|

|

Our goal in this chapter is to refresh concepts that you may have first encountered in a chemistry course and to put them in a geologic context, where they will be useful for the chapters to come. We begin with a review of atomic structure and the periodic properties of the elements, focusing carefully on the electronic structure of the atom. This leads us to consider the nature of chemical bonds and the effects of bond type on the properties of compounds. These should be familiar topics, but they may look different through the lens of geochemistry.

ELEMENTS, ATOMS, AND THE STRUCTURE OF MATTER

Elements and the Periodic Table

Long before the seventeenth century, alchemists determined that most pure substances can be broken down, sometimes with difficulty, into simpler substances. They reasoned, therefore, that all matter must ultimately be made of a few kinds of material, commonly called elements. Following the lead of Aristotle, they identified these as earth, air, fire, and water. Without stretching too far, we can recognize a parallel to what chemists today call the three states of matter (solid, liquid, and gas) and energy. These are useful distinctions to make, but unfortunately, medieval alchemists had difficulty explaining how the Aristotelian elements could combine to form everyday materials. Two key concepts were missing: the idea that matter is composed of individual particles (atoms) and the notion that compounds are made of atoms held together electrostatically.

Philosophers claim that the atomic theory had its roots in ancient Greece. The sage Democritus declared that the motions we observe in the natural world can only be possible if matter consists of an infinite number of infinitesimal particles separated by void. This was not a scientific hypothesis, however, but a proposition for debate. Democritus had neither the means nor the inclination to test his idea. Still, for more than 2000 years, scholars argued about whether matter was infinitely divisible or made of tiny, discrete particles. The issue was resolved only when scientists finally recognized the difference between chemical compounds, on the one hand, and alloys or mixtures on the other.

Through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, scientists gradually convinced themselves that the Aristotelian earth, in particular, was not a fundamental substance. Analytical techniques improved and empirical rules began to emerge. Robert Boyle, for example, declared that a substance cannot be an element if it loses weight during a chemical change, thus clarifying the distinction between pure elements and compounds. By the 1790s, systematic purification had yielded roughly a third of the elements known today. Most of these are metals: copper, gold, silver, lead, zinc, iron, magnesium, mercury, and tungsten, to name a few.

Geologists might argue, however, that the greatest accomplishment of that era was the isolation of nonmetallic elements. In particular, the discovery of oxygen in the 1780s (attributed independently and with great controversy to Joseph Priestley, Karl Scheele, and Antoine Lavoisier) clarified the mysterious relationship between metallic elements and the clearly nonmetallic minerals that constitute most of the Earth’s crust. The most common minerals were revealed as complex oxides of metallic elements. This realization, coming in the midst of an explosion of national investments in mining and metallurgy in Europe, was perhaps the first major step toward modern geochemistry. It was also a marked change in direction for science at large. Lavoisier, Joseph Louis Proust, Jeremias Benjamin Richter, Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac, and others established by experimentation that oxygen and other gaseous elements combine in fixed proportions to form compounds. Water, for example, is always 11.2% hydrogen and 88.8% oxygen by weight.

Fixed proportions suggest a systematic arrangement of discrete particles. In 1805, John Dalton proposed four postulates:

These postulates have now been revised, particularly in light of the discovery of radioactivity in the late 1800s. We now realize, for example, that energy and matter are interchangeable, and that atoms can be “smashed” into smaller particles. Still, for most chemical purposes, the postulates have proved correct.

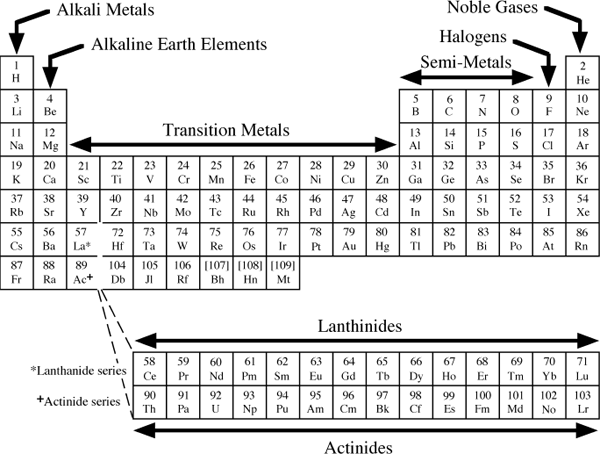

Once a rational basis for the atomic theory had been established, the number of newly isolated elements began to grow. Chemists began recognizing relationships among the elements. Johann Dobereiner, in 1829, noted several triads of elements with similar chemical properties. In each triad, the atomic mass of one element was nearly equal to the average of the atomic masses of the other two. Chlorine, bromine, and iodine, for example, are all corrosive, colored, diatomic gases; the atomic mass of bromine is halfway between the masses of chlorine and iodine. Over the next 40 years, scientists documented other patterns when they arranged the elements in order of increasing atomic mass. Finally, in 1869, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev made a careful reevaluation of what was known about the elements, corrected some erroneous values, and proposed the system known today as the periodic table (fig. 2.1).

We return several times in this chapter to examine the periodic properties of elements and to offer explanations for their behavior in the Earth. For a first look, consider figure 2.2, in which we compare the melting and boiling points of elements in the first three main rows of the periodic table (omitting for now the elements scandium through zinc: the first transition series). The trend toward increasing values near the center of each row is unmistakable. Mendeleev was able to predict the properties of germanium, as yet undiscovered in the 1860s, by using trends like these.

Although the periodic table was developed empirically, its structure suggests that atoms of each element are built according to regular architectural rules, thereby offering some hope for figuring out what those rules are. By the end of the nineteenth century, chemists understood that atoms are made of three fundamental types of particles. The heaviest of these, protons and neutrons., are tightly packed into the nucleus of the atom, where they constitute very little of the atom’s volume but virtually all of its mass. The lightest particles, electrons, orbit the nucleus in an “electron cloud” that is largely empty space. Protons and electrons are opposing halves of an electrical system that controls most of the atom’s chemical properties. By convention, each proton is said to have a unit of positive charge, and each electron has an equal unit of negative charge.

The Atomic Nucleus and Isotopes

Three numbers, describing the abundance and type of nuclear particles in an atom, are in common use. The first of these, symbolized by the letter Z, counts the number of protons and is known as the atomic number. This number identifies which element the atom represents (any atom with Z = 8, for example, is an atom of oxygen, one with Z = 16 is sulfur, and so forth). Because an electrically neutral atom must have equal numbers of protons and electrons, Z also tells us the number of electrons in an uncharged atom. The second useful number is the neutron number, symbolized by the letter N. Within limits imposed by the attractive and repulsive forces among nuclear particles, atoms of any element may have different numbers of neutrons. Atoms for which Z is the same but N is different are called isotopes.

FIG. 2.1. The elements are described in this periodic table by their atomic number and symbol. The names dubnium (Db), joliotium (Jl), rutherfordium (Rf), bohrium (Bh), hahnium (Hn) and meitnerium (Mt) for elements 104–109 have been proposed but not yet formally approved.

FIG. 2.2. Mendeleev suggested that the elements could be tabulated in a way that emphasizes trends in chemical properties. For example, with some exceptions (boron’s boiling point and gallium’s melting point, in column 3), melting and boiling points increase toward the middle of each row in the periodic table.

