INTRODUCTION |

“Let’s Get behind Old Glory and the Church of Jesus Christ”: |

Forget the idea of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan being an organization that flogs and tars and feathers people. Nor is it an organization that sneaks around into people’s back yards trying to get something on somebody. We do, however, bring the transgressor to justice through the duly constituted officers of the law. Let us look beyond the horizon and see this thing from a national standpoint. Let us see to the influx of unfit foreign immigration. . . . Let’s get behind Old Glory and the church of Jesus Christ.

—IMPERIAL NIGHT-HAWK (1924)1

In the long course of bigotry and violence, the Klan has evoked the rebelliousness of the Boston Tea Party, the vigilantism of American pioneers and cowboys, and the haughty religion of the New England Puritans. In its corruption of American ideals, it has capitalized on some of the best-loved aspects of the American tradition.

—WYN CRAIG WADE (1987)2

In the hot Georgia summer of 1913, Mary Phangan, an employee of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, Georgia, traveled to the factory to get her check. The day was Confederate Memorial Day, and “little Mary Phagan,” as the Georgia press dubbed her, missed the parade held in honor of the Confederacy and the newer South. The next morning, Newt Lee, the night watchman, found her brutalized, dead body in the basement of the factory. The case of who murdered Phagan played out in the Georgia press, and her death proved to be apt fodder for the newspapers and their editors, who focused upon her youth, her innocence, and her job as a factory worker. Her image graced the front pages alongside lengthy descriptions of her unfortunate death. The iconic image of little Mary Phagan emphasized her youthful appearance, vulnerability, and her whiteness. Her faint smile and blonde hair tied in bows were incongruent with the horror of her murder and the possibility of rape. For the newspapers and Georgia’s male citizenry, the death of little Mary Phagan required not only justice but also swift vengeance for the murderer of one so young and supposedly innocent. She became a warning to other girls, women, and their parents of the danger lurking for defenseless white women. Phagan’s murder emerged as the tragic tale of a young white woman in the South as an unprotected member of the labor force, as well as of the obvious failure of white men to protect their families, especially their young daughters, from such a gruesome fate. The sensational murder gained coverage not only in the local Georgia press but also in the surrounding states and the larger nation. The Columbus (Georgia) Ledger editorialized that “whatever the investigations may disclose, this we know at once, that the victim was a brave little working girl, striving to take up her burden in life and to win her daily bread. This is an appeal to public conscience in this one fact which should not be disregarded. That she was in some way a victim to her own youth and beauty makes this tragedy complete.”

The tragedy of Mary Phagan showcased the growing presence of teenagers and children in Southern factories and the dire and uncertain working conditions under which many young women labored. Phagan’s symbolic import outweighed her individual life. The Ledger continued that “these defenseless little women” needed much protection and care.3 Speculation ran wild in the Georgia press about whether the murderer would even be brought to justice. The decree for her murderer’s death reverberated in the newspapers because of this loss of “one pure and innocent life.”4

The Atlanta police detained several male suspects for Phagan’s murder, but they finally settled upon Leo Frank, a Northern Jew who was the manager of the National Pencil Company, as the culprit behind Phagan’s gruesome murder. Frank’s nervousness, his outsider status, and the testimony of another employee, Jim Conley, an African American janitor, made him the prime suspect. Conley’s testimony during the subsequent trial cinched the general solicitor Hugh Dorsey’s case. Conley testified about Frank’s supposed lewd sexual relationships with other young female factory workers as well as his own role in moving Phagan’s dead body to the basement at Frank’s insistence. His testimony revolving around Frank’s supposed sexual encounters shocked and fascinated the press, who provided the sordid details to the general public.

In August of 1913, a jury convicted and sentenced Frank to death for the murder of Phagan, and Frank’s lawyers appealed the conviction. By June of 1915, Governor William Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison because of his own doubt about various inconsistencies in evidence and the questionable witness testimony.5 The threat of mob violence appeared real during Frank’s trial, and the governor feared the impact of potential violence on the climate of the trial and the subsequent ruling. By and large, the citizens of Georgia, however, were not persuaded by Slaton’s doubt and ruling on the trial, and some Georgians believed that the governor allowed a miscarriage of justice by changing the death sentence to life imprisonment. At demonstrations supporting the execution of Leo Frank, supporters sang “The Ballad of Mary Phagan” (1915), in which Phagan’s murder was perpetrated by Frank, who was judged for his crime in the afterlife. The ballad proclaims, “Come, all you jolly people, / Wherever you may be, / Suppose little Mary Phagan / Belonged to you or me.”6 The ballad expressed the opinion of many Georgians, who wanted justice for Phagan’s death. Those who sang the verses of the ballad assured little Mary Phagan’s place in heaven with the angels and Frank’s future residence in hell.7 It is not surprising with the previous threats of violence, then, that some men decided to take Frank’s life into their own hands and guarantee his punishment.

The Knights of Mary Phagan, a group of local men ranging from politicians to members of the Phagan family, organized, planned, and subsequently lynched Leo Frank. In August of 1915, a group of twenty-five men broke into the state prison in Milledgeville, Georgia, where Frank was serving a life term, and kidnapped Frank, delivering him to Phagan’s hometown of Marietta, Georgia, to be lynched. The Knights hanged Frank in front of a gathering crowd as retribution for Phagan’s death. Georgian newspapers were quick to report the details of Frank’s “mashed and disfigured body” and the “clamoring mob.” The Columbus Sun-Enquirer described with relish the mob’s attempts at mutilating the body: “The crunching of flesh could be heard above the shouts to stop.”8 National news outlets did not report with the same glee the lynching of Frank. The New Republic ran a poem channeling little Mary Phagan’s position on her alleged murderer’s death: “You care a lot about me, you men of Georgia, not that I am dead. . . . You have broken into a prison and murdered a man that I might be avenged. . . . It is like what the preacher told me about Christ: People hated Him when He was alive. But when He was dead they killed man after man for His sake.”9

While many white Georgians celebrated the death of Frank as fitting retribution for the murder of a young white girl, others in the nation decried the travesty of Frank’s fate. One rabbi proclaimed, “The lynching of Leo Frank is an atrocious horror. . . . The whole Nation is humiliated by this sickening tragedy. The whole nation expresses its horror.”10 Yet the nation read and consumed newspaper accounts of Frank’s lynching at the hands of vengeful white men. While some reports lamented Frank’s fate and others celebrated his righteous death, the gruesome details appeared in both. Frank was a lingering lesson, which centered upon white men taking justice and, of course, punishment into their own hands. Frank’s lynching metamorphosed from a grisly lynching into a moral stand for local communities, national culture, and the protection of the vulnerable white women. The death of little Mary Phagan and the lynching of Leo Frank primed Atlanta, the larger state of Georgia, and more largely the nation for the rebirth of a white men’s movement from the recent past, the Ku Klux Klan. A reactionary populist and Georgia newspaper editor, Tom Watson even suggested that a newer version of the order could restore “home rule.”11 The Knights of Mary Phagan paved the way for the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

