1

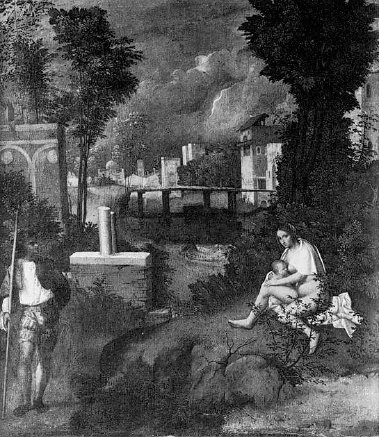

Independent Landscape

The first independent landscapes in the history of European art were painted by Albrecht Altdorfer. These pictures describe mountain ranges and cliff-faces, skies stacked with clouds, rivers, stream-beds, roads, forts with turrets, church steeples, bridges, and many trees, both deciduous and evergreen. Tiny, anonymous figures appear in some of the landscapes. But most are entirely empty of living creatures, human and animal alike. These pictures tell no stories. They are physically detached from any possible explanatory context – the pages of a book, for example, or a decorative programme. They are complete pictures, finished and framed, which nevertheless make a powerful impression of incompleteness and silence.

These landscapes are small enough to hold in one hand. They were meant for private settings. Extremely few have survived: two were painted not directly on wood panel like ordinary narrative or devotional paintings, but on sheets of parchment glued to panel; three others were painted on paper. Altdorfer also made landscape drawings with pen and ink, and he published a series of nine landscape etchings. Altdorfer signed most of his landscapes with his initials. He dated one of the drawings 1511 and another 1524, and one of the paintings on paper 1522. In Altdorfer’s time, drawings and small paintings were seldom signed or dated. A signed landscape, given its unorthodox content and ambiguous function, is doubly remarkable.

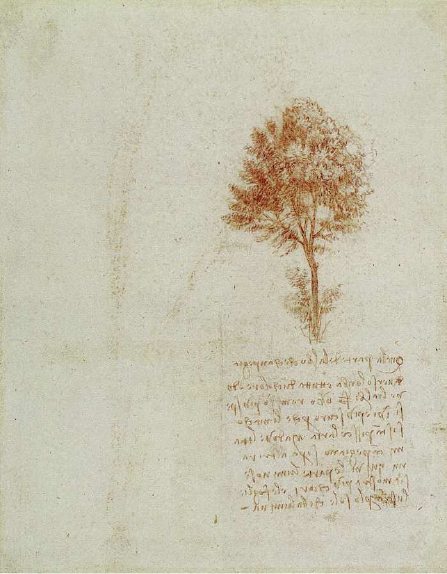

The Landscape with Woodcutter in Berlin, painted with translucent washes and opaque bodycolours on a sheet of paper 20.1 centimetres high and 13.6 wide, opens at ground level on a clearing surrounding an enormous tree (illus. 1). At the foot of this tree sits a figure, legs crossed, holding a knife, with an axe and a jug on the ground beside him. From the trunk of the tree, high above his head, hangs an oversized gabled shrine. Such a shrine might shelter an image of the Crucifixion or the Virgin; in this case we cannot say, for it is turned away from us. The low point of view and vertical format of this picture reveal little about the place. Is this a road that twists around the tree? Are we at the edge of a forest or at the edge of a settlement? The tree poses and gesticulates at the centre of the picture as if it were a human figure, splaying its branches into every corner. And yet it is truncated by the black border at the upper edge of the picture.

1 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Woodcutter, c. 1522, pen, watercolour and gouache on paper, 20.1 × 13.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

2 Hercules Segers, Mossy Tree, c. 1620-30, etching on coloured paper, 16.9 × 9.8. Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam.

To this iconographic austerity corresponds a great simplicity of means. Many effects are achieved with few tools. The picture is imprecise, shambling, genial, candidly handmade. The branches of the tree sag under shocks of calligraphic foliage, combed out by the pen into dripping filaments. This pen-line emerges from under layers of green or brown wash at the margins of the tree-trunk and the copse at the left, in licks and tight curls, legible traces of the movement of the artist’s hand. Contours do not quite coincide with masses of colour. Behind the tree-trunk, a row of trees was outlined in pen, but never coloured in. The brittle buildings tilt to the right. The picture is touched by a slightly manic spirit of exaggeration, which makes the woodcutter’s passivity and the silence of the place even more uncanny. These are rough-hewn and generous effects. A curtain of blue wash creates a breathy, sticky ether that fades into white near the profile of the mountains. The mountains – blue, like the sky – are overlaid with a ragged net of white streaks. Masses of leafage, by contrast, are made tangible by a speckling of bright green, so unreal that it conspicuously sits on the surface of the picture rather than in it. Paint adheres to paper like a sugary residue. All the picture’s technical devices are disclosed, yet they look unrepeatable.

Such a picture as Altdorfer’s Landscape with Woodcutter – as rich as a painting, as frank and gratuitous as a drawing – is not easily located either within an art-historical genealogy or within a cultural context. No Netherlandish or Italian artist of the early sixteenth century produced anything quite like it. Some German contemporaries and followers of Altdorfer did make independent landscapes. Wolf Huber of Passau, it appears, even established a kind of trade in landscape drawings. Altdorfer published some of his own ideas about landscape in his brittle, spidery etchings, and indeed through these etchings he exerted an impact that can be traced for several generations. But by and large this is not a success story. The independent landscape staked only the feeblest of claims to the surfaces of wood panels, which in southern Germany around 1500 were still largely the territory of Christian iconography. Nothing like Altdorfer’s mute landscape paintings, with their elliptical idioms of foliage and atmosphere, would be seen again until the close of the sixteenth century, in the forest interiors of Flemish painters working in the wake of Pieter Bruegel: Jan Bruegel the elder, Jacques Savery, Lucas van Valckenborch, Gillis van Coninxloo.1

Not until the tree studies of Roelandt Savery, Hendrick Goltzius, and Jacques de Gheyn II did anyone again twist a trunk or attenuate a branch with such single-minded fantasy.2 But the most apt comparisons of all are the moody etchings of Hercules Segers, an eccentric and still dimly perceived giant of early seventeenth-century Dutch landscape, pupil of Coninxloo and powerful inspiration to Rembrandt, working a full hundred years later than Altdorfer. Only a single impression survives of Segers’s Mossy Tree, an etching on coloured paper of a nameless, spineless specimen that might have been plucked from a fantastic landscape, perhaps from one of Altdorfer’s etchings (illus. 2).3 Indeed, the affinity between Segers’s prints and those of Altdorfer’s earliest followers was remarked on as early as 1829 by J.G.A. Frenzel, the director of the print cabinet in Dresden.4

Altdorfer’s independent landscapes, as strange and unprecedented as they were, left no discernible traces in contemporary written culture. They are mentioned in no letter, contract, testament or treatise. The earliest documentary reference to a landscape by Altdorfer dates from 1783; that picture has since disappeared. One of the surviving landscapes can be traced back to a late seventeenth-century collector, but no further. Thus we do not even know who originally owned or looked at these pictures.

What does an empty landscape mean? Christian and profane subjects in late medieval painting were often staged in outdoor settings. Many pictures juxtaposed and compared earthly and heavenly realms, or civilization and wilderness. Many stories about saints revolved around spiritual relationships to animals or to wilderness. German artists, and Altdorfer in particular, addressed these themes also through rejuvenated pagan subjects, such as the satyr, or through autochthonous mythical characters, such as the forest-dwelling Wild Man. Literary humanists – many of whom kept company with artists – debated the historical origins of Germanic culture and its peculiar entanglement with the primeval forest. But none of these themes is simply illustrated by Altdorfer’s landscapes. These pictures lack any argumentative or discursive structure. They make no move to articulate a theme. Instead, they look like the settings for missing stories.

Deprived of ordinary iconographic footholds, one might well wonder whether the early independent landscape is not simply an image of nature. But German pictures in this period, particularly small and portable pictures on paper or panel, had limited tasks: they told stories; they articulated doctrine; they focused and encouraged private devotion. To ask the landscape of the sixteenth century to be a picture ‘about’ nature in general is to impose a weighty burden on it. We would probably not think to do it had not some Romantics elevated the landscape into a paradigm of the modern work of art. Schiller, for example, expected the landscape painting or poem to convert inanimate nature into a symbol of human nature.5 The difficulty of the early landscape is that it looks so much like a work of art.

