Where Is Home?

Japanese farmhouses are built with posts and beams, though one main post (the daikoku bashira) is the center of the structure. The post that runs through the living room up to our bedroom is made of Japanese cypress. When Tadaaki was a boy, he remembers his grandmother rubbing the post with sesame oil to enhance the grain of this treasured pillar that holds up the house. While the rest of the beams and posts are typically made from rougher cuts or recycled wood, the Japanese carpenter selects a particularly beautiful piece of wood with a distinct personality for the main bearing post of a house.

I often feel like that post is the backbone of our family, and the house is the frame that keeps us together. So when I go out from the house, in some way I am without my center. That does not mean I experience some wrenching sensation when I finally heave myself onto the bus bound for Narita airport, bags stowed and airplane sandwiches on ice. Strangely, I leave easily. It is the coming back that is hard. Funny, the words used to describe this process: I am a “registered alien” and have a “reentry permit” to come back into Japan. In many, many senses of the word, “reentry” does prove to be a jarring transition.

The house almost seems to have spurned me. Somehow life has gone on without me; there are changes that Tadaaki has effected in my absence—some not so subtle. The clutter has grown, and the same things that were on the counter when I left don’t appear to have shifted position. In one sense, life has stood still, but in another sense it has taken another direction and my space has closed up, leaving me almost an outsider.

One fall had been particularly busy with trips abroad. I spent a couple of weeks “interning” in the kitchen at Chez Panisse in September, ten days in Italy for Slow Food in October, and then two weeks in California to visit family and attend a Japanese food event at the CIA in Napa. When I got back from Italy, I found a dog in my kitchen. Tadaaki had decided to give himself a dog for his birthday. Never mind that I had strongly vetoed the idea when Matthew began lobbying for a dog a few years previously.

When the boys were small, the need to get out of Japan mounted like a pressure cooker. The longest time between trips was an unbearable eighteen months. In those days, the stress of running a small business, demands of farm life, bringing up bicultural children, and living as a foreigner in Japan were sometimes too much to endure. These days, I’m older, hopefully wiser, but certainly more prosaic. I don’t “need” to get out of Japan anymore, but I am pulled by the feeling of being connected to a larger world food community, and those bonds draw me to Berkeley, California, or Portland, Oregon, and sometimes to the countryside of France or Italy. In those places I am quasi-normal and don’t stand out (much).

Several years ago Christopher told me he was done going to Italy or France because we only “moved house,” so to speak. We had the same daily life in Italy or France that we had in Japan: hang around the house, read, watch videos, and eat good food. The big difference he overlooked was that although this was his daily life in Japan, mine was not one of leisure, so for me this routine was heaven. I’m not a fan of sightseeing; I go abroad for the chance to eat a favorite cook’s food and a chance to use a foreign language (other than Japanese). And I go for the guilt-free ability to hang around and be lazy (though these days, I often write all day and I don’t feel at all guilty about being “lazy”).

Now that my originally-homeschooled sons are all in school, I miss that they don’t come with me, though I carry the memories I had with them. That fall trip to Italy was the first without any of the boys, but I retraced our steps, staying in our favorite room in the castle and eating at our favorite restaurant, La Libera. In my transits between Pollenzo and Alba, I often found myself taking a wrong turn. But with those wrong turns came an accompanying feeling of warmth from that familiar feeling of getting lost in the same spot, that feeling of “I’ve been here before” accompanied by a strange impression of being home.

I thought about that sensation over the course of the following weeks and realized that despite my visceral connection to the old Japanese farmhouse in which I live, I also had a few other spots in the world that conjured up in me a different sense of home. And all of those places are where I spent time with my boys, away from Japan and away from them being predominantly Japanese. I will always be the odd one here in Japan, and maybe I will always be the odd one in other countries, but somehow in California, Italy, or France, I introduced another world to my boys, and we shared that world in a different way than we can ever share Japan. Because in Japan, their father is the conduit to how they enter society, but in foreign countries I am. And I liked that feeling of being in charge and that feeling of being completely comfortable outside in the outside world. My outside world.

But once again I am home—installed in the house. Writing at my laptop, I’ve taken back possession. Sick of the dog dishes sloshing water on the floor, I moved them out of the way, but when no one is looking I give that incorrigible black Lab of Tadaaki’s a surreptitious pat. Her name is Hana, but for now I call her Dog.

PANTRY

Perhaps the most intimidating aspect of cooking food from another culture is the daunting number of unfamiliar ingredients needed to make many dishes. Not so with Japanese farm food—with only miso or soy sauce in your kitchen, you can make stir-fries from farmers’ market vegetables. Many Japanese ingredients have incomprehensible labels full of kanji characters. Off-putting, to say the least. But I have found the best-quality versions of most of the items essential for a Japanese pantry are available through macrobiotic Internet mail-order sites, such as Gold Mine Natural Food Company (see Resources). Any other ingredients can be found at a Japanese (or Asian) grocery store.

