FIG 30. Outlines of small semi-regular fields, probably of Iron-Age origin (‘Celtic fields’), on the hillside below Malham Cove, Yorkshire. April 1974.

THE ROMANS WERE LITERATE, and from this period onwards we have written records to supplement what we can learn about our history from other sources. But those other sources remain important. Written records inevitably reflect the point of view of the writer; and what is seen as important and worth recording at the time may not be so with historical hindsight. Where purely factual information is concerned (e.g. accounts, estate records, birth, death and marriage records) we can always be grateful for written records. Where there is an element of value judgement we have to be cautious. The Roman Empire was as aware of its civilising mission as was the British Empire in its heyday, or the United States now. The Romans were disparaging of ‘barbarians’, just as our grandparents’ generation was disparaging of (and sorry for) the ‘natives’ in our Empire. We should not judge our ancestors of two millennia ago uncritically by the Romans’ view of them.

‘History’ as it is mostly taught comes in neatly packaged compartments: the Roman period, the Dark Ages, the Anglo-Saxon period, the Norman conquest and so on. This is largely the history of ruling elites. Social history and the history of the landscape is a more gradual and continuous process, driven by economic pressures and technological change, and tempered by the natural conservatism of human societies. Major catastrophes like the Black Death and periods of warfare leave their mark, and can trigger or delay change in unforeseen ways, but their effect in the long run is often less than would have been forecast at the time.

In the late summer of 55 BC Julius Caesar mounted a reconnaissance expedition to the south coast of Britain, and a more serious attempt at invasion the following year, but it was not until AD 43 that Claudius initiated the conquest of the southern part of Britain. The southeast was quickly overrun, and within five years the Romans had probably reached the Severn and the Trent. There followed a period of consolidation, punctuated by the rising of the Britons led by Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni, in AD 60. By the early and mid-70s, the Romans had conquered south Wales, and penetrated as far north as York. During his governorship (AD 77–84), Agricola completed the conquest of Wales, and then quickly marched northwards to the Scottish border and the Clyde–Forth valley, culminating in the defeat of the Caledonian army in Perthshire (AD 83). Truly a Blitzkrieg. That was the farthest point the Romans reached, and it is one thing to win battles, and quite another to hold and govern territory. Permanent Roman settlement extended only to Hadrian’s Wall from the Tyne to the Solway, begun in AD 122.

The Romans’ influence upon the British landscape may be compared with Britain’s upon India. The Romans brought roads, planned towns, villas, fen drainage, trade, and peace and prosperity. The Roman occupation may have had little effect on the ordinary countryside, or on everyday life, just as the British Raj brought railways, public works and unified administration but left the Indian countryside and the essentials of Indian life much as they ever were. Although Britain has a wealth of Roman remains, clear effects of the Roman occupation on our fields, lanes and woods are very localised.

Many hundred ‘Roman villas’ are known in England. These were essentially large working farms (sometimes with other, more industrial, rural activities), which must have employed substantial numbers of servants and labourers. They were sometimes built near the main Roman roads and towns, but often they seem to have relied on the minor road network, which was probably little if at all less dense than it is in country districts now. But all this took place against a predominating background of traditional native farming (Fig. 30), which went unrecorded because it was too ordinary for comment – and of which the archaeological evidence is largely buried under our modern network of field boundaries and lanes. The straight ‘Roman roads’ that we know were only a small part of the road network in Roman times. They were the motorways of the age, built primarily for military use, and their upkeep was paid for by the state.

The coming of the Romans coincided with a time of falling sea level on the East Anglian coast. The Romans brought with them centuries of experience of drainage engineering from the Mediterranean, and for the first time made the silt fens round the head of the Wash habitable. In the course of this work they dug the Car Dyke, a remarkable waterway stretching for some 140 km between Cambridge and Lincoln as a cut-off channel intercepting all the minor Fenland rivers, and embanked the seaward margin of the silt fens between King’s Lynn and Skegness. Settlement of the newly drained fen seems to have been haphazard, and did not last for more than a century or two.

FIG 30. Outlines of small semi-regular fields, probably of Iron-Age origin (‘Celtic fields’), on the hillside below Malham Cove, Yorkshire. April 1974.

Roman Britain was probably somewhat, but not greatly, more wooded than now. Woods would have taken their place along with fields in the ordinary farmed countryside. The larger river valleys were probably unwooded. So most likely were the shallow soils of the chalklands, and many areas that now are moorland. These would have been used for grazing. Remnants of the wildwood were probably confined to remote places. It is important to remember that for the Romans, as for the Iron Age Celts they conquered and the Anglo-Saxons that followed them, woods would have been a valuable resource. The wood not only supplied timber from the large trees. It provided (renewably, from the underwood) for the energy supply of the community, for cooking, for keeping warm in winter, for industry (iron smelting and working, pottery and brick and tile making). The luxuries the more opulent Romans loved – hot baths, underfloor central heating – all depended on a reliable local supply of brushwood. There was no other source of energy.

The villas declined after the Roman legions left early in the fifth century. Some Roman ways persisted for a time, including by then Christianity. Over most of England the Roman way of life succumbed to fifth-century Anglo-Saxon invaders, but this was not marked by an immediate collapse into chaos. The Dark Ages were principally ‘dark’ in that they left few written records. Neither pollen analysis nor archaeology records any sudden increase of wildwood after the Romans left.

The Anglo-Saxons found England in many ways not radically different from what had greeted the Romans four or five centuries previously. The Anglo-Saxons founded many settlements. They seem to have liked more compact villages than their Celtic predecessors. There was probably more displacement of population with the Anglo-Saxon influx. Both place-name and blood-group evidence show Anglo-Saxon influence predominating over most of England and southern and eastern Scotland, with predominantly Celtic populations remaining in Cornwall, Wales, an area behind the Fens (which shares St Neots and St Ives with Cornwall) and in the Pennine dales, north and west Scotland, and of course Ireland. Scandinavian settlement during the Anglo-Saxon period added another linguistic (and blood-group) element.

