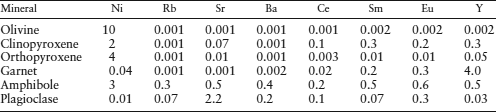

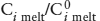

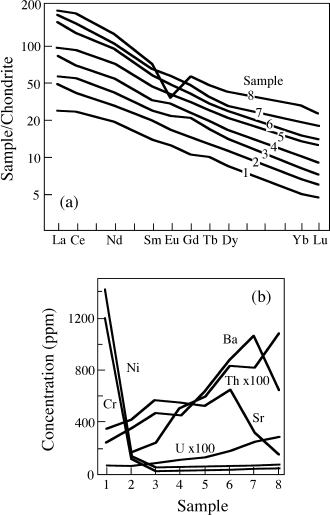

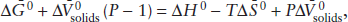

|

|

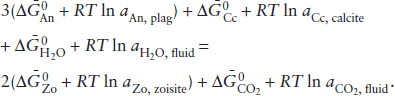

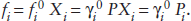

In this chapter, we explore how the various parts of the Earth’s interior can be integrated into a grand geochemical system. First, we estimate the compositions of the reservoirs—that is, crust, mantle, and core—in terms of both chemistry and phase assemblages. We then investigate how these reservoirs interact through the exchange of heat and matter. The continental crust was extracted from the upper mantle, which appears to be geochemically isolated from the lower mantle. Generally, convection within the upper mantle and crust is manifested in plate tectonics. During certain episodes, however, whole-mantle convection may occur, resulting in sinking of lithospheric plates into the lower mantle and return flow of matter to the surface via large mantle plumes. These episodes are driven by thermal convection in the liquid outer core, resulting from exothermic crystallization of the solid inner core. Many geochemical interactions between mantle and crust involve basaltic magmatism, so we discuss the thermodynamics of melting and the geochemical characteristics of partial melts of mantle rocks generated under various conditions. Most magmas experience significant chemical changes en route to the surface. Differentiation of magmas by fractional crystallization and liquid immiscibility is considered, and we attempt to quantify their geochemical consequences. The behavior of compatible and incompatible trace elements during melting and differentiation is also examined. As we shall see, trace elements can be used to quantify geochemical models of magma evolution. We then consider the compositions, reservoirs, and cycling of volatile elements within the mantle and crust.

The crust is the outer shell of the Earth, in which P-wave seismic velocities are <7.7 km sec−1. The lower boundary of the crust is the Mohorovicic discontinuity (the Moho), a layer within which seismic velocities increase rapidly or discontinuously from crustal values to mantle values of >7.7 km sec−1. The average thickness of the crust defined in this way is 6 km in ocean basins, ∼35 km in stable continental regions, and ranges up to 70 km under mountain chains. Even so, the crust is only a minuscule portion of the mass of the planet, constituting only about 0.5% of it by weight.

Oceanic crust shows no major lateral and vertical changes in P-wave velocity. As a first approximation, it can be considered to have basaltic composition throughout, although studies of ophiolites reveal that it has a veneer of siliceous sediments and contains ultramafic rocks at depth. In contrast, the lateral heterogeneity of continental crust, so evident in geologic maps, apparently persists to great depth as revealed by variations in subsurface P-wave velocities. This heterogeneity complicates any attempt to estimate the bulk composition of the crust as a whole.

Continental crust is conventionally thought to be subdivided into a “granitic” upper layer and a “gabbroic” lower layer, separated by a seismic discontinuity (the Conrad discontinuity) that is not everywhere laterally continuous. This view is certainly too simplistic and may be wrong altogether. The common mineral assemblage of gabbro, for example, is apparently not stable at the temperatures and pressures that occur in the lower crust. Rocks of this composition should be transformed to eclogite, a mixture of garnet and clinopyroxene. The density of eclogite, however, is too high to fit the measured seismic velocities of the lower crust. If there is enough water in the lower crust, “gabbroic” rocks could instead consist of amphibolites (amphibole + plagioclase rocks), which do have the appropriate seismic properties. Another idea consistent with seismic constraints is that much of the lower crust under continents is composed of granulites of intermediate composition.

There are various ways to approach the thorny problem of determining an average composition for the crust, and all depend on assumptions that we make in describing crustal heterogeneity. We might choose to take the weighted average of the compositions of various crustal rocks in proportion to their occurrence, using, for example, geologic maps as a basis. Less direct approaches utilize the analyses of clays derived from glaciers that have sampled large continental areas, or estimate the relative proportions of granitic and basaltic end members by mixing their compositions in the proper ratio to reproduce the compositions of sediments derived by crustal weathering. All of these methods have been tried and generally give similar results.

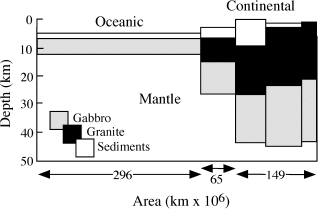

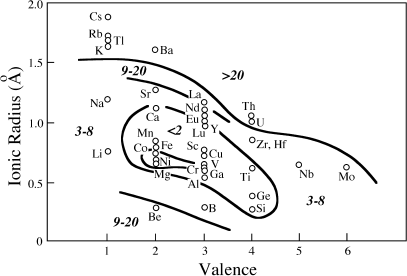

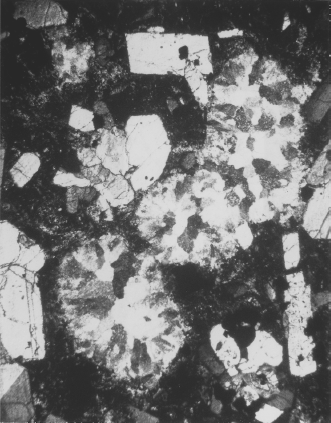

The most widely accepted crustal compositions usually involve averaging the compositions of rocks assigned to hypothetical crustal models. This approach was adopted by A. B. Ronov and A. A. Yaroshevsky (1969), using the crustal model illustrated in figure 12.1. Their calculated crustal composition is given in table 12.1. Ross Taylor and Scott McLennan (1985) estimated the composition of the crust by assuming that it was composed of 75% average Archean crustal rocks and 25% andesite. The Taylor and McLennan model (table 12.1) is somewhat more mafic than that of Ronov and Yaroshevsky, with lower concentrations of SiO2 and alkalis and higher concentrations of FeO, MgO, and CaO. However, both of these calculated crustal compositions are remarkably similar to the composition of average andesite, also shown in table 12.1. The mineralogy of the average crust is thought to be similar to that of andesite, which is dominated by feldspars, quartz, pyroxenes, and amphibole.

FIG. 12.1. A model for the Earth’s crust used in the calculation of its average composition. (Adapted from Ronov and Yaroshevsky 1969.)

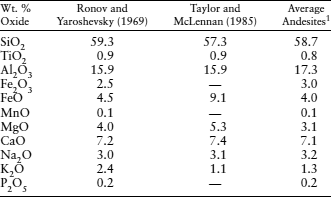

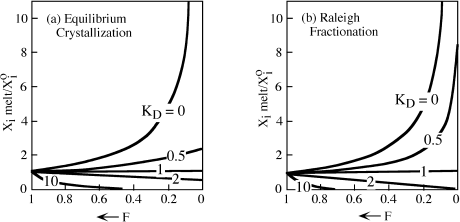

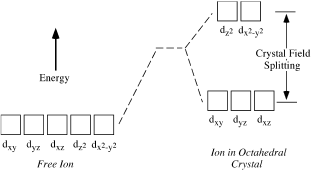

The crust is strongly enriched in incompatible elements (those that partition into magmas because they do not fit easily into the crystal structures of the minerals that remain unmelted). The incompatible elements in the crust are lithophile, so-called because they prefer silicate phases to metal or sulfide, as noted in chapter 2. Included in this category are elements with large ionic size (K, Rb, Cs, U, Th, Sr, Ba, and some rare earth elements, such as La and Nd) and high field strength elements that have high ionic charge (Nb, Ta, Zr, Hf, Ti). Figure 12.2 summarizes the enrichment of lithophile elements in the crust relative to abundances in the primitive mantle, plotted against ionic radius and valence. Contours in this figure group elements with similar enrichment factors. Enrichments of lithophile elements in the continental crust are so extreme that multiple periods of melting are required, resulting in a refining process that further sequesters these elements at each melting step. Lithophile elements are thought to have been extracted from the mantle during crust formation.

TABLE 12.1. Estimates for the Average Composition of the Earth’s Crust

1Average of 89 andesites from island arcs compiled by McBirney (1969).

FIG. 12.2. Enrichment of Lithophile elements in the continental crust relative to abundances in the Earth’s primitive mantle. Ions of large size and/or charge are incompatible in common mineral structures and so are concentrated in melts. Over time, these melts have enriched the crust in incompatible elements. Contours group elements with similar degrees of enrichment, from <2, 3–8, 9–20, and >20. (After Taylor and McLennan 1985.)

