15

Seaweed and Microalgae

Seaweed: Nicholas A. Paul and Microalgae: Michael Borowitzka

15.1 General Introduction

Seaweed (macroalgae) and microalgae differ markedly in morphology and life cycles. Therefore the methods used for their culture and the purposes for which they are cultured are, for the most part, extremely different. Because of these attributes, the two kinds of cultured algae will be treated separately in this chapter.

15.2 Seaweeds

15.2.1 Introduction

15.2.1.1 World Production

Seaweeds are cultured throughout the world. More than 25 countries contribute to over 20 commercial seaweeds with diverse taxonomy (Table 15.1) and diverse uses (Table 15.2). Total world seaweed production from aquaculture was estimated at 27.3 million tonnes (t) and worth USD 5 637 million in 2014 (Table 15.1). Since the turn of the century, seaweed production volume from aquaculture has grown by 8% p.a., and at ~11% per annum over the 5 years to 2014, yet the relative value of the product (USD/t) has continued to decline (Figure 15.1). There are many factors involved in these broader trends relating to the relative contributions of aquaculture versus capture fisheries, taxonomic differences, geographic trends, scalability of culture techniques and the degree of processing required to deliver an export product. Each will be discussed in the following sections.

Table 15.1 Aquaculture production data for seaweed in 2014. Volume data in tonnes (t) and value data in US dollars (USD). USD/t is derived from the previous columns. Production of the main taxonomic groups are extracted from FAO Fishstat.

Source: FAO Fishstat Global aquaculture production – Quantity and Value dataset; Accessed 2016.

| Main taxa and common names | Volume (2014, t) | Value (2014; USD) | USD/t |

| Brown seaweed | 9 763 262 | 1 531 412 | 157 |

| Saccharina (Japanese kelp, kombu; previously Laminaria) | 7 210 286 | 346 958 | 48# |

| Undaria (wakame) | 2 358 597 | 1 060 281 | 450 |

| Sargassum (fusiforme Sargassum, hijiki) | 175 430 | 80 698 | 460 |

| Red seaweed | 16 523 871 | 3 825 807 | 232 |

| Kappaphycus/Eucheuma (cottonii, spinosum, elkhorn sea moss, Zanzibar weed) | 10 965 548 | 1 856 643 | 169 |

| Gracilaria | 3 752 172 | 1 024 071 | 273 |

| Porphyra/Pyropia (nori, laver) | 1 806 151 | 945 093 | 523 |

| Green seaweed | 13 807 | 8180 | 592 |

| Ulva/Monostroma (Aosa, Ao‐nori, sea lettuce, green laver) | 7055 | 4828 | 684 |

| Codium (fragile Codium, dead man's fingers) | 5550 | 2062 | 372 |

| Caulerpa (sea grapes, green caviar, umi budo, lawi lawi, nama) | 1199 | 1290 | 1076 |

Note that the sum of production data for brown, green and red seaweed does not sum to total production data (as reported in Table 15.3) as the latter includes miscellanous aquatic plants not elsewhere included (nei) in the convention of FAO reporting.

# ‐ possible inaccurate value.

Table 15.2 Some uses and products of seaweeds. The gelling properties of processed material from seaweeds are used as food additives (for dairy products, sweets, processed meats and alcohol brewing) and in a variety of industrial and commercial applications (e.g., in paints, adhesives, bacterial agar, shampoo, toothpaste). Seaweed genera listed alphabetically, not in order of importance. Seaweed taxonomic groupings indicated: Green – G, Red – R, Brown – B.

| Use/product | Seaweed |

| Dried for human consumption | Eucheuma (R), Fucus (B), Gelidium (R), Gracilaria (R), Porphyra/Pyropia (R), Saccharina (B), Sargassum (B), Ulva/Enteromorpha (G), Undaria (B) |

| Fresh for human consumption | Caulerpa (G), Eucheuma spinosum (R), Gracilaria (R), Porphyra (R), Ulva (G) |

| Medicinal uses | Ascophyllum (B, muscle‐related problems), Asparagopsis (R, antifungal, antibacterial), Caulerpa (G, hypertension, antifungal), Chondrus (R, blood anticoagulants), Dictyota (B, antifungal, antibacterial), Laminaria (B, iodine deficiency), Sargassum and Ulva (vermicides), Undaria (B, neutraceuticals) |

| Fertilisers or soil additives | Ascophyllum (B), Fucus (B), Macrocystis (B), Laminaria (B) Sargassum (B), |

| Production of gelling ‘hydrocolloids’ | |

| Agar production | Gelidium (R), Gracilaria (R) |

| Carrageenan production | Chondrus (R), Eucheuma (R), Kappaphycus (R) |

| Alginate production | Ascophyllum (B), Fucus (B), Saccharina (B), Macrocystis (B), Sargassum (B) |

Figure 15.1 Global production of seaweeds from aquaculture and its relative value (USD/t).

Source: Data extracted from FAO Fishstat (Global Aquaculture Production – Quantity and Value dataset; Accessed 2016)

Because seaweed production from fisheries constituted only 5% of global production in 2014 (Table 15.3), the seaweed sector remains the most aquaculture‐orientated of all marine and freshwater sectors. This is reflected in the relatively small amount of wild‐harvest seaweed in 2014, for example, that from Chile (>400 000 t; kelp and red seaweed), Norway (154 000 t of kelp), Japan (67 000 t; mostly kelp) and Indonesia (70 500 t of red seaweed; Figure 15.2). Reducing the pressure from wild‐harvest fisheries is essential as some stocks have clearly been over‐harvested, particularly the red seaweed Gracilaria from Chile, which had yields of >100 000 t per annum in the early 1980s followed by low annual yields (<10 000 t) for most of the 1990s (although these have stabilised in recent years, ~30 000–45 000 t).

Table 15.3 Global production (t = tonnes) of seaweeds from aquaculture and wild‐harvest fisheries.

Source: Data from FAO Fishstat (Global aquaculture production and Global capture production; Accessed 2016).

| Category | 2014 |

| Aquaculture production | 27 307 000 |

| Aquaculture value | USD 5637 million |

| Fisheries production2 | 1 184 000 |

| Proportion aquaculture production | 96% |

Figure 15.2 Eastern Indonesia is the main production area of tropical red seaweed for carrageenan. Here red seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) is harvested for drying with some pieces retained for reseeding. The green colour of this red seaweed is due to accessory pigments.

Source: Reproduced with permission of FAO Aquaculture photo library/M. Ledo.

Compared to other sectors, seaweed biomass constituted 28% of total world aquaculture production in 2014 (globally 101 130 000 t), and slightly under 3% by value (globally USD 106 020 million; section 1.3, Figure 1.7). This reflects a lower value per unit weight compared with most other classes of aquaculture product. However, low product values are offset by a predominantly extensive, open form of aquaculture, with correspondingly low start‐up and operating costs compared to other commodities. There has been a recent shift towards the cultivation of more red seaweeds for hydrocolloid production, including the more valuable Gracilaria taxa for agar production for which the export value can be > USD 10 000/t (Figure 15.3), while ‘Agar‐agar’ ranges from USD 7 500 – 13 500/t. Nori (laver) and niche dried products for human consumption, such as ‘hijiki’ (Sargassum) are the two other high‐value export products, whereas kombu (kelp) and wakame (Undaria) are lower value commodities (USD 3 000–4 000/t) and red seaweed, traded as raw material, has the lowest export value (~USD 1 000/t). New seaweed ventures should continue to occupy niches in the supply of high‐value fresh seafood (in contrast to the focus on dried edible seaweeds in the previous millennium), for functional foods and nutraceuticals, and in the isolation of seaweed natural products for cosmeticeutical or pharmaceutical applications (Table 15.2).

Figure 15.3 Recent export value for dried and processed seaweed from different taxonomic groups.

Source: Data from FAO 2013.

Production of red seaweeds (Rhodophyta) has increased rapidly in the five years to 2014 (Figure 15.4), now comprising more than 60% of reported world seaweed production. The shift from brown to red seaweed has been driven by meteoric increases in production from the tropical nation of Indonesia, from 2 million t in 2007 to 10 million t in 2014, and a continuing stable contribution from the Philippines of 1.5 million t in 2014. The major species in culture in Indonesia and the Philippines are hydrocolloid‐producing algae, specifically Eucheuma, Kappaphycus and Gracilaria species.

Figure 15.4 Recent world production of the three seaweed taxa red, brown and green algae.

Source: Data from FAO 2015.

