Only animals raised humanely and non-intensively on natural feeds yield well-flavoured meat. What happens to them afterwards – slaughtering, butchering, hanging – also contributes greatly to quality. This means that it takes times and money to produce good meat, and that it is expensive to buy. But attempts at cooking poor meat soon convince that quality and flavour are worth paying for, even if it means eating less meat and less often. Buy the right cut for the way you intend to cook it; a well-prepared stew will always taste better than a lesser cut grilled or roasted.

Choosing

‘A skilful, experienced butcher treats his meat almost as a tailor does his cloth. If it is stretched out of shape, if there are seams in the wrong places, if he has to make up a respectable looking joint by adding a piece here, skewering in some fat there, he knows that as soon as the meat is exposed to violent heat it will contract: unnaturally stretched muscles will spring back into place; it will cook unevenly; it will end up looking like a parcel damaged in the Christmas mails. No wonder people say that the cheaper cuts are a false economy. But if that same piece of meat had been stripped of membrane, sinew and gristle before it was rolled and tied, it would be a compact little joint which would keep its shape during cooking and which could be quite successfully roasted.’ Elizabeth David in House and Garden, February 1958.

A good butcher will always give you better service, and almost always better meat, than you can get in a supermarket. Unhappily, their numbers are dwindling. A butcher should not only be able to prepare the cut you want, but also tell you where the meat came from, probably the breed, how it was reared and for how long it was hung. When checking out a butcher, see if the meat on display is well cut and that the shop smells fresh. Shops with slabs full of plastic bags of meat that is hard to identify are best avoided. Large joints like a loin of pork or a rib roast of beef are difficult to find in a supermarket, but a good butcher will be able to supply them, and bone out the pork or chine the beef as a matter of course. For cheap cuts like shin of beef or belly of pork, not to mention tripe, seldom stocked in supermarkets, you will also need a butcher.

Supermarkets certainly offer more choice than they did a few years ago, and have extended their range to include cuts that were not common in Britain until recently. In the last few years they have also responded to demand by stocking organic meat, yet there is still some ambiguous labelling such as ‘farm-assured’ or ‘traditional’ – how are we to know what these mean? Similarly, they woo the consumer who is concerned about fat in the diet with clearly labelled leaner meats, but the leaner meat is frequently obtained by intensive breeding and feeding programmes – a point which is not mentioned.

Scares related to agriculture, especially the rearing of animals, and the quality of food occur with alarming regularity, BSE being the most serious. Consumers have moved in large numbers to buying humanely reared or organic meat. Farmers who persisted in or have returned to the methods of the pre-intensive farming days, producing top-quality meat from animals raised by methods which promote their welfare, are selling all they can produce, as are organic farmers. They raise their animals non-intensively, feed them a natural diet and only use minimal antibiotics when it is essential. Herds tend to be small, and animals are not stressed or forced beyond their natural growth limits. The ‘organic’ label ensures these and other criteria of sustainable farming have been met; labels such as those of The Real Meat Company or Freedom Foods have similar strict standards of husbandry.

Good-quality meat has always been expensive: the cheapest way to buy is from the farm shop, or by mail but then it can be difficult to buy small quantities. A small amount of good meat is always better than a large slab of something indifferent. As a nation, it seems we are consuming less meat, particularly red meat. The roast meat and two veg stereotype of an English meal is being challenged as we turn to small, trimmed French or Italian cuts, or use a little meat with plenty of vegetables in the Asian manner. There is also more awareness that fish, pulses and grains are all excellent sources of protein.

Appearance

Unfortunately the appearance of a piece of meat does not necessarily give an indication of quality, nor whether it comes from a naturally or intensively raised animal, but here are some basic guidelines.

The surface should look moist but not sticky or slimy. The fat should be firm, white on lamb and pork, cream-coloured on beef. Marbling of fat through the muscle is a good sign; the meat should be tender and have a good flavour. Avoid bright red beef because it will not have been hung for long; beef should have a deep rich colour, with a tawny tinge if very mature. Veal from naturally reared calves, fed (after weaning) on grass and hay, is pink; it cannot be mistaken for the pallid white meat that comes from calves reared in crates and fed on a milk diet. Very young lamb has rosy-pink flesh; later in the season it is darker, tending to purple, but still pink, not red. Pork is sold as young meat and should have glistening pink flesh (beige-pink rather than rosy pink) and white fat. The muscle looks softer and smoother than that of other animals.

Basic mince is best avoided; it is usually made from the poorest cuts that have a high proportion of fat and connective tissue. It tends to look grey. Better-quality minced beef is dark red and has less obvious blobs of fat. Other minced meats are sometimes available. In the supermarket read the label to see what percentage fat they contain. Sinew and connective tissue are never mentioned. The best way to get good mince is to select a piece of meat and ask the butcher to mince it.

Offal spoils quickly. Liver and kidneys should look moist and have a glossy sheen; sweetbreads should be pale in colour. Avoid any offal that looks sweaty or slimy or has a strong smell.

Dry-cured bacon is the best for flavour and value. It doesn’t shrink in the pan and ooze white goo as the wet-cured injected bacon does. Some bacon is smoked after salting; this enhances the flavour but also hardens the bacon a little.

Ham and gammon should be firm with not too much fat and not too dry. However, if the flesh is very moist it is likely that it was injected with water.

Ageing meat

All meat needs to be aged to allow enzymes to break down the tissue and tenderize it and to allow the flavour to develop. One of the difficulties today is that most meat is not hung for long enough. A good butcher who hangs meat will tell you how long it has hung and may be willing to hang it longer if you wish.

Storing

Meat from the butcher should be taken out of its packaging, loosely wrapped in plastic and put on a plate in the coldest part of the refrigerator. Meat in airtight plastic packs can be kept as is. Large joints will keep for 4–5 days, chops and cubed meat for up to 3 days, mince and offal are best eaten within a day. Lamb and beef will keep longer than veal or pork.

Quantities

Quantities needed vary according to how the meat is to be cooked and what other ingredients will be used in the dish. As a guideline, allow 120–150g trimmed, fairly lean meat off the bone or 250–300g on the bone per person.

Preparation

See notes under individual animals.

Cooking methods

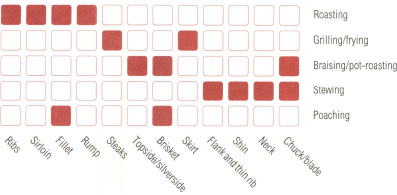

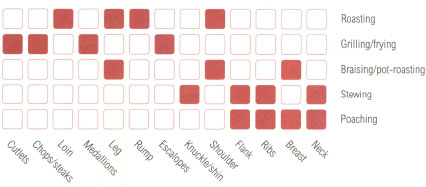

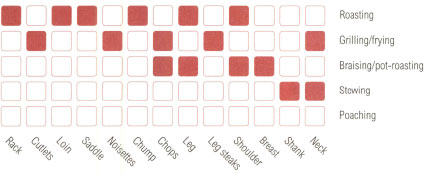

Tender cuts of meat can be roasted, baked, grilled or fried, whereas tougher cuts should be pot-roasted, braised or stewed. Poaching is as successful with a prime fillet of beef as with shin. The tender cuts come from the parts of the animal that do least work whilst it is on the hoof – the centre back of the animal; tougher cuts come from the shoulders and legs.

Cooking times for tender cuts are relatively short, and vary according to how well done you want the meat to be; but beware, tender cuts become tough if overcooked. Guidelines for roasting and grilling times are given on pp. 310–12 and 314; don’t follow them slavishly, use your nose and eyes too. If there is an appetising smell of roast meat and if the juices are seeping to the surface of the meat, it is almost ready.

All the tougher cuts need long slow cooking to break down tissue. You can’t really overcook a braised or stewed dish, although you can let it dry out if you don’t check the amount of liquid and adjust the cooking temperature if necessary. Slow-cooked dishes can always be reheated. The recipes for slow-cooking different meats and poultry are often interchangeable: for example, you can make an excellent beef stew following the recipe for coq au vin (p. 288), a lamb stew with artichokes instead of veal (p. 328) or pork instead of beef in the carbonnade (p. 323).

Cook the meat you buy by an appropriate method. Do not be tempted to buy an inexpensive cut and then roast rather than braise it. Remember too that expensive cuts often have less waste than cheaper ones.