The mantle, that region of the Earth’s interior between the Moho and the core, is of course not directly accessible for study. What we know about it comes from indirect evidence, mostly geophysical. Seismic wave velocities as a function of depth can be used to calculate elastic parameters, which depend on the chemical and mineralogic composition of the mantle, as well as temperature and pressure. Comparison of measured seismic data with the results of laboratory measurements of the ultrasonic properties of various phases provides the information necessary for inferring the composition of the upper mantle. For the lower mantle, we must use theoretical relationships between velocity and density and deduce compositions from shock wave experiments. Despite the inherent uncertainties in interpreting mantle seismic data, the mineralogic composition of the mantle seems reasonably well determined.

P-wave seismic velocities of 7.8–8.2 km sec−1 just below the Moho are consistent with an upper mantle having the bulk density of peridotite (olivine + orthopyroxene + clinopyroxene) or eclogite (defined above as clinopyroxene + garnet). Although both of these rock types occur in the mantle, peridotite is thought to predominate. As we shall see, one of the constraints on petrologic modeling is that mantle rocks must be capable of generating basaltic liquids on partial melting. Peridotite can do this, but eclogite cannot. The simple reason is that eclogite already has a basaltic composition, and thus must melt completely to produce basaltic magma. Clearly then, the mantle, consisting mostly of ultramafic rocks, has a profoundly different bulk composition from the crust.

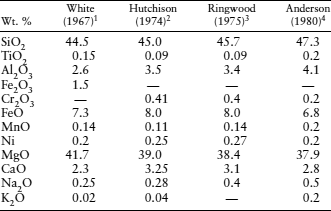

TABLE 12.2. Estimates for the Average Composition of the Earth’s Mantle

1From frequency histograms of 168 ultramafic rocks.

2From mantle peroditite nodules.

3Pyrolite.

480% garnet peridotite + 20% eclogite.

Some crustal occurrences of tectonically emplaced ultramafic rocks may have been derived directly from the mantle. The compositions of abundantly exposed ultramafic rocks may be representative of the mantle. A preferred mantle composition, calculated from frequency histograms of ultramafic rocks, is presented in column 1 of table 12.2.

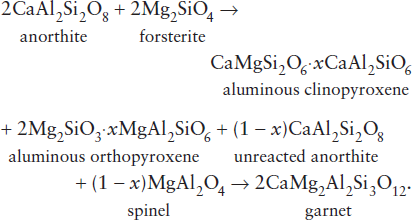

Another constraint on the composition of the mantle comes from xenoliths of mantle material carried upward by erupting magmas. Those that have not been altered by extraction of basaltic magma consist of either peridotite or eclogite. We focus on the peridotites, which we have already concluded are the best candidates for the bulk of the mantle. There are essentially two types: spinel peridotites, containing olivine, enstatite, diopside, and Cr-Al spinel; and garnet peridotites, containing olivine, enstatite, diopside, and pyrope garnet. In both cases, olivine and pyroxenes predominate, but the presence of spinel or garnet is very important. Even though the pyroxenes in peridotite xenoliths are commonly aluminous, they do not contain enough aluminum to account for the plagioclase component of basalts produced by partial melting. In rocks of ultramafic composition, plagioclase itself is the Al-bearing phase at low pressures, but this gives way to spinel and garnet at higher pressures. The spinel- and garnet-forming reactions can be represented by:

One example of the use of peridotite xenoliths as a measure of the composition of the mantle is illustrated in column 2 of table 12.2.

One of the problems we encounter in estimating the mantle composition has to do with partial melting. A peridotite assemblage without spinel or garnet (and often without clinopyroxene as well) is said to be depleted, because basaltic magma has already been extracted from it. Conversely, peridotite that can still produce basaltic melt is called undepleted. But how do we determine what proportion of the mantle is depleted and what proportion is undepleted? This dilemma forms the basis for a class of hypothetical mantle models known as pyrolite, originally devised in 1962 by Ted Ringwood. He postulated a primitive mantle material that was defined by the property that on fractional melting it would yield basaltic magma and leave behind a residual refractory dunite-peridotite. The composition of pyrolite (“pyroxene–olivine” rock) can be derived, therefore, by combining depleted peridotite and the complementary basalt in the proper proportions. This is a rather flexible model for the mantle composition. Ringwood and his collaborators at various times have presented pyrolite compositions with peridotite:basalt ratios varying from 1:1 to 4:1, although the 3:1 ratio is most often quoted as a reasonable value. A mantle composition based on pyrolite is compared with others already discussed in column 3 of table 12.2.

Not only is basaltic magma removed from the mantle, but it is also recycled back into the mantle (in the form of eclogite) by subduction. Consequently, we might also envision a model composition for the mantle that mixes average eclogite and undepleted peridotite in the correct proportions. The model presented in column 4 of table 12.2 does just that.

All of these methods give comparable results, and the composition of the mantle seems reasonably well constrained, at least for the major elements. We should keep in mind, however, that these estimates are for the upper mantle, although they are commonly used to describe the composition of the entire mantle. Is there any basis for this extrapolation?

Ringwood (1975) provided a wealth of information about the stability of phases at various depths in a mantle of pyrolite composition. Down to a depth of 600 km, the assumed mineral assemblages are based on the results of high-pressure experiments, but below this depth, Ringwood had to infer what phases would be stable from indirect evidence, such as experimental data on germanate ( ) analog systems. If germanium is substituted for silicon, phase transformations that were experimentally inaccessible for silicates occur within pressure ranges that could be studied in the laboratory. Since that time, multianvil high-pressure apparatus and shock wave experiments have confirmed the proposed phase relationships for the equivalent silicates. These phase changes (see the accompanying box) correspond very well with observed seismic discontinuities in the mantle, so it seems plausible that, to a first approximation, the mantle has a pyrolite composition throughout. This would mean that most discontinuities within the mantle result from phase changes, in contrast to the Moho, which is due to a change in chemical composition.

) analog systems. If germanium is substituted for silicon, phase transformations that were experimentally inaccessible for silicates occur within pressure ranges that could be studied in the laboratory. Since that time, multianvil high-pressure apparatus and shock wave experiments have confirmed the proposed phase relationships for the equivalent silicates. These phase changes (see the accompanying box) correspond very well with observed seismic discontinuities in the mantle, so it seems plausible that, to a first approximation, the mantle has a pyrolite composition throughout. This would mean that most discontinuities within the mantle result from phase changes, in contrast to the Moho, which is due to a change in chemical composition.

It is convenient to distinguish the upper and lower mantle, which are separated by a seismic discontinuity at 650–700 km depth. These two reservoirs apparently have different abundances of incompatible trace elements. The upper mantle is strongly depleted in incompatible elements, which were presumably extracted during crust formation, whereas the lower mantle has higher abundances of these elements. There is also some evidence that the upper and lower mantle may have different compositions in terms of major elements, expressed in their inferred Mg/Si, Fe/Si, and Ca/Al ratios. Such variations might have resulted from crystallization in a largely molten mantle during its formation. If this is correct, then the 650-km discontinuity (sometimes called the 670-km discontinuity) is also a compositional boundary, and not just a phase change.

The lowermost 200 km of the mantle, sometimes called region D, has peculiar seismic properties and may have a distinct chemical composition from the rest of the lower mantle. This region may be a mixture of mantle material with subducted slabs of ancient crustal rocks. The term piclogite is sometimes used to describe this mixture. Piclogite differs from pyrolite in the upper mantle in that its ultramafic component is undepleted and thus rich in incompatible elements.

The mean density of the Earth is consistent with a large, metallic iron core, and its moment of inertia and free oscillations indicate that this mass is concentrated at the planet’s center. A major seismic discontinuity at 2900 km depth marks the mantle-core transition, so the core is approximately half the radius of the Earth. Variations in compressional wave velocities through the core have led to the conclusion that the outer core is liquid and the inner core is solid. In fact, the outer core is the largest magma chamber inside the Earth, forming a layer 2260 km thick between the crystalline lower mantle and the solid inner core. Most of what we know about the core is derived from indirect seismic observations. Despite the rigorous aspects of this discipline, one geophysicist has described the inversion of geophysical data to yield geological information as “like trying to reconstruct the inside of a piano from the sound it makes crashing down stairs.” Can geochemistry shed any light on this complex problem?

Geophysical methods applied to study of the core are capable of detecting elements with very different atomic weights, but they cannot distinguish among elements similar in weight to iron. One such element, nickel, is thought to be an important constituent of the core, based on its siderophile character (its geochemical affinity for metal) and its high cosmic abundance (its abundance on average in the solar system). To first order, the core can thus be visualized as a mass of Fe-Ni alloy, part liquid and part solid. We can also infer that other siderophile elements, such as cobalt and phosphorus, might be important constituents.

The density of the outer core is about 8% less than that of the inner core. This is interpreted as reflecting the presence of an additional component, an element of low atomic weight, in the outer core. Considerable support has developed for the hypothesis that this element is sulfur. The seismic velocities of sulfide and metal at high pressures indicate that ∼10 wt % S would be necessary to account for the lower density of the outer core. Iron meteorites, which formed as cores in asteroids, also contain significant amounts of sulfur as FeS (the mineral troilite). Other geochemists have argued that oxygen is the light element in the outer core. Bonding in FeO is expected to become metallic, rather than ionic, at very high pressures, and an outer core with a composition of about Fe2O (50 mol % oxygen) would satisfy the density constraint. Although oxygen is not alloyed with metal in iron meteorites, the cores in asteroids would not have formed at the high pressures necessary for this reaction. Another possibility is silicon; the density of Fe-Si alloys at core conditions requires ∼17 wt % Si.

