If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.

—Abraham Lincoln

SITA’S LAST WISH

SHE STOOD LOW to the ground, hunched, eyes averted. Emaciated by misery and disease, she was next of kin to oblivion. Sita1 was born to be a slave, at least for a portion of her life, and after that—an outcaste waiting to die. She is Bedia, a subjugated caste of former nomads in the state of Rajasthan, India. Unlike much of the nation, the Bedia prize their daughters, for they grow up to be prostitutes, and nothing else. It is the sole vocation they are allowed, by birth-curse, and it begins when they are children. They are told to be proud. They are told it is better than being a housewife. Bedia men only marry outside their community, and their wives have the lowest status of all. Sons born of these wives will one day peddle their sisters and hope to produce more Bedia daughters. The men live off the earnings of their child-raped girls. These children are the dismal face of slavery—an oppressed subclass of humanity fit only to be consumed, for profit.

I met Sita in a dusty village about forty kilometers outside the city of Bharatpur. Her mud-brick hut baked like an oven. Stray dogs with patches of missing fur skulked lazily between miserly pockets of shade. They growled, but meant no harm. Sita’s breathing was labored; she knew she was not long for this world. Before the end, she wanted to tell her story. She knelt to touch my feet, but I waved her up and said that I should be touching hers instead. I reached out my hand and asked her to take it. She looked at me nervously; no one like her is allowed to touch the skin of someone like me, unless of course it is because she has been purchased. She folded her hands in a gesture of respectful decline. I understood. We sat on the dirt inside her hut, and I told her I would listen, as long as she wanted. She took a sudden, desperate breath, the kind meant to quell a gathering storm of pain. Then, she spoke.2

My father died when I was nine. My mother took me and my brother to live with my uncle. I had my first period when I was thirteen. My uncle was happy. He sold my virginity to a businessman in Bharatpur for Rs 50,000 [~$960].3 He slaughtered a goat and we did a ceremony called nathni utarna [literally “taking off the nose ring”]. This means I am ready to be a prostitute. My uncle bought me a new sari and took me to the businessman.

That man kept me for two nights. What he did to me was so painful. I tried not to cry, but I could not stop. My tears did not make him stop either. After I returned home, my brother and my uncle arranged customers for me. They were men from Bharatpur and Agra and Jaipur. Tourists also. Some were Japanese from a car factory at Neemrana. There were European men also. I have seen so many colors of skin pressed against mine.

I earned a good wage for my family doing prostitution. This made me feel proud. When I was fifteen, my uncle took me to Delhi. I did not want to leave my home. My mother protested, but what can she do? In my community a woman is only good to lie on her back. My uncle left me in a kotha [brothel] on GB Road. A gharwali [madam] named Manju paid him money. She told me I owed her Rs 20,000 [~$380] and after I repay this amount she will send money for my family. She told me my breasts must grow faster, so she gave me injections. Manju was kind to me, but if I displeased her she beat me without mercy.

There were so many girls in that place. Some were younger than me, but most were older. One girl from Nepal named Kumari was like my sister. She took care of me and taught me how to make a man finish quickly so we can have more clients and make more money. My uncle came every three, four months to collect money from Manju. He brought me gifts from my mother, like this necklace. I did not see my mother for four years while I was in Delhi. Then I became sick. I knew what happened. It happens to all the girls at GB Road. It happened to Kumari one year earlier. She did not live very long.

Clients no longer had interest in me, so Manju sent me home. That was three months ago. I live here with my family. I am grateful that the Bedia men do not marry Bedia women. This means I can never have a Bedia daughter. My uncle is upset that I cannot work. He and his brother took two girls from another village and tell customers they are Bedia. They earn money from those girls now.

I tried to get an Aadhaar4 card so I can find work, but the sarpanch5 will not endorse my application. The upper classes discriminate against us, but they line up to sleep with our daughters. I am very weak, and I know I will not live very long from now. There is a school near this village for boys. I asked the teacher if he can teach me to write. He is kind and said he will help me. I want to write a book before I die. I want to tell my story so that people know how we are treated. I want to tell the girls in my community, there is no pride in being a slave for men. Do not let them make fools of you. This is not what God wants you to do.

Sita’s eyes shivered as she spoke, but she shed no tears. She refused to pity herself, even though she recognized the bleakness of her predicament. There was no treatment available to her in the village for her HIV infection, and at barely nineteen she was forced to embrace the twilight of her life. Her tale of slavery and suffering was too bleak to bear. She was born an outcaste and a girl, two categories that sealed her wretched fate. She is the essence of slavery: a disadvantaged and oppressed individual valued only by virtue of her coerced service to those who matter more. She was never treated as equally human, equally dignified, or equally free as those who exploited her. That is the merciless formula that governs slavery in every corner of the world, from ancient times through to the modern age.

I spent several hours with Sita, as I wanted to learn as much as I could about her—as a woman, an Indian, a human. I saw glimpses of a little girl still sparkling within her battered heart. She had movie-star crushes and favorite foods, and she found solace in meditation. It was my honor to spend time with her, brief as it was.

Sita reiterated her wish to me several times—she wanted to write a book about her life, so that the Bedia girls who came after her might find the courage to reject their fates. I promised I would do my part to share her story with the world.

I knew I would never see Sita again. Before I left, I reached out my hands to her one last time. This time, she took them. I held her tight. I wanted to say so much, but only a few words emerged.

I am sorry. Please forgive us.

WHAT IS SLAVERY?

Sita was a slave, in every sense of the word. She was also a bonded laborer, a forced laborer, and a victim of child sex trafficking. To be clear, she was forced into prostitution as a child with no choice in the matter at any point in her life. Everyone but her profited from her degradation. She was exploited for the totality of her adolescence up to the point when there was nothing left to exploit. Although her case is unequivocal, the answer to the question “What is slavery?” can be quite elusive. There are many terms used in antislavery circles to describe various manifestations of the phenomenon, each of which has a codified definition in international law. However, the interpretation and application of these terms has been muddied by a lack of precision that renders it exceedingly difficult to address the offenses effectively. The terms are also used with varying agendas by the multitude of actors in the antislavery space, hence it is vital to understand more precisely just what these terms mean before one can properly address the crimes. Those terms are:

1. slavery (or modern slavery, or modern-day slavery)

2. forced labor

3. human trafficking

4. debt bondage/bonded labor

Slavery, aka Modern Slavery, aka Modern-Day Slavery

The system of slavery dates back to prehistoric hunting societies.6 The millennia that have passed since that time have provided, one might assume, ample opportunity for scholars to reach consensus as to what the word slavery means. However, the term has been applied to different modes of human subjugation in different cultural contexts across the centuries, giving it broad and sometimes contradictory meanings. The most common use of the word refers to the practice of treating people like property, or chattel, hence the term chattel slavery. For much of human history, slaves were ontologically inferior individuals who were owned by ontologically superior people. The lines between slave owner and slave were always immutable and strictly enforced by law, culture, and religion. Slaves did not have the right to exit the relationship unless it was granted to them by their owners, and their labor was exerted almost entirely for the benefit of these owners. Slaves were most often acquired through military conquest, as in the ancient Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Mughal, Aztec, and Ottoman empires. The system of treating and exploiting people as property has continued from antiquity through to the Western colonial period, the Atlantic slave trade, and into the twenty-first century.

