| 17 |

Impossible, Imaginary, Useful Complex Numbers |

The standard way of introducing the complex numbers is to argue that we want to be able to solve all quadratic equations, including x2 + 1 = 0. The obvious reaction to that is: "Why would I want to solve that?" It's a good question.

During many centuries of the study of algebraic equations, mathematicians thought of them as a means for solving concrete problems. For "a square and ten things make thirty-nine," the square was pictured as a geometric figure, and the "things" were its sides. (See Sketch 10.) In this context, even negative solutions didn't make much sense. And if applying the quadratic formula led you to the square root of a negative number, this meant that your problem had no solution.

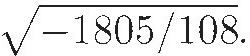

A good example of this can be found in Girolamo Cardano's The Great Art, published in 1545.1 He discusses the problem of finding two numbers whose sum is 10 and whose product is 40. He observes, correctly, that no such numbers exist. Then he points out that the quadratic formula leads to the numbers  and

and  He sees that, if he suppresses his disgust at such nonsense and computes with these expressions, he can show that their sum is indeed 10 and that their product is indeed 40. But he dismisses this kind of thing as a meaningless intellectual game. In another book, he says that

He sees that, if he suppresses his disgust at such nonsense and computes with these expressions, he can show that their sum is indeed 10 and that their product is indeed 40. But he dismisses this kind of thing as a meaningless intellectual game. In another book, he says that  is either +3 or –3, for a plus [times a plus] or a minus times a minus yields a plus. Therefore

is either +3 or –3, for a plus [times a plus] or a minus times a minus yields a plus. Therefore  is neither +3 or –3 but is some recondite third sort of thing."2

is neither +3 or –3 but is some recondite third sort of thing."2

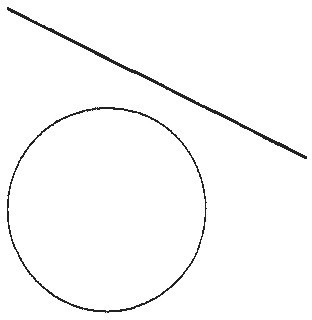

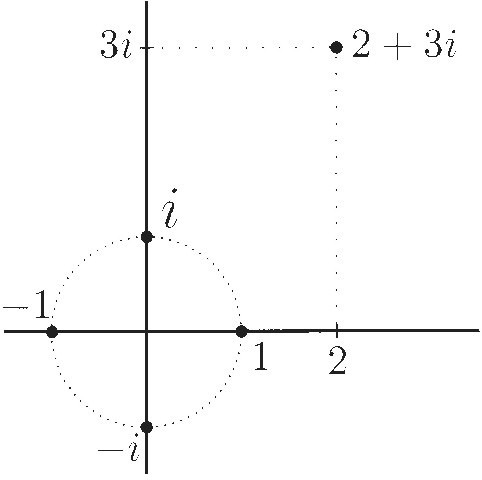

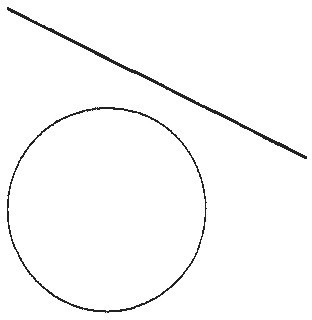

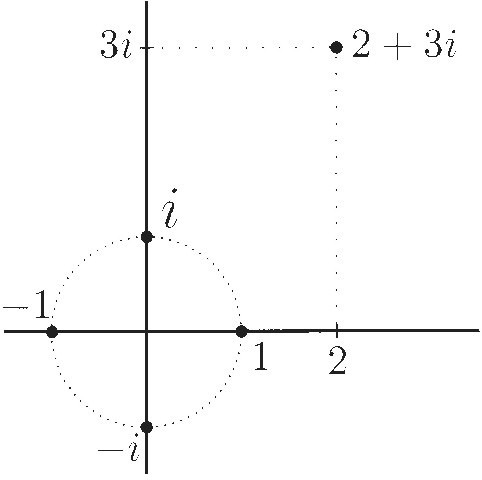

As various of his near-contemporaries noted, he had a point. For example, early in the 17th century, René Descartes pointed out that when one tries to find the intersection point of a circle and a line, one has to solve a quadratic equation. The quadratic formula leads to the square root of a negative number exactly when the line does not, in fact, intersect the circle, as in Display 1. So, for the most part, the feeling was that the appearance of "impossible" or "imaginary" solutions was simply a signal that the problem in question did not have any solutions.