Hydrocolloids (or phycocolloids; ‘phyco’ pertaining to algae) refer to emulsifying chemicals or gums including agar and carrageenan harvested from red seaweed, and also to alginate extracted from brown seaweeds (Table 15.2). Red seaweed hydrocolloids provide structural support to the cells, through the variety of cross‐links provided by components of these complex sugars. The main types of polysaccharides involved are iota‐carrageenan, kappa‐carrageenan and agar‐agar. The binding strengths (relating to product quality/end use) and the degree of processing determine price, but traders can expect to receive around USD 1 000/t for dried, raw seaweed and over USD 10 000/t for processed or refined product (Figure 15.3). However, short‐term prices fluctuate substantially in response to supply chain issues and demand. This is seen most clearly in the long‐term commodity data from the Philippines for production of Kappaphycus/Eucheuma for export as dried seaweed product (Figure 15.5). It highlights a worrying trend in demand for seaweeds that are processed into carrageenan, especially for the small‐holder farmers that depend on this crop for their livelihoods. The swings in commodity value for this raw material contrasts to recent trends in the value of processed ‘agar‐agar’, which continues to rise (Figure 15.3). Before the colloid boom, ‘laver’ or ‘nori’ (Porphyra/Pyropia species used in sushi) was the main type of red seaweed under cultivation. Nori production is still significant at 1.8 million t in 2007 (USD 945 million), predominantly (>60%) from China with contributions from Japan and the Republic of Korea. Most developing nations produce red seaweeds (predominantly Eucheuma and Kappaphycus) owing to the ease of cultivation (see section 15.2.4) and the notable absence of kelp and nori from tropical waters.

Figure 15.5 Long‐term trends for the export value of dried red seaweed from the Philippines. This product is a traded as a raw material prior to the extraction of carrageenan.

Source: Data from FAO 2015.

Brown seaweeds (Phaeophyceae) were historically, up until 2007, the major group of cultured seaweeds. The most widely cultured species of brown seaweed is the Japanese kelp Saccharina japonica (‘kombu’, previously classified as Laminaria japonica) at 7.2 million t, which made up two‐thirds of the total cultured brown algae in 2014. Dried Japanese kelp is used directly as food but is also extracted for alginate, mannitol and iodine. Undaria pinnatifida (‘wakame’) accounted for most of the remaining production (2.4 million t), followed by Sargassum fusiforme (‘hijiki’, 0.17 million t). Reflecting the tradition of seaweed culture in Asia, by far the largest producer of brown algae (kombu, wakame and Sargassum spp.) is China, with 90% of global production in 2014, with the remainder primarily produced in the Republic of Korea (7%). A variety of other countries produce small amounts of brown algae including Japan, Russia, Denmark, Ireland and Spain.

Green seaweeds (Chlorophyta) comprise <0.1% of total production and are the only group of seaweeds for which production has declined in the five years since 2009 (Figure 15.3). Some green seaweeds (including Ulva species, sea lettuce and Monostroma) are used as dried‐food additives, and some more valuable species have small, niche markets (e.g., Caulerpa lentillifera and C. racemosa or ‘sea grapes’ are cultivated in the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Japanese sub‐tropical island of Okinawa). However, global production databases (e.g., FAO Fishstat) may not necessarily provide the whole picture for more recent innovations and nascent growth areas. For instance, Ulva is an exceptional seaweed for integrated (animal–plant) aquaculture (see section 15.2.4.5) based on its growth rates, nitrogen assimilation, life cycle and ease of culture. Commercial‐scale versions of these integrated systems have recently emerged (examples in South Africa and Australia) and may lead to more production of green seaweed as feedstock for marine herbivores in a similar manner to that in which microalgae are essential as live feeds in aquaculture nutrition.

15.2.1.2 Morphology and Habitats

Seaweeds come in a diverse array of shapes (from filaments to broad sheet‐like structures) and sizes (encrusting turfs to >20 m–high stands of giant kelp Macrocystis). The basic morphology of kelps (such as kombu and wakame) includes a discrete attachment organ or holdfast, with a stem‐like stipe and a leaf‐like blade. The thallus (whole plant) is often differentiated into branches arising from the stipe, leaf‐like fronds and flotation structures. Cultivated red seaweeds (e.g., Eucheuma, Kappaphycus and Gracilaria) are far less differentiated than kelps. These seaweeds are propogated vegetatively from thallus fragments and are physically secured to ropes. Other seaweeds have little obvious differentiation, comprising only leaf‐like thalli with microscopic holdfasts (e.g., Porphyra and Ulva, one‐ and two‐cell layers thick, respectively). Seaweeds are generally benthic in nature and are restricted to solid substrata such as rock; however, many seaweeds will survive and grow when free‐floating or suspended in the water column. There are also some fundamental differences to higher plants, the most obvious being limited or no internal transfer of materials within individuals. This means that seaweeds absorb nutrients over their entire surface.

In many ways seaweeds are excellent organisms for aquaculture. Seaweeds are robust and often inhabit the intertidal zone where they are exposed to the air at low tide and subject to desiccation, and deal with daily or seasonal fluctuations in temperature and salinity. The two fundamental constraints for seaweed physiology, and therefore biomass productivity, are light and nutrients. Seaweeds require light for photosynthesis. Light quality (spectrum) and quantity changes with depth, and seaweeds adapt through changes in the amount and types of both primary (chlorophyll) and accessory pigments. Nutrients (especially nitrogen and phosphorus) are at times limiting in nature, and to cope with fluctuation some seaweeds store nutrients opportunistically (known as ‘luxury’ uptake). For practical reasons the shallow subtidal and intertidal regions support most seaweed‐farming activity, and farms situated close to anthropogenic sources of nutrients may even benefit from these ‘free’ resources.

15.2.2 Reproduction and Life Cycles

The successful adaptation of seaweeds to aquaculture requires an understanding of their reproductive strategies, which can be rather complex. In brief, reproduction may be asexual (vegetative fragmentation) or sexual, and many species have a life cycle characterised by alternation of free‐living generations (diploid ↔ haploid). These species have a diploid (2n) spore‐producing stage and a haploid (1n) gametophyte stage. The gametophytes can be dioceous (separate sexes) or monoecious (both male and female on the one individual). To add another level of complexity, the different stages may be morphologically different (hetermorphic alternation of generations) or may be identical but with different ploidy (isomorphic alternation). For the latter it is important to know which stage one is working on, as different stages have different cues for reproduction. Fortunately, while reproductive structures are small, they can be identified with microscopy. For most seaweeds, reproduction is controlled by environmental factors such as water temperature, day length and light quality. Some species have winter peaks in biomass, others in summer (in most cases peak biomass in nature correlates with reproduction). A greater understanding and control of the environmental influence on reproduction is essential to refining seaweed cultivation, in a similar way that closed life cycles and photothermal control of reproduction in finfish fulfils year‐round production.

The following sections describe the reproduction and the life cycles of three important culture genera, Saccharina, Porphyra and Ulva, representing the three major culture groups, brown, red and green seaweeds, respectively. The predominant culture technique for Eucheuma, Kappaphycus and Gracilaria is asexual (vegetative) fragmentation, even though sexual reproduction and alternation of generations is possible. Vegetative techniques for these red algae are described in section 15.2.4.

15.2.2.1 Reproduction in Saccharina/Laminaria

The mature diploid (2n) sporophyte of Saccharina/Laminaria species bear specialised reproductive organs, called sori, which undergo meiotic cell division to produce haploid (n) zoospores. The motile zoospores settle on suitable substrata and develop into microscopic male or female filamentous gametophytes. Mature female gametophytes release eggs that secrete chemicals to stimulate the release of sperm from the male gametophyte. Motile sperm cells are attracted to the eggs chemotactically and the diploid zygote develops into a mature sporophyte. In many species of brown seaweed, gamete production is seasonal and in temperate environments the deployment of juvenile sporophytes are timed to coincide with optimal growth conditions in warmer months.

15.2.2.2 Reproduction in Porphyra

The life history of most red algae is more complex than brown seaweeds as it involves an extra stage in the life cycle (the carposporophyte). Male and female gametes develop within the vegetative cells of the haploid (n) gametophyte stage. Spermatangia are formed from mitotic divisions in the protoplast of the male gametophyte, and the female gametes are formed as carpogonium cells on the female gametophyte. Male gametes are non‐motile (non‐flagellated), meaning that red seaweeds have to rely on wave and current action to carry the sperm to the carpogonium. After fertilisation the diploid cell grows into a distinct stage, the carposporophyte that is actually parasitic on the female gametophyte and is contained within a visible structure known as the cystocarp. The function of this distinct stage is to multiply the genetic material from a single fertilisation event into numerous carpospores (2n). The carposporohyte releases carpospores and they settle onto appropriate substrata (e.g., scallop shells for Porphyra) to give rise to many minute filamentous sporophytes (2n), each known as a conchocelis for Porphyra. The sporophytes release asexually generated spores (n) (called conchospores in Porphyra). The conchospores settle and grow into new gametophytes (= edible stage of Porphyra) which, in time, mature and close the life cycle. In some species of Rhodophyta, including Porphyra species, neutral spores (or monospores, produced by mitosis rather than meiosis) are released from the gametophyte at certain times of the year, creating additional harvests from a single fertilisation event.

