9

Hatchery and Larval Foods

Paul C. Southgate

9.1 Introduction

Hatcheries are those aquaculture facilities concerned with the holding and conditioning of broodstock, spawning induction, larval rearing, and early juvenile or nursery culture. The range of foods used in aquaculture hatcheries must therefore be appropriate for adults, larvae and juveniles of the target species. Intensive rearing of the larval stages of fish and shellfish currently relies on the availability of live food organisms that are usually cultured on‐site at the hatchery and include microalgae, rotifers, brine shrimp and copepods.

9.2 Foods for Hatchery Culture Systems

9.2.1 Microalgae

Cultured microalgae have a central role as a food source in aquaculture. Microalgae are used directly as a food source for larval, juvenile and adult bivalves, and for early larval stages of some crustaceans and fish. They are also very important as a food source for rearing zooplankters, such as rotifers and brine shrimp, which, in turn, are used to feed crustacean and fish larvae.

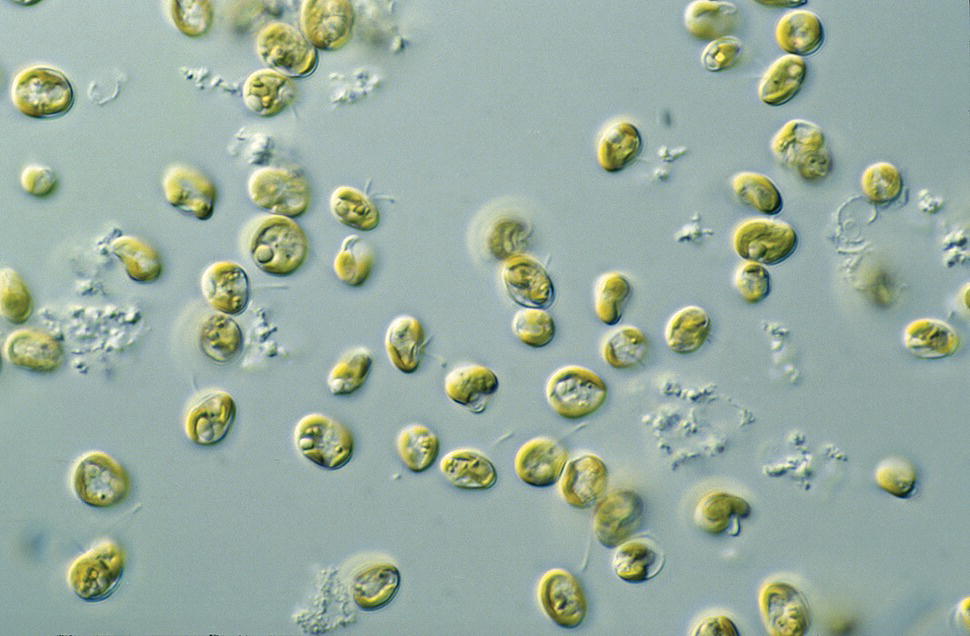

Golden‐brown flagellates (Prymnesiophyceae and Chrysophyceae), green flagellates (Prasinophyceae and Chlorophyceae) and diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) (Figure 9.1) are the most widely used microalgae in aquaculture. As their name suggests, the cells of flagellates possess one or more flagellae, which provide motility (Figure 9.2), whereas diatoms lack a flagellum and are non‐motile. Diatoms contain silica in their cell walls and may possess siliceous spines. Some species of diatoms exist as single cells (e.g., Chaetoceros gracilis), while other species have cells that are joined to form chains (e.g., Skeletonema costatum). The generalised morphology of microalgae used in aquaculture is shown in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Diagram showing general morphology of a flagellate and diatom.

Figure 9.2 Cells of Pavlova sp. (Prymnesiophyceae) viewed using a microscope. This species is a golden‐brown flagellate and their flagellae are visible in the photo.

Source: Photograph by CSIRO. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

9.2.2 Culture Methods

The simplest method of microalgal production is to bloom local species of phytoplankton in ponds or tanks. This is achieved by filling a pool or pond with local water, which is filtered to remove zooplankton, detritus and other unwanted particulates while retaining the smaller phytoplankton. With the addition of fertiliser (usually an inorganic fertiliser), adequate light and aeration, blooms of natural phytoplankton will develop. Although inexpensive, this method can be unreliable because the bloom is not guaranteed and there is little control over the species composition of the bloom. As such, the nutritional value of microalgae produced in this way is unpredictable.

More commonly in aquaculture, monospecific cultures of microalgae are intensively reared in systems where efforts have been made to minimise or exclude bacterial contamination. Monospecific axenic (bacteria‐free) starter cultures of many species of microalgae are available to the aquaculture industry from specialised laboratories. These are the basis for microalgae production, which involves scaling‐up the culture volume and the density of algal cells by maintaining favourable conditions for algal growth. An example of a suitable scale‐up procedure is shown in Figure 9.3. Stock cultures are maintained under controlled conditions of temperature and light. During the scaling‐up process, microalgae are usually transferred from container to container under axenic conditions using a laminar‐flow or sterile transfer cabinet. Culture vessels receiving the inoculant contain seawater that has been filtered (usually to 0.20–0.45 µm) and sterilised by autoclaving (Figure 9.4). Inoculating microalgae cultures under these conditions reduces the possibility of bacterial contamination. However, it is impracticable to use this method for culture vessels with volumes greater than ca. 20 L. In larger bag and tank cultures, efforts are made to reduce the bacterial population of the culture water by fine filtration (0.20–0.45 µm) and this may be followed by passage of the water through an ultraviolet (UV) steriliser. Flasks, bags or cylinders of microalgae may finally be transferred to indoor or outdoor ponds or pools where a large aquaculture operation requires large volumes of microalgae.

Figure 9.3 Typical scale‐up of microalgae cultures from starter cultures.

Source: Reproduced from Brown et al. (1989) CSIRO Marine Laboratories Report 205 Nutritional Aspects of Microalgae Used in Mariculture: A Literature Review, with permission from CSIRO Publishing.

Figure 9.4 Sterile flask culture of microalgae. Such cultures will be scaled‐up to useable volumes in larger flasks, bags and tanks (see Figure 9.3).

Source: Photograph by CSIRO. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

For growth, microalgae cultures require:

- aeration;

- a suitable nutrient medium; and

- light.

At each transfer, a clean vessel containing filtered (preferably sterile) seawater, to which culture medium has been added, is inoculated with microalgae. The newly inoculated vessel is provided with a filtered (0.20–0.45 µm) air supply to maintain microalgae cells in suspension and to supply sufficient carbon dioxide (CO2) for their growth. The air supply may also be supplemented directly with CO2 gas to further stimulate growth. Microalgae cultures are maintained under a controlled light and temperature regime, e.g., suitable conditions for most species of microalgae are provided by a photoperiod of 12–16 h, providing irradiance of 70–80 mE/m2/s at 20–25 °C. The growth of microalgae follows a distinct pattern and consists of a number of different phases (Figure 9.5).

- A lag phase occurs following inoculation and is characterised by a steady cell density.

- The exponential or log phase is marked by a rapid increase in cell density within the culture. This is the time when microalgae generally have optimal nutritional value.

- The stationary phase is reached as nutrients in the culture medium start to become limiting, and increasing cell density results in reduced light intensity within the culture; the rate of cell division slows and cell density reaches a plateau.

- The death phase is reached as, eventually, cells within the culture begin to die as nutrients in the culture medium become exhausted and the culture enters the phase characterised by declining cell density.

Figure 9.5 General pattern of changes in cell density over time in microalgae batch cultures. 1, Lag phase; 2, exponential or log phase; 3, stationary phase; and 4, death phase.

The cell density of a microalgae culture is usually determined by counting cells on a haemocytometer grid using a microscope, or use of high‐speed electronic particle counters.

There are three main methods for culturing microalgae:

- Batch culture involves growing a microalgae culture to a point at which it is completely harvested.

- Semi‐continuous culture involves partial periodic harvesting of culture vessels that are topped up with new water and fresh nutrient medium.

- Continuous culture involves harvesting cultured microalgae on a continuous basis and the volume removed from the culture vessel is continually replaced by new water and fresh nutrient medium.

The objective of continuous and semi‐continuous cultures is to maintain maximal growth rate (exponential phase) to maximise production and reduce variability in the biochemical composition (and nutritional value) of resulting microalgae. In batch cultures, the nutrient composition can vary widely according to the growth phase and age of the culture.

