Figure 8.1 Police action, Fifth Avenue, May 1, 2012. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

May 1–September 17, 2012

“. . . Police set to deal with Occupy crowd that vows to shut down city today . . .”

The message flits across the ribbon of light lining the entrance to the News Corp. Building on West 48th Street. May Day has dawned on another impressive show of force by the NYPD. By 4 a.m., hundreds of officers have donned riot gear and descended on Union Square. By rush hour, hundreds more have taken up positions amid the glass fortresses of the world’s financial giants. Still others monitor the CCTV cameras newly activated under the terms of the Midtown Manhattan Security Initiative.1

Around 8 a.m., affinity groups and action clusters converge from all directions on Bryant Park, the private-public space that sits one block to the east of Times Square amid a lackluster landscape of bank branches and chain stores. It is here that the occupiers reunite in the rain for an unpermitted “pop-up occupation,” claiming the park as a meeting place, a training ground, and a staging area for local protests and picket lines.

Equipped with a street map pinpointing targets of convenience—black diamonds for “Labor Disputes,” black circles for “Financial/Corporate HQs”—I follow the trail of picket lines and police barricades along the rain-slick streets, from the Bank of America Tower to the Sotheby’s auction house and back.

By the time I return to Bryant Park, the space has begun to take on the look and the feel of the occupations of old. All along the west side, I find the counterinstitutions of OWS resurrected and reinvented—if only for the day—as I peruse the People’s Library, feast at the People’s Kitchen, and temporarily lose my hearing at the drum circle.

At lunchtime, I join in a second wave of “99 Pickets,” this one known as the “Immigrant Worker Justice Tour.” Behind a multilingual banner asserting the power of “the people, el pueblo y ash-shab,” 500 or so 99 Percenters pour out of the park and into the streets of Midtown East. A short-lived march is followed by a series of lively pickets stretching from Fifth Avenue to Lexington Avenue. They target Praesidian Capital for its role in “union-busting” at Hot & Crusty Bakery; Capital Grille for its record of wage theft and discrimination; Chipotle Grill for its refusal to sign a Fair Food Agreement with farmworkers; and Wells Fargo for its portfolio of investments in private prisons.2

Despite repeated provocations by riot police with their batons drawn (see Figure 8.1), the Immigrant Worker Justice Tour will hold its participants to a high standard of conduct. When the march faces a kettle on 40th Street and Lexington, one immigrant occupier mic-checks the following message: “If you’re here in solidarity, you understand that some of us can’t risk arrest. We all hate the police state, but that doesn’t mean we can’t protect our communities. . . . Let’s work together on this!” Later, the pickets will disperse and return to the safety of the park, without a single arrest to report.

Figure 8.1 Police action, Fifth Avenue, May 1, 2012. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

Elsewhere, other embattled constituencies gather in smaller numbers, each in its own way. Facing the closure of a public high school, a multiracial youth bloc walks out of its morning classes and converges in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park. In Manhattan’s Madison Square Park, students from eleven area schools convene for a “Free University” (or “Free U”) featuring teach-ins, skill-shares, open debates, and outdoor classes.3

“We wanted to figure out a way for students and teachers to strike,” says CUNY organizer Manissa McCleave Maharawal. “And not just strike, but also think about education differently, think about the university differently, and create something new. . . . [Free U] gave me and other student organizers a chance to work outside our campuses . . . to think about what we do on an everyday level [and] how we can politicize it.”

To the south, a small but boisterous black bloc, its makeup overwhelmingly white, musters for a “wildcat” march through Lower Manhattan. “On May 1st, we aren’t working and we aren’t protesting,” reads their call to arms. “We are striking.” The “strikers” run riot through the streets of Chinatown, SoHo, and the West Village, toppling trash cans and police barricades as they go, and provoking a forceful reaction from baton-swinging white shirts and plainclothes officers.

Meanwhile, back in Midtown, an “Occupy Guitarmy,” armed with guitars, banjos, fiddles, ukeleles, and saxophones, kicks off a more mellow, melodic march. “A reminder to New York City’s Finest,” says Tom Morello, of the band Rage against the Machine. “You can’t arrest a song.” With Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” on their lips, the street ensemble brings traffic to a standstill along Fifth Avenue.

By midday, however, it is apparent that the “general strike” has been anything but general.4 Most New Yorkers can be seen going about their daily routines, untouched by the talk of “no business as usual.” Straphangers ride the rails. Commuters clog the streets. Workers clock into work. Investment bankers lock in their profits. The occupiers are kept at a safe remove from the targets of their ire. Out of sight, out of sound. Out of the way.

