Finding the Next Tailwind to Ride

The ideal long-term buy-and-pretty-much-forget investment is a company practicing all the five clues that is also being pushed by a tailwind.

Finding that combination is not easy.

But it can be done, even if you are not able to travel around the world to investigate all (or even some) of the various opportunities and possibilities in person.

Remember, in the markets what everybody knows is of little or no value. Big profits are rarely made by following the crowd. Investors who do their own research and discover what nobody else knows are the ones who clean up.

So when you come across an opportunity that nobody else knows about, follow in the footsteps of the world’s most successful investors: keep your mouth shut and buy.

Now, let’s investigate the possibilities in three niches that (with the exception of the first) I, personally, have little or no experience of. I trust these examples will inspire you to undertake your own investigations.

Those three areas are:

• Education. The world’s most heavily regulated industry. A space ripe not just for disruption, which is beginning (at the edges), but for a total revolution. Is it possible to come up with a profitable business idea that could spark the deregulation of education—around the world?

• Tea. Second only to water in popularity. A space that has (at the moment) no equivalent of Starbucks or McDonald’s.

• “Fast casual.” A recent almost-fast-food trend, originating in the United States. And within that category, specifically Mexican fast casual, led by the fast-growing American chain Chipotle.

Education vs. Learning

Major tailwinds can arise through the disruption of heavily regulated industries. As proven by Uber, which upended the taxi business; Skype, which decimated the world’s phone monopolies’ high-priced international and long-distance call revenues; and e-mail, which has all but destroyed post offices’ first-class and junk-mail business.*

None of these competitors were licensed to compete against the government-regulated or government-owned monopolies.

By the time the regulators woke up to what was happening, it was too late.

In every country, education is the most heavily regulated industry of all.

Is there a similar opportunity in the education space?

To find out, let’s unpack education, as it is today, into its various subcomponents. Then we’ll be able to see if we can discover a disruptive opportunity. One that can also generate a profitable, Uber-style business model.

Why We Went to School

As children, we didn’t really have much say in the matter.

But after an initial period of disorientation—the anxiety that can come from being separated from our mother and father for the first time—most of us looked forward to going to school every day.

If not school itself, seeing our friends.

We also became proud of our accomplishments†—but discouraged when we received low marks or failed a subject.

Nevertheless, school and college have become modern coming-of-age rituals, final graduation being proof of the completed transition from childhood to adulthood.

Whatever our experience while at school, we were there for reasons that were not only out of our control, but mostly out of our parents’ control as well:

• It’s compulsory in almost every country. So our parents didn’t have much say in the matter, either.

• To learn. Our parents probably chose the best school they could afford on the expectation that we would learn more and learn it better.

• Certification. The progression from primary school to high school to university or college results in a series of certificates that most people believe enable us to be more financially successful adults.

• Child minding. For some parents, having their children looked after for most of the day is a great boon. Enabling both parents to have an income.

• Indoctrination. It’s natural to want to pass our beliefs on to our children. So many of us select a school for our children that reflects our religious or secular beliefs. In some countries, the government curriculum mandates various courses aimed to foster certain beliefs and traits such as national pride, good citizenship, and/or other values the politicians or the education bureaucracy deem to be essential. Or beneficial (usually to them rather than the kids).

• Because everybody else does. Few parents try to create a different learning environment for their children to that offered by schools. Or even consider the possibility. Even in the United States, which has the loosest regulatory environment of any country, only 4 percent of children are homeschooled.

Most people equate education with learning. But as you can see from this list so far, learning may not be the primary goal of education.

To see why this could be the case, let’s consider two periods of everybody’s life: before school, and after school or university.

Every Child Is a “Learning Machine”

What do you think are the two most powerful and enduring learning experiences of your life?

These are two skills you learned entirely on your own.

They are two activities you engage in every day.

Let me put the question another way: Who taught you to walk and to talk?

Sure, you may have had a little bit of help. But basically—unless you had a genuine learning disability such as being crippled or mute—your only teacher was yourself.

Every child is born insatiably curious.

Aside from wanting to walk and talk like everybody else, children also want to know why about everything.

They ask “Why?” so often it eventually drives most adults crazy.

Then they go to school. Where, unless a particular subject interests them, or they’re lucky enough to have an inspiring teacher, they zone out.

Meanwhile, out of school they continue to learn all sorts of interesting (to them) other noncertificate stuff. From shooting hoops to programming Dad’s computer.

Education, Learning, and the Real World

When we “graduate” into the real world, we revert to our preschool method of learning. Learning something because we want to or need to.

A friend of mine—let’s call him George—graduated from university with a degree in economics. He landed a job at BHP, the big Australian mining company. As part of his job, George had to learn about metallurgy. Hardly surprising given the nature of his employer.

Eighteen months later, his boss commented that George knew more about metallurgy than anyone he knew with a degree in that subject.

On-the-job training. Nothing surprising about that. Except that George had acquired more metallurgical knowledge than a university graduate in that subject, in half the time—all while doing his job, as well.

And his economics degree?

Never used it.

Your experience may not be as extreme. But, like George (and me), you spent twelve to sixteen or even eighteen years of your life at school and university “learning” stuff.

• How much of what you were taught do you use today?

• How much of what you were taught did you have to unlearn when you entered the real world?

I have yet to ask someone those questions and receive “everything” and “nothing” in reply.

This is true even for graduates with professional degrees in such fields as medicine, law, finance, and teaching, where you’d expect the program to be highly targeted.

A teacher told me she had to unlearn everything she’d been taught about how to handle students in the classroom after she’d graduated into the real world. While a finance graduate, who today is a successful investor, said the only things he brought from college into the real world were the accounting basics needed to analyze company balance sheets and profit-and-loss statements.

All I retain today from my eleven years in primary and high school are reading, writing, and arithmetic. Plus some higher math that I use occasionally.

I passed French—but I can’t speak it, though I can read it (if it’s simple enough). Even on my occasional visits to France, this poorly mastered skill has been of little use to me.

Years of wasted time.

I have a university degree in economics—but when I got into the real world, I had to unlearn almost everything I had been taught.

Looking back, I realize the only truly useful skill I acquired at university was the ability to do effective research in the library and elsewhere.

I also became pretty good at billiards.

Far more significant than anything else: as editor of the student paper I was introduced to the publishing business, where I’ve been ever since.

This extracurricular learning experience was my greatest takeaway from all the years I spent at university.

But I’ve yet to receive a piece of paper “qualifying” me in this field! (Unless you count all that green stuff.)

Use It or Lose It

The ultimate test of whether you’ve had a real learning experience is whether you use it.

Because if you don’t use it, you lose it.

Once upon a time, I could solve complicated mathematical problems in my head. Quickly.

Today I can’t.

I’ve been using calculators and spreadsheets for so long, that ability has disappeared from lack of use.

Sure, we didn’t spend all those years sitting in class and learn nothing.

Obviously we absorbed enough to pass our final exams and get that all-important graduation certificate.

But how much did we retain?

One of my high school classmates defined “education” succinctly:

“All year you cram your head full of stuff—and then spew it out over the exam paper. And it’s gone.”

Studying for exams isn’t called cramming without good reason.

So most of what we “learned” in school and college we used to pass the certification exam—and we then promptly began to forget it.

When judged by what is useful in the real world, education is clearly a highly inefficient industry. Perhaps the most inefficient industry on earth.

An industry ripe for disruption.

The Regulatory Environment

Education as we know it is a product of the regulatory environment.

This environment is based on two misconceptions:

1. To learn something, you need to go to school.

2. To be certified, you need to go to school.

Here we have the springboard for the disruptive business opportunity we’re looking for.

Decoupling Certification from Education

The key first step to an “education revolution” is, I believe, to decouple certification from education.

To do that successfully (and profitably) it’s best to focus on the certificate that is most universally desired, and the most portable worldwide: the high school diploma.

Can you get a high school graduation certificate without going to school?

In the United States, the answer is yes.

In most other countries, the answer is no.

Graduation certificates come in two “flavors”:

• Passing an exam (or series of exams).

• Passing exams, plus a variety of other requirements depending on the jurisdiction.

In certain states of the United States, passing an exam plus having someone (whether a parent, a teacher, or a school) certify that you have spent a certain number of hours studying the subject are all that is necessary to gain a high school graduation certificate.

A certificate that will be recognized as a college-entry ticket in almost every other country of the world.

By contrast, many other countries have a host of additional requirements. From the general (certain subjects must be taught to a specified standard) to the rigid (it’s 10:00 a.m. on a Thursday and you’re nine years old so it’s math).

The fundamental similarity is that in addition to passing the exit exam, you must have proof that you sat in a classroom for the previous twelve-odd years.

The SAT Model

In most countries, the ticket to university is a high school graduation certificate.

But not in the United States. The only exam you need to pass is the SAT.

Anyone can take this exam, from anywhere in the world. The only qualification required: the ability to pay the necessary fee.

That’s it.

If we apply the SAT model to high school, we can decouple certification from education.

Here’s how:

1. Go jurisdiction shopping. Set up shop in the country, state, province, or city that has the fewest government edicts specifying what you can’t do.

In the education space, the freest jurisdiction is probably an American state in the New England region.

2. Duplicate the SAT model by creating a series of exams that qualify for the high school graduation certificate in that jurisdiction. Or even simpler: team up with an existing high school.

3. Offer those exams worldwide. Online would be ideal, but cheating is an inevitable problem.

And it’s crucial that everything be kosher. To avoid gaining a reputation as a “degree mill,” it would be essential to offer physical exams all over the world.

This may sound like a logistical nightmare—but that’s exactly how the SAT works. The logistical trail has already been blazed.

There are two simple ways to duplicate the SAT model:

1. Hire the Educational Testing Service to hold the exams. The ETS is in the business of creating and holding exams around the world for, among others, the College Board, the creator of the SAT.

2. A little more difficult but not impossible: find out where the ETS holds its exams and make an arrangement with the local suppliers.

Where’s the Market Potential?

It’s fourfold.

1. In the United States:

Students, such as homeschoolers, who would like to have an official graduation certificate. And students in the more highly regulated states who wish to accelerate their graduation from high school.

While not necessary to attend college in the United States, a certificate may be an advantage for a student who intends to study abroad.

In other words, the primary market is not the United States. It’s the rest of the world.

2. Foreign students who want to study in the United States (or other Western countries):

The American credential is recognized everywhere. The same cannot be said of high school graduation certificates offered in many third-world countries.

3. Foreign (and American) students who want to circumvent local schooling requirements:

Any third-, fourth-, or fifth-grade student who is able to pass the American exam may be able to accelerate his or her graduation from school to college by a year or more.

For example, most Philippine colleges have three entry requirements: an admission exam, an aptitude test related to the specific course being applied for, and an interview.

