The end of the Permian period is marked by global warming and the biggest known mass extinction on Earth. The crisis is commonly attributed to the formation of the Siberian Traps Large Igneous Province…. Heating of organic-rich shale and petroleum bearing evaporites around sill intrusions led to greenhouse gas and halocarbon generation in sufficient volumes to cause global warming and atmospheric ozone depletion…. The gases were released to the end-Permian atmosphere partly through spectacular pipe structures with kilometre-sized craters.

—Svensen et al. (2009, 490)

THE CAPITANIAN CRISIS

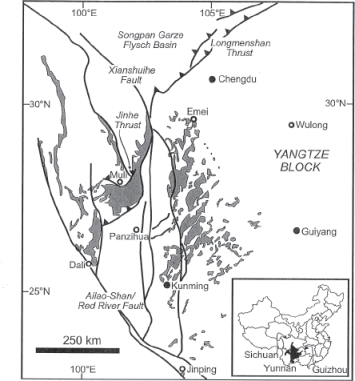

The Capitanian Age witnessed the opening salvo in the volcanic assault that would bring an end to the Paleozoic world. Deep beneath South China, a huge plume of hot magma was slowly rising to the Earth’s surface. South China in the Capitanian was a large island, separate from present-day North China, and was located in the tropics at the Earth’s equator (fig. 6.1). The mantle plume would eventually intersect the bottom of South China, burn its way up through the continental crust, and pour an incredible amount of hot liquid lava across a huge expanse of the Earth’s surface. In the process, it would create what we now call the Emeishan “large igneous province,” or LIP in the vernacular of the volcanologists.1

FIGURE 6.1 Paleogeography of the Late Permian world showing the locations of the Emeishan and Siberian large igneous provinces, both of which erupted during the last nine million years of the Permian.

Source: From Lithos, volume 79, pp. 475-489, by J. R. Ali, G. M. Thompson, M.-F. Zhou, and X. Song, “Emeishan large igneous province, SW China,” copyright © 2005 Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

What is a LIP? A typical LIP is the product of mantle-plume volcanism in which a plume of magma rises from deep in the Earth’s mantle and, when it reaches the Earth’s surface, erupts almost unimaginable volumes of basaltic lava and injects a huge amount of hot gases into the atmosphere. A LIP eruption is thus characterized by (1) its large volume, hundreds of thousands to millions of cubic kilometers of molten magma; (2) its large areal extent, with lava covering hundreds of thousands to millions of square kilometers of land or seafloor; (3) its rapid eruption, consisting of numerous years- to decade-long volcanic pulses spread over only one to five million years—a very short period of time on geologic timescales; and (4) the type of lava usually produced in the eruption—basaltic.2 Basaltic lava is quite liquid and flows for considerable distances before slowly freezing into solid rock, which partially explains why such large areas of land are covered by lava in a “flood basalt” LIP volcanic event.3 The other explanation for the large size of LIPs is the fantastic amount of lava that pours out onto the Earth’s surface through numerous cracks and fissures produced in the Earth’s crust by the huge head of the hot mantle plume located beneath it.

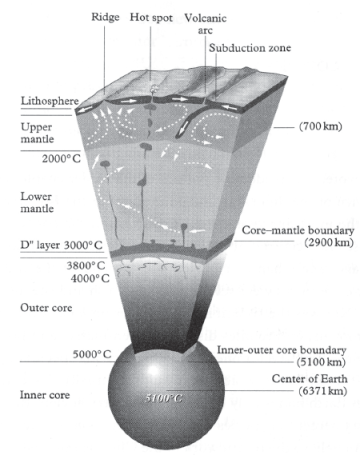

Vincent Courtillot, a geophysicist at the University of Paris, argues that the initial head of a mantle plume could exceed 200 kilometers (124 miles) in diameter when it initially forms at the boundary between the molten outer core of the Earth and the lower mantle, located some 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) below the surface (fig. 6.2). As it slowly rises through the mantle, he argues, the head of the plume may expand to some 500 kilometers (310 miles) in diameter as it melts through mantle rock and then further expand to some 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) in diameter as it impacts and spreads out under the continental crust located above it at the Earth’s surface (Courtillot 1999, 108).

FIGURE 6.2 Cross-section of the interior of the Earth showing a hot-spot LIP region (top center of figure) produced by mantle plumes rising to the Earth’s surface from a depth of 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles).

Source: From Evolutionary Catastrophes, by Vincent Courtillot, copyright © 1999 Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission.

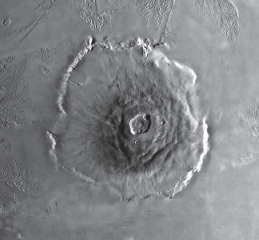

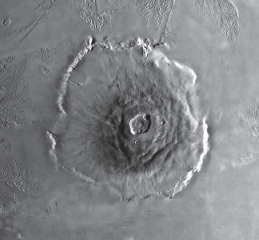

A mantle plume can exist for a significant period of geologic time, producing a relatively stable “hot spot” (fig. 6.2) near the surface of the Earth with the gigantic plates of the Earth’s lithosphere slowly moving across it. The Hawaiian Islands were produced in this fashion, with each volcanic island forming sequentially as the mantle-plume hot spot burned through the lithospheric plate moving across it. By dating the ages of the Hawaiian Islands and associated submerged seamounts, it can be shown that the mantle plume producing the island chain has been stable in its position for at least 74 million years. The hot spot is presently located beneath the largest island, Hawaii, which is the largest volcano on Earth—although this is not apparent because most of the volcano is submerged with only its tip protruding above the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Measuring from its tip down to the seafloor, the volcano is a ten-kilometer-high (6.2-mile-high) mass of basaltic lava produced by mantle-plume volcanism (Courtillot 1999). The largest known volcanoes produced by mantle-plume hot-spot eruptions are not on Earth, however, but on our sister planet, Mars. The largest known volcano in the solar system is the Martian Olympus Mons, which is a towering 21.3-kilometer-high (13.2-mile-high) pile of basaltic lava flows (fig. 6.3). The Martian volcanoes Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons, Arsia Mons, and Elysium Mons are all taller than ten kilometers (hence taller than Earth’s Hawaii volcano) (Croswell 2003), and they were all formed by mantle-plume volcanism. Mars is a smaller planet with a smaller mantle and core, and the movement of the plates of its crust were not as dynamic as those seen on Earth before the core of Mars eventually cooled and the Martian magnetic field collapsed. As a result, most of the volcanoes on Mars were created by mantle plumes, not, as on Earth, by the melting of plate boundaries in subduction zones (for example, the “ring of fire” distribution of volcanoes surrounding the Pacific Ocean is created by subduction of Pacific Ocean plates). Because plate motion ceased early in Martian history, its plates did not move progressively across mantle-plume hot-spot locations. Almost all of the lava that erupted at a hot spot on Mars accumulated into a single volcano—rather than a chain of volcanoes like the Hawaiian Islands—resulting in the even more gigantic size of the Martian LIP volcanoes.

FIGURE 6.3 The Martian volcano Olympus Mons, the largest known volcano in the solar system, a towering 21.3-kilometer-high (13.2-mile-high) pile of basaltic lava flows produced by mantle-plume hot-spot eruptions.

Source: Photograph courtesy of NASA.

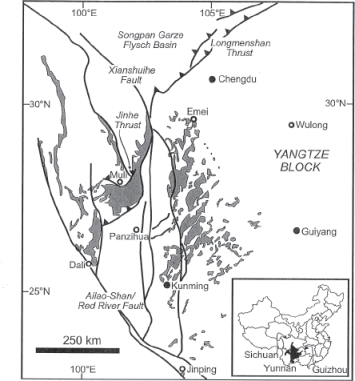

Eleven LIP volcanic eruptions are known to have occurred on Earth in the past 260 million years (Courtillot and Renne 2003; Saunders 2005; Courtillot et al. 2010). No less than two of these massive eruptions occurred during the short time span of the last nine million years of the Permian—producing the Emeishan and the Siberian LIPs (figure 6.1). Our best radiometric data indicate that the Emeishan LIP began to erupt between 257.6 ± 0.5 and 259.6 ± 0.5 million years ago, near the Capitanian/Wuchiapingian boundary (Shellnutt 2013), whereas biostratigraphic data indicate that the lava eruptions may have begun earlier in the mid-Capitanian (Bond, Wignal, et al. 2010). The Emeishan LIP may have continued to erupt sporadically for about 20 million years (Racki and Wignall 2005; Shellnut 2013), up into the Triassic, but the majority of the volcanic material in the LIP was emplaced in less than 1.5 million years, essentially at the Capitanian/Wuchiapingian boundary (Shellnutt 2013). The Emeishan eruption is estimated to have produced 300,000 to 600,000 cubic kilometers (71,700 to 143,400 cubic miles) of lava, and its main lava outcrop covers about 250,000 square kilometers (96,500 square miles) of land today (Ali et al. 2005; Shellnut 2013). It is difficult to estimate the original size of the Emeishan LIP because of extensive erosion of the original lava flows and major tectonic fragmentation of the South China continental block as it collided with and sutured together with the North China and Indochina blocks in the early Mesozoic, plus the Indo-Eurasian block collisions in the early Cenozoic (Shellnutt 2013). In our modern world, outcrops of the original Emeishan LIP volcanics can be scattered as much as 300 kilometers (186 miles) away from one another across southwest China (fig. 6.4) (Wignall et al. 2009). Thus some estimates put the original land area covered by the Emeishan flood basalts at over two million square kilometers (772,000 square miles) (Racki and Wignall 2005).

FIGURE 6.4 Geologic map showing the exposed basalt outcrops (shaded regions) of the Emeishan large igneous province in southwest China (inset map in lower right corner of the figure).

