13.4. Geostrophic Flow

Consider quasi-steady, large-scale motions in the atmosphere or the ocean, away from boundaries. For these flows an excellent approximation for the horizontal equilibrium is a geostrophic balance where the Coriolis acceleration matches the horizontal pressure-gradient acceleration:

(13.11, 13.12)

(13.11, 13.12)

The second equality in each case follows from (13.7). These are the first two equations of the set (13.9) when the friction terms, and the unsteady and nonlinear acceleration terms are neglected. If U is the horizontal velocity scale, and L is the horizontal length scale, then ratio of the nonlinear term to the Coriolis term, called the Rossby number, is:

(13.13)

(13.13)

For a typical atmospheric value of U ∼ 10 m/s with f ∼ 10−4 s−1, and L ∼ 1000 km, Ro is 0.1, and it is even smaller for many flows in the ocean. Thus, neglect of the nonlinear terms is justified for many geophysical flows. Geostrophic equilibrium is lost near the equator (within a latitude belt of ±3°), where f becomes small, and it also breaks down if frictional effects or unsteadiness become important.

For steady flow, (13.11) and (13.12) can be used to understand some of the unique phenomena associated with the Coriolis acceleration. For example, when these equations apply, the velocity distribution can be determined from a measured distribution of the pressure field. In particular, these equations imply that velocities in a geostrophic flow are perpendicular to the horizontal pressure gradient. Forming u · ∇ p  using (13.11) and (13.12) produces:

using (13.11) and (13.12) produces:

using (13.11) and (13.12) produces:

using (13.11) and (13.12) produces:

Thus, the horizontal velocity is along, and not across, the lines of constant pressure. If f is regarded as constant, then the geostrophic balance, (13.11) and (13.12), shows that p/(fρ0) can be regarded as a stream function. Therefore, the isobars on a weather map are nearly the streamlines of the flow.

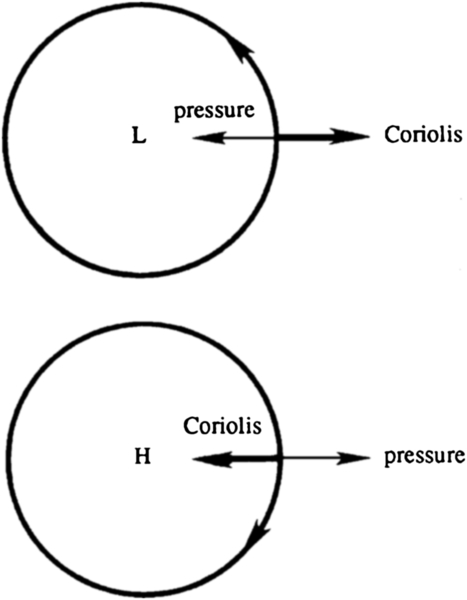

Figure 13.4 shows the geostrophic flow around low- and high-pressure centers in the northern hemisphere. Here the Coriolis acceleration acts to the right of the velocity vector. This requires the flow to be counterclockwise (viewed from above) around a low-pressure region and clockwise around a high-pressure region. The sense of circulation is opposite in the southern hemisphere, where the Coriolis acceleration acts to the left of the velocity vector. Frictional forces become important at lower levels in the atmosphere and result in a flow partially across the isobars. For example, frictional effects on an otherwise geostrophic flow cause the flow around a low-pressure center to spiral inward (see Section 13.5).

Thermal Wind

In the presence of a horizontal gradient of density, the geostrophic velocity develops a vertical shear. This is can be shown from the geostrophic and hydrostatic balances by differentiating both parts of (13.11) with respect to z and then using (1.14), ∂p/∂z = – ρg, to eliminate p from both equations. The result is:

(13.14, 13.15)

(13.14, 13.15)

Meteorologists call these the thermal wind equations because they give the vertical variation of wind from measurements of horizontal temperature (and pressure) gradients. The thermal wind is a baroclinic phenomenon, because the surfaces of constant p and ρ do not coincide.

