I would like to conclude this presentation of the issues that animate the field of body psychotherapy around some themes developed by George Downing in his courses and publications. I have the impression that his school best integrates the psychology of today in body psychotherapy. His thoughts can be used as a starting point to open up some discussions that are in the process of elaboration in the congresses and publications in body psychotherapy at the start of the twenty-first century. This will be the occasion to include recent developments in my mapping of what the field of body psychotherapy is becoming.

George Downing, a psychologist of American origin, resides in Paris. In the late 1960s Downing lived in California, in the San Francisco area. It had become one of the regions in which one could find the greatest density of Nobel Prize winners. The fabulous creativity of this region was not only manifest in the hard sciences and technology. It also expressed itself by developing psychotherapeutic modes of intervention that are close to the themes developed in this book, such as Gestalt therapy, various modes of intervention centered on body awareness, and systemic approaches. It was then a harbor of intense creativity for those who looked for new modes of intervention that could support the development of not only psychiatric patients but also every citizen who felt a need to enhance the way he or she functioned and understood himself or herself. In such a stimulating context, many wanted to find ways of picking and choosing from different approaches, with the aim of discovering new frames for psychotherapy. Although schools were still the recognizable pillars of this landscape, many hoped to find a form of psychotherapy that could combine in a synergistic way the most efficient psychotherapeutic tools. Downing was one of many searching for such a direction. This stance quickly spread to other areas of America and Europe.

Since 1959, the Mental Research Institute of Palo Alto has been one of the leading sources of innovative models which have influenced interactional and systemic therapies (Watzlawick et al., 1967). It is close to Stanford University, about an hour from San Francisco. This institute was animated by brilliant clinicians and researchers such as Gregory Bateson, Donald Jackson, Jay Haley, and John H. Weakland. Already then, Gregory Bateson was a bridge between systemic approaches, anthropology, and studies on nonverbal communication.

At the time, Downing was teaching both individual and systemic therapy at the California School of Professional Psychology and at a family therapy training institute. He was convinced that all types of therapy could benefit from a more meticulous attention to the concrete specifics of how patients interacted with others. The clinical methods of observation and intervention used in body psychotherapy were one of the tools that could help clinicians to improve the finesse of their approaches.

Downing’s initial theoretical formulations drew strongly upon then-current psychodynamic thinking. He had previously written a doctoral dissertation on Freud, participated in a number of psychoanalytic seminars, and thought seriously about becoming a psychoanalyst. He was particularly interested in their sophisticated understanding of transference and countertransference in the therapeutic relationship. In this intellectual context, developing Ferenczi’s active technique could become a way of linking bodywork, systemics, and classical psychotherapy.

While he was developing his ideas in systemic and psychodynamic approaches, Downing was involved in the creative interest in the body that developed in California: body re-alignment methods, body awareness, and body psychotherapies (as shown in Kogan, 1980). He went through trainings in a number of them, including the approaches of Stanley Keleman (1970) and Magda Proskauer (1968), as well as Bioenergetic and Reichian therapies. In 1972, he published a reference book on “Californian massage.” He was interested in the modes of intervention developed in body psychotherapy schools, but was skeptical of their theoretical formulations which he found too “esoteric” (Downing, 1980) as well as conceptually lacking in rigor.1

Gradually his intent became to develop a synthesis of what he found most useful in each perspective,2 and create a viable theoretical framework for the more heteroclite vision of psychotherapeutic approaches that was emerging. The shift of paradigm that emerged encouraged eclectic or integrative psychotherapists to reframe the methods discovered by the classical psychotherapy schools into new modes of intervention. Methods included techniques (free association, coding nonverbal behavior, or massage) and local models (transferential dynamics, auto-regulation, and interaction). These methods were then redefined in an operational way, in function of current clinical needs, and situated in a viable theoretical framework that could integrate the ongoing development of psychological research. This attempt to find theories that were closer to scientific thinking than what had been produced by psychotherapy schools led to a variety of new outlooks and methods. The term eclectic is a slightly pejorative term for psychotherapists who do not follow the tracks proposed by psychotherapy schools. In the future, we should find a more honorable name for colleagues who prefer to follow the cognitive ethics of academia. There have been many highly varied attempts to create such eclectic psychotherapeutic approaches, which are becoming increasingly popular. In all of them, integrating classical methods and models can only be done after a reformulation of what is being assimilated. For Piaget (1985), a new way of integrating old schemas inevitably requires some mutual accommodation and the creation of new schemas to equilibrate the emerging structure. George Downing’s proposition is a particular blend that has several characteristic features. One them is his way of integrating body psychotherapeutic approaches. This book follows a complementary path.

The San Francisco Bay area (as well as other parts of California) was the best place, at the time, to accomplish such a synthesis. Far from the East Coast of the United States, it was easier to have some distance from the fanaticism of the Reichians and the rigidity of the Freudians and to profit from the filtering of the Reichian contributions going on at Esalen. Otto Fenichel died in California. It is not impossible that people influenced by Fenichel (e.g., Laura Perls and the Gindlerian group) influenced Downing. However, this influence was probably indirect, as Downing sometimes refers to him, but he does not discuss Fenichel’s ideas.

One of Downing’s constructive critics of current body psychotherapy was to situate the contributions of Reich in the context of the 1930s and show that he was part of a milieu fighting for a better understanding of the interaction among the mind, the body, and behavior. Thus, Downing takes up the contributions of Groddeck (often underestimated), Ferenczi, and the gymnasts who influenced the first Reichian therapists. Reich is no longer the tree that hides the forest but one of the grand trees in a forest of people who want to improve our understanding of the relation among minds, affects, and body. Downing is probably the first in the field to publish an explicit critical discussion on “Reich’s dubious heritage” (Downing, 1996, V.26) that does not lead to a rejection of body psychotherapy.

