Exercises

4.1. Let a one-dimensional velocity field be u = u(x, t), with v = 0 and w = 0. The density varies as ρ = ρ0(2 − cosωt). Find an expression for u(x, t) if u(0, t) = U.

4.2. Consider the one-dimensional Cartesian velocity field: u = ( α x / t , 0,0 )  where α is a constant.

where α is a constant.

where α is a constant.

where α is a constant.a) Find a spatially uniform, time-dependent density field, ρ = ρ(t), that renders this flow field mass conserving when ρ = ρo at t = to.

b) What are the unsteady (∂u/∂t), advective ([ u · ∇ ] u  ), and particle (Du/Dt) accelerations in this flow field? What does α = 1 imply?

), and particle (Du/Dt) accelerations in this flow field? What does α = 1 imply?

), and particle (Du/Dt) accelerations in this flow field? What does α = 1 imply?

), and particle (Du/Dt) accelerations in this flow field? What does α = 1 imply?4.3. Find a nonzero density field ρ(x,y,z,t) that renders the following Cartesian velocity fields mass conserving. Comment on the physical significance and uniqueness of your solutions.

a) u = ( U sin ( ω t − k x ) , 0,0 )  where U, ω, k are positive constants

where U, ω, k are positive constants

where U, ω, k are positive constants

where U, ω, k are positive constants [Hint: exchange the independent variables x,t for a single independent variable ξ = ωt – kx]

b) u = ( − Ω y , + Ω x , 0 )  with Ω = constant [Hint: switch to cylindrical coordinates.]

with Ω = constant [Hint: switch to cylindrical coordinates.]

with Ω = constant [Hint: switch to cylindrical coordinates.]

with Ω = constant [Hint: switch to cylindrical coordinates.]c) u = ( A / x , B / y , C / z )  where A, B, C are constants

where A, B, C are constants

where A, B, C are constants

where A, B, C are constants4.4. A proposed conservation law for ξ, a new fluid property, takes the following form: d d t ( ∫ V ( t ) ρ ξ d V ) + ∫ A ( t ) Q · n d S = 0  , where V(t) is a material volume that moves with the fluid velocity u, A(t) is the surface of V(t), ρ is the fluid density, and

, where V(t) is a material volume that moves with the fluid velocity u, A(t) is the surface of V(t), ρ is the fluid density, and Q = − ρ γ ∇ ξ  .

.

, where V(t) is a material volume that moves with the fluid velocity u, A(t) is the surface of V(t), ρ is the fluid density, and

, where V(t) is a material volume that moves with the fluid velocity u, A(t) is the surface of V(t), ρ is the fluid density, and  .

.a) What partial differential equation is implied by the above conservation statement?

b) Use the part a) result and the continuity equation to show: ( ∂ ξ / ∂ t ) + u · ∇ ξ = ( 1 / ρ ) ∇ · ( ρ γ ∇ ξ )  .

.

.

.4.5. The components of a mass flow vector ρu are ρu = 4x2y, ρv = xyz, pw = yz2.

a) Compute the net mass outflow through the closed surface formed by the planes x = 0, x = 1, y = 0, y = 1, z = 0, z = 1.

b) Compute ∇ · ( ρ u )  and integrate over the volume bounded by the surface defined in part a).

and integrate over the volume bounded by the surface defined in part a).

and integrate over the volume bounded by the surface defined in part a).

and integrate over the volume bounded by the surface defined in part a).c) Explain why the results for parts a) and b) should be equal or unequal.

4.6. Consider a simple fluid mechanical model for the atmosphere of an ideal spherical star that has a surface gas density of ρo and a radius ro. The escape velocity from the surface of the star is ve. Assume that a tenuous gas leaves the star’s surface radially at speed vo uniformly over the star’s surface. Use the steady continuity equation for the gas density ρ and fluid velocity u = ( u r , u θ , u φ )  in spherical coordinates:

in spherical coordinates:

in spherical coordinates:

in spherical coordinates:

for the following items.

a) Determine ρ when v o ≥ v e so that u = ( u r , u θ , u φ ) = ( v o 1 − ( v e 2 / v o 2 ) ( 1 − ( r o / r ) ) , 0,0 )  .

.

.

.b) Simplify the result from part a) when v o ≫ v e  so that:

so that: u = ( u r , u θ , u φ ) = ( v o , 0,0 )  .

.

so that:

so that:  .

.c) Simplify the result from part a) when v o = v e  .

.

.

.d) Use words, sketches, or equations to describe what happens when v o < v e  . State any assumptions that you make.

. State any assumptions that you make.

. State any assumptions that you make.

. State any assumptions that you make.4.7. Consider the three-dimensional flow field u i = β x i  or equivalently u = βrer, where β is a constant with units of inverse time, xi is the position vector from the origin, r is the distance from the origin, and

or equivalently u = βrer, where β is a constant with units of inverse time, xi is the position vector from the origin, r is the distance from the origin, and e ˆ r  is the radial unit vector. Find a density field ρ that conserves mass when:

is the radial unit vector. Find a density field ρ that conserves mass when:

or equivalently u = βrer, where β is a constant with units of inverse time, xi is the position vector from the origin, r is the distance from the origin, and

or equivalently u = βrer, where β is a constant with units of inverse time, xi is the position vector from the origin, r is the distance from the origin, and  is the radial unit vector. Find a density field ρ that conserves mass when:

is the radial unit vector. Find a density field ρ that conserves mass when:a) ρ(t) depends only on time t and ρ = ρo at t = 0, and

b) ρ(r) depends only on the distance r and ρ = ρ1 at r = 1 m.

c) Does the sum ρ(t) + ρ(r) also conserve mass in this flow field? Explain your answer.

4.8. The definition of the stream function for two-dimensional, constant-density flow in the x-y plane is: u = − e z × ∇ ψ  , where ez is the unit vector perpendicular to the x-y plane that determines a right-handed coordinate system.

, where ez is the unit vector perpendicular to the x-y plane that determines a right-handed coordinate system.

, where ez is the unit vector perpendicular to the x-y plane that determines a right-handed coordinate system.

, where ez is the unit vector perpendicular to the x-y plane that determines a right-handed coordinate system.a) Verify that this vector definition is equivalent to u = ∂ ψ / ∂ y  and

and v = − ∂ ψ / ∂ x  in Cartesian coordinates.

in Cartesian coordinates.

and

and  in Cartesian coordinates.

in Cartesian coordinates.b) Determine the velocity components in r-θ polar coordinates in terms of r-θ derivatives of ψ.

c) Determine an equation for the z-component of the vorticity in terms of ψ.

4.9. A curve of ψ ( x , y ) = C 1  (= a constant) specifies a streamline in steady two-dimensional, constant-density flow. If a neighboring streamline is specified by

(= a constant) specifies a streamline in steady two-dimensional, constant-density flow. If a neighboring streamline is specified by ψ ( x , y ) = C 2  , show that the volume flux per unit depth into the page between the streamlines equals C2 – C1 when C2 > C1.

, show that the volume flux per unit depth into the page between the streamlines equals C2 – C1 when C2 > C1.

(= a constant) specifies a streamline in steady two-dimensional, constant-density flow. If a neighboring streamline is specified by

(= a constant) specifies a streamline in steady two-dimensional, constant-density flow. If a neighboring streamline is specified by  , show that the volume flux per unit depth into the page between the streamlines equals C2 – C1 when C2 > C1.

, show that the volume flux per unit depth into the page between the streamlines equals C2 – C1 when C2 > C1.4.10. Consider steady two-dimensional incompressible flow in r-θ polar coordinates where u = ( u r , u θ )  ,

, u r = + ( Λ / r 2 ) cos θ  , and Λ is positive constant. Ignore gravity.

, and Λ is positive constant. Ignore gravity.

,

,  , and Λ is positive constant. Ignore gravity.

, and Λ is positive constant. Ignore gravity.a) Determine the simplest possible u θ  .

.

.

.b) Show that the simplest stream function for this flow is ψ = ( Λ / r ) sin θ  .

.

.

.c) Sketch the streamline pattern. Include arrowheads to show stream direction(s).

d) If the flow is frictionless and the pressure far from the origin is p∞, evaluate the pressure p(r, θ) on θ = 0 for r > 0 when the fluid density is ρ. Does the pressure increase or decrease as r increases?

4.11. The well-known undergraduate fluid mechanics textbook by Fox et al. (2009) provides the following statement of conservation of momentum for a constant-shape (nonrotating) control volume moving at a nonconstant velocity U = U(t):

Here u r e l = u − U ( t )  is the fluid velocity observed in a frame of reference moving with the control volume while u and U are observed in a nonmoving frame. Meanwhile, (4.17) states this law as

is the fluid velocity observed in a frame of reference moving with the control volume while u and U are observed in a nonmoving frame. Meanwhile, (4.17) states this law as

is the fluid velocity observed in a frame of reference moving with the control volume while u and U are observed in a nonmoving frame. Meanwhile, (4.17) states this law as

is the fluid velocity observed in a frame of reference moving with the control volume while u and U are observed in a nonmoving frame. Meanwhile, (4.17) states this law as

where the replacement b = U has been made for the velocity of the accelerating control surface A∗(t). Given that the two equations above are not identical, determine if these two statements of conservation of fluid momentum are contradictory or consistent.