The culture of Porphyra initially involves seeding carpospores onto mollusc (e.g., oyster) shells. ‘Seeding’ of the cultivation nets with conchospores (produced meiotically by the conchocelis) is achieved by placing the nets in cultivation tanks containing the conchocelis‐infested shells. The water is agitated in the tanks to enhance adhesion of the non‐motile conchospores to the nets. These nets can be set in the ocean or even frozen to ensure that deployment occurs under optimal conditions. The conchospores develop into the macroscopic gametophyte generation, which is harvested for consumption.

15.2.2.3 Reproduction in Ulva

The life histories of the Chlorophyta are diverse. Some species, including Ulva, undergo an alternation of isomorphic generations. That is, the gametophyte and sporophyte are indistinguishable except for their microscopic reproductive structures. Their diploid (2n) sporophyte stage produces haploid zoospores by meiosis from the sporangia of the thallus. These spores germinate into male or female haploid gametophytes. Flagellate gametangia produced from the parent gametophyte are released and, upon fusion of opposing gametes, a diploid zygote forms that develops into the mature sporophyte.

15.2.3 Characteristics of Seaweed Culture

15.2.3.1 Seaweed Culture Distinguished from Agriculture

There are some important characteristics that distinguish seaweed culture from agriculture.

- Macroalgae do not need a special absorption organ, as nutrients in solution can be absorbed by any part of the plant. The holdfast is sufficient to anchor the algae in place. However, the ocean is in constant motion and, as the sea level varies with tide, the amount of light reaching algae on fixed substrates varies. Use of floating rafts, where the depth of cultivation is constant, addresses this problem; raft‐based culture also allows the culture depth to be changed as required. Similarly, tank‐based culture using suspended (tumbling) biomass allows light to be maintained at an optimal level through altering stock density and light penetration.

- Seaweeds reproduce using spores that are released into open water. The spores cannot be kept alive for a long time after discharge and suitable substrata must be provided close to the parent.

- Most cultivated seaweeds are attached or secured to substrata. In general, seaweeds grow naturally on stable substrata that are able to withstand high wave action and receive adequate light. In the early days of seaweed culture, rocks and stones were regarded as excellent substrates for cultivation. However, their limited surface area, large size and immobility, as well as the need to employ divers for harvesting the seaweeds, meant that alternatives were sought. For example, the Japanese kelp (Saccharina japonica) was introduced to China in the 1920s; however, the coastline lacks suitable natural substrata. Large‐scale production was made possible using floating rafts (Tseng, 1981), and Chinese production of this species is now many times greater than production in Japan. Land‐based culture of seaweed (predominantly of red and green seaweeds) has now evolved to free‐living cultivation of selected seaweeds that do not need substrata.

- Unlike the application of fertiliser to land plants through the soil, the application of fertiliser to seaweeds is very difficult given the dynamic nature of the ocean. Fertiliser applied to seaweed in the ocean will rapidly disperse, making seaweed culture too costly and creating the potential to pollute the coastal environment. Porous containers for fertiliser application have been developed in China, where losses of fertiliser to the open sea are minimised. For large areas cultivating large quick‐growing seaweeds, such as the Japanese kelp, the required fertiliser (e.g., ammonium nitrate) can be sprayed onto the seaweed at low tide. Land‐based operations, however, allow tight control of the nutrient concentrations available to seaweeds.

15.2.3.2 Problems in Common with Agriculture

There are also several problems in common with agriculture. Temperature is one of the most important factors in seaweed culture. Optimal and minimum temperatures for growth and development may differ, sometimes even within the same species depending on the phase of the life history and growth stage. For example, the sporophyte and gametophyte of nori Porphyra tenera have different optimal water temperatures. Successful culture requires information about the requirements of all stages of seaweed development and growth, particularly for managing reproduction.

Like agriculture, seaweed culture also has a problem from weeds or nuisance algae. In kelp culture in China, for example, ropes covered with spores are placed in the ocean for grow‐out in autumn (October). Spores of nuisance algae such as species of Ectocarpus and Ulva may quickly adhere to ropes and germinate, overgrowing spores and juvenile gametophytes. Therefore gametophytes are not exposed to light until December, only after the nuisance alga matures and degrades. However, this can delay development for about two months. Several methods are used to combat nuisance algae. These include the collection of spores in early summer (section 15.2.4.4 ‘tank culture’) and the cultivation of spore‐covered ropes in glasshouses with artificially cooled filtered seawater. The young sporelings (called ‘summer sporelings’) can then be put to sea in autumn, when they are already a few centimetres tall. At this size they can out‐compete nuisance algae.

The nuisance problem in the cultivation of red algae, Porphyra species, is more complicated. The predominant weed algae are species of Monostroma, Ulva and Urospora. Some aspects of fouling by nuisance algae can be controlled. For example, in the seeding process, the attached conchospores are packed densely so that there is very little space for the nuisance spores to attach. At harvesting, large thalli are selectively collected but small thalli are left intact to limit the availability of space to nuisance algae. Another common way to control the nuisance algae is to raise the nets and expose them to direct sunlight. Nuisance algae are generally more susceptible to desiccation than Porphyra, and with the correct amount of exposure it can be killed, leaving the Porphyra intact.

15.2.4 Culture Methods

Commercial cultivation of seaweeds has evolved from minor interventions to enhance the natural process, through to advanced controls with tank‐based cultivation for either part or the entirety of culture. Successful commercial cultivation depends on good culture techniques that may differ to some extent according to location. For example, in the 1950s when red algae cultivation began in China, established Japanese techniques were unsuccessful because of the much larger tidal range in China. Techniques were successfully adapted to a semi‐floating method of cultivation, which gave much better results than the traditional Japanese method.

There are now four major types of seaweed cultivation:

- long‐line culture;

- net culture;

- pond culture; and

- tank culture.

15.2.4.1 Long‐Line Culture

Long‐line culture methods (Figure 15.6) are the usual method for commercial cultivation of kelps (Saccharina and Undaria species) in China but have also been extensively applied to shallow water cultivation of red seaweeds (Eucheuma, Kappaphycus and Gracilaria) in tropical regions. This type of culture technique is responsible for more than 95% of global seaweed production. Typical productivities for annual production of Saccharina japonica on long‐lines are between 80 and 120 t/ha (Fei, 2004).

Figure 15.6 Long‐line cultivating kelp in China. Note that each cultivation rope bearing kelp (1) is attached to a hanging rope (2), which is attached to the long‐line (3), and its lower end is tied to a weight (4). The anchor ropes (5) are twice as long as the depth under the long‐line and they are anchored to the sea bottom using wooden stakes (6).

Source: Tseng 1981. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley & Sons.

The long‐line for kelp cultivation is composed of a 30‐ to 60 m‐long synthetic fibre rope, secured by two anchor ropes. The long‐line is supported by several buoys (15–20 cm in diameter). Attached to the long‐line is a series of hanging ropes (or ‘droppers’) to which the cultivation ropes (each about 1.2 m long, seeded with kelp) are attached with a small stone weight on the end. The distance between two adjacent cultivation ropes is 70–140 cm. Each cultivation rope holds about 30 plants, and the distance between two adjacent long‐lines is about 6–7 m. This means that between 150 000 and 300 000 kelp plants can be cultivated in 1 ha, corresponding to an areal density of 15–30 individuals/m.

During cultivation there is a difference in growth rate between the upper and lower plants on the same rope. To counteract this, cultivation ropes are regularly inverted. The difference in growth rates can also be minimised by tying adjacent ropes together so that they become oriented more horizontally. Using these methods, the production level and product quality are greatly improved (Tseng, 1981).

Several other kinds of seaweed are cultivated by the long‐line method, including seaweeds that propagate asexually through fragments of thalli. These include Eucheuma and Kappaphycus species, which are cultured vegetatively by attaching pieces to a long‐line (Figure 15.7) which may be suspended (using floats) or attached to supports driven into the substrate (for the latter the lines are typically shorter, 10–20 m, as they must be handled manually (Figure 5.3). Seedstock are selected (thick and sturdy portions without epiphytes) and tied to the line with a ribbon or rafia. This method is labour intensive and may result in loss of seaweed as a result of improper ties and wave action. However, it is the main process in many developing tropical nations where labour remains relatively cheap. In these nations similar problems may occur with nuisance algae as well as herbivores present on the reef flats. These issues can be managed through early harvesting (before known seasons of intense herbivory) or immediately subsequent to the identification of nuisance algae attached to thalli. Any ‘fouled’ thalli should not be used as seedstock but can still be suitable for processing into industrial hydrocolloids.

Figure 15.7 A woman and girl attach pieces of seaweed to a long‐line for subsequent cultivation in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr P. Edwards, AIT.

