5

From Probus to Diocletian

5.1.1.

The accession of Bahram II (276±293)

Agathias IV, 24, 6: Varanes’ (i.e. Bahram I’s) son1 had the same name as his father and reigned for seventeen years.

(Cameron, p. 123)

5.1.2.

Peace between Probus and the Persians

SHA Prob. 17, 1–6: Having finally established peace in all parts of Pamphylia and the other provinces adjacent to Isauria, he turned his course to the East. 2. He also subdued the Blemmyae,2 and the captives taken from them he sent back to Rome and thereby created a wondrous impression upon the amazed Roman people. 3. Besides this, he rescued from servitude to the barbarians the cities of Coptos and Ptolemais and restored them to Roman laws. 4. By this he achieved such fame that the Parthians (sic) sent envoys to him, confessing their fear and arrogance and then went back to their homes in greater fear than before. 5. The letter, moreover, which he wrote to Narseus (sic),3 rejecting the gifts which the king had sent, is said to have been as follows: ‘I marvel that you have sent us so few of the riches, all of which will shortly be ours. For the time being, keep all those things in which you take such pleasure. If ever we wish to have them, we know how we ought to get them.’ 6. On the receipt of this letter Narseus was greatly frightened, the more so because he had learned that Coptos and Ptolemais had been set free from the Blemmyae, who had previously held them, and that they, who had once been the terror of nations, had been put to the sword.

(Magie, iii, p. 371)

Moses Khorenats’i, Hist. Arm. (II), 77 (Thomson, p. 224): see Appendix 2, p.

5.1.3.

Probus' plan to invade Persia and his death (282)

SHA Prob. 20, 1: These spectacles finished, he made ready for war with Persia,4 but while on the march through Illyricum he was treacherously murdered by his soldiers.

(Magie, iii, p. 377)

5.1.4. Dedication to Probus by Syrian villagers (?282)

IGR III, 1186 (=PAES no. 765.12, Greek dedication on a block built into the front wall in a building called Kalybe from the inscription on the northern edge of the village of Um Iz-zetun): Good fortune! For the preservation and victory of our lord Marcus Aurelius Probus Augustus, in (the) seventh year was built the sacred kalybe by the community of the village, successfully.

(Littman-Magie-Stuart, no. 765)

5.1.5.

Internal unrest in Persia (c. 283)

Pan. Lat. III/11, 17, 2, ed. Galletier, p. : Ormias (i.e. Hormizd),5 with the support of the Sakas and the Rufii6 and the Geli,7 attacked the Persians themselves and their king whom he did not respect as sovereign for the sake of majesty nor as a brother for the sake of piety.

(Dodgeon)

5.1.6.

The Persian Expedition of Carus, his initial success and his death (283)

Julian, or. I, 17D–18A (13.16–18, Bidez): Nor need I (i.e. Julian) recall the second chapter of our misfortunes and the exploits of Carus that followed, when after those failures he was appointed general?

(Wright, i, p. 45)

Chronicon anni 354, p. , 17, MGH: Carus: emperor for ten months and five days. He died in Seleucia in Babylonia.

Aurelius Victor, liber de Caesaribus. 38, 2–4: Because all the barbarians, informed of Probus’ death, had, at this opportune moment, invaded the empire, Carus (having first sent his eldest son to protect Gaul) immediately left for Mesopotamia, accompanied by Numerianus, for that country is exposed, as it were, to perennial invasions by the Persians. 3. There he routed the enemy but while passing immodestly and vaingloriously beyond Ctesiphon, the famous city of Parthia, he was consumed by a thunderbolt. Indeed they report that it deservedly happened to him: for when the oracles had informed him that he could advance in victory as far as the above mentioned city, he had proceeded further and paid the penalty. 5. Accordingly it is difficult to change destiny, and for that reason a knowledge of the future is redundant.

(Dodgeon)

Festus, brev. 24, p. , 6–11: The victory over the Persians of the emperor Carus seemed to be too mighty in the eyes of divine power. For it undoubtedly incurred divine displeasure and indignation. For when he entered Persia, he devastated it as if no one was defending it, and captured Coche8 and Ctesiphon, the most distinguished cities of Persia. When in victory he had his camp above the Tigris, he died after being struck by a bolt of lightning.

(Dodgeon)

Eutropius, IX, 18, 1: While he (i.e. Carus) was engaged in a war with the Sarmatians, news was brought of an insurrection among the Persians. He set out for the East, and achieved some noble exploits against that race of people; he routed them in the field, and took Seleucia and Ctesiphon, their noblest cities, but, while he was encamped on the Tigris, he was killed by lightning.

(Watson, p. 522, altered)

Jerome, Chronicon s.a. 284,9 pp. , 23–225, 1: Carus of Narbo, after laying waste to the entire territory of the Parthians (sic), captured Coche and Ctesiphon, the most famous cities of the enemy. After establishing camp on the Tigris, he was killed by a bolt of lightning.

(Dodgeon)

Ammianus Marcellinus XXIV, 5, 3: (AD 363) This district is rich and well cultivated: not far off is Coche, which is called Seleucia;… The emperor (i.e. Julian) himself in the meanwhile proceeded with his advanced guard and reconnoitred a deserted city which had been formerly destroyed by the Emperor Carus, where an everflowing spring forms a great pool which joins onto the Tigris.

(Yonge, pp. 364–5, revised.)

SHA Carus 7, 1 and 8, 1–9, 1: And so—not to include what is of little importance or what can be found in other writers— as soon as he (i.e. Carus) received the imperial power by the unanimous wish of all the soldiers, he took up the war against the Persians for which Probus had been preparing….

8 With a vast array and all the forces of Probus, he set out against the Persians after finishing the greater part of the Sarmatian war, in which he had been engaged, and without opposition he conquered Mesopotamia and advanced as far as Ctesiphon; and while the Persians were busied with internal strife he won the name of Conqueror of Persia.10 2. But when he advanced still further, desirous himself of glory and urged on most of all by his prefect, who in his wish to rule was seeking the destruction of both Carus and his sons as well, he met his death, according to some, by disease, according to others, through a stroke of lightning. 3. Indeed, it cannot be denied that at the time of his death there suddenly occurred such violent thunder that many, it is said, died of sheer fright. And so, while he was ill and lying in his tent, there came up a mighty storm with terrible lightning, and, as I have said, still more terrible thunder, and during this he expired. 4. Julius Calpurnius, who used to dictate for the imperial memoranda, wrote the following letter about Carus’ death to the prefect of the city, saying among other things:

5. ‘When Carus, our prince for whom we truly care, was lying ill, there suddenly arose a storm of such violence that all things grew black and none could recognize another; then continuous flashes of lightning and peals of thunder, like bolts from a fiery sky, took from us all the power of knowing what truly befell. 6. For suddenly, after an especially violent peal which had terrified all, it was shouted out that the emperor was dead. 7. It came to pass, in addition, that the chamberlains, grieving for the death of their prince, fired his tent; and the rumour arose, whatever its source, that he had been killed by the lightning, whereas, as far as we can tell, it seems sure that he died of his illness.’

9 This letter I have inserted for the reason that many declare that there is a certain decree of fate that no Roman emperor may advance beyond Ctesiphon, and that Carus was struck by lightning because he desired to pass beyond the bounds which Fate has set up. 2. But let cowardice, on which courage should set its heel, keep its devices for itself.

(Magie, iii, pp. 429–31)

Epitome de Caesaribus 38, 1: Carus, born in Narbo, ruled for two years. He immediately made Carinus and Numerianus Caesars. He was killed near Ctesiphon by a bolt of lightning.

