. The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.

. The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.8.6. Nonlinear Waves in Shallow and Deep Water

In the first five sections of this chapter, the wave slope has been assumed to be small enough so that neglect of higher-order terms in the Bernoulli equation and application of the boundary conditions at z = 0 instead of at the free surface z = η are acceptable approximations. One consequence of such linear analysis has been that shallow-water waves of arbitrary shape propagate unchanged in form. The unchanging form results from the fact that all wavelengths composing the initial waveform propagate at the same speed, c = (gH)1/2, provided all the sinusoidal components satisfy the shallow-water and linear wave approximations kH ≪ 1, and ka ≪ 1, respectively. Such waveform invariance no longer occurs if finite amplitude effects are considered. This and several other nonlinear effects are discussed in this section.

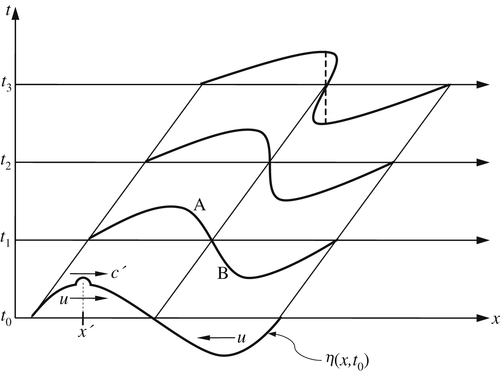

Finite amplitude effects in gas dynamics can be formally treated by the method of characteristics; this is discussed, for example, in Liepmann and Roshko (1957) and Lighthill (1978). Instead, a qualitative approach is initially adopted here. Consider a finite amplitude surface displacement consisting of a wave crest and trough, propagating in shallow-water of undisturbed depth H (Figure 8.20). Let a little wavelet be superposed on the crest at point x', at which the water depth is H′ and the fluid velocity due to the wave motion is u(x'). Relative to an observer moving with the fluid velocity u, the wavelet propagates at the local shallow-water speed c ′ = g H ′  . The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.

. The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.

. The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.

. The speed of the wavelet relative to a frame of reference fixed in the undisturbed fluid is therefore c = c′ + u. It is apparent that the local wave speed c is no longer constant because c′(x) and u(x) are variables. This is in contrast to the linearized theory in which u is negligible and c′ is constant because H′ ≈ H.

Figure 8.20 Finite-amplitude surface wave profiles at four successive times. When the wave amplitude is large enough, the fluid velocity below a crest or trough may be an appreciable fraction of the phase speed. This will cause wave crests to overtake wave troughs and will steepen the compressive portion of the wave (section A-B at time t1). As this steepening continues, the wave-compression surface slope may become very large (t2), or the wave may overturn and become a plunging breaker (t3). Depending on the dynamics of the actual wave, the conditions shown at t2 and t3 may or may not occur since additional nonlinear processes (not described here) may contribute to the wave’s evolution after t1. When the waves are longitudinal (as in one-dimensional gas dynamics), the waveform at t2 would represent a nascent shockwave, while the wave waveform at t3 would represent a fully formed shockwave and would follow the dashed line to produce a single-valued profile.

Let us now examine the effect of variable phase speed on the wave profile. The value of c′ is larger for points near the wave crest than for points in the wave trough. From Figure 8.5 we also know that the fluid velocity u is positive (i.e., in the direction of wave propagation) under a wave crest and negative under a trough. It follows that wave speed c is larger for points on the crest than for points on the trough, so that the waveform deforms as it propagates, the crest region tending to overtake the trough region (Figure 8.20).

