The realization that we live in a quantum world came on slowly, with a discovery here and there that didn't seem to fit with the viewed-to-be-absolutely-correct and universally accepted classical physics of the time. We now examine these findings in the manner of a Sherlock Holmes, spotting clues and piecing them together to solve some great puzzle. As we move from clue to clue, I'll be providing boxed biographies and histories of the personalities involved in the search, and I'll also include bits of background on the physics, in indented paragraphs, so that the meaning of the clues can be understood. The first clue, what started it all, was examined by Max Planck.

THE QUANTUM (A RESULT OF THE FIRST CLUE)

Two chairs to the left of Einstein in the first row in Figure 1.1 is Marie Curie, and further next to her, second from the left, is Max Planck, who in 1900 started the quantum revolution with his explanation of the radiation of heat and light. At the time, the center of work on theoretical physics was in Germany, and in all of Germany there were only sixteen professors of theoretical physics. It was a small community. Most of the advancements in theoretical physics would come from men who were in their twenties, many of them in their early twenties. Planck was over forty.

Recognizing that advantages were to be gained through the development of products based on new learning, the German government, starting in 1887, built on the outskirts of Berlin the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology (PTR), which at that time was the best equipped and most expensive laboratory in the world. The need to develop a better light bulb drove research on the radiation of heat and light from hot objects. New experimental results early in 1900 showed that the classical theory describing radiation was flawed (the first clue). Planck, who by this time was the senior physicist at Germany's (foremost) University of Berlin, decided to work on the problem.

Fig. 2.1. Max Planck. (Image from AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.)

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck was born on April 23, 1858, and was brought up in a well-to-do and cultured family. His father, descended from clergymen, had become a professor of constitutional law in Kiel, which was then a part of Danish Holstein. Max was a good student, excelled as a pianist, and could have pursued a career in the arts, but he followed instead a curiosity for physics. Professors at the time of his schooling were state supported, but theoretical physics had not been established as a field of study. After doctoral studies with noted scientists at various universities and with no suitable position available, Max in 1880 began teaching as a privatdozent (a lecturer who was paid directly by his students and given a place to teach, but without a professorial position at the university). Eight years later, at the age of thirty, he was asked to succeed Gustav Kirchhoff in the now-established professorship for theoretical physics at the University of Berlin.

By late 1900 Planck had devised a mathematical expression that perfectly described the new experimental results on radiation, but it involved a wrenching rejection of classical ideas that he and everyone else held strongly. He was deeply troubled by the implications of what he had just found.

As background to understanding the strangeness of Planck's achievement and, as it turns out, much of quantum mechanics, I provide the following brief history and introduction to what was known at the time about light and heat radiation.

Isaac Newton, in the mid sixteen hundreds, had theorized that light was composed of particles, which he called corpuscles. This view was overturned by a bold twenty-seven-year-old Thomas Young, who in 1801 dared to oppose the views of the great Newton. Young found that light of any particular color impinging on two slits in a barrier would undergo a process of diffraction and interference that occurs only with wavelike entities. I describe this process here by analogy to what happens in water.

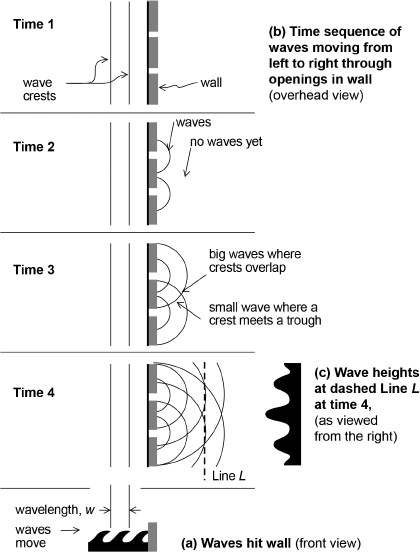

Figure 2.2 illustrates the diffraction and interference of waves of water as they impinge on two openings in a wall with water on both sides. Note that waves do not really travel; the water molecules mainly move up and down: water rises to a peak at one position followed by water a little farther ahead rising to a peak moments later, much like the human wave produced by football fans in successive sections of a stadium when they raise then lower their arms. But unlike this human wave, which propagates around the stadium, the waves in our figure propagate from left to right.

Now suppose that the wave (of crest-to-crest wavelength w) impinges upon the wall as shown in (a). Part of each wave will pass through the two openings and emerge on the other side, diffracting (spreading outward) from each opening as shown in (b) at Time 2 and progressing as shown through Time 4. The circular set of diffracted waves emerging from one opening will interfere with the set emerging from the second opening. What results is an interference of crossing waves, illustrated by the crossing of the lines representing the crests of the waves at Time 3 and the interference pattern of wave heights shown in (c) at the position of the dashed line L at Time 4. Where crest crosses crest, the water rises to the combined height of both waves. Where trough crosses trough, the water sinks to the combined depth of both troughs. Where trough crosses crest, there tends to be a cancellation and the water does not rise or fall much, if at all.

Fig. 2.2. Diffraction and interference of waves in water: (a) Waves of crest-to-crest wavelength w propagate from left to right, (b) diffract through two openings to interfere as described at Time 3, and (c) create the interference pattern of wave heights at line L as shown at the bottom right. (Modified, with permission, from Fig. 5.1 of Big Bang, Black Holes, No Math, by David Toback. Copyright © 2013 by David Toback.)

This was for water, but what about for light? The interference pattern shown at the right of this figure is similar to the pattern for light that was presented by Young to the Royal Society in London to show how light behaves. The argument was that no particle could pass through both slits and interfere with itself. And Young's experiments, measuring the intensity of light in the interference region, demonstrated just the sort of pattern that we see with the interference of waves in water.

It would seem that the conclusion had to be that light was composed of waves, not particles. But at the time, this conclusion was not accepted.

According to Kumar, “When he first put forward the idea of interference and reported his early results in 1802, Young was viciously attacked in print for challenging Newton. He tried to defend himself by writing a pamphlet in which he let everyone know his feelings about Newton: ‘But much as I venerate the name of Newton, I am not therefore to believe that he was infallible. I see, not with exultation, but with regret, that he was liable to err, and that his authority has, perhaps, sometimes even retarded the progress of science.’1 Only a single copy was sold.”2

By Planck's time, the situation had reversed, and it was hard to get anyone to believe that light was anything but a wave. All on the basis of sound theory and experiment. But, as you will soon see, new evidence to the contrary began to build.

In the next few paragraphs we examine how it is that waves are characterized. This may seem like detail, but it will be very useful later on.