I visited several Japanese grocery stores in the San Francisco Bay Area and Portland, Oregon, for the purpose of researching this book. My advice to you when standing in front of a shelf of nori, or konbu, or whatever: Pick the one that has the coolest packaging or looks most esthetically (beautifully) Japanese. I would steer clear of messy, gaudy labels or food that lists more than a small number of ingredients. Also I would avoid anything labeled with アミノ(amino); that indicates the presence of MSG. I have organized the Pantry section by order of importance, more as a reference than as a must-have list for your kitchen. The basic Japanese ingredients you will need for the recipes in this book are miso, soy sauce, katsuobushi, konbu, rice vinegar, sake, hon mirin, and of course, japonica rice. Your food will only be as good as the ingredients you choose, so choose wisely. Organic, small-producer miso and soy sauce may cost double the industrially produced ones. But consider the quantity of these condiments that you put into any given dish—merely tablespoons—which translates into but a few pennies. Beyond that, you will need top-quality sea salt; a very good, bright, clear oil, such as rapeseed; good-tasting flour (preferably unbleached and organic); and organic sugar. After that, get thee to the famers’ market, butcher, or fish market and buy what’s in season and looks good. Simple.

SALT FLAVORS

SOY SAUCE: You will find a myriad of soy sauces out there on the supermarket shelf, but why complicate things? We use only one kind of soy sauce in our house, made locally by Yamaki Jozo, but readily available in the U.S. packaged under the Ohsawa brand. If the Ohsawa soy sauce is too pricey, my college-student son buys Kikkoman organic and reports it is “not bad.” Producing soy sauce naturally is a process that should not be hurried. Large companies have a large output, so most must boost production through various means, such as starting from acid-hydrolyzed soy protein instead of soybeans and wheat. I prefer naturally fermented soy sauce (for obvious reasons).

MISO: Selecting miso can be bewildering. I would stick with one semimild, pleasant-flavored miso before you start experimenting with others. After all, unless you are preparing Japanese food on a daily basis, it may take you a while to make it through one container of miso. Here again, we buy miso from our local producer, Yamaki, who ferments the soybeans and grain with a natural mold (koji) for more than a year. And again the Yamaki miso is available in the U.S. under the Ohsawa label. I use brown rice miso, but barley miso is an excellent (though a bit darker-flavored) alternative. I have also noticed local miso in the Portland, Oregon, area, but have not tried it. Steer clear of miso with unusual flavors, such as dandelion-leek (at least for Japanese food).

SEA SALT: To be completely true to the integrity of your food, I would choose Japanese sea salt. I use finer sea salt (sold in 1-kg bags) for large pickling jobs or cooking and a shiny, slightly crystallized sea salt (sold in 200-g bags) for dipping tempura or salting simple vegetable stir-fries. This salt, an unforgettable Japanese fleur de sel produced by a fisherman in Wajima, is the best salt I have ever tasted. Product information in English for Wajima no Kaien is available through Good Food Japan (see Resources).

SHOTTSURU: Also known as ishiru and ishiri, shottsuru is a native Japanese fish sauce typically fermented from hata hata (sandfish) or squid. Splash on a raw cucumber salad, garnished with slivered ginger or use in place of salt in a stir-fry. Experiment. Shottsuru generally is given a longer fermentation than most Southeast Asian fish sauces and is not at all fishy. My hands-down favorite shottsuru is produced by Moroi Jozojo in Akita prefecture. They have a 10-year-old one that is like elixir. Pure heaven. (If you can say that about fish sauce!) Once I mentioned I wanted 6 bottles to bring to chef friends, and they sent them double-packed in bubble wrap along with nifty gift bags and assorted extras. Who would not love these people?

SEAWEED

KONBU: Kyoto chefs are particular about the konbu they use, for the good reason that they are producing a famous, highly stylized, precisely flavored cuisine called kaiseki ryori. For Japanese farm food (or any home cooking), buy good-looking, thick, folded sheets of this dried kelp—it will usually come in long packages and most likely will be the ma-konbu variety, which is gathered in southern Hokkaido. Break into manageable pieces and store in a well-sealed plastic bag.

WAKAME: If you can find fresh wakame, grab it and put it in miso soup or vegetable salads. Wakame is a seaweed that is invasive to the point of being a pest but is much favored in Japan. It is usually sold dried in the U.S., but sometimes can be found salted in the refrigerator section. Either way, you will need to soak the wakame at least a half hour in cold water to desalinate or to reconstitute before using.

NORI: Anyone who has ever eaten sushi is familiar with these sheets of red algae that have been air-dried in a process not unlike papermaking. There are many grades of nori; though perhaps the highest grade (read most expensive) will yield the best results. Sometimes called “laver” in English, nori is typically sold toasted, ready to use. Nowadays nori packages have small zips to keep the nori from getting floppy, but I recommend putting the bag in one more resealable plastic bag to double seal it. Nori can be recrisped by waving it (carefully) over a stove burner flame. Avoid the seasoned/flavored sheets or small packs of nori cut into eighths (designed for scooping up rice) unless you are fond of MSG.