An ex-minister, William Simmons, answered the call for rebirth and created the second incarnation of the Klan. His inspiration appeared in the form of D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation (1915), based on Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905), a romanticized rendition of the Reconstruction Klan. Dixon, a Southerner and a minister, preached a “gospel of white supremacy.”12 The Clansmen showcased the Klan’s role as the savior of the South. Griffith created a three-hour film on twelve reels at a record cost of $110,000 and renamed the film Birth of a Nation.13 Like the novel, the film portrayed the Klan as the heroes of the South, who triumphed over the “animalistic” blacks that threatened to annihilate their culture. The film generated as much controversy as admiration, and for many white Americans, it confirmed their fears about African Americans. The romantic view of the Klan appealed to white America and affirmed a past that had not occurred. The KKK emerged from both film and novel as the “savior of the white race against the criminality of the black race.”14 In early 1915, Simmons, a fraternalist and former Methodist minister, was in a car accident that kept him bedridden for three months.15 Simmons drew figures of Klansmen, created a new organizational structure based on the previous 1867 order, and developed new terminology for the fraternity.16 When he regained his health, Simmons constructed a new Ku Klux Klan in an Atlanta atmosphere charged by anti-Semitism in the aftermath of the lynching of Leo Frank.17 In October 1915, Simmons recruited thirty-four members to become his Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which he later incorporated. On Thanksgiving Day, Simmons and nineteen of his Knights marched up Stone Mountain and lit a cross on fire.18 The burning cross marked the beginning of the second order of the Klan. However, a dentist, Hiram Welsey Evans, eventually wrested control of the beloved order from Simmons. Evans, the newly appointed Imperial Wizard, continued Simmons’s vision of an advanced fraternity.

Such is the standard story from Frank’s demise to Simmons’s creation to Evans’s control. This narrative binds the lynching of Frank to the stellar rise and fall of the second Klan. But what is missing is not the 1920s Klan’s dedication to nation, the rights of white men, and the vulnerability of white women but the prominent place of religion, specifically Protestant Christianity, in the Klan’s print culture, fraternal ritual, and theatrical displays. When the Klan’s vision of Protestantism is placed at the front and center of an analysis, a different presentation of the order emerges that illuminates the dominance of the Klan’s racial, religious, and intolerant views in America from the 1910s through the 1930s. In the many tellings and retellings of the Klan story, narrators mention Simmons’s religious involvement, but it is not essential to the story. Simmons was formerly a minister who created a new Klan firmly enshrouded in the language of Protestantism. For the first Imperial Wizard, God had smiled upon America. It was momentous that he founded the Klan on Thanksgiving Day, a day of celebration of the Pilgrims, who came to the New World in search of religious tolerance. As the angels had smiled upon the Pilgrims, so they did upon the new order.

Faith was an integral part of that incarnation of the order. Simmons articulated the religious vision, which Evans and many Klan lecturers (often ministers) continued. The Klan, for Simmons and Evans, was not just an order to defend America but also a campaign to protect and celebrate Protestantism. It was a religious order. The popular story, however, neglected the place of everyday religion within the ranks of Klansmen and Klanswomen and instead focused on the Klan’s vitriol toward Catholics, Jews, and African Americans. The focus on Old Glory, the flag, and patriotism resonated in various tellings, yet the emphasis upon the dedication to the “church of Jesus Christ” remained underplayed and underanalyzed. Protestantism became secondary in descriptions of the Klan because of the order’s apparent nativism, racism, and violence. The Klan gained a following because of its twin messages of nation and faith, and the fraternity progressed because of members’ commitment to its religious vision of America and her foundations.

Moreover, those twin messages resounded because of social change in the United States. Immigration, urbanization, and the internal migrations of African Americans made the Klan’s white, patriotic, and Protestant message appealing. From 1890 to 1914, over 16 million immigrants arrived in the United States, and 10 percent of those immigrants were Jewish. As historian Jay Dolan reported, a vast majority of those immigrants were Catholics from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Poland. In reaction to immigration and World War I, nativism emerged as a popular response to “hyphenated” Americans. Immigrant groups who did not support the war were even more suspect.19 As sociologist Kathleen Blee noted, “The Klan’s underlying ideas of racial separation and white Protestant supremacy . . . echoed throughout the white society of the 1920s, as religious and racial hatreds determined the political dialogue in many communities.”20 White supremacy was a common belief in the early twentieth century, but the Klan’s political action, public relations campaigns, and the production of material artifacts identified it as a distinct movement.21 By 1918 there were fifteen chapters of the new Klan. With rising popularity, Simmons, and later Evans, sought to eliminate the violent image of the Reconstruction Klan without much success.

Paramilitary movement to defend the hallowed Southern Way of Life.

The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan emerged in 1866 in Pulaski, Tennessee. Six Confederate veterans claimed they organized a club to play “pranks” on the residents of Pulaski to uplift the spirits of the war-torn region. The first Klan was primarily motivated by concerns about Reconstruction’s effect on Southern social structure. As such, it particularly targeted African Americans, “carpetbaggers,” and other Northern whites for the unsettling of Southern life. The “club” created their name from the Greek word kuklos, meaning circle, and they added the word “klan” to represent their Scotch-Irish ancestors.22 The first Ku Klux Klan was a supposed social organization for white men. Immediately, they adopted a white uniform with “tall conical witches’ hats of white cloth over cardboard [that] completely concealed their heads,” which “exaggerated the height of the wearer, adding anywhere from eighteen inches to two feet to his stature.”23 The costumes mimicked the ghosts of the Confederate dead. However, the Klan’s pranks were not innocent because members targeted freed blacks. The pranks were reminiscent of the decades-old actions performed by planters and overseers to frighten slaves into submission.24 The popularity of the Klan grew in Tennessee, and by the end of 1866, the jokes had turned violent and occasionally deadly. In 1867 the ever-growing group needed structure and a popular leader that would spread the “social club” throughout the South. At a Nashville convention, the Klan reorganized and specified its aims of chivalry, humanity, mercy, and patriotism.

The early Klan saw Southern whites as victimized by Reconstruction, and members opposed any who destabilized their worldview, including blacks and supporters of blacks. A historian of the Klan, Michael Newton, has argued that in April 1867 the Klan shifted from a club to a “paramilitary movement to defend the hallowed Southern Way of Life.”25 The “Invisible Empire” divided into sections by region, and Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a lauded Confederate veteran, became the official leader of the first Klan.26 By 1868 the Klan began raiding the homes of African Americans and supporters of black enfranchisement, interfering with elections and crafting a public image through parades as well as cryptic warnings. The Reconstruction Klan targeted African Americans because of the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted African American men the right to vote. Many of the black victims of the Klan were voting Republicans.27 The Klan confronted the “violent and brutal” officials who upheld black civil rights while victimizing white men and women.28 Whites saw themselves as victims of Reconstruction and a shifting political climate, and the Klan reacted to any threat to white dominance.