Roasting

Roasting is most suited to large joints of meat; cuts weighing less than 1.5kg are better braised or pot-roasted. Meat for roasting should be at room temperature before cooking starts. Include any stuffing in the total weight when calculating cooking time. The shape and thickness of a joint also affect cooking time: a compact shape requires longer than an elongated joint of the same weight; a joint on the bone will take longer than the same cut boned. The bigger the roast, the shorter the cooking time per unit of weight and, after searing, the lower the temperature. A boned roast may be placed on its bones to prevent it stewing in the juices in the bottom of the pan; alternatively, use a rack. A layer of fat around a joint bastes it whilst it cooks, keeping the flesh moist, but for lamb I prefer to remove most of the fat and rub it with olive oil. Most lean cuts (veal, pork fillet, venison) should be barded with a sheet of fat (p. 326) but fillet of beef needs only to be rubbed with butter. Roasts need regular basting with the fat that falls into the pan; or, towards the end of cooking, stock, wine or a reserved marinade may be used instead.

Always rest a roast before serving: if it is carved immediately, the juices will all pour out and the texture will be on the rubbery side. Cover the meat loosely with foil and keep in a warm place – the turned-off oven, with the door open, or on the back of the cooker. After 15–20 minutes, depending on size, the juices will be reabsorbed into the flesh and the meat tender. Serve the meat on hot plates as soon as it is carved.

Your oven and your own experience ultimately determine how you use the timings in the charts below. The timings are intended as guidelines to be used in conjunction with the notes on roasting.

Beef

Beef is best roasted rare or medium to produce a supple texture and bring out maximum flavour; well-cooked roast beef can be dry and is rather a waste of top quality meat.

On the bone

Cuts to choose: rib roast, sirloin on the bone

|

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

rare |

15 min per 500g |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 reduce to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4 |

first 15 min rest of time + 15–20 min rest |

|

medium |

20 min per 500g |

as above |

as above |

|

well done |

25 min per 500g |

as above |

as above |

Off the bone

Cuts to choose: rolled sirloin, rump and topside

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

rare |

10–12 min per 500g |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 reduce to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4 |

first 15 min rest of time + 15–20 min rest |

|

medium |

15–18 min per 500g |

as above |

as above |

|

well done |

20–22 min per 500g |

as above |

as above |

Fillet of beef

A long thin piece like a fillet will cook more quickly than the same weight of a rolled roast, so follow the times and oven temperatures below.

|

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

rare |

7 min per 500g |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 |

total cooking time + 10 min rest |

|

medium |

10 min per 500g |

as above |

total cooking time + 10 min rest |

Veal

Veal dries out if it is roasted at too high a temperature so it is always cooked in a medium oven and for a longer time per 500g. Like pork, it is always eaten well done.

On or off the bone

Cuts to choose: loin, rump, shoulder, topside

|

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

well done |

25–30 min per 500g |

190°C, 375°F, gas 5 |

total cooking time + 15–20 min rest |

Lamb

Lamb cooked pink tends to keep its flavour better than well-cooked meat. A thin joint like a rack, or a double rack as a guard of honour, will roast more quickly than a large joint, and so adjusted times are given below.

On or off the bone

Cuts to choose: leg, saddle, breast, shoulder, crown roast

|

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

rare |

10–12 min per 500g |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 reduce to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4 |

first 15 min rest of time + 15–20 min rest |

|

medium |

15 min per 500g |

as above |

as above |

|

well done |

20 min per 500g |

as above | as above |

Rack of lamb, guard of honour

|

Doneness |

Time |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

rare |

15 min |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 |

15–20 min |

|

medium |

20 min |

as above |

as above |

Pork, like veal, is always well done. It is started at a high temperature to release the fat, then at a lower temperature to cook through.

On or off the bone

Cuts to choose: leg (knuckle or fillet), loin, shoulder, ribs

| Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

well done |

25–30 min per 500g |

220°C, 425°F, gas 7 reduce to 180C, 350°F, gas 4 |

first 15 min rest of time + 15–20 min rest |

Venison

Venison is usually eaten pink or rare, occasionally medium cooked, but it becomes very dry if roasted for too long.

Cuts to choose: haunch, saddle

|

Doneness |

Time per weight |

Oven temperature |

Cooking time |

|

rare |

15 min per 500g |

220°C, 425°F, gas 7 reduce to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4 |

first 15 minutes rest of time + 15–20 min rest |

|

medium |

25 min per 500g |

170°C, 325°F, gas 3 |

total cooking time + 15–20 min rest |

Hare

The saddle is the prime cut from a hare, and it is always cooked rare.

|

Doneness |

Time | Oven temperature | Resting time |

rare |

15 min |

230°C, 450°F, gas 8 |

5 min |

Testing for doneness A meat thermometer will give a reading of the internal temperature of the joint. Before putting the joint into the oven, push the thermometer into the thickest part of the meat, avoiding contact with bone. For rare beef, lamb or venison, the temperature should reach 60°C, 140°F; for medium beef or lamb 70°C, 160°F; and for all well-done meat 75°C, 170°F. However, since meat goes on cooking whilst it is resting, take the roast out of the oven when the temperature is a degree or two lower than those given above.

Another reliable method is to push a flat metal skewer into the thickest part of the meat, leave it for 30 seconds, then pull it out and test it against your wrist. If the skewer is cold the meat is not yet ready, if warm the meat is rare, if quite hot the meat is medium and if it is very hot the meat is well done.

Simple gravy Whilst the roast is resting, pour or skim off the fat from the pan and deglaze* with a little stock, water or white wine, scraping up any meat bits stuck to the bottom. Reduce a little and pour into a warmed jug to serve with the meat.

Carving It is easier to carve on a board than on a platter. Use a carving fork to hold the roast steady and, with a well-sharpened carving knife, slice through the meat across the grain.

Transfer the meat to a warm platter or individual plates; do not keep it waiting at this stage.

To carve a rib roast of beef The butcher will normally cut through the chine bone where it joins the ribs, so that when the meat is ready to be carved it can be removed. Now insert the knife horizontally between the bones and the meat to detach it, and slice down onto the ribs.

To carve a leg of lamb or pork A leg is more easily carved if the pelvic bone is removed before it is roasted (see p. 330). With the plumpest side uppermost, hold the leg steady with a carving fork near the shank and cut slices. Turn the carved side down and slice the other side, then cut small slices from the shank.

If a leg of pork has scored crackling, lift off the crackling ‘shell’, and cut out a wedge of meat near the end of the bone. Slip the knife in horizontally along the bone and release the meat from it. Now cut down in slices to the bone. Slice the crackling and serve with the meat.

To carve a shoulder of lamb or pork Do this in the same way as a leg, but since the bone is more awkward to carve around, the slices will be smaller.

Grilling and barbecuing

These are two excellent ways of cooking small tender cuts. Steaks, chops, cutlets, kebabs as well as sausages and burgers of beef, lamb or venison all respond well to searing followed by less fierce cooking. Meat should be at room temperature before grilling or barbecuing, and marinating is beneficial (see individual recipes and pp. 386).

Remove excess fat, leaving a narrow border only, and brush the meat with olive or sunflower oil before cooking. Do not salt, because salt draws out the juices and prevents proper sealing. Do not pierce the meat whilst it is cooking. Turn it once during cooking with a spatula or tongs.

Red meats should be seared quickly with high heat and then cooked more slowly so that the heat can diffuse inside the meat. Cooking time varies according to taste – see the table below.

White meats should be seared, but with medium heat, and then cooked gently until cooked through. Veal and pork should not be served underdone, but take care not to overcook and dry out the meat.

Beef

A rare steak contracts slightly when touched, a medium steak is resistant when touched and juices seep on the sealed surface, a well done steak feels firm. Steak benefits from resting for a few minutes before being cut.

Veal

• chops, cutlets 6–8 min per side depending on thickness, turn once, baste regularly

Lamb

• chops, cutlets 3–7 min per side depending on thickness and how well you want them cooked

Pork

• chops 12–18 min per side depending on thickness • spare ribs It is advisable to marinate these first. A whole rack takes 30–40 min to grill; it should be basted frequently and turned infrequently

Venison

• cutlets 3–4 min per side, turn once

Frying and stir-frying

The small cuts suitable for grilling and barbecuing can also be fried. Bring the meat to room temperature for an hour before cooking. For red meats have the pan very hot, add a little oil or oil and butter, and quickly sear the meat before reducing the heat. Cooking times are as above. Pork and veal should be sealed at a moderate temperature and then cooked until well done; for chops, follow the time guidelines above. Veal escalopes fried gently in butter and oil will be ready after cooking for 3–4 minutes on each side.

Good-quality steak or loin of pork, thinly sliced, is the best choice for stir-frying for oriental dishes.

Sautéing

A sauté is quickly made with small pieces of tender meat, sometimes dusted first in flour and fried. Vegetables and herbs are added after the meat has browned, and the pan is deglazed* with water, white wine or stock so that the meaty bits stuck to the bottom can be scraped loose. A spoonful or two of cream may be stirred in before serving.