(Dodgeon)

Orosius, adversus paganos VII, 24, 4: When he (i.e. Carus) had made his sons, Carinus and Numerianus, colleagues in his rule and after he had captured two very famous cities, Coche and Ctesiphon, in a war against the Parthians (sic), in a camp upon the Tigris he was struck by lightning and killed.

(Deferrari, p. 320)

Sidonius Apollinaris, Carmina XXIII, 91–6, ed. Loyen, i, pp. 14711: Who indeed could forget the Persian campaign and the victorious army of the Emperor Carus and Niphates12 traversed by Roman legions, when the emperor was struck down by lightning, ending a life which was like lightning itself?

(Lieu)

Jordanes, Historia Romana 294, p. , 6–9: Carus, who reigned with his sons Carinus13 and Numerianus, was a native of Gallia Narbonensis. In an admirable fashion he occupied Coche and Ctesiphon, the most noble cities of the Persians, after nearly the whole of Persia had been devastated…. This same Carus, while laying out camp on (the banks of the) Tigris river, was struck down by a bolt of lightning.

(Dodgeon)

Malalas, XII, pp. , 20–303, 4: He (i.e. Carus) campaigned against the Persians, and in his invasion he occupied the districts of Persia as far as the city of Ctesiphon, and made his retreat. On the frontier (limes) he built a fortress, which he made into a city and granted it the rights of citizenship, which he called Caras (= Carrhae?)14 after his own name. After returning to Rome, he went out against the Huns in another war,15 and was slain in the consulship of Maximus and Januarius. He was aged sixty and a half years.

(Dodgeon)

Syncellus, p. 472, 11–12, (p. 724, 11–16, CSHB): And, making war on the Persians, he (i.e. Carus) captured Ctesiphon. While he was encamped by the river Tigris, he was killed in his tent by a sudden bolt of lightning.

(Dodgeon)

Cedrenus, i, p. 464, 6–9: Carus and Carinus and Numerianus reigned for two years. This Carus occupied Persia and Ctesiphon: this is the fourth time that this city had suffered the same fate. (It had been captured before) by Trajan, by Verus, by Severus and by Carus. Carus was killed by plague,…

(Dodgeon)

Zonaras, XII, 30, pp. 610, 20–612, 16 (iii, pp. 156, 10–157, 2, Dindorf): When Carus gained the emperorship, he crowned his sons Carinus and Numerianus with the imperial diadem. And presently he campaigned against the Persians with one of his sons, Numerianus, and he gained Ctesiphon and Seleucia. But the Roman army almost came into dire peril; for they encamped in a hollow. The Persians saw this and through a canal led into that hollow the river which at that point flowed nearby. But Carus was successful in attacking the Persians and put them to flight. And he returned to Rome with a multitude of prisoners and much plunder. Then when the Sarmatian nation rose in revolt he joined battle with them and defeated them and brought their nation under his control. By race he was a Gaul, brave and adept in warfare. But there is no agreed version of his death among our records. For some say that he campaigned against the Huns and was killed there, while others say that he was encamped by the river Tigris, and that there his army had formed an entrenched camp. His tent was hit by a thunderbolt and they relate that he perished in it.

(Dodgeon)

5.2.1.

Conflicting accounts of the achievements of Numerianus16 and Carinus, the sons of Carus

Nemesianus, Cynegetica 63–75: Soon, bravest sons of the divine Carus, I shall prepare to relate your triumphs to the accompaniment of a better lyre, and I shall sing of the [empire’s] shore by the twin limits of the world and the nations subdued by the power of the brother [emperors], which drink the Rhine and Tigris and drink the far-removed first waters of the Saône and the source of the Nile at its earliest point. I would not keep silence at the beginning, Carinus, about the wars which with successful hand you have recently completed in the North—you almost surpass your divine father— and how your brother captured the innermost regions of Persis and the ancient citadels of Babylon, avenging the outraged extremities of Romulus’ kingdom. And I shall recount the spiritless flight and fastened quivers of the Parthians and their unstrung bows and lack of arrows.

(Dodgeon)

Aurelius Victor, liber de Caesaribus 38, 6–39, 1: Upon the death of his father, Numerianus, thinking that the war was at an end, was returning with the army when he perished through the treachery of Aper, his father-in-law and Praetorian Prefect. 7. In this an opportunity was offered by a disease of the eye which afflicted the young man. 8. For the crime remained undetected for a long time because the corpse was transported in a closed litter, as if the passenger was ill, in order that his vision would not be inconvenienced by the cold draughts.

39 However, after the crime had been revealed by the unpleasant odour of the decomposing corpse, at the advice of the generals and tribunes, Valerius Diocletian who commanded the imperial guards was chosen emperor, for his sagacity:…

(Dodgeon)

SHA Carus 12, 1–13, 1: He (i.e. Numerianus) accompanied his father in the Persian war, and after his father’s death, when he had begun to suffer from a disease of the eyes—for that kind of ailment is most frequent with those exhausted, as he was, by too much loss of sleep—and was being carried in a litter, he was slain by the treachery of his father-in-law Aper, who was attempting to seize the rule. 2. But the soldiers continued for several days to ask after the emperor’s health, and Aper kept haranguing them, saying that he could not appear before them for the reason that he must protect his weakened eyes from the wind and the sun, but at last the stench of his body revealed the facts. They all fell upon Aper, whose treachery could no longer be hidden, and they dragged him before the standards in front of the general’s tent. Then a huge assembly was held and a tribunal, too, was constructed. 13 And when the question was asked who would be the most lawful avenger of Numerian and who could be given to the commonwealth as a good emperor, then all, with a heaven- sent unanimity, conferred the title of Augustus on Diocletian, who, it was said, had already received many omens of future rule.

(Magie, iii, p. 435)

Epitome de Caesaribus 38, 4–5: Numerianus, his son, who suffered from an eye ailment and was carried in a litter, was killed in a conspiracy instigated by Aper, his father-in-law. 5. As long as his death was concealed by trickery, Aper was able to seize power but his death was revealed by the stench of the corpse.

(Dodgeon)

Malalas, XII, pp. , 5–305, 2: After the reign of Carus, Numerianus Augustus ruled for two years…. In his reign there occurred a great persecution of Christians; among them were martyred St. George the Cappadocian and St. Babylas. The latter was bishop of Antioch the Great. The same emperor Numerianus arrived [there] when on his way to war against the Persians. Wishing to view the divine mysteries of the Christians, he desired to enter the holy church where the Christians were gathered, to observe what mysteries they were celebrating. For he had heard that the same Galilaeans secretly performed their services. And as he drew near he was suddenly confronted by St. Babylas.17 And the bishop stopped him, saying to him, ‘You are polluted from sacrifice to idols; and I do not assent to your seeing the mysteries of the living God.’ The emperor Numerianus was angry with him and immediately executed him. He went out from Antioch and campaigned against the Persians. In the ensuing battle, the Persians launched an attack on him [p. 304] and destroyed the greater part of his forces, and he fled to the city of Carrhae. The Persians put it under siege and took him prisoner, and immediately they executed him. They flayed his skin and made it into a bag. They treated it with myrrh and preserved it for their particular glory. They cut down the remainder of his army. On his death the emperor Numerianus was thirty-six…. As soon as Carinus became emperor, he campaigned against the Persians to avenge his own brother Numerianus and he overwhelmed them by force.18

(Dodgeon)

Chronicon Paschale, p. 510, 2–15: In the year 255 after our Lord’s Ascension into heaven, there occurred a persecution of Christians and many were martyred. Among the martyrs were St. George and St. Babylas. This latter was bishop of Antioch the Great, and the emperor Carinus, on his way with his uncle Carus to wage war upon the Persians, arrived there. Carus was struck by a thunderbolt in Mesopotamia. Carinus suffered defeat and fled to the city of Carrhae. The Persians encamped nearby and took him prisoner, and they immediately killed him. They flayed him and made his skin into a sack. And they treated it with myrrh [to preserve it] and kept it as an object of exceptional splendour. This Carinus died at the age of thirty-six. After his death his brother Numerianus campaigned against the Persians to avenge his own brother Carinus and he overcame them in mighty fashion.