Planck's analysis, one hundred years after Young's experiments, contradicted the firmly held classical view of light as a wave. To fit his theory to the measured radiation data, Planck required that light or heat radiation be released in discrete particlelike packets of energy, which he called quanta. And to make his analysis work, the energy of each quantum was defined as a constant (later called Planck's constant, represented by the symbol h) times the frequency of the light: in simple shorthand, Equantum = hf. So, the lower the frequency (that is, the longer the wavelength of light, tending toward red in color and the infrared), the lower the energy of the associated quantum. And, conversely, the higher the frequency (that is, the shorter the wavelength of the light, tending toward the violet and ultraviolet), the higher the energy of each quantum. (As you will come to see, Planck's constant is as fundamental to physics as the number π is to geometry and mathematics.)

If you measure the distance crest-to-crest (the wavelength, w) and count how many wave crests pass by the wall in a given time, you have the wave frequency, f, in waves per second (cycles per second, where each cycle is the passage of a crest and a trough and then a crest again). Then you can calculate the speed of wave propagation, labeled here as S, by multiplying w times f. In scientific shorthand we write this as S = wf.

By 1900, light and heat radiation had come to be recognized as just two of many wavelength ranges of electromagnetic waves, the only difference between them being their wavelengths. Heat radiation is of longer wavelength than light, into the infrared, and therefore not seen. All electromagnetic waves propagate at “the speed of light,” c, approximately 3 × 108 meters per second. So, for electromagnetic waves our formula is specifically c = wf. (Dividing both sides of this equation by either w or f, which still keeps it in balance, gives us c/w = f and c/f = w, which are handy formulas for calculating either f or w if the other is known. If one knows w, divide it into c to get w. If one knows f, divide it into c to get f. Stated another way, if you specify either w or f, it's as if you have specified both properties. Sometimes it's more convenient to discuss an aspect of physics using w, at other times it's more convenient to use f.)

(A very good description of the classical view of electromagnetic waves is provided in Appendix A. If, for now, you'd just like to get a sense of the many types of waves and rays that compose the electromagnetic spectrum, you might only glance at Figure A.1(c) and then view the spectrum of wavelengths described at the left in Figure A.2.)

Nothing in Planck's classical understanding of physics would allow light and heat to be radiated in discrete chunks of energy. Light had been universally thought of as being wavelike, with any amount or intensity possible. That is, light in Planck's earlier experience could be made dimmer and dimmer without limit. At any frequency it would be available in any amount of energy, with no minimum. Now, to fit the radiation data, he had postulated a light quantum. How would this (particlelike?) indivisible quantum diffract through two slits and interfere with itself, as Young had demonstrated?! It seemed impossible! And Planck indeed believed that it was impossible. (He was not about to return to Newton's ideas of corpuscles, which had been shown to be wrong!)

Nevertheless, Planck presented his results, passing off the apparent contradiction between the quantum and classical ideas as something to be resolved later on. For more than ten years afterward, Planck labored to achieve that resolution but couldn't do it. He gave his quanta physical basis, imagining that the light was emitted by a collection of microscopic electric oscillators operating at different frequencies and housed on the surface of the emitting hot materials. But, to fit experimental results, he was always stuck with having to make the assumption of discrete chunks of energy. He wouldn't go so far as to say that light itself was quantized, only that the transfer of energy between light and substances occurred in quantum units. And he resisted for the rest of his life the revolution in physics that his idea of the quantum produced. But he was right in what he had presented in 1900, and in 1918 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics3 “in recognition of the services he rendered in the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta.”

THE PHOTOELECTRIC EFFECT (THE SECOND CLUE)

The beginnings of a radical break away from classical physics came in 1905 with Einstein's analysis of the photoelectric effect. With it he began to transform the quantum from Planck's item of mathematical convenience to the basis of an entirely new concept of physics that would eventually (but not soon) gain acceptance.

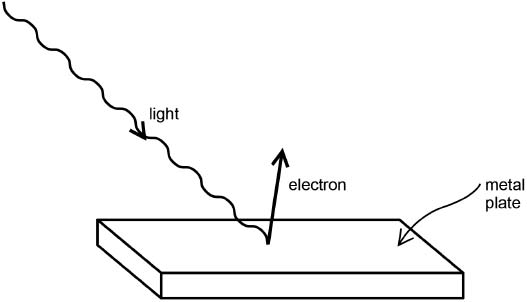

In the photoelectric effect, light shining on a metal, under the right conditions, causes electrons to pop out of the metal's surface, as sketched in Figure 2.3. No matter how intensely the light might shine, unless the wavelength of the light was shorter than some particular value characteristic of each metal (so that the energy of the light quantum was greater than a corresponding particular value), no electrons would be knocked free from the metal. Yet some electrons would pop free even with very little light radiation, as long as the wavelength of the light was short enough (energy of the quantum high enough). There was no classical explanation for these results!

Fig. 2.3. The photoelectric effect: Light of sufficiently short wavelength (sufficiently high photon energy) knocks an electron free from a metal plate.

We'll describe Einstein's analysis of this effect shortly. But first, realize that Einstein was just twenty-six years old at the time of this analysis, and he was supporting his wife and young son by working as a patent examiner for the Swiss government. We take a moment now to relate the twists and turns in Einstein's early life that may have prepared him to tackle this analysis and prepare him to create some of the most profound and important ideas and explanations of modern physics.

Albert Einstein was born on March 4, 1879, in Ulm, Germany, into a secular Jewish family. His sister, Maja, came along two years later. It took him a long time to learn to speak, and when he did so it was after first constructing and examining sentences in his head. It was not until the age of seven that he began to speak normally.

Albert's interest in the workings of the physical world is said to have begun at the age of five when he became intrigued by the unseen forces that moved the needle of a compass. By the time he was six, his family had moved to Munich, where his father and uncle opened an electrical business. And so he was exposed to electrical machines and concepts of electricity and magnetism. As a boy he developed a preference for doing things by himself, demonstrating much patience and tenacity in solitary pursuits; for example, at the age of ten, he built card houses to as high as fourteen stories.

As a preteen, Einstein had become enamored of religious studies. But then he totally rebelled at what he considered deception after being exposed to the ideas of Euclid, Kant, Spinoza, and the Popular Books on Natural Science by Aaron Bernstein. This through the visits of Max Talmud, a penniless twenty-one-year-old Polish medical student, who every Thursday was invited to join the Einstein family for dinner.

The family business manufacturing direct-current dynamos and meters initially prospered, to the point that the brothers were installing power and lighting networks, including the lighting for the 1885 Munich Oktoberfest. But they eventually lost out to larger companies, particularly to Siemans's alternating current systems, and in 1894 the brothers relocated the business to Milan. Albert, now fifteen, was left behind with distant relatives to complete the remaining three years of secondary school. But he was worried about compulsory military service in militaristic Germany if he became seventeen as a German citizen. (Though he would later become a pacifist, it was not service, but the militarism of Germany that he hated.)