The foreign credential gives what’s called “a backdoor entry”: you can skip the admission exam entirely.

On the same basis, there’ll be a demand within the United States from high school students who wish to get out of school early.

4. Foreign private schools:

Initially, the largest and the most accessible market will probably be private schools outside the United States that would like to enhance their local market potential.

Any school that can offer an internationally recognized diploma in addition to the local one, at a modest additional cost, will have a great marketing advantage over its competitors.

International schools that teach the American, British, or other curriculums can now be found in just about every major city. Initially started to cater to the children of expatriates, today they are filled with local students whose parents pay up to five times the price of the best local private schools.

The demand for such internationally recognized certificates is there.

So if just one school in a country decides to offer the American credential, the result should be a snowball effect, as its competitors realize they have to follow suit—or lose their customers.

To maximize the impact—and revenues—one additional feature must be added: practice exams, and online courses so students can bone up on subjects they may not have covered in their local school.

Such practice exams are a part of the SAT model that should be duplicated.

Offering instruction is not as difficult as it might seem. Hundreds of sites catering to American homeschoolers are equally available to anyone with an Internet connection. A directory of such sites—combined with resources from TED Talks, the Khan Academy, and dozens of similar sources can, between them, provide a student with most everything he or she needs to fully prepare for a high school exam on just about any subject.

And if not, online tutoring, via the model of freelancer.com, 99designs.com, and dozens of similar sites that put suppliers and customers together, could be an additional source of revenue.

Testing the Market

My sense when I came up with this idea was that a big market exists for this product.

Market testing bore out this assumption.

And College…?

One of the first questions that came up during our market testing was, could I get an American college degree the same way—by just taking the exams?

Why not!

This is a more complicated option since, comparatively, the requirements for high school diplomas are fairly standardized. While college courses and the subsequent degrees come in hundreds of flavors.

Before we’ve even started, we already have a possible brand extension!

We asked a series of parents with children in private schools, “How much extra would you be willing to pay for your sons and daughters to gain an American high school graduation in addition to the local certification?”

The answers ranged from “a thousand dollars” to “up to two thousand dollars.”

We also asked parents if they’d be willing to pay a price similar to the cost of taking the SAT to have their kid sit for the exam. Working parents (middle- to lower-middle-class, earning around $400 per month) universally answered, “Yes!”

We even had local college graduates who overheard the question butting in to ask if they could do it, too. (Why? An American high school certificate can have greater credence abroad than a local college degree!)

The principals of the private high schools we talked to all thought it was a great idea “depending on price.” The main attraction: “It would add to our school’s reputation if we could offer such an internationally recognized credential.”

As it happens, this model already exists.

The General Educational Development Test (GED)

The GED was developed during World War II by the American Council on Education to enable military personnel who hadn’t graduated from high school to pursue tertiary education after the end of the war.

From this beginning, the GED—a high school equivalency diploma—became available across the United States and Canada as an option for people who had not finished high school.

As a result, it gained the reputation of being “for dropouts.” Actually totally unfair, given the wide variability in the quality of American high schools. And thus their graduation diplomas.

Regardless, the GED is recognized by virtually all employers, colleges, and universities not just in the United States and Canada, but worldwide.

In 2011, GED’s parent, the American Council on Education, and the British company Pearson, teamed up to “redevelop and administer the General Education Development test [as] a for-profit business.”1

As of 2016, the GED had local affiliates in Bangladesh, Mexico, Myanmar, South Africa, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, and the United Arab Emirates.

For example, the GED program requirements offered in South Africa via the Boston City Campus & Business College are “minimum of a Grade 10 Certificate and 16 years of age to enroll in the programme and take the GED test.”

Meaning a South African high school student can skip the last two years of school and “on successful completion the Learner will be issued a USA High School Equivalency Credential issued by the Department of Education for Washington, DC.”2

What’s more, a South African GED holder who has only finished grade ten (of twelve) can enter a South African university if he or she has been accepted by an American one.

In other words, what began as a “think piece” has been confirmed in all respects.

Does this nix the idea?

Absolutely not.

Quite the opposite. It proves that the concept works and that the demand exists.

The GED is offered by a nonprofit organization. Which means until the joint venture with Pearson, it was not effectively marketed (and, in my opinion, still isn’t).

With the result that to this day it’s relatively unknown.

Refining the Concept

In starting businesses and creating products I’ve found that coming up with the name and the USP (Unique Selling Proposition) and writing an ad are the best ways to bring everything into focus.

So I did.

A name: Graduate High School Today. Subject to improvement, but it contains the USP, is workable, and—unlike GED—does not need to be explained.

And here’s an ad:

Get into College Today—

Without Finishing School

Once upon a time, only geniuses

could get into college early

Not anymore

You can too!

With an American high school diploma

recognized worldwide

You no longer need to wait a year or two or more to graduate from high school.

Thanks to GraduateHighSchoolToday.com, you can get an internationally recognized high school diploma right now—wherever you are in the world.

Why an American High School Graduation Diploma?

Recognized worldwide, it’s your entry ticket to a higher-paying job, or the college or university of your choice—wherever you’d like to go. Any country in the world—except North Korea. (Can’t have everything ☺.)

You Don’t Need to Finish School!

You can take the exams anytime you like. Any age. Any grade. No school records, endorsements, or similar requirements needed.

Instead of sitting in a classroom for the next two or three years, you could be in college or university instead.

Until now, only geniuses could skip grades and get into college early. Today, anyone can do it.

Including you.

It’s Easier Than You Think

You probably already know much of what’s needed. English and math, for example.

You’ll probably need to brush up on a few other subjects such as American history.

We’ll help you. You’ll find virtually everything you need online. Mostly free, too!

Courses. Practice exams. Tutorials. Readings. And the other instructional materials you’ll need.

What’s more, you can learn from the world’s greatest minds and greatest teachers, who make the subjects come alive, make them easier to grasp—and get you ready to take the exam way faster.

And you don’t have to take all the exams at once. (Unless you want to.)

Do one at a time. When you are ready.

You Could Graduate Right Now!

On GraduateHighSchoolToday.com, you’ll find our Tryout.

It’s like a practice exam. Except when you’re done, you get a precise assessment and suggested study guide to cover everything you need to pass the actual exam.

And if you get a passing grade the first time around, you’re ready to do the real thing.

Try it out right now.

No charge.

No obligation.

This draft ad contains all the fundamental concepts of the business model we’re exploring.

Compare this to ged.com and “the power of marketing” (introduced here) becomes crystal clear.

This ad also conveys a single-minded focus in the same vein as companies such as Uber and Airbnb.

Pearson is a large company with a wide range of products, the GED being just one of dozens.

Scale is certainly an advantage. But, arguably, the single-minded focus of a one-product business is a much greater advantage.

A Beginning …

We’ve identified and outlined a business concept that could be as disruptive in the education space as Uber and Airbnb have been in the taxi and accommodation industries.

Clearly, an enormous amount still needs to be done. For example, we don’t have a supplier. A school or state we can team up with to offer the product in the same way GED has done with the Washington, DC, Department of Education, just to begin with. And if you’re wondering where “the world’s greatest minds and greatest teachers” promised in the ad are coming from, the answer is—an online directory selected from the Khan Academy, the many homeschooling sites in the United States, and many elsewhere.

So in terms of this concept, while we’re nowhere near the beginning of the end, we’re close to the end of the beginning.

And just as important, we’ve identified a process for coming up with a new business idea from scratch. A process you can apply in whatever field you choose.

Meanwhile, if your kids or grandchildren are in high school and you’d like to accelerate them into college, you don’t have to wait for this concept to work. Just go to ged.com.

Tea: The Next Retail Revolution?

Worldwide, only one drink is more popular than tea. Water.

Yet, in the “tea space,” there is no Starbucks or McDonald’s equivalent.

As the table shows, there is certainly a tailwind (or, depending on the segment, a steady breeze) in the tea business. Unlike the “espresso revolution,” which was driven by Starbucks, this steady increase in tea consumption is primarily a result of changing consumer tastes.

Businesses are reacting to the trend rather than driving it.

Tens of thousands of them. Mostly small. Especially at the retail end of the “tea chain” in—to use the British idiom—tearooms.

We will do for tea what we did for coffee.

—Howard Schultz

Is there a next-Starbucks opportunity in the tea market?

Howard Schultz certainly thinks so.

Which is what he said when Starbucks bought the 284-store Teavana tea chain for $620 million in December 2012.

That’s a big promise.

Will he keep it?

Before we can address that and related questions, let’s take a quick “walk” around the tea industry.

Tea’s Growth in the USA |

||

Wholesale tea sales ($ value), annual rate of growth: 1990–2014 |

||

Supermarkets/retail |

|

7.86% |

Ready to drink |

|

26.25% |

Food service |

|

6.45% |

Speciality teas |

|

14.95% |

Total |

|

13.51% |

Source: Tea Association of the USA Inc., http://www.teausa.com/14654/state-of-the-industry. |

||

World Tea Production and Consumption |

||

Annual rate of growth (weight): 2009–2013 |

||

Production |

|

5.81% |

Exports |

|

3.44% |

Consumption |

|

5.45% |

Source: Food & Agricultural Organization, http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4480e.pdf. |

||

While we do, we should keep in mind that Starbucks created and rode the espresso revolution by persuading drip and instant coffee drinkers to switch.

The potential opportunities in the tea space appear to be somewhat different.

Howard Schultz Is Not Alone

Howard Schultz is not the only CEO who has expressed an interest in this space.

Louis Vuitton: In 2009, a team of executives from LVMH (which includes Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior), including Chairman Bernard Arnault, seriously studied the possibility of adding Singapore’s upmarket tea chain, TWG, to the company’s portfolio of luxury brands.

Unilever: In 2014, Unilever—the world’s largest tea wholesaler—purchased the Australian packaged-tea chain, T2. Within a year, the brand had been extended into London and New York, with more places to come.3

The Tea Chain: From Producer to Consumer

Like coffee, tea begins as an agricultural product, which is then processed and packaged by manufacturers around the world into a variety of retail products.

The basic mass-market product is black tea (plus, in Asia, green tea), Lipton, Tetley, and Twinings being the major global brands.

You’ll find them in supermarkets pretty much everywhere, along with regional and local brands.

Over the past several decades, the tea market has fragmented in three directions:

1. From basic black and green teas to a wide and increasing diversity of specialty teas, including flavored teas and “nontea” teas such as chamomile and other herbal infusions.

2. Price, as the number of premium, luxury, and midmarket brands and blends have proliferated.

3. The addition of new categories, especially bubble tea, which originated in Taiwan.

These differences have always existed, but they are now becoming mass-market phenomena, thanks to a number of factors, including rising disposable incomes and the reputed health benefits of tea compared to other drinks.