The numbers Z and N are sufficient to describe atoms, but chemists find it convenient to use a third quantity, A, equal to the sum of Z and N. Because protons and neutrons differ in mass by only a factor of one part in 1836, we assign each the same arbitrary unit mass. The quantity A, therefore, represents the total mass of the nucleus. Because electrons are so light, A is very nearly the mass of the entire atom. From a practical perspective, it is easier to measure the total mass of an atom than to count its neutrons, so A is a more useful number than N. In shorthand form, we convey our knowledge about a particular atom (or nuclide, as it is called when the focus is on nuclear properties) by writing its chemical symbol, a familiar alternative for Z, preceded by a superscript that specifies A. For a nuclide consisting of 8 protons and 8 neutrons, for example, we write 16O. For the one with 26 protons and 30 neutrons, we write 56Fe.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

A beginning pianist often finds that the greatest obstacle to progress is musical notation. Dotted quarter notes, the bass clef, and all the strange comments in Italian are literally a foreign language that must be mastered by any musician. Beginning chemists often have a similar problem with the periodic table, their musical staff. For each element, there are atomic masses, oxidation states, ionic radii, and a host of other things to remember. The easiest, perhaps, is the element’s symbol, but even there a student chemist may be dazzled by strange conventions.

The classical elements, most of which are metals, were named so long ago that there is no record of where their names came from. The words iron, lead, gold, and tin, for example, are obscure Germanic names. They were good enough for common folk, but too plebian for alchemists, who preferred the more “scientific” sound of the Latin names ferrum, plumbum, aurium, and stannum. From these we get the symbols Fe, Pb, Au, and Sn. Many modern names have a Latin or Greek flavor as well, particularly those that were given as the periodic table went through a season of explosive growth during the early nineteenth century. Carl Mosander, for example, was so annoyed by the difficulty of isolating the element lanthanum that he gave it a name derived from the Greek verb lanthanein (“to escape notice”). French chemist Lecoq de Boisbaudran had a similar experience with dysprosium, for which he crafted a name from the Greek word dysprositos (“hard to get at”).

A geochemist may find it amusing to track down elements named for mining districts. In its first appearance, for example, copper was called aes Cyprium—literally, “metal from Cyprus.” Magnesium was named for the Magnesia district in Thessaly. The grand prize, however, has to go to a black mineral collected from a granite pegmatite near Stockholm in 1794 by the Finnish mineralogist Johan Gadolin. He named it yttria, after the nearby village of Ytterby. In 1843, Mosander isolated three new elements from yttria, calling them yttrium, erbium, and terbium. Almost forty years later, Swiss chemist Jean Charles de Marignac isolated yet another element, ytterbium, from the same ore. To complete the package, Marignac isolated one more element in 1880 and named it gadolinium for the original discoverer of the mineral (which is now known as gadolinite). Quite a yield from one little mining district!

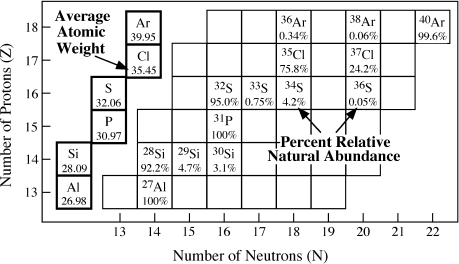

The existence of isotopes was not suspected during the nineteenth century, but it accounts for some of the confusion among chemists who were trying to make sense of periodic properties. Chlorine, for example, has two common isotopes: 35Cl and 37Cl. Because 35Cl is roughly three times as abundant as 37Cl, the weighted average mass of the two in a natural chlorine sample is close to 35.5. A natural sample of any element, in fact, will yield a nonintegral atomic mass for this reason. (Atomic mass is measured in atomic mass units [amu], equal to 1/12 of the mass of a 12C atom, or 1.6605 × 10−24 g.)

A geochemist analyzes a very large number of minerals containing lead and finds four isotopes in the following relative abundances:

204Pb (mass = 203.973 amu) 1.4%

206Pb (mass = 205.974 amu) 24.1%

207Pb (mass = 206.976 amu) 22.1%

208Pb (mass = 207.977 amu) 52.4%

Except for 12C, the masses of nuclides are never integral. Notice, for example, that the mass of 204Pb is slightly less than 204 amu. This is because a small fraction of the mass of any atom is actually in the binding energy that holds its nucleus together. (Recall Albert Einstein’s famous equation, e = mc2.) Given the nuclide masses in parentheses, then, what is the atomic mass of lead in nature, as implied by these analyses?

To calculate, multiply the mass of each nuclide by its proportion in the sample and sum the results:

203.973 × 0.014 + 205.974 × 0.241 + 206.976 × 0.221 + 207.977 × 0.524 = 207.217 amu.

FIG. 2.3. The stable nuclides, shown in black, define a narrow band within a wider band of unstable nuclides in this plot of protons (Z) versus neutrons (N). In general, elements with Z or N even have more stable nuclides than those with Z or N odd.

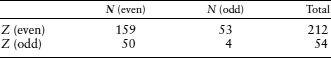

Roughly 1700 nuclides are known. Of these, only ∼260 are stable. The rest have nuclei that can disintegrate spontaneously to produce subatomic particles and leave a nuclide in which Z or N has changed. Figure 2.3, a plot of the number of neutrons versus protons in each of the known nuclides, illustrates this point. Stable nuclides only occur within a thin diagonal band, in which N is slightly greater than Z, flanked on both sides by unstable radioactive nuclides. Careful inspection of a segment of this band (fig. 2.4) shows that, in most cases, the stable nuclides have an even number of neutrons and protons. Stable nuclides with either Z or N as odd numbers are much less common, and isotopes with both Z and N odd are generally unstable. This distribution is shown numerically in table 2.1.

Most of the known radioactive isotopes do not occur in nature, although all have been produced artificially in nuclear reactors. Some of the “missing” isotopes may have occurred naturally in the distant past, but have such high decay rates that they have long since become extinct. The radioactive isotopes of greatest interest to geochemists generally decay very slowly or are replenished continually by natural nuclear reactions.

TABLE 2.1. Abundance of Stable Nuclides

Geochemists study both stable and radioactive isotopes in the Earth. In chapter 13, we look carefully at ways in which stable isotopes are fractionated in nature and how we can measure their relative abundances to figure out which processes may have affected geologic samples. Stable isotopes can also be used as tracers to infer chemical pathways in the Earth or to follow the progress of reactions. Radioactive isotopes, the topic of chapter 14, can also be used as tracers. Their primary value, however, is in dating geologic samples. Radiometric dating methods, suggested by Ernest Rutherford in the nineteenth century and put in useful form by Bertram Boltwood and Arthur Holmes early in the twentieth, are now the basis for all “absolute” ages in geology.

FIG. 2.4. Expanded segment of the nuclide chart of figure 2.3, showing stable nuclides and their percentages of relative natural abundances. The average atomic weight for each element (shown in the boxes to the left of the figure) is the sum of the weights of the various isotopes times their respective relative abundances.

The Basis for Chemical Bonds: The Electron Cloud

An atom is electrically independent of its neighbors if the number of electrons around it is the same as the number of protons in its nucleus. If not, then an excess positive charge on one atom must be balanced by negative charges elsewhere. This is the fundamental basis for bonding, the force that holds atoms together to form compounds.