Albert found an excuse to leave school, joined his family in Milan, and renounced his German citizenship. On finally4 passing entrance exams to the Swiss Polytechnic School (ETH) in Zurich, he elected a course that would qualify him to be a schoolteacher of math and physics. He was the youngest of six such students entering in October 1896. Eventually he fell in love with one of them, a Hungarian Serb of good family, Mileva Maric´, who in January 1903 would become his wife.

Things were at first good at school, but then came some very difficult times.

Einstein enthusiastically explored interesting questions in physics with Mileva and friends, but he managed to antagonize his professors by doing things his own way. He skipped classes, borrowed notes to study, and barely graduated. Mileva failed final exams and returned home. Einstein, without good recommendations from his professors, could not get a job. Unlike many of his classmates, he was not offered an assistantship at the ETH. And both of their families were opposed to the couple getting married, especially Einstein's mother.

Albert eventually managed to get into a doctoral program at the prestigious University of Zurich, but by then his father's business was failing. Albert earned some money tutoring. Mileva had become pregnant, and she failed her exams, again. In a difficult delivery at home, she gave birth to a baby girl whom they named Lieserl. Albert wrote loving and supportive letters, but he had no money to travel. He would never see his daughter, who is presumed to have been given up for adoption. He hid in pursuit of his physics.

Finally, in June 1902, with the help of friends, Albert found a job, starting work at the Swiss patent office as technical expert third class, but with a pay twice what he would have made as an assistant at the ETH. Now, with a secure income, he obtained his father's (deathbed) permission and married Mileva at the Bern City Hall in the presence of two of friends. He and Mileva are shown some years later in Figure 2.4. In May 1904, they began a family anew, when their first son, Hans Albert, was born.

Fig. 2.4. Albert Einstein and his wife, Mileva Maric´, in 1912. (Image from ETH-Bibliothek Zurich, Bildarchiv.)

Einstein's work at the patent office required that he be skeptical of all that he read. This perhaps gave him an uncommon grounding for seeking out flaws in classical physics. And the atmosphere of the patent office served well for critical thinking. Though he worked a six-day, forty-eight-hour week, he was able to use the time at his desk to both do well at his patent work and, without interference, explore the fundamental laws of physics. But it wasn't just the quiet of the patent office that allowed him to function. Einstein showed tremendous powers of concentration, and he was able to work amidst the chaos of a busy home or withdraw into his thoughts in the middle of a social gathering.

(This brief biography has necessarily been limited. To get a better feel for Einstein, his struggles, triumphs, virtues, and failings, I highly recommend that you read from page 102 of The Human Side of Science, by Arthur Wiggins and Charles Wynn [Reference KK]. Complementary observations are offered in Quantum, by Manjit Kumar [Reference K].)

Now, as further background to Einstein's analysis of the photoelectric effect, I describe what in 1905 was understood of the electron:

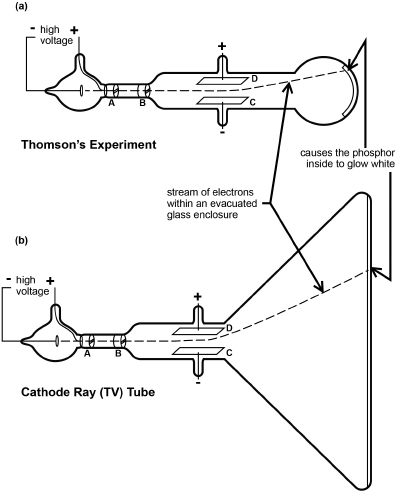

The discovery of the electron in 1897 started with the observation of what had been called “cathode rays.” If a large voltage was created between two wires that fed into a partially evacuated glass tube, electricity would flow through the gap between the wires. This would cause the small amount of air still trapped in the tube to glow, marking the path of what were called “rays.” By studying these rays, J. J. Thomson in 1897 determined that they were actually streams of small particles of negative charge, each less than one-thousandth the mass of the hydrogen atom. Applying the label that Newton had used much earlier for particles of light, he called the particles corpuscles, but they later came to be called electrons.

Thomson's illustration of the glass-enclosed apparatus that he used for his experiments is shown in Figure 2.5(a).

Fig. 2.5. (a)Thomson's apparatus for discovery of the electron. An evacuated glass enclosure houses (at left) a hot cathode at negative voltage from which is drawn a stream of electrons (dashed line) to and through the + voltage ring and deflected by + and – voltage plates at D and C to hit and glow a phosphor screen at the right. (b) Concept of an early type of cathode ray TV tube.

In his experiment, electrons (which always have a unit negative charge) are attracted and accelerated in vacuum within a glass enclosure from the metal cathode (C) toward the highly positive voltage brought by a wire to the region of the slits (A) and (B) that would allow only a ribbon-shaped beam of particles to pass. Those electrons passing through the slits are carried by their momentum to impact the phosphor on the inside of the front of the tube at the far right, causing it to glow. By applying smaller + or – voltages across the plates (D) and (E) the electrons (each traveling a path like that shown by the dashed line) would be deflected upward or downward. Because the charge on the electron is negative, it would be attracted to the positive plate and repelled from the negative one (which is what happened).

Because electromagnetic waves are not expected to be deflected by electric fields at all, Thomson was able to conclude that the rays observed were caused by a charged particle. He correctly assumed that this was the smallest charge to be found in nature, and it would be assumed to be nature's basic unit of charge. From the deflection and the voltage causing it, he was able to calculate the ratio of the electron charge to its mass. Comparing this ratio to the ratio of charge to mass for the hydrogen nucleus (later found to consist of one proton of positive unit charge), Thomson was able to roughly estimate the electron's mass (actually about 1/1,800 the mass of the proton).

Einstein followed after Planck in examining theoretically the radiation of heat and light from hot bodies. But he used a statistical approach and a different model. He was able to derive Planck's formula for the energy of the quantum. And he concluded that it was the light itself that was quantized, not the hypothetical oscillators in Planck's model. He applied this concept of light quanta to explain the photoelectric effect.

Einstein reasoned that the light consisted of many quanta of energy, and that even one single quantum of light, if it had a short-enough wavelength (that is, if it had sufficient energy), would pop loose one electron as shown in Figure 2.3. In that sense, the quantum might be viewed as a “particle” of light. One light particle of sufficiently high energy, that is, of sufficiently short wavelength, pops loose just one electron.

Now I digress briefly to provide a glimpse of a couple of the products that resulted from Thomson's science.