KATSUOBUSHI

WHOLE: Dried, smoked skipjack tuna (usually called bonito) that is shaved on a razor-sharp planing blade set into a wooden shaving box (katsuobushi kezuriki). The curled flakes are used to make stock or to flavor vegetables.

ARAI-KEZURI: Thickly shaved (slightly leathery), rust-colored pieces good for making stock. Once opened, store in the fridge.

HANAKATSUO: Pinky-tan, fine flat shavings for topping vegetables or making stock. Once opened, store in the fridge.

CHILES

TOGARASHI: Chile japones, a small, hot chile used extensively in Japanese farm food. Found easily, but you can also substitute with chile de árbol. Usually used dried.

SHICHIMI TOGARASHI: 7-spice powder that contains red pepper, sansho, tangerine peel, white and black sesame seeds, hemp seeds, ginger, and aonori. Used for shaking on nabe (one-pot dishes) or hearty soups. Readily available at Asian markets. Buy one that is roughly ground and has visible colors (not pulverized into a homogeneous powder). Store in the fridge and replace every few months.

KOCHUJANG: Korean red pepper paste made from chiles, glutinous rice, fermented soybeans, and salt. Good with yakiniku.

RAYU: Chile-infused sesame oil used when eating gyoza and ramen. Also good on soy sauce–dressed salads. Easy to make.

YUZU KOSHO: A recently popular condiment made from pounded yuzu peel and green chiles; traditionally made in a few local areas of Japan, but now available everywhere. Good dabbed on salt-flavored ramen or country soup.

SOYBEANS

TOFU: There is no comparing freshly made tofu to the spongy long-shelf-life blocks of bean curd often found in U.S. supermarkets. If not locally available, with a little forethought and patience, it is not difficult to make your own.

USUAGE: Tofu blocks are sliced horizontally into thin (about ¼-inch/6-mm) slabs, weighted to press out liquid, and deep-fried to puff up. Usuage (“thin fried”) is also known as abura age (“oil fried”). Look for bright-colored pieces that do not appear saturated in inferior oil. Alternatively, degrease by pouring hot water over the usuage before using. If eating as a snack, recrisp briefly in a hot frying pan with a small amount of oil. Good as is for stir-fries or soups, or simmered in dashi and stuffed with sushi rice.

ATSUAGE: Deep-fried tofu blocks that have first been weighted to express water. Good in hearty soups or stir-fries.

GANMODOKI: Mashed and squeezed tofu is mixed with hand-grated yama imo (mountain yam) as a binder and seasoned with diced carrot, mushroom, and konbu. This tofu-vegetable mixture is formed into patties and deep-fried. Traditionally ganmodoki were used to add depth of flavor to nimono (dashi and soy sauce–flavored simmered root vegetables) or nabemono (one-pot dishes).

NATTO: Fermented soybeans inoculated with Bacillus natto, a “good” bacteria. In the U.S., most natto is sold frozen, in small foam packs with minute little packages of hot mustard and dashi-infused soy sauce included. However, local, organic natto is being produced in Sebastopol, California, and is available through Japan Traditional Foods via the Internet (see Resources). You will need to whip up the natto with chopsticks to create a creamy mass of beans full of sticky threads. Natto keeps for several weeks in the fridge.

OKARA: Soybean pulp—a by-product of making soy milk. Usually given away free by tofu shops and good stir-fried with vegetables.

YUBA: Soy milk skin skimmed off the surface of scalding soy milk during the tofu-making process and rolled into delicate cigar-shaped cylinders. Highly perishable, so must be eaten within a day or so of making.

OILS

RAPESEED: More commonly known as canola oil, rapeseed oil is extracted from rape blossoms (similar to rapini) and is the oil used by generations of Japanese farm families. My first taste of organic small-scale–produced rapeseed oil was eye opening. The oil had a clarity and brightness that I had heretofore not tasted in other so-called flavorless oils. I buy two varieties in 16.5-kg drums (big). One oil is made from organic Australian rapeseed, the other from Japanese. Both are excellent, but the Japanese oil is lighter, more elegant, and cleaner for deep-frying (but about 50 percent more expensive). I strongly urge you to discover your own “eye-opening” oil; be sure to pour out a little in a spoon and taste. The oil should be pleasant and fresh tasting, not flat, heavy, or flavorless.

COLD-PRESSED SESAME: Otherwise known as light sesame oil, a good alternative to the heavier dark sesame oil if you like a fresher taste. Organic cold-pressed sesame oil is easily found at health food stores.

