A massive expansion of ice occurred at the Pennsylvanian-Permian boundary, and glaciation became bipolar at that time. Ice sheets are inferred to have been at their maximum extent during the Asselian and early Sakmarian, after which they decayed rapidly over much of Gondwana.

—Fielding, Frank, and Isbell (2008, 343)

THE EARLY PERMIAN DEEP FREEZE

Nine million years had passed since the end of the C4 continental glaciation in eastern Gondwana (present-day Australia) and the massive extinction in the great rainforests in the Kasimovian Age of the Late Carboniferous (table 3.2). But the Late Paleozoic Ice Age was not finished yet, and the dawn of the Permian saw the return of massive ice sheets across the supercontinent Gondwana in the Southern Hemisphere, both in the west and the east, and by the early Sakmarian Age in the Northern Hemisphere as well (table 5.1). For the second time, the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had become bipolar, as stated in the epigraph of this chapter. Or had it? Once again, the bipolar controversy concerning the Late Paleozoic Ice Age—which we first encountered in the Carboniferous in chapter 2—returns when we enter the Permian.

TABLE 5.1 Climatic events, area of rainforest coverage, and biological events during the Permian phase of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| Age |

Geologic Time (Ma) |

Climatic Events |

Extent of Rainforests |

Extinction Events |

| |

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

| (Triassic) |

252 |

|

|

|

|

|

| CHANGHSINGIAN |

253 |

|

|

|

|

← End-Permian Mass Extinction |

| |

254 |

|

|

|

140,000 km2 |

|

| WUCHIAPINGIAN |

255 |

|

|

|

183,000 km2 |

|

| |

256 |

|

ICE |

|

236,000 km2 |

|

| |

257 |

|

ICE |

|

289,000 km2 |

|

| |

258 |

|

ICE |

|

342,000 km2 |

|

| |

259 |

|

ICE |

|

395,000 km2 |

|

| CAPITANIAN |

260 |

|

ICE-P4 |

|

373,000 km2 |

← Capitanian Extinction |

| |

261 |

|

|

|

350,000 km2 |

|

| |

262 |

|

|

|

328,000 km2 |

|

| |

263 |

|

ICE |

|

305,000 km2 |

|

| |

264 |

|

ICE |

|

283,000 km2 |

|

| |

265 |

|

ICE |

|

261,000 km2 |

|

| WORDIAN |

266 |

|

ICE |

|

239,000 km2 |

|

| |

267 |

|

ICE |

|

227,000 km2 |

|

| |

268 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

216,000 km2 |

|

| ROADIAN |

269 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

194,000 km2 |

|

| |

270 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

179,000 km2 |

|

| |

271 |

|

ICE-P3 |

ICE? |

164,000 km2 |

|

| |

272 |

|

|

ICE? |

150,000 km2 |

|

| KUNGURIAN |

273 |

|

|

|

127,000 km2 |

|

| |

274 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Extinction |

| |

275 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

276 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

277 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

278 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

279 |

|

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| ARTINSKIAN |

280 |

|

|

|

332,000 km2 |

|

| |

281 |

|

|

|

482,000 km2 |

|

| |

282 |

|

|

|

633,000 km2 |

|

| |

283 |

|

|

|

784,000 km2 |

|

| |

284 |

|

ICE |

|

1,011,000 km2 |

|

| |

285 |

|

ICE |

|

1,115,000 km2 |

|

| |

286 |

|

ICE |

|

1,220,000 km2 |

|

| |

287 |

|

ICE |

|

1,325,000 km2 |

|

| |

288 |

|

ICE |

|

1,430,000 km2 |

|

| |

289 |

|

ICE |

|

1,690,000 km2 |

|

| |

290 |

|

ICE |

|

1,640,000 km2 |

|

| SAKMARIAN |

291 |

|

ICE |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

292 |

|

ICE-P2 |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

293 |

|

|

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

294 |

ICE |

ICE |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

295 |

ICE |

ICE |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| ASSELIAN |

296 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

297 |

ICE |

ICE |

|

1,422,000 km2 |

|

| |

298 |

ICE |

ICE-P1 |

|

1,255,000 km2 |

|

| (Carboniferous) |

299 |

|

|

|

1,087,000 km2 |

|

| |

300 |

|

|

|

1,095,000 km2 |

|

