| 9 | Linear Thinking Solving First Degree Equations |

P roblems that reduce to solving an equation of degree one arise naturally whenever we apply mathematics to the real world. It's not surprising, then, to find that almost everyone who studied mathematics, from the Egyptian scribes to the Chinese civil servants, developed techniques for solving such problems.

The Rhind Papyrus, a collection of problems probably used for training young scribes in Ancient Egypt, contains several problems of this kind. Some are simple and straightforward, others quite complicated. Here's a simple one:

A quantity; its half and its third are added to it. It becomes 10. In our notation, that is just the equation

(Keep in mind, though, that this kind of symbolism was still far in the future, as explained in Sketch 8.) The scribe is instructed to solve it just as we would: divide 10 by

Quite often, however, the problems in the Rhind Papyrus are solved by a very different method.

A quantity: its fourth is added to it. It becomes 15.

Instead of dividing 15 by 1¼, the scribe proceeds as follows. He assumes (or posits) that the quantity is 4. (Why 4? Because it's easy to compute a fourth of 4.) If you take 4 and add its fourth to it, you get 4+1 = 5. So we wanted 15, but we got 5; we need to multiply what we got (that is, 5) by 3 to get what we wanted to get (that is, 15). So we take our guess and multiply it by 3. Our guess was 4, so the answer is 3 x 4 = 12.

This method is known as false position: we posit an answer that we don't really expect to be the right one, but which makes the computations easy. Then we use the incorrect result to find the number by which we need to multiply our guess to get the correct answer.

Symbols make this easy to understand. The equation we're solving looks like Ax = B. If we multiply x by a factor, so that it becomes kx, we see that

So scaling the input by some factor scales the output by the same factor. This is what allows the method of false position to work; we use our guess to find the right factor.

Throughout antiquity, the method of false position was used to solve linear equations, including some pretty complicated ones. These range all the way from practical problems to more fanciful problems with a recreational flavor.

However, this method can only be applied to equations of the form Ax = B. If, instead, the equation were Ax + C = B, then it is no longer true that multiplying x by a factor causes B to change by the same factor, and this simple version of the method breaks down. We might try subtracting C from both sides, but that isn't always as easy as it sounds, because the expression on the left side might initially be very complicated, and finding the correct constant to subtract would require us to simplify it to the form Ax + C.

Instead, a way was found to extend the basic idea to equations of that type without any such algebraic manipulation. It is called the method of double false position. It seems to have been brought to Europe by Leonardo of Pisa, who called it the elchataym rule in his Liber Abbaci. Leonardo learned it in North Africa, where it was in common use. In Arabic, its name was hisab al-khata'yn, which means "computing from two falsehoods." It seems to have been created by Arabic-speaking mathematicians; the oldest surviving description of the method comes from Qusta ibn Luqa, who lived in what is now Lebanon in the 9th century.

Double false position is so effective for solving linear equations that it continued to be used long after the invention of algebraic notations. In fact, since it doesn't require any algebra, it was taught in arithmetic textbooks as recently as the 19th century. Here's an example,1 from Daboll's Schoolmaster's Assistant, published in the early 1800s.

A purse of 100 dollars is to be divided among four men A, B, C, and D, so that B may have four dollars more than A, and C eight dollars more than B, and D twice as many as C; what is each one's share of the money?

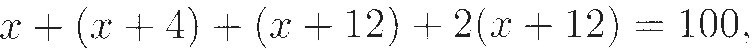

A modern approach to this would be to let x be the amount given to A. Then B gets x + 4, C gets (x + 4) + 8 = x + 12, and D gets 2(x + 12). Since the total is $100, we get the equation

which we then solve in the usual way.

Instead, here's what Daboll's recommends: Make a first guess, say that A gets 6 dollars. Then B gets 10, C gets 18 and D gets 36. (Notice that we don't need to work out how D's amount is related to A's to do this; we just go step by step.) Adding up the amounts gives $70 as the total; we're off by $30.

So we try again. This time we guess a little higher, say that A gets 8 dollars. Then B gets 12, C gets 20, and D gets 40, for a total of $80. That's still wrong, off by $20.

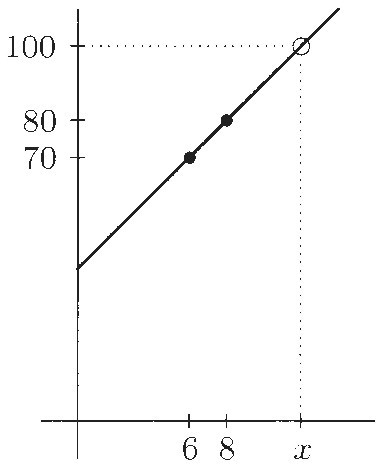

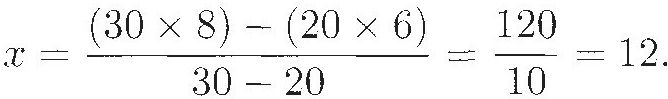

Now comes the magic. Lay out the two guesses and the two errors as in Display 1. Cross multiply: 6 x 20 is 120, and 8 x 30 is 240. Take the difference, 240 – 120 = 120. and divide by difference of the errors, in this case by 10. The right choice for the amount A gets is 120/10 = 12.

Display 1

This, Daboll's explains, is the procedure when the two errors are of the same type (both underestimates, in our case). If they were of different types, we would use the sum of the products and divide by the sum of the errors. (This is just a way of avoiding negative numbers.)

Modern readers usually find this method puzzling: Why does it work? Probably the best way to analyze it is to use some graphical thinking. No matter what the outcome of simplifying the left side of the equation will be something of the form mx + b = 100. So we can think of it like this: there is a line y = mx + b, and we would like to determine the value of x for which y = 100. To determine the line, we need two points, and the two guesses provide that for us: Both (6, 70) and (8, 80) are on the line. We want to find x so that (x, 100) is on the same line. (See Display 2.) The slope of the line is a constant; we can compute it as "rise over run" using the first and third points. We can also compute it using the second and third points, and the answers must be the same. Therefore, we see that

Display 2

Notice that the numerators are exactly the errors we had before. Now cross-multiply to get

which quickly simplifies to

that is,

This is exactly the same computation as in the method of double false position.

Of course, our way of understanding equations as lines is quite recent (it goes back only to the 17th century; see Sketch 16), and double false position is very old. But the actual slope of the line never needs to be computed. All we need to know is that two triangles are similar, so that we have a proportion involving the lengths of the sides. That is exactly how Qusta ibn Luqa explained the rule. The crucial insight is that the change in the output is proportional to the change in the input, which is the essence of what "linearity" is all about.

The distinction between "linear" and "nonlinear" problems is still useful today. We apply it not only to equations but also to many other kinds of problems. In linear problems, there is a simple relation — a constant ratio — between changes in the input and changes in the output, exactly as we saw above. In nonlinear problems, there is no such simple relation, and sometimes very small changes in the input may produce huge changes in the output. We still don't have a complete understanding of nonlinear problems. In fact, we often use linear problems to find approximate solutions to nonlinear ones. And the methods we use for solving those linear problems are based on the same fundamental insight that serves as the basis for the method of false position.

For a Closer Look: Because solving linear equations is relatively easy, few of the standard history books have sections specifically on that subject. There is a short discussion in [19] (pp. 31–35). For more on double false position, see [158] and [157].