Both Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, Altdorfer’s older contemporaries, had something to say about nature. Nature for Dürer meant the physical world. This nature ought to curb the artist’s impulse to invent and embellish, to pursue private tastes and inclinations. ‘I consider nature as master and human fancy [Wahn] as a fallacy’, wrote Dürer.6 His erudite friend Willibald Pirckheimer, in a humanist ‘catechism’ of 1517, an unpublished and only recently discovered manuscript, numbered the ‘striving for true wisdom’ among the highest virtues: ‘Observe and study nature’, he advised; ‘inquire into the hidden and powerful workings of the earth’.7 Cognition of nature, in Pirckheimer’s catechism, became an ethical duty. In his book on human proportions, published posthumously in 1528, Dürer warned that ‘life in nature reveals the truth of these things’. Nature provided examples of beauty and correct proportions, and therefore the controlling principles of art: ‘Therefore observe it diligently, go by it, and do not depart from nature according to your discretion [dein Gutdünken], imagining that you will find better on your own, for you will be led astray. For truly art is embedded in nature, and he who can extract it, has it.’8 For Dürer, the study of nature was a discipline, and nature itself the foundation of an aesthetic of mimesis. ‘The more exactly one equals nature [der Natur gleichmacht],’ he stated in two different treatises, ‘the better the picture looks’.9 But Dürer never suggested that nature should become the basis for an independent landscape painting, and indeed he did not make any such objects. In his drawings he left first-hand accounts of his investigations into the morphologies of animals, plants and minerals. But these were private experiments and memoranda, not public works. His watercolour and silverpoint landscape views registered the impressions of a traveller. Dürer’s eye was too hungry, and often he did not spend enough time on the paper to finish the drawing. Instead, a change of sky or a suddenly perceived riddle of foliage would distract him from the discipline of pictorial organization, and the work would never be concluded. Water-colours like the Chestnut Tree in Milan10 or the Pond in the Woods in London (illus. 74) break off in the middle – appealingly, to our eyes. When Dürer ran out of patience, or light, he simply stopped adding layers of wash. Dürer was charmed by the random datum and the ephemeral impression. His Fir Tree in London, rootless, floats on perfectly blank paper (illus. 3).11 Pedantry would have killed the tree, robbed the boughs of their spring and splay. Instead Dürer wielded the brush with a draughtsman’s agitated hand. He animated the fir with a mass of short, wriggling strokes overlaid on a base of yellow and green washes; the strokes escape around the edges like fingertips. Such a transcription of a particular tree manifests neither the vagaries of personal inclination nor the stable certainties of intelligible nature. Dürer’s watercolour studies, even if completed, were never offered to the world as pictures.

3 Albrecht Dürer, Fir Tree, c. 1495, watercolour and gouache on paper, 29.5 × 19.6. British Museum, London.

Leonardo, whose thinking was more involuted, escaped this impasse. Science or knowledge, for Leonardo, would reveal the principles and dynamic processes of nature – an ideal or ‘divine’ nature – while painting would accurately represent the visible data – the works of nature. But those principles of dynamic or generative creativity uncovered in nature could then serve as a model for the inventive and fictive capacities of the true artist. Knowledge of nature distinguished the artist not from the unreliable fantasist, as it did for Dürer, but from the merely reliable transcriber of the physical world. The painter who adjudicates among the data and recom-bines them in his work is ‘like a second nature’.12 Leonardo apostrophized the ‘marvelous science of painting’: ‘You preserve alive the ephemeral beauties of mortals, which through you become more permanent than the works of nature.’13 These thoughts anticipate the classic defences of poetry of the later sixteenth century, where fiction is prized over history precisely because fiction need not tell the truth. The painter, wrote Leonardo, can produce any landscape he pleases, for ‘whatever exists in the universe through essence, presence, or imagination, he has it first in the mind and then in his hands’.14 Such a landscape Leonardo might have painted! But he never did; that is, he never painted a mere landscape, one with a frame around it. Leonardo had new ideas about how to paint, not what to paint. He painted the same kinds of pictures that painters before him had: narratives, figure groups, portraits with landscape behind them. Leonardo’s drawings of plants and geological phenomena are even less like complete pictures than Dürer’s. A tree study at Windsor Castle, dating from c. 1498, a tightly controlled spray of dusty red chalk, illustrates a manuscript preparatory to an eventual treatise on painting (illus. 4).15 The specimen – a birch, or a locust? – supplements a terse set of observations: ‘The part of a tree which has shadow for background, is all of one tone, and wherever the trees or branches are thickest they will be darkest, because there are no little intervals of air.’16

4 Leonardo da Vinci, Tree Study, c. 1498, red chalk on paper, 19.1 × 15.3. Royal Library, Windsor Castle.

Albrecht Altdorfer, on the other hand, left no nature studies at all. For most painters in this period, there was really no need to venture out under an open sky. Apart from a few drawings in pen and ink, Altdorfer’s landscapes are indoor affairs. He was largely indifferent to the measurable or nameable attributes of the natural object. Sometimes, in the margins of his ordinary sacred paintings, Altdorfer described identifiable flora, for example plants with medicinal or symbolic significance.17 But so many of his trees are monsters or fictive hybrids.18 Moreover, he left no writings on nature or art; indeed, none on any topic at all. Nor is there any documentary or even circumstantial evidence that reveals what or whether Altdorfer thought about nature.

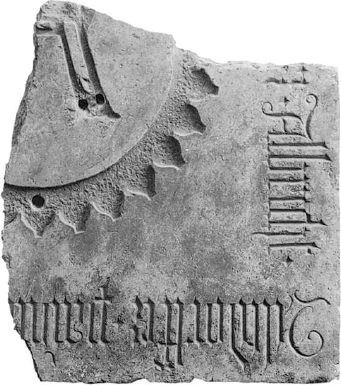

Altdorfer is known to us only through his works and through the silhouette of a public career. Like a number of other German and Italian artists of the period he managed to convert his talent into local social and political standing. He died in Regensburg on 12 February 1538, probably in his mid-fifties, at the crest of a highly visible and public career. His red marble tombstone in Regensburg’s Augustinian church, where he was provost and trustee, was recovered by accident in 1840 during excavations. The inscription described him not as a painter, but as the ‘honourable and wise Herr Albrecht Altdorfer, Baumeister’ (illus. 5).19 As the superintendent of municipal buildings he had overseen the construction of several commercial structures, perhaps even designed them; they all stand today. He also shored up the fortifications of the city. In his day Altdorfer was one of the outstanding political figures in Regensburg. He had sat in the Outer Rat or Council since 1517 and in the Inner Council since 1526, and had occupied various lesser public offices. In 1535 the city sent him as an emissary to King Ferdinand in Vienna. He owned three different homes, two of them at the same time, as well as vineyards outside the city.

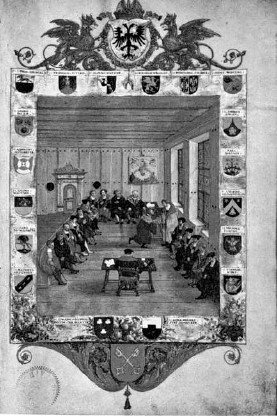

What did Altdorfer look like? A portrait of an architect, formerly in Strasbourg but since destroyed, with an airy, capricious landscape behind him, was at one time judged to be a self-portrait by Altdorfer, or a portrait of him by a colleague.20 But the only indisputable revelation of Altdorfer’s person is a painting on parchment by his pupil Hans Mielich (illus. 6). This painting is found on the second page of the Freiheitsbuch, a kind of constitution of the city, dated 1536, and depicts the assembly of the Inner Council on the occasion of the presentation of this very book to the mayor.21 Altdorfer is usually identified by his coat of arms, the fourth from the bottom on the left-hand side, as the figure in the black beret and fur-lined cloak. But in a chalk drawing by Joachim von Sandrart, the seventeenth-century academician and historian of German art, Altdorfer wears a forked beard.22 Sandrart had the drawing engraved and published together with the biography of Altdorfer in his Teutsche Academie of 1675 (illus. 7).23 Both Sandrart’s drawing and a contemporaneous engraving by Mathias van Somer evidently derive from a common source, perhaps an old painted portrait belonging to the city. Sandrart was in Regensburg in 1653 and 1654 and later painted an altar for the abbey of St Emmeram. Mathias van Somer worked in Regensburg from 1664 to 1668. Their versions of Altdorfer’s head actually match a different councillor in Mielich’s miniature – the third from the bottom on the left, the one gesturing with his hands.24 Finally, a man holding a scroll and looking out of the background of a panel of Altdorfer’s St Florian altarpiece, who had already struck some as a possible self-portrait, wears a similar forked beard.25

5 Fragment of the tomb of Albrecht Altdorfer, 1538, marble. Stadtmuseum, Regensburg.

Altdorfer was not born to such status. Like Dürer, Lucas Cranach, Hans Burgkmair and Hans Holbein, Altdorfer was the son of an artist. Altdorfer won public attention not by undertaking huge and time-consuming public painting projects, as artists of his father’s generation might have done. Nor did he attach himself to a princely court, as Cranach did, although, like Dürer, he did do occasional work for the Emperor and other potentates. He eventually made a giant painted altarpiece and many large devotional panels. But at the start Altdorfer made his name with intimate, modestly scaled works in unconventional media and with eccentric subject-matter. He painted small, clever, devotional panels; he made finished drawings of profane and historical subjects; he published his ideas in engravings, woodcuts and etchings. No contemporary reactions to Altdorfer’s work are recorded. Yet we can infer that he appealed to a narrow and sophisticated audience with his esoteric subject-matter, his oblique treatment of traditional subjects, his visual wit, and his technical ingenuity and self-confidence. Most important, following Dürer’s lead, he signed and dated his works. Altdorfer put vivid testimonials to his own talents, linked by a distinctive style and signature to his person, directly into the hands of individual amateurs and collectors. His monogram, which mimics Dürer’s, was actually carved on the centre of his tombstone, no longer the mere corroboration of style, but an emblem in its own right.

