STEP

12

Applying

Program Design

Principles

This step will help you understand the logic of designing a well-conceived weight training program. If you have trained before, the information provided here will give you a chance to determine how well your previous program followed recommended training principles. The elements of exercise selection, exercise arrangement, loads, repetitions, sets, length of rest period, and training frequency—collectively referred to as program design variables—are the foundation on which effective weight training programs are built. These seven variables are grouped into the following three sections of this step:

1. Select and arrange exercises

2. Manipulate training loads, number of repetitions, number of sets, and the length of rest periods

3. Decide training frequency

Just as certain ingredients in your favorite meals must be included in proper amounts and at the correct time, so too must the sets, repetitions, and loads in your workouts. The workout recipe, referred to as the program design, is what ultimately determines the success of your weight training program (along with your commitment to training). The exciting thing about learning about program design variables is that, once learned, you can then design your own program.

SELECT AND ARRANGE EXERCISES

The exercises you select will determine which muscles become stronger, more enduring, and thicker. In addition, how you arrange, or order, the exercises in your program will affect the intensity of your workouts.

Selecting Exercises

An advanced program may include as many as 15 to 20 exercises. However, a beginning or basic program (which is what you are following) need only include one exercise for each muscle group:

chest (pectoralis major)

shoulders (deltoids)

back (latissimus dorsi, trapezius, rhomboids)

biceps (biceps brachii)

triceps (triceps brachii)

legs (quadriceps, hamstrings, gluteals)

core (rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, external and internal obliques, erector spinae)

In steps 4 through 9, you selected one exercise for each muscle group if you were new to weight training and one more *additional exercise if you were trained. You can now consider adding a second exercise for each muscle group or an exercise for a muscle not specifically worked in the basic program, such as the forearm. The result is an even more rounded program.

Also, if you are training to improve your athletic performance, consider adding one or both of the total-body exercises described in step 10. They train upper and lower body muscles simultaneously and involve quick, powerful movements that are important for athletes involved in sports such as sprinting, jumping, throwing, kicking, or punching.

Finally, you may also want to consider exchanging one of the basic exercises for one of the others described in each step, especially if the change means you will now perform a free-weight version of a machine-based exercise. Before making a final decision about which exercises to select, be sure you understand the exercise techniques involved and the following concepts and principles.

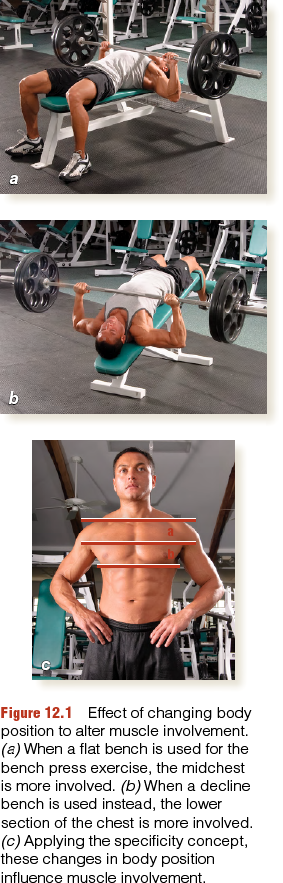

Apply the specificity concept. Your task is to identify the muscle groups you want to develop and then determine which exercises will recruit or use those muscles. This involves applying the specificity concept. This important concept refers to training in a manner that will produce outcomes specific to that method. For example, developing the chest muscles requires an exercise that recruits the pectoralis major muscle; choosing a leg exercise to train the chest muscles, for example, does not follow the specificity concept because muscles other than the pectoralis major are trained.

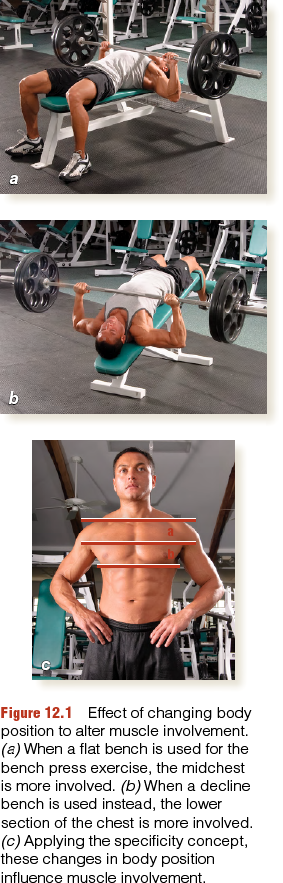

Even the specific angle at which muscles are called into action determines if, and to what extent, they will be stimulated during an exercise. For example, figure 12.1 illustrates how a change in body position changes the angle at which the barbell is lowered and pushed upward from the chest. The angle of the bar’s path dictates whether the middle or lower portion of the chest muscles becomes more or less involved in the exercise.

The type and width of the grip are as important as body position because they, too, change the angle at which muscles become involved and thus affect the training results. For example, using a wide grip for the bench press exercise places a greater stress on the chest muscles than using a narrow grip. That is why performing exercises exactly as they are described is so important.

Create muscle balance. It is important to select exercises that create strong joints, a proportional physique, and good posture. A common method is to choose exercises that train opposing muscle groups or body-part areas such as:

– Chest and upper back

– Front of the upper arm (biceps) and back of the upper arm (triceps)

– Front (palm side) of the forearm and back (knuckle side) of the forearm

– Abdomen and low back

– Quadriceps and hamstrings

– Front of the lower leg (shin) and back of the lower leg (calf)

Know what equipment is available. Determine the equipment needs for each exercise before making a final decision. You may not have the needed equipment to perform an exercise.