15.2.4.2 Net Culture

Open water long‐line systems are primarily used to cultivate large brown algae with zoospores and red seaweed from fragments, but net raft culture is better suited for the culture of small and medium‐sized red algae with non‐motile spores. The most established seaweed cultivated by the net raft method is purple laver/nori (Porphyra/Pyropia species). Annual productivities in China for nori using net culture are 30–60 t/ha (Fei, 2004).

Nets are first seeded in tanks containing the shells with the conchocelis. The tank cultures are monitored to determine the progress of conchospore formation from the shells. When the number of spores discharged reaches approximately 50 000 spores per shell per day, preparations are made for seeding the nets. Light intensity on the surface of the tank is increased and the water is agitated. When spore discharge reaches 100 000 spores per shell per day, formal seeding begins, and net rafts are placed in the tanks. The greatest discharge of spores typically occurs mid‐morning, generating a minimum density of 3–5 spores/mm2. The net rafts are then taken to the field for cultivation.

There are three variations to net cultivation from fixed height in shallow water, to semi‐floating and free‐floating methods. In the first, nets are fastened to pillars (vertical supports) at a defined level within the tidal range (Figure 15.8). The semi‐floating method is particularly good for cultivation of intertidal seaweed, as at high tide the net floats on the water, maximising the light available to the seaweed. Sporelings appear earlier and grow better in semi‐floating systems, sometimes doubling production compared to fixed‐height methods. The floating net method is used for production of purple laver/nori in deep‐water subtidal areas. The floating nets, made of synthetic fibres, are 60 m long and 180 cm broad. They have long anchor ropes so that nets maintain their position on the ocean surface regardless of tidal height, which is an important aspect to the culture of the niche product purple nori, providing consistent conditions to sustain its unique colour. This principle is similar to the long‐lines used in the cultivation of kelps (Figure 15.6).

Figure 15.8 Three methods of net raft seaweed culture practised in China for Porphyra. (a) Fixed type of the pillar method; (b) semi‐floating method; and (c) floating method. Note the short legs of the semi‐floating nets.

Source: Tseng 1981. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley & Sons.

15.2.4.3 Pond Culture

There are some seaweeds, such as Gracilaria tenuistipitata, that grow well in still ponds. In many instances seaweed cultivation in ponds has been opportunistic in using areas previously used for other aquaculture species in Southeast Asia. Sometimes seaweed may be cultivated between harvests in a similar way that agricultural cropping areas lay fallow. However, ponds do not provide optimal conditions for cultivation because of low water motion and only certain species thrive in these conditions (e.g., some red seaweeds and also nuisance species of green tide algae).

Pond cultivation of G. tenuistipitata var. liui in Taiwan yielded, on average, 9 t of Gracilaria and 6.3 t/ha of grass shrimp and crab (Shang, 1976). Gracilaria grows most rapidly in waters of about 25‰ salinity and at a temperature of 20–25 °C. Water depth is managed to provide optimal light throughout the year, shallower (20–30 cm) during spring to early summer (March–June), and deeper (60–80 cm) later in summer with peak irradiance. Fragments of Gracilaria are seeded in spring (April) at a density of 5000 kg/ha and strewn evenly. Harvesting by hand or scoop net takes place every 10 days during summer and autumn (June–November) to maintain optimal stocking density and growth. Harvested plants are washed and sun‐dried, before processing into agar. Similar systems of coastal ponds are used for Gracilaria culture in South Sulawesi (Takalar region), Indonesia, although it is notable that farmers in this region have also diversified to include long‐line culture of Gracilaria off the coast, fetching a price two to three times more than that of pond cultured biomass.

15.2.4.4 Tank Culture

Tank culture can be divided into two methods: partial and complete culture. Indoor tanks are often used to cultivate juvenile seaweeds, especially those with a biphasic life history in which one phase is microscopic, for example the gametophytic phase of kelps and the conchocelis phase of nori (section 15.2.2.2). These juveniles are then seeded into the ocean. However, if the seaweed is a valuable product (e.g., for pharmaceutical or premium food products), returns may justify continued culture in tanks such as those for Caulerpa lentillifera (green caviar) in Japan and Chondrus crispus in Canada. Intensive tank systems have markedly different operational constraints to the extensive forms of cultivation previously discussed.

Partial Tank Cultivation

In the commercial cultivation of kelp, juveniles are produced in tanks before seeding. The parent fronds with noticeably abundant sori (reproductive structures) are cleaned and hung in the air for several hours to induce artificially (by stress) the release of spores. When these fronds are placed in seawater, the pressure resulting from the quick absorption of water breaks the sporangial walls and liberates large masses of zoospores (n). Spore‐collectors (frames with cords) are placed in the spore water and the actively swimming zoospores soon adhere to the collectors to complete the seeding process. The seeded frames may be kept in shallow indoor tanks containing seawater previously cooled to 8–10 °C and enriched with nutrients. The seeded frames remain in the cool house until autumn, when the juvenile sporophytes are about 1–2 cm high. At this time, when the ambient seawater temperature has dropped to about 20 °C, the juveniles are transferred to the farm. The production of juveniles can sometimes operate as a distinct commercial service, as in China where seed is sold to kelp farmers who cultivate these seed at their separate sites (Tseng, 1981).

The conchocelis or sporophyte phase of nori is also microscopic and cultivated in indoor tanks in which culture nets are seeded (see section 15.2.4.2). The tanks vary considerably in size, but they are always shallow (20–30 cm deep) containing clean water (filtered and/or subject to sedimentation in the dark) to which nutrients are added. Light intensity is controlled by a series of screens to provide optimal growth for conchocelis, which varies as a function of the number of conchospores per unit area.

Complete Tank Cultivation

Several seaweeds (e.g., Chondrus crispus and species of Enteromorpha, Gracilaria, Porphyra and Caulerpa) are cultured for direct human consumption in land‐based systems in indoor or outdoor tanks. Other high‐value species of seaweeds, such as targets for nutraceutical or cosmeceutical applications, may also offset the high cost of tank aquaculture. Factors such as irradiance, pH, use of fertilisers and availability of carbon dioxide are of critical importance in such systems (Hafting et al., 2015). However, these variables are interrelated and influenced by flow rates and stocking density. Pumping is continuous, and flow is often high, with exchanges of at least two tank volumes per hour.

Areal (per m2) productivity is paramount for land‐based tank cultivation. Very high annual productivities (e.g., >100 g dry weight/day) are possible for some systems, when the appropriate balance of resources is supplied (see, for example, Mata et al. 2010), but values of ~20 g dry weight/m2/day are more realistic. Once the saturation of nutrients and carbon is ensured, light becomes the major driving force behind productivity and is thus the most important management consideration. Light changes substantially throughout the year in temperate areas and equipment such as light data loggers (measuring photosynthetically active radiation, 400‐ to 700 nm wavelengths) and pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorescence can be used in tandem to ensure that optimal light conditions are maintained under changing conditions. The control over environmental conditions also allows tank aquaculture systems to influence the competition with nuisance species of algae. This can be done by maintaining a high stocking density (2–5 g fresh weight/L or >1 kg fresh weight/m2) or through pulse feeding of nutrients at night time for species capable of luxury uptake.

15.2.4.5 Bioremediation, Polyculture and Integrated Systems

Bioremediation, in the context of aquaculture, refers to the management of dissolved and particulate wastes from intensive aquaculture operations. In this respect, integrated aquaculture is based on the principle of waste utilisation to manage water quality and/or create additional products. Effluent water leaving fish farms contains high levels of nitrogen excreted by fish into the water. It has been estimated that 16% of the total nitrogen input to fish farms (primarily as protein in feed) is excreted as dissolved inorganic nitrogen. The environmental impacts of aquaculture effluents, such as eutrophication, are discussed in Chapter 4. Furthermore, the inadequate conversion of costly protein into fish biomass provides a financial incentive to limit effluent nutrients. One approach to minimising environmental impacts of aquaculture is to use seaweeds to remove dissolved nitrogen from aquaculture effluent (bioremediation). This has the added advantage of diversification (i.e., a second crop) through development of such systems (Chopin and Yarish, 1999). Polyculture is perhaps the crudest form of integrated aquaculture in which multiple species are cultured together (e.g., seaweed cultured in the same tank as a herbivore).

Several studies propose that integrated culture of fish and seaweeds (e.g., Saccharina and Porphyra) can be successful in open water systems (Petrell and Alie, 1996; Chopin and Yarish, 1999). The position of the seaweeds relative to the fish cages is important in determining the concentration of dissolved nitrogen available to the seaweeds, which, in turn, influences growth rates. However, there are also several practical considerations for an operation to overcome before engaging in integrated aquaculture. For example, there is the potential that mass production of seaweed required to ameliorate nutrients around cage fish culture may impede water currents and could harbour unwanted pests of fish production (e.g., parasites). Furthermore, Petrell and Alie (1996) noted that technical and economic difficulties with fish/seaweed polyculture systems include the following:

- marketing and processing two different types of product;

- variable nutrient removal efficiencies by seaweeds;

- incompatible production rates of fish and seaweeds; and

- logistical problems resulting from shared space and equipment.