4.12. A jet of water with a diameter of 8 cm and a speed of 25 m/s impinges normally on a large stationary flat plate. Find the force required to hold the plate stationary. Compare the average pressure on the plate with the stagnation pressure if the plate is 20 times the area of the jet.

4.13. Show that the thrust developed by a stationary rocket motor is F = ρAU2 + A(p − patm), where patm is the atmospheric pressure, and p, ρ, A, and U are, respectively, the pressure, density, area, and velocity of the fluid at the nozzle exit.

4.14. Consider the propeller of an airplane moving with a velocity U1. Take a reference frame in which the air is moving and the propeller [disk] is stationary. Then the effect of the propeller is to accelerate the fluid from the upstream value U1 to the downstream value U2 > U1. Assuming incompressibility, show that the thrust developed by the propeller is given by F = ρ A ( U 2 2 − U 1 2 ) / 2 ,  where A is the projected area of the propeller and ρ is the density (assumed constant). Show also that the velocity of the fluid at the plane of the propeller is the average value U = (U1 + U2)/2. [Hint: The flow can be idealized by a pressure jump of magnitude Δp = F/A right at the location of the propeller. Also apply Bernoulli’s equation between a section far upstream and a section immediately upstream of the propeller. Also apply the Bernoulli equation between a section immediately downstream of the propeller and a section far downstream. This will show that

where A is the projected area of the propeller and ρ is the density (assumed constant). Show also that the velocity of the fluid at the plane of the propeller is the average value U = (U1 + U2)/2. [Hint: The flow can be idealized by a pressure jump of magnitude Δp = F/A right at the location of the propeller. Also apply Bernoulli’s equation between a section far upstream and a section immediately upstream of the propeller. Also apply the Bernoulli equation between a section immediately downstream of the propeller and a section far downstream. This will show that Δ p = ρ ( U 2 2 − U 1 2 ) / 2  .]

.]

where A is the projected area of the propeller and ρ is the density (assumed constant). Show also that the velocity of the fluid at the plane of the propeller is the average value U = (U1 + U2)/2. [Hint: The flow can be idealized by a pressure jump of magnitude Δp = F/A right at the location of the propeller. Also apply Bernoulli’s equation between a section far upstream and a section immediately upstream of the propeller. Also apply the Bernoulli equation between a section immediately downstream of the propeller and a section far downstream. This will show that

where A is the projected area of the propeller and ρ is the density (assumed constant). Show also that the velocity of the fluid at the plane of the propeller is the average value U = (U1 + U2)/2. [Hint: The flow can be idealized by a pressure jump of magnitude Δp = F/A right at the location of the propeller. Also apply Bernoulli’s equation between a section far upstream and a section immediately upstream of the propeller. Also apply the Bernoulli equation between a section immediately downstream of the propeller and a section far downstream. This will show that  .]

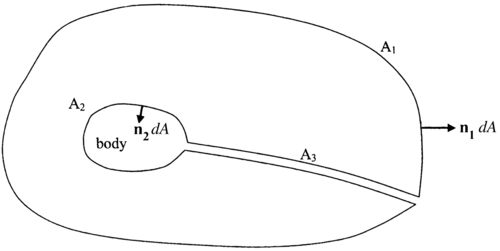

.]4.15. Generalize the control volume analysis of Example 4.4 by considering the control volume geometry shown for steady two-dimensional flow past an arbitrary body in the absence of body forces. Show that the force the fluid exerts on the body is: F j = − ∫ A 1 ( ρ u i u j − T i j ) n i d A  and

and 0 = ∫ A 1 ρ u i n i d A  .

.

and

and  .

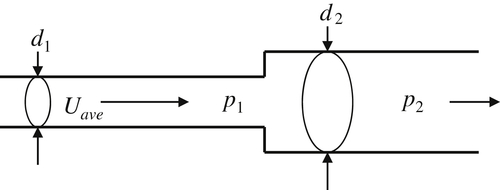

.4.16. The pressure rise Δ p = p 2 − p 1  that occurs for flow through a sudden pipe-cross-sectional-area expansion can depend on the average upstream flow speed Uave, the upstream pipe diameter d1, the downstream pipe diameter d2, and the fluid density ρ and viscosity μ. Here p2 is the pressure downstream of the expansion where the flow is first fully adjusted to the larger pipe diameter.

that occurs for flow through a sudden pipe-cross-sectional-area expansion can depend on the average upstream flow speed Uave, the upstream pipe diameter d1, the downstream pipe diameter d2, and the fluid density ρ and viscosity μ. Here p2 is the pressure downstream of the expansion where the flow is first fully adjusted to the larger pipe diameter.

that occurs for flow through a sudden pipe-cross-sectional-area expansion can depend on the average upstream flow speed Uave, the upstream pipe diameter d1, the downstream pipe diameter d2, and the fluid density ρ and viscosity μ. Here p2 is the pressure downstream of the expansion where the flow is first fully adjusted to the larger pipe diameter.

that occurs for flow through a sudden pipe-cross-sectional-area expansion can depend on the average upstream flow speed Uave, the upstream pipe diameter d1, the downstream pipe diameter d2, and the fluid density ρ and viscosity μ. Here p2 is the pressure downstream of the expansion where the flow is first fully adjusted to the larger pipe diameter.a) Find a dimensionless scaling law for Δp in terms of Uave, d1, d2, ρ, and μ.

b) Simplify the result of part a) for high-Reynolds-number turbulent flow where μ does not matter.

c) Use a control volume analysis to determine Δp in terms of Uave, d1, d2, and ρ for the high Reynolds number limit. [Hints: 1) a streamline drawing might help in determining or estimating the pressure on the vertical surfaces of the area transition, and 2) assume uniform flow profiles wherever possible.]

d) Compute the ideal flow value for Δp and compare this to the result from part c) for a diameter ratio of d1/d2 = ½. What fraction of the maximum possible pressure rise does the sudden expansion achieve?

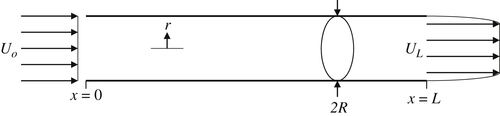

4.17. Consider how pressure gradients and skin friction develop in an empty wind tunnel or water tunnel test section when the flow is incompressible. Here the fluid has viscosity μ and density ρ, and flows into a horizontal cylindrical pipe of length L with radius R at a uniform horizontal velocity Uo. The inlet of the pipe lies at x = 0. Boundary layer growth on the pipe’s walls induces the horizontal velocity on the pipe’s centerline to be UL at x = L; however, the pipe-wall boundary layer thickness remains much smaller than R. Here, L/R is of order 10, and ρUoR/μ ≫ 1. The radial coordinate from the pipe centerline is r.

a) Determine the displacement thickness, δ L ∗  , of the boundary layer at x = L in terms of Uo, UL, and R. Assume that the boundary layer displacement thickness is zero at x = 0. [The boundary layer displacement thickness, δ∗, is the thickness of the zero-flow-speed layer that displaces the outer flow by the same amount as the actual boundary layer. For a boundary layer velocity profile u(y) with y = wall-normal coordinate and U = outer flow velocity, δ∗ is defined by:

, of the boundary layer at x = L in terms of Uo, UL, and R. Assume that the boundary layer displacement thickness is zero at x = 0. [The boundary layer displacement thickness, δ∗, is the thickness of the zero-flow-speed layer that displaces the outer flow by the same amount as the actual boundary layer. For a boundary layer velocity profile u(y) with y = wall-normal coordinate and U = outer flow velocity, δ∗ is defined by: δ ∗ = ∫ 0 ∞ ( 1 − ( u / U ) ) d y  .]

.]

, of the boundary layer at x = L in terms of Uo, UL, and R. Assume that the boundary layer displacement thickness is zero at x = 0. [The boundary layer displacement thickness, δ∗, is the thickness of the zero-flow-speed layer that displaces the outer flow by the same amount as the actual boundary layer. For a boundary layer velocity profile u(y) with y = wall-normal coordinate and U = outer flow velocity, δ∗ is defined by:

, of the boundary layer at x = L in terms of Uo, UL, and R. Assume that the boundary layer displacement thickness is zero at x = 0. [The boundary layer displacement thickness, δ∗, is the thickness of the zero-flow-speed layer that displaces the outer flow by the same amount as the actual boundary layer. For a boundary layer velocity profile u(y) with y = wall-normal coordinate and U = outer flow velocity, δ∗ is defined by:  .]