9.2.3 Nutrient Media

Many nutrient media have been developed for microalgae culture. They generally contain macronutrients to provide nitrogen and phosphorus (e.g., sodium nitrate, sodium glycerophosphate), trace metals and vitamins. A commonly used medium is the f/2 medium of Guillard (1972), whose composition is shown in Table 9.1. Nutrient media are made up from distilled water to which nutrients are added. It is convenient to make up concentrated standard stock solutions of media, which are then added to microalgae culture vessels to provide appropriate nutrient levels. In general, 1–3 mL of stock nutrient solutions is added to each litre of culture water. Given the structural importance of silica in diatoms, a source of silica (usually sodium metasilicate) should be included in nutrient media used to culture diatoms. A stock solution is prepared by dissolving sodium metasilicate (40 g) in 1 L of distilled water, and 0.2–0.4 mL of the resulting solution is added per litre of culture water. Nutrient media are generally added to smaller culture containers (e.g., glass flasks) before they are sterilised by autoclave. Once cooled, containers are inoculated to begin new microalgae cultures.

Table 9.1 The composition of f/2 medium for microalgae culture.

| Nutrient | Concentration/L |

| NaNO3 | 75 mg |

| NaH2PO4 | 5 mg |

| *Na2SiO3 | 15–30 mg |

| Trace metals | |

| Na2EDTA | 4.36 mg |

| FeCl3.6H2O | 3.15 mg |

| CuSO4.5H2O | 0.01 mg |

| ZnSO4.7H2O | 0.022 mg |

| CoCl2.6H2O | 0.01 mg |

| MnCl2.4H2O | 0.18 mg |

| Na2MoO4.2H2O | 0.006 mg |

| Vitamins | |

| Cyanocobalamin | 0.5 µg |

| Biotin | 0.5 µg |

| Thiamine HCl | 100 µg |

* Required for diatom cultures only.

9.2.4 Nutritional Value of Microalgae

When considering the suitability of various species of microalgae as a food source, the first concern is their physical characteristics. Factors such as:

- cell size

- thickness of cell wall

- digestibility

- presence of spiny appendages, and

- chain formation (e.g., diatoms)

influence the nutritional value of a particular species. Clearly, microalgae must have suitable physical characteristics to enable ingestion and, once ingested, must be digestible. Cultured invertebrate larvae vary in their feeding and digestive mechanisms, and this greatly influences the sizes and kinds of microalgae that can be ingested and digested. For example, shrimp larvae have a complete set of setous mouthparts adapted to feeding on chain diatoms. However, such diatoms cannot be captured and ingested by the ciliated feeding structures of bivalve mollusc larvae.

Assuming suitable physical characteristics appropriate for ingestion, and subsequent digestion, the nutritional value of a given microalga is determined by its biochemical or nutrient composition. Biochemical composition varies greatly between species (Table 9.2). It is also influenced by the growth phase from which the microalgae cells were harvested, and by abiotic factors such as:

- light (photoperiod, intensity and wavelength);

- temperature;

- nutrient medium (composition and concentration);

- salinity;

- nitrogen availability; and

- CO2 availability.

Table 9.2 The gross nutritional composition of microalgae commonly used in aquaculture.

Source: Data complied from Parsons et al. (1961), Utting (1986) and Whyte (1987).

| Composition (%) | |||

| Species | Protein | Carbohydrate | Lipid |

| Golden‐brown flagellates | |||

| Isochrysis clone T‐ISO | 44 | 9 | 25 |

| Isochrysis galbana | 41 | 5 | 21 |

| Pavlova lutheri | 49 | 31 | 12 |

| Diatoms | |||

| Chaetoceros calcitrans | 33 | 17 | 10 |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 33 | 24 | 10 |

| Skelotenema costatum | 37 | 21 | 7 |

| Green flagellates | |||

| Dunaliella salina | 57 | 32 | 9 |

| Tetraselmis suecica | 39 | 8 | 7 |

For example, protein levels decrease while lipid and carbohydrate levels typically increase during the stationary phase of a culture. Similarly, the protein content of microalgae is greatly influenced by the nitrogen content of the culture medium. Culture conditions also influence levels of micronutrients such as fatty acids and vitamins in the resulting microalgae. As such, the conditions under which microalgae are grown, and the stage at which they are harvested, may greatly influence their nutritional value. More information on the factors influencing the nutrient content of cultured microalgae is provided by Brown et al. (2013).

The nutritional requirements of cultured aquatic organisms are discussed in Chapter 8. Numerous growth trials, using different species of microalgae as food, have shown that differences in the food value of microalgae are related primarily to their fatty acid and carbohydrate compositions. As detailed in section 8.4.2, marine fish and shellfish larvae have an essential dietary requirement for n‐3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs). As such, n‐3 HUFA content is an important factor in determining the nutritional value of microalgae, and it is generally accepted that species containing the essential fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n‐3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n‐3) will be of high nutritional value for cultured animals. Table 9.3 shows the n‐3 fatty acid compositions of various species of microalgae, which vary widely between species. Golden‐brown flagellates and diatoms generally contain relatively high levels of essential fatty acids (EFAs), whereas others, notably species of green algae, contain low levels of EFAs or none at all.

Table 9.3 The n‐3 fatty acid compositions (% total fatty acids) of selected species of microalgae used in aquaculture.

Source: Data from Volkman et al. (1989).

| Fatty acid | |||

| Species | 18:3n‐3 | 20:5n‐3 | 22:6n‐3 |

| Golden‐brown flagellates | |||

| Isochrysis clone T‐ISO | 3.6 | 0.2 | 8.3 |

| Pavlova lutheri | 1.8 | 19.7 | 9.4 |

| Diatoms | |||

| Chaetoceros gracilis | 5.7 | 0.4 | |

| Chaetoceros calcitrans | Trace | 11.1 | 0.8 |

| Thalassiosira pseudonana | 0.1 | 19.3 | 3.9 |

| Green flagellates | |||

| Tetraselmis suecica | 11.1 | 4.3 | Trace |

| Dunaliella tertiolecta | 43.5 | ||

| Nannochloris atomus | 21.7 | 3.2 | Trace |

The carbohydrate content of microalgae is another important factor in determining nutritional value. Assuming that dietary EFA requirements are met, research has shown that growth and condition of bivalve larvae are correlated with dietary carbohydrate content. Dietary carbohydrate is used primarily as an energy source and is considered to spare dietary protein and lipid, which can then be utilised for tissue growth (section 8.2). Diets consisting of more than one species of microalgae are generally considered nutritionally superior to a single‐species diet. They are thought to provide a better balance of nutrients by minimising any nutritional deficiencies present in any of the component species.

Choosing an appropriate species of microalgae for use in an aquaculture hatchery requires careful consideration of their suitability for culture and use under local conditions. This is particularly important when microalgae are cultured in outdoor tanks. The three most important factors to consider for outdoor culture are temperature, salinity and light intensity. For example, in the tropics, the ability of microalgae to tolerate fluctuating salinity and temperature is particularly important in areas where cultures may experience periods of high rainfall and high temperatures. Microalgae vary in their optimal temperature and salinity ranges (Table 9.4). Light intensity also affects the growth rates of microalgae and may alter their biochemical composition and therefore their nutritional value. Again, this is of particular importance in areas of high natural light intensity such as the tropics.

Table 9.4 Salinity and temperature tolerances of microalgae commonly used in aquaculture.

Source: Data from Jeffrey et al. (1992).

| Species | Salinity tolerance (‰) | Temperature tolerance (°C) |

| Golden‐brown flagellates | ||

| Isochrysis sp. (T‐ISO) | 7–35 | 15–30 |

| Pavlova salina | 21–35 | 15–30 |

| Pavlova lutheri | 7–35 | 10–25 |

| Diatoms | ||

| Chaetoceros calcitrans | 7–35 | 10–30 |

| Chaetoceros gracilis | 7–35 | 15–30 |

| Thalassiosira pseudonana | 10–20 | |

| Skeletonema costatum | 14–35 | 10–20 |

| Green flagellates | ||

| Tetraselmis suecica | 7–35 | 10–30 |

| Dunaliella tertiolecta | 7–35 | 10–30 |

| Nannochloris atomus | 7–35 | 10–30 |

| Nanochloropsis oculata | 7–35 | 10–30 |

On the basis of their known ranges of tolerance to these parameters, microalgae can be categorised according to their suitability for culture and use in different environments. For example, Jeffrey et al. (1992) divided a range of microalgae species according to their temperature tolerances into:

- excellent universal species, which show good growth at 10–30 °C (e.g., Tetraselmis suecica, T. chuii, Nannochloris atomus)

- excellent tropical and sub‐tropical species, which show good growth at 15–30 °C (e.g., Isochrysis clone T‐ISO, Chaetoceros gracilis, Pavlova salina)

- good temperate species, which show good growth at 10–20 °C (e.g., Chroomonas salina, Skeletonema costatum, Thalassiosira pseudonana).