In 1980, George Downing moved to Paris, where he still lives. Several important changes then took place in the following years. He accepted an invitation to work as a psychologist in a psychiatric unit at Salpêtrière Hospital. This unit, newly created at the time, specialized in the treatment of parent-infant and parent-child relationships from the ages of zero to three years. The body-mental-systemic focus of interest remained, but for each dimension his approach took a new turn:

The 1980s was the time when many of us, including George Downing, discovered the new psychodynamic approaches developed by Heinz Kohut (1971) and Otto Kernberg (1975, 1976, 1984) to treat patients with narcissistic and borderline personalities. His collaboration with Beatrice Beebe put him contact with relational psychoanalysis, such as it was developed by Steven Knoblauch (2000), Joseph D. Lichtenberg (1989), and Thomas Ogden (1990, 2009). This psychoanalytic movement integrates a systemic perspective on behavior and interaction.

As Downing’s new job included work with children, he integrated formulations on developmental systemics (Thelen and Smith, 1994; Fogel, Lyra, and Valsiner, 1997). To integrate technics developed in nonverbal communication studies for his video-analysis interventions, he also learned to use strategies developed by cognitive and behavioral therapy (Ryle and Kerr, 2002; Young, Klosko, and Weishaar, 2003; Bateman and Fonagy, 2006). One of the advantages of these new methods is that they are easily adapted to mental health settings.

He therefore needed to create a developmental model in which he could combine the various approaches he was using at the Salpêtrière Hospital. He then developed training in video analysis called Video Intervention Therapy (VIE).3 It is often used to support mothers who have difficulty living with the prospect of an infant coming into their lives (see chapter 21, p. 629f). This method can also be used to analyze other contexts, such as the dynamics of a family or the integration of children who suffer from attention deficit disorder. The work of video analysis makes it possible to analyze, with the patient, the minute behavioral practices he or she uses without noticing. Following the lead of Beebe, Tronick, and several other researchers, he worked out a mode of observational analysis based on what videos allow one to observe in detail. A video would be filmed of a parent and infant, or of an adult couple, or of some other close human relationship. The therapist and the patient or patients would then look at the video together, investigating both outer behavior as well as the inner dynamics driving it. Because so much of interaction depends upon how a participant is using his body, as well as how he is influencing and being influenced by the bodily reactions of the other person, it was for Downing a natural step to draw on body and other experiential techniques in such an intervention.4

Once the therapist has isolated some detailed behaviors, he can show these behaviors to the patient and they can discuss them. Such a detailed analysis of their behavior is difficult for many patients to accept and integrate. The patient often has the impression that he is being shamed for something he did not intend to do. He therefore does not feel responsible for it. When the therapist shows the patient the impact of his nonconscious practices on other people, he may feel caught in a trap. The therapist who uses video analysis must therefore find ways of conveying what is visible that can be used constructively and integrated by a patient. For example, a therapist can choose moments when the patient’s behavior was relevant for all those concerned, and start with a discussion on why these moments are examples of a useful way of doing things.

Once a patient has a clearer view of problematic aspects of his behavior, he needs to integrate what has been made explicit, so that the underlying organismic regulation systems can find new ways of assimilating what has been observed, and to accommodate by forming new behavioral patterns. This integration is often accomplished with the classical tools of psychotherapy. Downing may also use body psychotherapy techniques to do this. For example, the patient may explore how one of his habitual gestures mobilizes other aspects of the general posture and how it influences respiration. He may also become aware that this exploration triggers new somatic sensations, emotions, and memories. Downing also utilized new ways of using gestures to explore certain aspects of the patient’s dreams (Clara Hill, 2004). Bodywork is also used to connect an isolated schema to underlying vegetative mobilizations. For example, a patient may find ways of associating an aggressive facial expression to impressions that have been activated by the autonomic nervous system (Downing, 2000, pp. 251–254). He will then be able to clarify the contour of his anger by putting together what he can feel when his attention explores what is happening in his face, gestures, breathing, heartbeat, and thoughts. Finally, bodywork can help the patient contact lost feelings that formed themselves at a very early time, before memory could be stored in the format of mental representations.

Downing’s theoretical framework has also become one of an enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy. He now works within this tradition, but with the difference that the experiential side includes a substantial amount of focus on the body itself.

Downing teaches video analysis and body psychotherapy in a post-training framework for professionals who are practicing in institutions or in a private setting. He teaches both individual and interactional work in hospitals and universities in several European countries. He is also part of several research teams concerned with parent-infant and parent-child interaction. Many of the persons trained by him are working in mental health institutions: psychiatric hospitals, eating disorders units, substance abuse centers, and home visiting programs for high-risk families. The techniques he teaches can be used in a variety of settings: individual therapy, work with dyadic and triadic5 interactions, or groups and families.

In 1996, Downing published a first synthesis of his approach, titled Wort und der Psychotherapy (Body and Words in Psychotherapy).6 It announces a type of psychotherapy capable of surpassing the formulations elaborated in isolation within each school and at last joining the academic spirit proposed by Plato.

Bodily defenses. Amazingly, this aspect has not been researched in experimental psychology. But it is so important I will mention it too. . . . It is familiar ground to many psychotherapists. (George Downing, 2000, “Emotion Theory Reconsidered,” p. 255)

One of the first aspects of body psychotherapy theory that George Downing openly disagreed with is the claim that a body psychotherapist needs to believe in cosmic energy to understand how to work. Like Peter Geissler (1997), he thinks that clinicians trained in a neo-Reichian school (e.g., Bioenergetics) will improve their way of working if their energetic models are based on the dynamics of metabolic energy. The practitioner consequently has knowledge at his disposal that is more refined, more precise, and easier to renew.7

As the epigraph at the beginning of this section indicates, knowing the academic models in no way stops the practitioner from observing phenomena that the current scientific knowledge cannot explain. For example, I have indicated that the vibrations observed during a grounding exercise or the orgastic reflex are not explained in any satisfactory way by scientific research (see chapter 19, p. 563). To point out those observations that require more research is our duty. To use these observations to justify the use of notions such as cosmic energy or philosophical idealism is another thing altogether. In defining the phenomena that we observe in a comprehensible way for researchers and practitioners, we participate in the universal and collegial adventure that is the development of the human sciences.

When an individual feels a body sensation—like the impression of warmth or pins and needles—circulate in his body, the individual often spontaneously uses the notion of the circulation of energy to express what he feels. This feeling is close enough to what is currently designated by the word energy,8 to the extent that what is felt is a new activity in the organism, probably formed by the still poorly understood affective vegetative mechanisms.