DARK SESAME: I don’t use dark sesame oil much anymore because I often find the roasted sesame flavor too insistent. Nonetheless, we stock dark sesame oil in our pantry, since my husband and sons continue to love it. The oil is available in most Asian grocery stores and mainstream American supermarkets as well, though you may have better luck finding a high-quality organic sesame oil on the Internet.

LIQUORS

MIRIN: Seek out hon mirin (true mirin) since you will use only a little at a time—the flavor profile should have some depth and character. Mirin (a brewed condiment) is available in varying degrees of alcohol content (from 1 percent to 14 percent), with hon mirin having the highest level, thus giving a needed nuance to the food. Organic mirin is also available (and recommended). Avoid aji mirin, because the prefix aji typically refers to added “flavor” (MSG).

SAKE: As with wine, the better the sake, the better the end taste when cooking. But as with wine, the better the sake, the higher the price, so perhaps a middle ground needs to be considered. You can probably find a good-quality sake in the ten-dollar range for a 720-ml bottle. I have always found Harushika to be readily available in the States and an excellent mid-range choice.

SHOCHU: Low-grade shochu is often sold as “white liquor” in Japan and is used to make fruit-flavored cordials from summer fruits or tonics from medicinal mountain roots. Shochu is commonly distilled from sweet potatoes, barley, or rice, but can be made from other substances as well. Shochu is a popular liquor used in Japanese cocktails, while high-grade shochu is savored on the rocks by connoisseurs.

RICE

JAPANESE SHORT-GRAIN (JAPONICA) RICE: Often misnamed “sticky rice,” Japanese rice is part of the same family of rice as Arborio, one of the rice varieties used to make Italian risotto. While the Japanese cooking method does produce a fairly homogeneous rice that tends to clump together, if cooked well, the grains should break away from each other in your mouth. The rice should not be mushy. To remove any bran, Japanese rice needs to be scrubbed and rinsed until the wash water runs clear.

BROWN RICE: Brown rice is merely hulled, unpolished rice. Because the bran is intact, brown rice is healthier than white rice. Bran provides needed roughage to the body. Brown rice is cooked with a 1.5 : 1 water-to-rice ratio, rather than the usual 1 : 1 for white rice. Massa Organics in California sells top-quality organic brown rice grown on a family farm along the Sacramento River (see Resources).

GLUTINOUS RICE: For some reason glutinous rice (otherwise known as “sticky rice”) is often sold under the misnomer “sweet rice” and can contain cornstarch, iron, niacin, thiamine, and folic acid. Which begs the question . . . why? Be careful to check the label before buying. Glutinous rice contains no gluten; however, the grains exude a glutinous texture that results in a pleasantly tacky rice good for sweets or a savory steamed with azuki beans. Cooked glutinous rice keeps well for a couple of days at room temperature.

SEEDS, NUTS, BEANS, AND FLOUR

GOMA (SESAME): Avoid the roasted sesame seeds (iri-goma) sold in Japanese grocery stores. The sesame flavor will not be as pleasant as fresh-ground. Arrowhead Mills has unroasted, unhulled organic sesame seeds in 12-ounce (340-g) packages. You can also find them in the bulk section of some natural food stores.

ONIGURUMI (BLACK WALNUTS): Japanese native black walnuts are almost impossible to crack without a hammer (or wrecking ball), thus the name: “devil walnuts.” These walnuts grow in the hills near us and are sold in early winter at the local farm stands, but most urban-dwelling Japanese have never seen or tasted these rich, intensely flavored nuts. They are particularly favored for grinding up and adding to soba dipping sauce. Local conventional walnuts substitute nicely.

AZUKI (RED BEANS): Small, shiny red beans used for making anko (Sweet Red Bean Paste) and sekihan (Red Bean Rice). Organic azuki beans are available in 16-ounce (453-g) bags from Arrowhead Mills (sold as adzuki beans). You can also find them in the bulk section of some natural food stores or at Japanese grocery stores.

KUROMAME (NLACK BEANS): Round black soybeans that are simmered, left whole, and seasoned with sugar and soy sauce when soft. Available at Japanese grocery stores.

KINAKO (ROASTED SOYBEAN POWDER): Commonly used in Japanese sweet making for dusting. I prefer the black soybean powder (kuromame kinako) because it has more flavor (and is readily available in the U.S. at Japanese grocery stores).

JOSHINKO (RICE FLOUR): Made from plain (as opposed to glutinous) rice and used by farmers to make dango—no steaming is necessary, thus rendering the whole process much easier than when using mochiko.

MOCHIKO (MOCHI FLOUR): Fine-ground glutinous rice that substitutes as a shortcut for making mochi (steamed and pounded glutinous rice)—typically for kusa mochi (“herb” mochi pounded with mugwort). The mochiko is mixed with water to form a dough that is steamed before pounding and shaping.

