The purpose of this chapter is to report data on family similarity in the perception of individuals’ family environments and to contrast differences in perceptions within parent–offspring pairs (across generations) to differences within sibling pairs (within generations). We then examine influence of family environments on current levels of cognitive performance.

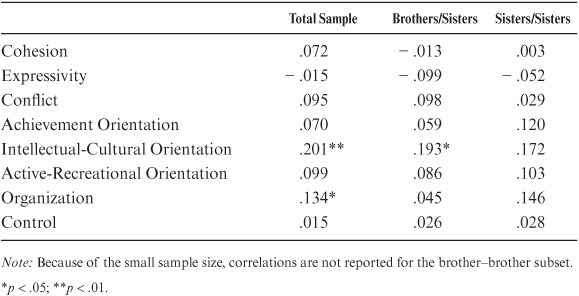

Parent–offspring similarity has traditionally been studied in young adult parents and their children; sibling studies have primarily involved children and adolescents. In this chapter, we report data from the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) on the similarity of perceptions of family environments of parents and their adult offspring and the similarity in such perceptions of adult siblings reported in adulthood. Perceptions of family environments are considered both with respect to the family of origin (i.e., the family setting experienced by our study participants when they lived with their own parents) and with respect to the current family (i.e., their family unit at the time these data were collected). Included in this chapter also are analyses of the relation of perceived family environments to reported current intensity of contact between parent and offspring and between sibling pairs (cf. Schaie & Willis, 1995).

The argument is then made that we can compare the impact of heritability of cognitive performance by examining correlations between parent–offspring and sibling dyads to the shared and unique effects of childhood and current family environments as measured by participants’ reports of their family of origin and current family environments.

Our efforts to measure these perceptions were motivated by the fact that it is extremely difficult to measure current environments objectively, and it is, of course, virtually impossible to obtain such information directly over the quality of environments that pertained at earlier life stages of our study participants. We therefore decided that it was necessary to infer environmental quality by asking our participants to rate both their current environments and their retrospection of the family environment they experienced within their biological family of origin.

We first examine the usefulness of family environment perceptions to measure environmental heterogeneity. That is, we ask the structural question of whether the same dimensions can be used by participants across and within families to describe their current families and their families of origin. We next examine the substantive issues of whether we can demonstrate the existence of generational patterns or secular trends in the perception of family characteristics. We do this by testing whether the strength of family similarity in perception is greater with respect to shared than to unshared environments. This question, moreover, is examined for parent–offspring pairs who have shared the same environment but did so at different life stages, and for sibling pairs who have shared the same environment at the same life stage. To the extent that we can demonstrate differential strength of perceptions within similar environments as opposed to different environments, we also provide indirect evidence supporting the construct validity of measures of the perceived family environment as indicators of actual family environments.

Our measures of family environment (as described in chapter 3) are derived from the work of Moos and Moos (1986), who constructed a 90-item true-and-false family environment scale measuring 10 different dimensions (each measured by nine items), 3 of which they described as relationship, 5 as personal growth, and the remaining 2 as system maintenance and change dimensions. The purpose of these scales was to provide an assessment instrument to that could be used to examine environmental context of adaptation (Moos, 1985, 1987). We adapted eight of the Moos scales for our purposes by selecting five items per scale and presenting each statement in Likert scale form (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = in between, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = strongly agree).

Two forms of the Family Environment Scale were constructed: The first asked that the respondents rate their family of origin (i.e., past tense statement with respect to the parental family); the second form requested the same information (in present tense) with respect to the current family. On each form, respondents were also asked to indicate the membership of both their families of origin and their current families. They were then instructed to do the ratings with respect to the family grouping identified by them. In other words, for the parents this implied rating the “empty nest” family. In recognition of the fact that significant numbers of our young adult and older study participants lived by themselves, an alternate form was constructed that allowed participants to define their current family as those individuals (whether or not related by blood or marriage) who the respondent considered as his or her primary reference group and with whom the respondent interacted at least on a weekly basis.

A confirmatory factor analysis (using LISREL [linear structural relations] 7) was conducted on a random half of the sample of relatives for both forms to determine whether the retained items clustered on the factors described by Moos and Moos (1986). The obtained fit for the family of origin [χ2(701) = 1235.56, p < .001; GFI (goodness-of-fit index) = .842; RMS (root-mean-square) = .084] and the current family [χ2(701) = 1254.48, p < .001; GFI = .839; RMS = .089] was then confirmed on the second random half for the family of origin (χ2(701) = 1266.05, p < .001; GFI = .842; RMS = .090] and the current family [χ2(701) = 1357.07, p < .001; GFI = .829; RMS = .089]. Factor intercorrelations for both scales are shown in table 17.1. Although we obtained a good fit for the primary dimensions, we failed to reproduce the higher-order structure postulated by Moos. Our analyses were therefore limited to Moos’s primary dimensions.

Data relevant to the analyses in this chapter include family members of SLS panel members who participated in the 1984 data collection. These persons were tested in 1989–1990 and were matched with the panel members who were still in the panel in 1991. Subsequent to matching target participants and their relatives, we were able to identify 452 parent–offspring and 207 sibling pairs for whom complete data is available, for a total sample of 1,318 individuals. These consist of 85 father–son, 110 father–daughter, 96 mother–son, 161 mother–daughter, 28 brother–brother, 106 brother–sister, and 73 sister–sister pairings. The reduction in sample size occurred because of substantial attrition in the number of study members whose relatives we had been able to assess earlier; among the older study members, attrition was attributable primarily to death or sensory and motor disabilities that precluded further assessment or questionnaire response.

Average age of the parents was 70.26 years (SD = 9.24), and it was 39.94 years (SD = 8.64) for the offspring. The parents averaged 14.46 years of education (SD = 2.86) as compared with 15.56 years of education (SD = 2.41) for their children. Total family income averaged $24,681 for the parents and $26,841 for the offspring, respectively. Average number of children was 3.53 for the parental and 1.45 for the offspring generation.

Average ages for the siblings were 63.23 years (SD = 12.78) for the longitudinal study members and 61.06 years (SD = 13.16) for their relatives. The target siblings averaged 14.90 years of education (SD = 3.25) as compared with 14.62 years of education (SD = 2.78) for their brothers or sisters. Average incomes were $26,416 for the longitudinal study members and $25,682 for their siblings. Average number of children was 3.09 for the longitudinal participants and 2.69 for their siblings (also see Schaie & Willis, 1995).

TABLE 17.1. Intercorrelation of Family Environment Scales (Family of Origin Above Diagonal, Current Family Below Diagonal)

Three sets of relationships can be considered. The first is the correlations between family environment perceptions of parents and offspring with respect to their family of origin, their nonshared and temporally distinct environment. The second concerns the correlation of perceptions of the current families, of parents and adult offspring, the nonshared but temporally concurrent environment. Finally, there is the correlation of the offspring’s perception of their family of origin with their parent’s perception of the parent’s current family, the shared environment. The first two sets of relationships involve comparisons of the same life stage across generations, but representing different families for each generation. The third set of relationships is concerned with the perceived similarity of the family environment within the same family across generations. In comparing correlational patterns (magnitude of correlations) across generations, within life stages, and across different gender pairings, a generalized maximum likelihood test is employed to test the statistical significance of differences between correlation patterns.