Determine if you need a spotter. Is a spotter needed for an exercise you are considering adding to your program? If one is needed but is not available, choose a different exercise that trains the same muscle group.

Know how much time you have to train. The more exercises you decide to include in your program, the longer your workouts will take. It is a common mistake to choose too many exercises! Plan for approximately two minutes per set unless you want a program that is designed to develop strength. If strength is your goal, you’ll need to plan on about four minutes per set because the rest period is longer between sets and exercises. Also, the more sets you want to do, the longer the workout will last. This is discussed in greater detail later in this step.

Arranging Exercises

There are many ways to arrange exercises in a workout. Their order affects the intensity of training and is therefore an important consideration. For instance, alternating upper- and lower-body exercises produces a lower intensity level on the upper body or the lower body muscles than performing all of the upper-body exercises or all of the lower-body exercises one after the other.

Exercises that train larger muscles and involve two or more joints changing angles as the exercises are performed are called multijoint exercises (abbreviated as “MJEs” throughout this book). This type of exercise is more intense than those that isolate one muscle and involve movement at only one joint (called single-joint exercises and abbreviated as “SJEs”). The two most common ways to arrange these exercises are to either perform MJEs before SJEs or alternate exercises that involve a pushing (PS) movement with exercises that involve a pulling (PL) movement.

Perform MJEs before SJEs. Performing all of the MJEs before the SJEs is a well-accepted approach. For example, rather than training the triceps with the triceps extension (a SJE) and then the chest with the bench press (a MJE), it is recommended that you perform the bench press exercise first. Note that although the overall size of the upper arm can appear to be large, the front and back of the arm are considered separate, smaller muscle groups. An example of the sequence for performing MJEs before SJEs is shown in table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Exercise Arrangement: MJEs First

| Exercise |

Type |

Muscle group |

| %Lunge |

MJE |

Legs (thigh and hip) |

| %Bench press |

MJE |

Chest |

| %Lat pulldown |

MJE |

Back |

| %Triceps extension |

SJE |

Back of the upper arm |

| %Biceps curl |

SJE |

Front of the upper arm |

| %Standing heel raise |

SJE |

Calf |

Alternate PS exercises with PL exercises. You may also arrange exercises so that those that extend (straighten) joints alternate with those that flex (bend) joints. Extension exercises require you to push, whereas flexion exercises require you to pull—thus the name of this arrangement is to alternate PS with PL. An example is to perform the triceps extension (a PS exercise) followed by the biceps curl (a PL exercise). This is a good arrangement because the same muscle or body area is not trained back-to-back; that is, the same muscle group is not worked two or more times in succession. This arrangement should give your muscles sufficient time to recover. An example of this method of arranging exercises is shown in table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Exercise Arrangement: Alternate Push (PS) With Pull (PL)

| Exercise |

Type |

Muscle group |

| %Bench press |

PS |

Chest |

| %Lat pulldown |

PL |

Back |

| %Seated press |

PS |

Shoulder |

| %Biceps curl |

PL |

Front of the upper arm |

| %Triceps extension |

PS |

Back of the upper arm |

| %Knee curl |

PL |

Legs (back of the thigh) |

| %Knee extension |

PS |

Legs (front of the thigh) |

There are two more exercise arrangement options that need to be considered because they affect the intensity of your workout.

Sets performed in succession versus alternating sets. When you are going to perform more than one set of an exercise, you will need to decide if you will perform them one after another (in succession) or alternate them with other exercises. The following shows an example of two exercises performed for three sets in succession and alternated:

– In succession: Shoulder press (set 1), shoulder press (set 2), shoulder press (set 3); biceps curl (set 1), biceps curl (set 2), biceps curl (set 3)

– Alternated: Shoulder press (set 1), biceps curl (set 1), repeated until three sets of each exercise are performed

In each of these arrangements, three sets of the shoulder press and the biceps curl exercises are performed, each with a different intervening rest period and activity. Most people prefer the in-succession arrangement because it provides a greater (and more challenging) training effect.

Triceps and biceps exercises after other upper-body exercises. When arranging exercises in your program, be sure that a triceps exercise is not performed before other pushing exercises such as the bench press or the shoulder press. These two MJEs rely on assistance from elbow-extension strength from the triceps muscles. When triceps exercises precede pushing chest or shoulder exercises, they fatigue the triceps and reduce the number of repetitions that can be performed and the desired effect on the chest or shoulder muscles. The same logic applies to biceps exercises. Pulling exercises that involve flexion of the elbow, such as the lat pulldown, depend on strength from the biceps muscles. Performing the biceps curl before the lat pulldown will fatigue the biceps and reduce the number of lat pulldown repetitions that can be performed.