Consequently, Britain has more complexity in its place-names than many European countries. Even in Anglo-Saxon country, names of rivers are often of Celtic origin: Avon, from afon in Welsh or abhainn in Gaelic; Usk, Esk, Exe and Axe from Gaelic uisce, water (the same root as ‘whisky’); Derwent meaning a river where oaks grew (Welsh derwen, oak); and names ending in -caster, -cester or -chester were towns by Roman forts (Latin castra). Most English place-names are from Anglo-Saxon roots, but in the north and east of England, settled by Danes from the ninth century onwards, unmistakably Scandinavian place-names are common, such as Whitby, Scunthorpe and Derby. Tenth-century Norwegian settlement in northwest England is marked by names such as Kendal and the many ‘Kirkbys’ and ‘-thwaites’, and by the ‘fells’ and ‘gills’ of the Pennines and Lake District. In the west, Celtic place-names predominate, and Norman French was a later addition to the mix.

What can be gleaned from Anglo-Saxon charters indicates that the distribution of woodland did not differ greatly from what is recorded in Domesday Book, after the Norman conquest. Pasture can be taken for granted, as can the enclosed-field farming landscape. Some specific references to (hay) meadow can be inferred from Anglo-Saxon charters. Opinion is divided as to when open-field farming became established. There is no evidence for its existence in the Roman period. Open fields, cultivated in common, seem to have been an early-medieval invention that spread across Europe wherever conditions were suitable, which was mostly in flatter country. The perceived benefits are unclear. Possibly economies of scale in ploughing, making the best use of arable grazing, and saving the upkeep of fences all had a part. Place-name evidence suggests that it was already established by late Anglo-Saxon times; no doubt practice varied in different places. There are no certain mentions of it in Domesday Book (possibly because it was too commonplace to record), though a few entries could be interpreted as referring to open fields. Classic open-field farming reached its peak under the Normans and Plantagenets, several centuries later.

In the 500 years between their coming to Britain and the Norman conquest, the Anglo-Saxons (and Scandinavians) probably increased the area of farmland, managed the woodland more intensively, founded villages and made many minor changes, but they did not radically alter the English landscape.

The Normans brought to Britain organising ability, technological prowess, the Norman-French language, and big ideas. One of those was Domesday Book, the great survey of England commissioned by William the Conqueror and completed in 1086. For landscape history, with this survey the written word comes into its own.

From the Domesday record it has been calculated that in 1086 about 15% of England was wooded. The most heavily wooded areas were the Weald (70%), followed by Worcestershire (40%). Buckingham and Derbyshire were about 26% wooded, West Yorkshire, Gloucester and Hampshire were about average (14–16%), Devon and East Yorkshire 4%, and the Isle of Ely 1%. The Fens and the Breckland were almost bereft of woodland, as was a belt running from East Yorkshire to Wiltshire, and some tracts between the Severn and the Welsh border. Woodland remained a valuable resource, yielding a greater return than arable, but the period from 1100 to 1300 was a time of rapid population growth and the area of farmland expanded at the expense of woodland, so that by the mid fourteenth century the proportion of woodland in England had fallen to about 10%. Medieval woodmanship came to a high pitch of development during this period. Woods supplied not only timber, but smaller wood for hurdles, wattle-and-daub building, posts and firewood. The underwood often brought in a greater income than the timber; ‘wood’ meant the products of the underwood, not the big trees (Fig. 31). Woods had a major role as renewable biomass plantations.

FIG 31. Coppice produce near Sixpenny Handley, Dorset, May 1976. Hazel rods stacked on the right, a hurdle in course of making in the centre, finished hurdles stacked on the left. Bean poles and pea sticks were also on sale. Hurdles were just one of the traditional products of the coppice. A vitally important product was firewood, either as wood, or burnt to form charcoal. In earlier times ‘coal’ generally meant charcoal.

Meadows are the best-recorded land use in the Domesday survey, in spite of covering less than 2% of England. Hay meadows were a vital ingredient of medieval farming (indeed of all historical periods). In the summer months stock could graze the permanent pastures, but there was a period in winter when (even if the ground was not snowbound) grass growth was too poor to provide adequate forage for livestock, and they had to be fed on hay. This was especially so for the oxen (and latterly horses) that drew the ploughs, which worked hardest in the winter months, and meadows were sometimes valued in terms of the number of ploughs or oxen they would support. In well-wooded places, foliage (e.g. elm and hazel) cut from woods and dried sometimes supplemented hay as winter fodder. Meadows increased greatly during the Norman period, and became some of the most valuable land. Pastures enormously exceeded meadows in area, but are less thoroughly recorded in the Domesday survey. The recorded numbers of livestock suggest that pasture must have amounted to a quarter or a third of the landscape.

FIG 32. Fen produce: reed (Phragmites) and sedge (Cladium) for thatching. Fenside, Norfolk Broads, August 1970. Fenland areas also provided hay, summer grazing, fish and wildfowl.

The early Norman period was a time of congenial climate, and continuing fall in sea level. This gave a filip to continued settlement of the northern part of the Fens, both seaward over the upper saltmarshes and landward into the peat fens. In the thirteenth century, the ‘Roman Bank’ was built (or rebuilt) into a massive and elaborate earthwork protecting the northern part of the Fens. Fenland became the most agriculturally prosperous region of England, and its produce complemented that of the surrounding upland (Fig. 32). Much the same was true of the Somerset Levels.

The three centuries that followed the Norman Conquest saw the heyday of medieval open-field arable farming. This was largely superimposed on land that had formerly been farmed as enclosed fields. In its classic form, in open country, the open-field system generally combined some or all of the following characteristics. The arable land of a village was divided into strips, about 220 × 11 yards (200 × 10 m), distributed either regularly or at random among the participating farmers. The strips were combined into furlongs, and these into fields; the same crop was grown by all the farmers in any one field. Hedges were few. Often the village had three large fields; two would be sown in rotation (winter wheat or rye might alternate with a spring crop of oats, beans or peas), while the third was left to lie fallow (the details varied from place to place and from time to time). After harvest, the animals of the village were turned loose on the stubble and weeds of the cultivated strips, and the fallow. Individual farmers shared some of the labour of cultivating one another’s crops. The way in which strips were ploughed created a ridge-and-furrow pattern.