This brings us back to an earlier theme9 that takes up the idea that an impression is a sort of sensory metaphor. These metaphors are ways of informing consciousness that something complex is going on in the organism. They summarize, with an impression accessible to consciousness, a dynamic that is often too complex to be taken up consciously. A perceptional metaphor has the particular ability to vary correlatively with the events described without necessarily corresponding to them. The danger with this type of procedure is to approach a metaphor as an exact representation of what is going on. To feel that something is coming up in me does not necessarily mean that a substance, distinct from physiological mechanisms, is flowing toward my head. What comes up may be a multitude of different activities. A well-known example, brought up when talking about Shultz’s Autogenic training (chapter 9, p. 282f), is the association between the sensation of warmth and vascular dynamics, or the sensation of heaviness and muscular relaxation. To feel warmth that spreads in the body while doing an exercise is not feeling the blood being distributed in the arteries. There is a correlation between the two phenomena, but not an identity. Acupuncturists and Reich (probably others also) do not believe that the sensation of warmth always follows vascular dynamics. They may be right when they assume that vegetative sensations often cannot be explained by the current knowledge in anatomy and physiology. That does not necessarily imply that these impressions are caused by a chi or an orgone that remain unexplained phenomena. However, one can argue that these “nonscientific models” support a curiosity and a particular sharp awareness of certain phenomena, while classical physiology may support a form of indifference for the same phenomena. The issue here is why one’s attention focuses on some events and not on others. Having a clinical sense of what phenomena should be carefully explored that is as independent as possible from theoretical issues is of utmost importance for patients. They need therapists who are inspired by precise phenomenological descriptions of the dynamics of their sensations. What sometimes happens with these discussions is that future research will come up with a new series of data which will lead to a third solution that is not a synthesis of the previous ones but one that no one imagined.

The role of the psychotherapist is not to believe or refute the explications of the patient who states that he feels his spiritual energy moving upward (see chapter 10, p. 279f). It is to explore more precisely with the patient what he feels and how this feeling is related to his thoughts, his gestures, his affects, and his organism. The fact that what we observe cannot always be described by a reliable scientific model ought not to discourage us; on the contrary, it should encourage us to research more refined descriptions of what is being experienced to define the contours of what we would want scientists to focus on.

The neurotic . . . never reacts to the external stimuli in an appropriate manner, but always according to defined reactive schema acquired during infancy. . . . He continuously distorts the present according to the meaning of his unfinished past and as much for his actual instinctual drives as for the actual external reality. . . . The desire experienced by a subject, at a certain moment, to do or to say something, tends to suppress the drives that do not lead to that end. (Otto Fenichel, 1941, Problems of Psychoanalytic Technique, III, pp. 36–37; translated from the French by Marcel Duclos)

I propose to use the broader expression of organismic practices to designate every type of localized standardized functioning of the organism that recruits several dimensions. A practice is a habitual way of accomplishing a task, which may automatically recruit habitual modes of functioning situated in a variety of organismic dimensions. It can, for example, associate a sensorimotor habitual schema with a habitual set of representations and habitual verbal expressions. From the point of view of a person’s awareness, a gesture may come to the foreground, while at other moments it is the associated representations that are perceived. In all cases, we are dealing with procedures that can be described. These micro-practices have a limited repertoire that nevertheless sometimes allows subtle modes of adaptation to similar but nonetheless different contexts. Thus, an individual who is accustomed to roasting a chicken may automatically know how to vary the amount of salt and roasting time as a function of the weight of the bird, but the recipe remains the same.

Downing distinguishes the surface of a practice (all the variables of a practice) from the procedural core of a practice that generates these variables.10 A “procedural core” is often established during the first two years of life. It forms the infant’s basic interactional repertoire. Highly idiosyncratic, each child’s procedural core has elements unique to him or her. Later childhood experiences augment and modify the procedural core. Serious body-related trauma, such as physical violence or sexual abuse, can also introduce significant changes in the procedural core. When a psychotherapist aims at a change in a way of doing things, it is mostly the contour of this core that he is trying to identify and change. The reader may have noticed that this formulation implies that a psychotherapist does not focus on a damaging trauma as much as on repairing core modes of functioning. The same can be said of a surgeon who takes care of an organism that has been damaged by a car accident.

For Downing, each practice has a set of aims, intentions, and goals.11 However, these intentions are not necessarily conscious or coordinated together. We find ourselves in a tradition according to which there may be several intentions from heterogeneous sources in the functioning of a way of accomplishing a task.

Let us now focus on what George Downing calls “micro-practices.” When he began to work with researchers on nonverbal communication like Beebe and Tronick, he was fascinated by their capacity to detect short sensorimotor units that seemed to characterize a person’s adaptive procedures. Each one of us has particular ways of smiling, looking at others, or of holding a cup of coffee. As soon as one can specify the contour of a way of doing something at a relatively local level, Downing (2001, 2006) speaks of “micro-practices.”

Vignette of a mother who is feeding her baby while watching television. I have already used the example of a mother who is feeding her baby some food with a spoon while she watches television. The child is sitting beside her on a sofa. While she places the spoon in the baby’s mouth with her left hand, her eyes do not leave the television screen. The film shows us the arrival of the spoon to the baby’s mouth. Her aim is somewhat on target. She first arrives at the lower region of the face, then to the mouth by feeling her way around without ever looking at what is going on. Here we find ourselves manifestly in the domain of habitual behaviors. The baby does not appreciate this and sometimes spits out the food. Annoyed, the mother finally turns toward the baby to solve the problem and then returns to watching television.

This vignette poses the problem of the coordination of sensorimotor schemas in the course of an interaction. It is not possible to feed a baby comfortably unless a greater number of activities are coordinated toward the goal. When a mother adds speech to what she is doing, such coordination is often automatically set in place. The very young child does not understand what is being said when the mother moves the spoon to his mouth and says “here is the spoon,” but he does notice that the voice, the regard, movement of the torso, and movement of the hand all coordinate in such a way as to bring the spoon comfortably into his mouth. To move while talking coordinates the mother and helps her attend to what she is doing with the baby with greater care. Even if she experiences frustration at that moment because she cannot focus on the television, the relationship between herself and her baby becomes more comfortable. It is a history of choices, of priorities not always easy to establish. In this example, the two practices (feeding the infant and looking at television) are conscious conflicting choices.

