13.5. Ekman Layers

In the preceding section, geostrophic balance was found to occur at low Rossby number when the flow is steady and frictionless. This section extends this analysis to fluid motion within the frictional layers that develop on horizontal surfaces. In viscous flows unaffected by Coriolis accelerations and pressure gradients, the only terms in the equation of motion that can balance viscous friction are either the unsteady acceleration ∂u/∂t, or the advective acceleration ( u · ∇ ) u  . The balance of ∂u/∂t and viscous friction gives rise to a viscous layer having characteristics that evolve with time, as in the case of a moving flat plate (see Sections 9.4 and 9.5). Alternatively, the balance of

. The balance of ∂u/∂t and viscous friction gives rise to a viscous layer having characteristics that evolve with time, as in the case of a moving flat plate (see Sections 9.4 and 9.5). Alternatively, the balance of ( u · ∇ ) u  and viscous friction for flow past a flat surface gives rise to a boundary layer having a thickness that may vary in the direction of flow (see Sections 10.3 and 10.4). In a steadily rotating coordinate system, a third possibility arises, a balance between the Coriolis acceleration and friction. Here, the viscous layer, known as an Ekman layer, can be invariant in time and space, and two examples of such layers are provided in this section.

and viscous friction for flow past a flat surface gives rise to a boundary layer having a thickness that may vary in the direction of flow (see Sections 10.3 and 10.4). In a steadily rotating coordinate system, a third possibility arises, a balance between the Coriolis acceleration and friction. Here, the viscous layer, known as an Ekman layer, can be invariant in time and space, and two examples of such layers are provided in this section.

. The balance of ∂u/∂t and viscous friction gives rise to a viscous layer having characteristics that evolve with time, as in the case of a moving flat plate (see Sections 9.4 and 9.5). Alternatively, the balance of

. The balance of ∂u/∂t and viscous friction gives rise to a viscous layer having characteristics that evolve with time, as in the case of a moving flat plate (see Sections 9.4 and 9.5). Alternatively, the balance of  and viscous friction for flow past a flat surface gives rise to a boundary layer having a thickness that may vary in the direction of flow (see Sections 10.3 and 10.4). In a steadily rotating coordinate system, a third possibility arises, a balance between the Coriolis acceleration and friction. Here, the viscous layer, known as an Ekman layer, can be invariant in time and space, and two examples of such layers are provided in this section.

and viscous friction for flow past a flat surface gives rise to a boundary layer having a thickness that may vary in the direction of flow (see Sections 10.3 and 10.4). In a steadily rotating coordinate system, a third possibility arises, a balance between the Coriolis acceleration and friction. Here, the viscous layer, known as an Ekman layer, can be invariant in time and space, and two examples of such layers are provided in this section.Ekman Layer at a Free Surface

Consider first the frictional layer near the free surface of the ocean that is formed by a steady wind stress τ on the ocean surface in the x-direction. For simplicity, only the steady solution is examined for horizontally homogeneous flow without horizontal pressure gradients. Under these conditions, the first two equations of (13.9) reduce to:

(13.22, 13.23)

(13.22, 13.23)

Defining z = 0 on surface of the ocean, the boundary conditions are:

(13.24, 13.25, 13.26)

(13.24, 13.25, 13.26)

Equations (13.22) and (13.23) are linear and can be solved via a complex superposition. Multiply (13.23) by the imaginary root, i = − 1  , and add (13.22) to reach:

, and add (13.22) to reach:

, and add (13.22) to reach:

, and add (13.22) to reach: (13.27)

(13.27)

(13.28)

(13.28)

sets the thickness of the Ekman layer. To satisfy (13.26), the constant B must be zero. The surface boundary conditions (13.24) and (13.25) can be combined as ρνV(dV/dz) = τ at z = 0, from which (13.28) with B = 0 gives:

(13.29)

(13.29)

