To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.

Sophia leaned forward at the restaurant table toward her friend Elizabeth, as if she were hearing an intensely fascinating secret. Sophia and Elizabeth met last year at the marketing company they worked for and had more recently been developing a friendship. Sophia’s slim arm rested on the tabletop, her eyes unable to conceal their surprise and interest. She was a tall, lean woman, with a tendency to anxiety.

Elizabeth was far curvier than her friend, with glowing, clear skin. Elizabeth struggled with what she called her “apple shape,” carrying a lot of weight around her belly, despite the many diet programs she had embarked on over the years.

“So, you have it too?” Elizabeth spoke to her friend in a hushed tone, looking sideways, as if ensuring that nobody was listening to their conversation.

“I do.” Sophia gestured to her jawline, which was inflamed with angry-looking pimples. “You’d think I’d be past this stage by age thirty-four!”

As a young woman of thirteen, Sophia’s period began as expected. Around the same time, her skin began to break out terribly, particularly along her jawline and on her back. Her periods were always irregular, arriving at their leisure (usually about two months apart), bringing with them intense cramps and heavy bleeding. Over time, Sophia developed coarse hair on her chin and cheeks. This was a great source of distress. She spent many hours trying different hair-removal techniques and attempting to find treatments for her acne, none of which were particularly effective.

Last year, after doing some online research, Sophia asked to be referred to a gynecologist, and her bloodwork came back with high levels of testosterone. The doctor diagnosed her with PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome.

Once home, Sophia immediately Googled PCOS, intent on finding out more about the condition that had caused her so much difficulty. What she found was a great deal of confusing information. Descriptions of voluptuous women with ovarian cysts and high testosterone levels seemed to be central to almost every article on the topic. Much of it didn’t match Sophia, as her ultrasound did not show any cysts, and she was a very slim woman. She knew that her testosterone was high, but she wondered why her case was so different from most of the other women who had the same diagnosis.

Elizabeth, on the other hand, had been diagnosed with PCOS at a young age. As a child, she had always struggled with her weight, and as she reached adolescence, she began gaining weight quickly. Both her mother and sister had a similar body composition, as did many of her extended female relatives. As a teenage girl, Elizabeth was elated to get her first period, but it did not return again for another ten months. Although many of her friends experienced a similar irregularity at first, eventually their periods became regular. It was not so for Elizabeth. This was how her cycles continued on: She averaged two periods per year. She dreamed of having normal cycles and feeling feminine like her friends, but her cycles never regulated on their own. Unfortunately, Elizabeth usually had to take a course of prescription medication to bring on her monthly menstruation.

Elizabeth had many ultrasounds of her ovaries over the years, and they were always full of small, round cysts—the classic “string of pearls” described in textbooks. Similarly to Sophia, Elizabeth also had hair growth on her chin and cheeks, but it was blond and fine, and most people didn’t really notice it.

Elizabeth had married a wonderful man when she was thirty-two, and they desperately wanted to start a family together. Again, things weren’t easy: Together, they began an intense battle with infertility that had been going on for the past two years. The fertility clinic felt like a second job to her. It was an extra place she had to go each morning, bright and early at 7:00 a.m., something she despised.

She felt consumed by the “project” of getting pregnant: charting, peeing on sticks, waiting and agonizing for two weeks every month, along with medications, stirrups, ultrasounds, and procedures. When it didn’t work, which was always, she had to do it all over again the following month. Why couldn’t she just conceive easily, like all of her friends did?

“So, you have PCOS, too? I’m surprised! It’s just that you just don’t look like . . . ” Elizabeth trailed off, taking a sip of her sparkling water, feeling a sense of hesitant camaraderie.

“I do, though I find my case isn’t the ‘typical’ sort,” Sophia replied. “One thing I do know is that whatever it is that I have going on with my hormones, it’s definitely causing me a lot of grief.”

How could these two very different women have the same syndrome?

Do you ever wonder why PCOS has so much variability? More and more information on PCOS is being revealed at a rapid pace, with hundreds of new studies released each year.

PCOS has long been a mystery in women’s health, as the underlying causes were never fully understood. Back in 1935, two researchers, Stein and Leventhal, described a group of larger-sized women that had coarse, male-pattern hair growth (known as hirsutism) on their faces. This group also had enlarged ovaries with multiple small cysts and irregular menstrual cycles. They named the condition Stein-Leventhal syndrome. Since that time, the diagnosis has expanded and includes many women far outside of the typical sort of PCOS that they had initially described.