.]b) Determine the pressure difference, ΔP = PL – Po, between the ends of the pipe in terms of ρ, Uo, and UL.

d) Calculate the skin friction coefficient, c f = τ ¯ w / 1 2 ρ U o 2  , when Uo = 20.0 m/s, UL = 20.5 m/s, R = 1.5 m, L = 12 m, n = 80, and the fluid is water, i.e., ρ = 103 kg/m3.

, when Uo = 20.0 m/s, UL = 20.5 m/s, R = 1.5 m, L = 12 m, n = 80, and the fluid is water, i.e., ρ = 103 kg/m3.

, when Uo = 20.0 m/s, UL = 20.5 m/s, R = 1.5 m, L = 12 m, n = 80, and the fluid is water, i.e., ρ = 103 kg/m3.

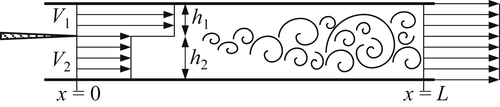

, when Uo = 20.0 m/s, UL = 20.5 m/s, R = 1.5 m, L = 12 m, n = 80, and the fluid is water, i.e., ρ = 103 kg/m3.4.18. An acid solution with density ρ flows horizontally into a mixing chamber at speed V1 at x = 0 where it meets a buffer solution with the same density moving at speed V2. The inlet flow layer thicknesses are h1 and h2 as shown, the mixer chamber height is constant at h1 + h2, and the chamber width into the page is b. Assume steady uniform flow across the two inlets and the outlet. Ignore fluid friction on the interior surfaces of the mixing chamber for parts a) and b).

a) By conserving mass and momentum in a suitable control volume, determine the pressure difference, Δp = p(L) – p(0), between the outlet (x = L) and inlet (x = 0) of the mixing chamber in terms of V1, V2, h1, h2, and ρ. Do not use the Bernoulli equation.

b) Is the pressure at the outlet higher or lower than that at the inlet when V1 ≠ V2?

c) Explain how your answer to a) would be modified by friction on the interior surfaces of the mixing chamber.

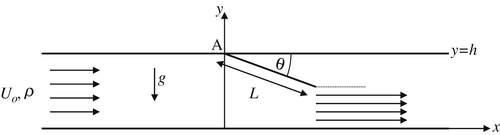

4.19. Consider the situation depicted below. Wind strikes the side of a simple residential structure and is deflected up over the top of the structure. Assume the following: two-dimensional steady inviscid constant-density flow, uniform upstream velocity profile, linear gradient in the downstream velocity profile (velocity U at the upper boundary and zero velocity at the lower boundary as shown), no flow through the upper boundary of the control volume, and constant pressure on the upper boundary of the control volume. Using the control volume shown:

a) determine h2 in terms of U and h1, and

b) determine the direction and magnitude of the horizontal force on the house per unit depth into the page in terms of the fluid density ρ, the upstream velocity U, and the height of the house h1.

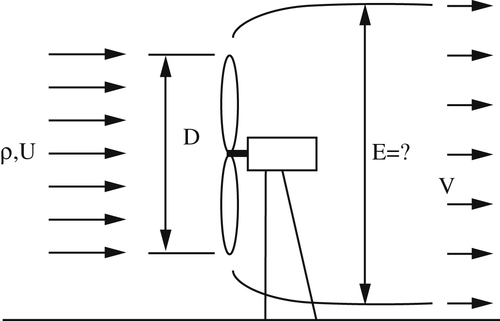

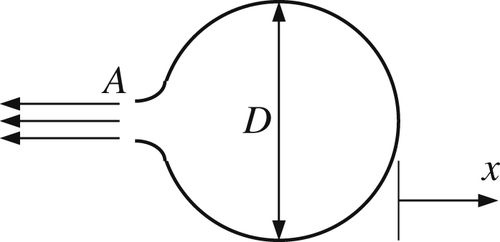

4.20. A large wind turbine with diameter D extracts a fraction η of the kinetic energy from the airstream (density = ρ = constant) that impinges on it with velocity U.

a) What is the diameter of the wake zone, E, downstream of the windmill?

b) Determine the magnitude and direction of the force on the windmill in terms of ρ, U, D, and η.

c) Does your answer approach reasonable limits as η → 0 and η → 1?

4.21. An incompressible fluid of density ρ flows through a horizontal rectangular duct of height h and width b. A uniform flat plate of length L and width b attached to the top of the duct at point A is deflected to an angle θ as shown.

a) Estimate the pressure difference between the upper and lower sides of the plate in terms of x, ρ, Uo, h, L, and θ when the flow separates cleanly from the tip of the plate.

b) If the plate has mass M and can rotate freely about the hinge at A, determine a formula for the angle θ in terms of the other parameters. You may leave your answer in terms of an integral.

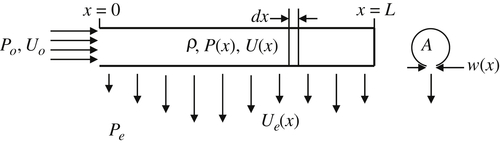

4.22. A pipe of length L and cross sectional area A is to be used as a fluid-distribution manifold that expels a steady uniform volume flux per unit length of an incompressible liquid from x = 0 to x = L. The liquid has density ρ, and is to be expelled from the pipe through a slot of varying width, w(x). The goal of this problem is to determine w(x) in terms of the other parameters of the problem. The pipe-inlet pressure and liquid velocity at x = 0 are Po and Uo, respectively, and the pressure outside the pipe is Pe. If P(x) denotes the pressure on the inside of the pipe, then the liquid velocity through the slot Ue is determined from: P ( x ) − P e = 1 2 ρ U e 2  . For this problem assume that the expelled liquid exits the pipe perpendicular to the pipe’s axis, and note that wUe = const. = UoA/L, even though w and Ue both depend on x.

. For this problem assume that the expelled liquid exits the pipe perpendicular to the pipe’s axis, and note that wUe = const. = UoA/L, even though w and Ue both depend on x.

. For this problem assume that the expelled liquid exits the pipe perpendicular to the pipe’s axis, and note that wUe = const. = UoA/L, even though w and Ue both depend on x.

. For this problem assume that the expelled liquid exits the pipe perpendicular to the pipe’s axis, and note that wUe = const. = UoA/L, even though w and Ue both depend on x.a) Formulate a dimensionless scaling law for w in terms of x, L, A, ρ, Uo, Po, and Pe.

b) Ignore the effects of viscosity, assume all profiles through the cross section of the pipe are uniform, and use a suitable differential-control-volume analysis to show that:

4.23. The take-off mass of a Boeing 747-400 may be as high as 400,000 kg. An Airbus A380 may be even heavier. Using a control volume (CV) that comfortably encloses the aircraft, explain why such large aircraft do not crush houses or people when they fly low overhead. Of course, the aircraft’s wings generate lift but they are entirely contained within the CV and do not coincide with any of the CV’s surfaces; thus merely stating the lift balances weight is not a satisfactory explanation. Given that the CV’s vertical body-force term, − g ∫ C V ρ d V  , will exceed

, will exceed 4 × 10 6  N when the airplane and air in the CV’s interior are included, your answer should instead specify which of the CV’s surface forces or surface fluxes carries the signature of a large aircraft’s impressive weight.

N when the airplane and air in the CV’s interior are included, your answer should instead specify which of the CV’s surface forces or surface fluxes carries the signature of a large aircraft’s impressive weight.

, will exceed

, will exceed  N when the airplane and air in the CV’s interior are included, your answer should instead specify which of the CV’s surface forces or surface fluxes carries the signature of a large aircraft’s impressive weight.

N when the airplane and air in the CV’s interior are included, your answer should instead specify which of the CV’s surface forces or surface fluxes carries the signature of a large aircraft’s impressive weight.4.24. 1An inviscid incompressible liquid with density ρ flows in a wide conduit of height H and width B into the page. The inlet stream travels at a uniform speed U and fills the conduit. The depth of the outlet stream is less than H. Air with negligible density fills the gap above the outlet stream. Gravity acts downward with acceleration g. Assume the flow is steady for the following items.

a) Find a dimensionless scaling law for U in terms of ρ, H, and g.

b) Denote the outlet stream depth and speed by h and u, respectively, and write down a set of equations that will allow U, u, and h to be determined in terms of ρ, H, and g.

c) Solve for U, u, and h in terms of ρ, H, and g. [Hint: solve for h first.]