Also in 1868 the Klan had spread into Kentucky, Missouri, West Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Southern Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. The Freedmen’s Bureau and eventually the federal government became concerned with their raids and violent actions.29 In 1871 Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act to protect voters and the Fourteenth Amendment, and with the federal crackdown on their actions the Klan declined. The Invisible Empire dissipated. However, the presence of the Klan had forever marked the Southern imagination, and William Simmons adopted the larger heritage of the Klan for his newer version, but he attempted to avoid the violent legacy. By June of 1920 Simmons approached the Southern Publicity Association to advertise his organization in order to modify its image. The association’s owners, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Clarke, presented the Klan as a fraternal Protestant organization that championed white supremacy as opposed to marauders of the night. Their efforts proved effective. Membership increased, and the Klan claimed chapters in all forty-eight continental states.30

By 1924 membership peaked at four million members as Americans pledged their support to the order, wore robes, lit crosses, and marched in parades.31 Despite the large membership of the order, scholars, the media, and the general public relied on stereotypes of Klansmen as backward, rural people who lacked education, refinement, and tolerance. That portrayal claimed that Klansmen loathed societal changes, lamented their class status, and embraced their anger as a motivating tool for their activism. Anger and frustration motivated the second Klan’s theatrics and political campaigning. Writing in the 1920s, John Moffatt Mecklin popularized that particular portrayal of Klansmen, which has remained the most common characterization of the order throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Mecklin’s Klansmen embraced their supposed rural roots as well as fundamentalist Christianity to right the social wrongs; fundamentalism, then, became the backbone of the order and motivated Klansmen in their quest to restore the nation.

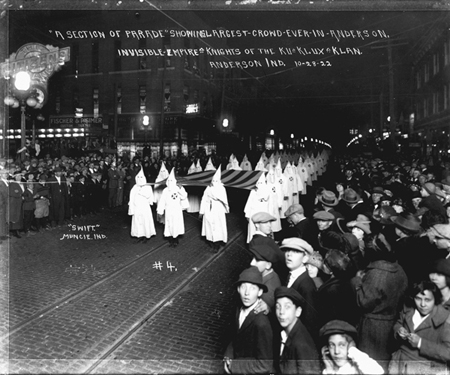

Parade at Anderson, Indiana, 1922. The photographer claimed that this was the largest crowd ever gathered in Anderson. The 1920s Klan often par ti cipated in parades and other public events to bring attention to the order’s twin commitments of Americanism and Protestantism. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

More recent studies of the order contradict this particular presentation of Klansmen, and occasionally Klanswomen, as backward, rural, uneducated, and fundamentalist.32 These studies demonstrate that Klansmen were bankers, lawyers, dentists, doctors, ministers, businessmen, and teachers. Most of the membership was firmly of the middle class and had access to education. Klan members were Quakers, Baptists, Methodists, Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ, and United Brethren, to name only a few.33 They were highly critical of liberal Protestant theologians who used historical criticism and science in biblical interpretation. Klansmen were more evangelical than fundamentalist. The order was more rooted in mainline Protestantism than the stereotype recognizes. Moreover, the 1920s Klan was a populist movement that attempted to reform so-called societal ills with religion and politics.34 Geographically, the Klan emerged in the rural South, the urban North, the Midwest, and the Pacific Northwest. There were klaverns in Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, as well as in Indiana, New Jersey, Colorado, and Oregon. Rural and urban, educated and working class, the order proved more diverse and mainstream than those early popular stereotypes allow. Klansmen and Klanswomen were very similar to their neighbors, but they chose to join the order to communicate their distaste and poignant concern with the path of the nation.

In its heyday, the second incarnation of the KKK produced multiple newspapers and engendered flashy displays of membership ranging from outdoor naturalization ceremonies to marches and parades. The organization built membership from “ordinary, white Protestants,” who embraced Klan events, like picnics and pageants, and read Klan pamphlets, newspapers, novels, and flyers. In that way, the portrait of Klansmen as white-robed terrorists who haunt the dreams of all of their enemies ignored the full rendering of Klan experience. That portrait sidelined the Klan to the margins of American history despite its large membership and cultural influence. By labeling the order as a fringe movement of terrorists, the nefarious elements of the movement appear in historical narratives without explorations of its broader appeal to white Protestants. Yet its numerical strength and popularity require a reevaluation of the order and its place in our narratives to see how such a movement fits within our tellings and retellings of American history, especially American religious history.

To examine the Klan is to examine ourselves.

Klan historian Kenneth Jackson claimed that “to examine the Klan is to examine ourselves.”35 For Jackson, the second revival of the Klan (1915–1930) was representative of American culture rather than a peripheral movement of extremism. To understand the 1920s Klan as central to narratives of American history and American religious history calls into question narratives of Protestant progress, the origins of nationalism, relationships between religion and race, and the often hidden presence of intolerance. Jackson’s provocative statement demonstrates the need for a critical study of the 1920s Klan to understand how Klansmen and Klanswomen were part of the religious mainstream. The Ku Klux Klan is the center of this study because it is a hate movement with the longest history in the United States, a remarkable amount of print culture, and the most organizational revivals in multiple historical periods and places. Various movements of men and women have reenvisioned the order to meet their pressing social concerns. The second wave of the Klan lasted from the 1910s through the 1930s, but most activity occurred in the 1920s.36 That revival lamented the presence not only of African Americans but also of Catholics and Jews, and its leaders openly presented the order’s principles to members through Klan newspapers and magazines as well as the national press. Members embraced Protestant Christianity and a crusade to save America from domestic as well as foreign threats.

Indiana’s First Public Initiation, 1922. Indiana Klansmen in full regalia observe a public initiation into the Invisible Empire. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

The Klan of the 1920s would be the last unified order.37 Because of unity and popularity, the second order has generated the most scholarly ink and sometimes ire. As mentioned earlier, the second Klan was distinctly different from its predecessor, the Reconstruction Klan, as well as the successive waves of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Klan revivals. One explanation for that distinction is that the second revival was the most integrated into American society. The membership was composed of white men and women dedicated to nation, the superiority of their race, and Protestantism. Most histories briefly note the religious lives of Klansmen and Klanswomen in order to focus on the racism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Semitism, and violence of the order. While it is clear that the 1920s Klan was racist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic, the order’s members were indicative of mainstream prejudice of the time period. Their prejudices were not uncommon, but their methods were. In his White Protestant Nation, Allan Lichtman argues convincingly that the Klan was one of several conservative movements in the 1920s that “shared a common ethnic identity: they were white and Protestant and they had to fight to retain a once uncontested domination of American life.”38 He sees the Klan as a part of the trajectory of American conservatism, which also included the American Legion, the Daughters of the American Revolution, various proponents of scientific racism, business associations, and other Protestant organizations. He further notes that “the prohibition of vice, anticommunism, conservative maternalism, evangelical Protestantism, business conservatism, racial science and containment, and the grassroots organizing of the Ku Klux Klan” created a “stout defense of America’s white Protestant, free enterprise civilization.”39 The Klan was just one component of a larger antipluralist campaign in America that sought compulsory moral reform. For Lichtman, the Klan and these other movements were the foundation of the American Right. The order’s religion and politics were similar to its contemporaries. If the Klan is a part of the conservative trajectory, then it makes no sense to sideline the order’s significance and historical presence in the 1920s. Instead of focusing on the order’s difference, perhaps the focus should be on the order’s similarities to other members in their local, regional, and national communities.

