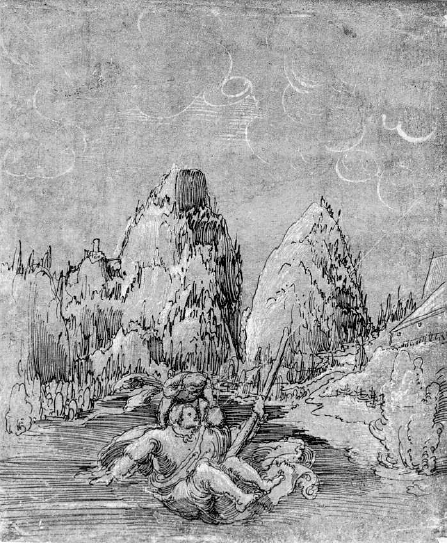

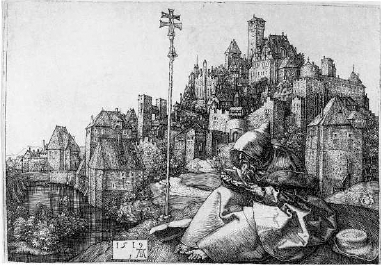

139 Albrecht Altdorfer, St Christopher, c. 1510, pen and white heightening on green grounded paper, 17.9 × 14.4. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

4

Topography and Fiction

Altdorfer’s painted landscapes, his fictional topothesias, were topographically useless. Their verticality controverted the surface of the earth. Goethe said as much about the old Netherlandish landscape painters. ‘Human imagination’, he observed in his Italian Journey, ‘always pictures the objects it considers significant higher, rather than broader, than they are . . . and thus endows the image with more character, seriousness, and worthiness. Imagination is to reality as poetry is to prose; the one thinks of objects as mighty and steep, the other spreads outward in the plane. Landscape painters of the sixteenth century, held up to our landscape painters, give the most striking example.’1

Altdorfer’s landscape drawings in pen and ink, on the other hand, are horizontal in format. Four works survive. Two are travel reports: the View of Sarmingstein in Budapest, dated 1511 (illus. 165), and the Willow Landscape in the Akademie in Vienna (illus. 166). The Coastal Landscape in the Albertina, usually attributed to Altdorfer’s brother Erhard, dates from about a decade later; it is close in spirit to the landscape etchings (illus. 188). The View of Schloss Wörth in Dresden, dated 1524 and lightly watercoloured (illus. 187), is the fourth example. In format and medium these drawings derived from a regional practice of topographical drawing. The earlier pair, fresher and more open in structure, with traces of the traveller’s attentiveness and exhilaration, show the immediate influence of the work of Wolf Huber. Huber left about three or four dozen landscape drawings in pen on white paper, both vertical and horizontal in format; another 75 or 100 sheets are copies after lost originals or inventions in Huber’s manner. The earliest dated drawing by Huber is the Bridge at the City Wall of 1505, in Berlin (illus. 157); the View of the Mondsee in Nuremberg is dated 1510 (illus. 159). Both are signed with initials. They suggest strongly that the original decision to frame the landscape and offer it as an independent landscape drawing was taken by Huber in the first decade of the century.

Huber did not arrive at the empty landscape by excluding subject-matter, but rather by offering topography as a picture. Huber’s reconstitution of the image of the outdoors was comparable in procedure to Altdorfer’s. He did it by fashioning his topographical views into compositions, that is, by subjecting them to the familiar conventions of two-dimensional organization. He also did it by presenting his pen line as the mark of a recognizable personal style; indeed, he monogrammed and dated many of his landscape drawings. Altdorfer took up the idea at once. The hypothesis of a meeting between the two in 1511, during a journey down the Danube by Altdorfer, is still a good one.

The story of Huber’s invention and its success deserves an expansive treatment, but here it will have to be summarized. Wolf Huber was born in the Vorarlberg, probably in the mid-1480s, and settled in Passau sometime after 1510.2 Not a single surviving painting predates the 1515 contract for the St Anna altar in Feldkirch.3 It appears that Huber’s career, too, was built on paper. His earliest works are pen drawings on coloured ground in the manner of Altdorfer.4 His first woodcuts, under the impact of both Dürer and Altdorfer, date from around 1511. Huber also produced narrative or hagiographical drawings on plain paper. The earliest is the St Sebastian in Washington, dated 1509.5

The exchanges between Huber and Altdorfer extended over many years, and neither was manifestly more fertile than the other. Wolf Huber even made watercolour and gouache landscapes, although none on panel. The Alpine Landscape in Berlin, in watercolour and gouache over pen on paper, is initialled W. H. and dated 1522; the date was at some point, unaccountably, altered to 1532 (illus. 140).6 With its vast, bowed horizon and its marbled sky, this drawing is pitched a rhetorical octave higher than Altdorfer’s watercolours. But Huber has a heavier brush-hand and the landscape is dampened by all the opaque local greens in the foreground. A vertical sheet from the Koenigs collection, lost since 1945, the Mountain Landscape, is also initialled and dated 1522.7 Old descriptions give some idea of the intensity of the colours. The structure – dark repoussoir and mountain view within a narrow vertical format – and the saturated mood, not to mention the date, place it in direct analogy with Altdorfer’s watercolour landscapes on paper. But both these landscapes are larger than Altdorfer’s. Even larger is Huber’s Landscape with Golgotha in Erlangen, a spacious, washy folio filled to the brim like a painting (illus. 141).8 This is a strange, ambitious drawing, finished and yet open-ended. The crosses on the hill and the huge glowing emptiness in the foreground pull the drawing back toward iconography, as if the drawing were merely waiting for Christ Bearing the Cross, with a throng of onlookers, to materialize.9

But Huber’s best graphic ideas were unfurled on plain white paper. His pen was on a tighter leash than Altdorfer’s; it described smaller arcs, turned tighter corners, filled blank space more patiently and thoroughly. Huber’s early pen drawings soon swerved from straightforward descriptive tasks. The tension between stylish line and the prosaic task of topographical description was driven to an extreme in his landscape drawings of the 1510s, as it also was in Altdorfer’s View of Sarmingstein and Landscape with Willows.