|

6 Hans Mielich, Presentation of the ‘Freiheitsbuch’ before the Assembly of the Inner Council, 1536, miniature, from the Freiheitsbuch, 41 × 27.5. Stadtmuseum, Regensburg. |

By the end of his career Altdorfer was dividing his time between politics, architecture and a few prestigious painting projects. The small and intimate works, including the landscapes, played an ambiguous role in his career, just as they did in Dürer’s. They were the foundation of his reputation, and they effectively preserved it, especially the small engravings with pagan or erotic subjects. Yet Altdorfer himself surely imagined they would, in the end, be overshadowed by his buildings and by his larger paintings. One of these late, public pictures is Altdorfer’s grandest and most celebrated work, and indeed one of the most remarkable of all Renaissance paintings, the Battle of Alexander made for Wilhelm IV, the Wittelsbach Duke of Bavaria, in 1529 (illus. 8).26 Over the next decade Wilhelm assembled a cycle of eight paintings of Antique heroes, all in vertical format; they hung in the Residenz in Munich together with a cycle of heroines in horizontal format. Wilhelm drafted all the outstanding Bavarian and Swabian painters of the day; Altdorfer and Hans Burgkmair were the first. The commission was so important to Altdorfer that he declined a term as mayor of Regensburg in order to complete it. The picture represents the victory of Alexander the Great over the Persian monarch Darius at Issus in Asia Minor in the year 334 BC, as recounted by the first-century historian Curtius Rufus. The texts inscribed on the floating tablet and in various banners lofted by the armies were very likely composed by Aventinus, the Bavarian court historian, who was resident in Regensburg from 1528. The lower half of the picture describes Alexander’s pursuit of Darius’s chariot, slicing a path through a bristling, twitching carpet of soldiers. Darius throws a panicked glance backward, exactly as he does in the famous floor mosaic from the Casa del Fauno at Pompeii, which was not to see the light of day for another three hundred years (illus. 10). The upper half of the Battle of Alexander expands with unreal rapidity into an arcing panorama comprehending vast coiling tracts of globe and sky (illus. 9). It is as if the momentous collision of armies exploded outward into three dimensions, and was only then projected back onto a planar surface. For the picture represents an historical pivot, the expulsion of a force from the East, a muscular resistance to the left-to-right flow of history. The sun outshone the moon, just as the Imperial and allied army successfully repelled the Turks – massed under the sign of the Crescent – from the walls of Vienna in October 1529, the very year this picture was painted.

8 Albrecht Altdorfer, The Battle of Alexander and Darius at Issus in 334 BC, 1529, oil on panel, 158 × 120. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

9 Details from The Battle of Alexander.

10 Details from The Battle of Alexander.

The Battle of Alexander is the foundation of Altdorfer’s modern fame. As late as 1740 a German writer attributed the painting to Dürer.27 But in 1800 Napoleon’s Rhine Army carried it from Munich to Paris, and the work and its real author entered art history. In 1814 the victorious Prussian troops who commandeered Napoleon’s residence at Saint-Cloud as their headquarters supposedly found it hanging in the Emperor’s bathroom.28 Napoleon must have discovered in Altdorfer the same sincere vigour that he savoured in his favourite poet, another ‘northern Homer’, the supposed primitive, Ossian. In the summer of 1804, the Romantic essayist and critic Friedrich Schlegel, one of thousands of post-war German pilgrims to the Louvre, saw the Battle of Alexander and marvelled. ‘Should I call it a landscape, or a historical painting, or a battle piece?’, Schlegel wondered. ‘Indeed this is a world, a small world of a few feet; immeasurable, uncontrollable are the armies which flow against each other from all directions, and the view in the background leads to the infinite. It is the cosmic ocean . . .’. He ended by pronouncing the picture a ‘small painted Iliad’.29

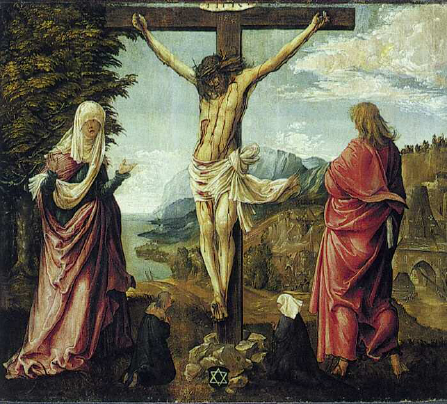

Schlegel’s question introduces one of the recurrent themes of landscape painting in the West: the pretension to epic. Landscape painting magnifies outdoor setting at the expense of subject-matter. But as outdoor space expands, it offers itself again as the setting for still grander subjects. The far-flung spaces of the Roman ideal landscapes of the seventeenth century, whose leading painters were Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, pulse with the aura of their mythological and historical subjects, no matter how minuscule those subjects appear. The rhythmic landscapes of Rubens portend vast narratives even when those narratives are physically absent. The give and take between the intimate and the epic landscape is encapsulated already in Altdorfer’s career. Altdorfer’s forest landscapes, such as the Berlin watercolour of the single tree, generate mood by relaxing temporal structures. They distil mood from narrative. Altdorfer’s empty landscapes carried to a logical conclusion the pattern of extreme negligence towards narrative already manifested in a picture such as the St George and the Dragon in Munich, dated 1510, where man and monster are dwarfed by feathery bolsters of foliage (illus. 96). But even within Altdorfer’s work, the peculiar achievements of these pictures – their greenness, their textures – were constantly being absorbed back into epic, where they entered into restive tension with story and character. Landscape pressed itself into the foreground, literally or thematically, in all the largest and most imposing panels of his middle years: the lurid, nocturnal outdoor scenes from the Passion cycle of the St Florian altarpiece (illus. 50); the Crucifixion in Kassel, with figures like implacable totems before an immense, bulging panorama (illus. 11); the Two St Johns in Regensburg, rooted in the earth like fleshy fungi (illus. 12); the billowing, overgrown Christ Taking Leave of His Mother in London (illus. 13). The trifling, intimate, hand-held landscape can hardly stand comparison to such great-souled paintings as these. And yet, once planted within an epic, landscape could surreptitiously eat away at it from the inside, until the day when Schlegel could momentarily wonder whether the Battle of Alexander was actually a ‘landscape’.

The purpose of this book is, in effect, to agree with Schlegel that it is not. In his true landscapes Altdorfer isolated certain pictorial qualities associated with the settings of narrative and made them the stuff of their own pictures. He prised landscape out of a merely supplementary relationship to subject-matter. This moment of isolation tends to get obscured when it is assumed that it was nature that furnished the principle of isolation. For a picture that retains nature while rejecting its antithesis, culture, can choose either to include or to exclude the human figure. The human figure need not disrupt nature; it can participate in and imitate natural processes, or it can share the painter’s and the beholder’s openness to nature. As a result, landscape in the West has been conspicuously tolerant of insect-like staffage or ‘filler’ figures, of embedded ‘beholder’ figures, and even of stories. In some cases the artefacts of culture themselves are assimilated to nature and thus granted safe passage within the landscape picture. Ruins or cemeteries in Ruisdael, for instance, or a watermill in Constable, are treated as if they were nature. In this tradition, therefore, it has not been strictly necessary to exclude subject-matter in order to win a reputation as a landscape painter.

Altdorfer’s principle of exclusion was not the divide between nature and culture, but rather the divide between setting and subject. The emptiness of his landscapes is the hole once filled by the acting human figure. The clue is their verticality: these pictures derive structurally from small pictures with narrative and hagiographical subject-matter.

To recover a sense of the radicality and open-endedness of Altdorfer’s invention, one needs to abandon any presumption of a pre-existent idea about nature, of a Naturgefühl or ‘feeling for nature’, or, indeed, of any primary experience of nature that his landscapes were meant to preserve. The idea of nature is so protean and problematic that a hypothesis about the origins of landscape that can afford to set it aside automatically becomes, by any standard of theoretical parsimony, highly attractive. But this is not so easy to do. Any interpretation of Altdorfer is burdened by the dense and prestigious later career of landscape painting. For many historians who were witnessing the closing phases of this career, landscape painting had come to compensate for the great dissociation of mind and nature which modernity seemed to suffer under. Landscape in the West was itself a symptom of modern loss, a cultural form that emerged only after humanity’s primal relationship to nature had been disrupted by urbanism, commerce and technology. For when mankind still ‘belonged’ to nature in a simple way, nobody needed to paint a landscape. When poets, wrote Schiller, can no longer be the custodians of nature, ‘and already in themselves experience the destructive influence of arbitrary and artificial forms, or have had to struggle against that influence, then they emerge as the witnesses and the avengers of nature. Either they are nature, or they will seek lost nature’. Landscape painting restored, momentarily, an original participation with nature, or even – in its greatest Romantic apotheoses – re-established contact with the lost sources of the spiritual. For Schiller, treading the fragile bridge between aesthetics and morality constructed by Kant in the Critique of Judgement, it was actually better to search for nature than to possess it. ‘Nature makes [the poet] one with himself; art divides and splits him in two; through the Ideal he returns to oneness . . . The goal which man strives after through culture is infinitely preferable to that which he arrives at through nature.’30 This potent model of cultural loss and redemption through art governed the Romantics’ perception of their own situation. Moreover, it went on to pervade interpretations of the Renaissance. For a number of modern art historians, who came to see the Renaissance as a kind of prefiguration of the Romantic crisis, Altdorfer straddled a threshold of intellectual history. His works preserved a twilit image of a pre-modern animated cosmos, an organic totality infused with a divine spirit or linked by correspondence with a divine macrocosm.31 There was indeed plenty of interest in such a cosmology in Altdorfer’s time. Versions of pantheism, with ties to pagan cults, neo-Platonism and the occult, simmered in the writings of natural philosophers like Paracelsus, literary humanists like Conrad Celtis, and even radical Protestants. Altdorfer’s landscapes have thus been understood as the belated epiphanies of a lost unified consciousness, talismans charged with authentic prelapsarian energy, perhaps demonic, perhaps simply pious and popular, or völkisch.

