Introduction

The causes and remedies to psychological disorders have long been the subject of debate and ongoing research. Every few years a seemingly new psychotherapeutic approach surges in popularity, only to fade away later as a distant memory. Recently several lines of converging research have identified the wide variety of interactive factors underlying many health and mental health problems. This book synthesizes the already substantial literature on psychoneuroimmunology and epigenetics, combining it with the neuroscience of emotional, interpersonal, and cognitive dynamics, with psychotherapeutic approaches to offer an integrated vision of psychotherapy. The integrative model promotes a sea change in how we conceptualize mental health problems and their solutions.

We explore the multidirectional causal relationships among stress, depression, anxiety, the immune system, and gene expression. The interaction among all these factors has been illuminated by studies examining the effects of lifestyle factors on the incidence of health and psychological problems. There are significant relationships among immune system functions, stress, insecure attachment, anxiety, depression, poor nutrition, poor-quality sleep, physical inactivity, and neurophysiological dysregulation. For example, insecure attachment, deprivation, and child abuse contribute to anxiety and depression in far more extensive ways then was once believed. A complex range of health conditions affect millions of people who seek psychotherapy.

Because we have reached the point in the evolution of psychotherapy where the dividing line between mental health and physical health care has evaporated, we must address the overall health of clients. Physical health and mental health are not just two sides of the same coin as if connected but still discrete dimensions; within and between each dimension are multiple nonlinear feedback loops that constantly affect all aspects of health. An integrated approach necessitates addressing the interdependence of health and behavior in psychotherapy.

Given that psychotherapy will increasingly address health factors, this integration brings those fields of research that had previously been compartmentalized into a robust vision of psychotherapy. I apply this approach to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression to bring the integrative model to life.