The topographical drawing

It is astonishing to discover how seldom Renaissance artists actually took their equipment out of doors, to draw or paint under an open sky. Common sense suggests that they must have done so, for the only prerequisites were good weather and portable equipment. And yet it is amazingly difficult to show that artists did draw out of doors. Even the primary piece of evidence has been assailed: Leonardo da Vinci’s Arno Valley Landscape (illus. 142) in the Uffizi, a pioneering testimony to the Renaissance spirit of direct inquiry into nature.10 The sheet is dated 5 August 1473 in Leonardo’s own hand. But Ernst Gombrich called attention to various spatial inconsistencies in the landscape and to resemblances with formulaic cliffs in the backgrounds of early Netherlandish paintings. He concluded mischievously that Leonardo had worked up the entire view in his workshop, at best from the memory of an outing along the Arno.11 Suddenly, we cannot even be sure that we will recognize the drawing from life when we do come across it.

Plein-air drawing was certainly no ordinary exercise in the Renaissance. Only a few of Altdorfer’s and Huber’s contemporaries, for example Dürer, Fra Bartolommeo, probably Titian, regularly ventured out of doors with pen and paper. There is considerable evidence, however, circumstantial and material, of a German topographical drawing practice in the latter half of the fifteenth century. Accurate topographical reports mostly served practical purposes, inside and outside the painter’s workshop. For example, buildings or terrain were often drawn from life in order to record claims to property. In that case the drawing stood as a finished product, a pictorial document with legal status. Archives are full of clumsy old maps drawn by local painters or even clerks.12 A schematic watercolour map of Regensburg, perhaps connected with a legal dispute over property borders, was entrusted to an artist close to Altdorfer.13 A watercolour and gouache painting in the Ian Woodner Collection describes from an imaginary viewpoint a clutch of high-roofed buildings a farm or a lodge – menaced by a wriggling army of trees (illus. 143).14 The draughtsman who traced these flared roofs and pursued the theme of trunk and crown into every corner was no amateur. The picture must have documented private property. Perhaps it was part of a larger map; this segment was done on four separate sheets of parchment stuck to paper. String holes along the edges indicate that the parchment was plundered from a bound book. The surveyer and cartographer Erhard Etzlaub did similar work for the city of Nuremberg: ‘What was held by my lords the Council in and around the city’, the calligrapher and mathematician Johann Neudörfer confirmed, ‘in flowing waters, roads, tracks, towns, markets, villages, hamlets, woods, rights of jurisdiction, and other excellences, he showed forth for them in the district office in fair maps and pictures.’15 Etzlaub’s Imperial Forests around Nuremberg, also on parchment, takes a still higher vantage point (illus. 93). All these works function as maps but look like pictures. They eschew a strict overhead point of view in order to preserve the more familiar look of things. They are liberal with colour and superfluous detail. The same can be said of the topographical watercolours produced early in the century by Jörg Kölderer of Innsbruck for Emperor Maximilian. Kölderer and his workshop illustrated a pair of military inventories, the Fortifications in South Tyrol and Friuli16 and the Ordnance Book.17 These descriptions of batteries and arsenals are more soberly attentive to detail and structure than the rich and fanciful landscape miniatures of Maximilian’s Tyrolean Fishing Book and Hunting Book. The fortification’s watercolours, for example the description of Peitenstein nestled among jagged crags, are grounded in chalk underdrawings that were executed at the sites (illus. 144).18 These fortifications, often built piecemeal and according to no plan, and perched on irregular and unwelcoming terrain, were not easy structures to draw. Ungainly perspectival solutions and outright failures of pictorial intelligence reveal the difficulty of the task. At the same time, the painter was mindful of his audience. These volumes were meant for the eyes of the Emperor. The green, pink and blue washes made the pages more presentable; so too did gratuitous pictorial touches like vegetation or, in the drawing of Peitenstein, a tiny shrine and crucifix beside the road. The Tyrolean Fishing Book of 1504 is a more splendid affair, executed under the sign of Diana rather than Mars.19 The description of the Achensee, a finger-shaped lake northeast of Innsbruck, fills an entire page (fol. 3v) in true miniature technique, with layers of opaque pigment and shimmering streaks of white and real gold (illus. 145). These are the immediate technical models for Altdorfer’s Triumphal Procession miniatures; in fact, until recently those magnificent landscapes were credited to Jörg Kölderer. The format of the page pushes the lake upwards. For all the fancy brush-work, the scene refuses to leave the page and recede into space. Maximilian himself cradles the prize fish in the lowermost vessel, while his deputies and huntsmen haul the nets and pursue horned game.

140 Wolf Huber, Alpine Landscape, 1522 (later altered to 1532), pen with watercolour and gouache on paper, 21.1 × 30.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

141 Wolf Huber, Landscape with Golgotha, c. 1525–30, pen with watercolour and gouache on paper, 31.7 × 44.8. University Library, Erlangen.

142 Leonardo da Vinci, Arno Valley Landscape, 1473, pen on paper, 19 × 28.5. Uffizi, Florence.

143 German master, A Farm in a Wood, c. 1500, pen with watercolour and gouache with white heightening on parchment; four sheets pasted on paper, 45.7 × 55.6. Ian Woodner Family Collection, New York.