11 Albrecht Altdorfer, Crucifixion with Virgin and St John, c. 1515, oil on panel, 102 × 116.5. Gemäldegalerie, Kassel.

12 Albrecht Altdorfer, The Two St Johns, c. 1515, oil on panel, 173.2 × 233.6. Stadtmuseum, Regensburg.

Sociological interpretations of the origins of landscape have been aimed directly against this sort of neo-Romanticism. Such interpretations dismiss the reunification with nature proposed by landscape painting as an aesthetic fiction. Art, in other words, should not deceive us into thinking we are actually making contact with nature; in pictures the culture merely constructs a nature. But materialist art history is often tinged with its own nostalgia, not for the pre-modern and pre-technological art of nature, but for a pre-bourgeois life of nature. Matthias Eberle, for example, following Schiller, Marx and Adorno, sees the Renaissance landscape as the expression of an urban or bourgeois consciousness of a new distance and detachment from the land. ‘As long as nature stands in direct connection with human life’, he explains, ‘the connection between nature and human history does not need to be questioned’.32 Landscape is the result of the subject’s conversion of nature into an object. Eberle’s own piety for nature remains intact. He accepts the reality of the original pre-modern oneness with nature, and thus laments the alienation that drove the painter to paint a landscape.

13 Albrecht Altdorfer, Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, 1520(?), oil on panel, 141 × 111. National Gallery, London.

To dispel these various nostalgias for nature, one must preserve the critical insight that pictures themselves actually generate ideas about nature, and at the same time refrain from dismissing that ‘secondary’ image of nature as the phantasm of the aesthetic ideology. There is no use searching for nature either among the relics of a pristine and more authentic art, or in sensual and empirical life. Once the process of figuration is uncoupled from a prior natural object, one in fact loses confidence that nature will ever manifest itself anywhere but in that figure. Otto Benesch raised this possibility, an important complication of his own neo-Romantic argument about Altdorfer’s cosmology, with the phrase malerische Welteroberung (‘conquest of the world through painting’), which suggests the active part that picture-making took in the genesis of ideas about the cosmos. The phrase All-Belebung des Bildorganismus (‘total enlivening of the picture-organism’) in turn implies that the concept of the organic unity of the physical world was encouraged by the analogy with the pictorial composition, with the formal coherence of the depicted landscape.33 Equally, one could argue that the vigour and elusiveness of the artist’s calligraphic style sharpened perceptions of the dynamic and the kinetic in the physical world. When Benesch, and following him Franz Winzinger, wrote that the early landscape transformed the beholder’s religious piety into piety for nature, they implied that the rhetoric of the picture itself was capable of supplanting Christian iconography and installing a new subject.34

This hyperbole should not obscure the essential insight into the apriority of figuration that lies behind it. Ernst Gombrich, both in Art and Illusion and in his influential essay on Renaissance landscape, evoked with uncommon pungency the power of pictorial formulations to shape perceptions of real landscape.35 The Venetian Lodovico Dolce attested to the overwhelming power of the image to displace the perception of the original, when he described a patch of landscape in a picture by Titian – adapting a commonplace of ancient writing on art – as so good that ‘reality itself is not so real’.36 More than a century later the French critic Roger de Piles observed that the bad habits of painters ‘even affect their organs, so that their eyes see the objects of nature coloured as they are used to painting them’.37 Verbal representations of landscape in the Renaissance, too, can hardly be trusted as simple registers of optical experience. Many apparently straightforward landscape descriptions were shaped by earlier literary treatments or by classical literary topoi. This has been amply demonstrated, for example, for the landscape descriptions of Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II), which figured so memorably in Jakob Burckhardt’s account of the Renaissance ‘Discovery of the World’.38 Even Columbus’s simple descriptions of the landscape of the New World, which Tzvetan Todorov read as testimony to an ‘intransitive’ admiration of beauty,39 were moulded and constrained by an ideal of idyllic or paradisaical beauty.

The present study is aimed directly at this gap between the physical world and its image, between place and picture. In this respect it differs from some other accounts of the rise of landscape in the Renaissance, such as Otto Pächt’s derivation of the Franco-Flemish calendar illustration out of the northern Italian nature study.40 Altdorfer did not ground his landscapes in any fresh scrutiny of natural data. Instead, he worked from the frame inward. His landscapes began with strong gestures of style – flamboyant strokes of the pen, ostentatious inflammations of colour, extravagances of scale. This interpretation of the pictures will in turn begin with an historical account and localization of these gestures.

Svetlana Alpers in her extraordinary study of the visual culture of seventeenth-century Holland, The Art of Describing, showed how pictures peculiarly cast the world.41 Any historical analysis of a pictorial culture, she argued, needs to be routed through an understanding of the special conditions of picture-making. The Northern, ‘descriptive’ painter in particular insisted on freedom from the expectations and exigencies of texts and their readers. Altdorfer certainly resisted texts, if anything even more so than Alpers’s Dutch painters a century later. His work is equally poorly served by hermeneutic methods developed for the study of Italian narrative art. But Altdorfer was not a descriptive artist either. He did not seek meaning in the surfaces and textures of objects around him. Like many German painters he had another ambition: self-manifestation in the picture, through idiosyncratic line and generally through sharp-edged disregard of the criteria of optical verisimilitude. Michael Baxandall initiated one line of historical inquiry into the German ‘florid style’ in his Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany.42 Baxandall compared the sculptors’ gratuitous elaboration of drapery lines to the preoccupation of the Meistersinger with melodic inventiveness and originality. The stylistic ambition, which almost literally ‘flourished’ in the decades immediately preceding the German Reformation, in the generation of Dürer and Altdorfer, cuts across the dichotomy of description and narration. It reveals another dimension of Northern art altogether. Description and narration are terms derived from Neoclassical literary theory.43 Neither mode acknowledges, or has any particular use for, the so-called ‘deictic’ utterance, the utterance that calls attention to the circumstances of its own physical production. In linguistics, a deictic sign is a grammatical element (an adverb, a verb tense) which places the source of the utterance in some spatial or temporal relationship to the content of the utterance. A fictional character or a narrator engages in deixis by embedding information about the context of a statement within the very form of the statement.44 Norman Bryson has complained that modern professional art history, uncritically acquiescent to received Christian and Neoclassical theories of the image, ignores the deictic reference.45 Those theories, he argues, were excessively concerned with an image that simulated optical impressions of space. They legislated an effacement of the picture surface, and then set the fictive space to the task of narration. Bryson proposed, and has practised, an alternative history of the somatic gesture preceding the picture: painting as a performing art, as it were. But Bryson overstated his grievance. It is true that art-historical scholarship has been excessively enthralled to the theologians and the rhetoricians. The paintings themselves, on the other hand, are not such assiduous propagandizers against the deictic interpretation. Nor has the best writing on Northern art been negligent. The ambitious German Renaissance artist deliberately packed his pictures with deictic markers. And no theorist was exhorting Altdorfer to abolish the material picture surface.

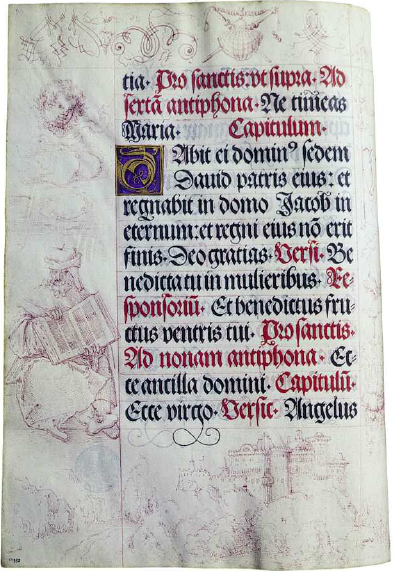

14 Albrecht Altdorfer, Castle Landscape, c. 1515, pen and pale red ink on parchment, from The Prayer Book of the Emperor Maximilian, size of page 27.7 × 19.3. Bibliothèque Municipale, Besançon.