Source: From Lithos, volume 79, pp. 475–489, by J. R. Ali, G. M. Thompson, M.-F. Zhou, and X. Song, “Emeishan Large Igneous Province, SW China,” copyright © 2005 Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

A volume of 300,000 to 600,000 cubic kilometers of molten lava is a staggering amount—nothing like the Emeishan LIP eruption has ever occurred within human history. The largest flood-basalt eruption in recorded history is the Eldgjá eruption in Iceland, which occurred from AD 934 to AD 940 and produced 19.6 cubic kilometers (4.7 cubic miles) of basaltic lava (Thordarson and Self 2003). However, the best-documented LIP eruption in history is the Laki eruption, also in Iceland, which started on June 8, 1783, and continued for eight months until February 7, 1784 (Thordarson et al. 1996; Thordarson and Self 2003). The Laki LIP eruption is the second largest in human history, producing 14.7 cubic kilometers (3.5 cubic miles) of basaltic lava. This lava poured from 140 volcanic vents in fissures that extended in a row some 27 kilometers (17 miles) long, flowing away from the fissures to covered some 580 square kilometers (224 square miles) of land in southeast Iceland (Thordarson and Self 2003; Stone 2004).

The Laki LIP eruption produced a plume of gases that extended some 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) up into the atmosphere. The total eruption ejected approximately 122 million tonnes (134 million tons) of sulfur dioxide (SO2) into the atmosphere, which reacted with water vapor to produce about 200 million tonnes (220 million tons) of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) droplets. About 175 million tonnes (193 million tons) of sulfuric acid precipitated out of the atmosphere as acid rain all across Europe, and the remaining 25 million tonnes (28 million tons) remained in the upper tropopause to lower stratosphere for over a year (Thordarson and Self 2003). The volcanic rifts also emitted huge clouds of chlorine and fluorine gas, which reacted with water vapor to produce about seven million tonnes (7.7 tons) of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 15 million tonnes (16.5 tons) of hydrofluoric acid (HF) in the atmosphere, of which one million tonnes (1.1 million tons) of hydrofluoric acid fell as acid rain on the island of Iceland alone (Thordarson and Self 2003; Stone 2004).

The effect of the Laki LIP eruption on the human population of Iceland was catastrophic: 10,000 people were killed—about 20 percent of the total population of Iceland at the time (Stone 2004). Over 75 percent of the grazing livestock animals were killed (Schmidt et al. 2011). Rain on the island was so acid that it burned holes in the leaves of trees—most of the trees and shrubs died and did not return for some three to ten years. Cultivated grasses—food for livestock—withered. Many people died of starvation in a famine that lasted for three years (Jackson 1982). Others died from sulfur dioxide and sulfuric acid inhalation (Schmidt et al. 2011). But many people and livestock animals died from chronic fluorine poisoning. The hydrofluoric acid rain produced fluoride salts on grasses eaten by farm animals, poisoning the animals. The animals were eaten by humans, and they became poisoned. Even the water was poisoned by fluorine—drinking water contained as much as 30 times the level of fluorine compounds permitted in modern drinking water. Merely drinking a glass of water would make you sick, yet the islanders had no choice—there was no other source of drinking water (Stone 2004).

The effects of the Laki LIP eruption extended much farther away than just Iceland. All across Europe, sunlight dimmed as the sulfuric aerosol cloud spread east from the Icelandic flood basalts. This volcanic air pollution was called the “dry fog” in English-speaking areas, as it looked like fog but was not damp like fog; in German-speaking areas it was described as the Höhenrauch, or smoke in the skies. Acid rain withered summer wheat crops across Europe, and the green leaves on trees in the middle of summer turned yellow and brown and fell to the ground as if it were late autumn. The dry fog persisted for some five to six months, and winter came unusually early.4 The winter of 1783–1784 was the harshest recorded in 250 years, and lemon crops far to the south in Italy were destroyed by frost. In England alone, some 20,000 people died from weather-related illnesses; in France the death rate was 25 percent higher than normal (Stone 2004). If an equivalent eruption were to occur today, computer simulations predict that some 142,000 people would die in Europe from air-pollution effects alone (Schmidt et al. 2011).

In North America, the winter of 1783–1784 was the most severe in recorded history in the New World. In the fledgling United States of America, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the harsh winter was probably caused by a volcanic eruption that he had heard about in Europe. In Europe itself, the French naturalist Mourgue de Montredon attributed the intense cold directly to the Laki eruption in Iceland (Thordarson and Self 2003),5 and Neale (2010) considers the environmental effects of the Laki eruption to have helped spark the French Revolution. The volcanic cloud of sulfuric aerosols produced in the Laki LIP eruption eventually covered the entire Northern Hemisphere from a latitude of about 35°N up to the North Pole. The mean surface temperature of the Earth in this region dropped by about −1.3°C (−2.3°F), and the colder-than-normal period lasted from two to three years in the Northern Hemisphere (Thordarson and Self 2003; Schmidt et al. 2012).

The mantle plume beneath the Icelandic hot spot is predicted to produce a Laki-style flood-basalt eruption every 200 to 500 years (Thordarson and Larsen 2007; Schmidt et al. 2012). It is a historical fact that four such large-volume basaltic eruptions have occurred in the past 1,200 years, including the largest in recorded history (Eldgjá) and the second largest (Laki), giving an average eruption frequency of one per 300 years (Thordarson and Self 2003). For a comparison with the Emeishan LIP eruption in the Middle Permian, take the volume of lava produced in the largest known eruption in history, 19.6 cubic kilometers, and for simplicity in arithmetic round it up to 20 cubic kilometers (4.8 cubic miles). Now take the shortest predicted Icelandic LIP-eruption frequency, one per 200 years, and divide 100,000 years by that. In this worst-case scenario for the Icelandic mantle plume—the largest eruption occurring in the shortest predicted period of time—some 500 eruptions, each producing 20 cubic kilometers of lava, would occur in 100,000 years. Thus the total volume of Icelandic hot-spot volcanism would be 10,000 cubic kilometers (2,400 cubic miles) of lava per 100,000 years, or 150,000 cubic kilometers (36,000 cubic miles) of lava per 1.5 million years.6 In contrast, the Emeishan LIP produced a minimum of 300,000, and perhaps as much as 600,000, cubic kilometers of lava in less than 1.5 million years. Thus the Emeishan mantle-plume lava production was at least twice as large, and perhaps as much as four times as large, as that of the Icelandic hot spot.