Integrated aquaculture in land‐based systems is more straightforward. It comprises defined (and often isolated) cultures of complementary species in a system. Seaweeds have been used to remove fish culture waste products in semi‐closed aquaculture systems. For example, U. lactuca was reported to remove 74% of ammonia and reduce water use and nitrogenous pollution by half (Neori and Shpigel, 1999). A problem occurs as the area required to reduce nutrient levels of fish is much larger than that of the intensive production area (e.g., >100 m2/t of fish). Essentially, this may mean that fish farmers may find themselves as seaweed farmers on the basis of farm area and product volume. The relative ratios are much more reasonable with prawn/shrimp farming where less than half of the farm area would need to be devoted to waste water treatment. Regardless of the form of animal aquaculture, increased productivity of seaweed production is essential to minimise culture area, but most important is the identification of value‐adding seaweeds that are themselves economically attractive. It should also be investigated whether high nutrient waters alter the value of seaweed biomass compared with natural conditions (e.g., reducing the quality of phycocolloids).

One use of seaweeds produced by integrated aquaculture is feedstock for marine herbivores. This principle has been adopted by abalone (Haliotis midae) growers in South Africa who culture Ulva (sea lettuce) to supplement diets comprising artificial feed and wild‐harvest kelp (Bolton et al., 2009). Ulva production in South Africa of ~500–1000 t/year is the largest crop of this taxon outside of Asia.

Additional research required to facilitate the uptake of integrated systems includes ensuring that seaweeds do not negatively alter growth conditions for the base unit cultures of fish. It remains to be demonstrated whether there are any positive (e.g., probiotic) effects for fish from integrated seaweed cultivation. Market research and education of the environmental and social benefits of these clearly sustainable systems will be important for the introduction and uptake of integrated aquaculture more broadly.

15.2.5 Diseases of Cultured Seaweeds

Because the mass cultivation of seaweeds is a relatively young and rapidly expanding industry, disease could potentially become the most important limiting factor for the domestication of seaweeds. Cultured seaweeds are affected by both physiological and pathological diseases. Most physiological diseases have environmental triggers which work to increase the susceptibility of biomass to disease. The following are examples:

- Control of ‘green rot’ (caused by too little light) is achieved by inverting the cultivation ropes so that the lower, overshaded, fronds receive sufficient light. If the disease occurs during the fast‐growing stage of kelp, tip‐cutting may be used to increase light intensity. As much as one‐third of the total length of the fronds may be cut off, greatly reducing the overcrowded condition and improving light penetration and frond health. The cut portion has a market in the alginate industry, so importantly is not wasted.

- ‘White rot’ disease always occurs in the fronds of the upper part of the cultivation ropes. It is believed that the three factors stimulating this condition are strong light, high water temperature and low nutrient levels. As the principal cause is believed to be strong light, treatment includes reduction of light intensity by lowering the level of cultivated algae in the water column. Fertiliser is also applied.

- ‘Ice‐ice’ is a common problem encountered in stressed individuals of Eucheuma and Kappaphycus (e.g., stressed from high temperature, low salinity, low light intensity). Tissue devoid of pigment is the first sign (creating a translucent or ‘ice’‐like appearance) and may be linked to stress from epiphyte attachment or microbial pathogens. Secondary problems stem from bacterial colonisation of these areas. Improved water quality (e.g., reducing stocking densities through harvest) can recover stock, but individuals often break at points weakened by the disease.

Several kinds of pathogenic disease have been recognised in seaweeds, but relatively few have been well documented (Gachon et al., 2010). Bacterial disease may be more frequent in young or vulnerable parts of the cultivation cycle. For instance, the sulphate‐reducing bacteria and hydrogen‐sulphide‐producing saprophytic bacteria, quite common in glasshouse cultivation for kelp sporelings, are causal agents in a disease characterised by plasmolysed oogonia and malformed sporophytes. Prevention measures include separating the sporeling cultivation system from the mature sporophytes and sterilising the water system with chlorine before the seeding process. Rotten and diseased fronds are periodically removed to reduce potential sources of infectious bacteria.

In ‘frond‐twist’ disease of raft‐cultivated kelp, the contagious and biotic nature of the disease was confirmed, and the causal agent found to be a mycoplasma‐like organism. Antibiotics such as tetracycline are effective treatments for this disease. Alginic‐acid‐decomposing bacteria were found to be the causal agent of a disease that causes detachment of summer sporelings. This condition can be effectively controlled using antibiotics.

In the absence of defined aetiology for diseases, some safeguards for reducing the incidence of disease include stock management (location and density), reduced pressures of productivity and maximising the genetic diversity of stock. It is possible that disease will become a particular problem for cultivation systems that rely on asexual fragmentation, as the genetic diversity of farmed stock may not be sufficient to deal with selective pressures resulting for high productivity. This would mean that the extraordinary production values for carrageenan‐producing red seaweeds in Indonesia and the Philippines could be most susceptible. Further development of disease‐resistant strains of seaweed will require more information on the mechanisms of pathogenicity and defence and on whether disease susceptibility and resistance are genetically determined traits.

15.2.6 Genetic Aspects of Seaweed Culture

As with all farmed organisms, significant benefits can be gained through appropriate breeding programs (Chapter 7). Research with seaweeds has sought to enhance characteristics such as yield and growth rates through genetic selection in the sexual phase of the life cycle. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s, superior strains of kelp were developed in China by intensive inbreeding and selection for specific characteristics, such as high productivity, high iodine content and increased thermal tolerance, which better met the demands of industry. Similarly, artificial seeding and strain preservation have facilitated the development of Porphyra cultivars, and molecular techniques have identified additional opportunities for selection through interspecific hybdridisation.

Whereas these developments were generally brought about through breeding programs and strain selection, more recently major developments in this field have been brought about using modern genetic manipulation techniques or genetic engineering. Examples of some of the modifications made to cultured red seaweeds using these techniques include increased tolerance to higher temperatures (e.g., Chondrus crispus, Kappaphycus alvarezii), increased agar or carrageenan content (e.g., C. crispus, K. alvarezii, Gracilaria tikvahiae), increased growth rates or tolerances (e.g., K. alvarezii, Eucheuma denticulatum, Porphyra yezoensis, P. umbilicas) or control of the life cycle to produce desired ploidy (P. umbilicas) (Cheney, 1999; Blouin et al., 2011). Selection of unique colour morphs, particularly for red seaweeds, is possible owing to the diverse array of photosynthetic pigments in these organisms, as seen in the beautiful commercial cultivars of Chondrus crispus produced by Acadian Sea Plants Ltd in Canada. Decreased productivity (e.g., growth) from cloned tissues is most pronounced where a limited number of strains or cultivars have been widely propagated for extensive periods of time. For this reason, maintaining genetic diversity as a safegauard against problematic diseases could be important, which means that those seaweeds that are fragmented may need stock supplements, periodic control of sexual reproduction to avoid genetic bottlenecks or new approaches such as the use of protoplasts and hybridisation (Charrier et al., 2015).

15.2.7 Future Developments for Seaweed Culture

The high value of seaweed products and their increasing use in industrial processes, and as sources of food and nutraceuticals, will ensure the continued expansion of the industry. Expansion within active geographic regions will occur primarily from improvements to culture techniques and genetically selected stock. The previous millennium saw development of large‐scale open‐ocean farming of seaweeds, particularly in China where automation of harvesting (using boats) has progressed for long‐line culture. Mechanisation of other commercial stock will also increase areal productivity. Adoption of new and improved materials will allow rapid seeding and harvesting of relatively large amounts of seaweed, reducing labour and cost. Diversification of uses for traditional products will be facilitated by processing R&D for nutraceutical, cosmetic or pharmaceutical uses. For example, wakame (Undaria pinnatifida) is an excellent source of fucoidan, a sulphated polysaccharide, with antioxidant activity and cardiovascular health benefits. High‐value end‐use relating to health and well‐being could facilitate the adoption of intensive cultivation of edible seaweeds outside Asia.

Expansion of the industry will also result from the uptake of seaweed culture in countries without a tradition of cultivation. Because seaweeds can be cultured throughout the world (not only in Asia), we should expect increases in production beyond the four countries, so far, that contribute >95% of global seaweed aquaculture (China, Indonesia, Korea, Philippines). Mechanisation and the control and reliability of production are important to industry expansion into new areas. This will be in part from the uptake of traditional seaweed crops and in part from the development of culture techniques for new culture species. About 30 countries harvest seaweeds from the wild, albeit some only as wrack (beached portions naturally torn from their substrata) yet half of these countries report harvests of <5000 t/year. Aside from an environmental obligation to reduce wild harvest of seaweeds to avoid disrupting the environment, aquaculture can provide supplemental income from a new industry. Greater control over harvest quality and time of seeding, early growth and production all contribute to a reduced ecological footprint for culture practices.