Source: Gondwana data from Isbell et al. (2003), Frank et al. (2008), Fielding, Frank, Birgenheier et al. (2008), and Metcalfe et al. (2015); Siberian data from Ustritsky (1973), Epshteyn (1981b), Chumakov (1994), and Raymond and Metz (2004). Rainforest data from Cleal and Thomas (2005), timescale modified from Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Climatic events column (1) is West and Central Gondwana and column (2) is East Gondwana (Australia), both in the Southern Hemisphere; column (3) is Siberia (northeastern Russia) in the Northern Hemisphere. Bold type indicates the existence of continental glaciers; normal type indicates the presence of alpine glaciers, with glaciations in eastern Gondwana designated P1 through P4, from oldest to youngest.

The Early Permian chill is astounding: the Earth went from the balmy Kasimovian-Gzhelian interpulse greenhouse interval in the Late Carboniferous (table 3.2) to a globally frozen state with new ice caps in the South in the Asselian—and perhaps in the North Pole in the Sakmarian (table 5.1). At the beginning of the Permian, the ice sheets in western and central Gondwana formed their third and final phase of continental glaciation in the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, and in eastern Gondwana the ice sheets formed the first glaciation phase, P1, of the Permian.

The climatic condition of the North Pole is much more uncertain. Early stratigraphic data from the northeastern tip of Russia have been use to argue for the presence of continental ice in this region, which at that time was very close to the North Pole,1 during the Sakmarian, but other workers have argued that these data were misdated and that they were in fact of Bashkirian-Muscovian age in the Late Carboniferous (Ustritsky 1973; Epshteyn 1981a; Isbell et al. 2016). For this reason, I have placed question marks on the Sakmarian northern hemisphere data in table 5.1.

A brief warming phase then occurred in the middle Sakmarian Age in the Southern Hemisphere, and the continental glaciers in Gondwana retreated (table 5.2). Cooling resumed in the late Sakmarian, triggering the P2 continental glacial phase in eastern Gondwana—but only in eastern Gondwana, as western and central Gondwana remained free of continental glaciers. Still, in eastern Gondwana the Early Permian P1 and P2 continental glacial pulses spanned a total of some 14 million years of ice cover (table 5.1).

TABLE 5.2 Climatic events, area of rainforest coverage, and biological events during the transition from the latest Early Permian (Kungurian Age) to the earliest Middle Permian (Roadian Age).

| Age |

Geologic Time (Ma) |

Climatic Events |

Extent of Rainforests rainforests: |

Evolutionary Events |

| |

|

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

| WORDIAN |

266 |

ICE |

|

239,000 km2 |

|

| |

267 |

ICE |

|

227,000 km2 |

|

| |

268 |

ICE |

ICE? |

216,000 km2 |

|

| ROADIAN |

269 |

ICE |

ICE? |

194,000 km2 |

← Therapsid Radiation |

| |

270 |

ICE |

ICE? |

179,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Gap |

| |

271 |

ICE-P3 |

ICE? |

164,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Gap |

| |

272 |

|

ICE? |

150,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Gap |

| KUNGURIAN |

273 |

|

|

127,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Gap |

| |

274 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

← Olson’s Extinction |

| |

275 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

276 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

277 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

278 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| |

279 |

|

|

105,000 km2 |

|

| ARTINSKIAN |

280 |

|

|

332,000 km2 |

|

| |

281 |

|

|

482,000 km2 |

|

| |

282 |

|

|

633,000 km2 |

|

| |

283 |

|

|

784,000 km2 |

|

| |

284 |

ICE |

|

1,011,000 km2 |

|

| |

285 |

ICE |

|

1,115,000 km2 |

|

| |

286 |

ICE |

|

1,220,000 km2 |

|

| |

287 |

ICE |

|

1,325,000 km2 |

|

| |

288 |

ICE |

|

1,430,000 km2 |

|

| |

289 |

ICE |

|

1,690,000 km2 |

|

| |

290 |

ICE |

|

1,640,000 km2 |

|

| SAKMARIAN (pars) |

291 |

ICE |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

| |

292 |

ICE-P2 |

ICE? |

1,590,000 km2 |

|

Note: Climatic events column (2) is East Gondwana (Australia) in the Southern Hemisphere, and column (3) is Siberia (northeastern Russia) in the Northern Hemisphere; see table 5.1 for data sources.