As May Day wears on and the workday draws to a close, the rain clouds finally lift, and the allied forces of the “4 x 4” assemble in Union Square Park, arriving by the busload, the carload, and the trainload. The May Day mobilization, it seems, has reactivated the old networks, forged in the time of the occupations, summoning back to the streets not only those who occupied last fall, but also the thousands more who marched, rallied, raised funds, volunteered, and organized in their support.

The scene in Union Square presents a living portrait of the low-wage workforce in the wake of the Great Recession. Here are sales clerks registering their discontent with picket signs reading, “Who Can Live on $7.25?” Here are undocumented day laborers bearing paint buckets that spell out a single word: “JOBS.” Here are taxi drivers hanging “Driver Power” signs from the hoods of their yellow cabs. Here, too, are domestic workers with posters in many languages, organizing, they say, for a day when “all work will be valued equally.” Many will return again and again to a well-rehearsed refrain:

“We! Are! The 99 Percent!”

For the next three hours, a kind of working-class carnival unfolds in and around Union Square, as the crowds spill out of the park and into the adjoining streets. Young revelers dance around a many-colored Maypole, “symbolically weav[ing] together the many struggles we face” in a reinvention of the ancient spring ritual. “All Our Grievances Are Connected,” reads the emblem that sits atop the pole. Visual artists turn the square into a riot of color with sidewalk chalking, sand painting, and screen printing; performing artists stage mock fashion “runways” and open-air “poetry assemblies”; rappers, rockers, DJs, and jazz percussionists serenade the multitude from a makeshift stage.

Lit by the last rays of the sun, the May Day marchers step off from Union Square South, finding their way out of the “cattle pens” and into the street. They fill the breadth of Broadway, eventually stretching the span of twenty blocks. Once more, the streets echo with their rhythmic call-and-response:

“Who’s got the power?” (“We got the power!”)

“What kind of power?” (“People power!”)

While police deploy all along the length of the march route, for the most part they appear to give the workers a wide berth, leaving their riot gear behind—for now—and trading force projection for a friendly face.

Yet as the “Occupy United” brings up the rear of the march with a rowdy street party, a samba band, and a flurry of black, red, and rainbow flags, officers close in from both sides of Broadway, following the occupiers’ every move. When we finally reach the Financial District, the police presence grows exponentially, with mounted officers guarding the gates of Wall Street and white shirts swarming the streets around Zuccotti Park. As the closing rally ensues with a succession of fiery speeches, hundreds of the more youthful marchers defy police orders and sit down in the middle of the street.

At this point, detectives demand that the organizers pull the plug. One of the MCs retorts from the stage, “‘Hipster Cop’ says that our sound permit has expired! What do we say?” Jorge and Nisha of OWS ascend the stage and take the mic, asserting the unity of “we, the people,” of the “organized and unorganized, employed and unemployed, public and private, documented and undocumented.” They then conclude on a note of international solidarity: “We are Tahrir Square. We are Syntagma Square. We are Puerta del Sol. We are Wisconsin. . . . We are New York. . . . We are the 99 Percent. Our time has come. Let freedom spring! Si se puede [Yes we can]!”

Moments later, trouble erupts on Broadway and Beaver. This time, the trouble is attributable, not to a struggle for the streets, but to the struggle to be heard. As Jorge attempts to announce an unpermitted “people’s assembly” (code for OWS’s latest ploy to “reoccupy public space), he is cut off midsentence by an operative from Local 100, who lets it be known that, “No announcements like that will be made from this stage.”

The May Day festivities were supposed to have concluded with a show of unity between OWS, organized labor, and immigrant New York. Instead, the day’s events end in a display of acrimony between the occupiers and their sometime allies, as they finally fracture over the question that has long bedeviled the movement: To occupy, or not to occupy? To occupy is the only answer that makes sense to many in OWS’s inner circle. But for their coalition partners, the point is not to occupy; the point, for them, is to win.5

Outraged but undeterred, the occupiers will turn from the P.A. system to the People’s Mic, and from Broadway to the Vietnam Veterans Plaza. Here, a diminished crowd will assemble in a semicircle on the steps of the plaza, rallying around the reflecting pool and a banner reading, ironically enough, “OCCUPY UNITED.” Shortly before 10 p.m., as the diehards dream of a “new occupation of Wall Street,” a sizable regiment of riot police encircles the plaza, while a lieutenant gives the order to disperse. Outnumbered and outflanked, most of us will choose to go quietly, slinking out of the park before melting into the Manhattan night.

In the end, the much-hyped “general strike” won the occupiers little more than a handful of headlines. In cities beyond New York, most May Day marches numbered in the hundreds to the low thousands. With the notable exceptions of ferry workers in the San Francisco Bay and airport workers at Los Angeles International—whose targets were longtime enemies of the local unions—there was nary a single strike to report.