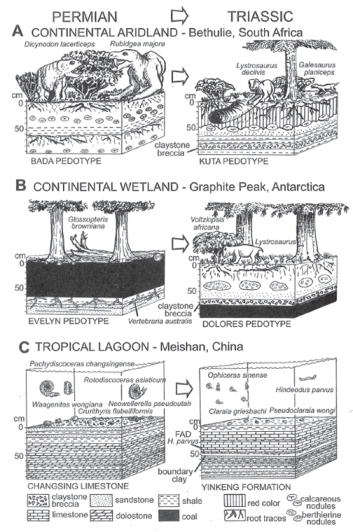

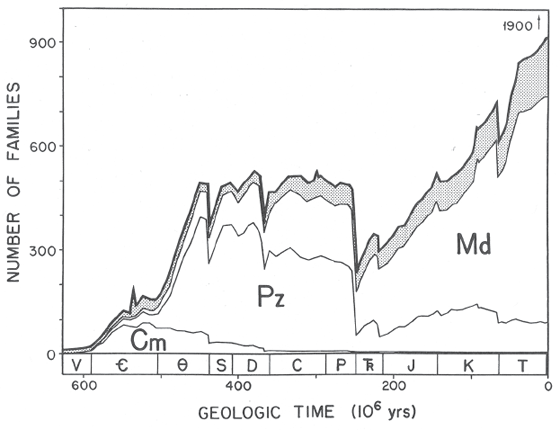

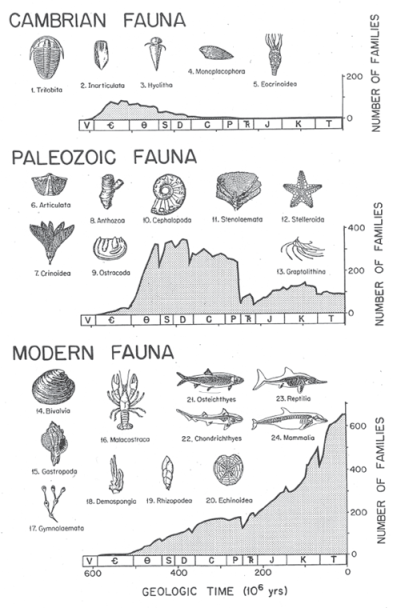

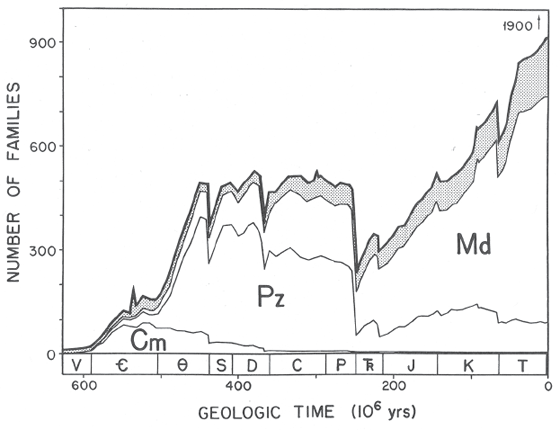

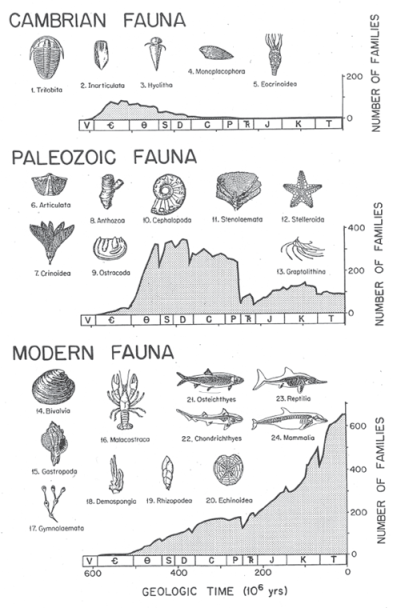

The Emeishan LIP eruption was coincident in time with the Capitanian extinction (Zhou et al. 2002; Wignall et al. 2009; Bond, Wignall, et al. 2010). It is thus logical to explore a causal relationship between the two events—that is, to seek the cause of the biodiversity crisis in the environmental effects of this mantle-plume volcanic eruption. But first let us examine some of the biological effects of the extinction. The loss in marine biodiversity that occurred in the Capitanian event was once thought to be the third largest in Phanerozoic history (Sepkoski 1996; Bambach et al. 2004), but it is now known that many of the extinctions that were once thought to have occurred in the Capitanian in fact occurred later, in the Changhsingian mass extinction (Clapham et al. 2009). Instead of a 36 to 47 percent loss of standing biodiversity, the true magnitude of the biodiversity loss that occurred in the Capitanian extinction was more like 25 percent (McGhee et al. 2013). Ecologically, however, the Capitanian extinction was the fifth-most-severe event in the Phanerozoic (table 1.3) (McGhee et al. 2013). Thus the Capitanian extinction is particularly interesting because it is one of the bioevents in Earth history in which the ecological impact of the event—relatively large—was markedly different from the magnitude of the biodiversity loss—relatively small. Why did the Capitanian extinction have such a large ecological impact? The answer may perhaps be found in the cause of the event.

The kill scenario (Retallack and Krull 2006; Retallack et al. 2006; Retallack and Jahren 2008; Bond, Hilton, et al. 2010; Clapham and Payne 2011; Payne and Clapham 2012) goes something like this: Back in the Capitanian Age, the super-plume rising beneath South China first caused the land above to push up into a 1,000-kilometer-wide (620-mile-wide) dome7 and then began to form huge cracks and fissures in the surface of the Earth, accompanied with numerous earthquakes. Fluid basaltic lava began to pour from the fissures, and explosive craters formed along the fissures where hot gases vented into the atmosphere. The hot gases were primarily sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4). The sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide gases reacted quickly with water vapor to produce droplets of sulfuric acid and of carbonic acid (H2CO3), and oxidation of the methane produced even more carbon dioxide.8

In the lower atmosphere of the Earth, clouds of sulfuric and carbonic acid precipitated out as acid rain on the land and in the neighboring ocean waters. In the upper atmosphere, clouds of sulfuric acid droplets injected by volcanic plumes reflected some of the incoming light from the sun and caused the temperature of the Earth below to drop. Each volcanic pulse triggered a cooling pulse in which the Earth remained cold for a period of a decade or more. However, the venting of carbon dioxide and methane from the eruption eventually triggered the reverse—global warming caused by the greenhouse effect of those gases. As the temperature of the atmosphere and the oceans increased, methane frozen in ice in high-latitude permafrost regions on land and buried in submarine sediments in the oceans became increasingly unstable and began to dissolve, bubbling even more methane up into the water and into the atmosphere. Methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and methane releases triggered even steeper increases in the Earth’s temperature.

Ocean waters that had become acidified from sulfuric and carbonic acid rain now became hot and stagnant, producing large “dead zone” areas of anoxic water. With each passing year, the global climate became warmer and the dead regions of oxygen-depleted ocean waters grew larger and larger. Marine organisms began to die from acid poisoning (acidosis), carbon-dioxide poisoning (hypercapnia), and asphyxiation (hypoxia). On land, plants began to die from acid-rain poisoning. Terrestrial areas became more arid with the increased heat of the atmosphere; deserts began to expand and spread. Oxidation of methane in the atmosphere caused oxygen levels to fall and carbon-dioxide levels to rise.9 Land animals died in increasing numbers as a result of climatic stress—from hyperthermia during the summer heat and from hypercapnia in breathing the carbon-dioxide-laced air. Lower atmospheric oxygen levels caused animals to retreat from the highlands of the Earth, and they began to suffer from fluid buildup in and swelling of their lung tissues (pulmonary edema). Herbivorous animals died from starvation as their food, the land plants, died from either acid-rain poisoning or lack of water in newly formed desert regions. Carnivorous animals died from starvation as their food, the herbivores, died. The global ecosystem of the Capitanian world began to collapse, and the fifth-most-severe ecological disruption in the Phanerozoic Eon was the result (McGhee et al. 2013).

As in our modern oceans, reef organisms were particularly sensitive to the change to higher water temperatures and acid-water chemistry in the Capitanian Age. The tropics of the Capitanian world contained many reefs constructed by large demosponges, ancient rugose and tabulate corals, and reef-building microbes (Weidlich 2002; Kiessling and Simpson 2011). These reefs were destroyed in the Capitanian crisis, and, with the exception of some small biostromes and bryozoan reefs, no significant reef-building occurred until the recovery of reef ecosystems some five to seven million years later in the late Wuchiapingian and Changhsingian (Fan et al. 1990; Flügel and Kiessling 2002; Weidlich 2002). Ecologically, the Capitanian extinction triggered a global restructuring of reef ecosystems from complex, multicellular-animal-dominated reef structures to unicellular-microbe-dominated reefs (Flügel and Kiessling 2002).

The reef-building demosponges with their hypercalcified mode of growth (Kiessling and Simpson 2011) were particularly hard hit by the acidification of the world’s oceans by the Emeishan eruption. Another group of large, highly calcified organisms that perished in the extinction were the giant unicells of the photosymbiotic fusulinid foraminifera that we considered in chapter 4. Acid waters impeded the growth of the calcium-carbonate-rich skeletons of the large-bodied and morphologically complex foraminiferal species that had specialized skeletal structures for nurturing and protecting their photosymbiots.10 All of the large-bodied foraminifera were driven to extinction, leaving as survivors only the smaller and morphologically simpler species.11 Large-bodied bivalves with thick calcareous shells that also hosted photosymbionts in their tissues also went extinct.12 The simultaneous extinction of the hypercalcified, large-bodied, photosymbiont-hosting members of what the University of Tokyo Yukio Isozaki and University of Zagreb Dunja Aljinović paleontologists describe as the “Tropical Trio”—the “waagenophyllid corals, verbeekinid foraminifers, and alatoconchid bivalves” (Isozaki and Aljinović 2009)—is a diagnostic feature of the effect of the Capitanian crisis.

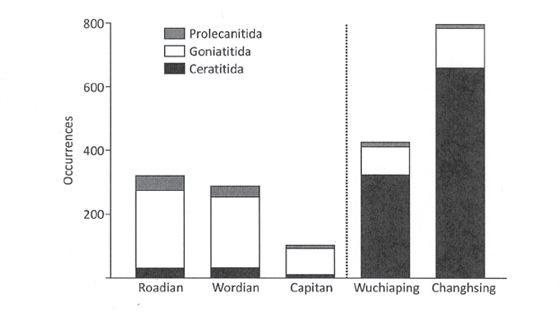

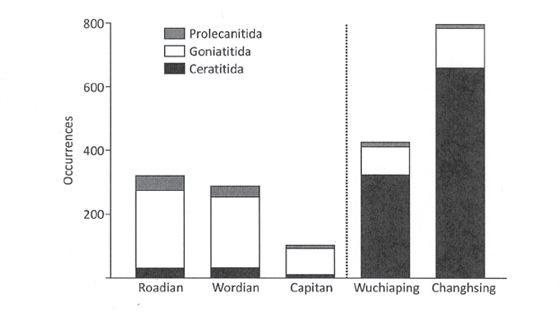

The Capitanian extinction also had a major ecological impact on the ammonoids, which were actively swimming predators in the Capitanian seas. The typical Paleozoic ammonoid faunas were completely replaced by ammonoid faunas that were to become the typical Mesozoic forms—some eight million years before the start of the Mesozoic (Leonova 2009)! Ammonoids of the order Ceratitida first appeared at the Early/Middle Permian boundary, but by the Capitanian only five genera of the order Ceratitida existed, representing 18 percent of the ammonoid diversity. Following the Capitanian crisis, the diversity of ceratite genera jumped to 55 percent in Wuchiapingian and further increased to 74 percent in the Changhsingian (fig. 6.5) (Leonova 2009). The shift in abundance was just as or even more abrupt than the shift in diversity that occurred between the Capitanian and Wuchiapingian, coincident with the Capitanian extinction. These ammonoid faunal changes are reflected in an ecological shift in marine ecosystem structure from bottom-swimming (nektobenthic) ammonoid faunas to open-ocean (pelagic) ammonoid faunas, an ecological shift to a more Mesozoic-style ecosystem structure that we will consider in more detail later in this chapter.

FIGURE 6.5 Occurrence counts for the three late Paleozoic ammonoid orders from data in the Paleobiology Database (www.paleodb.org). An occurrence is the record of a species from a single fossil collection, and is a proxy for abundance. The Capitanian biodiversity crisis is marked by the vertical dotted line. Geologic timescale abbreviations: Capitan, Capitanian; Wuchiaping, Wuchiapingian; Changhsing, Changhsingian.

Source: From McGhee et al. (2013).

The Capitanian extinction may have been more severe ecologically than it was taxonomically because of the environmentally selective nature of the event. For most animal groups, the physiological stresses induced by the Emeishan LIP eruption may not have been sufficiently intense to drive major taxonomic extinctions. In contrast, taxa such as hypercalcified sponges, corals, and larger foraminifera suffered because they had poor physiological buffering and would have been particularly susceptible to the effects of ocean warming and acidification (Clapham and Payne 2011; McGhee et al. 2013). Their elimination triggered major ecological restructuring, particularly in reef ecosystems. Other typical Paleozoic benthic organisms with less developed respiratory systems and low metabolic rates—such as the bryozoan and brachiopod lophophorates—suffered differentially from hypercapnia and hypoxia, as opposed to the more energetic gastropod and bivalve molluscs that were to become dominant in the Mesozoic (Knoll et al. 1996; Retallack and Krull 2006).