But change was in the air. By the end of the Sakmarian, the ice cap in the Northern Hemisphere had melted away—if it existed!—and by the middle to late Artinskian, the P2 continental glaciation phase in eastern Gondwana had come to an end as well (table 5.1). The twilight of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had arrived.

THE MELTING OF THE ICE AGE

The Earth experienced a 12-million-year interpulse greenhouse period spanning the period of time from the middle of the Artinskian Age to the early Roadian Age.2 In the early Roadian Age, the planet once again cooled—but to a lesser extent than in any previous cooling event in the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. Two more phases of ice sheets formed in eastern Gondwana, but only in the highlands and mountains (table 5.1). The earlier phase of alpine glaciation, P3, was colder, and it has been argued that the last glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere also occurred at this time (Ustritsky 1973; Epshteyn 1981b; Chumakov 1994; Raymond and Metz 2004), but both events were brief on geologic timescales.

The last claim to continental glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere (table 5.1), like all of the others, has been challenged by John Isbell and colleagues. In this instance, they have actually shown that reportedly glacial, continental sedimentary deposits in northeastern Russia were in fact deepwater marine in nature and were formed by submarine gravity-flow slumps and turbidity currents—at least in three stratigraphic sections in the Okhotsk Basin (Isbell et al. 2016). Still, the very high latitude position of the northeastern tip of Russia in the Late Permian—almost positioned on the North Pole itself 3—makes it difficult to understand how it could have remained ice free while the Southern Hemisphere was glaciated (table 5.1). Isbell and colleagues note this climatic anomaly and state that “our findings constrain boundary conditions such that future climate modeling can better determine factors that allowed Gondwana glaciation to occur while inhibiting the development of land-based ice in Northeastern Asia” (Isbell et al. 2016, 297).

In the Southern Hemisphere, the last ice sheets in the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, the alpine glaciation phase P4 in eastern Gondwana, lasted for some five million years before they also melted away (table 5.1). The Late Paleozoic Ice Age had ended.

Why did the Late Paleozoic Ice Age end? One factor that contributed to its end was paleogeographic: the tectonic plate holding the giant continent of Gondwana was finally moving off of the South Pole (fig. 1.4). For over 110 million years, the South Pole—the coldest spot in the Southern Hemisphere—had been located on Gondwana, first in the west and then moving slowly and erratically to the east as the tectonic plate holding Gondwana shifted with time over the South Pole. By the end of the Permian, the South Pole had come to be located on the edge of eastern Gondwana—the southeast edge of present-day eastern Australia (fig. 1.4). The open oceanic waters of Panthalassa4—the “all ocean” or “world ocean” surrounding the single world continent Pangaea5—were located just offshore to the south, and they would have ameliorated temperature extremes on the neighboring continental margin just as oceanic waters do on continental margins today. As anyone knows who lives on a coastline near an ocean, summers are usually cooler and winters are usually warmer than they are in the continental interior. Cities like Chicago, located near large bodies of freshwater like Lake Michigan, also usually experience a smaller range of temperatures from summer to winter than cities like Tucson, surrounded only by land and rock. This effect occurs because water takes a long time to heat up and, once warm, takes a long time to cool down. The opposite is true of bare soil and rock—they heat up rapidly and become very hot in the summer, then just as rapidly lose heat and become very cold in the winter.

In figure 1.4 we saw that the position of the South Pole moved from the continental interior of Gondwana, present-day Antarctica, to the coastline about 265 million years ago. During the last phase of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age—the entire P4 glacial interval (table 5.1)—the South Pole was located near the southeastern margin of Gondwana and hence near the oceanic waters of Panthalassa. The entire P4 interval was also the least cold of the Permian phases of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, consisting of alpine glaciers in the highlands of Gondwana, and the continental ice sheets were unipolar, occurring only in the Southern Hemisphere.