9.2.5 Recent Developments in Microalgae Production

Despite its central nutritional role in aquaculture hatcheries, production and use of cultured live microalgae presents a number of potential problems for aquaculture hatcheries:

- On‐site production of microalgae is labour intensive and is associated with high running costs (up to 30–50% of hatchery operating costs).

- On‐site production of microalgae requires specialised facilities and dedicated personnel. There are substantial establishment costs, and microalgae culture requires hatchery space that could otherwise be devoted to production of the target species.

- Microalgae cultures can crash through failure of the culture system or infection with contaminant or pathogenic organisms. Either case may result in a shortage of food for the culture organisms.

Research to overcome some of these problems has resulted in the development of microalgae products that have become commercially available to aquaculture hatcheries including:

- microalgae concentrates; and

- dried microalgae.

Both allow microalgae to be stored in concentrated form until required. The major advantage of using concentrated or dried microalgae is that the microalgae is cultured at a central facility and then distributed to hatcheries. This eliminates the need for hatcheries to have microalgae culture facilities which could result in considerable savings in infrastructure and running costs.

9.2.5.1 Microalgae Concentrates

Microalgae concentrates are prepared by removing the culture medium from the microalgae culture to produce a thick paste of concentrated microalgae cells. The resulting microalgae cells are intact and remain in suspension with minimal agitation of the culture water to which they are added. Microalgae concentrates have very high cell densities (billions of cells/mL) and can be stored for months or years in a refrigerator or frozen. A number of species of microalgae are now available in concentrated form from commercial suppliers. They include species from genera commonly used in aquaculture such as Tetraselmis, Isochrysis, Pavlova and the diatoms Thalassiosira. Microalgae concentrates composed of a mixture of microalgae species are also available commercially and have particular application as foods for shellfish broodstock and zooplankton production. Microalgae concentrates have found increasing application in aquaculture hatcheries over recent years (Reed and Henry, 2014) and have been used successfully as a total replacement for live cultured microalgae as a food for the larvae and early juveniles of a number of invertebrate species (Southgate et al., 2016; Duy et al., 2017).

9.2.5.2 Dried Microalgae

Dried microalgae preparations have been produced from microalgae grown heterotrophically. This technique involves growing microalgae in the dark, using sugars rather than light as an energy source (section 15.3.4). Growth under these conditions produces microalgae with a considerably different nutritional composition to that of the same species grown using conventional culture methods with light. Although the number of microalgae species that can be produced in this manner is limited, some have been produced commercially. A number of studies have shown the value of dried microalgae as a food source for crustacean and fish larvae, and for the larvae and spat of bivalve molluscs (Knauer and Southgate, 1999). Although dried microalgae preparations offer prolonged shelf life, significant structural damage to the cell can result for the drying process.

9.2.6 Zooplankton

As well as cultured microalgae, hatcheries that culture fish and crustacean larvae also rely on zooplankton as a larval food source. The two major organisms cultured for this purpose are rotifers and brine shrimp. However, recent years have seen considerable research effort directed towards the development of mass‐culture techniques for copepods and their use as live feeds in aquaculture.

9.2.7 Rotifers

Rotifers (Brachionus species) are widely used in aquaculture as a food for the larvae of fish and crustaceans, and their use in aquaculture was reviewed by Dhont and Dierckens (2013). Rotifers have a number of characteristics that confer suitability as a live food for use in aquaculture hatcheries including:

- suitable size range for ingestion by fish larve;

- suitable for mass cultured at high densities;

- a high reproductive rate under favourable conditions;

- broad temperature and salinity tolerances; and

- slow swimming behaviour that incites prey capture responses.

The species typically used in marine aquaculture hatcheries are:

- Brachionus plicatilis (known as large or L‐type), which is ca. 130–340 µm in length;

- B. ibericus (known as small or S‐type) which is ca. 100–230 µm in length; and

- B. rotundiformis (known as super small or SS‐type), which is ca. 90–190 µm in length.

However, there is some confusion regarding the taxonomy of rotifers and it has been suggested, for example, that the B. plicatilis complex may be composed of at least 14 species. Marine rotifers are generally unsuitable as a food for freshwater fish larvae because of their limited tolerance to freshwater. However, the freshwater rotifer, Brachionus calicyflorus, has shown potential as a larval food source for freshwater species and its culture and use in freshwater fish larviculture were discussed by Arimoro (2006). An important consideration in rotifer culture is selection of a strain best suited to the mouth size of the target species.

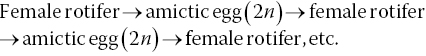

Rotifers consist of a lorica or body shell from which the foot extends ventrally and the head extends dorsally (Figure 9.6). The head has two bands of cilia used for the capture of food particles and for locomotion. The life cycle of the rotifer (egg‐juvenile‐adult) takes 7–10 days. Cultures may contain both males and females, but males are rare and considerably smaller than females. Rotifers reproduce sexually or asexually depending on culture conditions. Under favourable conditions, reproduction is asexual and the female produces diploid amictic eggs, which she carries until they hatch into females:

Figure 9.6 A female rotifer, Brachionus plicatilis, with a single egg (at bottom). The body is enclosed within a shell or lorica and the ciliated head is visible at the top of the animal. The flexible foot extends to the right‐hand side of the photo.

Source: Photograph by Sofdrakou. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 4.0.

Most reproduction in cultured rotifer populations occurs by this method. However, in unfavourable culture conditions, reproduction occurs sexually and females produce smaller haploid mictic eggs (n) that hatch into males if not fertilised. If fertilised, they become resting eggs that have a dehydration‐resistant outer shell. They can remain dormant for several years and hatch into females when conditions become favourable. The presence of males in rotifer cultures therefore indicates poor culture conditions.

9.2.8 Rotifer Culture

9.2.8.1 Rotifer Culture Methods

Brachionus plicatilis, B. ibericus and B. rotundiformis are euryhaline and productive at salinities between 4‰ and 35‰. Optimal water temperature varies between species, with B. rotundiformis and B. plicatilis most productive at high (30–35 °C) and low (15–25 °C) water temperatures respectively. Rotifer cultures are generally maintained at a salinity of 20–35‰, within a temperature range of 20–30 °C and with gentle aeration. Successful rotifer culture requires the maintenance of constant conditions. Water quality must be maintained by regular cleaning to prevent the build‐up of detritus and faecal matter. Conventional rotifer cultures can be very productive and may reach densities of 700–1000 rotifers/mL; however, ultra‐high‐density culture methods with 10 000–30 000 rotifers/mL have been developed.

Rotifers are usually cultured using either batch, semi‐continuous or continuous methods. Batch culture is the most widely used method and is conducted with either constant culture volume with increasing rotifer density, or constant rotifer density with increasing volume. When cultured at a constant density, new clean water is added to the culture vessel as rotifer density increases and this helps maintain appropriate water quality and supports improved production. Batch cultures are generally harvested after two to four days when a small volume of the culture can be used to start a new batch culture. During harvest rotifers are separated from culture water and from uneaten clumps of food and flocs using mesh sieves. They can be used immediately after harvest or stored at a low temperature (4 °C) for up to five days for later use.

Use of recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) in rotifer culture supports higher rotifer densities and higher production rates, and allows rotifer cultures to be maintained for several weeks. Rotifer density in such systems may reach > 10 000 rotifers/mL and because of this greater technical input is required including input of oxygen or ozone to maintain dissolved oxygen levels above 4 ppm.

The health of rotifer cultures can be assessed by monitoring swimming activity and the number of eggs present. Rotifers should be free‐swimming (not attached to the surfaces of culture vessels) and healthy cultures contain actively swimming females with many carrying more than one egg (Figure 9.6). Rotifer cultures should be sampled regularly to assess culture health. Determining the ratio of the number of eggs over the total number of females allows an estimation of both the health and imminent productivity of the culture. The egg ratio should be no lower than 10% and the presence of male rotifers indicates production problems because sexual reproduction occurs only when environmental conditions become unfavourable.