What made Klansmen and Klanswomen unique was their dedication and their adoption of print and material methods to further white supremacy and Protestantism. Their methods, not their beliefs, make this incarnation of the order different from their neighbors. The religious nature of their methods and print needs much more exploration. Klan print culture is often discarded as propaganda, rather than considered a resource for Klan beliefs, ideologies, and theologies. This disconnect between Klan print and actual Klan beliefs happens for a variety of reasons. Most important, the neglect of the 1920s Klan’s print occurs because this instantiation of the order is viewed through the lens of its predecessor and the Klans of the mid- to late twentieth century and twenty-first century. The Reconstruction Klan and its modern brethren were and are blatantly violent and racist. They both spewed vitriol and committed acts of terrorism and mayhem—as did the 1920s Klan.

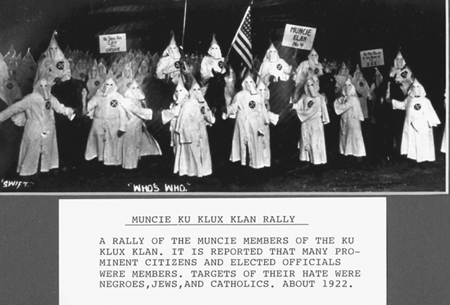

Muncie Ku Klux Klan Rally, c. 1922. The photograph’s caption was “Who’s who,” in reference to the large number of prominent Indiana Klansmen who belonged to the order. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

The close connection of these Klans to racist rhetoric and violence means that all Klans are interpreted in a similar vein. It is hard to look at the 1920s Klan and not connect it to the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama (1963), in which three African American girls lost their lives, or the Klan initiation murder in the recent past (2008). The Klan in the American imagination is bound to crosses, robes, violence, and terror, and I am not seeking to rehabilitate that image. The image stands rightly so, but reliance upon this popular interpretation alone overshadows the complicated place of religion, specifically Protestantism, in the Klan’s long history.40 Understanding the central role of religion helps scholars understand better the motivation and appeal of these movements beyond simplistic presentations of frustration and anger, which remain popular excuses for membership in such movements. Moreover, examining movements like the Klan also suggests the ways that religion can inform ideologies of intolerance, violence, and terror, as well as bolster the commitment of members by relying on a more ultimate cause for such insidious agendas.

In its corruption of American ideals, [the Klan] has capitalized on some of the best-loved aspects of the American tradition.

It is not surprising, then, that the scholarship on the Klan, as well as other hate movements, often emphasized violence, racism, gender ideology, and nationalism with religion as a secondary or tertiary concern. Often interpretations sought to define why Klansmen, and occasionally Klanswomen, embraced the order, but sometimes such analyses neglect what members of the order actually say about their experiences and hesitate to present the Klan in its own language.41 There are, of course, dangers in presenting the order at face value, in that the scholar might become just a mouthpiece for a particular hate movement. There is also the issue of how to use the Klan’s words and artifacts without heavy skepticism.42 Building on John Moffatt Mecklin’s Ku Klux Klan: The Study of an American Mind (1924), much scholarship described Klansmen as frustrated and resentful because of the poor conditions of their rural lives. Mecklin argued that Klansmen barely maintained control over their own lives, feared anything foreign, especially immigrants, and voiced paranoid concern about the influence of foreign ideas and peoples to transform local as well as national cultures.43 Mecklin analyzed the psychology of Klansmen and claimed that their pathology could be essentialized to a fear of difference. Klan scholar Leonard Moore noted, “Like Mecklin . . . and other writers of the 1920s . . . all agreed that Klan radicalism could be traced to the benighted culture of rural, small-town America.”44

Agrarian, white men faced disenfranchisement because of modernity, new social norms, and increasing racial and religious diversity of the nation. Mecklin’s model of the Klansman’s pathological anger and frustration still remains popular even in contemporary discussions of the Klan, though analysis of more generalized frustration becomes increasingly particular and nuanced in a contemporary context. The role of class emerged as central to the motivations of Klansmen, reiterating the frustration model by claiming that Klansmen encountered disadvantages because of socioeconomic status and societal change. Abrupt changes in gender norms added to the Klan’s frustration because Klansmen reacted vehemently to flappers, women’s suffrage, and men’s dwindling status in larger society. All of those factors led white men to form an order to protect white women from African American men and women’s supposed inherent weaknesses.45

Yet explanations of Klan frustration prove inadequate as an approach for elucidating why the Klan rose in popularity at such stellar speed. To link rampant frustration to the order’s intolerance and hatred does not account for why those men (and women) expressed their anxiety and concern in extraordinary ways (the burning of crosses, dressing in robes, etc.) while their contemporaries did not. Members might have been, and likely were, resentful of societal changes, but that likelihood alone does not predict the complexity of their reactions. Moreover, the emphasis on frustration and anger bolstered analyses and commentary about Klan violence and brutality. Much Klan scholarship has overestimated KKK violence by assuming that brutality was endemic in the order.46 The second order’s rhetoric did not employ a terminology of violence; rather, leaders and editors carefully crafted their public opinions to avoid obviously violent content. Studies of the Klan highlighted the cruelty and white supremacy of the order by providing excruciating details of the violence against African Americans, race traitors, and others in the various and distinct Klan revivals. These actions clearly made the order appear reprehensible, dangerous, and menacing. For instance, a history of the Klan in Florida characterized the order by its use of lynching. This regional examination of the Klan demonstrated that Florida Klans were the most violent permutations of the organization. Yet the attempt to bind the order to various lynch mobs revealed that violence, at least in Florida, could not be directly attributed to Klansmen. The history of violence that began with the Reconstruction Klan and continued to current manifestations of the order was actually more suggestive of the regional character of the Florida Klans than the national traits of the order.47 The legacy of Klan violence is very real, but the tendency to solely focus on such violence should not hide other motivations for continued membership and participation in the order.

Some social historians in newer studies of the Klan, particularly Leonard Moore and Shawn Lay, attempt to broach their subjects both compassionately and nonjudgmentally: Klansmen and Klanswomen become ordinary citizens primarily, and their affiliations with the order are secondary. The second order of the Klan emerges as an anomaly compared to the other orders. This Klan was more representative of 1920s culture because its actions and ideology reflected the white supremacy of American society. Klansmen, above all, were average folks who belonged to a fraternity, not a villainous organization. In examinations of Klan activity in different states and regions of the West, it becomes clear that the KKK was not as aggressive in the West as the instantiations in the South. Moore, in particular, challenges previous presentations of the Indiana Klan by arguing that the klaverns of the Hoosier State were just populist gatherings of white men. Furthermore, the Indiana Klan relied upon “ethnic scapegoats,” particularly Catholics and Jews, as symbols of more complex fears.48 For Moore, the Indiana Klansmen participated in figurative prejudice to assuage anxiety about foreign neighbors. The fraternal order operated much like a support group for white Protestant men who believed that their values were under assault.