We notice, in passing, that in this little family scene, the contingency between the behavior of the mother and that of the infant is weak, especially because she dissociates by looking at the television. We find a mother who, in a more subtle way than in other examples that I have given in the sections dedicated to Beebe and Tronick, seems to avoid too many contingencies in her communication to preserve a private zone for herself.

Micro-practices build themselves up in the organism in function of the needs of auto-regulation and interpersonal regulation. An infant will develop a repertoire that manifests itself differently when he interacts with his father, his mother, or both together (Fivaz-Depeursinge and Corboz-Warnery, 1999). His behavioral repertoire also varies in function of the mood of either one of his parents and of his own mood. The dynamics of an individual’s repertoire of micro-practices constitutes his capacity to adapt to his entourage and his drives. I would even say that a practice is a regulatory system between certain propensities and certain social practices.

As an adult, an individual comes to psychotherapy with the know-how that constitutes the dynamics of his organism. Downing’s approach to psychotherapy is centered on that know-how and with its capacity to accommodate as constructively as possible to a variety of social environments. Once a micro-practice has been observed, he reconstructs, with the patient, the history of this practice in the patient’s life and explores different ways of using this practice. The exact mixture of affect, sensorimotor functioning, and representations that characterize this practice gradually establishes itself.12

Having characterized what Downing calls micro-procedures, I will now distinguish between apparently meaningful and apparently meaningless schemas.

Therapists like George Downing and Beatrice Beebe, as well as researchers such as Paul Ekman and Ed Tronick, work on behaviors that have at least one apparent meaning and/or function. Ekman has mostly worked on innate emotional expressions, Tronick looks for gestures that participate in a repair system, and ethologists look for innate forms of communication that regulate rituals such as mating. In the social sciences Kendon (1982, 2004) looks for gestures that frame a conversation and Goffman (1974) for signs that regulate social status. All of the signs are more complex than what can be perceived on photographic or filmed examples, but once they have been detected they are relatively easy to find. These can easily enter in a co-conscious dialogue on the patient’s schemas.13

Having seen various analyses of this kind in several laboratories, George Downing sensed that this type of phenomenon could have immense clinical implications. Inspired by clinicians who were already using this type of observation in psychotherapy, like Beatrice Beebe (Cohen and Beebe, 2002), he decided look for ways of exploiting this type of intervention with the tools he was already using. He coined the term “micro-practices” to designate behavioral and/or bodily phenomena that could be detected with this type of procedure. Once one has acquired a habit of observing these sensorimotor patterns, they can often be found without using coding procedures.

A typical way of beginning a video analysis is to look at a sample at normal speed, so as to know what it is about. Often the therapist already has some information on the context of this sample. He may therefore already find a few interesting patterns, which can then be explored with the following simple techniques:

Once Downing has found ways of detecting clinically relevant micro-practices, he conducts an inquiry on the way the behavior integrates itself into the internal and communicative procedures of the organism. This implies questions on what is experienced by the patient when a practice is activated. Sometimes the patient spontaneously brings forth information, while at other times he is not aware of that behavior, as it was regulated by nonconscious procedures. However, the next time this sensory-schema appears, the therapist can ask the patient what he had experienced at that moment, without even referring to the targeted action. One can also look at a video sample, and ask the patient to associate on what he experiences when he sees himself producing this nonconscious habitual behavior. In doing this work, Downing aims especially at the two subsequent goals I formulate in the language of this book:

A focus on micro-practices allows us to extend how we think about working with the body. We can observe how the activation of a micro-practice interacts with muscular tensions, postural alignment, and the coordination of segments; or we can observe how these global regulation systems and practices interact with each other during this action. We also need to take into account the fact that different body systems may have different time frames. For example, the postural dynamics are slow procedures that frame rapidly changing sensorimotor activity (see chapter 13).

We are just at the beginning of learning how to integrate this type of observation into the psychotherapeutic domain. Behavioral work with so-called “social skills training” has of course always touched upon it, but seldom with such detailed descriptions. If one also analyzes how skills insert themselves in the dynamics of the organism, far more is possible however. The aim remains to find techniques that can help a person to find a wider variety of new modes of activating his body, and of finding more creative ways of interacting with others.

Apparently meaningful practices are the ones that attract a therapist’s attention, yet they are only a small part of the sensorimotor phenomena that are produced by an organism. Studies of nonverbal behavior also code a wide range of sensorimotor habits that have no apparent function. Conscious attribution devices do not know how to handle them. They tend to ignore them. These actions do not correlate with specific contextual features, they do not correlate in a manifest way with inner affects or health issues, they are not a reaction to a specific stimulation, and they do not have a regular rhythm. It would seem that we constantly generate a multitude of behaviors for no apparent reason. One way of thinking about these actions is that they are part of our personal style. We are then close to theories on social identity such as those of Claude Levy-Strauss (1962) and Pierre Bourdieu (1979). Some of these practices may be an imitation of a person we know, or someone that often appears in the media, or may be the exact opposite of a known practice. They seem to be a form of nonverbal punctuation. One can also think of them as an unconscious lapse or a leak from a repressed emotion. Some of the studies on psychopathology (see chapter 20, p. 601f), suggests that this proliferation is apparently random, but that it can be modulated by moods. Affects can accentuate or inhibit them. If one shows a sample of these gestures to someone, they often try to assimilate it to a familiar pattern. For example, a mimic may appear to be a smile, but is in fact just a grimace.

Here is an example of such behaviors, taken from our suicide study (Heller et al., 2001), that George Downing (2001) and Beatrice Beebe (Beebe and Lachmann, 2002, p. 41; Beebe, 2004b) knows well:

Vignette on pre-suicidal behavior. I have already written several times on the study we conducted on the behavior of 23 patients who entered Geneva University Hospital after a suicide attempt (Archinard et al., 2000, and Heller et al., 2001). Their facial behavior was analyzed in its Laboratory of Affect and Communication (LAC) by Véronique Haynal-Reymond, Michael Heller, Christine Lessko, and other collaborators. We coded samples of their behavior using Ekman and Friesen’s Facial Action Coding System. We were looking for facial behaviors that could allow us to predict which patients would probably not make a suicide attempt (attempters), and which ones would make another suicide attempt (reattempters) in a two-year follow-up. Once we had coded their behavior, we asked the computer to look for actions that correlated particularly well with the known reattempters. We also compared their behavior with depressive patients with no suicidal risk that we had coded in a previous unpublished study. The correlations that came out drew our attention to a series of mimics none of us had really noticed: oral activity displayed when the subject was not speaking.