It was eventually found—in more completely evacuated tubes of other geometries—that electrically heating the cathode to the point where it would glowred-hot would reduce the voltage needed to induce electron flow. And, without the deflecting plates, slits, and phosphor, it was found that a very small voltage across an additional wire between the cathode (C) and anode (A) could cause large changes in the flow. These “tubes” would allow the amplification of small electrical signals and the invention of a host of devices that we now label as “electronics.” Much later still, in the 1950s, it was found that amplification could be obtained in tiny composites of solid materials. This introduced “solid-state electronics,” quantum devices eliminating most* of the need for the cumbersome tubes and eventually leading to the production of integrated circuits and devices within single “chips,” as described briefly in Chapters 17 and 23.

(*Among the holdouts were the large, heavy “cathode-ray tubes” that until recently preceded modern flat-screen TVs. One such tube is shown schematically in Figure 2.5(b) as a much larger phosphor-screen version of Thomson's apparatus. A spaghetti-thin stream of electrons in this tube is directed by sideways or vertical plates and voltages to impact the front of the tube at various locations, causing a glow of the phosphor that is seen through the glass from the outside of the tube. By changing plate voltages to cause the stream to scan rapidly in lines across the front of the tube, while at the same time turning the electron flow on and off, light and dark regions are produced to make a picture that persists momentarily and is then quickly changed by the immediately following scan. In this way, small changes in the picture are made to occur rapidly and seamlessly to produce what we view on TV as motion. This is basically what occurs in older black-and-white TVs. Further innovations produced color.)

The quantum now explained two phenomena in defiance of the laws of classical physics. And Einstein, unlike Planck, would champion the quantum view. But there were still many questions that needed answering.

Because of diffraction and interference, light was considered to be wavelike. But now, with the photoelectric effect, light was also shown to behave like a bunch of quantum particles. (Back to “corpuscles”?) How does one get interference from a particlelike light quantum? How does a light quantum, an indivisible chunk of energy, go through one slit (with reference to the water analogy of Figure 2.2), and then interfere with itself once it has passed through the slit, to form the interference pattern that Young had observed?!

In a lecture in 1909 before an audience of the leading German physicists of that time, Einstein presented a mathematical model that suggested that light would have the properties of both a particle and a wave, what would later come to be called wave-particle duality. Planck, who chaired the session, politely thanked him but disagreed, stating what most physicists then still believed: that quanta were only necessary in considering the exchange of energy between matter and radiation, and that it wasn't necessary to treat light itself as a particle or actually made up of quanta.

Einstein's paper on the photoelectric effect, his paper on special relativity, and a third paper on Brownian motion (as evidence for the existence of atoms and molecules) were among five papers that he published in his 1905 “miracle year.” Based on this and much subsequent work, Einstein would in 1921 be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.”

A QUANTUM THEORY OF SOLIDS (MORE EVIDENCE)

In 1909, after a prerequisite year working as a privatdozent at the University of Bern, seven years after he'd joined the patent office, Einstein finally acquired a position equivalent to assistant professor of theoretical physics at the University of Zurich. There he showed a relaxed teaching style, encouraged questions, and soon gained the respect of his students. And he turned his attention to a completely new area of physics.

Many solid substances consist of crystals of atoms stacked in three-dimensional arrays. What we sense as temperature is the heat-induced jostling of atoms about their crystalline lattice positions. The more extreme the jostling, the higher the temperature. (When we touch a hot object, that jostling is transferred to the atoms in our fingers. If the jostling is extreme, the cells in our fingers are damaged and burns result.) If a solid like a metal gets hot enough, the jostling becomes so extreme that the atoms lose track of their lattice positions and wander around, causing the solid to melt.

Einstein assumed that the jostling could be modeled as a superposition of mechanical oscillators of different frequencies, analogous to weights on springs. As Planck had done for light radiation, Einstein also assumed that only certain quantized frequencies would be available for the oscillations. He derived a formula for the manner in which temperature would rise as heat was added to the solid. That is, he calculated what is called the solid's heat capacity.

For two years, Einstein's theory received little attention. But then Walter Nernst, an eminent physicist at the University of Berlin, succeeded in accurately measuring the heat capacities of solids at low temperatures. The results exactly matched the predictions of Einstein's calculations!

Einstein was now beginning to be noticed. He was offered, and he accepted, a professorship at the German University in Prague; and he moved there in 1911 with Mileva and his sons Hans Albert, now six, and Eduard, almost one. He was also invited to the First Solvay Conference, held in Brussels, to be the prestigious last speaker of eight who would make presentations before twenty-two of the leading physicists across Europe. The conference addressed questions regarding molecular and kinetic theories (i.e., theories about the motion of particles). He would speak on the heat capacity of solids. It was the first such conference to involve a quantum concept (but light quanta were not on the agenda).

Einstein had succeeded admirably, but the years from 1908 through 1911 were especially hard on Mileva. While privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer) at the University of Zurich, Albert still worked his full-time job at the patent office. When a year later he acquired his assistant professorship, he had a heavy teaching load, and he became popular with the students who would surround and follow him to the cafés in Zurich to discuss physics. In July 1910, Mileva gave birth to their second child, Eduard, who unlike Hans Albert was very fussy. Mileva looked after two children, and she felt neglected by a very busy husband. There were also misunderstandings. And later she was very unhappy with living in Prague. Albert also longed to return to Zurich. With the aid of Marcel Grossmann (fellow student and friend, now dean of mathematics and physics), he obtained an appointment as a master physicist to the renamed Swiss Federal Technical University (ETH), where he had earlier been unable to find a job even as an assistant.

THE QUASI-CLASSICAL QUANTIZED BOHR MODEL OF THE ATOM (A SOLUTION OF SORTS)

A major breakthrough came in 1911 from the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, seen to the far right of the middle row in Figure 1.1. Bohr would become the driving force in integrating the various experimental and theoretical contributions of the early quantum theory to provide a description of the atom and the elements. Later, through his Institute for Theoretical Physics and his insights and communications with other leaders in the quantum field, he would become the foremost proponent and spokesman for the Copenhagen interpretation of the developing quantum mechanics.

To understand the magnitude of Bohr's accomplishment, we first provide a sketch of what was known of the atom at the time.

In 1903, just six years after his discovery of the electron, J. J. Thomson proposed what was called the “plum pudding” model of the atom. His model assumed that the atom of any element would be composed of thousands of (negatively charged) electrons embedded in a ball of massless, spread-out, comparable positive charge. Later he would revise his model to include fewer electrons and assume that most of the mass was in the region of positive charge. At the time, many eminent physicists and chemists still believed that there were no such things as “atoms.”

Ernest Rutherford, soon to become Bohr's mentor, would develop a different model for the atom.