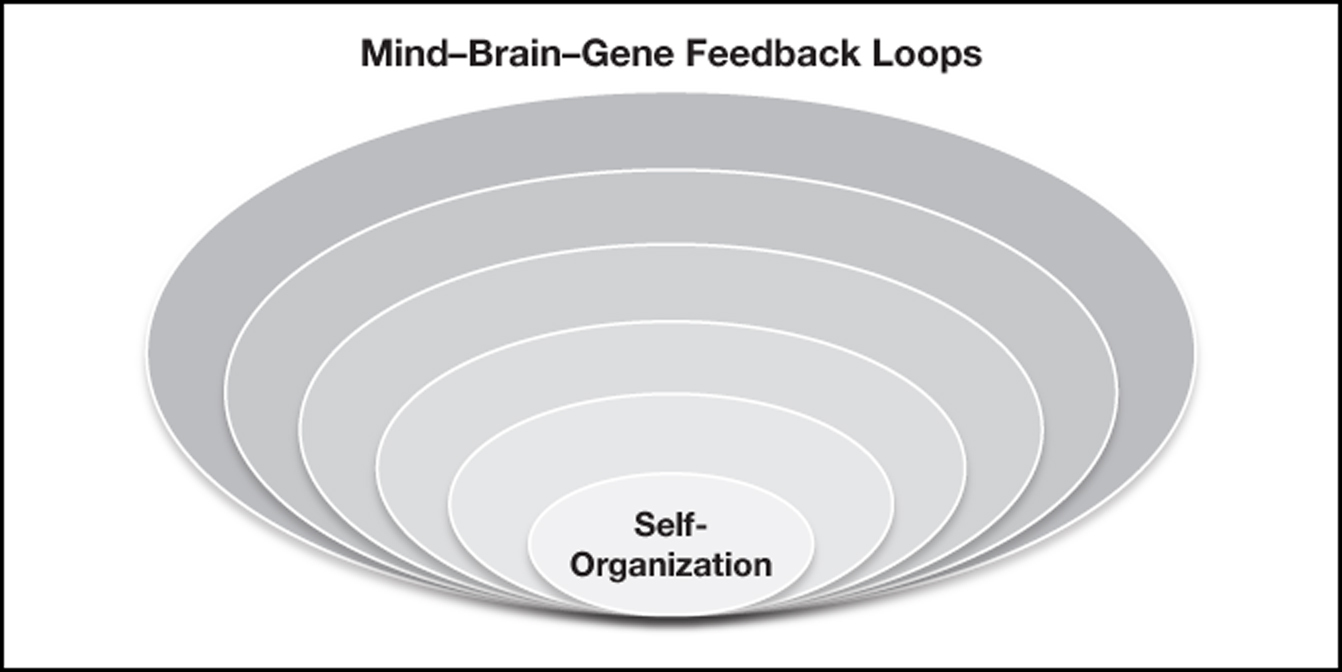

Thus, this book presents a perspective antithetical to reductionism. It explores how the immune system can become dysregulated, how autoimmune disorders are associated with mental health problems, and how those same mental health problems feed back in nonlinear causation to other health problems. For example, while type 2 diabetes increases depression, so too depression exacerbates diabetes. Nor can all mental phenomena be reduced to the neuron or a specific neural network. Thinking, emotion, and behavior feed back to produce brain change. The feedback loops within the mind-brain-gene continuum generate multidirectional causal relationships among the mind, the brain, and genetics as a larger system, not separate entities. Taken together, all these dimensions interact as nonlinear, multidimensional evolving phenomena.

Before the development of the field of psychoneuroimmunology, the mind, the brain, the body, and genes were assumed to function as semi-independent systems with only indirect influences upon one another. The fields of medicine and psychology segregated into specialties, and providers practiced health care separately from one another. They may refer their patients to a specialist in a particular area outside their own narrowly defined expertise to “fix the problem” they had little knowledge of how to address.

Psychotherapy and health care in the twenty-first century are interdependent. No longer can we justify compartmentalizing the domains to specialists by rationalizing that a particular problem is “not my specialty.” Sure, there are and will continue to be health care providers whose experience and training exceed others in particular areas—I would not go to a dermatologist for a second opinion about my heart, neither would I go to a cardiologist about a bunion. My point is that psychotherapists need to know about the factors that are common to poor mental health and poor physical health.

No longer are the factors influencing mental health and general health causes thought to occur through a linear bottom-up causal chain of reactions starting with “bad genes” causing psychological disorders, nor is the semidualist concept that causality is merely a top-down process. The truth is that we are not just the result of top-down and bottom-up factors but also side to side in myriad complex interactions.

During the past few decades efforts have been made to bridge the gaps between mind and brain. The pioneering work by Allan Shore (1999), Dan Siegel (2015), and Lou Cozolino (2014) has bridged the gap between attachment research and interpersonal neurobiology. Ernie Rossi (2002) has long promoted the concept that psychotherapy contributes to gene expression. Lou Cozolino (2014) and I (Arden 2009, 2015) have integrated neuroscience with psychotherapy. In the field of psychoneuroimmunology George Solomon (1987) pioneered the focus on the interactions among the mind, brain, and immune system. This book attempts to integrate all these areas and combine them with the research on habit, meditation, self-care behaviors, and the mental operating networks.

COMPLEXITY

To understand how the multiple factors that contribute to mental health coevolve, we need an interdisciplinary perspective. Complexity theory offers this fresh and inclusive perspective. This theory grew out of systems theory and draws on the natural sciences to explain multilevel interactions and feedback loops.

Feedback loops help promote growth and maintain homeostasis. We cannot become more resilient and durable without them. Positive feedback loops promote growth and boundary expansion, critical for a person’s development. Negative feedback loops help regulate stasis, like a thermostat helping regulate the temperature in the room, or stress tolerance for that person. The dynamic interplay between positive and negative feedback loops is affected by changes in the environment that we encounter and often create. Psychotherapy promotes positive and negative feedback loops to enhance mental health.

These complex feedback loops cannot be reduced to any one factor alone within the mind-brain-gene spectrum. They cause and are caused by each other. And within each subsystem there are multiple feedback loops that maintain stability and change as we adapt to changing conditions in our lives. As such, they are self-organizing systems within the collective interactions that we call a “self.” In this sense, the self is not reducible to the sum its parts; it represents a “self”-organizing process (Arden, 1996). The primary need of complex adaptive systems, such as ourselves, is that we must maintain open interaction with the environment to maintain coherence, complexity—in short, health. As complex adaptive systems we are self-organizing, feeding on biopsychosocial interactions to increase our complexity and adaptability.