Why should an atom ever have “too many” or “too few” electrons? Even as chemists at the start of the twentieth century gained confidence in the predictive capacity of the periodic table, stoichiometry (the rules governing how many atoms of each element belong in a compound) remained a stubborn mystery. It was easy to see, for example, that the composition of hydrides (and other simple compounds) follows a simple pattern across each row of the periodic table. Lithium combines with one hydrogen atom to form LiH, beryllium forms BeH2, boron makes BH3, and carbon CH4. From there to the end of the row, the combining ratio drops: NH3, H2O, and HF. There is no neon hydride. In the next row, we see NaH, MgH2, AlH3, SiH4, PH3, H2S, and HCl. There is no argon hydride. As the transition elements are added in successive rows, the pattern becomes less obvious, but is still there. Why? In fact, why are any of the periodic properties periodic?

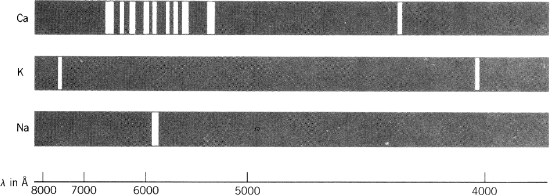

The answer lies in the distribution of electrons around the nucleus. Chemists began to glimpse the structure of the “cloud” of orbiting electrons in 1913, when Niels Bohr first successfully attempted to explain why atomic spectra consist of discrete lines instead of a continuous blur (fig. 2.5). Building on theoretical advances by Max Planck and Albert Einstein in the previous decade, he made the novel assumption that the angular momentum of an orbiting electron can only have certain fixed values. The orbital energy associated with any electron, similarly, cannot vary continuously but takes only discrete quantum values. As a result, only specific orbits are possible. In mathematical terms, Bohr postulated that the angular momentum of the electron (mevr) must be equal to nh/2π, where me is the mass of the electron, v is its linear velocity, r is its distance from the nucleus, h is Planck’s constant, and n takes positive integral values from 1 to infinity. Because n can only increase in integral steps, r defines a set of spherical shells at fixed radial distances from the nucleus.

Clever though this approach was, chemical physicists soon recognized that an electron cannot be described correctly as if it were a tiny planet orbiting a nuclear star. A better model uses the language of wave equations developed to describe electromagnetic energy. In 1926, Erwin Schrödinger proposed such a model incorporating not only the single quantum number as Bohr had suggested, but three others as well. Schrödinger’s equations describe geometrical charge distributions (atomic orbitals) that are unique for each combination of quantum numbers. The electrical charge that corresponds to each electron is not ascribed to an orbiting particle, as in Bohr’s model. Instead, you can think of each electron as being spread over the entire orbital—a complex three-dimensional figure.

The principal quantum number, n, taking integral values from 1 to infinity, describes the effective volume of an orbital—commonly calculated as the volume in which there is a 95% chance of finding the electron at any instant. This is similar to Bohr’s definition of n. Chemists commonly use the word shell to refer to all orbitals with the same value of n, because each increasing value of n defines a layer of electron density that is farther from the nucleus than the last n.

FIG. 2.5. Emission spectra for calcium, potassium, and sodium.

FIG. 2.6. The three p orbitals in any shell have figure-eight shapes, oriented along Cartesian x, y, or z axes centered on the atomic nucleus.

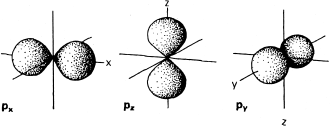

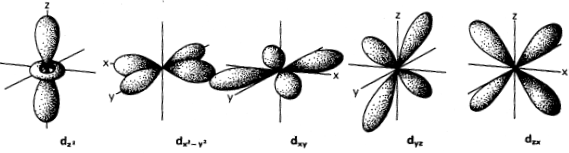

The orbital angular momentum quantum number, l, determines the shape of the region occupied by an electron. Depending on the value of n, a particular electron can have values of l that range from zero to n − 1. If l = 0, the orbital described by Schrödinger’s equations is spherical and is given the shorthand symbol s. If l = 1, the orbital looks like one of those in figure 2.6 and is called a p orbital. Orbitals with l = 2 (d orbitals) are shown in figure 2.7. The l = 3 orbitals (f orbitals) have shapes that are too complicated to illustrate easily here.

The third quantum number, ml, describes the orientation of the electron orbital relative to an arbitrary direction. Because an external magnetic field (such as might be induced by a neighboring atom) provides a convenient reference direction, ml is usually called the magnetic orbital quantum number. It can take any integral value from −l to l.

The fourth quantum number, ms, does not describe an orbital itself, but imagines the electron as a particle within the orbital spinning around its own polar axis, much like the Earth does. In doing so, it becomes a tiny magnet with a north and a south pole. The magnetic spin quantum number, ms, can be either positive or negative, depending on whether the electron’s magnetic north pole points up or down relative to an outside magnetic reference.

FIG. 2.7. Three of the d orbitals (dxy, dyz, and dzx) in any shell have four lobes, oriented between the Cartesian axes. A fourth (dx2−y2) also has four lobes, but along the x and y axes. The fifth (dz2) has lobes parallel to the z axis and a ring of charge density in the x-y plane.

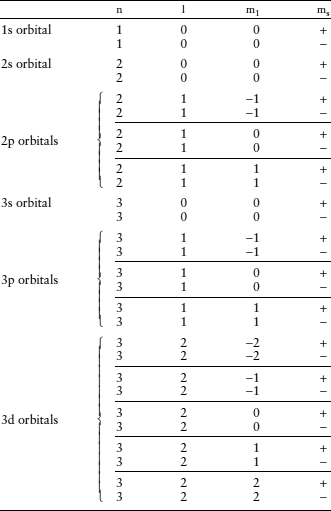

Each orbital therefore can contain no more than two electrons, with opposite spin quantum numbers. This rule, which affects the order in which electrons may fill orbitals, is known as the Pauli exclusion principle. The simplest atom, hydrogen, has one electron in the orbital closest to the nucleus (n = 1). With each increase in atomic number, atoms gain an electron in the unfilled orbital with the lowest energy level. We code electron orbitals with a label composed of the numerical value of n and a letter corresponding to the value of l, so the lowest orbital is called the 1s orbital. It can hold up to two electrons, as shown in table 2.2. The atom with atomic number 3, lithium, has two electrons in the 1s orbital and a third in 2s, which has the next lowest energy level. It takes another 7 electrons to fill the n = 2 shell with s and p electrons, and 18 more to fill the n = 3 shell with s, p, and d electrons.

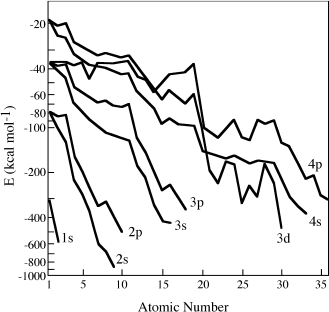

You can extend the table to calculate the number of s, p, d, and f orbitals in the n = 4 shell. The order in which orbitals beyond 3p fill, however, is not what you might expect from this exercise. As illustrated in figure 2.8, complex interactions among electrons and the nucleus reduce the energy associated with each orbital as atomic number increases. In neutral potassium and calcium atoms, the first to have >18 electrons, the 4s orbitals have lower energy levels than the 3d orbitals, so the nineteenth and twentieth electrons fill them instead. With increasing atomic number, electrons fill the 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, and 5p orbitals. This order could only be anticipated by calculating the relative energy levels of successive orbitals, as was done in producing figure 2.8. Once recognized, however, the order provides insight into the layout of the periodic table. If you compare table 2.2 with the periodic table, you will see an interesting pattern. Each row in the periodic table begins with a new s orbital (n increases by 1 and l = 0), and ends as the last p orbital for that value of n is filled. The s and p orbitals, in other words, define the basic outline of the periodic table. Atoms whose last-filled orbitals are d or f orbitals make up the transition elements that occupy the central block in rows 4 and beyond.