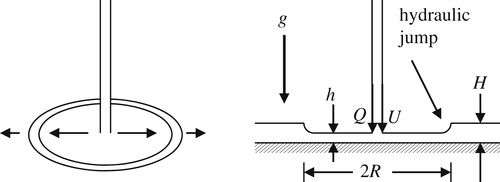

4.25. A hydraulic jump is the shallow-water-wave equivalent of a gas-dynamic shock wave. A steady radial hydraulic jump can be observed safely in one’s kitchen, bathroom, or backyard where a falling stream of water impacts a shallow pool of water on a flat surface. The radial location R of the jump will depend on gravity g, the depth of the water behind the jump H, the volume flow rate of the falling stream Q, and stream’s speed, U, where it impacts the plate. In your work, assume 2 g h ≪ U  where r is the radial coordinate from the point where the falling stream impacts the surface.

where r is the radial coordinate from the point where the falling stream impacts the surface.

where r is the radial coordinate from the point where the falling stream impacts the surface.

where r is the radial coordinate from the point where the falling stream impacts the surface.a) Formulate a dimensionless law for R in terms of the other parameters.

b) Use the Bernoulli equation and a control volume with narrow angular and negligible radial extents that contains the hydraulic jump to show that:

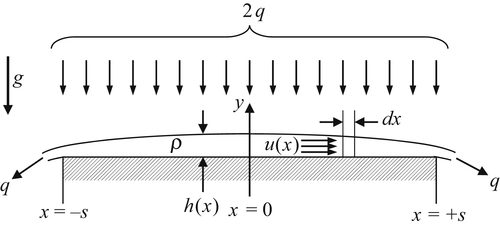

4.26. A fine uniform mist of an inviscid incompressible fluid with density ρ settles steadily at a total volume flow rate (per unit depth into the page) of 2q onto a flat horizontal surface of width 2s to form a liquid layer of thickness h(x) as shown. The geometry is two dimensional.

a) Formulate a dimensionless scaling law for h in terms of x, s, q, ρ, and g.

b) Use a suitable control volume analysis, assuming u(x) does not depend on y, to find a single cubic equation for h(x) in terms of h(0), s, q, x, and g.

c) Determine h(0).

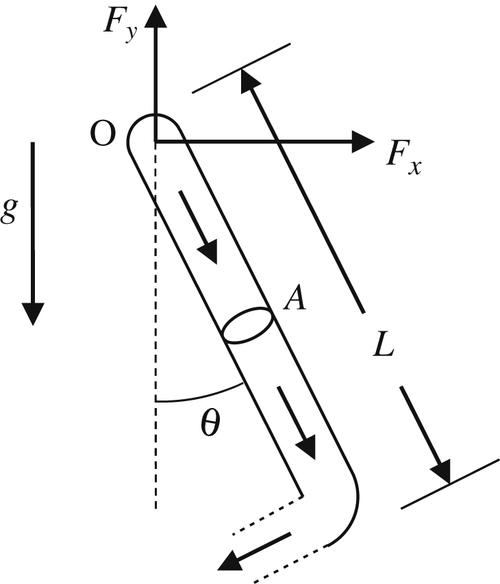

4.27. A thin-walled pipe of mass mo, length L, and cross-sectional area A is free to swing in the x-y plane from a frictionless pivot at point O. Water with density ρ fills the pipe, flows into it at O perpendicular to the x-y plane, and is expelled at a right angle from the pipe’s end as shown. The pipe’s opening also has area A and gravity g acts downward. For a steady mass flow rate of m ˙  , the pipe hangs at angle θ with respect to the vertical as shown. Ignore fluid viscosity.

, the pipe hangs at angle θ with respect to the vertical as shown. Ignore fluid viscosity.

, the pipe hangs at angle θ with respect to the vertical as shown. Ignore fluid viscosity.

, the pipe hangs at angle θ with respect to the vertical as shown. Ignore fluid viscosity.a) Develop a dimensionless scaling law for θ in terms of mo, L, A, ρ, m ˙  , and g.

, and g.

, and g.

, and g.b) Use a control volume analysis to determine the force components, Fx and Fy, applied to the pipe at the pivot point in terms of θ, mo, L, A, ρ, m ˙  , and g.

, and g.

, and g.

, and g.c) Determine θ in terms of mo, L, A, ρ, m ˙  , and g.

, and g.

, and g.

, and g.d) Above what value of m ˙  will the pipe rotate without stopping?

will the pipe rotate without stopping?

will the pipe rotate without stopping?

will the pipe rotate without stopping?4.28. Construct a house of cards, or light a candle. Get the cardboard tube from the center of a roll of paper towels and back away from the cards or candle a meter or two so that by blowing you cannot knock down the cards or blow out the candle unaided. Now use the tube in two slightly different configurations. First, place the tube snugly against your face encircling your mouth, and try to blow down the house of cards or blow out the candle. Repeat the experiment while moving closer until the cards are knocked down or the candle is blown out (you may need to get closer to your target than might be expected; do not hyperventilate; do not start the cardboard tube on fire). Note the distance between the end of the tube and the card house or candle at this point. Rebuild the card house or relight the candle and repeat the experiment, except this time hold the tube a few centimeters away from your face and mouth, and blow through it. Again, determine the greatest distance from which you can knock down the cards or blow out the candle.

a) Which configuration is more effective at knocking the cards down or blowing the candle out?

b) Explain your findings with a suitable control-volume analysis.

c) List some practical applications where this effect might be useful.

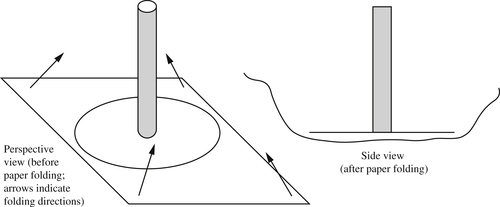

4.29. 2Attach a drinking straw to a 15-cm-diameter cardboard disk with a hole at the center using tape or glue. Loosely fold the corners of a standard piece of paper upward so that the paper mildly cups the cardboard disk (see drawing). Place the cardboard disk in the central section of the folded paper. Attempt to lift the loosely folded paper off a flat surface by blowing or sucking air through the straw.

a) Experimentally determine if blowing or suction is more effective in lifting the folded paper.

b) Explain your findings with a control volume analysis.

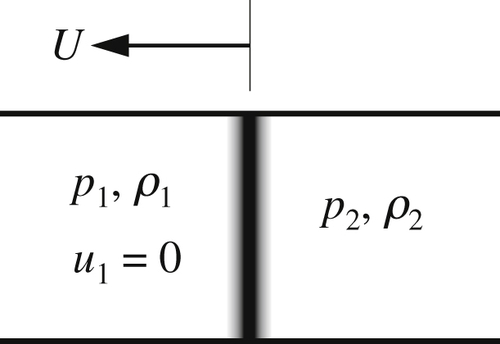

4.30. A compression wave in a long gas-filled constant-area duct propagates to the left at speed U. To the left of the wave, the gas is quiescent with uniform density ρ1 and uniform pressure p1. To the right of the wave, the gas has uniform density ρ2 (>ρ1) and uniform pressure is p2 (>p1). Ignore the effects of viscosity in this problem.

a) Formulate a dimensionless scaling law for U in terms of the pressures and densities.

b) Determine U in terms of ρ1, ρ2, p1, and p2 using a control volume.

c) Put your answer to part b) in dimensionless form and thereby determine the unknown function from part a).

4.31. A rectangular tank is placed on wheels and is given a constant horizontal acceleration a. Show that, at steady state, the angle made by the free surface with the horizontal is given by tanθ = a/g.

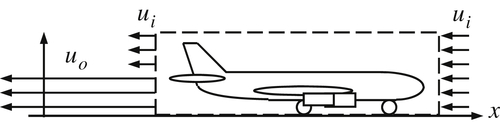

4.32. Starting from rest at t = 0, an airliner of mass M accelerates at a constant rate a = a e x  into a headwind,

into a headwind, u = − u i e x  . For the following items, assume that: 1) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –ui on the front, sides, and back upper half of the control volume (CV), 2) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –uo on the back lower half of the CV, 3) changes in M can be neglected, 4) changes of air momentum inside the CV can be neglected, and 5) frictionless wheels. In addition, assume constant air density ρ and uniform flow conditions exist on the various control surfaces. In your work, denote the CV’s front and back area by A. (This approximate model is appropriate for real commercial airliners that have the engines hung under the wings).

. For the following items, assume that: 1) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –ui on the front, sides, and back upper half of the control volume (CV), 2) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –uo on the back lower half of the CV, 3) changes in M can be neglected, 4) changes of air momentum inside the CV can be neglected, and 5) frictionless wheels. In addition, assume constant air density ρ and uniform flow conditions exist on the various control surfaces. In your work, denote the CV’s front and back area by A. (This approximate model is appropriate for real commercial airliners that have the engines hung under the wings).

into a headwind,

into a headwind,  . For the following items, assume that: 1) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –ui on the front, sides, and back upper half of the control volume (CV), 2) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –uo on the back lower half of the CV, 3) changes in M can be neglected, 4) changes of air momentum inside the CV can be neglected, and 5) frictionless wheels. In addition, assume constant air density ρ and uniform flow conditions exist on the various control surfaces. In your work, denote the CV’s front and back area by A. (This approximate model is appropriate for real commercial airliners that have the engines hung under the wings).