The cause of the shift in dominance structure in ammonoid pelagic ecosystems, from the typical Paleozoic mollusc orders of the Goniatitida and Prolecanitida to the more typical Mesozoic order of the Ceratitida (fig. 6.5), is less clear because the biology of these extinct groups is uncertain. It is of note, however, that the ceratite ammonoids also survived the end-Permian mass extinction—also associated with a LIP eruption, as we will see in the next section of the chapter—whereas the goniatites and prolecanitids did not (McGhee et al. 2013).

Finally, the selective extinction of the large-bodied photosymbiont-bearing foraminifera and bivalves during the Capitanian may not have been driven entirely by acidosis. Another possibility is that all photosynthetic organisms—including plants on land—suffered radiation poisoning during the Capitanian extinction (Ross 1972; Bond, Wignall, et al. 2010). In this alternative kill scenario, chlorine and fluorine gases emitted from the Emeishan LIP eruption seriously damaged the ozone layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, permitting the flux of high-energy ultraviolet radiation to greatly increase at the surface of the Earth. As yet, it has not been demonstrated that enough chlorine or fluorine gas was released during the Emeishan eruption to disrupt the ozone layer, but we will see below that the radiation-poisoning kill scenario does indeed appear to apply to the end-Permian mass extinction.

The reader may have noticed a major difference in the scenario outlined above for the environmental effects of the Emeishan LIP eruption and those environmental effects actually recorded in the 1783–1784 Laki LIP eruption that we considered previously. The opening of huge fissures in the Earth, the outpouring of flood basalts, the clouds of hot sulfur-dioxide gas, the formation of sulfuric acid in the atmosphere, the effect of acid rain on land plants and animals, and short-term global cooling all occurred in the historical Laki eruption and are also proposed to have occurred in the Emeishan eruption. What is different is the major presence of two additional gases in the Emeishan eruption—carbon dioxide and methane—and the environmental effects of the long-term global warming produced by these greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of the Capitanian world. The Laki LIP eruption produced in insignificant amount of carbon dioxide compared to the amount of sulfur dioxide it released into the atmosphere (Self et al. 2005). And the Laki LIP is not unusual in this respect—volcanic-generated carbon-dioxide release from the typical basaltic magmas that produce LIPs usually is not large in comparison to the amount of carbon dioxide already present in the atmosphere (Self et al. 2005; Ganino and Arndt 2009).

Why was the Emeishan eruption so different from Laki—what evidence do we have for the additional production of huge amounts of carbon dioxide or methane in the Emeishan eruption some 360 million years ago? There are two lines of evidence: (1) the composition of the sedimentary rocks encountered by the molten magma of the Emeishan eruption on its rise to the Earth’s surface and (2) the composition of the types of carbon released into the Earth’s atmosphere and ocean waters during the time of the eruption.

First, when the rising Emeishan super-plume eventually intersected the bottom of South China and began to melt its way up through the continental crust, it encountered thick layers of sedimentary rock that were present above it in the Sichuan Basin—thick layers of reef limestone (rocks rich in calcium carbonate; CaCO3), dolomite (rocks rich in calcium magnesium carbonate; CaMg(CO3)2), and, in some areas, shales containing petroleum deposits (Ganino and Arndt 2009). Clément Ganino and Nicholas Arndt, geologists at the Université Joseph Fourier de Grenoble, estimate that the Emeishan mantle-plume melting and heating—cooking—of the Sichuan Basin limestone and dolomite strata released between 41.3 and 97.6 trillion tonnes (45.5 to 107.6 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere. This is in addition to the much smaller 11.3 trillion tonnes (12.5 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide emitted directly from the LIP magma itself; thus the total amount of carbon dioxide released into the Earth’s atmosphere during the Emeishan eruption was between 52.6 and 108.9 trillion tonnes (58 to 120 trillion tons).13

In contrast, an Emeishan-sized flood-basalt eruption that occurs where the magma does not encounter any carbonate strata in the surrounding country rock is estimated to inject some 4.2 trillion tonnes (4.6 trillion tons) of sulfur dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere in the eruption plume and an additional 1.2 trillion tonnes (1.3 trillion tons) from the surface area of the lava flows, bringing the total amount of sulfur-dioxide gas emitted to some 5.4 trillion tonnes (6 trillion tons).14 Thus, in the actual Emeishan eruption, the estimated amount of sulfur dioxide released into the atmosphere—5.4 trillion tonnes—is 9.7 to 20.2 times smaller than the amount of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere—52.6 to 108.9 trillion tonnes. The emission of millions of tonnes of sulfur dioxide in the 1783–1784 Laki LIP eruption chilled the Northern Hemisphere of the Earth for two to three years (Thordarson and Self 2003; Schmidt et al. 2012), and the emission of billions of tonnes of sulfur dioxide with each major flood-basalt flow in the Emeishan eruption is predicted to have triggered global cooling pulses that persisted for a decade or longer (Self et al. 2005). Still, the climatic effect of injecting 52.6 to 108.9 trillion tonnes of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into the atmosphere would eventually produce global warming of a magnitude that would swamp the cooling effects of periodic sulfur-dioxide emissions. The planet would heat up and remain hot for hundreds of thousands of years, or for as long as the carbon-dioxide content of the atmosphere remained high (Wignall 2001; Bond and Wignall 2014). In the end analysis, the production of sulfuric acid from the 5.4 trillion tonnes of sulfur dioxide produced in the Emeishan LIP eruption would have had a much larger killing effect by acidifying the world’s oceans and blighting the land areas with acid rain than by periodic global cooling.

Second, the analysis of carbon-isotope ratios not only confirms that an enormous amount of carbon was added to the environment during the time of the Emeishan eruptions, but also raises intriguing questions as to the source of all of the carbon. In short, too much of the lighter isotope of carbon, carbon-12, was injected into the Capitanian atmosphere than could possibly have been produced by a basaltic volcanic eruption alone. How was this conclusion reached? To explain, we know that the carbon atom has two stable isotopes, carbon-12 and carbon-13. Carbon-12 has six neutrons and six protons in the nucleus of the atom, and the heavier isotope carbon-13 has seven neutrons and six protons in its nucleus (carbon has a still heavier isotope, carbon-14, but it is unstable and radioactively decays to nitrogen-14). We also know that living organisms prefer the lighter isotope of carbon in their growth—plants preferentially extract carbon-12 from the atmosphere in their photosynthetic construction of hydrocarbons like sugar,15 and marine animals preferentially extract carbon-12 from seawater in the construction of their calcium-carbonate skeletons.16

Ratio proportions of the two isotopes in geologic strata are customarily reported by an index, δ13C.17 Positive values of the index δ13C indicate an enrichment of the strata sample in the heavier isotope carbon-13 resulting from the depletion of the lighter isotope, carbon-12. Positive values of δ13C are commonly produced by the activity of organisms in marine environments, such as algal blooms, as those organisms preferentially remove carbon-12 from the environment and leave the heavier isotope behind. Negative values of the index δ13C indicate the opposite—an enrichment of the strata sample in the lighter isotope carbon-12. Negative values of δ13C are commonly produced by the weathering of organic-rich sediments—that is, sediments enriched in carbon-12.

A major negative carbon isotope anomaly has been discovered to be associated with the onset of Emeishan LIP volcanism and with the Capitanian extinction (Retallack and Krull 2006; Retallack et al. 2006; Retallack and Jahren 2008; Wignall et al. 2009; Bond, Wignall, et al. 2010). The magnitude of the Capitanian negative carbon isotope anomaly is so great that it could not possibly have been produced by volcanic outgassing of carbon dioxide by the magma intrusions and flood-basalt lavas of the Emeishan LIP eruption. Gregory Retallack and Hope Jahren, geologists at the University of Oregon, further argue that the anomaly is too large even to have been produced by the metamorphism and melting of the Sichuan Basin carbonate reef strata that the Emeishan magmas burned through, producing the massive release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere described by Ganino and Arndt that we examined earlier. A source of even lower carbon-isotope ratios is needed, and Retallack and Jahren argue that that source could only have been methane (Retallack and Jahren 2008; see also Berner 2002).

Where could the methane have come from? Retallack and Jahren point out three possible scenarios for the origin of the methane: (1) deep-ocean water overturn, (2) melting of methane-rich ice deposits,18 and (3) magma intrusion into carbonaceous sediments—sediments containing coal, petroleum, or natural gas (Retallack and Jahren 2008). The first scenario requires the stratification of large areas of the Panthalasan ocean of the Capitanian world (fig. 6.1). Enormous amounts of methane could accumulate and be trapped in stagnant, oxygen-poor bottom waters contained below an upper-ocean oxygenated water-layer cap. Catastrophic overturn of these ocean waters—perhaps triggered by global warming—would release the deepwater methane into the Earth’s atmosphere. Retallack and Jahren argue it is highly unlikely that the huge, globally continuous Panthalasan ocean could have been stratified to such an extent and, moreover, that deepwater overturn would oxygenate the bottom waters, whereas the actual strata and the fossil record indicate that marine anoxia was widespread during the Capitanian extinction.

The second scenario is based on the fact that in our modern world enormous reservoirs of methane exist frozen in the ice of permafrost regions on land and within the pores of sediment located in cold-water, high-pressure regions of the seafloor. If the global climate were to warm substantially, the methane-rich ice located in the high-latitude permafrost regions of the Earth would begin to melt and release the methane gas into the atmosphere. Likewise, with warming ocean waters, the gas hydrates in cold-water submarine sediments would become unstable, dissociate, and release methane into the ocean and subsequently into the Earth’s atmosphere. This scenario is very real and of major concern at present, as the warming of our modern world is already triggering the release of methane from permafrost regions of the planet. Why is this of concern? Carbon dioxide is a potent greenhouse gas, but methane is much worse! The Earth could become much hotter much faster with higher levels of methane in the atmosphere.