(Dodgeon)

Syncellus, p. 472, 14–20 (pp. 724, 16–725, 5, CSHB): After him his son Numerianus reigned for only 30 days. For on his return from Persia he suffered an infection of the eyes and was slain by his own father-in-law, called Aper, being the Praetorian Prefect and zealous to become emperor. But his hopes were frustrated, for the whole army proclaimed as emperor Diocletian, who had campaigned with Carus. Diocletian had then displayed great courage and was a Dalmatian by birth. He had reached senatorial rank and had been honoured with the consulship.

(Dodgeon)

Cedrenus, i, p. 464, 9–12:…and Numerianus, who had been blinded, was murdered by Aper, his father-in-law, and Numerianus who was dux of Moesia became emperor. Saint Babylas suffered martyrdom under him in Antioch. This (other) Numerianus was put to death by Diocletian.

(Dodgeon)

Zonaras, XII, 30, pp. 611, 15–612, 2 (iii, p. 157, 3–17, Dindorf): Whether his life ended in this fashion or otherwise, his son Numerianus was left sole emperor19 in the camp. He immediately campaigned against the Persians; and when battle was joined, the Persians gained the upper hand and the Romans fell into retreat. Some relate that he was captured while trying to escape and that his skin was flayed from his whole body (like a wineskin) and so he perished; but the other tradition is that on his retreat from Persia he fell ill with eye trouble and was assassinated by his own father-in-law, the Praetorian Prefect. This man cast jealous eyes at the throne but however he did not gain it. For the army selected Diocletian as emperor, who was present there at that time and had displayed many deeds of courage in the war against Persia.

(Dodgeon)

5.2.2.

A story associated with the Armenian (Persian?) war of Carus or Carinus

Synesius, de regno20 16, ed. Terzaghi, pp. , 16–38, 8 (=ch. 18, PG 66. 1082B– 1085A): It is therefore worthwhile to make mention of the character and achievements of a certain king, for any particular story will suffice to draw all others along in its wake. It is told of one of no great antiquity but such a one as even the grandfathers of our own elders might have known if they had not begotten their children when young, and had not become grandparents during the youth of their own children. It is said, then, that a certain monarch of those days was leading an expedition against the Parthians, who had behaved towards the Romans in an insulting manner. Now when they had reached the mountain frontiers of Armenia, before entering the enemy country, he was eager to dine, and gave orders to the army to make use of the provisions in the supply column, as they were now in a position to live off the neighbouring country should it be necessary. He was then pointing out to them the land of the Parthians. Now, while they were so engaged, an embassy appeared from the enemy lines, thinking on their arrival to have the first conversation with the influential men who surrounded the king, and after these with some dependants and gentlemen ushers, but supposing that only on a much later day would the king himself give audience to the embassy. However, it turned out somehow that the king was dining at the moment. Such a thing did not exist at that time as the Guards’ regiment, a sort of picked force detached from the army itself, of men all young, tall, fair-haired and superb,

‘Their heads ever anointed and their faces fair’ (Odyssey, XV. 332), equipped with golden shields and golden lances. At the sight of these we are made aware beforehand of the king’s approach, much as, I imagine, we recognize the sun by the rays that rise above the horizon. Here, in contrast, every phalanx doing its duty, was the guard of the king and the kingdom. And these kings held themselves in simple fashion, for they were kings not in pomp but in spirit, and it was only within that they differed from their people. Externally they appeared in the likeness of the herd, and it was in such guise, they say, that Carinus was seen by the embassy. A tunic dyed with purple was lying on the grass, and for repast he had a soup of yesterday’s peas, and in it some bits of salted pork that had grown old in the service.

Now when he saw them, according to the story, he did not spring up, nor did he change anything; but called out to these men from the very spot and said that he knew that they had come to see him, for that he was Carinus;21 and he bade them tell the young king that very day, that unless he conducted himself wisely, he might expect that the whole of their forest and plain would be in a single month barer than the head of Carinus. And as he spoke, they say that he took off his cap, and showed his head, which was no more hairy than the helmet lying at his side. And he gave them leave if they were hungry to attack the stew-pot with him, but if not in need, he ordered them to depart at once, and to leave the Roman lines, as their mission was at an end. Now it is said that when these messages were reported to the rank and file and to the leader of the enemy, namely, all that had been seen and heard, at once—as might have been expected —shuddering and fear fell upon every one at the thought of fighting men such as these, whose very king was neither ashamed of being a king, nor of being bald, and who, offering them a stew-pot, invited them to share his meal. And their braggart king arrived in a state of terror and was ready to yield in everything, he of the tiara and robes, to one in a simple woollen tunic and cap.

(Fitzgerald, i, pp. 128, 15–130, 8)

5.2.3.

Diocletian's truce with the Persians

Panegyrici Latini II/10, 7, 5–6: In my view,22 the Euphrates in like manner held the rich and fertile land of Syria in a protective embrace before the Persian Kingdom voluntarily surrendered to Diocletian.23 But he gained this in the fashion of Jupiter his patron through that paternal nod of command which causes everything to tremble, and through the grandeur of your (i.e. Maximianus’) name. 6. You, however, invincible Emperor, have tamed those wild and uncontrollable peoples (i.e. German tribes) through devastation, battles, massacres, the sword and the fire.

Pan. Lat. II/9, 1–2: He (i.e. Diocletian) has recently invaded that part of Germany which lies opposite to Rhaetia and with a courage similar to yours he has victoriously advanced the Roman frontier, so much have you in plain and loving fashion attributed to his divinity what measures you had taken for [the defences of] the territories, when you came together from different parts of the globe and joined together your invincible right hands, so full of trust and brotherly feeling was that conference. 2. In it you provided for yourselves reciprocated examples of all the virtues and in turn you increased your stature, something which did not seem possible, Diocletian by showing to you the gifts of the Persians24 and you by displaying spoils from the Germans.

Pan. Lat. II/10, 6: In this same manner that king of Persia, who had never befor e deigned to admit that he was a mere man,25 was a suppliant before your brother (i.e. Diocletian) and laid open his whole kingdom to him, if he thought it right to enter it. In the meantime he offered him varying wonders, he sent wild animals of remarkable beauty; being content to win the name of friend, he earned it through his submission.

(Dodgeon)

5.2.4.

Return of Trdat to Armenia with Roman military assistance (?) (c. 287)26

Agathangelos, Hist. Arm. (I), 46–7 (Thomson, p. 61): See see Appendix II, pp. .

Moses Khorenats’i, Hist. Arm. (II), 82 (Thomson, pp. 231–2): See Appendix II, p. .

5.2.5.