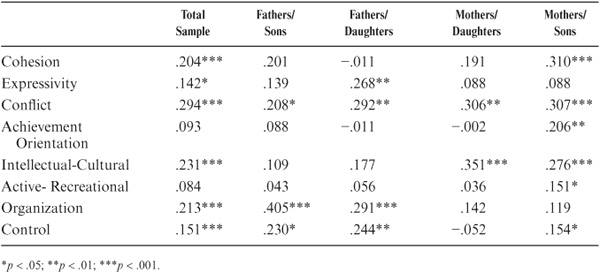

For the total sample, significant, but modest, correlations between parents and offspring are found for the dimensions of Cohesion, Expressivity, Conflict, Intellectual-Cultural, Organization, and Control (see table 17.2). The highest overall correlation amounted to .294 for Conflict. When analyzed separately by gender pairing, a significantly different pattern is found for the correlations for the father–daughter and mother–daughter combinations [χ2(8) = 24.71, p < .01]. The relationships for Cohesion and Active-Recreational Orientation remain significant only for mothers and daughters, the relationship for Expressivity only between fathers and daughters, that for Intellectual-Cultural Orientation between mothers and their children (regardless of gender), and for Organizational between fathers and their children. The relationship for Conflict holds for all gender pairings; that for Control holds for all except the mother–son pairings.

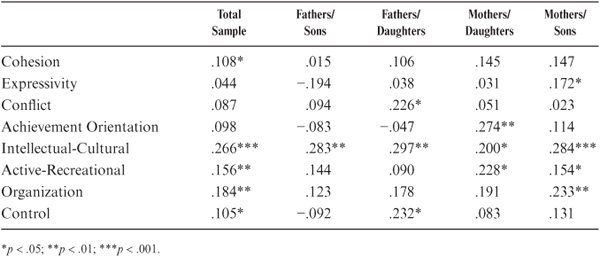

Somewhat lower correlations were found when our participants’ perceptions of their current families were compared across the two generations. Overall, correlations were significantly lower for the current correlations than for the origin correlations for the father–son [χ2(8) = 17.71, p < .05] and mother–daughter [χ2(8) = 12.46, p < .05] combinations. However, significant overall correlations also were observed here for the dimensions of Cohesion, Intellectual-Cultural, Organization, and Control (see table 17.3). When gender pairings were considered, additional significant correlations were found for mothers and daughters on Expressivity and for fathers and daughters on Conflict. The relationship for Achievement Orientation remained significant only for mother–son pairings, for Active-Recreational Orientation for mothers and their children (regardless of gender), for mothers and daughters on Organization, and for fathers and daughters on Control. However, the correlational patterns did not differ significantly across pairings.

TABLE 17.2. Correlation Between Parents and Offspring in Their Perceptions of Family Environment in Their Family of Origin

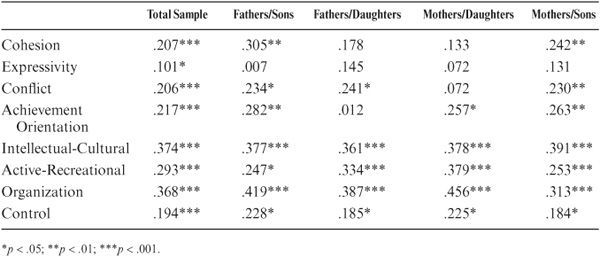

Here, the magnitude of the relationship between the parents’ current environment and their offsprings’ perception of their family of origin is investigated. This is presumably the same family at different life stages, when the offspring were part of the parental family, and that same family now in its postparental phase. Even though the actual family composition has, of course, changed, we found that correlations were substantially higher for this comparison and were statistically significant for the total sample for all dimensions (see table 17.4). Statistically significant correlations were found also for all gender pairings for the Intellectual-Cultural, Active-Recreational, Organization, and Control dimensions.

TABLE 17.3. Correlation Between Parents and Offspring in Their Perceptions of Family Environment in Their Current Family

Significant correlations were found for same gender (father–son and mother–daughter) pairings for Cohesion and for all but mother–son pairings for Conflict. Correlational patterns did not differ significantly by gender pairing. However, these correlations were significantly higher than those found for the family of origin ratings across the two generations’ ratings for the total sample [χ2(8) = 31.38, p < .001] as well as the father–son [χ2(8) = 17.71, p < .05], father–daughter [χ2(8) = 15.51, p < .05], mother–son [χ2(8) = 22.88, p < .001], and mother–daughter [χ2(8) = 15.80, p < .05] gender pairings. They were also significantly higher than the cross-generational correlations for their current families for the total sample [χ2(8) = 30.87, p < .001] and for the father–son [χ2(8) = 29.95, p < .001] gender pairing.

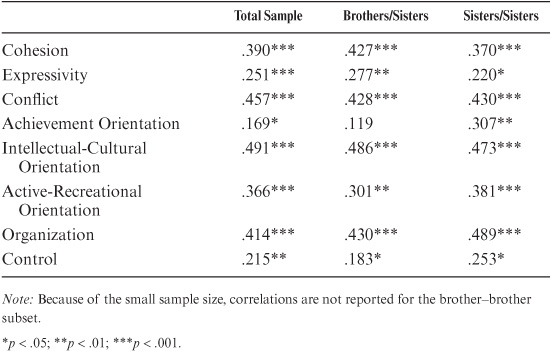

The sibling comparisons were, of course, made within the same generation. However, it should be noted that for the siblings the ratings for the family of origin reflect perceptions of the same family at the same life stage; ratings of the current family reflect membership in different families. Because of the small sample size for brother–brother pairings (N = 28), gender-specific data are provided only for the brother–sister and sister–sister pairings.

Statistically significant correlations were found for all family dimensions, ranging from a low of .191 for Achievement Orientation to a high of .491 for the Intellectual-Cultural dimension. Correlational patterns did not differ significantly by gender pairings, and the correlational values remained significantly different from zero, except for Achievement Orientation, which did not reach significance for the brother–sister pairs (see table 17.5).

TABLE 17.4. Correlation Between Parents’ Perception of Their Current Family and Offsprings’ Perception of Their Family of Origin

The comparison of siblings’ perceptions of their current families yielded few significant correlations. Overall, low but significant correlations were found for the Intellectual-Cultural and Organization dimensions. However, when broken down by gender pairings, only the correlation between brothers and sisters for the Intellectual-Cultural dimension remained significant (see table 17.6). Magnitudes of correlations for the perception of current families were significantly lower than for the family of origin for the total sample [χ2(8) = 51.11, p < .001], as well as for the brother–sister [χ2(8) = 30.96, p < .001] and sister–sister [χ2(8) = 21.87, p < .01] pairings.

