There were giants in the Earth in those days …

—Genesis 6:4 (King James version)

THE STRANGE CARBONIFEROUS ANIMALS

The writer of the book of Genesis states that there were giants in the Earth in the early days following the creation. In the chronology outlined in Genesis, those giants existed about 6,000 years ago. In actual fact, the first giant land animals on the Earth existed in the Carboniferous, some 345 million years ago. Both on the land and in the seas, animals began appearing in the Carboniferous that were much larger than any living modern-day counterparts—in some cases, as much as ten to 12 times larger! In this chapter we will examine the empirical evidence for the evolution of animal gigantism in the Carboniferous and then explore the possible causes of that gigantism.

Giant Arthropods

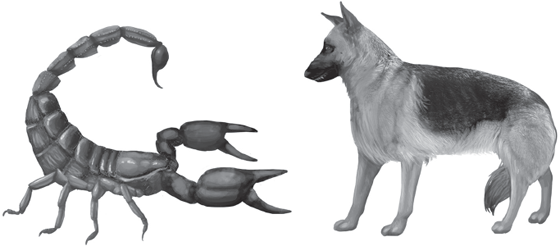

The Carboniferous giant arthropods (table 4.1) began to appear in the Visean Age, not long after the end of the Tournaisian Gap. One notable example is the fossil of a giant scorpion, Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis, discovered in East Kirkton in Scotland, that was 700 millimeters (28 inches) long. Here in North America, different living species of scorpions range in length from 37 to 127 millimeters (1.5 to five inches), and the “giant desert hairy scorpion” of the Southwest, Hadrurus arizonensis, reaches a length of 140 millimeters (5.5 inches) (Milne and Milne 1980). In comparison with Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis, we can see that our modern “giant” scorpion is no giant at all—the Carboniferous scorpion was fully five times larger! Imagine hiking in the Arizona desert today and encountering a real giant scorpion, one that is as long as a midsize dog (fig. 4.1). How could a scorpion have achieved such a gigantic size? Yet it was only a harbinger of what was to come.

TABLE 4.1 Terrestrial arthropod lineages of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| ARTHROPODA (jointed appendages) |

| – CHELICERIFORMES |

| – – Chelicerata |

| – – – MEROSTOMATA (sea scorpions and kin) |

| – – – – – Water scorpion giants |

| – – – ARACHNIDA (scorpions and spiders) |

| – – – – – Scorpion, trigonotarbid, spider giants |

| – MANDIBULATA |

| – – MYRIAPODA (multi-legged) |

| – – – Diplopoda (millipedes) |

| – – – – Arthropleurid giants |

| – – – Chilopoda (centipedes) |

| – – PANCRUSTACEA |

| – – – Hexapoda (six-legged) |

| – – – – Entognatha |

| – – – – – Dipluran giants |

| – – – – INSECTA (insects) |

| – – – – – basal insects |

| – – – – – – Silverfish giants |

| – – – – – PTERYGOTA (winged insects, conquerors of the land) |

| – – – – – – Ephemeroptera (mayflies) |

| – – – – – – – Mayfly giants |

| – – – – – – Metapterygota |

| – – – – – – – Odonatoptera (dragonflies, damselflies) |

| – – – – – – – – Meganisoptera |

| – – – – – – – – – Griffenfly giants |

| – – – – – – – Palaeodictyopterida |

| – – – – – – – – Palaeodictyopteran sap-sucker giants |

| – – – – – – – NEOPTERA (folding-wing insects) |

| – – – – – – – – Cockroach giants |

Source: Phylogenetic classification modified from Grimaldi and Engel (2005) and Lecointre and Le Guyader (2006).

Note: Taxa containing giants are in italics; major clades are in capitals.

FIGURE 4.1 Some Late Paleozoic scorpions, such as the Early Carboniferous Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis, were as long as a midsize dog.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

Giant arthropods really started becoming numerous on the Earth in the Moscovian Age of the Late Carboniferous. Close relatives of the scorpions, spiders and their ancient kin began to achieve gigantic sizes. The extinct trigonotarbids were morphologically very similar to modern spiders, but they did not possess silk glands to spin webs. They started out small in the Devonian, from two to 15 millimeters (0.08 to 0.6 inch) long, not unlike modern spiders. In the Late Carboniferous, however, trigonotarbids evolved that were 50 millimeters (two inches) long—more than three times larger than the largest Devonian trigonotarbids (Shear and Kukalová-Peck 1990). A gigantic spider, Megarachne servinei from Argentina, had a leg span of almost 500 millimeters (20 inches) (Shear and Kukalová-Peck 1990; Lane 2002).1 For those who are arachnophobic, just imagine encountering a spider over a foot and a half long!

Other giant Moscovian arthropods include the 2.5-meter- (eight-foot-) long millipede species Arthropleura armata and A. mammata, animals that were 150 millimeters (six inches) wide and weighed up to ten kilograms (22 pounds) (Kraus and Brauckmann 2003).2 Most millipede species today are tiny, slender animals about 50 millimeters (two inches) long; our largest species today, the African “giant black millipede” Archispirostreptus gigas, can reach 385 millimeters (15 inches) in length and 20 millimeters (0.8 inch) in width. Once again, we see that our modern “giant” arthropod species is not a giant—the Carboniferous millipede species were six and a half times larger! In fact, the Carboniferous millipedes were fully as long as a modern alligator (fig. 4.2).

FIGURE 4.2 Some Late Paleozoic millipedes, such as the Late Carboniferous Arthropleura armata, were as long as a modern alligator.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

The hexapods and insects also began to evolve species with unprecedented body sizes in the Late Carboniferous (table 4.1). The forcipate diplurans (Entognatha; table 4.1) are usually very small cryptic insects, hiding under logs and leaves on the ground, and are generally four to six millimeters (about one-sixth to one-fourth of an inch) long (Milne and Milne 1980). The gigantic forcipate dipluran species Testajapyx thomasi, found in Moscovian-aged Mazon Creek strata in Illinois, was 58 millimeters (2.3 inches) long, including a 48-millimeter body and ten-millimeter antennae (Kukalová-Peck 1987). On average, the Late Carboniferous Testajapyx thomasi was 12 times larger than living forcipate diplurans! In the same Mazon Creek strata are found gigantic silverfish insects (basal insects; table 4.1), the species Ramsdelepidion schusteri, that are 60 millimeters (2.4 inches) long. Modern silverfish species can often become pests, living in moist regions of the house, such as under sinks or around water pipes, and emerging at night to feed on book bindings or clothes—but their silvery, flattish bodies are usually small, around nine to 13 millimeters (one-third to one-half inch) long (Milne and Milne 1980). On average, the Late Carboniferous silverfish were more than five times larger—imagine finding a silverfish the length of your little finger munching on your favorite book!

The ground-dwelling millipede and insect giants were not alone. Giant insects flew in the skies of the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian (table 4.1). The most primitive of the living flying insects are the Ephemeroptera, the mayflies (table 4.1). Modern mayflies live for only one day, hence their scientific name “ephemeral wings.” The mayfly itself is merely the mobile, reproductive phase of the species—after mating and laying their eggs, they die. The Carboniferous mayflies, however, possessed functioning biting mouthparts and clearly fed as adults, not just as aquatic nymphs. And they were gigantic: the Moscovian Age mayfly species Bojophlebia prokopi had a wingspan of 450 millimeters (18 inches) (Kukalová-Peck 1985). In contrast, the largest living mayflies in North America, the golden mayflies, can have a wingspan up to 60 millimeters (2.4 inches)—the Carboniferous mayfly Bojophlebia prokopi was over seven times larger. In fact, the wingspan of Bojophlebia prokopi was as wide as that of a modern midsize bird, such as a blue jay, rather than an insect.

Astonishingly, even larger flying insects existed in the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian. The most impressive of these were the meganisopterans, the griffenflies (table 4.1), which were flying predators similar in appearance to modern-day dragonflies—but much bigger. Giant griffenflies, such as the Chinese griffenfly Shenzhousia qilianshanensis, which had a wingspan of 499 millimeters (20 inches), began to appear in the Bashkirian.3 The Moscovian griffenfly Bohemiatupus elegans in Europe was larger, with a wingspan of 552 millimeters (22 inches), and the Kasimovian-Gzhelian griffenfly Meganeura monyi was even larger, with a wingspan of 628 millimeters (two feet) (Clapham and Kerr 2012). In the Early Permian, some griffenflies were larger still, the largest being the Asselian-Artinskian Meganeuropsis permiana with a wingspan up to 720 millimeters (28 inches) (Grimaldi and Engel 2005; Clapham and Kerr 2012). Giant griffenflies persisted into the beginning of the Middle Permian with the presence of Arctotypus sp., with a wingspan of 489 millimeters (19 inches) (Clapham and Kerr 2012).

The largest dragonfly in North America—again, like the “giant desert hairy scorpion,” found in the Southwest—is the Walsingham’s Darner, Anax walsinghami, with a wingspan of 150 millimeters (six inches) (Milne and Milne 1980). The largest living dragonfly, the Australian species Petalura ingentissima, is slightly larger, with a wingspan of 168 millimeters (6.6 inches) (Dorrington 2015). Similar to our comparison of modern and Carboniferous scorpions, which were five times larger, the wingspan of the Carboniferous and Permian griffenflies was almost five times that of our largest living dragonflies. In fact, these griffenflies had a wingspan more similar to that of a large modern bird, such as a magpie or a gull (fig. 4.3), than a living dragonfly. Instead of being dive-bombed by hungry gulls at the beach, eager to snatch a French fry from your hand, imagine encountering similar-sized dragonflies!