FIG 33. Pre-enclosure open-field ridge-and-furrow in the Dove valley near Uttoxeter, Staffordshire. The classic reversed S-shape of the ridges is well shown in the low afternoon sun. North is at the top left-hand corner. The river has evidently changed its course repeatedly since the last ridge-and-furrow ploughing. Two electricity pylons in the upper half of the picture give the scale. Since this picture was taken, the ox-bow in the centre has been obliterated by modern cultivation (© Adrian Warren & Dae Sasitorn/www.lastrefuge.co.uk).

The characteristic shapes of medieval ridge-and-furrow stemmed from the constraints of ploughing narrow strips with teams of eight oxen, with a mouldboard that turned the soil to the right. It was difficult to plough straight to the end of the strip, and easier to begin the turn 25 m or so before the headland, which created the elongated reversed S-shape of the ridges (Fig. 33). In the Midlands and north of England large areas of country show evidence of ridge-and furrow left by open-field cultivation; beautiful examples are illustrated by Beresford & St Joseph (1979). The open-field system was in its heyday in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, when it covered at least 14% of England, some land in Wales, and some Norman lands in eastern Ireland. But even in its heyday, there was land being newly brought into open-field cultivation, and open fields being enclosed. Thus in the Yorkshire Dales and in east Devon there was substantial late-medieval enclosure of former open (or ‘subdivided’) fields, along with a shift away from arable to a more livestock-based economy (Figs 34, 35). An important aspect of the open fields was that they largely underlie (and are an expression of) Oliver Rackham’s distinction between ‘ancient countryside’ and ‘planned countryside’, of which more will be said later in this chapter. The open-field system coexisted with traditional farming in ‘planned countryside’, which had numerous pockets of enclosed fields, as well as in ‘ancient countryside’, where farming in enclosed fields remained overwhelmingly predominant.

FIG 34. Medieval lynchets below Pikedaw, west of Malham, Yorkshire, April 1986. The lynchets formed part of the strip-cultivated ‘West Field’. The open fields at Malham were enclosed in late medieval times.

By no means all land was suitable for working by large teams of oxen so, especially in hilly areas, smaller-scale methods were widely used (Fig. 36a), including ‘lazy-beds’ of the kind used until modern times in the Hebrides and western Ireland (Fig. 36b). On steep slopes, cultivation strips were elongated parallel with the contours. Ploughing led to soil creep down-slope, in due course creating lynchets, steep banks separating one cultivated strip from the next. Most of the lynchets so conspicuous in chalk country date from medieval times (Fig. 37).

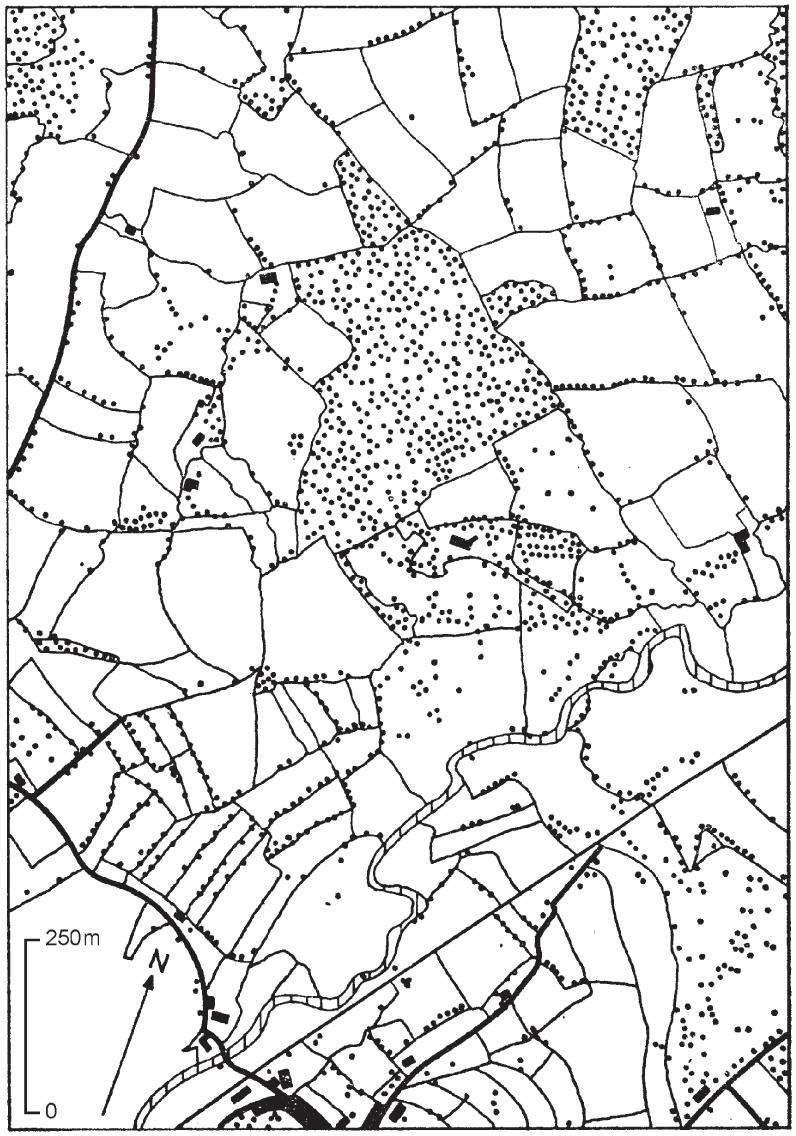

FIG 35. Medieval enclosure at Axminster, Devon. Documentary evidence shows than in east Devon open fields (‘subdivided arable’) were mostly enclosed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, leading to narrow strip-shaped closes such as this group north of Axminster, contrasting with the meadows along the river, and the irregular-shaped fields away from the town. Field boundaries as they were in the 1880s from the first edition of the Ordnance Survey six-inch map. Black dots show hedgerow and woodland trees. A sample of ‘ancient countryside’. The straight line cutting across the map at bottom right is the railway. From Fox (1972); reproduced with the permission of the Devonshire Association.