Another factor that contributed to the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age was global climate change. The Earth became hotter and drier with the passage of time in the Late Permian, and this global climatic change also contributed to the death of the great lycophyte rainforests—a topic that will be examined in detail in the next section of the chapter. The P4 glacial pulse spanned the period from the late Capitanian to the mid Wuchiapingian (Metcalfe et al. 2015), and thus the beginning of the last glacial pulse of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age coincided in time with the Capitanian extinctions (table 5.1) (see Metcalfe et al. 2015, 75, fig. 14). The environmental trigger for the Capitanian biodiversity crisis will be explored in detail in the next chapter, but here it will be noted that massive volcanic eruptions also occurred in South China during the late Capitanian. The geographic area of these eruptions is known today as the Emeishan Large Igneous Province, and we have geochemical evidence that enormous amounts of carbon dioxide and methane—both powerful greenhouse gases—were vented into the Earth’s atmosphere in the late Capitanian. With an atmosphere laden with heat-trapping greenhouse gases, the entire Earth had to have become hotter, and not just in eastern Gondwana where the last of the P4 glaciers eventually melted.

THE END OF THE GREAT RAINFORESTS

Not only did massive glaciers return on the Earth at the dawn of the Permian, but the great lycophyte rainforests began to return as well. The extent of the rainforests increased by 168,000 square kilometers (64,848 square miles), or about 15 percent, at the beginning of the Asselian Age—from a low of 1,087,000 square kilometers (419,582 square miles) at the close of the Carboniferous to 1,255,000 square kilometers (484,430 square miles) when the ice sheets returned to Gondwana (table 5.1). The rainforests continued to expand in the Early Permian, reaching a maximum area of 1,690,000 square kilometers (652,340 square miles) in the early Artinskian Age (table 5.1). Thus the maximum extent of the Permian rainforests was comparable to the size of the rainforests present at the Bashkirian/Moscovian boundary in the Late Carboniferous (table 3.2), some 23 million years earlier. However, the maximum size of the Permian rainforests never quite reached the maximum of the Carboniferous rainforests, being 70 percent of the rainforest cover present on the Earth during the Moscovian Age (table 3.2).

As noted in chapter 3, the Permian rainforests were also more geographically restricted than those of the Carboniferous. Only in the far east, on the large islands of the Sino-Korean continental block (present-day Korea and North China) and the Yangtze continental block (present-day South China), did the lycophyte-dominated tropical mires continue to exist (fig. 3.7). The equatorial regions of Pangaea to the west, once covered by the lycophyte-dominated rainforests in the Carboniferous (fig. 3.7), were now populated by plants that had previously been found mostly in highland regions or in savannah environments in the lowlands (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

The Permian lycophyte rainforests began to decline in the Artinskian, coincident with the melting of the P2 continental glaciations (table 5.1). From that point onward, the rainforests were never larger in area than one million square kilometers, and they shrank in size by almost an entire order of magnitude—from 1,011,000 to 105,000 square kilometers (390,346 to 40,530 square miles)—in just five million years following the end of the P2 continental glaciation (table 5.1). Eventually the lycophyte rainforests vanished entirely on the island of the Yangtze continental block (fig. 3.7), and only to the north, on the Sino-Korean block, did the rainforests survive into the Kungurian. By the late Kungurian, the Sino-Korean rainforests had shrunk to just over 100,000 square kilometers (38,600 square miles)—about the size of the modern state of South Korea. The drastic reduction in the expanse of the Permian rainforests in the mid-Artinksian to late Kungurian had a devastating effect on the pelycosaurs, the non-therapsid synapsids; we will examine the demise of these tetrapods in detail in the next section of the chapter.

With the onset of the smaller P3 alpine glaciations in Gondwana, and perhaps the return of ice in the Northern Hemisphere, the rainforests recovered somewhat and expanded in size by almost a factor of four, reaching an extent of 395,000 square kilometers (152,470 square miles) by the dawn of the Wuchiapingian Age (table 5.1). This brief recovery can be attributed largely to the reestablishment and spread of the rainforests on the Yangtze continental block, as the Sino-Korean rainforests to the north remained the same size as they had been in the Kungurian (Cleal and Thomas 2005).