We shall call the front face AB a compression region because the surface here is rising with time and this implies an increase in pressure at any depth within the liquid. Figure 8.20 shows that the net effect of nonlinearity is a steepening of the compression region. For finite amplitude waves in a non-dispersive medium like shallow water, therefore, there is an important distinction between compression and expansion regions. A compression region tends to steepen with time, while an expansion region tends to flatten out. This eventually would lead to the wave shape shown at the top of Figure 8.20, where there are three values of surface elevation at a point. While this situation is certainly possible for time-evolving waves and is readily observed as plunging breakers develop in the surf zone along ocean coastlines, the actual wave dynamics of such a situation lie beyond the scope of this discussion. However, even before the formation of a plunging breaker, the wave slope becomes infinite (profile at t2 in Figure 8.20), so that additional physical processes including wave breaking, air entrainment, and foaming become important, and the current ideal flow analysis becomes inapplicable. Once the wave has broken, it takes the form of a front that propagates into still fluid at a constant speed that lies between g H 1  and

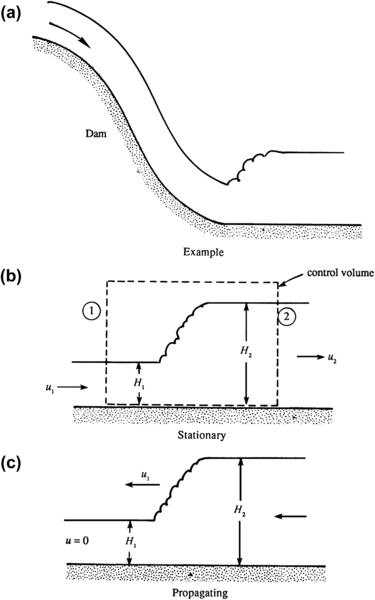

and g H 2  where H1 and H2 are the water depths on the two sides of the front (Figure 8.21). Such a wave is called a hydraulic jump, and it is similar to a shockwave in a compressible flow. Here it should be noted that the t3 wave profile shown in Figure 8.20 is not possible for longitudinal gas-dynamic compression waves. Such a profile instead leads to a shockwave with a front shown by the dashed line.

where H1 and H2 are the water depths on the two sides of the front (Figure 8.21). Such a wave is called a hydraulic jump, and it is similar to a shockwave in a compressible flow. Here it should be noted that the t3 wave profile shown in Figure 8.20 is not possible for longitudinal gas-dynamic compression waves. Such a profile instead leads to a shockwave with a front shown by the dashed line.

and

and  where H1 and H2 are the water depths on the two sides of the front (Figure 8.21). Such a wave is called a hydraulic jump, and it is similar to a shockwave in a compressible flow. Here it should be noted that the t3 wave profile shown in Figure 8.20 is not possible for longitudinal gas-dynamic compression waves. Such a profile instead leads to a shockwave with a front shown by the dashed line.

where H1 and H2 are the water depths on the two sides of the front (Figure 8.21). Such a wave is called a hydraulic jump, and it is similar to a shockwave in a compressible flow. Here it should be noted that the t3 wave profile shown in Figure 8.20 is not possible for longitudinal gas-dynamic compression waves. Such a profile instead leads to a shockwave with a front shown by the dashed line.To analyze a hydraulic jump, consider the flow in a shallow canal of depth H. If the flow speed is u, we may define a dimensionless speed via the Froude number, Fr:

(4.104)

(4.104)

The Froude number is analogous to the Mach number in compressible flow. The flow is called supercritical if Fr > 1, and subcritical if Fr < 1. For the situation shown in Figure 8.21b, where the jump is stationary, the upstream flow is supercritical while the downstream flow is subcritical, just as a compressible flow changes from supersonic to subsonic by going through a shockwave (see Chapter 15). The depth of flow is greater downstream of a hydraulic jump, just as the gas pressure is greater downstream of a shockwave. However, dissipative processes act within shockwaves and hydraulic jumps so that mechanical energy is converted into thermal energy in both cases. An example of a stationary hydraulic jump is found at the foot of a dam, where the flow almost always reaches a supercritical state because of the freefall (Figure 8.21a). A tidal bore propagating into a river mouth is an example of a propagating hydraulic jump. A circular hydraulic jump can be made by directing a vertically falling water stream onto a flat horizontal surface (Exercise 4.25).

Figure 8.21 Schematic cross-section drawings of hydraulic jumps. (a) A stationary hydraulic jump formed at the bottom of a damn’s spillway. (b) A stationary hydraulic jump and a stationary rectangular control volume with vertical inlet surface (1) and vertical outlet surface (2). (c) A hydraulic jump moving into a quiescent fluid layer of depth H1. The flow speed behind the jump is non-zero.