TABLE 2.2. Configuration of Electrons in Orbitals

Why should a geochemist care about this level of detail? One reason is that electronic configuration offers a way to interpret bonding and, with it, the driving force for chemical reactions. Site occupancies in minerals and mineral structures themselves are best understood when we predict the shapes and orientations of electron orbitals. We explore this general topic later in this chapter. Another reason is that an atom’s electronic configuration determines its affinity for atoms of other elements. By studying the periodic properties of the elements, we can begin to understand how they are distributed in the Earth.

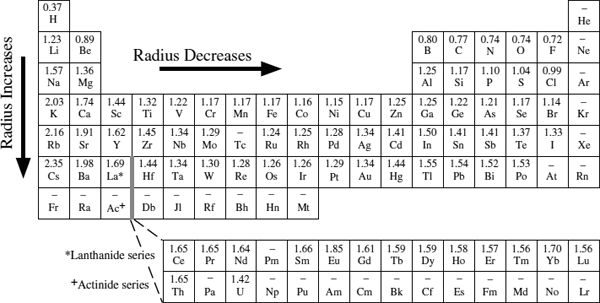

The outermost electrons in an atom determine its effective size, or atomic radius, as well as much of its behavior in bonding. These electrons are sometimes called the valence electrons. Figure 2.9 illustrates two trends with increasing atomic number. First, as s and p electrons are added across a single row of the periodic table, atomic radius decreases. The simple explanation for this is that the positive charge of the nucleus continues to increase as atomic number increases. Electrons in the same shell cannot effectively shield each other from the pull of the nucleus, so valence electrons are drawn in as nuclear charge increases, shrinking atoms from left to right across a row. (Shielding effects among electrons in d and f orbitals are more complex, so this trend is less consistent across the transition elements.) Increasing atomic number beyond the end of a row, however, means adding electrons to a new shell, farther from the nucleus. As a result, elements in the next row in the periodic table have larger atomic radii. Within a single column of the periodic table, therefore, atomic radius increases with increasing atomic number. This second trend is also apparent in figure 2.9.

FIG. 2.8. As atomic number increases, electrons are increasingly shielded from the charge of the nucleus by the presence of other electrons. As a result, the energy (E) necessary to stabilize an electron in each orbital generally decreases with increasing atomic number. This rule is made more complex by interactions between the orbitals themselves. Energy levels in the 3d orbitals, for example, increase across much of row 3 in the periodic table. Potassium and calcium, which in their ground state have enough electrons to enter 3d orbitals, instead place them in 4s orbitals, which have a lower energy.

FIG. 2.9. Atomic radii, indicated here in Ångströms (Å), decrease across each row in the periodic table as nuclear charge increases. Each added shell of electrons, however, is shielded from the nucleus by inner electrons. Atomic radii therefore increase from one row to the next. Chemists generally determine the size of atoms by studying the dimensions of their coordination sites in crystal structures (discussed later in this chapter). It is difficult to measure atomic radii for elements that are rare in nature (the actinides, for example) or that do not bond with other elements to form crystals (the noble elements). For this reason, no radii are reported for those elements in this figure.

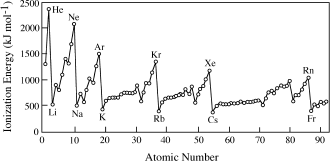

The measure of the energy needed to form a positively charged ion (a cation) by removing electrons from an atom is called ionization potential (IP), plotted in figure 2.10. When electrons are closest to the nucleus, they are hardest to remove with energy supplied from the outside. For this reason, it is easier to produce cations of atoms toward the bottom or the left side of the periodic table than from atoms toward the top or the rightmost columns.

IP is greatest in the right hand column of the periodic table, among the group of elements known as the noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, and Rn). In this group, all appropriate s and p orbitals are filled. This configuration, known as a complete outer shell, is particularly stable. Atoms on the left side of the periodic table form cations readily, losing enough electrons that their outer shell looks like the noble gas at the end of the previous row. In the second row, for example, lithium easily loses one electron to become Li+, beryllium becomes Be2+, and boron becomes B3+, in each case ending up with an outer shell that looks like that of neutral helium.

FIG. 2.10. The energy required to remove one electron from an atom increases across each row of the periodic table, but decreases slightly from one row to the next because successive shells of electrons are held less tightly by the positive charge of the nucleus. The quantity plotted here is the first ionization potential. A plot of the second or third ionization potential would be similar to this one, although removal of a second or third electron requires more energy.

The converse of ionization potential is electron affinity (EA), the amount of energy released if we succeed in adding a valence electron to a neutral atom to create a negatively charged anion. Like IP, EA also increases to the right in the periodic table. The highest affinities are among the halogens (F, Cl, Br, and I), which only need to gain a single electron to reach a noble gas configuration. These and the four elements to their immediate left (O, S, Se, and Te) are the only ones that commonly form anions. For all other elements, EA is very small or negative, indicating that they gain little or no stability by gaining electrons.

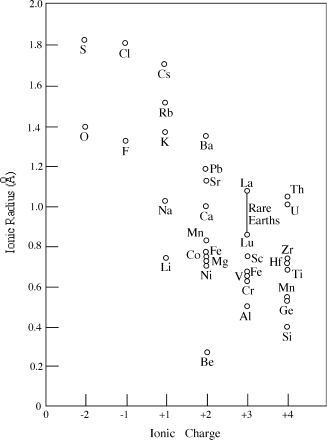

Ionization changes the size of an atom. If it loses electrons, the net positive excess charge in its nucleus draws the remaining electrons in tighter. The overall trend in cation radii, therefore, is the same as for atomic radii: they increase toward the bottom and decrease toward the right side of the periodic table. Gaining electrons has the opposite effect, so anions are larger than their neutral counterparts. Figure 2.11 illustrates how ionic radii vary with atomic number.

Trends among the periodic properties suggest logical ways to group elements. For example, it is customary to speak of all elements in the leftmost column of the periodic table as alkali metals and those in the second column as alkaline earth metals. The rightmost column we have already identified as the noble gases; the column to its left contains the halogens. In each of these groups, elements have the same configuration of valence electrons. The alkali metals (Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs, and Fr), for example, each have a lone electron in the outermost shell and therefore readily form cations with a +1 charge. Chemists also speak of the transition metals, a group of elements in the middle of rows 4, 5, and 6, across which the d electron orbitals are gradually filled. Similarly, the lanthanides and actinides in rows 6 and 7 are groups across which the f orbitals are filled. Each of these groups, labeled in figure 2.12, contains elements that, by virtue of their common electron configuration, behave in similar ways during chemical reactions and therefore form similar compounds.

FIG. 2.11. As electrons are removed from an atom, the remaining electrons are drawn more tightly by the charge of the nucleus, so that ionic radius decreases with increasing positive charge. Compare, for example, the radii of Fe2+ and Fe3+ or Mn2+ and Mn4+. Also, compare each of the ionic radii in this figure with the atomic radii in figure 2.9.

