So far in this book, you've worked on individual Web pages. While creating a single page is a crucial first step in building a Web site, sooner or later you'll want to wire several pages together so a Web trekker can easily jump from one to the next. After all, linking is what the Web's all about.

It's astoundingly easy to create links—officially called hyperlinks—between pages. In fact, all it takes is a single new element: the anchor element. Once you master this bit of XHTML lingo, you're ready to start organizing your pages into separate folders and transforming your humble collection of standalone documents into a full-fledged site.

In XHTML, you use the anchor element, <a>, to create a link. When a visitor clicks that link, the browser loads another page.

The anchor element is a straightforward container element. It looks like this:

<a>...</a>

You put the content that a visitor clicks inside the anchor element:

<a>Click Me</a>

The problem with the above link is that it doesn't point anywhere. To turn it into a fully functioning link, you need to supply the URL of the destination page using an href attribute (which stands for hypertext reference). For example, if you want a link to take a reader to a page named LinkedPage.htm, you create this link:

<a href="LinkedPage.htm">Click Me</a>

For this link to work, the LinkedPage.htm file has to reside in the same folder as the Web page that contains the link. You'll learn how to better organize your site by sorting pages into different subfolders on Relative Links and Folders.

Tip

To create a link to a page in Expression Web, select the text you want to make clickable, and then hit Ctrl+K. Browse to the correct page, and Expression Web creates the link. To pull off the same trick in Dreamweaver, select the text and press Ctrl+L.

The anchor tag is an inline element (The 10 Most Important Elements (and a Few More))—it fits inside any other block element. That means that it's completely acceptable to make a link out of just a few words in an otherwise ordinary paragraph, like this:

<p> When you're alone and life is making you lonely<br /> You can always go <a href="Downtown.htm">downtown</a> </p>

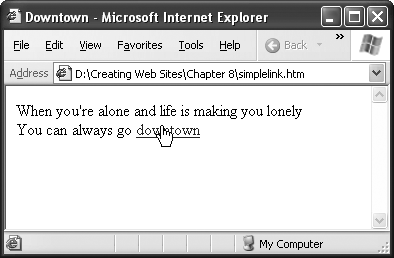

Figure 8-1 shows this link example in action.

Figure 8-1. If you don't take any other steps to customize an anchor element, its text appears in a browser with the familiar underline and blue lettering. When you move your mouse over a hyperlink, your mouse pointer turns into a hand. You can't tell by looking at a link whether it works or not—if the link points to a non-existing page, you'll get an error only after you click it.

Links can shuffle you from one page to another within the same Web site, or they can transport you to a completely different site on a far-off server. You use a different type of link in each case:

Internal links point to other pages on your Web site. They can also point to other types of resources on your site, as you'll see below.

External links point to pages (or resources) on other Web sites.

For example, say you have two files on your site, a biography page and an address page. If you want visitors to go from your bio page (MyBio.htm) to your address page (ContactMe.htm), you create an internal link. Whether you store both files in the same folder or in different folders, they're part of the same Web site on the same Web server, so an internal link's the way to go.

On the other hand, if you want visitors to go from your Favorite Books page (FavBooks.htm) to a page on Amazon.com (www.amazon.com), you need an external link. Clicking an external link transports the reader out of your Web site and on to a new site, located elsewhere on the Web.

When you create an internal link, you should always use a relative URL, which tells browsers the location of the target page relative to the current folder. In other words, it gives your browser instructions on how to find the new folder by telling it to move down into or up from the current folder. (Moving down into a folder means moving from the current folder into a subfolder. Moving up from a folder is the reverse—you travel from a subfolder up into the parent folder, the one that contains the current subfolder.)

All the examples you've seen so far use relative URLs. For example, imagine you go to this page:

http://www.GothicGardenCenter.com/Sales/Products.htm

Say the text on the Products.htm page includes a sentence with this relative link to Flowers.htm:

Would you like to learn more about our purple <a href="Flowers.htm">hydrangeas</a>?