The information, types, and definitions of PCOS used in this book are based on current research and on my clinical experience in treating hundreds of women with the condition. As the research grows, many of the concepts in this book may be expanded upon or entirely changed. The understanding of PCOS is really just beginning, and I look forward to seeing it grow.

Interestingly, there is a movement to change the name of PCOS from polycystic ovary syndrome, as many women with the syndrome do not actually have polycystic ovaries at all. The new name is still being debated but is hoped to express the many different types of the condition.

As the most common hormonal disorder in women of reproductive age, PCOS affects an estimated 116 million women worldwide and can affect hormones, fertility, the skin, cardiovascular health, and metabolism. PCOS is called a syndrome, rather than a disease, as there is a wide range of ways that PCOS can present and a variety of factors that characterize it.

PCOS can be expressed in women with excessive androgenic hormones like testosterone, producing acne and hair growth as we’ve seen in Sophia’s case. Or it can present similarly to Elizabeth, with abdominal weight gain, infertility, and loss of ovulation and menstrual cycles.

This is why researchers have been puzzled about PCOS for years, with significant argument between professional groups about what constitutes a diagnosis of PCOS. In the last decade, however, there has been some agreement that there are, in fact, different “types” or phenotypes of the disease, which explains why two women with PCOS might look very different.

In 1990, the National Institute of Health (NIH), one of the world’s foremost medical research centers, defined PCOS as requiring three criteria:

Interestingly, the NIH did not require a woman to have ovarian cysts to receive a diagnosis of PCOS. Overall, the NIH criteria are stricter, and fewer women have PCOS according to this definition.

In 2003, there was a meeting in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, sponsored by two of the top reproductive medicine groups: one European (ESHRE) and one American (ASRM). Together, leading experts gathered in this northern city to focus on refining the definition of PCOS. The meeting produced what are known as the Rotterdam criteria, which are arguably the most widely accepted criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS.1

This meeting produced something else that caused quite a stir in the world of endocrinology. What made the Rotterdam criteria different in diagnosing PCOS was that women didn’t need to have all three of the characteristics. Only two of the three were required for a diagnosis. This gave birth to the idea of different phenotypes or “PCOS Types.” It also produced two totally new “types” of PCOS, which didn’t exist before.

The three criteria introduced by the Rotterdam consensus were—

It’s important to note that PCOS is a very complex disorder, and that these types are mainly a holding place for what we understand as of now. These types will likely change over time as we learn more about what makes up this complex and common condition in women’s health.

PCOS has myriad symptoms, ranging from hair loss to fatigue and weight gain. These various symptoms fall into three main categories, as evidenced by the Rotterdam consensus. For a woman to be diagnosed with PCOS, she must exhibit two of the three required criteria (anovulation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries). Let’s take a moment to explore each of the criteria in more detail.

Anovulation translates as “lack of ovulation,” but in medical terms, it can also mean ovulations that are delayed past the typical timing. The average length of a woman’s menstrual cycle is twenty-eight days. Day one of the cycle is the first day of the period, and most women will ovulate on or around day fourteen, give or take a few days.

Anovulation is technically defined as fewer than ten menstrual cycles per year. This would be equal to having menstrual cycles thirty-five days or longer in length. If you’d like to know more about menstrual cycles, please see chapter 6 for a comprehensive explanation of how the hormones, ovulation, and menstrual cycles work in PCOS.

-Fewer than ten menstrual cycles per year

OR

-Cycles that are thirty-five days long or longer

As you can see, if you have regular menstrual cycles, but they are longer than average, you may still have anovulation. This is something I see often in practice: longer-than-average cycles, though they may appear regularly. Many women actually believe this is a normal thing, but it’s most definitely not. Cycles that are thirty-five days in length or longer (even if they are regular) are a red flag for PCOS, particularly if a woman’s cycle has been longer since her teenage years.

As women age, their cycles often naturally become shorter, so anovulation may be resolved by Mother Nature as a woman matures. That said, if a woman had long cycles for many years when she was younger, as well as the other characteristics of PCOS, it is a sign that she should be assessed more closely.

Hyperandrogenism is a very long word that basically means there are high levels of hormones, such as testosterone, DHEA, or androstenedione. These particular hormones are responsible for causing male sexual characteristics like the growth of facial and body hair and hair loss in specific patterns.

-Hirsutism: hair growth on the chin, upper lip, around the nipples, on the chest or stomach, on the upper arm or thigh, or in other areas

-Acne, particularly along the jawline or on the back (Androgenic acne is often moderate to severe.)