FIGURE 4.3 Some Late Paleozoic dragonfly-like insects, such as the Early Permian Meganeuropsis permiana, had wingspans as wide as a modern seagull.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

Not only were there giant flying predatory insects in the Late Carboniferous, but the flying herbivorous insects were gigantic as well. These include the Moscovian palaeodictyopteran species Mazothairos enormis (table 4.1) from Mazon Creek strata in Illinois, which had a wingspan of up to 600 millimeters (two feet) and thus was aptly given the species name “enormous.” These ancient insects did not eat energy-rich animal protein or fat like a griffenfly; they survived on tree sap. Yet these Carboniferous sap-suckers still achieved gigantic sizes (Grimaldi and Engel 2005). Our largest living sap-sucking flying insect, the Malaysian cicada species Pomponia imperatoria, has a wingspan of 200 millimeters (eight inches)—the Carboniferous flying sap-suckers were three times larger.

Not all of the giant Carboniferous insects were larger than their modern relatives. For example, the modern living cockroach Blaberus giganteus of Central America and northern South America is fully 90 millimeters (3.5 inches) long, a size not exceeded by the large Carboniferous roachoids, or cockroach-like insects. However, and in summary, many of the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian arthropod species had body sizes that were five to seven times larger than their modern-day counterparts, and an overall size range from three to as much as 12 times larger.

What type of an Earth could have produced such huge arthropods? How could such gigantic scorpions, millipedes, spiders, silverfish, mayflies, griffenflies, and cicada-like sap-suckers have existed? Gigantism convergently evolved in multiple phylogenetic lineages of arthropods in the Carboniferous: it appeared independently in the two clades of the cheliceriform and the mandibulate arthropods, independently in the myriapod and pancrustacean clades within the mandibulates, and independently within multiple separate insect clades (table 4.1). To make matters even more mysterious, there were other giant animals on the Earth in this interval of geologic time, as we will see in the next section.

Giant Vertebrates

The giant Carboniferous arthropods were not alone—many of the Late Carboniferous tetrapod vertebrates were also gigantic (table 4.2), at least in comparison to their Early Carboniferous ancestors. The majority of the tetrapod species of the Early Carboniferous were small animals, usually only about 300 millimeters (one foot) in total length. In contrast, many of the newly evolved tetrapods of the Late Carboniferous were ten times larger: they were often three meters (3,000 millimeters, or ten feet) long. And, as with the insects, the attainment of large body sizes in the Late Carboniferous tetrapods was independent of diet: both carnivores and herbivores were big animals.

TABLE 4.2 Terrestrial vertebrate lineages of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| TETRAPODA (limbed vertebrates) |

| – basal tetrapods |

| – Neotetrapoda |

| – – BATRACHOMORPHA (ancestors of living amphibians) |

| – – – basal batrachomorphs (“temnospondyls”) |

| – – – – Eryopid giants |

| – – REPTILIOMORPHA (ancestors of amniote tetrapods) |

| – – – basal reptiliomorphs (“anthracosaurs”) |

| – – – Seymouriamorpha |

| – – – Diadectomorph giants |

| – – – AMNIOTA (amniote tetrapods, conquerors of the land) |

| – – – – SYNAPSIDA (ancient ancestors of mammals) |

| – – – – – basal synapsids (“pelycosaurs”) |

| – – – – – – Caseid, ophiacodont, edaphosaur, sphenacodont giants |

| – – – – – THERAPSIDA (closer ancestors of mammals) |

| – – – – – – Biarmosuchia (basal therapsids) |

| – – – – – – Dinocephalian giants |

| – – – – – – Dicynodontia |

| – – – – – – Gorgonopsia |

| – – – – – – Therocephalia |

| – – – – – – – CYNODONTIA (very close ancestors of mammals) |

| – – – – REPTILIA (ancestors of living reptiles) |

| – – – – – PARAREPTILIA |

| – – – – – – Pareiasaur giants |

| – – – – – EUREPTILIA |

| – – – – – – Captorhinid giants |

| – – – – – – DIAPSIDA (ancestors of living lepidosaurs, archosaurs, and dinosaurs—the birds) |

Source: Phylogenetic classificaton modified from Benton (2015).

Note: Taxa containing giants are in italics; older paraphyletic tetrapod group names are in quotation marks; major clades are in capitals.

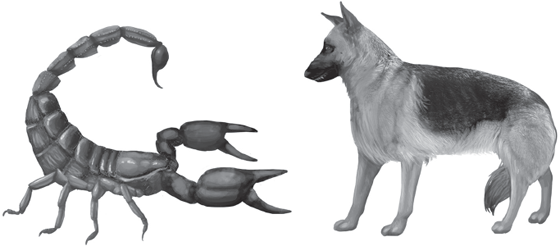

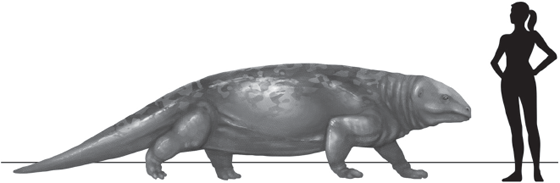

Vertebrates began the invasion of land in earnest in the Visean Age of the Early Carboniferous, following the catastrophe of the end-Devonian tetrapod extinctions and the long Tournaisian Gap (table 1.7) (McGhee 2013). The first of the batrachomorphs, the ancestors of modern-day amphibians, and of the reptiliomorphs, the ancestors of modern-day amniote animals like mammals, reptiles, and birds, appear in the fossil record at this time (table 4.2).4 The basal batrachomorphs are represented in the Visean by a single species, Balanerpeton woodi, from East Kirkton in Scotland. Individuals of this species were small, averaging about 200 millimeters (eight inches) long, and looked much like salamanders (Steyer 2012). Later, in the Early Permian, the batrachomorphs would evolve the giant Eryops megacephalus—its species name means “very large headed”—which, at 2,000 millimeters (6.6 feet) long, was ten times bigger than Balanerpeton woodi. Eryops megacephalus looked nothing like a harmless salamander—it had a massive body with thick legs (fig. 4.4), and its large head had a mouth full of sharp teeth including extra fang teeth located in the palate in the roof of its mouth—it was a deadly predator (Steyer 2012).

FIGURE 4.4 Some Late Paleozoic salamander-like amphibians, such as the Early Permian Eryops megacephalus, were two meters (6.6 feet) long.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

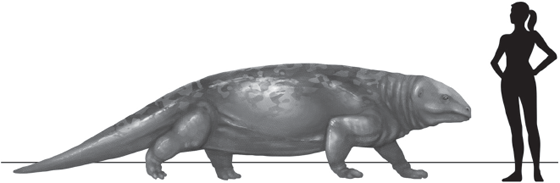

The reptiliomorph clade is represented by several different species in the Visean Age, of which Silvanerpeton miripedes, Eldeceeon rolfei, and Westlothiana lizziae are found in the East Kirkton strata along with the batrachomorph species Balanerpeton woodi. These reptiliomorphs were also small, with body lengths, from snout to pelvis, of only about 200 millimeters (eight inches). The tail vertebrae are missing from the fossils, so the precise length of their tails is unknown, but the total length of these early reptiliomorphs was probably only around 300 millimeters (one foot). Later, in the Late Carboniferous, the diadectomorph reptiliomorphs would evolve the giant Diadectes maximus—its species name means “the greatest”—that, as with the batrachomorph lineage, was ten times larger than the early reptiliomorphs. Rather than 300 millimeters (one foot), Diadectes maximus was fully 3,000 millimeters (ten feet) long (fig. 4.5). Diadectes maximus is also very interesting in that it is the oldest known fossil tetrapod species to have evolved herbivory—it was a plant-eater, rather than a carnivore (Steyer 2012).