The economic potential of seaweeds and their products is diverse. Most of the new opportunities relate to different seaweed products and applications. For example, seaweeds and their products can be used for fertiliser, paper, additives, and potentially a range of energy conversion from biomass (e.g., bioethanol through to biodiesel, depending on the types of storage compound, carbohydrate versus lipids, respectively). There is renewed focus on a role for seaweeds in the global bio‐economy. This focus will require processors to derive multiple products from a single seaweed feedstock by using a ‘bio‐refinery’ to unlock new growth opportunities (Trivedi et al., 2016). A greater value‐add through co‐products can also be complemented by reducing the costs of seaweed production. For example, land‐based systems provide the greatest control of production, but costs have so far been prohibitive. However, the innovative practice of integrating seaweed production with existing aquaculture facilities (e.g., finfish) or other industries (e.g., agriculture, refineries or sewage treatment facilities) can offset the cost of inputs required for land‐based production. These practices offer to change the scope and application of seaweed aquaculture significantly in the coming decades, particularly if financial incentives exist for environmental services (e.g., carbon or pollutant taxes, nitrogen or phosphorus trading).

Determining value for environmental services will be facilitated by increasing pressure to minimise the impacts of aquaculture (fish) effluent. This should lead to more widespread adoption of seaweeds and other extractive organisms (e.g., molluscs) in bioremediation, becoming major components of new kinds of integrated system (e.g., integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) or integrated aquaculture more broadly fitting with other forms of industry such as municipal waste or agriculture). The importance of seaweed farming more generally is already apparent in the alleviation of some of the human‐induced impact on the oceans: specifically, nutrient loading of coastal waters. For instance, if 10 million t per year of red seaweed is produced (as per Indonesia; Figure 15.9), then this roughly equates to the extraction of ~20 000 t of nitrogen, ~2 000 t of phosphorus and ~600 000 t of dissolved carbon (based on a fresh weight: dry weight [dw] ratio of 5:1; N‐content of 0.5% dw; P‐content of 0.05% dw; C‐content of 15% dw). Environmental services, including the potential contributions to carbon sequestration, clearly add to the rationale for strategic mass cultivation of seaweeds in developed countries that are yet to participate. However, some caution must be shown in environmental management of cultivars and introductions between countries. Examples of past introductions include Macrocystis pyrifera (introduced to China from Mexico) and Kappaphycus alvarezii (introduced to China from the Philippines). Although crop translocation is deemed acceptable and applied broadly in agriculture, it is likely that similar approaches will be heavily scrutinised in developed nations. This creates a strong incentive to explore local strains for seaweed production. This research may in turn yield new and unexpected seaweed products and applications.

Figure 15.9 Seaweed aquaculture in Indonesia at a fishing village on Nusa Lembongan. Note individual farms (dark patches) covering the entire bay.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Nicholas Paul.

Creating sustainable livelihoods for developing nations represents an important sustainable development challenge for this century. Developing nations contribute significantly to global seaweed production and, for these nations, seaweeds are often fundamental to livelihoods. For example, seaweed aquaculture represents a significant proportion of gross domestic product in some Pacific island countries such as Kiribati (~30% of gross domestic product in 2000) and a significant portion of the aquaculture sector in Indonesia (Figure 15.10) where the vast majority of aquaculture volume and value is from seaweeds. In fact, the highest production of seaweed per capita comes from developing Pacific nations, such as Kiribati which produced ~10 000 t of red seaweed in 2000 (>100 kg per person compared with ~8 kg per person from China). The major limitations for expansion of these industries (existing and new) relate to the development of processing capabilities and identifying weakness in the supply chain that assist in greater trading capabilities, including more regional processing and refineries for carrageenan in tropical nations such the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Tanzania, Kiribati, Fiji, Kenya and Madagascar.

Figure 15.10 Seaweed (Kappaphycus) drying and packing on the island of Nusa Lembongan, Indonesia. (a) Fresh (foreground) and partly dried (background) seaweed laid out on mats on the ground. Seaweed is turned regularly by the farmer using rakes to ensure it dries over a couple of days. (b) Seaweed is combined from multiple farmers in small operations using paid staff to provide a uniform dried product. This dried biomass (<40% moisture) is packaged into large bags for transport to seaweed traders and processors.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Nicholas Paul.

Food security and nutrition (e.g., the provision of protein) is a fundamental concern for many people and represents a significant social challenge for the global community. Because seaweeds are nutritious, easily dried and processed, and have long shelf‐life, their aquaculture could be used to provide nutritional supplements in areas where essential nutrients are not easily sourced (e.g., inland Africa). Moreover, maladies from inadequate nutrition are not necessarily related to poverty. For instance, estimates are that >400 million people in China are deficient in iodine. Many seaweeds concentrate iodine and their consumption can reduce the risk of goitre and thyroid problems, re‐emerging problems in developed nations where iodine intake has been reduced. Similarly, in developed countries, trends towards whole food, macrobiotic and vegetarian lifestyles may catalyse the commercialisation of seaweed to supplement or replace some agricultural food sources. Clearly the role of seaweeds in both traditional and contemporary foods and applications is well‐defined and diverse opportunities exist for developing and developed countries alike.

15.3 Microalgae

15.3.1 Introduction

Microalgae are taxonomically extremely diverse being found in many Phyla and in almost every environment in nature. This great taxonomic and environmental diversity is also reflected in the wide range of metabolites they produce. Several species are grown commercially as sources of high‐value, fine chemicals such as carotenoids and fatty acids, nutraceuticals and cosmaceuticals, and animal feed ( Table 15.4). Others are used in wastewater treatment and in agriculture as soil conditioners. Microalgae are also proving to be potential sources of bioactive compounds such as antibiotics and anti‐cancer drugs and, although some of these compounds can be produced by chemical synthesis, many others will probably have to be produced through microalgae culture (Borowitzka, 2013a). Commercial culture of microalgae is still a very new industry and the full potential of microalgae remains to be developed with only a few hundred of the approximately 40 000 species of microalgae having been studied.

Table 15.4 Summary of the major current commercial or near commercial microalgae products, their value (based on current market prices), comparative market size and the species used for their production and cell content of the product. All algae, with the exception of those species marked with an asterisk are produced photoautotrophically; those marked with an asterisk are produced by heterotrophic culture.

| Product | Use | Approx Value of product (USD/kg) | Market Size | Algae | Approx Cell Content (% of dry weight) | Status |

| β‐carotene | Nutraceutical, Natural pigment | >600 | medium | Dunaliella salina | 3–5% | Commercial |

| Astaxanthin | Nutraceutical, Natural pigment | >2000 | medium | Haematococcus pluvialis | 1.5–4% | Commercial |

| Phycocyanin | Food and cosmetic pigment Fluorescent marker | ? >1000 | medium? small | Arthrospira | 10% | Commercial Commercial |

| Phycoerythrin | Food and cosmetic pigment Fluorescent marker | ? >1000 | medium? small | Porphyridium, Rhodella, Arthrospira | 10% | Mainly R&D Commercial |

| Fucoxanthin | Nutraceutical | >2000? | medium? | Diatoms & haptophytes | >15% | R&D |

| Paramylon (β‐1,3‐glucan) | Nutraceutical | >800 | small | Euglena | >45% | Commercial |

| Algal flour & oil | Food | ? | ? | Chlorella protothecoides* | 100% 40% | Commercial |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | Nutritional supplement | >30 | large | Crypthecodinium cohnii* | >10% | Commercial |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | Nutritional supplement | >30 | large? | Nannochloropsis, Phaeodactylum | >10% | Mainly R&D |

| Tocopherols | Vitamin | 10‐50 | medium | Euglena etc | <1% | R&D |

| Polysaccharides | Cosmetics, viscosifyers | >5 | medium | Porphyridium, Rhodella | ? > 50% | Mainly R&D |

| Pharmaceuticals | (very high) | large | Cyanobacteria, dinoflagellates, others | <<1% | R&D | |

| Biofuel | General | >1 | extremely large | Green algae, diatoms etc | 30% | R&D |

Although commercial culture of microalgae is a relatively new industry with only a small number of species and products, global production has grown significantly in the last 30 years. However, the high cost of production (Table 15.5) means that the product must also command a high sale price. It is interesting to note that the most expensive microalgae produced are those grown for use as feed for aquaculture species (Chapter 9), with the marked exception of ‘green water’ culture, which is a mixture of phytoplankton and used in the culture of fish and shrimp. Some of the factors contributing to high production costs are the high capital costs and high labour costs and, for microalgae used in aquaculture, the rather small scale of production (section 9.2.1, Figure 9.3).