-Hair loss in an androgenic pattern; frontal with hairline preserved or diffuse

-Elevated hormones like testosterone, DHEA, or androstenedione

In chapter 5, there will be a comprehensive discussion with more details on these symptoms.

At Rotterdam, researchers went through what it means to have polycystic ovaries. They determined that there must be twelve or more follicles measuring from two to nine millimeters or an ovarian volume bigger than ten centimeters in a single ovary. Follicles are the spherical structures in the ovary that house the eggs. On ultrasound, many women with PCOS have a larger than average number of follicles. Even if only one ovary shows an excess number of follicles or “cysts,” this can be suggestive of PCOS.

If you request an ultrasound, you can ask the technician to include the ovarian volume and to look at the number of smaller follicles in your ovary and to count them. It’s often best to have this ultrasound done on the third day of your menstrual bleed, but if you’re not having menstrual cycles regularly, you can also have this done on any given day. In women who don’t menstruate often, there is an increased chance of seeing these types of follicles regardless of the cycle day.

-Twelve or more follicles ranging from two to nine millimeters in a single ovary

-Ovarian volume bigger than ten centimeters in a single ovary

-With newer ultrasound technology, more than twenty-six follicles that are two to nine millimeters in both ovaries

Now, let’s talk about the cysts in the ovary and what they actually are. They are not true ovarian cysts, like those found in women without PCOS. One of the most common types of non-PCOS cysts is the simple functional cyst: these are large, fluid-filled sacs within the ovary that resolve on their own and happen in many women occasionally. Another type of non-PCOS cyst is the “complex” ovarian cyst: These are larger cysts that contain a variety of different types of cells and may contain blood or other tissues. In most cases, the number of simple or complex cysts is far lower than the number of “cysts” found in a woman with PCOS (often only one cyst is present, or just a few).

PCOS cysts are in fact different from both of these and are not even true cysts at all! So why do some women with PCOS have so many follicles on ultrasound? In a healthy ovary, the follicles go through a slow state of growth known as folliculogenesis for many months before the egg is ready to be ovulated.

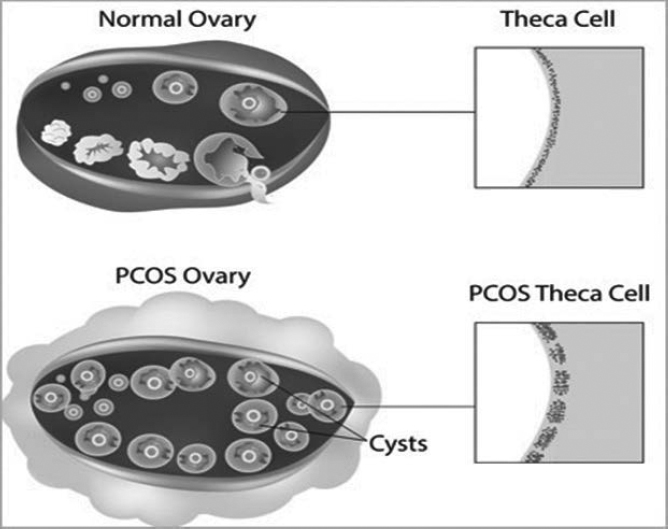

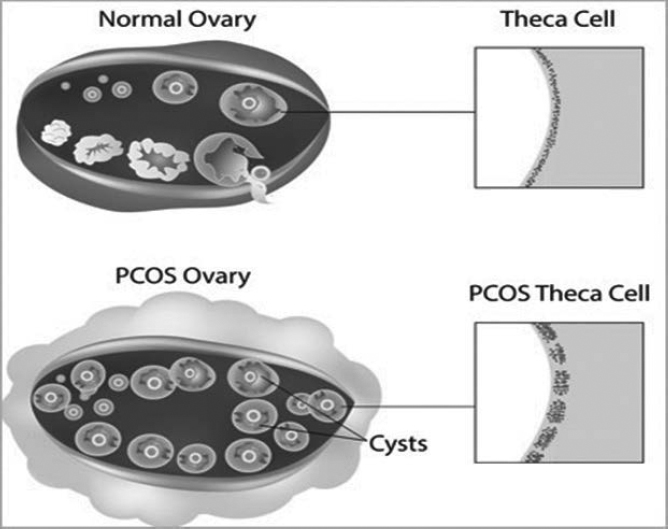

In PCOS, this process can become stalled because of high testosterone and insulin in the ovary. The outer layer of the follicle known as the theca, which produces testosterone, thickens, and the follicles stall in their development process and accumulate in the ovaries rather than going through ovulation.