Display 1

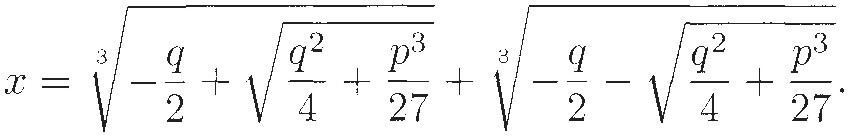

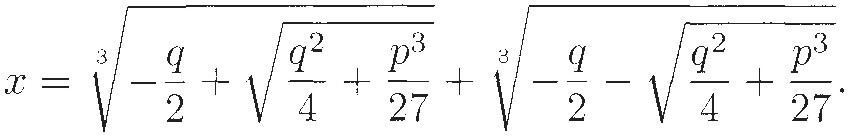

Even in Cardano's time, however, there were indications that life (mathematical life, at least) was not so simple. Cardano's greatest mathematical triumph was finding the formula for solving a cubic equation (see Sketch 11 for the story). For an equation3 of the form x3 + px + q = 0, Cardano's formula for the solution, recast in modern notation, was

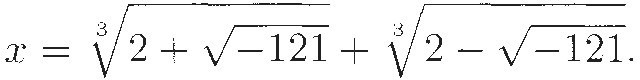

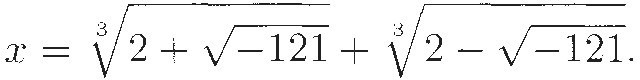

This gave a solution for many cubics, but in some cases there was a glitch. Suppose, for example, that the equation is x3 = 15x + 4. We rewrite it as x3 – 15x – 4 = 0 and apply the formula to get

Based on our experience with quadratics, the correct conclusion would seem to be that there is no solution. But if we try x = 4 we see that leaping to conclusions is a mistake: the equation does have a real root. (In fact, it has three real roots.)

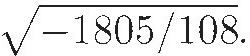

Cardano noticed this problem, but seems not to have known what to do about it. He mentioned it twice in his book. The first time, he said that this case needs to be solved using a different method to be described in another book. (In a later edition, he referred instead to a chapter describing tricks that might be used to solve certain equations.) The second time, he wrote4: "Solving y3 = 8y + 3, according to the preceding rule, I obtain 3." That must have puzzled any reader who tried to work it out "according to the rule." since the computation involves

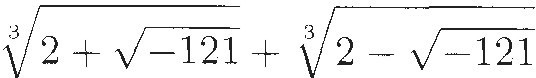

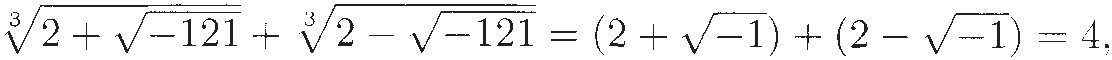

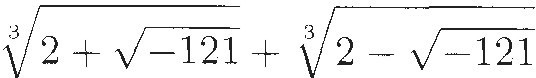

It was Rafael Bombelli who, in the 1560s, first proposed a way out of the quandary. He argued that one could just operate with this "new kind of radical." To talk about the square root of a negative number, he invented a strange new language. Instead of talking about  as "two plus square root of minus 121," he said "two plus of minus square root of 121,''5 so that "plus of minus" became code for adding a square root of a negative number. Of course, subtracting such a square root became "minus of minus." Since

as "two plus square root of minus 121," he said "two plus of minus square root of 121,''5 so that "plus of minus" became code for adding a square root of a negative number. Of course, subtracting such a square root became "minus of minus." Since  he also referred to this as "two plus of minus 11." And he explained rules of operation such as

he also referred to this as "two plus of minus 11." And he explained rules of operation such as

plus of minus times plus of minus makes minus;

minus of minus times minus of minus makes minus; and

plus of minus times minus of minus makes plus.

It's natural for us to read those as saying that

i times i is – 1;

–i times –i is – 1; and

i times –i is 1.

But we should be more careful. Bombelli was not really thinking of these "new kinds of radicals" as numbers. Rather, he seems to have been proposing formal rules that allowed him to transform a complicated expression such as

into simpler expressions. He showed that his formal rules led to

so

which is the solution of the cubic that started us down this path. Bombelli doesn't bother to look for any other solutions.

Bombelli's work showed that sometimes the square roots of negative numbers are needed in order to find real solutions. In other words, he showed that the appearance of such expressions did not always signal that a problem was not solvable. This was the first sign that complex numbers could actually be useful mathematical tools.