Pot-roasting and braising

Slow cooking with a little liquid and flavourings is ideal for lean but less tender cuts such as topside, silverside or brisket of beef, chuck or blade steak. Veal is particularly suited to this treatment: all the leg cuts, the sliced shank (usually called osso buco), stuffed breast and joints from the shoulder. Braised lamb shanks make a rich satisfying dish and shoulder pot-roasts well. Pork fillet pot-roasts beautifully as do large less tender cuts such as rolled shoulder and the upper neck end. Ham and gammon will also braise well. Venison, like veal, is a dry meat which benefits from moist cooking; a boned shoulder or even a haunch are both suited to pot-roasting. Hare and rabbit joints also benefit from slow cooking.

Stewing

The extremities – neck, shin – make excellent stews and casseroles, as will cubed chuck or blade steak, veal flank or ribs, shoulder of lamb and shoulder of pork or hand and spring. Trotters and hock enrich stews as the gelatinous tissues break down.

Poaching

If meat is not to become tough, it must be poached in barely simmering water, never coming near the boil. One of the grandest poached dishes is a fillet of beef. Brisket, particularly if brined, poaches well. Otherwise the cuts which are suited to stewing are also good for poaching. Stuffed breast of veal makes a handsome dish. Fresh, salted and cured pork all respond well to poaching. A bonus of poaching is the stock created during the cooking.

Leftovers

Roast or braised beef, veal and pork are delicious cold; beef turns up as a salad all over the world, in a mustardy vinaigrette with gherkins and capers, with a dressing of orange juice, onion and herbs, with lemon grass*, fish sauce and a mild vinegar. Lamb is often considered to be too fatty to enjoy cold. The salad repertoire can be extended by following the Thais and Vietnamese and using small amounts of cooked meat in herb and vegetable salads (pp. 88–9).

There are many cooked dishes to be made with leftover meat, and there is one important principle to understand before making any of them. If the meat has been cooked by dry heat - roasting or grilling - it can be heated very gently for 5–10 minutes in a liquid and will remain tender. Longer cooking and higher temperatures will initially toughen it, and then it passes the tough stage and becomes tender again. If you decide to opt for longer cooking, slices of meat will need 1–1½ hours further cooking; diced or finely chopped pieces 30 minutes. Pot-roasted or braised meat is already past the tough stage and can be reheated for a shorter time.

The classic French ways to use leftover beef are to heat slices in white wine and add a mushroom or tomato sauce, to cook it further in a rich onion sauce, or to make a hash with potatoes, tomatoes and onions. In Alsace, they make a well-flavoured rather dense plate pie, or tourte, with finely chopped cooked pork. Many Middle Eastern dishes are based on vegetables to which a small amount of meat is added, usually minced or finely diced lamb. Leftover meat can be used in the same way, cut up small in fillings for vegetables, to stuff vine or cabbage leaves, in pilafs (p. 181) and grain-based casseroles (p. 204). Moussaka (p. 108) and shepherd’s pie (chopped cooked lamb with cooked onions and carrots and a little stock or gravy, topped with mashed potato and baked for about 40 minutes at 180°C, 350°F, gas 4) are both dishes that are almost invariably made with cooked meat. If you use beef for the pie, it becomes cottage pie.

Beef

Cuts to choose

Ribs. Forerib and back rib are prime cuts for rib roasts; the lean meat is marbled with fat and has an outer layer of fat which will baste the meat as it roasts. Best roasted on the bone for greater flavour, but a rib roast can also be boned and rolled. Rib steaks are sold as entrecôtes.

Sirloin. Extends from the ends of the ribs to the rump, providing tender, lightly marbled top-quality meat for roasting on or off the bone, or for cutting into steaks – T-bone, porterhouse and sirloin.

Fillet. Fillet lies below the backbone and offers the tenderest cut of beef. Sometimes sold as part of the sirloin, it is more generally removed and sold as a whole boneless piece for roasting or poaching, or cut into steaks – filets mignons, tournedos, châteaubriand and fillet steaks.

Rump. This has an outer layer of fat and is lightly marbled; sold as rump steaks or as joints for roasting.

Topside and silverside. These are lean joints from the upper leg, often sold with a separate piece of fat tied around. Best for pot-roasting or braising, although topside can be roasted. Salted silverside makes corned beef.

Brisket. The front of the breast, usually rolled and tied. A fatty meat which benefits from braising, pot-roasting or poaching. Brisket is also available salted.

Skirt. A small lean muscle within the flank. If marinated, it can be grilled as a (cheaper) steak and has a fine flavour.

Flank and thin rib. Fibrous meat running down from the loin. After trimming, it can be used for stewing or may be minced.

Shin. Sinewy but well flavoured; the connective tissue gives a rich gelatinous quality to slow-cooked stews. It is also good for making stock.

Neck. Inexpensive cuts with a high proportion of fat and connective tissue; usually sold cubed for slow cooking or as mince.

Chuck and blade. From the shoulder. Fairly lean joints or steaks are marbled and have a layer of outer fat. Best for braising or cubed for stewing.

Preparing a fillet of beef

Cut away the chain muscle from the side of the fillet; it is a tough sinewy piece but can be used for stewing or mincing. Lift and cut away any silvery-white membrane (it shrinks during cooking), leaving the meat free of all fat and sinew. Fold under and tie the tapered end if the fillet is to be roasted.

Preparing a steak

Trim excess fat, leaving an even layer. Snip through the fat into the edge of the meat intervals so that the thin membrane lying between the fat and the meat does not curl as it cooks.

Roast fillet of beef

This may be horrendously expensive, but it is a prime cut with no waste. Treat it carefully and don’t overcook it.

For 8

1 fillet of beef weighing 1.75–2kg

3 tbs olive oil

freshly ground pepper

watercress

béarnaise sauce (p. 374)

Remove the beef from the refrigerator an hour before it is to be cooked. Prepare it, if necessary, as described above. Tie it around with string in 4 or 5 places to keep it in shape, tucking under the tapering end. Heat the oven to 230°C, 450°F, gas 8. Brush the meat all over with 2 tbs olive oil and season it with pepper. Do not add salt. Use the remaining oil to grease the bottom of the roasting pan.

Roast the fillet 25–30 minutes for rare meat, 35–40 minutes for medium. Take it from the oven, wrap in foil and keep warm for 10 minutes. Garnish with watercress and serve with its own juices and béarnaise sauce. Serve quickly on hot plates.

New potatoes and a pea purée or wilted spinach make simple, clean tasting accompaniments.

Roast sirloin with mushroom sauce

For 6

1.5kg rolled sirloin

3 tbs olive oil

For the sauce

60g butter

1 onion, peeled and sliced finely

2 carrots, peeled and diced

3 tomatoes, skinned and chopped

bouquet garni* of bay leaf and thyme sprigs

600ml meat stock (p. 5)

salt and freshly ground pepper

1 rounded tbs flour or rice flour

2 tbs water

250g button mushrooms

4 tbs madeira

Bring the beef to room temperature for an hour before cooking. To make the sauce, melt half the butter in a heavy pan, add the onion and let it colour lightly. Add the carrots, cook gently for 10 minutes, then stir in the tomatoes and herbs. Increase the heat slightly so that the liquid from the tomatoes evaporates and the mixture thickens. Pour in the stock, season and simmer gently for 20 minutes.

Remove the pan from the heat. Mix together the flour and water and stir it, a little at a time, into the sauce. Return the pan to low heat and cook, stirring continuously, until the sauce thickens. Strain the sauce through a fine sieve, do not press too heavily on the vegetables. Return it to the rinsed-out pan and reheat gently. It should have the consistency of a thin cream soup.

Wipe the mushrooms and leave whole, unless they are larger than button mushrooms in which case cut them in four. Add them to the sauce and simmer for 10 minutes. Check the seasoning.

Up to this point the sauce can be made ahead of time and be kept warm or reheated.

To cook the beef, heat the oven to 230°C, 450°F, gas 8. Coat the meat with the oil (leaving a little to grease the bottom of the roasting tin) and season it with pepper. After searing the meat for 15 minutes, reduce the temperature to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4. Roast for 10–12 minutes per 500g for rare meat, 15–18 minutes for medium and 20-22 minutes for well-done meat. (To use a meat thermometer, see p. 312.) Wrap the joint in foil and keep in a warm place for at least 15 minutes before carving.

While the beef is resting, finish the sauce. Add the madeira and whisk in the remaining butter cut into small pieces. Carve the beef, spoon over a little of the sauce and serve the rest separately. Have hot plates ready.

Steak au poivre

This is one of those dishes by which you can judge the standard of cooking in a restaurant – well worth trying at home, and giving great satisfaction when you get it just right.