Figure 1-1: PCOS “Cysts.” Cystic appearance of the ovary in PCOS versus a typical ovary. Note the thickening of the theca layer of the follicles. Courtesy of the National Institutes of Health: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

As such, PCOS “cysts” are actually just ovarian follicles that are in a state of partial development. Over time, these partially developed follicles pile up in the ovary, creating the look of multiple tiny cysts, or what is often referred to in textbooks as a “bunch of grapes” or a “string of pearls.”

Ovaries with multiple small follicles are very common in the ultrasounds of younger women, particularly in teenagers, as there is a natural abundance of follicles/eggs in this age group, which can in many cases exceed the threshold count for PCOS. In addition, during puberty, there is recruitment of many follicles as the ovary activates, without consistent ovulation as of yet, so girls in puberty naturally have a form of polycystic ovary. This, however, should resolve as girls begin to have regular ovulation and menstrual cycles.

So, for teenagers, it’s always important to be cautious when looking at your ultrasound results. This is one important reason that we don’t use the “cysts” alone to diagnose PCOS.

Conversely, women over thirty-five may have PCOS, but they have fewer follicles due to their egg bank becoming smaller with age and are less likely to have polycystic ovary appearance on ultrasound. As such, age really does matter when it comes to the “cystic” criteria. The good news is most women will decrease their likelihood of belonging to a “cystic” type as they get older.

Newer technology may be changing this long-held definition of what constitutes a “polycystic” ovary. In March 2013, a study concluded that a new threshold should be used to determine if a woman actually had cystic ovaries characteristic of PCOS.2

This is because diagnostic equipment has dramatically improved in its ability to detect follicles in the ovary. Over the past several years, many women without PCOS (and especially teenage girls who naturally have many follicles and are almost in a temporary PCOS-like state) were being diagnosed with polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, because the ultrasound technology has become so sensitive. Follicles that would have normally remained undetected by older equipment are now being picked up much more easily, increasing the number reported by the ultrasound technician.

The study concluded that a total of twenty-six follicles between two and nine millimeters long was a better marker of PCOS when using newer ultrasound technology. This study also noted that this threshold only applies to women between eighteen and thirty-five years of age. As previously mentioned, women under the age of eighteen naturally have larger amounts of follicles.

From my point of view, the Rotterdam phenotypes are simply a compilation of some of the factors of PCOS that we need to know about in order to treat the disorder and really are not specific enough to form treatment guidelines over. For the purpose of treatment, I will be teaching you to identify your own unique factors, giving you the most customized treatment program possible. I believe that the Rotterdam phenotypes are important to know about to help you determine if you have PCOS in the first place and to understand more about the intensity of your PCOS.

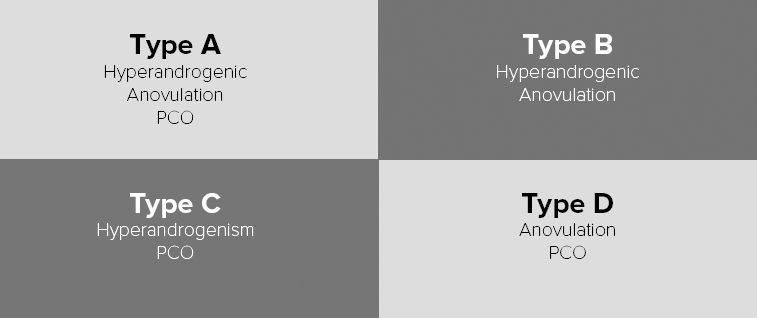

As mentioned previously, women need to have two of the three Rotterdam criteria for a confirmed diagnosis. This leaves us with four unique types named, very aptly, the Rotterdam Phenotypes:

Type A and Type B are “classic PCOS” as defined by the NIH. Type C and Type D are “non-classic PCOS.” Following are the new categories.

Type A: Delayed ovulation, hyperandrogenic, and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound

Type B: Delayed ovulation, hyperandrogenic, with normal ovaries on ultrasound

Type C: Hyperandrogenic, with polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, and with regular ovulation

Type D: Delayed ovulation, with polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, and without androgenic signs

Figure 1-2: The Rotterdam Phenotypes of PCOS

PCOS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore, other disorders that could cause these symptoms must be ruled out first. Other organizations strongly disagree with these types, especially Type D, the non-androgenic phenotype. An important international organization called the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society has concluded that, by definition, PCOS must include excess androgens. It’s also possible, however, that Type D is simply a very mildly androgenic PCOS phenotype, as will be discussed in the next section.