Rutherford was one of twelve children raised in a working-class family in New Zealand. Through a series of scholarships Rutherford had come to Cambridge in 1895 to study under Thomson, initially continuing work that he'd begun earlier to devise ways of detecting radio waves, and then examining the radiation emanating from radioactive uranium. With Thomson's high recommendation, he was appointed in 1898 to professor at McGill University in Montreal. There he worked with radioactive elements. In 1901 with fellow professor Frederick Soddy he discovered that one radioactive element could transform into another through the radiation of alpha particles, later recognized as helium nuclei. (It was Rutherford who coined the term half-life to describe the time over which an element would lose half of its radioactivity.) For this work he would in 1908 be recognized with a Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the offer of a promotion to professorship at the University of Manchester. Soddy would get the prize two years later.

At Manchester, Rutherford assigned his assistant Hans Geiger (yes, of the Geiger counter) and an undergraduate, Ernest Marsden, to examine the constituency of the atom by bombarding metallic foils with helium nuclei. When these heavy particles sometimes bounced back rather than penetrating through, Rutherford concluded that the atom had a yet heavier nucleus, which his calculations showed to be 100,000 times smaller than the atom. He devised a “planetary” model of the atom, of tiny electrons in large orbits circling this tiny but heavy nucleus, to create an atom of the overall size inferred from experimental measurements. But there was one major, major flaw in his model (to be described shortly). He decided to ignore it, and at a meeting in Manchester in March 1911 he put forth his ideas. Because of this flaw, the reception was cool, and later that year, at the First Solvay Conference, his planetary model wasn't even discussed.

The problem was that the planetary model ran counter to a demonstrated and well-known characteristic of charged particles: if they are accelerated, they radiate energy. Like the planets, the electron in its orbit undergoes acceleration, but because the electron has net electrical charge, Rutherford's electron in orbit would be expected to radiate energy, slow down, and in some manner collapse. The atom would not be stable. And this, of course, was not (and is not) observed.

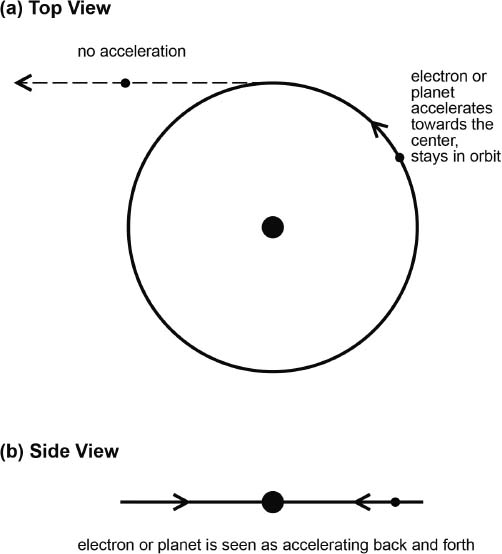

The Acceleration of an Object in Orbit

By looking sideways at planets or electrons in hypothetical circular orbits, as shown in Figure 2.6(b), one can see that the electron accelerates. Seen this way, the electron (or planet) would appear to be oscillating back and forth, from left to right and back again, accelerating first in one direction and then in the other. Even viewed from the top, as shown in Figure 2.6(a), the electron (or planet) is seen always to be accelerating toward the nucleus (or the sun) in its orbit; otherwise, its momentum would just carry it off to infinity in a straight line.

According to everything that we know (and that was known at the time) accelerating electrons, or any accelerating charged objects, will continuously broadcast out electromagnetic energy. (That is how radio waves are produced: by accelerating billions of electrons back and forth or up and down at the frequency at which transmission is desired. But, unlike the electron in an atomic orbit, electrons in a broadcast antenna are continuously resupplied with energy at a rate of so many kilowatts of broadcast power, as is often advertised.) So, according to what was known in the physics community, the electron in Rutherford's orbit would be broadcasting out energy. This would cause the electron to spiral down and collapse the atom. His model would not be viewed as valid.

Fig. 2.6. (a) A planet in orbit around the sun follows a circular or elliptical (not shown) path because the gravitation of the sun's mass continually attracts it (accelerates it) toward the sun. Otherwise, the planet would travel in a straight line (shown dashed). An electron, attracted to the positive charge of a proton, will behave in a similar manner. (b) In this side view, the planet or electron would appear to be accelerating back and forth (right and left).

Bohr, like Einstein, had a nose for the importance of areas of physics showing problems and contradiction. He had become convinced that Rutherford's model of the atom was basically right, and he decided that the answer to the problem of radiation must somehow be connected to the (still mainly disbelieved) ideas of Planck and Einstein on the quantum.

Niels Henrik David Bohr was born on October 7, 1885. He enjoyed a privileged childhood in Copenhagen: his mother's family was wealthy in banking and influentia in politics; and his father was the distinguished professor of physiology at Copenhagen University. Niels and his older sister and younger brother were exposed to intellectual discussions during regular visits of writers, artists, and scholars of all sorts to the Bohr home. Niels was athletic and excelled in mathematics and science. In 1903 he enrolled to study physics at Copenhagen University, receiving a master's degree in 1909 and a doctorate in 1911, with a dissertation on the theory of metals.

In September Bohr left on a one-year postdoctoral scholarship to work with the (by then) Nobel laureate J. J. Thomson at Cambridge. But there he found it difficult to get attention and communication from Thomson, and after eight months he arranged instead to join Rutherford in Manchester for the rest of his scholarship year, despite the fact that Rutherford was doubtful of theorists. (That Bohr played soccer apparently helped him to fit in once he got there.)

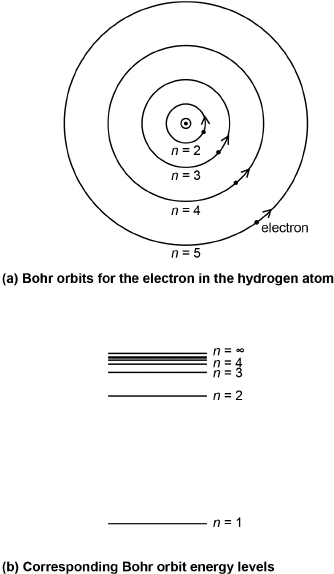

Following his instincts, Bohr postulated that the electron in an atom could only be found in certain discrete circular “stationary” orbits, and that the electrons would be stable in these orbits and not radiate energy as classical physics required. He had no proof, no justification, except, eventually, that it would work and that he could use his model to quantitatively explain much as-yet-unexplained phenomena.