There are, however, other systems of slavery across human history that were not as binary as traditional chattel slavery. As I describe in Bonded Labor,7 some Eastern conceptions of the institution of slavery during ancient times were more nuanced than the binary free/unfree, owner/owned system of chattel slavery. To be sure, even medieval systems of peonage and serfdom were not traditional systems of human ownership, but they still amounted to slavery and are often referred to as such. In South Asia, the concept of slavery begins with the Sanskrit word dasas, which is typically translated as “slave.” The word in fact refers to a range of subservient conditions and classes of individuals who were analogous to Western slaves. These individuals might have been owned outright, placed in a lifetime of bondage in exchange for food and shelter, sold into slavery to discharge a debt, or enslaved after military conquest. As with Western slaves, they had few, if any, rights under the law, and pathways to freedom were virtually nonexistent aside from being granted freedom by their owners. Similar systems of nuanced, caste-based or conquest-based slavery were common throughout the ancient Muslim world, the South American empires, and in Chinese and Japanese cultures. Despite these variegated manifestations of slavery, the system has always been based on expressions of power and violence, in addition to minimization of labor costs, economic exploitation, racism, sexism, alienation, and the superiority of one class of persons over another.

The first internationally accepted definition of slavery was established roughly 90 years after slavery was first abolished in the British Empire. This definition was provided in the League of Nations Slavery Convention in 1926: “Slavery is the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.”8 Per this definition, slavery is described as the condition of a person who is treated like property. Power is exerted over the person based on a legal and accepted right of human ownership. This definition would be applicable to most every instance of slavery in the pre-Abolitionist era, especially in the West. However, it has become more complicated to apply this term today because there are no longer any legal rights of ownership over human beings anywhere in the world. Indeed, the institution of owning and trading people like property has been rejected in various ways dating back to at least the third century BCE, when Emperor Ashoka outlawed the slave trade in the Mauryan Empire. Several empires and countries subsequently abolished slavery (or parts of the practice), but in most cases the system remained socially accepted and in fact almost always became legally reinstituted after it had been outlawed.

The sustained abolition of slavery as we know it began in earnest in 1807 with the Slave Trade Abolition Act in England, followed in 1833 with the Slavery Abolition Act. The post-Enlightenment era abolitionist movement spread across colonial powers, arrived in the United States in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment abolition of slavery, and continued around the world well past the League of Nations Slavery Convention with countries such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen abolishing slavery in 1962 and Mauritania as late as 2007. The crucial question in the modern context is, “If there are no legal rights of ownership of another person that convey power to the owner that can be exercised over said person, is there any slavery left in the world?”

Scholars and activists have come to use the terms modern slavery, modern-day slavery, slavery-like practices, or contemporary forms of slavery to describe the condition of a person who is treated in much the same way that slaves who were legally owned in the past were treated. Just because a condition has been made illegal on paper does not mean it does not exist in practice. Ascertaining just how these forms of modern slavery relate to the long-standing practice of traditional slavery remains unclear. In answer to this question, two camps have emerged.

The first camp asserts that modern slavery is a catch-all phrase that encapsulates all practices and conditions similar to old-world slavery, such as forced labor, human trafficking, debt bondage, and certain vestiges of old-world slavery that persist in countries like Niger, Mauritania, India, and Nepal.

The second camp asserts that the use of the term slavery should be restricted to the historic institution of chattel slavery and those few modern instances that equally manifest the extreme levels of control, abuse, and economic exploitation that were inherent in the system of chattel slavery and legal human ownership. Harvard scholar Orlando Patterson provides perhaps the most eloquent definition of slavery in this context as “the permanent, violent domination of natally alienated and generally dishonored persons.”9 Patterson argues that slavery requires severe degrees of violent domination of people stripped from their homeland and cultural contexts in a way that dishonors them as human beings. In this way, only the most extreme cases of what people describe today as modern slavery would be included, such as sex trafficking or servitude in the Thai fishing sector. Everything else would be just what it is—forced labor, bonded labor, forced marriage, severe labor exploitation, and so forth.

I have vacillated across the years on how best to use the word slavery in the modern context. The scholar in me veers toward Professor Patterson—slavery is a very specific, dehumanizing, violent form of domination and exploitation whose severity should be respected by not diluting the word to mean forms of severe labor exploitation found in the world today. On the other hand, slavery (or words that mean something like it) across cultures and time has occupied a spectrum of conditions, and perhaps it is prudent not to be too restrictive in the application of the term. To be sure, in the contemporary era one is attempting to assess a range of deeply exploitative and oftentimes dehumanizing and alienating power relationships that can be as onerous as slavery from centuries ago. The activist in me feels, therefore, that terms like modern slavery or contemporary slavery can be responsibly used as umbrella terms that capture the range of practices predicated on achieving dominance and exploitation similar to those that occurred within the old-world system of chattel slavery.

For the purposes of this book, and for general application in my antislavery work, I have for the time being sided with camp one. That is, I use the terms slavery or modern slavery as umbrella terms that describe the various faces of contemporary bondage and servitude that occur in the world today, in the hope that doing so will provide a more efficient framework for discussing the spectrum of servile labor exploitation practices. For the avoidance of doubt, I have no intention of using these terms with a view toward evoking emotional responses for the sake of sensationalism.

In my first two books, I provide definitions of slavery in a way that would allow the term to be operationalized from legal and research standpoints. This means that the definitions seek to provide clarity on the specific criteria that could be applied in criminal law or data-gathering contexts to determine whether a case is slavery. These definitions focus on the determining elements of the offense; however, I have come to feel that perhaps it would be more useful to reframe my definition in terms that are intended to capture the deeper essence of slavery in the contemporary context. I offer, therefore, a more essential definition, which can be operationalized through a determination of the conditions or indicators that would satisfy the concept:

Slavery is a system of dishonoring and degrading people through the violent coercion of their labor activity in conditions that dehumanize them.

Every person I documented in my research and determined to be a slave fulfilled this definition. These are people caught in systems of servile labor exploitation that severely dishonor and degrade them. The coercion of their labor activity (any labor that generates economic value) must contain an element of violence to descend to the level of slavery. Violence does not mean physical harm alone; rather, it indicates any manner of threat against any person who matters to the slave, as well as verbal and psychological abuses, and also the deprivation of security or sustenance as penalties for lack of submission. Finally, coercion of labor must take place in conditions that dehumanize the individual. This can mean physical conditions of filth, putridity, or other conditions that amount to a subhuman working environment. It also can mean that the individual’s freedoms are restricted—especially freedom of movement, which is a core freedom that makes us human. When the totality of these debasing conditions results in the systematic degradation of a person through the violent coercion of his or her labor activity in conditions that strip the person of his or her dignity and humanity, that, to me, is a slave.

Forced Labor

Four years after the first international legal definition of slavery, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) provided the first international legal definition of forced labor in the ILO Forced Labour Convention (No. 29): “All work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”10 The immediate context for this definition in 1930 was the recognition that chattel slavery was an institution that had been abolished from most of the planet, so a new term was needed to describe conditions akin to slavery that were not predicated on rights of ownership. The term also was defined in relation to the exploitative labor practices being perpetrated by colonial powers, in which millions of people were subjugated in slavelike conditions despite the abolition on paper of the practice.