Molly was a twenty-eight-year-old woman with PCOS who decided to improve her health after a particularly frustrating year dealing with the imbalances of her condition. She was approximately twenty pounds above the recommended weight suggested by her doctor, and her periods only arrived every three to four months. Molly had coarse hair on her chin and neck, and her ovaries looked like the classic “string of pearls” on ultrasound. Her diet was not the best; she lived a fast-paced life and ate out a lot. Nothing too terrible, but it was rare for her to cook her own meals. When Molly brought her concerns to her doctor, she was recommended a small dose of metformin, a diabetes drug commonly prescribed for PCOS. She followed this suggestion and changed her diet to completely remove processed foods and sugar. Over a period of four months, Molly successfully lost twenty pounds, and her periods began to cycle every twenty-nine days. Through treatment, she had moved from a Type A (most severe phenotype) to a Type C (a milder phenotype).

Lisa was a thirty-six-year-old woman with PCOS who also tended to get her periods every three to four months (an improvement from her younger years, when they were farther apart). Similarly to Molly, Lisa had some hair growth on her lip and chin (though it was mild in comparison), and her ultrasound revealed clusters of tiny follicles on each of her ovaries. After visiting her gynecologist, Lisa faithfully followed a diet and medication program similar to Molly’s.

Her response was quite different, though: As had been the case for her whole life, Lisa found it exceptionally challenging to lose weight. After four months and a great deal of effort, she was only able to lose about five pounds.

Over the four-month time frame, Lisa’s periods improved somewhat, but her cycle was still fifty-two days long. On ultrasound, however, her ovaries appeared to be healthier, now just below the cutoff for the cystic type. Through treatment, Lisa had moved from a Type A to a Type B.

What was the difference between these women’s cases? Why did Molly improve so much when Lisa still struggled, despite following the same treatment?

Interestingly, Lisa was far more insulin resistant than Molly when blood tests were considered. Insulin resistance happens when the cells of the body don’t respond normally in PCOS. It’s one of the central factors in the condition, and the degree to which it is present can make a big difference in a woman’s response to treatment. Chapter 3 describes insulin resistance in greater detail.

A more severe degree of insulin resistance was surely related to Lisa’s difficulties in losing weight and was part of the reason she remained in one of the classic phenotypes. Insulin resistance is one of the first factors that we address in the 8 steps to healing your PCOS.

Frustrated with her lack of progress, Lisa visited her naturopathic doctor, who worked with her to change her insulin resistance factor. Although Lisa was already taking metformin, more help was needed since her insulin resistance markers were still elevated. She began to carefully follow a nutrition plan that managed her insulin resistance. (See chapter 9 and Appendix D for more information.)

At the same time, Lisa began an intensive exercise program and started taking supplements and herbs to improve her insulin resistance. After four months with this combined approach, Lisa began to cycle regularly every thirty days. She was elated: This was the first time in her life that she had achieved a regular cycle. Essentially, Lisa had moved from classic Type A PCOS to a full reversal of the syndrome. Over time, Lisa was able to wean herself off many of the supplements—even the metformin—and was able to maintain her healthy cycles with diet, exercise, and a few basic nutrients.

This example goes to show that each woman is unique and may require different interventions to achieve a milder phenotype, or even better, to reverse PCOS entirely! As you can see, once only one criterion remains, or if your symptoms have cleared up, you can say that PCOS symptoms have been reversed in that the symptoms are no longer evident. That doesn’t mean that you can take it easy now: Reversal is not the same as cured. You’ll always have PCOS. It is a lifelong condition, and you will always have to take better care of yourself than those who don’t have it. I like to look at that as a gift to your future self, knowing that the efforts you’ve made now will prevent many health problems for you in the future.

The take-home from this section really is this: The four phenotypes are certainly useful to understand. They are the diagnostic criteria for PCOS, and they determine how severe the condition is.

To effectively treat PCOS is a different matter. There are several important factors that need to be identified and addressed, and I hope to show you exactly how to achieve that in this book.

Now that we’ve talked about how each type is diagnosed, let’s go through each of the four phenotypes and their differences according to current research.

To make it simple, you’ll just need to determine which of the three criteria you have. If you don’t know if you have one of the criteria for PCOS, that’s OK. Take a deep breath. You’ll still be able to use this book by following the 8 steps we go through in later chapters.