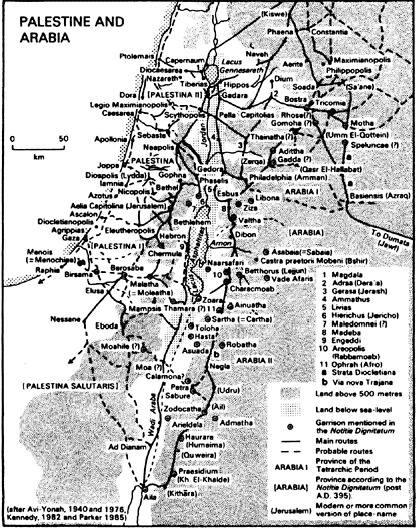

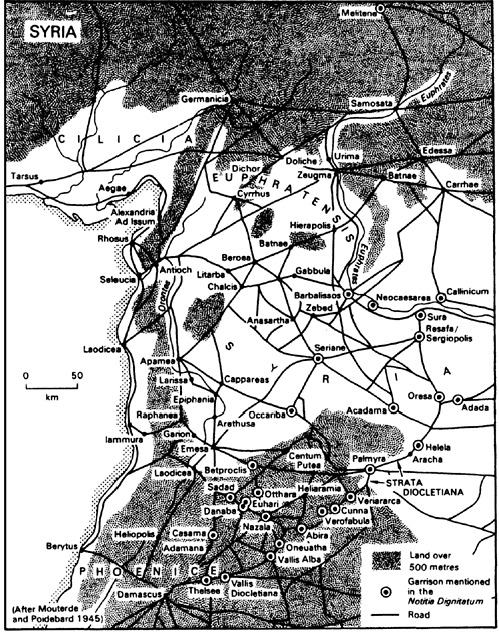

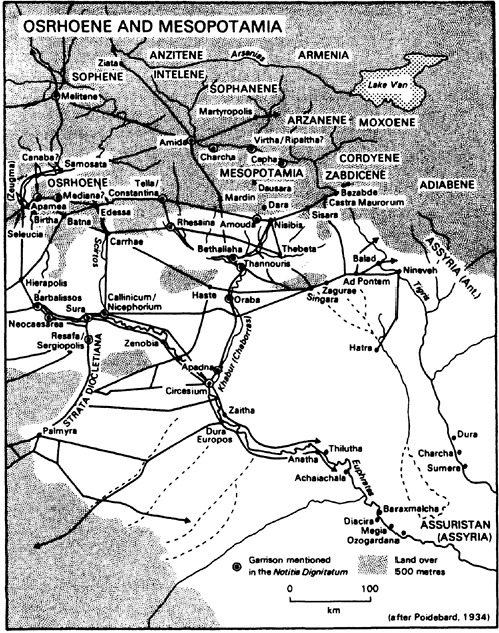

Diocletian fortifies Circesium and reorganizes the eastern frontier (287?)

Ammianus Marcellinus XXIII, 5, 2: The place (i.e. Circesium) had formerly been small and insecure, till Diocletian surrounded it with high towers and walls when he was organizing the frontier defences in depth on the confines of the territories of the barbarians, in order to prevent the Persians from overrunning Syria, as had happened a few years before to the great injury of the province.

(Yonge, p. 325, revised)

Procopius, de bello Persico II, 5, 2–3: (AD 540) On the other side of the river stands the last Roman stronghold which is called Circesium, an exceedingly strong place, since the river Aborras (i.e. the Khabur), a large stream, has its mouth at this point and mingles with the Euphrates, and the fortress lies exactly in the angle which is made by the junction of the two rivers. 3. And a long second wall outside the fortress cuts off the land between the two rivers, and completes the form of a triangle around Circesium.

(Dewing, i, p. 295)

See also texts cited in 5.5.5–5.6.1, pp..

5.3.1.

Diocletian's campaign against the Saracens (? May/June, 290)

Pan. Lat. III/11, 5, 4–5: I27 pass in silence over the Rhaetian border that was advanced by the sudden defeat of the enemy, I omit to mention the devastation of Sarmatia and the Saracens28 beset by the bonds of imprisonment, I pass by also those achievements won by the dread of your weapons as though they were feats of arms, the Franks and their king coming to seek peace and the Parthian (sic) flattering you with the wonder of his gifts. 5. I set before myself a new condition of rhetoric that, when I seem to be silent upon all which is most important, I shall yet reveal that there are other greater glories present in my praises of you.

Ibid. 6, 6: The Rhine, the Danube, and the Nile, and the Tigris with its twin the Euphrates, and the two oceans which receive and return the sun and whatever is between the confines of these lands, rivers and shores, through you are in communion with such affable equanimity as much as the eyes rejoice to be in communion with day(light).

Ibid. 7, 1: That laurel crown of victory (won by Diocletian) over the conquered people neighbouring upon Syria and his victories in Rhaetia and Sarmatia made you, Maximianus, triumph in the joy of devotion.

Pan. Lat. IV 8, 3, 3: Indeed, beyond the Tigris, Parthia [sic] was reduced; Dacia was restored, the frontiers of Germany and Rhaetia stretch as far as the source of the Danube, the liberation of Britain and Batavia is assured,… Pan. Lat. IV 8, 21, 1: In the same way that a short time ago, Emperor Diocletian, at your order Asia had filled the deserted lands of Thrace with colonists (i.e. Saracen captives),…

(Dodgeon)

5.3.2.

The accession of Bahram (III) and his brief reign (293)

Agathias IV, 24, 6–8: But Vararanes (i.e. Bahram) III enjoyed the kingdom for only four months. He was called Segansaa; this was for a special reason, in accordance with an old traditional custom. 7. When the Persian kings defeat in war a large tribe among their neighbours and conquer the country, they no longer kill the conquered people but reduce them all to tributary status and let them live in the captured territory and cultivate it, save that they kill the former leaders of the tribe most cruelly, and give their own sons the title of their kingdom, to commemorate and glorify their pride in their victory. 8. So, since the tribe of the Segestani had been enslaved by Vararanes, the father of this King, his son was naturally called Segansaa (recte Saganshah),29 for this means in Greek ‘the king of the Segestani’.

(Cameron, p. 123)

5.3.3.

The accession of Narses (c. 293)

Agathias IV, 25, 1: This king (i.e. Bahram III) soon perished and Narses was the next to hold the throne, for seven years, five months (i.e. 293–302).30

(Cameron, p. 123)

5.3.4.

Renewal of hostilities by Narses (c. 293).

Lactantius, de mortibus persecutorum 9, 5: Narses, king of the Persians, emulating the example set him by his grandfather (recte father) Shapur, assembled a great army, and aimed at becoming master of the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire.

(Fletcher, p. 304, altered)

Aurelius Victor, liber de Caesaribus 39, 22: At that same time, the Persians gravely vexed the East, and Julianus and the Quinquegentianae31 troubled Africa.

(Dodgeon)

Ammianus Marcellinus XXIII, 5, 11: See below 5.3.5.

Eutropius IX, 22, 1: While disorder thus prevailed throughout the world, while Carausius was taking arms in Britain and Achilleus in Egypt, while the Quinquegentiani were harassing Africa, and Narses was making war upon the east, Diocletian promoted Maximian Herculius from the dignity of Caesar to that of emperor, and created Constantius and Maximian Galerius Caesars, of whom Constantius is said to have been the grand-nephew of Claudius by a daughter and Maximian Galerius to have been born in Dacia not far from Serdica.