The key elements to the ILO definition of forced labor are (1) coercion and (2) involuntariness of the labor. These terms are not defined in the convention; hence, scholars and legal experts have endeavored to determine what these terms mean and what levels of coercion and lack of consent are required to make a determination of forced labor. Scholars have established various indicators of these qualities to create an analytical basis of determination. There remains no definitive list of indicators nor a singular method through which these indicators are deemed to establish the conditions. There is, however, general consensus that some of the essential indicators to coercion include verbal, physical, sexual abuse or threats to the victim, family members, or other workers; confiscation of identity or work documents; the denial of sufficient food and water; living and working in the same place; excessive surveillance; manipulation of debts; the threat of deportation; and other measures along these lines.11 Some of the indicators of involuntariness include the inability to leave the workplace or to pursue other work options without permission; being cut off from communications with friends and family; working excessive hours without overtime payment; having to ask permission for restroom breaks; having to work despite illness or injury; not being allowed sufficient time off for rest or holidays; lack of adequate safety equipment, toilet, and sanitation; and other measures along these lines.12

There are varying approaches to the question of whether each of these indicators is to be treated equally, or whether some might be construed as “strong” and others as “less strong.” I have adopted the approach of having strong and less strong indicators in my assessments. For example, under coercion, I consider physical or sexual abuse to be strong indicators of coercion and excessive surveillance to be less strong. Under involuntariness, I consider restrictions on freedoms of movement and employment (especially when workers are locked inside the workplace) to be strong indicators, and not being allowed sufficient time off for rest or holidays to be less strong. See appendix C for an example of an intake questionnaire I used to document various forms of slavery, including the list of indicators for coercion and involuntariness I used to establish forced labor under ILO Convention No. 29.

Once one determines what indicators will be assessed and whether some are to be strong or less strong, one must then ascertain how many of the indicators are required to establish each of the conditions of coercion and involuntariness. A scoring technique of one point per indicator, or perhaps two or three points for strong indicators, can be used. The approach I have taken is that all strong indicators and at least half of the remaining less strong indicators must be present to determine each condition of coercion and involuntariness, and, of course, both conditions are required to make a determination of forced labor. This is a conservative approach that eliminates many cases that might reasonably be construed as forced labor. Having said this, if all the strong indicators are present, it is invariably the case that a majority of the remaining indicators are also present. Hence, the only alternate approach I could take would be to revert to a scoring technique that might allow for only one or two strong indicators and a handful of the other indicators to be sufficient. This would result in my having documented many more cases of forced labor across the years.

There is vigorous debate in policy circles as to whether slavery and forced labor are the same phenomenon, and if not, what the differences would be. The general consensus appears to be that slavery (when used as an umbrella term) is almost, but not quite, synonymous with forced labor. There are a few categories of slavery that are not captured by forced labor, primarily because they occur outside the context of employment, such as forced marriage,13 child marriage,14 and children in armed conflict.15 Beyond these categories, slavery and forced labor generally describe the same array of severely exploitative and degrading labor practices.

Human Trafficking

Exactly seven decades after the ILO Forced Labour Convention (No. 29), a new term entered antislavery common parlance: human trafficking. The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (2000), also known as the “Palermo Protocol,” established the first international definition of the crime of human trafficking:

“Trafficking in persons” shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.16

Most countries that subsequently established laws prohibiting human trafficking adopted definitions similar to the Palermo Protocol, usually with minor adjustments. For example, the definition of human trafficking in the United States Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 does not include the removal of organs as one of the purposes for which a person can be deemed a victim of human trafficking. Nonetheless, almost every domestic legal instrument on human trafficking includes three elements to the offense as set forth by the Palermo Protocol:

A process or action: the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of a person

Through a particular means: force, fraud, or coercion

For a particular purpose: forced labor, sexual exploitation, debt bondage, slavery, practices similar to slavery

All three elements must be present to make a determination of human trafficking, except for children, in which case the “particular means” element is not required.17 When the trafficking takes place for the purpose of sexual exploitation, it is called sex trafficking; when it takes place for the purpose of labor exploitation, it is called labor trafficking; and when it takes place for the purpose of the removal of organs, it is called organ trafficking.

No sooner had the definition of human trafficking been codified in the Palermo Protocol than did several confusions arise. These confusions continue to complicate antitrafficking and antislavery efforts to this day.

The first confusion relates to the term itself: human trafficking. The term connotes that people are being moved and that this is an essential element to the offense. The crimes of drug trafficking or arms trafficking, for example, involve the illicit transport or sale of drugs or weapons; hence, without even reviewing the definition of human trafficking one would infer that it involves the illicit movement or sale of people. This connotation led many scholars, activists, policy makers, and jurists to conclude that human trafficking must involve the illicit “traffic” of people across national borders for the purposes identified in the Palermo definition. However, it is entirely possible for a person to be “trafficked” within his or her home country (from a rural area to a city, for example). It is also entirely possible that the other processes of “obtaining” or “harboring” might not involve movement of people at all and in fact usually identify the actions of the recipient or a middle man in the victim’s journey. Hence, from the outset, the term confused the nature of the crime as being fundamentally about the movement of people, and this confusion persists no matter how many efforts have been made to clarify it.

The inherent terminological confusion relating to movement of people was reinforced by the second issue with the definition—that it is included in a supplement to a transnational organized crime convention. This contextual factor suggests that the offense is concerned with the illicit transnational movement of people, or at least it focuses on this aspect of the offense as opposed to the purpose of this movement, which is the exploitation. The primary reason the connotations of movement and illicit crossing of borders are problematic is that most of the activists and policy makers who use the term human trafficking proffer it as a synonym to the term slavery. This usage suggests that slavery involves a transnational traffic in persons for exploitative purposes, as opposed to the exploitative purposes themselves. Policy makers have worked assiduously since the Palermo Protocol to clarify that human trafficking is not about movement but rather is about slavery. They have also worked to clarify that the crime does not require movement of any kind, and that only third-party involvement in the recruitment or delivery of a person into slavelike conditions is required, or that this person is involved in the exploitation themselves. One might then ask, “Why not just call it slavery?” This question evokes the preceding question as to whether slavery is a term that should refer to the narrow array of conditions that are similar to old-world chattel slavery, or whether slavery should be used as an umbrella term that refers to all modes of servile labor exploitation found in the world today. Those who would like to use human trafficking as a synonym for the word slavery would perforce use the word as an umbrella term, but this may or may not be useful or accurate, and doing so has already led to considerable confusion as to what the term actually means. Human trafficking simply does not sound like slavery, and no matter how many times people try to use the terms as synonyms, they likely never will be comfortably or intuitively accepted as such.

The third issue created by the term human trafficking has been confusion with the crime of human smuggling.18 Human smuggling involves third parties who facilitate irregular migration across national borders, such as coyotes who help migrants without documentation cross from Mexico into the United States, or trolleys who help migrants without documentation travel from Africa to Europe. Because the phenomenon involves third parties who facilitate the illicit crossing of sovereign borders, human smuggling and human trafficking are often confused. Indeed, countless victims of human trafficking are incorrectly identified as smuggled migrants simply because they are in a country without proper documentation. As such, they are typically deported without a second look at the conditions (i.e., forced labor or forced prostitution) they might have been suffering in the destination country. For this reason, I have argued that any irregular migrant identified in a destination country should first be screened for forced labor exploitation prior to considerations of their violation of local laws, especially migration or prostitution. Human trafficking should thus be construed as human smuggling that takes place with force, fraud, or coercion prior to the movement, and forced labor or slavery after.