To determine your PCOS phenotype, ask yourself the following questions:

To know if you belong to a cystic phenotype, you’ll have to visit your doctor to have an ultrasound, so there may be women who don’t know if they have ovarian “cysts.” If you have one of the other two criteria and suspect that you may have PCOS, you should request an ultrasound. Remember that older women who may have had this factor in the past can outgrow this as their number of eggs decreases with maturity. Researchers now believe that when girls go through puberty (when the hormonal system temporarily enters a state that is very similar to PCOS), for most women, this passes. But for women with PCOS, it continues on. It’s thought that PCOS may be similar to the hormonal situation of puberty not coming to its full completion. As such, using the cystic criteria to diagnose PCOS in a teenage girl is quite controversial, since many girls have ovaries with a PCOS type of appearance at this age.

You can now note which of the qualities you have and then combine them to determine your phenotype. If you are not able to get an ultrasound, but think you have PCOS, you can still use this book. You’ll easily be able to determine your PCOS factors as we continue on, and that is where the real ability to work on your health comes from.

In the PCOS types that follow, you’ll find that a variety of different hormones are mentioned. If you’re unfamiliar with the hormone names and what they mean, you’ll find a full discussion of the hormones and menstrual cycles in PCOS in chapter 6.

This is the most severe phenotype of PCOS, containing all three of the criteria. Women with Type A “classic” PCOS have delayed ovulations and menstrual cycles, high androgens, and a “cystic” appearance to their ovaries.

-High androgens/androgenic signs

-Irregular periods/delayed ovulation

-Polycystic ovaries

This is also known as “classic” PCOS, and many women with this type tend to have a high body mass index and increased waist circumference. Elizabeth, from the opening of the chapter, is a Type A. Some patients who have Type A are of average weight or lean, and I believe that these patients may actually have the strongest genetic predisposition to PCOS overall, because the symptoms persist strongly, despite the metabolic benefits of lower weight. The good news is that when many women, even as they get older, change their diet and exercise or make changes to their hormonal health, they can move from Type A to another, milder phenotype.

Type As seem to have the most weight accumulated around their midsections and a high LH/FSH ratio on day three of their menstrual cycle.3 They also tend to have the highest testosterone levels of all the types. This group may represent sixty percent of all PCOS patients.

Type As need to take very good care of their body as they age, as they definitely have a higher risk of developing metabolic diseases. There is more insulin resistance and a higher risk for both diabetes and heart disease.

Type As also have the highest anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels of all the types. AMH is secreted by the follicles in the ovary and is used to measure the “number” of eggs left in the reserve. Most women with PCOS secrete higher than normal levels of AMH.

Type As often have the most menstrual irregularity as well. Many women in this category can go months without ovulation, and when periods do show up, they may not be actual periods and may instead be “breakthrough bleeds.” Breakthrough bleeds happen when the endometrial lining builds up over a longer period of time, without the natural shedding of the menstrual cycle.

Type A women often have very low progesterone levels, as progesterone is only released after ovulation (which does not happen frequently). Without ovulation and progesterone, a woman will become estrogen dominant, and the lining of the uterus will thicken. After some time, the lining may begin to break down, causing spotting, irregular bleeding, and even bleeding that appears to be like a period, but which may be exceptionally painful, heavy, or clotted.

Type As have it rough! The good news is that most women can move out of type A and into another type by making changes to diet and lifestyle and by implementing natural medicine therapies.

Type B, another “classic” form of PCOS, is similar to Type A PCOS, except that the ovaries do not contain cysts.

-High androgens

-Irregular periods/delayed ovulation

-Normal ovaries

Sophia, our tall woman with acne and irregular periods in the opening story, is a Type B. Women with Type B PCOS have irregular periods or delayed ovulation and signs of high androgens, such as hirsutism, acne, or hair loss. As is the case with Type A, they have the tendency to gain weight around their waistline and can have an increased body mass index. It’s important to note that although there is an increased tendency toward weight gain in Type A and Type B, lean women can also be found in these types.

Studies have found that the main difference between Type A and Type B PCOS is that in Type B, AMH is lower, which makes sense because AMH correlates with the PCOS-like cysts of the ovary. As we mentioned earlier, with respect to cystic appearance reducing with age, Type B contains a greater number of older women.

Type B is not nearly as common as Type A and is found in only 8.4 percent of women with PCOS. According to Shroff, Types A and B share similar risks for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.4

Type C is one of the newer, “non-classic” forms of PCOS. Prior to Rotterdam, it may not have actually been considered a type of PCOS at all. In this type, we see elevated androgens and polycystic ovaries but regular menstrual cycles. This type of PCOS is also known as “ovulatory PCOS,” and it represents one of the milder forms of PCOS.