FIGURE 4.5 Some Late Paleozoic plant-eating reptile-like animals, such as the Late Carboniferous Diadectes maximus, were three meters (ten feet) long.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

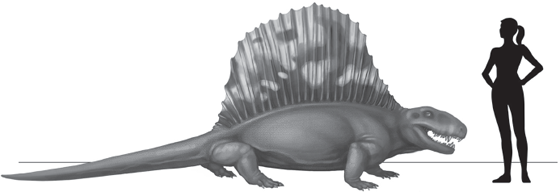

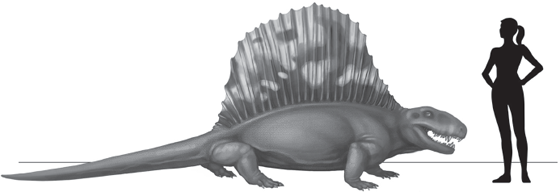

It is from the early reptiliomorphs that the two amniote clades evolved—the synapsids, ancestors of modern-day mammals, and the reptilians, ancestors of modern-day reptiles and birds (table 4.2). Within our own phylogenetic lineage, the synapsids, giant predatory ophiacodonts began to appear in the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian: Ophiacodon uniformis was 2.5 meters (eight feet) long. In this same interval of time, giant edaphosaurs and sphenacodonts began to appear: Edaphosaurus cruciger was 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) long, and Dimetrodon grandis—its species name means “great size”—was three meters (ten feet) long (fig. 4.6). The ophiacodonts and sphenacodonts were large carnivores, but the edaphosaurs were herbivorous; thus, as in the arthropod lineages, the evolution of giant body sizes was not linked to diet. In the Middle Permian, the herbivorous caseid synapsids (table 4.2) would evolve species of Cotylorhynchus that were three meters (ten feet) long, and the dinocephalian therapsids would produce the giant Moschops herbivores that were fully five meters (16.4 feet) long, the largest land vertebrates in the Paleozoic (Benton 2015). The dinocephalians—the group name means “terrible headed”—were bizarrely shaped with massive, barrel-chested bodies but quite short, stocky legs (fig. 4.7). Given their massively built skulls, it has been suggested that these animals butted their heads together in ritual combat during the mating season, much like modern-day goats and sheep (Benton 2015).

FIGURE 4.6 Some of our Late Paleozoic synapsid cousins, such as the carnivore Dimetrodon grandis, were sail-finned giants more than three meters (ten feet) long.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

FIGURE 4.7 Some of our Late Paleozoic therapsid cousins, such as the Middle Permian Moschops herbivores, were the largest land vertebrates in the Paleozoic, twice the size of a modern cow.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

Curiously, the other amniote clade, the reptilians, apparently did not evolve giant individuals until the Late Permian. The parareptiles (table 4.2) produced the pareiasaurs with massive, elephant-like legs; muscular humps on their backs associated with thick neck muscles; and odd knobby, hornlike protrusions on their skulls. The African pareiasaur Bunostegos akokanensis was three meters (ten feet) long (Steyer 2012). Also in the Late Permian, the African captorhinid reptiles (table 4.2) produced giants like Moradisaurus grandis—again, the species name means “great size”—which were two meters (6.6 feet) long (Steyer 2012).

Giant Marine Invertebrates

Giant animals also appeared in marine and coastal ecosystems in the Carboniferous. Not only did the giant 700-millimeter- (28-inch-) long Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis scorpions appear on land, but some of their water-scorpion cousins (table 4.1) were over three times as large! In coastal estuaries and rivers in the Devonian and Early Carboniferous, one could encounter water scorpions up to 2.5 meters (eight feet) long, such as the giant Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (fig. 4.8) (Braddy et al. 2007; Steyer 2012, 67; Palmer et al. 2012, 122).

FIGURE 4.8 Some Late Paleozoic water scorpions, such as the Devonian Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, were over 2.5 meters (eight feet) long.

Source: Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.

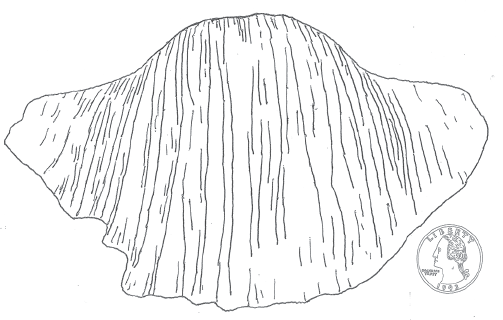

Out in the open oceans of the world, the largest brachiopod shellfish known in Earth history appeared—Gigantoproductus giganteus, an animal aptly named the “gigantic giant Productus” (see table 4.3 for the phylogenetic position of brachiopods). The shell of the Early Carboniferous Gigantoproductus giganteus was 300 millimeters (one foot) wide (fig. 4.9) (Newell 1949; Clarkson 1998; Qiao and Shen 2015). In contrast, the shell of an average productid brachiopod in the Late Devonian seas was only about the size of a quarter,5 fully 15 times smaller than Gigantoproductus giganteus (fig. 4.9).

TABLE 4.3 Marine invertebrate lineages of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

| EUKARYA (life with eukaryote cells) |

| – Bikonta (biflagellate single cells) |

| – – Chromoalveolata (“brown algae” and kin) |

| – – – Dinophyta (dinoflagellates) |

| – – Rhizaria |

| – – – Foraminifera |

| – – – – Fusulinid giants |

| – Unikonta (uniflagellate single cells) |

| – – Choanozoa |

| – – – METAZOA (multicellular animals) |

| – – – – Cnidaria (diploblastic metazoans) |

| – – – – – Coral giants |

| – – – – BILATERIA (triploblastic metazoans with bilateral symmetry) |

| – – – – – PROTOSTOMIA (bilaterians with protostomous development) |

| – – – – – – Lophotrochozoa |

| – – – – – – – Lophophorata |

| – – – – – – – – Bryozoa |

| – – – – – – – – – Bryozoan giants |

| – – – – – – – – Brachiopoda |

| – – – – – – – – – Brachiopod giants |

| – – – – – – – Eutrochozoa |

| – – – – – – – – Mollusca |

| – – – – – – – – – Ammonoid giants |

| – – – – – – – – – Bivalve giants |

| – – – – – – Ecdysozoa (see table 4.1 for arthropod giants) |

| – – – – – DEUTEROSTOMIA (bilaterians with deuterostomous development) |

| – – – – – – Echinodermata |

| – – – – – – – Crinoid giants |

| – – – – – – – Echinoid giants |

| – – – – – – Chordata (see table 4.2 for vertebrate giants) |

Source: Phylogenetic classification modified from Lecointre and Le Guyader (2006).

Note: Taxa containing giants are in italics; major clades are in capitals.

FIGURE 4.9 Some Late Paleozoic marine shellfish, such as the Early Carboniferous brachiopod Gigantoproductus giganteus, had shells that were 300 millimeters (one foot) wide. In contrast, average productid brachiopod shells in the Late Devonian were about the size of a quarter (lower right).

Source: Modified and redrawn from Brunton, Lazarev, and Grant (2000).

Fossils of productid brachiopods are so numerous in Carboniferous marine strata that the Carboniferous seas were often referred to as “Productus seas” in older historical geology textbooks (Tasch 1973, 297), and many of the Carboniferous species were giants. And gigantism did not just occur in the ecological niche of the productid brachiopods, which lived mostly buried and hidden in the sediment. The fully epifaunal brachiopods—such as species of Punctospirifer—which lived exposed on the seafloor (and thus more vulnerable to predator attack) exhibited fivefold increases in size in the Late Carboniferous to Middle Permian time span. This size-increase trend is so notable that Norman Newell, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History, commented: “The trend for increasing size during the late Paleozoic is well shown by a large number of brachiopod genera. Most of these begin in the early Pennsylvanian or late Mississippian and show progressive increase in linear dimensions throughout the Pennsylvanian and Permian” (Newell 1949, 110–111).

The bryozoans—filter-feeding lophophorates (table 4.3) like the brachiopod shellfish, but colonial rather than solitary—also experienced size increases during the Late Carboniferous to Middle Permian time span. Specifically, the diameters of the zooecial openings in the colony skeletons—a rough measure of the size of the actual tiny zooid individuals that lived in the numerous branches of the colony—increased by 100 percent from the Kasimovian to the Roadian (Newell 1949, 109). Gigantism was not confined to the clade of the lophophorates: in the filter-feeding echinoderm sea lily (crinoid, table 4.3) genus Calceolispongia, the volume of the basal plate of the calyx skeleton of the animal increased from two cubic millimeters (0.08 cubic inches) to 800 cubic millimeters (2.6 cubic feet) during the Artinskian Age in the Early Permian. If changes in the volume of the basal plate of the calyx skeleton are taken as a rough proportional measure of biomass-volume changes of the total animal, then the biomass volume in these crinoid species increased by a factor of 400 during the Early Permian (Newell 1949, 112). Some mobile echinoderm groups also experienced more than a tripling in size: species of the sea urchin (echinoid, table 4.3) order Melonechinoida increased in size from a diameter of 45 millimeters (1.8 inches) in the genus Palaeechinus to 155 millimeters (six inches) in the genus Melonechinus in the span of time from the Tournaisian to Visean Ages in the Early Carboniferous (Newell 1949, 111–112).

Predatory marine animals also experienced gigantism in the Carboniferous. The sessile rugose coral species, such as Zaphrentis, typically had horn- or conelike skeletons about 15 millimeters (0.6 inch) high in the Devonian, whereas the Devonian-Carboniferous Canina species had skeletons 100 millimeters (four inches) high and Siphonophyllia species had even larger skeletons at 750 millimeters (30 inches) high—a fiftyfold increase in height from the Devonian Zaphrentis (Newell 1949, 108). The swimming, squidlike ammonoid predators generally had phragmocones—the section of the shell containing the main biomass of the animal—with a maximum diameter of about 75 millimeters (three inches) in the Devonian and Early Carboniferous, rarely ranging up to a diameter of 150 millimeters (six inches). In contrast, in the Permian, ammonoid species with phragmocone diameters of 150 millimeters were common in several different families of these predators, and species of Medliocottia and Cyclolobus possessed phragmocones with diameters of 250 millimeters (almost ten inches)—over three times larger than those in the Devonian (Newell 1949, 114).