Most topographical drawings were the private memoranda of the painter, destined for transposition to the backgrounds of narrative panels. These drawings are mostly lost. But every reasonably accurate portrait of a celebrated building or a skyline in a painting must have been preceded by a study from life. Netherlanders who embedded urban portraits within a landscape were following the lead of Jan van Eyck. Every painter had seen the towers of the cathedral of Utrecht and of St Nicholas of Ghent in the background of the Ghent altarpiece.20 But the specialists in background topography were the Germans. The skyline of Vienna, for example, appears first of all in the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate in the Albrecht Altar of 1440, at Klosterneuburg, showing the towers of St Stephen’s cathedral and Maria am Gestade, completed in 1428 and 1433 respectively.21 Vienna then reappears in the background of the Flight into Egypt of the Schotten Altar of 1469, in the Schottenstift in Vienna;22 and in the central panel of the Crucifixion triptych of the 1480s, now at St Florian, by a pupil of the Schotten Master.23 One centre of topographical background painting was Nuremberg. Michael Wolgemut, to select one example among many, grafted the Nuremberg castle into the background of a Presentation of Christ on an altarpiece in Straubing (illus. 146).24 Lucas Cranach portrayed his patron’s castle at Coburg, north of Bamberg, in the St Catherine altar, and then repeated the homage in his woodcut Martyrdom of St Erasmus of 1506, where the castle doubles as conventional background motif (as in so many Dürer woodcuts) and as pendant to the coats of arms hanging from the tree at the right (illus. 147).25 Innumerable other passages in German panels certainly reproduce real but vanished buildings.

|

145 Jörg Kölderer, Achensee, miniature from manuscript Fischereibuch, 1504, 32 × 22. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. |

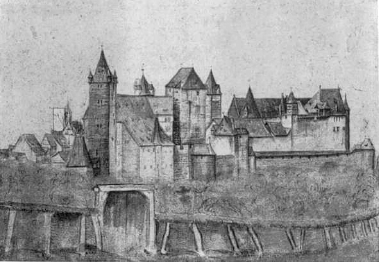

Workshops must have stocked portfolios of local views. Two possible early survivors from Nuremberg are a slightly wobbly view of the castle (illus. 148)26 and a scrupulous transcription of rooftops surrounding the church of St Egidius.27 But a group of six pen and watercolour drawings in Berlin associated with Wolfgang Katzheimer the elder, the leading turn-of-the-century painter in Bamberg, gives the best impression of what the Franconian plein-air drawings must have looked like.28 This is the most important cache of true topographical studies before Dürer. The view of the Imperial and episcopal palace complex on the cathedral hill in Bamberg was drawn before a fire damaged the tower in 1487 (illus. 149).29 This precise view, modified to account for the rebuilding completed in 1489, resurfaces in the background of a panel attributed to Katzheimer,30 in a pen drawing in London related to the painting,31 and in a woodcut of 1509 by Dürer’s pupil Wolf Traut.32 The views of Kloster Michelsberg and the Burggrafenhof, meanwhile, were used in the background of a Bearing of the Cross in St Sebald in Nuremberg, dated 1485.33 These are the only chronological coordinates, and without them the watercolours would be extremely difficult to date. The views are drawn in black and red ink with occasional traces of preliminary black chalk. The washes are red, grey, yellow, blue and various greens. The use of perspective and the attention to detail vary; however, although they may be the work of three different hands, the six sheets surely belonged to the same workshop portfolio.34

146 Michael Wolgemut, Presentation of Christ in the Temple, c. 1480–90, oil on panel, 222 × 147. St Jakob, Straubing. |

|

|

147 Lucas Cranach, Martyrdom of St Erasmus, 1506, woodcut, 22.4 × 15.8. |

There was certainly no requirement that background skylines be derived from life. One group of Franconian landscape drawings in pen, and often with watercolour as well, are simply fantastic, organic elaborations on the themes of castle and city. These drawings may share format and function with the true topographical reports, but they were not executed out of doors. The Landscape with Wanderer, which Dürer adapted in a drawing of his own, reappears in an altar panel in Bamberg (illus. 68, 69; see pp. 125–6). A drawing of a Coastal City in Erlangen surfaces on the horizons of two Nuremberg altarpieces of the 1460s.35 A Mountain Landscape with Castle in Leipzig is exceptionally complete, already a finished drawing.36 The most appealing false topography is the View of a Walled City in a Coastal Landscape recently acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum, a not quite stable collection of mountains and buildings in pen and soft washes (illus. 150).37 The drawing has evidently been cut down from a larger composition study. The towers here vary only slightly from the towers of the Erlangen Coastal City.

What purposes did embedded topographical portraits serve? Some were narrative devices. Accurate reports on familiar and stationary objects vouched for the reliability of the narrator’s reports on more complex objects. Background detail – just like the intrusive foreground trees discussed at the end of the last chapter – contributed to the rhetoric of realism. The success of realist fiction can turn on a thin margin of apparently superfluous information. Embedded topography also nurtured an increasingly sharply defined sense of place, a monumental consciousness. Attention to landmarks – buildings and skylines – formed the pre-history of the grander humanist project of regional and national illustration. And it must simply have given churchgoers pleasure to recognize local landmarks in an altarpiece.