There are other confusions relating to the specific elements of the offense of human trafficking, namely, what actions are included under the requirements of force, fraud, or coercion, and what exactly is sexual exploitation? Is all commercial sex activity inherently exploitative, or only some? If slavery is one of the purposes of human trafficking, can human trafficking then also be used as a synonym for slavery? The overlap between the processes involved in force or coercion and many of the stated purposes of the offense—primarily being forced or coerced labor—creates additional confusion in establishing cases of human trafficking. Clearly, there is scope to tighten the definition, if not to adopt a new term that sounds more like that which it is trying to describe—that is, slavery, not irregular transnational movement.

The final and perhaps most fundamental question that has arisen since the term “human trafficking” was codified is whether it should be construed as slavery, or the process of entering a person into slavery. The answer to this question has considerable ramifications for antislavery activism, policy, and law. My recommendation is that the term “human trafficking” should be used to describe the process of entering a person into slavery, not slavery itself. This usage tightens the term to the phenomenon it is trying to describe (the traffic in people for the purpose of enslaving them) and also avoids much of the confusion that arises from the use of the term as a synonym for all forms of slavery. Using terms that more accurately describe the phenomena to which they refer is the first step in achieving the terminological and definitional clarity that can guide more effective efforts to tackle slavery in the world today.

Debt Bondage/Bonded Labor

Debt bondage or bonded labor is the most pervasive form of slavery in the world today. More people are ensnared in slavery through debt bondage than all other forms of slavery combined. Debt bondage exists in every corner of the world, but it is most heavily concentrated in South Asia. I outline the reasons for the persistence and concentration of bonded labor in South Asia in my second book, Bonded Labor.19 Some of the primary reasons include, inter alia, immense poverty, the caste system,20 corruption, a lack of access to formal credit markets, the inability of rural poor to access markets and infrastructure, and social apathy to the plight of low-caste and outcaste communities.

Debt bondage was born in feudal economies and was once the predominant mode of labor relations in agricultural settings around the world, from medieval Europe, to Mughal India, to Tokugawa Japan, to the peonage system of the American South after the Civil War.21 The phenomenon was first defined under international law in the United Nations Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery (1956) as: “The status or condition arising from a pledge by a debtor of his personal services or those of a person under his control as security for a debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited or defined.”22

In 1976, India passed its Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, which includes an extensive definition of bonded labor as a system of forced or partly forced labor in which an individual takes an advance in exchange for his or any dependant’s pledged labor or service, and is confined to a specific geographic area, cannot work for someone else, or is not allowed to sell his labor or goods at market value.23 India’s bonded labor definition covers more of the nuanced scenarios in which debt bondage exploitation can take place beyond an unreasonable asymmetry between the value of credit and labor found in the 1956 UN definition; however, the basic mechanisms and ultimate mode of the exploitation are similar.

In Bonded Labor, I include my own definition of bonded labor as:

The condition of any person whose liberty is unlawfully restricted while the person is coerced through any means to render labor or services, regardless of compensation, including those who enter the condition because of the absence of a reasonable alternative, where that person or a relation initially agreed to pledge his labor or service as repayment for an advance of any kind.24

Whichever definition one applies, debt bondage involves the exploitative interlinking of labor and credit agreements between parties. On one side of the agreement, a party who possesses a surplus of assets and capital provides credit to the other party, who, because he or she lacks almost any assets or capital, pledges his labor to work off the loan. Given the sharp power imbalances between the parties, the laborer is often severely exploited. Bonded labor occurs when that exploitation becomes so severe that it manifests as slavery. In these cases, once the capital is borrowed, numerous tactics are used by the lender to extract slave labor. The borrower is often coerced to work for meager wages to repay the debt. Exorbitant interest rates of 10 to 20 percent per month are charged, and additional money lent for medicine, clothes, or basic subsistence is added to the debt. In most cases of bonded labor, up to one-half or more of the debtor’s wages are deducted for debt repayment, and further deductions are often made as penalties for breaking rules, poor work performance, or at the whims of the exploiter. Sometimes the debts last a few years, and sometimes the debt may be passed on to future generations if the original borrower perishes without having repaid the debt (according to the lender). Most often, the terms of debt bondage agreements last a few years or can be on a seasonal basis in certain industries, such as agriculture.

The existence of debt bondage outside of South Asia is most often initiated through up-front fees that a debtor is forced to pay to a recruiter to secure identity documents, training, work permits, and travel for a work opportunity in a foreign country, usually in construction, domestic work, seafood, agriculture, or commercial sex. Bonded Labor covers the phenomenon’s existence in South Asia, and I outline the practice of debt bondage beyond South Asia in chapter 6 of this book.

Scholars, economists, and policy makers have asked whether debt bondage should be considered slavery.25 The question usually centers on the issue of whether the debtor willingly enters into the agreement, in which case this voluntary entry would vitiate the element of coercion typically required to establish slavery. Where slavery is used as an umbrella term, debt bondage is undoubtedly included. Where slavery is used more restrictively, most cases of debt bondage I have documented would still be considered slavery, but many cases of seasonal bonded labor or less severe cases of debt bondage in which the debtor may have alternatives or not be as aggressively coerced, manipulated, and exploited may not apply. I have focused on these more severe cases of debt bondage in my research, of which there are millions around the world, and I have no problem categorizing them as slavery.

Overlapping Categories

It is vital to note that there is substantial overlap between the aforementioned categories of servile labor exploitation. Any one person could easily belong to two, three, or even all four categories, which in some sense argues for the use of slavery as an umbrella term that captures these similar and highly overlapping practices. For example, many victims of labor trafficking in California’s agricultural sector (see chapter 3) are also victims of debt bondage. Debt bondage victims in domestic work or construction (see chapter 6) are also very often victims of labor trafficking. The exploited individuals in Thailand’s seafood industry (see chapter 7) are almost all victims of labor trafficking and debt bondage. Most of these victims also would be considered forced laborers, and all of them must be considered slaves. Nonetheless, when it comes to categorization by type of slavery, there are invariably certain indications as to the dominant mode or nature of the exploitation. Identifying these dominant modes is crucial when it comes to considerations of how to address the abuses. Appendix A describes my approach to categorization in more detail and acknowledges the substantial overlaps between these categories.

One of the most crippling deficiencies of the contemporary antislavery movement has been a lack of reliable data. This data deficiency has hampered efforts to persuade governments and charitable foundations to invest sufficient funds and attention to the issue, to persuade corporations that their supply chains might be tainted by various forms of slavery, and to establish legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of the world. Rather than focus on research, the movement has historically focused on sensationalism and emotional rhetoric. The atmosphere began to change around the turn of the last decade when the antislavery movement finally began to devote more attention to data and measurement. Since that time, there has been a marked increase in the number of data-driven research projects on various aspects of slavery. There are still substantial gaps, but I am confident these will be filled in due course. Two of the most important questions about slavery finally receiving meaningful attention are “How many slaves are there?” and “How much profit is generated from their exploitation?”

The Number of Slaves in the World

My estimate of the number of slaves in the world at the end of the year 2016 is 31.2 million. This number is broken down into three categories:

Debt bondage: 19.1 million

Human trafficking: 4.8 million

Other forced labor:26 7.3 million

Although my model on the number of slaves in the world by type requires extrapolation, I have strived to be as conservative as possible in all calculations. Refer to appendix A for further details and discussion on the derivation of the numbers.