The NYPD, for its part, would go on to declare victory over the movement. “There were less protesters,” boasted police spokesman Paul Brown to the press. “And they were met by police everywhere they went.”6

Internationally, the occupiers had come a long way in the year since the first “movement of the squares.” On May 12, Spain’s indignados filled Puerta del Sol and fifty-eight other plazas to capacity to mark the one-year anniversary of 15-M (see Chapter 1). Again and again they returned to the scene of the acampadas, defying government curfews and police charges, and bringing their assemblies and their counterinstitutions with them. By contrast, in Greece—where the occupations had failed to slow the march of austerity—many of the aganaktismenoi channeled their indignation into the voting booth. There, the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) would win 27 percent of the vote in the 2012 elections.7

Across the ocean, new waves of discontent were washing across the North American continent. In Quebec, students struck and occupied in protest of an unprecedented 60 percent tuition hike. The “infinite strike” soon snowballed into a broad-based revolt against the policies of the governing Liberal Party. Hundreds of thousands flooded the streets of Montreal, sporting “red squares” and banging on pots and pans. In Mexico, a loose network of young activists known as “#YoSoy132” launched a “physical and digital citizens’ movement” against what they called Mexico’s “Telecracy” (its corporate media) and its deficit of democracy, protesting the imminent return to power of the authoritarian Party of the Institutional Revolution. “The people are the boss,” they insisted, “not a handful of corrupt politicians and businessmen.”8

Here in New York City, the occupiers greeted the unfolding of this second “global spring” with great enthusiasm, emulating its tactics and echoing its themes. To mark the 15-M anniversary, fifty occupiers returned to the Financial District with their sleeping bags for a “sleepful protest” in full view of the Stock Exchange. Three days later, they descended on Times Square with signs of “Solidarity” in Spanish, French, and Arabic. To show support for their comrades in Quebec, they held “casserole” marches through Midtown Manhattan and “night schools” in Washington Square Park. Yet such actions were but distant echoes of events abroad. Oftentimes, they could hardly be heard amid the din of downtown traffic, or the steady drumbeat of corporate election coverage.

In a bid to recapture the media spotlight, occupiers in the American South and Midwest would go on to stage a series of high-profile spectacles, each one timed to coincide with what was already a national news event. Southern organizers set their sights on Bank of America’s shareholder meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina; Midwestern activists targeted the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) summit in Chicago.

To some observers, such showdowns were bound to end in disappointment, promising daring, but ultimately doomed exercises in street activism in the age of counterterrorism. At best, they would serve as focal points and flashpoints for Occupy’s flagging forces, much as the “Battle in Seattle” had done for the global justice movement in 1999, and as the struggle for Liberty Square had done for the “99 Percent” the previous fall. At worst, they threatened a throwback to the “summit-hopping” days of old, in which jet-setting street activists would “hop” from one contest to the next, without building the infrastructure that was needed to sustain organizing on the ground. In the decade since that movement’s demise, summit protests had time and again proven a losing strategy for activists—but a lucrative source of funding for public and private security.9

In Chicago, in preparation for the NATO summit, municipal managers instituted batteries of new rules and regulations. Mayor Rahm Emanuel pushed through an ordinance, known to its critics as the “Sit Down and Shut Up” law, requiring organizers to register all protest signs with the authorities beforehand and to purchase $1 million in liability insurance for any and all demonstrations. The mayor was also granted blanket spending authority and license to coordinate with some thirty external agencies, including DHS and the FBI.10

When I arrived in the Windy City on May 19, I was greeted by news of preemptive arrests. That morning, a car full of live streamers had been stopped and searched at gunpoint. At the same time, I heard reports of a proliferation of direct action, with Chicagoans making use of the spotlight on the NATO protests much as New Yorkers had used the spotlight on OWS: here, a National Nurses United rally for a “Robin Hood Tax” on financial transactions; there, an Occupy El Barrio march against mass deportations; elsewhere, a sit-in and encampment organized by the Mental Health Movement against the closure of a clinic by the city.11

“What Occupy helped to do was amplify some of those struggles, in a way,” notes Toussaint Losier, the anti-eviction activist we met in Chapter 7, who lent his support to the clinic occupation. “People in the Mental Health Movement planned to seize the building . . . and a lot of the folks from Occupy really made it possible to hold the line . . . connecting stuff that was happening downtown to [organizing in] the neighborhoods.”

That Sunday, thousands from those neighborhoods would join forces with thousands more from out of town to rally with the Coalition Against the NATO/G8, in opposition to what they called the “war and poverty agenda.” The messages they carried with them married the rhetoric of the anti-war movement with the politics of the 99 Percent movement: “Make Jobs Not War.” “Healthcare Not Warfare.” “Smart Kids Not Smart Bombs.” “They Play. We Pay.” “Occupy NATO.” “Occupy Til the Apocalypse.”