9.2.8.2 Foods for Rotifer Cultures

Rotifers are hardy and are easily mass cultured on a wide variety of foods. Mass culture of rotifers is usually initiated by inoculating a culture of microalgae with rotifers. Under suitable conditions, the rotifers consume the microalgae and their population rapidly increases. Consumption of microalgae must be monitored regularly and more microalgae added when required; it is important to ensure constant food availability. A portion of the culture water is usually removed from the rearing vessels on a daily basis and replaced with a similar volume of microalgae culture. Water can be removed by siphoning through a 60‐µm sieve, which prevents removal of rotifers. Bakers’ yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and commercially produced modified yeast are also commonly used as a food for rotifers, either singly or in combination with microalgae. Rotifers ingest food particles ranging in size from 0.3 µm up to 21 µm. Various species of microalgae are used to culture rotifers, including Nannochloropsis, Tetraselmis, Isochrysis and Pavlova, and commercially‐available microalgae concentrates (section 9.3.4.1) are increasingly used as a food in rotifer culture. The microalga Nannochloropsis oculata and bakers’ yeast are considered excellent foods for maintaining rotifer cultures. Food must be provided to rotifers several times a day and it is not uncommon for rotifer cultures to have continuous food input.

The nutritional value of cultured rotifers is largely determined by their food. For example, rotifers reared on bakers’ yeast, which is deficient in essential fatty acids (EFA), are themselves deficient in these fatty acids. For this reason, rotifers reared on yeasts or other foods with low levels of EFA are usually fed microalgae (in fresh or concentrated form), or artificial feeds that are high in EFA, prior to their use as a larval food source. This process is generally known as enrichment and is outlined in section 9.2.14.

9.2.9 Brine Shrimp

Brine shrimp (Artemia species) are found worldwide in salt lakes and similar habitat, in environments with salinities ranging from approximately 10 to 340 ‰. Their inactive dry cysts can be harvested in large quantities and stored in a dry state for many years. When immersed in saline water, the cysts rehydrate and become spherical, and the embryo inside begins to metabolise. The cyst ruptures after ca. 24 h and a free‐swimming nauplius emerges (Figure 9.7). This first larval stage (instar I) is generally 400–500 µm long and brown‐orange in colour. It has a single red eye and three sets of appendages, which have sensory, locomotory and feeding functions. Instar I larvae do not feed as their digestive tract is not yet functional. After ca. 12 h the nauplius moults to the instar II stage, which has a functional gut and begins to ingest small particles such as microalgae.

Figure 9.7 Hatching and development of brine shrimp (Artemia species). 1, Dry cyst; 2, hydrated cyst; 3, breaking; 4, hatching; 5, nauplius; 6, larger metanauplius.

Brine shrimp undergo ca. 15 moults over 8–14 days to produce mature adults 10–20 mm in length. The body is covered with a thin, chitinous exoskeleton that is shed periodically, although females must moult prior to ovulation. Like rotifers, brine shrimp can reproduce sexually or asexually (Figure 9.8). Under favourable conditions, females produce free‐swimming nauplii (ovoviviparous reproduction) and under optimal conditions, brine shrimp can reproduce at a rate of 300 nauplii every 4 days. However, under unfavourable conditions, such as high salinity and low oxygen, the shell glands of the female become active and secrete a thick shell around the developing gastrula, which enters a dormant state (diapause). These embryos are released by the female as cysts (oviparous). Females are able to switch between these two modes of reproduction depending on environmental conditions. Production of cysts has obvious advantages for aquaculture. Dry cysts can be easily stored and live feed (in the form of nauplii) can be produced when required.

Figure 9.8 Adult male and female Artemia sp. The male (upper) is holding the female using his claspers and eggs can be seen in the ovisac or broodpouch of the female.

Source: Photograph by Hans Hillewaert. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 4.0.

9.2.10 Production and Sources of Brine Shrimp Cysts

The two primary and traditional sources of Artemia cysts for aquaculture are the coastal salt works in San Francisco Bay in California (USA) and the Great Salt Lake in Utah (USA) (Figure 9.9). The Great Salt Lake (GSL) has become the primary source for Artemia cysts used in aquaculture. At its peak the GSL industry was composed of around 40 companies that used a fleet of more than 200 boats to harvest cysts from the lake. But this is a natural ecosystem influenced by climatic conditions that result in periodic fluctuations in cyst production and inconsistent supply to the aquaculture industry. The 'Artemia crisis' of the 1990s saw greatly reduced harvests of Artemia cysts from GSL because of declining salinity (Leger, 1999). Production at GSL has now recovered to supply more than 90% of global demand, but has fluctuated from ca. 2000–12000 t/yr over the last decade. The Artemia crisis of the 1990s highlighted the need for diversification in supply of Artemia cysts to the aquaculture industry and other production sites were established by introducing Artemia into areas where they do not naturally occur. Production of Artemia cysts for aquaculture production now occurs in countries such as Australia, China, Vietnam, Russia and Kazakhstan. Current global demand for Artemia cysts is ca. 3000 t/yr with greatest annual consumption of ca. 1500 t in China.

Figure 9.9 Salt evaporation ponds used for production of Artemia cysts on the western shore of San Francisco Bay, California.

Source: Photograph by Doc Searls. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons license, CC BY‐SA 2.0.

The majority of Artemia cysts supplied to the global aquaculture industry are made up by Artemia franciscana from GSL. This species has also been introduced to other areas both deliberately (e.g., Vietnam) or as a result of gradual dispersal and out‐competing local populations (e.g., India, Sri Lanka, Australia and coastal areas in the Mediterranean and China). Cysts are now marketed with emphasis on quality criteria relating to yield (e.g., hatch rate and cysts size) and nutritional composition (e.g., fatty acids and vitamin contents). Development of Artemia resources other than GSL is likely to result in greater selectivity for aquaculture hatchery managers.

9.2.11 Hatching Brine Shrimp Cysts

Although cysts can be successfully incubated in full‐strength (35‰) seawater, the hatching rate is generally superior at low salinities and a salinity of 5‰ is optimal. Cysts are incubated at densities up to 5 g/L culture medium, which is maintained at 25–30 °C with vigorous aeration. Dissolved oxygen content must be maintained above 2 mg/L and, to facilitate good aeration and water movement, culture vessels are usually V‐shaped or conically based. Cultures require a pH of 8–9 and constant illumination at the water surface. Culture conditions must be constant during incubation. Within 24 h, the majority of cysts will have hatched.

To harvest hatched nauplii, aeration is stopped, causing the cyst shells to float to the top of the culture vessel. Nauplii are positively phototaxic, and this behaviour can be used to concentrate them prior to harvesting by siphon. It is important that the number of cyst shells accompanying the nauplii is limited. Cyst shells have the potential to introduce disease and bacteria into larval cultures and can cause digestive disorders in fish larvae. Contamination with cyst shells can be minimised if the cysts are decapsulated prior to incubation.

9.2.12 Decapsulation of Cysts

The process in which the outer shell or chorion is removed from hydrated brine shrimp cysts is decapsulation. This is achieved by treating hydrated cysts with hypochlorite solution, which dissolves the chorion without damaging the embryo inside. Prior to decapsulation, dried cysts are rehydrated in freshwater for 60–90 min at the rate of 1 g of cysts per 30 mL of water. Approximately 20–30 mL of liquid bleach (sodium hypochlorite NaOCl) is added per gram of cysts, and the solution stirred continuously. The colour of the solution changes as the chorion is dissolved, and decapsulation is complete within 24 min when the solution becomes orange in colour. The solution is then poured through a sieve to remove the chlorine solution. The decapsulated cysts retained on the sieve are washed thoroughly with seawater or freshwater until no further chlorine smell can be detected. Any residual chlorine can be removed from decapsulated cysts by washing in 0.1% sodium thiosulphate solution for 1 min. The decapsulated cysts are then washed and placed into a medium for hatching, or they may be stored at 4 °C for a short period before hatching. Decapsulation offers major advantages in limiting potential digestive and disease problems caused by cyst shells; it disinfects brine shrimp embryos and improves hatch rate. Decapsulated cysts can also be offered directly as a larval food source, with a major advantage being that, prior to hatching, embryos have their maximum energy content. For further information on hatching and decapulation of Artemia see Dhont and Van Stappen (2003).

9.2.13 Culturing Brine Shrimp

For the production of large or adult brine shrimp, nauplii are reared in tanks at an initial stocking density of ca. 1000–3000/L. Nauplii are initially fed microalgae at a density of approximately 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells/mL; the feeding rate is adjusted as the brine shrimp grow and more food is required. Best growth of brine shrimp cultures occurs with:

- good aeration;

- good water quality;

- a readily available food supply;

- low light conditions;

- 25–30°C; and

- 30–35‰ salinity.

Culture tanks must be cleaned regularly to remove detritus and faecal matter to maintain water quality. Under suitable conditions, production rates in the order of 57 kg (wet weight) of brine shrimp per cubic metre are achievable using batch culture techniques.