PHASE CHANGES IN THE MANTLE

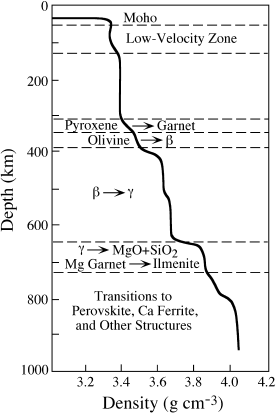

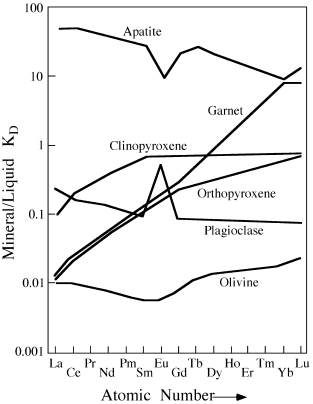

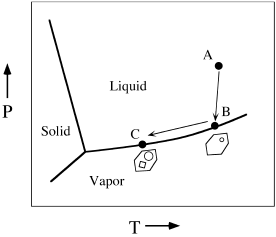

Ted Ringwood’s suggested mantle mineralogy as a function of depth is summarized in figure 12.3. The wavy diagonal line from upper left to lower right represents the density distribution with depth, inferred from P-wave velocities and corrected for the effect of compression due to the overlying rock. Starting near the top, just below the Moho, we first encounter the low-velocity zone, a region of inferred partial melting in which seismic velocity decreases. The stable assemblage at this point is olivine + orthopyroxene + clinopyroxene + garnet. Just below 300 km, pyroxenes transform to a garnet crystal structure. One of the two major discontinuities in the mantle occurs at 400 km; this corresponds to the conversion of olivine, volumetrically the most important phase to this point, into a more tightly packed structure called the β phase (also called wadsleyite). At this point, the mantle consists of β-olivine and a complex garnet solid solution. Another less pronounced seismic wiggle at ∼500 km may be due to the transformation of the β phase into a spinel (γ) structure (also called ringwoodite), as well as a second reaction in which the calcium component of garnet, possibly with some iron, separates as (Ca,Fe)SiO3 in the dense perovskite structure.

The second major seismic discontinuity in the mantle is seen at 650–700 km. At this point, γ-olivine is thought to disproportionate into its constituent oxides, MgO (periclase) + SiO2 (stishovite). The (Mg, Fe)SiO3-Al2O3 components of the garnet solid solution presumably also transform into the ilmenite structure. Below this transition, the mantle consists of periclase + stishovite + MgSiO3⋅Al2O3 (ilmenite) + (Ca,Fe)SiO3 (perovskite).

The density changes in mantle materials below ∼700 km could be caused by further phase transformations to more tightly packed structures with Mg and Fe in higher coordination, but it is very difficult to specify exactly what transformations may take place. Some additional phases that have been suggested to be stable in the lower mantle include (Ca, Fe, Mg)SiO3 in the perovskite structure, (Mg, Fe)O in the halite structure, and (Mg, Fe)(Al, Cr, Fe)2O4 in the calcium ferrite structure. From the generality of these formulas, we can see how speculative these phases are.

FIG. 12.3. Summary of possible phase transformations in the mantle, as determined by Ringwood (1975). The densities shown by the solid line are zero-pressure densities (corrected for depth) calculated for pyrolite; density discontinuities correspond to phase transformations inferred from seismic studies.

Another possible explanation for the higher densities in the deep mantle is an increased Fe/Mg ratio. Such a change in mantle composition would have important geochemical implications, but it is difficult to confirm because the behavior of iron in the mantle is so uncertain. It has been suggested that Fe2+ ions in silicates may undergo a contraction in radius due to spin-pairing of electrons below 1200 km depth. This is potentially important because low-spin Fe2+ probably would not substitute for Mg in solid solutions. Another hypothesis, with some experimental justification, is that Fe-bearing silicates might disproportionate to form some metallic iron, even at modest depths of ∼350 km. This metal might then sink, stripping Fe from some parts of the mantle and enriching others.

One way to estimate the composition of the core directly is to assume that siderophile elements are present in cosmic relative abundances to iron. (We discuss cosmic abundances in chapter 15.) An example of this approach is shown in the following worked problem.

Worked Problem 12.1

What is the composition of the Earth’s core? One way to estimate core composition is to assume that siderophile elements accompany iron in cosmic proportions. Of course, we must also include major amounts of a light element to account for the density of the outer core, and we have just seen that this element may not be in cosmic proportion relative to iron.

Let’s assume a value of 9.0 wt % sulfur in the core, based on sulfur abundance from density constraints. The first step, then, is to determine how much iron must be combined with sulfur to make FeS:

9.0/32.05 g mol−1 = x/55.85 g mol−1,

so that:

x = 15.68 wt % Fe.

The wt % FeS in the core is then 15.68 + 9.0 = 24.68. By difference, the core must consist of 75.32 wt % metal.

The metal phase also contains other siderophile elements in addition to iron. Siderophile elements with the highest cosmic abundances are nickel, cobalt, and phosphorus, and these are prominent constituents of iron meteorites. A mass balance equation for metal is thus:

Femetal + Ni + Co + P = 75.32%,

or

Femetal = 75.32 − Ni − Co − P,

where the abundance of each element is expressed in wt %. Nickel can be determined from the cosmic wt ratio of Ni and Fe:

| Ni = | (Nicosmic/Fecosmic) Fecore |

| = | (4.93 × 104/58.77 g mol−1)/ |

| (55.85 g mol−1/9 × 105)Fecor = 0.0521 Fecore, |

where Fecore is the total abundance of iron in the core, equal to Femetal + 15.68. Similarly, Co = 0.0024 Fecore and P = 0.0208 Fecore. Substitution of these values into equation 12.1 gives:

| Femetal = | 75.32 − 0.0521 Fecore − 0.0024 Fecore |

| − 0.0208 Fecore = 68.94 wt %. |

Thus, the total amount of iron in the core is 68.94 + 15.68 = 84.62 wt %. Nickel, cobalt, and phosphorus wt percentages are obtained by multiplying their cosmic wt ratios by 84.62; the respective values are 4.41, 0.20, and 1.76 wt %.

Cycling between Crust and Mantle

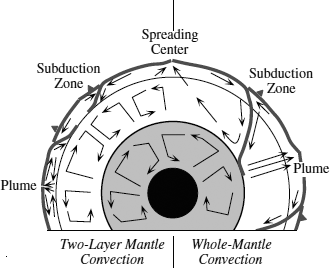

The mantle and crust are coupled through plate tectonics, which provides a mechanism for adding mantle material and heat to the crust (through volcanic activity) and recycling crust back into the mantle (through subduction). Plate tectonics reflects mantle convection, although the relationship is not as clear as was once thought. At present, ocean floor is being created and subducted at a rate of ∼3 km3 yr−1. If the average thickness of a plate is 125 km, then 375 km3 of rock is subducted each year. At that rate, the entire mantle (having a volume of 9 × 1011 km3) could be processed through the plate tectonic cycle in 2.4 billion years (approximately half the age of the Earth). Mantle plumes, also called hot spots, are sites of volcanism that also must relate to convection. Mantle convection plays a dominant role in cooling the Earth, but there is no consensus on how convective flow extends to depth.

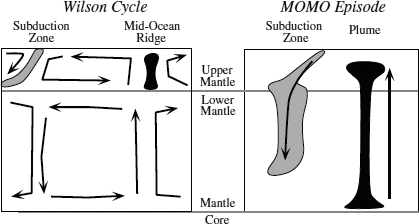

The main controversy centers on whether the whole mantle is involved in convective overturn, or the upper and lower mantles convect separately. The most prominent convection is associated with the sinking of plates at subduction zones. These plates are metamorphosed to dense eclogite on subduction, which adds to the gravitational imbalance caused by their cooler temperatures. On approaching 650 km depth, however, the high calcium and aluminum contents of eclogite stabilize garnet and hinder transformation to the denser perovskite that occurs in the surrounding mantle peridotite, so the density contrast decreases. Studies of earthquakes show that the subducted plates descend to depths of 650 km, below which seismicity is absent (fig. 12.4). Some high-resolution seismic images indicate that subducted slabs bounce off the 650-km discontinuity and accumulate in the upper mantle. However, other seismic studies have documented that subducted slabs sometimes sink below this boundary, in some cases all the way to the interface between the mantle and core (fig. 12.4). The subducted crust is colder than the lower mantle into which it descends, so differences in seismic velocity allow the slabs to be imaged using seismic tomography. If subducted slabs are used as a tracer for convection, then the upper and lower mantles are sometimes isolated from each other and sometimes not.

FIG. 12.4. Sketch of a cross-section of the Earth, showing convection in the core, mantle, and crust. Mantle plumes and subduction zones allow interaction of matter between mantle and crust. The left side of the diagram illustrates two-layer mantle convection and the right side shows whole-mantle convection.