One gauge of this trend is the widespread availability of bottled teas (and nontea teas) in supermarkets, 7-Elevens, and elsewhere.

And tea is available in just about every café, restaurant, and hotel dining room wherever you go. Even in coffee shops: Starbucks grew the Tazo Tea brand, which it purchased for $8.1 million in 1999, into the billion-dollar brand it is today.

But when we turn to retailers specializing in tea we find—

A Crowded and Highly Fragmented Market

Tea-themed retailers can be divided into two broad categories: retailers of luxury and/or specialty teas, and the café/restaurant where tea may appear to be the primary theme, but often is not.

Consider how this second space comes in a multiplicity of smaller market segments. From the posh and expensive British tearoom, whose specialty is afternoon (or, sometimes, “high”) tea, also found in those five-star British hotels such as Claridge’s; to the traditional Chinese teahouse, China’s equivalent of Starbucks’ “third place.” But way cheaper.

And in between are a variety of other niches such as Teavana’s “tea bar,” Japanese and Korean versions of the tea service, Russian tearooms, and what seems to be the fastest-growing segment: bubble tea.

But nowhere do we find a handful of chains that dominate the tea space, as is the case in the coffee café market.

What’s more, I’m willing to bet that 99 percent of people cannot name the leading tea café brand. (It’s not Teavana!)*

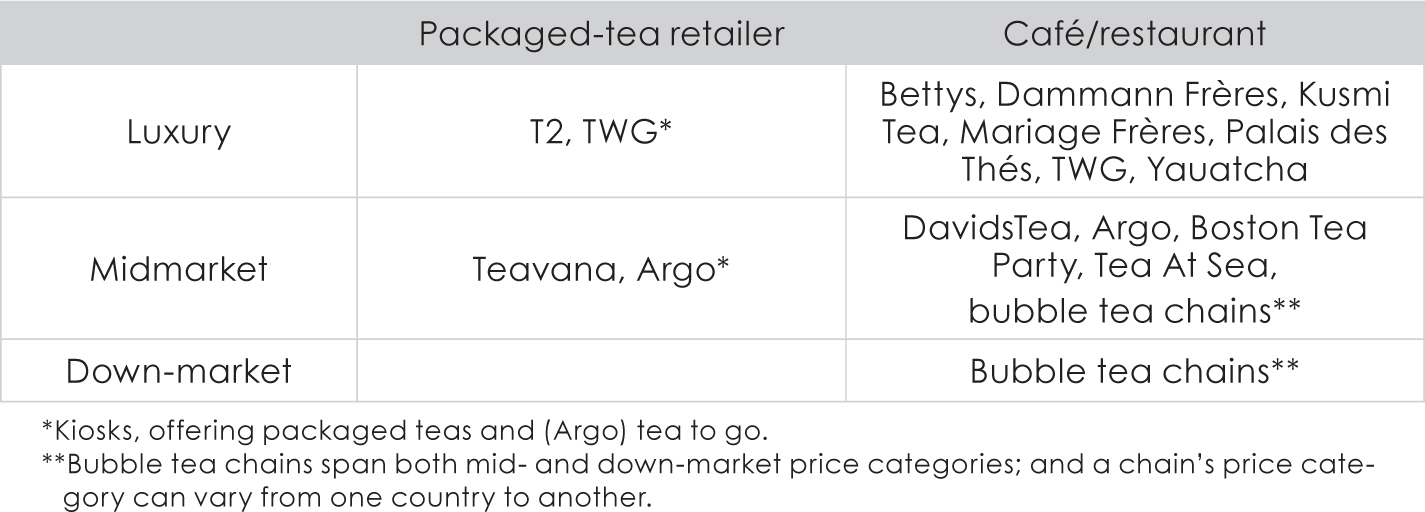

The following table is an admittedly incomplete list of the major tea-retailing brands from around the world:

The companies in this list range from the luxury end of the market (such as TWG and Bettys, and Yauatcha, a modernized version of the traditional Chinese dim sum teahouse) to retailers such as Chatime and Infinitea that specialize in bubble tea. Also known as pearl milk tea and boba milk tea, it’s essentially a tea-based version of Starbucks’ iced Frappuccino.

With the exception of TWG—which has nine outlets in its home market of Singapore—not one of these companies is dominant in its primary market. Not even Chatime in Taiwan.

This is one of the opportunities in the tea café market: branding and consolidation.

My Journey into Tea

What aroused my interest in the tea business was not Howard Schultz’s comment. I came across that long after I had stumbled over an unusual chain named TWG Tea, which led to the discovery of a surprising number of great businesses in this market niche.

I should add that coffee, not tea, is my favorite drink. I can certainly tell the difference between tea from a Lipton tea bag and from a high-quality loose-leaf tea. But, to me, that minor (in my opinion) taste difference just isn’t worth the major (more often, major) difference in price.

That didn’t prevent me (and shouldn’t prevent you) from finding and judging a great business when you see one.

TWG Tea

TWG (short for The Wellness Group) was founded by Taha Bouqdib, Maranda Barnes, and Rith Aum-Stievenard in Singapore in 2008. An upmarket retailer of high-quality teas, today it has forty-five stores in twelve countries. Including one in the United Kingdom—located inside the iconic British department store (and supplier to royals) Harrods. And is available through another twenty third-party outlets in Canada, the USA, Portugal, Germany, Australia, and elsewhere.

TWG in Harrods.

Their teas are not cheap. At New York’s Dean & Deluca, US$34 gets you a 3.5-ounce packet of TWG loose-leaf tea. That’s $9.71 per ounce.

Compare that to Lipton from Walmart: $4.50 for 8 ounces, or 56.3¢ per ounce.

TWG’s tea is even more expensive than one of the world’s rarest coffees. You can find Jamaica’s Blue Mountain coffee at Starbucks Reserve for $29.50. That 8.8-ounce packet weighs in at just $3.35 per ounce. A “bargain” at one-third the price of TWG’s offerings.

If you order tea at one of TWG’s stores, you will drink it from a Limoges porcelain cup. Be careful not to drop it: the cup and saucer set cost $48.

And while you’re there, you might like to pick up a teapot like the one above, finished in twenty-two-karat gold. Just $575 (plus tax, where applicable).

TWG is definitely not a mass-market retailer. If executives at Lipton’s and Twinings don’t sleep soundly at night, it’s definitely not because TWG is invading their market.

Upmarket Tea: The Potential in This Niche

TWG’s forty-five locations do prove that there is a market for a truly upscale tea shop. In its Singapore home, population 5.4 million, it has six locations (not counting three at Changi Airport), or around one store per million.

Based on the penetration of TWG and four French chains—Mariage Frères (ironically, the inspiration for TWG), Palais Des Thés, Dammann, and Kusmi Tea*—we can confidently project somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 outlets in this space, worldwide.

This is clearly a market segment with enormous potential growth.

TWG, as a subsidiary of another Singapore-based retailer, OSIM, does not offer an investment opportunity in this space. While OSIM does not break out TWG’s sales or profits in its financials, TWG’s 52 outlets are a mere 6.8 percent of OSIM’s total of 762 retail locations.4

But it’s not the only one at the luxury end of the market. For example, consider what could be—

The World’s Leading Tearoom?

Bettys. No apostrophe. Based in Harrogate and York, in the UK. A two-and-a-half-hour train ride north of London.

Bettys was established in 1919 by Swiss confectioner Frederick Belmont.

“Belmont spent his teens in apprenticeships for all manner of bakers and confectioners across Europe. By the time he arrived in England, his head was filled with knowledge of their craft.”5

In 1962, Bettys acquired Taylors of Harrogate, a specialist in teas and coffees, founded in 1886.

Today, Bettys has six outlets—the original café in Harrogate, and five in York, just twenty-one miles away. Via their Web site they deliver anywhere in the UK and (for selected products) “as far as Tokyo.”

By all accounts, Bettys is renowned for its mouthwatering cakes. But what really sparked my interest was the number of comments mentioning long lines of customers waiting for a table. Sometimes, thirty or forty-five minutes.

Long lines of waiting customers—what every retailer loves to have.

I’m definitely interested in any business that has customers backed up around the corner.

Bettys is certainly doing something right. But what?

A quick Internet search brings up hundreds of customer comments, nearly all four and five stars. A few examples (from tripadvisor.com)6 give the “flavor”:

This is the most amazing and delightful place for morning or afternoon tea—it’s like stepping into the past. The service is superb and the atmosphere terrific.… I enjoyed the best coffee I have tasted since leaving Australia and the lightest and tastiest raspberry tart ever. This is a must for anyone visiting York—breakfast, lunch and morning and afternoon teas. Clean toilets. —Lonescot, England

Lovely, charming place and traditional in all respects. Never disappoints. Tea or coffee choice to please all. Cakes or snacks to please all. Staff there to please all. What more do you want? —kwc973, Melton Mowbray, UK

The original Bettys in Harrogate: 3:00 p.m. on a cold December day.

It was like stepping back in time. Old fashioned tea room service, with someone playing the piano, it’s no wonder it’s the most popular place in York! Loved the Tea Trolley! Lovely atmosphere with great friendly service. Can’t wait to come back again! —dieterjonentz, Forres, UK

First impressions suggested Bettys’ primary appeal was its cakes, and these are the product most often singled out for the highest praise. A tribute, indeed, to Bettys’ founder, and his successors.

But clearly, Bettys’ overall appeal is its total ambience. The total customer experience.

The answer to the question “Bettys is certainly doing something right. But what?” appears to be everything.