The planar hydraulic jump shown in cross-section in Figure 8.21b can be analyzed by using the dashed control volume shown, the goal being to determine how the depth ratio depends on the upstream Froude number. As shown, the depth rises from H1 to H2 and the velocity falls from u1 to u2. If the velocities are uniform through the depth and Q is the volume flow rate per unit width normal to the plane of the paper, then mass conservation requires:

where the left-hand terms come from the outlet and inlet momentum fluxes, and the right-hand terms are the hydrostatic pressure forces. Substituting u1 = Q/H1 and u2 = Q/H2 on the right side yields:

(8.80)

(8.80)

After canceling out a common factor of H1 – H2, this can be rearranged to find:

where Fr 1 2 = Q 2 / g H 1 3 = u 1 2 / g H 1  . The physically meaningful solution is:

. The physically meaningful solution is:

. The physically meaningful solution is:

. The physically meaningful solution is: (8.81)

(8.81)

For supercritical flows Fr1 > 1, for which (8.81) requires that H2 > H1, and this verifies that water depth increases through a hydraulic jump.

Although a solution with H2 < H1 for Fr1 < 1 is mathematically allowed, such a solution violates the second law of thermodynamics, because it implies an increase of mechanical energy through the jump. To see this, consider the mechanical energy of a fluid particle at the surface, E = u2/2 + gH = Q2/2H2 + gH. Using this definition of E and eliminating Q by using (8.80) leads to:

This shows that H2 < H1 implies E2 > E1, which violates the second law of thermodynamics. The mechanical energy, in fact, decreases in a hydraulic jump because of the action of viscosity.

Hydraulic jumps are not limited to air-water interfaces and may also appear at density interfaces in a stratified fluid, in the laboratory as well as in the atmosphere and the ocean. (For example, see Turner, 1973, Figure 3.11, for a photograph of an internal hydraulic jump on the lee side of a mountain.)

In a non-dispersive medium, nonlinear effects may continually accumulate until they become large changes. Such an accumulation is prevented in a dispersive medium because the different Fourier components propagate at different speeds and tend to separate from each other. In a dispersive system, then, nonlinear steepening could cancel out the dispersive spreading, resulting in finite amplitude waves of constant form. This is indeed the case. A brief description of the phenomenon is given here; further discussion can be found in Whitham (1974), Lighthill (1978), and LeBlond and Mysak (1978).

In 1847 Stokes showed that periodic waves of finite amplitude are possible in deep water. In terms of a power series in the amplitude a, he showed that the surface deflection of irrotational waves in deep water is given by:

(8.82)

(8.82)

where the speed of propagation is:

(8.83)

(8.83)

Equation (8.82) shows the first three terms in a Fourier series for the waveform η. The addition of Fourier components of different wavelengths in (8.82) shows that the wave profile η is no longer exactly sinusoidal. The arguments in the cosine terms show that all the Fourier components propagate at the same speed c, so that the wave profile propagates unchanged in time. It has now been established that the existence of periodic wave trains of unchanging form is a typical feature of nonlinear dispersive systems. Another important result, generally valid for nonlinear systems, is that the wave speed depends on the amplitude, as in (8.83).

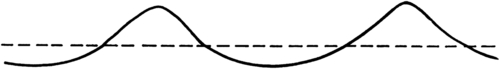

Periodic finite-amplitude irrotational waves in deep water are frequently called Stokes waves. They have flattened troughs and peaked crests (Figure 8.22). The maximum possible amplitude is amax = 0.07λ, at which point the crest becomes a sharp 120° angle. Attempts at generating waves of larger amplitude result in the appearance of foam (white caps) at these sharp crests.