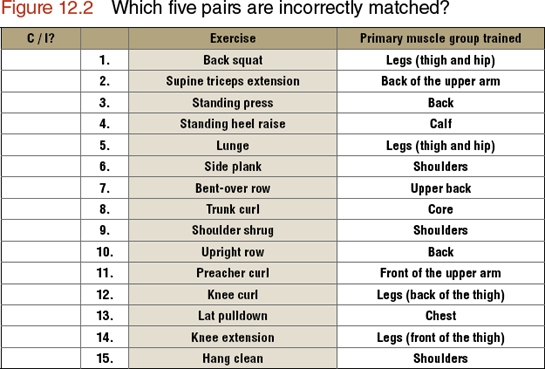

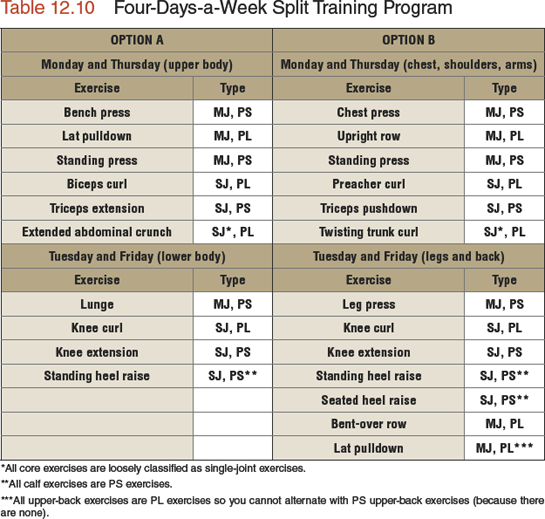

Review the exercises in steps 4 through 10. In figure 12.2, demonstrate your understanding of the specificity concept by marking in the left-hand column a “C” (to mean “correct”) where an exercise and the primary muscle group it trains are correctly matched and an “I” (for “incorrect”) where they are not. Can you find the five that are incorrect? The answers are on page 201.

Identify the one correct and two incorrectly paired exercises. Use the letter “C” to identify the correctly paired exercises. Use an “I” to identify the two pairs that are incorrect and then correct them. Answers are on page 202.

__ 1. Knee extension—back squat

__ 2. Extended abdominal crunch—back extension

__ 3. Dumbbell chest fly—upright row

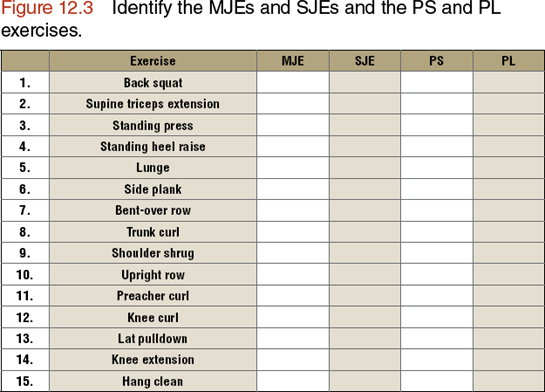

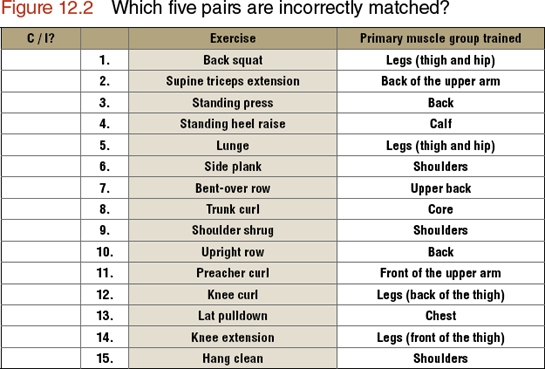

Before you are able to fully understand how to arrange exercises in a workout, you need to be able to classify exercises by type. Consider the muscle groups involved, how many joints change angles as the exercise is performed, and the push-pull movement patterns of each exercises listed in figure 12.3. Then identify the type of exercise by correctly placing an “X” in the MJE or the SLE column and an “X” in the PS or the PL column (each exercise will have two “X’s”). Answers are on page 202.

Apply knowledge of multiple and single-joint exercises.

Apply knowledge of push-pull movement patterns.

Apply knowledge of exercises in steps 4 through 10.

MANIPULATE PROGRAM VARIABLES

Now that you have a better understanding of exercise selection and arrangement, you need to decide on training load, repetitions, sets, and rest period length. Of these, determining training loads is the most challenging.

Training Loads

Opinions differ concerning how to handle this program design variable; however, the general consensus is that decisions should be based on the specificity concept and the overload principle. The overload principle asserts that each workout should place a demand on the muscles that is greater than what they are used to. Training that incorporates this principle challenges the body to meet and adapt to greater-than-normal physiological stress. As it does, it creates a new threshold that requires even greater stress to overload the involved muscles. Introducing overload in a systematic manner is sometimes referred to as progressive overload.

Methods for Determining Training Loads

Determining how much load to use is one of the most confusing aspects of a weight training program—and it’s probably the most important one because the load determines the number of repetitions you will be able to perform and the amount of rest you need between sets and exercises. It also influences decisions concerning the number of sets and the frequency of workouts. Two approaches can be taken to determine the amount of load to use in training.

In steps 4 through 9, you used your body weight to determine initial training loads for the basic exercises. The calculations were designed to produce light loads so that you could concentrate on developing correct technique and avoid undue stress on bones and joint structures. Your goal was to calculate a load that resulted in 12 to 15 repetitions. This method of determining a load is referred to as a 12- to 15RM method for assigning loads. The letter R is an abbreviation for “repetition” and the M stands for “maximum,” meaning the maximum amount of weight that you can lift with proper technique for 12 to 15 repetitions.

Another method is the 1RM method—a single (1) repetition (R) maximum (M) effort. Said another way, it is the maximum amount of weight that you can lift for one repetition in an exercise. Although not a perfect method (you are estimating or predicting that maximum load), it is more accurate than using body weight to determine initial training loads, especially if you have good exercise technique and are conditioned to safely handle heavier loads. It is not appropriate for a beginner, however, because it requires greater skill and a level of conditioning developed only after consistently following a weight training program for six weeks or more, depending on what shape you were in when you started.