However, several lines of evidence exist that the negative carbon isotope anomaly seen in the Capitanian could not have been generated by methane outbursts alone. First, the overall anomaly actually consists of several negative isotopic excursions within the span of time of 10,000 years. Methane release from ice-deposit destabilization and melting should occur as a single catastrophic outburst, as it apparently did in the end-Paleocene hothouse world (Dickens et al. 1995). Following such a catastrophic pulse, it is argued, it would take a “recharge time” of at least 200,000 years for the Earth to accumulate enough methane for another catastrophic outburst (Dickens 2001). In contrast, several such bursts would have had to have happened in less than 10,000 years if the negative carbon isotopes excursions seen in the Captanian were due to methane-rich ice destabilization alone (Retallack and Jahren 2008). Another line of argument is that the overall negative carbon isotope anomaly was produced slowly and gradually, not suddenly and catastrophically. In South China, values of the index δ13C made a major shift in the negative direction at the onset of Emeishan volcanism and the onset of Capitanian extinctions. However, δ13C values continued to shift in the negative direction in strata deposited after the main pulse of the extinction, and only began to return to pre-extinction levels some two conodont zones above the extinction interval. The University of Leeds geologist David Bond and his colleagues argue that the negative shift in δ13C values seen in the Chinese sections was gradual, not abrupt, and that it occurred at a decline rate of one to two per mille per twenty meters of limestone (Bond, Wignall, et al. 2010). Converting this stratigraphic-thickness decline rate into one of measured time is problematic. If—and that is a big if—one assumes that the carbonate strata accumulated at a rate of about ten centimeters (four inches) per thousand years, then the Capitanian negative δ13C shift occurred at a rate of 0.01 to 0.02 per mille per thousand years. In contrast, negative carbon isotope anomalies attributed to the catastrophic release of methane from methane-rich ice destabilization in Jurassic strata show negative δ13C shifts that occurred at a rate of 1.5 per mille per thousand years—roughly two orders of magnitude faster than the negative shift seen in the Chinese Capitanian strata (Kemp et al. 2005). Given the much slower release of carbon-12 into the atmosphere that occurred in the Capitanian, Bond and colleagues argue against a methane-rich ice source for the carbon-12 (Bond, Wignall, et al. 2010). If, on the other hand, one assumes an equal duration of time per conodont zone—another big if, as that implies a constant, clocklike, rate of evolution in the conodont species—the negative δ13C shift occurred rapidly in the time interval from the latest Jinogondolella altudaensis to the earliest Jinogondolella prexuanhanensis conodont zones in South China.

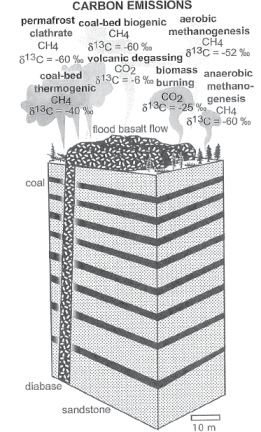

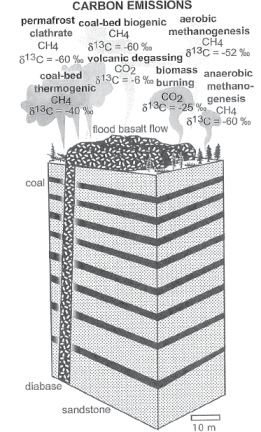

Given these complications with the methane-rich ice-melting scenario, Retallack and Jahren argue that the third scenario—magma intrusion into carbonaceous sediments—was the source of the methane necessary to have produced such large negative carbon isotope anomalies in the Captanian (fig. 6.6). They point out that large diabase dikes (subterranean injection features containing basaltic magma; see fig. 6.6) from the Emeishan LIP, some as much as 200 meters (656 feet) wide, penetrated some 100 meters (328 feet) of Carboniferous coal deposits to the southwest of the main magma mass, and that some of the coal seams in these deposits are up to 12 meters (39 feet) thick. To the northwest of the Emeishan basalts, the Sichuan Basin also contains shale and limestone strata that contain natural gas and petroleum deposits; Ganino and Arndt (2009) argue that these strata may have been metamorphosed by hot magma at depth and may also have been a source of methane release into the atmosphere. Methane release by contact metamorphism of surrounding carbon-rich sediments by the subterranean injection of Emeishan hot magmas would be a longer-term, more gradual phenomenon that the sudden explosive release of methane into the Earth’s atmosphere resulting from methane-rich ice destabilization.

FIGURE 6.6 Model showing the carbon-emission results of intruding hot basaltic lava through strata containing layers of coal: five separate sources of methane (CH4) generation are shown as well as their characteristic negative carbon-isotope signatures (δ13C).

Source: From Journal of Geology, volume 116, pp. 1–20, by G. J. Retallack and A. H. Jahren, “Methane Release from Igneous Intrusion of Coal During Late Permian Extinction Events,” copyright © 2008 University of Chicago Press. Reprinted with permission.

In summary, the debate concerning the exact sources of all of the carbon-12 injected into the atmosphere during the Emeishan LIP eruption continues to be lively, but there is no dispute that massive amounts of carbon dioxide and methane were released—unlike in the historic Laki LIP eruption, in which no carbonate or carbonaceous strata were metamorphosed by the mantle-plume magmas. The Laki LIP eruption was deadly enough, but to produce a really horrendous degradation of the environment of the entire Earth, a LIP also needs to encounter additional sources of carbon during its eruption.

The size and the environmental effects of the Emeishan LIP eruption were outside anything we have encountered in human history, and the eruption triggered the fifth most ecologically severe biodiversity crisis (table 1.3) in the past 600 million years of Earth history, since the evolution of animals in the Neoproterozoic (table 1.1). Yet the 300,000 to 600,000 cubic kilometers of lava produced by the Emeishan mantle-plume eruption was tiny, miniscule in comparison to what was to come at the end of the Permian. And to make matters much worse, the end-Permian mantle super-plume encountered a huge additional source of carbon, a source that was to ignite like a petrochemical bomb.

THE END-PERMIAN MASS EXTINCTION

We have now arrived at the catastrophic end-Permian mass extinction, which nearly ended animal life on the planet Earth about 252 million years ago (Benton 2003; Shen et al. 2011; Erwin 2015). All forms of life, both terrestrial and marine, suffered in that global catastrophe. If it had been only a little more severe, it would have erased the previous 350 million years of animal evolution, leaving only the simplest animals like jellyfish and sponges as survivors. As it was, it triggered a restructuring of the ecosystems of the entire planet, both on the land and in the seas (McGhee et al. 2004), and is recorded in the fossil record as the largest loss of biodiversity ever seen in geologic time.

The series of events that led to the greatest catastrophe in Earth history began innocently enough: organic-rich shales began to be deposited in the marine waters occupying the Tunguska Basin in the eastern Siberian region of what is now Russia. Perhaps this region of the Earth has a propensity for catastrophe, for it is the same region in which the Tunguska asteroid exploded in the Earth’s atmosphere on June 30, 1908, with a force of some ten to 15 megatons of TNT, flattening trees in the surrounding forest over an area of 2,150 square kilometers (830 square miles) (Farinella et al. 2001). Fortunately, no large loss of life is known to have occurred in that event—but that was not to be case with the end-Permian mass extinction.

The strata of the Tunguska Basin contain the oldest petroleum-bearing deposits in the world, formed by the maturation of organic material in Tonian- and Cryogenian-aged source rocks, Neoproterozoic strata that are 1,000 to 635 million years old (see table 1.1 for the geologic timescale) (Svensen et al. 2009; Polozov et al. 2016). These strata range in thickness from one to eight kilometers (0.6 to five miles) and are overlain by thick deposits of carbonate and evaporite rocks (rocks formed by chemical precipitation in the evaporation of seawater) deposited in the Ediacaran Period of the latest Neoproterozoic and the Cambrian Period of the earliest Phanerozoic. During this period of time, the marine waters in the Tunguska basin shallowed and began to evaporate, leaving behind vast deposits of sea salt (NaCl)and anhydrite (CaSO4). At least five different episodes of shallowing and evaporation occurred in the Tunguska basin during the Cambrian, leading to the deposition of up to 2.5-kilometer-thick (1.5-mile-thick) sequences of salt- and anhydrite-rich strata. The largest of these is the Early Cambrian Usolye salt basin, which has an average thickness of 200 meters (656 feet) of salt spread over an area of some two million square kilometers (772,000 square miles) (Svensen et al. 2009; Polozov et al. 2016).

The petroleum-, salt-, and anhydrite-rich strata deposited in the late Neoproterozoic and early Cambrian in the Tunguska basin were then buried successively by carbonates, sandstones, and eventually terrestrial coal deposits as the basin infilled from the Ordovician to the Permian. Under this cover of younger sediments, the oldest petroleum-rich deposits in the world sat quietly like a ticking time bomb. In the Late Permian, that petrochemical bomb would be triggered.