Probably the most astonishing examples of gigantism that occurred in marine organisms during the Carboniferous and Permian are organisms that were not even multicellular animals, but single-celled fusilinid foraminifera (table 4.3). These single-celled organisms grew tiny, lenticular coiled shells about 0.5 millimeters (0.02 inch) in axial diameter—about the size of the period at the end of this sentence—in the Serpukhovian Age of the Early Carboniferous. They then progressively evolved numerous species and genera whose axial lengths increased to the “acme in microscopic giants (Parafusulina kingorum Dunbar and Skinner)” (Newell 1949, 106) in the Early to Middle Permian, a species that had an axial length of 60 millimeters (2.4 inches)—an increase in size by a factor of 120 from the Early Carboniferous. This organism—a single cell—was almost three times the width of a quarter (fig. 4.10).

FIGURE 4.10 Some Late Paleozoic single-celled organisms, like the Early Permian marine foraminifera Parafusulina kingorum, were 60 millimeters (2.4 inches) long and almost three times the width of a quarter. In contrast, average foraminifers in the Early Carboniferous were about the size of the period at the end of this sentence.

Source: Modified and redrawn from Hoskins, Inners, and Harper (1983).

A complicating factor in fusulinid gigantism is that these foraminifera harbored symbiotic photosynthetic algae in their tissues—that is, they harbored an extra source of food—and this trait may have contributed to their ability to become giants. This trait is mirrored by another astonishing example of invertebrate gigantism—the living Tridacna gigas bivalve molluscs with shells over one meter (3.3 feet) in diameter. The Permian gigantic bivalves (table 4.3) of the family Alatoconchidae (Aljinovic et al. 2008; Isozaki and Aljinovic 2009) are also believed to have harbored photosynthetic algae as symbionts in their tissues. We will reconsider both the fusulinids and the alatoconchid bivalves in more detail in the ecosystem evolution and animal gigantism section later in the chapter.

THE CARBONIFEROUS OXYGEN PULSE AND ANIMAL GIGANTISM

The trigger for the evolution of animal gigantism in the Carboniferous had to have been some globally pervasive change in the Earth’s environment because that gigantism appeared independently, convergently, in the separate phylogenetic lineages of both the arthropods (table 4.1) and the vertebrates (table 4.2), and it occurred in the same interval of geologic time for both of these separate phylogenetic lineages. Arthropods and vertebrates are radically different types of animals—arthropods are protostomous animals and vertebrates are deuterostomous—and you have to go back in time all the way to the Neoproterozoic to find a common ancestor.6 That is, the lineages of the protostomous and deuterostomous animals diverged back in the Neoproterozoic, meaning that the arthropods and vertebrates are separated by a vast chasm of more than 660 million years of independent evolution. Yet both of these independent lineages began to evolve giant animals in the Carboniferous—why?

Arthropods and Oxygen

The breathing system used by the insect species offers the best clue to solving the mystery of Carboniferous animal gigantism. Insects breathe with a series of small tubes, the tracheae, that extend from pore-like openings in their exoskeletons down into their body tissues. The insect depends entirely upon diffusion of oxygen in from these tubules (and reverse diffusion of carbon dioxide out of the tubules) to keep their tissues alive. This system of breathing is strongly size limiting. Larger and larger insects have larger and larger volumes of internal tissue, tissues that depend upon the surface areas of the tiny tracheae for gas exchange. With increasing size, the volume of any object increases as a cubic function of linear dimension, whereas surface area increases only as a square function. This constraint—the area-volume effect—means that insects are constrained to sizes small enough to have the proper ratio of internal tissue volume to surface area of tracheal tubes (Harrison et al. 2010).

The area-volume problem is even more acute for flying insects—flying is a highly energetic activity that requires a lot of oxygen. And larger, heavier insects require even more energy—and oxygen—to fly than smaller insects. Thus how could a dragonfly-like insect with a wingspan of almost three-quarters of a meter (fig. 4.3) have existed in the Late Paleozoic? It should have suffocated under its own mass, its tracheae unable to aerate its large volume of internal tissues. But what if the atmosphere had more oxygen in it than it presently does? An atmosphere with a higher partial pressure of oxygen—more oxygen molecules concentrated in a given volume of air—could potentially lift the constraint of the area-volume effect to higher ratios of tissue volume to tracheal surface area, thus making possible the existence of much larger insects (Dudley 1998; Harrison et al. 2010).

The mystery of giant-arthropod breathing deepens when it is revealed that the gigantic Arthropleura millipedes (fig. 4.2) had no tracheae at all! How could they breathe without tracheae? The zoologist Otto Kraus, of the University of Hamburg, and the paleontologist Carsten Brauckmann, of the Technical University of Clausthal, commented on this mystery: “Despite the fact that many well-preserved fossils are known and described, not even a trace of spiracles (stigmata) and tracheae has ever been found…. The maximum length of the largest lepidopteran larvae is approximately 15 cm. However, Arthropleura specimens exceeded this dimension up to more than ten times. Provided that large arthropleurids had really maintained tracheae, they should have been extremely stable and strong tubes. They could hardly be overlooked” (Kraus and Brauckmann 2003, 46–47).

One possibility is that the giant arthropleurid millipedes accomplished gas exchange with the atmosphere directly across the surface area of their bodies, and indeed Kraus and Brauckmann note: “In contrast to other very large terrestrial arthropods … arthropleurids were apparently not equipped with a heavily sclerotized or even mineralized exoskeleton” (Kraus and Brauckmann 2003, 44–45; original emphasis). As anyone who has stepped on a large beetle has experienced, an audible crunch is produced as the beetle’s exoskeleton is crushed. The crunch sound is produced because the beetle has a very rigid, stiff exoskeleton whose cuticular tissues contain a great deal of chitin (its tissues are “heavily sclerotized”). Gas exchange across the rigid body surface area of a beetle is minimal; it accomplishes gas exchange through its tracheae instead. The exoskeleton of the giant Carboniferous millipedes was much softer, more limber and flexible, hence more permeable to gas exchange with the atmosphere. However, even given this very unusual exoskeleton in the arthropleurid millipedes, Kraus and Brauckmann argue that “gas exchange simply via the body surface can certainly be excluded” (2003, 46). Instead, they argue that the giant millipedes must have been semiaquatic, living mostly in water, and may have breathed through a series of plates (“K plates”) along the bottom surface of their body, plates that perhaps may have functioned somewhat like the gills in other aquatic arthropods.

Preserved fossil trackways made by giant arthropleurid millipedes on land are well known and have even been given their own ichnotaxon designation, or trace-fossil name—Diplichnites. Thus clearly the giant Carboniferous millipedes spent a lot of time on land. Instead of being semiaquatic and spending most of their time in water, what if the giant millipedes spent most of their time on land (like normal millipedes) and did indeed successfully breathe directly across their body surface areas because there was more oxygen in the atmosphere than in our modern world? The slowly crawling giant millipedes would not have required as much oxygen as the highly energetic flying griffenflies, and gas exchange across their body surface area may have been so efficient in a world with a hyperoxic atmosphere that they did not even require tracheae in order to breathe—hence these structures became vestigial and were later lost in the evolutionary lineage of the arthropleurid millipedes.

It is difficult to see how such large insects could have existed without having an atmosphere that contained much more oxygen than is present in the modern atmosphere of the Earth. And indeed, it is exactly in this period of time—the Late Carboniferous through the Middle Permian—that the empirical models of the ancient atmosphere of the Earth, which we considered in detail in chapter 3, predict that oxygen concentration levels in the atmosphere began to exceed 30 percent and eventually reached a high of around 35 percent (fig. 3.8). Imagine living in a world that has two-thirds more oxygen in the atmosphere than in the air that we currently are breathing.

The problem is, those same empirical models give differing results on exactly when oxygen began to exceed 30 percent in the atmosphere and when the maximum oxygen content of the atmosphere was reached (fig. 3.8). Table 4.4 shows the known fossil occurrences of some of the giant arthropod groups alongside the oxygen-content levels in the atmosphere predicted by the Rock-Abundance model and the Geocarbsulf model. Note that the known stratigraphic distribution of giant arthropod fossils matches the oxygen predictions of the Rock-Abundance model much better than those of the Geocarbsulf model: giant scorpions appear in the Visean Age, and the Rock-Abundance model predicts that the Earth’s atmosphere contained 25.8 percent oxygen in the Visean—4.8 percentage points more oxygen than is present in the atmosphere of the Earth today. Giant flying griffenflies appear in the fossil record in the Bashkirian Age, when the Rock-Abundance model predicts that the oxygen content of the atmosphere had risen to 32 percent, 11 percentage points more oxygen than our present-day atmosphere of 21 percent. Giant millipedes appear in the fossil record in the Moscovian Age, when the Rock-Abundance model predicts that the oxygen content of the atmosphere of the Earth had risen even further, to 32.8 percent.