We are the result of multiple interacting systems that self-organize through nonlinear leaps to higher or lower levels of organization. “Self”-organization represents self-referential coherence facilitated by the emergence of the mind maintaining openness and durability for of our individuality and constantly evolving interaction with other selves.

The mind is a meaning-making process, both conscious and nonconscious. The mental operating networks construct meaning through their nonlinear interactions and the memory systems. A person’s sense of herself on social, psychological, and biological levels provides the context and meaning through which she experiences the world. These interacting systems are both in flux and stable, such that her mind embraces and promotes the dynamic stability of her sense of self. Psychological disorders form when our dynamic stability breaks down. Whether clients suffer from the emotional chaos of anxiety or the emotional rigidity of depression, psychotherapy aims to help them regain a balance between flexibility and stability.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

The following chapters cover the feedback loops comprising our sense of self and its breakdown. Please note that the cases I describe in this book, although derived from actual cases in my practice, are composites—they do not represent actual sessions, and they use fictitious names. They nonetheless exemplify approaches and dialogue I have found effective in my practice.

Chapter 1: “Self”-Organization

How does the feeling of individuality emerge? How do body sensations, emotion, and cognition interact to self-organize into the emergence of self? Chapter 1 explores the emergence of subjectivity and emotion by describing the mind’s operating networks: the salience, executive, and default-mode networks. The salience network, sometimes called the “feeling network” or “the material me,” involves the somatic sensation and the emergence of emotion. The executive network, sometimes called the central executive or the CEO of the brain, includes working memory, being present in the moment, and complex decision making. And the default-mode network, sometimes called the “story brain,” involves self-referential thought, fantasy, daydreaming, and rumination, often about other people and our place within our relationships. It draws up episodic memories and reflects on the past as well as projects into the future. Finally, the interactions and dysregulations of implicit and explicit memory are described as self-referential information systems. They form the fabric of the self and undergo updating based on experience. The mind’s operating networks use information from the long-term memory systems for continuity, stability, and “self”-organization.

Chapter 2: The Social Self

Building on interpersonal neurobiology, this chapter discusses how we thrive when nurtured or develop psychological disorders when we are not. Kindling the social brain networks in psychotherapy promotes not only mental health but also general health. The mind’s operating networks may develop dynamic balance and stability or become imbalanced in response to our relationships. Positive relationships are vital for health as evidenced by impaired cardiovascular reactivity, blood pressure, cortisol levels, serum cholesterol, and natural killer cells. Research shows that early deprivation undermines affect stability later in life; people who are lonely or maintain unhealthy relationships develop neurocognitive problems associated with inflammation and abnormal neurochemistry.

Close relationships support longevity as measured by the brain’s capacity for neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. Cultivating secure relationships, such as through psychotherapy, promotes stress tolerance by building feedback loops in the neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous systems that minimize anxiety and lift depression. Psychotherapy can work within these social brain systems to build or rebuild the capacity for regulatory affect to deal with the challenges of daily life. By empathetically kindling the social brain networks, therapists can help clients develop security and thrive interpersonally.

Chapter 3: Behavior-Gene Interactions

This chapter begins with the exploration of the health and mental health ramifications of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. This and other studies of its type highlight the interaction between early adversity and epigenetic affects expressed later in life in ill health and mental health. The rapidly evolving field of epigenetics reveals how gene-environment interactions bring about the expression or suppression of the genes. While the suppression of genes can occur through the process of methylation, gene expression can occur through a process called acetylation. Of critical importance to an integrative approach to psychotherapy, factors such as attachment, adversity, and lifestyle behaviors can have a major impact on the expression or suppression of genes.