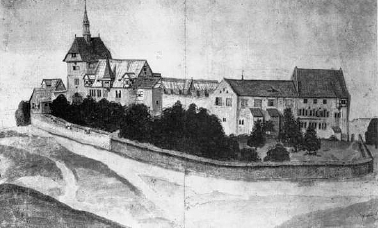

148 German master, View of Nuremberg Castle, early 16th century, watercolour on paper, 14.8 × 21.2. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

There was always plenty of demand for views of cities, local or foreign. The medium of print seemed to lend any representation an aura of authority, and render accuracy unnecessary. A strange metalcut view of an unidentifiable city probably dates from the third quarter of the fifteenth century.38 Many of the urban views of Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle, designed and executed by Wolgemut’s shop, were wholly invented, but many others, like the view of Regensburg, were prepared by pen drawings from life (illus. 36).39 So too were the panoramic views by Erhard Reuwich that were published as woodcuts to Bernard von Breydenbach’s Pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1486. Such woodcut views persisted as basic structural templates for Huber’s and Altdorfer’s pen-and-ink landscapes.40

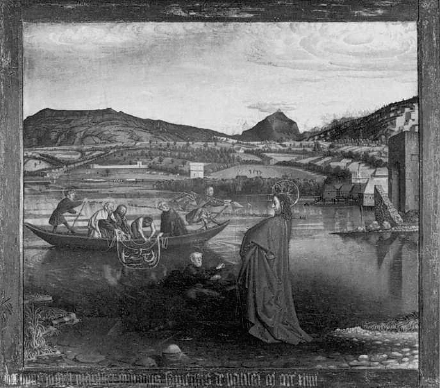

The topographical memorandum did not so frequently embrace mountains, which were more difficult to depict. The great exception is the Miraculous Draught of Fishes by Konrad Witz, an outside wing from the St Peter altar of 1444 in Geneva (illus. 151).41 The picture looks southeast across the lake, toward the peak of Le Môle flanked by the Voirons and the Petit-Salève. Earlier we came across the description of a lost painting by Dirk Bouts, from the middle of the fifteenth century, which portrayed landmarks of Haarlem, among them a tree (see p. 199). Dürer, too, portrayed a particular tree, the Lime Tree in Rotterdam, a magnificent simulation of a mottled, glinting, leafy mass in watercolour and gouache on parchment (illus. 152).42 This is possibly the famous tree on the ramparts of the Nuremberg Castle under which Philipp Pirckheimer celebrated his wedding on 11 March 1455, the very day, in fact, that Dürer’s own father first arrived in the city.43

149 Bamberg master, View of Imperial and Episcopal Palace in Bamberg, before 1487, pen and watercolour on paper, 19 × 47.2. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

150 German master, View of a Walled City in a Coastal Landscape, late 15th century, pen with watercolour and gouache, 7.3 × 13.5. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

For some artists, the process of making the topographical portrait became more interesting than any possible use in a painting. This is evident in Dürer’s Lime Tree, whose ineffable technique, part watercolour and part miniature, would never translate into oil paint. This is what was happening generally in Dürer’s landscape watercolours of the 1490s. The fifteenth-century Franconian topographical drawings, and more especially Wolgemut’s shop practices, stood directly behind Dürer’s travel reports, or his views of places around Nuremberg, such as the Wire-drawing Mill (illus. 153).44 This enormous and extremely still watercolour describes a cluster of buildings on the River Pegnitz just west of the city. The whiteness of the paper slides behind the layers of wash and gouache and illuminates the scene from below. Any patch of this vision is ready for transfer to a painting. But Dürer has knit topography into a landscape. He accomplishes this with colour, with an intellectual grasp of the continuity of terrain, and even with an aesthetic principle, a formal module provided by the steep and slightly flared straw roofs. These are the German rustic roofs par excellence, which we saw already in the Woodner property drawing (illus. 143), and which Vasari praised in Dürer’s Prodigal Son engraving, as ‘most beautiful huts after the manner of German farms’.45

151 Konrad Witz, Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1444, oil on panel, 132 × 155. Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva.

Dürer’s studies are finer and more scrupulous, and at the same time more festive, than their predecessors. They constantly exceed any requirements that practical function would impose. Description has become an end in itself. Dürer’s watercolours were probably not seen by many beyond his shop and circles of friends and supporters. But proof that they were regarded from an early date as self-sufficient pictures is provided by a watercolour cliff study in the Uffizi (illus. 154).46 This work describes a triangular segment of cliff in pale, controlled layers of watercolour. The cubic shelves of rock, and the additive procedure in general, suggest a northern Italian hand, and indeed call into doubt the status of the sheet as a life-study. The watercolour technique and such tactics as the blank sky can only have been learned from the example of Dürer. Perhaps it was even a copy after a Dürer watercolour, left behind in Venice in 1495 and now lost.

152 Albrecht Dürer, Lime Tree, c. 1493–4, watercolour and gouache on parchment, 34.3 × 26.7. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Accuracy – or the look of accuracy – was prized for its own sake. Johann Neudörfer, in his notes on local painters published in 1547, recounted the young Dürer’s peregrinations after his disappointment in Colmar. ‘Even as he travelled further in search of his art’, wrote Neudörfer, ‘he was nevertheless passing his time with counterfeits of people, landscapes, and cities.’47 Later in life Dürer reverted, when executing a landscape, to the classic medium of the fifteenth-century life-study: silverpoint. The silverpoint, a metal stylus with a silver tip, was easier to carry around anyway. On a trip to Bamberg in 1517 Dürer stopped to draw the village of Reuth and its environs (illus. 155).48 Just as in the Wire-drawing Mill, the horizontal is cut by a welter of harsh thatched slopes. Dürer’s pupil Hans Baldung also left a corpus of silverpoint landscapes and views.49 Surviving topographical drawings from the 1520s and beyond suggest that Dürer’s precocious attentiveness to his surroundings was installing itself within normal artistic practice. An unknown, confident hand described the coast of Lake Constance in pen and coloured washes.50 The sheet is inscribed with the place, Goldbach near Überlingen, and the precise date, ‘1522 on St Michael’s Day’: the marks of a traveller. The close-up on the verso is even lovelier (illus. 156). Scribbled notes in the grass and water fix the proper colours; perhaps the artist had a mind to convert the sketch into a more public medium after all. But for the moment the lazy, practiced wanderings of the pen sufficed. Pleasure in the ‘counterfeit’ no longer needed to be justified.