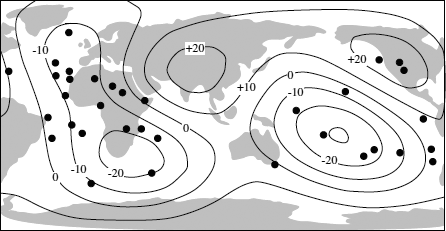

If slabs sink to the core-mantle boundary, an equivalent mass of material must be transferred back into the upper mantle or crust. Such material would be relatively hot and thus have lower seismic velocities. Seismic tomography reveals that two regions of low velocity occur within the lower mantle: one underlies the Pacific basin and the other is situated beneath southern Africa (fig. 12.5). Within both these areas lie the majority of the Earth’s plumes, and both areas are highs on the geoid (the geometrical form that describes the planet’s shape). The return flow from the lower mantle thus appears to consist of scattered upwellings that form clusters of hot spots.

The existence of separate mantle reservoirs for various kinds of magmas supports the idea that the upper and lower mantles do not convect as a single unit. The midocean ridge basalts (MORB) that erupt at spreading centers are strongly depleted in incompatible elements. Melting experiments suggest that MORB is generated at pressures corresponding to depths within the upper mantle. The depletion of incompatible elements in this source region constitutes evidence that the crust was extracted from the upper mantle, as illustrated in worked problem 12.2. Conversely, magmas thought to be generated within the lower mantle and erupted at hot spots have higher abundances of incompatible elements. The lower mantle may thus be geochemically isolated from the upper mantle, although plumes generated at the core-mantle boundary obviously must pass through both the lower and upper mantle on their way to the surface.

FIG. 12.5. Contours of average lower mantle seismic velocity perturbations define two large regions of high temperature (low velocity, indicated by negative contours). These regions define the locations of mantle plumes, and they correspond to clusters of hot spots (solid circles). (Redrawn from Castillo 1988.)

Worked Problem 12.2

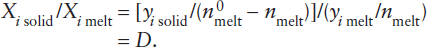

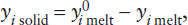

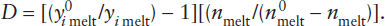

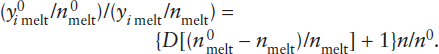

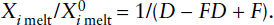

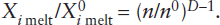

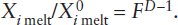

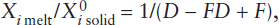

The extraction of the incompatible-element-enriched crust from the mantle has produced a complementary incompatible-element-depleted reservoir in the mantle. Can we use incompatible element concentrations to estimate what fraction of the mantle was involved in producing the crust?

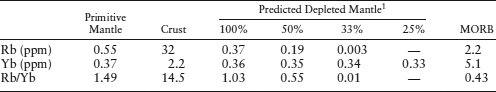

An approximate upper limit for mantle involvement can be calculated from mass balance considerations. Rubidium is a highly incompatible element, strongly enriched in the crust and depleted in MORB. Using the data in table 12.3, we can calculate the effect of extracting the crustal complement of incompatible Rb and relatively compatible Yb from varying amounts of primitive mantle. The relative masses of crust and mantle are 0.56% and 99.44%, respectively. The mass balance equation is:

Rb in primitive mantle = Rb in depleted mantle + Rb in crust,

or

mmantle (cpm) = nmmantle (cdm) + mcrust (cc),

where mmantle and mcrust are the mass fractions of the mantle and crust, n is the fractional degree of mantle depletion, and cpm, cdm, and cc are the concentrations of Rb in the primitive mantle, depleted mantle, and crust, respectively. Substituting the values in table 12.3 for 100% mantle depletion (n = 1) and solving for depleted mantle abundance of Rb (cdm) gives:

0.9944(0.55) = 1(0.9944)(cdm) + 0.0056(32),

or

cdm = 0.37 ppm Rb at 100% mantle depletion.

Similarly, we can use equation 12.2 to calculate the concentration of Rb and Yb at other degrees of mantle depletion (with n expressed as a fraction of total mantle), as shown in table 12.3. Also shown in table 12.3 is the measured weight ratio of Rb/Yb in MORB, which should reflect the ratio of these elements in the depleted mantle source region. By comparing the calculated Rb/Yb ratios at different degrees of mantle depletion with the measured MORB Rb/Yb ratio, we can estimate the degree of mantle involvement in crust formation. These simple calculations bracket the amount of mantle that has been affected by extraction of the crust between 33% and 50%. A similar result can be obtained by doing the same calculation with other incompatible elements, such as barium.

If we accept the base of the upper mantle as the 650 km discontinuity, then the upper mantle volume corresponds almost exactly to one-third of the entire mantle. Thus, it seems plausible that the upper mantle constitutes the part that has been partially melted to make the crust.

The contrasting ideas about mantle convection might be reconciled by a model that allows the Earth to lose heat by different mechanisms at different times. During normal periods (sometimes called Wilson cycles), such as we are experiencing now, upper and lower mantle convection cells are distinct, with most heat loss occurring at spreading centers through plate tectonics. Periodically, however, the Earth experiences whole-mantle convection, as large plumes of hot material reach the surface. During these MOMO (mantle overturn and major orogeny) episodes, accumulated cold slabs descend from the 650-km boundary into the lower mantle, and huge plumes rise from the core-mantle boundary. Eruption from the heads of such plumes produce large igneous provinces characterized by vast outpourings of basaltic magma (flood basalts). These contrasting styles are illustrated in figure 12.6. Flood basalt provinces form over relatively short time periods and may have caused significant environmental catastrophies, including some mass extinctions. After the plume head becomes depleted, the plume tail continues to be a source of magmas on a smaller scale. This usually produces a chain of volcanoes, as in Hawaii, as the overlying plate rides over the stationary hot spot.

TABLE 12.3. Rubidium and Ytterbium Mass Balance in the Mantle and Crust

From Taylor and McLennan (1985).

1Predicted concentrations at various degrees of mantle involvement.

FIG. 12.6. Comparison of convection during Wilson cycles and MOMO episodes. During most periods of the Earth’s history, including the present day, plate tectonics prevails and convection cells within the upper and lower mantles are largely isolated. During MOMO (mantle overturn and major orogeny) episodes, subducted slabs that have accumulated at the base of the upper mantle sink into the lower mantle, and multiple plumes rise from the core-mantle boundary.

Heat Exchange between Mantle and Core

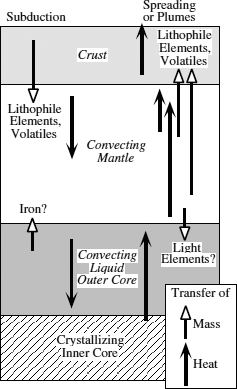

The metallic liquid in the Earth’s outer core is constantly crystallizing, so that the solid inner core is growing larger with time. Variations in the velocity of seismic waves traveling at different orientations within the inner core have been interpreted as evidence that the inner core may be one huge crystal. Exothermic crystallization yields large amounts of heat that stirs the outer core. Convection of this metallic liquid is responsible in part for the Earth’s magnetic field. Heat carried upward through the core is eventually transferred to the bottom of the mantle.

Although most of the flux across the core-mantle boundary is heat, there is some suggestion of mass transfer as well. Reactions between liquid metal and perovskite in the lower mantle have been postulated. If such reactions occur, this might provide a mechanism for adding a light element to the outer core, so in this case, mass transfer would be from the mantle downward into the core. Small amounts of core material might also intrude into the lowermost mantle and eventually be entrained in mantle convection cells. The evidence for this, too, is speculative, based on small anomalies in the isotopic composition of the siderophile element iridium. Heat transfer through the core-mantle boundary, though, is unambiguous. It is a major driving force in mantle convection and must be responsible for mantle plumes.

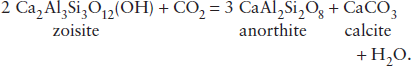

Fluids and the Irreversible Formation of Continental Crust

Production of continental crust occurs primarily above subduction zones, where melting of the mantle wedge above the subducted slab occurs. At the time it is subducted, oceanic lithosphere has been hydrated by reactions with seawater, so that water is also carried downward into the upper mantle. When the slab reaches a depth appropriate for transformation to eclogite, the water is driven off and migrates into the overlying wedge of mantle peridotite. Melting under hydrous conditions can produce andesitic magmas with higher silica contents than basalt. Andesitic magmas normally contain a few percent of dissolved water, which is cycled back to the surface when the magmas outgas on eruption. Magmas that are erupted at subduction zones beneath continents immediately become continental crust. Where subduction occurs beneath oceanic lithosphere, magmatic arcs form and may be eventually become accreted to continents.

The production of continental crust appears to be unidirectional. The aggregate density of “granitic” continental crust is too low for this material to be subducted. Consequently, once continental crust forms, it is likely to remain at the Earth’s surface. This is in marked contrast to oceanic crust, which is consumed in subduction zones at virtually the same rate that it is generated at midocean ridges. In fact, the only way that oceanic crust can escape being reincorporated into the mantle is by its accidental accretion onto continents by tectonic processes (producing ophiolites).

As the continental crust accumulated over time, its composition apparently changed. Scott McLennan (1982) found that Archean clastic sedimentary rocks were depleted in silicon and potassium and enriched in sodium, calcium, and magnesium relative to post-Archean rocks. These data indicate that the sources of Archean sediments were more mafic than for Proterozoic sediments. In an exhaustive survey of 45,000 analyses of common crustal rocks, A. B. Ronov and his collaborators (1988) determined that progressive changes occurred in the compositions of shales, sandstones, basalts, and granitic rocks. Each of these lithologies showed decreases in magnesium, nickel, cobalt, and chromium and increases in potassium, rubidium, and other lithophile elements with increasing time. There is disagreement about whether these secular changes are continuous or a sharp break occurs at the Archean-Proterozoic boundary 2.5 billion years ago.