Table 1.1 provides a breakdown of each type of slavery by region. Roughly six out of ten slaves in the world are in South Asia. This is primarily a function of the fact the approximately 80 percent of the world’s debt bondage slaves are in the region. It is also a function of the fact that the region possesses roughly 70 percent of the people in the world living in poverty. South Asia is unquestionably ground zero for slavery, but Africa and the Middle East also contain relatively high per capita levels of slavery.

TABLE 1.1 Number of Slaves by Region, 20161

| |

DEBT BONDAGE/BONDED LABOR |

HUMAN TRAFFICKING |

OTHER FORCED LABOR |

TOTAL SLAVES |

PERCENT OF TOTAL (%) |

| South Asia |

15.5 |

1.3 |

2.3 |

19.1 |

61.2 |

| East Asia and Pacific |

1.5 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

5.1 |

16.3 |

| Western Europe |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

2.9 |

| Central and Eastern Europe |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

2.9 |

| Latin America |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

1.2 |

3.8 |

| Africa |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

5.8 |

| Middle East |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.9 |

6.1 |

| North America |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

| Total |

19.1 |

4.8 |

7.3 |

31.2 |

100.0 |

There are two other credible estimates of the number of slaves and forced laborers in the world: one from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and one from the Walk Free Foundation. The ILO has published two estimates on the number of forced laborers in the world (not exactly the same as slaves). In 2005, they estimated there were 12.3 million people in forced labor,27 and in 2012 they estimated there were 20.9 million people in forced labor.28 The increase from 2005 to 2012 is not based on actual increases in forced labor but rather on an improvement in sample size and methodology and extrapolation assumptions. I was engaged by the ILO as one of a handful of experts to advise on the 2012 estimate and can confirm that the process was both rigorous and conservative. The estimate is based on a capture-recapture (CR)29 sampling methodology of reports of forced labor by NGOs and the media, which are then entered into an extrapolation model to generate forced labor estimates by region. The ILO continues to refine its estimate every few years, and I believe it produces the most reliable estimate of forced labor in the world.

The other estimate comes from the Walk Free Foundation, which produces a “Global Slavery Index” (GSI). This index provides estimates of the number of slaves in the world based on household surveys conducted by the Gallup organization. The most recent estimate in 2016 is that there are 45.8 million slaves in the world.30 The GSI provides estimates by country as well, with the top countries being India (18.3 million), China (3.4 million), Pakistan (2.1 million), Uzbekistan (1.2 million), and North Korea (1.1 million).31 On a percent of total population enslaved basis, the countries with the highest levels of slavery are North Korea (4.4 percent), Uzbekistan (4.0 percent), Cambodia (1.6 percent), Qatar (1.4 percent), and India (1.4 percent).32

These three estimates provide a range of roughly 21 to 46 million people in forced labor or slavery in the world. I suspect the truth is somewhere in between these numbers. One cannot compare them fully, as they use different methodologies, rely on different sources of data, make different assumptions that are used for extrapolation, and apply different definitions. Still, they constitute more rigorous estimates than were being produced a decade earlier and provide a reasonable sense of the scale of slavery in the world today.

The Profits of Slavery

Only two estimates of the profits generated by slavery and forced labor are available: one produced by the ILO and one produced by me. In 2005, the ILO estimated that the 12.3 million forced laborers in the world generated profits for their exploiters of $32 billion.33 In 2012, the ILO estimated that the 20.9 million forced laborers in the world generated profits for their exploiters of $150 billion.34 The sharp increase in profits is not strictly linked to the increase in the number of forced laborers in the estimates; rather, it is the result of a more refined economic model of forced labor, including the fact that forced prostitution is responsible for $100 billion, or two-thirds, of this estimate. The ILO’s updated estimate of forced prostitution profits was partially drawn from my estimates in Sex Trafficking.35 The ILO’s most current data suggest the average annual profits per forced laborer is approximately $7,175. In Sex Trafficking, I estimated there were 28.4 million slaves in the world generating $92 billion in profits for their exploiters, with sex slaves being responsible for almost 40 percent of these profits. My current estimates are that the 31.2 million slaves in the world generate $124.1 billion in profits for their exploiters, with sex slaves being responsible for $62.3 billion, or 50.2 percent of the profits, even though they represent only 5.8 percent of the total slaves in the world (see appendix A for details). These data suggest global weighted average annual profits per slave of $3,978, with a high of $36,064 in annual profits per sex trafficking victim, and a low of $1,056 per debt bondage slave. Table 1.2 summarizes the key data on total slaves/forced laborers and profits.

TABLE 1.2 Summary of Slavery Estimates and Metrics

| |

ILO (2012) |

WALK FREE (2016) |

KARA (2016) |

| Total Slaves/Forced Laborers |

20.9 million |

45.8 million |

31.2 million |

| Total Annual Profits |

$150 billion |

— |

$124 billion |

| Annual Profits per Slave1 |

$7,175 |

— |

$3,978 |

| Average Cost of a Slave1 |

— |

— |

$550 |

| Annualized ROI of a Slave1 |

— |

— |

383% |

1“Kara” values are global weighted averages.

Sources: ILO Data from “ILO Global Estimate on Forced Labor” Geneva, 2012; Walk Free Data from www.walkfree.org.

In addition to data on total slaves and the profits generated by slavery, I have calculated that the global weighted average cost of a slave is $550. The global weighted average annualized return on investment (ROI) of all forms of slavery is 383 percent (see appendix A for details).

Comparative Analysis of Slavery

From the early days of my research, it was clear to me that slavery is motivated by greed. Slavers are not cruel and exploitative simply for the sake of it. They are cruel and exploitative in pursuit of what they really want—profit. This focus on the profit motive of slavery guided much of my data gathering as I sought to understand just how profitable modern slavery is. As it turns out, slavery today is more profitable than I could have imagined. Profits on a per slave basis can range from a few thousand dollars to a few hundred thousand dollars per year, with total annual slavery profits estimated to be as high at $150 billion (ILO). These astounding numbers made me wonder how the profitability of slavery today compares to slavery centuries ago. As I investigated this comparison further, several contrasts between old-world slavery and modern-day slavery emerged, and these contrasts made it abundantly clear exactly why slavery persists and permeates almost every corner of the global economy.

Table 1.3 highlights some of the most important comparisons of slavery two centuries ago versus today. The first difference is that slave trading/human trafficking two centuries ago involved lengthy, expensive journeys as compared to quick, inexpensive journeys today. Centuries ago, it could take months or more to transport a slave from the point of origin in Africa or the Middle East to the point of exploitation in the Americas or Asia. For example, in the Atlantic slave trade, the slave was first acquired somewhere in the interior of the African continent and transported to the West African coast. Around 20 to 25 percent of slaves perished during this portion of the journey.36 Once at the coast, the slaves were purchased and transported across the Atlantic to the Americas. Another 10 to 15 percent of slaves perished during this stage, known as the “Middle Passage.”37 The very time-consuming and expensive nature of the transport, as well as the high mortality rate during the journey, meant that when a slave finally arrived in the Americas and was auctioned for sale, the price was not cheap. Prices were also pushed upward because it could very well be quite some time before a new slave would be available to purchase should something happen to the former one. By contest, slaves today can be transported from one end of the planet to the other relatively quickly and for a small cost compared to the profits enjoyed through their exploitation. I am not aware of any mortality rate studies on modern slavery transport, but results from my own research indicate a fairly low percentage. All in all, the entire proposition of transporting slaves is significantly cheaper, quicker, and involves much less attrition than at any point in human history.