UNBLEACHED ALL-PURPOSE OR CAKE FLOUR: Periodically, I refer to “good-tasting flour,” which may perplex some people. Most of us grew up only knowing industrialized flour and never realized flours from different locales had their own taste. I used to buy 20-kg sacks of flour from a miller and thought I was doing well to avoid supermarket shelf generic flour. Around that time, my husband began growing wheat. At first there were problems with the low gluten content in the wheat, then in overheating in the drying process, thus giving baked goods a slightly gummy consistency. But the flour tasted good. This was a kind of a life-changing revelation. It took Tadaaki about three more years to get the wheat right and the drying process worked out, but he did. Good-tasting flour will blow your socks off. Really. King Arthur Flour and Guisto’s are two excellent sources for flour that are available online (see Resources).

PANKO (DRIED BREAD CRUMBS): Made from dough cooked by electric currant rather than heat. I prefer to make my own from traditionally baked bread. Grate French or Italian-style white bread with the grating disc of a food processor, or in a blender. Preheat the oven to 300˚F (150˚C). Spread the grated bread out on a cookie sheet, no deeper than ½ inch (12 mm). Place in the middle of the oven and stir a couple of times while baking to evenly distribute the drier cooked edges with the middle soft area. Bake for 12 minutes or until dry to the touch but not browned (it may take an additional 2 to 4 minutes). When cool, store in a plastic container or sealed plastic bag in the refrigerator (or dry pantry with good air circulation). Keeps for several weeks or more.

SWEETENERS

ORGANIC GRANULATED SUGAR: I specify organic granulated sugar because the taste difference is remarkable and because I see no reason to use a tasteless agent that only adds sweetness and no other complexities. I strongly recommend finding good-quality organic granulated sugar (taste to evaluate), but ultimately the choice is yours.

KUROZATO (OKINAWAN BROWN SUGAR): This dense, fine-grained (flavorful) native sugar is available at Japanese grocery stores. Do not substitute American “brown” sugar because it is not at all the same.

KUROMITSU (BROWN SUGAR SYRUP): There is no need to purchase this separately, since kuromitsu is easily made by simmering kurozato with water. The flavor of dark molasses or blackstrap molasses is similar.

HOSHIGAKI (DRIED PERSIMMON): Dried in the early winter from tannic oval-shaped persimmons. Used to naturally sweeten dressings such as shira-ae. Substitute unsulfured dried apricots.

THICKENERS

KATAKURIKO (POTATO STARCH): The most common thickener or binder used in Japanese cooking. Also good for coating marinated chicken pieces before deep-frying.

KUZU (KUDZU): A starch made from the root of kuzu vines, used as a sauce thickener and in sweets. Real kuzu powder (hon kuzu) is difficult to find and expensive (even in Japan).

KANTEN (AGAR-AGAR): A natural jelling agent produced from red algae. Favored for making gelatin-based sweets or savory custards such as gomadofu. Historically, kanten was sold in various forms, from stick to strings, but today the powdered variety is most common. Available at Japanese grocery stores. Agar jelly is more delicate than gelatin and starts to set at room temperature.

MISCELLANEOUS

DRIED SHIITAKE: Often added to simmered foods (nimono) for a deep, earthy component.

ITO KONNYAKU OR SHIRATAKI (DEVIL’S TONGUE NOODLES): No-calorie slippery noodles made from konnyaku that hold up well in soupy dishes such as Gyudon, Sukiyaki, or Nikujaga.

KANPYO (DRIED GOURD STRIPS): Used in country sushi rolls and as a tie for simmered foods.

KURAGE (JELLYFISH): Salted jellyfish used in country sushi rolls after soaking and flavoring.

SURUME (AIR-DRIED SQUID): Used in matsumae zuke or as a healthy snack. Look for whole, flat squid and avoid shredded surume as it contains MSG.

NIGARI (MAGNESIUM CHLORIDE): Extracted from seawater, sold in liquid or crystal form. Essential in tofu-making and available from Gold Mine Natural Food Company (see Resources).

NUKA (RICE BRAN): The highly perishable outer layer of the white rice kernel after the rice has been hulled. Commonly available at Japanese grocery stores or health food stores. Used to make many kinds of Japanese pickles, including nukazuke.

KOJI (ASPERGILLUS MOLD): Used to make miso and sake or as a pickling agent for fish and vegetables. Available in Japanese grocery stores or online through Natural Import Company (see Resources).

SAKE KASU (SAKE LEES): Used to pickle fish or vegetables, available in Japanese grocery stores or from sake breweries.

AMAZAKE (SWEET “SAKE”): A nonalcoholic cultured rice product sold as amazake concentrate. Used in sakamanju, but can also be heated with water 1 : 1 for a warm pick-me-up on a blustery afternoon. Available online through Natural Import Company (see Resources).