FIG 36. (a) Medieval village below Hound Tor, Dartmoor, about 330 m above sea level, February 1980. The remains of the thirteenth-century stone buildings in the middle distance overlie a succession of turf-walled houses, possibly dating back to Saxon times. Oats were grown. The ridges of a cultivated field, visible on the slope beyond, are only about 2 metres wide and are more akin to lazy-beds than to classic Midland ridge-and-furrow. The site was abandoned in the late fourteenth century, probably because of deteriorating climate (Beresford 1979). (b) Ridge-and-furrow left by modern lazy-beds, near Roundstone, Co. Galway. Despite their name, lazy-bed cultivation was hard work!

An animal that came into Britain after the Norman Conquest and was to have a major impact on our landscape is the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Originally introduced in the twelfth century as a delicacy, by the following century it had become an important article of commerce. When first brought in, rabbits were seen as needing careful tending, but they soon showed themselves hardy and impossible to confine, and have become an established part of our countryside and country tradition. More is said about them in Chapter 11.

FIG 37. Medieval lynchets near Worth Matravers, Dorset, May 1996. The lynchets on either side of the Winspit valley were in open-field cultivation from the thirteenth century till enclosure at the end of the eighteenth. Since then they have been used as pasture for livestock.

The catastrophic plague that swept through Britain and Ireland in 1348–1350 recurred at intervals in succeeding years. It is thought that the initial outbreak killed 30–45% of the population. The death rate in later outbreaks of the plague may have been lower, but seems to have borne most heavily on children and young men. The population in the 1370s was probably not more than half what it had been in the early years of the century. The Black Death at one stroke relieved population pressure and land-hunger, and created a scarcity of labour. There were not enough able-bodied men to cultivate all the open fields – and there were fewer mouths to feed. This had two major effects on our countryside. It led to widespread abandonment of open-field arable cultivation in favour of pasture and less labour-intensive sheep farming. And it gave respite to the woods, which had been hard-pressed in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

The accession of Henry VII in 1485 has conventionally been taken in England as the opening of Modern History. This date is only one of a number that mark the passing of the medieval period, and the transition to an age much easier to relate to our own (‘the past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’!). It was the time of the High Renaissance in Florence; in 1492 Columbus sailed to America; in 1517 Martin Luther nailed his ‘Ninety-Five Theses’ to the church door in Wittenberg, sparking the Protestant Reformation. It was a time of exhilarating new ideas, of questioning old certainties, and of new horizons and opportunities. In the five centuries since that time, power has shifted progressively from the Church and the monarch to trade, commerce and secular authority.

By the close of the medieval period the main outlines of the present-day landscape in England and Wales were already apparent. The distribution of woodland today is not greatly different from that in 1500, and much of the network of minor roads and field boundaries goes back to Norman times and beyond. In England the open-field landscape of the (mainly) flatter parts of country, with compact villages, few woods, and very few old hedges, formed an irregular wedge from east Yorkshire and the Norfolk coast to the chalk country of Dorset – the future ‘planned countryside’. The rest of England was occupied by ‘ancient countryside’ of scattered farms and irregular fields enclosed by medieval (or older) hedges, with more diverse settlements. Much the same distinction was observed by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers between ‘champion’ country and ‘several’ or ‘woodland’ country. Subsequent changes radically altered farming practices, field boundaries and land tenure in the ‘planned countryside’ that had been in open-field cultivation, but had much less effect on the ‘ancient countryside’.

The Scottish Highlands and islands, and Ireland, were different. Both regions were poor, and were seen as land to be exploited by (sometimes unscrupulous) landlords, and (not without cause) as unruly and a haven for enemies of the state by those in authority in London or Edinburgh (or Dublin). Physical inaccessibility and religious and language differences did nothing to further understanding on either side. The consequence was continuing poverty and continuing suspicion, violence, resentment and neglect. Neither the Irish nor the Highlanders shared in the relative prosperity of the English or the Scottish lowlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Ireland had long been a place where Norman barons could acquire land and do as they pleased out of reach of the King of England’s authority. Henry VIII had such trouble with his rebellious Anglo-Irish and Irish subjects that in 1534 he laid down that all lands in Ireland were to be surrendered to the Crown, and then re-granted. When Elizabeth I came to the throne, Catholicism in Ireland represented a dangerous threat, and she responded by making her father’s edict a reality and applying it with ruthless severity. A last rising by Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone was defeated in 1601 at the Battle of Kinsale. This led to the ‘plantation’ of Ulster with (largely) Scottish presbyterian settlers from 1610 onwards. Ireland was the victim again later in the seventeenth century, when the bitter divisions of the Civil War in England spilled across the Irish Sea. And when William of Orange came to the English throne in 1688, to replace the deposed Catholic James II, it initiated a train of events that this is not the place to recount in detail. This was an inauspicious background for a new century, exacerbating rather than healing the alienation between predominantly Catholic Ireland and Protestant Britain.

Medieval Ireland had less woodland than England, but was relatively well wooded compared with later years, and had a coppicing tradition. Woodland probably covered 2–3% of the land area at the time of the Civil Survey in the 1650s. This was mostly recorded as ‘shrubby’ (most likely hazel?), or oakwood. Only a tenth of the wood recorded in the 1650s was still there two centuries later; most was replaced by ordinary farmland. There is little doubt that the primary cause of this destruction was the expansion of agriculture to meet the needs of an expanding population. With an abundant supply of peat as domestic fuel, woods had little value, so they were grubbed up for farming. Woods were preserved longest in districts with an active iron industry, notably western Co. Waterford. Ironworks remained productive for a century or longer on local woodland; they were probably relatively small enterprises, supplying a local market, and fuelled by a renewable regularly harvested supply of underwood.

The Highlands’ problems were different, and their troubles came later. For most of the seventeenth century there was a Stuart king in London, but after 1688 that tie of loyalty to the British Crown was broken, culminating in the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745, and the eventual crushing defeat of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ at Culloden in 1746. These uprisings spurred the government in London 1724 to appoint Major-General George Wade to build barracks, bridges and roads for control of the region. Between 1725 and 1737 Wade directed the construction of some 400 km of road and 40 bridges, linking the permanent garrisons in the Highlands, and raised militias to supplement the garrisons. The net effect of the Jacobite rebellions was to open up the Highlands and strengthen the grip of the authorities on the region.