After a three-mile march to McCormick Place, blocks from the site of the summit, Occupy Oakland’s Scott Olsen and other military veterans attempted to “return” their medals to the NATO generals, in a gesture aimed at “bring[ing] US war dollars home to fund our communities.” Yet as the soldiers descended from the stage, it seemed as if the war dollars had been brought home precisely for days such as this. DHS alone had spent $55 million on security for the summit. Now, the agency was seeing a return on its investment. Within a few blocks’ radius stood hundreds of CPD officers in black body armor, many hailing from the city’s SWAT and gang units. Behind the CPD were arrayed the State Police’s Special Operations Command Units in their military-style fatigues.12

As the protest’s permit expired, the black bloc closed ranks, “masked up” and “linked up,” forming an autonomous, anonymous mass intent on storming the summit. On cue, the riot squads closed in to form a kettle around the crowd that remained in the intersection of Michigan Avenue and Cermak—whereupon the black bloc charged, kamikaze-like, into the waiting police lines. More than two hours of street fighting would ensue amid the ritual exchange of baton strikes and improvised projectiles.

“The police just started swinging,” remembers Natalie Solidarity, of Occupy Chicago’s Press and Direct Action committees. “I was hit, dozens of people were hit, there were people covered in blood. . . . A few blocks later, I looked up, and police officers were just beating people on the ground. . . . I looked behind me, and there was a guy bleeding profusely from his head. Turns out he was a photographer from OWS. I remember creating bandages out of business cards.”

“The whole world is watching!” the crowd chanted forcefully, as they had in 1968 and 2011. But what the world was watching was no longer the imagery of the “99 Percent” pitted against the “1 Percent,” but rather, in the words of one occupier, the imagery of the “boys in blue” battling the “boys in black.” Over seventy participants would sustain injuries, some of them quite serious. All in all, more than 117 would be arrested or detained, including three on domestic terrorism charges.13

“There was this sense of desperation, no one knew what to do,” recalls Kelly Hayes, a street medic, photographer, and organizer with Occupy Chicago and Occupy Rogers Park. “But we just kept marching. And then we got to an intersection, and we looked left, and there were the gates of McCormick Place. And we marched up to the gates, and sort of stood there with this realization that we had gotten further than anyone thought we could get. People started chanting, ‘Over the fence!’ ‘Over the fence!’”

“And I said, ‘No, that’s when they kill us.’”

Black bloc or no black bloc, the occupiers would continue to attract the rapt attention of state managers at every level of government throughout the spring and summer of 2012. Many cities would follow Chicago’s example, raising the cost of urban protest and tightening controls on the form and content of public assembly. In Charlotte, for instance, ahead of the Democratic National Convention (DNC), the City Council came up with an exhaustive list of items it deemed illegal to carry during “extraordinary events.” Bicycle helmets made the list, as did permanent markers.

Local authorities also called on higher powers for support during these “National Special Security Events.” Equipped with a “Mass Arrest Technology System,” Charlotte’s police department teamed up with forty-five public and private-sector partners, including DHS and the National Guard, to secure “critical infrastructure” (see Chapter 5). The City of Tampa, Florida, for its part, in preparation for the Republican National Convention (RNC), sought out the cooperation of over forty law enforcement agencies, along with the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command.14

Even at the occupiers’ own convention, the Occupy National Gathering (or “NatGat”)—hosted by Occupy Philadelphia and envisioned as a venue for the “creation of a vision for a democratic future”—guests would be subjected to intensive surveillance and aggressive policing by federal, state, and local law enforcement alike.

“Occupiers were coming in from all over the world—and so were the police,” says Larry Swetman, a young, working-class white man, originally from Atlanta, who helped to manage the gathering. “The National Park Service worked with local and nonlocal agencies, including Homeland Security . . . to put us down before we ever got started. . . . Our rights were not upheld, and lives have been ruined as a result.”

By June 2012, in the city of its birth, Occupy Wall Street had become a shadow of its former self. The general assembly and the spokescouncil had both been out of commission for well over three months. Regular attendance at working group meetings was down to the dozens, while turnout at protests was a fraction of what it had been in the fall. Many core occupiers privately acknowledged that after eight months in the streets, their energy was flagging, their capacity dwindling, and Occupy in danger of dying out.

“I think the core people really had a rough time during that period,” remembers Marisa Holmes, who helped to facilitate the OWS Community Dialogues. “I mean, people had come to a protest and stayed for an occupation. People who weren’t from New York had come to New York, and had been here for eight months. And then, all the repression and personal wear-and-tear. . . . After May Day, [it] just kind of fell apart.”