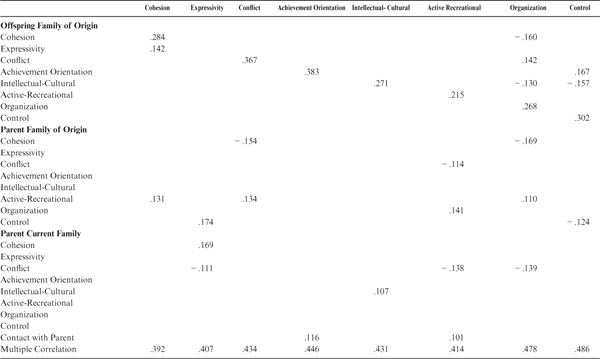

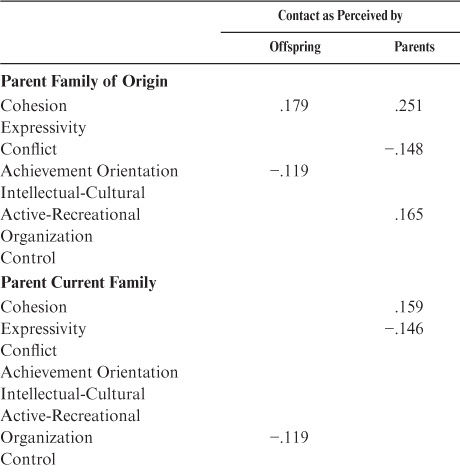

Next is considered the extent to which parental perceptions of family environment, and the offsprings’ perception of the environment prevailing in their family of origin, as well as extent to which contact between offspring and parents affects the offsprings’ perception of their current family environment. Table 17.7 provides the relevant β weights and multiple correlations. The magnitude of the relationship was highly significant, and between 20% and 25% of the variance in perceptions of current family environment can be accounted for. Note that the major significant predictor for each dimension of the current family environment was the corresponding dimension in the offsprings’ perception of their family of origin. However, in each case, one or more parental perception of their current or original family contributed significantly to the variance in the offsprings’ perception. Interestingly, however, frequency of contact with parents (see chapter 15) contributed little variance to these predictions (see table 16.7).

TABLE 17.5. Correlation Between Siblings’ Perception of Their Family of Origin

TABLE 17.6. Correlation Between Siblings’ Perception of Their Current Family

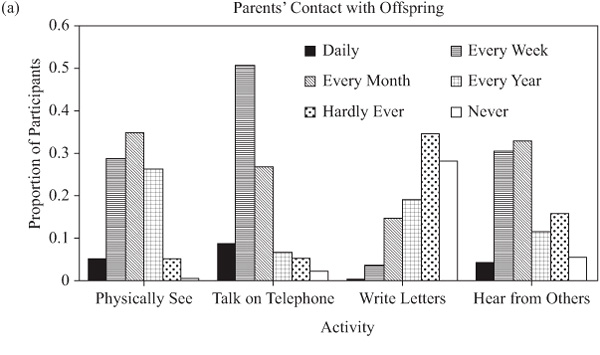

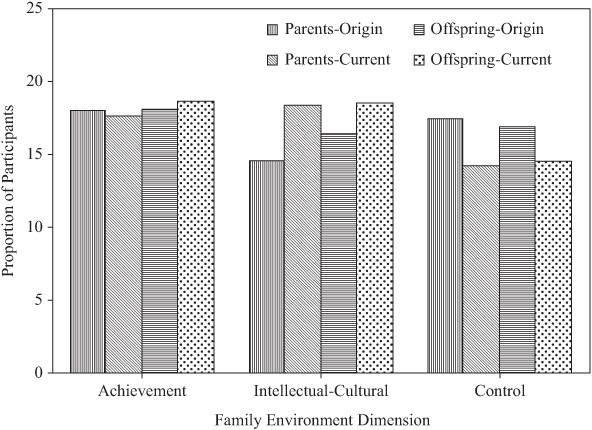

Do perceptions of family environments of parents and offspring, both current and in their family of origin, influence their reports of frequency of intrapair contact? Reports of frequency of contact were provided by both parents and offspring. The offspring reported slightly more contacts than did their parents (p < .05). The difference in reported contact by the two generations was greatest for the father–son pairings, but the greatest frequency of contact was reported by both parents and offspring for the mother–daughter pairing. There was a significant correlation between contact reported by parents and offspring, but its magnitude (r = .388) was low enough to suggest that different aspects of family perception might influence contact as reported by parents and offspring. Frequency of specific types of contacts is provided in figure 17.1.

Approximately 57% of the parents and 50% of the offspring described the nature of their relationship as “very close.” An additional 29% of the parents and 35% of the offspring described it as “close”; 9% of the parents and 11% of the offspring rated the relationship as “in between”; 3% of parents and offspring rated it as “somewhat close”; and only 1.5% of parents and offspring rated it as “not close at all.”

Almost a fourth of the variance in contact can be predicted from perceptions of family environments. However, the only variable accounting for significant variance in common to parents and offspring is that of Cohesion as rated for the parental family of origin (the grandparental family for the offspring). The other significant predictors for the offsprings’ reports of contact with parents are high Cohesion in the offspring family of origin, high Control in their current family, low Achievement Orientation in the parental family of origin, and low Organization in the current parental family. By contrast, significant predictors for Contact as reported by parents are low Conflict and high Active-Recreational Orientation in their families of origin, high Cohesion and low Expressivity in their current family, as well as high Achievement and Active-Recreational Orientation, low Organization, and high Control in their offsprings’ perception of the parental family (see table 17.8).

TABLE 17.7. Regression Analyses Predicting Offsprings’ Perception of Their Current Family Environment (β Weights: p > .05)

FIGURE 17.1. Proportion of participants having various types of contacts with their offspring or parents.

The focus now shifts to the question of differences in perceptions of family environment both within families across generations and in the perception of differences between our study participants’ parental and current families. Because of the wide age range of the participants and to adjust for possible differences in the age span between individual parent–offspring pairs, we covaried on age of both parents and offspring. A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) design was used in which parental gender and offspring gender were the between-participant effects, generations (parents/offspring) and family stage (family of origin/current family) were treated as within-participant effects, and the family environment dimensions were treated as dependent variables.

TABLE 17.8. Regression Analyses Predicting Parent–Offspring Contact (βWeights: p > .05)

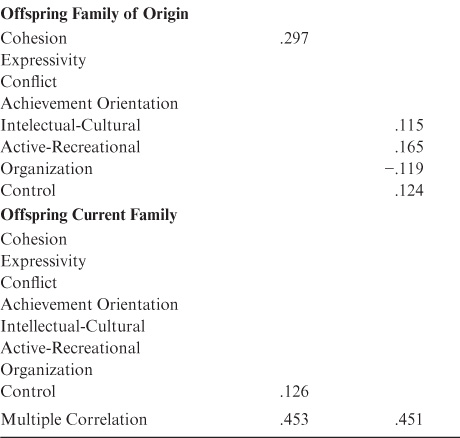

Table 17.9 gives results of the overall MANCOVA, which was then followed by univariate tests for the significant effects of interest. Main effects significant at or beyond the 5% level of confidence were obtained for gender of offspring, generations, and family stage. Two-way interactions were significant for parental gender by family stage and for generations by family stage. There were also significant three-way interactions for parental gender by generations by family stage and for offspring gender by generations by family stage.