For 4

2 tbs black or green

peppercorns

2 tbs sunflower oil

4 fillet or sirloin steaks

Crush the peppercorns coarsely. Rub the steaks on both sides with a little of the oil and press peppercorns into both sides with the palm of your hand. Heat a heavy frying pan or ribbed griddle pan, coat it with the remaining oil and when it is very hot, sear the steaks for about 1 minute on each side. Wait for a crust to form before turning them. Reduce the heat and continue to cook for about 3 minutes on each side for rare fillet steaks or 4 minutes for medium rare. Sirloin steaks will take a minute or two longer on each side. Adjust times according to the thickness of the steaks. Serve at once.

Steak with mushroom sauce

Use 4 fillet or sirloin steaks and follow the recipe for Venison steaks with mushroom sauce on p. 351, omitting the juniper.

Beef teriyaki

This is a Japanese way of frying or grilling steaks. Teriyaki is a sauce based on saké (rice wine) and mirin (a syrupy rice wine used only in cooking) and soy sauce. It is used to baste or glaze grilled or fried fish and meat in the last stages of cooking. You can buy bottles of teriyaki sauce, but it is quite easy to make and keeps well in the refrigerator if you want to make a larger quantity. Saké and mirin can be bought from oriental shops and some supermarkets.

For 4

4 tbs saké

4 tbs mirin*

4 tbs dark soy sauce

2 tsp sugar

1 tbs sunflower oil

4 sirloin or rump steaks

First prepare the sauce: combine the saké, mirin, soy sauce and sugar in a small pan, bring to the boil and simmer until the sugar has dissolved.

Put a heavy frying pan over high heat and add the oil. When it is very hot, fry the steaks on each side for 3 minutes, turning once. Now spoon the teriyaki sauce over the steaks. It will sizzle fiercely and reduce. Coat the steaks with the glaze on both sides, turning them once, and serve.

If you prefer your steak medium rather than rare, fry each side for a minute or two longer.

To barbecue It is best to marinate the steaks in the sauce for up to 30 minutes, then transfer the meat to the grill and baste with the sauce as it cooks.

Sichuan stir-fried beef with leeks

This is a winter dish in Sichuan and it makes a good winter dish here, too, served with noodles or rice. You could use other vegetables – shredded Chinese cabbage or mustard greens, sliced celery or broccoli florets. The Sichuanese like chilli-hot food, but if you do not, reduce or leave out the chillies.

For 6

800g lean beef, rump or sirloin

90ml soy sauce

60ml rice or wine vinegar

1 garlic clove, peeled and chopped finely

4 slices ginger, peeled and chopped finely

2–3 chillies, seeded and sliced finely

4 spring onions, white and lower green part, sliced finely

2 tsp sugar

4 tbs sunflower oil

750g young leeks, sliced finely

Cut the beef across the grain into thin ribbons, discarding any fat. Combine the soy sauce, vinegar, garlic, ginger, chillies, spring onions and sugar and marinate the beef for 30 minutes. Heat a wok or heavy frying pan, add half the oil and when it is very hot stir-fry the leeks for 3 minutes. Remove them from the wok and add the remaining oil. Drain the beef, reserving the marinade. When the oil is very hot, add the beef. Toss and stir it rapidly for 1 minute. Return the leeks to the pan, mix well with the meat and pour over the marinade. Cook for a further minute and serve at once.

Tuscan braised beef

A satisfying and simple slow-cooked dish that can easily be extended for more people. In other parts of Italy, braised beef is cooked by the same method but the flavourings change: white wine is used instead of red; diced salt pork or bacon may be added with the vegetables; chopped anchovies and parsley may replace the cloves and nutmeg. Thyme, sage or rosemary also occur as alternative flavourings, but use sage and rosemary very sparingly.

For 6–8

2 tbs olive oil

30g butter

1.75kg topside or other braising cut

salt and freshly ground pepper

2 large onions, peeled and chopped finely

2 carrots, peeled and chopped finely

1 stalk celery, chopped finely

2 garlic cloves, peeled and chopped finely

a glass of red wine

2 cloves

nutmeg

2 tomatoes, peeled, seeded and chopped, or 3 tbs passata (p. 378 or bought)

80ml stock or water

Use a heavy pan with a well-fitting lid in which the meat fits snugly. Heat the oil and butter in the pan and put in the beef, well rubbed with salt and pepper, and brown it on all sides. Lift it out and sauté the onion, carrots, celery and garlic and continue cooking until they begin to take colour. Put the meat on top of the vegetables, pour over the wine and let it bubble for a minute or two, then add the cloves, a grating of nutmeg, the tomato and the stock. Cover tightly; if necessary put a piece of foil under the lid. Cook on a very low heat or, alternatively, in a low oven (150°C, 300°F, gas 2) for 3 hours. Turn the meat occasionally and baste with a spoonful of the liquid.

When it is ready, carve the beef into thick slices. Strain the sauce though a sieve, rubbing through as much of the vegetables as possible, and pour over the meat to serve. A dish of lentils makes a good accompaniment: if you prefer, add the vegetables from the sauce to the lentils, and serve the meat with a thinner gravy. Another possibility would be boiled potatoes.

In Tuscany it is usual to make the dish the day before it is eaten and leave it to mellow. Any fat can be lifted off before it is gently reheated.

Daube of beef

This is the classic beef stew of Provence. It can be made without marinating the meat, but a few hours in a marinade will give the daube more flavour. Like all stews, it benefits from reheating.

For 4

1 kg topside of beef

2 onions, peeled and sliced

2 carrots, peeled and sliced

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

2 bouquets garnis*

400ml red wine

2 tbs wine vinegar

2 tbs olive oil

100g salt pork or bacon, diced

strip of orange peel

3 cloves

salt and freshly ground pepper

Cut the beef into 8–10 pieces, put these in a bowl with the onion, carrot, garlic, one bouquet garni, the wine and vinegar and marinate for 4–5 hours, or longer. Turn the meat occasionally.

Heat the oven to 150°C, 300°F, gas 2. Drain the meat and vegetables, reserving the marinade liquor. Heat the oil in a heavy pan and sauté the salt pork, then brown the meat. Add the vegetables from the marinade, but discard the bouquet garni, and put in a new one. Put in the strip of orange peel and the cloves and season well with salt and pepper. Pour over the marinade. Slowly bring to the boil on the stove, and let the liquid reduce a little. Cover tightly, with a piece of foil under the lid if necessary, and transfer the pan to the oven for about 3 hours. Remove the bouquet garni before serving.

The dish is usually served with rice – traditionally the red rice from the Camargue – or a dish of macaroni moistened with some of the cooking juices.

Carbonnade of beef

This is a richly flavoured stew from the Flemish part of Belgium, made with a dark beer. It is best made in advance and reheated.

For 6

2 tbs beef dripping or oil

4 onions, peeled and sliced finely

30g plain flour

1 tsp mustard powder

1kg stewing steak, cut in large cubes

300ml dark Belgian beer or stout

100ml meat stock (p. 5) or water

2 tbs wine vinegar

1 bouquet garni*

salt and freshly ground pepper

a grating of nutmeg

1 tbs brown sugar

Heat the oven to 150°C, 300°F, gas 2. Fry the onion in half the dripping or oil, allowing it to colour, but don’t let it burn. Lift it out with a slotted spoon and put it into a shallow casserole. Combine the flour and mustard powder and coat the meat. Brown it quickly in the remaining dripping or oil and transfer to the casserole. Add the stout, stock and vinegar to the frying pan together with the seasonings and sugar and bring to a simmer. Pour over the meat and onions, cover tightly and cook for about 3 hours. Remove the bouquet garni before serving.

Serve with mash or lightly toasted slices of french bread to soak up the gravy.

Oxtail stew

An easy dish, perfect for cold winter days and quite inexpensive. It needs little preparation but several hours’ cooking, and it is better if it is made a day in advance. The fat can then be removed from the top before the stew is reheated.

For 4

2kg oxtail, in 5cm pieces

2 tbs flour

salt and freshly ground pepper

2 tbs sunflower oil

2 onions, peeled

2 carrots, peeled

2 stalks celery

2 tbs tomato purée

3 sprigs thyme

2 bay leaves

4 cloves

200ml red wine

800ml meat stock (p. 5) or water

1 glass port (optional)

3 tbs chopped parsley

Heat the oven to 150°C, 300°F, gas 2. Trim excess fat from the oxtail and toss the meat in seasoned flour. Heat the oil in a large pan and brown the oxtail in batches. Chop the vegetables coarsely, by hand or in a food processor, and put them into the pan with the tomato purée, herbs and cloves. Replace the meat. Add the wine and stock or water, season with salt and pepper and bring to the boil. Skim off the scum that rises to the surface, cover the pan and transfer to the oven. Cook for 3 hours.

At this point the stew can be removed from the oven and left to cool. The next day, remove the fat from the surface before returning the uncovered pan to the preheated oven (150°C, 300°F, gas 2). If you continue cooking on the same day, remove the lid at this stage. Simmer for a further 1–2 hours; the meat should be loose from the bone and the sauce reduced and thickened. A glass of port stirred in 30 minutes before the end of cooking adds depth to the sauce.