153 Albrecht Dürer, Wire-drawing Mill, c. 1494, watercolour and gouache on paper, 29 × 42.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

154 Northern Italian master, Cliff, late 1490s, watercolour, 20.2 × 27.3. Uffizi, Florence.

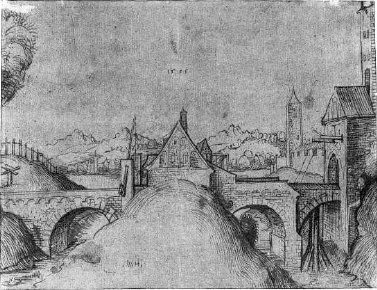

Style in Altdorfer’s pen-and-ink landscapes

Wolf Huber in his earliest dated drawing, the Bridge at the City Wall of 1505, adopted a point of view and a medium proper to the topographical report (illus. 157).51 The technique of dusting or rubbing the paper with a dry powder, usually red chalk or cinnabar, although not mentioned in Cennini’s handbook, was used in Florence from the beginning of the fifteenth century. Red tint was a quicker and cheaper substitute for opaque coloured ground. Germans used it for pen drawings of some degree of finish which were expected to last some time, such as workshop models and sketchbook pages.52 We have already looked at several drawings in this technique: two copies after Dürer prints, the Quarry after the St Jerome, from the so-called Wolgemut sketchbook in Erlangen,53 and the Mountain Landscape after the Visitation (illus. 82, 86, and two landscape drawings usually associated with Erhard Altdorfer (illus. 79, 80). Huber recorded every element of the bridge’s structure and every feature of the terrain behind it. He maintained a stationary standpoint, apparently on a small island in the middle of the river, and dutifully and awkwardly registered the odd foreshortened bulb of earth looming between himself and the gatehouse at the end of the island. But in Huber’s drawing, just as in so many early life-studies, and in Dürer’s watercolours, an initial openness to physical data transforms itself in the process of execution into a will to closure and finish. The Bridge at the City Wall is bracketed at the upper-left and -right by a tree and a tower, at the lower-left and -right by repoussoirs of earth. The bridge itself is outlined twice to distinguish it from the background. When he was finished, Huber did what Dürer almost never did: he dated his landscape.54 The date was apparently not added later, for its line resembles too closely other lines in the drawing. It actually belongs to the drawing, to the composition, as so many of Huber’s dates and monograms will in the landscapes to come.55 This is one of Huber’s earliest drawings (see pp. 239–40). The date marks neither a moment in the history of the depicted city, nor a moment shared between artist and patron (for example, a date on a presentation or contract drawing), nor a precise moment of observation (for example, the date recorded by Leonardo on his Arno landscape), but rather a moment in the career of the draughtsman. The young draughtsman who dates a drawing evinces a certain confidence that he will, indeed, have a career.

155 Albrecht Dürer, View of Reuth, c. 1517, silverpoint on parchment, 16 × 28.2. Missing since 1945.

156 German master, River Bank, 1522, pen on paper, 9 × 14.1. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

In the View of Urfahr, the town across the Danube from Linz, fifty miles downstream from Passau (illus. 158), Huber is even more stubbornly literal than in the Bridge at the City Wall.56 Here he is standing on the ramparts of the castle of Linz, high above the river. Everything is described in an extremely pale monotone. The mountains are shaped not by hatching but by soft, dotted contour lines. But Huber includes within the scene a pair of rooftops rising into his field of vision and eclipsing the brittle bridge linking Linz with its suburb. The bridge, because it serves both as an illusory link between spatial layers and as a diagonal in the picture-plane, became a primary compositional device of the mature landscape. Later on in his career, when he was decidedly more interested in making good pictures than veracious reports, Huber would never let the principle of optical fidelity spoil the effect of such a device.

157 Wolf Huber, Bridge at the City Wall, 1505, pen on red-tinted paper, 19.9 × 26.5. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

|

158 Wolf Huber, View of Urfahr, c. 1510, pen on paper, 13.3 × 14.8. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. |

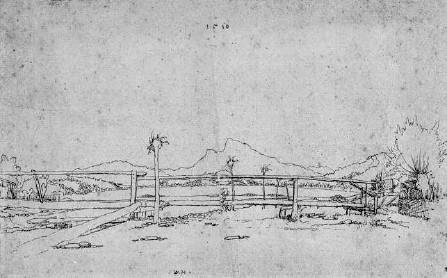

For his extraordinary View of the Mondsee, monogrammed and dated 1510, Huber took up a stance close to the surface of the earth and set out to describe everything adjacent to the horizon in pure contours (illus. 159).57 He drastically foreshortened the intervening terrain. This is the formula of the skyline, and yet it is not a city that is described, but a lake and a mountain, the Mondsee and the Schafsberg in the Salzkammergut, about fifty miles south of Passau. The View of the Mondsee is one of the most beautiful of all German drawings, and unamenable to photographic reproduction. The pen line trembles while it traces mountain profiles, tiny loops of trees on the far bank, the mossy rails of the footbridge, the wattle fence at the right. One thinks of it as the tense, idolatrous pen of the ‘close looker’, the pen of obsessive scrutiny and patience. In fact, its closest relative is the pen line of some early drawings by Altdorfer on plain white paper, including the manuscript illustrations to Grünpeck’s Historia, as well as some pure fictions – the Lady on Horseback in Berlin, the Couple in a Cornfield in Basel, the Venus and Cupid in Berlin (illus. 160); the last two are dated 1508.58 These palaeographic analogies, as well as Huber’s work on coloured ground from as early as 1505, suggest that contact between the two may have preceded Altdorfer’s Danube journey of 1511.59 Altdorfer’s independent drawings could easily have floated down-river to Passau. Altdorfer turned to plain pen on white paper particularly when he was preparing a print. The Historia illustrations were supposed to become woodcuts. The Venus and Cupid was in fact made into an engraving.60 But Huber’s Mondsee lives completely in the present. The threadlike lines pull the beholder in close behind the draughtsman, compelling the beholder to duplicate the original, reverential act of looking. Depth in this landscape is created by almost imperceptible modulations in the thickness and tone of line; even good photographs flatten it out. The sheet points neither backward to a natural object, nor forward to the closure and plenitude of a fully public work.