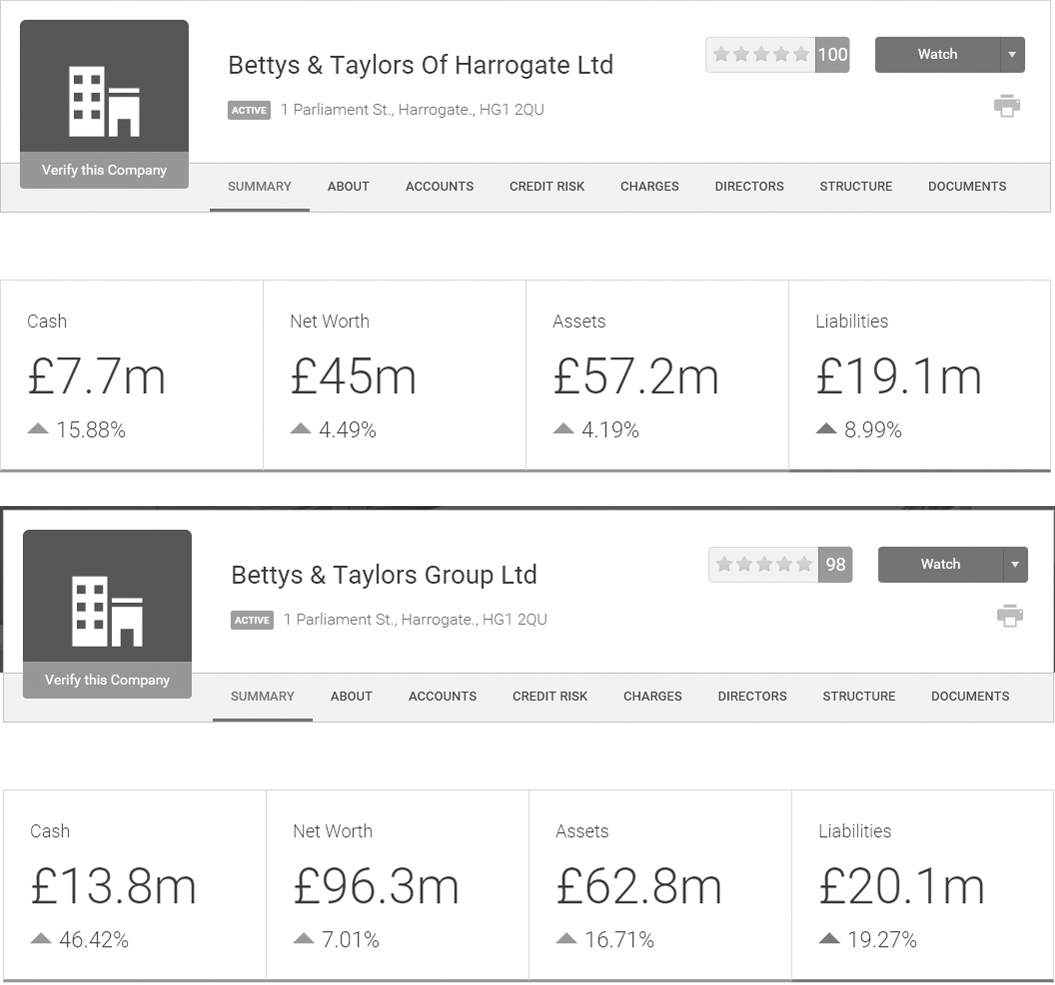

My next step was to ask people I know in the UK about Bettys. One friend, Henry Newrick,* ran a credit check for me:

As for Bettys. It sure ain’t your ordinary tearoom.

I did a “credit” search. I have done thousands over the years on companies (in fact 300 this weekend). It is the only time I have ever seen a company with a 100% credit score. Even the strongest blue chip businesses almost always end up in the 80s or low 90s.

Bettys has 6 shops and just look at its balance sheet [screen shot below]. £7.7 million in the bank and a net worth of £45 million!

Its parent company does even better with a net worth of £96 million and almost £14 million cash:

Yet for some strange reason the parent only has a 98% credit rating!

Clearly what they are doing right is “service” targeted at the British and foreigners’ love of British tradition. I’d be surprised if a lot of their customers are not Chinese and Japanese visitors.

Without ever going near the place I’d say exemplary service and premium pricing.

Wow!

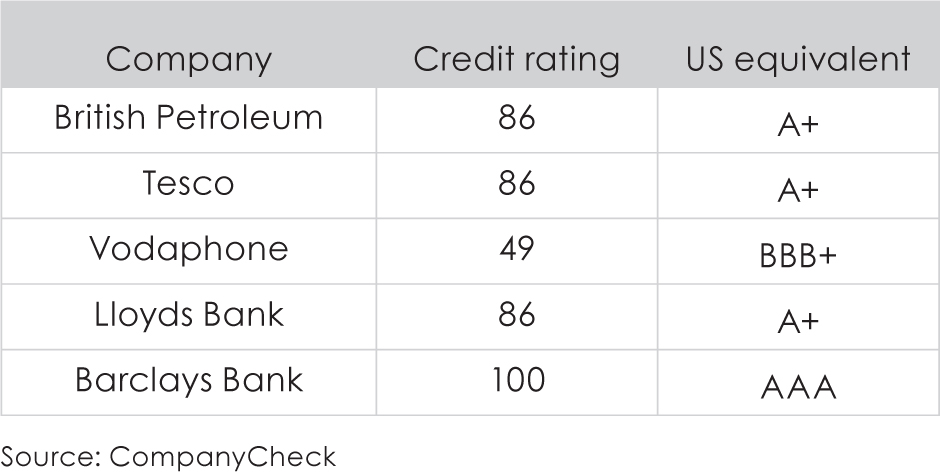

A 100 percent (or AAA) credit rating and two great big piles of cash!

To put this in perspective, compare Bettys’ AAA credit rating with that of some of Britain’s biggest companies:

Bettys is up there with the only British bank with a 100 percent credit rating: Barclays. Fortuitously, my daughter, Natasha, was traveling around Europe at the time. So I asked if she’d like to have afternoon tea in York. One look at the cakes on Bettys’ Web site was enough to convince her:

I went to Bettys in York, which is just like a normal café. And in the afternoon to the original Bettys in Harrogate.

I arrived at Bettys in York at 10 o’clock in the morning and it was already busy. Packed. I didn’t have to wait for a table, which was lucky, as a line was starting to form outside.

Inside, there was a long line for the bakery. People taking cakes home for their morning tea:

I thought both the York and Harrogate Bettys were lovely. Here’s the view from my table in York:

I asked a few people why they came to Bettys. Some said they were there just because they’d never been there before. [Such, it would appear, is the power of Bettys’ reputation.]

The general consensus of people who live in the area and keep coming back is that Bettys’ [customer experience] is always consistent. They said the service is always good, the food is always high quality, which is why they’re happy to come back again and again.

I talked to a lady from Harrogate who said she hadn’t been to Bettys for ten years. She was there to treat a visiting friend, as though going to Bettys is a must if you’re ever in the area.

My own experience confirmed everything I’d heard. The service was impeccable. Fantastic! Everything was beautifully presented. And the food was amazing (right):

Even though it was morning, I had the afternoon tea.

I tried the sandwiches obviously. They were great. Unlike sandwiches you normally get in England, Bettys’ don’t skimp on the filling, which impressed me.

The scones and cakes are great as well. I had a layered coffee cake, a fruit tart, and a macaroon. I have to say that I was very unimpressed with the macaroon but the other cakes were amazing.

In the afternoon I had a second afternoon tea at the original Bettys in Harrogate.

It’s enormous (below):

If you have the “Lady Bettys” afternoon tea there, everything is much more posh. You’re greeted by the staff when you arrive, have your coat taken, and are seated in a private dining room with live piano music (next page):

The regular afternoon tea costs £18, which seems about right to me. The “Lady Bettys” was £32, or £39 with champagne:

I think that was a bit much. But it was a beautiful, beautiful setting. The food was really great too.

Not to mention the view.

As you can see (top right), the “Lady Bettys” is a lot fancier.

The tea’s good, you can have as many sandwiches as you like, the raisin and lavender scones are wonderful, and come with proper clotted cream:

And the cakes are to die for. Like this chocolate cake with raspberries on top:

I couldn’t eat everything.

I had a half-eaten sandwich and I asked the waiter to pack it for me. He said: “Don’t worry about it. I’ll give you a new one.”

When you get the bill, they give you a 30-gram tin of special blended Bettys tea to take with you that you can’t buy anywhere else.

I was so full I couldn’t eat anything for a whole day!

I don’t know about you, but just from the pictures I’m lusting after those cakes!

I’ve devoted, perhaps, more space than necessary to Bettys. Especially since Bettys won’t franchise and has no intention of opening outlets “too far from their bakery.” Which effectively means not outside the York/Harrogate area.

So where’s the business or investment opportunity?

First, Bettys clearly offers a retail gold (if not platinum) standard of service. So seeing and experiencing what this company does could lead to an upgrade in the customer experience of just about any business.

Second, Bettys will actually teach you some of their “secrets.” Four or five days a week Bettys’ Cookery School is open for business.7 If you’re in a similar market niche, spend a couple of weeks in York and you’ll be able to walk away with several of Bettys’ most popular recipes.

You’ll also be able to nose around a bit and learn some of the company’s backroom “operational methodology.”

But what if you have neither the intention of traveling halfway around the world just for afternoon tea nor the money to do so?

You don’t need to.

Use “3-D processing,” combined with the Disney Strategy (here) instead.

Create a mental image of Bettys’ customer experience from the description above, plus the abundant comments, articles, and even videos to be found.

In just half an hour or so you’ll have a detailed appreciation of the customer experience “as if” you had actually been there.

If Bettys is not in the business space that interests you, simply choose an exemplary company that is.

This exercise enables you to create your own gold standard for the customer experience. You can then apply that to create or improve the level of service in your business and to critically judge the customer experience at businesses you frequent regularly.

Put on your copycatting hat and check it out.

A Third Model: Teavana

TWG and Bettys represent two different segments in the upmarket tea café space.

TWG’s prime focus is the tea. It operates restaurants where you can sample their teas, but TWG’s food has nowhere near the attraction of Bettys’.

TWG also appeals to what I call the conspicuous consumption market. I know of a number of people who serve TWG teas at home not because they’re tea connoisseurs but to impress their friends. (When their friends aren’t around, they drink Lipton or Twinings.)

Bettys is quite different. Though called a tearoom, the real attraction is the food, especially the cakes.

Yes, they’re also known for their high-quality teas. Indeed, their Yorkshire Tea brand is Britain’s third most popular packaged tea.

But Bettys’ prime focus is afternoon tea.

From a commercial point of view, one benefit of the tearoom concept is that the restaurant area can be busy in the mornings and the afternoons, times when many restaurants are empty or even close their doors.

The light meals offered also appeal to the lunch and breakfast trade. So a tearoom can be busy pretty much all day, especially in those times between breakfast and lunch and lunch and dinner when most other restaurants are nearly empty.

Teavana offers yet another model.

The Teavana Model

When Starbucks purchased Teavana, it was primarily a retailer of packaged teas.

All outlets enable passersby to sample a couple of Teavana’s teas without actually entering the store. And some offer tea to go.

With no seating, each Teavana outlet is a relatively small place with therefore (again, relatively) a low rent.

Howard Schultz’s promise to “do for tea what we did for coffee” implied that Teavana would follow the Starbucks model of a café/restaurant.

And sure enough, on 24 October 2013, Teavana opened the first of a projected one thousand8 “tea bars,” in New York.9 Two years later, Teavana had six tea bars, three in New York, and one each in Seattle, Beverly Hills, and Chicago.

However, with the exception of the Seattle outlet, they were all shut down in January 2016.*

Teavana reverted to its original model. At least, in the United States.

Does this mean Starbucks is retreating from the tea space?

The answer is a helpful yes—and no.

What Tea Means for Starbucks

Tea is important to Starbucks.