The MJEs included in steps 4 through 10 are:

Bench press (free weight) and chest press (multi- or single-unit machine) from step 4

Standing press (free weight), shoulder press (cam machine), and seated press (multi- or single-unit machine) from step 6

Lunge (free weight), leg press (multi- or single-unit machine), and *back squat (free weight) from step 8

Hang clean and push press from step 10

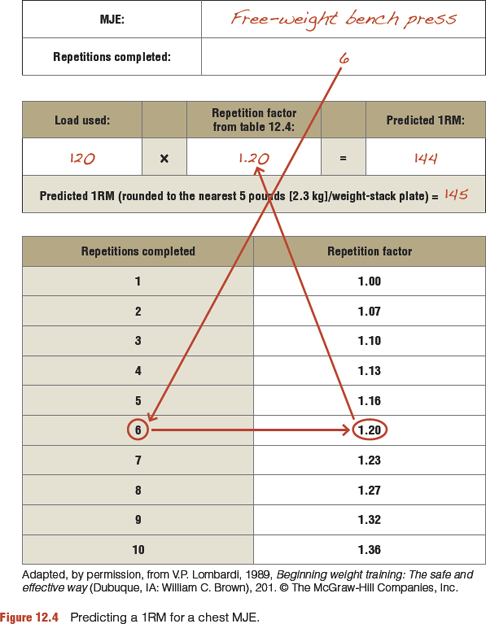

There are 10 procedures involved in estimating or predicting the 1RM.

1. The MJE you have selected is _________________________________.

2. Warm up by performing 1 set of 10 repetitions with your current 12 to 15RM load. Your current 12 to 15RM load is ____ pounds (____ kg).

3. Add 10 pounds (4.5 kg) or a weight-stack plate that is closest to that weight. Your current 12 to 15RM load plus 10 pounds (4.5 kg) = ________ pounds (________ kg).

4. Perform 3 repetitions with this load.

5. Add 10 more pounds (4.5 kg) or the next heaviest weight-stack plate = ________ pounds (________ kg).

6. Rest for 2 to 5 minutes and perform as many repetitions as possible with this load. Give it your best effort!

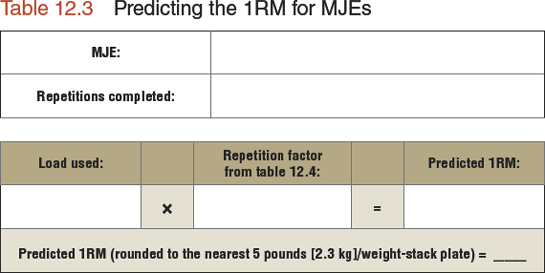

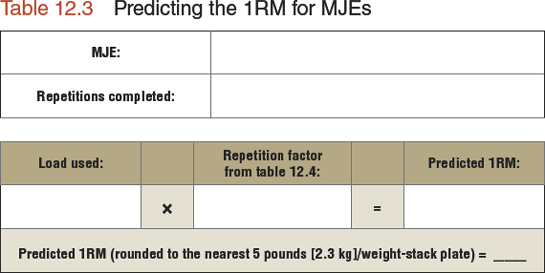

7. Using table 12.3, fill in the name of the exercise, the repetitions completed, and the load lifted.

8. Refer to table 12.4, “Prediction of 1RM.” Based on the number of repetitions you completed, circle the repetition factor number in the right-hand column of that table.

9. Record the circled repetition factor in table 12.3.

10. Multiply the repetition factor by the load used to obtain the predicted 1RM. Be sure to round the load to the nearest 5 pounds (2.3 kg) or weight-stack plate.

Table 12.4 Prediction of 1RM

| Repetitions completed |

Repetition factor |

| 1 |

1.00 |

| 2 |

1.07 |

| 3 |

1.10 |

| 4 |

1.13 |

| 5 |

1.16 |

| 6 |

1.20 |

| 7 |

1.23 |

| 8 |

1.27 |

| 9 |

1.32 |

| 10 |

1.36 |

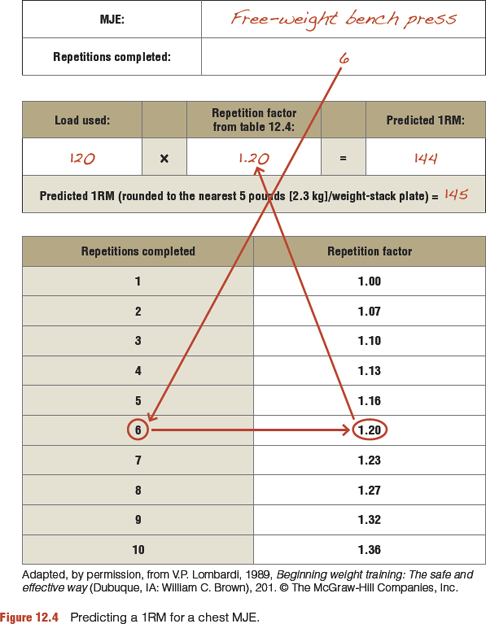

Figure 12.4 provides an example of applying the 10 procedures for predicting the 1RM for the free-weight bench press. In this example, six repetitions are performed with 120 pounds (54.4 kg). The repetition factor for six repetitions is 1.20, which when multiplied by 120 equals 144 pounds (65.3 kg). Rounding 144 off to the nearest 5-pound (2.3 kg) increment results in a predicted 1RM of 145 pounds (65.8 kg).

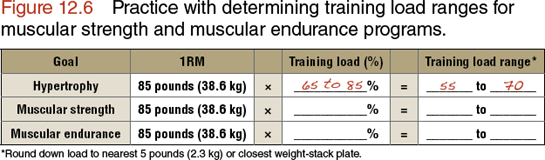

To use the 1RM to determine a training load, multiply the 1RM by a percentage. To continue the example from figure 12.4 (a predicted 1RM in the bench press of 145 pounds [65.8 kg]), if you decide to use a 75 percent training load, the formula for calculating the training load is 1RM × 0.75 or 145 × 0.75 = 108.75 pounds (rounded down to 105 pounds [47.7 kg]. See CAUTION on page 169). This process will be discussed in detail in the “Application of the Specificity Concept” section of this step.