TABLE 1.3 Comparative Analysis of Old World Slavery to Slavery Today

| OLD WORLD (1810) |

TODAY (2016) |

| Lengthy, expensive journeys to transport slaves |

Short, inexpensive journeys to transport slaves |

| Limited avenues for exploitation (agriculture, domestic work, construction) |

Numerous avenues for exploitation (dozens of industries) |

| Weighted average cost of a slave: ~$4,900–$5,500 (2016 USD) |

Weighted average cost of a slave: ~$550 |

| Weighted average annual ROI: 10–20% |

Weighted average annual ROI: ~170–1,000% |

| Typically enslaved up to a lifetime |

Typically enslaved a few years or less |

| Legal rights of ownership over other human beings |

No legal rights of ownership over other human beings |

The second comparison is that in old-world slavery the industries in which slaves could be exploited were limited primarily to agriculture, domestic work, construction, and certain skilled trades, such as blacksmith. Other slaves were forced into military service, and, of course, slaves were sexually exploited by their owners. Of all these sectors, only agriculture generated meaningful and large-scale profits, which were nevertheless limited to one or two harvests per year depending on the crop. Slaves were forced into brothels as well, but commercial sex and sex tourism were not nearly the bourgeoning businesses they are today thanks to the speed and inexpensiveness of travel. Unlike the past, slaves today are exploited in dozens of industries linked to the global economy, including agriculture, mining, construction, apparel, manufacturing, seafood, beauty products, and commercial sex. In short, slaves are exploited in more industries than ever before, almost all of which generate significant profits.

The third comparison was the most challenging for me to assess: the average cost of a slave. To make the comparison, I gathered data on the prices of slaves during the early 1800s and compared these data to acquisition prices I gathered for slaves today. Data on slave prices from centuries ago is patchy and inconsistent. Slave prices tend to be more available for slaves sold in the American South and in the territories of the East India Trading Company than for sales in Africa, South America, and the Middle East. Nonetheless, I can safely say that two centuries ago there was a wide variance in the acquisition costs of a slave, anywhere from $0 for a person born into slavery to upward of $30,000 in 2016 U.S. dollars38 for a young, healthy African male slave sold in the American South. Premiums were also paid for certain skills, such as blacksmith or carpenter, and discounts for other qualities, such as older age or physical impairment.39 I was not able to determine a precise global weighted average price of a slave two centuries ago; however, I feel confident saying that the number is somewhere between $4,900 and $5,500 in 2016 U.S. dollars. My data for slaves in the modern age is more comprehensive. As with the old world, the range is wide, anywhere from $0 for a person born into slavery to upward of $10,000 for a trafficked virgin sex slave sold in Western Europe or North America. However, the global weighted average is much lower, approximately $550. The weighted average is pulled down significantly by the high number of debt bondage slaves in South Asia, most of whom are in lower-profit sectors such as agriculture, apparel, or stone breaking and have correspondingly lower acquisition costs of anywhere from $50 to $500. Although slaves can be relatively expensive even today, there has been a sharp downward trend in the acquisition cost of a slave across the last two centuries of more than 90 percent. This downward trend in slave prices is primarily driven by (1) a sharp increase in the total number of people living in poverty and other highly vulnerable conditions, (2) a sharp drop in transportation costs, and (3) a sharp increase in transportation speed. These three factors create a nearly limitless supply of potential slaves who can be readily acquired and quickly and inexpensively moved from a point of origin to a point of exploitation, driving down the cost of slaves in general. A fourth element relates to mass migration events, almost always catalyzed by military conflict or environmental catastrophe, which also helps make slaves much cheaper than before; in essence they are transporting themselves from the point of origin to a point of exploitation and need only be recruited by a trafficker/slave exploiter at some point along the way.

The fourth comparison relates to the profitability of slavery, as measured by annual return on investment (ROI).40 In the old world, I calculate the ROI of slavery to be around 10 to 20 percent per year. The ROI was primarily generated through agricultural work and semiskilled trade work. Slavery in domestic work and construction is economically beneficial through the avoidance of costs, which also can be construed as profit because the expense savings can be used for other capital investments. The much higher average up-front costs of a slave in the old world places significant downward pressure on the annual ROI. The annual ROI with slavery in the modern era, however, can be anywhere from 170 percent for debt bondage slaves to over 1,000 percent for sex trafficking. This astounding upward shift in the profitability of slavery is primarily a function of the sharp drop in the up-front price of a slave and a significant increase in the number and variation of sectors in which slave labor can be profitably exploited. The ROI metric alone explains the prevalence and persistence of modern slavery—it is far and away more profitable now than at any point in human history.

The preceding comparisons give rise to a fifth comparison: in the old world slaves tended to be exploited for their lifetimes, whereas today individuals are exploited for much shorter periods of time. Due to the significant up-front costs of a slave centuries ago, and the relatively modest rate of capital recoupment, the slave owner tended to exploit his slave for a longer period of time. That is not to say that slaves were not killed, brutalized, or bartered between slave owners, but in any scenario they were by and large slaves for most, if not all, of their lives. There are certainly slaves today who are exploited for decades or longer, especially in certain forms of generational debt bondage or hereditary slavery that persist in Asia and Africa. However, most slaves, especially trafficked slaves, may be exploited for just a few months or at most a few years. These individuals may endure repeated spells of slavery throughout their lives, but in totality the aggregate duration of slavery today is much shorter than in the past. This shift is primarily due to the fact that the capital investment for acquiring a slave is much less today and can be recouped within just a few months. After that point, the slave owner is generating massive profits. There is a ready supply of countless new potential slaves who can be acquired quickly and inexpensively, so the slave exploiter can also chew up his slave, spit him out, and acquire a new one with relative ease. Because slavery is no longer legal, this increased turnover also allows the slave exploiter to minimize risks associated with keeping a single slave for too long, given the chances that she or he may form ties with someone who could help with escape, or the slave may try to escape him- or herself, which could potentially lead to an investigation by law enforcement, even if rarely. In a way, human life has become more expendable than ever before. Slaves can be acquired, exploited, and discarded (or worse) in relatively short time periods and still provide immense profits for their exploiters.

The sixth and final comparison relates to the legal status of slavery. In the old world, slavery was legal, accepted, and normal. One could buy and sell people under the law and exert power over them as if they were any other form of property. Today one cannot legally own another human being; however, power can still be exerted over them as if they were property. The illegality of slavery and its rejection by humanity would suggest that there is meaningful risk associated with attempting to re-create the practice. For various reasons outlined later in this chapter, there is still an appallingly small level of risk associated with most of the slave exploitation that takes place in the world today. This deficiency in the global response to slavery has allowed the practice to persist in various forms across the global economy—often in the shadows but in broad daylight as well. Until slavery is perceived as a high-cost and high-risk form of labor exploitation, this reality will not change.

The aforementioned six comparisons give rise to a crucial thesis on modern slavery:

The immensity and pervasiveness of slavery in the modern era is driven by the ability of exploiters to generate substantial profits at almost no real risk through the callous exploitation of a global subclass of humanity whose degradation is tacitly accepted by every participant in the economic system that consumes their suffering.