From the scanty evidence, there was little woodland in the Scottish Lowlands or Southern Uplands in medieval times, and of what there may have been, little trace remains. Ancient woodland is virtually confined to the Highlands. The oakwoods of the west Highlands share a similar history with the western oakwoods of England, Wales and Ireland, and similarly supported iron working and tanning. The native pine woods of Deeside and Speyside were long a source of timber. There may well have been substantially more pine forest than there is now, but we would probably be wrong to assume that the Highlands were extensively covered with pine forest within historical time. Birch was no doubt always there.

In 1600, Parliament passed ‘An Act for the recovering of many hundred thousand Acres of Marshes’, but nothing much came of it until, under the sponsorship of the 4th and 5th Earls of Bedford and the advice of the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden, the ‘Old Bedford River’ was created in 1637, and a parallel channel, the ‘New Bedford River’ or ‘Hundred Foot Drain’, in 1651. These were enormous straight drains, which diverted the waters of the Great Ouse, which had flooded the Great Level every winter, directly northeastwards until they rejoined the old course of the river at Denver. The Ouse Washes between the two Bedford Rivers provided a vast reservoir for flood-water in winter. The water of the minor Fenland rivers (Cam, Lark, Little Ouse and Wissey), which formerly discharged directly into the Great Ouse, now only joined the main flow at Denver. The Bedford Rivers were only the largest of a complex system of drainage works. At first the enterprise was a great success, but within a few years the consequences of shrinkage and wastage of the peat began to tell. Once the peat was no longer waterlogged, the organic matter in the fertile black peat soil oxidised and wasted away, lowering the surface of the land. This led over the years to demands for ever-deeper drainage. At first this was achieved by windmills, and from about 1820 these were replaced by steam-powered pumping stations, till 1851 with scoop-wheels, then for a century with centrifugal pumps, replaced successively from the 1940s onwards by diesel and electric pumps.

Some drainage works in the Somerset Levels were undertaken in medieval times, mainly by Glastonbury, Athelney and Muchelney Abbeys and their tenants, winning pasture and meadow from the marshes. Serious interest in draining the Levels re-emerged in the seventeenth century, when Vermuyden undertook some minor works but could not persuade the commoners to a more general drainage scheme. That had to wait till 1795, when the 17 km King’s Sedgemoor Drain (Fig. 38) was completed. The Drain, which was upgraded in 1972, operates entirely by gravity, but flood-water from many of the Somerset moors is pumped, originally by steam (Fig. 39), now by electric pumps. The Huntspill River, cut early in the Second World War, drained the Levels between Glastonbury and the sea, and added to the efficacy of King’s Sedgemoor Drain. The Somerset Levels, largely used as pasture (with a thriving osier industry in the past), have largely escaped the problems of peat wastage that beset the Cambridgeshire Fens.

FIG 38. King’s Sedgemoor Drain, completed in 1795, looking towards Bawdrip and Knowle from near Chedzoy, Somerset, September 2010.

FIG 39. The steam pumping-engine at Westonzoyland, Somerset, installed in 1862 to replace an earlier (1831) beam-engine and scoop-wheel. The two vertical cylinders drive a horizontal crankshaft, while a bevel-geared flywheel driving the vertical impeller-shaft of the centrifugal pump at the bottom of the pump-well. The machine could raise 100 tonnes of water a minute a height of 1.2 m, and worked regularly until 1951 when it was replaced by a diesel pump. Similar pumping engines were used in the Cambridgeshire Fens.

In 1701 Jethro Tull invented a horse-drawn seed drill, which would sow seed more precisely and less wastefully than the hand-drilling customary at the time. He had various other inventions (or re-inventions) to his credit, including a horse-hoe, and in 1731 he published his book The New Horse Hoeing Husbandry. His methods were not generally adopted for many years, but he came to be recognised as a major pioneer of mechanised farming. Charles, 2nd Viscount Townshend (‘Turnip Townshend’) introduced into England the four-field crop rotation practised by farmers in the Waasland region of the Netherlands – wheat, barley, turnips and clover. This did away with the fallow of the traditional medieval three-field rotation. The root crop provided winter feed for livestock and made it easier to hoe between the rows, so helping to keep weeds in check, and including a legume in the rotation countered the depletion of soil nitrogen by the other crops. Notable advances were also made in animal breeding during the eighteenth century. These innovations were slow to catch on, and they were not widely adopted until the Napoleonic Wars and the Industrial Revolution had radically changed the economic climate in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Royal Agricultural Society of England was founded in 1838, with the motto ‘Practice with Science’. John Bennet Lawes established an experimental farm on his estate at Rothamsted in 1842. The science of plant nutrition and the first artificial fertilisers were developing at about the same time.