Unfortunately, these case studies might also be more indicative of regional character than the national order. There is no doubt that populism characterized the 1920s Klan, but symbolic intolerance does not seem to accurately characterize the order’s vehement rhetoric attacking Catholics, Jews, and African Americans. The sole focus on populism obscures the order’s role in violent action and terror. While examining only the Klan’s violent outpourings hides its religious and political endeavors, the examination of just populism obscures the reality of the order’s ethnic and religious intolerance. The members of the order were white supremacists in a culture of white supremacy, but they acted quite differently from their neighbors.49 Populism and local differences do not quite explain why the Klan gained membership so quickly or why they relied on theatrical means to express their ideologies. This empathetic approach remains a minority voice in the field of KKK history because other scholars continue to foreground the Klan’s nativism, nationalism, and racial supremacy rather than the similarities of the order to the mainstream.50

It is clear that scholars deployed myriad factors to explain the motivation for the 1920s Klan and the order’s contemporary manifestations, but among those religion served in a secondary and more often rhetorical role. Some scholars recognized the order’s historical engagement with Christianity, yet this did not guarantee analysis of religion as a motivating factor for Klan actions. Generally, these studies cataloged religious affiliations. No matter what the cause for the order’s rise and fall, most monographs on the Klan at least cite that the order was a nominally Protestant movement. Scholars document the denominational affiliations of members, purport the ties between the Klan and fundamentalism, highlight the recruitment of ministers and the popularity of church visits, and note the particular relationship of the women of the KKK and Protestantism.51 Yet the use of the term “Protestant” to classify the Klan does not guarantee an exploration of the devotions, rituals, practices, scriptures, or theologies of the 1920s Klan. Scholars adopted the term “Protestant” as comprehensible to all readers, but in most works the term was neither defined nor examined critically. The Klan was Protestant, but discussion of what that exactly means is missing. Other scholarship argues that the religion of the Klan and other hate movements was patently “false” religion.52 This tiresome declaration of false religion obscured the commitment of members to the religious vision of the order and marginalized the centrality of that vision to the Klan’s appeal. The order relied on religious systems ranging from a white supremacist version of Protestantism in the 1920s to today’s Christian Identity movement.53

This desire to set up boundaries between true and false religion does nothing to further the scholarly enterprise. More important, this distinction marks the religion of the hate movement as somehow not religion, which proves problematic for several reasons. First, this allows for the lack of attention to Klansmen and Klanswomen’s religious leanings. If they are not authentically religious, then their motivations are not impacted by religion at all. Second and more important, presenting the religion of the Klan as false religion allows an assumption that religion is somehow not associated with movements and people who might be unsavory, disreputable, or dangerous. Religion is at best ambiguous, which means that it can be associated with movements we label “good” or “bad,” but limiting the place of religion does not mean that religion, specifically Christianity, cannot be associated with the Klan or white supremacist movements more generally. A proper examination would explore how the religion of the Klan impacted its members, practices, and politics without engaging the so-called falsity of the order’s religion. This association with false religion means that what Klansmen and Klanswomen wrote and said about their religious backgrounds becomes disingenuous and less credible than other people’s writings and declarations.

Klansmen and Klanswomen avidly promoted their affiliations within Protestantism. The second revival of the order continually articulated its allegiance to Protestantism, nationalism, and white supremacy. Christianity played an essential part in the collective identity of the order, and neglecting religious commitment ignores a crucial self-identification. Religious faith washed over the pages of the Klan newspapers, fictional books, pamphlets, and speeches. Dedication to Protestantism emerged as a crucial part of membership and as the foundation for the order’s ideals, principles, and even intolerance. To understand how religion influenced the order, it is necessary to appreciate how faith was foundational to characterizations of nation, race, and gender in that moment in American history. To examine the Klan forces us to take a hard look at the development of American nationalism and competing visions of nation. The assumption that religion was a rhetorical tool rather than a legitimate system of belief and practice means that the Klan’s racial and gendered agendas often obscured religious motivation for actions and rhetoric. The hesitance about the relationship between religion and racial and/or religious hatred suggests that a religious studies approach is sorely needed in the literature. True or false, legitimate or illegitimate, the Klan still upheld its Protestantism. Identifying the Klan as white and Protestant does not further scholarship unless we can unearth how members employed and comprehended those terms. This book highlights how the Klan crafted its religion, nation, and race, and the varying interrelationships between those components, while taking the order’s world-view quite seriously.

In addition, references to the Ku Klux Klan in larger narratives of American religious history are few and far between. Generally, religious historians presented the common narrative of nativism and intolerance of the Klan. In Sydney Ahlstrom’s magnum opus, A Religious History of the American People, the Klan appears in its opposition to immigration.54 In his grand narrative of American religious history, Martin Marty argued, “The revival of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s included an anti-Catholic note which attracted only the extreme reactionaries in some southern and midwestern white Protestantism.”55 In both works, the Klan proved to be a marginal movement of reactionaries rather than an authentic interpretation of Protestantism. The narratives ignored the Klan’s requirement of church membership in a Protestant denomination, the centrality of churchgoing in print, and the Klan’s creative theological endeavors. Moreover, the order launched campaigns to unify Protestants across denominational lines in its effort to save America from immigration and other “evils.” The Klan was a part of the religious story of the nation, whether its members were likable or not.

Perhaps it is easier to relegate the order to subcultural status rather than to attempt to integrate the Klan into American religious history. The religious history of America would appear different to us if we viewed it through the eyes of a Klansman or Klanswoman. How might narratives of American religious history be told if the Klan was integrated rather than segregated? If a white supremacist movement proves pivotal rather than fringe, then what might happen to our narratives of nation? Would American religious history appear differently or would it stay shockingly similar? By inserting the Klan into narratives of American religious history, the relationship between faith and nationalism comes to the foreground. In crafting its vision of the nation, the order understood “true” America in religious, racial, and gendered terms. To move the Klan from subculture to a legitimate component of the white Protestant mainstream illuminates the complicated, fractious, and contradictory process of creating and claiming national identity. American nationalism materializes in its particular relationship to Protestant identities, and the exclusivist discourse of nation emerges in a study of the Klan.

By interpreting the 1920s Klan in light of its Protestantism, one must rethink the decision to relegate distasteful movements to the sidelines of history. For Klan historian Kenneth Jackson, such was remarkably problematic because the Klan was “typically American.” He wrote that the Klan gained power because it capitalized “on forces already existent in American society: our readiness to ascribe all good or all evil to those religions, races, or economic philosophies with which we agree or disagree” and our ability to “profess the highest ideals while actually exhibiting the basest of all prejudices.”56 To assess the Klan as a religious movement shows how the order, like many other movements, struggled with conceptions of nation, race, gender, and even its professed Protestantism. By showcasing the similarity of Klan members to their contemporaries, who perhaps did not possess the white robe or light a fiery cross but found resonance in the order’s white supremacy, it becomes clear that the 1920s Klan resonated with the larger American public.