Skim any fat from the surface, scatter over the chopped parsley and serve with noodles or potatoes.

Veal

Cuts to choose

Best end of neck. Prime meat sold as cutlets. Because the meat is very tender it is best grilled or fried gently and basted.

Middle neck. Part of the shoulder; usually sold as cutlets or shoulder chops.

Loin. A choice cut of very lean meat with a thin layer of outer fat. Usually sold boned and rolled for roasting, or as cutlets. The fillet is frequently removed and sold sliced as medallions for frying.

Leg fillet end (or cushion) and rump. Good-quality cuts, sold as boned and rolled joints for roasting and pot-roasting. The meat is very lean and benefits from larding. Escalopes are cut from the fillet end of the leg.

Knuckle and shin. Cuts with marrow bones that make well-flavoured gelatinous stews such as ossi buchi. Also very good for making stock.

Shoulder. Usually sold boned and may be braised or roasted. Another good joint for stuffing. Also available cubed.

Flank. A thin cut with lots of connective tissue from the abdominal wall. It needs long moist cooking – stewing or poaching – to make it tender. Also sold as mince.

Ribs. Sold boned, ribs are for stewing or poaching, since the connective tissue needs to be broken down.

Breast. Once boned, this is an excellent cut for stuffing, rolling up and poaching or braising. Also sold cubed.

Neck. Sold cubed for stewing or poaching.

Larding and barding

Very lean meats benefit from having fat added before roasting or pot-roasting, otherwise they become too dry. Larding is done internally, strips of pork fat in a larding needle are pulled through the meat. If you don’t have a needle, make holes in the meat with a skewer and insert small pieces of fat: it is not as effective, but better than nothing. To bard a joint, wrap wider strips of fat around the meat and tie securely. If you can’t get pork back fat, a lightly cured streaky bacon could be used.

Stuffing a breast of veal or lamb

Having got the butcher to bone the breast, lay it out flat, skin side down, spread it with the prepared stuffing and roll up, tucking one edge under the other. Tie into a neat shape, starting from the thick end.

Preparing veal escalopes

Escalopes do not need enthusiastic pounding, unless they are of very uneven thickness (which indicates poor butchering) or unless you want to stretch the meat to roll it around a filling. Cut away any connective tissue that will make the meat curl during cooking. Lay the escalopes between two sheets of plastic film or greaseproof paper and gently flatten them with the heel of your hand or a rolling pin. Escalopes are usually about 1cm thick when bought and are best flattened to half that thickness.

Veal escalopes with asparagus and balsamic vinegar

For 4

400g veal escalopes

300g green asparagus

2 tbs olive oil

40g butter

150ml white wine

salt and freshly ground pepper

4 tsp balsamic vinegar

Flatten the escalopes gently (see above). Break the asparagus to give pieces 8–10cm long and use the rest of the stalks for soup. Thread the spears carefully onto thin wooden skewers. Heat the grill or a ribbed griddle plate.

Put 1 tbs oil and 30g butter into a frying pan and set the pan over medium heat. When the fat is hot, fry the escalopes in batches. Do not crowd the pan. Fry the escalopes for about 3 minutes on each side, turning once. They should only be lightly browned. When they are ready remove them to a plate and keep warm.

Meanwhile brush the asparagus spears with the remaining oil and put them under the grill or on the griddle plate. Grill for 5–6 minutes, depending on thickness, turning them once.

When all the escalopes are cooked, add the wine to the pan and scrape up any bits stuck to the bottom. Let the wine bubble until it is reduced to only a couple of tablespoons, then add the remaining butter and any juices from the escalopes. Season the meat with salt and pepper and return to the pan. Turn the pieces a few times in the pan juices, then add 3 tsp balsamic vinegar and turn the meat once more. Transfer the escalopes and any juices to a serving dish, remove the asparagus from the skewers and lay across the meat. Drizzle the last tsp of balsamic vinegar over the asparagus and serve at once.

Veal escalopes with onion and cider sauce

For 2

200g veal escalopes

60g butter

2 medium onions, peeled and sliced finely

200ml dry cider

salt and freshly ground pepper

80ml crème fraîche or double cream

Flatten the escalopes lightly (see above). Heat half the butter in a frying pan and sauté the onions for 5 minutes. Pour over the cider, bring to the boil and reduce to 4 tbs. While the cider is reducing, heat the remaining butter in another pan and cook the escalopes for 3–4 minutes on each side. Remove them to a warm dish, season and keep warm. Scrape any bits from the bottom of the pan and add them to the onions. Stir the cream into the onions and season. Add the escalopes to the onions and reheat briefly in the sauce.

Veal with garlic (Aïllade de veau)

An easy supper dish, from an old provençal recipe.

For 2

1 tbs sunflower oil

2 veal chops or steaks

4 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

3 large tomatoes, peeled, seeded and chopped

1 tbs dried breadcrumbs

salt and pepper

a glass of white wine

Heat a heavy frying pan, coat it with the oil and brown the meat on both sides. Take out the chops and keep to one side. Put all the other ingredients into the pan and simmer to make a sauce. After 20 minutes, put back the chops and continue to cook over low heat for a further 45 minutes. The sauce should be thickish; cover the pan if it is reducing too much, or add a little more wine or water.

Veal stew with artichoke bottoms

The veal should be marinated for some hours, even overnight, but the cooking time is quicker than for many stews. I have used frozen artichoke bottoms; to prepare fresh ones, see p. 101.

For 4

800g pie or stewing veal, cubed

300ml white wine

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

3–4 sprigs of thyme

4 tbs olive oil

salt and freshly ground pepper

2 large onions, peeled and sliced

6 sun-dried tomatoes, sliced

2 tbs flour

2 bay leaves

400g frozen artichoke bottoms

Put the meat in a bowl, add the wine, garlic and thyme, stir, cover and leave for 3–4 hours. When you are ready to cook, lift out the veal and dry with kitchen paper. Strain and reserve the marinade. Heat half the oil in a heavy pan and seal the veal in batches. Transfer the meat to a casserole and season with salt and pepper. Add the remaining oil to the pan and lightly sauté the onions until they are transparent. Add them to the veal with the sun-dried tomatoes. Sprinkle the flour into the oil left in the pan and stir briskly as it slightly darkens in colour. Remove the pan from the heat and pour over the strained marinade, whisking steadily. Put the pan back on the heat, and bring to the boil, still whisking. Pour the sauce over the meat and vegetables, tuck in the bay leaves. The sauce should just cover the meat so it will probably be necessary to add a little hot water. Simmer over low heat for 1¼–1½ hours.

Blanch the frozen artichoke hearts for 2 minutes. Drain, cut them in half and add them to the veal. Simmer for a further 12–15 minutes to allow them to heat through, then remove the bay leaves and serve.

Lamb

Cuts to choose

Best end of neck. This has an even layer of outer fat and a little marbling in the flesh. Sold as a rack of lamb, it makes a perfect roast for two. Two racks with bones intertwined and fat side out form a guard-of-honour roast; two racks joined in a circle make a crown roast. Both may be stuffed in the middle. Best end is also sold as cutlets for grilling.

Loin. Usually sold as chops for grilling or frying. The meat is lightly marbled and there is a layer of fat on the outer edge of the chops. Loins left joined by the backbone can be sliced to form butterfly chops, or kept whole to roast as a saddle. A single loin can also be roasted, on or off the bone. Noisettes are cut from a boned, rolled loin.

Chump. A cut from between the loin and the leg; sometimes sold as a prime joint for roasting, but more frequently as chops.

Leg. The leg provides a succulent joint for roasting, either whole or divided into two small joints, the fillet end and the shank or knuckle. Steaks cut across the fillet end can be grilled or braised. A braised leg of lamb also makes a very good dish.

Shoulder. Has more fat and is more gelatinous than the leg. For roasting it is best boned and rolled, with or without a stuffing. Left on the bone it is difficult to carve. Shoulder can also be braised as a whole or half joint (blade or knuckle end). Boned and trimmed of fat and membrane, it can be cubed or minced.

Breast. A thin, fatty, well-flavoured cut, often sold boned when it can be stuffed and braised.

Shank. This gelatinous cut from the lower leg makes well-flavoured stews. Fore shanks are the meatiest, rear shanks are usually sold with the leg.

Neck. The middle neck is fatty and tough, best suited to stewing. The scrag is more bony; it is sometimes sold in slices and is also best stewed.

Preparing lamb loin chops

Cut off excess fat, especially from the long flap of skin, keeping the skin intact. Wrap the skin around the meat and secure with a toothpick. This makes a neater and easier shape to grill or fry, and the skin protects the meat.