The rainforests began their final decline following the end of the P4 alpine glaciation in eastern Gondwana (table 5.1). By the end of the Wuchiapingian, the rainforests on the Sino-Korean continental block had vanished—only those on the island of the Yangtze block survived (Cleal and Thomas 2005). The paleobotanists Christopher Cleal and Barry Thomas argue that the lycophyte-dominated rainforests shrank during the Permian “as water-stress and increasing wildfires made the habitat unsuitable for the dominant lycophytes (Wang and Chen, 2001.) … Towards the end of the Permian, even drier conditions caused the forests to contract further, and increasing numbers are found of Mesophytic [drier adapted] plants…. This trend towards drier and hotter conditions may have been in part a consequence of the rain-shadow effect from the rising Northern Border Highlands to the north. However, Enos (1995) favoured the progressive drift north of [North] China, so that by the Changhsingian Age the area was outside of tropical latitudes. This is compatible with the persistence through the end of the Permian of some coal forests in South China, which were still in tropical latitudes” (Cleal and Thomas 2005, 21). That is, Cleal and Thomas attribute the paleoclimatic trend toward “drier and hotter conditions” in rainforest regions toward the end of the Permian to tectonic effects—both mountainous uplift on the Sino-Korean continental block and movement of the block to the north out of the equatorial region of the Earth.

But what if the trend toward hotter and drier conditions in the late Permian was global, occurring across the entire planet, and not just in the Sino-Korean region? In the next chapter we will examine the geological evidence that massive volcanic eruptions occurred on the Yangtze continental block during the late Capitanian, along with the geochemical evidence that enormous amounts of powerful greenhouse gases were vented into the Earth’s atmosphere beginning in the late Capitanian.

Regardless of the ultimate cause of the late Permian paleoclimatic trend toward hotter and drier conditions, by the mid-Changhsingian Age the Yangtze rainforests had also vanished. The great Late Paleozoic rainforests of the Earth were gone, and their 70-million-year history was at an end (tables 3.2 and 5.1).

THE PRELUDE TO DISASTER FOR PALEOZOIC LIFE

The close of the Early Permian Epoch saw a significant change in the synapsid amniote faunas of the world. Most of the long-lived and numerically dominant pelycosaurs, the non-therapsid synapsids (table 4.2), died out about 274 million years ago in the late Kungurian Age (table 5.1). This event has been named Olson’s extinction, and it does not appear to have been triggered by changes in the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere, as discussed in chapter 4.

The non-therapsids in the synapsid clade of amniote animals were ecologically replaced by the more derived therapsids—particularly the dinocephalian therapsids (table 4.2)—in the following late Roadian and Wordian Ages of the Middle Permian. However, as discussed in chapter 4, there exists a gap in geologic time spanning most of the Roadian Age—Olson’s Gap (table 5.2)—between the last of the sphenacodonts in the late Kungurian and the diversification of the dinocephalians in the late Roadian–Wordian (Lucas 2004; Blieck 2011). Thus, the more derived dinocephalians do not appear to have competitively displaced their older synapsid relatives in a case of active ecological replacement. Rather, the ecological replacement that did occur appears to have been passive—the dinocephalians simply moved into vacant ecospace created by the demise of the non-therapsid synapsids. The dinocephalians flourished in the Middle Permian, producing over 40 genera of both carnivorous and herbivorous animals, and some of the largest land animals to exist in the entire Permian, as discussed in chapter 4.