Mark the correct choice in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 202.

1. 1RM refers to the [ ___ 1-repetition maximum ___ 1-minute rest minimum].

2. The [ ___ lunge ___ knee extension] is an example of a MJE.

3. The procedure for predicting the 1RM includes a total of [ ___ 10 ___ 20] pounds that are added to your 12- to 15RM load when performing as many repetitions as possible.

Increasing Loads

Lifting heavier loads as soon as you are able to complete the required number of repetitions is important. However, changes should not be made too soon. Wait until you can complete two or more repetitions more than the intended number in the last set of two consecutive workouts (the two-for-two rule; see step 11). When you have met the two-for-two rule, instead of referring to the load adjustment table (found at the end of steps 4 to 9), simply increase loads by 2.5 or 5 pounds (1.1 or 2.2 kg). The load adjustment chart was used initially to assist with large fluctuations in the number of repetitions performed. You will now find that fluctuations are much smaller and that using the two-for-two rule with a 2.5- or 5-pound increase works well, with two exceptions:

You may need to make heavier increases for MJEs. Be aware, though, that underestimating the increase needed is better than overestimating it.

Smaller load increments are appropriate for SJEs. Use 1.25- to 2.5-pound (0.6 to 1.1 kg) plates to increase loads in arm (biceps, triceps), forearm, calf, and neck exercises.

Mark the correct choice in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. The two-for-two rule concerns [ ___ resting 2 minutes after the second set of every exercise ___ completing 2 or more repetitions above the goal in the last set in two consecutive workouts].

2. Load increases for the bench press and squat exercises are likely to be [ ___ heavier ___ lighter] than those for the biceps and triceps exercises.

Number of Repetitions

The number of repetitions you will be able to perform is directly related to the load you select. As the loads become heavier, the number of repetitions possible becomes fewer; as the loads become lighter, the number of repetitions possible becomes greater. Assuming that a good effort is given in each set of exercises, the primary factor that dictates the number of repetitions is the load selected.

Mark the correct choice in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. Heavier loads are associated with a [ ___ greater ___ fewer] number of repetitions.

2. The number of repetitions that can be completed is primarily based on the [ ___ load ___ exercise].

Number of Sets

Some controversy exists as to whether multiple (two or more) sets are better than single sets for developing strength, muscular size, or muscular endurance. While one-set training works exceptionally well during the early stages (10 weeks or fewer) of training, growing research supports adding more sets to the programs of well-trained individuals.

It seems reasonable to expect that the multiple-set approach to training provides a better stimulus for continued development. The rationale is that a single set of an exercise will not recruit all the fibers in a muscle and that performing additional sets will recruit more fibers. This is because muscle fibers that were involved in the first set will not be sufficiently recovered and therefore will rely on fresh fibers (not previously stimulated) for assistance, especially if succeeding sets use an increased load.

When three or more sets are performed, the likelihood of recruiting additional fibers becomes even greater. Further support for multiple sets comes from observations of the programs followed by successful competitive weightlifters, powerlifters, and bodybuilders. These competitors rely on multiple sets to achieve a high degree of development. As you will see later, your goals for training should influence the number of sets you perform.

Another consideration in determining the number of sets is the amount of time you have for training. For instance, if you choose to rest for one minute between exercises in your program (for a goal of muscular size), you should plan on a minimum of two minutes per exercise (a minimum of 60 seconds to complete the exercise, plus 60 seconds of rest). Thus your program of seven exercises, in which you perform one set of each, should take 14 minutes. If you increase the number of sets to two, and then to three, your workout time will increase to 28 and 42 minutes, respectively (assuming a 60-second rest period after each set). The actual time for rest between sets, as you will read soon, may vary from 30 seconds to 5 minutes.

Mark the correct choice in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. The fewest number of sets recommended for continued development is [ ___ 1 ___ 2].

2. The basis for multiple-set training is that the additional sets are thought to [ ___ recruit ___ relax] a greater number of muscle fibers.

Length of the Rest Period

The impact of the rest period between sets and exercises on the intensity of training is not usually recognized, but it should be. Longer rest periods provide time for the energizers of muscle contraction to rebuild, enabling muscles to exert greater force. If the amount of work is the same, and the rest periods are shortened, the intensity of training increases. The length of time between sets and exercises has a direct impact on the outcomes of training.

Mark the correct choice in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. Longer rest periods enable you to exert [ ___ more ___ less] force.

2. The length of the rest period has [ ___ an effect ___ no effect] on the outcome of training.

Application of the Specificity Concept

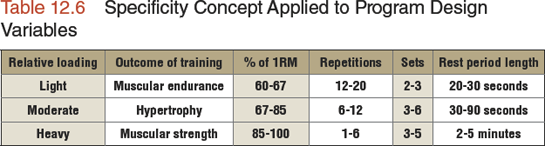

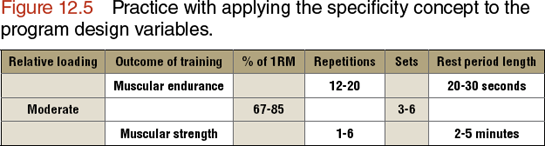

The earlier discussion of the specificity concept addressed only the issue of exercise selection, but this concept is broader in scope as it relates to program design. Table 12.5 shows a continuum or range from 100 to 65 percent of the 1RM and the number of repetitions associated with each percentage presented. For instance, selecting a load that represents 85 percent of the 1RM should yield 6 repetitions, whereas 67 percent of 1RM should yield about 12 repetitions. Knowledge of this inverse relationship is helpful when selecting loads if a specific number of repetitions is desired.