Oral activity occurs (a) every time one of the muscles that move the lips without moving the cheeks is activated and (b) when this activation cannot be explained by speech activity. This behavior is displayed 9% of the time on average by patients and the psychiatrist who interviews them. One can therefore not always associate oral activation with suicide reattempt risk. Oral activity groups a wide variety of lip configurations, some of which seemed characteristic of an individual. Some of us could have the impression that an oral activity had a meaningful (e.g., despair or contempt) and relevant function, but then not all the members of our team would attribute the same meaning and/or function to this motor event; at other times, we could not attribute the slightest meaning to these movements. Most of the time these lip movements seemed to appear randomly, in function of inner impulses, or to modulate the general atmosphere of the interview.

Reattempter patients had a systematic tendency to display more oral activation than attempters did, however the interviewer displayed more oral activity than the patients did.

After this finding we looked around us, and saw that some people displayed a lot of oral activity (e.g., President Clinton), while others did not use that type of movement in their current life. For those who did, their mimics where often more intense than those of our patients. We therefore arrived at the conclusion that most of these patients where (a) part of the population that uses oral activity, and (b) that they tried to inhibit that activity. We also observed the same type of oral activity on films of anorexic patients, who often have suicidal intentions.

We have been particularly careful to check with the medical team that medication could not explain this oral activity (e.g., in this hospital service, for such cases, all psychiatric medication was temporarily stopped). The discriminative power of oral activity varied in function of times and circumstances but was often efficient for more than 80% of the patients. The frequency of this activity was particularly strong among reattempters so we could think that certain factors can modulate these patterns, without being their cause. The literature on conversation rules is extensive (Feyereisen and De Lannoy, 1991, pp. 15–20). Nevertheless, high rates of facial mobility when listening remains uncommon (Ellgring, 1990, pp. 390–391) and could have a strong impact on the speaker (Cosnier, 1988). For the moment, the best explanation we may come up with on the function of these lip movements is that they could be representative of an ostentatious way of regulating disagreeable feelings. This implies two steps:

1. Patient feels a blend of strong feelings such as sadness (or even despair), anger, or contempt.

2. Patient needs to keep these feelings under control so as not to interrupt the interview by an outburst.

Patients explicitly communicate that they are making a considerable effort to self-regulate such feelings. Both doctor and patients mostly displayed low intensities of oral activation which often barely reach Ekman and Friesen’s minimum requirements. This type of behavior could be a universal way of “ostentatious self-regulation.” The doctor’s behavior changed as a function of the patient’s suicide reattempt risk, but we do not know if his nonconscious reactions were guided by these behaviors or other displays that we did not code (see chapter 20, p. 531).

If this type of observation is replicated, then research might show that these apparently meaningless actions are modulated by factors that may have a strong clinical relevance.

To recapitulate: in the history of psychology reviewed in this book, I have distinguished four types of behaviors, all of which have their simple and more complex versions:

When the noninitiate listens to a Mahler symphony, he will probably focus on the melody and the rhythm. The enlightened amateur will also pay attention to all the instruments that play no melody, that do not support the rhythm, but that are like colored dots that create the texture and the atmosphere of the symphony. These apparently useless instruments are a bit like the movements I have just been talking about. We do not know if they have a function, but they do modulate the atmosphere experienced and conveyed by a person. Their action is often quasi-continuous and highly variable. This new type of data brings us back to the observations that motivated Darwin to write a book on emotional expressions that are purposeless (chapter 7, p. 172). Except that we now have more refined observations that bring us beyond the notion of expression. The apparently random motor activity seems to follow a dynamic pattern close to what has been observed on genes and the immune system. I am not assuming that genes regulate the creativity of psychological and behavioral schema, but that each dimension has its particular form of spontaneous creativity. This is a topic that has not yet been explored. It makes us aware of a form of spontaneous creativity of sounds, gestures, and impressions that seem to proliferate and which sometimes survive. For example, if used by a famous actor, a repetitive behavior may be imitated by millions. The underlying mechanisms of these dynamics are close to how genes create mutations. Human organisms seem to have a tendency to spontaneously invent new ways of thinking, moving, feeling, and interacting. Some of these proliferations may enhance the capacity of an organism to survive in a given environment, while in other cases they may reduce the capacity to survive. When a psychotherapist tries to evaluate the adaptive potential of a patient, he may need to evaluate the impact of these apparently meaningless repetitive activities.

I tried following Tolstoy’s advice at one time, and forbade myself to make the sign of the cross. But I can’t help it, my hand moves automatically. To not sign myself while praying is like leaving the prayer incomplete. (Alexander Solzhenitsyn, 1984, November 1916, V, p. 44)

The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty is one of the few Western thinkers to claim that our understanding of the world is founded on the body’s perception of its surroundings and situations. (Thea Rytz, 2009, Centered and connected, p. 20)