If you click this link, your browser automatically assumes that you stored Flowers.htm in the same location as Products.htm, and, behind the scenes, it fills in the rest of the URL. That means the browser actually requests this page:

http://www.GothicGardenCenter.com/Sales/Flowers.htm

XHTML gives you another linking option, called an absolute URL, which defines a URL in its entirety, including the domain name, folder, and page. If you convert the URL above to an absolute URL, it looks like this:

Would you like to learn more about our purple <a href= "http://www.GothicGardenCenter.com/Sales/Flowers.htm">hydrangeas</a>?

So which approach should you use? Deciding is easy. There are exactly two rules to keep in mind:

If you're creating an external link, you have to use an absolute URL. In this situation, a relative URL just won't work. For example, imagine you want to link to the page home.html on Amazon's Web site. If you create a relative link, the browser assumes that home.html refers to a file of that name on your Web site. Clicking the link won't take your visitors where you want them to go (and may not take them anywhere at all, if you don't have a file named home.html on your site).

If you're creating an internal link, you really, really should use a relative URL. Technically, either type of link works for internal pages. But relative URLs have several advantages. First, they're shorter and make your XHTML more readable and easier to maintain. More importantly, relative links are flexible. You can rearrange your Web site, put all your files into a different folder, or even change your site's domain name without breaking relative links.

One of the nicest parts about relative links is that you can test them on your own computer and they'll work the exact same way as they would online. For example, imagine you've developed the site www.GothicGardenCenter.com on your PC and you store it inside the folder C:\MyWebSite (that'd be Macintosh HD/MyWebSite, in Macintosh-ese). If you click the relative link that leads from the Products.htm page to the Flowers.htm page, the browser looks for the target page in the C:\MyWebSite (Macintosh HD/MyWebSite) folder.

Once you polish your work to perfection, you upload the site to your Web server, which has the domain name www.GothicGardenCenter.com. Because you used relative links, you don't need to change anything. When you click a link, the browser requests the corresponding page in www.GothicGardenCenter.com. If you decide to buy a new, shorter domain name like www.GGC.com and move your Web site there, the links still keep on working.

Note

Internet Explorer has a security quirk that appears when you test pages with external links. If you load a page from your hard drive, and then click a link that points somewhere out on the big bad Web, Internet Explorer opens a completely new window to display the target page. That's because the security rules that govern Web pages on your hard drive are looser than those that restrict Web pages on the Internet, so Internet Explorer doesn't dare let them near each other. This quirk disappears once you upload your pages to the Web.

So far, all the relative link examples you've seen have assumed that both the source page (the one that contains the link) and the target page (the destination you arrive at when you click the link) are in the same folder. There's no reason to be quite this strict. In fact, your Web site will be a whole lot better organized if you store groups of related pages in separate folders.

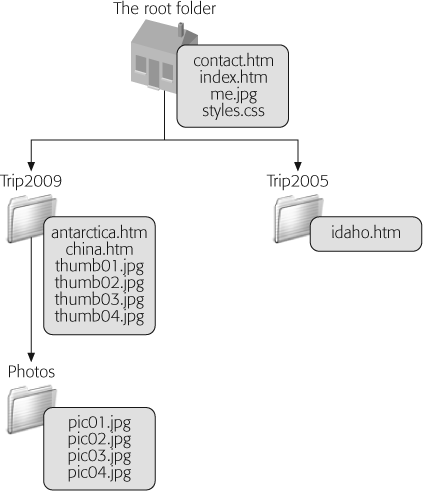

Consider the Web site shown in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2. This diagram maps out the structure of a very small Web site featuring photos taken on a trip. The root folder contains a style sheet used across the entire site (styles.css) and two XHTML pages. Two subfolders, Trip2005 and Trip2009, contain additional pages. The Trip2009 folder holds thumbnail images of pictures taken on one of the trips. For each thumbnail, there's a corresponding full-size picture in the Photos subfolder.

Note

The root folder is the starting point of your Web site—it contains all your other site files and folders. Most sites include a page with the name index.htm or index.html in the root folder. This is known as the default page. If a browser sends a request to your Web site domain without supplying a file name, the Web server sends back the default page. For example, requesting www.TripToRemember.com automatically returns the default page www.TripToRemember.com/index.htm.

This site uses a variety of relative links. For example, imagine you need to create a link from the index.htm page to the contact.htm page. Both pages are in the same folder, so all you need is a relative link:

<a href="contact.htm">About Me</a>You can also create more interesting links that move from one folder to another, which you'll learn how to do in the following sections.