The project of distinguishing a Northern from a Mediterranean practice of painting provides one historiographical framework for this study. Another is the recently renewed recognition of the persistence and charisma, in late medieval and Renaissance painting, of the icon. The Christian imago, the portrait of the sacred personage, was the institutional source and structural model of every independent painted panel. In a series of radically original inquiries into fourteenth- and fifteenth-century panel painting, Hans Belting has explicated the rhetoric of the early modern image as a set of responses to the prescribed and remembered functions of the Christian image. In an essay on Giovanni Bellini’s Pietà in the Brera, for example, Belting shows how the medieval functional and formal categories imago and historia became the field for an overwrought professional rivalry among the outstanding painters of the late fifteenth century.46 Bellini and Mantegna were competing for the attention of the most exacting northern Italian collectors. Belting recapitulates the successive fine-tunings of the pictorial categories: garrulous narrative was trimmed to an iconic core; the imperative and static image was then in turn reanimated in order to pull it back from iconicity. Out of this dialectic emerged a class of pictures whose consanguinities with the most ancient Christian images were at once more conspicuous and less binding than ever before.

A parallel track has been laid out by Joseph Leo Koerner in his work on Dürer’s frontal Self-portrait in Munich.47 Koerner shows how immemorial Christian concerns about the authenticity of sacred portraits framed that portrait, ceremoniously inscribed and dated 1500. Frontal portraits of Christ, in medieval tradition, all derived from an authentic original fabricated by direct physical contact with Christ’s face. All such portraits shared in the prestige of the acheiropoeton, or the image made ‘without hands’, without the unreliable intervention of a human artist. Dürer thus commits a momentous double hubris: in the Self-portrait he places his own face, clear-eyed and bearded, in place of Christ’s; and he competes with the perfection of divine fabrication by scrupulously concealing the trace of his own hand in the paint surface. Paint in this picture is a perfect match for the textures of hair, skin and fur; there is no visible remainder that can be attributed to ‘style’. But this tour de force of self-concealment, which explicitly refers to the virtuosity of the Netherlandish pioneer of oil technique, Jan van Eyck, is itself the most spectacular possible boast and self-advertisement. Dürer submerges the trace of his brush hand; but then he raises his left hand – which is reversed in the mirror and thus looks like the right hand in the finished self-portrait – into the picture field, an emblem of the real subject of the portrait, the source of Dürer’s fame, his performance.

The icon held the Christian beholder in a dialogue. It placed the beholder before the image of an other. The independent painted panel, descendant of the icon, became a principal venue for the Northern artist’s presentation of self because it was the place where the beholder was most keenly and unavoidably aware of the artist’s presence. That presence was always threatening to interrupt the dialogue between mortal and immortal. Thus the history and structure of the independent panel, and the theology of the Christian devotional image, become major contexts for Altdorfer’s landscapes.

It is not difficult to situate Altdorfer within a contemporary discourse about the function and structure of the devotional image. He was living through the most tempestuous crisis of the Christian image since the eighth-century Byzantine iconoclasm. The utility and propriety of traditional religious imagery had become the subject of vituperative public debate in southern German cities. Like other German artists, Altdorfer was pressed into a political role. In 1519 and 1520 he supervised the production of devotional images commemorating a miracle performed by the Immaculate Virgin in Regensburg. The images became the focus and the fuel for a massive pilgrimage. Thousands worshipped and purchased Altdorfer’s woodcuts and metal badges. The credulity and superstition of these pilgrims, and the fervid commerce of images, appalled many observers and helped to shift opinions in the direction of Lutheran and Zwinglian reform. The first iconoclasm provoked by the Reform took place in Wittenberg in 1521; many similar episodes, orderly and violent, followed. And by the 1530s, long after the Marian pilgrimage had been discontinued, Altdorfer as a city councillor was actually encouraging the introduction of Lutheranism to Regensburg. Traditional Christian iconography was eventually either discredited or placed on the defensive in southern Germany. It was left to the secular works – pagan and historical subjects, portraits, so-called ‘genre’ painting, and landscape – to assert the innocence of painting.

The independent image was thus by no means to be taken for granted. The professional painter trying to pursue a career in this stormy climate had to secure his audience, and one way of doing this was to address that audience directly. Style – the heteroclite and unrepeatable mark – fixes the beholder’s attention. The deictic trace implores the beholder to stay within the frame, to resist turning elsewhere for a narrative or a context that will justify the picture. This is essentially what Altdorfer was doing in his own time: authenticating the image with a rhetoric of personality that was only legible within the image. With his style he began to shift the project of self-presentation away from a sheer display of technical prowess towards a more complex manifestation of interpretative nuances: the capacity to make fictions, the assumption of a distinctive authorial tone. The act traced by style became an act of judgement as much as a physical stroke. But style still pointed back to a moment of execution, and the pointer has stuck to the work. Altdorfer’s most aggressively stylish pictures, including the independent landscapes, have also proved unusually intractable to historical explanation. Iconography, format and function of a picture are more manifestly susceptible to external or material pressures. The artist’s characteristic contribution to the picture, on the other hand, is irreducible and exempt from any possible causal explanation. Casting that contribution as a somatic gesture rather than as an intellectual design does not simplify matters. It is style that makes Altdorfer’s landscapes so distinctive in tone and texture, so different from anything else around them, and indeed so different from one another. Most contextual interpretations – sociological, for example, or intellectual-historical – have quickly run up against their own limits.

This book will instead direct questions from within the history of German painting, and particularly from within Altdorfer’s career. It begins by asking where landscape belonged physically and what formats and forms landscape took. It then asks what a picture was and how it could ever be self-sufficient; it tries to explain the structural and evolutionary relationships between independent landscape and pictures with subject-matter; it addresses the connection between the incipient category ‘work of art’ and a stable concept of the frame. All this ‘philological’ groundwork is laid out in the rest of this chapter and in the next. Chapter Three reads the paintings and watercolours as representations, carried out on more than one semantic level, of a native or regional landscape. The forest appears in these pictures simultaneously as a potential refuge from orthodox but idolatrous cult practices, and as the mythical setting of heathen idolatry. The landscapes themselves, finally, refer formally to older Christian images and thus complicate any claim that landscape as a genre may be making to doctrinal innocence. Chapter Four, on the pen-and-ink landscape drawings by Altdorfer and his colleague Huber, analyses the tension between the task of topographical description and the stylistic and fictional imagination. These drawings, but even more so the etchings discussed in chapter Five, mark the establishment of a secular culture of amateurism and collecting. Altdorfer’s landscape etchings were mechanical reproductions of pen drawings. The trace of the artist’s hand is visible but no longer present in the work. Moreover, the etchings reintroduced, through their horizontal format, an epic dimension to landscape. These etchings were the only real bridge linking Altdorfer’s experiment to the next generation of German landscapists, and ultimately, through Bruegel, to the future of landscape.

Where landscape could appear

‘Independent’ is really a negative description: it tells us more about what Altdorfer’s landscapes are not than about what they are. The independent landscape is, first of all, a complete picture not physically connected to any other picture. It is neither an element of a decorative scheme, such as the painted wall of a villa, nor part of an illuminated manuscript. It appears neither on the shutters of an altarpiece or a portrait, nor as the mere background of a narrative composition or a portrait. The independent landscape makes a clean break with the topological conventions of the dependent landscape. But it is not an unpredictable break: it follows already visible fault lines.

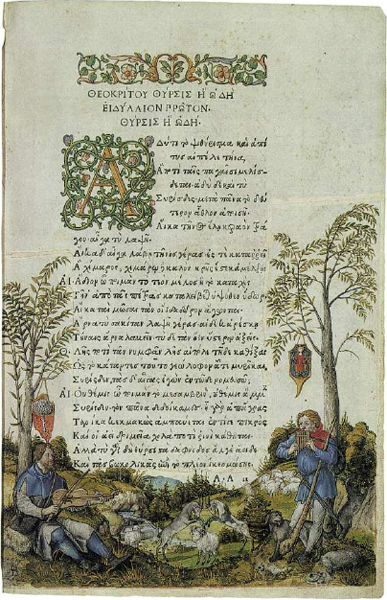

15 Albrecht Dürer, Shepherds Making Music, miniature on parchment, pasted into a printed edition of Theocritus, Venice, c. 1495-6, size of printed page 31.1 × 20.2. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Woodner Collection.