. For the following items, assume that: 1) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –ui on the front, sides, and back upper half of the control volume (CV), 2) the x-component of the fluid velocity is –uo on the back lower half of the CV, 3) changes in M can be neglected, 4) changes of air momentum inside the CV can be neglected, and 5) frictionless wheels. In addition, assume constant air density ρ and uniform flow conditions exist on the various control surfaces. In your work, denote the CV’s front and back area by A. (This approximate model is appropriate for real commercial airliners that have the engines hung under the wings).a) Find a dimensionless scaling law for uo at t = 0 in terms of ui, ρ, a, M, and A.

b) Using a CV that encloses the airliner (as shown) determine a formula for uo(t), the time-dependent air velocity on the lower half of the CV’s back surface.

c) Evaluate uo at t = 0, when M = 4 × 105 kg, a = 2.0 m/s2, ui = 5 m/s, ρ = 1.2 kg/m3, and A = 1200 m2. Would you be able to walk comfortably behind the airliner?

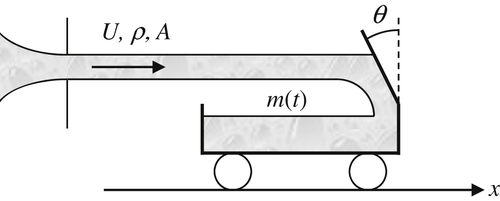

4.33. 3A cart that can roll freely in the x-direction deflects a horizontal water jet into its tank with a vane inclined to the vertical at an angle θ. The jet issues steadily at velocity U with density ρ, and has cross-sectional area A. The cart is initially at rest with a mass of mo. Ignore the effects of surface tension, the cart’s rolling friction, and wind resistance in your answers.

a) Formulate dimensionless law for the mass, m(t), in the cart at time t in terms of t, θ, U, ρ, A, and mo.

b) Formulate a differential equation for m(t).

c) Find a solution for m(t) and put it in dimensionless form.

4.34. A spherical balloon of mass Mb is filled with air of density ρ and is initially stationary at x = 0 with diameter Do. At t = 0, an opening of area A is created and the balloon travels horizontally along the x-axis. The aerodynamic drag force on the balloon is given by (1/2)ρU2π(D/2)2CD, where: CD is a constant, U(t) is the velocity of the balloon, and D(t) is the current diameter of the balloon. Assume incompressible air flow and that D(t) is known.

a) Find a differential equation for U that includes: Mb, ρ, CD, D, and A.

b) Solve the part a) equation when CD = 0, and the mass flow rate of air out of the balloon, m ˙  , is constant, so that the mass of the balloon and its contents are

, is constant, so that the mass of the balloon and its contents are M b + ρ ( π / 6 ) D o 3 − m ˙ t  at time t.

at time t.

, is constant, so that the mass of the balloon and its contents are

, is constant, so that the mass of the balloon and its contents are  at time t.

at time t.c) What is the maximum value of U under the conditions of part b)?

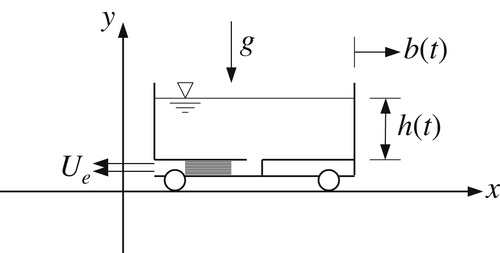

4.35. For time t < 0, a rolling water tank with frictionless wheels, horizontal cross-sectional area A, and empty mass M sits stationary while filled to a depth ho with water of density ρ. At t = 0, the outlet of the tank is opened and the tank starts moving to the right. The outlet tube has cross sectional area a and contains a narrow-passage honeycomb so that the flow speed through the tube is Ue = gh/R, where R is the specific flow resistivity of the honeycomb material, g is the acceleration of gravity, and h(t) is the average water depth in the rolling tank for t > 0. Here, Ue is the leftward speed of the water with respect to the outlet tube; it is independent of the speed b(t) of the rolling tank. Assume uniform flow at the pipe outlet and use an appropriate control volume analysis for the following items.

a) By conserving mass, develop a single equation for h(t) in terms of a, A, g, R, and t.

c) By conserving horizontal momentum, develop a single equation for b(t) in terms of a, A, M, h, ρ, g, and R.

d) Determine for b(t) in terms of a, A, M, ho, ρ, g, R, and t. [Hint: use db/dt = (db/dh)(dh/dt)]

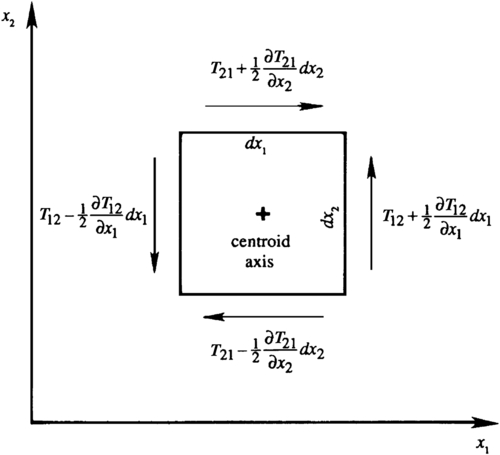

4.36. Prove that the stress tensor is symmetric by considering first-order changes in surface forces on a vanishingly small cube in rotational equilibrium. Work with rotation about the number 3 coordinate axis to show T12 = T21. Cyclic permutation of the indices will suffice for showing the symmetry of the other two shear stresses.

4.37. Obtain an empty plastic milk jug with a cap that seals tightly, and a frying pan. Fill both the pan and jug with water to a depth of approximately 1 cm. Place the jug in the pan with the cap off. Place the pan on a stove and turn up the heat until the water in the frying pan boils vigorously for a few minutes. Turn the stove off, and quickly put the cap tightly on the jug. Avoid spilling or splashing hot water on yourself. Remove the capped jug from the frying pan and let it cool to room temperature. Does anything interesting happen? If something does happen, explain your observations in terms of surface forces. What is the origin of these surface forces? Can you make any quantitative predictions about what happens?

4.38. In cylindrical coordinates (R,φ,z), two components of a steady incompressible viscous flow field are known: u φ = 0  , and

, and u z = − A z  where A is a constant, and body force is zero.

where A is a constant, and body force is zero.

, and

, and  where A is a constant, and body force is zero.

where A is a constant, and body force is zero.a) Determine u R  so that the flow field is smooth and conserves mass.

so that the flow field is smooth and conserves mass.

so that the flow field is smooth and conserves mass.

so that the flow field is smooth and conserves mass.b) If the pressure, p, at the origin of coordinates is Po, determine p(R,φ,z) when the density is constant.

4.39. Consider solid-body rotation of an isothermal perfect gas (with constant R) at temperature T in (r,θ)-plane-polar coordinates: ur = 0, and u θ = Ω z r  , where Ωz is a constant rotation rate and the body force is zero. What is the pressure distribution p(r) if p(0) = patm? If the gas is air at 295 K and the container has a radius of ro = 10 cm, what Ωz is needed to produce p(ro) = 2patm?

, where Ωz is a constant rotation rate and the body force is zero. What is the pressure distribution p(r) if p(0) = patm? If the gas is air at 295 K and the container has a radius of ro = 10 cm, what Ωz is needed to produce p(ro) = 2patm?

, where Ωz is a constant rotation rate and the body force is zero. What is the pressure distribution p(r) if p(0) = patm? If the gas is air at 295 K and the container has a radius of ro = 10 cm, what Ωz is needed to produce p(ro) = 2patm?

, where Ωz is a constant rotation rate and the body force is zero. What is the pressure distribution p(r) if p(0) = patm? If the gas is air at 295 K and the container has a radius of ro = 10 cm, what Ωz is needed to produce p(ro) = 2patm?4.40. Solid body rotation with a constant angular velocity, Ω, is described by the following Cartesian velocity field: u = Ω × x  . For this velocity field:

. For this velocity field:

. For this velocity field:

. For this velocity field:a) Compute the components of:

b) Consider the case of Ω 1 = Ω 2 = 0  ,

, Ω 3 ≠ 0  , ρ = constant, with p = po at x1 = x2 = 0. Use the differential momentum equation in Cartesian coordinates to determine p(r), where

, ρ = constant, with p = po at x1 = x2 = 0. Use the differential momentum equation in Cartesian coordinates to determine p(r), where r 2 = x 1 2 + x 2 2  , when there is no body force and ρ = constant. Does your answer make sense? Can you check it with a simple experiment?

, when there is no body force and ρ = constant. Does your answer make sense? Can you check it with a simple experiment?