The views of the Mondsee and of Urfahr are thus still topographies. And yet at the same time they are already independent landscapes. They have begun to emancipate themselves not from subject-matter but from topography. The foreground intrusions contest the clarity of presentation and the plenitude of information promised by the topographical report. Those intrusions are themselves the yields of the most exacting and scrupulous optical honesty. Pure mimesis here defeats itself; it is the victim of what might be called perspectival irony. The self-defeat of the low point of view runs parallel to the inversion of subject and setting in narrative. In this case, impertinent foreground objects and wide open sky compete with the proper object of the topographical drawing, namely, the natural and architectural landmarks. The town of Urfahr and its hills are wedged between sky, blank river and disembodied rooftops. The Mondsee is interrupted and obscured by a mere footbridge. A feeble pollard willow in the foreground, the closest approximation of a human figure in the drawing, becomes the unlikely protagonist. Setting threatens to humiliate the topographical fact, to reduce it once more to the status of setting. The topographical fact starts to look dead in comparison to a springy tree, a mountain face, an expanding sky. What makes the View of the Mondsee a picture is finally its unremitting sensitivity to its own edges. The drawing can be parsed like a classical period, as if it were the end product of a dozen draughts. Huber knew exactly where to stop describing. He drops three clusters of rocks into the foreground, then leaves the bottom layer blank to balance the sky. The foremost tree, last in a parade driving obliquely into distance, closes a gap in the mountain profile. The entire surface of the earth bulges slightly, bringing the landscape to a close at the left and right, and bending every log out of the horizontal or the vertical. For all the microscopic energy, the drawing has a structure.

159 Wolf Huber, View of the Mondsee, 1510, pen on paper, 12.7 × 20.6. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

160 Albrecht Altdorfer, Venus and Cupid, 1508, pen on paper, 9.7 × 6.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. |

|

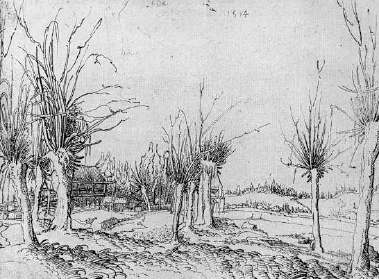

161 Wolf Huber, Willow Landscape, 1514, pen on paper, 15.3 × 20.8. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Huber’s pen-and-ink landscapes staked their appeal on the apparently serendipitous pictorial activity of trees, bridges and forest paths. Watermills and small farms are the ostensible subjects of the Mill with Footbridge (illus. 116) or the two Willow Landscapes, all in Budapest, the latter pair dated 1514 (illus. 161).61 But in the Willow Landscapes the trees themselves, grotesque fruits of human cultivation, take over the drawings. They loiter like actors without a script. When Huber’s landscapes become vertical in format, the line bends toward the fantastic. In the Castle Landscapes in Oxford and Berlin, from the early or mid-1510s, chimerical mountains and castles rise straight up out of the forest as if to answer the anthropomorphic willows (illus. 162).62 The pen line is even and self-possessed, released from its rivalry with the contours of the natural object. From this point on, most of Huber’s landscapes are fictional. Whereas prosaic attentiveness spreads outward in the plane, in Goethe’s terms, fantasy imagines objects mighty and steep. Once the formulas of fiction had been established, there was little piety for the facts of topography. After Urfahr, the Mondsee, and the view of the Harburg of 1513,63 only four or five of Huber’s landscapes depict identifiable places.64 In the vertical drawings, especially, the manipulations of foreground trees and the perverse perspectives on architectural elements begin to overlap with the new unstable or ‘folded’ compositions with figures. The Willow Landscape in Berlin (illus. 115) tentatively builds a space back into depth, then masks it with a screen of trees. In his vertical landscapes, Huber preserves the technique of the early topographies, but adopts the format, structure and mood of vertical narratives. Huber’s vertical landscapes are affiliated both with Altdorfer’s coloured-ground drawings and with his own narratives on plain white paper.65 Huber’s poetic vertical distortions of landscape and its conventional motifs exactly parallel Altdorfer’s ludic and satiric warping of subject-matter.