Univariate tests indicated that the main effect for offspring sex was significant only for the dimension of Achievement Orientation (p < .01), with men reporting a higher overall level of Achievement Orientation. The main effect for generations was significant for six dimensions (p < .001). The offspring reported lower overall levels of family Cohesion, Organization, and Conflict, but greater Achievement, Intellectual-Cultural, and Active-Recreational Orientation. The family stage main effects were also significant (p < .001) for all dimensions except Achievement Orientation. Higher levels of Cohesion, Expressivity, Conflict, Intellectual-Cultural, and Active-Recreational Orientation were reported for the current family; a higher level of Control was attributed to the family of origin.

The parental gender by family stage interaction was statistically significant for the Cohesion (p < .01), Conflict (p < .05), Intellectual-Cultural (p < .01), and Organization (p < .01) dimensions. Mothers reported significantly lower Cohesion and Conflict for family of origin than for the current family. Their family of origin was also described as significantly lower in Active-Recreational Orientation, and they reported greater Control for the current family.

TABLE 17.9. Multivariate Analysis of Variance of Family Environment Dimensions for Parental Gender, Offspring Gender, Generations, and Family Stages

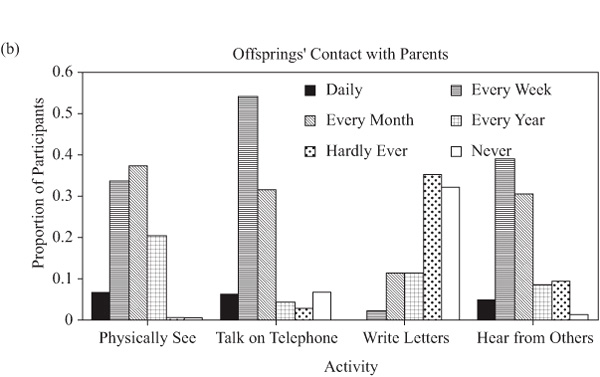

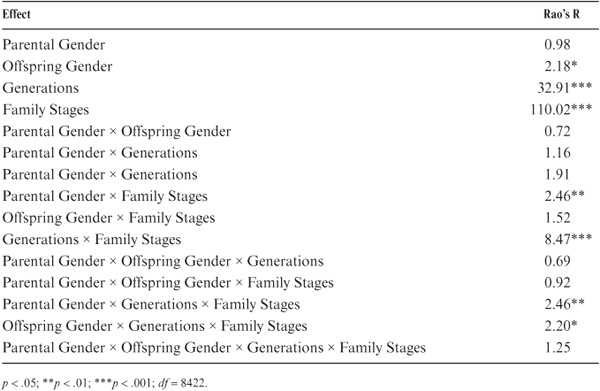

The generations by family stage interaction is of particular interest for our purposes. Here, statistically significant effects were obtained for Achievement Orientation (p < .001), Intellectual-Cultural Orientation (p < .001), and Control (p < .01). Mean scores for these dimensions by generation and family stage are shown in figure 17.2. Achievement Orientation in the current family was rated significantly lower by the parents than by the offspring. Not only was Intellectual-Cultural Orientation rated lower for the family of origin, but it was rated lowest in the parents’ family of origin. Level of Control was reported to be greatest by the parents for their family of origin and was about equally low for the current family of both generations.

Gender differences further complicate the findings with respect to generational/family stage differences in family perceptions. Significant triple interactions for parental gender by generations by family stage (p < .01) were found for the Intellectual-Cultural Orientation, Organization, and Control. Intellectual-Cultural Orientation in their present family was perceived to be higher by mothers than by fathers; Organization was perceived as greater in their current family by sons than by daughters; and Control was seen to be greater in the current family by fathers than by mothers. A significant triple interaction for offspring gender by generations by family stage (p < .001) was found for Expressivity. In the last instance, daughters reported greater Expressivity in their current family than did sons.

For a better understanding of possible intrafamily shifts in perceptions of family environments of successive cohorts, we repeated the analyses in this section by adding four levels of cohort groupings. In terms of the years of birth of the offspring, these were those born prior to 1941 and those born between 1941 and 1947, 1948 and 1954, and 1955 and 1968. Three significant interactions involving cohort grouping were found: cohort by family stage (p < .01), cohort by parental gender by family stage (p < .05), and cohort by generation by family stage (p < .01).

FIGURE 17.2. Interaction of generation and family stage effects.

Significant univariate effects for the cohort by family stage interaction were found for Cohesion (p < .01) and Conflict (p < .001). Perceptions of both dimensions for the current family environment did not differ, but there was a linear decline for successive cohorts in perceptions of Cohesion and Conflict in the family of origin. With respect to the triple interaction of cohort by parental gender by family stage, significant univariate effects were found for Expressivity (p < .001) and Achievement Orientation (p < .05). These effects seem to be accounted for primarily by significant drops in Expressivity in the current family for the men in the most recent cohort, with a concomitant significant increase for the women in that cohort.

For Achievement Orientation, the effects reflect a slight but systematic drop for males in the family of origin and an increase for females in the current family. Finally, the triple interaction for cohort by generation by family stage was statistically significant (p < .05) for Intellectual-Cultural Orientation and Organization. The former effect reflects primarily a significant increase in Intellectual-Cultural Orientation from the oldest to the youngest cohort within the family of origin. The latter reflects the fact that, although there was a general decline in perceived family Organization, this decline apparently reversed for the current families of the most recent cohort.

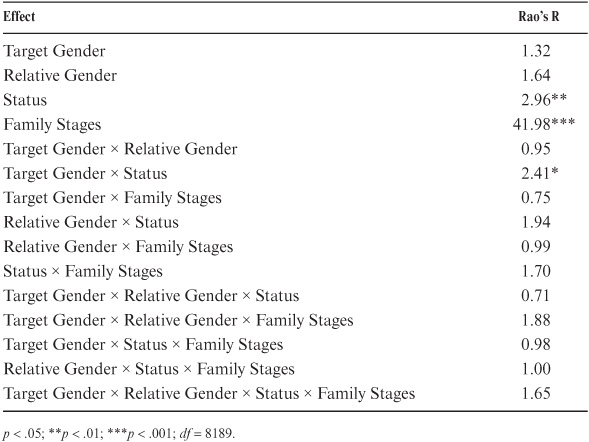

Differences in siblings’ perceptions of family environment were analyzed with a MANCOVA design in which target and relative gender were the between effects, and target versus relative status and family stage (family of origin/current family) were treated as within effects, again with the family dimensions treated as dependent variables. Table 17.10 provides results of the overall MANCOVA, which was followed by univariate tests for the significant effects of interest. Main effects significant at or beyond the 5% level of confidence were obtained for target versus relative status and family stage. A significant two-way interaction was found for target gender by status. None of the higher-order interactions were statistically significant.