The four elements to this thesis that must be addressed are (1) immense profits, (2) lack of real risk, (3) vulnerable subclass of humanity, and (4) tacit acceptance of the suffering of slaves. First, the profitability of slavery must be eliminated. Second, efforts to do so must be tied to the creation of significant risk associated with slave exploitation so that the perception of any rational economic actor is that the crime does not pay. Third, efforts must be made to protect and empower the global subclass of humanity upon which traffickers and slave exploiters most often prey, especially women, children, and minority ethnic communities. Finally, a radical shift in global consciousness is required; namely, a permanent rejection of the apathetic and deplorable acceptance that it is reasonable to inflict servitude on the downtrodden so long as their suffering is transformed into the cheap and delightful goods we purchase every day.

Throughout this book I endeavor to describe the array of efforts that I feel can achieve these goals by inverting the core thesis that drives modern slavery.

SUMMARY OF CASES DOCUMENTED FOR THIS BOOK

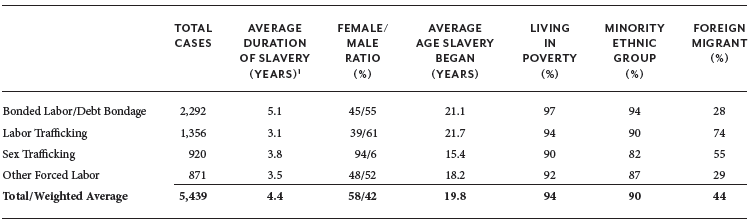

The data and trends described in this book and the appendixes that form the foundation of my arguments of how to eradicate slavery are drawn from a total of 5,439 cases of slavery that I have documented since the beginning of my research in the year 2000. One of the questionnaires I used to document these cases can be found in appendix C. Table 1.4 provides a summary of some of the key metrics from the data I collected.

TABLE 1.4 Summary Metrics of Slavery Cases Documented

1Includes assumptions by type of slavery as well as considerations as to whether the individual was documented during or after a spell of slavery so that between one-fifth and one-half of the total duration of servitude remains after the point the individual was documented.

I did not keep track of all of the incomplete cases I attempted to document, but I have a good sense that this number is at least five times the total number of cases I was able to document in full. I may not have been able to complete an interview with a potential slave for a number of reasons: he or she may not have wanted to finish the conversation out of fear or discomfort; he or she may not have been able to provide enough information for me to include the case in my findings; or there may have been interruptions or other problems with the interview.

Throughout my research, I upheld two principles: (1) do no harm and (2) the least important aspect of my research is my research. I always erred on the side of extreme caution in putting informants or their families in a situation that might cause any discomfort or risk. I never prioritized trying to document a case over adhering to this principle. I followed Institutional Review Board principles on human subject research at all times,41 including the practice of explaining my intentions and the purpose of the questions before asking for consent to speak, never asking questions without consent, and never documenting or publishing identifying information on the informant that could put the person at risk. With minors, I asked for consent from a responsible adult where one was available (usually parents or the person running the shelter), or assent from a child when there was not a responsible or trustworthy adult present (usually in places of exploitation). It is impossible to conduct firsthand research into slavery without putting oneself at risk, and it is impossible to avoid all possible risk factors for the informant, but I made every effort to minimize these risks, and when in doubt, I refrained from pushing forward.

KEY FEATURES SHARED BY SLAVES

The slaves I have documented share a handful of key features, and understanding these features is necessary to guide more effective antislavery efforts. Not every slave possesses every one of these features, and some features are more prevalent than others, but the following elements consistently appear in the cases I documented.

Poverty

Roughly 94 percent of the slaves I have documented lived in chronic poverty or had fallen into poverty not long before their exploitation began. Poverty is the most common feature shared by slaves today, and it is perhaps the most powerful indicator of vulnerability to potential enslavement. When one considers that approximately 40 percent of the planet, or 3.1 billion people, live on incomes of less than $3.10 per day, it is reasonable to posit that there is a near limitless supply of potential slaves around the world. Extreme poverty drives risky migration and acceptance of an offer from a recruiter/trafficker even if the individual knows it may lead to a negative outcome. For these and other reasons, poverty is unquestionably one of the most merciless forms of violence and injustice in the world, and it invariably leads to a plethora of human rights catastrophes. That we live in a world in which the top 100 wealthy individuals have more combined wealth than the bottom 3.5 billion people combined represents a complete failure of the contemporary economic order. Global capitalism must take responsibility for promoting these indecent income disparities and for perpetuating an economic system that is both unjust and unsustainable.

Minority Ethnicity or Caste

Approximately 90 percent of the slaves I documented belonged to minority ethnic groups or low-caste/outcaste communities. These communities tend to be the poorest and most disenfranchised people in mainstream societies. They lack access to education, economic opportunity, basic rights, and social safety nets, all of which render them ever-at-the-edge of catastrophe and almost-always-ready to accept offers that lead to servitude. Caste is a particularly powerful force of social oppression whose persistence can be found primarily in South Asia and Africa. Bonded labor in South Asia is the form of slavery in which I found the highest proportion of outcaste communities, with more than 99 percent of cases. Whether it is the Roma in Europe, hill tribes in the Mekong subregion, dalits in South Asia, indigenous peoples in South America, or tribal people in Africa, the lower classes of the world are deemed less equal as human beings by those in the upper classes/castes; hence, their exploitation is oftentimes (and perversely) seen as a beneficial outcome for them, as well as a condition natural to them. These anachronistic attitudes permeate the consciousness of mainstream societies in most parts of the world, distorting social relations, prejudicing economic and judicial systems, and perpetuating the oppression of the lower classes with impunity.

Foreign Migration

Approximately 44 percent of the slaves I documented were foreign migrants. This figure does not include domestic migrants who had traveled from a rural area to an urban center in the same country in search of work. The highest levels of foreign migration were perforce in the cases of human trafficking for forced labor and forced prostitution. The movement abroad may have resulted from lack of a reasonable options for income and survival in their home country or from en masse distress migration due to military conflict, social collapse, or environmental catastrophe. Refugee camps are a common source of recruitment by traffickers. Being a foreign migrant renders individuals inherently more vulnerable and divorced from basic rights and protections. It also promotes high levels of isolation that directly facilitate slavery. Of all the slaves I documented who were foreign migrants, 61 percent of them migrated on an irregular basis. Internal migration also can lead to isolation and lack of access to rights, such as seasonal brick-making migrants who move from one state to another in India, or urban slum dwellers in Brazil who migrate to the Amazon interior for forced labor in logging or iron smelting. Of equal interest are those cases that do not involve migration. These cases tend to involve debt bondage in South Asia in sectors such as agriculture, beedi rolling, or stone breaking, as well as people who live in urban slums who end up in forced labor and vulnerable teens who end up in forced prostitution in their home cities. Although migration is not necessary for slavery, mass migration events are particularly sourced by opportunistic human traffickers to recruit new victims.

Other Features Shared by Slaves

Several other features are common to the slaves I documented. A majority of them were isolated—both before being enslaved and even more so during their enslavement. Isolation from social protections, infrastructure, markets, health care, and education are strong predictors of various forms of exploitation, including slavery. A lack of education and literacy are also common factors. Unstable family units, lack of access to formal credit markets (especially in debt bondage cases), and statelessness are common features in many of the cases of slavery I have documented.