,

,  , ρ = constant, with p = po at x1 = x2 = 0. Use the differential momentum equation in Cartesian coordinates to determine p(r), where

, ρ = constant, with p = po at x1 = x2 = 0. Use the differential momentum equation in Cartesian coordinates to determine p(r), where  , when there is no body force and ρ = constant. Does your answer make sense? Can you check it with a simple experiment?

, when there is no body force and ρ = constant. Does your answer make sense? Can you check it with a simple experiment?4.42. 4Air, water, and petroleum products are important engineering fluids and can usually be treated as Newtonian fluids. Consider the following materials and try to classify them as: Newtonian fluid, non-Newtonian fluid, or solid. State the reasons for your choices and note the temperature range where you believe your answers are correct. Simple impact, tensile, and shear experiments in your kitchen or bathroom are recommended. Test and discuss at least five items.

a) toothpaste

b) peanut butter

c) shampoo

d) glass

e) honey

f) mozzarella cheese

g) hot oatmeal

h) creamy salad dressing

i) ice cream

j) silly putty

4.43. The equations for conservation of mass and momentum for a viscous Newtonian fluid are (4.7) and (4.39a) when the viscosities are constant.

a) Simplify these equations and write them out in primitive form for steady constant-density flow in two dimensions where u i = ( u 1 ( x 1 , x 2 ) , u 2 ( x 1 , x 2 ) , 0 )  ,

, p = p ( x 1 , x 2 )  , and gj = 0.

, and gj = 0.

,

,  , and gj = 0.

, and gj = 0.b) Determine p = p ( x 1 , x 2 )  when

when u 1 = C x 1  and

and u 2 = − C x 2  , where C is a positive constant.

, where C is a positive constant.

when

when  and

and  , where C is a positive constant.

, where C is a positive constant.4.44. 5Simplify the planar Navier-Stokes momentum equations (given in Example 4.9) for incompressible flow, constant viscosity, and conservative body forces. Cross differentiate these equations and eliminate the pressure to find a single equation for ωz = ∂v/∂x – ∂u/∂y. What process(es) might lead to the changes in ωz for fluid elements in this flow?

4.45. Starting from (4.7) and (4.39b), derive a Poisson equation for the pressure, p, by taking the divergence of the constant-density momentum equation. [In other words, find an equation where ∂ 2 p / ∂ x j 2  appears by itself on the left side and other terms not involving p appear on the right side]. What role does the viscosity μ play in determining the pressure in constant density flow?

appears by itself on the left side and other terms not involving p appear on the right side]. What role does the viscosity μ play in determining the pressure in constant density flow?

appears by itself on the left side and other terms not involving p appear on the right side]. What role does the viscosity μ play in determining the pressure in constant density flow?

appears by itself on the left side and other terms not involving p appear on the right side]. What role does the viscosity μ play in determining the pressure in constant density flow?4.46. Prove the equality of the two ends of index notation version of (4.40) without leaving index notation or using vector identities.

4.47. The viscous compressible fluid conservation equations for mass and momentum are (4.7) and (4.38). Simplify these equations for constant-density, constant-viscosity flow and where the body force has a potential, g j = − ∂ Φ / ∂ x j  . Assume the velocity field can be found from

. Assume the velocity field can be found from u j = ∂ ϕ / ∂ x j  , where the scalar function ϕ depends on space and time. What are the simplified conservation of mass and momentum equations for ϕ?

, where the scalar function ϕ depends on space and time. What are the simplified conservation of mass and momentum equations for ϕ?

. Assume the velocity field can be found from

. Assume the velocity field can be found from  , where the scalar function ϕ depends on space and time. What are the simplified conservation of mass and momentum equations for ϕ?

, where the scalar function ϕ depends on space and time. What are the simplified conservation of mass and momentum equations for ϕ?4.48. The viscous compressible fluid conservation equations for mass and momentum are (4.7) and (4.38).

a) In Cartesian coordinates (x,y,z) with g = ( g x , 0,0 )  , simplify these equations for unsteady one-dimensional unidirectional flow where:

, simplify these equations for unsteady one-dimensional unidirectional flow where: ρ = ρ ( x , t )  and

and u = ( u ( x , t ) , 0,0 )  .

.

, simplify these equations for unsteady one-dimensional unidirectional flow where:

, simplify these equations for unsteady one-dimensional unidirectional flow where:  and

and  .

.b) If the flow is also incompressible, show that the fluid velocity depends only on time, i.e., u ( x , t ) = U ( t )  , and show that the equations found for part a) reduce to

, and show that the equations found for part a) reduce to

, and show that the equations found for part a) reduce to

, and show that the equations found for part a) reduce to

c) If ρ = ρ o ( x )  at t = 0, and

at t = 0, and u = U ( 0 ) = U o  at t = 0, determine an implicit solutions for

at t = 0, determine an implicit solutions for ρ = ρ ( x , t )  and

and U ( t )  in terms of x, t,

in terms of x, t, ρ o ( x )  , Uo,

, Uo, ∂ p / ∂ x  , and gx.

, and gx.

at t = 0, and

at t = 0, and  at t = 0, determine an implicit solutions for

at t = 0, determine an implicit solutions for  and

and  in terms of x, t,

in terms of x, t,  , Uo,

, Uo,  , and gx.

, and gx.4.49. 6

a) Derive the following equation for the velocity potential for irrotational inviscid compressible flow in the absence of a body force:

where ∇ ϕ = u  , as usual. Start from the Euler equation (4.41), use the continuity equation, assume that the flow is isentropic so that p depends only on ρ, and denote

, as usual. Start from the Euler equation (4.41), use the continuity equation, assume that the flow is isentropic so that p depends only on ρ, and denote ( ∂ p / ∂ ρ ) s = c 2  .

.

, as usual. Start from the Euler equation (4.41), use the continuity equation, assume that the flow is isentropic so that p depends only on ρ, and denote

, as usual. Start from the Euler equation (4.41), use the continuity equation, assume that the flow is isentropic so that p depends only on ρ, and denote  .

.b) What limit does c → ∞ imply?

c) What limit does | ∇ ϕ |  → 0 imply?

→ 0 imply?

→ 0 imply?

→ 0 imply?4.51. Observations of the velocity u′ of an incompressible viscous fluid are made in a frame of reference rotating steadily at rate Ω = (0, 0, Ωz). The pressure at the origin is po and g = –gez.

a) In Cartesian coordinates with u′ = (U, V, W) = a constant, find p(x,y,z).

b) In cylindrical coordinates with u′ = –ΩzReφ, determine p(R,φ,z). Guess the result if you can.

4.52. For many atmospheric flows, rotation of the earth is important. The momentum equation for inviscid flow in a frame of reference rotating at a constant rate Ω  is:

is:

is:

is:

For steady two-dimensional horizontal flow, u = ( u , v , 0 )  , with Φ = gz and ρ = ρ(z), show that the streamlines are parallel to constant pressure lines when the fluid particle acceleration is dominated by the Coriolis acceleration

, with Φ = gz and ρ = ρ(z), show that the streamlines are parallel to constant pressure lines when the fluid particle acceleration is dominated by the Coriolis acceleration | ( u · ∇ ) u | ≪ | 2 Ω × u |  , and when the local pressure gradient dominates the centripetal acceleration

, and when the local pressure gradient dominates the centripetal acceleration | Ω × ( Ω × x ) | ≪ | ∇ p | / ρ  . [This seemingly strange result governs just about all large-scale weather phenomena like hurricanes and other storms, and it allows weather forecasts to be made based on surface pressure measurements alone. Hints:

. [This seemingly strange result governs just about all large-scale weather phenomena like hurricanes and other storms, and it allows weather forecasts to be made based on surface pressure measurements alone. Hints:

, with Φ = gz and ρ = ρ(z), show that the streamlines are parallel to constant pressure lines when the fluid particle acceleration is dominated by the Coriolis acceleration

, with Φ = gz and ρ = ρ(z), show that the streamlines are parallel to constant pressure lines when the fluid particle acceleration is dominated by the Coriolis acceleration  , and when the local pressure gradient dominates the centripetal acceleration

, and when the local pressure gradient dominates the centripetal acceleration  . [This seemingly strange result governs just about all large-scale weather phenomena like hurricanes and other storms, and it allows weather forecasts to be made based on surface pressure measurements alone. Hints:

. [This seemingly strange result governs just about all large-scale weather phenomena like hurricanes and other storms, and it allows weather forecasts to be made based on surface pressure measurements alone. Hints:1. If Y(x) defines a streamline contour, then d Y / d x = v / u  is the streamline slope.

is the streamline slope.

is the streamline slope.

is the streamline slope.2. Write out all three components of the momentum equation and build the ratio v/u.

3. Using hint 1, the pressure increment along a streamline is: d p = ( ∂ p / ∂ x ) d x + ( ∂ p / ∂ y ) d Y  .]

.]

.]