Models for the growth of continental crust fall into two basic categories: early formation of virtually the entire crust with subsequent recycling, or continuous or episodic increase in the amount of crust throughout geologic time. Although this remains a contentious subject, continuous or quasicontinuous growth models are most popular. Ross Taylor and Scott McLennan (1985) argued that 90% of the continental crust was in place by the end of the Archean. They also proposed that most (60–75%) of the crust was produced episodically during the period 3.2 to 2.5 billion years ago. This transition might explain, in part, the compositional variations between Archean and post-Archean crust.

From our discussion of these interactions between crust, mantle, and core, we can see that the interior parts of the Earth constitute a grand geochemical system. The fluxes of materials and energy between these reservoirs are summarized in figure 12.7. Heat and possibly some matter is exchanged between core and mantle. Heat and matter in the form of ascending magmas or subducted lithosphere are exchanged between mantle and crust. The Earth is continuing to differentiate irreversibly in such a way that the mantle is depleted in fusible components, which are ultimately added to continental crust. Although continental crust, once formed, cannot be recycled, the fluids that play an important role in its formation are cycled between mantle and crust at subduction zones. All of these fluxes are driven by thermal convection. In the following sections, we examine in more detail how these geochemical interactions take place.

FIG. 12.7. Cartoon summarizing the fluxes of heat and matter between the core, mantle, and crust reservoirs.

Because mass transfer from the mantle to the crust commonly involves magmas (although hot, solid materials also migrate in rising plumes), we consider the melting process in some detail. Melting is probably never complete, and partial melts and residues usually exhibit significant chemical differences.

The transformation from the crystalline to the liquid state is not very well understood at the atomic or molecular level. One (largely chemical) description of the melting process is that it results from increasing the vibrational stretching of bonds between atoms to the point at which the weakest bonds are severed. Another (primarily structural) view of melting is that it parallels a change from long-range crystallographic order to the short-range order characteristic of melts. X-ray diffraction studies of minerals at low and high temperatures have shown no significant distortions of crystal structures as melting temperatures are approached, but unit cell volumes increase. However, more work needs to be done before the physics of the melting process can be detailed.

Thermodynamic Effects of Melting

Melting, like other phase transformations in the mantle, results in discontinuous changes in the thermodynamic properties of the system. A sudden increase in entropy, reflecting the higher state of atomic disorder in liquids relative to crystals, is probably the most obvious thermodynamic change. More important from the geochemist’s point of view, however, is the increase in enthalpy that accompanies melting. The thermal energy necessary to convert rock at a particular temperature to liquid at that same temperature is the enthalpy of melting, also called the latent heat of fusion. This is the thermal energy required beyond that necessary to raise the temperature of the rock to its melting point.

The enthalpy of melting can be measured by dropping crystals or glass into a calorimeter at temperatures just above and just below the melting point. (Calorimetry was mentioned in chapter 3.) From the rise in temperature of the calorimeter bath, or change in the proportion of crystals and liquid, the energy released by each state of the material can be evaluated. It is possible to calculate the enthalpy of melting for more complex systems that consist of several crystalline phases, provided that the phase diagram relating these phases has been determined and the values of ΔHm for the individual phases are known, as illustrated in worked problem 12.3.

Worked Problem 12.3

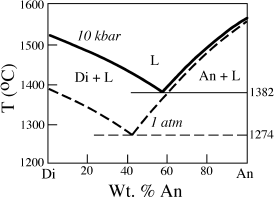

How much thermal energy is required to melt a mixture of diopside and anorthite, initially at 0°C? Let’s assume that the proportions of these two minerals correspond to the eutectic composition in the system diopside-anorthite (you may wish to review this phase diagram, illlustrated at the bottom of fig. 10.6).

This calculation is performed in two steps. First, we must determine the energy required to raise the temperature of this material from 0°C to the melting point, which is 1274°C for a eutectic composition in this system (see fig. 10.6). Recall that the eutectic represents the composition of the last liquid to crystallize or the first liquid to form during partial melting. From the phase diagram, we find that the eutectic composition (in wt %) is Di58An42. The heat capacity (Δ P) for diopside is 100.40 J mol−1 K−1 = 23.99 cal mol−1 K−1, and that for anorthite is 146.30 J mol−1 K−1 = 34.97 cal mol−1 K−1 (Robie et al. 1978). We convert these heat capacities into units of cal g−1 K−1 because the eutectic composition is given in units of weight. Division by the gram formula weights for diopside (216.55 g mol−1) and anorthite (278.21 g mol−1) gives Δ

P) for diopside is 100.40 J mol−1 K−1 = 23.99 cal mol−1 K−1, and that for anorthite is 146.30 J mol−1 K−1 = 34.97 cal mol−1 K−1 (Robie et al. 1978). We convert these heat capacities into units of cal g−1 K−1 because the eutectic composition is given in units of weight. Division by the gram formula weights for diopside (216.55 g mol−1) and anorthite (278.21 g mol−1) gives Δ P = 0.1109 cal g−1 K−1 for diopside and 0.1257 cal g−1 K−1 for anorthite. The energy required to raise the temperature of this mixture by 1274° is therefore:

P = 0.1109 cal g−1 K−1 for diopside and 0.1257 cal g−1 K−1 for anorthite. The energy required to raise the temperature of this mixture by 1274° is therefore:

(0.1109 cal g−1 K−1)(1274 K)(0.58) + (0.1257 cal g−1 K−1)(1274 K)(0.42) = 149.21 cal g−1.

The second step is to calculate the enthalpy of melting of this eutectic mixture. Δ m for diopside is 77.40 kJ mol−1 = 18,345 cal mol−1 and for anorthite is 81.00 kJ mol−1 = 19,359 cal mol−1. Division by the appropriate gram formula weights gives Δ

m for diopside is 77.40 kJ mol−1 = 18,345 cal mol−1 and for anorthite is 81.00 kJ mol−1 = 19,359 cal mol−1. Division by the appropriate gram formula weights gives Δ m for diopside of 84.71 cal g−1 and for anorthite of 69.58 cal g−1. Multiplying these values by the appropriate fractions for the eutectic composition yields:

m for diopside of 84.71 cal g−1 and for anorthite of 69.58 cal g−1. Multiplying these values by the appropriate fractions for the eutectic composition yields:

(84.71 cal g−1)(0.58) + (69.58 cal g−1)(0.42) = 78.36 cal g−1.

The heats of mixing of these liquids are so small that they can be neglected. Thus, the total thermal energy necessary for this melting process is the sum of the energy required to raise the temperature of a eutectic mixture of diopside and anorthite to the melting point plus the energy required to transform this mixture into a liquid at that same temperature:

149.21 cal g−1 + 78.36 cal g−1 = 227.51 cal g−1.

A realistic value for the enthalpy of melting of mantle peridotite is difficult to obtain, because of the unknown effects of high pressure and of other solid solution components in pyroxenes, olivine, and garnet or spinel. One commonly quoted value for garnet peridotite at 40 kbar pressure is 135 cal g−1. For melting to occur in the mantle, this amount of thermal energy must be supplied in excess of the heat necessary to bring mantle rock to the melting temperature.

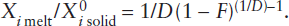

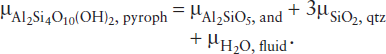

If the temperature of mantle peridotite is increased to the melting point and some extra thermal energy is added for the enthalpy of melting, magma is produced. As in the case of eutectic melting in the diopside-anorthite system discussed in worked problem 12.3, fusion begins at some invariant point, so that several phases melt simultaneously. The melting process can be described in several ways. Equilibrium melting (also called batch melting) is a relatively simple process in which the liquid remains at the site of melting in chemical equilibrium with the solid residue until mechanical conditions allow it to escape as a single “batch” of magma. Fractional melting involves continuous extraction of melt from the system as it forms, thereby preventing reaction with the solid residue. Fractional melting can be visualized as a large number of infinitely small equilibrium melting events. Incremental batch melting lies between these two extremes, with melts extracted from the system at discrete intervals.

Worked Problem 12.4

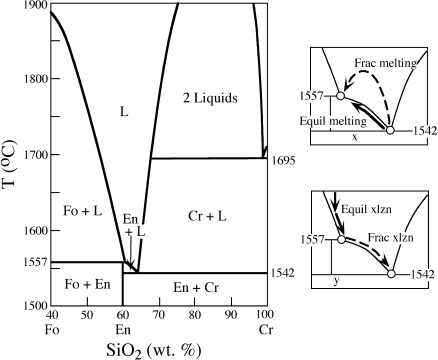

To illustrate the distinction between equilibrium and fractional melting, let’s examine fusion processes in the two-component system forsterite-silica, shown in figure 12.8. Describe melting in this system under equilibrium and fractional conditions.