Within a month’s time, resources had nearly run out, with the general fund falling to $30,000 and the bail fund to $50,000. Some wealthy philanthropists tried to sell the organizers on a bailout from the Movement Resource Group (MRG), a fundraising outfit co-sponsored by the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation. The group would be instrumental in the planning and execution of large-scale projects like the Occupy National Gathering. “They gave us enough to where we were able to take care of our needs,” one organizer would tell me. Yet many refused to brook the MRG’s “top-down” organization, or to accept its “1 Percent” leadership. In the absence of wealthy funders—or, for that matter, a critical mass of grassroots donors—Occupy’s financial support would founder.15

By this time, corporate media coverage had dropped precipitously since the fall of 2011. OWS now hardly registered on the radar of the daily newspapers or the nightly news, which, in the words of one movement scribe, had grown “bored with Occupy—and inequality.” Citations in newspapers had fallen from a peak of 12,000 for the month of October to a trough of 1,000 for the month of May. Social media traffic had slowed significantly, in tandem with the mainstream coverage.16

“The media cycle was only going to last for so long,” says Mark Bray, a young white anarchist from New Jersey, who worked with OWS’s P.R. and Direct Action working groups through the spring. “And with the mainstream media and social media, the cycles were shorter. . . . The media was the sort of adrenaline that kept [OWS] going for a while. . . then very quickly sucked the life out of it.”

“In some ways, Occupy kind of lived and died by corporate media,” concurs Arun Gupta, co-founder of The Occupied Wall Street Journal. “But the corporate media is part of the dominant governing structure. And when push comes to shove, [the media] will tend to fall in line. You’re not going to counter it through tweeting and live streaming.”

It did not help that many among those who had been most active in OWS—and most outspoken in its defense—were now confronted with lengthy court cases, criminal records, and monetary fines. “I had not seen repression . . . to the extent that I felt it now,” says Sandra Nurse, of the Direct Action Working Group. “Seeing me and a lot of my friends put on the ‘domestic terrorism’ watchlist. Cops coming to my house. People getting their doors kicked in.” In New York City, many of Sandra’s comrades would face criminal charges ranging from “Disorderly Conduct” to “Assaulting a Police Officer.”17

Elsewhere, many occupiers I knew were doing what most everyone of our generation was doing: They were looking for work. Some had their own personal or familial safety nets. Others had been hired by local unions, not-for-profits, and new media outfits. But a significant proportion of the occupiers, who had once relied on the solidarity of strangers, were struggling to get by. These survived on part-time jobs, temporary gigs, and “dumpstered” delicacies plucked from trash cans in the dead of night.

“If activists don’t get compensated for their work,” observes Justine Tunney, of OccupyWallSt.org, “political engagement becomes a bourgeois luxury. You can’t be compensated with ‘mutual aid.’ There’s just not enough of it.”

For many occupiers, their politics was personal, their issues inseparable from their interests. And for a great number of them, no issue was more personal than that of student debt. Organizing for a debtors’ strike had begun with the Occupy Student Debt Campaign (OSDC): “As members of the most indebted generations in history,” its original call to arms had read, “we pledge to stop making student loan payments after one million of us have signed this pledge.” For a time, the OSDC had garnered a measure of publicity, inspiring a spate of “debt burnings” on April 25 (“1T Day,” the day student debt was set to surpass $1 trillion). Yet no million debtors’ strike appeared to be in the offing.18

In light of this fact, dozens of diehards now came together to form a broader-based network of debt resisters and anti-bank crusaders, which they called Strike Debt.19 Among its facilitators were some of those who had first gathered in Tompkins Square Park, one year earlier, to plan the Wall Street occupation. At first, much of its base came from circles of anarchists and horizontalists—many of them students, artists, or academics affiliated with OWS offshoots like Occupy Theory and Tidal Magazine.

For Amin Husain, the issue of debt was as personal as could be. Having accumulated more than $100,000 of it as an undergraduate, he tells me, “You’re crazy if you think I’m ever going to pay that. After I put my sisters through college, then took care of my parents, I was like, I’m going to get out. I’m not going to pay that.”

Zoltán Glück, a young white organizer from San Francisco and a graduate student at CUNY, suggests that this experience was typical in the movement: “I think a lot of people who have gotten involved, from the beginning, are people who have tracked through universities . . . who had life expectations, based on what they had been promised or what they had been given to expect. And they have found themselves, rather, in situations of job precarity, of indebtedness, of instability.”

On June 10, dozens of Strike Debtors convened in Washington Square Park for the first “debtors’ assembly.” Here, they spoke out publicly—many of them for the first time—through a cardboard “debtors’ mic.” In the words of one speaker, “Debt isolates, atomizes, and individuates. The first step is breaking the silence. Shedding the fear. Creating a space where we can appear together without shame.”