In support of his postulate, Bohr fastened on an idea published earlier that year by J. W. Nicholson, a former colleague at Cambridge: that the momentum (mass times velocity, M × v) of a ring of electrons, times the radius of the ring, would be quantized in integral units (labeled n) times Planck's constant divided by 2π. In physics shorthand, we write this as Mvr = (nh)/(2π). He showed that if this formula were to hold true and only one electron per orbit was considered, the mathematics of classical Newtonian physics would allow orbits of only certain sizes proportional to n2. The first five of these possible orbits are shown for the one-electron hydrogen atom in Figure 2.7(a). The same mathematics showed that the electron, if it were to be found in one of those orbits, would have a corresponding distinct, precise energy, as shown for some of the orbits in Figure 2.7(b). (This is quite unlike the planets, each of which would seem to take on any size of orbit and any of an associated continuum of energies. Each planet just happens to be in one particular orbit. With just a little more or less energy, each could easily be in another nearby orbit.)

Fig. 2.7. (a) Relative sizes of the five lowest-energy Bohr orbits for the electron around the proton (center dot) in the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom. (The electron and proton would be too small to be seen, even at this approximately 100-million-times magnification.) (b) Note that the n = 1 is the lowest energy level and corresponds with the smallest orbit [label not provided in (a)]. (Energy levels will be defined in Chapter 11.)

Bohr's n = 1 state, with the smallest orbit and lowest energy, would be called the ground state. Since no smaller stable state existed, and (by postulate) the electron could only be in these stationary stable states, by postulate the atom could not collapse as classical theory would expect. In this way, Bohr would explain the observed sizes of atoms.

The Bohr model gained credibility when it exactly predicted the results of experimental data that had defied explanation for nearly sixty years. To understand the significance of this, we need to learn a little bit about spectra.

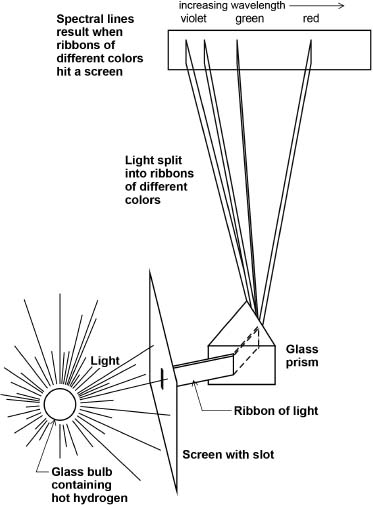

Fig. 2.8. How a spectrograph works. Light emitted from hot hydrogen is bent at different angles through a glass prism, depending upon the light's wavelength. A ribbon of light passing through a slot in a screen is shown split into four ribbons, each with a color (wavelength) characteristic of a light quantum (photon) of that wavelength emitted during an electron's change of orbit (energy).

Isaac Newton, experimenting as early as 1666, caused white light to split into a rainbow of colors (which he called a spectrum) as he passed the light through a prism of glass (glass shaped to a triangular cross section). In the early 1800s it was learned that various substances, either sparked or exposed to flames, would emit light in a mixture of different colors, and that the individual colors from these substances could be separated using prisms in spectrometers. In the spectrograph sketched in Figure 2.8, separated ribbons of light emitted from hot hydrogen show as bright-colored lines on an otherwise-dark background. Each element or compound displays its own characteristic set of colored lines.

Systematic study of spectra to identify elements and compounds began in the 1860s with the collaboration of the chemist Robert Bunsen at Heidelberg and physicist Gustav Kirchhoff (remember—Planck's predecessor at the University of Berlin). To provide a clean flame hot enough to excite the spectral emissions, Bunsen and university mechanic Peter Desaga developed what came to be known as the Bunsen burner (which, as Sam Kean would phrase it, “made him a hero to everyone who ever melted a ruler or started a pencil on fire” in chemistry lab5). Studying under Bunsen as a graduate student at about that time was Dmitri Mendeleev, a young Russian whose subsequent work would figure prominently in the characterization of the elements and the development of the periodic table of the elements. (I'll say more about Mendeleev and the development of the periodic table in Appendix B.)

HYDROGEN LINES (SOME LONGSTANDING CLUES)

It was the lines of the emission spectrum of hydrogen shown in Figure 2.8 that clinched Bohr's model. The hydrogen lines had been measured as early as the mid-1850s by the Swedish physicist Anders Ångström. At first glance, the hydrogen spectrum (turned vertical) might seem to resemble the lines showing the energy levels of the Bohr atom in Figure 2.7(b), but there is much more to it than that.

Fig. 2.9. (a) Transition of an electron from an n = 5 or n = 3 Bohr orbit to an n = 2 Bohr orbit, with the release of a violet or red wavelength photon. (b) Brackets showing the energy-level changes, that is, the energies released as photons during these transitions. (c) Violet and red spectral lines associated with these transitions, their photons, and the photons emitted.

An empirical formula describing the spectral lines in terms of integers had been devised in 1884 by a Swiss mathematics teacher, Jacob Balmer. Nothing in classical physics would explain the spectral lines or Balmer's formula. But when Bohr examined the formula, he immediately saw that his model would predict the formula and all of the observed spectral lines. Each line would be produced by the release of a light quantum in the transition of an electron from one of the higher of Bohr's energy states into a state of lower energy. The energy lost by the electron in each transition would be carried away as a single light quantum, as shown by arrows for the n = 5 to n = 2 and n = 3 to n = 2 transitions in Figure 2.9(a), with the energy lost in each case shown by the span of the brackets between energy states in (b). The spectral lines produced are shown in (c).

Bohr, like most scientists at the time, did not believe in the Planck-Einstein quantization of light, but he used Planck's formula Equantum = hf to calculate the frequency of the light wave that would be emitted for each transition. He would then be able to calculate the corresponding wavelength using the formula for electromagnetic waves that we derived earlier: c = wf (which dividing by f would give c/f = w). He found an exact match between his calculated wavelengths and the observed wavelengths for all of the lines that were seen.

Bohr had explained the line spectrum of hydrogen as light carrying away energy to allow the transition of an electron from a state of higher energy to a state of lower energy. This could only result if he had a valid model for the atom and the energy levels of the states! (That he predicted some transitions that weren't seen would be a detail to resolve later.)

On March 6, 1913, Bohr sent Rutherford the first of three papers “On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules” (as was the custom for review and forwarding by a more-senior scientist to get more-rapid publication). It was published in April. The second and third papers on the possible arrangements of electrons in the atoms of various elements were published in September and November.

Bohr's quasi-quantum, quasi-classical atom got a mixed reception when it was discussed at a meeting in England in September. On the Continent it was met with disbelief. But Bohr extended the theory to analyze spectral lines in light from the sun that didn't fit the hydrogen pattern, showing that these lines would roughly fit a Bohr model for helium (and this convinced the [by then] much-respected Einstein that Bohr's model had merit).

