, 84).

Why did so much coal form in the Late Carboniferous? One key to this mystery may be the type of coal that is found in these strata—namely, its unusually high charcoal content. Lane points out that “charcoal is virtually indestructible by living organisms, including bacteria. No form of organic carbon is more likely to be buried intact” (Lane 2002, 79) and that some Carboniferous coal beds “contain over 15 per cent fossil charcoal by volume…. The closest modern equivalents to Carboniferous coal swamps, the swamps of Indonesia and Malaysia, are almost charcoal-free” (Lane 2002, 95). Scott and Glasspool further point out that we now know that the mineral inertinite is fossil charcoal, and that inertinite is “a constituent component of many coals” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10861) in the Paleozoic. Thus part of the “riddle posed by this 70-million-year period, which lasted from around 330 to 260 million years ago” (Lane 2002, 84) in which the rate of coal burial was astoundingly high, may be attributable to the high oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere during this same period of time. If the Rock-Abundance model is correct, then the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere was above 30 percent for the entire period from 330 to 260 million years ago (fig. 3.8). The resulting wildfires in the tropical mires of the Earth produced enormous amounts of nearly indestructible charcoal to be buried in the rock record.

A second key to the mystery of the massive amounts of coal found in Carboniferous strata may have been the general absence of wood consumers in Carboniferous ecosystems. Even if 15 percent of Carboniferous coal is near-indestructible charcoal, what accounts for the preservation of the other 85 percent that is not? Scott Richard Shaw, a paleoentomologist at the University of Wyoming, asks: “Why does most of our coal and much of our petroleum date from the Carboniferous period? The orthodox view is simply that the Carboniferous swamps provided optimal conditions for fossil fuel formation. After that time, the world became drier, and conditions were not as favorable. But is that all there is to it? Forests didn’t go away after the Carboniferous. If anything, there were even more trees…. Something other than a change in the weather must have occurred” (Shaw 2014, 74). Shaw argues that that “something other” was the evolution of numerous wood consumers in post-Carboniferous forests: “In the Early Carboniferous, most of today’s macroscopic and microscopic consumers of dead wood had not yet evolved. There were no birds, mammals, bees, wasps, bark beetles, wood-boring beetles, bark lice, termites, or ants.” Thus, “the Late Devonian and Carboniferous really were special for their excess production of plant materials … because the plants were able to produce more biomass than the herbivores could consume, for millions of years. The first important insect wood consumers—the wood roaches—did not appear until the Late Carboniferous. They were followed by the appearance of bark lice and the diversification of wood-boring beetles in the Permian” (Shaw 2014, 75). In contrast, in the Early Carboniferous, the fungus consumers of trees were joined only by the oribatid mites and a few detritus-feeding millipedes and primitive wingless insects (Shaw 2014, 205, note 5).

A third key to the mystery of the Carboniferous coal strata might be found in the peculiar growth mode of the ancient lycophyte and equisetophyte trees. Did these trees simply produce more biomass than existing Carboniferous wood consumers could destroy, or was there another component to their excess biomass production? One possibility is that the lycophyte trees in particular had extremely fast determinate growth. It has been estimated that a 50-meter-high (160-foot-high) mature tree could be produced in ten years—a tree that would then promptly die after producing its spores (Phillips and DiMichele 1992). However, this argument has been challenged by the Stanford University paleobotanist Kevin Boyce and reconsidered by the Smithsonian paleobotanist William DiMichele, who maintain that “such rapid growth would violate all known physiological mechanisms” and that the giant lycophyte trees grew at a pace comparable to that of a modern-day palm tree (Boyce and DiMichele 2016). In any event, a single dead Lepidodendron tree falling down into the surrounding mire could contain as much as 3.2 tonnes (3.5 tons) of carbon (estimated by Cleal and Thomas, 2005, using the carbon-biomass estimates of Baker and DiMichele, 1997).

In a Carboniferous rainforest containing 500 to 1,800 such giant, fast-growing lycophyte trees per hectare (2.5 acres) (DiMichele et al. 2001), Cleal and Thomas calculate that these trees could extract between 160 and 578 tonnes (176 and 636 tons) of carbon from the atmosphere per year. Unlike in modern lignophyte trees, this fixed carbon did not then continue to be present in living biomass as the trees lived on for decades or even centuries. The mature lycophyte trees died in only ten years or so, and the carbon contained in the dead tree would be taken out of the living ecosystem and transferred to the swamp waters below. The water in the tropical swamps appears to have been acidic and with low fungal activity (DiMichele et al. 1985; Robinson 1990), and Cleal and Thomas calculate that only about 25 percent of the carbon in the dead trees in the mires was returned to the atmosphere by fungal consumption of the trees. Another 5 percent of the carbon was probably lost in runoff water from the swamp, resulting in a net accumulation of from 108 to 390 tonnes (119 to 429 tons) of carbon in the swamp sediments per year.