Tip

If you'd like to try out this sample Web site, you'll find all the site's files on the Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com. Thanks to the magic of relative links, all the links will work no matter where on your computer (PC or Mac) you save the files, so long as you keep the same subfolders.

Say you want to create a relative link that jumps from an index.htm page to a page called antarctica.htm, which you've put in a folder named Trip2009. When you write the relative link that points to antarctica.htm, you need to include the name of the Trip2009 subfolder, like this:

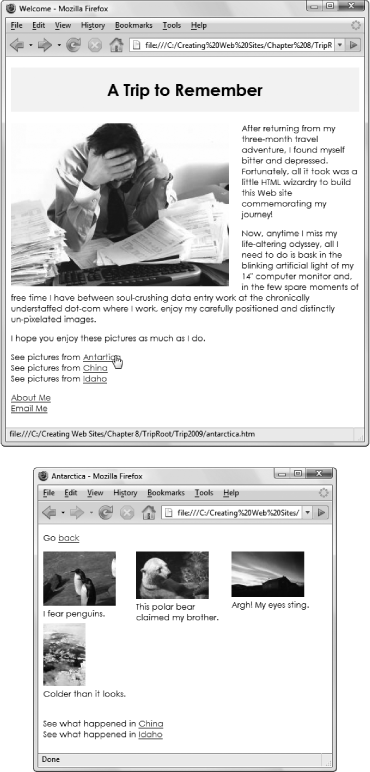

See pictures from <a href="Trip2009/antarctica.htm">Antarctica</a>This link gives the browser two instructions—first to go into the subfolder Trip2009, and then to get the page antarctica.htm. In the link, you separate the folder name ("Trip2009") and the file name ("antarctica.htm") with a slash character (/). Figure 8-3 shows both sides of this equation.

Interestingly, you can use relative paths in other XHTML elements, too, like the <style> element and the <img> element. For example, imagine you want to display the picture photo01.jpg on the page index.htm. This picture is two subfolders away, in a folder called Photos, which is inside Trip2009. But that doesn't stop you from pointing to it in your <img> element:

<img src="Trip2009/Photos/photo01.jpg" alt="A polar bear" />Using this technique, you can dig even deeper into subfolders of subfolders of subfolders. All you need to do is add the folder name and a slash character for each subfolder, in order.

But remember, relative links are always relative to the current page. If you want to display the same picture, photo01.jpg, in the antarctica.htm page, the <img> element above won't work, because the antarctica.htm page is actually in the Trip2009 folder. (Take a look back at Figure 8-2 if you need a visual reminder of the site structure.) From the Trip2009 folder, you only need to go down one level, so you need this link:

<img src="Photos/photo01.jpg" alt="A polar bear" />By now, you've probably realized that the important detail lies not in how many folders you have on your site, but in how you organize the subfolders. Remember, a relative link always starts out from the current folder, and works it way up or down to the folder holding the target page.

Tip

Once you start using subfolders, you shouldn't change any of their names or move them around. That said, many Web page editors (like Expression Web) are crafty enough to help you out if you do make these changes. When you rearrange pages or rename folders inside these programs, they adjust your relative links. It's yet another reason to think about getting a full-featured Web page editor.

The next challenge you'll face is going up a folder level. To do this, use the character sequence ../ (two periods and a slash). For example, to add a link in the antarctica.htm page that brings the reader back to the index.htm page, you'd write a link that looks like this:

Go <a href="../index.htm">back</a>And as you've probably guessed by now, you can use this command twice in a row to jump up two levels. For example, if you have a page in the Photos folder that leads to the home page, you need this link to get back there:

Go <a href="../../index.htm">back</a>For a more interesting feat, you can combine both of these tricks to create a relative link that travels up one or more levels, and then travels down a different path. For example, you need this sort of link to jump from the antarctica.htm page in the Trip2009 folder to the idaho.htm page in the Trip2005 folder:

See what happened in <a href="../Trip2005/idaho.htm">Idaho</a>This link moves up one level to the root folder, and then back down one level to the Trip2005 folder. You follow the same process when you browse folders to find files on your computer.