In some markets, especially China and India, tea can outsell coffee in Starbucks stores.

As the company’s rebranding of “Starbucks Coffee” to just plain “Starbucks” indicates, you’re invited to come to its “third place” for coffee, tea, a snack, or any other reason you like. Including (in the United States) free Wi-Fi.

Tazo Tea, purchased by Starbucks in 1999 for $8.1 million, is, today, a billion-dollar brand, selling packaged and ready-to-drink teas through Starbucks and grocery outlets.

When Starbucks added Teavana to its tea portfolio, its announced intention was to make Teavana one of “the largest global brands” by achieving “$2 billion in sales” within the next five years.10

By the end of 2015, Teavana was halfway to that goal. It had expanded to a total of 411 outlets: 327 in the United States, 61 in Canada, 16 in Mexico, and 7 across the Middle East.

But most of Teavana’s growth (so far) has come from offering Teavana teas in Starbucks and elsewhere, rather than from expanding Teavana’s retail footprint. And cannibalizing Starbucks’ Tazo Tea brand.

Nevertheless, according to Howard Schultz, Teavana is the fastest-growing segment within Starbucks, and that “I’ve never been more passionate, more enthused about what we’re doing and what I think is possible.… We believe that Teavana stand-alone stores will be a big idea not only in the U.S.… but a much bigger idea in Asia over time.”11

In 2016, Starbucks rolled out its Teavana brand across Asia with heavy in-store promotions, starting with China in August, and ending with India and Japan in December.

This suggests Teavana’s future will follow the path of most other Starbucks acquisitions.

Over the years of its existence, Starbucks has purchased a wide variety of other companies and brands in addition to Tazo Tea and Teavana. Evolution Fresh (water), La Boulange (bakery), and Seattle’s Best, among others.

Of all the brands it has acquired, only one other than Teavana—Seattle’s Best—survives as a stand-alone brand.

It bought La Boulange to acquire its baking expertise. Soon thereafter, all La Boulange stores were closed, despite the original intention of keeping them going.

When it purchased the manufacturer of the Clover coffeemaker, production was reserved for Starbucks stores, and service to preexisting customers was discontinued.

Seattle’s Best, a competitor Starbucks acquired in 2003, continues as a separate but subsidiary operation. Relegated to small outlets in gas stations and similar places catering to the takeout trade. As well as selling its own brand of lower-priced packaged coffees through groceries and other outlets, including Burger King, which now features Seattle’s Best coffee on its menu.

Seattle’s Best is a way for Starbucks to leverage and extend its range of coffee sales while preserving the Starbucks brand as the third place—and premium coffee brand.

In sum, Starbucks has acquired companies solely to enhance the Starbucks brand. This unrelenting focus on Starbucks suggests that Teavana’s future path is primarily as a Starbucks adjunct brand. And as a packaged-tea retailer along its original model—a model not competitive with Starbucks itself.

This implies that the tea bar niche is potentially wide open—and that any entrant does not need to worry about a competitor with Starbucks-like financial resources.

Second, though Teavana appears to be the world’s largest chain specializing in packaged-tea retail outlets, on a worldwide scale its footprint is tiny. Suggesting there is plenty of room for Teavana copycats to succeed.

Teavana’s main competitors in the United States are online. Companies such as Talbott Teas, owned by the Jamba Juice smoothie chain, and Stash Tea, primarily a wholesale tea brand sold in grocery stores and online, as well as supplying food-service outlets around the United States. Plus specialty stores such as Harney & Sons12 and Bellocq (both New York stores with an online presence), and just about every other tea brand and tea packager, from TWG to Twinings—not to mention other online retailers such as Amazon and Walmart.

But the entry of the Unilever-backed T2 brand into New York suggests the competition in this space is about to heat up.

Bubble Tea

Bubble tea chains currently appear to be the fastest-growing segment of the retail tea market.

The original bubble tea, invented in Taichung, Taiwan, in the 1980s, was a hot black tea mixed with condensed milk, syrup or honey, and tapioca pearls. Which is why it’s also known as pearl tea.

Today, these chains offer a wide variety of mixed drinks, hot or (mostly) cold, ranging from the original bubble tea to juices and smoothies, with all sorts of unusual combinations in between.

Having sampled a few bubble teas, my reaction is similar to my attitude to Louis Vuitton handbags: I certainly understand that people buy them; but I can’t emotionally relate to the why.

So I asked a number of regular customers of these chains what the attraction was. “Variety” was a common answer. The range of their offerings extend from the pedestrian to all manner of weird combinations. A few examples: milk tea with caramel and sea salt on top, brown rice green milk tea, and taro milk tea (though the teenage customers I’ve spoken to disagree; “Not weird at all,” they say, looking at me as if I’m the one that’s weird).

Call me old-fashioned, but I’ll definitely pass on this combo.

Price was another important attraction, especially in countries such as Taiwan and the Philippines, where competition is fierce.

“A nice change” was a reaction from a Starbucks regular.

The primary market is takeout, and most of these chains offer drinks only. Though some of those drinks come with ingredients that make them more like desserts. The cost of establishing a bubble tea store with no seating is relatively low.

Those bubble tea outlets with seating are often teenage hangouts. “Sometimes you see an old person. Thirties or so. But mostly young,” one teenager told me.

In all cases, the service is usually quick. So the attraction boils down to a combination of speed, price, variety, convenience, and something different.

Tea Cafés, Tea Bars, Tearooms—and Teahouses

What is the difference between a tea café, a tea bar, a tearoom, and a teahouse?

Two of these names conjure up distinct images. A tearoom is the upscale British concept, typified by Bettys. A teahouse is the traditional Chinese model.

Yet, Chatime, Happy Lemon, and the myriad other bubble tea vendors are called teahouses. All they have in common with the traditional Chinese teahouse is that they are Chinese in origin and serve tea, among other things.

One thing you can’t buy at a bubble teahouse is the central USP of the traditional version: a pot of green tea.

Compare Happy Lemon (left), one of the largest bubble tea chains, with the renowned Hong Kong traditional teahouse, Lok Cha (right).

“Tea bar” is a marketing concept (and a good one). But there’s no difference between a tea bar and a tea café.

We need a more meaningful way to segment the retail tea market.

The key distinctions are:

• Price: luxury, midmarket, or down-market.

• Type: the café/restaurant or the packaged-tea vendor.

Using these distinctions gives us a better handle on the possibilities in this market niche.

Packaged Teas

The dedicated packaged-tea retailer is a small part of this market, Teavana and T2 being the leading examples.

Though they are not alone. The “Teavana model” of a small, low-rent space focusing on packaged teas is also offered by café/restaurants such as TWG and Argo.

This space has only two price segments: luxury (TWG and T2) and midmarket (Teavana and Argo).

The key element to success is to offer a wide range of teas (and “nontea” teas).

Café/Restaurant

Bettys is the prime example of the upscale British tearoom. But this segment of the market is mainly dominated by hotels offering the “British afternoon/high tea,” especially in Britain. While the midmarket space is essentially competitive with Starbucks and other coffeehouses.

Indeed, the primary difference between a coffee shop and a tea café is that in one you can buy coffee beans (and also get a cup of tea), while the other has wall-to-wall teas (and you can also get a cup of coffee).

Some bubble tea chains occupy the down-market segment, mainly in countries where competition is fierce. In most countries, they’re in the midmarket price range. A quick summary of the companies we’ve mentioned so far:

Luxury Tea

With TWG, Teavana/T2, Bettys, and bubble tea, we’ve identified four different markets within the tea space.

TWG and T2 represent the high-end, luxury retailer of a wide range of high-quality loose-leaf teas. As luxury retailers, they benefit from conspicuous consumption: the purchase of products for the purpose of impressing other people.

Teavana, Argos, and Davids are midmarket equivalents of TWG, offering a smaller range, with many of the “teas” flavored in such a way as to have little relation to tea in the traditional sense of the word.

The endorsements of Howard Schultz, Bernard Arnault, and Unilever are clear evidence of an enormous business opportunity in this niche.

The Bettys Tearoom Model

Bettys is based around the specifically British tradition of afternoon tea mixed with high tea (a minimeal, with tea), and Devonshire tea (an afternoon tea combination of a pot of tea accompanied by scones, jam, and whipped or clotted cream; not the wimpish, American low-fat version of cream, either). Champagne is optional.

The Bettys experience is exportable as is. Indeed, it has been exported; you can enjoy the “British afternoon tea experience” in the Pierre Hotel (New York), the Tea Cosy (Sydney, Australia), or the Marriott Hotel (Singapore), and hundreds of other places around the world.13

Clearly, the appeal of Bettys’ underlying USP of (let’s not beat around the bush) beautifully presented “sugar shock and fat overload,” combined with superb service, is universal.

While far from an empty space, a Bettys-style chain is a possibility. Alternatively, existing upscale restaurants could expand their customer base and utilize those empty morning and afternoon hours by offering a Bettys-style experience.

The Tea “Café”

Several companies are already in this space. A few examples:

Argo Tea, one-tenth the size of Teavana, has an interesting combination of tea cafés and TEAosks: small, attractively designed kiosks offering a range of packaged teas and teas and pastries to go.

DavidsTea, the Canadian tea café chain with 187 outlets in Canada and the United States, with plans to expand to 500 in the next few years.

And from Britain, a chain that could be a big hit in the American market—just from its name:

Boston Tea Party. A café chain that looks similar to Davids. And, indeed, to Starbucks—with coffee replaced by tea.

Unlike Teavana’s tea bar, some of these chains serve coffee as well as tea, thus competing with the Starbucks experience.

But given the small size of these chains, a market leader has yet to emerge, so the business opportunities (plus a wide variety of franchise and country-franchise options) appear to be legion. While DavidsTea, as the largest, is currently the leading candidate, a now small or even totally new company could be the winner here.

We can come to a similar conclusion about the prospects in the bubble tea market. With the difference that, as this concept appears to be most popular in Asia, unless a China- or India-based chain arises, one of the existing Taiwanese chains is likely to be the Starbucks equivalent in this niche.

Investment Options

The investment opportunities seem limited, as the majority of the retail tea brands are submerged in much larger companies. For example, if the T2 brand were to multiply its profits ten or even a hundred times, Unilever’s share price would hardly move. And Teavana’s prospects, even if fulfilled, are not reason enough to invest in Starbucks. Though it may add to the attraction.

Just three publicly traded companies focusing on the tea retail sector remain: Canada’s DavidsTea, and two Taiwanese companies, La Kaffa International (owner of Chatime) and Ten Ren Tea.

However, the financial information available on the Taiwanese companies is minimal. Even if you’re fluent in Chinese.

As I write these words, DavidsTea remains the primary investment possibility.