(Watson, p. 524)

Jerome, Chronicon s. aa. 289–90,32 p. , 18–25: Carausius, having assumed the purple, occupied Britain. Narses made war on the east. The Quinquegentiani laid waste to Africa. Achilleus occupied Egypt. On account of these (setbacks), Constantius (I) and Galerius Maximianus were added to the sovereignty as Caesars, of whom Constantius is said to have been the grand-nephew of Claudius by a daughter and Galerius was born in Dacia not far from Serdica. [=Jordanes, hist. Rom. 297–8.]

(Dodgeon)

Orosius, adversus paganos VII, 25, 4: Thus, throughout the confines of the Roman Empire, the roars of sudden strife sounded, Carausius leading a rebellion in the British provinces and Achilleus in Egypt, while the Quinquegentiani disturbed Africa, and Narses also, King of the Persians, pressed the east with war; Diocletian, being disturbed by this danger, made Herculius Maximianus Augustus instead of Caesar, and he appointed Constantius and Galerius Maximianus as Caesars.

(Deferrari, p. 320)

5.3.5.

The Persian Campaigns of Diocletian and Galerius (296± 298)

PArgent. 480 (=Reitzenstein, 1901:48, frag. 1),33 recto 1–10: Driven mad by the lashes of Enyo,34 they all girded on their arrow-holding quivers, and each held bow and spear in his hands and the whole Nisaean35 cavalry that fights on the plains was gathered together, not a fraction of the cavalry which Nereus had before brought speeding over the ocean on floating rafts. For not such as shrieked under Thermopylae’s narrow vale at the hands of the Spartans was the Median host coming to meet my emperor, but much more numerous and stung by the battle cry…36

PArgent. 480 verso 2–11 (fragmentary): Other leaders also would have hastened from Italy to his aid, had not war in Spain drawn one and the battle-din of the island of Britain encompassed the other.37 But just as Zeus goes from Crete above Othrys and Apollo (leaves) sea-girt Delos for Pangaeus, and as they don their arms the noisy throng of Giants is set to trembling, in such fashion the elder lord38 with his army of Ausonians (i.e. Romans) reached the Orient in the company of the younger king. They had the likeness of the blessed gods, one in strength matched Zeus on high and the other the fair-haired Apollo…

(Dodgeon)

Lactantius, de mortibus persecutorum 9, 6–8: Diocletian, apt to be low-spirited and timorous in every connotation, and fearing a fate like Valerian’s, would not in person engage Narses; but he sent Galerius by way of Armenia, while he himself halted on the eastern provinces, and anxiously watched the event. 7. It is a custom among the barbarians to take everything that belongs to them into the field. Having put Narses to flight, and returned with much spoil, his own pride and Diocletian’s fears were greatly increased. 8. For after this victory he rose to such a pitch of haughtiness as to reject the appellation of Caesar; and when he heard that appellation in letters addressed to him, he cried out, with a stern look and a terrible voice, ‘How long am I to be Caesar?’

(Fletcher, p. 304, revised)

Julian, Orationes I, 18A–B (13.18–27, Bidez): Among those who sat on the throne before your father’s time and imposed on the Persians conditions of peace admired and welcomed by all, did not the Caesar (i.e. Galerius) incur a disgraceful defeat when he attacked them on his own account? It was not till the ruler of the whole world turned his attention to them, directing thither all the forces of the empire, occupying all the passes with his troops and levies of hoplites, both veterans and new recruits and employing every sort of military equipment, that fear drove them to accept terms of peace.

(Wright, i, pp. 45–7)

Aurelius Victor, liber de Caesaribus 39, 33–6: In the meantime, after Jovius (i.e. Diocletian) had departed for Alexandria, the Caesar Maximianus (i.e. Galerius) received his assignment to cross the borders, and advanced into Mesopotamia in order to stem the tide of the Persian advance. 4. Gravely defeated by them at first, he immediately assembled an army of both veterans and recruits and advanced against the enemy through Armenia; which was almost the only way to victory, or at least the easiest. 35. At length, in that very place he captured the (Persian) king Narses together with his children, his wives and his court. 36. His victory was such that had Valerius (i.e. Diocletian), whose will was law, for whatever reason, not opposed it, the Roman fasces would have been borne into a new province.39

(Dodgeon)

Festus, breviarium 14, pp. , 14–58, 2: In the time of Diocletian, the Romans, vanquished in the first engagement, defeated Narses in the second and captured his wife and his daughters, whom they protected with utmost respect for their honour. After peace had been made, Mesopotamia was restored (to us) and the boundary (limes) re-established beyond the Tigris,40 with the result that we acquired sovereignty of the five states (gentes) established across the Tigris. The terms of this treaty were adhered to until the time of the divine Constantius.

Festus, breviarium 25, pp. , 12–66, 5: Under Emperor Diocletian, a memorable victory was won against the Persians. Maximianus Caesar, in the first engagement, having attacked vigorously an innumerable body of enemies with a handful of men, withdrew defeated, and Diocletian received him with such indignation that he had to run for a few miles before his carriage, garbed in his purple.41 He gained with difficulty his request that his army should be restored to its full complement from the frontier troops of Dacia and that he should attempt another military engagement. Arriving in Greater Armenia, the commander himself, along with two cavalrymen, reconnoitred the enemy. He suddenly came upon the enemy camp with twenty five thousand troops and, attacking the countless columns of the Persians, he cut them down in a massacre. Narses the Persian king fled, while his wife and daughters were protected with the utmost regard for their chastity. In respect of this admirable behaviour, the Persians admitted the superiority of the Romans not only in warfare but even in character. They restored Mesopotamia with the Transtigritanian regions. The peace that was made endured until our time and was advantageous to Rome.

(Dodgeon)

Eutropius, IX, 24–5, 1: Galerius Maximianus in acting against Narses fought, on the first occasion, a battle far from successful, meeting him between Callinicum and Carrhae,42 and engaging in the combat rather with rashness than want of courage; for he contended with a small army against a very numerous enemy. Being in consequence defeated, and going to join Diocletian, he was received by him, when he met him on the road, with such extreme haughtiness, that he is said to have run by his chariot for several miles in his scarlet robes.

25 But having soon after collected forces in Illyricum and Moesia, he fought a second time with Narses (the grandfather of Hormisdas and Sapor), in Greater Armenia, with extraordinary success, and with no less caution and spirit, for he undertook, with one or two of the cavalry, the office of a speculator. After putting Narses to flight, he captured his wives, sisters, and children, with a vast number of the Persian nobility besides, and a great quantity of treasure; the king himself he forced to take refuge in the remotest deserts in his dominions. Returning therefore in triumph to Diocletian, who was then encamped with some troops in Mesopotamia, he was welcomed by him with great honour.

(Watson, pp. 525–6)

Jerome, Chronicon s. a. 302, p. , 12–14: Galerius Maximianus was received with the greatest honour by Diocletian, after he had defeated Narses and captured his wives, children and sisters.

Ibid. s. a. 304, pp. , 25–228, 2: The Augustus Diocletian and Maximianus celebrated a triumph at Rome with signal pomp, with the wife and sisters and children of Narses preceding the carriage and all the booty plundered from Persia.

(Dodgeon)

Ammianus Marcellinus XIV, 11, 10: (AD 354) To these exhortations, he (sc. Constantius) added by way of precedent an incident from the not too distant past that Diocletian and his colleague (i.e. Maximianus) employed their Caesars as attendants with no fixed abode, dispatching them hither and thither. On one occasion in Syria, (the Caesar) Galerius, clad in purple, had to march on foot for nearly a mile before the carriage of an enraged Augustus (sc. Diocletian).