In addition to the analyses in the studies of nonverbal communication, it is also useful to introduce into our discussion on micro-practices the analysis of habitual movements by French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961).15 He situates the habitual movements somewhere between a reflex and a conscious behavior: “We have to convey the concepts necessary to convey the fact that the bodily space can be given to me in an intention to hold without being given in an intention to know” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945, 1.3, p. 90). Most acquired habits are at first constructed with the support of conscious procedures.16 Once they have found a relatively satisfactory mode of functioning, they can be activated in more or less nonconscious ways by relatively local organismic systems. A habitual movement has a mobilizing goal (like turning a door handle) for certain bodily and mental activities that lead to a “relaxation” or a deactivation once the intention contained in this behavioral habit is extinguished. A habit is a coherent system, but not an isolated one. Its characteristics are what attracts the attention of the subject or of an observer, while the way it inserts itself in the organism remains in the background of what they perceive. “If I stand in front of my desk and lean on it with both hands, only my hands are stressed and the whole of my body trails behind them like the tail of a comet” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945, 1.3, p. 87). Even a reflex inscribes itself in a bodily and mental ecology. There is no purely habitual bodily gesture, as there is no purely mental habitual thought.17 The connections between a local action and the rest of the organism are partially preconscious, and mostly nonconscious.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty avoids invoking global structures like the organism or the individual system. He admits, nonetheless, that the individual is constituted by distinct dimensions in interaction: “We cannot relate certain movements to bodily mechanism and others to consciousness. The body and consciousness are not mutually limiting. They can only be parallel” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945,1.3, p. 108). From the point of view of consciousness, a gesture is like the visible part of an iceberg. It is a part of an intentional network that coordinates thoughts, nervous networks, muscles, skeleton, respiration, the cardiovascular system, as well as postural support. A specific action can mobilize this network in different ways, generating a variety of motor projects and motor intentionality that guides fine sensory-motor actions. Different actions, such as picking up an object or pointing it out, will mobilize different organismic coordinations.18

The chapter by Merleau-Ponty I refer to is built around cases described by neurologist Kurt Goldstein,19 who introduced the notion of organism in the philosophy of the 1930s. These cases interest Merleau-Ponty because they show that mental disorders are not distinct from physical problems, even in the case of a serious neurological disturbance. There are some necessary ramifications with the way they insert themselves into their organismic ecology.20 On the other hand, Merleau-Ponty distances himself from the holistic thinking associated with Gestalt psychology that Goldstein proposed when he speaks about the organism.

I will now use a set of observations to illustrate how the analysis of a micro-practice can be integrated in classical body psychotherapy. To scan facial micro-practices, I often use Ekman and Friesen’s Facial Action Coding System (FACS), which I have already presented (see chapter 20, p. 584f). Downing’s approach to the analysis of clinical videos has also been influenced by FACS.

Knowing how to work with such methods is an excellent way to learn how to detect micro-practices. Let us now take a concrete example. FACS uses numbers that designate a unit of motor activity, and letters that indicate the intensity of the activation (A = subliminal intensity, D = maximum intensity). I detail this work by using, as an example, the expression 6C + 10C + 12C + 24C:

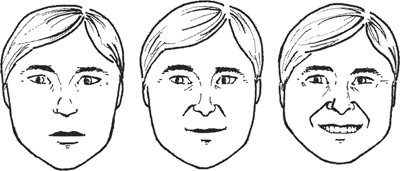

Rainer Krause and his team analyzed the interactions between a psychoanalyst (Krause) and a patient.21 It consisted of filmed sessions of psychodynamic psychotherapy in a face-to-face setting. In examining these films, Krause’s team noticed that some of the patient’s smiles automatically unleash a reciprocal smile on the part of the therapist; whereas in the face of other smiles, the therapist’s expression remains impassive. This is a good example of an interactive micro-practice, to the extent that neither the therapist, however well trained in FACS, nor the patient are conscious of this. In a more detailed analysis of the films, Krause and his colleagues discovered that the (6 + 12) smiles that do not activate a similar behavior in the therapist are in fact (6 + 10 + 12) smiles (see figure 22.1). Following the recommendations of Ekman and Friesen, they interpret this expression as a smile that masks contempt. In the specialized language of psychoanalysis, there would be a negative transference masked by an apparent positive transference. Krause’s analysis of the patient, in exploring the patient’s associations, confirms the existence of a disguised negative transference.

FIGURE 22.1. An example of faces coded with FACS system developed by Ekman and Friesen (1978): neutral face (left), face with unit 10 (lifting of the upper lip) and an added mobilization of the unit 06 (crow’s feet at the corners of the eyes) (middle), and unit 12 (smile) (right).

In this example, the therapist’s nonconscious processes differentiated between two smiles and triggered a differentiated sensorimotor response. However, neither the difference of smiles nor the correlated responses were perceived conscious processes. All that Krause probably detected is that there was something fishy between him and his patient. Only a coding procedure could have detected these rapid and apparently unconnected events. However, after this observation, Krause was able to pinpoint the masked negative transference of the patient, using classical psychodynamic methods, close to Reich’s Character analysis.

Having used FACS for more than a decade, I have learned to recognize some of these patterns without using cameras. I may not be able to detect how my behavior correlates with that of the patients, but I can at least detect phenomena like masked aggression. When patients repetitively used well-defined facial expressions, I looked for ways of integrating this observation with other methods used in psychotherapy. In an initiative similar to that of Krause, the smile cannot be simply presented to the patient. If he is not conscious of his negative transference, there is the risk that he will be wounded and offended by a therapist who attributes feeling to him that he considers shameful and of which he is not aware. If the patient is conscious of his contempt, he risks poorly integrating the “magic” that allows the therapist to “read his thoughts.” These difficulties are so real that after a few attempts, I was on the verge of abandoning the possibility of using this type of interpretation in psychotherapy. Discussions with George Downing encouraged me to persevere:

Here is an example.

Vignette concerning a young man with a complex smile. A young man has, from the very first session, a complex smile that is often22 made of the aforementioned configuration (6C + 10C + 12C + 24C + 26B23). After a few months of psychotherapy, we finally get to talk about the fact that the patient is easily self-critical, but he refuses to admit that he might have negative feeling toward those to whom he is close (colleagues, spouse, parents, etc.). With this theme well under way, I finally ask him to explore his smile. During an entire session, I suggest that he take his time to feel what is happening when he lifts his upper lip (AU10); he reports that he feels like a dog that bares his teeth and despises his enemy. I then suggest that he explore what happens when he adds flattening his lips at the same time (AU24) after having opened his jaw (AU26). He feels something that curbs his contempt. I then suggest that he add a smile to this construction, and he suddenly becomes aware that it is close to his habitual smiles. Even at this slow pace, this experience is difficult for him to digest. He is grateful that I have allowed him to become aware of this side of himself that sometimes looks down at his wife, but he is shocked to discover (a) his contempt and (b) that his wife can perceive this. I do not use this technique in the following sessions. Instead, we talk about what he had felt when we explored the details of his smile. An important material emerges that the patient integrates by verbalizing what he feels. Four sessions later, I suggest that he lie down on the mattress and feel in his body what is happening within. He talks again about his smile and his contempt; I do not work on his mimics. I ask him to just feel what is going on inside and localize what these feelings activate in his body. He begins to describe a ball of anxiety that he often feels in his belly, and about which he speaks to no one, not even me, his therapist. He feels his torso taking the shape of a C, with the thorax and the abdomen nearing the spinal column, while throat and pelvis rise upward. He feels the urge to curl up around this ball of anxiety, which he experiences in his belly.