But the old prejudice persisted. A half century later, both Albert Girard and Descartes seem to have known that an equation of degree n will have n roots, provided that one allows for "true" (real positive) roots, "false" (real negative) roots, and "imaginary" (complex) roots. This helped to make the general theory of equations simpler and tidier, but the complex roots were still often described as "sophistic," "impossible," "imaginary," and "useless."6

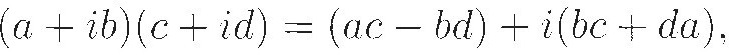

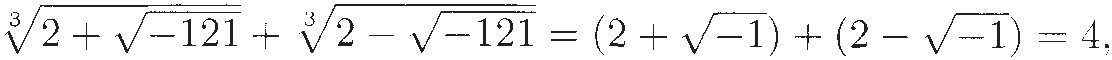

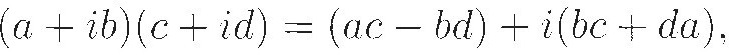

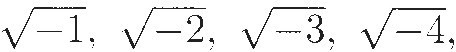

The next step seems to have come with the work of Abraham De Moivre in the early 18th century. If you look at the formula for multiplying two complex numbers,

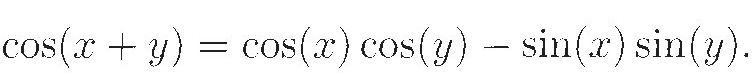

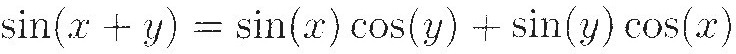

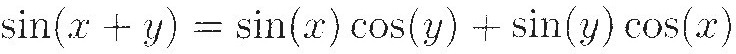

with just the right frame of mind, you may notice the similarity between the real part and the formula

The two cosines come together, as do the two real parts of the factors above, and so do the two sines and the two imaginary parts. The imaginary part of the product brings to mind

because sines and cosines are mixed, as are the real and imaginary parts of the factors. From there, it's not hard to get to De Moivre's famous formula:

(This is implicit in De Moivre's work even though it isn't stated there in this form.) A few years later, Leonhard Euler brought all the threads together when he discovered (using calculus) that

when x is measured in radians. With x = π in that expression we get

a famous formula that relates some of the most important numbers in mathematics.

By the middle of the 18th century, then, it was known that complex numbers were sometimes necessary steps towards the solution of problems about real numbers. It was known that they played a role in the theory of equations, and it was known that there was a deep connection between complex numbers, the trigonometric functions, and exponentials.

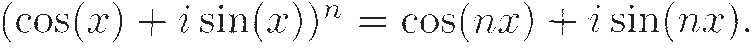

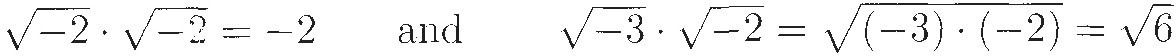

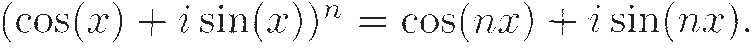

But there were still lots of problems. For example, Euler still got all tangled up in expressions like  A real radical has a definite meaning:

A real radical has a definite meaning:  means the positive square root of two. But, because complex numbers are neither positive nor negative, there is no good way to choose which square root we mean. So one finds Euler saying that

means the positive square root of two. But, because complex numbers are neither positive nor negative, there is no good way to choose which square root we mean. So one finds Euler saying that

without noticing that if he applied the second method to the first equation he would get the incorrect result

Reasoning by analogy often works, but not always!

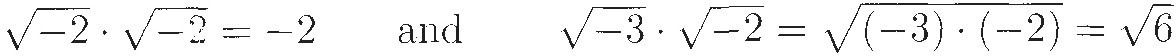

Although Euler used complex numbers a lot, he didn't resolve the issue of what they actually were. In his Elements of Algebra, he says

Since all the numbers which it is possible to conceive are either greater or less than 0, or are 0 itself, it is evident that we cannot rank the square root of a negative number amongst possible numbers, and we must therefore say that it is an impossible quantity. In this manner we are led to the idea of numbers, which from their nature are impossible; and therefore they are usually called imaginary quantities, because they exist merely in the imagination.

All such expressions as  are consequently impossible, or imaginary numbers, . . . and of such numbers we may truly assert that they are neither nothing, nor greater than nothing, nor less than nothing; which necessarily constitutes them imaginary, or impossible.

are consequently impossible, or imaginary numbers, . . . and of such numbers we may truly assert that they are neither nothing, nor greater than nothing, nor less than nothing; which necessarily constitutes them imaginary, or impossible.