Univariate main effects for study status (i.e., whether the respondents were members of the longitudinal panel or their relatives) were statistically significant for the dimensions of Expressivity (p < .01), Intellectual-Cultural Orientation (p < .05), Active-Recreational Orientation (p < .01), and Control (p < .01). Our original study participants reported higher levels of Expressivity as well as Intellectual-Cultural and Active-Recreational Orientations across family of origin and current family than did their siblings. However, the relatives reported a higher overall level of Control. As for the parent–offspring panel, siblings also reported significant differences in family environment between their family of origin and their current family for all dimensions. Higher levels of Cohesion, Expressivity, Conflict, Intellectual-Cultural, and Active-Recreational Orientation were reported for the current family; Achievement Orientation, Organization, and Control were rated higher in the family of origin. The target gender by status orientation was only marginally significant for Cohesion, with women from the longitudinal study reporting greater family Cohesion than did the other groupings.

TABLE 17.10. Multivariate Analysis of Variance of Family Environment Dimensions for Target Sibling, Gender, Relative Sibling Gender, Target Versus Relative Status, and Family Stages

The availability of a loyal panel of long-term research participants such as that in our longitudinal studies of adult competence simplifies the logistics of acquiring family data, hence our successful effort to recruit good-size panels of adult offspring and siblings of our longitudinal study participants. However, when we began to consider the relevance of the SLS as a potential vehicle for studies of family similarity, it became apparent that, although we had available to us extensive longitudinal data on cognitive performance, we had no direct measures of our study participants’ family environments. Although one must always be careful in accepting the veracity of subjective data, particularly when it is retrospective in nature, there is substantial evidence of the utility of perceptions of behavioral dimensions (e.g., in the literature on personal efficacy in adults, e.g., Lachman, 1989), and we have previously obtained useful evidence on our own study participants’ ability to retrospect on their prior performance in the cognitive area (Schaie et al., 1994).

In earlier work with adolescent siblings, Plomin and Daniels (1987) had successfully employed a true-and-false derivative of the Moos and Moos (1986) Family Environment Scales to assess perceptions of the common family environment. It seemed sensible, therefore, to employ these measures for our adult family studies. However, on closer review, the materials in the original scales were deemed too lengthy, and we proceeded with the development of briefer forms that employed Likert scales and were phrased in such a fashion as to be useful for the assessment of families of origin and current families. The psychometric work on these scales mentioned here suggested that we have maintained the dimensionality of the original Family Environment Scales both for retrospective and current reports and have thus created appropriate instruments to obtain data relevant to the questions raised here.

What we have done, then, is to obtain evidence with respect to similarities and differences within and across generations in the perception of eight basic dimensions of family environment. Our data could have been arrayed in a variety of complex ways (for an alternative approach, cf. Rossi, 1989). We elected to analyze data for our adult siblings with respect to within-generation similarities and differences and by studying parent–offspring pairs to determine these relations across generations. Moreover, for each of these analyses, we contrast perceptions of the family of origin and current family (as a within-participant variable). Because of the possibility of shifts in these relationships for successive cohorts, similar to those we have often reported for cognitive variables (cf. Schaie, 1990b), we also elected to include a cohort variable, classifying our offspring into those born prior to World War II, those born during the war years and immediately thereafter, and into the early and late baby boomers.

Our first and most dramatic conclusion is that there is a clear differentiation for parents, offspring, and siblings in the perceived level of all family dimensions between the family of origin and the current family. Obviously, the distance in time was greater for the parents than for the offspring, a factor in part controlled by covarying on respondents’ age. Nevertheless, it seems clear that our respondents perceived shifts in the quality of family environments over their own life course. They saw their current families as not only more cohesive and expressive, but also characterized by more conflict than was true for their families of origin. What these changes reflect, of course, may simply be generally greater openness and engagement in family interactions. More intensive family interactions may also be represented by the reported increase in Intellectual-Cultural and Active-Recreational Orientation from the family of origin to the current family. Concomitant with these shifts as well is the overall perception of lower levels of perceived Control, family Organization, and Achievement Orientation. Perhaps these judgments are another way of measuring the increasing complexity of modern American families (cf. Elder, 1981; Elder & Rudkin, 1995; Hareven, 1982). Combined with continuing reports of ever-lower reported levels of Social Responsibility (cf. Schaie & Parham, 1974), this may well mean that the perceived role of the family is changing from that of a primary socialization agent (operating on behalf of the larger society) to a more effective support system for the needs of the individual family member. When our parent–offspring sample was broken down into four distinct cohort groups, we noted further that the shift in perceived family level occurred primarily for perceptions of the family of origin, with much greater stability for perceptions of the current family. This is reasonable because judgments of the current family occurred at one point in time; judgments with respect to the family of origin necessarily reflected different secular periods for which successive cohorts described their early family experiences.

The second conclusion, with respect to within-family similarity in the perception of family environments, is that sibling (particularly sister–sister) pairs share substantial variance in the perception of their family of origin (i.e., the family they shared in childhood and adolescence) over all family dimensions that we examined. However, this commonality did not extend to their perception of their current (nonshared) families. The only exception to this finding was a low correlation for Intellectual-Cultural Orientation and family Organization. The reported similarity of early environments might support the contention that retrospective perceptions of families over a long time interval represent the validation of the veracity of these perceptions. On the other hand, the shared variance may simply indicate currently shared (and perhaps idealized) perceptions about the childhood family. However, the lack of similarity between current environments might reflect the fact that siblings do not seem to seek to replicate these early family environments.

Third, in spite of the lack of similarity of current family environments in siblings, we found that the best predictor for the level of each dimension of the current family was the corresponding level reported by each person for their family of origin. Perhaps perceptions of the family environment of origin may be one of the factors entering into marital assortativity, even though such perceptions may differ for and may differentially affect the perceptions of current family environments by different siblings.

Fourth, supporting evidence for the continuity of family values and behaviors (cf. Bengtson, 1986) is provided by our finding of substantial correlations between the parents’ description of their current family environment and their offsprings’ description of their family of origin. Even though there is a substantial time gap in the period rated, these two ratings do refer to the same parental family unit. These relationships were particularly strong for the three dimensions most closely reflective of value orientations (Achievement, Intellectual-Cultural, and Active-Recreational) and for family Organization.

Fifth, differences in perceived family environment and the magnitude of similarity across generations will differ by gender pairing and by dimensions, although it is not surprising that the strongest relationships are observed within mother–daughter and sister–sister pairings, even though frequency of contact is only slightly greater than for other relationship combinations.

Sixth, it appears that the intensity (frequency) of contact between parents and offspring has virtually no impact on the similarity of reported family environments. However, there were family environment dimensions (particularly level of Cohesion) that could predict almost a fourth of the variance in the total family contact scores.

Finally, we suggest that the hierarchy of the magnitude of shared perceptions, from low correlations when describing nonshared environments to moderately high correlations when describing commonly experienced environments, provides at least indirect evidence for the contention that self-descriptions of family environments (perceptions) may well be useful indicators of the actually experienced environments.