[The Imperial Night-Hawk] will continue to speak . . . as the courier of the Imperial Palace to the various Klans of the nation.57

Sociologist James Aho argues quite convincingly that the hate movement is a reading culture: the members of white supremacist movements learn and embody the rhetoric and ideology from their encounters with print.58 Klan print journals, speeches, fictional works, newspapers, pamphlets, position papers, and broadsides document the religious worldview of the Klan. These are the official sources of the order as opposed to diaries, journals, or letters from individual Klan members. Words helped create Klansmen, and the order’s print is my primary route of study. This narrative, however, is an official one that primarily focuses on the words of Klan leaders, lecturers, klavern members, and anonymous editors of Klan newspapers. The official and ideal worldview of the Klan demonstrates how the leadership, and often members, attempted to supply a unified, structured vision of the order. The sources do not invite a thick ethnographic description of what it actually meant to be a Klansman or Klanswoman in the second incarnation. But using print culture deciphers how leaders constructed those roles as well as documented the occasional opposition of members to the order’s dictates and demands. The print provides the KKK’s portrayal of the faith and the nation, which shows the order’s relentless dedication to its twin messages in ways that have not been achieved before. As mentioned previously, the Klan print often engenders suspicion from researchers and general audiences alike. Yet this suspicion underplays one of our most valuable primary sources from the Klan: its own newspapers. By taking the order’s texts seriously through close and careful readings, one can see how the members, readers, and leaders were an avid part of creating the order through reading. The words signaled truth; print became the order’s reality. By relying on print reflections, my approach offers more of a snapshot of what was expected of a Klansman (or a Klanswoman) in the 1920s instead of standard historical progression. Using Klan newspapers showcases how text functioned in the order’s defense of nation and Protestantism, as well as the active interplay between members and leaders in the creation and maintenance of order. The printed word served to illustrate the order’s hopes, and fears, to its members and eventually a larger public.

In January 1923 the Imperial Kloncilium, the governing body, ordered the creation of an official publication, and so the Imperial Night-Hawk was born. Whether or not it was created because of the aforementioned public relations campaign is not clear.59 The weekly ran during the peak of Klan membership, from 1923 to 1924. The circulation of the paper in 1923 is unknown. However, by the end of 1924 the editors of the Night-Hawk claimed that 36,591 copies were printed each week, with subscriptions in all forty-eight continental states.60 Each Klansman gained access to a subscription when he became a member. The editor described the weekly:

It goes to our army camps and to many of our battleships. It goes to numerous newspapers, to hundreds of ministers, and untold numbers of school teachers. It has told the truth in times when the Klan was not allowed to state its case through the public press. It has explained the beliefs of the Klan in a most wonderful fashion. It has performed its duty well. Without one cent of cost to those receiving it, the Imperial Night-Hawk has freely and gladly been sent, with the compliments of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., to all those who desired its weekly visit.61

The Kourier Magazine (1924–1936) replaced the Night-Hawk in December 1924, and the weekly became a monthly in the transition. Another popular Klan weekly, The Dawn: The Herald of a New and Better Day (1922–1924), boasted a circulation of 50,000 in 1923 and even charged ten cents a copy on the newsstand.62 There were other news magazines, including the Fiery Cross, an Indiana newspaper, and the Official Bulletins of the Grand Dragons, a series of regional bulletins that reported on local and national events.

The print culture, then, is an invaluable entrée into the Klan’s worldview because it allows for a glimpse of public persona and sometimes the private communications to members. Klansmen made the newspapers for other Klansmen. They were not supposed to be publicly available, which meant the publications served to remind Klansmen of their duties, the expectations of the order, and the order’s positions on various issues ranging from evolution to Catholics to the public schools. Studying Klan print gives access to the inner workings of the order, which highlights how leaders and editors constructed religion, nationalism, gender, and race for their community. Examining those texts demonstrates how the Klan wanted to make Klansmen into white, manly, Protestant Americans who both selflessly served and defended the ideals of the organization. Reading the publications embedded Klan ideology and identity into the bodies of Klansmen as well as their minds.63 The order’s hope was to create Klansmen who longed to be the chivalrous Knights the order desired. That, however, was a tenuous process—to convince readers of the Night-Hawk and other print to live up to the ideals the pages described. Editors and leaders sought to shape the membership, but the members often had different ideas, which led to strident denunciations, warnings, and sometimes threats from the Klan leadership regarding their behavior. Klan print served as a method of communication between the national organization and each individual Klansman.

Cover, The Imperial Night-Hawk (1923–1924). The national newsweekly of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. It later became the Kourier Magazine, a monthly. Author’s collection.

Both print culture and the act of reading are methods of communication—either transmission or ritual communication.64 Communication as transmission means that a variety of media passed new ideas to readers, viewers, and listeners. The ritual communication, however, proposed that no new information was actually presented to readers; rather, media reaffirmed a particular worldview. The ritual process maintained, reproduced, or transformed the reality of the reader rather than furnishing new ideas. Print, then, functioned to inculcate a sense of community among readers, who already shared similar ideas, beliefs, or practices. The Night-Hawk, Kourier, and Dawn all served as a means to instantiate the Klan’s worldview and to verse readers in the order’s goals. By reading a Klan newspaper, members embraced its politics, ethics, and actions, and they assented to its portrayal of faith and nation.

American religious historians explore the function of print culture as a method of community building for various religious groups, from reading in early America to evangelical Christian attempts to craft ideal religious readers. Certain books, particularly the Bible, provided cultural scripts and themes for how reality was constructed. Reading always occurred in “cultural fields,” which ensured that reading was never a purely individual act; rather, reading functioned as a common activity that bound together religious peoples and confirmed their faith worlds.65 Communities could be created, maintained, and destroyed in print. The printed page furnished tools for readers to create their own communities in novel ways. In religious publishing, nineteenth-century evangelical publishers believed, and hoped, that meaning passed directly from text to reader with no interference or interpretation. Unfortunately for those publishers, cultural contexts heavily influenced how readers experienced texts. Despite the publishers’ hope for ideal readers who would embrace the religious grace of the Bible or John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), readers haphazardly followed the publisher’s goals. Despite the tension between religious publishers and their audiences, some people did “properly” read the spiritual works and embrace religious community.66

Evangelicals, in particular, embraced the power of the word. The print culture of evangelicals was their method to define the boundaries of their religious worlds, to circumscribe the members of the faithful, and to unify the church.67 Nineteenth-century evangelicals constituted a “textual community,” in which publishers, authors, and readers defined the practices. These religious readers gained a sense of collective identity by participating in textual communities that provided clear boundaries for the faithful. Print clearly functioned as ritual communication for religious movements, and the Night-Hawk (and later Kourier) operated in comparable ways for Klansmen because it reinstated a familiar worldview. It served as a textual community that supplemented meetings, rallies, and parades. Reading was a method to become a better member and engage more fully with the ideals of the order. However, the Night-Hawk’s anxiety about members’ activities signaled that readers defined their own Klan communities despite what editors and leaders articulated upon the printed page.