TABLE 4.4 Known fossil occurrences of giant terrestrial arthropods in the Carboniferous and Permian compared with the oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere.

| Geologic Age |

Atmospheric O2 |

Giant Arthropod Fossil Occurrences |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

|

| Permian |

| Changhsingian |

24.1% |

23.6% |

|

| Wuchiapingian |

26.5% |

29.0% |

|

| Capitanian |

28.3% |

30.0% |

|

| Wordian |

30.0% |

31.0% |

← Griffenflies |

| Roadian |

30.6% |

30.9% |

← Griffenflies |

| Kungarian |

33.0% |

30.5% |

← Griffenflies |

| Artinskian |

35.0% |

30.0% |

← Griffenflies |

| Sakmarian |

34.8% |

29.3% |

← Griffenflies |

| Asselian |

34.5% |

28.5% |

← Griffenflies, millipedes |

| Carboniferous |

| Gzhelian |

34.2% |

27.9% |

← Griffenflies, millipedes |

| Kasimovian |

33.5% |

26.5% |

← Griffenflies, millipedes |

| Moscovian |

32.8% |

25.8% |

← Griffenflies, millipedes, spiders, silverfish |

| Bashkirian |

32.0% |

25.0% |

← Griffenflies |

| Serpukhovian |

30.0% |

23.0% |

|

| Visean |

25.8% |

18.8% |

← Scorpions |

| Tournaisian |

23.0% |

17.0% |

|

Source: Column (1) is the Rock-Abundance model (Berner et al. 2003); column (2) is the Geocarbsulf model (Berner 2006). Oxygen data are extrapolated from figure 3.8 using the timescale of Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Atmospheric oxygen contents of 25% or higher are underlined; those of 30% or higher are in bold.

In contrast, the Geocarbsulf model (table 4.4) predicts that the atmosphere of the Earth contained only 18.8 percent oxygen in the Visean Age, 1.2 percentage points lower than that of the present Earth’s atmosphere! How could a scorpion 700 millimeters (28 inches) long have breathed in an atmosphere that contained less oxygen than our world today, with its much smaller scorpions? The Geocarbsulf model predicts that atmospheric oxygen had risen to only 25 percent in the Bashkirian—just 4 percentage points higher than our present world—yet at this same time giant, energetically flying griffenflies appear in the fossil record. How could a dragonfly-like insect with a wingspan of 720 millimeters (28 inches) have breathed in an atmosphere containing only 4 percentage points more oxygen than in our world, where our large dragonflies have a wingspan of only 150 millimeters (six inches). This mismatch between the Geocarbsulf data and the fossil record data of giant arthropods (table 4.4) in the Carboniferous supports Scott and Glasspool’s argument that we previously considered in chapter 3: “Collectively, these data suggest levels of O2 modeled for this interval rising from 17 percent to 23.5 percent [in the Geocarbsulf model] are inappropriate and instead favor prior, higher levels modeled at ≈23–31.5 percent [in the Rock-Abundance model], values further supported by the occurrence of very large arthropods at this time” (Scott and Glasspool 2006, 10863). Indeed, the Geocarbsulf model predicts that atmospheric oxygen on the Earth did not reach the 30 percent level until the Artinskian Age of the Early Permian (table 4.4), some 33 million years after the appearance of the first griffenflies!

We can also contrast the differing predictions of the Rock-Abundance and Geocarbsulf models by reversing our argument: if the appearance of giant arthropods in the fossil record is linked to high oxygen levels in the atmosphere, then the disappearance of giant arthropods in the fossil record may be linked to lower oxygen levels. The giant griffenflies declined in abundance during the Capitanian in the Middle Permian, were rare in the Late Permian, and did not survive the end-Permian mass extinction (Nel et al. 2009; Clapham and Kerr 2012). In the Rock-Abundance model, oxygen levels in the atmosphere had dropped to 28.3 percent in the Capitanian—almost as low as the 25.3 percent level predicted for the Visean, a time during which no griffenflies were present on the Earth (table 4.4). Indeed, the griffenflies had already begun to experience difficulties back in the late Early Permian, when one of the two subfamilies of meganeurid griffenflies went extinct; the paleoentomologist André Nel of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and his colleagues note that the “Meganeurinae apparently did not survive after the Early Permian as the Middle to Late Permian griffenflies are all Tupinae” (Nel et al. 2009, 115). In the Rock-Abundance model, oxygen levels in the Early Permian rose from 34.5 percent to a maximum of 35 percent, fell slightly to 33 percent and then dropped still further to 30.6 percent in the Roadian Age at the beginning of the Middle Permian—and the Meganeurinae became extinct.

Although only meganeurid griffenflies of the subfamily Tupinae survived in the Middle Permian, Nel and colleagues note that the “diversity of griffenflies was very high during the Middle Permian, while the more advanced groups of Protozygoptera and Triadophlebiomorpha were also flourishing” (Nel et al. 2009, 115). The Protozygoptera and Triadophlebiomorpha were smaller dragonfly-like insects, and they did not decline in abundance in the Late Paleozoic, nor did they go extinct in the end-Permian mass extinction. Thus, the giant griffenflies went extinct unlike the coexisting “contemporaneous Protozyogpera or Triadophebiomorpha that were still flourishing during the Triassic” (Nel et al. 2009, 115). Yet in the Geocarbsulf model, oxygen levels in the atmosphere persisted as high as 30 percent in the Capitanian at the end of the Middle Permian and as high as 29 percent at the beginning of the Late Permian in the Wuchiapingian (table 4.4), a pattern that does not match the demise of the giant griffenflies during this same interval of time. In contrast, the Rock-Abundance model predicts a much lower oxygen level of 28.3 percent in the Captianian and 26.5 percent in the Wuchiapingian, which is more in accord with the demise of the giant griffenflies.

Vertebrates and Oxygen

In contrast to the Visean Age giant scorpions and Bashkirian Age giant griffenflies (table 4.4), the first of the giant vertebrates began to appear a little later, in the Moscovian Age of the Late Carboniferous (table 4.5). Also in contrast to the giant arthropods, numerous vertebrate giants persisted into the late Middle Permian and Late Permian; examples include the Capitanian five-meter-long (16.4-foot-long) dinocephalian therapsid Moschops capenis (fig. 4.7), the Late Permian three-meter-long (ten-foot-long) pareiasaur parareptile Bunostegos akokanensis, and the two-meter-long (6.6-foot-long) captorhinid reptile Moradisaurus grandis.

TABLE 4.5 Known fossil occurrences of giant terrestrial vertebrates in the Carboniferous and Permian compared with the oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere.

| Geologic Age |

Atmospheric O2 |

Giant Vertebrate Fossil Occurrences |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

|

| Permian |

| Changhsingian |

24.1% |

23.6% |

← Pareiasaurs, captorhinids |

| Wuchiapingian |

26.5% |

29.0% |

← Pareiasaurs, captorhinids |

| Capitanian |

28.3% |

30.0% |

← Dinocephalians, caseids |

| Wordian |

30.0% |

31.0% |

← Dinocephalians, caseids |

| Roadian |

30.6% |

30.9% |

← Dinocephalians, caseids |

| Kungarian |

33.0% |

30.5% |

← Batrachomorphs, edaphosaurs, sphenacodonts |

| Artinskian |

35.0% |

30.0% |

← Batrachomorphs, edaphosaurs, sphenacodonts |

| Sakmarian |

34.8% |

29.3% |

← Batrachomorphs, edaphosaurs, sphenacodonts |

| Asselian |

34.5% |

28.5% |

← Batrachomorphs, edaphosaurs, sphenacodonts |

| Carboniferous |

| Gzhelian |

34.2% |

27.9% |

← Diadectomorphs, ophiacodonts, edaphosaurs |

| Kasimovian |

33.5% |

26.5% |

← Diadectomorphs, ophiacodonts |

| Moscovian |

32.8% |

25.8% |

← Diadectomorphs, ophiacodonts |

| Bashkirian |

32.0% |

25.0% |

|

| Serpukhovian |

30.0% |

23.0% |

|

| Visean |

25.8% |

18.8% |

|

| Tournaisian |

23.0% |

17.0% |

|

Source: Column (1) is the Rock-Abundance model (Berner et al. 2003); column (2) is the Geocarbsulf model (Berner 2006). Oxygen data are extrapolated from figure 3.8 using the timescale of Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Atmospheric oxygen contents of 25% or higher are underlined; those of 30% or higher are also in bold.

The effect of a hyperoxic atmosphere on vertebrates is more subtle than for arthropods with their tracheal breathing system (Graham et al. 1995, 1997). Increased body size is clearly one possible effect, and, not only in the Carboniferous, increased levels of oxygen in the atmosphere in the early Cenozoic have been linked to the evolution of very large mammalian vertebrates during this same interval of time (Falkowski et al. 2005). It is surely no coincidence that very large vertebrates coexisted with very large arthropods in the Carboniferous and Permian landscapes (tables 4.4 and 4.5).