Deep in the Earth beneath the Tunguska basin in Siberia, the second salvo in the volcanic assault that would bring an end to the Paleozoic world was fired—a mantle plume so huge that it has been designated as the “Siberian super-plume”—was rising toward the Earth’s surface. The Siberian super-plume volcanic eruptions would produce the largest known continental LIP in Earth history (Reichow et al. 2009). The total volume of magma produced in the Siberian eruption—in extrusive lava flows and intrusive dikes and sills—is estimated to be at least five million cubic kilometers (1,195,000 cubic miles), with some estimates ranging as high as 16 million cubic kilometers (3,824,000 cubic miles) (Dobretsov and Vernikovsky 2001; Racki and Wignall 2005; Payne and Clapham 2012). Even the lower estimate of five million cubic kilometers is an almost unimaginable volume: try to visualize a black cube of basaltic rock that towers 171 kilometers (106 miles) into the sky, is 171 kilometers wide, and is 171 kilometers long. The Earth’s oceans are only about six kilometers (four miles) deep, on average, so if you were to place such a cube in the middle of the ocean, it would still tower 165 kilometers (102 miles) into the sky, reaching all the way up into the ionosphere of the Earth’s atmosphere. If you were to drive a car at a constant 100 kilometers per hour (62 miles per hour) alongside the base of this cube, it would take you almost two hours to get from one corner of the cube to the next. The minimum estimate for the Siberian LIP volume—five million cubic kilometers—is 8.3 to 16.7 times larger than the 300,000- to 600,000-cubic-kilometer volume estimate for the Emeishan LIP; that is, at the very least, the eruption of the Siberian LIP was equivalent to the eruption of 8.3, and possibly as many as 16.7, Emeishan LIP events taking place all at once.

The Siberian LIP eruption covered five million square kilometers (1,930,000 square miles) of land with flood-basalt lavas. That is a land area larger than one-half of the 48 contiguous states of the United States of America—imagine 62 percent of the U.S. map covered with molten lava— not once, but multiple times: the flood-basalt pile of the Siberian LIP is composed of layer after layer of lava flows. The present-day outcrop of the Emeishan LIP lavas covers some 250,000 square kilometers—the Siberian LIP area is 20 times larger.

What, then, are the expected environmental consequences, in comparison to the Emeishan LIP, of the vastly larger Siberian LIP eruption? Given the huge magma volume and flood-basalt coverage of the eruption alone, one might extrapolate and expect that the environmental effects of the Siberian eruption might be 8.3 to 20 times more severe than those of the smaller Emeishan LIP eruption. But that calculation omits the consequences that were to follow when the rising Siberian super-plume ignited the petrochemical bomb buried in the strata of the Tunguska basin.

Using thermomechanical modeling, the German Georesearch Center (GFZ) petrologist Stephen Sobolev and colleagues argue that the Siberian super-plume arrived below the lithosphere in the northern border of the Siberian Shield about 253 million years ago (Sobolev et al. 2011). It was extremely hot, with a temperature of around 1,600°C (2,900°F), and had a plume-head diameter of around 800 kilometers (497 miles). It began to melt the lower part of the lithosphere at a depth of between 130 and 180 kilometers (81 and 112 miles), and the plume head spread out to a width of 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) just below the lithosphere. Massive intrusion of molten magma via sills and dykes into the lithosphere then began to occur. The super-plume continued to rise and began to break through the lithosphere and into crustal rocks in only 100,000 to 200,000 years. The top of the super-plume was now located at a depth of about 50 kilometers (31 miles), and it began to melt the continental crust. This model predicts that between six and eight million cubic kilometers (1.4 to 1.9 million cubic miles) of molten magma was then intruded into crustal rocks (Sobolev et al. 2011), a prediction that is in accord with the empirical estimates of the volume of the Siberian LIP (Dobretsov and Vernikovsky 2001; Racki and Wignall 2005; Payne and Clapham 2012).

The huge volume of molten magma intruded into crustal rocks through subterranean sills and dykes now encountered the petroleum-, salt-, and anhydrite-rich strata buried between one and three kilometers (0.6 to five miles) below the surface of the Earth in the Tunguska Basin. Beginning around 252 million years ago, the contact of hot magma with the organic- and evaporite-rich strata buried in the basin resulted in the generation of huge amounts of gas at high pressure, subterranean gas that exploded and produced gigantic blast pipes that reached all the way to the surface of the Earth.

About 250 blast pipes filled with magnetite-rich breccia are located in the southern part of the Tunguska Basin in the region characterized by thick deposits of Cambrian salts at a depth of some 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) below the surface of the Earth. Several of these pipes contain iron-ore concentrations of commercial value and are currently being mined for magnetite (Fe3O4). In the northwest region of the Tunguska Basin, outside the region underlain by the Cambrian evaporites, are more than 500 additional blast pipes filled with basalt (Svensen et al. 2009; Polozov et al. 2016).

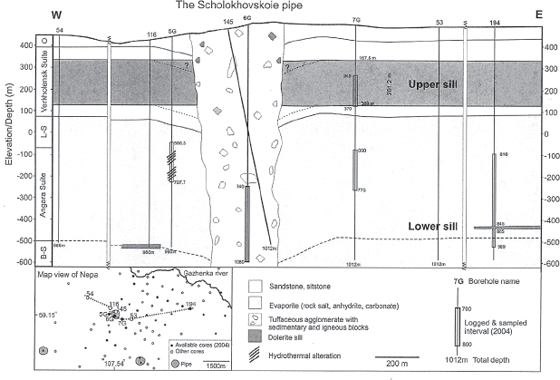

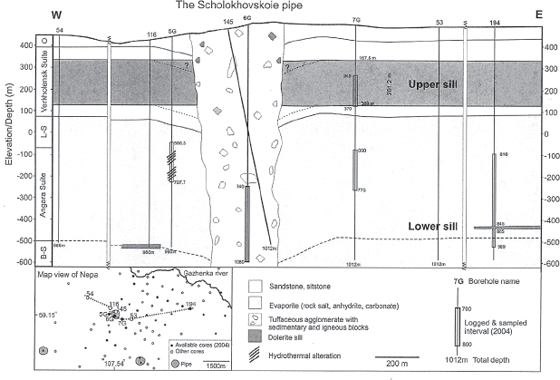

A geologic cross section of one of these explosive pipes, the Scholokhovskoie pipe, is shown in figure 6.7. Because of the commercial value of the magnetite ores contained in the pipe, the strata both within the pipe and surrounding it have been extensively drilled. A massive, 200-meter-thick (656-foot-thick) intrusive-magma sill of dolerite (labeled “Upper Sill” in fig. 6.7)19 is present in the 400 meters (1,310 feet) of Late Cambrian sandstones and siltstones of the Verkholensk Suite strata (topographic elevations of 100 to 400 meters in fig. 6.7). At greater depths, some 800 to 900 meters (2,620 to 2,950 feet) below the surface of the Earth, thinner dolerite sills are located in the thick Early Cambrian salt and anhydrite evaporite strata of the Angara and Bulay Suite strata (lower sills at topographic depths of −400 to −550 meters in fig. 6.7). The blast pipe itself contains large breccia blocks of the Cambrian evaporite strata that have been explosively ejected up the pipe and, back at the end of the Permian, out the mouth of the surface crater onto the surrounding countryside. Also contained within the pipe are breccia blocks from the dolerite sills, proving that the explosions that produced the blast pipe were contemporaneous with the intrusion of the magma intrusions that produced the sills. These magmatic breccia blocks are rich in glass, produced by rapid cooling of the hot intruded magma as it was exposed to air within the pipe.

FIGURE 6.7 Geologic cross section of the upper 1,000-meter (3281-foot) thickness of the strata containing the Scholokhovskoie blast pipe, obtained by subsurface data from numerous drill holes into the strata (inset map, lower left corner of the figure). Strata abbreviations in the left margin of the figure: O, Ordovician; L-S, Litvinstsev Suite; B-S, Angara and Bulay Suites.

Source: From Earth and Planetary Science Letters, volume 277, pp. 490–500, by H. Svensen, S. Planke, A. G. Polozov, N. Schmidbauer, F. Corfu, Y. Y. Podladchikov, and B. Jamtveit, “Siberian Gas Venting and the End-Permian Environmental Crisis,” copyright © 2009 Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

Note that the Scholokhovskoie pipe at the surface of the Earth (fig. 6.7) has a diameter of some 430 meters (1,410 feet) and narrows to a diameter of 300 meters (984 feet) at a depth of 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) below the surface—a geometry produced by the upward and outward force of the explosions that formed the pipe. Other pipes in the region have surface craters that are some 1.6 kilometers wide (one mile wide), an exit-blast diameter that is a mute geologic witness to the spectacular magnitude of the explosions that occurred in this region of the Earth 253 million years ago.

All in all, over 6,400 explosive pipes exist in the Tunguska Basin, and drill-hole geologic samples from many of them have been extensively studied by the University of Oslo geologist Henrik Svensen and his colleagues (2009). The geophysical model they propose for the formation of the Siberian LIP blast pipes is shown in figure 6.8. In the first frame of the sequence (from left to right), the intrusion of a horizontal sill of hot volcanic magma, marked with “V” symbols in figure 6.8, occurs at depth in the Proterozoic strata underlying the petroleum-rich Cambrian evaporite strata (petroleum pools are black ovals marked with white “P” letters in fig. 6.8). In the second frame, a larger sill of hot magma is shown intruding into the Cambrian strata, the thermal volatilization of the petroleum deposits within the strata begins to occur, and the resultant gas expands, shown by the stippled-bounded region and the upward-pointing arrows. In the third frame, the gas explodes at depth and produces the upward blast force (upward-pointing arrows) that creates the pipe, carrying large blocks of the sill rock and surrounding Cambrian strata upward and out of the blast crater at the surface of the Earth. Additional contact-metamorphism and gas production is shown surrounding the degassing sill at shallower depths within the Ordovician strata (upper sill marked with “V” symbols in the upper part of the figure). Finally, in the fourth frame, continued degassing (wavy upward-pointing arrows) is shown from the petroleum-rich Cambrian evaporite strata and the magma layers, and is shown continuing to occur in the pipe itself—illustrated by the bubbles in the waters of the lake now shown occupying the blast crater. In addition, intrusive sills are now shown to come into contact with shallow-buried coal deposits (the uppermost black layer in the top of the figure), and contact metamorphism of the coal produces even more methane degassing, shown by the wavy upward-pointing arrow (Svensen et al. 2009).

FIGURE 6.8 Model of the sequential events (from left to right) that led to the formation of the Siberian LIP blast pipes; see text for discussion.