Stuffing a breast of lamb. See p. 326.

Removing the pelvic bone from a leg of lamb

With the cut surface of the meat towards you, cut round the exposed surface of the pelvic bone with a small sharp knife, separating the flesh from the bone. Follow the shape of the bone, cutting deeper into the flesh until you expose the ball-and-socket joint that connects it to the thigh. Cut through the tendons joining the bones and the pelvic bone will become free.

Crown roast of lamb

For 6

1 crown roast

1–2 tbs olive oil

1 tsp finely chopped rosemary leaves

1 tsp chopped thyme leaves

salt and freshly ground pepper

Have the lamb at room temperature for an hour before you intend to roast it. Heat the oven to 230°C, 450°F, gas 8. Rub the meat with olive oil, sprinkle with the herbs and season with salt and pepper. Wrap the tops of the bones with foil to prevent them from burning. Roast for 15 minutes, then reduce the temperature to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4, and cook for a further 25–35 minutes, depending on how well cooked you want your lamb. Baste the meat from time to time as it roasts. Let it stand for 10–15 minutes in a warm place, covered with a piece of foil, before serving.

Just before serving, fill the centre with cooked vegetables tossed in a little butter or olive oil: new potatoes, peas, french beans, asparagus tips, small carrots in summer; Jerusalem artichokes, little onions, cubes of pumpkin in winter. Remove the foil from the tops of the ribs and carve down between the bones. Serve on hot plates.

Roast leg of lamb

For 8

1 leg of lamb weighing about 3kg

1–2 tbs olive oil

For the marinade

2 tbs finely chopped mixed herbs – thyme, marjoram, savory, parsley

1 garlic clove, peeled and crushed

freshly ground pepper

1 tbs olive oil

60ml white wine

For the gravy

400ml vegetable or chicken stock (p. 4)

3 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

2 sprigs thyme

100ml white wine (or more stock)

Remove all excess fat from the lamb, and ideally remove the pelvic bone (see opposite). Combine the chopped herbs with the garlic, season with pepper and moisten with the oil to make a paste. Make slits in all sides of the meat and push in some of the paste. Rub the meat all over with any remaining paste and with the wine and marinate in the refrigerator for up to 5 hours. Take it out about an hour before cooking, so that the meat comes to room temperature.

Heat the oven to 230°C, 450°F, gas 8. Rub the lamb with olive oil. If you use a meat thermometer, insert it in the thickest part of the leg, but avoid contact with the bone. Roast for 10–12 minutes per 500g for rare lamb or 15 minutes per 500g for medium lamb, but after the first 15 minutes reduce the heat to 180°C, 35°F, gas 4. (To use a meat thermometer, see p. 312.) Baste the meat from time to time with its juices. Allow the meat to rest, covered with foil, in a warm place for 15–20 minutes before carving.

Whilst the meat is resting, prepare the gravy. If there is excess fat in the pan blot it up with kitchen paper. Deglaze* the pan with the stock, scraping up any bits stuck to the bottom. Strain into a small pan. Add the garlic, the thyme and the wine, and reduce to about 200ml. Strain before serving. Serve the meat on hot plates.

Baked lamb chops with potatoes and tomatoes

For 4

8 loin chops or 4 chump chops

3 tbs olive oil

salt and freshly ground pepper

100ml red wine

500g potatoes, peeled and sliced thinly

8 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

4 tomatoes, quartered

2 tsp finely chopped rosemary leaves

½ tsp paprika

100ml water

Heat the oven to 190°C, 375°F, gas 5. Remove excess fat from the chops. Heat the oil in a frying pan and brown the chops for 2–3 minutes on each side. Remove the chops, season with salt and pepper and set aside. Add the wine to the pan, scrape up any bits stuck to the bottom, and let the wine reduce by about half. Mix together the potatoes, garlic, tomatoes and rosemary. Put half of the mixture into a fairly shallow ovenproof dish, season with salt, pepper and paprika and place the chops on top. Spoon over the juices from the frying pan. Put the rest of the vegetables over the top, season and pour over water to cover. Cover and bring to the boil. Transfer the dish to the oven and bake for 45 minutes, then remove the lid and bake for another 30–40 minutes. Add a little boiling water if the dish seems to be drying out.

Grilled lamb noisettes

For 4

1 large onion, peeled

1 tsp salt

3 tbs olive oil

8 noisettes

1½ tbs mixed chopped herbs – thyme, savory, marjoram, rosemary or herbes de Provence

½ tbs crushed black peppercorns

Chop the onion very finely and put in a small bowl. Sprinkle the salt over it and leave for 5–10 minutes. Now squeeze the onion in your fist to extract the juice, combine this with the oil and rub the mixture into the noisettes on both sides. Scatter half the herbs and peppercorns in a shallow dish, put in the noisettes in a single layer and scatter the rest of the herbs and pepper on top. Cover and marinate for 2–3 hours, or longer if you prefer.

Heat the grill or a ribbed griddle pan and grill the noisettes until brown outside but still pink inside – they will take 6–9 minutes, turned once, depending on their thickness and how pink you like your lamb. Serve at once with lemon quarters.

Note

Chops can be prepared in the same way, but take longer to cook. Thick loin chops will need about 12 minutes, chump chops up to 20 minutes. If you have more meat increase the other ingredients accordingly.

Lamb fillet with aubergine purée and yogurt dressing

The lamb and aubergine can be baked in the oven, or grilled on a barbecue. A thick yogurt is best for the dressing; if you prefer to use a low-fat yogurt, strain it first.

For 4

2 garlic cloves

salt and freshly ground pepper

2–3 tbs lemon juice

200ml yogurt

4 tbs chopped mint

2 aubergines, about 350g each

3 tbs olive oil

2 lamb fillets

First prepare the yogurt dressing. Crush the garlic with a little salt. Whisk half of it into the yogurt with 1 tbs lemon juice. Season with pepper and stir in the mint. Set aside until needed.

Prick the aubergine skin in 2 or 3 places and bake in the oven preheated to 230°C, 450°F, gas 8, for 20–30 minutes, until the aubergines are soft. Then put them in a pan or bowl and cover with a lid and leave until they are cool enough to handle. Turn down the oven to 200°C, 400°F, gas 6.

Heat 2 tbs oil in a small roasting tin, and seal the lamb fillets quickly over high heat. Transfer the tin to the oven and roast for 10–12 minutes for lamb that will be still pink in the centre or 14–16 minutes for medium lamb.

While the lamb is cooking, peel off the aubergine skin, put the flesh into a bowl, add lemon juice to taste, the remaining garlic and oil; season. Blend to a purée with a fork. Keep the purée warm.

Slice the lamb fillets, arrange them on a bed of aubergine purée and serve the yogurt dressing separately.

To barbecue Grill the pricked aubergines for about 20 minutes and the lamb for 8–10 minutes to serve pink or 12–14 minutes for medium, turning once.

Lamb with pumpkin, prunes and apricots

The peoples of the Caucasus have a rich tradition of lamb stews with fruit and vegetables. Herbs play a more important part in the flavouring than spices.

For 4–6

150g dried apricots

150g prunes

50ml sunflower oil

800g leg or shoulder of lamb, cubed

2 onions, peeled and chopped

1 tsp allspice

salt and freshly ground pepper

750g pumpkin (first weight), peeled, seeded and cubed

4 tbs chopped dill

4 tbs chopped mint

Soak the apricots and prunes for 3–4 hours unless you are using ready-to-eat fruit. Stone the prunes. Heat the oil in a large pan and sauté the lamb and onion until the lamb is browned on all sides. Sprinkle over the allspice, salt and pepper. Pour in enough water just to cover the lamb, cover the pan and simmer over low heat for 45 minutes. Taste to see if the lamb is getting tender. If it isn’t, let it simmer longer. Add the pumpkin and the fruit. Cover the pan and simmer for a further 30–40 minutes. Check the seasoning, stir in the herbs and serve.

Lamb tagine

The Moroccans have some of the best slow-cooked dishes in the world, usually based on lamb or chicken, with the addition of vegetables (artichokes, peas, broad beans, carrots) or fruits (apricots, dates, prunes, quinces), each with subtly different seasoning. This version is flavoured with olives and preserved lemons and is based on a recipe from a little book of the 1950s, Fes vue par sa cuisine, by Z. Guinaudeau. A tagine is a handsome earthenware dish with a tall conical lid; as in many cultures, the pot has given its name to the food cooked in it.

For 4–5

1kg lamb, shoulder or leg

½ tsp saffron threads

100ml olive oil

1 tsp ground ginger

½ tsp ground chilli or red pepper flakes

salt

100ml water

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

1 large onion, peeled and chopped finely

a small bunch each of parsley and coriander

150g green or violet olives

2 preserved lemons (p. 513)

juice of ½ lemon

Trim any excess fat from the lamb and cube the flesh. Soak the crushed saffron in a little hot water. Put the oil, spices and salt to taste in a heavy pan, stir thoroughly whilst pouring in, a little at a time, 100ml water, as if making mayonnaise.