Michael McKinney, a paleontologist at the University of Tennessee, has conducted an extensive analysis of body-mass increases in the ophiacodont, edaphosaur, and sphenacodont (fig. 4.6) synapsid clades (table 4.2) during the Early Permian time span (McKinney 1990). During the Asselian and early Sakmarian Ages, the largest sphenacodont in his sample had a body mass of about 35 kilograms (77 pounds), the largest ophiacodont had a body mass of about 25 kilograms (55 pounds), and the largest edaphosaur had a body mass of about 15 kilograms (33 pounds). By the late Sakmarian Age, the body mass of the largest edaphosaur in his sample had increased to around 90 kilograms (198 pounds), and by the Kungurian Age, at the end of the Early Permian, the body mass of the largest edaphosaur was 330 kilograms (728 pounds). The body mass of the largest ophiacodont increased to 120 kilograms (265 pounds) by the Artinskian Age, and still further to 230 kilograms (507 pounds) by the Kungurian. Finally, the body mass of the largest sphenacodont increased to 120 kilograms (265 pounds) by the Artinskian and to 250 kilograms (551 pounds) by the Kungurian (McKinney 1990).

Thus during the 26-million-year span of the Early Permian, the body masses of edaphosaurs increased by a factor of 22, of ophiacodonts by a factor of 9.2, and of sphenacodonts by a factor of 7.1. These are incredible size increases—an edaphosaur at the end of the Early Permian was fully 22 times larger than one at the beginning of the Early Permian! And, in the Rock-Abundance model (table 4.5), oxygen levels in the Earth’s atmosphere were well above 30 percent for this entire span of time. Note again the mismatch between the Geocarbsulf model predictions and the actual distribution of giant vertebrates in time: in the Geocarbsulf model, oxygen did not even reach the 30 percent level in the atmosphere until the middle of the Early Permian, in the Artinskin Age (table 4.5), long after the dramatic size increases in the synapsid vertebrates were well under way.

Giant batrachomorph amphibians, such as the two-meter-long (6.6-foot-long) Eryops megacephalus (fig. 4.4) also existed during the Early Permian. It is possible that these giant salamander-like amphibians augmented their lung breathing by also breathing directly across their skin surface area, much as the present-day lungless plethodontid salamanders do. The plethodontids are small, only 100 to 200 millimeters (four to eight inches) long, but in our present-day 21 percent oxygen atmosphere they have totally lost their lungs and live solely by gas exchange across the surface area of their naked skin. In an atmosphere containing over 34 percent oxygen (Rock-Abundance model, table 4.5), such an augmentative breathing mechanism may have enabled the Early Permian amphibians to attain their giant size despite their very large body volume relative to skin surface area.

Marine Invertebrates and Oxygen

In contrast to the temporal pattern of gigantism seen on land in the vertebrates (table 4.5), the temporal distribution of giant marine invertebrates (table 4.6) matches more closely the pattern seen in the terrestrial invertebrates, the arthropods (table 4.4). Giant invertebrates first appear in the oceans in the Visean Age of the Early Carboniferous, as do the giant scorpions on land (fig. 4.1), and giant marine invertebrates are generally not present in the Late Permian, just as giant arthropods are not. The terrestrial arthropods are all protostomous animals, however, whereas in the oceans gigantism occurred in the clades of both the protostomes (brachiopods, fig. 4.9; bryozoans) and the deuterostomes (echinoids, crinoids), in animals that are not bilaterians (corals), and even in organisms that are not animals—the single-celled foraminifera (fusulinids, fig. 4.10).

TABLE 4.6 Known fossil occurrences of giant marine invertebrates in the Carboniferous and Permian compared with the oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere.

| Geologic Age |

Atmospheric O2 |

Giant Invertebrate Fossil Occurrences |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

|

| Permian |

| Changhsingian |

24.1% |

23.6% |

|

| Wuchiapingian |

26.5% |

29.0% |

|

| Capitanian |

28.3% |

30.0% |

← Fusulinids, alatoconchid bivalves |

| Wordian |

30.0% |

31.0% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids |

| Roadian |

30.6% |

30.9% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Kungarian |

33.0% |

30.5% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Artinskian |

35.0% |

30.0% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans, crinoids |

| Sakmarian |

34.8% |

29.3% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Asselian |

34.5% |

28.5% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Carboniferous |

| Gzhelian |

34.2% |

27.9% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Kasimovian |

33.5% |

26.5% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, bryozoans |

| Moscovian |

32.8% |

25.8% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids |

| Bashkirian |

32.0% |

25.0% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids |

| Serpukhovian |

30.0% |

23.0% |

← Brachiopods, fusulinids, corals |

| Visean |

25.8% |

18.8% |

← Brachiopods, echinoids, corals |

| Tournaisian |

23.0% |

17.0% |

|

Source: Column (1) is the Rock-Abundance model (Berner et al. 2003); column (2) is the Geocarbsulf model (Berner 2006). Oxygen data are extrapolated from figure 3.8 using the timescale of Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Atmospheric oxygen contents of 25% or higher are underlined; those of 30% or higher are also in bold.

Most marine invertebrates depend upon diffusion-mediated respiration; thus, seawater containing high concentrations of oxygen should facilitate the same size-increase effects in marine organisms as in terrestrial ones (Graham et al. 1995). Seas that existed under a hyperoxic atmosphere would have become oxygen rich via diffusion and might also have experienced little in the way of seasonal periods of anoxia that occur in many oceanic regions today. However, it can be demonstrated that at least some of the size increases seen in marine organisms that occurred in the Carboniferous and Permian were also the result of increased nutrient availability made possible by the evolution of photosynthetic symbioses, a topic that will be explored further in the next section of the chapter.

ECOSYSTEM EVOLUTION AND ANIMAL GIGANTISM

Not all of the animal gigantism that appeared in the Carboniferous and Permian may be directly attributable to the hyperoxic atmosphere that existed on the Earth during that period of time. Other factors that have been proposed to explain this animal gigantism include the evolution of interspecies symbioses, of predator-prey interactions, and of competitive-exclusion interactions.

Many modern species of corals harbor photosynthetic algal species, collectively called zooxanthellae,7 in their tissues in a complex interspecies symbiosis. In the symbiosis, the corals metabolize the hydrocarbons, or food, synthesized by the algae and the oxygen produced by the algae as a waste product in photosynthesis. In turn, in their metabolism the corals produce phosphate and nitrate wastes and carbon dioxide that they recycle back to the algae, which use them to synthesize more hydrocarbons via photosynthesis. In addition, the corals provide the algae with protection from predation by grazing species of organisms by holding them within their tissues.

Corals are sessile predators and generally survive by eating the prey they capture. However, symbiotic coral species can use the additional energy they receive from their symbionts to produce skeletal calcium carbonate at accelerated rates and hence to grow the giant reef tracts found in shallow water regions of the modern world, such as the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. In addition, some modern species of bivalve molluscs are also able to grow to gigantic sizes by utilizing the extra energy provided by photosynthetic symbionts living within their tissues. Individuals of the giant clam Tridacna gigas can have shells 1300 millimeters (4.3 feet) long, compared to an average large clam with a shell about the size of your hand.

Given the occurrence of gigantism in some living coral cnidarians and bivalve molluscs that are symbiotic, it is reasonable to propose that the Carboniferous and Permian giant marine invertebrates may have been able to achieve their large sizes because they possessed symbionts, particularly the rugose corals (tables 4.3, 4.6). It is known that the giant fusulinid foraminifera (tables 4.3, 4.6) that existed in the Carboniferous and Permian contained symbiotic photosynthetic algae in their tissues: many of these giant species evolved specialized skeletal morphologies to contain and protect their symbionts.8 Similar to the shells of the living giant lophotrochozoan mollusc (table 4.3) Tridacna gigas, the giant shells of the Permian bivalves of the family Alatoconchidae (Aljinovic et al. 2008) and the Carboniferous lophotrochozoan brachiopod Gigantoproductus giganteus (table 4.3, fig. 4.9) may indicate that algal symbioses were widespread in the clade of the ancient lophotrochozoan animals.

However, no photosymbiotic species are known to have evolved in the deuterostome echinoderm lineages of the crinoids and echinoids (table 4.3), the protostome lophotrochozoan lineage of the colonial bryozoans (table 4.3), or the lophotrochozoan molluscan lineage of the ammonoid predators (table 4.3), yet these invertebrate groups also evolved gigantism in the Carboniferous (table 4.6). Thus, while some of the gigantism exhibited by the Late Paleozoic marine invertebrates may be linked to the evolution of interspecies symbioses, it is highly unlikely that mobile predators like ammonites would ever have evolved photosymbiosis. In addition, no terrestrial arthropod or vertebrate species has evolved photosymbiosis, so gigantism in land animals cannot be attributed to that mechanism.

On land, defense against predation is often invoked as a selective mechanism that would favor the evolution of large body size. A modern example is the combination of large body size and herd behavior in African elephants, both of which are powerful deterrents to lion predators. An adult elephant is simply too big, relative to the size of a lion, and there are too many elephants together in the herd—lions know that attacking them could lead to serious injury or death to the lion, not the elephants. Thus lions concentrate on attacking small, juvenile elephants, if they can be separated from the herd, or on attacking older, less agile and formidable adults. The same ecological strategy apparently evolved in ancient Mesozoic ecosystems with the evolution of giant body sizes in the sauropod dinosaurs and the evolution of herd behavior as well—traits that likely would have been deterrents to theropod dinosaur predators.9

Thus it could be argued that the evolution of giant body sizes in the sap-sucking palaeodictyopteran winged insects in the Carboniferous was a defensive response to the evolution of the giant meganisopteran griffenfly predators (table 4.1). How, then, can we ecologically explain the evolution of gigantism in the griffenflies? The griffenflies had no flying predators to defend themselves against—the first aerial, gliding vertebrate predators evolved in the Late Permian after the demise of the giant griffenflies (Nel et al. 2009). In addition, modern-day aerial bird and bat predators preferentially select large flying insects, not small ones, as prey (Clapham and Kerr 2012). If the giant griffenflies were ecological predatory equivalents of birds and bats, then it could be argued that predation was a selective mechanism favoring the evolution of small body size, not large, in the palaeodictyopteran prey species.