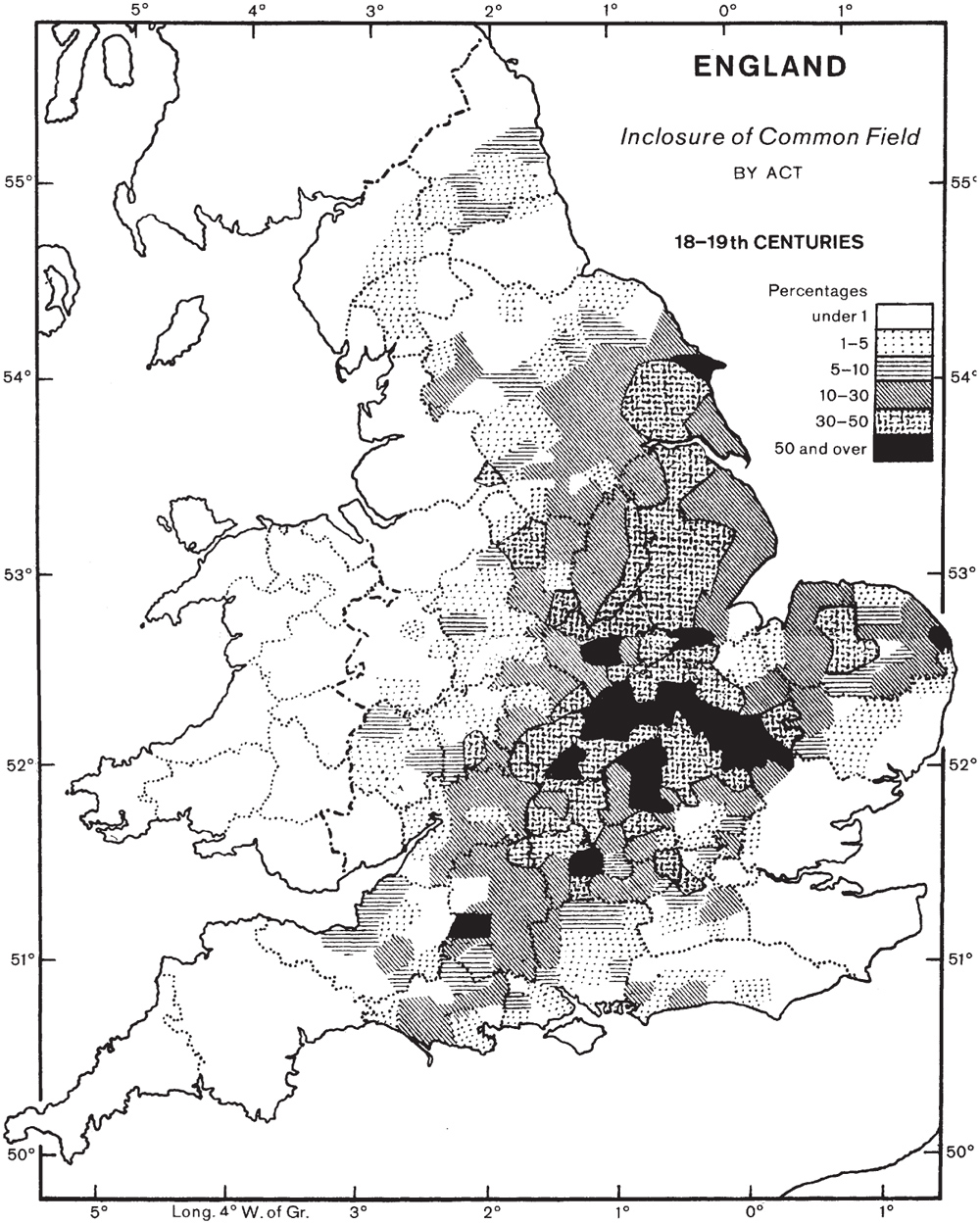

Open-field farming on the medieval pattern was increasingly an anachronism, and by the opening of the eighteenth century change had become inevitable. Since the heyday of the open fields, there had been some local enclosure, but it became a political issue in the late seventeenth century, with traditionalists (including the Church) opposing enclosure, and progressive landowners and farmers advocating it. In total there had been about 4½ million acres (nearly 2 million hectares) of open field. Around 150,000 ha were enclosed before 1760. Between 1761 and 1844 more than 2500 Enclosure Acts were passed, dealing with nearly a million hectares. The General Inclosure Act of 1845 dealt with most of the remainder; another 80,000 ha were enclosed after this Act (Fig. 40). Over the same period, land in Ireland, on which the only hedges were along townland boundaries and fields of 50–100 ha were not unusual, was subdivided into fields of which few exceeded 6 ha.

FIG 40. The extent of the Parliamentary Enclosures in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. From Gonner (1912). This map gives a rough idea of the distribution of ‘ancient countryside’ (white) and ‘planned countryside’ (shaded), but the two form a finer mosaic than is shown here, particularly in the areas with lighter shading. See also the maps in Barnes & Williamson (2006).

Significant agricultural improvement could not have taken place without enclosure, but the whole process was disruptive of traditional rural life, displacing many country people to the expanding industrial towns, and it was expensive in legal fees. The old open fields, which often ran to a hundred hectares or more, needed to be subdivided and fenced. The enclosure commissioners tried to form square or squarish fields, usually 2–4 ha on smaller farms. The field might be up to 20 ha or so on large farms, but these large fields were often subdivided later. The new fields were commonly divided by hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) hedges (Fig. 41), often with ash or elm saplings at intervals. These grew up into our familiar lowland landscape of hedged fields with hedgerow trees, but the hedges are nothing like as rich in species as the much older hedges of ‘ancient countryside’.

In England, large areas of heath and upland common were also enclosed during the nineteenth century. Some of the heathland was taken into arable cultivation, most extensively in Norfolk and the chalk country, but much remained uncultivated, particularly on the poorer and more intractable soils, and in the uplands. There, the Enclosure divisions stand out by their straightness, and in country with suitable walling-stone often take the form of dry-stone walls, not hedges.

FIG 41. ‘Planned countryside’: former unfenced common divided into large fields with straight hedges on the chalk north of Lulworth, Dorset.

The troubles of the Highlands did not end with the repressive measures taken by the government in the wake of the Jacobite risings. The ‘Clearances’ are an emotive subject for Scots. But they were seen as ‘improvements’, and moving with the times, by many landlords, who sometimes had little scruple for the people they displaced. In the 1730s, McLeod of McLeod is said to have been experimenting with sheep in Skye. Many on the mainland followed him. Tenants were ‘encouraged’ (often forcibly) to move off land judged suitable for sheep and were accommodated in poor crofts on the coast, where they were left to fend for themselves as best they could. The ‘Year of the Sheep’, 1792, is remembered as a notable year of enforced migration. The people were not only moved to the coast; many were put on ships to Nova Scotia, and many of these seem to have been Catholics. In 1807, Elizabeth Gordon, 19th Countess of Sutherland, wrote of her husband Lord Stafford (later Duke of Sutherland) ‘he is seized as much as I am with the rage of improvements, and we both turn our attention with the greatest of energy to turnips.’ The same year, 90 families were compelled to leave their crops in the ground and move all their possessions 30 km to the coast, and that was only beginning. The duke was obviously an ambitious, energetic and forward-thinking man, but he is still remembered by many Highlanders with a bitterness rivalling the hatred many Irish people still feel for Cromwell.

To the landlords, the clearances did not necessarily mean depopulation. Apart from fishing, the crofters’ settlements on the coast were a source of cheap labour for the kelp industry, which was profitable at the time; indeed at least until 1820 emigration was actively discouraged. Tim Robinson (1986) has given a vivid account of the kelp industry in the Aran Islands (Co. Galway). Attitudes changed during the 1820s with the collapse of the demand for kelp, and many highlanders moved to the growing cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee, or emigrated to Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The Highland potato famine from 1846 to 1857 caused renewed hardship, and gave further impetus to depopulation and (sometimes enforced) emigration.