Drawing inspiration from the LGBT liberation movement, participants called on other debtors to “come out” of the debt closet. Soon, they were taking their message to the streets and setting social media networks abuzz with slogans like “Silence = Debt” and “You Are Not a Loan.”20 In theory, the new network would be open to the bearers of all manner of debt, including that owed on mortgages, medical procedures, even credit cards. As one Strike Debtor put it, “Debt is bigger than just students. It’s a connective issue that could bring together an exciting coalition together across many demographics.”

In the assemblies that followed, however, Strike Debt quickly polarized around questions that had long divided the 99 Percent movement: Was $25,000 in student debt to be equated with $250,000 in medical debt? Were middle-class college graduates in a position to speak on behalf of, say, working-class convalescents? Were white students in a position to tell black families to go into bankruptcy?

Given such asymmetries of experience, power, and resources, the network never reached very far beyond the ranks of highly educated, downwardly mobile Millennials and Generation Xers, who had the motivation and the capacity to speak out in public about their bad credit. Although they won the support of elder sympathizers (such as parents and professors), the Strike Debtors were unable to secure the critical mass they would have needed to form a “debtors’ union,” let alone to spark a national debt strike.

As summer turned to fall, Strike Debt would transition toward less threatening, more market-based approaches, such as the “Rolling Jubilee,” in which participants would buy up millions of dollars’ worth of debt for pennies on the dollar. In the face of such tactics, however, the balance of power remained skewed as ever in the bankers’ favor.21

When the occupiers first burst onto the national political scene, one year before, they had received an enthusiastic embrace from many within the Democratic Party. The meteoric rise of the 99 Percent movement had generated a surge of interest and excitement among its progressive base, who saw in it an opportunity to take on the corporate Right. As the general election season drew nigh, even the Democratic establishment had joined in the chorus, calling on supporters to “help us reach 100,000 strong standing with Occupy.”22

For a time, pundits and political analysts had taken to comparing OWS to the Tea Party. Some had even speculated that its electoral impact would be as decisive in the 2012 elections as the latter had been in 2010.23 Yet many occupiers wanted no part in a “Tea Party of the Left.” Nor did they expect to influence the outcome of the general election—at least not in the name of OWS. For the 99 Percenters remained deeply conflicted over their stance toward the White House, the Democrats, and the two-party system itself. At issue was not only their relationship to the race for the presidency, but the very meaning of democracy in 2012. Was true democracy even possible inside that party system? Or did real democracy look more like Liberty Square?

Occupiers like Madeline Nelson, of the Direct Action Working Group, held that both parties were beholden to the interests of the billionaires who bankrolled their campaigns: “Party systems do not work. The two-party system in the U.S. is made null and void by its complete subjugation to the corporations that pay billions to both sides to protect their profits and power.” Justin Wedes, of the Media Working Group, echoed these sentiments: “You reach a certain point where the people who have been elected to represent you don’t represent you anymore. And it is really just beneath our dignity to continue to beg for the politicians to listen to us and not to their campaign donors.”

By contrast, occupiers like Nelini Stamp, of the Working Families Party, warned that, “If we don’t pay attention to electoral politics, that’s when we’re going to be wrong. Not in the sense that we’re going to go out there and campaign for someone. But be aware of what’s happening and beware of what can happen.” Nelini argued for an inside-outside strategy for social change: “It doesn’t work without social movements. Every great president has been a great president because there’s a social movement to pressure him. FDR wasn’t a great president because he wanted to be. LBJ didn’t pass welfare because he wanted to. We made him.”

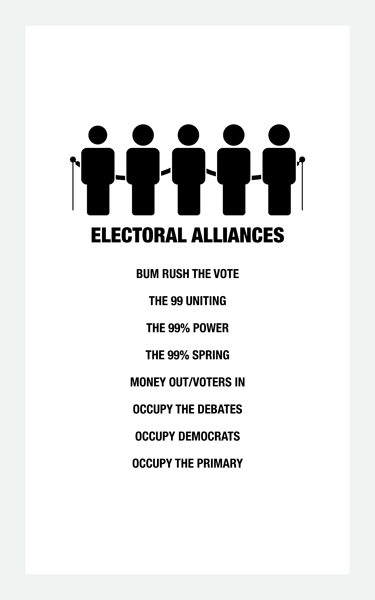

Months ago, the tensions between the partisans and the anti-partisans had fractured OWS’s inner core. On the national stage, the breakup resulted in a bifurcation between Occupy affiliates, on the one hand, and “99 Percent” coalitions, on the other. While the anti-partisans had claimed ownership of the Occupy name, the partisans had joined with labor unions and liberal nonprofits to claim the “99 Percent” identity for their own purposes. Throughout 2012, such electoral alliances (see Figure 8.2) had effectively, if controversially, appropriated the movement’s signature rhetoric.