-High androgens/androgenic signs

-Regular periods: thirty-five-day or shorter cycles/ovulation

-Polycystic ovaries

Many patients who have Type A classic PCOS will be able to move to Type C when they lose weight through dietary changes or work on insulin resistance. Women with Type C PCOS tend to have medium-level values of body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and levels of androgens. Women with Type C often have lower LH/FSH ratios than Types A and B. Although Type Cs have higher androgen levels than women without PCOS, the androgens are not as high as in Type A.

One thing that is important to note is that women with Type C PCOS may actually not be ovulating within each cycle, although their period may arrive. A study found that many Type C women were only ovulating for a certain percentage of menstrual cycles.5 What looked like a period was instead something called a breakthrough bleed—the result of incomplete ovulation.

For Type C, it is important to check Day 7 post-ovulation progesterone levels and/or to do basal body temperature (BBT) charting to determine how often true ovulations are occurring. Chapter 6 and Appendix A cover these topics in detail.

Marion, a twenty-four-year-old Type C, tended to have her period every twenty-nine to thirty-four days, but occasionally her bleeding was exceptionally light. She was also experiencing significant hair loss just behind her hairline, as well as coarse hair growth on her chin. Marion was moderately slim and had been healthy her whole life, until she began to lose her hair. It was coming out at what seemed like a rapid pace, and Marion began to panic. Around the same time, she had an ultrasound from her gynecologist, who noted that her ovaries were filled with tiny follicles. She was then diagnosed with PCOS, and because her hair loss and hirsutism fit the androgenic pattern, she fit into Type C. I worked with Marion to help reduce her androgen levels and regulate her hormones. Marion made the commitment to give up her addiction to sugar and sweet treats. Although Marion’s cycles were never exceptionally delayed, with treatment, they became regular at thirty-day intervals. Over time, Marion’s hair grew back beautifully as well.

-Normal androgens

-Irregular periods/delayed ovulation

-Polycystic ovaries

Now here is where it gets interesting: Type D is the most controversial type of PCOS. Until Rotterdam, women with this type were not considered to have PCOS at all, and even now, many experts have argued that Type D is not a true PCOS. It’s quite possible that this category may eventually disappear altogether, but I would like to cover it, as I believe that there are a small number of women in this category who may be undiagnosed.

Women with this type of PCOS have no androgenic signs and normal androgen levels. They do, however, have polycystic ovaries and irregular periods or delayed ovulation. Along with Type C, Type D has more tendency toward being of lower body mass index and less insulin resistance.6 Many lean women with mild PCOS not previously detected fit into this category, particularly after stopping the birth control pill. That being said, it’s important to remember that lean women with PCOS can fit into any phenotype.

In order to be diagnosed with Type D (or any type of PCOS for that matter), the other disorders that mimic PCOS must be ruled out first. This can be achieved with proper bloodwork and testing. Again, if one of these other conditions is found to be the cause of your symptoms, you may not have PCOS.

-Hypothyroidism

-High prolactin levels

-Hypothalamic amenorrhea (a disconnect in the brain-pituitary-ovary axis)

-Non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (a rare genetic condition of the adrenals)

Although there has been much argument about Type D, there may actually be a middle ground between the two positions. According to Guastella, Longo, and Carmina, Type Ds in fact do have a very mild androgen excess when compared to women without PCOS. In Type D, androgens are within the normal range but still may be slightly higher than in women without PCOS.

It’s also been found that when women with Type D are stimulated with certain medications, they will in fact produce excess androgens compared to women who don’t have PCOS. Given that measuring androgens in the blood can be very challenging (more about this in chapter 5), this type may simply be the mildest variant of PCOS.

Mina was a twenty-four-year-old woman who only had periods every four months. She went to a gynecologist who performed an ultrasound for her, and it was determined that she had polycystic-appearing ovaries. When the doctor ran bloodwork, her testosterone and androgen levels were completely normal. Mina had no acne or male-pattern hair growth: She’s a Type D.

In Mina’s case, because she has many follicles in her ovary, we consider her to be potentially hyperandrogenic. Although this is one of the milder variants of PCOS, Mina would respond best to the specific treatments aimed at improving ovarian health and at enhancing ovulations.

As a general rule, women with Type D are not as insulin resistant as other phenotypes. They are more likely to have a normal BMI and normal waist circumference and often fall into the “lean” PCOS group (though it’s important to remember that lean women can be in any category).

When it comes to hormones, Type Ds have an increased LH to FSH ratio and an increased LH. This is may be why ovulation doesn’t happen regularly in this type. In many cases, women in Types A or B can move to Type D as their PCOS improves.