Taylor-Proudman Theorem

A striking phenomenon occurs in the geostrophic flow of a homogeneous fluid. It can only be observed in a laboratory because stratification effects cannot be avoided in natural flows. Consider then a laboratory experiment in which a tank of fluid is steadily rotated at a high angular speed Ω and a solid body is moved slowly along the bottom of the tank. The purpose of making Ω large and the movement of the solid body slow is to make the Coriolis acceleration much larger than the advective acceleration terms, which must be made negligible for geostrophic equilibrium. Away from the frictional effects of boundaries, the balance is geostrophic in the horizontal and hydrostatic in the vertical. Setting f = 2Ω in (13.11) and (13.12) produces:

(13.16, 13.17)

(13.16, 13.17)

It is useful to define an Ekman number, E, as the ratio of viscous to Coriolis accelerations:

(13.18)

(13.18)

which can be combined with the continuity equation (4.10) to reach:

(13.19)

(13.19)

Also, differentiating (13.16) and (13.17) with respect to z, and using (1.14) with ρ = constant, leads to:

(13.20)

(13.20)

(13.21)

(13.21)

Thus, the fluid velocity cannot vary in the direction of Ω. In other words, steady slow motions in a rotating, homogeneous, inviscid fluid are two-dimensional. This is the Taylor-Proudman theorem, first derived by Proudman in 1916 and demonstrated experimentally by Taylor soon afterward.

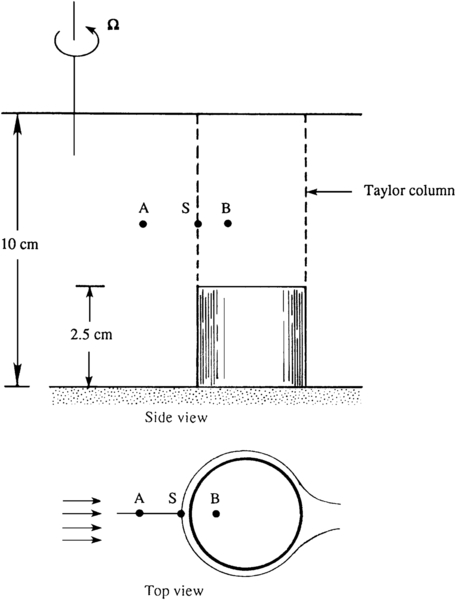

Figure 13.5 Taylor’s experiment in a strongly rotating flow of a homogeneous fluid. When the short cylinder is moved toward the axis of rotation, an extension of the cylinder forms in the fluid above it. Dye released above the cylinder at point A flows around the extension of cylinder as if it were a solid object. Dye released above the cylinder at point B follows the motion of the short cylinder.

In Taylor’s experiment, a tank was made to rotate as a solid body, and a small cylinder was slowly dragged along the bottom of the tank (Figure 13.5). Dye was introduced from point A above the cylinder and directly ahead of it. In a non-rotating fluid the water would pass over the top of the moving cylinder. In the rotating experiment, however, the dye divides at a point S, as if it had been blocked by a vertical extension of the cylinder, and flows around this imaginary cylinder, called the Taylor column. Dye released from a point B within the Taylor column remained there and moved with the cylinder. The conclusion was that the flow outside the upward extension of the cylinder is the same as if the cylinder extended across the entire water depth and that a column of water directly above the cylinder moves with it. The motion is two dimensional, although the solid body does not extend across the entire water depth. Taylor did a second experiment, in which he dragged a solid body parallel to the axis of rotation. In accordance with ∂w/∂z = 0, he observed that a column of fluid is pushed ahead. The lateral velocity components u and v were zero. In both of these experiments, there are shear layers at the edge of the Taylor column.

In summary, Taylor’s experiment established the following striking fact for steady inviscid motion of a homogeneous fluid in a strongly rotating system: bodies moving either parallel or perpendicular to the axis of rotation carry along with their motion a so-called Taylor column of fluid, oriented parallel to the axis of rotation. The phenomenon is analogous to the horizontal blocking caused by a solid body (say a mountain) in a strongly stratified system, shown in Figure 8.30.