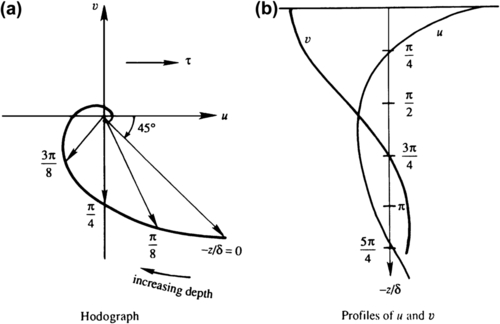

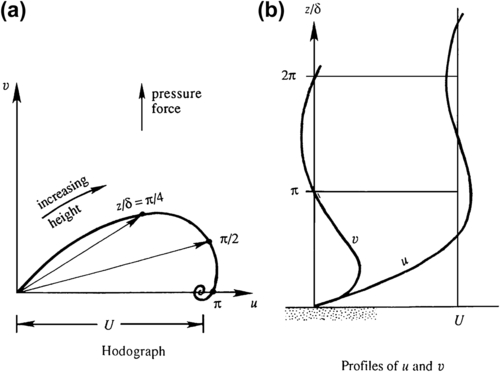

The Swedish oceanographer Ekman worked out this solution in 1905. The solution is shown in Figure 13.6 for the case of the northern hemisphere, in which f is positive. The velocities at various depths within the ocean are plotted in Figure 13.6a where each arrow represents the velocity vector at a certain depth. Such a plot of v versus u is sometimes called a hodograph. The vertical distributions of u and v are shown in Figure 13.6b. The hodograph shows that the surface velocity is deflected 45° to the right of the applied wind stress. (In the southern hemisphere the deflection is to the left of the surface stress.) The velocity vector rotates clockwise (looking down) with depth, and the magnitude exponentially decays with an e-folding length of δ, the Ekman layer thickness. The tips of the velocity vector at various depths form a spiral, called the Ekman spiral.

Figure 13.6 Ekman layer below a water surface on which a shear stress τ is applied in the x-direction. The left panel (a) shows the horizontal fluid velocity components (u, v) at various depths; values of −z/δ are indicated along the curve traced out by the tip of the velocity vector. The flow speed is highest near the surface. The right panel (b) shows vertical distributions of u and v. Here, the Coriolis acceleration produces significant depth dependence in the fluid velocity even though τ is constant and unidirectional.

The components of the volume transport in the Ekman layer are:

(13.30)

(13.30)

This shows that the net transport is to the right of the applied stress and is independent of νV. In fact, the second part of (13.30) follows directly from a vertical integration of (13.22) in the form −ρfv = dτ/dz so that the result does not depend on the eddy viscosity assumption. The fact that the transport is to the right of the applied stress makes sense because then the net (depth-integrated) effect of the Coriolis acceleration, which is directed to the right of the depth-integrated transport, balances the wind stress.

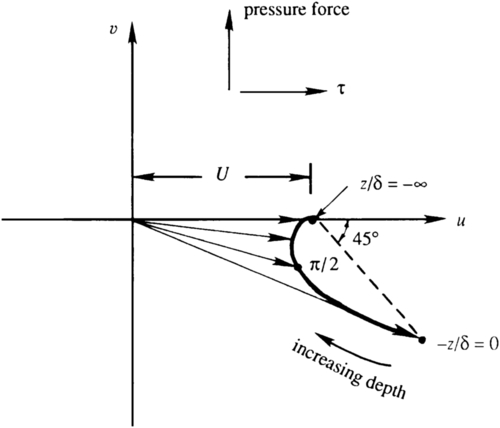

The horizontal uniformity assumed in the solution is not a serious limitation since Ekman layers near the ocean surface have a thickness (∼50 m) that is much smaller than the scale of horizontal variation (L > 100 km). The assumed absence of a horizontal pressure gradient can also be reconsidered. Because of the thinness of the layer, any imposed horizontal pressure gradient remains constant across the layer. The presence of a horizontal pressure gradient merely adds a depth-independent geostrophic velocity to the Ekman solution. Suppose the sea surface slopes down to the north, so that there is a pressure force acting northward throughout the Ekman layer and below (Figure 13.7). This means that at the bottom of the Ekman layer (z/δ → −∞) there is a geostrophic velocity U to the right of the pressure force. The surface Ekman spiral forced by the wind stress joins smoothly to this geostrophic velocity as z/δ → −∞.