It’s important to note that studies have shown that women in all PCOS phenotypes, even Type Ds, display at least mild insulin resistance when challenged with glucose or carbohydrates. In each case, however, the degree of insulin resistance is quite different, and the treatment should be tailored to each woman’s needs, which we will go into great detail about very soon.

We are all unique. This is why the treatment that works for Sophia may not work for Elizabeth. Each woman with PCOS has a unique set of imbalances, or as I call them, “factors” that need to be addressed. This is where there may be some stumbling blocks in the current treatment of the disorder where a one-size–fits-all approach is often used. In this book, I hope to provide some tools that I have developed through my clinical experience in treating women step-by-step by their unique factors.

The following sections address the elements that can influence the PCOS phenotype that a woman has.

-Age

-Weight

-Environment

-Genetics

-Socio-Emotions

Young women naturally have more follicles in their ovaries and are more likely to be in a “cystic” phenotype. This is particularly the case for teenagers. As women age, the number of follicles in the ovary naturally decline. The newer threshold for twenty-six follicles does not apply to women under eighteen and over thirty-five for this very reason.

Fortunately, another main PCOS problem gets better with age: the levels of the androgenic hormones, such as testosterone and DHEA. As such, a woman may move from one of the more severe phenotypes, such as A, to one of the less severe phenotypes, such as C, as she gets older. So yes, the hormonal and reproductive problems of PCOS can actually improve as a woman gets older! That’s great, right?

It is, but there is some bad news, too: It’s important to know that the metabolic risks of PCOS, like cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, actually increase with age (see Appendix C).

Weight is one of the most important central factors that can determine the severity of PCOS. Weight gain (not including that of lean muscle) promotes insulin resistance, and insulin resistance is associated with more classic types, such as Type A or Type B. Weight loss, particularly loss of inches at the waist, can often easily move a woman to a milder phenotype. The opposite is also true: Gaining weight, especially around the waist, can move a woman from a “non-classic” type, such as C, to a “classic” type, such as A or B.

Studies show that women should aim for an abdominal circumference of thirty-five inches or less to achieve a milder phenotype. In those with smaller frames, such as Southeast Asian women, the recommended abdominal circumference to reduce insulin resistance is thirty-two inches or less.

Epigenetics are when the expression of your DNA changes in response to something in the environment. Yes, that’s right—your genetics are changeable! A few epigenetic associations have been made with PCOS: Most notably, animal studies have found that babies exposed to a high androgen environment (such as in Mom’s bloodstream) during pregnancy seem to be more prone to PCOS as adults. This may be in part why PCOS can be passed on in families.

With respect to the environment, if a woman is exposed to toxic xenoestrogenic products, such as plastics, PCBs, and other toxins (included in the environmental section in chapter 8), this may exacerbate PCOS hormonal imbalances and even induce PCOS in the next generation.

Some women are just more prone to more severe phenotypes of the condition than others, despite the changes they may make in their diet because of their lifestyle and hormonal factors. More and more evidence is being produced confirming that PCOS is a genetic disorder.

This may sound like an unusual category, but socio-emotional factors can actually contribute to the type of PCOS a woman has. It is unlikely that this alone can move her from one category to another, but there is good indication to suggest that stress and emotional health play a role in the severity of PCOS. Stress and mood are discussed in great detail in chapter 4. Women with PCOS often have higher-than-average cortisol levels, which can trigger a variety of hormonal imbalances.

Social factors, such as cultural and familial diet styles and the social influence of exercise, may influence the phenotype of a woman with PCOS through the types of activities that she does and the types of food that she eats. For example, in some cultures, including Southeast Asia and Latin America, carbohydrates are a mainstay of the diet, which leads to an increased predisposition to more classic forms of PCOS.

What I’m about to say may surprise you: It’s really important to know that the particular “type” is not what matters most. When it comes down to it, we all want to be healthier, happier, more fertile, and have great hormone balance and good skin, right?

From my experience, I’ve found that working through my system, step by step, using your unique PCOS factors, will help move you from a more severe type to a milder one, or even to a full reversal of your PCOS symptoms and reduction of risks. So, if you haven’t had an ultrasound of your ovaries and are not sure what type you really are, that’s OK. Keep reading: The best information to heal your PCOS is in the upcoming chapters.

Your PCOS factors may be very different than they were ten years ago, and five years from now, they will likely be different again. My goal is to look at PCOS not as a static disease but rather as a dynamic disorder that affects women’s bodies in unique ways as they pass through life.

My dream is for all women with PCOS to be treated as individuals and to have each woman’s case looked at with the detail that they deserve. A careful look at your unique characteristics gives you the power to begin the process of reversing your PCOS. So let us begin by looking at the first step.