Table 15.5 Estimated production costs for microalgae currently grown on a commercial scale.

| Alga | Estimated production cost (USD/kg dry wt) | Production system |

| Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis | 8–12 | Raceway systems. Raceways of up to about 0.5 ha area |

| Chlorella spp. | 15–18 > 50 | Centre pivot open ponds Closed photobioreactors |

| Dunaliella salina | 5 | Very extensive open ponds up to 250 ha in area (Production costs in systems using raceway ponds are higher) |

| Haematococcus pluvialis | > 40 | Closed photobioreactors and open ponds |

| Algae for aquaculture (e.g., Isochrysis, Tetraselmis and Skeletonema spp.) | 60–1000 | Big bags (lowest cost is for largest aquaculture facility in the USA) |

| Crypthecodinium cohnii | 2 | Grown heterotrophically on glucose in fermenters |

Commercial‐scale micro‐algal culture requires a good understanding of the life cycle of the alga being cultured, algal physiology and algal ecology. For example, in culture Dunaliella and Chlorella reproduce almost exclusively vegetatively, whereas Haematococcus undergoes morphological life‐cycle changes during culture, with astaxanthin accumulation occurring in the aplanospore stage. In order to achieve a high productivity and reliable culture, and to maximise the production of the desired final product, an understanding of the alga’s physiology allows identification of key environmental factors (e.g., light, pH, temperature) and nutrient requirements allowing the rational development of an optimal culture regime. An important element in successful commercial microalgae culture is selection of the correct algal species and strain, and in the future genetically modified strains may also be used. Again, an appreciation of the physiology and biochemistry is very important for successful genetic modification. Finally, managing a large‐scale outdoor culture of microalgae is not too dissimilar to that of managing a monospecific algal bloom and, therefore, knowledge of the ecology of the alga in its natural environment can be very useful.

Since most microalgae are photoautotrophs and require light for growth, a basic feature of all microalgae culture systems (with the exception of heterotrophic cultures systems; section 15.3.4) is that they are shallow so that light can reach all the cells. Commercial‐scale microalgae culture systems may be extensive, semi‐intensive or intensive. The cultures may also be either open to the air or fully contained (closed).

15.3.2 Extensive Culture

Extensive culture systems are very large and achieve only low cell densities of 0.1–0.5 g/L dry weight. The main microalga grown commercially in extensive culture systems is the chlorophyte, Dunaliella salina, which is grown in extremely large shallow ponds in Australia for the production of the carotenoid ß‐carotene (Borowitzka, 2013b). It grows best at very high salinities (~25–30% w/v NaCl – seawater salinity is about 3% NaCl) and high temperature (30–40°C). ß‐Carotene production from D. salina is greatest at high salinity and high light levels. The high salinity prevents almost all other organisms from growing in the ponds and competing with D. salina.

In commercial systems in Australia, D. salina is grown in shallow ponds of up to 250 ha each in area constructed with earthen walls on the bed of a saltlake or saline mud flats (Figure 15.11). The ponds are about 30–50 cm deep and the only water movement results from wind or convection. In such a system, the operator has little control over culture conditions other than salinity and nutrient concentrations. The ponds are usually operated in a semi‐continuous mode with part of the ponds harvested at regular intervals and with the medium being returned to the ponds after microalgae cells have been harvested. Nutrients are added as required for microalgae growth, and salinity is controlled by the addition of seawater. Since the algal density achieved in such systems is low, harvesting and further downstream processing is expensive and the final product must have a high value for the overall process to be economical. Despite this, the actual production costs for D. salina are among the lowest for any commercially produced microalga.

Figure 15.11 The extensive culture ponds of the Dunaliella salina β‐carotene plant at Hutt Lagoon, Western Australia, operated by BASF. The total pond area is over 750 ha.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Michael Borowitzka.

15.3.3 Semi‐Intensive Culture

Semi‐intensive culture systems require less land area than extensive culture; however, better mixing of the cultures and improved control of culture conditions result in cell densities of up to about 1 g/L dry weight. The first commercial large‐scale cultures of microalgae were developed in Taiwan in the 1950s for culturing the freshwater green alga, Chlorella, which is used as a health food. The algae are grown in circular concrete ponds of up to about 500 m2 surface area. The ponds have a centrally pivoted rotating arm that mixes the culture (Figure 15.12). This system results in uneven mixing, with the periphery of the pond being mixed much more than the centre because of the higher velocity of the mixing arm at the outer perimeter. The larger the pond, the greater is the difference between the periphery and the centre, and this limits the effective size of the ponds. Because of the inherent instability, the cultures need to be grown in batch mode. Each growth cycle is started as a small (~1 L) laboratory culture (section 9.2.2) and is scaled up by a factor of 5–10 at each step (Figure 9.3).

Figure 15.12 Central pivot ponds at a Chlorella production plant in Taiwan. The ponds at the front has an area of 0.5 ha.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Michael Borowitzka.

In the 1960s, a better pond design, the ‘raceway’ pond, was developed. These ponds consist of long channels arranged in single or in multiple loops (Figure 15.13). Early designs used a configuration consisting of relatively narrow channels with many 180° bends and propeller pumps to produce a channel velocity of about 30 cm/s. In the 1970s, paddle‐wheel mixers of various designs were introduced and found to be more effective, with reduced energy requirements and reduced shear forces on the microalgae cells. The numerous bends in the channels of the older designs also led to hydraulic losses and problems with solids deposition. These were minimised by using a single loop (raceway) configuration, with flow rectifiers at the corners. Simple geometric optimisation has also shown that a large pond with a low length to width (L/W) ratio gives the largest pond area for the least wall length, and is therefore cheaper to construct. Ponds can be up to about 6 m wide with the width being limited by paddle‐wheel design. Pond length is influenced by head loss relative to the mixing velocity and pond depth. Details of the design considerations for such systems are outlined by Borowitzka (2005).

Figure 15.13 A 400 m2 test paddle‐wheel driven raceway pond at an algae biofuels pilot plant at Karratha, Western Australia.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Michael Borowitzka.

Several factors need to be taken into account when designing the optimally sized pond. These include:

- optimal pond depth, taking into account the degree of light penetration;

- mixing velocity, which relates to the need to keep the algae in suspension, avoiding any poorly mixed regions and the effects of turbulence on the pond materials;

- the energy requirement for mixing; and

- materials from which the pond is constructed.

This pond design was first developed for high‐rate oxidation ponds used in the treatment of wastewater, but was soon also applied to the ‘clean’ culture of a range of microalgae, especially the cynobacterium, Arthrospira platensis (commonly referred to as Spirulina). Raceway ponds are also used in Israel for culturing D. salina, and in Hawaii for culture of Haematococcus pluvialis. The raceway ponds are more efficiently mixed than the circular central pivot ponds and pond size can be up to 1 ha in area with a depth of about 30 cm.

The ponds are either constructed of concrete, or with concrete walls or earthen walls lined with a plastic liner. The plastic liner is replaced with a concrete bottom in the region of the paddle wheel. Experiments have shown that microalgae productivity increases with increasing flow rate and that a velocity of at least 10 cm/s is necessary to avoid settlings of the cells; however, practical limitations in pond design mean that velocities in the range of 30 cm/s are optimal. In order to maximise productivity, the pond depth is about 20–30 cm and cell density must be controlled to minimise self‐shading by the cells.

Although productivity of up to 30 g/m2/day dry weight has been reported, actual annual average productivity is significantly lower than this with the best value of about 20 g/m2/day dry weight reported. Several attempts have been made to improve the productivity of these ponds by increasing turbulence and improving mixing.

Although raceway ponds are the main culture system used for the commercial‐scale culture of microalgae, its major limitation is that the system is open to the air, which may lead to contamination and infection by predators (mainly other algae, protozoa and fungi). These systems are, therefore, best suited to microalgae that grow in relatively extreme environments such as high pH (e.g., Arthrospira species) or high salinity (e.g., Dunaliella species) or fast‐growing algae such as Chlorella, Phaeodactylum or Scenedesmus species, which can outgrow most of their competitors.

15.3.4 Intensive Culture

In intensive cultures, the microalgae are grown under highly controlled optimum conditions in closed photobioreactors, which can result in cell densities of 1–10 g/L dry weight. High cell densities have the advantage of requiring a smaller area for the reactor and, in addition, harvesting costs are also reduced significantly.

Closed culture systems include:

- bag culture, which is widely used for the culture of algae for aquaculture (Figure 9.3);

- alveolar panels and other flat plate reactors of various designs;

- stirred tank reactors with internal illumination;

- tower reactors with external illumination;

- suspended narrow bags or tubes; and

- tubular reactors in various configurations.