162 Wolf Huber, Castle Landscape, 1510s, pen on paper, 19.1 × 13. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

163 Hans Leu the younger, Landscape with Cliff, 1513, pen on paper, 22 × 15.8. Kunsthaus, Zurich.

|

164 Niklaus Manuel Deutsch, Mountainous Island, pen on paper, 26 × 19.8. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. |

Huber’s production rapidly began to proliferate in several directions at once, and he continued to monogram and date landscape drawings until a year before his death in 1553.66 The quantity of surviving drawings, the dates and the monograms, and above all the incidence of multiple copies indicate that Huber succeeded in establishing some kind of a market for independent landscape, comparable to and contemporaneous with the Venetian market for the landscape woodcuts and drawings of Titian and Domenico Campagnola. By the middle of the 1510s, Huber’s drawings were being copied by other hands. Yet despite the evident success of his landscape formula, few among Huber’s peers thought to follow him. Only the Swiss experimented with the fictional pen-and-ink landscape in vertical format. A landscape by Hans Leu the younger in Zurich is monogrammed and dated 1513 (illus. 163).67 The drawing starts as a cliff, like the study-turned-picture by Leu’s countryman Urs Graf (illus. 71). But the lanky, moody tree at the right closes off the picture surface. In the 1510s Niklaus Manuel Deutsch drew a Mountainous Island in the shape of a grotesque head (illus. 164).68 As independent-minded as the swashbuckling Graf, Manuel simply let his contours flow until the rock melted. It is a fanatically vertical drawing, the antithesis of a panorama: for here the earth itself has lost contact with the earth. The biographical contacts between Huber and the Swiss are difficult to establish. Koepplin has suggested, indeed, that the provocation to draw landscape may have come from Altdorfer rather than Huber, perhaps by way of Nuremberg, where Leu seems to have spent some time in the early 1510s.69

Altdorfer never drifted as far from topography as the Swiss did. His View of Sarmingstein70 and the Willow Landscape,71 like Huber’s early landscapes, are fundamentally views of places (illus. 165 and 166). Altdorfer drew them from the banks of the Danube in 1511. That journey took him at least as far as Castle Aggstein in the Wachau, which is attested in the background of his woodcut St George of 1511,72 and possibly as far as Vienna. The works are the only documents of the trip.73

165 Albrecht Altdorfer, View of Sarmingstein, 1511, pen on paper, 14.8 × 20.8. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

166 Albrecht Altdorfer, Willow Landscape, c. 1511, pen on paper, 14.1 × 19.7. Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna.

There is no proof that the two pen drawings were done from life. But there rarely is proof. One expects from a life drawing a certain irregularity or intractability of detail. The random detail – again the effect of the real – convinces the beholder that the draughtsman has recorded precisely what he saw, without excessive regard for pattern or decorum. Even this calculation will not guarantee that a drawing was physically executed out of doors. Altdorfer’s drawings could conceivably be Reinzeichnungen or fair copies worked up, indoors, from more informal sketches.74 But this is not the impression the drawings make. The plein-air encounter leaves a trace, the imprint of the draughtsman’s haste before the multiplicity of phenomena, or of his despair in the face of a problem beyond his technical means, or of his satisfaction over an ingenious solution to a problem. The dramatic compression of the moments of witnessing and of bearing witness is accompanied by a certain sense of adventure – especially during this infancy of life-drawing. The draughtsman confronted with the full complexity of the earth’s surface quickly discovers the limit of his descriptive powers. The trace of the out-of-doors, the mark that the draughtsman leaves on topography, is what happens when that limit is breached.

It is often very hard to say whether Huber’s drawings were done directly from life or worked up from sketches, or whether indeed they were not complete inventions. The same is true of Altdorfer’s Willow Landscape, and would be true of Sarmingstein had Meder not identified the place. However, these drawings bear all the marks of the dramatic encounter with the natural datum. They employ the formulas of plein-air drawing: horizontal format, low point of view, arbitrary intrusions of banal objects into the field of vision, hurried, unintelligible, or even excessively reverent line. But at the same time they are already fictions. For these drawings are all highly composed, alert to two-dimensional pattern and the edges of the picture-field; they are stylish, finished, and often signed or dated.

Life-drawing in this period is the aberration. The old model-book landscapes, the workshop templates and paradigms, were all fictions. So were Huber’s and Altdorfer’s drawings. The only difference was that the new fictions referred formally and structurally to an original outdoor encounter, even if that encounter never actually happened. The trace of the life-drawing is absorbed into the fiction. These are highly packaged topographies.

This packaging in the View of Sarmingstein takes the form of both vertical exaggeration and a rhetorical overburdening of the pen line. Both these themes were salient in the coloured-ground drawings. The continuity of Sarmingstein with Altdorfer’s other drawings resides in hyperbole and in the preenings of the pen. Indeed, the attribution is founded on this continuity. (At the same time, the date is so obviously written by Altdorfer that it almost suffices as proof; it is of no importance that its ink is slightly browner than the rest of the drawing.) The method of drawing mountains by tracing dentate outlines, shading them with tight rows of single strokes, and finally coating them with trees made with impatient elliptical loops is abundantly familiar from Altdorfer’s drawings, for example the backdrop of the St Christopher on green ground in Vienna (illus. 139).75 The mountains in this drawing stretch and overcome the scored plane of the water, as if in comical geological collusion with the gravitational pull which tumbles the saint. The View of Sarmingstein is a denser and more disciplined drawing than any of the coloured-ground drawings, more compulsively intent upon its object, obedient to a more inflexible genius. The outlines of the mountains are crisp and attenuated; the rows of shading strokes are so tightly ranged that they produce an almost metallic sheen; the trees are less flippant, indeed some are even shaded horizontally. (The pen line of the View of Sarmingstein is actually finer and less bold than it appears in reproductions.) One is inclined at first to explain this density as the consequence of the topographer’s earnestness and attentiveness. But in fact the line of Sarmingstein is the same tense and fragile line of the other early, entirely fictional, drawings on plain white paper. It is, again, the line of the Venus and Cupid (illus. 160), the Couple, of some of the Historia illustrations; the line that Huber extended into his View of the Mondsee. It is a line that shrinks from the calligraphic and nevertheless parades as an artefact, as the only vaguely reliable trail of a highly selfconscious hand. The frequency of its tremors and the tight radii of its curves should not be mistaken for any special reverence for the object. What, then, is the distinction between the drawings on plain paper and those on coloured ground, if it is not subject-matter or tone? It may only be the medium. Plain paper normally put up a slightly stiffer resistance to the flow of the quill pen. The only coloured-ground drawing to share this line was Altdorfer’s early Samson and Delilah, dated 1506 (illus. 208).