Turn the meat in this emulsion over moderate heat until it colours, then add just enough more water to cover it. Bring to the boil, cover the pan and simmer over very low heat for 1 hour. Add the garlic, onion and bunches of herbs to the pot, cover again and simmer for a further 45–50 minutes, until the meat is very tender. Whilst it is cooking, stone the olives, remove the pulp from the lemons and cut the peel into strips. Add the olives, peel and lemon juice 10–15 minutes before the end of cooking.

Remove the meat and keep it warm in a tagine or other earthenware dish, boil down the sauce rapidly to about 350ml. Discard the herbs, check the seasoning. Spoon the sauce over the lamb, arranging the olives and lemon peel on top.

Lamb shanks with garlic

This dish is simple, quick to prepare and can be simmered for up to 3 hours without coming to harm – the meat just gets more tender. It is unwieldy to make in large quantities though and having a couple of large pans on the cooker can be a nuisance. The shanks could be braised in a low oven, at 170°C, 325°F, gas 3.

For 4

4 lamb shanks, weighing 300–500g each

3 tbs olive oil

1 large onion, peeled and chopped

8 or more garlic cloves, peeled

bouquet garni* of thyme and bay leaves

2 tomatoes, peeled, seeded and quartered

2 sun-dried tomatoes, chopped

salt and freshly ground pepper

200ml white wine

300ml vegetable or chicken stock (p. 4) or water

Trim excess fat from the shanks. Heat the oil in a large pan which will hold the shanks side by side and brown them on all sides. Add the onion and stir occasionally until it starts to colour, then put in the garlic, herbs and both lots of tomato; season with salt and pepper. Pour over the wine and stock. Bring slowly to the boil, cover tightly and simmer over very low heat for 1½ hours or until the meat is starting to come loose from the bone. Check the pot from time to time to see that it is simmering gently, and that it is not necessary to add a little more stock or water.

Remove the lid and simmer for another 30 minutes or so. The meat should be very tender and the sauce reduced. Skim off excess fat before serving. If there is still too much liquid, remove the shanks to a bowl and keep warm whilst you skim the cooking liquid and boil it down further over high heat.

A potato or celeriac mash (p. 154) would go well with this.

Variation

• Add 100g small black olives for the last 30 minutes of cooking.

Saffron pilaf with lamb and almonds. See p. 182.

Rogan josh

This mildly spiced dish thickened with yogurt or curds comes from northern India. Rogan josh reheats well, and is even better the second day.

For 4

1kg lamb, leg or shoulder

600ml oil or 60g ghee*

pinch asafoetida* (optional)

1 tsp ground ginger

4 cloves

250ml thick yogurt

1 tbs coriander seed, dry-roasted* and ground

1–2 tsp chilli powder

seeds from 4 cardamom pods*, crushed

½ tsp ground mace

salt to taste

1–2 tsp garam masala*

4cm piece fresh ginger, peeled and shredded

Cut the lamb into pieces about half the size of a postcard. Heat the ghee or oil in a heavy pan and stir in the asafoetida, ground ginger and cloves. Add the meat and about a third of the yogurt. Cover the pan and simmer until the liquid dries up. Stir in another third of the yogurt, scraping up any bits sticking to the pan. Cover and simmer again until the liquids dry up. The meat should be golden brown. Remove the pan from the heat and again scrape up any bits that are sticking.

Return the pan to the heat, add the coriander, chilli, cardamom and mace with the rest of the yogurt. Stir thoroughly. Add just enough water to cover the meat, put on the lid and simmer until the lamb is tender, about 1 hour.

Taste and add salt if necessary. Sprinkle over the garam masala and shredded ginger, cover again and simmer for 15–20 minutes until the flavours are well blended. Serve with rice.

Pork

Cuts to choose

Loin. A prime tender cut with a thin outer layer of fat. It makes a very good roasting joint, especially if boned and stuffed. It is otherwise sold as chops for grilling, barbecuing or frying. Back bacon is cured loin.

Chump end. This is the back part of the loin, usually sold as chops which are much meatier than the loin chops. It can also be roasted whole.

Fillet or tenderloin. Lies beneath the middle loin and the chump end. From a small animal, it is sold as part of the loin, but may be separated out as a lean tender cut. Fillet is a good cut to pot-roast; for roasting it should be wrapped in fat or bacon so that the meat doesn’t dry out. It can also be sliced into medallions. The meat has a delicate flavour and benefits from added liquid and flavourings.

Leg. Often sold as two joints – fillet end and knuckle or shank end. The fillet end is very good roasted on the bone, or it may be sold sliced like a steak or in smaller escalopes. The knuckle end is more bony but still a good roasting cut. It is also salted and sold as ham or gammon, depending on the cure.

Belly. A fatty cut from the abdominal wall that can be roasted or grilled. It is excellent salted as streaky bacon or as salt pork.

Spare ribs. These are cut from the thick end of the belly and may be barbecued, grilled or roasted, as a piece or separately, often glazed with a sauce.

Shoulder. Usually cut as two pieces: the upper neck end, mostly sold as chops, and the lower blade with the shoulder bone. The fatty tissue in the meat makes it suitable for braising and roasting. Collar bacon is cured neck end.

Hand. This cut from the foreleg is coarser than the meat from the hind leg and best suited to stewing, although the hand is also sold boned and rolled for roasting and braising.

Hock. The lowest part of the leg which is often cured in brine. Best for stewing and poaching.

Trotters. The feet need long slow poaching in court-bouillon, then they are rolled in breadcrumbs and grilled. In France, you can buy them ready-prepared for grilling. Their high gelatine content makes them useful for enriching stews and stocks.

Back fat is cut in thin sheets used for larding and barding, p. 326.

Salting pork

Pork is more intensively reared than other domesticated animals, has less fat than it used to have and less flavour. It benefits from a light salting; even rubbing sea salt over a piece of pork a few hours before cooking will improve the taste.

Removing the pelvic bone from a leg of pork or ham

Follow the instructions for a leg of lamb on p. 330.

Scoring pork for crackling

If you like crackling, with a very sharp knife cut parallel lines 1cm apart across the skin. Rub well with oil and salt to crisp the fat. Do not baste during roasting, or it will go limp.

Roast loin of pork stuffed with apricots

A roast loin of pork is a handsome and easy dish to prepare for several people. This version includes a stuffing, but if you don’t want to go to that trouble, some crushed garlic and a few chopped herbs – rosemary, sage, thyme or fennel – spread over the meat before rolling and tying will flavour it well. Any leftover roast is excellent cold.

For 8

1 loin of pork, weighing about 2.5kg, boned and skin removed

For the stuffing

150g ready-to-eat dried apricots, chopped

1 small onion, peeled and finely chopped

100g unsalted pistachios, chopped

100g fresh white breadcrumbs

1 tsp thyme leaves, chopped

½ tsp ground coriander or anise seeds

salt and freshly ground pepper

juice and grated zest of 1 unwaxed orange

1 egg

Trim the pork fat to obtain an even layer. Combine apricots, onion, pistachios, breadcrumbs and seasonings, including the orange zest. Moisten with the orange juice and bind with the lightly beaten egg. If the result is too dry, add a little more orange juice. Spread the stuffing over the meat, roll up and tie. Weigh the stuffed joint to calculate the cooking time (see p. 312).

Heat the oven to 220°C, 425°F, gas 7. Roast the pork for 15 minutes, then reduce the temperature to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4. It will take about 2½ hours. Baste every 20 minutes with the pan juices. Pork must be well cooked and it is properly cooked through when a meat thermometer, if being used, shows 75°C, 170°F or when the juices run clear if the thickest part of the meat is pierced with a skewer. Leave to rest, covered, in a warm place for 15 minutes before carving. Serve on hot plates.

Baked pork chops

These baked chops make a quickly prepared supper dish and the flavourings can be changed to suit your taste. Replace the sage with ¼ tsp chilli flakes or paprika, or crush the garlic with ½ tsp fennel or coriander seeds.

For 4

4 pork chops

salt and freshly ground pepper

8 sage leaves

sprig of rosemary

2 garlic cloves, peeled

1 tbs olive oil

a glass of white wine

Heat the oven to 190°C, 375°F, gas 5. Trim excess fat from the chops and season with salt and pepper. Chop the sage leaves together with the leaves from the rosemary, and the garlic. Rub the mixture into the chops on both sides. Lightly oil an ovenproof dish and put in the chops. Pour over the wine and add enough water just to cover the meat. Cover the dish and put it into the oven for 30 minutes, then remove the lid and continue to bake for a further 20–25 minutes or until the chops are well cooked and the sauce reduced. Test the chops; when they offer no resistance to a skewer they are ready. The cooking time depends on thickness as much as weight.