I wait a minute and notice that he does not turn on to his side to roll up around his pain, as many people do in this case. He stays on his back. Given that the C position is difficult to maintain for a long time, the back relaxes an instant by stretching out and then again takes up the C position. Having taken up this position several times, the movement becomes rhythmic. For a person trained in the Reichian methods, two directions present themselves to the therapist:

1. The patient needs to go toward this pain slowly.

2. The patient is about to be mobilized by what Reich calls the orgastic reflex, and is oriented toward the anxiety of experiencing too much pleasure.

In both instances, the therapist accompanies and observes, but he has internal questions that keep him curious. As it happens, the work opened up on his fear of love, the fear of losing his identity if he really allows himself to love his wife, body and soul.

This is an example of how a body psychotherapist can begin with a relatively local sensorimotor schema, proceed to explore how it inserts itself into systems of regulation and the dimensions of the organism, which then leads to classic themes for most psychotherapeutic approaches.

It is mostly the nonconscious mechanisms that structure the body’s micro-practices. They are often activated outside of conscious thoughts without any awareness on the part of conscious thoughts. Even when a conscious motive expects the appearance of a sensory-motor schema, the mind cannot become aware of how these thoughts managed to activate the relevant habitual behavior. The patient may have to learn how to become conscious of his bodily practices, and accept that he cannot always understand them. Downing gives the following example from the research of psychologist T. G. R. Bower (1978).

Vignette on a motor evaluation and a conscious evaluation. Bower gives a child a typical Piagetian test. He presents a clay cylinder to the child. The child takes the cylinder in his hands. Then, in front of the child, Bower transforms the cylinder into a ball and asks the child if the ball weights more than the cylinder. The child answers that it is heavier. Bower hands him the ball.

Bower filmed this interaction. On the film, he notices that the child takes the ball in the same manner that he took the cylinder, as if the spontaneous muscular preparation of the arm expected an identical weight.

Adam Kendon (2004, p. 81) develops this analysis when he quotes research studies that show that the motor responses of a child who tries to solve a problem, such as those presented by a Piagetian test, seem to envision other strategies than those the child describes verbally. Thus, in observing the options initiated by the gestures, an individual is able to discover other strategies than those that he imagines at the level of the thoughts that can be verbally expressed. (Emmorey and Casey, 2001; Goldin-Meadow, 2003). This research trend confirms the hypothesis that I have previously formulated in other sections, according to which thinking while moving or thinking while talking does not necessarily generate the same strategies.

The notion of automatic preparation of an action has its importance. The organism that initiates a propensity automatically mobilizes the physiological, vegetative, sensorimotor, and affective necessary support. Someone who is going to run experiences a rise of sympathetic activation that increases respiration and the irrigation of the peripheral arteries. This implies evaluating which resources to mobilize and activating what Merleau-Ponty calls a motor project. In this sense, psychologists analyze gestures and physiology to evaluate what an organism expects. It then becomes possible to distinguish an automatically activated dimension (getting the arm ready), that Downing simply identifies as bodily, and a conceptual dimension that is animated by different processes (the verbal response of the child). Such a distinction between bodily and conceptual reactions is often pedagogically useful. It highlights the assumption that our organism follows at least two ways of treating information, which follow different algorithms. Each mode has its strong point and its limits. For example, consciousness can only be aware of conscious perceptions. Therefore, it cannot perceive the motoric evaluations of reality and the way they sometimes contradict what is thought.24 However, a person can learn to develop an intuitive sense of what his nonconscious processes are trying to achieve.

When Downing draws the patient’s attention to a small gesture that has many implications, the expression “body micro-practices” immediately speaks for itself. The fact that the reaction is of the body, not of the mind, indicates very well the impression that this type of gesture regulates itself independently from what is thought. The patient may feel relieved to learn that this is a “normal” mode of functioning. The therapist may then co-construct a therapeutic alliance with the patient that permits a better perception and identification of the underlying stakes involved in a habit. Both individuals consciously explore what can be learned concerning a shameful or overvalued practice and what can be done about it. I have often noticed that in this type of work, the patient is afraid the therapist will reproach him for having made a gesture of which he is not aware. The patient concludes that he “ought” to have been conscious of it. It is important not to transform this type of intervention into a way to torture the narcissism of the patient. The spirit in which this type of analysis is carried out is consequently very important. It demands immense tact and sometimes a form of constructive humor.

No one, to my knowledge, has determined the nature of powers of the affects, nor what, on the other hand, the mind can do to moderate them. . . . The affects . . . of hate, anger, envy, and the like, considered in themselves, follow with the same necessity and force of Nature as the other singular things. And therefore they acknowledge certain causes, through which they are understood, and have certain properties, as worthy of our knowledge as the properties of any other thing, by the mere contemplation of which we are pleased. (Spinoza, 1677a, Ethics, III, Preface, II.l, p. 69)

Whenever we have an emotion our bodily experiences instantly becomes more complex. (Downing, 2000, “Emotion theory reconsidered,” p. 255)

According to Downing,25 an emotion is activated every time an ongoing habitual mode of functioning needs to be questioned.26 The eruption of an emotion imposes a red light on the current habits. Putting the psyche in a crisis is a way to demand that the mind takes the time to explicitly question the usefulness of what it is about to do. For example, a sudden fear can make me look all around. I could then notice that an animal, detected by nonconscious mechanisms, is roaming in the forest in which I was walking. Furthermore, the emotion already prepares the organism to react by increasing the activation of certain resources that could be needed. In other words, the irruption of an emotion into consciousness obliges the organism to question itself, to try to see if there is—in self or around self—a change that demands a priority accommodation. The emotion also intensifies the collaboration between psychological and physiological mechanisms that it may need to mobilize.27 Muscles and thoughts are turned away from their current path: “In sum, a paradigm unit of emotion is an extended, complex act. It is simultaneously a bodily sensing; an aligning of the sensing with the relevant situation; and a formation of cognitions” (Downing, 2000, p. 259). This model is used to describe relatively brief emotional reactions (most of the time for only a few minutes), like Paul Ekman’s emotional expressions model, which we have already discussed (chapter 9, p. 260f).