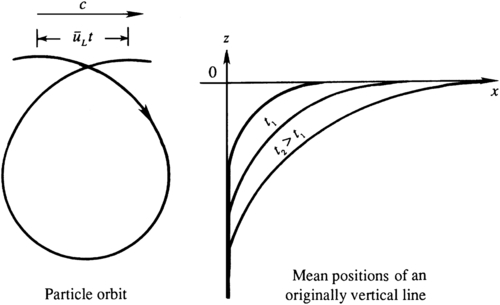

When finite amplitude waves are present, fluid particles no longer trace closed orbits, but undergo a slow drift in the direction of wave propagation. This is called Stokes drift. It is a second-order or finite-amplitude effect that causes fluid particle orbits to no longer close and instead take a shape like that shown in Figure 8.23. The mean velocity of a fluid particle is therefore not zero, although the mean velocity at a fixed point in space must be zero if the wave motion is periodic. The drift occurs because the particle moves forward faster when at the top of its trajectory than it does backward when at the bottom of its trajectory.

To find an expression for the Stokes drift, start from the path-line equations (8.32) for the fluid particle trajectory xp(t) = xp(t)ex + zp(t)ez, but this time include first-order variations in the u and w fluid velocities via a first-order Taylor series in ξ = xp – x0, and ζ = zp – z0:

(8.84a)

(8.84a)

(8.84b)

(8.84b)

where (x0, z0) is the fluid element location in the absence of wave motion. The Stokes drift is the time average of (8.84a). However, the time average of u(x0, z0, t) is zero; thus, the Stokes drift is given by the time average of the next two terms of (8.84a). These terms were neglected in the fluid particle trajectory analysis in Section 8.2, and the result was closed orbits.

Figure 8.23 The Stokes drift. The drift velocity u ¯ L  is a finite-amplitude effect and occurs because near-surface fluid particle paths are no longer closed orbits. The mean position of an initially vertical line of fluid particles extending downward from the liquid surface will increasingly bend in the direction of wave propagation with increasing time.

is a finite-amplitude effect and occurs because near-surface fluid particle paths are no longer closed orbits. The mean position of an initially vertical line of fluid particles extending downward from the liquid surface will increasingly bend in the direction of wave propagation with increasing time.

is a finite-amplitude effect and occurs because near-surface fluid particle paths are no longer closed orbits. The mean position of an initially vertical line of fluid particles extending downward from the liquid surface will increasingly bend in the direction of wave propagation with increasing time.

is a finite-amplitude effect and occurs because near-surface fluid particle paths are no longer closed orbits. The mean position of an initially vertical line of fluid particles extending downward from the liquid surface will increasingly bend in the direction of wave propagation with increasing time.For deep-water gravity waves, the Stokes drift speed u ¯ L  can be estimated by evaluating the time average of (8.84a) using (8.47) to produce:

can be estimated by evaluating the time average of (8.84a) using (8.47) to produce:

can be estimated by evaluating the time average of (8.84a) using (8.47) to produce:

can be estimated by evaluating the time average of (8.84a) using (8.47) to produce: (8.85)

(8.85)

which is the Stokes drift speed in deep water. Its surface value is a2ωk, and the vertical decay rate is twice that for the fluid velocity components. It is therefore confined very close to the sea surface. For arbitrary water depth, (8.85) may be generalized to:

(8.86)

(8.86)

(Exercise 8.15). As might be expected, the vertical component of the Stokes drift is zero.

The Stokes drift causes mass transport in the fluid so it is also called the mass transport velocity. A vertical column of fluid elements marked by some dye gradually bend near the surface (Figure 8.23). In spite of this mass transport, the mean fluid velocity at any point that resides within the liquid for the entire wave period is exactly zero (to any order of accuracy), if the flow is irrotational. This follows from the condition of irrotationality ∂u/∂z = ∂w/∂x, a vertical integral of which gives:

showing that the mean of u is proportional to the mean of ∂w/∂x over a wavelength, which is zero for periodic flows.