These estimates of carbon accumulation in the rock record for the Late Carboniferous rainforests are radically different from those for modern rainforests. The lignophyte trees in a modern rainforest grow slowly and live for decades or even centuries, and most of the carbon in the dead vegetation is recycled back into the atmosphere by aerobic-respiring fungal and bacterial consumers. In contrast to the estimated 108 to 390 tonnes (119 to 429 tons) of carbon stored in the sediments per year in the lycophyte-dominated rainforest, it is estimated that in a modern lignophyte-dominated rainforest, between two and ten tonnes (2.2 and 11 tons) of carbon goes into long-term sequestration per year (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

Further evidence that the peculiar growth mode of the lycophyte trees was a major factor in the accumulation of such major amounts of coal in the rock record comes from comparing the amount of coal produced by the Bashkovian-Moscovian rainforests, which were dominated by lycophyte trees, with that of the Permian rainforests, which were dominated by tree ferns. Cleal and Thomas note that both rainforests produced a similar tonnage of coal—about 200 billion tonnes (220 billion tons)—but that that amount was produced in about 11 million years by the lycophyte-dominated rainforests in the Bashkovian-Moscovian span of time, whereas it took the tree-fern-dominated rainforests about 35 million years in the Permian to produce the same amount of coal. That is, the lycophyte-dominated rainforests, with their fast-growing, determinate-growth-mode trees, produced coal at a rate three times higher than the slower-growing, non-determinate-growth-mode rainforests dominated by tree ferns (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

A fourth key to the mystery of the Carboniferous coal deposits might be found in the atmosphere of the Carboniferous world: there simply may have been much more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that could be extracted and fixed in plant tissues than in our modern world. That is, net plant productivity may have been much higher in the Carboniferous world than in our modern world, where plants are carbon deprived in our atmosphere containing 0.04 percent carbon dioxide. Even with a hyperoxic atmosphere, atmospheric modeling by the University of Sheffield botanist David Beerling and geochemist Robert Berner of Yale University suggests that in an atmosphere with a carbon-dioxide content of 0.06 percent, the “CO2 fertilization effect is larger than the cost of photorespiration, and ecosystem productivity increases leading to the net sequestration of 117 Gt C [117 billion tonnes of carbon] into the vegetation and soil carbon reservoirs. In both cases, the effects result from the strong interaction between pO2 [partial pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere], pCO2 [partial pressure of carbon dioxide], and climate in the tropics” (Beerling and Berner 2000, 12428). And the tropics were where the great rainforests were located in the Carboniferous.

In summary, all of these factors—excess wildfires and charcoal production in a world with a hyperoxic atmosphere, the lack of numerous wood consumers in Carboniferous ecosystems, rapid determinate growth in the peculiar lycophyte and equisetophyte trees, and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere for the Carboniferous plants to fix into more plant biomass—acted in concert to produce 90 percent of the world’s coal reserves in a period of time that accounts for less than 2 percent of the history of the Earth.

THE KASIMOVIAN CRISIS IN THE GREAT RAINFORESTS

Something happened to the great rainforests in the Kasimovian, something that would have been noticeable even from space. The rainforests still existed in the Kasimovian, but the area of the Earth covered by their green expanse had shrunk by 53 percent (table 3.2); that is, over half the area of the green band that circled the Earth in the Moscovian was gone in the Kasimovian (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

Descending into the rainforests from space, we would immediately notice that the trees were different—the towering, peculiar lepidodendrid scale trees that were so common in the Bashkirian and Moscovian rainforests were gone. Instead, the majority of the trees surrounding us were now tree ferns, marattialean filicophytes (table 3.1). What happened to the great lycophyte trees?

The University of Pennsylvania paleobotanist Hermann Pfefferkorn and colleagues argue that the fossil record shows this marked changeover in the great Carboniferous rainforests occurred in three steps: First came the abrupt disappearance of the towering, pole-like lepidodendrid scale trees. Species of the once-abundant lycophyte tree genera Lepidodendron (fig. 3.3), Lepidophloios, Paralycopodites, Hizemodendron, Diaphorodendron, and Synchysidendron all vanish from the fossil record. Second, there was a short interval of time in which the wetlands were populated by smaller understory seed-reproducing trees—medullosan seed-fern trees and cordaitean pinophyte trees—and a ground cover consisting of spore-reproducing plants—sphenophylleacean horsetails and chaloneriacean quillworts (table 3.1), both of which groups are now extinct. This brief interval is sometimes represented by a single coal bed in the fossil record. Third, the wetlands then began to be repopulated with spore-reproducing trees—large marattialean tree ferns (fig. 3.5) and the surviving sigillarian lycophyte scale trees (fig. 3.9). The sigillarian scale trees were smaller than the lepidodendrids, averaging about 20 to 25 meters (66 to 82 feet) in height (Taylor and Taylor 1993), with crowns that did not branch as profusely as the lepidodendrids (compare figs. 3.3 and 3.9).

FIGURE 3.9 The lycophyte scale tree Sigillaria was about 20 to 25 meters (66 to 82 feet) tall, here compared to a four-meter- (13-foot-) tall male African elephant.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

All in all, 87 percent of the Moscovian trees species and 33 percent of the ground cover and vine species went extinct in the Kasimovian. In addition, the proportion of trees to ground cover and vine species also changed radically in the floral changeover. In the Moscovian, the ratio of trees to ground cover and vines was 30 to 18; in the Kasimovian, that ratio changed to 18 to 25, an almost complete reversal of the floral structure of the rainforest (Pfefferkorn et al. 2008). Why were there so many more vines in the Kasimovian rainforests? Michael Krings, a paleobotanist at the Bavarian State Museum of Paleontology, and his colleagues argue that the evolution and proliferation of new climbing plant species in the Kasimovian was driven by a radical change in the canopy structure of the tropical rainforests during the Late Carboniferous (Krings et al. 2003). The Bashkirian and Moscovian tropical rainforests were dominated by the peculiar arborescent lycophytes, polelike scale trees that did not possess large leafy crowns even during their reproductive phase, when they grew multiple drooping branches at the tops of their trunks. Moreover, their canopy branches were covered by small, microphyll-type leaves that would cast relatively little shadow on the ground below the tree. The combination of these two structural characteristics of the lycophyte trees resulted in a rainforest with a very open canopy, with a great deal of sunlight reaching the ground surface below the trees.