Appreciation for the periodic properties of the elements has cast light on many geochemical mysteries. One of the most fundamental observations that geologists make about the Earth, for example, is that it is a differentiated body with a core, mantle, and crust that are chemically distinct. Why? Is there a rational way to explain why such elements as potassium, calcium, and strontium are concentrated in the crust and not in the core? Or why copper is almost invariably found in sulfide ores rather than in oxides?

FIG. 2.12. Elements with similar properties fill similar roles in nature and are therefore commonly recognized as members of groups, as indicated in this figure. The lanthanides are often referred to as rare earth elements (REE).

Early in the twentieth century, Victor Goldschmidt was prompted by a study of differentiated meteorites to propose a practical scheme for grouping elements according to their mode of occurrence in nature. His analyses of three kinds of materials—silicates, sulfides, and metals—suggested that most elements have a greater affinity for one of these three materials than for the other two. Calcium, for example, can be isolated as a pure metal with great difficulty, and its rare sulfide, oldhamite (CaS), occurs in some meteorites. Calcium is most common, however, in silicate minerals. Gold, however, is almost invariably found as a native metal.

Goldschmidt’s classification, summarized below, ultimately included a fourth type of material not found in abundance in meteorites:

FIG. 2.13. Goldschmidt’s classification of the elements emphasizes their affinities with three fundamental types of Earth materials (sulfides, silicates, or native metals) or with the atmosphere. Several elements—the most abundant being iron—have affinities with more than one group.

As figure 2.13 suggests, these four categories overlap quite a bit. Tin, for example, is commonly found as an oxide (the mineral cassiterite, SnO2) and less often as a sulfide (stannite, Cu2FeSnS4). Carbon, as graphite or diamond, occurs as a pure element and it alloys readily with other metals, as in the manufacture of steel, but it is also common as a lithophile element in carbonates. Iron forms abundant silicate and sulfide minerals, but it is also the major constituent of the Earth’s metallic core. Nevertheless, most elements belong primarily in one group, and Goldschmidt’s classification is a guide to geochemical behavior.

Why does this geochemical classification work? Again, it is based loosely on the periodic properties of elements and, in particular, on those properties that control bonding between elements. We pursue this topic in the final sections of this chapter.

A bond exists between atoms or groups of atoms when the forces between them are sufficient to create an atomic association that is stable enough for a chemist to consider it an independent entity. This definition gives us a lot of room for subjective judgment about what “stable enough” and “independent” mean, and it covers a range of situations in which the types and strength of forces differ. In general, chemists find this flexibility to be an advantage. Students of geochemistry, however, can be led into uncertainty about the role of individual atoms in natural materials. In crystalline solids, for example, the “independent entity” is not a freestanding molecule but an extended periodic array of atoms in which bonds may range subtly both in strength and in character. One source of confusion is the apparently sharp distinction between ionic and covalent bonds that many students learn in basic chemistry courses. Briefly and in the simplest terms, you may have learned that an ionic bond is one in which one or more electrons is transferred from a cation to an anion; a covalent bond is one in which electrons are shared between adjacent atoms. In both cases, the goal is for each atom to end up with a noble gas configuration in its outer shell of electrons. In fact, the difference between ionic and covalent bonding is more a matter of degree than a clear distinction.

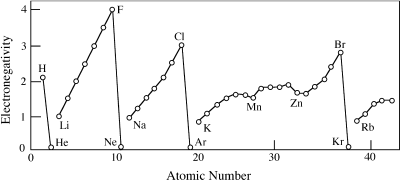

A common way to determine whether a bond is ionic or covalent is based on electronegativity (EN). EN is proportional to the sum of IP and EA. Because affinity is difficult to measure, however, EN is usually calculated directly from bond energies. Figure 2.14 summarizes EN values for many elements.

The greater the EN difference between atoms, the more likely it is that electrons will be transferred from one atom to the other, forming an ionic bond. Typically, a bond is considered ionic if the EN difference in it is >2.1. For example, when a chlorine atom (EN = 3.16) is adjacent to a sodium atom (EN = 0.93), it easily draws the lone electron from sodium to itself. This is apparent in the electronegativity difference (ΔEN) of 2.23 between the atoms. The Mg-O and Ca-O bonds that are common in rock-forming silicates are also ionic ΔEN = 2.13 and 2.44, respectively). Si-O and Al-O bonds in the same minerals have ΔEN = 1.54 and 1.83, however, and are therefore covalent, by this definition.

Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling suggested an alternative way to describe a bond by calculating its percentage of ionic character with the empirical formula:

p = 16|ENa − ENb| + 3.5|ENa − ENb|2,

in which a and b are atomic species to be bonded. For Na-Cl, we find that p = 54.7% and for Ca-O, p = 59.9%, whereas for Si-O, p = 32.9% and for Al-O, p = 41.0%. If we look at bonding in this way, we see “ionic” and “covalent” as relative terms on a continuum of bond types. This offers a more realistic perspective on variations in bonding, but can present conceptual difficulties when we consider mineral structures. It is customary, for example, for geochemists to talk about the “ionic radius” of Mg2+, as we have earlier in this chapter. If an Mg-O bond is described in Pauling’s terms, however, p = 49.9%. Roughly half of the electron charge transferred from the Mg2+ ion, therefore, is actually shared with the O2- ion, so it is difficult to conceive of either ion as an independent entity with a clearly defined radius. The standard practice of referring to “ions” in mineral structures as if they were the same as free ions in aqueous solution is clearly misleading.

The percentage that Pauling’s formula estimates can be thought of in another way: as the polarity of the bond. Geochemists who deal with gases or aqueous solutions find that a knowledge of polarity helps to explain solubility, reactivity, and other key properties. Those who deal with solid materials can use the same sort of information to interpret optical, thermal, and electric properties. Polarity can greatly affect the boiling point and conductivity of a substance, for example, and the way it combines with other substances, as in H2O (see the box on this topic, later in the chapter).

FIG. 2.14. Electronegativity generally increases with atomic number, within a single row of the periodic table. It may be thought of as a measure of the ease with which an atom can add electrons to complete its outer shell.

Structural Implications of Bonding

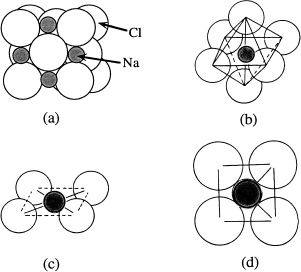

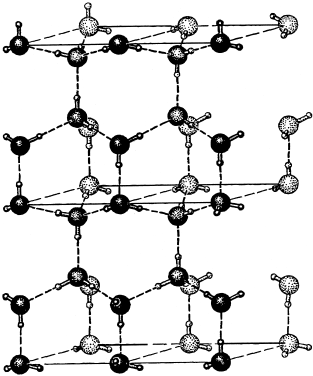

If bonds in a substance have a highly ionic character, it is convenient to view the atoms like marbles arranged according to size and electrical charge. Each ion must be surrounded by oppositely charged ions, so that electrical charge is balanced locally, but the number of surrounding ions depends on their relative sizes. This is the case because ionic bonding leads to the most stable structure when the ions are packed together as closely as possible. In the halite (NaCl) structure, for example, each sodium atom is at the center of a cluster of six chloride ions and each chloride ion is surrounded by six sodium ions. The positive charge on each sodium ion is distributed evenly over six Na-Cl bonds, and so is the negative charge on each chloride ion. But why six ions?