.]4.56. For many gases and liquids (and solids too!), the following equations are valid:

(Fourier's law of heat conduction, k = thermal conductivity, T = temperature), e = eo + cvT (e = internal energy per unit mass, cv = specific heat at constant volume), and h = ho + cpT (h = enthalpy per unit mass, cp = specific heat at constant pressure), where eo and ho are constants, and cv and cp are also constants. Start with the energy equation

(Fourier's law of heat conduction, k = thermal conductivity, T = temperature), e = eo + cvT (e = internal energy per unit mass, cv = specific heat at constant volume), and h = ho + cpT (h = enthalpy per unit mass, cp = specific heat at constant pressure), where eo and ho are constants, and cv and cp are also constants. Start with the energy equation

for each of the following items.

a) Derive an equation for T involving uj, k, ρ, and cv for incompressible flow when τij = 0.

b) Derive an equation for T involving uj, k, ρ, and cp for flow with p = const. and τij = 0.

c) Provide a physical explanation why the answers to a) and b) are different.

4.58. Show that the first version of (4.68) is true without abandoning index notation or using vector identities.

4.59. Consider an incompressible planar Couette flow, which is the flow between two parallel plates separated by a distance b. The upper plate is moving parallel to itself at speed U, and the lower plate is stationary. Let the x-axis lie on the lower plate. The pressure and velocity fields are independent of x, and fluid has uniform density and viscosity.

a) Show that the pressure distribution is hydrostatic and that the solution of the Navier-Stokes equation is u(y) = Uy/b.

b) Write the expressions for the stress and strain rate tensors, and show that the viscous kinetic-energy dissipation per unit volume is μU2/b2.

c) Evaluate the kinetic energy equation (4.56) within a rectangular control volume for which the two horizontal surfaces coincide with the walls and the two vertical surfaces are perpendicular to the flow and show that the viscous dissipation and the work done in moving the upper surface are equal.

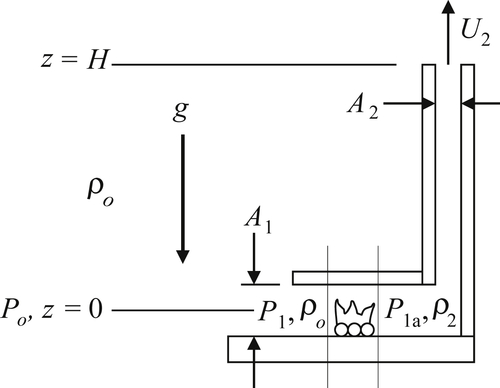

4.60. Determine the outlet speed, U2, of a chimney in terms of ρo, ρ2, g, H, A1, and A2. For simplicity, assume the fire merely decreases the density of the air from ρo to ρ2 (ρo > ρ2) and does not add any mass to the airflow. (This mass flow assumption isn’t true, but it serves to keep the algebra under control in this problem.) The relevant parameters are shown in the figure. Use the steady Bernoulli equation into the inlet and from the outlet of the fire, but perform a control volume analysis across the fire. Ignore the vertical extent of A1 compared to H and the effects of viscosity.

4.61. A hemispherical vessel of radius R has a small rounded orifice of area A at the bottom. Show that the time required to lower the level from h1 to h2 is given by

4.62. Water flows through a pipe in a gravitational field as shown in the accompanying figure. Neglect the effects of viscosity and surface tension. Solve the appropriate conservation equations for the variation of the cross-sectional area of the fluid column A(z) after the water has left the pipe at z = 0. The velocity of the fluid at z = 0 is uniform at υ0 and the cross-sectional area is A0.

4.63. Redo the solution for the orifice-in-a-tank problem allowing for the fact that in Figure 4.16, h = h(t), but ignoring fluid acceleration. Estimate how long it takes for the tank take to empty.

4.64. Consider the planar flow of Example 3.5, u = (Ax, –Ay), but allow A = A(t) to depend on time. Here the fluid density is ρ, the pressure at the origin or coordinates is po, and there are no body forces.

a) If the fluid is inviscid, determine the pressure on the x-axis, p(x,0,t) as a function of time from the unsteady Bernoulli equation.

b) If the fluid has constant viscosities μ and μυ, determine the pressure throughout the flow field, p(x,y,t), from the x-direction and y-direction differential momentum equations.

c) Are the results for parts a) and b) consistent with each other? Explain your findings.

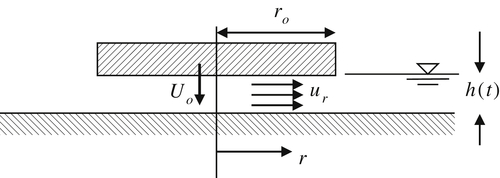

4.65. A circular plate is forced down at a steady velocity Uo against a flat surface. Frictionless incompressible fluid of density ρ fills the gap h(t). Assume that h ≪ ro = the plate radius, and that the radial velocity ur(r,t) is constant across the gap.

a) Obtain a formula for ur(r,t) in terms of r, Uo, and h.

b) Determine ∂ur(r,t)/∂t.

c) Calculate the pressure distribution under the plate assuming that p(r = ro) = 0.

4.66. A frictionless, incompressible fluid with density ρ resides in a horizontal nozzle of length L having a cross-sectional area that varies smoothly between Ai and Ao via: A ( x ) = A i + ( A o − A i ) f ( x / L )  , where f is a function that goes from 0 to 1 as x/L goes from 0 to 1. Here the x-axis lies on the nozzle’s centerline, and x = 0 and x = L are the horizontal locations of the nozzle’s inlet and outlet, respectively. At t = 0, the pressure at the inlet of the nozzle is raised to pi > po, where po is the (atmospheric) outlet pressure of the nozzle, and the fluid begins to flow horizontally through the nozzle.

, where f is a function that goes from 0 to 1 as x/L goes from 0 to 1. Here the x-axis lies on the nozzle’s centerline, and x = 0 and x = L are the horizontal locations of the nozzle’s inlet and outlet, respectively. At t = 0, the pressure at the inlet of the nozzle is raised to pi > po, where po is the (atmospheric) outlet pressure of the nozzle, and the fluid begins to flow horizontally through the nozzle.

, where f is a function that goes from 0 to 1 as x/L goes from 0 to 1. Here the x-axis lies on the nozzle’s centerline, and x = 0 and x = L are the horizontal locations of the nozzle’s inlet and outlet, respectively. At t = 0, the pressure at the inlet of the nozzle is raised to pi > po, where po is the (atmospheric) outlet pressure of the nozzle, and the fluid begins to flow horizontally through the nozzle.

, where f is a function that goes from 0 to 1 as x/L goes from 0 to 1. Here the x-axis lies on the nozzle’s centerline, and x = 0 and x = L are the horizontal locations of the nozzle’s inlet and outlet, respectively. At t = 0, the pressure at the inlet of the nozzle is raised to pi > po, where po is the (atmospheric) outlet pressure of the nozzle, and the fluid begins to flow horizontally through the nozzle.a) Derive the following equation for the time-dependent volume flow rate Q(t) through the nozzle from the unsteady Bernoulli equation and an appropriate conservation-of-mass relationship.

b) Solve the equation of part a) when f ( x / L ) = x / L  .

.

.

.c) If ρ = 103 kg/m3, L = 25 cm, Ai = 100 cm2, Ao = 30 cm2, and pi – po = 100 kPa for t ≥ 0, how long does it take for the flow rate to reach 99% of its steady-state value?

4.67. For steady constant-density inviscid flow with body force per unit mass g = − ∇ Φ  , it is possible to derive the following Bernoulli equation:

, it is possible to derive the following Bernoulli equation: p + 1 2 ρ | u | 2 + ρ Φ =  constant along a streamline.

constant along a streamline.

, it is possible to derive the following Bernoulli equation:

, it is possible to derive the following Bernoulli equation:  constant along a streamline.

constant along a streamline.a) What is the equivalent form of the Bernoulli equation for constant-density inviscid flow that appears steady when viewed in a frame of reference that rotates at a constant rate about the z-axis, i.e., when Ω = ( 0,0 , Ω z )  with Ωz constant?

with Ωz constant?

with Ωz constant?

with Ωz constant?b) If the extra term found in the Bernoulli equation is considered a pressure correction: Where on the surface of the earth (i.e., at what latitude) will this pressure correction be the largest? What is the absolute size of the maximum pressure correction when changes in R on a streamline are 1 m, 1 km, and 103 km.

4.68. Starting from (4.45) derive the following unsteady Bernoulli equation for inviscid incompressible irrotational fluid flow observed in a nonrotating frame of reference undergoing acceleration dU/dt with its z-axis vertical.

4.69. Using the small slope version of the surface curvature 1 / R 1 ≈ d 2 ζ / d x 2  , redo Example 4.15 to find h and ζ(x) in terms of x, σ, ρ, g, and θ. Show that the two answers are consistent when θ approaches π/2.

, redo Example 4.15 to find h and ζ(x) in terms of x, σ, ρ, g, and θ. Show that the two answers are consistent when θ approaches π/2.