The only problem with the relative links you've seen so far is that they're difficult to maintain if you ever reorganize your Web site. For example, imagine you have a Web page in the root directory of your site. Say you want to feature an image on that page that's stored in the images subfolder. You use this link:

<img src="images/flower.gif" alt="A flower" />But then, a little later on, you decide your Web page really belongs in another spot—a subfolder named Plant—so you move it there. The problem is that this relative link now points to plant/images/flower.gif, which doesn't exist—the Images folder isn't a subfolder in Plants, it's a subfolder in your site's root folder. As a result, your browser displays a broken link icon.

There are a few possible workarounds. In programs like Expression Web, when you drag a file to a new location, the XHTML editor updates all the relative links automatically, saving you the hassle. Another approach is to try to keep related files in the same folder, so you always move them as a unit. However, there's a third approach, called root-relative links.

So far, the relative links you've seen have been document-relative, because you specify the location of the target page relative to the current document. Root-relative links point to a target page relative to your Web site's root folder.

Root-relative links always start with the slash (/) character (which indicates the root folder). Here's the <img> element for flower.gif with a root-relative link:

<img src="/images/flower.gif" alt="A flower" />The remarkable thing about this link is that it works no matter where you put the Web page that contains it. For example, if you copy this page to the Plant subfolder, the link still works, because the first slash tells your browser to start at the root folder.

The only trick to using root-relative folders is that you need to keep the real root of your Web site in mind. When using a root-relative link, the browser follows a simple procedure to figure out where to go. First, it strips all the path and file name information out of the current page address, so that only the domain name is left. Then it adds the root-relative link to the end of the domain name. So if the link to flower.gif appears on this page:

http://www.jumboplants.com/horticulture/plants/annuals.htm

The browser strips away the /horticulture/plants/annuals.htm portion, adds the relative link you supplied in the src attribute (/images/flower.gif), and looks for the picture here:

http://www.jumboplants.com/images/flower.gif

This makes perfect sense. But consider what happens if you don't have your own domain name. In this case, your pages are probably stuck in a subfolder on another Web server. Here's an example:

http://www.superISP.com/~user9212/horticulture/plants/annuals.htm

In this case, the domain name part of the URL is http://www.superISP.com/, but for all practical purposes, the root of your Web site is your personal folder, ~user9212. That means you need to add this detail into all your root-relative links. So to get the result you want with the flower.gif picture, you need to use this messier root-relative link:

<img src="/~user9212/images/flower.gif" alt="A flower" />

Now the browser keeps just the domain name part of the URL (http://www.superISP.com/) and adds the relative part of the path, starting with your personal folder (/~user9212).

Most of the links you write will point to bona fide XHTML Web pages. But that's not your only option. You can link directly to other types of files as well. The only catch is that it's up to the browser to decide what to do when someone clicks a link that points to a different type of file.

Here are some common examples:

You can link to a JPEG, GIF, or PNG image file (File Formats for Graphics). When visitors click a link like this, the browser displays the image in a browser window without any other content. Web sites often use this approach to let visitors take a close-up look at large graphics. For example, the Trip2009 Web site in the previous section has a page chock full of small image thumbnails. Click one of those, and the full-size image appears.

You can link to a specialized type of file, like a PDF file, a Microsoft Office document, or an audio file (like a WAV or an MP3 file). When you use this technique, you're taking a bit of a risk. These links rely on a browser having a plug-in that recognizes the file type, or on your visitors having a suitable program installed on his PC. If the computer doesn't have the right software, the only thing your visitors will be able to do is download the file (see the next point), where it will sit like an inert binary blob. However, if a browser has the right plug-in, a small miracle happens. The PDF, Office, or audio file opens up right inside the browser window, as though it were a Web page!

You can link to a file you want others to download. If a link points to a file of a specialized type and the browser doesn't have the proper plug-in, visitors get a choice: They can ignore the content altogether, open it using another program on their computer, or save it on their PC. This is a handy way to distribute large files (like a ZIP file featuring your personal philosophy of planetary motion).

You can create a link that starts a new email message. It's easy to build a link that fires up your visitors' favorite email program and helps them send a message to you. Helping Visitors Email You has all the details.