Another feature of this work has been to show the viability of a system of describing family environments as they affect both within- and across-generation family similarity. As found earlier with respect to cognitive similarity, we were also able to show substantial shared variance with respect to the perceptions of the family of origin. This finding has important implications for behavior genetic studies because it increases the plausibility of using retrospective perceptions as estimates of early shared environments. For the study of intergenerational continuity, our data support earlier literature (cf. Bengtson, 1975) that successive generations tend to evaluate their family environments in rather similar terms. Nevertheless, there is also strong evidence that perceived environments in the newly formed families of the offspring generation are not simply replications of their families of origin but may well represent the outcome of restructured family relations (cf. Green & Boxer, 1985). Hence, the perceived differences in family environments in the current families of successive generations, as well as the substantial differences reported within generations between the perceived environments in their families of origin and their current families, extend the concept of developmental plasticity (Lerner, 1984; Magnusson, 1998) from the level of individual behavior to developmental plasticity in the value system ascribed to whole family units.

An extensive literature has dealt with the relative contribution of inherited predispositions and the influence of both the shared and unique experiences occurring within the family of origin on cognitive functioning in children. Much of this work is derived from twin studies because behavior geneticists have used the twin model as the most convincing paradigm to investigate heritability of intelligence and many other traits (cf. Plomin, 1986). However, because twins represent a rather atypical subset of the general population, the role of family environments has also been investigated in parent–offspring and sibling pairs (e.g., Defries, Ashton, et al., 1976). Most studies reported that roughly half of the individual difference variance in cognitive functioning is attributable to heritability. Very little variance, on the other hand, has been attributed to shared family environments. In fact, it has been argued that the environment in the family of origin has quite unique influence on different siblings (Plomin & Daniels, 1987).

Relatively little is known about the origin of individual differences in the later half of the life span as they might relate to inherited predispositions or to early influences transmitted through the family environment. Again, twin studies dominate (e.g., Jarvik, Blum, & Varma, 1971; Pedersen, 1996, 2000; Rowe & Plomin, 1981), and it is difficult to extrapolate to the more typical case of family similarities among nontwins.

We now present findings from the SLS that may inform us on the relative contribution of heritability of certain cognitive traits and the extent to which current cognitive performance may be attributed to family influences that are shared with other family members during early life as well as the influences of the nonshared family setting currently experienced by our participants (also see Schaie & Zuo, 2001).

For the purpose of studying the influence of environmental factors on cognition, we were able to construct a data set that consisted of 512 parent–offspring and 294 sibling pairs for whom complete data are available, a total sample of 1,612 individuals. These consist of 106 father–son, 118 father–daughter, 115 mother–son, 198 mother–daughter, 51 brother–brother, 139 brother–sister, and 104 sister–sister pairings.

Average age of the parents was 70.59 years (SD = 10.37), and it was 41.76 years (SD = 10.46) for the offspring. The parents averaged 14.22 years of education (SD = 2.75) as compared to 15.64 years of education (SD = 2.49) for their children. Total family income averaged $25,002 for the parents and $26,841 for the offspring.

Average ages for the siblings were 60.75 years (SD = 14.42) for the longitudinal study members and 59.62 years (SD = 14.77) for their relatives. The target siblings averaged 15.04 years of education (SD = 2.80) as compared with 14.90 years of education (SD = 2.72) for their brothers or sisters. Average incomes were $29,361 for the longitudinal study members and $25,682 for their siblings.

The test battery administered to the participants in this study included the basic Primary Mental Abilities battery (Verbal Meaning, Space, Reasoning, Number, and Word Fluency and the IQ and EQ [Index of Educational Aptitude] indices derived therefrom), as well as the three cognitive style factor scores (Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, Attitudinal Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed). Family of origin and current family measures were also available for all participants. Included also was the personality trait of Social Responsibility. All measures are described in chapter 3.

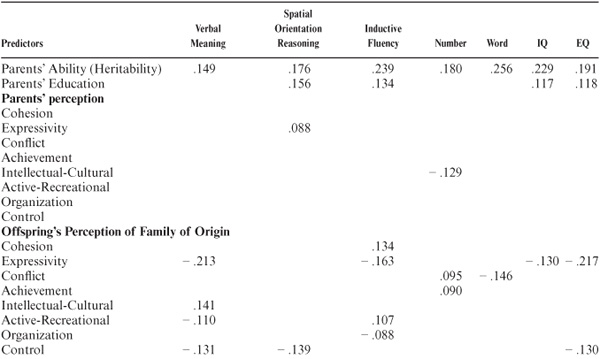

A general linear regression model was fitted to associate each dependent variable (current Primary Mental Abilities and Test of Behavior Rigidity scores) with the significant independent variables. The model was initially chosen by a stepwise model selection procedure. To include all potentially significant independent variables, the level for entering the model was set at an α of p < .10. With independent variables selected from the initial screening step, the linear regression model was then fitted, and independent variables with p > .05 were excluded from the final model.

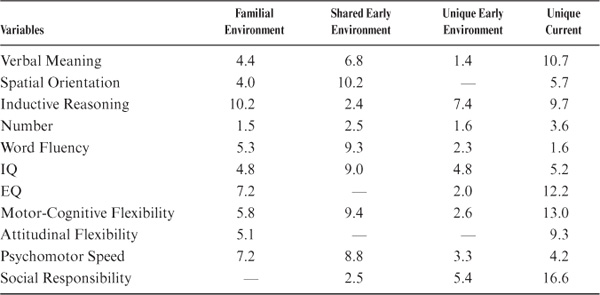

After selecting the optimal regression model, several hierarchical regression analyses then assessed the proportion of variance explained by successive blocks of independent variables. The independent variables were classified into four blocks: Block 1 contains the static familial variables (i.e., parents’ or siblings’ performance on the corresponding cognitive variable, as well as their level of educational attainment). Block 2 includes the significant variables for characterizing the shared early environment (i.e., parents’ or siblings’ perception of the family of origin of the targeted offspring or sibling). Block 3 includes the significant variables characterizing the nonshared early environment (i.e., the offsprings’ or targeted siblings’ perception of their family of origin). Block 4 includes the significant variables characterizing the targeted participants’ perception of their current (nonshared) environment. The proportion of variance accounted for by each block after the first is the increment in R2.

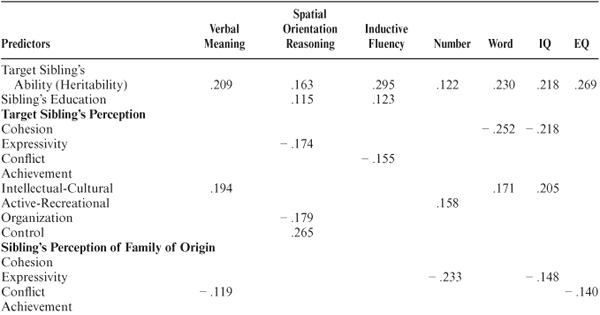

In the parent–offspring data set, significant heritability was found for the five primary mental abilities and the derived summative indices, as well as for Motor-Cognitive Flexibility and Psychomotor Speed. In addition, parental education regressed significantly on adult offspring performance on Spatial Orientation, Inductive Reasoning, and the composite cognitive induces as well as on Motor-Cognitive and Attitudinal Flexibility. However, only one of the regression coefficients for the abilities and one coefficient for the regression of Social Responsibility on the parental perceptions of their current family environment (the estimate of shared environment) were significant. It seems that the time since our adult offspring shared the current family of their parents was simply too long to have the parents’ current environment serve as a surrogate for the early shared environment (see table 17.11).