THE GREAT WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH—LIGHT QUANTA AND GENERAL RELATIVITY

World War I, which began on August 14, 1914, drained the laboratories of Europe in unreasonable nationalism that found friends and scientists supporting and fighting on opposite sides.

Planck, now rector of the University of Berlin, sent his students off in support of “a just war,” and signed a manifesto with ninety-three other luminaries asserting in defiance of the facts that Germany hadn't violated Belgian neutrality, had been forced into war, and had committed no atrocities. (He quickly regretted it and began apologizing to friends in other countries.) As a Swiss citizen, Einstein was not asked to sign the manifesto, but he was deeply concerned about it, and he helped to produce a counter manifesto against war and castigating German intellectuals for their blind nationalism. He was one of only four signers.

Einstein had returned to Germany earlier that year, despite his aversions and in response to a most appealing triple prestigious offer delivered by Planck and Nernst: he would be appointed to one of the two salaried positions in the Prussian Academy of Sciences, to a unique professorship at the University of Berlin without any teaching duties, and to directorship of the soon-to-be-established Institute of Theoretical Physics. However, Mileva disliked the prospect of return to Germany. She had suspicions related to Alberts's increasing friendship with a divorced cousin Elsa in Berlin. And his mother was there. Mileva and Albert argued. Eventually they agreed on a separation, and Mileva returned with the two boys to Zurich.

Motivated by the demonstration in April 1914 (by James Franck and Gustav Hertz) of Bohr-like atomic transitions in mercury vapor under the bombardment of electrons, Einstein set about describing theoretically the mechanisms by which these transitions might take place. He found once again that the energy of light itself should indeed be quantized, and further that the quanta would have momentum and an associated direction of travel. (No mass, but momentum? Interesting!) All of this would seem to confirm light as a quantized particle. But acceptance of this idea would still not come until nine years later, when another experiment brought results that could only be explained if quanta were particles with momentum. (I'll describe that experiment early in Chapter 3.)

It was also during these years of World War I that Einstein completed his much-celebrated masterpiece, the theory of general relativity. The theory required the warping of space and time under the gravitational influence of massive bodies. It explained a precession of the planet Mercury's elliptical orbit around the sun and predicted a bending of starlight as it passed near the sun, which was observed during the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919.

With his theory of general relativity confirmed, Einstein's picture was on the front pages of newspapers, relativity was discussed in the streets, and Germany heralded a triumph of German science. He had in February finally been granted a divorce from Mileva, after promising her increased payments, his widow's pension, and the money he would receive from an impending Nobel Prize. But Germany was broken by war, with its people already hungry and soon to be laden with unreasonable financial burdens in reparations. By 1923, inflation would reduce the value of the German currency to an unbelievable exchange rate of four trillion marks to the dollar. Eighty billion marks would buy a loaf of bread. Even by 1919, in the postwar environment, anti-Semitism had begun to rise to the surface. Einstein, who had become a public and antiwar figure, was threatened even during his lectures, and, despite assurances from the government, feared for his safety. He had begun to shun public exposure. Two German Nobel laureate physicists (Philipp Lenard, who had measured the photoelectric effect, and Johannes Stark, who found that an electric field would split the spectral lines of hydrogen into closely spaced lines) had by now become rabid anti-Semites and promoted a group of scientists that in 1920 specifically and publicly denounced Einstein and attacked relativity as “Jewish physics.” Nernst and others wrote articles to the newspapers in Einstein's defense.

EXTENSION OF THE BOHR MODEL (FIXING SOME OF WHAT'S WRONG)

When Bohr returned to Copenhagen in 1916, he found papers from Arnold Sommerfeld awaiting him; Sommerfeld was a distinguished professor of theoretical physics at Munich University. More precise measurements had been made that showed a “fine structure” splitting of each line of the hydrogen spectrum into a closely spaced set of lines. And then other splittings were observed when hydrogen atoms were placed in magnetic or electric fields.

Bohr's model couldn't explain these additional lines and seemed to be in trouble. But the more mathematically adept Sommerfeld had solved most of these problems by allowing elliptical as well as circular orbits lying in planes with different orientations and by recognizing that electrons moved fast enough to be significantly affected in their energies by Einstein's special relativity. He used two more quantum numbers, ℓ and m (in addition to n) to describe the split states of closely spaced energies. We'll get a look at these numbers and their physical significance later on.

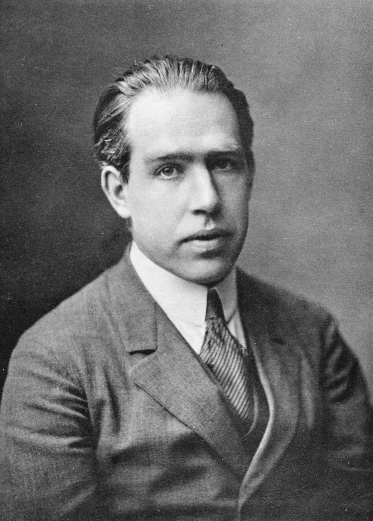

Fig. 2.10. Niels Bohr in 1922. (Photograph by A. B. Lagrelius and Westphal, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, W. F. Meggers Gallery of Nobel Laureates.)

While in England Bohr had been appointed to the new post of professor of theoretical physics in Copenhagen, and with the success of the Bohr-Sommerfeld theory his stature in the field had grown. In 1917, with the help of funding from friends for the land and the buildings, he was able to get approval for his Institute for Theoretical Physics, known as the Bohr Institute, with construction to be completed in 1921. There he hoped to replicate the climate for learning and exploration that he had enjoyed under Rutherford in Manchester. (Fig. 2.10 shows Bohr at about that time.)

Because of the war, German scientists were excluded from international meetings. But Bohr had no particular bias. He invited Sommerfeld to visit Copenhagen, and following that visit was invited to visit Berlin in April 1920. There he met Einstein and Planck for the first time. He stayed at the latter's home. The days were filled with the discussion of physics. Bohr and Einstein would walk the streets of Berlin together or dine at Einstein's home. Einstein subsequently stopped by to visit with Bohr on the way back from a trip to Norway in August.

EXPLAINING THE PERIODIC TABLE (NOT QUITE)

With further work, Bohr would use the Bohr-Sommerfeld theory to begin to qualitatively explain the periodic table and the properties of the elements, in particular how apparently inert, nonreacting elements periodically occur just after and just before highly reactive elements as one considered successively heavier and heavier atoms. The inability to explain the properties of the elements, their arrangement according to these properties in a periodic table, and these particular aspects of the table had long been a failing of classical physics. (As background mainly for Chapters 13 and 14, I provide in Appendix B a brief description of the table, the history of its construction, and a quick look at the charismatic character most responsible for its development.) Bohr was invited to Göttingen to deliver in June 1922 a celebrated set of seven lectures on the subject. Einstein would not attend, out of fear for his safety, but when he heard of Bohr's ideas, he would comment that they appeared “as a miracle” of explanation.