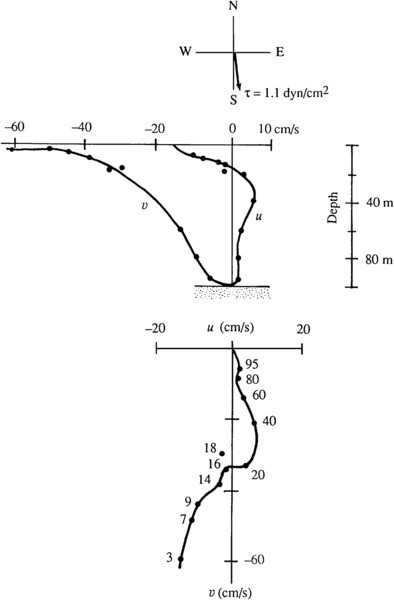

Pure Ekman spirals are not observed in the surface layer of the ocean, mainly because the assumptions of constant eddy viscosity and steadiness are particularly restrictive. When the flow is averaged over a few days, however, several instances have been found in which the current does look like a spiral. One such example is shown in Figure 13.8.

Figure 13.7 Ekman layer at a free surface in the presence of a pressure gradient. The geostrophic velocity forced by the pressure gradient is U. The flow profile in this case is the sum of U and the profile shown in Figure 13.6.

Figure 13.8 An observed velocity distribution near the coast of Oregon. Velocity is averaged over 7 days. Wind stress had a magnitude of 1.1 dyn/cm2 and was directed nearly southward, as indicated at the top of the figure. The upper panel shows vertical distributions of u and v, and the lower panel shows the hodograph in which depths are indicated in meters. The hodograph is similar to that of a surface Ekman layer (of depth 16 m) lying over the bottom Ekman layer (extending from a depth of 16 m to the ocean bottom). P. Kundu, in Bottom Turbulence, J. C. J. Nihoul, ed., Elsevier, 1977; reprinted with the permission of Jacques C. J. Nihoul.

Explanation in Terms of Vortex Tilting

In flows without rotation, the thickness of a viscous layer usually grows in time or in downstream distance. The Ekman solution, in contrast, results in a viscous layer that does not grow either in time or space. This can be explained by examining the vorticity equation (Pedlosky, 1987). The vorticity components in the x- and y-directions are:

(13.31)

(13.31)

The right sides of these equations represent diffusion of vorticity. Without Coriolis effects this diffusion would cause a thickening of the viscous layer. The presence of planetary rotation, however, means that vertical fluid lines coincide with the planetary vortex lines. The tilting of vertical fluid lines, represented by terms on the left sides of equations (13.31), then causes a rate of change of the horizontal component of vorticity that just cancels the diffusion term.

Ekman Layer on a Rigid Surface

As a second case of a viscous layer that is invariant in time and space, consider a steady viscous layer on a solid surface in a rotating flow that is independent of the horizontal coordinates x and y. This can be the atmospheric boundary layer over the ground that develops from winds aloft, or the boundary layer on the ocean bottom that develops below a uniform current in the water column. As for the first Ekman layer, assume the fluid velocity is in the x-direction with magnitude U at large distances from the surface. Viscous forces are negligible far from the surface, so that the Coriolis acceleration can be balanced only by a pressure gradient and (13.12) applies with u = U:

(13.32)

(13.32)

This simply states that the flow outside the viscous layer is in geostrophic balance, U being the geostrophic velocity. For positive U and f, dp/dy must be negative, so that the pressure falls with increasing y—that is, the pressure force is directed along the positive y direction, resulting in a geostrophic flow U to the right of the pressure force in the northern hemisphere. The horizontal pressure gradient remains constant within the thin boundary layer.

Near the solid surface friction forces are important, so that the balance within the boundary layer is:

(13.33, 13.34)

(13.33, 13.34)

(13.35, 13.36)

(13.35, 13.36)

where z = 0 on the solid surface and is positive upward. As for the free-surface Ekman layer, multiply (13.34) by i and add (13.33), to find the equivalent of (13.27):

(13.37)

(13.37)

(13.38, 13.39)

(13.38, 13.39)

The particular solution of the linear differential equation (13.37) is V = U, so the total solution is:

(13.40)

(13.40)

where δ is given by (13.28). To satisfy (13.38), A must be zero, so (13.39) then requires B = −U. Thus, the velocity components are:

(13.41)

(13.41)

In this case, the tip of the velocity vector again describes a spiral for various values of z (Figure 13.9a). As with the free-surface Ekman layer, the frictional effects are confined within a layer of thickness δ, which increases with νV and decreases with the rotation rate f. Interestingly, the layer thickness is independent of the magnitude of the free-stream velocity U; this behavior is quite different from that of a steady non-rotating boundary layer on a semi-infinite plate (see Section 10.3) in which the thickness is proportional to U–1/2. And, the velocity fields for both Ekman layers, (13.29) and (13.41), are in the form u = (u(z), v(z), 0) so that all the fluid acceleration terms, Du/Dt = ∂u/∂t + ( u · ∇ ) u  , in (13.9) are zero; thus, (13.29) and (13.41) are exact solutions of (13.9).