Nevertheless, there were a number of significant regressions for the offsprings’ perception of the family of origin (the unique experience of their early environment). These regressions, at least for the cognitive abilities, accounted for as much or more variance than the participants’ perception of their current environment. Cohesion related positively to Spatial Orientation and Social Responsibility. Expressivity was negatively related to Verbal Meaning, Spatial Orientation, Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed as well as the indices of Intellectual Ability and Educational Aptitude. Perceived Conflict related positively to Number and negatively to Word Fluency. Achievement Orientation related positively to Number. Intellectual-Cultural Orientation related positively to Verbal Meaning and Social Responsibility. Organization related negatively to Inductive Reasoning. Finally, perceived Control related negatively to Verbal Meaning, Spatial Orientation, and the index of Educational Aptitude.

Significant regressions for the effect of the current environment of the offspring were also found. Cohesion related positively to Word Fluency and the IQ and Educational Aptitude indices, but negatively to Spatial Orientation. Expressivity related positively to Verbal Meaning, Inductive Reasoning, Attitudinal Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed. Conflict related positively to Social Responsibility. Achievement Orientation related positively to Psychomotor Speed, but negatively to Attitudinal Flexibility. Intellectual-Cultural Orientation related positively to Verbal Meaning, Educational Aptitude, Attitudinal Flexibility, Psychomotor Speed, and Social Responsibility. Active-Recreational Orientation related positively to Spatial Orientation. Organization related negatively to the IQ index and Attitudinal Flexibility. Control related positively to Social Responsibility, but negatively to Attitudinal Flexibility.

TABLE 17.11. Regression Coefficients for Parent–Offspring Study

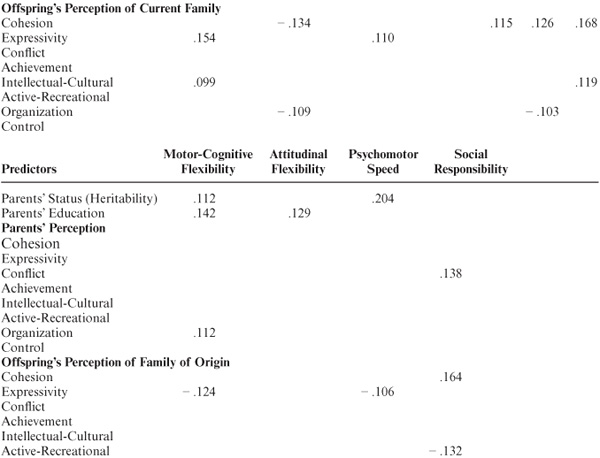

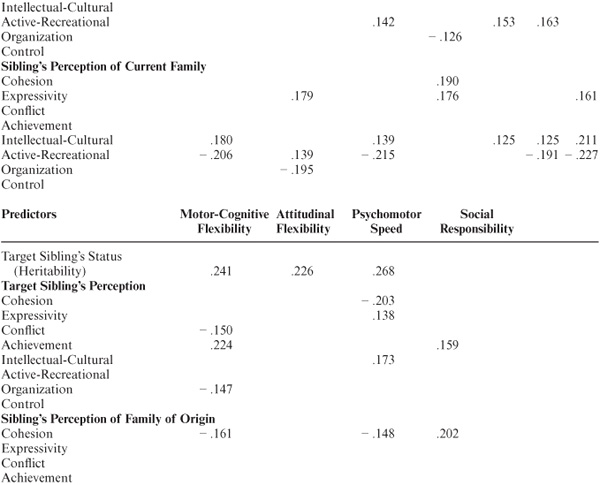

Significant heritabilities were again observed for all primary mental abilities and their composite indices, as well as for Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, Attitudinal Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed (see table 17.12). Siblings’ educational level yielded significant regressions for Spatial Orientation and Inductive Reasoning. Substantial regressions were also found for the shared environment in the family of origin. Cohesion negatively influenced Word Fluency, Intellectual Ability, and Psychomotor Speed. Expressivity related negatively to Verbal Meaning, but positively to Psychomotor Speed. Achievement Orientation related positively to Motor-Cognitive Flexibility and Social Responsibility. Intellectual-Cultural Orientation related positively to Verbal Meaning, Word Fluency, Intellectual Ability, and Motor-Cognitive Flexibility. Active-Recreational Orientation related positively to Number. Organization related negatively to Spatial Orientation and Motor-Cognitive Flexibility. Finally, Control related positively to Spatial Orientation.

Smaller but significant contributions were provided by the siblings’ unique perceptions of the family of origin. These include a positive correlation of Cohesion with Social Responsibility, but a negative correlation with Motor-Cognitive Flexibility and Psychomotor Speed. There was a negative relation between Expressivity and Inductive Reasoning as well as the Index of Intellectual Ability, Conflict related negatively to Verbal Meaning and the measure of Intellectual Aptitude. Active-Recreational Orientation related positively to Inductive Reasoning, Word Fluency, and Intellectual Aptitude as well as to Psychomotor Speed, and Control related negatively to Social Responsibility.

Significant regressions were also found for the influences of perceptions of the current family environment. Here, Cohesion related positively to Number. Expressivity related positively to Verbal Meaning, Inductive Reasoning, Educational Aptitude, Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed. Conflict related negatively to Motor-Cognitive Flexibility. Achievement Orientation related positively to Motor-Cognitive Flexibility and Psychomotor Speed, but negatively to Social Responsibility. Intellectual-Cultural Orientation related positively to Verbal Meaning, Inductive Reasoning, Word Fluency, the composite indices, Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed, but negatively to Social Responsibility. Active-Recreational Orientation related positively to Spatial Orientation and Attitudinal Flexibility, but negatively to Verbal Meaning, Inductive Reasoning, and the composite indices. Organization related negatively to Spatial Orientation, Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, and Attitudinal Flexibility. Control related negatively to Attitudinal Flexibility.

TABLE 17.12. Regression Coefficients for Sibling Study

The critical issue in this analysis, of course, is the determination of the extent to which individual differences in cognitive performance in adulthood can be allocated to familial influences (including heritability) and shared early environment and how much is because of the unique influences of early and current family environments.