It has also been suggested that the absence of competition in a stable, open niche was a selective mechanism favoring the evolution of gigantism. In this scenario, the evolution of large body sizes is seen as the consequence of animals’ evolving in optimal environmental conditions with little or no competition or predation (Briggs 1985; Harrison et al. 2010; Dorrington 2015). That is, the evolution of gigantism in stable, open niches could be argued to be the result of a form of ecological release, in contrast to the circumstances of species evolving in habitats with numerous competitors and/or predators (Blackburn and Gaston 1994). Clearly competition for limited resources such as food, could be a selective mechanism that would limit size. And, as discussed above, preferential predation on large prey species could be a size-limiting selective mechanism as well. Thus it could be argued that the giant griffenflies evolved as an ecological consequence of the absence of competitors and predators in the Carboniferous skies—the reverse of the defense-against-predation argument for the evolution of gigantism. How, then, can we ecologically explain the evolution of gigantism in the palaeodictyopteran sap-suckers, species that did not evolve in an environment free of predators?

In summary, the evolution of photosymbioses in marine invertebrate organisms clearly provides an alternative to a hyperoxic atmosphere as a physiological pathway to gigantism, although the two phenomena could also operate in concert. It is more difficult to argue that the simultaneous evolution of gigantism in numerous species of both terrestrial arthropods and vertebrates in the Carboniferous (tables 4.4 and 4.5) was the result of predator-prey and/or competitive-exclusion ecological interactions within the separate evolutionary lineages of these two very different groups of organisms. It is easier to argue that a common pervasive factor—the presence of a hyperoxic atmosphere in the Carboniferous—was the trigger for the evolution of gigantism in terrestrial arthropods and vertebrates. Further support for this argument comes from the fact that in another period of geologic time in which the Earth had a very oxygen-rich atmosphere—the early Cenozoic—gigantism evolved in mammalian vertebrates (Falkowski et al. 2005).

In this section of the chapter, we have considered physiological and ecological hypotheses for the evolution of animal gigantism as alternatives to the hypothesis that gigantism was triggered by hyperoxia. In the next section, that argumentation will be reversed: we will consider arguments that changes in the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere actually were the trigger for major physiological and ecological events in animal evolution.

LATE PALEOZOIC OXYGEN AND ANIMAL EVOLUTIONARY EVENTS

The hyperoxic atmosphere of the Earth during the Carboniferous and Permian may have been the trigger for far more evolutionary events than just the appearance of animal gigantism. Jeffrey Graham, at the University of California in San Diego, and his colleagues have proposed that “global atmospheric hyperoxia possibly aided the vertebrate invasion of land”; that “the Carboniferous diversification of both the insects and the vertebrates correlates with the rise of atmospheric oxygen”; that “hyperoxic air may have also been critically important in the evolution of the cleidoic egg” in the first amniotes; and that the Permian “diversification of synapsids seems to be partially attributable to the effects of hyperoxia and a denser atmosphere on activity enhancing specializations such as metabolic heat retention,” hence leading to the evolution of endothermy (Graham et al. 1995, 119–120).

A comparison of some of the major events in the evolution of vertebrates in the Carboniferous and Permian and the modeled oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere during this span of time is given in table 4.7. The invasion of land by vertebrates began in the Devonian with the evolution of the first tetrapods from the sarcopterygian fishes, but these early invaders were “aquatic tetrapods,” spending most of their time in the rivers and lakes of the terrestrial realm. Only in the Visean Age of the Early Carboniferous, following the Tournaisian Gap (table 1.7), did the invasion of dry land by the vertebrates begin in earnest (McGhee 2013). It is therefore of interest that the Rock-Abundance model predicts a rise in oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere to 25.8 percent in the Visean, 4.8 percentage points higher than in the present-day atmosphere, and that giant scorpions appeared on land and giant invertebrates appeared in the oceans at this same time (tables 4.4 and 4.6).

TABLE 4.7 Major events in the evolution of terrestrial vertebrates in the Carboniferous, Permian, and Early Triassic compared with the oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere.

| Geologic Age |

Atmospheric O2 |

Vertebrate Evolutionary Events |

| |

(1) |

(2) |

|

| Triassic |

| Olenekian |

22.5% |

20.0% |

← Endothermic therapsids? |

| Induan |

23.3% |

21.8% |

← Endothermic therapsids? |

| Permian |

| Changhsingian |

24.1% |

23.6% |

← End-Permian mass extinction |

| Wuchiapingian |

26.5% |

29.0% |

← Therapsid and reptilian diversifications |

| Capitanian |

28.3% |

30.0% |

← End-Capitanian extinction |

| Wordian |

30.0% |

31.0% |

|

| Roadian |

30.6% |

30.9% |

← Therapsid diversification |

| Kungarian |

33.0% |

30.5% |

← Olson’s extinction |

| Artinskian |

35.0% |

30.0% |

|

| Sakmarian |

34.8% |

29.3% |

|

| Asselian |

34.5% |

28.5% |

|

| Carboniferous |

| Gzhelian |

34.2% |

27.9% |

|

| Kasimovian |

33.5% |

26.5% |

← Tetrapod diversification, ecological innovation |

| Moscovian |

32.8% |

25.8% |

|

| Bashkirian |

32.0% |

25.0% |

← Synapsid and reptilian amniotes present |

| Serpukhovian |

30.0% |

23.0% |

← Origin of amniotes? |

| Visean |

25.8% |

18.8% |

← Invasion of land; origin of amniotes? |

| Tournaisian |

23.0% |

17.0% |

|

Source: Column (1) is the Rock-Abundance model (Berner et al. 2003); column (2) is the Geocarbsulf model (Berner 2006). Oxygen data are extrapolated from figure 3.8 using the timescale of Gradstein et al. (2012).

Note: Atmospheric oxygen contents of 25% or higher are underlined; those of 30% or higher are also in bold.

Graham and colleagues argue that the elevated oxygen content in the Earth’s atmosphere during the Visean helped the vertebrates to successfully invade dry land in three ways. First, the hyperoxic atmosphere helped elevate primitive lung effectiveness in oxygen uptake. Second, it helped the early vertebrates to lower their rate of desiccation in breathing dry air by allowing them to take fewer breaths yet still obtain sufficient oxygen. Third, the hyperoxic atmosphere helped boost the metabolic rates of the vertebrates, thus assisting them in overcoming the force of gravity in walking on dry land. Dehydration is a problem that land-dwelling animals still face today, as are the metabolic demands of locomotion while enduring the constant pull of gravity—they point out that, as water is 1,000 times more dense than air, an early tetrapod that was essentially weightless in water would be 1,000 times heavier on dry land (Graham et al. 1997). But note that this invasion-assistance hypothesis works only for the atmospheric-oxygen predictions (table 4.7) of the Rock-Abundance model for the Visean—the Geocarbsulf model predicts a Visean atmosphere containing less oxygen than that of the present-day Earth!

We know from the fossil record that the amniote vertebrates had evolved by the Bashkirian Age at the beginning of the Late Carboniferous and that both clades of the amniotes were present—the reptilian amniote clade is represented by body fossils of the species Hylonomus lyelli and the synapsid amniote clade by body fossils of the species Protoclepsydrops haplous, both found in the famous Joggins strata with their preserved fossil tree stumps and vertebrate skeletons in Nova Scotia, Canada (Benton 2015). However, as discussed in chapter 2, trace fossil evidence suggests that more derived species of synapsid amniotes than Protoclepsydrops haplous were also present in the Bashkirian, not just the basal one known from body fossils. This evidence comes from the trackway ichnospecies Dimetropus, found in Bashkirian-aged strata in Germany (Voigt and Ganzelewski 2010). This trackway was made by quite a large animal—its hind feet were around 140 millimeters (5.5 inches) long, and its forefeet around 70 millimeters (2.8 inches) long. The trackway is most similar to those produced by more-derived ophiacodontid, edaphosaurid, or sphenacodontid synapsids, all of which were large animals. In contrast to the large Dimetropus footprints, both the known basal synapsid and reptilian amniotes were quite small—the animals were only 200 millimeters (eight inches) or so in length. If the ichnospecies Dimetropus was produced by a highly derived synapsid amniote in the Bashkirian, then the split between the synapsid and saurposid amniotes had to have occurred even earlier than the Bashkirian—sometime in the Early, not the Late, Carboniferous.

As discussed in chapter 2, an intriguing partial body fossil suggests that the amniotes may have evolved in the Visean Age, a possibility that we will explore in more detail here. This fossil is of the enigmatic species Casineria kiddi, found in a sedimentary nodule that contains most of the body skeleton—but unfortunately the head and tail are missing. The animal was tiny: its back, from the base of its neck to its pelvic girdle, was only 80 millimeters (three inches) long, making it the smallest known Early Carboniferous tetrapod (Carroll 2009).