Landscapes in the late Middle Ages appeared above all on walls, either in tapestries or mural paintings. By the fifteenth century painters could confirm the antiquity of the practice by consulting Pliny’s Natural History. The first-century Roman fresco painter Studius (or Ludius) had painted – in Lorenzo Ghiberti’s paraphrase – ‘landscapes [paesi], seas, fishermen, boats, shores, greenery.’48 But nearly all the works inspired by such texts have perished. An inventory of 1492, for example, reveals that the Medici owned some large Flemish paesi on canvas.49 But tapestries, paintings on cloth, and domestic frescoes were particularly vulnerable to depredations of climate and shifts in taste. This is a chapter of the history of European art that will never be written.50 Among the best surviving mural landscapes are the festive and hunting scenes at Runkelstein (Roncolo) near Bolzano, and the cycles of the months in the Torre Aquila at Trent, both dating from c. 1400. The frescoes at Trent, visible through an illusionistic loggia, were commissioned by Bishop George of Lichtenstein, probably from a Bohemian painter (illus. 16).51 Horizons are kept high to make room for as much earthly business as possible: mowing, raking, scythe-sharpening, fishing, love-making, all in the month of July. Hartmann Schedel, the learned author of the Nuremberg Chronicle, once described a series of murals he saw in a monastic library in Brandenburg in the 1460s.52 A scene labelled ‘Agriculture’ looked like a Garden of Love; ‘Hunting’ was set in a dense grove; both scenes fell under the category of Mechanical Arts. The pretext of these long-lost frescoes was didactic, but the treatment, according to Schedel’s ekphrases, was highly pictorial. Swiss and Alsatian tapestries, meanwhile, described the domestic and public misadventures of the sylvan Wild Man.53 All these scenes retained some narrative or allegorical dimension. They described social types from opposite ends of the spectrum of wealth and elegance, and they described human activities, both work and leisure. Good painters did not disdain the decorative landscape. Vasari described the loggia that the Perugian Bernardino Pinturicchio painted for Pope Innocent III in the 1480s as tutti di paesi. . . alla maniera de’ Fiamminghi, ‘which, as something not customary until then, pleased very much.’54 Some walls were simply decked with trompe-l’oeil foliage. Leonardo himself, in 1498, painted a pergola of tangled vines and branches on a vaulted ceiling in the Castello Sforzesco at Milan; on the wall he exposed a miraculous cross-section of rocky subsoil intercalated with roots and a hollow-eyed cadaver.55

16 Bohemian master(?), July, c. 1400, fresco, Torre Aquila, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Trento.

Landscapes in illuminated manuscripts usually replicated the types and themes of the wall scenes. But others were truly empty. This extraordinary material has never been properly surveyed. Already in the 1320s the Parisian miniaturist Jean Pucelle had evacuated his spare, schematic landscapes on the calendar pages of a Book of Hours, illustrating the passage of the Seasons not by the cycle of human labours, but by the clothing of the earth itself.56 A Bruges master, perhaps the Master of Mary of Burgundy, painted in a Book of Hours of around 1490 a series of rural landscapes with signs of the zodiac in the skies.57 A rural landscape is painted on the first page of a fragmentary Prayer Book in the manner of Alexander Bening from the early 1490s.58 The Prayer Book of James IV of Scotland in Vienna contains twelve half-page landscapes, again with zodiac signs, executed by a painter of the Ghent–Bruges school between 1503 and 1515.59 Otto Pächt has traced at least some aspects of this sudden Franco–Flemish fascination with the earth’s surface back to naturalistic northern Italian illustrations of herbals and bestiaries.60

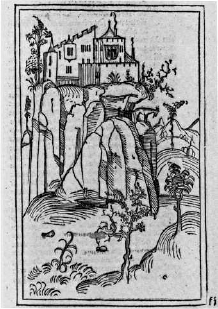

Manuscripts furnished various pretexts to paint empty landscapes. In Bartholomeus Anglicus’s De proprietatibus rerum and other high-medieval encyclopaedias, the sections on materials and elements, birds, trees, the seas, the earth and the provinces of the world were frequently illustrated with schematic landscapes. Many of these were carried over into the illustrations of the earliest printed versions, like the woodcut from the section of Bartholomeus Anglicus on ‘Water and its Ornaments’ in an English edition of 1495 (illus. 17).61 Herbals or medical handbooks also depicted depopulated places. A manuscript Tacuinum sanitatis in Liège, originally produced in Lombardy in the late fourteenth century, offers a spare and empty landscape under the heading ‘Snow and Ice’, alongside the customary wheatfields and orchards.62 In topographical treatises and travel descriptions, columns of text were increasingly interrupted by pictorial maps. The most spectacular were the woodcut urban panoramas in Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam, printed in Mainz in 1486, and in Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, with 1,809 woodcuts printed from 645 different blocks (illus. 36).63 Some of the simplest topographical woodcuts were also the most picturesque, for instance the view of Castle Langenargen on the Gaisbühel, recently built, in Thomas Lirer’s Swabian Chronicle, published in Ulm in 1486 (illus. 18).64 Around 1508–9 Hartmann Schedel pasted a miniature painted in bright matt blues and greens into his manuscript copy of the pilgrimage report of the Dominican Felix Fabri. Framed with red bands and captioned in the margins by Schedel himself, the miniature portrays Mounts Horeb and Sinai in the Holy Land (illus. 19).65

17 English master, On Water and its Ornaments, woodcut, 15 × 15, from Bartholomeus Anglicus, De proprietatibus rerum, London, 1495. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Otto Pächt called attention to a remarkable miniature landscape illustrating a topographical text produced in Bruges c. 1470 (illus. 20).66 The scene is nothing more than a vignette of ideal rural existence, complete with a cripple, a mounted knight, windmills and watermills, and a very thin, gabled building, all laid out along trim orthogonals. Detail does not imply specificity: the scene is no portrait of a real place, but is in fact an adaptation of a landscape setting from an earlier narrative illustration. The desire to construct appealing landscapes took root even in the most arid textual environments. As Walter Cahn has pointed out, there is no a priori obligation to sever the medieval descriptive or classificatory impulse from more affective, even if poorly articulated, attitudes towards the outdoors.67

18 German master, Castle Langenargen, woodcut, 18.8 × 11.9, from Thomas Lirer, Chronik von allen Königen und Kaisern, Ulm, 1486. Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University, New Haven.

19 German master, Mounts Horeb and Sinai, before 1508–9, miniature from a manuscript copy of Felix Fabri’s Evagatorium, vol. 2, owned by Hartmann Schedel, 10.9 × 7.8. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Some illuminators seized any pretext to frame a landscape. An agrarian panorama painted in Regensburg in 1431, with trapezoidal fields and a heap of prismatic rocks, actually illustrates a moralistic text about larks (illus. 21).68 Other book painters exploited the lower margin or bas-de-page. Innovations, in Pächt’s phrase, often appeared first at the point of least resistance.69 The bas-de-page opened up when miniaturists converted the lower edge of the frame, wound with schematic leaves or rinceaux, into a ground plane. Suddenly blank page signified space.70 Jan van Eyck in the Turin Hours (early 1420s), stretched a Baptism of Christ into a cool river landscape along the bottom of a page.71 Altdorfer, too, when asked by Emperor Maximilian to make marginal drawings for a printed Prayer Book, took advantage of the lower strip to draw a landscape – a spectral massif of turrets and crenellations on a rocky hill – in pale red ink (illus. 14).72

Occasionally, empty landscapes found their way into the marginal zones of altarpieces. They became part of the diverse apparatus that surrounded the painting at the centre of the altarpiece. A long, low frieze of mountains serves as the predella or base to Lorenzo Lotto’s Assumption altar in the cathedral at Asolo, dated 1506 (illus. 22).73 The landscape measures 25 × 146 centimetres, and includes a chapel on a hill, a walled city with a citadel and, on the lower edge, a row of still-lifes: two quails, a sprig of flowers supporting a butterfly, a crayfish and two partridges. The predella is treated as if it were part of the frame; for Gombrich this explained the simulation of intarsia or inlaid wood in the foreshortened terrain.74 This appears to be the only uninhabited landscape in an Italian predella. A restoration report of 1822, however, suggested that the Asolo panel is actually a Baptism of Christ with its middle section removed, and that it originally belonged to another, wider, altar that was not by Lotto at all.75

20 Flemish master, Flemish Countryside, c. 1470, 16 × 22, miniature from Cotton MS, British Library, London.

Narrative scenes painted on predellas, like the sabotaged Baptism, were indeed often unified by landscape settings. Horizontal strips of landscape were frequently painted along the lower edge of the altar painting itself. Karel van Mander in 1604 described a work he knew by the fifteenth-century Dutch painter Albert van Ouwater: ‘at the foot (voet) of the altar was a pleasant (aerdigh) landscape in which many pilgrims were painted . . .’.76 The altar is lost, but the scene may have been a detached predella. A sixteenth-century chronicler reported a watercoloured Hell on the voet of the van Eycks’ Ghent altarpiece; no one can agree whether this was a predella or an antependium, that is, a cloth or panel hanging from the altar table itself.77 In a Sicilian–Venetian altarpiece of 1489, the Madonna of the Rosary in Messina by Antonello de Saliba, a landscape panel is physically inserted into the bottom of the main composition. This picture within a picture represents a city against a backdrop of mountains. The landscape, or the panel, is watched over by angels holding a propitiatory banderole, and is not spatially coordinated with the rest of the scene at all.78

21 German master (Regensburg school), Landscape with Larks, c. 1430, miniature from manuscript of Hugo von Trimberg, Der Renner, size of page 40.8 × 28. University Library, Heidelberg.