Figure 8.2 “99 Percent” electoral alliances: spring-fall 2012. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

Just before May Day, MoveOn.org and others had launched the “99 Percent Spring,” reaching out to tens of thousands of activists with some 900 trainings and teach-ins. Shortly thereafter, SEIU and Fight for a Fair Economy had spearheaded the 99 Uniting Coalition and the “99 Percent Voter Pledge.” Publicly, the new coalition proclaimed a mission of “uniting the 99 Percent to use our strength in numbers to win an economy that works for everyone, not just the richest 1 Percent.” In actuality, most of its work was geared toward voter mobilization and high-profile media events concentrated in a handful of key swing states, such as Florida, Ohio, Colorado, and Wisconsin.24

Such Left-labor coalitions kept the politics of “99-to-1” in the public eye throughout the election season. It was through their mediation that Occupy’s tropes, frames, and themes made their way onto the campaign trail. In the process, these self-proclaimed “99 Percenters” helped to rebrand an otherwise lackluster presidential campaign in the image of a populist crusade against Romney, the “1 Percent candidate.”25 99 Uniting, for one, bused hundreds of low-wage workers to the RNC in Tampa, where they rallied and marched against Romney and his running mate, Paul Ryan, with signs that read, “We are the 99 Percent and we are watching.”

In Freeport, Illinois, where the Bain-owned company Sensata was set to outsource 174 jobs, they built an encampment, Occupy-style, outside the factory gates. Weeks later, in the wake of Romney’s infamous remarks inveighing against the “47 Percent” of Americans who are “dependent upon government,” union workers dogged the candidate’s campaign stops with repurposed chants of “We! Are! The 47 Percent!”26

Mitt Romney was not the only target of public anger during the presidential campaign. Oakland and Portland occupiers stormed the local offices of the Obama campaign, demanding a presidential pardon for Wikileaks whistleblower Bradley/Chelsea Manning. Charlotte occupiers pitched tents in Marshall Park for the duration of the DNC, while Chicago occupiers marched from Fannie Mae’s Midwest offices to President Obama’s National Campaign Headquarters, where they delivered a “Bill of Grievances” against what they called the “pro-1 percent policies” of his administration.

As Election Day loomed and the pageantry reached fever pitch, it was clear that the occupiers had been ushered off the national stage. Still, there was a growing consensus, within the movement and without, that they had “changed the conversation.” This was a phrase I heard over and over in my interviews. “I always said the biggest thing that Occupy did was to change the conversation in this country,” stresses Malik Rhasaan, founder of Occupy the Hood. “People that would never talk about issues are talking about them because of Occupy.”

“If you remember, [in 2011], the only issue was the deficit,” says veteran labor activist Jackie DiSalvo. “Well, once Occupy started, inequality became a major issue. [Now] Romney is running on the deficit . . . and Obama is running on inequality. Really, this is an election between a pre-Occupy and a post-Occupy consciousness.”

“Occupy Changed the Conversation: Now We Change the World!”27

Thus begins a call to arms for “Black Monday,” marking the one-year anniversary of that brilliant autumn morning when the occupiers first spread their sleeping bags across the cold stone square. In one sense, the latest rallying cries amount to an exercise in the “optimism of the will” (or, as a onetime organizer once put it, the “audacity of hope”).28 In another sense, they contain a tacit admission of defeat, a recognition of how little the world has changed since September 17, 2011.

For months, the diehards among the diehards have been plotting a dramatic return to the Financial District. Their plans for “decentralized direct action” are designed, as always, to cause maximal disruption. “We will occupy Wall Street with nonviolent civil disobedience,” declares the “Convergence Guide” for “Black Monday,” channeling the old Adbusters propaganda from the summer of 2011. “[We will] flood the area around it with a roving carnival of resistance.” Why the eternal return to Occupy’s point of origin? “Follow the money,” urges the guide. “All roads lead to Wall Street. . . . The world we want to live in [is] a world without Wall Street.”29

Early on the morning of Black Monday, I emerge from the subway to a familiar scene. Two rows of barricades form a ring of steel for blocks around the Stock Exchange. I can see its Georgian marble façade in the distance, draped with a giant Stars-and-Stripes. At each end of the barricades stands a pair of blue shirts, checking the identification of all comers. Behind them, I spot six officers of the NYPD’s Mounted Unit, keeping watch atop their 1,200-pound steeds. Down the block, I see a cluster of white shirts conferring among a crush of bankers and stockbrokers. Other officers hail from the Counter-Terrorism Bureau, or from the Federal Protective Service of DHS.

“Good morning, NYPD!” croons a soprano in a red dress as she sways to and fro outside a Chase bank branch. “We’re here to start the revolution!” But the revolution, it seems, will have to wait, as business proceeds—very much as usual—on both sides of the barricades today.