Parental or caregiver neglect and adverse childhood experiences have been shown to suppress genes regulating cortisol receptors in the hippocampus, making it more difficult to turn off the stress response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis later in life. With a less viable negative feedback mechanism in place, stress tolerance is diminished. In the extreme, low cortisol receptors are associated with suicide. Women who initially experienced poor attachment early in life tend to have decreased estrogen receptors later in life and are less attentive to their own babies. On the other hand, people with secure attachment have higher levels of cortisol receptors and are better able to deal with stress. This negative feedback mechanism works effectively to increase stress tolerance. Because therapists can help clients turn on and off genes through changing their behavior, anxiety and/or depression can be more effectively addressed therapeutically.

Another way that behavior affects genetic processes in response to the environment and behavior is at the telomere level. Telomeres, which comprise the ends of the linear chromosomes, generally shorten with cell division, age, and illness. The availability of an enzyme that adds nucleotides to the telomeres, called telomerase, has been linked to health and psychological factors. While stress and depression have been associated with shorter telomere length, specific lifestyle behaviors have been associated with longer telomere length.

Chapter 4: The Body-Mind and Health

This chapter begins by illustrating how the interfaces between the immune system, mind, and the brain affect mental health. For example, chronic inflammation is significantly associated with a broad range of health and mental health problems, including devastating effects on mood, cognition, and social withdrawal. Inflammation can result from adversity and the several dimensions of the interfaces between mind, brain, and body. In fact, chronic inflammation is strongly associated with anxiety, depression, and cognitive deficits, including dementia. One of the routes by which inflammation occurs is by increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines contribute to and have a bidirectional causal relationship with anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment by altering the levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, as well as a variety of other effects.

Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors cause epigenetic effects that dysregulate the immune system, causing autoimmune disorders, depression, and anxiety. Of significant current importance to mental health providers is that the United States leads the world in obesity, autoimmune diseases, metabolic syndrome, and ranks number two in type 2 diabetes. Consistent with this pandemic is that two-thirds of the people in the United States are overweight. Numerous studies show that fat cells leach out toxic amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the associated ill health conditions are destructive to mental health. They can lead to a spectrum of symptoms, including fatigue, social withdrawal, disturbances in mood, cognition, sluggish movements, and depression, which are also strongly associated with anxiety and trauma. Therefore, psychotherapists must assess and address the psychoneuroimmunological feedback loops affecting their clients’ mental health.

Chapter 5: Self-Maintenance

This chapter describes how self-care practices can undermine health and mental health, leading to anxiety and depression. Failure to maintain self-care represents more than merely symptoms of psychological problems; it often is the cause of and leads to averse epigenetic effects, including shortening of the telomeres. Psychotherapy by necessity promotes a firm foundation of a balanced diet, sleep architecture, and regular aerobic exercise. The psychoneuroimmunological effects underlying these factors either support or undermine physical and mental health.

Regular aerobic exercise is a powerful antidepressant and anxiolytic. Exercise also delays cognitive decline and dementia through a variety of processes, including significantly lower inflammation. Exercise promotes a healthy brain in many other ways, too, including the release of neurotrophic factors that promote healthy capillaries, glucose utilization, and neurogenesis.

Mental health is profoundly affected by diet. For example, regular consumption of simple carbohydrates, trans-fatty acids, and the wrong fats creates insulin insensitivity, chronic inflammation, and diminished neurotransmitter levels. A diet high in simple carbohydrates increases advanced glycation end-products, accelerating the formation of plaques and tangles in the brain. Prior to developing dementia, people become depressed and have cognitive deficits, and often seek psychotherapy. A poor diet also changes gut bacteria, which is associated with leaky gut, inflammation, and depression. Though there are literally hundreds of different types of bacteria in the gut, 90 percent fall in two broad categories: Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. If the F/B ratio is skewed in the direction of the Firmicutes (fed by simple carbohydrates), leaky gut tends to occur, with increases in inflammation.

While sleep accounts for roughly one-third of our lives, poor-quality sleep can either destabilize mood and cognition. Poor-quality sleep dysregulates levels of stress hormones such as cortisol, which at high levels impairs the hippocampus and the frontal lobes. Adverse epigenetic effects, marked increases in inflammation, and shortened telomeres are associated with impaired sleep.