Figure 2.15a shows a perspective drawing of the halite structure, with cations and anions drawn as spheres. The distance between ions, which touch each other in the actual structure, has been exaggerated for ease of viewing. Figure 2.15b isolates a portion of the structure: a cation at the geometric center of an octahedral array of anions. In figure 2.15c, we have removed the top and bottom anions for clarity, and in figure 2.15d, we have rotated that view to be viewed directly from above. In this final perspective, we have restored interatomic distances to show the cation-anion contact.

If we were to decrease the ionic radius ratio r+/r− somehow, it should be apparent that the distance d between the anions would gradually shrink to zero, at which point they would be touching. At that point, the length of each side of the square connecting their centers would be 2r+. By the Pythagorean Theorem, it would also be equal to  (r+ + r−). Algebraic manipulation of the two expressions reveals that the value of r+/r− would have become

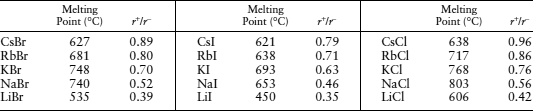

(r+ + r−). Algebraic manipulation of the two expressions reveals that the value of r+/r− would have become  − 1 = 0.414. We could not decrease r+/r− further without either allowing the anions to overlap or creating free space between the anions and the cation, so that they no longer touched. The first of these conditions is self-limiting, because the valence electrons of the anions repel each other, preventing further overlap. The second condition is far more likely. In fact, it is not uncommon for a small cation to rattle around in an oversized site surrounded by anions that touch each other. In such cases, however, the cation-anion bonds are longer and thus weaker than they are when the anions are farther apart. This can be seen, for example, in the abnormally low melting points of lithium halides (table 2.3).

− 1 = 0.414. We could not decrease r+/r− further without either allowing the anions to overlap or creating free space between the anions and the cation, so that they no longer touched. The first of these conditions is self-limiting, because the valence electrons of the anions repel each other, preventing further overlap. The second condition is far more likely. In fact, it is not uncommon for a small cation to rattle around in an oversized site surrounded by anions that touch each other. In such cases, however, the cation-anion bonds are longer and thus weaker than they are when the anions are farther apart. This can be seen, for example, in the abnormally low melting points of lithium halides (table 2.3).

FIG. 2.15. (a) The structure of sodium chloride—the mineral halite—is based on a cubic face-centered lattice. Na+ and Cl− ions alternate along all three coordinate axes. As a result, each ion is surrounded by six ions of the other element. (b) A single Na+ ion and the six Cl− ions surrounding it, “exploded” to illustrate the octahedral arrangement of anions. (c) The top and bottom Cl− ions have been removed for clarity, revealing a square planar array of Cl− ions around the Na+. (d) A view straight down on the planar arrangement.

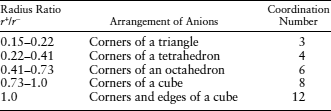

For ionic compounds with r+/r− < 0.414, fourfold (tetrahedral) coordination is more likely than the sixfold (octahedral) coordination of the NaCl structure, because the cation no longer rattles around in an oversized site. We have to be cautious about applying geometric arguments for such compounds, however, because cations tend to form bonds with a more covalent character when they are in fourfold coordination. Unlike purely ionic bonds, which are electrostatic and therefore nondirectional, covalent bonds are directional. As we show shortly, this adds further complexity to the study of structure.

What if we increase r+/r−, though, instead of decreasing it? If the central cation becomes large enough, it is eventually possible to create a more stable site by surrounding it with eight, rather than six anions. In problem 2.9, at the end of this chapter, you are challenged to show that this arrangement is preferred when r+/r− >  − 1 = 0.732. As indicated in table 2.3, this is the case for each of the cesium halides.

− 1 = 0.732. As indicated in table 2.3, this is the case for each of the cesium halides.

TABLE 2.3. Melting Points of Some Alkali Halides

Ionic radii are from Shannon (1976).

Cesium ions are in eightfold, rather than sixfold, coordination in halide compounds.

We can anticipate the coordination number and geometric arrangement of anions around any ion in an ionic solid, then, by referring to the limiting ratios r+/r− shown in table 2.4. These coordination guidelines are only approximate, because ions are not like the rigid marbles we have assumed in this discussion. Instead, ions expand or shrink slightly to fit their environment. This makes it difficult to apply the guidelines when r+/r− is close to one of the limiting values, as is the case for RbBr and RbCl, which have the halite structure rather than the predicted cesium halide structure. Still, it is surprising how well simple radius ratios can help us anticipate a coordination number even for groups of ions with relatively little ionic character.

Another approach to understanding the geometric implications of bonding builds on valence-bond theory, an extension of the quantum model described earlier in this chapter. According to valence-bond theory, a chemical bond occurs when electron orbitals in adjacent atoms overlap, creating new valence electron orbitals that encompass both atoms. Only certain orbitals are allowed to overlap, however. The geometric arrangement of those orbitals determines how atoms cluster around each other.

TABLE 2.4. Coordination Relationships in Ionic Compounds

To explore briefly how this theory works, let’s look back at the quantum model for a single atom. Recall that for each combination of n, l, and ml, there are two possible values of ms, the magnetic spin quantum number. Two electrons with the same n, l, and ml, but opposite values of ms are said to be paired. Each shell, for example, can hold up to six electrons in the orbitals labeled px, py, and pz in figure 2.6. Because the second electron in an orbital occupies a slightly higher energy level than the first, electrons find an advantage to being distributed evenly among the three orbitals. If an atom doesn’t have enough electrons to fill all three orbitals completely, then it accepts only one electron each in px, py, and pz before adding a second electron to any of them. Why is all of this important? Because the electrons in the unpaired orbitals are the ones that can overlap between atoms to form bonds with a covalent character.

A neutral oxygen atom, for example, has eight electrons. Two of them fill the s orbital in the first shell, another two enter the s orbital in the second shell, and the other four are in second shell p orbitals. Two are paired in 2px, one is in 2py, and one in 2pz. Oxygen is therefore divalent; covalent bonds can form at right angles, along the partially occupied py and pz orbitals. Nitrogen, which has one fewer electron than oxygen, is trivalent; its 2p electrons are unpaired—one each in px, py, and pz. In a molecule such as NH3, mutually perpendicular covalent bonds form along each orbital lobe.

Valence-bond theory predicts molecular structures, then, by examining the number and arrangement of unpaired electrons in each atom. It also takes into account the energy level of each orbital and their orientations as they overlap. The union of new valence orbitals constitutes a new entity, a bonding orbital, that has a lower energy and is therefore more favored than the valence orbitals considered independently. In a molecule of H2, for example, each atom contributes an unpaired 1s electron, and their orbitals overlap to form s-s bonding orbitals. The H2 molecule is stable because the pair of bonding orbitals has a lower potential energy than the combination of two partially occupied valence orbitals. This will be a useful perspective to recall in chapter 3, where we introduce the concept of Gibbs free energy and explore the driving force for chemical reactions.

There are many ways to form bonding orbitals, and a discussion of them is beyond the scope of this chapter. The following example emphasizes the usefulness of valence-bond theory in geochemistry—perhaps enough to encourage you to make a more rigorous study of the topic.

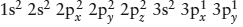

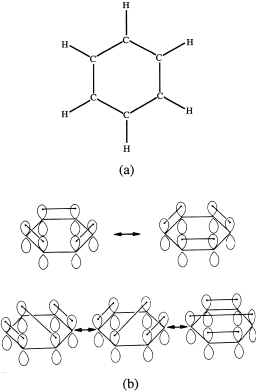

Silicon, a key element in rock-forming minerals, poses an interesting conceptual challenge in valence-bond theory. It has only two electrons in partially filled orbitals—silicon’s configuration is  —so, by analogy with what we have just illustrated about oxygen and nitrogen, silicon should be divalent. In fact, however, it has a formal valence of +4, as if the atom had two more unpaired electrons. Why?