The editors claimed the centrality of the Night-Hawk and the Kourier in Klan culture. The Night-Hawk, in its own words, was the “only recognized national organ of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” and it was the “sole and only official publication,” which meant that “statements to the contrary or claims of this official recognition on the parts of others” were without basis.68 More important, the editors of the Night-Hawk, representatives of the Klan press, affirmed their positions as the “shock troops of the Klan armies.” They protested against “utterly ruthless forces, who had attempted to hush the voice of the Protestant press.” Those editors threw “their own money and personalities into the cause.” They wrote that the newspaper had fought the first half of the battle, and it was “up to the Klansmen of the nation to help them make good.” The weekly urged that “these newspapers are fighting your fight Klansmen, and you wade in and aid them.”69

These newspapers bolstered the Klan. It was the responsibility of members to read, ascertain, and embody the ethics of the order. The practice of reading solidified notions that Klansmen were Christian Knights who upheld the law of the land and protected the faith. Both the Night-Hawk and the Kourier illuminated what mattered the most to the second Klan. They permit entry into a worldview that has been mischaracterized and misunderstood to condemn the Klan for its actions. Using Klan print documents the experiences of editors, leaders, and ordinary Klan members in the fraternity and the larger world. The print culture showcases the close alignment of the order to its contemporaries. It also demonstrates not only the religious foundations of the Klan but also the complicated relationships between religion, nation, gender, and race in the early twentieth century. To see the Klan members as citizens rather than villains narrates a more complex American story, and to imagine Klansmen in such a way requires a deliberate method to place their words in juxtaposition with their more insidious actions.

If I wanted to know what Masonry stands for I would not go to its enemies, but to the Masons themselves. . . . The best way to find out just what the K.K.K. stands for is to go to their own published platform. If anyone can contradict their statement let him come forward with evidence.70

In his Invisible Empire in the West (1992), Shawn Lay argued that Klan studies must align with the dominant trends in social history so that Klansmen and Klanswomen can be studied compassionately and objectively like their contemporaries.71 The Invisible Empire, like other organizations, political movements, and fraternities, deserved a sensitive, thoughtful study similar to those of more benevolent historical subjects. Sociologist Kathleen Blee, however, notes that more empathetic approaches to the Ku Klux Klan, and the hate movement generally, verge on the dangerous because such approaches could ignore the devastating effects of such movements on members as well as our larger society.72 Blee warns that describing the normativity of Klansmen and Klanswomen downplays the Klan’s violence and hatefulness. Such scholarship, then, presents a “false” sense of those groups and their respective missions. Yet the enterprise becomes even more complicated when we consider the religious faith of the Klan as an addition to the study. The Klan’s claim of Protestantism begs the question of whether its religion should be portrayed as Protestantism simply because they assert Protestantism or whether the order’s religion should be treated differently. The Klan is clearly a movement that gives even casual readers of history pause. It is clear that the Klan historically could be judged as bad or harmful, but studying this movement differently from more approachable and benign movements seems to suggest a particular historical standard that assumes deception on behalf of its members. The lingering question is whether scholars should treat insidious and hateful groups as unique from other historical subject matter. Much literature on the hate movements declares the unsavory nature of its subjects, and this approach clearly colors the methods for studying historical actors deemed dangerous.

In principle, Lay is right about the need to focus on Klansmen and Klanswomen as ordinary citizens. Klan members were not much different from their neighbors and friends, with the important exception that their hatred for certain others motivated them to commit acts of violence, economic terrorism, theatrical displays, and other more subtle forms of discrimination. However, the need to make Klan members appear ordinary is not my main goal, because Lay’s work, among others, showcases the normality of the Klan in a number of communities. Re-creating the Klan’s ideal vision of white Protestant America allows me to document how Klansmen and Klanswomen engaged and embodied intolerance and religious nationalism in rallies, marches, and protests, and, more important, through print and reading. While Lay is correct that these men and women were not wholly evil, their ideal world, their textual community, highlights how their religious vision and their commitment to intolerance impacted the Klan’s discussions of the American nation. Engaging Klan print allows for me to reconstruct how members and leaders maintained the order and its vision of America through text and reading.

Gospel According to the Klan presents the official worldview of the 1920s Klan.73 Leaders and members alike shared and negotiated the Klan’s Protestantism and nationalism, and religion is a part of the social system that provides a set of scripts for its adherents.74 Stepping into the worldview of the Klan illuminates what such scripts are and how they function for the order’s members in their actions, beliefs, and lives. Klan print introduces those scripts in an ideal fashion that favors leaders’ and editors’ opinions and neglects any form of dissent. The official portrait demonstrates the complicated boundaries between the sacred and profane in lives of Klansmen and Klanswomen. Klan studies have explored much of the profane, and a small bit of the sacred, but they have not approached how both are interwoven in the lives of Klan members. Scholarly reticence about how the sacred and profane interact hides the sacred aspects of Klan life.

To settle into the Klan worldview, I employ ethnographic methods to document, describe, and interpret. According to James Clifford, ethnography has the ability to make the ordinary strange and the strange familiar. Ethnography highlights the need for reflexivity and sensitivity to one’s subjects. In the current ethnographic turn, ethnographers reach beyond a scientific model of studying subjects through a “microscope” and embrace a more dialogical model, which allows the subject to speak for him- or herself. Historian Robert Orsi argues for intersubjectivity in which the scholar places her world in direct dialogue with the culture studied to see similarities and differences. That transformative process allows for an awareness of one’s own culture.75 With its uplifting of informants, ethnography contains the risk that scholars might become the mouthpiece for those we study. Kathleen Blee has argued that the romantic assumptions embedded in ethnography and oral history, especially the desire to empower informants and tell their stories, should not apply to hate groups. For Blee, the question is why would anyone want to empower the Klan? She noted that to empathetically connect with the Klan violates the required boundaries for researchers, who work with so-called unloved groups.76 Her main concern was that empathy and rapport might make scholars complicit in the “horrific” agendas of Klan members via description and study.

While Blee’s concerns are legitimate, I would note that the study of unloved groups problematizes the focus on empowerment and empathy in ethnographic methods and oral history. Blee suggests a heavy dose of skepticism when handling unloved groups because of their obviously malevolent actions and intentions. However, I would suggest that ethnographic methods should apply skepticism to all informants rather than just those who make us uncomfortable. Ethnographic work should not be a venue to redeem our subjects, likable or not, but rather a method to understand how their worlds function for better or worse. Ethnographic methods allow glimpses of the Klan’s world in a particular historical movement and how that world might operate. Disgust at the order’s actions might make us feel better, but that emotion does not allow for an understanding of how Klansmen and Klanswomen create and sustain their lives. It is not hard to imagine why many scholars refuse to work with unloved groups. In his work on conspiratorial worldviews, Michael Barkun complicates the view on how scholars should handle groups that are strange, bizarre, or downright hateful. “Failure to analyze” these groups “will not keep people from believing them.” Moreover, Barkun writes that the study of “certain odd beliefs does not signify my acceptance of them.”77 Ann Burlein, in her study of the Christian right and Christian Identity, describes the ambiguity of projects in which we might be opposed to our actors, historical or otherwise. Her solution was to “see with” her conversants, which allowed her to engage but not slip into relativism when confronting their violence and intolerance. She strives to portray their words and actions but not to become complicit in their political agendas. According to Burlein, it is important to study those who make us uncomfortable, in spite of ambiguity and possible danger, because keeping silent or ignoring those we disdain could make those we oppose much stronger.78

For Karen McCarthy Brown, ethnography is neither for the faint of heart nor those in need of moral clarity.79 To enter the world of ethnography is to enter the world of moral ambiguity. An ethnography of the Klan is not only morally ambiguous but also ethically challenging. The use of empathy on those who disgust us is an interesting problem. Examining the hate movement in particular by engaging how they see themselves is a large risk for a scholar who has to balance the Klan’s worldview with historical incidents of hate and intolerance. Moreover, the study of these movements seems to force scholars into a position of judgment, in which the scholar must declare the evil intent and behavior of all of those involved. Scholars moralize and judge before they even begin to engage with the Klan’s larger history and contemporary presence. In his revised edition of Salvation and Suicide, a study of the mass suicide at Jonestown, Guyana, David Chidester argues that as a scholar his place was not to judge the events at Jonestown. He claims we should not give in to the temptation to moralize, but rather strive to understand how a religious worldview functions for its inhabitants. He employs “structured empathy,” a form of empathy molded by interpretative categories such as myth, symbol, and ritual. That particular method supposedly opens up a connection with the worldview of others and further allows the scholar to engage imaginatively with her actors to understand the appeal and logic of the religious movement.