‘Big Bag’ Systems

Probably the most widely‐used closed culture systems for mass culture of microalgae are the ‘big bag’ systems generally used in aquaculture hatcheries to feed larval fish, crustaceans, molluscs or rotifers (Figure 9.3). Although widely used, these systems are notorious for the instability of the cultures. This instability probably occurs because uniform mixing in the bags is very hard to achieve, resulting in potential build‐up of cells in unmixed areas, which, in turn, can lead to culture collapse, especially if the culture is not axenic (bacteria free). In order to achieve reasonably reliable cultures, it is essential to maintain axenic conditions, a feature that is not required for the tubular photobioreactors.

Tubular Photobioreactors

Many different tubular reactor designs have been developed to produce cultures of relatively high density (Zittelli et al., 2013). The first large‐scale tubular photobioreactor developed in France had a solar receptor constructed of five identical 20‐m2 units made of 25‐cm diameter polyethylene tubes floating on or in a large pool of water. The culture circulated through these tubes and temperature was controlled by either floating the tubes at the water surface (to heat) or by immersing them in the water (to cool). Water in the pool also provided a convenient support for the long tubes of the solar receptor. At the end of each solar receptor, a gas exchange tower removed photosynthetically produced oxygen and CO2 could be added. This pilot plant was quite successful in growing the red unicell, Porphyridium; however, it was technically complex and expensive, and required a large land area.

A more efficient arrangement for the tubes of the solar receptor is to wind them helically around a tower. This is the design of the ‘Biocoil’ (Figure 15.14), a system developed in the UK and optimised in Australia. Several pilot scale units of the Biocoil have operated in the UK and in Australia, with volumes up to 2000 L, and a very wide range of microalgae including Chlorella, Spirulina, Dunaliella, Tetraselmis, Phaeodactylum, Chaetoceros, Isochrysis, Pavlova, Porphyridium, Haematococcus and Skeletonema species have been grown successfully. The Biocoil system uses low‐density polyethylene or Teflon tubing of 25–30 mm diameter. This narrow diameter results in much higher productivity and reduced fouling of the inside of the tubes by the algae. The helical arrangement of the tubing also means that there are no sudden changes in direction of flow, which not only result in significant head losses, but can also lead to undesirable accumulation of algae. The maximum temperature in the reactors is controlled by evaporative cooling, achieved by running water over the reactor surface. The helical design also has the great advantage of good scale‐up properties. This means that the results obtained in smaller pilot experiments can be directly related to full‐scale production units. Systems such as the Biocoil also allow continuous culture, which results in more consistent quality of the algae produced and is cheaper. In Western Australia, Tisochrysis lutea (Isochrysis T. ISO) has been grown in a 1000‐L Biocoil (Figure 15.14) in continuous culture for more than 6 months.

Figure 15.14 A 1000 L pilot scale Biocoil‐type helical tubular photobioreactor in Perth, Western Australia.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Michael Borowitzka.

One of the key design features of these systems is the pumping system used to circulate the algal culture. Several types of pumps, including centrifugal, diaphragm, peristaltic and lobe pumps, as well as airlifts, have been used, and the choice of pump depends on the degree of fragility of the algae being grown.

Currently the most commonly used tubular photobioreactors have the tubes arranged vertically in long rows, usually connected to manifolds at their ends (Figure 15.15). The tubes are arranged vertically forming a fence‐like structure. This is the system used in the commercial culture of Haematococcus in Israel and in China, as well as for the production of Chlorella in Germany.

Figure 15.15 Vertical tubular photobioreactors at the Algae technologies Haematococcus pluvialis astaxanthin production plant at Kibbuz Ketura in Israel.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr S. Boussiba.

Flat‐Panel Photobioreactors

An alternative design for a closed photobioreactor are the flat‐panel reactors first developed in the 1980s. In the most common configuration the reactor consists of two rectangular panels of glass or Perspex spaced about 25 mm or more apart. A cheaper design in which plastic bags are placed within a rectangular metal framework has also been recently developed (Rodolfi et al., 2009). Some of the designs have a number of internal baffles. The panels can be inclined to capture the optimum amount of solar irradiation and the algal culture is mixed by aeration or circulated by pumping. The aeration also helps to remove photosynthetic O2, which at high concentrations will limit productivity due to photorespiration. CO2 can also be added to enhance microalgae growth. The temperature is usually controlled by spraying water over the panel surface in order to cool the cultures. Some systems use a heat exchanger; however, this is too expensive for large‐scale systems. These flat‐panel reactors can be very productive, but individual reactors are very difficult to scale up to any appreciable size and are expensive to operate.

Heterotrophic Culture

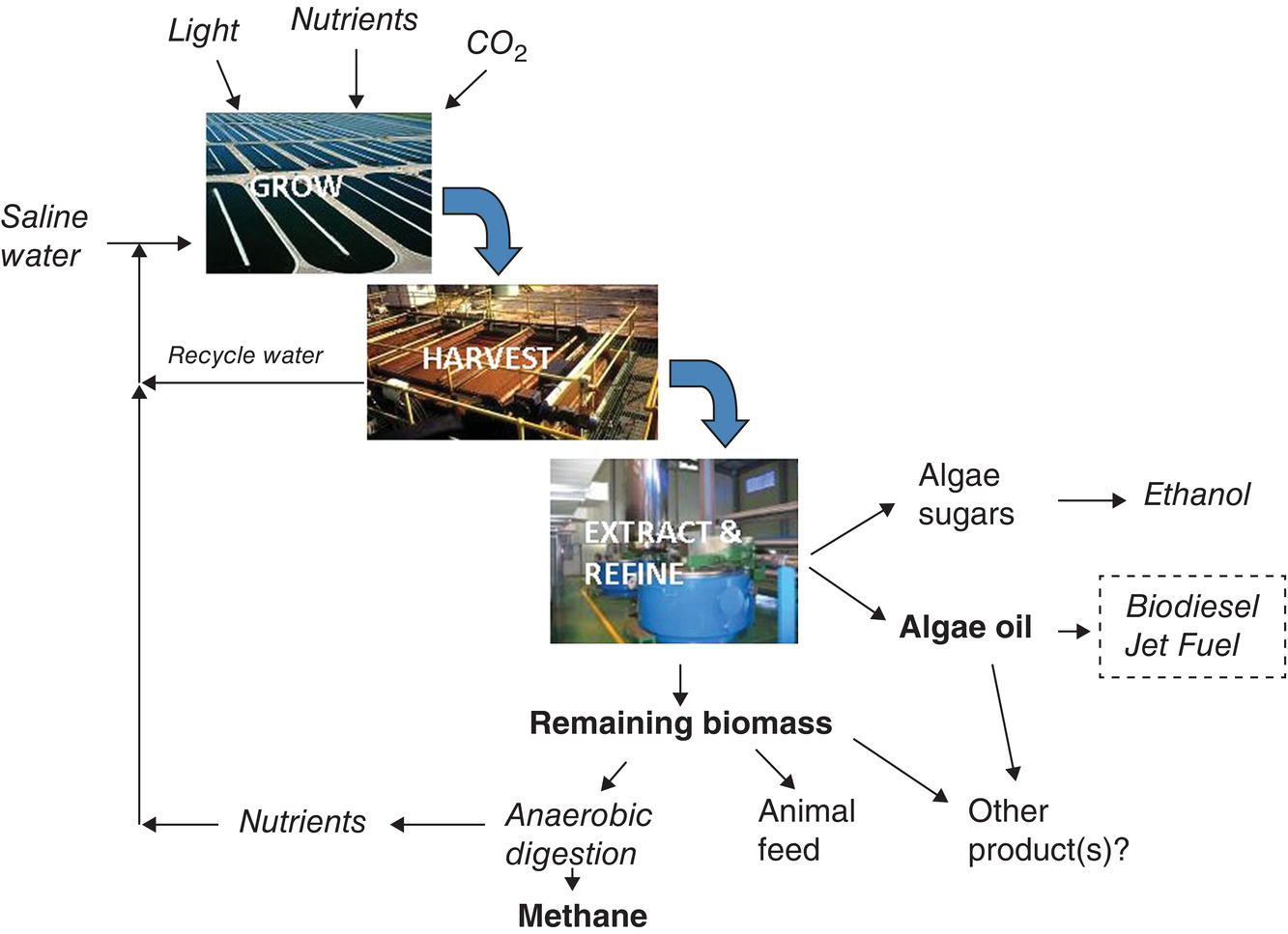

Closed fermenters have been developed for the heterotrophic production of long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids from microalgae (Bumbak et al., 2011). Sugars such as glucose or acetate serve as the energy and carbon source for the algae and this eliminates the need for light, which is a major cost in phototrophic microalgae culture systems. Furthermore, because cell density is not limited by light availability, microalgae can be cultured in relatively high densities with high biomass production. Heterotrophically grown microalgae are being produced commercially and have value as an aquaculture feed (section 9.2.5). Heterotrophic culture is also used to produce microalgae as a source of long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids mainly for use as nutrient supplements in infant formula.