22 Lorenzo Lotto(?), Predella from Assumption altarpiece, 1506(?), oil on panel, 25 × 146. Cathedral, Asolo.

23 Albrecht Dürer, Madonna and Child Above a Rocky Landscape, c. 1515, woodcut, diameter 9.5, height 14.9. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

‘Internal’ predellas – strips of landscape at the lower edge of an altar painting, inside the frame – often represented the earthly realm in contradistinction to a heavenly event hovering in the sky. Dürer used the device in his Landauer altarpiece of 1511, and Altdorfer in a panel now in Munich, a Madonna and Child among angelic music-makers borne on a cloud above a mountain landscape.79 In Altdorfer’s picture, the emblem of heaven’s eclipse of the world is a fir-tree brutally truncated by the sacred cloud. Dürer around 1515 made a curious woodcut, perhaps an experiment, with a flinty, wedge-shaped landscape at the lower edge and a Madonna and Child suspended above in a circle (illus. 23).80 Panofsky wondered whether the woodcut was not printed illicitly from two separate drawings by Dürer.81 Many later collectors disliked the effect and cut the landscape away. Lorenzo Lotto himself introduced a clutch of Germanic thatch-roofed farm buildings into the base of the Assumption at Asolo, in the main panel just above the disputed predella. The strip of landscape with woodsmen in Lotto’s Sacra Conversazione in Edinburgh, bizarrely, runs across the top of the composition.82

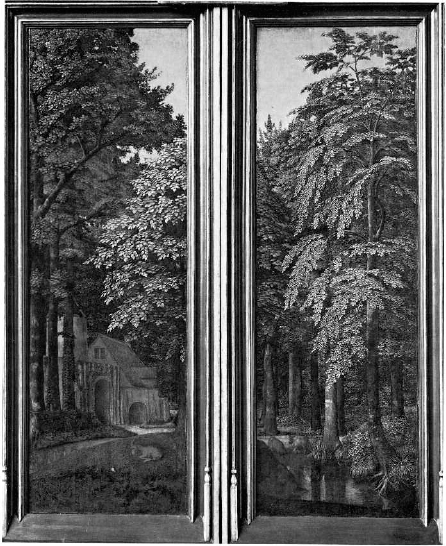

The backs of altarpieces and altar covers also became breeding grounds for unorthodox pictorial and iconographic themes. These surfaces were separately framed but still physically attached to the primary picture. The backs of many fifteenth-century German altars – for example the altar by Wolgemut, Dürer’s teacher, at Zwickau in Saxony – are coated with mazy coils of painted foliage.83 The reverse of the Uttenheim Altar of c.1470, south Tyrolean work close to Michael Pacher, combines foliage with a portrait of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, a devotional subject also found frequently on the backs of altars, as if taking refuge from the chaotic grid of the narrative sequences on the front.84 Hans Memling painted two tall, bushy landscapes inhabited by cranes and a fox on the backs of a pair of panels representing saints, the wings of a lost small altarpiece.85

Around 1511, on the back of the wings of a triptych now in Palermo, the great Antwerp master Jan Gossaert painted a Paradise with Adam and Eve, a subject that could never take over the centre of an altarpiece.86 It is as if the outside surface of the closed wings only half-belonged to the triptych as a whole, and incompletely shared its function; the outside enjoyed iconographic license and could thus represent a realm prior to and outside of sacred history. Altdorfer, too, painted a prelapsarian landscape: Adam and Eve in a feathery forest on the outside wings of a triptych, the ‘regiments’ of Bacchus and Mars on the insides. The central image of the triptych – the portrait of a humanist, or even a mythological subject, the core of a possible ‘pagan altarpiece’ – is lost.87 Most remarkably of all, Gerard David of Bruges painted at some point in the 1510s two vertical forest landscapes on the outsides of the wings to a Nativity altarpiece (illus. 24).88 In the left panel David depicted a cottage and an ass, in the right panel two oxen drinking at a pond. No one has been able to explain these landscapes. If this is Paradise, where is the first couple? Perhaps the wings represent the resting place of the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt, the episode that immediately preceded the Nativity. The ass and the ox belonged to the conventional bucolic audience of the Nativity; sometimes they were differentiated as symbols of Old and New Testament, although not conspicuously in the Nativity behind these wings.89 Perhaps David liked the effect of an empty, leafy space waiting at the end of an arched, sun-dappled, forest-like nave, as if he were inviting a beholder to enter a numinous grove. Esther Cleven has recently proposed that David, who habitually painted tall, billowing trees in the backgrounds and margins of his altars and devotional panels, was offering the landscapes as a kind of signature or trademark. The wings referred well-informed beholders to other pictures, including various versions of the Rest on the Flight, by David.90

24 Gerard David, exterior wings of Nativity altarpiece, 1510s, oil on panel, 90 × 30.5. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, on loan to the Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Angelica Dülberg has recently assembled a huge repertory of eccentric subjects and motifs – still-lifes, emblems and devices, allegorical figures in landscapes – painted on the backs and on the covers of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century portraits.91 A portrait by Memling in New York of a young woman standing at a window, for example, was attached to an upright landscape now in Rotterdam with a pair of horses and a monkey.92 At least one of Lorenzo Lotto’s small painted allegories was a portrait cover (see p. 58). A seventeenth-century inventory describes a lost work by Dürer with a ‘landscape, a hunting-scene, lovely foliage’ and two women holding the arms of the Pirckheimer and Rieter families, painted on parchment pasted on panel. The panel may originally have covered a portrait diptych of Willibald Pirckheimer and his wife Creszentia Rieter that was executed sometime between 1495 and 1500.93 Portrait covers were places where iconography could run wild.

But most landscapes in this period simply appeared in the backgrounds of other paintings. The word landscape in Renaissance texts most frequently refers to an area within a panel painting, such as the background of a narrative composition or a portrait. Pinturicchio, for example, agreed in a contract of 1495 to paint ‘in the empty part of the pictures – or more precisely on the ground behind the figures – landscapes and skies.’94 An early altar contract from Haarlem stipulated that ‘the first panel where the angel announces to the shepherds must have a landscape’.95 Dürer referred routinely to the ‘landscapes’ in two sacred pictures in letters of 1508 and 1509 to his patron Jakob Heller.96 A contract for an altarpiece in Überlingen on Lake Constance from 1518 specified that the Landschaften in the scenes on the wings be painted in the ‘best oil colours’.97 In Leonardo’s notebooks, paese refers to countryside itself as an object of imitation, but at least in one case means the landscape within the picture.98 Dürer, too, according to Willibald Pirckheimer’s afterword to the Four Books on Human Proportion (1528), had planned to write about landscape.99

Painting backgrounds was a specialized skill. Workshops collected model drawings of landscape motifs which were later copied into paintings. Nuremberg and Bamberg workshops in Altdorfer’s time, for instance, preserved accurate drawings and watercolours of local buildings and skylines and inserted them in the backgrounds of altar paintings (see pp. 243–9 and illus. 69, 146–50). Italian amateurs of painting had long admired paesi ponentini: ‘Western’, or Flemish, landscapes.100 The antiquarian Ciriaco d’Ancona saw a painting by Rogier van der Weyden in the 1450s and marvelled at the ‘blooming meadows, flowers, trees, and shady, leafy hills’, as if Mother Nature herself had painted them.101 Some Italian workshops employed Netherlandish specialists to paint landscape backgrounds. According to Vasari, Titian kept several ‘Germans’ (presumably Flemings) under his own roof, ‘excellent painters of landscapes and greenery’.102 Flemish landscape backgrounds were so admired that some Florentine artists copied them directly into their own works. Botticelli enlarged the background of Jan van Eyck’s Stigmatization of St Francis, a tiny devotional panel that survives in two versions, in Turin and Philadelphia, and adapted it to his Adoration of the Magi in London.103 In the 1490s the Florentine Fra Bartolommeo copied a landscape from a Madonna and Child by Hans Memling (illus. 25), directly into his own Madonna and Child.104 One Italian miniaturist actually detached Memling’s landscape from its composition and presented it as a picture in its own right (illus. 26). The Flemish vignette, with half-timber watermill and a serpentine brook, becomes in the Zibaldone or ‘commonplace book’ of Buonaccorso Ghiberti (grandson of Lorenzo) an illustration to a discussion of the casting of bells. The copyist, probably Buonaccorso himself, merely subtracted Memling’s swans and added a pair of smelting pots in the right foreground as the iconographical pretext.105 The landscape backgrounds of Dürer’s engravings proved the richest lode of all. Marcantonio Raimondi, Cristofano Robetta, Nicoletto da Modena, Zoan Andrea, Giulio Campagnola and Giovanni Antonio da Brescia all transplanted trees and buildings from Dürer into their own engravings.106 Even Vasari relished the ‘most beautiful huts after the manner of German farms’ in Dürer’s Prodigal Son engraving.107