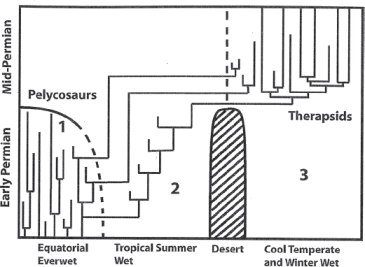

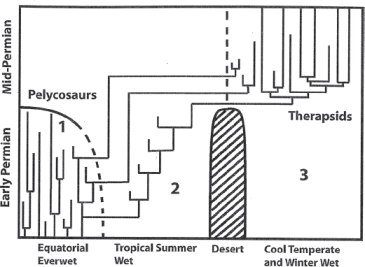

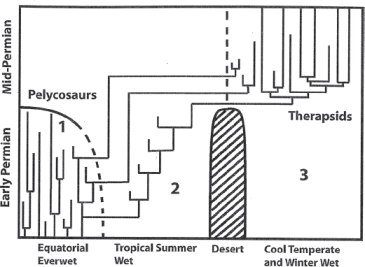

This standard passive-ecological-replacement model for the non-therapsid versus therapsid synapsids turnover has been questioned by Tom Kemp, a paleontologist at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. He has proposed a more nuanced model of ecological replacement for these two evolutionary faunas that contains both passive and active phases. First, he argues that the non-therapsid pelycosaurs (table 4.2) were adapted for life in the ever-warm, ever-wet, equatorial zone created by Late Paleozoic Ice Age climatic conditions (fig. 5.1) and that they experienced no selective pressures for lifestyle changes in these stable environments. The areal extent of the great rainforests—and the zone they inhabited—progressively shrank in the late Artinskian–early Roadian interval between the end of the P2 glaciation and the start of the P3 glaciation (table 5.2), and it is in this same interval of time that four of the six families of non-therapsids perished.6 Thus, the extinction of these non-therapsid families was driven by changing climatic conditions and was independent of any competition by the therapsids, which were to appear in numbers only later in the late Roadian of the Middle Permian (table 5.2).

FIGURE 5.1 Kemp’s paleoecological model for the evolution of the therapsid synapsids from the non-therapsid pelycosaurs during the Early to Middle Permian time interval; see text for discussion.

Source: From Kemp (2006), reprinted with permission.

Second, Kemp argues that one family of the Early Permian pelycosaurs, the predaceous sphenacodontids (figure 4.6), gave rise to the earliest therapsids—but not in the ever-warm, ever-wet equatorial zone. Instead, this evolutionary event took place in cooler and seasonally arid regions of the Earth—geographic regions that expanded in area during the P2–P3 interpulse greenhouse period. This seasonally arid, savanna-like environment Kemp labeled “tropical summer wet” (fig. 5.1), noting that not only did the first therapsids evolve there but the two remaining families of the non-therapsids, the Caseidae and Varanopidae, also migrated there as the equatorial ever-warm, ever-wet region shrank.

Third, Kemp argues that the early therapsids invaded even harsher environments—the cool-temperate/winter-wet zone—in the Middle Permian (fig. 5.1). Previously these higher-latitude regions were isolated from equatorial regions by the temperate-zone desert bands that formed in the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. As sea level fell with the return of expanding ice sheets of the P3 glaciation (table 5.2), the early therapsids were able to migrate north along the exposed east coastline of Laurussia and enter the higher-latitude regions. Kemp argued that the key to their spectacular success in this harsh region was the suite of morphological traits they had evolved in dealing with the less-harsh conditions of the cool and seasonally arid regions in which they had evolved. These traits included much higher metabolic rates and sustained activity levels, faster growth, and—most important—the ability to regulate their body temperatures to a greater degree than any previous synapsid group (as discussed in chapter 4). The therapsids rapidly diversified in this new environment, producing some nine new clades of both carnivores and herbivores (Kemp 2006).

Finally, Kemp notes that the fossil record shows that the last of the non-therapsids, the caseids and the varanopids, also managed to invade the cool temperate region and coexisted with the newly evolved therapsids for a few more million years (fig. 5.1). He argues that the last caseids and varanopids were eventually competitively displaced by the more-advanced therapsids; thus, the final extinction of the last of the non-therapsid pelycosaurs was the result of active ecological replacement, not passive like the initial extinction of four entire families of pelycosaurs in the Early Permian.

Whatever its ultimate cause, Olson’s extinction triggered the loss of some two-thirds of the biodiversity of terrestrial vertebrates and thus was not a trivial event (Sahney and Benton 2008; Blieck 2011). Other clades of land animals—not just the synapsid amniotes—were also affected by contraction of the ever-warm, ever-wet, equatorial zone that occurred in the late Artinskian–early Roadian interval of the Early Permian. Ecological diversity was also lost: post-Olson’s-extinction vertebrate communities possessed a lower number of guilds than in any other period of Permian history, being comprised almost entirely of piscivorous carnivores and browsing herbivores (Sahney and Benton 2008).

But what about Olson’s Gap—a hiatus in the fossil record that the University of Lille paleontologist Alain Blieck describes as being of global extent and having a duration equivalent to most of Roadian time (Blieck 2011, 207)? This gap in the fossil record occurs in phase 2 of Kemp’s ecological replacement model (fig. 5.1)—namely, the period of time in which the first therapsids are modeled as having evolved from— some of the last sphenacodontids, an event that took place in seasonally arid, savanna-like environments only marginal to the usual geographic range of the sphenacodontids. The oldest known therapsid species is the basal biarmosuchian Tetraceratops insignis (table 4.2) found in Early Permian strata in Texas in North America (Benton 2005, 2015; McGhee 2013), yet the fossil appearance of the oldest Middle Permian therapsid species is far away to the east in Russia (Kemp 2006). Olson’s Gap may be a preservational artifact; that is, the late Kungurian and early Roadian newly evolved therapsid species may have existed in such small population sizes that they had a very low probability of preservation in the fossil record.