“Occupy, Year Two,” such as it is, kicks off just blocks away from the site where it all began, with assembly points at Liberty Square (the “99 Percent Zone”), the Ferry Terminal (the “Eco Zone”), South Street Seaport (the “Education Zone”), and the Vietnam Veterans Plaza (the “Debt Zone”). I join in the student debtors’ assembly on the banks of the East River, before the glass-block-and-granite wall memorializing the 1,741 New Yorkers who died in Vietnam. There is something incongruous about this convergence, which has drawn some 200 occupiers to the Veterans Plaza—all but a few of them young, white, and well-dressed, with party hats on their heads, noisemakers in their hands, and streamers affixed to their “Jubilee” signs. All in all, they bear a remarkable resemblance to the crowd that first convened at Bowling Green one year ago.

After some milling and mic-checking, we link arms and wend our way down William Street. Escorted by fifty or more riot police, we snake along the sidewalks in the direction of Exchange Place, where other affinity groups and action clusters await us. From Bowling Green comes another festive bloc, flanked by a brass band playing “Happy Birthday,” and puppeteers carrying larger-than-life renderings of Lady Liberty, the Monopoly Man, and the two leading presidential candidates. From the west comes a more somber procession, chanting the wordless nigunim of the Jewish High Holidays, and carrying paper tombstones representing the nameless victims of financial capitalism. And from the south come packs of “polar bears,” with socks for paws and wool hats for jaws, asserting “Wall Street Brought the Heat/We Take the Street.”

Here and there, other remnants of the 99 Percent movement can be seen scattered along the narrow sidewalks: here, a spirited band of nurses, sporting Robin Hood caps and demanding “An Economy for the 99 Percent”; there, a crew of middle-aged white men in hardhats, one of them waving a “UNION YES” flag, another bearing a “Liberty Tree” festooned with the hats of his co-workers.

Yet, with few exceptions, the occupiers’ onetime institutional allies are conspicuous in their absence. Gone are the labor unions, community groups, and local nonprofits that had once rallied to their defense. Gone are the legions of laborers and teachers, health aides and teamsters, pink-collar servers and white-collar workers, whose numbers had swelled the movement’s ranks. By September 17, 2012, the unions and other erstwhile allies are otherwise occupied. With election season in full swing, it seems, such working-class interest groups are in no mood for street marches—at least, not behind the fraying banner of Occupy Wall Street.

Figure 8.3 “You Cannot Evict an Idea,” Zuccotti Park, November 17, 2012. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

Gone, too, are the community organizations and their disenfranchised constituencies, whose needs have continued to go unmet amid the uneven recovery and ongoing austerity. Over the course of 2012, it seems OWS has grown increasingly disconnected from their concerns, which range from securing housing and employment to stopping “stop-and-frisk” and “the new Jim Crow.”30 What’s more, with so many New Yorkers of color already at heightened risk of arrest and incarceration, organizers could hardly recommend they place themselves deliberately in the path of the police batons. Accordingly, many will find the occupiers of Black Monday to be strikingly unrepresentative of the 99 Percent, in whose name they claim to be speaking.

With Occupy’s coalitions out of commission, it is left to a handful of affinity groups to claim the media spotlight, which, by midday, is already dimming. Before it fades to black, the Financial District will see a final flurry of civil disobedience: a “soft blockade” at a Bank of America branch (“Bust! Up! Bank of America!”); a sidewalk sit-in before the revolving doors of Goldman Sachs (“Arrest the bankers!”); an eruption of “mic checks” and confetti in the lobby of JPMorgan Chase (“All day! All week! Occupy Wall Street!”). The riot police will respond with the usual show of force, with “snatch-and-grabs” and skirmish lines. As the batons come out and the arrests commence, the bankers continue about their business, hardly batting an eye.

After ten hours and 185 arrests, the occupiers who still have their freedom will return to Zuccotti Park for a popular assembly and after-party, billed as a “safe space to practice public dissent.” As the sun sets over the Hudson, and the police take up positions along Broadway and Liberty, the space of the square resounds anew with the repetitive rhythms of the People’s Mic. Fiery speakers crowd the granite steps. Twinkling fingers fill the autumn air. The assembly invokes the old rituals of participation, recalling the glory days of the last American autumn.

But the speakers also evoke a sense of power and possibility, turning this penned-in repository of their inchoate hopes into a point of departure toward a new society: “We have all come here together/As part of a community/That dreams of a better world/That demands a better tomorrow!” (The young woman lets the People’s Mic work its way, in waves, across the space of the square.) “They can take our tents/They can burn our books/They can cuff our hands/But they will never kill the idea.”

“The idea of Occupy will, and must, live on.”