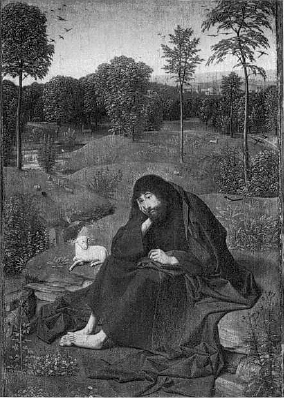

The next step for some Flemish painters was to let the setting dominate the picture, and indeed to make setting into the basis for the classification of the picture. Joachim Patenir of Antwerp, emboldened by the Italian taste for Northern rusticity, began as early as the 1510s to expand the backgrounds of his paintings out of all proportion. Patenir and many followers in Antwerp over the next decades painted horizontal panoramas of fantastic landscape seen from a bird’s-eye view. A painting like the Rest on the Flight in Madrid technically still had subject-matter. But it violently reversed the ordinary hierarchy of subject and setting (illus. 28).108 Indeed, in at least one case – the Temptation of St Anthony, also in Madrid – Patenir painted the landscape but left the foreground figures to his friend Quentin Massys.109 Patenir converted a workshop speciality into a livelihood and a reputation. Dürer met Patenir in 1521 while travelling in the Low Countries and referred to him in his journal as ‘the good landscape painter’.110 Moreover, the Italian enthusiasts of Netherlandish painting did not hesitate to describe pictures which still had recognizable subject-matter as landscapes. The term was even extended to earlier pictures. The Venetian patrician and amateur Marcantonio Michiel saw in 1521 an entire group of tavolette de paesi attributed to Albert of Holland, presumably the early Dutch painter Ouwater.111 These were not independent landscapes by any means, not even panoramic landscapes with diminished subjects, but probably small devotional panels with notably green backgrounds, much like the moody portrait of St John the Baptist in the Wilderness (illus. 27) by Geertgen tot Sint Jans, a younger contemporary of Ouwater, also of Haarlem.112

25 Hans Memling, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, c. 148os(?), oil on panel, 57 × 42. Uffizi, Florence.

26 Italian master, Casting of Bells, c. 1472–83, miniature, from the zibaldone of Buonaccorso Ghiberti. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence.

27 Geertgen tot Sint Jans, St John the Baptist in the Wilderness, c. 1475, oil on panel, 42 × 28. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. |

|

Much innovation in the history of art involves excavating subjects and ideas from hidden or marginal places and throwing them out onto a public surface, a prestigious surface. Many of the painted proverbs of Hieronymus Bosch, for example, enjoyed a clandestine prior existence in the margins of manuscripts or among the carved misericords on the undersides of choir-stalls.113 The mechanics of the relocation of the landscape – the promotion of the landscape from the margin to the centre – will be the subject of chapter Two. This promotion was accomplished first by assigning the landscape a name, and thus an invisible and virtual frame, and then by sealing it off from texts and other pictures with a physical frame.

28 Joachim Patenir, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, oil on panel, 121 × 177. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Landscape and text

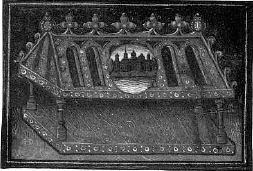

Max J. Friedlander, who in 1891 published the first book on Altdorfer, later wrote that ‘in the Netherlands we can, if put to it, trace the germination and efflorescence of landscape as an historical process – at least we are impelled to make the attempt’. But, he conceded, ‘faced with south German art, the historian lays down his arms’.114 There are a number of reasons for this. Interpretation of the Netherlandish landscape has been facilitated by its affinities with conventions of mapmaking.115 Artists used to make symbolic world maps by dividing a circle into three horizontal bands standing for sea, land and sky. Pisanello, in the mid-fifteenth century, put such a shorthand map on a bronze medal – once again, the verso of a portrait. The circle reduces the vast globe, symbol of the worldly dominion of the sitter, Don Iñigo d’Avalos, to a wavy sea, a strip of cities and pointed mountains, and a starry sky (illus. 29).116 The tiniest world map of all, another aerial – urban – aquatic abbreviation, appears in a Dutch manuscript of 1431 (illus. 30).117 This is a medallion painted on the imaginary sarcophagus of Darius described in the vernacular legend of Alex ander the Great. The text reports that Apelles, no less, ‘installed the round world’ on this tomb, and ‘made and engraved all the cities that were there, and all the rivers, and all the people that lived there; and those languages that were spoken there, and the great water inland; and also all the islands of the sea and what they are called’. On the manuscript page the medallion measures less than two centimetres across. The fifteenth- century Flemish panel painting would clear considerably more room for its microcosms.

Both the steady, earthbound eye of the urban topographer and the imaginary vantage-point of the pictorial map implied an intellectual grasp of terrain, the knowledge of the geographer or the cartographer. This was not a textual function; on the contrary, the topographical picture exploited a capacity of images that language could never rival. But it was a function textual culture could acknowledge. Literary humanists praised and justified painting as an instrument of knowledge: in 1336 a lettered Venetian referred to a cache of papers containing a picture or plan (une figure) of Florence by Giotto;118 almost two centuries later Raphael undertook a monumental pictorial catalogue of Roman antiquities. The humanist Bartolommeo Fazio described in 1456 a ‘circular representation of the world’ painted by Jan van Eyck for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, which was presented to King Alphonso of Aragon. In this work, ‘more perfect than any of our age’, one distinguishes ‘not only places and the lie of continents, but also, by measurement, the distances between places’. The Eyckian mappemonde was probably a bird’s-eye panorama of a slightly convex terrestrial surface, and may have been overlaid with Ptolemaic longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates.119

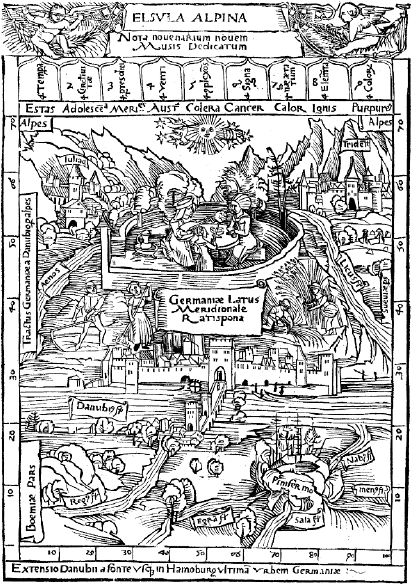

This is not to say that the Germans neglected cartography. Martin Behaim of Nuremberg constructed the very first globe – his Erdapfel, or ‘earth-apple’ – in 1491–2.120 Dürer, in one of the drafts for the introduction to his treatise on painting, claimed that ‘the measurement of the earth, the waters, and the stars has come to be understood through painting’.121 Dürer may have encountered the thoughts of Leonardo, who had boasted in his own unpublished treatise that painting, ‘by virtue of science, shows on a flat surface great stretches of country, with distant horizons’.122 In 1515 Dürer published a woodcut projection of the globe and a pair of star charts for the imperial astronomer Johann Stabius.123 Veit Stoss, the Nuremberg wood sculptor, showed his carved and painted mappa, possibly the earliest full-relief landscape model, to the calligrapher and art-historical chronicler Johann Neudörfer.124 Literary culture paid tribute to this notational capacity by comparing its own verbal descriptions to pictures. Humanists in Dürer’s and Altdorfer’s time conventionally held up the panel painting as a paragonal format for descriptions of the universe, a more adequate medium for this task than language. Conrad Celtis, travelling scholar and poet laureate, compared Apuleius’s cosmographical treatise De mundo, which he edited in 1497, to a small painting or sculpture: ‘they learn, as it were from a small panel or sculpture of words, how and by whom this universe is put together and maintained in its form.’125 Johann Cuspinian, the Viennese poet and physician, promised in his university lectures c. 1506 on Hippocrates ‘to describe, just as the painters do, the entire world on a small panel’.126 Celtis, finally, in the dedication to the Amores, his geographical love poem published in Nuremberg in 1502, promised that ‘our Germany and its four regions’ would be visible ‘as if painted on a small panel’.127 In this case Celtis actually designed for his book, through the agency of Dürer’s workshop, four woodcut panoramas based on astrological calendar scenes. The walled city at the centre of the woodcut introducing book Two – the account of Celtis’s romance with ‘Elsula’ – is Regensburg itself (illus. 31).128

But, in general, the exemplary pictures to which the humanist formulas refer never existed. These passages belong to the general humanist justification of descriptive language under the Horatian motto ut pictura poesis. They sound like disingenuous apologies for a rhetorical topos (the ekphrasis tou topou, or description of place129) or a literary form (the cosmographical treatise) that, in fact, required no apology. They reflect either a general epistemological or pedagogical preference for the sensory over the intellectual, grounded in some version of Nominalism or anti-scholasticism,130 or the more ancient preference for sight over the other senses, formulated by both Plato and Aristotle and invoked by Leonardo and Dürer in their writings on painting.131

29 Antonio Pisanello, portrait medal of Don Iñigo d’Avalos, verso with ‘world map’, c. 1448–9, bronze, diameter 7.7. British Museum, London.

30 Dutch master, Tomb of Darius, miniature from a manuscript Historie des Bijbels, Utrecht, 1431. Bibliothèque Royale, Brussels.