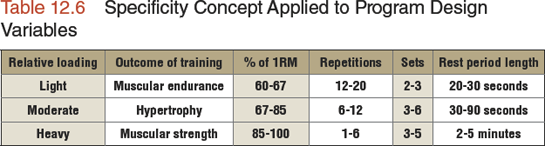

Loads, repetitions, sets, and rest periods are manipulated using the specificity concept in designing three different programs: muscular endurance, hypertrophy, and strength. Table 12.6 also illustrates a continuum on which the variables for the percentage of 1RM, number of repetitions and sets, and length of the rest period are presented. It reveals that muscular endurance programs (as compared to other programs) should include lighter loads (67 percent of 1RM or less), permit 12 to 20 repetitions, involve fewer sets (2 or 3), and have shorter rest periods (20 to 30 seconds). In contrast, programs designed to develop strength should include heavier loads (85 to 100 percent of 1RM) with fewer repetitions (1 to 6), more sets (3 to 5, possibly more), and longer rest periods between sets (2 to 5 minutes). Programs designed to develop hypertrophy (muscular size increases) have repetitions, sets, and rest periods assignments that fall between the guidelines for developing muscle endurance and strength.

Table 12.5 Percent of 1RM–Repetition Relationship

| % of 1RM |

Estimated number of repetitions that can be performed |

| 100 |

1 |

| 95 |

2 |

| 93 |

3 |

| 90 |

4 |

| 87 |

5 |

| 85 |

6 |

| 83 |

7 |

| 80 |

8 |

| 77 |

9 |

| 75 |

10 |

| 70 |

11 |

| 67 |

12 |

| 65 |

15 |

Muscular Endurance Program

The program you have been following in this book so far is designed to develop muscular endurance. You will notice some similarities between it and the program for muscular endurance in table 12.6. The loads you are using now may permit you to perform 15, but not quite 20, repetitions. Also, your rest periods should be close to the suggested 30 seconds if you have made an effort to shorten them. If you choose in step 14 to continue with your muscular endurance program, do not increase the load until you are able to perform 20 repetitions in the last set in two consecutive workouts and keep the rest periods at 20 to 30 seconds. Except for specific situations, such as training for competitive aerobic endurance events, rest periods of less than 20 seconds are not recommended or needed.

Muscular Endurance Program Self-Assessment Quiz

Write or mark the correct choices in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. The guidelines to use when designing a program for muscular endurance are:

a. Relative loading _____

b. Percentage of 1RM load _____

c. Repetitions _____

d. Sets _____

2. Unless there is a specific reason to do otherwise, the appropriate amount of rest between sets and exercises in a muscular endurance program is [ ___ 10 to 15 seconds ___ 20 to 30 seconds].

Hypertrophy Program

If you decide in step 14 to emphasize hypertrophy, refer to table 12.7 to see one method of implementing the guidelines in tables 12.5 and 12.6. The example uses a 1RM of 200 pounds (90.9 kg) in the leg press exercise. To allow 10 repetitions per set, use 75 percent of the 1RM. This calculation (200 × 0.75) equals 150 pounds (68.2 kg).

Table 12.7 Sample Hypertrophy Program: Multiple Set–Same Load Training

| Set |

Goal repetitions |

1RM × %1RM = training × load |

| 1 |

10 |

200 × 0.75 = 150 pounds (68.2 kg) |

| 2 |

10 |

200 × 0.75 = 150 pounds (68.2 kg) |

| 3 |

10 |

200 × 0.75 = 150 pounds (68.2 kg) |

Success in a hypertrophy program is associated with the use of moderate loads (67 to 85 percent of 1RM), a medium number of repetitions (6 to 12) per set, 3 to 6 sets, and moderate rest periods (30 to 90 seconds between sets). A simple method for estimating 67 to 85 percent loads is to add 5 to 10 pounds (2.3 to 4.5 kg) to the loads you are currently using. Do this only with MJEs; keep the loads for the SJEs the same and apply the two-for-two rule when making load adjustments.

You may notice that successful bodybuilders usually perform many sets and do not rest very long between them. Thus they combine the multiple-set program described earlier in this step with the rest period and load guidelines presented in table 12.6 to promote hypertrophy.

Two unique methods implemented in many hypertrophy programs are the superset and the compound set. A superset consists of two exercises that train opposing muscle groups that are performed without rest between them; for example, one set of the biceps curl exercise followed immediately by one set of the triceps extension exercise. A compound set is two exercises that train the same muscle group performed consecutively without rest between them. An example is one set of the barbell biceps curl exercise followed immediately by one set of the dumbbell biceps curl exercise. The fact that these approaches deviate from the rest periods shown in table 12.6 does not mean that they are ineffective. The time frames indicated are only guidelines; program design variables can be manipulated in many ways to produce positive outcomes.

Write or mark the correct answer in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 203.

1. The guidelines to use when designing a program for hypertrophy are:

a. Relative loading _____

b. Percentage of 1RM load _____

c. Repetitions _____

d. Sets _____

e. Length of the rest period _____

2. When two exercises for opposing muscle groups are performed without rest, this arrangement is referred to as a [ ___ superset ___ compound set].

Muscular Strength Program

Programs can be designed in many ways to produce significant strength gains. The two presented here are commonly used by successful powerlifters and weightlifters and are most appropriately applied to MJEs.