(Yonge)

Ibid. XXII, 4, 8: For it is well known that when, in the time of the Caesar Maximianus, the camp of the king of Persia was plundered, a common soldier, after finding a Parthian jewel-case full of pearls, threw the gems away in ignorance of their value, and went away content with the mere beauty of his bit of leather.

(Yonge, p. 282, revised)

Ibid. XXIII, 5, 11: (AD 363) In truth, they (i.e. Julian’s philosopher theurgist friends) brought forward as a plausible argument to secure credit to their knowledge, that in time past, when Caesar Maximianus was about to fight Narses, king of the Persians, a lion and a huge boar which had been slain were at the same time brought to him, and after subduing that nation he returned in safety; forgetting that the destruction which was now portended was to him who invaded the dominions of another, and that Narses had given the offence by being the first to make an inroad into Armenia, a country under Roman jurisdiction.

(Yonge, pp. 326–7)

SHA, Car. 9, 3: For clearly it is granted to us and will always be granted, as our most venerated Caesar Maximianus has shown, to conquer the Persians and advance beyond them, and methinks this will surely come to pass if only our men fail not to live up to the promised favour of Heaven.

(Magie, iii, p. 431)

Synesius, de regno 17 (=ch. 13, PG 66.1085A): And another story more recent than this I think you must have heard, for it is improbable that anyone has ever heard of a king who assigned himself the task of getting into the enemy’s country for purposes of espionage by imitating the appearance of an embassy.

(Fitzgerald, i, p. 130, 9–13)

Orosius, adversus paganos VII, 25, 9–11: Besides, Galerius Maximianus, after he had fought Narses in two battles, in a third battle somewhere between Callinicum and Carrhae, met Narses and was conquered, and after losing his troops fled to Diocletian. He was received by him very arrogantly, so that he is reported, though clad in purple, to have been made to run before his carriage, but he used this insult as whetstone to valour, as a result of which, after the rust of royal pride had rubbed off, he developed a sharpness of mind. Thus he brought troops together from all sides throughout Illyricum and Moesia and, hurriedly turning against the enemy, he overcame Narses by his great strategy and forces. With the Persian troops annihilated and Narses himself turned to flight, he entered Narses’ camp, captured his wives, sisters, and children, seized an immense amount of Persian treasure, and led away a great many Persian noblemen. Returning to Mesopotamia, he was received by Diocletian with the highest honour.

(Deferrari, pp. 321–2)

Chronicon Paschale, p. 512, 18–19: The Persians were utterly defeated by Constantius and Maximianus Jovius.

Chronicon Paschale. p. 513, 19–20: Under the same consuls, the Persians were defeated by Maximianus Herculius Augustus.

(Dodgeon)

Jordanes, Getica, XXI (110), p. , 13–19: After these events (the sacking of Troy in Asia Minor), the Goths43 had already returned home when they were summoned at the request of the Emperor Maximian to aid the Romans against the Parthians. They fought for him faithfully, serving as auxiliaries. But after Caesar Maximian by their aid had routed Narses, king of the Persians, the grandson44 of Shapur the Great, taking as spoil all his possessions, together with his wives and sons, and when Diocletian had conquered Achilles in Alexandria and Maximianus Herculius had broken the Quinquegentiani in Africa, thus winning peace for the Empire, they began rather to neglect the Goths.

(Mierow, p. 82)

Malalas, XIII, p. . 16–21: When the Persians again stirred up trouble, Diocletian took up arms and campaigned against them with Maximianus.45 When they reached Antioch the Great, the same Diocletian sent Maximianus Caesar against the Persians and waited himself in Antioch.

Malalas, p. , 6–15: Maximianus Caesar went away against the Persians, defeated them by force and returned to Antioch. He took prisoner the Persian king’s wife, after he had fled with four men to the limes of India and their army had been destroyed. Arsane, the queen of the Persians, resided in Daphne for some years and was guarded with honour by command of the Roman emperor Diocletian. After this there was a peace treaty and she was returned to the Persians to her own husband, having endured an honourable captivity. At this time donatives were offered by the emperor to the whole Roman state to celebrate the victory.

(Dodgeon)

Theophanes, Chronicon, A.M. 5793, p. , 1–15: In this year Maximianus Galerius was dispatched by Diocletian against Narses, the king of Persia, who at that time had overrun Syria and was ravaging it. Meeting him (i.e. Narses) in battle, he (i.e. Galerius) lost the first encounter in the area of Callinicum and Carrhae. While withdrawing from battle, he met Diocletian riding in a chariot. He did not welcome the Caesar (accompanied as he was by his own show of pomp) and left him alone to run along for a considerable distance and precede his chariot. After this the Caesar Maximianus Galerius gathered a great force and was sent again to the war with Narses. He met with success, venturing and

achieving what no one else could have done. For he both pursued Narses into the interior of Persia and slaughtered all his camp and his wives, children and sisters, and he took over all that the Persian king had brought with him, a treasure store of money and the nobility of the Persians. When he returned with these, Diocletian, then residing in Mesopotamia, greeted him gladly and honoured him. And each on his own and both together made war on many of the barbarians and won many successes. Diocletian was puffed up with the success of his fortunes and sought to have obeisance made to him by his senators and not be addressed according to the former style. He adorned his footwear with gold, pearls and precious stones.

(Dodgeon)

Eutychius, Annales 187, ed. Breydey, p. , 1–5: See below, Appendix I, p. .

Zonaras, XII, 31, pp. 616, 4–617, 4 (iii, pp. 161, 10–162, 4, Dindorf): When Narses was king of Persia, who is recorded as the seventh (corr.: sixth) King of Persia after Ardashir, whom our historical account mentioned earlier as having restored the kingdom of the Persians—for after this Artaxerxes or Artaxares, there being two forms of the name (i.e. Ardashir,) Shapur became king of Persia, after him came Hormizd, then Varanes (i.e. Bahram I), and after him Vararakh, and again another Varanes (i.e. Bahram II), and besides these came Narses— while this Narses was then ravaging Syria, Diocletian, while passing through Egypt against the Ethiopians, sent his own son-in-law Galerius Maximianus with sufficient strength to fight with him. He clashed with the Persians, was defeated and fled. But Diocletian sent him once more with a larger army. So, fighting with them again, he was so successful that he redeemed his earlier defeat. For he destroyed most of the Persian army and pursued the wounded Narses as far as the interior of Persia. He led away as prisoners his wives, sons and sisters, and he gained possession of all the money that Narses brought with him on the campaign and (possession also) of many of the Persian nobility. When Narses had recovered from his wound, he sent embassies to Diocletian and Galerius, asking that his children and wives be given back to him and that a peace treaty be made. And he gained his request, giving up to the Romans whatever territory they wanted.

(Dodgeon)

5.4.1.

Assuristan raided by Armenians(?)

Agathangelos, Hist. Arm. (I), 123: (Thomson, pp. 135–6): See Appendix II, p. .

5.4.2.