Source: From Earth and Planetary Science Letters, volume 277, pp. 490–500, by H. Svensen, S. Planke, A. G. Polozov, N. Schmidbauer, F. Corfu, Y. Y. Podladchikov, and B. Jamtveit, “Siberian Gas Venting and the End-Permian Environmental Crisis,” copyright © 2009 Elsevier. Reprinted with permission.

Simply trying to imagine the eruption of one of these pipes is staggering. Suddenly a vast expanse of land—more than 1.6 kilometers (one mile) across, the size of the downtown area of a small city—exploded into the air with a tremendous blast followed by the ground-shaking roar and hiss of a gigantic column of superheated gases and steam jetting upward into the sky. Huge chunks of country rock and glowing-hot magma blobs were sent rocketing across the heavens, arcing away to fall back to the Earth at incredible distances. Thick black plumes of smoke began to billow up from the blast crater, produced by the subterranean burning of coal beds by the hot magma sills. Coal fly ash from these billowing smoke clouds was transported as far as 20,000 kilometers (12,400 miles) from Siberia, around the top of the world, to settle in Canadian High Arctic sediments (Grasby et al. 2011).

If that scenario is difficult to envision, imagine it happening 6,400 times! Svensen and colleagues point out that the eruption pattern of the Siberian LIP blast pipes is unknown. Obviously, if one pipe exploded per year, then the entire process took 6,400 years, but it is much more likely that pipe formation was clustered in time—probably starting out with the occasional blast of a single or a few pipes erupting as the initial magma intrusions reached the buried Cambrian petroleum-rich evaporite strata, followed by a period of time with numerous pipes exploding simultaneously across the landscape during the phase of maximum heating and magma intrusion from the head of the mantle super-plume located at depth, and ending with a tapering off of pipe formation as the subterranean magma masses cooled. In that scenario, the formation of the Siberian LIP blast pipes took place in a time interval much shorter than 6,400 years.

Svensen and colleagues have conducted extensive heating experiments with geologic samples of the Siberian LIP strata, obtained through numerous drill holes produced by prospectors searching for petroleum, magnetite, and potassium salt deposits. They have concluded that the Siberian LIP blast pipes vented between 39 and 114 trillion tonnes (43 to 125 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide, plus an additional 20 trillion tonnes (22 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide degassed from the lava. In addition, the contact metamorphism of coal and other organic-rich strata by the Siberian mantle super-plume magmas is estimated to have released between 14.3 and 41.9 trillion tonnes (16 to 46 trillion tons) of methane. The coal fly ash produced by the burning of the Siberian LIP coal beds also contained high levels of the toxic metals chromium, arsenic, mercury, and lead (Grasby et al. 2011, 2017).

The carbon dioxide and methane vented from the burning of petroleum- and organic-rich rocks produced a huge injection of the light carbon-12 isotope into the atmosphere (Svensen et al. 2009). Analyses of the resultant negative δ13C excursion found in end-Permian strata have led the Stanford University geologist Jonathan Payne and colleagues to estimate an even higher volume of vented carbon-dioxide gas from the Siberian LIP—some 100 to 160 trillion tonnes (110 to 176 tons)—than that estimated by Svensen and colleagues (Payne et al. 2010).

In addition to organic-rich rocks, the Siberian LIP magmas encountered a type of rock not present in the Emeishan LIP area—the Cambrian evaporite strata, thick deposits of rock salt and anhydrite. The burning of rock salt, or halite, released sodium metal and chlorine gas, both of which are poisonous. The Siberian LIP chlorine gas interacted with water vapor to produce rock-salt-derived hydrochloric acid, in addition to the amount produced by the magma itself. Even more serious, however, is that the vented chlorine gas combined with the huge amounts of methane also released by the Siberian LIP to produce a very noxious gas—methyl chloride (CH3Cl). Svensen and colleagues estimate that between 5.2 and 15.3 trillion tonnes (5.7 to 16.9 trillion tons) of methyl-chloride gas were released into the Earth’s atmosphere by the Siberian LIP. Finally, the presence of bromine in the Cambrian evaporite strata is estimated to have produced another noxious halocarbon gas in bromine’s combination with methane—methyl bromide (CH3Br). Although smaller than the huge volume of methyl chloride produced by the Siberian LIP, Svensen and colleagues estimate that between 87 and 255 billion tonnes (96 to 281 billion tons) of methyl bromide were emitted into the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of the Permian (Svensen et al. 2009). The consequences of the formation of these two halocarbon gases by the Siberian LIP were dire indeed, as we will see shortly.

Finally, it is estimated that the Emeishan LIP eruption produced about 5.4 trillion tonnes of sulfur dioxide, as discussed previously. Since the Siberian LIP flood-basalt eruption was 8.3 to 20 times larger than the Emeishan, one might conclude that the Siberian LIP lavas would have produced 8.3 to 20 times more sulfur dioxide. But that calculation does not consider the effect of the thermal metamorphism of the other evaporite rock type present in the Cambrian evaporite strata—thick deposits of anhydrite. Anhydrite is a calcium sulfate, and burning anhydrite produces sulfur dioxide gas in addition to the amount produced by the magma itself; thus, the potential amount of sulfuric acid produced by the Siberian LIP eruption was even greater than would be anticipated based on the size of the flood basalts alone.

Can the Siberian LIP scenario get any worse? The answer is yes. The thermomechanical modeling of the Siberian super-plume by Sobolev and colleagues suggests that about 10 to 20 percent of the magma volume produced did not come from the deep mantle alone but rather from the melting and recycling of oceanic crustal rock located beneath the continental crust of Siberia—oceanic crust that had been subducted beneath the continental crust of Asia in earlier plate-tectonic events. If so, the magma produced by the super-plume would be much more gaseous and carbon rich than the typical basaltic-type lavas seen in LIP eruptions like those of Laki, Iceland. Sobolev and colleagues estimate that the degassing of the modeled super-plume magmas could have produced about 175 trillion tonnes (193 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide—an amount greater than the estimated 39 to 114 trillion tonnes of carbon dioxide vented through the Siberian blast pipes from the subsurface thermal metamorphism of the Tunguska Basin petroleum-rich strata! In addition, a surprising amount of hydrochloric acid is also modeled to have occurred solely from the degassing super-plume itself—some 18 trillion tonnes (20 trillion tons) (Sobolev et al. 2011).

In this scenario, Sobolev and colleagues suggest that “CO2 from the plume alone may have triggered the main extinction event … degassing of the plume, rather than thermogenic gases from sediments, triggered the biotic crises” (Sobolev et al. 2011, 314–315). However, we know that the thick deposits of petroleum-, coal-, and evaporite-rich strata in the Tunguska Basin were thermally metamorphosed, and the explosive result of that metamorphism is evidenced by the 6,400 blast pipes present in the basin today. In addition, we know that the burning of the Tunguska Basin coal deposits produced huge clouds of carbon-rich ash, ash in such quantities that it was transported aloft some 20,000 kilometers away to Canada (Grasby et al. 2011). Thus, rather than an alternative source of carbon dioxide, the Siberian super-plume model of Sobolev and colleagues may provide an additional source of trillions of tonnes of carbon dioxide to add to the trillions of tonnes produced by thermogenic degassing from the Tunguska Basin petroleum-rich strata—making an originally catastrophic environmental scenario much worse. In this combination scenario, catastrophic degassing from the deeper super-plume itself began shortly before the main flood-basalt eruptions, followed by additional catastrophic degassing from the shallower Tunguska Basin petroleum-rich evaporite strata during the flood-basalt eruptions.

THE END-PERMIAN KILL MECHANISMS

The predicted environmental consequences of the injection of teratonnages of both methane and carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere by the huge Siberian LIP eruption are the same as they were for the earlier and smaller Emeishan eruption, just very much worse (table 6.1). Methane and carbon dioxide are both greenhouse gases—methane much more so than carbon dioxide—and global heating of the planet is expected with high concentrations of these two gases in the atmosphere. Methane is particularly bad in that it retains heat itself and, when oxidized, also produces carbon dioxide, a gas that continues to retain heat in the atmosphere.

TABLE 6.1 Pollutants produced by the Siberian LIP eruption and their global environmental impacts.

| Pollutant/Pollutant Product |

Environmental Impact |

| Sulfur dioxide/sulfuric acid |

Acidification of oceans, acid rain on land |

| Carbon dioxide/carbonic acid |

Acidification of oceans, acid rain on land |

| Chlorine/hydrochloric acid |

Acidification of oceans, acid rain on land |

| Atmospheric sulfur dioxide |

Short-term global cooling |

| Atmospheric carbon dioxide |

Long-term global warming |

| Atmospheric methane |

Long-term global warming, global oxygen depletion |

| Chlorine/methyl chloride |

Atmospheric ozone destruction |

| Bromine/methyl bromide |

Atmospheric ozone destruction |

| Coal fly ash |

Oceanic euxinia and anoxia, metal toxicity |

Kill Mechanism 1: Heat Death

The nearly unbelievable seriousness of the magnitude of the heating of the Earth that occurred at the end of the Permian and into the Early Triassic can be sensed in the wording of the titles (usually pretty staid and descriptive) of numerous scientific papers in research journals that have revealed the enormity of the event—titles such as “Hot Acidic Late Permian Seas Stifle Life in Record Time” (Georgiev et al. 2011), “Lethally Hot Temperatures During the Early Triassic Greenhouse” (Sun et al. 2012), and “Post-Apocalyptic Greenhouse Climate Revealed by Earliest Triassic Paleosols” (Retallack 1999). The language within many of these scientific papers is just as startling—for example, from a study using the ratios of rhenium (Re) and osmium (Os) isotopes in calculating seawater variation in temperature and acidity, “If temperature was indeed the controlling factor, the extreme 187Re /188Os ratios in the Upper Permian time require global warming at levels unparalleled in the geologic record…. Such ratios are unknown from any other period in Earth history” (Georgiev et al. 2011, 397, 399).