There also exits a variety of wave analyses for specialized circumstances that involve dispersion, nonlinearity, and viscosity to varying degrees. So, before moving on to internal waves, one of the classical examples of this type of specialization is presented here for nonlinear waves that are slightly dispersive. In 1895 Korteweg and de Vries showed that waves with λ/H in the range between 10 and 20 satisfy:

(8.87)

(8.87)

where c 0 = g H .  This is the Korteweg–de Vries equation. The first two terms are linear and non-dispersive. The third term is nonlinear and represents finite amplitude effects. The fourth term is linear and results from weak dispersion due to the water depth not being shallow enough. If the nonlinear term in (8.87) is neglected, then setting η = acos(kx − ωt) leads to the dispersion relation c = c0 (1 − (1/6)k2H2). This agrees with the first two terms in the Taylor series expansion of c2 = (g/k) tanh(kH) for small kH, verifying that weak dispersive effects are indeed properly accounted for by the last term in (8.87).

This is the Korteweg–de Vries equation. The first two terms are linear and non-dispersive. The third term is nonlinear and represents finite amplitude effects. The fourth term is linear and results from weak dispersion due to the water depth not being shallow enough. If the nonlinear term in (8.87) is neglected, then setting η = acos(kx − ωt) leads to the dispersion relation c = c0 (1 − (1/6)k2H2). This agrees with the first two terms in the Taylor series expansion of c2 = (g/k) tanh(kH) for small kH, verifying that weak dispersive effects are indeed properly accounted for by the last term in (8.87).

This is the Korteweg–de Vries equation. The first two terms are linear and non-dispersive. The third term is nonlinear and represents finite amplitude effects. The fourth term is linear and results from weak dispersion due to the water depth not being shallow enough. If the nonlinear term in (8.87) is neglected, then setting η = acos(kx − ωt) leads to the dispersion relation c = c0 (1 − (1/6)k2H2). This agrees with the first two terms in the Taylor series expansion of c2 = (g/k) tanh(kH) for small kH, verifying that weak dispersive effects are indeed properly accounted for by the last term in (8.87).

This is the Korteweg–de Vries equation. The first two terms are linear and non-dispersive. The third term is nonlinear and represents finite amplitude effects. The fourth term is linear and results from weak dispersion due to the water depth not being shallow enough. If the nonlinear term in (8.87) is neglected, then setting η = acos(kx − ωt) leads to the dispersion relation c = c0 (1 − (1/6)k2H2). This agrees with the first two terms in the Taylor series expansion of c2 = (g/k) tanh(kH) for small kH, verifying that weak dispersive effects are indeed properly accounted for by the last term in (8.87).The ratio of nonlinear and dispersion terms in (8.87) is:

When aλ2/H3 is larger than ∼16, nonlinear effects sharpen the forward face of the wave, leading to a hydraulic jump, as discussed earlier in this section. For lower values of aλ2/H3, a balance can be achieved between nonlinear steepening and dispersive spreading, and waves of unchanging form become possible.

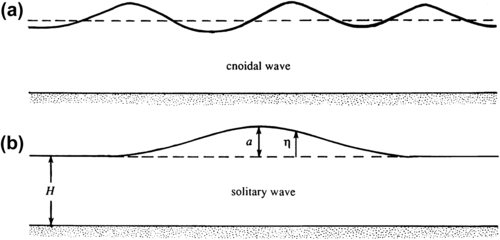

Analysis of the Korteweg–de Vries equation shows that two types of solutions are then possible – a periodic solution and a solitary wave solution. The periodic solution is called a cnoidal wave, because it is expressed in terms of elliptic functions denoted by cn(x). Its waveform is shown in Figure 8.24. The other possible solution of the Korteweg–de Vries equation involves only a single wave crest and is called a solitary wave or soliton. Its profile is given by:

(8.88)

(8.88)

showing that the propagation velocity increases with amplitude. The validity of (8.88) can be checked by substitution into (8.87) (Exercise 8.16). The waveform of the solitary wave is shown in Figure 8.24.

Figure 8.24 Finite-amplitude waves of unchanging form: (a) cnoidal waves and (b) a solitary wave. In both cases, the processes of nonlinear steepening and dispersive spreading balance so that the waveform is unchanged.

An isolated single-hump water wave propagating at constant speed with unchanging form and in fairly shallow water was first observed experimentally by S. Russell in 1844. Solitons have been observed to exist not only as surface waves, but also as internal waves in stratified fluids, in the laboratory as well as in the ocean (see Turner, 1973, Figure 3.3).