During the nineteenth century, the Highlands became a playground for the rich – deer-stalking, grouse-shooting, and salmon and trout fishing. The Balmoral estate was bought by Prince Albert for Queen Victoria in 1852, adding a royal cachet to the Highlands. This brought some employment to the region, but did nothing for the crofters in the west.

The story of the Irish potato famine – ‘The Great Famine’ – has been told in detail many times; all that is needed here is to record the bare facts. Largely owing to repressive laws against Catholics, only reformed in 1793, early-nineteenth-century Ireland was backward and poverty-stricken. There had been sporadic failures of the potato crop from the early eighteenth century, and more frequent failures during the early decades of the nineteenth. In the late 1830s and early 1840s many districts suffered severe losses. Maybe a more virulent form of potato blight (Phytophthora infestans) was introduced from America in 1844. At all events, the infection spread rapidly, and by mid-August 1845 had reached Holland, Belgium, northern France and southern England. On 13 September the Gardeners’ Chronicle stopped ‘the Press with very great regret to announce that the potato Murrain has unequivocally declared itself in Ireland.’ The blight destroyed at least a third of the crop in 1845. Three-quarters of the crop was lost in 1846, and that winter a third of a million destitute people were employed in public works. Seed potatoes were scarce in 1847 and few were sown so, despite an average crop, hunger continued. Yields in 1848 were only two-thirds of normal.

After a period of very rapid growth, the population of Ireland was just over 8 million in 1841, and about half of that a century later. Probably about a million people died of starvation or disease as a direct result of the famine. The rest emigrated. Emigration from Ireland was nothing new. Between the defeat of Napoleon and the famine probably at least a million emigrated. By 1854, between 1½ and 2 million more had left Ireland. Emigration was to Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia. Already by 1850 the Irish made up a quarter of the population in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore (Maryland). Emigration continued throughout the Victorian period and beyond, but now it was driven by the quest for greater opportunity and reward, rather than dire necessity.

The Irish nationalist John Mitchel wrote, ‘The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the Famine.’ He was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation to Bermuda for his pains, but there was a lot of truth in what he wrote. The Famine, and all that had gone before, left Ireland a bruised, backward and rather isolated country, with very little woodland, but wonderful bogs (now sadly depleted). In the west, evidence of depopulation remains very obvious on the ground. I remember Dr Harry Godwin (as he then was) returning from the 1949 International Phytogeographical Excursion in Ireland, saying that his pervading impression was of a ‘cow-blasted landscape’. In the last half-century things have changed – most would say for the better.

The industrial revolution went hand-in-hand with the agricultural revolution. Growing industrial towns absorbed the population displaced from the country by enclosure and agricultural improvement, but at the same time provided the market for the expanding productivity of farming in England, where enclosure and the drive for ‘improvement’ combined to encourage widespread ploughing-up of pasture to increase the area of arable. In a manner of speaking, this enabled England (and lowland Scotland) to absorb (or export) its population problems. The British Empire provided both space for surplus population, and a source of cheap food. Industry put farm machinery within reach of even small farmers, and increasingly made chemical fertilisers available to supplement the practices of traditional husbandry. Steam power was harnessed to agricultural use with traction engines, which beside their use for transport could power threshing machines. With the invention of the internal combustion engine, mechanical assistance in farming was to become all-pervasive.

The pioneer industrialists were proud of their achievements, and often lived within sight of their mills and factories. But mass industrialisation created a drab and brutal environment, and unhealthy living conditions for the mass of people in the growing industrial towns and the coal-mining areas that fed their industries. Many at the time (and later) deplored industrialisation and its consequences. Anna Seward (1747–1809) in her sonnet to Colebrookdale wrote of the desecration of a beautiful valley by ‘… umbered fires on all thy hills … with columns large, of black sulphureous smoke, that spread their veils, like funeral crape upon the sylvan robe, of thy romantic rocks.’ And almost two centuries later Hoskins (1955) wrote with feeling about Nottingham’s transformation from ‘one of the most beautiful towns in England’ to ‘a squalid mess’, through a combination of industrial growth, enclosure and self-centred greed. These things are the seamy side of Britain’s historic rise to economic pre-eminence during the nineteenth century.

The industrial revolution had mainly indirect effects on our landscape and vegetation. One direct effect was atmospheric pollution, especially smoke and sulphur dioxide pollution around the major industrial towns – and as most people still used coal fires to keep warm at home, small towns were not immune. In my schooldays, a day in London left your shirt collar and cuffs with a dark ring of grime, and you could smell sulphur dioxide at the main-line railway stations. When I first knew the industrial north of England, the towns looked like a wall-to-wall Lowry painting, and the buildings were black. That all changed with cleaner air; the incidence of bronchitis has fallen, and epiphytic lichens and mosses now grow in places where they have not been seen for a century.

The Exeter canal, built in 1564–7 to bypass the weirs on the Exe and enable barges to reach the port of Exeter, was the first modern canal in Britain; it had locks (an innovation) and a towpath. James Brindley’s canal (1760) built for the Duke of Bridgewater to carry coal from the coal-mines at Worsley to Manchester was the pioneer that others followed. The eighteenth-century canals were impressive engineering achievements, with locks, cuttings and tunnels. Brindley’s canal included an aqueduct over the River Irwell, and Telford’s Pontcysyllte aqueduct carrying the Ellesmere Canal over the River Dee is a striking sight from the A5 road near the Welsh border. The canals vastly cheapened the transport of heavy materials over long distances (and incidentally brought stretches of water to country that formerly lacked them). The railways completed the job the canals had begun, of making cheap coal widely accessible. This ended most people’s reliance on wood as the staple source of energy. Coal was convenient, compact, generally available and less expensive than the alternatives. With hindsight, one could say that it had the deeper psychological effect of severing our tie to the land and the seasons. If you ran out of coal, all you had to do was to order (or mine) more. Ocean transport by steamship had the same effect with food and other commodities. There is nothing wrong in that, as long as you recognise that all resources are finite.