The standard technique for calculating past temperatures is to measure the ratios of oxygen isotopes (δ18O) preserved in the skeletal elements of organisms alive during the study interval, usually the shells of brachiopods or the dentary elements of conodonts (McGhee 2013, 196–199). Using the δ18O index values found in the dentary elements of conodonts, the China University of Geosciences geobiologist Yadong Sun and colleagues have reconstructed seawater temperatures in the late Changhsingian to early Middle Triassic. Their research has revealed that seawater temperatures rose rapidly from 21°C (70°F) to 36°C (97°F) across the Permian/Triassic boundary. This rapid rise in temperature was interrupted by a cool pulse, when seawater temperatures dropped back to a still-quite-warm 32°C (90°F)—because of renewed volcanic eruption of sulfur dioxide?—before rising to the highest temperatures seen in their study: seawater temperatures of 38°C (100°F) and sea-surface temperatures of 40°C (104°F) in the mid-Olenekian Age of the Early Triassic.20

Seawater temperatures above 35°C (95°F) are lethal for most marine organisms, triggering hyperthermia (table 6.2). Yet the study by Sun and colleagues show that seawater temperatures remained above 35°C for almost the entire Early Triassic, a span of 5.1 million years, before finally falling back to the very warm range of 32°C to 34°C (90°F to 93°F) at the onset of the Middle Triassic Epoch. At present, sea-surface temperatures in the equatorial zone of the Earth—the hottest part of the Earth—range between 25°C and 30°C (77°F to 86°F). High seawater temperatures also lead to lower oxygen solubility and thus facilitate the development of marine anoxia, a fact we will return to when we consider the hypoxic kill mechanism in detail (table 6.2).

TABLE 6.2 Kill mechanisms triggered by the Siberian-LIP-induced global environmental changes listed in table 6.1.

| Kill Mechanism |

Organisms Adversely Affected |

| Hyperthermia (heat death) |

Large animals (both marine and land), energetic animals with higher metabolic rates, marine sessile benthic organisms, land plants |

| Acidosis (acid poisoning) |

Marine uni- and mullticellular organisms with calcified skeletons, marine sessile benthic organisms, land plants |

| Hypercapnia (CO2 poisoning) |

Large animals (both marine and land), marine uni- and multicellular organisms with calcified skeletons, marine animals with poorly buffered respiratory physiologies, marine sessile benthic organisms |

| Hypoxia (suffocation) |

Large animals (both marine and land), energetic animals with higher metabolic rates, marine sessile benthic organisms |

| Radiation poisoning |

Land plants, land animals that cannot burrow to escape surface radiation |

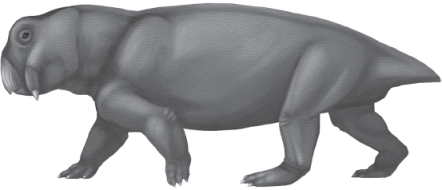

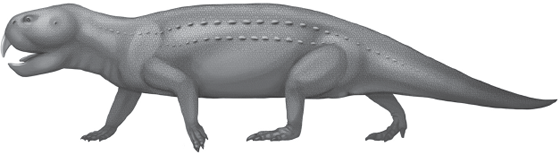

On land, photorespiration starts to seriously interfere with plant photosynthesis at temperatures above 35°C (95°F), and few terrestrial plants can survive temperatures higher than 40°C. At temperatures of 45°C (113°F), land animals begin to succumb to hyperthermia (Sun et al. 2012). The Université Claude Bernard geochemist Kévin Rey and colleagues have analyzed the δ18O values found in the bones and teeth of terrestrial vertebrates in South Africa and have reported that at the end of the Permian “an intense and fast warming of +16°C [+29°F] occurred and kept increasing during the Olenekian” Age of the Early Triassic (Rey et al. 2016, 384). All in all, the end-Permian hot pulse in air temperatures on land “lasted 6 Ma [million years] before temperatures decreased” in the Anisian Age of the Middle Triassic (Rey et al. 2016, 384).

In the “Hot Earth” of the latest Permian and Early Triassic, the equatorial tropics were lethal zones both on land and in the sea—in stark contrast to our modern world, where the equatorial tropics harbor the highest diversity of life on the planet. The equatorial marine zone of the Hot Earth was full of “gaps”—the “marine fish gap,” the “marine reptile gap”—marked by the absence of life-forms driven out of the tropics to higher latitudes of the planet where temperatures were survivable (Sun et al. 2012). Individuals of marine species that managed to survive in the Hot Earth equatorial seas were all abnormally small and stunted—a phenomenon known as the Early Triassic “Lilliput effect” (Twitchett 2007), which Sun and colleagues (2012) argue to be the result of the low thermal tolerance range of organisms with large body sizes. The equatorial land areas of the Hot Earth saw the “tetrapod gap,” the “coal gap,” and the “conifer gap”—the absence of tetrapods, the absence of peat swamps, and the absence of conifers (Retallack et al. 1996). Instead of the highly derived conifer seed plants, the flora of the equatorial Hot Earth were dominated by peculiar primitive spore-reproducing lycophytes, relatives of the ancient lycophytes that dominated the coal swamps of the Carboniferous world that we considered in chapter 3. Only in the marginally cooler Middle Triassic Earth would the tetrapods and conifers once again return to the equatorial regions, and peat swamps once again form (Sun et al. 2012).

Kill Mechanism 2: Carbon Dioxide Poisoning

Carbonic acid formed from both carbon dioxide and methane acidified the oceans and produced acid rain on land. To the acid effect of trillions of tonnes of both gases was added the trillions of tonnes of sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid produced both from the mantle super-plume itself and from the thermal metamorphism of the Tunguska Basin petroleum-rich evaporite strata (table 6.1). To make matters even worse, the ocean chemistry of the Paleozoic world was not like that of our present world. Jonathan Payne and his colleagues point out that the Earth’s oceans today are “buffered against acidification by extensive, fine-grained, unlithified carbonate sediments on the deep-sea floor, which could relatively rapidly dissolve to counter acidification. By contrast, the Late Permian deep sea contained no such carbonate buffer because Permian oceans lacked abundant pelagic carbonate producers such as coccolithophorids and planktonic foraminifers. Consequently, any buffering against acidification via dissolution of carbonate sediments could only have occurred more slowly in the less extensive, coarse-grained, mostly lithified, shallow-marine carbonate platform sediments or via chemical weathering of silicate and carbonate rocks on land” (Payne et al. 2010, 8546; see also Ridgwell 2005) and “In the absence of a large reservoir of fine-grained, unlithified deep-sea carbonate sediment, whole-ocean acidification could likely last for tens of thousands of years (Archer et al., 1997), and few refugia would exist—survival would depend primarily on long-term physiological tolerance of altered conditions” (Payne and Clapham 2012; Clarkson et al. 2015).

Biological evidence corroborates the hypothesis that the acidification of the world’s oceans during the end-Permian mass extinction was much worse than it was during the earlier Capitanian crisis. During the eruption of the Emeishan LIP, highly calcified organisms like massive corals, large-bodied fusulinid foraminifera, and giant alatoconchid bivalves suffered high extinction losses relative to organisms with lightly calcified skeletons. However, during the eruption of the Siberian LIP, all organisms with calcareous skeletons suffered high extinction losses. In fact, having a skeleton composed of anything other than calcium carbonate was highly beneficial in surviving the end-Permian mass extinction (Clapham and Payne 2011). This differential survival pattern is particularly striking within clades of closely related organisms: many species of calcareous foraminifera went extinct, whereas those foraminifera that formed their skeletons by agglutinating siliceous sedimentary grains survived; many species of calcareous brachiopods went extinct, whereas the inarticulated brachiopods with phosphatic shells survived; many species of calcareous sponges went extinct, whereas siliceous hexactinellid sponges survived; species of calcified corals and algae went extinct, whereas unskeletonized corals (naked cnidarians, like modern sea anemones) and unskeletonized algae survived; and so on (Knoll et al. 2007; Clapham and Payne 2011; Kiessling and Simpson 2011; Garbelli et al. 2017).

A surprising contrast to the deadly effect of acid-rich seawater on calcareous organisms is the discovery of peculiar primary deposits of calcium carbonate on the seafloor in some areas, deposits of odd fan-shaped crystal structures that can be some ten centimeters (four inches) in diameter. These calcium-carbonate fans and crusts are thought to have been produced in the aftermath of an oceanic acidification event, following the death of most benthic organisms with calcareous skeletons, and the upwelling of alkaline deep waters supersaturated with calcium carbonate—but no organisms to take up the calcium carbonate for their skeletal constructions—resulted in these primary sedimentary carbonate deposits (Payne and Clapham 2012). Finally, on land, the deadly effects of acid rain, such as those that were seen in Europe with the historic Laki LIP eruption, were added to the already deadly effects of hyperthermia in killing off land plants.

Added to the deadly effects of sulfuric, hydrochloric, and carbonic acids in marine waters is the related effect of high concentrations of simple carbon dioxide in ocean waters—hypercapnia, or carbon-dioxide poisoning (table 6.2). Hypercapnia preferentially kills many of the same organisms as acidosis, but with a few differences. Animals with poorly buffered respiratory physiologies are least able to deal with the deadly effects of carbon-dioxide poisoning; these animals include the sponges, corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, and most echinoderms. In contrast, energetic animals with well-buffered physiologies are better able to deal with carbon-dioxide stress; these animals include the molluscs, arthropods, chordates, and infaunal organisms in general, which are adapted to living within submarine sediments where oxygen partial pressures are low and carbon-dioxide partial pressures are high (Knoll et al. 1996, 2007; Clapham and Payne 2011). The differential survival rates of these two groups of organisms provide an important key to understanding the radical ecological reorganization that ended the Paleozoic world—an ending we will consider in detail later in this chapter.