—so, by analogy with what we have just illustrated about oxygen and nitrogen, silicon should be divalent. In fact, however, it has a formal valence of +4, as if the atom had two more unpaired electrons. Why?

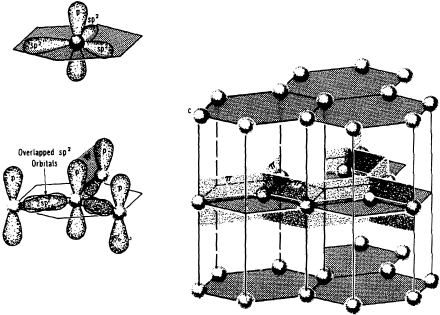

The solution to this paradox lies in the formation of hybrid valence orbitals (fig. 2.16). In compounds of silicon, an electron is “promoted” from an s orbital to a vacant p orbital, giving the outer shell the potential structure  . It takes energy to redistribute electrons in this way, however, and this energy is obtained in part by making each of the four unpaired electrons equivalent to the others. The new entities are sp3 hybrid orbitals, oriented toward the four corners of a regular tetrahedron. As these form bonding orbitals to oxygen atoms, they become the basis for the SiO4 tetrahedral unit that is common to all silicate minerals.

. It takes energy to redistribute electrons in this way, however, and this energy is obtained in part by making each of the four unpaired electrons equivalent to the others. The new entities are sp3 hybrid orbitals, oriented toward the four corners of a regular tetrahedron. As these form bonding orbitals to oxygen atoms, they become the basis for the SiO4 tetrahedral unit that is common to all silicate minerals.

We might have tried to predict this tetrahedral arrangement of bonds by comparing ionic radii. The ionic radius of Si4+ is 0.26 Å; the radius of O2− is 1.35 Å. A quick check of table 2.3 indicates that their ratio (= 0.19) is only slightly smaller than expected for fourfold coordination. Although this result is reassuring, it is somewhat misleading. Using r+/r− ignores the fact that the Si-O bond is highly covalent and that the Si4+ ion, therefore, cannot be considered as spherically symmetrical. Valence-bond theory is a more appropriate tool in this case.

FIG. 2.16. Bonding electrons in a silicon atom are in 3px and 3py orbitals. There are no electrons in 3pz. The paired electrons in 3s are not available for bonding. If the s and p orbitals are combined, then each of the four electrons becomes a bonding electron in a hybrid sp3 orbital. Each hybrid orbital has two lobes, one of which is larger than the other. The four large lobes point toward the corners of a tetrahedron.

So far, we have emphasized interactions between pairs of atoms. In extended structures, such as crystals and most organic molecules, however, each atom is affected not only by its nearest neighbors but also by those farther away. Because electrons are generally bound closely to their parent atoms, these distant forces are minimal. In some materials, though, extended molecular orbitals may include several atoms. For example, the benzene (C6H6) molecule (fig. 2.19a) is described classically as a ring of carbon atoms held together by covalent single and double bonds. As the structural diagrams in figure 2.19b indicate, there are five different ways to arrange the six bonds in the ring. Valence-bond theory suggests that each of them is equally probable and that the true structure of benzene, therefore, is a resonant mixture of all five. Some of the bonding electrons, in other words, do not belong to specific pairs of carbon atoms but to the entire ring.

WATER IS A STRANGE SUBSTANCE

It is virtually impossible to find a geochemical environment in which water does not play a role, whether at low or high temperature, on the Earth’s surface, or deep in the crust. Although water is a familiar substance, it has unusual properties that can only be understood by studying hybrid bonding orbitals.

A neutral oxygen atom contains unpaired electrons in 2py and 2pz orbitals. When these bond to hydrogen atoms, the result should be a pair of H-O bonds at right angles. Instead, interelectronic repulsion between the filled 2s2 and  orbitals favors the formation of sp3 hybrid orbitals such as those discussed in worked problem 2.2. The oxygen atom in a water molecule therefore finds itself at the center of a tetrahedral arrangement of hybrid orbitals. Two of these contain lone pairs of electrons; the other two bond to hydrogen atoms.

orbitals favors the formation of sp3 hybrid orbitals such as those discussed in worked problem 2.2. The oxygen atom in a water molecule therefore finds itself at the center of a tetrahedral arrangement of hybrid orbitals. Two of these contain lone pairs of electrons; the other two bond to hydrogen atoms.

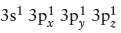

FIG. 2.17. Visualize a hydrated Na+ or Cl− ion at the center of a cube with water molecules at four of the corners. The negative end of each water dipole is attracted to the Na+ ion, so the hydrogen ions at the positive end point outward. A Cl− ion attracts the positive end of the water dipole, so that the hydrogen ions point inward.

A water molecule, therefore, is asymmetrical. The center of positive charge is offset quite a bit from the center of negative charge. Because H-O bonds lie on one side of the oxygen atom, the water molecule has a strong dipole moment and can exert an orientation effect on nearby charged particles. As a result, water is an excellent solvent for ionic substances. In a sodium chloride solution, for example, each Na+ ion is surrounded by a hydration tetrahedron of water molecules, each one with its negative end drawn toward the Na+ ion by a weak ion-dipole interaction (fig. 2.17). Each Cl− ion attracts the positive end of a water dipole and is also enclosed in a hydration sphere. Sodium and chloride ions are thus shielded from each other and prevented from precipitating. We investigate solubility more fully in chapters 4 and 7.

Water molecules also attract each other through dipole-dipole interactions that we refer to as hydrogen bonds. The attraction is greatest in ice, in which each hydrogen atom is drawn electrostatically to a lone electron pair on a neighboring water molecule (fig. 2.18). The result is an open network of molecules that has a dramatically lower density than liquid water. This attraction also accounts for water’s unusually high surface tension, boiling point, and melting point, as well as many other distinctive properties we will explore elsewhere in this book.

FIG. 2.18. When water freezes, sp3 orbitals on adjacent H2O units align so that there is one hydrogen atom along each oxygen-oxygen axis. The hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) between H2O units thus make an electrostatic connection between hydrogen ions on one H2O molecule and paired (nonbonding) electrons on the other molecule. These weak bonds are nevertheless strong enough to support the open crystal structure of ice.

Taken to an extreme, this multiatom example suggests a parallel to the popular description of bonding in metals. We observed earlier that the distinction between ionic and covalent bonding is not sharp, but a matter of degree. Metallic bonding is yet another mode along a continuum of atomic interactions, a mode in which electrons are even more free to roam from their parent atoms than in covalently bonded materials. In a pure metal, all atoms are the same size, so the coordination number for any one of them is 12 (see table 2.4). Statistically, therefore, each atom should have 12 equivalent bonds with its neighbors. None of the metals, however, has 12 unpaired electrons or can generate that many hybrid orbitals. This apparent problem can be resolved if we consider the bonding orbitals to be an extensive, nondirected resonant network, often described as an electron “gas” that permeates the structure. As in the benzene molecule, valence electrons belong to the entire structure, not to specific atoms. As a result, metals have a higher electrical and thermal conductivity than nonmetals.