The final feature shared by almost every slave that I met across the years is in some ways the most crucial—the lack of a reasonable alternative. To be sure, the aforementioned features all contribute to creating a situation in which an individual does not have any reasonable alternative to entering him- or herself or a family member into a condition of servitude. When faced with conditions of extreme poverty, violence, displacement, low-caste status, or other vulnerabilities, no amount of awareness of the possibility of being exploited can deter an individual from accepting an offer whose outcome is likely to be slavery.42 Sadly, slavery might end up providing levels of food and shelter that are a relative improvement over the individual’s alternative. This improvement is often cited by slave exploiters as justification that the individual is not being exploited but in fact is being done a favor. On the contrary, the fact that slavery can in some cases be a welfare-enhancing condition for an individual is no justification for the validity of slavery. It is a biting indictment of our collective failure to provide a decent existence for all people on this planet.

FORCES THAT PROMOTE SLAVERY

To design an effective response to slavery, it is vital to understand the forces that promote slavery around the world. I believe the most helpful way to frame these forces is in terms of supply and demand.

The supply-side forces of slavery are informed by the features that slaves share. Forces such as poverty, minority ethnicity, migration, gender violence, lack of access to formal credit markets, lack of education, and population displacement are some of the chief forces that promote the supply of potential slaves. In addition, the supply of slaves is promoted by systemic forces such as corruption, lawlessness, military conflict, and societal apathy for the plight of slaves. These and other forces have facilitated the supply of potential slaves for centuries. All of these supply-side factors must be addressed, though even the most optimistic activist would concede that substantial reductions in poverty, gender violence, minority bias, and corruption will take time. Accordingly, I have focused more on analyzing the demand-side forces of slavery, which I believe are more vulnerable to near-term intervention.

Demand-Side Forces

The specific forces of demand for any particular sector that exploits slaves varies. For example, male demand to purchase women and children for sex is an essential component to the demand side of the sex trafficking industry but is not present in slavery in the seafood sector. However, for any industry that exploits slaves, there are always two economic forces of demand: (1) exploiter demand for maximum profit and (2) consumer demand for lower retail prices. A closer look at these two forces reveals both the optimal points of intervention in the business of slavery and the underlying logic of the system as it exists today.

For almost any business, labor is typically the highest cost component to operating expenses, representing anywhere from 25 percent to 50 percent of costs depending on the industry. Throughout history, producers have tried to find ways to minimize labor costs. Slavery is the extreme of this effort because slaves afford a virtually nil cost of labor. With drastically reduced labor costs, total operating costs of the business are substantially reduced, allowing the company to maximize profit. However, significantly lower labor costs also allow producers to pursue another imperative—to become more competitive by lowering retail prices. The need to lower retail prices is driven in large part by consumer demand to pay less for goods and services. In a globalized economy where products are available to us in nearby shops from all over the world, the need to be competitive on price is greater than ever. This globalization of competition is one of the key differences between the economic logic of old-world slavery and slavery in the context of the global economy. Producers are not just competing with the company down the road but with companies from all over the world. As a result, slavery and other forms of severe labor exploitation have evolved from the old world into the globalized world as a means through which unscrupulous producers compete to advance profits as well as to maximize price competitiveness. Underregulated labor markets are targeted by producers to minimize labor costs, be it the seafood sector of Thailand, mobile phone manufacturing in China, or garment production in Bangladesh. I contend that there is a tacit understanding between Western multinationals (and their governments) and the governments of developing economies to look the other way regarding labor conditions so profits and price can be optimized. This relationship is a driving force of global capitalism, and it has resulted in vast increases in suffering among the poorest and most disenfranchised people of the world.

Consumers understandably prefer goods and services that are less expensive. However, if consumers were to find out that their food, mobile phones, and clothes are produced through slavery or child labor, they might opt to pay a little more for goods that they could be sure were untainted by severe labor exploitation. Just how much more a consumer would be willing to pay for an untainted good would depend on the good itself, as well as the reliability of the assurance that it is untainted. Many consumers may nevertheless not have sufficient disposable income to pay more for untainted goods, so one might reasonably ask whether they have a right to access cheap goods even if the price point can only be achieved through labor exploitation. I believe this is a false question because there will almost always be some profit margin that the seller could forgo to provide goods at prices that even relatively poor consumers could still afford. These hypotheses must be tested through research, but I contend that most people do not wish to wear clothes or eat food produced through slavery. As consumers become aware of the tainted nature of many global supply chains, I believe they will express a demand to be sold untainted goods. The next stage in antislavery activity must therefore involve cooperation by industry, governments, and nonprofits to formulate a reliable and economically viable system of supply-chain certification to meet the demand by consumers that the goods they purchase are free of slavery and child labor. Consumer demand is one of the most powerful forces that can help achieve a near-term change in the system of slavery around the world; however, one sector is left out of this consumer-based argument, and that is commercial sex.

In my experience, consumers of commercial sex are less sensitive to the possibility that the service they are purchasing is provided through slavery. They are, however, sensitive to price and risk. In Sex Trafficking, I presented a hypothesis that male demand to purchase commercial sex is highly elastic. This thesis suggests that consumer demand fluctuates significantly relating to shifts in price. I corroborated this hypothesis with a small sample size of four male consumers in a brothel in India, whose demand curve demonstrated an elasticity of demand of 1.9 (highly elastic).43 I have since completed a more extensive survey of sixty male consumers of commercial sex in India, Denmark, Mexico, and the United States. Although there is variation between countries, the aggregate demand curve of all sixty male consumers is 1.82. This indicates that when the retail price of a commercial sex act doubles, demand among these sixty consumers drops by 76 percent. This result reinforces the hypothesis in Sex Trafficking and affirms that demand-side interventions have the most potential to reduce sex trafficking in the near term.

The results of this research also led me to think about a new set of demand-side tactics to attack sex trafficking. Although the demand curve establishes an economic elasticity, implied in this result is the fact that male demand to purchase cheap sex could very well be sensitive to deterrence-focused interventions in addition to those predicated on creating upward shocks in retail prices. Put another way, if demand fluctuates significantly based on price, it can very well fluctuate significantly based on risk, achieved via efforts to deter the purchase more directly. Interventions focused on deterring the purchase of commercial sex can best be tested in jurisdictions where the purchase is criminalized. One can then measure policies such as prison time, naming and shaming, or placement on a sex offender list, among others. Policies like these are being tested in small pockets around the world, with some of the most interesting and persuasive work being done by Demand Abolition, based in Boston. I believe that demand-side efforts to elevate cost and risk to the consumer (and trafficker) provide the best chance of having a major impact on the business of sex trafficking. And make no mistake, sex trafficking, like all forms of slavery, is a business.

THE BUSINESS OF SLAVERY

Slavery is a business, and the business of slavery is thriving. Despite substantial increases in awareness of slavery in recent years, a plethora of new laws on the issue, and a newfound focus on research, the global climate remains relatively friendly to the business of slavery. As a result, systems of human servitude persist around the world. Put another way, the drive to capitalize on the underregulated labor markets that feed the business of modern slavery remains more powerful than efforts to rid the world of slavery. As a result, slavery and other forms of severe labor exploitation have become embedded in much of the global economy.

Slavery remains good business primarily because that business generates substantial profits. In an effort to understand just how profitable the business of slavery is, I introduced the concept of the “exploitation value” (EV) of a slave in Sex Trafficking.44 This crude economic term is not intended to elide the immeasurable human costs of the crime but to frame just how profitable a slave in various sectors can be to his or her exploiter. Knowing this information helps guide more effective policies, laws, and penalties intended to thwart the offense.

The global weighted average exploitation values of a slave in the primary categories of slavery found in the world today are:

| Sex trafficking |