In October 1922, Niels Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and of the radiation emanating from them.” Based on the Bohr-Sommerfeld theory, he had been able to predict the existence of the yet-undiscovered element hafnium, atomic number 72 (that is, having 72 electrons and an equal number of protons), and he made that prediction, which turned out to be correct, during his Nobel Prize lecture in December.

Still, there remained two major problems with the model. These were eventually solved by a young Wolfgang Pauli, through the inclusion of two additional assumptions beyond those already made by Bohr and Sommerfeld.

Fig. 2.11. Wolfgang Pauli. (Image from AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.)

The Viennese Pauli, fourth from the right in the back row of Figure 1.1, had a brilliance compared sometimes to that of Einstein. (Fig. 2.11 shows an older, more middle-aged Pauli.)

Pauli was born on April 25, 1900. His father had been a physician but shifted to science, at the same time changing his name from Pascheles to Pauli and converting to Catholicism to avoid a rising tide of anti-Semitism. Pauli grew up knowing nothing of his Jewish ancestry. His mother, a pacifist and socialist, was a well-known journalist and writer; and he and his sister, who was six years younger, were exposed to the frequent visits of leading persons in the arts, medicine, and the sciences.

Pauli became interested in physics at an early age, under the influence of his godfather, the renowned Austrian physicist Ernst Mach. Out of boredom with school, he was provided tutors; and out of boredom with his tutoring, he read Einstein's papers on relativity. In January 1919, then just eighteen years old, he published a paper on relativity that brought him recognition in the field. He left Vienna that year (for lack of qualified teachers) to begin work toward a doctorate under the much-respected Arnold Sommerfeld in Munich. He was more inclined toward the nightlife in Munich than formal study, though. Sommerfeld had set him the task of applying the new quantum physics to the ionized hydrogen molecule. That Pauli could not explain experimental findings on the ion was taken as evidence of deficiencies in the Bohr-Sommerfeld model. With doctorate in hand, Pauli in 1921 moved on to study as an assistant to Professor Max Born in Göttingen.

Born is the person second from the right (next to Bohr) in the second row of Figure 1.1. He had sought out Pauli, intent on creating an institute of theoretical physics in Göttingen to rival that of Sommerfeld in Munich. Earlier, Born had formed a strong friendship as a young professor with Einstein in Berlin. Born and Einstein shared a passion for music as well as physics, and even when Born was called into the service (stationed near Berlin), he would often be invited for evenings and music at Einstein's home. Born's approach to physics led from his proficiency with mathematics; Pauli's, more from an intuitive sense of the physics itself.

SPIN (MAKING IT WORK #1)

By 1922, the electrons in the Bohr-Sommerfeld atom were considered to occupy groups of states, with the states within each group only slightly different in energy. Each group, called a “shell,” had energies near one of the original Bohr orbital energies. Bohr had begun to picture each successive element as resulting from the addition of one more proton to the atomic nucleus of its predecessor and one more electron into the surrounding shells. The chemical properties of the elements would result from the closeness of each element to either just filling a shell with electrons or going beyond that to add electrons toward the next shell. In particular, elements that tended not to react and combine chemically—helium, neon, argon, and the like—the noble gases, would be marked by the just filling of an electron shell.

The first problem with this was that the electrons seemed to produce the noble gas elements only when twice as many electrons were present than was needed to fill the states in the shells. The theory was off by a factor of two. Pauli postulated in the spring of 1925 (without any reason or proof except that it made Bohr's theory work) that for every one of the Bohr-Sommerfeld states there must be another property, which could take on either of two values marked by a fourth quantum number. Each Bohr-Sommerfeld orbit could take on either of these two values, and so altogether there would be twice as many total spin and orbit states for the electron, just what was needed to explain the noble gas elements.

Two Dutch doctoral students at the university in Leiden, George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Gaudsmit, suggested that this fourth property would have to be intrinsic within the electron, not part of the electron's orbit. They called it spin, though there was nothing to indicate that the electron would in fact be spinning. This property would be quantum in nature with no analogue in classical physics. The two students published their results in the summer of 1925. So now there were four quantum “numbers” for each state, three labeled generally by the letters n, ℓ, and m, and the fourth labeled conveniently here simply as “spin.”

Uhlenbeck and Gaudsmit were considered for the Nobel Prize, but the idea of spin had been independently proposed earlier by Ralph Kronig, a graduate student from Columbia University who was working on a postdoctoral tour in Europe. Amid the controversy, the committee decided to award no prize at all for this contribution.

EXCLUSION (MAKING IT WORK #2)

A second major problem with the argument of the filling of shells was that all electrons might be expected to occupy just one state, the state of lowest energy, as is the tendency in nature. Because all electrons would be in the same state, shells would not be filled, and the properties of all of the elements (that is, of every type of atom) would be totally unexplained. Every atom would have all of its electrons occupy just one state, the lowest-energy, ground state, and so all would be equally far from filling all of the sites in their lowest-energy shell.

To make the theory function properly, Pauli, in 1925, postulated “exclusion”—that no two electrons would be able to occupy the same overall state. That is, no two electrons would have the same set of quantum numbers n, ℓ, m and spin. (Again, Pauli did this without proof or physical reason, except that it fit the arrangement of the elements in the periodic table.) The electrons in an atom would populate the available states, one electron per state, starting with the lowest-energy states. Once every state in a shell had one electron in it, the next electron would go on to start the occupation of the lowest-energy state in the next, higher-energy, shell. The last, highest-energy, occupied electron state in any atom would register the degree to which that atom's outermost shell was filled. The chemical properties of that atom, that element, would be in large measure determined by the closeness to which the electrons came to completing the full occupancy of a shell: for instance, two states away, one state away, full occupancy (a noble gas), one more than full occupancy, two more than full occupancy, and so on. How the chemical properties of the elements are related to these occupancies is described in Part Four. The key point here is that it worked. With these postulates of spin and exclusion, the Bohr theory would qualitatively explain the elements and their properties. And Pauli would receive the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1945 “for the discovery of the Exclusion Principle, also called the Pauli Principle.”

Despite its successes in describing the elements and their properties, many physicists were uneasy that the Bohr-Sommerfeld model of the atom was built largely on postulate and assumption, and that it still ignored the classical requirement of radiation and collapse for an orbiting (therefore accelerating) electron. Others, Pauli among them, were more than uneasy: they were totally frustrated with the cobbled-together nature of the theory. They cited the need for an entirely new physics.