Chapter 6: Motivation, Habits, and Addiction

Adaptive and maladaptive habits are learned behaviors coded into our implicit memory systems. They affect our motivation, often involving formation of procedural and emotional implicit memory. Procedural memory is facilitated by the striatum and nucleus accumbens, so they become automatically associated with pleasure and/or the relief of discomfort.

Habits that become addictions can play a bidirectional causal relationship with anxiety and depression. From an integrative approach to addressing addictions, anxiety, and depression, it is important that we do not conceptually separate them as “diseases.” The rigid categories dictated by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals, psychotherapy books, and seminars generally stay clear of addressing chemical dependency, while addictions providers defer to mental health providers for people with “psychiatric” disorders. Integrated psychotherapy goes beyond the one-dimensional conceptual frames of “dual diagnosis” and “co-occurring disorders.” Addictions, also including those that are not chemical in nature, such as to gambling and computer games, hijack the dopamine circuits and the nucleus accumbens and striatum neural networks.

By understanding the neuroscience underlying habits, therapists can more effectively help clients boost motivation and overcome maladaptive habits. For example, most addictions downregulate dopamine receptors, making the range of potential positive experiences narrow to the addictive behavior. People who had experienced multiple adverse childhood events tend to have a reduced range of potentially positive experiences, which represents a setup to develop addictive behaviors. When stressed, they may engage in their go-to source of pleasure, their addiction. Expanding the range of positive behaviors expands the number of medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens, making this part of the brain better able to put the brakes on an automatic habit generated by the striatum.

Chapter 7: Stress and Autostress

This chapter explains how the multidimensional stress systems have been reconceptualized. The terms allostasis and allostatic load help us more fully appreciate how resiliency and adaptability (allostasis) can be developed and the breakdown and dysfunction (allostatic load) can be minimized. Allostatic load involves the breakdown of regulatory feedback systems between health conditions and mental health, contributing to the development of anxiety and depression. The dysregulation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems can throw the immune system out of balance, contributing to affective and cognitive deficits. Meanwhile, dysregulation in the neuroendocrine system can further undermine the stabilizing feedback loops, resulting in first hypercortisolism then hypocortisolism with increases in inflammation, contributing to cardiovascular system damage as well as more systemic deficits to the central nervous system.

The formation of the anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety, phobias, and panic hijacks the stress reaction systems so they get turned on inappropriately. A consistent pattern of false alarms transforms to an autostress disorder, an anxiety disorder. Stress promotes anxiety when the stress system is turned on too often and signals danger when there is none. Often people who experience multiple stressors then become hypervigilant and avoidant of the symptoms of stress. From this perspective an anxiety disorder feeds on the stress response system. Like autoimmune disorders that hijack the immune system so that it turns back on the body instead of protecting it, autostress disorders transform the stress response system into something that attacks the self rather than protecting it.

This chapter also describes how therapy can temper the hyperactivity of the fast track to the amygdala, which underlies overresponses to events with unrealistic and immediate threat. Clients can be taught to put the brakes on the fast track to the amygdala by activating functions in the prefrontal cortex, which increases the slow versus the fast track. Therapy promotes activation of the left prefrontal cortex with the engagement in approach behaviors and exposure to alleviate anxiety, depression, and promote allostasis.

Chapter 8: The Trauma Spectrum

This chapter explores a range of trauma-induced responses and therapeutic approaches while it attempts to transcend the “brand names” and theoretical cul-de-sacs to find common denominators among them. From so-called simple to complex trauma in etiology, and from hypervigilance to disassociation in response, therapeutic approaches must address the nature of the dysregulation of memory systems.

Given that people who experience a life-threatening trauma may go on to later develop posttraumatic stress disorder, it is important to explore the developmental and sociocultural factors and adverse childhood experiences that contribute to the lack of resiliency and vulnerability. A variety of epigenetic, psychoneuroimmunological factors are associated with risk. If an individual has poor social support, or on another level, if he has a smaller than normal hippocampus, maintains high levels of cortisol and norepinephrine in the evening, and has high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, he tends to be more vulnerable to developing posttraumatic stress disorder.