, in (13.9) are zero; thus, (13.29) and (13.41) are exact solutions of (13.9).

, in (13.9) are zero; thus, (13.29) and (13.41) are exact solutions of (13.9).

, in (13.9) are zero; thus, (13.29) and (13.41) are exact solutions of (13.9).Figure 13.9b shows the vertical distribution of the velocity components. Far from the wall the velocity is entirely in the x-direction, and the Coriolis acceleration balances the pressure gradient. As the wall is approached, frictional effects decrease u and the associated Coriolis acceleration, so that the pressure gradient (which is independent of z) produces a component v in the direction of the pressure force. Using (13.41), the net transport in the Ekman layer normal to the uniform stream outside the layer is:

Figure 13.9 Ekman layer above a rigid surface for a steady outer-flow velocity of U (parallel to the x-axis). The left panel shows velocity vectors at various heights; values of z/δ are indicated along the curve traced out by the tip of the velocity vectors. The right panel shows vertical distributions of u and v.

which is directed to the left of the free-stream velocity, in the direction of the pressure force.

If the atmosphere were in laminar motion, νV would be equal to its molecular value for air, and the Ekman layer thickness at a latitude of 45° (where f ≃ 10−4 s−1) would be ≈ δ ∼ 0.4 m. The observed thickness of the atmospheric boundary layer is of order 1 km, which implies an eddy viscosity of order νV ∼ 50 m2/s. In fact, Taylor (1915) tried to estimate the eddy viscosity by matching the predicted velocity distributions (13.41) with the observed wind at various heights.

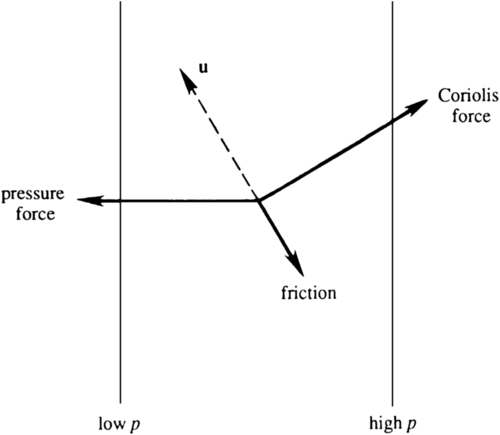

The Ekman layer solution on a solid surface demonstrates that the three-way balance among the Coriolis, the pressure gradient, and friction terms within the boundary layer results in a component of flow directed toward the lower pressure. This balance of forces within the boundary layer is illustrated in Figure 13.10. The net frictional force on an element is oriented approximately opposite to the velocity vector u. It is clear that a balance of forces is possible only if the velocity vector has a component from high to low pressure, as shown. Frictional forces therefore cause the flow around a low-pressure center to spiral inward. Mass conservation requires that the inward converging flow rise within a low-pressure system, resulting in cloud formation and rainfall. This is what happens in a cyclone, a low-pressure system. In contrast, within a high-pressure system the air sinks as it spirals outward due to frictional effects. The arrival of high-pressure systems therefore brings in clear skies and fair weather, because the sinking air suppresses cloud formation.

Figure 13.10 Balance of forces within an Ekman layer. For steady flow without friction, pressure gradient and Coriolis terms would balance. When friction is added, the pressure gradient and Coriolis terms must counteract it. Since friction acts opposite the direction of flow, the velocity u must have a component toward lower pressure when friction is present.

Frictional effects, in particular the Ekman transport by surface winds, play a fundamental role in the theory of wind-driven ocean circulation. Possibly the most important result of such theories was given by Henry Stommel in 1948. He showed that the northward increase of the Coriolis parameter f is responsible for making the currents along western ocean boundaries (e.g., the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic and the Kuroshio in the Pacific) much stronger than the currents on the eastern side. These are discussed in books on physical oceanography and are not presented here.