FIG. 2.19. (a) Bonding electrons in a benzene molecule bind six carbon atoms in a ring and connect a hydrogen ion to each one. The remaining bonding electron from each carbon atom occupies a p orbital perpendicular to the plane of the ring. (b) At any instant, electrons in the projecting p orbitals (technically, π orbitals) can form stable pairs (hence a “second” or “double” bond) in any of five ways. The benzene structure is a resonant mixture of these equally probable arrangements.

This simplistic “free electron” model for metallic bonding is limited in ways that would become apparent if we studied the electrical potential across a metallic structure carefully. The quantum nature of the structure makes some energy levels accessible to the free electrons and prohibits others. Even at this basic level, however, the concept of nonlocalized bonding offers a useful starting point for understanding the behavior of metals.

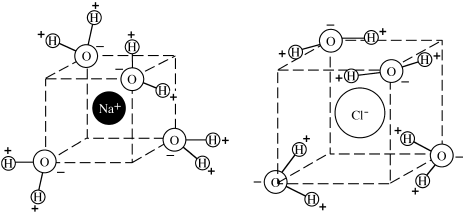

Yet another variation on this theme of nonlocalized bonding is Van der Waals bonding, which may also be described as an extended, nondirectional field of forces between atoms or molecular units. Geologists may know of Van der Waals bonding primarily through their familiarity with the structure of graphite, which consists of stacked sheets of covalently bonded carbon (fig. 2.20). Overlapping sp2 hybrid orbitals shape the hexagonal array of atoms within a sheet. Electrons in these orbitals are tightly bound to pairs of atoms. Electrons in the remaining unhybridized p orbital on each carbon atom stabilize the sheet by being shared more extensively within the array. Because all of these interatomic forces are confined within sheets, each sheet can be thought of as a separate “molecule” of graphite. The unhybridized p orbitals, however, are perpendicular to the sheets and thus contribute to local charge polarization, analogous to the polarity on a water molecule. This polarization provides the weak cohesion—the Van der Waals attraction—that binds sheets together in crystals of graphite.

FIG. 2.20. Carbon atoms within a sheet of the graphite structure are bonded by electrons in overlapping sp2 hybrid orbitals and by electrons shared among p orbitals perpendicular to the sheet, as in benzene (see fig. 2.19). The weak Van der Waals attraction between sheets is due to local charge polarization on those p orbitals.

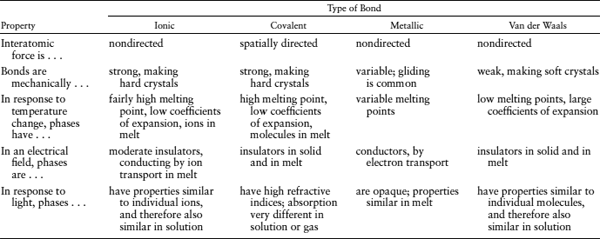

TABLE 2.5. Properties Associated with Interatomic Bonds

After Evans (1964).

Unlike other treatments of chemical bonding that you are likely to have seen, we have tried to call attention to similarities among bond types rather than differences. As so often is true in science, the simple categories you may have learned to recognize in early chemistry or mineralogy courses have blurred edges. Ionic, covalent, metallic, and Van der Waals bonds constitute a continuum of forces that hold atoms together. It is particularly important to emphasize this, because the structures of the most abundant geologic materials include bonds from more than one of the standard categories, as well as some that cannot be placed easily in any of them. As a result, many geologic materials do not behave the way you may have learned to expect ideal ionic, covalent, or metallic substances to behave.

We do not mean to imply that the distinctions among the bond types are meaningless. As table 2.5 indicates, there are some fundamental differences between compounds based primarily on each of these types of bonds. These differences are apparent across broad categories of Earth materials that we consider in later chapters.

In this chapter, we have established a vocabulary for the chemical language we use throughout this book, without straying too far from our peculiar interest in the chemistry of the Earth. With luck, much of what you have just read is a review of familiar material. We hope, though, that we have succeeded in presenting it from a novel perspective. The structure of atoms, particularly the configuration of their electrons, controls the ways that they combine to form natural materials. The type and strength of chemical bonds in a substance determine the amount of energy needed to involve it in reactions. The masses, sizes, and electrical charges on atoms influence the rates at which they react with each other. All of these are topics we explore in the chapters ahead.

Ahrens, L. H. 1965. Distribution of the Elements in our Planet. New York: McGraw-Hill. (This concise paperback, now dated, is still one of the best overviews of the principles affecting element distribution in the Earth.)

Barrett, J. 1970. Introduction to Atomic and Molecular Structure. New York: Wiley. (A rigorous introduction to the topic, without the heavy reliance on mathematics that can make quantum chemistry inaccessible for nonspecialists.)

Faure, G. 1991. Principles and Applications of Inorganic Geochemistry. New York: Macmillan. (A well-written, broad introduction to geochemistry, with particular attention to nuclear chemistry.)

McMurray, J. and R. C. Fay. 1995. Chemistry. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. (Every geochemistry student should have a basic comprehensive chemistry text; we consider this one to be the best.)

Pauling, L. 1960. The Nature of the Chemical Bond, 3rd ed. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (This is the classical treatise on bonding, surprisingly easy to follow.)

Van Melsen, A.G. 1960. From Atomos to Atom. New York: Harper and Brothers. (For students who are curious about the history of science, this book is a highly readable account of the evolution of atomic theory.)

The following sources were referenced in this chapter. The reader may wish to examine them for further details.

Evans, R. C. 1964. An Introduction to Crystal Chemistry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shannon, R. D. 1976. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallographica, Section A 32:751–767.

(2.1) Magnesium has three naturally occurring isotopes: 24Mg (78.99% abundance, mass = 23.985 amu), 25Mg (10% abundance, mass = 24.986 amu), and 26Mg (10% abundance, mass = 25.983amu). What is the average atomic weight of magnesium?

(2.2) The average atomic weight of silicon is 28.086 amu. It has three stable isotopes, two of which are 28Si (92.23% abundance, mass = 27.977 amu) and 30Si (3.10% abundance, mass = 29.974 amu). What is the mass of the third stable isotope?

(2.3) 14C, important in radiometric dating, has the same atomic mass number as 14N. How is this possible?

(2.4) Arrange the following bonds in order of their increasing ionic character, using Pauling’s formula: Be-O, C-O, N-O, O-O, Si-O, Se-O. Repeat, using DEN values. How do the two sets of results compare?

(2.5) What electrically neutral atoms have each of following the ground state configurations?

(a) 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2

(b) 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d6

(c) 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p5

(2.6) What is the ground state configuration for each of the following ions?

(a) Mg2+

(b) F−

(c) Cu+

(d) Mn3+

(e) S2−

(2.7) Predict the coordination number for each element in the following compounds or complexes:

(a) CuF2

(b) SO3

(c) CO2

(d) MnO2+

(2.8) Considering their EN values, explain why potassium, strontium, and aluminum are classified as lithophile rather than chalcophile elements in Goldschmidt’s classification.

(2.9) Show algebraically that eightfold coordination for a cation is likely only if the ionic radius ratio r+/r− >  − 1 = 0.732.

− 1 = 0.732.

(2.10) According to one empirical set of definitions, atoms joined by covalent bonds form molecules; those joined by ionic or metallic bonds do not. What might be the justification for these definitions? Are they valid? What are their limitations?

(2.11) Graphite will conduct an electrical current applied parallel to its sheet structure, but will not conduct a current perpendicular to the sheets. Why?