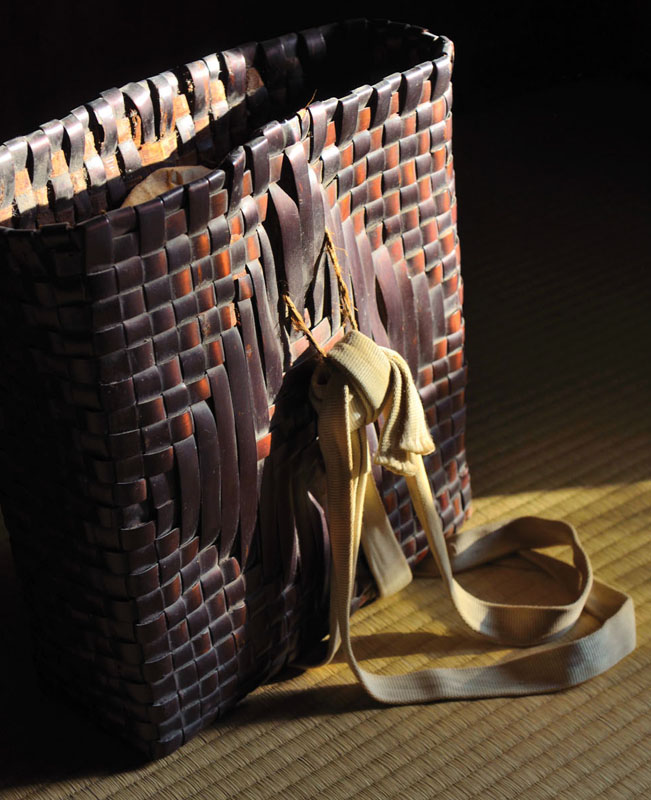

OUR LOCAL FLEA MARKET

TOOLS AND KNIVES

The Japanese farm kitchen is a low-tech affair. Traditionally, the farmwife made due with a grinding bowl, ginger grater, thick dowel used as a rolling pin, and sharp knife. Those days have come and gone; nonetheless, our Japanese kitchen remains fairly simple. Also, a Western substitute can be found for most common Japanese kitchen tools. The list I have compiled is meant to give you a sense of what implements were typically used in the Japanese farm kitchen (and may no longer be used in the urban one). I have organized the tools section by usage sequence (e.g., grinding, noodle making, charcoal barbecuing, sushi making, etc.). However, besides a grinding bowl, the only other absolutely necessary tool would be a sharp all-purpose knife (preferably Japanese) and a good sharpener. We use a banno bocho for vegetables and meat, and a sashimi bocho for slicing fish, but the banno bocho cuts fish nicely (provided it is razor sharp). Ultimately, sharpening your knife on a whetstone is the only way to create an edge, though a diamond-surfaced sharpening tool is useful for daily maintenance (or at least weekly, if you are busy). Any other all-purpose knife (bunka bocho), such as a funayuki bocho or santoku bocho perform the same multiple duties as our banno bocho. Hida Tool, an authentic Japanese neighborhood hardware store in Berkeley, California, sells various tools online (see Resources). One excellent knife is worth more than three mediocre ones. But keep the blade sharp!

TOOLS

SURIBACHI: A ceramic bowl with grooves combed into the surface used for grinding seeds or nuts. This is the one tool essential for making Japanese farmhouse food with ease. You can substitute a mortar, but the results will not be quite the same, and the process will be more arduous. Do not be tempted to save money and buy a small suribachi because seeds will jump out and you will regret your choice. Get the biggest one you can find (if possible, with at least the capacity of a medium-sized mixing bowl). You can find these at Japanese grocery stores, Korin (see Resources), or Amazon.

SURIKOGI: The grinding pestle that is used with the suribachi. While difficult to find these days, the best surikogi are made from the thick trunk of a sansho (prickly ash) bush. The knobby surface makes getting a purchase on the pestle easier than slick wood. Also the sansho adds some hint of flavor to what you are grinding (sansho is a relative of Sichuan pepper). Don’t bother with thin, feeble surikogi; go for the thickest one.

TAKE BURASHI: A small, rectangular bamboo “brush,” sometimes sold with suribachi sets. Useful for removing ground seeds that stubbornly remain in the grooves of your suribachi. Also works for getting the last grated ginger off of the oroshigane grating plate.

OROSHIGANE: The best tool for fine-grating ginger and daikon. Plastic grating plates are most common, though perhaps the least useful since they are brittle and do not stand up to big grating jobs. We use a circular ceramic grating plate (oroshiki) with a trough surrounding the raised and textured grating area (think flat volcano with a moat); the finely grated daikon slides down and is held in the trough as you grate. For ginger, a rectangular metal plate with sharp, raised teeth is best, though a wide-bladed Microplane with fine teeth pinch-hits admirably.

WASABI OROSHI: Wasabi is typically grated on a flat wood-handled board covered in sharkskin. The sharkskin tends to warp over time and eventually will separate from the board. A metal-toothed grinder also works well (sometimes better).