But notwithstanding this, these numbers present themselves to the mind; they exist in our imagination, and we still have a sufficient idea of them. . . 7

This attitude typified that of most 18th-century mathematicians: complex numbers were basically useful fictions. Bishop George Berkeley8 likely would have retorted that all numbers are useful fictions; however, he was pretty much the only one to think along those lines at the time.

In the 19th century things began to be sorted out. R. Argand was one of the first one to suggest, in a booklet published in 1806, that one could dispel some of the mystery of these "fictitious" or "monstrous" imaginary numbers by representing them geometrically on a plane: the line segment from (0.0) to (x, y) corresponds to the complex number x +iy. Adding two complex numbers corresponded to the parallelogram law for adding vectors, and multiplication corresponded to a "scale and rotate" operation.

While many people found Argand's proposal interesting, it was not really used in a serious way until Gauss proposed much the same idea in 1831 and showed that it could be useful mathematically. It was also Gauss who proposed the term ''complex number" (by which he meant a number that has more than one component: a real part and an imaginary part). A couple of years later, William Rowan Hamilton showed that one could start with the plane, define the sum and product of ordered pairs in a convenient way, and end up with something identical to the complex numbers. Hamilton's approach completely avoided the mysterious "i"; it was just the point (0,1).

Display 2

Argand and Hamilton probably saw their ideas as one more application of complex numbers: One can use them to do plane geometry. But the concreteness of the plane helped remove some of the concerns about them. That was good, because complex numbers are incredibly useful. Euler and Gauss used them to solve problems in algebra and number theory. Hamilton used complex numbers to do physics. Cauchy and Gauss devised a version of the calculus which applied to complex numbers. This "complex calculus" turned out to be extremely powerful. In the hands of Riemann, Weierstrass, and others, it became a powerful mathematical tool that played a central role in both pure and applied mathematics.

The power of these discoveries was captured well by French mathematician Jacques Hadamard, who said that "the shortest path between two truths in the real domain passes through the complex domain." Even if we care only about real number problems and real number answers, he argued, the easiest solutions often involve complex numbers.

So why should we "believe" in complex numbers? Because they are so useful!

For a Closer Look: Most of the big historical reference books include discussions of the history of complex numbers. For more detail, see chapter 3 of [70]. See [122] for an invitation to imagine what complex numbers might be and [131] for a more technical account of "the story of  The article [112] offers an interesting discussion of what exactly Bombelli thought about his "radicals of a new kind."

The article [112] offers an interesting discussion of what exactly Bombelli thought about his "radicals of a new kind."

1 See Sketch 11 for more on Cardano.

2 From Ars Magna Arithmeticae, problem 38, quoted in [25], p. 220, note 6.

3 We give equations and formulas in modern notation; see Sketch 8 for the story of algebraic symbolism.

4 See [25]. p. 106

5 The Italian is piu di meno.

6 For an even longer list of such descriptions, see [77], section 9.3.

7 From [51], p. 43.

8 Famous for his critique of calculus; see p. 47.

and

and  He sees that, if he suppresses his disgust at such nonsense and computes with these expressions, he can show that their sum is indeed 10 and that their product is indeed 40. But he dismisses this kind of thing as a meaningless intellectual game. In another book, he says that

He sees that, if he suppresses his disgust at such nonsense and computes with these expressions, he can show that their sum is indeed 10 and that their product is indeed 40. But he dismisses this kind of thing as a meaningless intellectual game. In another book, he says that  is either +3 or –3, for a plus [times a plus] or a minus times a minus yields a plus. Therefore

is either +3 or –3, for a plus [times a plus] or a minus times a minus yields a plus. Therefore  is neither +3 or –3 but is some recondite third sort of thing."2

is neither +3 or –3 but is some recondite third sort of thing."2

as "two plus square root of minus 121," he said "two plus of minus square root of 121,''

as "two plus square root of minus 121," he said "two plus of minus square root of 121,'' he also

he also

A real radical has a definite meaning:

A real radical has a definite meaning:  means the positive square root of two. But, because complex numbers are neither positive nor negative, there is no good way to choose which square root we mean. So one finds Euler saying that

means the positive square root of two. But, because complex numbers are neither positive nor negative, there is no good way to choose which square root we mean. So one finds Euler saying that

are consequently impossible, or imaginary numbers, . . . and of such numbers we may truly assert that they are neither nothing, nor greater than nothing, nor less than nothing; which necessarily constitutes them imaginary, or impossible.

are consequently impossible, or imaginary numbers, . . . and of such numbers we may truly assert that they are neither nothing, nor greater than nothing, nor less than nothing; which necessarily constitutes them imaginary, or impossible.

The article [

The article [