Brine shrimp nauplii have their greatest energy content at hatching and, because instar I nauplii do not feed, there is a 24% reduction in organic content and a 27% reduction in lipid content between instar I and instar II. Although the lipid and fatty acid content of brine shrimp varies according to the geographical origin of the cysts, they are generally considered to be deficient in essential fatty acids (EFA). The nutritional value of instar II nauplii, particularly their fatty acid content, can be significantly improved using an appropriate enrichment procedure.

9.2.14 Enrichment of Rotifers and Brine Shrimp

Rotifers and brine shrimp are extensively used in aquaculture, primarily because they are amenable to mass culture, not because they are an ideal food source (Table 9.5). Rotifers and many strains of brine shrimp have very low levels (or a total lack) of certain EFA that are required for normal growth and development of marine larvae (section 8.4.2). To overcome these deficiencies, the EFA content of rotifers and brine shrimp has to be manipulated using fatty acid enrichment techniques. This process involves feeding a nutrient source rich in EFA to the rotifers or brine shrimp prior to feeding them to the cultured larvae. Various materials can be used for enrichment, including microalgae, oil suspensions and self‐emulsifying concentrates, microencapsulated and microparticulate products and yeasts, and a number of enrichment preparations are available commercially. Enrichment results in an increase in the EFA content of the live food organism that increases dietary EFA intake by the target species, supporting improved survival.

Table 9.5 Some potential problems associated with use of rotifers and brine shrimp.

| Disadvantage | Comments |

| Nutritional deficiency | Both brine shrimp and rotifers have inadequate fatty acid compositions for marine larvae. They must be artificially enriched prior to their use as food, which adds to the expense of food production |

| Nutritional inconsistency | Live food organisms may vary in their nutritional composition according to the source of stock (i.e., source of Artemia cysts) and the nutritional composition of their food(s) |

| Reliability of supply | Hatcheries in most parts of the world rely on a supply of brine shrimp cysts from North America. Availability may fluctuate from year to year and imports may be subject to quarantine problems |

| Contamination | Live foods can be vectors for inadvertent introduction of disease and contaminants to larval cultures |

The degree to which EFA are incorporated into rotifers and brine shrimp during enrichment is influenced by a number of factors including:

- the duration of the enrichment procedure;

- the density of rotifers or brine shrimp; and

- the density and EFA content of the enrichment material.

Although enrichment procedures were developed to improve the EFA composition of live food organisms such as rotifers and Artemia, this process is also used to improve dietary energy intake and consumption of other important nutrients such as protein, phospholipids, sterols and vitamins. Live food enrichment is also used as a means of presenting therapeutic compounds, pigments, antioxidants and enzymes to the larvae of the target species via their foods.

The organic load of the culture medium and live food organisms can become very high during the enrichment process and bacterial load can increase significantly. Thorough rinsing of enriched live food organisms is therefore necessary after their harvest and before they are introduced to larval culture tanks. The enrichment process is generally kept as short as possible to minimise bacterial load within enrichment vessels.

9.2.15 Copepods

Copepods occur in all aquatic systems and are natural prey for virtually all fish larvae. There are over 10 000 known species, with most planktonic forms ranging between 0.5 mm and 2.5 mm in size. Given their importance as prey for wild fish larvae, there is clear potential for the use of copepods in aquaculture and research with fish has shown that when copepods are included in the larval diet, survival, growth rates, pigmentation and gut development are all improved.

Developments in this field were recently reviewed by Dhont and Dierckens (2013). Research has focused primarily on the harpacticoid and calanoid copepods:

- Harpacticoid copepods (Figure 9.10) are distinguished by a very short pair of 1st antennae with biramous 2nd antennae and a joint between the 4th and 5th body segments. They are generally epibenthic.

- Calanoid copepods (Figure 9.11) are distinguished by 1st antennae that are at least half the body length with biramous 2nd antennae and a joint between the 5th and 6th body segments. They are generally pelagic.

Figure 9.10 Harpacticoid copepod adult female with eggs (right) and nauplius (left).

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr T. Camus.

Figure 9.11 Calanoid copepod (Parvocalanus sp.) female.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Dr T. Camus.

Most copepods reproduce sexually with eggs being released directly into the water column (calanoids) or nauplii hatching directly from egg sacs (harpacticoids and cyclopiods). Nauplii develop through six stages, separated by moults, before reaching the copepodite stage that resembles the adult. The copepodite goes through a futher six moults before becoming an adult. The small size of newly hatched nauplii is appropriate for the larvae of fish with small mouth gape (Figure 26.9) but copepods can be used as a live food in aquaculture hatcheries at the nauplius, copepodite and adult stages, depending on the mouth size of the target larvae.

Copepods are readily digested by fish larvae and are superior to rotifers and brine shrimp in their nutritional value. In particular, they contain high levels of n‐3 HUFA and a wide range of copepod species have been used as food for marine fish larvae (see section 20.3.1.4; Table 9.6). Nauplii and copepodites of calanoid copepods are valuable dietary components for a wide range of marine fish species including flatfish such as halibut and flounder, for which they are a preferred first food for larvae supporting enhanced development, pigmentation and improved survival (section 20.13). However, much of our knowledge of the nutritional value of copepods is based on small‐scale (experimental) culture and, where copepods are used as a larval food on a larger scale, they are often obtained serendipitously from blooms in local water bodies or from blooms in dedicated ponds following fertilisation (section 9.7).

Table 9.6 Some copepods used as food for fish larvae.

| Type | Species | Type | Species |

| Calanoid | Acartia clausi | Harpacticoid | Euterpina acutifrons |

| Acartia tonsa | Nitokra lacustris | ||

| Acartia sinjiensis | Tigriopus japonicus | ||

| Acartia tsuensis | Tigriopus californicus | ||

| Acartia tranteri | Tigriopus brevicornis | ||

| Centropages spp. | Tisbe furcata | ||

| Eurytemora affinis | Tisbe holothuriae | ||

| Gladioferens imparipes | Amphiascoides atopus | ||

| Paracalanus sp. | |||

| Parvocalanus sp. | |||

| Pseudocalanus sp. | |||

| Pseudodiaptomus spp. | |||

| Temora spp. |

9.2.15.1 Copepod Culture

Culture of copepods and their use as live prey in aquaculture was reviewed by Lee et al. (2005). Copepods used as live foods in aquaculture are commonly produced in extensive or semi‐extensive outdoor culture systems such as ponds or lagoons. The ponds are filled with crudely filtered (to 40 µm) sea water to which fertilisers are added to promote a bloom of local microalgae. Once the bloom is established, copepods obtained from filtering local sea water are added to the ponds, providing a mixture of species (and sizes) that will proliferate within the ponds. Copepod densities of 300/L to more than 1000 nauplii/L are possible in such systems. Fish larvae are generally stocked into the ponds at relatively low densities once good copepod populations have become established. For more information about pond fertilisation as a means of live food production see section 9.7.

Copepods are generally difficult to mass culture in intensive culture systems that are characterised by variable and unreliable production. The productivity of such systems is influenced by factors such as cannibalism (e.g., Acartia spp.) and appropriate system design for epibenthic species. The challenge remains to develop, cost‐effective large‐scale copepod production methods that can match those used for traditional live prey organisms (rotifers and Artemia). Approximately 60 copepod species have been successfully cultured. Maximum densities of cultivated calanoid copepods with potential in aquaculture are ca. 100–2000 adults/L although cyclopoid copepods may achieve densities of ca. 5000/L. Most harpacticoids can be grown at relatively high densities (ca. 10 000 to 400 000/L) in high volume systems incorporating three‐dimensional structures. Production of up to 8.2 million nauplii/day was reported for a 266 L system holding Nitokra lacustris.

Calanoid Culture

Calanoids have limited tolerance to high density culture with cannibalism resulting from increased encounters between individuals. This can be minimised by separating nauplii from adults during culture. Basic culture parameters for Acartia tonsa are shown in Table 9.7. These are based on a continuous production system consisting of three culture units: basis tanks, growth tanks and harvest tanks, and the parameters shown are those in the basis tanks. In this system, 10 L of culture water (containing eggs) is siphoned from the bottom of the basis tank and replaced by clean filtered sea water. The eggs contained in the siphonate are retained on a 40 µm mesh and transferred to the growth tank where maximal density may reach 6000 eggs/L. Nauplii hatch after 24 hours and the microalgae Isochrysis is provided at a density of 1000 cell/mL, increasing to 1500 cells/mL after 10 days with the addition of a second microalgae, Rhodomonas. The time required to reach 50% fertilised female copepods in the growth tank (generation time) is about 20 days when adults are collected using a 180 µm mesh and transferred to either newly established basis tanks, for the production cycle to begin again, or to the harvest tanks for use as a larval food. Production from basis tanks can be around 95 000 eggs/day or 25 eggs/female/day. Basis tanks are emptied and cleaned 2–3 times a year.