OTOSHI BUTA: A wooden or stainless steel drop-lid used when simmering vegetables in soy sauce–sweetened dashi. Parchment paper makes a fine substitute.

URAGOSHI: A straight-sided wooden sieve with metal mesh used to sift flour or separate chaff (or debris). Comes in many grades of mesh from coarse to fine. A Western sieve works almost the same, though the handled variety does not provide as stable a sifting action as one with graspable sides.

MENBO: A wooden dowel about 3 feet (90 cm) long and about 1¼ inches (3 cm) in diameter for rolling out Japanese noodles. An approximate tool can be purchased at any hardware store. French rolling pins are similar, though they have a wider diameter (and are expensive).

SEIMENKI: A standing Japanese noodle rolling machine made from cast iron and brass, with a rectangular wooden base. Since noodles were eaten nightly, every farm family in our area had a noodle roller to make quick work of the meal. We use ours often for rolling out both Western and Japanese noodles. These noodle rollers are costly even in Japan but extremely useful if you can find one. An Italian pasta roller will also work.

SUINO: A long-handled woven bamboo noodle scooper. New ones are pretty—old ones, patinaed by the wood-burning fire, are gorgeous.

ZARU: A round flat bamboo basket used to serve noodles that allows any excess water to drain off naturally. Available at Japanese cookware stores.

MUSHIKI: A tiered bamboo steaming basket easily available in Chinese or Japanese cookware stores or online at Korin (see Resources). Square wooden or metal steamers are known as seiro.

HIOKOSHI: A small, wood-handled, cast-iron charcoal starter. Available online at Korin (see Resources).

SHICHIRIN: An inexpensive round tabletop barbecue used for grilling yakiniku, yakitori, or fish in the garden. Shichirin (and konro) are often made from diatomaceous earth (keisodo), a naturally insulating material. Available online through Korin (see Resources).

KONRO: A rectangular “hibachi”-style tabletop barbecue. Note that konro are used for cooking. Available through Korin, but expensive. (The traditional hibachi are not cookers but wooden or porcelain containers filled halfway with ash to hold smoldering charcoal embers and provide heat for the house. Of course such traditional hibachi are anachronisms, but are much-sought-after antiques.) The term konro is also used for a butane-fueled tabletop burner, useful (or perhaps essential) when making sukiyaki or nabemono (one-pot dishes). Easily available through cookware supply stores or Amazon.

SUIHANKI: Japanese-style rice cooker—commonly available in any cooking store.

DONABE: A lidded ceramic casserole-style vessel used for cooking nabe or rice over a flame. Meant to simulate the traditional method of cooking food in an iron pot on top of a low charcoal-fueled kitchen cooker (kamado). The earthenware conducts the heat evenly but also (like rice cooked in an iron pot set over a kamado) enables the rice to form a favored delicacy called okoge, the crispy brown crust that results from cooking rice over a fire. The rice produced in a donabe is certainly more delicious than that steamed in the rice cooker, but the donabe has one disadvantage: The rice does not stay warm. Black-glazed Iga donabe from Nagatani-en (the same donabe I use) are available in the U.S. from Toiro Kitchen (see Resources), though for a hefty price. If you buy one donabe, buy the one that can cook rice because, depending on the style, many donabe meant to cook nabe will never work for cooking rice (but the rice cooker donabe serves admirably when throwing together a nabe dinner).

SHAMOJI: A thick, flat cedar paddle for serving rice, now commonly made of textured plastic. The cedar paddles are much more aesthetically pleasing, but there is no denying the ease of serving with the plastic, since the textured surface allows the rice to fall off nicely rather than stick stubbornly to the wooden paddle. You decide. I prefer the wooden ones, but my husband and sons use the plastic.

HANDAI: A round, low-sided, wide wooden tub used for cooling and aerating sushi rice as you add in the sweetened vinegar. The back of a large wooden cutting board can be substituted very successfully.

MAKISU: The bamboo mat used for rolling country sushi or any other rolled sushi meant to be cut into thick rounds.

OHASHI: Chopsticks (usually made of wood, but also of bamboo, iron, or bone) are extremely useful when deep-frying and the perfect implement to fluff up your rice when done steaming. Cooking and serving chopsticks are longer than those used for eating. In most Japanese households, each person has his or her own personal pair of chopsticks, and they are used at every meal.

WARIBASHI: Disposable chopsticks commonly used all over Japan when serving guests or eating outside of the house, though some eco-minded people carry their own chopsticks. Over the years I have collected a large number of extra chopsticks and no longer stock waribashi. Nonetheless, sometimes using them is unavoidable; in this case, please do not scrape waribashi against each other after breaking. This is considered bad manners because it signals to the host that he or she has provided cheap chopsticks that easily splinter. Making a person feel badly or ashamed goes deeply against the Japanese grain and should be avoided.