The function of the emotions is difficult to determine. Emotions and defenses mobilize independently of what is being thought, on the intimate level as well as on that of an interaction. It often happens that an emotion manifests itself and the individual is unable to relate it to an event. An emotion may arise when it is expected, like at the occasion of the death of a friend, but it may also not manifest itself at such moments, then later surface unexpectedly without any apparent connection with what is happening in the moment. In working on the way that an individual’s thoughts and behaviors relate to his affective dynamics, it becomes possible to set about to question the way he functions.

It is sometimes only a few months after a series of interventions that the patient and the therapist are able to notice the changes that emerge into the life of the patient and into the therapeutic relationship. The psychotherapist guides these profound modifications by watching over the frame within which these new calibrations are being established, but the nonconscious readjustments that appear during the therapeutic process is not something that he controls. He only knows, by experience, that this type of process may often be set in place when particular conditions are met. For example, instead of fearing his emotions, a person begins to approach them with thoughtful curiosity, like a source of information that is useful but difficult to understand explicitly. They are then no longer perceived as mere manifestations of the archaic animal in us. They also become an alert system that informs consciousness28 that it should mobilize regulatory mechanisms that are not being activated by the current habitual behavioral process. It is not a question of presupposing, in this model, that the emotions are right more often than the thoughts, but of proposing that different dimensions of the organism can produce different options on how to react in a given situation. The difficulty is to be able to sense what options, or which combination of options, are the most useful in the here and now.

These considerations bring us back to the notion that the affects are strongly influenced by the nonconscious mobilizations that influence behavior and the cognitive dimension without consciousness being able to directly influence this mobilization. We also find this hypothesis in philosophy (Elster, 1999), in some theories on anxiety disorders (Beck and Emery, 1985, p. 188), and in a large part of the literature on trauma, summarized for body psychotherapists by Peter Levine (2004) and Babette Rothschild (2000). These influences are not reciprocal but asymmetrical. The influence exercised by the body or the metabolism on the thoughts are not the same kind as those exercised by the thoughts on the rest of the organism.

The preceding discussions bring us to the following list of different way of integrating the analysis of movement in psychotherapy:

The approaches of Aalberse, Downing, as well as the options I defend in this book integrate all of these possibilities, whereas neo-Reichian body psychotherapy is mostly interested in options 3 and 5. A process that focuses on some of these strategies may have more focused aims and efficiencies, while integrative approaches cover more ground and are more flexible. We already had a similar discussion when I distinguished between a body psychotherapist that works with the body and the mind of the patient (e.g., Lowen and Levine), and a body psychotherapy team in which a body therapist works with the patient’s body and a psychotherapist with his representations (e.g., Bülow-Hansen and Braatøy). The more focused work supports more expertise on certain aspects of a person, while the broader approach may have more expertise on the connection between dimensions. We can now distinguish three types of body psychotherapy:

George Downing’s approach is an example of a psychotherapeutic approach of organismic dynamics. The therapist is aware that the mind is a dimension of an organism that interacts with others. However, his key target is the realm of representations. Most humans have the impression that it is something like a core conscious self, or a central me (see chapter 14, p. 362), that initiates what we do and how we perceive or world. This is probably one of the necessary illusions, as I do not think that a person can have an adequate mastery of his actions without having the impression that such a central me exists. Video-analysis shows that most of our actions are activated without the permission of that core conscious self. In some cases our actions and our views are so damaging for our survival that this core conscious self feels disempowered by nonconscious dynamics. I have seen or read about psychiatric patients who cannot prevent themselves from acting in ways that are harmful to others and who are shocked by what they do. This type of dissociation is well known by judges when they ask for a psychiatric expertise to evaluate the responsibility of a person. The patients I am thinking of begged to be maintained in prison or to receive surgical interventions on their brain to prevent them from behaving as they do. These are extreme cases, but for most of us there is a need for a simplistic vision which works on the assumption that from the point of view of our consciousness there are events which we can influence and others that proliferate without our knowing how. With tools such as video-analysis we can acquire a better picture of this behavioral proliferation, while the technique of free associations allows us to grasp the spontaneous creativity of our mind. By combining such methods, the subject can be helped to forge for himself a vision of who he is and how others react to his mode of functioning. New ways of evaluating what is happening may help the subject to feel less disempowered by the spontaneous creativity of his organism. I am less optimistic than George Downing, as I do not think that we can change old mental and body habits that have had years to put themselves in place since the first years of one’s life. But we can modify the ecology of these habits. We can try to live in a more constructive environment, to discover new forms of habitual behaviors and representations. When these become a reality, a patient may discover that with the help of others his core conscious self is less disempowered than he thought. I cannot change the world and my history, but I can initiate new ways of reacting to what is happening. These new mental and behavioral habits change the ecology of old habits. If the old habits have lost the support of that part of us that has the impression of being who one is, they become less powerful, they lose their intensity, and they come less often to the front of the stage. These changes need years before they become well integrated in a global organismic system. In the chapters on evolution I pointed out that changes have unforeseeable implications and ramifications. Those need time to calibrate, because millions of organismic procedures must also calibrate with these new schemas before they can find a comfortable place in the dynamics of the organism. However, in most cases this calibration can continue after psychotherapy has supported important and relevant initial changes, if the patient has enough courage and the support of a constructive social environment. I often warn my patients that they will need to construct, through trial and error, these new forms of functioning. This type of implementation rarely works at the beginning. Success requires small steps and perseverance. Some particularly fragile persons may need a lifelong support, but even in these cases this does not mean that psychotherapists should be consulted all the time. Slices of psychotherapy are often enough. In such cases, the support of social workers and institutions is at least as important as the support of a psychotherapist.

Here is a domain which cries out for new forms of systematic therapeutic attention. Persons familiar with the body psychotherapy tradition would seem especially well positioned to develop new contributions in this respect.