Table 9.7 Culture parameters used for the calanoid copepod (Acartia tonsa) and the harpacticoid (Tigriopus sp.).

Source: Data from Lavens and Sorgeloos (1996).

| Culture Parameter | Calanoid | Harpacticoid |

| Tank: | 200 L (1500 × 50 cm) | 500 L |

| Water: | 1‐µm filtered, 35 ‰ | 1‐µm filtered, 35‰ |

| Watyer system: | Batch (5 % change/day) | Semi flow‐through |

| Temperature: | 16–18°C | 24–26 °C |

| Stocking density | <100/L | 20–70/mL |

| Female:Male ratio | 1:1 | Stocked with gravid females |

| Aeration | Gentle | Gentle |

| Food type | Microalgae (Rhodomonas) | Chaetoceros gracilis or green flagellate |

| Food ration | 8 × 108 cells/day | 5 × 104–2 × 105 cells/mL |

Harpacticoid Culture

Harpacticoid copepods are generally considered to have a number of characteristics that are well suited to aquaculture production including:

- high fecundity and short generation time;

- acceptance of a wide variety of foods including rice bran, yeast and microalgae;

- ability to achieve high density in culture (e.g., Tigriopus fed on rice bran increased in density from 0.5/mL to 9.5/mL in 12 days); and

- broad environmental tolerance such as a salinity range of 15–70 mg/L and temperature range of 17–30 °C.

Basic culture parameters for Tigriopus sp. are shown in Table 9.7. The culture is based on 10–100 gravid females that are used to inoculate culture tanks and will support a population growth rate of around 15% per day to an optimal stocking density of 20–70 copepods/mL. The generation time is around 8–11 days. Early nauplii can be collected from the culture tank using a 37 µm mesh and copepodites can be collected on a 100 µm mesh.

It is likely that copepods will assume increasing importance as a hatchery food, as more reliable mass‐culture techniques are developed, and more species are investigated for their culture potential.

9.3 Feeding Strategy for Larval Culture

9.3.1 Feeding Protocols

A generalised feeding protocol for marine fish larvae begins with rotifers at first feeding followed by brine shrimp nauplii and larger brine shrimp as larvae increase in size (Figures 9.12 and 26.10). Formulated diets are then introduced and larvae are weaned from live food organisms. Fish hatcheries also culture microalgae as a food source for rotifers and brine shrimp and, as such, they generally culture three different live foods to feed the larvae of a single target species. Excellent coverage of the practical use of live feeds and microdiets in marine fish hatcheries is provided in Chapter 20. Shrimp hatcheries generally begin feeding with microalgae (usually a diatom such as Chaetoceros species), which are usually followed by rotifers and brine shrimp or just brine shrimp as the larvae grow. Bivalve hatcheries rely exclusively on cultured microalgae as a larval food source.

Figure 9.12 A generalised feeding protocol for marine fish larvae begins with rotifers at first feeding followed by brine shrimp nauplii and larger brine shrimp as larvae increase in size. Larvae are then weaned to artificial formulated feeds.

Source: Southgate and Partridge 1998. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

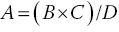

The volume of a microalgae, rotifer or brine shrimp culture that has to be added to larval rearing tanks to obtain the desired density of food organisms is calculated as:

where A is the required volume (L) of the live food culture; D is the density of the live food culture (number/mL); B is the required density of microalgae, rotifers or brine shrimp in the larval tank (number/mL); and C is the volume of the larval tank (L).

The feeding regimen is an important aspect of hatchery management. Overfeeding is wasteful and expensive. It also compromises water quality, which can lead to disease and affect larval performance. Underfeeding reduces growth rates, thereby increasing hatchery running costs. It is important to monitor the presence of food in larval tanks to avoid these problems.

9.3.2 Some Disadvantages of Live Feed Organisms

A number of disadvantages are common to intensive culture of microalgae, rotifers and brine shrimp. Some of these have been outlined for microalgae production in section 9.2.5, but they also apply to rotifer and brine shrimp production. Other potential problems relating specifically to rotifers and brine shrimp are listed in Table 9.5. In response to these potential problems, particularly the high costs associated with live food culture, there has been considerable research and commercial interest in developing compound or formulated hatchery feeds, sometime called microdiets, microfeeds or weaning diets, as alternatives to live foods. Characteristics and potential of these feeds used with fish larvae was reviewed by Kolkovski (2013).

9.4 Compound Hatchery Feeds

9.4.1 Advantages

The high cost of live food production in aquaculture hatcheries could be reduced by cheaper production of live foods and earlier weaning to formulated feeds in the case of crustaceans and fish. Complete or significant replacement of live foods would considerably reduce hatchery running costs and provide ‘off‐the‐shelf’ convenience and nutritional consistency. Perhaps the greatest potential advantage of appropriate compound larval diets is that, unlike live foods, the size of the food particle and diet composition can be adjusted to suit the exact nutritional requirements of the larvae. However, they must satisfy a number of criteria (Table 9.8).

Table 9.8 Desired characteristics of compound feeds for aquatic larvae.

| Characteristic | Comments |

| Acceptability | Must be attractive and readily ingested. Diet particles must be of suitable size for ingestion and must elicit a feeding response from the larvae. Diet particles must remain available in the water column |

| Stability | Diet particles must maintain integrity in aqueous suspension and nutrient leaching must be minimal. Some nutrient leaching may be beneficial in enhancing diet attractability |

| Digestibility | Diet particles must be digestible and their nutrients easily assimilated |

| Nutrient composition | Diets must have an appropriate nutritional composition. Material added to the diet as binders or the components of microcapsule walls must have some nutritional value |

| Storage | Diets must be suitable for long‐term (6–12 months) storage with nutrient composition and particle integrity remaining stable |

Various materials have been assessed for their potential to replace live microalgae as a food for bivalves. These include dried and concentrated microalgae (section 9.2.5), dried and pulverised macroalgae, yeasts and cereal products (Knauer and Southgate, 1999). They also include compound or formulated diets, known generically as microdiets, that encompass microbound diets, microencapsulated diets, microcoated diets and diet particles manufactured using microextrusion marumerisation (Knauer and Southgate, 1999; Kolkovski, 2013). Although dried microalgae have also been used in the culture of crustacean and fish larvae, much of the research to develop alternatives to live feeds has focused on microdiets.

9.4.2 Microbound Diets

In microbound diets (MBD), nutrients (both particulate and dissolved) are bound within a particle matrix consisting of a binding material such as agar, gelatin, alginate or carrageenan. Dietary ingredients are mixed with the binder to form a slurry, which is then dried, ground and sieved to produce food particles of the desired size. MBD allow precise manipulation of dietary contents and, for this reason, have been used extensively in research to determine nutritional requirements of larvae, particularly crustacean larvae (e.g., Holme et al., 2009). However, because MBD particles have no barrier between dietary ingredients and the culture water, there is potential for nutrient leaching and they are susceptible to direct bacterial attack.

9.4.3 Microencapsulated Diets

Microencapsulated diets (MED) consist of dietary materials enclosed within a microcapsule wall or membrane. This greatly reduces nutrient leaching and the susceptibility of the diet to bacterial attack. MED have been used with some success as a replacement for microalgae for bivalve larvae and juveniles (Knauer and Southgate, 1999). MED and other microdiets have been commercially available for shrimp larvae for a number of years and are widely used in shrimp hatcheries (section 22.6.3). It is generally accepted that a combination of microdiet and live feeds, a practice known as co‐feeding, supports superior growth and survival of shrimp larvae than either feed alone. However, it is now possible to completely replace live feeds with microdiets in penaeid shrimp hatcheries. The development and use of formulated diets for crustacean larvae was reviewed by Holme et al. (2009). Despite the development of successful artificial diets for shrimp larvae and their routine use in shrimp hatcheries, similar success has not been achieved with fish larvae.

9.4.4 Microcoated Diets

Microcoated diets (MCD) are primarily composed of MBD particles that are coated with lipids or lipoproteins to reduce nutrient leaching from the food particles.

9.4.5 Microextrusion Marumerisation Diets

Microextrusion marumerisation (MEM) diet particles are prepared by processes such as spray‐drying, fluidised bed drying and particle‐assisted rotational agglomeration, and a number of commercially‐available hatchery feed products are produced using these methods. These processes can be used to manufacture diet particles covering a size range of 50‐1000 µm and containing a broad range of nutrients.