On the other hand, Olson’s Gap might be a real ecological-evolutionary phenomenon and not a preservational artifact. The University of Bristol paleontologists Sarda Sahney and Michael Benton argue that “Olson’s extinction was a dramatic extinction ‘trough’ that is a prolonged period of very low diversity after a long and sustained diversity rise and probably the result of prolonged environmental stress” (Sahney and Benton 2008, 761). That is, the low diversity of fossils found in the strata during the period of Olson’s Gap did not result from a failure of representation of the actual diversity of species because of small population sizes of those species, and hence a low probability of their begin preserved in the fossil record; rather, the low diversity of fossils actually records the low diversity of species present on the Earth during the Olson’s Gap period of time.

In contrast to extinction and biodiversity loss on land at the end of the Early Permian, life in the oceans was rebounding from the long period of evolutionary stagnation triggered by the Serpukhovian crisis that we examined in detail in chapter 2. Starting in the early Sakmarian Age (Stanley 2007), species diversity in marine ecosystems steadily increased through the remainder of the Early Permian and through the Middle Permian up to the middle of the Capitanian Age. That is, while on land the glaciers slowly melted away and the great equatorial rainforests progressively shrank to critical minimum levels during the late Early and early Middle Permian (table 5.2), in the oceans normal evolutionary turnover rates returned, diverse ecological specialist species re-evolved, and rising sea levels created new shallow-water habitats on the continents that were invaded by marine life around the Earth.

At the beginning of the Capitanian Age, life was good not only in the oceans but also on land as therapsid species continued to diversify in the cool-temperate zones of the Earth. Then the Earth began to heat up more rapidly than ever seen in any of the interpulse greenhouse periods of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. In the oceans, dead regions of oxygen-depleted waters formed and marine species began to go extinct around the world. On land, arid desert regions began to expand, driving plant and animal species to extinction. Even in the wet regions of the Earth, plant and animal species mysteriously began to go extinct. The Capitanian crisis had begun.

My colleagues Matthew Clapham, Peter Sheehan, Dave Bottjer, and Mary Droser and I have demonstrated that global ecosystems of the world began to collapse during the Capitanian Age, triggering the fifth-most-severe ecological disruption in the Phanerozoic Eon (table 1.3) (McGhee et al. 2013). In the oceans, the ecological impact of the Capitanian biodiversity crisis at the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age was greater than that of the Serpukhovian crisis at the beginning of the “Big Chill” phase of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age (table 2.2), but not as great as that of the Late Devonian biodiversity crisis at the onset of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age (table 1.3)—that is, if the Late Devonian crisis marked the onset of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, a controversy discussed in chapter 1. On land, Sahney and Benton note that “the ecological impact of the Guadalupian [Middle Permian] events is catastrophic; 8 (out of a possible 12) guilds are lost from the Artinskian high of 10 guilds. These are recovered in the last stages of the Permian before being devastated again by the end-Permian event…. A dramatic change in diet type also occurs: proportions of piscivores, insectivores, predators and browsers are thrown out of balance during each extinction pulse” (Sahney and Benton 2008, 761).

Then, as if the Capitanian crisis were not enough, Peter Sheehan, Dave Bottjer, Mary Droser, and I have determined that the ecological impact of the end-Permian mass extinction—in both marine and terrestrial ecosystems—was the worst ecological catastrophe in Earth history (McGhee et al. 2004). The magnitude of the ecological disruption triggered by the end-Permian mass extinction was so great that recovery was impossible—the world of the Paleozoic Era came to an end.

What possible catastrophes could have happened on the Earth in the Permian that would have had such a devastating effect that they triggered the fifth-most-severe and first-most-severe ecological crises in Earth history (table 1.3) in the short time span of only seven million years (table 5.1)? To readers who subscribe to the Gaia hypothesis—that the geochemical and biochemical cycles of the Earth are buffered to protect and nurture life—the answer to that question will be shocking, and that horrific answer will be examined in detail in chapter 6.