During the last few decades a variety of somatic-based therapies have emerged, such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, Emotional Freedom Techniques, Somatic Experiencing, and Sensorimotor Integration. They have competed theoretically with evidence-based practices, such as prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy. An integrative psychotherapeutic approach finds the common factors and incorporates a synthesis of exposure and somatic approaches.

Chapter 9: Transcending Rigidity

Depression is not a singular disorder with one etiology. The links between depression, inflammation, adverse childhood experiences, and early-life deprivation are interrelated with the incidence of illnesses such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Depressed clients with a history of early-life trauma demonstrate significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6, and higher activation of tumor necrosis factor.

Typically, hyperactivation of the amygdala is associated with anxiety disorders. Yet an enlarged and hyperactive amygdala is sometimes associated with depression. The activation of the amygdala appears to normalize after successful treatment for depression. Similarily, the role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in agitated depression has gained considerable attention because it is often elevated in depressed clients, as well as in suicide victims.

Complex adaptive systems are by nature open systems. We need interaction with the environment to grow and change. Closed systems, by contrast, are isolated, with no exchange of information with the environment. They are forced to feed on themselves. From a psychological perspective depression, with its associated behaviors of withdrawal, isolation, and lack of effort, may be thought of as promoting a closed system. People suffering from depression can be thought of as stuck in a kind of psychological rigidity. When there is a failure to achieve sufficient input, information, or energy, the depressed person begins to lose complexity. Through reversing these dysregulations she can develop open and activated interactions with her environment, and transcend the rigidity of depression.

Chapter 10: Mind in Time

The placebo effect represents one of the most provocative phenomena in health care, including psychotherapy. Several studies have revealed the placebo effect occuring in the brain. When patients believe that they are receiving a pain medication, endogenous opiates are released in the brain. The placebo effect illustrates how belief changes the brain and thus how we experience our body. Not only does the placebo effect represent a so-called top-down process, but also interactions with bottom-up sensations form a top-down feedback to change those sensations. For example, when we note “side effects” of a medication, we may assume that the medication is beginning to work to produce the “main effect.”

The positive psychology research on forgiveness, compassion, and gratitude are explored in Chapter 10, with respective to their effect on mental health. Similarly, optimism and an attitude of acceptance are associated with resiliency. Together, these attitudinal perspectives play a major role in promoting mental health.

During the past few decades, mindfulness has been subsumed into the mainstream as well as within the “third wave” of therapies, such as acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and mindfulness-based stress reduction. While this addition to preexistent therapies has made important contributions, there remains considerable misinformation regarding the research. Many well-meaning therapists assume that simply promoting mindfulness is the end-all. Meanwhile, millions of other potential readers turn away from mindfulness and books about it, worrying that an interest in Buddhist practices conflicts with their faith in theologies such as Christianity or Islam. There are similar methodologies within those traditions, which this chapter explores.

Meditative/mindfulness practices produce a range of profound health effects, as illustrated in a number of studies in neuroscience. To understand mindfulness, contemplative prayer, and related practices, it is important to note that for most people working memory lasts for 20–30 seconds. On the other hand, we all spend 30 percent of our waking hours in our default-mode network, daydreaming, planning for the future, or ruminating about the past. It is not that the default-mode network represents a dysfunctional process. Rather, it can be the source of creativity and healthy self-reference. This chapter describes the balance between executive, salience, the default-mode networks and how to stay in time to improve psychotherapeutic success.

The plethora of psychotherapy theories of the twentieth century, claiming the exclusive explanation and methodology, has given way to an integrated model of the twenty-first century. The following chapters will explore the many interconnected feedback loops that contribute to mental health or ill health. Research in neuroscience, epigenetics, and psychoneuroimmunology has shown that genes can turn on or off and that disease processes and mental health are significantly related to our lifestyle and experience. Our brain, immune, and stress response systems adapt to our experiences. Taken together, psychotherapy seeks to enhance mental as well as physical health. This book explores those interconnections and attempts to contribute to the integrative model of the future.