The last was an eventful century: two world wars and the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, the development of powered flight, the general adoption of electricity for lighting and power, and of internal-combustion-engined vehicles for transport on land (and sea), the development of telephones, radio and television, the development of information technology and the Internet, and the establishment of the European Community, to list only a few of the more notable. Perhaps it is surprising that the twentieth century did not have more effect on our landscape and flora and fauna.

In 1860, C. C. Babington, Professor of Botany at Cambridge, wrote, ‘Until recently (within 60 years) most of the chalk district was open and covered with a beautiful coating of turf, profusely decorated with Anemone Pulsatilla [pasqueflower] and Astragalus Hypoglottis [purple milk-vetch], and other interesting plants. It is now converted into arable land.’ This was the period of rapid population growth in the industrial cities, and enclosure and agricultural improvement were in full swing. He might have added that many ancient woods went the same way as the chalk turf, but many woods found a new role as fox covert and pheasant preserve. After Babington’s time, the countryside regained a degree of stability, and in general did not change greatly over the decades until 1939. Britain was dependent on imports for a substantial part of its food in the 1930s. During the Second World War, the German U-boat campaign exploited that dependence, and although nobody went hungry, rationing was severe and there was little choice and few luxuries – and both sides devoted a substantial part of their war effort to ‘the Battle of the Atlantic’. After the war it was deliberate government policy to make Britain self-sufficient in food. Ploughing was encouraged; in particular, large areas of the flatter chalk country were converted to arable. Looking at air photographs taken in the 1940s, with their wealth of archaeological detail still preserved beneath the old turf, it is hard not to regret that this phase of post-war ploughing was not done more sensitively. For decades after the war, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food was King, to the intense frustration of other interests in the land!

Many of the most notable twentieth-century changes in the British and Irish landscape had either natural or economic causes. The collapse of the rabbit population through myxomatosis was probably started by a deliberate introduction (Chapter 11), but would very likely have happened sooner or later anyway, once the virus was in Europe. Dutch elm disease has to be seen as a natural phenomenon, and the outbreak in the 1960s was certainly not the first (Chapters 2 and 5). In farming, ready availability of artificial fertilisers and pressure to maximise yields spelt the death of the traditional species-rich permanent grasslands (Chapter 9) and that, combined with the newly available selective weedkillers, largely eliminated arable weeds (Chapter 10). New breeds, economic pressure to maximise yield, and the ready availability of pelleted livestock feeds, combined to change farmers’ attitude to livestock, and to a decline in casual grazing, so many heaths and rough grasslands went ungrazed. And there was no longer an economic demand for the products of the traditional woods, with the result that the burden of managing (and conserving) these traditional elements in our landscape has fallen on the statutory conservation and amenity bodies, and on private organisations such as the National Trust, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the County Wildlife Trusts.

Forestry is not specifically a twentieth-century phenomenon; many landowners in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries established plantations of various sorts. Plantation forestry has nothing to do with woodmanship as traditionally practised. It is more akin to growing an arable crop. Woodmanship had to do with managing a renewable resource, as has much Continental forestry. The Forestry Commission was established in 1919, with the aim of making good the timber felled during the 1914–18 war, and increasing the stock of timber to provide a strategic reserve. After the 1939–45 war planting was continued on a larger scale, and subsidies were made available for planting trees. Quick-growing conifers were the preferred choice, particularly Sitka spruce and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) – or, on soils too poor for those species, Scots or lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta). The conifer plantations have their place in the landscape, like other crops, provided they are economic. But the foresters’ remit was to grow timber, and the old deciduous woods did not accord with that primary aim.

The subsidies that were intended to promote the provision of a strategic reserve of timber had by the 1980s outlived their original aim, and become a burden of no benefit to the taxpayer, either economic or strategic. However, they remained potentially a profitable subsidised investment, and so created a powerful vested interest in their continuance. This worked against the interests of nature conservation. Matters came to a head over proposals to drain and plant wide areas of the Flow Country of Caithness and Sutherland (Fig. 42). The foresters believed they were working for progress and improvement (as did progressive landowners in earlier centuries). A nearby hotel saw forestry as an unwanted intrusion into a wild landscape, which they and their guests valued. Landscape and nature-conservation interests were opposed to the replacement of a near-unique landscape and habitat by yet more conifer plantations, especially as the real economic value of the planting was questionable. It made a cause célèbre at the time, and had political repercussions including the break-up of the then all-UK Nature Conservancy Council.

FIG 42. Clash of interests: ‘improvement’ or ‘vandalism’? Peatland prepared for forestry, Flow Country near Forsinard, Sutherland, September 1989.

Many of the general public objected to conifers as such when their true objection was to plantation forestry single-mindedly focused on timber production – and they, like many foresters, failed to understand the nature of the old deciduous woods they did like. Happily, understanding of traditional woods, their value to amenity and biodiversity, and their role as historical documents, has increased. Many foresters are interested in woods and their management, of whatever kind. The Forestry Commission now has a broader remit to include amenity. The subsidies that caused so much damage for no useful return to the taxpayer have gone. But the tendency to confuse ‘woodland’ and ‘forest’ (in the forester’s sense) lingers on.

The German biologist Häckel coined the word ecology in 1866 for the study of the interactions of organisms with their physical environment and with other organisms, but the development of the science of ecology to its present prominence has been largely a twentieth-century phenomenon. Early studies in ecology were largely of individual plant and animal populations and communities (Chapter 4), but from the 1940s and 1950s interest expanded to the worldwide scale, with the writings of Charles Elton, Eugene and Howard Odum, Rachel Carson and many others. Public awareness of ecological issues was alerted by the finding of pesticide residues and industrial chemicals such as DDT, dioxins and CFCs worldwide, and in places and organisms far from their intended use. A good deal of ecology is scattered through the pages of this book. Ecology can sometimes set firm limits, and make categorical predictions, but often (like weather forecasting) it can only express probabilities. Nevertheless, if we ignore such predictions and they turn out to be right, we have only ourselves to blame. The ‘muck and mystery’ brigade, masquerading under the banner of ‘ecology’, do the science of ecology and us all a disservice. Ecology is too serious for that. We ignore it at our peril.