Publicly Traded Tea Companies and Tea Brands

Canada:

DavidsTea (DTEA, Toronto and Nasdaq)

Hong Kong:

Longrun Tea (2898.HK, Hong Kong)

India:

Tata Global Beverages (TATAGLOBAL.BO, India)

Japan:

Ito En Ltd. (ITOEF, Japan)

Tea Life Co. Ltd. (TEALF, Japan)

Singapore:

TWG (via Osim, O23.SI, Singapore)

Taiwan:

Chatime (La Kaffa International, 2732.TWO, Taiwan)

Ten Ren Tea Co. Ltd. (1233.TW, Taiwan)

USA:

Farmer Brothers Co. (FARM, Nasdaq)

Teavana and Tazo (via Starbucks, SBUX, Nasdaq)

On the surface, the business prospects for the company seem bright, and the company’s stated mission and vision are clear and appealing.* Customer comments are positive,14 suggesting the company offers a good customer experience.

But several question marks hover over the company. Its expansion into the American market is not paying off as projected. And in March 2016, the cofounder and visionary behind the company, David Segal, resigned.

Bad signs, to say the least. But the company is possibly worth keeping an eye on for future reference (see appendix 3, “DavidsTea,” for a detailed analysis).

Meanwhile, alternative investment opportunities could appear if other specialized tea retailers such as the Boston Tea Party, Argo, or Tea At Sea go public.

Fast Casual

“Fast casual” is a fast-food category that arose in the United States in the late 1990s.

It occupies a space between fast food (McDonald’s, KFC, Pizza Hut, and so on) and sit-down restaurants with table service (TGI Fridays, Applebee’s).

The primary differences between fast food and fast casual are:

1. Price, ranging from $9 to $13 compared to around $5 for fast food.

2. Preparation. Fast food is usually prepared in advance; fast casual is made to order.

While the wait time is longer for fast casual, a limited menu ensures that it is short. Other differences include a focus on fresh, healthy ingredients, and table service, with an average of around 50 percent of orders being for takeout.

While people disagree over the precise definition of fast casual (for example, Euromonitor includes Buffalo Wild Wings, Technomic does not, while the industry Web site, fastcasual.com, includes Starbucks!), it is generally agreed that the category was kicked off by Fuddruckers and Au Bon Pain in the nineties, and that the leading fast casual brand today is Chipotle Mexican Grill.

“Fast Fine” Dining—a New Category?

Fast casual has spawned what could be a new category called fast fine dining.

These are quick-service restaurants started (so far) by full-priced fine-dining restaurant owners, with a limited menu of the same high-quality ingredients.

Examples include seven Larkburger stores in Colorado (larkburger.com), opened by Thomas Salamunovich, a classically trained chef, proprietor of the Larkspur Restaurant in Vail; ’Wichcraft sandwich chain in New York (wichcraft.com); and Farm Burger (www.farmburger.net), based in Atlanta.

It remains to be seen whether this will become a widespread category. One potential limitation: most (though not all) of these quick-service restaurants ride on the back of a full-service restaurant. The advantage: the smaller restaurants can entice new customers into the main one. Though that has not prevented Farm Burger from expanding into California and North Carolina.

Watch this space!*

That the growth in this niche is far from over is demonstrated by the entry of McDonald’s into this space with its touch-screen ordering system, which enables customers to personalize their order just as they do in Chipotle.

Let’s apply the five clues to the market leader to see how it stands up.

Chipotle Mexican Grill

1. They Permanently Change People’s Habits

Although not the originator of the concept, Chipotle’s success led to fast casual’s dramatic growth from next to nothing to 5 percent of restaurant sales in the United States—or $35 billion!

To put that in perspective, that’s a growth of—

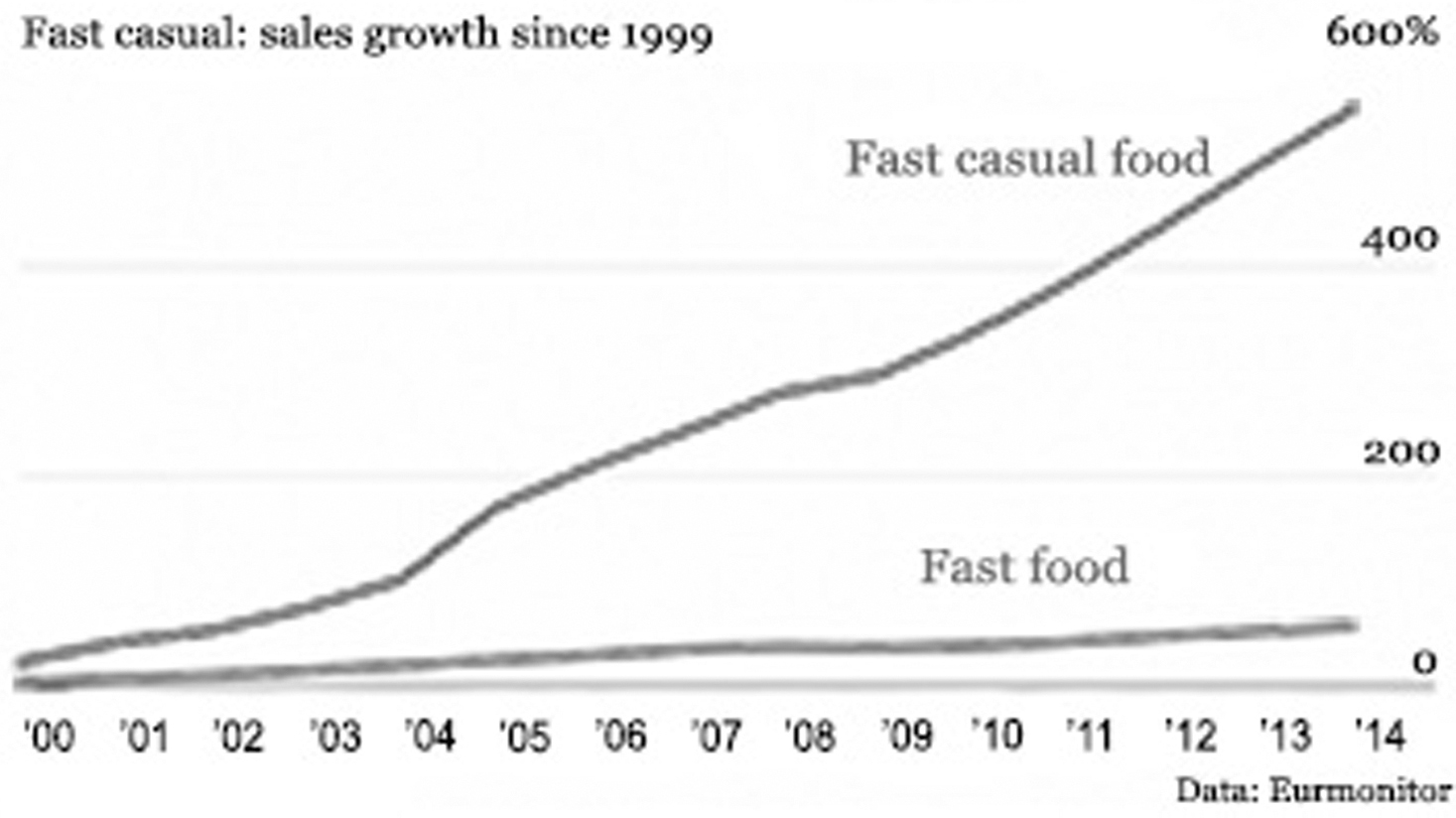

550% percent since 1999, more than ten times the growth seen in the fast food industry over the same period, according to data from market research firm Euromonitor. Chipotle … has seen its sales more than quadruple during that time; Panera, another oft-used example, has watched its sales more than triple.15

2. They’re Copycats

Chipotle founder Steve Ells credits the taquerias he had seen in California as the inspiration for his business idea.

However, he did not set out with the aim of starting a nationwide chain. A classically trained chef, he saw the first Chipotle (opened in 1993) as a way of learning the business side of the restaurant trade at a low investment cost.

His intention was to then step away from it to achieve his primary aim: setting up a full-service restaurant.

But when his first store was selling 1,000 burritos a day, compared to his break-even projection of 117, he recalls, “It was making much more money than I had ever anticipated. In my heart I was ready to start thinking about a fine-dining restaurant. A few people said, ‘Steve, you should open another one of these.’ So I called my dad, and he’s, like, ‘Really? Do you think Denver could have two of them?’”16

Eventually Ells realized he was fulfilling his original passion through using only fresh, and then organic, ingredients, and he dropped the idea of starting a full-service restaurant.

In 1998, McDonald’s invested in Chipotle, which enabled the company to expand from 13 to 489 outlets at the time McDonald’s divested its stake in January 2006. For Chipotle, the association was a powerful learning experience, as it had inside access to the entire McDonald’s system.

Although very different companies—for example, the only ingredient Chipotle and McDonald’s have in common is Coca-Cola—Chipotle moved rapidly along the learning curve thanks to McDonald’s input—and capital.

3. Their Success Is Validated by Competition

Chipotle’s success has inspired two kinds of copycats:

Direct copycats. For example, Qdoba Mexican Eats (www.qdoba.com), founded two years after Chipotle, offers a similar menu and customer experience. Qdoba has grown to 641 stores compared to Chipotle’s 1,700, proving that there’s a wide market for this concept in the United States.

Concept copycats. Chipotle itself is a concept copycat, to the extent it copied the initiators of the fast casual trend, Panda Express and Panera Bread.

Companies such as Wingstop (1994), Shake Shack (2004), and especially Blaze Pizza (2012) are a few examples of the concept copycats that are expanding the fast casual category to almost every possible cuisine.

4. They’re Driven by the Founder’s Vision and Passion

Founder Steve Ells’s original vision was diverted by the success of the first Chipotle into a quick-service restaurant serving food of fine-dining quality.

“[People] thought I was crazy,“Ells said, “but I had a very strong vision for the way Chipotle was going to look and taste and feel, and I knew it wasn’t going to be a typical fast-food restaurant.

“The idea was simple: demonstrate that food served fast didn’t have to be a ‘fast-food’ experience. We use high-quality raw ingredients, classic cooking methods, and a distinctive interior design and have friendly people to take care of each customer—features that are more frequently found in the world of fine dining.”17

Eventually, Chipotle’s vision and mission were summarized into Food with Integrity. Ells explains:

While using a variety of fresh ingredients remains the foundation of our menu, we believe that ‘fresh is not enough anymore.’ Now we want to know where all of our ingredients come from, so that we can be sure they are as flavorful as possible while understanding the environmental and societal impact of our business. We call this idea Food with Integrity, and it guides how we run our business.18

In 2015–16, this slogan lost much of its credibility as a series of salmonella, E. coli, and other infections hit Chipotle’s customers and led to a dramatic fall in the company’s sales and reputation.