This system contains a peritectic point between the compositions of forsterite (Fo) and enstatite (En) and a eutectic between the compositions of enstatite and cristobalite (Cr), seen more clearly in the schematic insets. If enough heat is available to raise the temperature of the system to 1542°C and offset the enthalpy of melting, any composition between En and Cr begins melting at the eutectic, with both solid phases entering the melt. For small degrees of partial melting under equilibrium conditions, the melt will have the eutectic composition. With further melting, one phase usually becomes exhausted from the solid residue before the other does. Begin, for example, with a composition x that plots between the peritectic and the eutectic, shown in the upper inset in figure 12.8. As this mixture of En + Cr melts, Cr will be exhausted from the residue first. As melting continues under equilibrium conditions, the composition of the liquid leaves the eutectic and follows the liquidus upward, all the while melting enstatite. Total melting occurs when the liquid reaches the starting composition. This path is the reverse of equilibrium crystallization.

Fractional melting produces a sequence of distinct melts rather than one evolving melt composition. Again, consider the same mixture x of enstatite and cristobalite as before, shown in the upper inset. The initially formed liquid, which has the eutectic composition, is removed from the system as it forms, so the composition of the remaining solid shifts toward En. After Cr is exhausted from the residue, the temperature must increase to the peritectic temperature for any further melting to occur. When the temperature reaches 1557°C, En melts incongruently to Fo plus liquid, and the liquid is immediately removed. After all the En is converted to Fo, no further melting can occur until the liquid reaches the melting point for pure Fo. Fractional melting, if carried to completion, thus produces three batches of melt having distinct compositions, whereas equilibrium melting results in one evolving but (at any time) homogeneous melt.

FIG. 12.8. Phase diagram for the system forsterite (Mg2SiO4)-silica (SiO2). The insets illustrate the eutectic and peritectic in this system; the upper inset (melting paths) is used in worked problem 12.4, and the lower inset (crystallization paths) in worked problem 12.5. The silica-rich side of the diagram contains a region of silicate liquid immiscibility (“2 Liquids”).

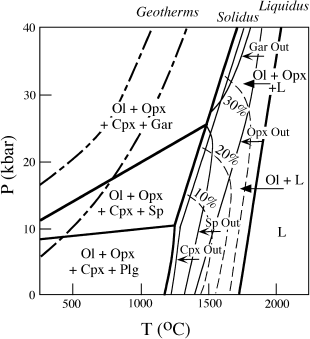

Some details of the melting relationships of mantle peridotite are illustrated schematically in figure 12.9. Phase changes for the stable aluminum-bearing mineral in fertile peridotites are illustrated at temperatures below the solidus. Melting of peridotite begins as its temperature is raised just above the solidus. As temperature increases further, clinopyroxene, spinel, and garnet are completely melted and thereby exhausted from the solid residue (as indicated by lines labeled Cpx-out, Sp-out, and Gar-out, respectively). This all occurs within ~50°C of the solidus, producing a wide P-T field for the coexistence of olivine + orthopyroxene with liquid. The olivine + orthopyroxene residue is the depleted peridotite that was discussed earlier.

FIG. 12.9. Schematic phase diagram for mantle peridotite, illustrating the effects of partial melting. The solidus and liquidus are indicated by heavy lines. The aluminous phase changes from plagioclase (Plg) to spinel (Sp) and then garnet (Gar) with increasing pressure. With increasing temperature, first clinopyroxene (Cpx) and then spinel or garnet are exhausted from the residue, leaving olivine (Ol) + orthopyroxene (Opx) or olivine alone. The dashed lines are contours of the percentage of dissolved olivine in the melt; they show that with increasing pressure, magmas become more olivine rich. Also illustrated are typical geothermal gradients for oceanic and continental regions.

The composition of the basaltic liquid produced by partial melting of peridotite changes with pressure, becoming less silica rich at higher pressure. Lower silica contents of liquids increase the proportion of olivine that can ultimately crystallize from the melt on cooling; the percentage of olivine in the melt is contoured as dashed lines in figure 12.9. Variation in pressure (or depth) of magma generation thus results in basaltic melts ranging from tholeiite (the common lava composition at mid-ocean ridges) at modest pressures to more olivine-rich alkali basalt and basanite (which occur at hot spots) at higher pressures.

The geothermal gradient (also called the geotherm) is the rate of increase of temperature with pressure, or depth. In an earlier section of this chapter, we noted that the elastic properties of the low-velocity zones in the mantle are consistent with partial melting. However, from an examination of the relative positions of geotherms and the peridotite solidus in figure 12.9, there is no apparent reason for incipient melting in this zone or, for that matter, anywhere else in the mantle. How can we then account for magma generation? There is no simple answer to this question, but there are at least three intriguing possibilities: localized temperature increase, decompression, and addition of volatiles. Let’s see how each of these could cause melting.

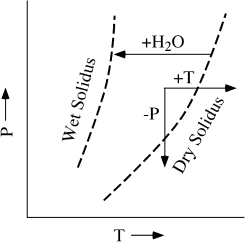

Simply raising the temperature of a rock (the path labeled +T in fig. 12.10) is the most obvious mechanism by which melting can occur; this has sometimes been called the hot plate model. However, in considering this model, we should keep in mind the difference in magnitude between the enthalpy of melting and the heat capacity for silicate minerals. Δ P values are generally several hundred times lower than corresponding Δ

P values are generally several hundred times lower than corresponding Δ m values (compare the values for diopside and for anorthite in worked problem 12.3), so it is much easier to raise the temperature of a rock than to produce a significant amount of partial melt from it. Melting consumes large quantities of thermal energy, moderating temperature variations within the system in its melting range. Even so, it may be possible to have localized mantle heating that produces magma. Frictional heating of subducted lithospheric slabs or dissipation of tidal energy due to the gravitation attraction of the Sun and Moon have been suggested as possible causes of localized heating in the mantle. More plausible is local heating of the lower crust in response to underplating by mantle-derived magmas.

m values (compare the values for diopside and for anorthite in worked problem 12.3), so it is much easier to raise the temperature of a rock than to produce a significant amount of partial melt from it. Melting consumes large quantities of thermal energy, moderating temperature variations within the system in its melting range. Even so, it may be possible to have localized mantle heating that produces magma. Frictional heating of subducted lithospheric slabs or dissipation of tidal energy due to the gravitation attraction of the Sun and Moon have been suggested as possible causes of localized heating in the mantle. More plausible is local heating of the lower crust in response to underplating by mantle-derived magmas.

FIG. 12.10. P-T diagram illustrating three possible ways that mantle rocks may melt. Increase in temperature (+T path) could result from localized concentration of heat producing radionuclides or underplating by other magmas. Decrease in confining pressure (−P path) may occur because of diapiric upwelling of ductile mantle rock. Addition of a fluid phase (+H2O path) depresses the melting curve to lower temperature for the same pressure.

The most important mechanism for melting mantle rocks is almost certainly the release of pressure, caused by the convective rise of hot, plastic mantle rocks. The effect of decreasing confining pressure is generally to lower the solidus temperature. One example, in the system diopside-anorthite, is illustrated in figure 12.11. The eutectic temperature, which is the point at which partial melting begins, is decreased by >100°C in going from 10 kbar to 1 atm pressure. The position of the eutectic point also shifts, because the melting point of diopside increases much more for a given pressure change than does that of anorthite. Therefore, the Di field is enlarged with increasing pressure at the expense of the An field. The effect of decreasing pressure on the solidus of mantle peridotite can be seen in figure 12.9. Because of the positive slope of this melting curve in P-T space, decompression of solid rock can induce melting, as illustrated by the path labeled −P in figure 12.10. Because decompression melting occurs at constant temperature (we used the term adiabatic to describe such a process in chapter 3) over some interval of pressure, conventional T-X phase diagrams (which are drawn for a fixed pressure) cannot really be used to understand this process. A recent innovation in visualizing polybaric melting is discussed in an accompanying box.

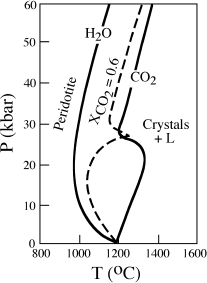

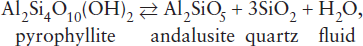

Changes in the composition of a rock system due to gain or loss of volatiles, principally H2O and CO2, are also potentially important in facilitating melting. Water lowers the solidus of peridotite, as illustrated in figure 12.13 by the wet solidus curve. The addition of water to a dry peridotite that is already above the wet solidus will cause spontaneous melting, as illustrated by the +H2O path in figure 12.10. We have already discussed how an influx of water into the mantle can be caused by dehydration reactions in a subducted slab of hydrated lithosphere. The effect of the addition of CO2 to mantle peridotite is less drastic than for H2O, but still significant. The solidus of peridotite in the presence of CO2 is illustrated in figure 12.13 by the line labeled CO2. When the fluid phase contains both H2O and CO2, the effect on the peridotite melting curve is complicated. A solidus for a mixed fluid composition of XCO2 = 0.6 is illustrated in figure 12.13. At modest pressures of 10 to 20 kbar, water predominates, because it is most soluble in the melt; but at higher pressures, the effect of CO2 becomes marked as its solubility increases.

Both of these volatile components also strongly influence the compositions of the magmas that are generated. Water selectively dissolves silica out of mantle phases before melting occurs; as soon as the melt forms, it effectively swallows this fluid and thereby becomes richer in silica (sometimes producing andesites rather than basalts). However, CO2 favors the production of alkalic magmas poor in silica (nephelinites and kimberlites).