The vertebrae of Casineria kiddi are solidly ossified, and the animal had long, slender, curved ribs. The well-preserved forelimb and forefoot of the animal held the greatest surprise, as described by the Cambridge University paleontologist Jennifer Clack: “The humerus is much more slender than that of any other Early Carboniferous tetrapod, with an obvious shaft and with the two ends set at different angles to each other (known as torsion). The radius and ulna are also slender, with an olecranon process on the ulna…. These features alone strongly suggest a fully terrestrial animal.” In the forefoot, “the manus has five slender digits…. The last phalanx on each digit (the ungual) is noticeably curved, and the whole arrangement suggests a hand capable of grasping. No other Early Carboniferous tetrapod shows digits like this, but they are similar to those found in Late Carboniferous early amniotes” (Clack 2002, 199). The McGill University paleontologist Robert Carroll also observes: “Uniquely, Casineria had curved terminal phalanges (unguals) forming claws, as in many early amniotes” (Carroll 2009, 74). In summary, Clack notes: “It has been suggested that the origin of amniotes is connected with an evolutionary step involving small size … and here is a specimen that accords well with that theory” (Clack 2012, 277). Because the head of the animal is missing, it is impossible to prove that Casineria kiddi was indeed the first known amniote; clearly, however, it is the most derived species of tetrapod yet known from the Visean Age.

Graham and colleagues argue that a hyperoxic atmosphere—whether in the Visean, Serpukhovian, or Bashkirian—also assisted in the evolution of the first amniote vertebrates. A key step in the evolution of the amniotes was the evolution of the amniote egg: “With specialized membranes to prevent water loss (amnion), enhance respiratory gas exchange (chorion), and collect waste products (allantois), the amniotic egg (also termed the cleidoic egg), which appeared in the Carboniferous, eliminated amphibian reliance upon aquatic egg laying and larval development…. Accordingly, natural selection leading to the development of the three amniote egg membranes enabled a further increase in egg size. Moreover, the hyperoxic Carboniferous atmosphere would have allowed the development of large amniote eggs by minimizing the ratio of water loss to oxygen uptake” (Graham et al. 1997, 153). Note again that this amniote-evolution-assistance hypothesis works only for the atmospheric-oxygen predictions of the Rock-Abundance model for the Visean Age (25.8 percent oxygen) and not the Geocarbsulf model (table 4.7), which predicts a Visean atmosphere containing less oxygen (18.8 percent) than in our present world (21 percent).

Following the evolution of amniotes (whether in the Visean or Serpukhovian), a major diversification of amniotes occurred in the Moscovian-Kasimovian interval of time. The first fossils of the advanced ophiacodontid synapsids are found in Moscovian strata, and fossils of the first advanced varanopid, edaphosaurid, and sphenacodontid (fig. 4.6) synapsids are found in Kasimovian strata. In the reptilian amniote clade, the first fossils of the advanced diapsid, Petrolacosaurus kansensis, is found in Kasimovian strata (McGhee 2013). Of particular note is the evolution of herbivory in both the batrachomorph amphibian and the synapsid amniote clades in the Late Carboniferous. The evolution of the ability to efficiently use living plants as a food source was a key element in the construction of the terrestrial ecosystem familiar to us today, with its energy flow from living plants to herbivores to carnivores. Within the batrachomorph clade the first fully herbivorous vertebrates, the diadectomorphs, are represented by the Moscovian species Limnostygis relictus, and the herbivorous edaphosaurid synapsid species Ianthasaurus hardestii and Xyrospondylus ecordi appeared in the following Kasimovian Age (McGhee 2013).

Graham and colleagues further argue that “the Carboniferous diversification of both the insects and vertebrates correlates with the rise in atmospheric oxygen” (Graham et al. 1995, 119, fig. 2). However, establishing a causal link between increased speciation and evolutionary innovation and the presence of a hyperoxic atmosphere is not as straightforward as it is for the evolution of large body sizes or the evolutionary transition from aquatic habitats to terrestrial habitats. Why should higher oxygen levels trigger evolutionary innovation, such as the evolution of herbivory, or increased speciation rate? Graham and colleagues simply speculate that “increased oxygen availability may have also fuelled the diversification and ecological radiation of late Palaeozoic groups by acting as a substrate for the evolution of behavioural, physiological and ecological adaptations, permitting greater exploitation of aquatic habitats and the newly evolving terrestrial biosphere” (Graham et al. 1995, 120). It is known that both clades of the amniotes were present in the Bashkirian (table 4.7), when oxygen levels reached 32 percent in the atmosphere (in the Rock-Abundance model). Was the increase in oxygen in the atmosphere to 33.5 percent in the Kasimovian really the trigger for amniote diversification and ecological innovation?

In contrast, the University of Bristol paleontologist Sarda Sahney and colleagues argue that the Carboniferous diversification of tetrapods was triggered by the ecological effects of the Kasimovian crisis in the great rainforests that we considered in chapter 3. They argue that the Kasimovian crisis resulted in the fragmentation of the tropical rainforests into numerous small habitat islands, and demonstrate that a major increase in the number of endemic species of tetrapods occurred from the Moscovian to the Kasimovian. Not only did the evolution of numerous isolated pockets of endemic species occur, but that “rainforest collapse was also accompanied by acquisition of new feeding strategies (predators, herbivores), consistent with tetrapod adaptation to the effects of habitat fragmentation and resource restriction” (Sahney et al. 2010, 1079), and “our data, which show elevated extinction rates, increased endemism, and ecological diversification, apparently represent a classic community-response to habitat fragmentation” (Sahney et al. 2010, 1081). They also point out that the batrachomorph amphibians experienced high extinction rates—losing nine families—and major ecological turnover from the Moscovian to the Kasimovian, whereas the amniotes lost no families to extinction, probably because they had an “ecologic advantage in the widespread drylands that developed” in the Kasimovian (Sahney et al. 2010, 1081).

Another animal evolutionary event during the Carboniferous and Permian that may have had no relationship to the presence of a hyperoxic atmosphere on Earth is Olson’s extinction10 in synapsid amniotes, which occurred in the Early to Middle Permian transition (table 4.7). In this vertebrate extinction event, the long-lived and dominant “pelycosaurs” (table 4.2), the non-therapsid synapsids, were eliminated. Of the existing six families of pelycosaurs present before the extinction, three went extinct in the late Artinskian, a fourth perished in the early Kungurian, and the final two families succumbed in the Captanian (Kemp 2006). The exact cause of the demise of the previously highly successful clades of non-therapsid synapsids remains unknown. Oxygen levels in the atmosphere are predicted to have fallen by 2 percent from the Artinskian to the Kungurian in the Rock-Abundance model (table 4.7)—but could that have triggered the extinction of six entire families of pelycosaurs? Olson’s extinction will be considered in more detail in chapters 5 and 6, where the possibility that this vertebrate extinction event was triggered by paleoclimatic changes at the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age will be explored.

Following a gap in the fossil record, named Olson’s Gap (Lucas and Heckert 2001; Lucas 2004), a major diversification in therapsid synapsids occurred in the Roadian (table 4.7). The basal therapsid group, the Biarmosuchia, had evolved by the Early Permian and is represented by the species Tetraceratops insignis. However, it was only in the Middle Permian that the dinocephalian therapsids evolved—a diverse group both in terms of numbers, over 40 genera, and in terms of ecology, as both carnivorous and herbivorous dinocephalians existed (Benton 2015). The dinocephalians also included some of the largest land animals to exist in the Permian, such as the five-meter-long (16.4-foot-long) dinocephalian herbivore Moschops capenis (fig. 4.7). The dinocephalians appear in the fossil record after the demise of the “pelycosaurs” (table 4.2), the non-therapsid synapsids; thus their replacement of these earlier synapsid herbivores and carnivores in the Permian appears to be a case of passive ecological replacement rather than active, competitive ecological replacement.

The dinocephalians themselves were driven to extinction at the end of the Capitanian (table 4.7) and were replaced by the dicynodont and gorgonopsian therapsids (table 4.2). The end-Capitanian extinction will be considered in more detail in chapters 5 and 6, but like Olson’s extinction, it appears not to have had any relationship to the oxygen content of the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen levels fell only 1.7 percent from the Wordian to the Capitanian (in the Rock-Abundance model, table 4.7), even less than the 2 percent drop that preceded Olson’s extinction. Instead, the end-Capitanian extinction is thought to have been triggered by the onset of mantle-plume volcanism in China during this interval of time.11

The Late Permian dicynodonts were a diverse group of herbivores, over 60 genera, and the gorgonopsians comprised about 35 genera of carnivores (Benton 2015). The dicynodonts and gorgonopsians were the dominant herbivores and carnivores of the Late Permian, and together they constituted about 80 percent of the terrestrial vertebrate diversity (Erwin 1993). Finally, the therocephalian and cynodont therapsids (table 4.2) also appeared in the Late Permian—the cynodonts are particularly of note because the first mammals would evolve in the cynodont clade in the Late Triassic, represented by the species Adelobasileus cromptoni.