Negotiations between Galerius and the envoy of Narses

Petrus Patricius, frag. 13, FGH IV, pp.: Apharban, who was particularly dear to Narses, king of Persia, was sent on an embassy and came before Galerius in supplication. When he had received licence to speak, he said, ‘It is clear to the race of men that the Roman and Persian Empires are, as it were, two lamps; as with (two) eyes, each one should be adorned by the brightness of the other and not for ever be angry seeking the destruction of each other. For this is not considered virtue but rather levity or weakness. Because men think that later generations cannot help them, they are eager to destroy those who are opposed to them. However, it should not be thought that Narses is weaker than all the other kings; rather that Galerius so surpasses all other kings that to him alone does Narses himself justly yield and yet does not become lower than his forebears’ worth’. In addition to this, Apharban said that he had been commanded by Narses to entrust the rights of his Empire to the clemency of the Romans, since they were reasonable. For that reason he did not bring the terms (lit. oaths) on which the treaty would be based, but gave it all to the judgement of the Emperor. He (Narses) only begged that just (his) children and wives be returned to him, saying that through their return he would remain bound by acts of kindness rather than by arms. He could not give adequate thanks that those in captivity had not experienced any outrage there, but had been treated in such a way as if they would soon be returned to their own rank. With this he brought to memory the changeable nature of human affairs.

Galerius seemed to grow angry at this, shaking his body. In reply he said that he did not deem the Persians very worthy to remind others of the variation in human affairs, since they themselves, when they got the opportunity, did not cease to impose misfortunes on men. ‘Indeed you observed the rule of victory towards Valerian in a fine way, you who deceived him through stratagems and took him, and did not release him until his extreme old age and dishonourable death. Then, after his death, by some loathsome art you preserved his skin and brought an immortal outrage to the mortal body.’ The Emperor went through these things and said that he was not moved by what the Persians suggested through the embassy, that one ought to consider human fortunes; indeed it was more fitting to be moved to anger on this account, if one took notice of what the Persians had done. However, he followed the footsteps of his own forebears, whose custom it was to spare subjects but to wage war against those who opposed them—then he instructed the ambassador to make known to his own king the nobility and goodness of the Romans whose kindness he had put to the test, and that he should hope also that before long, by the resolve of the Emperor, they (i.e. the captives) would return to him.

(J.M.Lieu)

5.4.3.

The peace settlement between Diocletian and Narses (298 or 299)

Petrus Patricius, frag. 14, FGH IV, p. : Galerius and Diocletian met at Nisibis, where they took counsel and by common consent sent an ambassador to Persia, Sicorius Probus, an archival clerk. Narses received him cordially because of the hope inspired by the proclamation he made. Narses also contrived some delay. As if he wanted the envoys who came with Sicorius to recover from their weariness, he took Sicorius, who was not ignorant of what was happening, as far as near the Asproudas, a river of Media, until those who had been scattered around because of the war had assembled. Then, in the inner room of the palace, when he had sent out everyone else and required only the presence of Apharban as well as Archapet46 and Bar(a)sabor, of whom the one was praetorian prefect and the other was chief secretary,47 he ordered Probus to give an account of his embassy. The principal points of the embassy were these: that in the eastern region the Romans should have Intelene along with Sophene, and Arzanene along with Cordyene and Zabdicene,48 that the river Tigris should be the boundary between each state,49 that the fortress Zintha,50 which lies on the border of Media, should mark the edge of Armenia, that the king of Iberia should pay to the Romans the insignia of his kingdom and that the city of Nisibis, which lies on the Tigris, should be the place for transactions.51

Narses heard these things and since the present fortune did not allow him to refuse any of them, he agreed to them all, except, in order not to seem to do everything under constraint, he refused only that Nisibis should be the place of transactions. Sicorius, however, said, ‘This point must be yielded. Moreover, the embassy has no power of its own and has received no instructions on this point from the emperors.’ Therefore, when these things were agreed on, his wives and children were returned to Narses, for through the emperor’s love of honour, pure discretion had been maintained towards them.

(J.M.Lieu)

Johannes Lydus, de magistratibus II, 25: And who, then, at first was designated magister, I am not able to say because history is silent; for prior to Martinianus, who was magister under Licinius, history does not hand down this designation for anyone else. Though he was such under Licinius, when Constantine had gotten possession by himself of the entire power of the imperial office, he appointed Palladius magister of the court, a man who was sagacious and through an embassy had earlier reconciled the Persians with the Romans and Galerius Maximianus.

(Bandy, p. 121)

5.4.4.

Participation of Constantine (the Great) in the expedition of Galerius(?)

Constantine, oratio ad sanctorum coetum 16, 2, GCS, p. , 1–3: Memphis and Babylon [it was declared] shall be wasted and left desolate with their fathers’ gods. Now these things I speak not from the report of others, but having myself been present and actually witnessed the pitiful fate of these cities.52

(Richardson, p. 573, revised)

5.4.5.

The achievements of Verinus in Armenia recalled by Symmachus

Symmachus, epistulae I, 2, 7: Should I admire even more your valour in arms, Verinus, you who as commander (dux) have tamed the eastern Armenians53 by the sword or rather your eloquence, the uprightness of your manner of life, and, because, save when in office, for public duty often called on you, you have led your life happily in innocent fields? There is no further need of virtue, for such as there might be, you would have.

5.5.1.

The triumph of Diocletian and Galerius at Rome (c. 298)

Chronicon a. 354, p. , 26–8, MGH: Diocletian and Maximian: (They brought to Rome) a king of the Persians with all his people and placed their garments adorned with pearls to the number of thirty-three about the temples of their lord. Thirteen elephants and six charioteers and two hundred and fifty horses were paraded in the city.

(Lieu)

5.5.2.

The victories of Diocletian and Galerius as recalled by Eumenius54

Panegyrici Latini V/9, 21, 1–3: May this map, thanks to the indication of the opposing regions, permit them to pass in review the magnificent exploits of our valiant princes, by showing them, as the runners arrive in relay every moment, sweat-covered and announcing victories, the twin rivers of Persia, the Libyan fields devoured by drought, the curve of the branches of the Rhine, the many mouths of the Nile, and inviting them, through the sight of each of these countries, to imagine either Egypt, cured of her madness and calm under your kindly rule, Diocletian Augustus, or else you, invincible Maximianus, hurling a thunderbolt on the crushed Moors, or even, thanks to your strong arm, Emperor Constantius (i.e. Constantine Chlorus), Batavia and Brittany lifting their stained heads above forests and waves, or you, Maximianus Caesar (i.e. Galerius), trampling the bows and quivers of the Persians beneath your feet. For now we are pleased to look upon the map of the world, now that finally we no longer see a foreign country!

(Vince)

5.5.3.

Manichaeans accused of being a pro-Persian fifth-column (c. 302)55

Collatio Mosaicarum XV, 3: Gregorian, in the Seventh Book, under the title ‘Of Sorcerers and Manichaeans’:56

The Emperors Diocletian and Maximianus [and Constantius] and Maximianus (i.e. Galerius) to Julianus, Proconsul of Africa: Well-beloved Julianus:

1. Excessive leisure sometimes incites ill-conditioned people to transgress the limits of nature, and persuades them to introduce empty and scandalous kinds of superstitious doctrine, so that many others are lured on to acknowledge the authority of their erroneous notions.

2. But the immortal Gods, in their Providence, have thought fit to ordain that the principles of virtue and truth should, by the counsel and deliberations of many good, great and wise men, be approved and established in their integrity. These principles it is not right to oppose or resist, nor ought the ancient religion to be subjected to the censure of a new creed. It is indeed highly criminal to discuss doctrines once and for all settled and defined by our forefathers, and which have their recognized place and course in our system. 3. Wherefore we are resolutely determined to punish the stubborn depravity of these worthless people.