The first method is pyramid training. If you decide in step 14 to change your program to develop muscular strength, refer to table 12.8 to see one method of applying the guidelines presented in tables 12.5 and 12.6. The example uses a 1RM of 225 pounds (102.3 kg) in the back squat exercise. To calculate a load that will produce the goal of 6 repetitions in the first set, use 85 percent of the 1RM. (The second and third sets will be discussed later.) This calculation (225 × 0.85) equals 191.25 pounds (86.9 kg) which is rounded down to 190 pounds (86.4 kg).

Now, to incorporate the concept of progressive overload, you can use what is referred to as light to heavy pyramid training, in which each succeeding set becomes heavier; see the second and third sets in table 12.8, for examples. Increase the 85 percent of the 1RM (190 pounds [86.4 kg]) load to 90 percent of the 1RM (200 pounds [90.9 kg]) in the second set, and to 95 percent of the 1RM (210 pounds [95.5 kg]) in the third set. Between each set, rest for 2 to 5 minutes. Use this approach with the MJEs and perform 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions in the SJEs. (Heavy loads place too much stress on the smaller muscles and joints.) Forcing yourself to lift progressively heavier loads from set to set provides the stimulus for dramatic strength gains. As training continues and the intensity of workouts increases, a time will come when training with very heavy loads is appropriate only on designated days. This will be discussed further in step 13.

Table 12.8 Sample Muscular Strength Program: Pyramid Training

| Set |

Goal repetitions |

1RM × %1RM = training load |

| 1 |

6 |

225 × 0.85 = 190 pounds (86.4 kg)* |

| 2 |

4 |

225 × 0.90 = 200 pounds (90.9 kg)** |

| 3 |

2 |

225 × 0.95 = 210 pounds (95.5 kg)*** |

Multiple sets–same load training is another popular approach used to develop strength. With this method you perform 3 to 5 sets of 2 to 6 repetitions with the same load in the MJEs and 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions in the SJEs. The program can be made more aggressive by decreasing the goal repetitions, which means you must use heavier loads. To modify the pyramid training example from table 12.8 (a 1RM in the back squat of 225 pounds [102.3 kg]), see table 12.9. Notice how the percentages of the 1RM are associated with the goal repetitions of 4, 3, and 2 at the bottom of table 12.9. You will find that completing the specified number of repetitions in set 1 is usually easy, set 2 is more difficult, and set 3 is very difficult, if not impossible. With continued training, sets 2 and 3 will become easier, and eventually you will need to increase the loads.

Table 12.9 Muscular Strength Program: Multiple Sets–Same Load Training

| Set |

Goal repetitions |

1RM × %1RM = training load |

| 1 |

6 |

225 × 0.85 = 190 pounds (86.4 kg)* |

| 2 |

6 |

225 × 0.85 = 190 pounds (86.4 kg))* |

| 3 |

6 |

225 × 0.85 = 190 pounds (86.4 kg))* |

Write or mark the correct answer in each of the following statements. Number 4 has two answers. Answers are on page 204.

1. The guidelines to use when designing a program for muscular strength are:

a. Relative loading _____

b. Percentage of 1RM load _____

c. Repetitions _____

d. Sets _____

e. Length of the rest period _____

2. Given a 1RM of 200 pounds (90.9 kg) and a goal of muscular strength development, the lightest load for a first set should be [ ___ 170 pounds (77.3 kg) ___ 140 pounds (63.6 kg)].

3. The use of sequentially heavier loads in each set of the pyramid training approach demonstrates the use of the [ ___ two-for-two rule ___ progressive overload principle].

4. The two muscular strength development programs described here have been referred to as [ ___ 1RM ___ pyramid ___ multiple set–same load ___ overload].

5. The heavy loads of a muscular strength program are not used with [ ___ MJEs ___ SJEs] because they place too much stress on the involved muscle and joint structures.

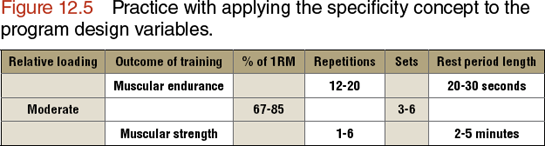

You have learned how the specificity concept and overload principle are used in determining loads, and what the implications of these loads are on the number of repetitions and sets and on the length of the rest periods between exercises and sets. As a review, fill in the missing information in figure 12.5. Answers can be found in table 12.6, page 167.

Apply the specificity concept to determine the relative loading, training outcome, percent of 1RM, repetitions, sets, and rest period length.

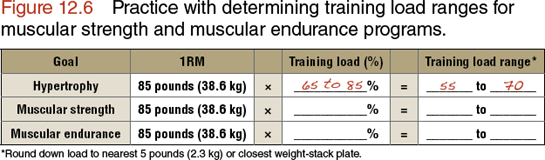

This drill will give you experience in determining training loads, using either a predicted or actual 1RM, and in applying what you’ve learned about training loads. Using 85 pounds (38.6 kg) as the 1RM and the example shown for a hypertrophy program, determine the training load ranges for a muscular strength and a muscular endurance program. Remember to round down to the nearest 5 pounds (2.3 kg) or closest weight-stack plate. Write your answers in the blanks in figure 12.6. Answers are on page 204.

DECIDE TRAINING FREQUENCY

Training frequency is the last design variable to be covered before you will be challenged to design your own program. The question that needs to be answered is “How often should I train?” The frequency of your training, just like the application of the overload principle, is an essential element in determining the proper intensity for a successful training program.

To be effective, you must train on a regular, consistent basis. Sporadic training short-circuits your body’s ability to adapt. Know, though, that rest days between training days are as important as the actual training. Your body needs time to recover, to move the waste products of exercise out of the muscles and nutrients in so that muscles that are torn down from training can rebuild and increase in endurance, size, or strength. Rest and nutritious foods are essential to ongoing success.