9.5 Development of Microdiets for Fish Larvae

9.5.1 Limited Success

Numerous studies have been conducted to assess the nutritional value of microdiets for marine fish larvae. In general, they have resulted in lower survival and poorer growth of larvae than those fed live foods and they often lead to a higher incidence of deformity. These results indicate that total replacement of live prey with artificial diets is still not possible for the larvae of most marine fish (Kolkovski, 2013). Despite this, partial replacement of live foods can result in cost savings, and some studies have shown that between 50% and 80% of a live feed ration can be replaced with a microdiet without affecting larval growth. Weaning fish larvae to a formulated diet at the earliest possible age is another means of reducing feed costs and is a major goal for commercial fish hatcheries (section 20.3.1.5). It has been estimated that weaning European bass 15 days earlier enables savings in brine shrimp production of up to 80%.

9.5.2 Constraints to Developing Microdiets for Marine Fish Larvae

The relatively poor performance of formulated diets in studies with marine fish larvae is thought to result primarily from reduced rates of ingestion and poor digestion.

Successful formulated diets must be ingested at a similar rate to live foods. This is a particular problem with carnivorous fish larvae, which require the visual stimulus of moving prey to initiate a prey capture response. Attempts to overcome or reduce this problem have included:

- inclusion of various chemicals (using light refraction) into diet particles to impart a sense of motion;

- incorporation of food dyes into diets to simulate the colour of brine shrimp nauplii; and

- use of amino acids that naturally emanate from live food organisms to enhance larval feeding response. They act as feed attractants and may be incorporated into artificial diets to improve attractability.

Most marine fish larvae are poorly developed at hatch, and in many species the digestive tract does not develop fully until they are early juveniles. Marine fish larvae also have low gut enzyme activity compared to adult fish and, again, secretion of some enzymes begins in early juveniles when a functional stomach is present. Marine fish larvae generally improve in their ability to digest artificial food particles with age. Live food organisms consumed by larvae assist digestion by donating their digestive enzymes either by autolysis or as zymogens, which activate endogenous digestive enzymes within the larval gut. Inclusion of digestive enzymes (particularly proteases) in artificial diets has been shown to improve nutrient assimilation by up to 30%, resulting in superior larval growth. Similarly, inclusion of digestive system neuropeptides in microdiets may also improve nutrient assimilation and growth.

9.5.3 Weaning Diets

Larvae reared on live feeds during the hatchery phase require weaning to formulated feeds towards the end of the larval period (Figure 9.12; section 20.3.1.5). The weaning process usually involves providing live feeds together with formulated food particles over a period when the live feed component of the diet is gradually reduced and the formulated component is increased. The duration of the weaning process varies, but weaning is usually completed within 30 days. A wide variety of weaning diets are available commercially in the form of MBD, MED, MEM, flake diets, crushed pellets (crumbles) and yeast‐based diets. Development of successful formulated diets for fish larvae would eliminate the need to wean larvae from live to formulated foods becaues larvae could simply be fed larger food particles as they grow.

9.5.4 Use of Microdiets in Hatcheries

Formulated microdiet particles are negatively buoyant and this presents problems maintaining food particles in suspension. This may reduce the availability of food to the larvae, and food particles that settle at the bottom of larval culture tanks may pollute culture water and enhance bacterial activity. In contrast, live foods generally remain motile in larval culture tanks and this maximizes their availability to larvae and reduces contamination of the culture water from uneaten food. Tank design and aeration systems are important in maximizing microdiet particle buoyancy and for maintaining particle movement. The use of microdiets requires careful consideration of tank design and aeration, and regular monitoring of feeding rates. Adding small quantities of food a number of times per day optimises water quality and maximises the food available to the larvae.

9.5.5 Further Development of Formulated Hatchery Feeds

As described above, use of commercially produced microdiets is commonly practiced in shrimp hatcheries (section 22.6.3). However, the situation is not as good for marine fish and bivalve hatcheries. Although both fish and bivalve larvae have developed to the early juvenile stage when fed microdiets under laboratory conditions, commercial fish and bivalve hatcheries still rely on live food production for the majority, if not all of the larval culture period. This situation is now changing for bivalves where there is increasing hatchery use of commercially‐available microalgae concentrates (section 9.2.5.1); however, development of formulated hatchery feeds or microdiets for fish and bivalves has been hindered by our lack of knowledge of their nutritional requirements, and by problems relating to the attractability and digestion of formulated food particles and their use in culture systems. Development of more suitable formulated feeds for marine fish larvae will require further research in the following areas:

- improved ingestion and digestion of artificial diets;

- greater understanding of the nutritional requirements of larval stages; and

- development of more appropriate culture system designs.

The potential cost savings offered by the use of suitable formulated diets will ensure that research in this field is ongoing.

9.6 Harvesting Natural Plankton

Natural sources of zooplankton represent a large, relatively untapped, potential food source for aquaculture hatcheries. A large portion of this plankton is composed of copepods, which can occur naturally at densities up to 10 000 per cubic metre. Utilising this potential food source requires efficient extraction of zooplankton from very large volumes of water. This can be achieved by pumping water through sieves that collect zooplankton. Plankton harvesting machines have been developed that harvest and grade plankton by size. One of the drawbacks of harvesting from natural waters is that plankton densities may vary between locations and, as such, the reliability of the food supply is questionable. However, this may be overcome by harvesting from dedicated plankton ponds in which high plankton loads can be encouraged by fertilisation. The use of harvested natural zooplankton as a food source for aquaculture is not widespread; however, the variety of organisms composing natural zooplankton would undoubtedly provide a nutritionally superior diet to the standard rotifers/brine shrimp diets used routinely in aquaculture hatcheries.

9.7 Pond Fertilisation as a Food Source for Aquaculture

Extensive and semi‐intensive pond culture of herbivorous and omnivorous species is usually based on food production through pond fertilisation (section 2.3). Fertilisation of ponds for semi‐intensive culture of tilapia, for example, is outlined in detail in section 18.7.3. Although this system is more commonly used for grow‐out, pond fertilisation has also been used successfully for larval fish culture (section 9.7.3 and Chapter 20). The fertilisers used for this purpose may be inorganic or organic in nature, or a combination of both.

9.7.1 Fertilisers

Inorganic fertilisers are chemical fertilisers that contain at least one of the primary nutrients nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K). Commercially‐available agricultural fertilisers such as ammonium sulphate and superphosphate are widely used in aquaculture. Animal manures are probably the commonest organic fertilisers used in aquaculture, although decomposed plant materials are also widely used. Use of organic fertilisers in aquaculture is an ancient practice and is an economical means of increasing production in aquaculture ponds. There is greater reliance on organic fertilisers in developing countries as they are more readily available than chemical fertilisers. They are also more economical to use and more efficient if pond culture is integrated with crop or animal production. In developing countries, terrestrial and aquatic animals (usually fish) are often reared together in integrated systems (section 2.4). Readers are directed to Chapter 4 (section 4.4.2) for more information about the chemical fertlisers used in aquaculture.

9.7.2 Production in Fertilised Ponds

Fertilisation encourages primary productivity and promotes a succession of organisms within the pond. Initially, fertilisation results in blooms of protozoa and bacteria, which are generally followed by blooms of algae and then zooplankton. The natural food organisms present in ponds consist of:

- bacteria and protozoans

- plants (phytoplankton, periphyton, macrophytes)

- animals (mainly invertebrates: zooplankton, zoobenthos, small nekton)

- fish.

Fertilisation increases the biomass of potential food organisms present in a pond. For example, zooplankton levels of <0.055 g/m3 and 3.3424 g/m3 have been reported in non‐manured and manured ponds, respectively.

Ecological conditions within a pond determine which organisms are present, the proportion of each and their abundance. All the listed organisms in the pond form the biocenosis (self‐regulating ecological community) of the pond, which therefore contains all potential food sources for cultured organisms. However, a given species will only feed on a certain portion of the biocenosis and this is dictated by its feeding habit (e.g., carp species; Figure 2.4). The specific portion of the biocenosis consumed by an organism is its trophic basis, and the trophic basis of a particular species may differ during its life cycle, e.g., the larvae of many herbivorous fish consume zooplankton.