The chops are very good with a dish of quinces or apples stewed with onions.

Pork medallions with lime

For 4

2 unwaxed limes

5 tbs olive oil

2 small garlic cloves, peeled

8 medallions cut from the fillet, about 700g

2 tbs chopped parsley

salt and freshly ground pepper

Prepare a marinade with the juice of ½ lime, 3 tbs oil and 1 crushed clove of garlic. Pour it over the meat and leave for an hour. Grate the zest of the whole lime and combine it with the remaining clove of garlic, finely chopped, and the parsley. Set aside to garnish the pork.

Heat the oven to 180°C, 350°F, gas 4. When you are ready to cook, pat dry the medallions with kitchen paper and heat the remaining oil in a frying pan. Season the meat with salt and pepper and brown it on both sides. Transfer to an oven dish and bake for 8–10 minutes, depending on the thickness of the medallions. Just before the meat is ready add the juice of the remaining limes to the frying pan and stir well, scraping up any bits stuck to the bottom. Put the pork onto a serving dish, spoon over the sauce, sprinkle over the garnish and serve.

Pork satay with peanut sauce

I first discovered satay in one of the many Indonesian restaurants in Holland and fell for the lightly spicy taste of the meat and decidedly moreish peanut sauce. For those who can’t eat peanuts, try another relish, tomato sambal (p. 384), to accompany the satay. You can make satay also with chicken, beef or lamb, and adjust the flavours of the marinade to suit your taste.

Kecap manis is a thick, sweetish soy sauce from Indonesia and Malaysia. It is not interchangeable with Chinese or Japanese soy sauces, although one of those with a little sugar can at a pinch be used instead. It is available from oriental shops.

For 4

3 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp ground coriander

2 tbs soy sauce

1 tsp sugar

1 red chilli, sliced

750g leg or fillet of pork, cut into small cubes

1 tbs sunflower oil

For the peanut sauce

4 medium onions (500g), peeled and chopped finely

2 tbs sunflower oil

1 tsp ground cumin

4 tbs smooth peanut butter (150g)

2 tbs very thick coconut cream

3 tsp sambal* or similar chilli condiment

2 tsp kecap manis or other dark soy sauce (optional)

Combine the first six ingredients, and marinate the meat, turning it to coat it well as you put it into the dish. Cover and leave in the refrigerator for several hours.

The sauce needs time to cook and time to mellow, so make it well ahead of barbecuing the satay. Put the onion in a heavy pan with the oil and the cumin, stir to coat, cover and leave on a diffuser mat on medium heat for 20 minutes. Turn the heat to low and leave for another 30–40 minutes by which time the onions will be very soft and have made a fair amount of liquid.

Stir in the peanut butter and the coconut cream, and leave for another 30 minutes. Take the pan off the heat and stir in the sambal and, if you prefer a somewhat deeper flavour, the kecap manis. Leave to stand for several hours. When needed, heat through gently.

Remove the pork from the marinade and thread the cubes onto skewers. If you use wooden skewers, soak them in water first for 15 minutes so that they don’t burn. Grill on the barbecue for 10–12 minutes, basting with oil and turning frequently, or cook under an indoor grill. Serve accompanied by rice and the sauce.

Stir-fried pork with cashew nuts

Follow the recipe for Chinese stir-fried chicken on p. 284, replacing the chicken by shredded pork. If you wish, use a mixture of vegetables instead of the mushrooms.

Pot-roasted pork fillet

For 2–3

1 pork fillet (tenderloin), weighing 450–500g

salt and freshly ground pepper

30g butter

juice of 1 orange

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

½ tsp ground coriander

Trim the pork of any excess fat and sinew. Rub with salt and pepper.

Heat the butter in a heavy pan into which the pork just fits and brown it gently. Pour over the orange juice and stir in the garlic and coriander. Cover tightly, and cook over the lowest possible heat, using a heat diffuser if necessary, for 30–40 minutes. Turn and baste the meat once or twice while cooking. Pierce the meat with a skewer towards the end of cooking time; if the juices run clear, the pork is cooked through. It should be tender and moist.

Strain the juices (there won’t be many), slice the pork and spoon the sauce over.

Chinese braised pork and vegetables

We tend to be more familiar with Chinese stir-fried and steamed dishes because these are the ones most commonly served in Chinese restaurants, but there are excellent braised and simmered dishes that are worth knowing about. This recipe can be made with beef if you prefer.

I have used bamboo shoots and snow peas, but mange-tout, Chinese cabbage or mustard greens cut in 1cm slices, sliced leeks or mushrooms or peppers cut in squares are all suitable substitutes.

For 2

250g pork, fillet or leg

2 tbs sunflower oil

1 tbs rice wine* or sherry

2 tbs soy sauce

1 tbs sugar

salt to taste

100ml vegetable or chicken stock (p. 4)

100g bamboo shoots, sliced

100g snow peas, topped and tailed

1 tsp cornflour or potato flour

1 tbs water

Trim the meat and cut into 2cm cubes. Heat a wok or pan over high heat until you can feel the heat rising from it when you hold your hand above it. Add 1 tbs oil, swirl it around and put in the pork. Stir-fry briskly until it is browned all over. Add the rice wine or sherry and toss for 30 seconds, then the soy sauce, sugar and salt (remember that soy sauce is salty). Toss again and add the stock. Bring to the boil, then immediately cover the pan, lower the heat and simmer gently for 45 minutes. Stir occasionally to make sure the meat has not stuck to the bottom, and check the stock level, replenishing if necessary.

Stir the bamboo shoots and snow peas into the pan and braise for a further 15 minutes. Just before the end of cooking time, check the quantity of sauce. If it is reduced to a few spoonfuls and just coats the food, serve as it is. If it is more liquid, mix the cornflour into the water, then stir into the sauce to thicken it slightly. Serve with rice.

Pork vindaloo

Indian restaurant vindaloos are all too often exercises in providing ‘heat’ from chillies rather than the robust but well-balanced flavours of the authentic stew evolved in Goa by the Portuguese who settled there. The name comes from the Portuguese for wine (vinho) and garlic (alho), and wine vinegar, garlic and chillies are the essential flavourings. The vinegar preserves the meat, and thus allowed it to be kept from one day to the next before the advent of refrigeration. A pickled version is also made, using more vinegar and mustard oil (p. 76). Vindaloo is often served with bread – usually chapatti – but rice also goes well with it.

For 4

500g lean pork, leg or shoulder, cubed

2 tbs sunflower oil

3 onions, peeled and sliced finely

4 garlic cloves, peeled and sliced finely

6 black peppercorns

4 cardamom pods*, crushed

1 tsp salt

1 tsp sugar

2 green chillies, sliced

4 tbs wine vinegar

200ml water

For the spice mix

½ tsp cumin

3–6 dried chillies, seeded

2cm cinnamon stick

4 cloves

½ tsp turmeric

6 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

2cm ginger, sliced

3 tbs wine vinegar

First prepare the spice mix. Grind together the cumin, chillies, cinnamon and cloves – an electric coffee grinder makes an excellent spice grinder. Put the mixture into a blender or mortar with the turmeric, garlic, ginger and vinegar and blend to a paste. Rub this mixture into the meat and marinate for at least 6 hours, turning occasionally. Twelve hours or more would be even better.

Heat a wide heavy pan, pour in the oil and fry the onion until browned. Add the garlic and spices and fry until the garlic starts to colour. Now put in the meat with its marinade, and a sprinkling of water and fry, turning the meat until it is browned all over.

Add the salt, sugar, green chillies, vinegar and water. Lower the heat, cover the pan and simmer for 40–50 minutes or until the pork is tender. If the meat is getting too dry add a little more water. The sauce should reduce and thicken; if it is too liquid, remove the lid and increase the heat for a few minutes at the end of cooking time.

Ham and gammon

Cured pork

Ham and gammon are prepared from the hind legs of the pig. Dry-salting produces the finest flavour and the most tender meat. Some hams are then air-dried, others smoked, depending on the climate and tradition. Both the feed given to the pigs and the wood used for smoking affect the flavour.

It is usually the less expensive hams that are cured in brine, and many are injected with the brine to produce faster – and inferior – results. Hams are sold whole or divided into knuckle and fillet pieces. Some hams – Ardennes, Bayonne, Black Forest, jamón serrano, prosciutto di Parma, prosciutto di San Daniele – are intended to be sliced thinly and eaten raw.

Boiled or cooked hams can be eaten cold or can be cooked further. They have a milder flavour than the raw hams.

To cook ham or gammon

Whole ham