FIG. 12.11. Phase diagram for the system diopside (CaMgSi2O6)-anorthite (CaAl2Si2O8), demonstrating the effect of increasing confining pressure on melting relationships. Lowering pressure from 10 kbar to 1 atm results in a decrease in the eutectic melting temperature of >100°. (Based on experiments by Presnall et al. 1978.)

DECOMPRESSION MELTING OF THE MANTLE

T-X phase diagrams of the type considered in chapter 10 are appropriate for understanding how magmas and crystals behave when temperature and composition are variables and pressure is constant. We have already seen that the Gibbs free energy is minimized at equilibrium under such conditions. However, decompression melting, which is the most important process by which magmas are generated, cannot be visualized using the conventional T-X phase diagrams. What are the appropriate variables when melting occurs over a range of pressures?

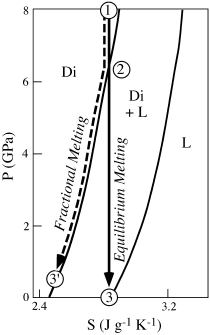

If decompression melting is adiabatic (q = 0) and reversible (dq = TdS, where S is the entropy), the process is isentropic (dS = 0). The appropriate variables for visualizing polybaric melting are thus P and S, with composition (X) held constant. At equilibrium under these conditions, enthalpy rather than free energy is minimized.

Figure 12.12 illustrates a schematic P-S diagram for a one-component system with two phases—solid and liquid. The diagram resembles the familiar T-X phase loop bounded by a solidus and a liquidus for a binary system, and it can be read in much the same way. Isentropic decompression is indicated on this diagram by a vertical (decreasing P, constant S) line. At point 1, the system is entirely solid, but it begins to melt at point 2, where it passes into the two-phase field. At any given pressure within the two-phase field, the relative proportions of solid and liquid can be determined by applying the lever rule to a horizontal line passing through the point. Under equilibrium melting conditions, melting is complete at point 3.

The same diagram can also be used to model fractional melting. Strictly speaking, this process is neither adiabatic nor isentropic, because melt leaving the system carries entropy with it. However, each small increment of melting can be considered isentropic. A solid having a value of entropy given by point 1 undergoes pressure release and begins to melt when it reaches point 2. As fractional melting proceeds, the system constantly changes composition and the solid residue follows the solidus, that is, the path from 2 to 3′. At the beginning of melting at point 2, the first increment of melt is identical, whether melting is equilibrium or fractional. However, for fractional melting, although the mass of the solid residue continuously decreases, it is not possible to melt the solid completely by this process. As a consequence, fractional melting produces less melt than equilibrium melting for a given decompression interval.

FIG. 12.12. Pressure-entropy diagram illustrating melting of diopside under equilibrium (path 1-2-3) and fractional (path 1-2-3′) conditions. This diagram allows us to visualize how melting takes place over a range of decreasing pressures typical of those experienced in an ascending mantle plume.

One subtlety of the P-S diagram is that the amount of melt generated per decrement of pressure increases with decreasing pressure. Using figure 12.12, you can demonstrate this for yourself by comparing the pressure intervals required to produce 50% melting and 100% melting under equilibrium melting conditions. This effect results from the curvature of the liquidus and the solidus. The conclusion that melting accelerates with decompression cannot be worked out by studying this process on a P-T diagram. The effect is appreciable in natural rock systems and probably accounts for most melts generated within the mantle. Complications result from phase changes in the mantle, which produce nonuniform zones of melting during upwelling, as discussed by Paul Asimow and his collaborators (1995).

FIG. 12.13. Phase diagram showing the solidus in the system peridotite-CO2-H2O. Melting in the presence of pure water occurs at lower temperatures than for pure CO2. The dashed line labeled XCO2 = 0.6 corresponds to peridotite melting with a mixed fluid of that composition. Water is the most important volatile species at pressures of less than ∼20 kbar, but CO2 becomes increasingly important at higher pressures because of its increased solubility in the melt.

Concluding this section on melting, we summarize some of these concepts by relating current ideas about how mantle-derived magmas are formed in various tectonic settings: (1) Partial melting of relatively dry peridotite accounts for the vast outpourings of tholeiitic basalt at midocean ridges. This style of melting is initiated by decompression resulting from the rise of mantle under spreading centers. (2) Hydrated slabs of oceanic lithosphere subducted at convergent plate boundaries transform into eclogite at depths of ∼100 km, thereby releasing water into the overlying wedge of mantle peridotite. This addition of H2O may cause melting to produce siliceous magmas, such as andesites. (3) At substantially deeper levels in the mantle, localized heating (probably by heat generated through crystallization of the inner core) at hot spots generates alkalic magmas. Magmas underplating the crust can also induce melting in the overlying crustal rocks by local increase in temperature.

DIFFERENTIATION IN MELT-CRYSTAL SYSTEMS

In the preceding section, we painted a broad picture of melting processes in the mantle, gleaned mostly from studies of volcanic rocks. In reality, the picture is much fuzzier, because very few mantle-derived magmas arrive at the Earth’s surface in pristine condition. Most have been altered in composition (differentiated) to various degrees. We will now see how that happens.

The most common mechanism by which magmas are differentiated is fractional crystallization: the physical separation of crystals and liquid so that these phases can no longer maintain equilibrium. Crystals may be isolated from their parent magma through gravity settling (or rarely, floating), or they may be carried to the bottom of a magma chamber and deposited by convection currents. A pile of accumulated crystals may be purified further by squeezing out of some of the interstitial liquid as the overburden of additional crystals accumulates. Rapid crystallization, in which the reaction of melt with solid phases cannot keep up with falling temperature and advancing solidification, can produce compositionally zoned crystals. This kinetic isolation of the interiors of crystals prevents their equilibration with the liquid and thus can also be considered as fractional crystallization.

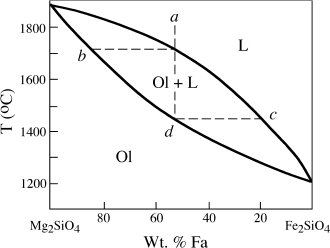

Unlike equilibrium crystallization and melting, fractional crystallization is not the reverse of fractional melting. To see how fractional crystallization differs from equilibrium crystallization, let’s consider two binary phase diagrams that involve olivine.

Worked Problem 12.5

Fractional melting in the system forsterite-silica has already been discussed in worked problem 12.4. Using the phase diagram for this system in figure 12.8, trace the fractional crystallization paths of melts having compositions x and y.

Cooling of any melt composition to the liquidus causes the appropriate solid phase to appear. If we begin with a liquid of composition x, removal of enstatite (En) crystals as they form drives the residual liquid composition toward the eutectic. When this point is reached, both En and crystobalite (Cr) separate from the melt. The liquid trajectory is, in this case, no different from that for equilibrium crystallization, but in fractional crystallization, the bulk composition of the magma changes because crystals are removed. Under equilibrium conditions, these crystals remain suspended in the magma and become part of the resulting erupted lava and igneous rock.

FIG. 12.14. Phase diagram for the system forsterite (Mg2SiO4)-fayalite (Fe2SiO4), illustrating how fractional crystallization affects a solid solution series. Olivine crystals forming from a melt with initial composition a will range in composition from b to some point past d.

Now consider a liquid having composition y, shown in the lower inset of figure 12.8. The first solid phase to form is now forsterite (Fo). Under equilibrium conditions, the liquid should follow the Fo liquidus to intersect the peritectic, at which point it reacts with already crystallized Fo to produce En. Under fractional crystallization conditions, Fo is physically removed from the system as it forms, so that there is none of this phase to react with the melt at the peritectic temperature. Thus, there is no Fo + L → En reaction to cause the liquid to delay at the peritectic. The cooling liquid slides through the peritectic and immediately begins to crystallize En rather than Fo. The melt composition continues toward the eutectic. Under conditions of perfect fractional crystallization, the liquid reaches the eutectic, but such ideal conditions do not exist in nature, so that the liquid may be exhausted at some point before the eutectic is reached.

Olivine that crystallizes from real magmas is, of course, not pure forsterite, but a solid solution of Mg- and Fe-rich end members. The phase diagram for the system forsterite (Fo)-fayalite (Fa), shown in figure 12.14, is very similar to one for the plagioclase system that was used in chapter 10 to illustrate solid solution behavior. Crystallization of a liquid of composition a in figure 12.14 initially produces olivine of composition b. If equilibrium were achieved, this olivine would then react continuously with the melt to form more Fe-rich compositions, ultimately having composition d, as the last drop of liquid is exhausted. Under fractional crystallization conditions, however, the initially formed Mg-rich olivine is removed from the melt, so that this reaction cannot take place. Hence, the liquid crystallizes a range of olivines that are progressively more Fe-rich, from composition b to d and beyond. Again, under conditions of perfect fractional crystallization, the liquid should ultimately reach the composition of pure fayalite, but in real systems we cannot specify the exact point at which the last liquid will solidify, only that the liquid composition continues past point c.