While Chidester’s form of empathy appears worthwhile, it is equally as problematic as Blee’s skepticism. It forces engagement without recognizing the risks of engagement. First, as Chidester argues, it is necessary to see how religious worlds function for adherents. Previous scholarship has attempted to do this but often fails because of the overemphasis on the deplorable nature of unloved groups. Examining the unacceptability of a worldview often neglects the larger motivations and the appeal of a religious movement. Second, to simply render the world as members (of the Peoples Temple or the Klan) may see it yields a one-sided presentation, which reflects Blee’s poignant concern. Understanding a movement from the perspective of members should not ignore how others, from the outside, engage the language, the symbology, and the believers of those movements. Blee’s and Chidester’s methods inform my attempt to find a more integrative approach to the Klan: to see with them and, more important, to recognize that this is only a partial presentation of the story.

Moreover, I am convinced by Michael Barkun’s approach to movements generally labeled as fringe. Barkun insists that no matter how odd or repellant religious systems might appear, white supremacists still believe them to be true when they furnish a framework for supremacy’s ends.80 If supremacy movements maintained the legitimacy of their worldviews, then scholars must take seriously their claims no matter how extreme. The religion of the Klan should be seen as religion. The religious systems of the hate movement, believable or not, influenced their members and often supplied divine mandate for their racism, hate, and the purpose of the community. To recognize how those religious systems placed race, nationalism, and gender in the realm of the ultimate is not only necessary to comprehending how those groups function but also to how best to counteract similar movements. To study the Klan as a Protestant movement adds complexity to standard histories of the Klan and further explanation of how the order imagined the larger world.

In a strict historical work on the Klan, it might be easy to dismiss concerns of empathy, redemption, and my role as interpreter. I could easily just focus on the facts of the movement’s rise and decline and the roles that Protestantism played in that history. However, because of my desire to step inside the worldview of the Klan, I have to engage more directly the ethics of allowing Klan voices to speak for themselves. By applying ethnographic methods to historical evidence, I attempt to re-create the religious lives of dead Klansmen and Klans women. What I do cannot neatly fall under the parameters of lived religion because I am re-creating the worlds of people who are gone. I have fragments of their lives cobbled together in print, and I use ethnographic methods to bind these fragments together into a cohesive whole. My work also engages the larger question of what happens when ethnography and history intermingle. Can we re-create the lives of dead religious actors? Are we truly presenting them as they see themselves, how they hoped to see themselves, or some mishmashed presentation of both? I am primarily interested in the complications that arise when we try to bind present and past tense, especially when the religious actors we study are at the very least unsavory.81 By engaging and taking seriously the religious voices and actions of the dead, we are transformed by our work and our work can be transformative. Ethnographic methods both complement and complicate religious histories, but in my work it remains clear that this merger allows new stories to be narrated to provide richer, nuanced tellings of American religious history. This means that my study is neither a complete portrait of 1920s America nor a strict history of Klan actions. Instead, I present the worldview of the Klan by illuminating how the order characterizes faith and nation, as well as what members hoped, feared, and admired about American culture. To see through the eyes of members and leaders clarifies their understandings of religion, nation, race, and gender. My project is arranged thematically rather than historically, which means that each chapter centers on one component of the Klan’s worldview to delve deeply into how the order represented itself and its vision of white Protestant America.

Chapter 1 revolves around the Klan’s professed Protestantism. In an exploration of Klan robes, Jesus, and the retellings of Protestant history, the Klan’s commitment to the faith appeared in terms of exclusion. The order employed a generalized Protestantism while simultaneously limiting the historical boundaries of the tradition. Building upon those presentations of Protestantism, chapter 2 explores the relationship between religion and nation in Klan print culture. For the order, white Protestants created America, and the burden of national maintenance fell solely upon their shoulders. Using material artifacts, like the fiery cross and the American flag, as well as the selective, historical accounts of amateur Klan historians, the order argued that the origins of the nation were explicitly religious. The battle for continued inclusion of the Bible in public schools became a religious brawl to safeguard the nation by guaranteeing that future citizens would have access to the sacred texts throughout their schooling.

Chapters 3 and 4 assess the place of gender, masculinity, and femininity in the movement. To be a citizen and a Protestant was to be masculine, which was the bedrock of being a successful Klansman. The order circumscribed the role of Christian Knighthood for members in addition to instituting the rhetoric of “real” manhood. Martyrdom emerged as the penultimate example of masculinity because the self-sacrificing act depicted strength, overwhelming allegiance to the order, and an emulation of the manly Christ. Whereas masculinity was crucial to the identity of the Knights, femininity proved to be a more ambiguous affair. Knights proclaimed the protection of white womanhood as slogan for the order, but women often contradicted the men’s vision of the female roles and conditions. Klansmen represented women as defenseless, vulnerable, and endangered, usually by Catholics, but the Women of the KKK (WKKK) had different ideas about the nature of their womanhood. The WKKK asserted its members’ rights as equal citizens in the Invisible Empire, whose dedication to nation and the perpetuation of the faith rivaled that of the men’s order.

Chapter 5 delves into the Klan’s presentation of whiteness and race by examining the order’s reflections about African Americans and Jews. Through the account of “other” races, the traits of whiteness become more visible. In addition, the Klan traced the heritage of America to its Nordic and Anglo-Saxon roots to claim that the white race bore the responsibility for the development of the nation and Protestantism. However, the order’s vision of racial alchemy, which created the American race, strained its commitment to racial purity.

Finally, the sixth chapter narrates the Klan–Notre Dame Riot of 1924 to show the order’s devotion to nation, race, and religion as expressed in anti-Catholicism and its firm belief that Klan members were the victims of persecution in the riot and on the national stage. In South Bend, Indiana, the Klan sought to defend the nation and its true citizenry while also realizing how tenuous its own vision was. The order imagined a white Protestant America in print, artifacts, rallies, and speeches. The KKK stood at the crux of peril and promise for the beloved nation, and its worldview contained lament as often as hope. Warring factions, personified in the riot, attacked the nation from within her boundaries. The Klan was both soul and savior, the center as well as the defender, of its imagining of nation, but members also had to confront the fragile nature of the order’s vision. To sustain beliefs and ideals, members turned to reading, robes, and fiery crosses. Those print artifacts tell the story of the 1920s Klan and its fervid persistence in maintaining white Protestant dominance.