The finite biomass of natural food in a pond can only support a finite standing crop of animals under culture. When the standing crop is low, the amount of available food exceeds the requirements of the culture population and so each animal is able to find sufficient food to support its energy requirement for maintenance and maximum growth. However, an increase in the culture population brings about an increase in their food requirement. At a certain population density, the amount of food required by the culture population for maintenance and growth exceeds that available in the pond. Since the maintenance requirement must be satisfied, the amount of food energy that can be utilised for growth is reduced and growth rates decline as a result. This standing crop is termed the critical standing crop (CSC). A continued increase in the standing crop further limits the amount of food that can be utilised for growth, and the point at which the natural food available in the pond is sufficient to support only the maintenance energy requirement of the culture crop is known as the carrying capacity of the pond. Fertilisation increases the CSC and carrying capacity of a pond, and growth rates of the culture population can only be increased above these levels if supplementary feed is added to the pond (Table 9.9).

Table 9.9 The effect of fertilisation and supplemental feeding on critical standing crop and carrying capacity of freshwater ponds.

Source: Reproduced from Hepher (1988) with permission from Cambridge University Press.

| Treatment | Critical standing crop (kg/ha) | Carrying capacity (kg/ha) |

| No feeding, no fertilisation | 65 | 130 |

| No feeding, fertilisation | 140 | 480 |

| Feeding and fertilisation | 550 | 2500 |

Supplementary feeds are generally classified into simple feeds and compound (or compounded) feeds. Simple feeds may be of animal origin (e.g., trash fish, slaughterhouse waste and fishmeal), or of plant origin (e.g., forage, oil meals, rice bran and sorghum). Many simple feeds are relatively cheap agricultural by‐products. The simple feeds used by a given aquafarm are dictated by what is locally available. As would be expected, the nutritional composition of simple feeds varies greatly. Those of plant origin are usually rich in carbohydrate, whereas others, such as oil meals and animal products, are rich in protein. Compound feeds consist of mixtures of ingredients that are commonly bound together to form doughs or pellets.

An aquaculture system that utilises supplementary feeds is classed as semi‐intensive (section 2.2), and the densities of culture animals are higher than in equivalent extensive systems that rely on natural foods alone. In many developing countries, however, the use of supplementary feeds may not be feasible because it raises the cost of production. These countries may also have a limited capability to manufacture or import compound feeds.

9.7.3 Pond Culture of Fish Larvae

Freshwater and marine/estuarine species can be reared extensively in earthen ponds with blooms of natural plankton as their food source. The larvae of barramundi (Lates calcarifer) are a good example of larvae that may be reared in this manner. This method has proved to be very successful, and achieves ca. 50% survival through larval rearing and growth rates greater than those achieved using intensive culture systems. Other examples of pond culture of fish are provided in Chapter 20 and further information on establishing copepod culture as a basis for pond culture of marine fish larvae is provided in section 9.2.15.

9.8 Summary

- Cultured live microalgae has a central role in aquaculture hatcheries where it is used as a food for all stages of bivalve molluscs, for some crustacean and fish larvae, and for rotifers and Artemia that are themselves used as live foods for fish and crustacean larvae. Recent developments include potential for replacing live microalgae with commercially‐available microalgae concentrates.

- Rotifers and Artemia are the major live foods used for crustacean and fish larvae in aquaculture hatcheries. Both are deficient in essential fatty acid content and this must be corrected using enrichment procedures prior to feeding to larvae.

- Copepods have superior nutritional value to rotifers and Artemia and are well suited as a food for fish larvae with small mouth gapes. Broader use of copepods as a live food in aquaculture hatcheries is hampered by difficulties in intensive culture systems, that are characterised by variable and unreliable production. It is likely that copepods will assume increasing importance as a hatchery food as more reliable mass‐culture techniques are developed and more species are investigated for their culture potential.

- Potential problems with production and use of live foods in aquaculture hatcheries (microalgae, rotifers, Artemia and copepods) include high cost, technical and infrastructure requirements, nutritional inconsistency and deficiency, and the potential for live food to become vectors for contamiantion and disease introdcution to larval cultures.

- Potential alternatives to hatchery‐based culture of live food organisms include dried and concentrated microalgae, yeast‐based food particles and various formulated microdiets. Advances have been made with shrimp larvae that can be culture on microdiets without live foods, and with bivalve mollusc larvae that can be cultured using microalgae concentrates. However, culture of fish larvae still relies on live foods. Development of formulated microdiets for fish larvae is hampered by lack of knowledge of their nutritional requirements and poor rates of ingestion and digestion of microdiet particles.

- Live food organisms for larval culture can be harvested from natural water bodies or encouraged by fertilisation of dedicated ponds and embayments. Extensive culture of copepods and other live food organisms in ponds used to culture fish larvae is well established, and can be very successful with careful management of the plankton population and stocking density of the target species.

References

- Arimoro, F. O., 2006. Culture of the freshwater rotifer, Brachionus calicyflorus, and its application in fish larviculture technology. African Journal of Biotechnology.5 (7): 536–541.

- Brown, M. R., Jeffrey, S. W. & Garland, C. D. (1989). Nutritional Aspects of Microalgae Used in Mariculture: A Literature Review. CSIRO Marine Laboratories report 205. CSIRO, Hobart.

- Brown, M.R., Blackburn, S.I. 2013. Live microalgae as feeds in aquaculture hatcheries. In: Allan, G. and Burnell, G. (Eds). Advances in aquaculture hatchery technology. Woodhead Publishing, Oxford. 117–156.

- Dhont, J. & Dierckens, K. 2013. Rotifers, Artemia and copepods as live feeds for fish larvae in aquaculture. In: Allan, G. & Burnell, G . (Eds), Advances in aquaculture hatchery technology, Woodhead Publishing, Oxford. pp. 157–202.

- Dhont, J. & Van Stappen, G. 2003. Biology, tank production and nutritional value of Artemia. In: Stottrup, J.G. & McEvoy, L.A. (Eds), Live Feeds in Marine Aquaculture. Blackwell Science, Oxford. pp. 65–121.

- Duy, N.D.Q., Francis, D.S., Southgate, P.C. 2017. The nutritional value of live and concentrated micro‐algae for early juveniles of sandfish, Holothuria scabra. Aquaculture, 473, 97–104.

- Hepher, B. (1988). Nutrition of Pond Fishes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Holme, M., Zeng, C. and Southgate, P.C. 2009. A review of recent progress towards development of formulated microbound diet for mud crab, Scylla serrata, larvae and their nutritional requirements. Aquaculture 286, 164–175.

- Jeffrey, S. W., Leroi, J. M. & Brown, M. R. (1992). Characteristics of microalgal species needed for Australian mariculture. In: Proceedings of the Aquaculture Nutrition Workshop (Ed. by G. L. Allan & W. Dall), pp. 164–173. NSW Fisheries, Australia.

- Knauer, J. & Southgate, P. C. (1999) A review of the nutritional requirements of bivalves and the development of alternative and artificial diets for bivalve aquaculture. Reviews in Fisheries Science, 7, 241–280.

- Kolkovski, S. 2013. Microdiets as alternatives to live feeds for fish larvae in aquaculture: improving the efficiency of feed particle utilisation. In: Allan, G. and Burnell, G. (Eds). Advances in aquaculture hatchery technology. Woodhead Publishing, Oxford. 203–245.

- Lavens, P., Sorgeloos, P. (Editors) 1996. Manual on the production and use of live food for Aquaculture. FAO Fisheries technical paper 361. FAO, Rome. 295 pp.

- Leger, P. (1999). The Artemia crisis…. and solutions, poor yields at the Great Salt Lake. The Advocate, December 1999, 79–82.

- Lee, C.S., OBryen, P.J., Marcus, N.H. 2005. Copepods in Aquaculture. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

- Parsons, T. R., Stephens, K. & Strickland, J. D. H. (1961). On the chemical composition of eleven species of marine phytoplankters. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 18, 1001–1016.

- Reed, T. & Henry, E. (2014). The case for concentrates. Hatchery International, 15(4), 24–25.

- Southgate, P. C. & Partridge, G. J. (1998). Development of artificial diets for marine finfish larvae: problems and prospects. In: Tropical Mariculture (Ed. by S. DeSilva), Academic Press, London. pp. 151–169.

- Southgate, P.C., Beer, A.C. & Ngaluafe, P. (2016). Hatchery culture of the winged pearl oyster, Pteria penguin, without living micro‐algae. Aquaculture, 451, 121–124.

- Utting, S. D. (1986). A preliminary study on growth of Crassostrea gigas larvae and spat in relation to dietary protein. Aquaculture, 58, 123–138

- Whyte, J. N. C. (1987). Biochemical composition and energy content of six species of Phytoplankton used in mariculture of bivalves. Aquaculture, 60, 231–241.

- Volkman, J. K., Jeffrey, S. W., Nichols, P. D., Rogers, G. I. & Garland, C. D. (1989). Fatty acid and lipid composition of 10 species of microalgae used in mariculture. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 128, 21940.