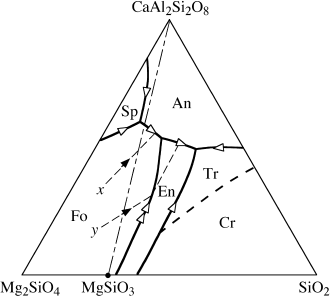

Fractional crystallization affects ternary systems in an analogous manner. Reaction curves, the ternary equivalents of binary peritectic points, no longer define the compositions of fractionating liquids, because there are no solid phases to react. Fractional crystallization in a more complex system is described in worked problem 12.6.

Worked Problem 12.6

Phase relationships in the system forsterite-anorthite-silica are shown in figure 12.15. This problem will not make sense to you, unless you have studied the box on ternary phase diagrams in chapter 10. (Fig 12.15 actually represents a pseudoternary rather than a ternary system, because the primary phase field of spinel appears in the diagram, but the composition of spinel lies outside of this plane. The only complication that this situation presents is that we cannot specify the crystallization path of liquids within the spinel field, because we do not know where the projection of spinel plots on this diagram.) We have already applied Alkemade’s Theorem to identify the various subtraction and reaction curves (single- and double-headed arrows, respectively) in this diagram. Describe fractional crystallization paths for liquids of composition x and y in figure 12.15.

FIG. 12.15. Phase diagram for the pseudoternary system forsterite (Mg2SiO4)-anorthite (CaAl2Si2O8)-silica (SiO2). The compositions of liquids derived by fractional crystallization of melt compositions x and y are illustrated by dashed lines.

Liquid x cools to the Fo liquidus and then changes in composition away from the forsterite apex as this phase is removed. When the liquid composition intersects the subtraction curve, Fo + An crystallize and are separated out together. The liquid moves to and through the tributary reaction point, because there is no Fo left in contact with melt to react to form En. The liquid continues toward the ternary eutectic point between En, An, and Tr (tridymite). We cannot specify the exact point where the liquid phase will be exhausted.

A liquid with composition y will fractionate Fo until it reaches the curve for the reaction Fo + L → En. Because there is no Fo left to react, the melt steps over this curve into the En primary phase field. At this point, En begins to crystallize, and the liquid composition moves directly away from the enstatite composition. Continued En fractionation drives the melt to the subtraction curve, and An joins the fractionating assemblage. The liquid then follows the subtraction curve toward the ternary eutectic.

Consideration of these experimentally derived phase diagrams provides some indication of the ways in which magmas might differentiate, but what is the evidence that fractional crystallization actually occurs as a widespread phenomenon in magmatic systems? To answer this question, we must examine real igneous rocks for the effects of this process. Experimental studies of most basaltic rocks indicate that they are multiply saturated at low pressures; that is, several minerals begin to crystallize at virtually the same temperature. We would expect that kind of behavior for partial melts formed at low pressure, because melting begins at invariant points (such as eutectics, the lowest temperature points at which liquids are stable). However, basaltic magmas are mantle derived and could not have formed at low pressures, so multiple saturation must have another explanation. That most basalts are already multiply saturated at low pressure suggests that they have experienced fractional crystallization.

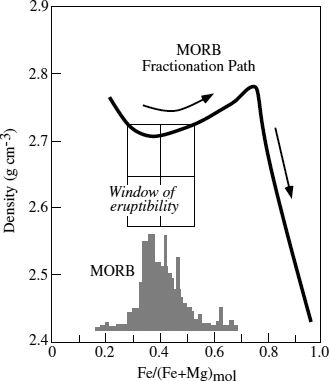

It has also been recognized that basalts cluster at certain preferred compositions. This observation is difficult to interpret if these are primitive magmas, unless the preferred compositions represent those of liquids in equilibrium with mantle peridotite at invariant points. An alternative (and more plausible) view is that these compositions represent points along a fractionation path that have special properties that allow the magmas to erupt. Edward Stolper and David Walker (1980) observed that the density of basaltic liquids first decreases and then increases during fractional crystallization, as illustrated in figure 12.16. In this diagram, fractionation is indicated by the progressive increase in the Fe/(Fe + Mg) ratio of the lavas. The commonly observed composition for MORB corresponds to that which has the minimum density. This fractionated composition would be most likely to ascend through the less dense crust and reach the planet’s surface.

FIG. 12.16. The density of fractionating basaltic magma as a function of composition. MORB compositions cluster at the minimum density, suggesting that only those compositions can ascend through the crust and erupt. (After Stolper and Walker 1980.)

Widespread fractional crystallization has obvious ramifications for what we can hope to learn about the mantle from igneous rocks. Crystallization experiments on fractionated rocks serve no purpose, except to understand the fractionation path itself. Luckily, a few unfractionated lavas somehow reach the surface, so judicious selection of samples for experiments can still provide useful information on mantle composition and melting.

The chemical changes wrought by fractional crystallization can be modeled quantitatively by using mixing calculations, which are most easily visualized from element variation diagrams. Figure 12.17 illustrates a magma’s chemical evolution, called the liquid line-of-descent, as it undergoes fractional crystallization. In figure 12.17a, crystals of composition A separate from liquid L1, with the result that the liquid composition is driven toward L2. In figure 12.17b,c, mixtures of two or three minerals crystallize simultaneously. The bulk composition of the extracted mineral assemblage is given in each case by A, and the liquid line-of-descent follows the path L1 → L2. In figure 12.17d, magma L1 first crystallizes mineral D and then D plus E, with the bulk composition of the fractionating assemblage represented by A. In this case, the liquid line-of-descent contains a kink, where the additional phase joins the crystallization sequence. A more complex case in which the fractionating phase is a solid solution is illustrated in figure 12.17e. Mineral AB is a solid solution of end members A and B, and the proportions of these end members change as temperature drops during crystallization. The trajectory of the liquid at any point is defined by a tangent to the liquid composition drawn from the composition of crystallizing AB. For example, the liquid path when A80B20 and A50B50 are extracted is shown by the tangents intersecting these compositions. In this case, the liquid line-of-descent traces out a curve. In all of these diagrams, the relative proportions of fractionating phases can be determined by application of the lever rule.

FIG. 12.17. Schematic chemical variation diagrams (axes can be any two elements or oxides) showing the liquid line-of-descent (L1 → L2) during fractional crystallization of one (a), two (b), or three (c) phases. In (d), the line-of-descent has an inflection due to late entry of a second phase. In (e), the line-of-descent is curved because of continuous change in the composition of an extracted solid solution phase.

In actual practice, the problem must be worked in reverse. A suite of volcanic rocks representing various points along a liquid line-of-descent is analyzed, and from these analyses, we must determine the fractionated phases. To test possible solutions to this problem, we require rock bulk compositions and the identities and compositions of possible extracted minerals. The latter may be obtained from petrographic observations and electron microprobe analyses of phenocrysts in the rocks. An example of such an exercise is given in worked problem 12.7.

Worked Problem 12.7

How can we test for fractional crystallization in real rocks? Assume that we have collected a suite of volcanic rock samples that we believe to be a fractionation sequence. The first step is to obtain bulk chemical analyses of the rocks. Petrographic observations indicate that three phases—olivine (Ol), plagioclase (Plg), and clinopyroxene (Cpx)—exist as phenocrysts in this suite of these rocks, and we have also chemically analyzed these minerals. Because these three phases were obviously on the liquidus at some point, we determine whether fractional crystallization of any one or some combination of them could have produced the observed liquid line of descent.

Figure 12.18 shows three different variation diagrams with the liquid line-of-descent (L1 → L2) defined by the analyzed bulk-rock compositions. Also shown are the compositions of the three phenocryst minerals. The information gained from any individual diagram is ambiguous, but we can compare diagrams to obtain a unique answer. In figure 12.18a, we see that the liquid line-of-descent is consistent with fractionation of Ol + Plg, Ol + Cpx, or Ol + Plg + Cpx. This diagram thus rules out Cpx + Plg as a possibility. In figure 12.18b, Ol + Cpx or Ol + Plg + Cpx are permissible assemblages that could be extracted to produce this sequence, but Ol + Plg (allowed in fig. 12.18a), is not allowed. The final distinction between Ol + Cpx and Ol + Plg + Cpx is made using figure 12.18c. This diagram indicates that fractionation of Ol + Cpx is the only internally consistent answer. The graphical testing of all interrelationships between elements is an important part of this kind of study; otherwise, we could have incorrectly assumed that all of the observed phenocrysts can fractionate to produce this liquid line-of-descent. Notice also that the relative proportions of olivine and clinopyroxene (approximately 1:1) in all the diagrams are the same, as deduced from application of the lever rule to the point at which the extrapolated liquid line-of-descent crosses the Ol-Cpx tie-line. Not only the identity of the fractionating phases but also their relative proportions should be consistent in this set of variation diagrams.

FIG. 12.18. Schematic chemical variation diagrams for a suite of basalts containing phenocrysts of olivine (Ol), clinopyroxene (Cpx), and plagioclase (Plg). The liquid line-of-descent defined by bulk chemical compositions of these basalts can be derived by fractional crystallization of Ol + Cpx.

As the number of possible fractionating phases or analyzed elements increases, it becomes more difficult to apply graphical methods. Numerical methods offer a real advantage in such situations. Several computer programs, commonly called petrologic mixing programs, are available for performing calculations of this type. These programs compute the composition of the parent magma by mixing the residual liquid with fractionating phases in various proportions. The answer is a best fit to the least-squares regression for the analyzed liquid line-of-descent.