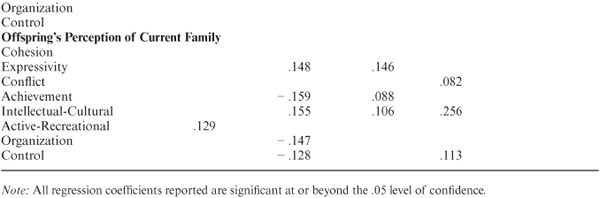

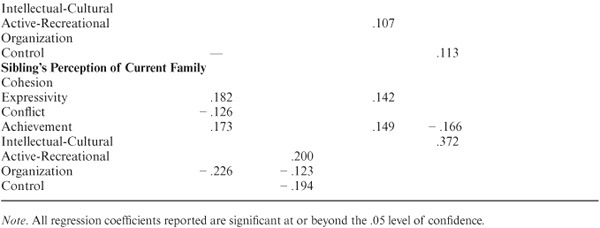

When we disaggregate perceived environmental from static familial influences, we find that the former account for relatively small proportions of variance, ranging from 1.7% for Attitudinal Flexibility to 7.5% for Inductive Reasoning. No such influences can be found for Attitudinal Flexibility and Social Responsibility. Because of the lack of temporal coincidence in the parental ratings for the offspring families of origin, we find only trivial influences for the perceptions of the shared early family environment. Significant, but fairly small, proportions of individual differences in cognition in adulthood are accounted for by the unique offspring perceptions of the family of origin. These range from 1.7% for the Number ability to 9.5% for Verbal Meaning. No effects of the unique early environment are found for Attitudinal Flexibility. Current family environment influences range from 1.2% for Inductive Reasoning to 10.9% for Attitudinal Flexibility. The only dependent variable not significantly affected is the Number ability. Detailed findings are shown in table 17.13.

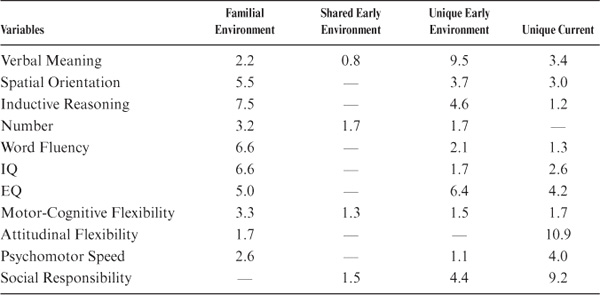

We first note that static familial influences range from zero for Social Responsibility and Motor-Cognitive Flexibility to a high of 10.2% for Inductive Reasoning. Contributions of early shared environment range from zero for Attitudinal Flexibility to 10.2% for Spatial Orientation. Perceptions of the unique early environment range from zero for Attitudinal Flexibility to 7.4% for Inductive Reasoning. Current environment influences range from 1.6% for Word Fluency to 16.6% for Social Responsibility.

TABLE 17.13. Proportion of Variance by Source for Parent–Offspring Study

The total contribution of all family environment sources ranges from a low of 7.7% for Number to a high of 25% for Motor-Cognitive Flexibility. When we consider the joint effect of static familial influences and early shared environment, the proportion of explained individual differences ranges from a low of 2.5% for Social Responsibility to a high of 16% for Psychomotor Speed. For the primary mental abilities, these values are Verbal Meaning 11.2%, Spatial Orientation 14.2%, Number 4%, and Word Fluency 12.6%. Table 17.14 shows the detailed breakdown into the various sources of variance.

Given the assumption that individuals’ perceptions of family environments are reasonable representations of such environments, we find that a significant impact of shared early environment on adult cognitive performance can be demonstrated in sibling but not in parent–offspring dyads. This discrepancy is readily explained by the fact that the parental family perceptions must be measured by inquiring about their current family (which in most cases is the family of origin of the offspring). On the other hand, the siblings’ perception of their family of origin involves retrospection to that time interval mostly shared with the target sibling. By contrast, influences of the unique early environment (involving the participant’s own retrospection) and current environment yielded significant proportions of variance in adult cognitive performance in both the parent–offspring and sibling samples. Findings from these analyses have been replicated in a master’s thesis by Ledermann (2003), utilizing structural equation modeling procedures on a more recent family data set.

TABLE 17.14. Proportion of Variance by Source for Sibling Study

Significant differences in both static familial characteristics and shared early environment estimates between same-gender and cross-gender pairs were again noted (also see chapter 13). Although subsamples were too small to provide stable estimates, heritability estimates were generally higher in same-gender pairs; the effect of shared early environment was greater in cross-gender pairs for most (but not all) variables.

What then were the family environment dimensions that were most salient in predicting adult cognitive performance? As far as the early environment was concerned, there was a clear positive effect of a strong Intellectual-Cultural family orientation. On the other hand, high levels of family Cohesion had a negative effect.

High expressivity estimates from the unique perceptions of the early environment also seemed to have negative effects on several cognitive variables; the unique perception of high Active-Recreational Orientation had a positive impact. By contrast, positive influences on cognitive performance and positive cognitive styles of the current family environment involved primarily high levels of Cohesion, Expressivity, and Intellectual-Cultural Orientation coupled with low levels of family Organization.

This chapter provides information on the similarity of perceptions of family environments of parents and their adult offspring and the similarity in such perceptions of adult siblings reported in adulthood. Perceptions of family environments include the family of origin (i.e., the family setting experienced when study participants lived with their own parents) and with respect to their current family (i.e., their family unit at the time data were collected). These data are then used to compare the impact of heritability and environmental influences on cognitive performance by examining correlations between parent–offspring and sibling dyads to the shared and unique effects of childhood and current family environments.

Different versions of the Moos Family Environment Scale were constructed to assess the perceptions of our study participants with respect to their family of origin and their current family, as well as allow participants to define their current family as those individuals with whom they interact most closely.

We conclude that there is a clear differentiation for parents, offspring, and siblings in the perceived level of all family dimensions between the family of origin and the current family. The current families not only are seen as more cohesive and expressive but also are characterized by more conflict than was true for their families of origin. In addition, there is the perception of lower levels of perceived Control, family Organization, and Achievement Orientation.

Siblings share a great many perceptions of their family of origin, but not of their current families. But in spite of the lack of similarity of current family perceptions, the best predictor of the current family environment is the corresponding perception of their family of origin.

Evidence supporting the continuity of family values and behaviors is provided by substantial correlations between the parents’ description of their current family environment and their offsprings’ description of their family of origin. These relationships were strongest for the perceptions of Achievement, Intellectual-Cultural, and Active-Recreational Orientation and for family Organization.

Perceived family environment and the magnitude of similarity across generations differ by gender pairing and by dimensions. Strongest relationships are found within mother–daughter and sister–sister pairings. Nevertheless, intensity of contact between parents and offspring has virtually no impact on the similarity of reported family environments.

With respect to the impact of shared early environment on adult cognitive performance, we demonstrate such a relationship in sibling, but not in parent–offspring, dyads. Significant differences in both static familial characteristics and shared early environment estimates between same-gender and cross-gender pairs are also noted. Heritability estimates are generally higher in same-gender pairs; the effect of shared early environment is greater in cross-gender pairs for most variables.

The family environment dimensions most salient in predicting adult cognitive performance are as follows: Shared perceptions of the early environment revealed a positive effect of a strong Intellectual-Cultural family orientation, but a negative effect of high family Cohesion. On the other hand, unique perceptions of the early environment implicated positive effects of an Active-Recreational Orientation; high Expressivity seemed to have negative effects on several cognitive variables. Current family environments that had positive influences on cognitive performance and cognitive styles were characterized by high levels of Cohesion, Expressivity, and Intellectual Cultural Orientation as well as low levels of family Organization.