We’ll address Chipotle’s reaction to this crisis in “Reputational Risk,” below.

5. They Have Superb Management and Execution

Steve Ells’s aim is to provide food “that is prepared in front of customers with a perfectionism that would defeat fancy sit-down establishments.”

Business Excellence agrees:

Even the company’s growth strategy challenged orthodoxy: founder Steve Ells took a $360 million investment from McDonald’s and used it to fund the rapid expansion, which led to an IPO. That success allowed him to buy out McDonald’s, which exited with a handsome profit.

Obsession over details is a hallmark of Ells’s leadership; it took him four years of research and development before he approved the company’s custom-designed tortilla warmers.

“We hire for talents you can’t teach,” Ells told me. “Things like work ethic and honesty. We want people who are curious and capable of infectious enthusiasm. You can’t teach this—but you can teach them how to run a Chipotle Grill.”19

What Steve Ells looks for in applicants also relates to clue number four. Having curious and enthusiastic people on your team makes the job of transmitting the founder’s vision and passion easier, ultimately leading to the unique customer experience that’s the company’s “trademark.”*

Reputational Risk: Is Chipotle Hazardous to Your Health?

Clearly, Chipotle’s otherwise excellent management had one rather large hole: food safety.

The possibility of serving contaminated food comes with the territory. Restaurant and grocery chains from McDonald’s to Whole Foods have unwittingly sold food products that have infected their customers.

Indeed, 4,163 food-borne illness outbreaks were reported in the United States between 2010 and 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.20

It takes twenty years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.

—Warren Buffett

When, like Chipotle, a company makes a point of using a wide variety of local suppliers, the result can be a monitoring nightmare. As a friend of mine put it, “If a mom-and-pop outfit is one of your suppliers, you may never know when the cows have been shitting in the vegetable patch.”

An exaggeration perhaps, but it highlights the problem rather vividly.

For Chipotle, this was not a one-off problem, but a whole series:

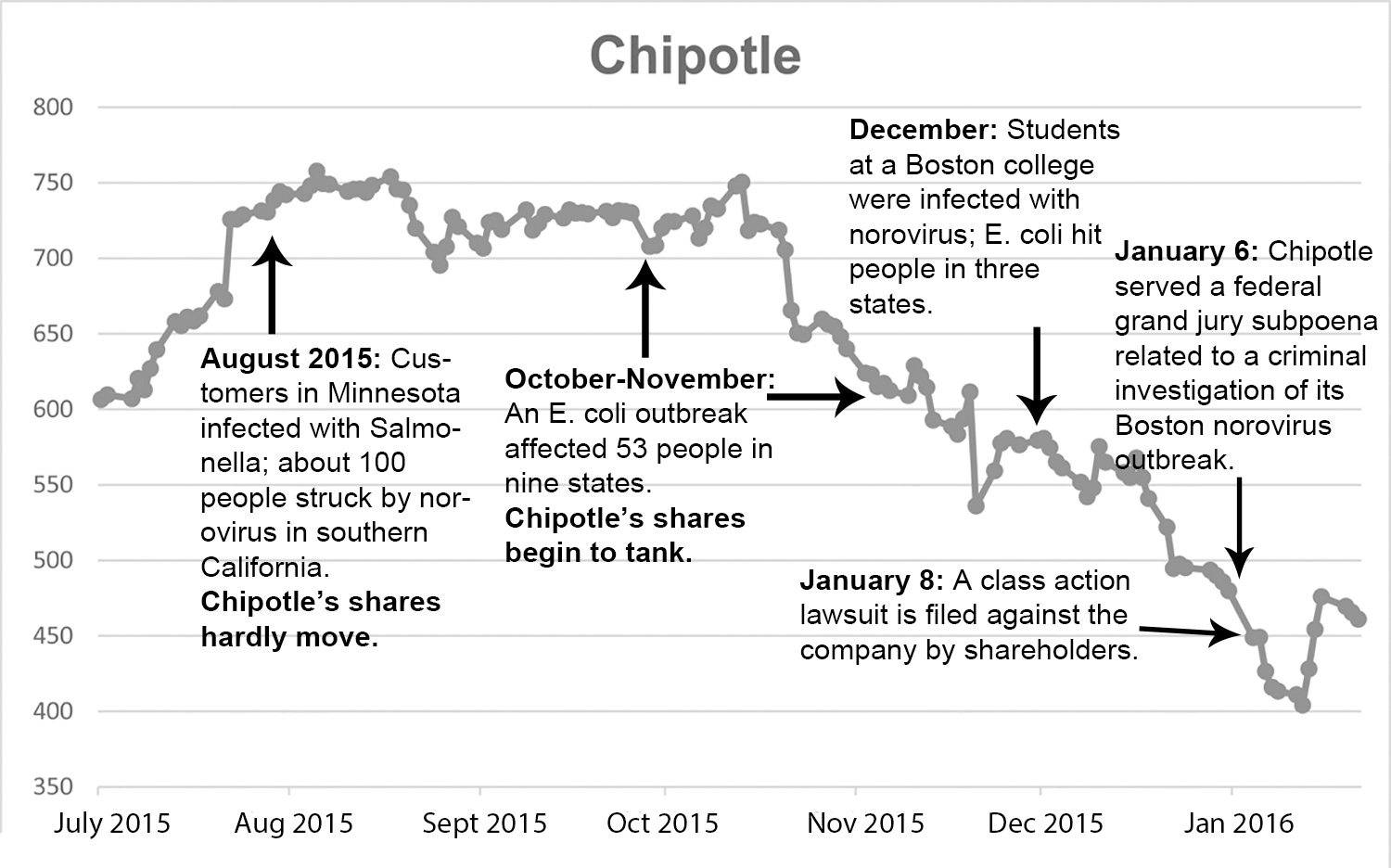

• August 2015: “Sixty-four customers in Minnesota were infected with salmonella and about one hundred people were struck by norovirus in Southern California.”21

• October and November 2015: An E. coli outbreak affected fifty-three people in nine states.22

• December 2015: Around 140 students at a Boston college were infected with norovirus; another incidence of E. coli hit five people in three states.23

The Vultures Gather

• 6 January 2016: Chipotle revealed it had been served a federal grand jury subpoena related to a criminal investigation over its norovirus outbreak in Boston.24

• 8 January 2016: A class-action lawsuit is filed against the company and certain of its officers by shareholders alleging they were deceived about the company’s food-safety practices.25

Unsurprisingly, Chipotle’s same store sales fell 14.9 percent, and its share price followed suit.

Does this mean we should write off Chipotle as an investment candidate—or leap in and scoop up shares at bargain prices?

A little history will help.

Remember what happened to Jack in the Box in 1993? And Taco Bell in 2006?

Few people do.

In 1993, 732 Jack in the Box customers were infected with E. coli. Forty-five children required hospitalization and four of them died.

The company’s initial reaction was denial. But eventually they admitted that they had ignored new Washington State regulations that would have prevented the infections.26

It took over a year for Jack in the Box’s sales to recover—and by 1997 they were “considered the leader in food safety in the fast-food industry”!

In 2006, seventy-one Taco Bell customers were infected with E. coli, shredded lettuce being the most likely culprit.27

It was eighteen months before Taco Bell’s same store sales recovered.

For Chipotle, solving its food-safety issues is a matter of survival. And solving them is doable.

So there’s every reason to assume Chipotle’s sales (and share price) will follow the same trajectory.

The Downside

Most likely, the vultures suing Chipotle will have to be paid to go away. Whether through a settlement or by fighting and losing the various lawsuits, Chipotle will probably end up paying out several million or tens of millions of dollars that will come straight off the bottom line.

And if the criminal investigation results in a charge, and Chipotle loses that, too, it will presumably have to pay a pretty hefty fine.

In addition, solving its food-safety problems will incur additional costs and may increase the company’s cost base over the long term.

The net effect: a onetime financial event resulting in a onetime charge against profits, as happened when Starbucks lost its case with Kraft.

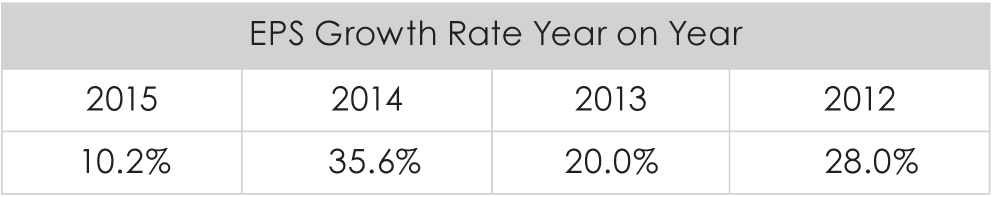

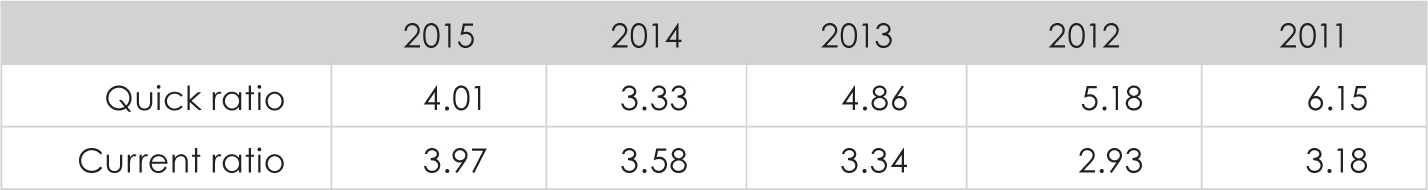

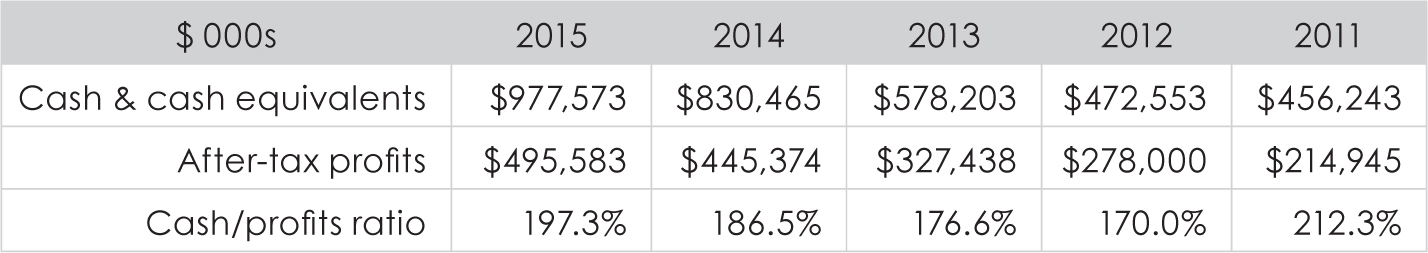

Ultimately, though, the strength of the Chipotle brand is demonstrated by the growth of earnings per share in 2015:

Ten percent is a dramatic decline from the 20 to 35 percent increases in the previous years. But in a year when everything went wrong for the company, it still increased earnings per share. And 10.2 percent is a number a majority of companies would be happy to have.