4. As regards the Manichaeans, concerning whom Your Carefulness have reported to Our Serenity, who, in opposition to the older creeds, set up new and unheard-of sects, purposing in their wickedness, to cast out the doctrines vouchsafed to us by Divine favour in olden times, we have heard that they have but recently advanced or sprung forth, like strange and monstrous portents, from their native homes among the Persians—a nation hostile to us57—and have settled in this part of the world, where they are perpetrating many evil deeds, disturbing the tranquillity of the peoples and causing the gravest injuries to the civic communities and there is danger that, in process of time, they will endeavour, as is their usual practice, to infect the innocent, orderly and tranquil Roman people, as well as the whole of our Empire, with the damnable customs and perverse laws of the Persians as with the poison of a malignant serpent. 5. And since all that Your Prudence has set out in detail in your report of their region shows that what our laws regard as their misdeeds are clearly the offspring of a fantastic and lying imagination, we have appointed due and fitting punishments for these people.

6. We order that the authors and leaders58 of these sects be subjected to severe punishment, and, together with their abominable writings, burnt in the flames. We direct that their followers, if they continue recalcitrant, shall suffer capital punishment, and their goods be forfeited to the Imperial treasury. 7. And if those who have gone over to that hitherto unheard-of, scandalous and wholly infamous creed, or to that of the Persians, are persons who hold public office, or are of any rank or of superior social status, you will see to it that their estates are confiscated and the offenders sent to the (quarry) at Phaeno or the mines at Proconnesus. 8. And in order that this plague of iniquity shall be completely extirpated from this our most happy age, let Your Devotion hasten to carry out our orders and commands. Given at Alexandria, March 31st.

(Hyamson, pp. 131–3, revised)

5.5.4. The accession of Hormizd II (302)

Agathias IV, 25, 1: His (i.e. Narses’) son Hormizd succeeded him, and inherited not only his father’s kingdom but also the length of his reign. It is a surprising fact that each of them reigned for exactly the same number of years and months (302–309).

(Cameron, p. 123)

5.5.5.

General efforts by Diocletian to strengthen the eastern frontier (287ff.)59

CIL III Suppl. I, 6661 (=Inv. VI, 2; Latin inscription found at the so-called Camp of Diocletian at Palmyra):60 Restorers of the world of whom they are the masters, and leaders of the human race, our lords Diocletian (and Maximianus), Unconquered Emperors, and Constantine and Maximianus, noblest Caesars, have established this entrenchment under favourable auspices, through the care of the most perfect Sossianus Hierocles, governor of the province, devoted to their genius and their majesty.

(Vince)

CIL III, 14397 (=IGLS 2675; Latin milestone?, found in a field near Tell Nebi Mindo on the east side of the road to Homs, c. 300): To the Emperor, Caesar, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, the Unconquered, Augustus, and to the emperor, Caesar, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus, the Devout, the Fortunate, the Unconquered, Augustus, and to Flavius Valerius Constantius, and to Galerius Valerius Maximianus, most noble of Caesars…

(Prentice, 1908:274–5, no. 346)

Poidebard, 1934:75 (Latin milestone found between Palmyra and Hlehle): To our Lord, the most noble Constantine and his family. The Strata Diocletiana.61 From Palmyra to Aracha, eight (Roman) miles.

(Lieu)

Mouterde, MUSJ 15 (1930–31) p. (Latin milestone between Haneybe and Manquoura, c. 308/9): Strata. To our lords Galerius Maximianus and Valerius Licinnianus [Licinnius], invincible Augustus and to Galerius Valerius [Maximianus…].

(Lieu)

Speidel, Historia 36 (1987), pp. (Milestone once on the Roman road to Jawf (Dumata)62 found at or near Qasr al Azraq (Basiensis), Latin): [Diocletian… had built(?)…] by his very brave soldiers of the legions XI Claudia, and VII Claudia and I Italica and IV Flavia, and I Illyricorum, linked by manned posts (praetensione colligata)63 to his soldiers from the base of legio III Cyrenaica. From Bostra to Basienis (?) sixty-six miles, from Basienis to Amat(a) 70 (?) and from Amata to Dumata two hundred and eight miles.

(Speidel, 1987:216)

CIL III, 14149 (=Brunnow—v. Domaszewski, 1905:56, lintel inscription found in situ at the Roman castellum at Qasr Bshir in the central sector of the limes Arabicus, AD 306, Latin): To our best and greatest leaders (principibus) Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletian, Pious, Fortunate, Unconquered, Augustus and Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus, Pious, Fortunate, Unconquered, Augustus, and Flavius Valerius Constantius and Galerius Valerius Maximianus, noble caesars. Aurelius Asclepiades, the praeses of the Provincia Arabiae commanded the fortress of the headquarters at Mobene(?) (castra praetorii Mobeni)64 to be fully constructed from the foundations.

(Lieu)

Procopius, de bello Persico II, 1, 6: (c. AD 535) Now this country, which at that time was claimed by both tribes of Saracens,65 is called Strata, and extends to the south of the city of Palmyra; nowhere does it produce a single tree or any of the useful growth of cornlands, for it is burned exceedingly dry by the sun, but from of old it has been devoted to the pasturage of some few flocks. Now Arethas maintained that the place belonged to the Romans, proving his assertion by the name which has long been applied to it by all (for strata signifies ‘a paved road’ in the Latin tongue), and he also adduced testimonies of men of the oldest times.

(Dewing, i, p. 263)

Malalas, XII, pp. , 20–308, 1: He (i.e. Diocletian) also established three armament factories for the manufacturing of arms for the army. One factory he established at Edessa in order that the arms could be near at hand (for troops on the frontier). Similarly he established a factory at Damascus, bearing in mind the inroads of the Saracens.66

Malalas, p. ,17–22: The same Diocletian also established along the borders from Egypt to the boundaries of Persia (a series of) camps. He stationed limitanei in them, and appointed duces for the provinces to be stationed to the rear of these camps with a strong force to keep watch. They also raised up boundary posts to the Emperor and to the Caesar on the limes of Syria.

Malalas, p. , 16–20: In his reign (i.e. Diocletian’s) he sent Maxim(ian)us (called also Licinianus) with a great army to guard the districts of the Orient from the Persians and the inroads of the Saracens. For they were lately disturbing the Orient as far as Egypt.

(Dodgeon)

Chronicon Edessenum II, CSCO, 1, pp. 3, 27–4, 2 (Syriac): In the year 614 (AD 303) in the reign of the Emperor Diocletian, the walls of Edessa collapsed for a second time.67

5.6.1.

A wayfarer's appreciation of the improved provisions for travellers in the frontier regions (late 3rd or early 4th C.)

CIL III 6660 (Inscription found within a Roman camp at Khan Il-Abyad on a road from Damascus to Palmyra, south-west of Qaryatein,68 Latin):

A plain that is dry indeed, and hateful enough to wayfarers,

on account of its long wastes and its chances of death close at

hand,

for those whose lot is hunger, than which there is no graver

ill (or: where no graver ill besets)

thou has made, my lord, a camp, adorned with greatest

splendour,

5 O Silvinus, warden of a city of the high-road (limes), most

strong

in its wall and in the protection of our masters revered in all

the world: and thou hast contrived that it abound in water

celestial,

so that it may bear the yoke of Ceres and of Bacchus.

Wherefore, o guest, with joy pursue thy way,

10 and for benefit received sing with praise the doings

of this great-hearted judge who shines in peace and in war.

I pray the gods above that he, taking a step still higher,

may continue to found for our masters such camps, arduous

though they be,

and that he may rejoice in children who add honour to their

father’s deeds.

(Prentice, 1908:282–3)

Map 3 Osrhoene and Mesopotamia