Often people who are new to weight training become so excited with the changes in their strength and appearance that they start training on scheduled rest days. More is not always better, especially during the beginning stages of your program! If you are relatively new to weight training, you will need to insert rest days between training days evenly throughout the week. The result is a schedule that permits two to three workouts of the same exercises per week. As you become more accustomed to training, you can include additional exercises. Eventually, your program will include too many exercises to perform all in one workout, so you may decide to add another training day each week and redistribute (split up) the exercises across more workouts. This will make the length of each workout more reasonable and provide variety to your program.

For beginners, allowing at least 48 hours between workouts that train the same muscles is important. The result is a three-days-a-week program. Typically, this means training on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday; or Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday. In a three-days-a-week program, all exercises are performed each training day.

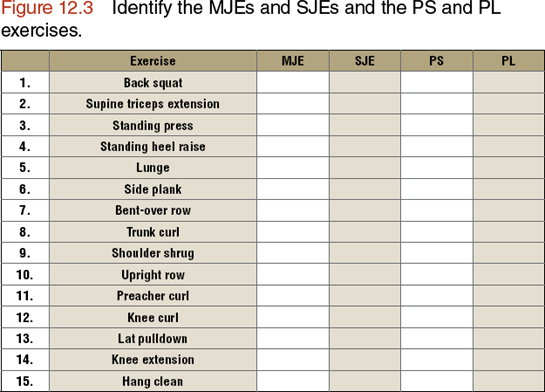

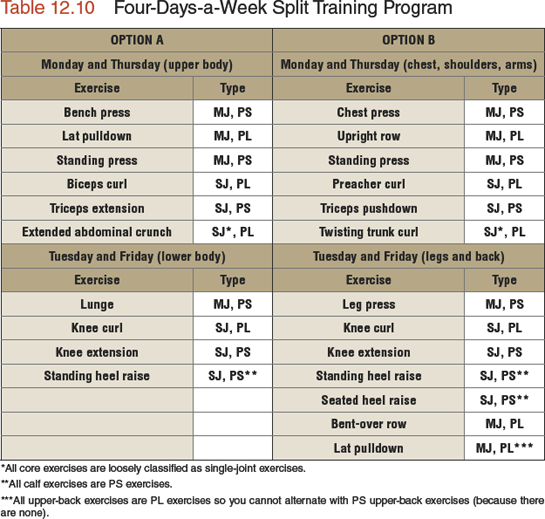

A split program is a more advanced method of training that involves performing some of the exercises two days a week (for example, Monday and Thursday) and the others on two other days (for example, Tuesday and Friday). A split program typically involves more exercises and sets; it requires four training days as shown in table 12.10. On the left half of this table (Option A), exercises are split into upper body and lower body. Option B illustrates another common split-program option in which exercises for the chest, shoulders, and arms are performed on different days than leg and back exercises. Notice that in both options the exercises have been arranged so that PS and PL exercises are alternated, and triceps and biceps exercises follow the upper body PS and PL exercises, respectively. Also, MJEs are performed before SJEs within the upper body exercise list and within the lower body exercise list.

A split program offers several advantages. It spreads the exercises in your workout over four days instead of three, usually reducing the amount of time required to complete each workout. This allows you to add more exercises and sets while keeping workout time reasonable. Because you can add more exercises, you can emphasize development in specific muscle groups, should you decide to do so. The program’s disadvantage is that you must train four days a week instead of three.

Mark the correct choices in each of the following statements. Answers are on page 204.

1. Creating the proper stimulus for improvement depends on using the overload principle and training [ ___ on a regular basis ___ in a sporadic manner].

2. Compared to a split program, a three-days-a-week program typically includes a [ ___ greater ___ fewer] number of exercises.

3. Compared to a three-days-a-week program, the workouts in a split program usually take [ ___ less ___ more] time to complete.

4. A [ ___split ___ three-days-a-week] program offers the best opportunity for emphasizing development in specific muscle groups.

Table 12.10 Four-Days-a-Week Split Training Program

SUCCESS SUMMARY FOR PROGRAM DESIGN PRINCIPLES

A clear understanding of how to apply the specificity concept and the overload principle is the basis for well-conceived programs. Understanding and incorporating the guidelines for loads, repetitions, sets, and rest period length in designing muscular endurance, hypertrophy, and muscular strength programs are the keys to meeting your specific needs.

When selecting exercises, keep in mind the specificity concept, available equipment, and spotter requirements for each exercise. Also, include at least one exercise for each of the seven muscle groups and remember to select balanced pairs of exercises. Include additional exercises if you want to emphasize the development of certain muscle groups but not so many that workouts take too long. Lastly, remember that how you arrange exercises and the order in which you perform them also has an impact on the intensity of your overall program.

Training on a regular basis is essential to the success of your weight training program. Beginning programs typically begin with two or three workout days a week and may evolve into a four-days-a-week split program. The greater time commitment in split programs is offset by the advantages of being able to emphasize certain body parts because of the extra training time.

Your ability to recover from workout sessions is critical to your future training successes—more is not always better. Finally, muscles need to be nourished, especially after a challenging workout. Eating nutritious meals is essential for muscle repair and increases in size and strength.

Step 13 provides strategies on how to modify or vary the program you have been following to avoid a plateau in your progress and keep you moving toward your weight training goals. A common way to vary your program is to incorporate purposeful changes in training intensity.

Before Taking the Next Step

1. Have you completed all of the self-assessment quizzes and checked your answers?

2. Do you understand how to manipulate training variables for different types of programs—muscular endurance, hypertrophy, and muscular strength?

3. Do you understand the specificity principle and how to apply it to create your program?