TAWASHI: An extremely stiff brush made of hemp palm that is the perfect vegetable brush. The bristles are rough enough to create the necessary friction to rub off the dirt and hard part of vegetable skins without having to peel them (and remove flavor). You can use a green “scrubby,” but it won’t do quite the same job. I use the “Turtle” tawashi made in Japan (see Resources).

TOFU TSUKURIKI (WOOD TOFU PRESS): Made from Japanese cypress. Along with other tofu-making supplies, it is available online (see Resources).

TOISHI (WHETSTONE): There is no substitute for this to sharpen kitchen knives (and any blade tools), though diamond-surfaced hand sharpeners are good stopgap tools to use for maintaining the edges of your knife blades. There is no need to feel intimidated by the stone or the hand sharpener. Like all things, learning how to sharpen knives well takes time, patience, and personal balance. But it is worth it in the long run! Without a sharp knife, it is impossible to cook.

KNIVES

BANNO BOCHO: This is the knife we use every day on just about everything (and we have a few of them). The blade is brittle, so it is not good for cutting hard surfaces such as crusty bread or kabocha. The banno bocho is made by our local knife maker and is meant to be a multipurpose knife that can be used on vegetables, fish, or meat. Similar styles of all-purpose knives (bunka bocho) are santoku bocho and funayuki bocho. If you buy one knife, choose a bunka bocho. To keep things simple, just look for a knife that has a curved blade to the end point and is described by the seller as all-purpose. There are many sources for Japanese knives, but I tend to trust a small, family-run business. I recommend talking to the guys at Hida Tool & Hardware in Berkeley, California—what you will gain in knowledge and expertise is worth the cost of a phone call (see Resources). Alternatively, skip the phone call (and the lesson) and just order directly from their online site.

DEBA BOCHO: A wide-bladed knife of varying sizes, heavy enough to cut through fish bones (sometimes called a sakana bocho—“fish knife”). A medium-sized deba bocho would be the second most useful knife to add to your kitchen. The deba bocho does a good job of cutting meat and, depending on the heft (and size) of the blade, can cut through poultry bones as well (using the corner nearest the handle).

SASHIMI BOCHO: A long, thin knife that comes in handy when slicing sashimi. We have several styles of sashimi bocho, but Tadaaki favors the squared-off rectangular type (takobiki) over the pointed tip style (yanagiba). Either works well. This is a specialty knife, only to be purchased when you are ready to step up your knife skills and start slicing your own sashimi.

HASAMI: Butterfly-shaped iron scissors whose design dates back to the Roman Empire. Japanese scissors are one of my most favorite Japanese tools because of their intrinsic beauty and superb workmanship. I get pleasure from holding them in my hand and love using them in the field to cut our gorgeous vegetables.

SHAGUJI

CUTTING AND COOKING TECHNIQUES

Probably the biggest hurdle for Western cooks preparing Japanese food is the difference in fish and meat cuts. After that, the vegetable cutting style is slightly elusive, since skilled Japanese home cooks typically keep much sharper knives in their kitchen than most homes in the West do. In general, Japanese cuts are much finer (and thinner) than most Western vegetable cutting styles. To this end, you will need a sharp knife. Also there are a few miscellaneous, easily learned techniques such as vegetable squeezing or tofu grinding clearly illustrated by photos. If you study the photos included in this section, you will have a visual reference to help you better understand the techniques or cutting style you want to achieve for any given dish. There really is no mystery. Japanese techniques may be different from Western techniques, but they are no more difficult.

COOKING TECHNIQUES

Roasting sesame

Squeezing pressed tofu

Grinding tofu

Scooping greens from pot

Refreshing greens

Scrubbing daikon with brush

Grating wasabi

Parboiled konnyaku pieces

Massaging salt into cucumbers

COOKING TECHNIQUES (CONTINUED)

Adding oil to egg for mayonnaise

Deep-frying (tempura)

Deep-frying (kara age)

Swirling egg onto katsudon

Searing bonito over straw

Cooking yakitori on a shichirin

COOKING VEGETABLES

Finely chopped green onion (mijingiri)

Julienned vegetables (sengiri): carrot and negi

Finely sliced vegetables (usugiri): cucumber

Eggplant cut for frying: shigiyaki

Shiso chiffonade

Boiled vegetables to be dressed

CLEANING AND SLICING FISH

Slicing sashimi

Tataki-style chopping

Removing squid skin

Lining fish with konbu

Filleting jack mackerel

Filleting sardines

MEAT CUTS

Sukiyaki

Gyudon

Katsudon

This chapter was designed as a sort of exhaustive overall look at Japanese ingredients, implements, and typical kitchen skills. You need not have even a fraction of these ingredients or implements in your pantry or kitchen. And you need not master a good portion of the kitchen skills because the majority of young Japanese today have not. Focus on getting a few quality tools and kitchen staples; and start small, making one dish at a time from the freshest ingredients you can find. Look to what you do have, not what you don’t.