The Customer Experience

Ultimately, the health of every business depends on the customer experience. The higher its quality, the higher will be customer loyalty and repeat business. Repeat business that comes with zero marketing cost.

Doing it yourself is indubitably the best way to evaluate a company’s customer experience. That way, you can get a personal feel for the quality and consistency of service across different locations.

But if you can’t, you must rely on other people’s comments. And if you don’t have friends or relatives you can turn to, then what?

Here, the Internet is invaluable. While nothing beats being there yourself, sites such as yelp.com provide an incredible variety of customer reactions. More than you’re ever likely to get by relying on people you know.

Chipotle’s financial results are evidence of a good customer experience, but precisely how good is something they can’t and won’t tell us.

Skimming various yelp.com reviews, I came up with the following conclusions about Chipotle’s customer experience:

1. Chipotle is receiving five-star write-ups even after the E. coli outbreaks. For example, this review posted on 10 January 2016 about a Chipotle store in San Jose, California:

With the recent outbreak of E. coli related news I was a little skeptical to revisit my all time favorite chain: Chipotle. However, everyone has to die from something and if I’m going to be living in constant fear of sickness then I’ll be missing out big time.

Burrito bowl with double meat, brown rice, black beans, and tons of lettuce is definitely the best post workout meal you can get so quickly and at such an affordable price.

Also the plus side is that Chipotle lines are now shorter.28

2. Many negative reviews come from people who just don’t like Chipotle’s food. Not their cup of tea, so to speak.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Not everybody loves Chipotle. And not everybody will love your business, either.

3. Service issues that should not be happening. One example:

This one [Champaign, Illinois] is always running out of stuff. The beans always look like they have been there all day. That being said, it’s Chipotle! It’s awesome anyway. I love Chipotle, Chipotle is my life! [Even so, this customer gave Chipotle four stars—on 7 January 2016. Emphasis added.]29

“Always running out of stuff” suggests a supply-chain problem. A (one-star) comment about the same store from a year earlier:

Worst Chipotle experience I’ve ever had, which sucked, because I love Chipotle. Poor / lethargic / disinterested customer service. No chips or fajita veggies. Skimped portions served. Wish I had a better experience because I inevitably feel guilty for being so harsh, but maybe it’ll kickstart a more enthusiastic team?

Another one-star review (6 May 2015) of a Chipotle in Hawthorne, California, suggests this may not be an isolated problem:

Worst Chipotle I have seen.

The first thing you notice is the line. And it never moves because at the end of it are the slowest, laziest, chattiest group of employees you’ve ever seen.…

Today I waited 20 min before they advised everyone that they had failed to cook enough beef, chicken or steak, and that it would be “veggies only” or face another 15-20 min wait.…

Move on. Time to find another burrito joint. Lazy, slow staff who spend more time chatting amongst themselves than they do making food.

Seriously—2pm on a Saturday afternoon and this clown of a manager has no food.30

A four-star review (4 January 2016) from the same store tells an opposite story:

I’ve visited this Chipotle a few times. Frankly, this is one of the better Chipotles I’ve visited for many reasons.…

Very friendly and fast. They got my order correctly, and precisely.

This is also one of the locations with the friendliest staff, and they never repeat or ask the same questions what you’d like in your order.…

I really don’t have complaints for this location, as it tastes fresh, and always delicious.

Overall grade: A.

This is beginning to paint a picture of serious inconsistencies between different Chipotle outlets, and even at the same outlets at different times. Suggesting that while management has established procedures and goals, it has failed to monitor whether they are being regularly achieved.

Even some of those critical reviews come from people who tell us they just love Chipotle. Which is evidence of high customer loyalty. Indeed, some Chipotle customers go so far as to say, “We’re totally willing to throw up a little.”*

I’ll be the first to admit that I am far more intolerant and hypercritical of such outrageous lapses in quality and service than anyone else I know.

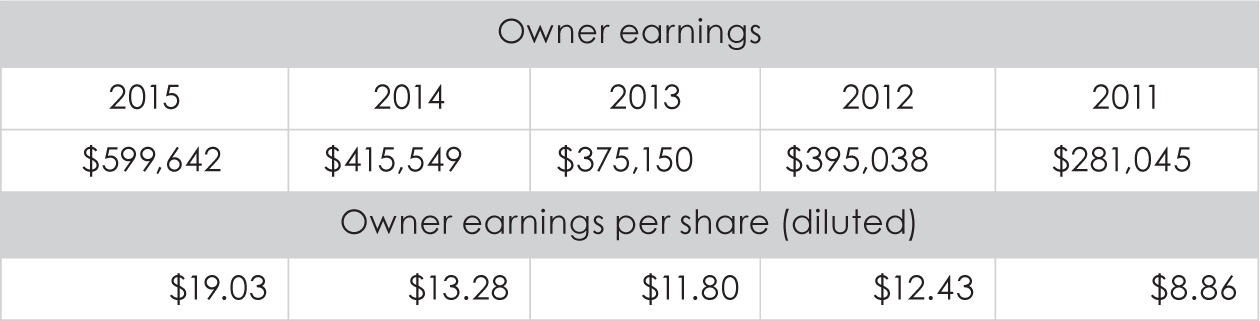

Clearly, as Chipotle’s rapid expansion and 20 percent–plus growth rate in owner earnings demonstrate (numbers that are tough to argue with), plenty of Chipotle’s customers are willing to give it a free pass when the quality of service is nowhere near the company’s expressed standards.

Nevertheless, to me this is a red flag, which—subject to further research—suggests that were Chipotle’s management to address this issue, it could grow even faster by retaining customers it is currently losing.

Or, it could represent a deeper problem. For example, Chipotle has grown too rapidly, with the result that management is spread too thin. Similar, perhaps, to the deterioration of the Starbucks experience from 2000 to 2008.

Whatever the actual cause, it seems I am not alone in coming to this conclusion. As this four-star review (Escondido, California, 20 November 2015) affirms:

I am a big Chipotle Fan. My gripe with the missing star is INCONSISTENCY. From service to portions—especially portions, you just don’t know what you’re going to get. I have to blame management—or lack thereof, which is too bad because I love to eat here.31

Chipotle International

A big driver of growth for most American fast-food chains has been international expansion. Chipotle is following this model—but slowly and without (yet) dramatic success.

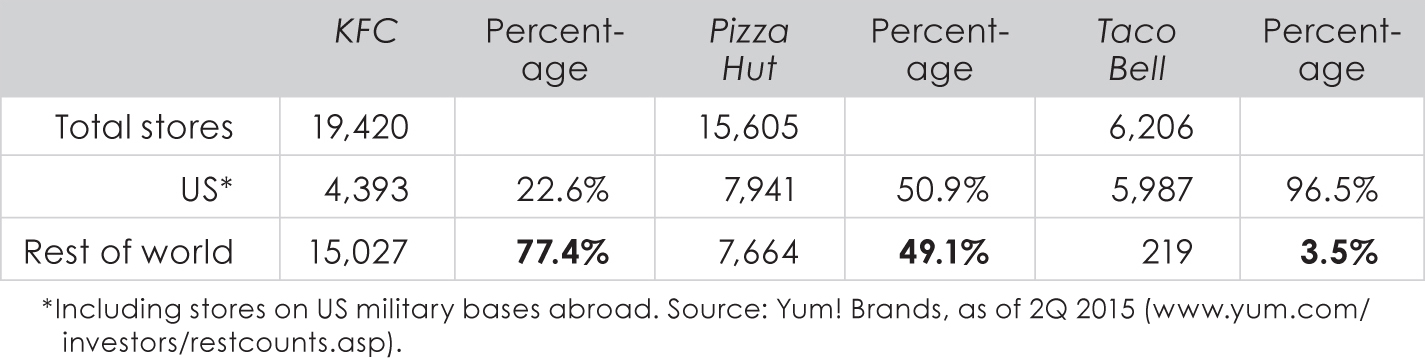

At the end of 2015, Canada had 7 Chipotles, the UK 7, France 3, and Germany 1. This compares to 1,755 in the United States.

Given that the first Canadian Chipotle was opened in Toronto in August 2008 and London was entered in May 2010, the rate of international expansion is not impressive.

But how to judge?

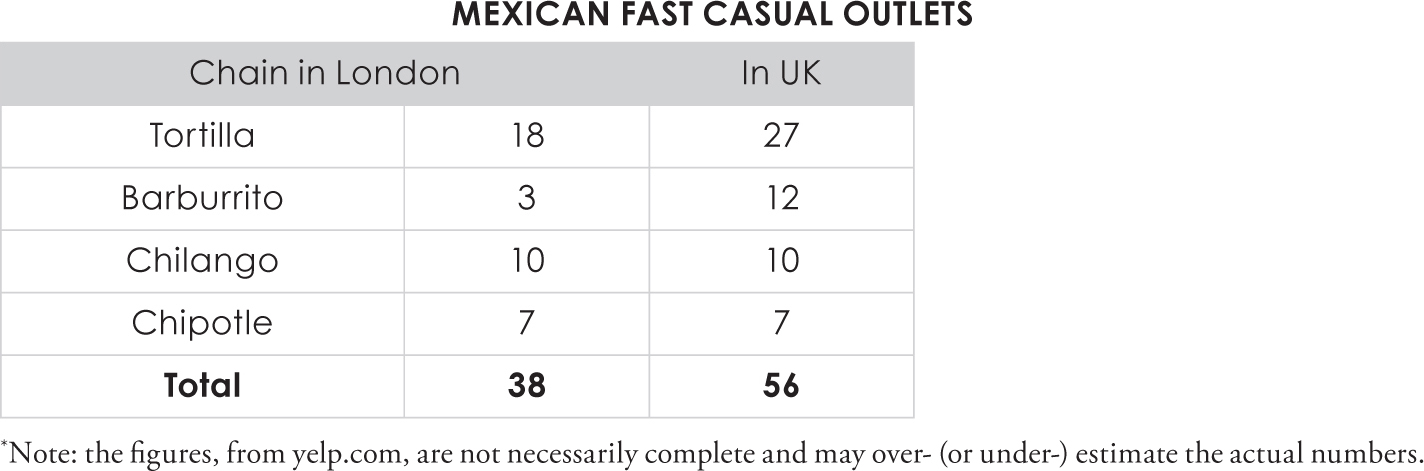

As Chipotle does not break out its international operations in its annual reports, we must find some way of estimating its international performance.