, redo Example 4.15 to find h and ζ(x) in terms of x, σ, ρ, g, and θ. Show that the two answers are consistent when θ approaches π/2.

, redo Example 4.15 to find h and ζ(x) in terms of x, σ, ρ, g, and θ. Show that the two answers are consistent when θ approaches π/2.4.70. An spherical bubble with radius R(t), containing gas with negligible density, creates purely radial flow, u = (ur(r,t), 0, 0), in an unbounded bath of a quiescent incompressible liquid with density ρ and viscosity μ. Determine ur(t) in terms of R(t), its derivatives. Ignoring body forces, and assuming a pressure of p∞ far from the bubble, find (and solve) an equation for the pressure distribution, p(r,t), outside the bubble. Integrate this equation from r = R to r → ∞  , and apply an appropriate boundary condition at the bubble's surface to find the Rayleigh-Plesset equation for the pressure pB(t) inside the bubble:

, and apply an appropriate boundary condition at the bubble's surface to find the Rayleigh-Plesset equation for the pressure pB(t) inside the bubble:

, and apply an appropriate boundary condition at the bubble's surface to find the Rayleigh-Plesset equation for the pressure pB(t) inside the bubble:

, and apply an appropriate boundary condition at the bubble's surface to find the Rayleigh-Plesset equation for the pressure pB(t) inside the bubble:

where μ is the fluid's viscosity and σ is the surface tension.

4.71. Redo the dimensionless scaling leading to (4.101) by choosing a generic viscous stress, μU/l, and then a generic hydrostatic pressure, ρgl, to make p − p∞ dimensionless. Interpret the revised dimensionless coefficients that appear in the scaled momentum equation, and relate them to St, Re, and Fr.

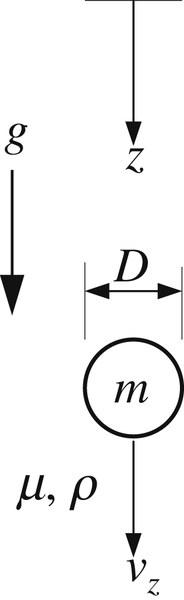

4.72. A solid sphere of mass m and diameter D is released from rest and falls through an incompressible viscous fluid with density ρ and viscosity μ under the action of gravity g. When the z coordinate increases downward, the vertical component of Newton’s second law for the sphere is: m ( d u z / d t ) = + m g − F B − F D  , where uz is positive downward, FB is the buoyancy force on the sphere, and FD is the fluid-dynamic drag force on the sphere. Here, with uz > 0, FD opposes the sphere’s downward motion. At first the sphere is moving slowly so its Reynolds number is low, but

, where uz is positive downward, FB is the buoyancy force on the sphere, and FD is the fluid-dynamic drag force on the sphere. Here, with uz > 0, FD opposes the sphere’s downward motion. At first the sphere is moving slowly so its Reynolds number is low, but R e D = ρ u z D / μ  increases with time as the sphere’s velocity increases. To account for this variation in ReD, the sphere’s coefficient of drag may be approximated as:

increases with time as the sphere’s velocity increases. To account for this variation in ReD, the sphere’s coefficient of drag may be approximated as: C D ≅ 1 2 + 24 / R e D  . For the following items, provide answers in terms of m, ρ, μ, g and D; do not use z, uz, FB, or FD.

. For the following items, provide answers in terms of m, ρ, μ, g and D; do not use z, uz, FB, or FD.

, where uz is positive downward, FB is the buoyancy force on the sphere, and FD is the fluid-dynamic drag force on the sphere. Here, with uz > 0, FD opposes the sphere’s downward motion. At first the sphere is moving slowly so its Reynolds number is low, but

, where uz is positive downward, FB is the buoyancy force on the sphere, and FD is the fluid-dynamic drag force on the sphere. Here, with uz > 0, FD opposes the sphere’s downward motion. At first the sphere is moving slowly so its Reynolds number is low, but  increases with time as the sphere’s velocity increases. To account for this variation in ReD, the sphere’s coefficient of drag may be approximated as:

increases with time as the sphere’s velocity increases. To account for this variation in ReD, the sphere’s coefficient of drag may be approximated as:  . For the following items, provide answers in terms of m, ρ, μ, g and D; do not use z, uz, FB, or FD.

. For the following items, provide answers in terms of m, ρ, μ, g and D; do not use z, uz, FB, or FD.a) Assume the sphere's vertical equation of motion will be solved by a computer after being put into dimensionless form. Therefore, use the information provided and the definition t∗ ≡ ρgtD/μ to show that this equation may be rewritten: ( d R e D / d t ∗ ) = A R e D 2 + B R e D + C  , and determine the coefficients A, B, and C.

, and determine the coefficients A, B, and C.

, and determine the coefficients A, B, and C.

, and determine the coefficients A, B, and C.b) Solve the part a) equation for ReD analytically in terms of A, B, and C for a sphere that is initially at rest.

c) Undo the dimensionless scaling to determine the terminal velocity of the sphere from the part c) answer as t → ∞  .

.

.

.4.73.

a) From (4.101), what is the dimensional differential momentum equation for steady incompressible viscous flow as R e → ∞  when g = 0.

when g = 0.

when g = 0.

when g = 0.b) Repeat part a) for R e → 0  . Does this equation include the pressure gradient?

. Does this equation include the pressure gradient?

. Does this equation include the pressure gradient?

. Does this equation include the pressure gradient?4.74.

a) Simplify (4.45) for motion of a constant-density inviscid fluid observed in a frame of reference that does not translate but does rotate at a constant rate Ω = Ωez.

b) Use length, velocity, acceleration, rotation, and density scales of L, U, g, Ω, and ρ to determine the dimensionless parameters for this flow when g = –gez and x = (x, y, z). (Hint: substract out the static pressure distribution.)

c) The Rossby number, Ro, in this situation is U/ΩL. What are the simplified equations of motion for a steady horizontal flow, u = (u, v, 0), observed in the rotating frame of reference when Ro ≪ 1.

4.75. From Figure 4.23, it can be seen that CD ∝ 1/Re at small Reynolds numbers and that CD is approximately constant at large Reynolds numbers. Redo the dimensional analysis leading to (4.99) to verify these observations when:

a) Re is low and fluid inertia is unimportant so ρ is no longer a parameter.

b) Re is high and the drag force is dominated by fore-aft pressure differences on the sphere and μ is no longer a parameter.

4.76. Suppose that the power to drive a propeller of an airplane depends on d (diameter of the propeller), U (free-stream velocity), ω (angular velocity of propeller), c (velocity of sound), ρ (density of fluid), and μ (viscosity). Find the dimensionless groups. In your opinion, which of these are the most important and should be duplicated in model testing?

4.77. A 1/25 scale model of a submarine is being tested in a wind tunnel in which p = 200 kPa and T = 300 K. If the speed of the full-size submarine is 30 km/hr, what should be the free-stream velocity in the wind tunnel? What is the drag ratio? Assume that the submarine would not operate near the free surface of the ocean.

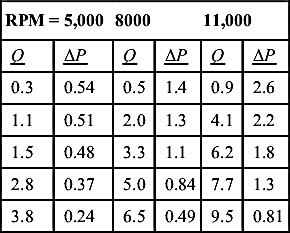

4.78. The volume flow rate Q from a centrifugal blower depends on its rotation rate Ω, its diameter d, the pressure rise it works against Δp, and the density ρ and viscosity μ of the working fluid.

a) Develop a dimensionless scaling law for Q in terms of the other parameters.

b) Simplify the result of part c) for high Reynolds number pumping where μ is no longer a parameter.

d) What maximum pressure rise would you predict for a geometrically similar blower having twice the diameter if it were spun at 6,500 RPM?

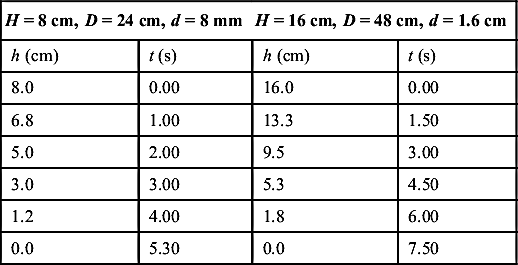

4.79. A set of small-scale tank-draining experiments are performed to predict the liquid depth, h, as a function of time t for the draining process of a large cylindrical tank that is geometrically similar to the small-experiment tanks. The relevant parameters are gravity g, initial tank depth H, tank diameter D, orifice diameter d, and the density and viscosity of the liquid, ρ and μ, respectively.

a) Determine a general relationship between h and the other parameters.

b) Using the following small-scale experiment results, determine whether or not the liquid’s viscosity is an important parameter.

c) Using the small-scale-experiment results above, predict how long it takes to completely drain the liquid from a large tank having H = 10 m, D = 30 m, and d = 1.0 m.