The View of Sarmingstein focuses on a fortified church at a bend of the Danube. The place was identified by Meder, with the help of Matthaeus Merian’s Topographia provinciarum austriacarum (1649), and local historians, as Sarmingstein, just below Grein, about forty miles downstream from Linz. Altdorfer described both steep banks of the river, the slouched terraces of fir and rooftop and the stone wall, the cylindrical gate-tower already in ruins and almost lost among the brush, the wooden bridge over the mouth of a mountain tributary, and the hedged road at the river’s edge.76 The church and its outlying structures cover the centre of a great perspectival X, a diagonal quartering of the drawing surface. Sarmingstein is very much the functional, and no doubt the literal, starting-point of the drawing. The church itself, whose roofs and walls and windows are accounted for with some degree of precision, benefits from a kind of attentiveness lacking in the remainder of the drawing. At the same time, the church is a terminus, the embattled target of centripetal forces generated by the taut coils and chords of ink. These forces descend on Sarmingstein along the arms of the perspectival X, vibrating with concerted tension.

The modelling strokes are pulled out of the vertical; the mountain at the extreme upper-right is bent into a quarter-circle; soft and meaningless arcs are described in the sky. This force in the drawing, which seems to disdain objectivity, is the compulsion to organize the topographical data into a composition. The pictorial organization of the View of Sarmingstein is manifested in the coordination of the topographical object – the church and its outbuildings – with its setting. That coordination is achieved by means of a two-dimensional figure, that X which exists only on paper and yet does not quite negate the empirical world. This chiasmus serves as an internal frame, a stretcher, for the entire picture, independent of the topographical object, and at the same time it preserves the primacy of that object. The X is the equilibrium of mutually indifferent forces: the more or less systematic projection of a three-dimensional continuum onto a plane; the artist’s consciousness of pattern in that plane and his constant awareness of edge and corner; the tendency to exaggerate vertically; the energy of the stylish pen line. The vertical shading lines in the mountains at the left lean first in one direction and then the other (they shift not so much from left to right as toward and away from the focal buildings). The hostile bluff behind the church leans hard to the left and appears almost to twist back upon itself. The rotation at the upper-right is both a surrender to the pull of the centre and a shrinking from the confines of the corner. The fortification itself has fallen back upon itself, settling back on its haunches as if better to absorb the shock of the converging river-banks. At the same time, the triangles of river-bank are expected to generate an illusion of depth, of spatial recession. This is one of the effects of the loose, calligraphic modelling lines in the upper-right of the picture. They are less densely packed than their counterparts in the distant mountains, as if they somehow represented real lines in the mountain face and their spacing were simply a function of their proximity to the picture plane. There is in fact no reason why abstract modelling lines should change their form as a function of apparent distance. The effect is disconcerting, for one can imagine that the distant modelling lines would also expand into an equivalent looseness and springiness if they could be seen at closer range.

The Willow Landscape is an even more demonstrative drawing (illus. 166). The two trees of the foreground and the meaningless knoll of the foreground, the very ground the draughtsman sits on, are the progeny of the same compulsive literalism that afflicted Huber the topographer. The sheet is undated, but Meder associated it closely, and not unreasonably, with Sarmingstein, on the basis of the buildings visible in the middle-ground. Nevertheless, the trees obstruct the view to such an extent that it is impossible to be sure. The topographical object has been overwhelmed by the composition. The triangular narrowing of the valley from left to right is perfectly explicable in its own right. But when the spatial recession represented by that planar convergence (i.e., from front left to right rear) is crossed at right-angles, impertinently, by the vector of the crippled willow (from front right to left rear), then suddenly the relationship between surface pattern and spatial illusion is perceived as a relationship of tension. Instead of seeing a place, the beholder sees overlapping triangles and intersecting planes. The slope of the mountain at the left, even with its crooked terraces and its shifting modelling lines, becomes a single plane, and the dark oblique face of the more distant mountains still another plane, each slightly out of alignment with the planar sweep of the entire valley. The curve of the second willow, amazingly, becomes an object of interest. This sort of double meditation (draughtsman’s and beholder’s) on how space is filled only takes place on two-dimensional surfaces. Space does not become interesting until it is empirically annihilated, flattened on a picture plane.

The most headstrong fictional device in the Willow Landscape, the most conspicuous discontinuity between observation and execution, is the pen line. The monogrammed tablet suspended from the lesser tree is not autograph, but rather the well-informed, perspicacious, or fortuitous gloss of a later owner. For the attribution cannot be doubted. In effect, the drawing is signed: the scrub at the lower edge, at the foot of the bent tree, has degenerated into a kind of indecipherable organic scribble, calligraphic, unrepeatable, no longer of the represented world. This is not merely a broader spacing of the modelling network at closer range, as in Sarmingstein. In passages like this, the pen temporarily uncouples from mimetic responsibility. Such passages serve as signatures throughout Altdorfer’s work, for example in the foregrounds of the London Wild Man (illus. 106), the Weimar Couple, the Beheading of St Catherine in the Akademie in Vienna, or some of the Historia illustrations.77 The grassy flourish recalls Dürer’s swift landscape sketch (illus. 35), where half-automatic scratchings assumed the form of the outdoor object. Such passages are naturalized versions of the scribe’s calligraphic flourish, or the unrepeatable paraph of the medieval clerk (see p. 74). In Altdorfer’s drawn View of Schloss Wörth a calligraphic flourish in the sky may actually replace the monogram (illus. 187). Altdorfer drew the same mark, with a brush, before and after his monogram in the Susanna and the Elders panel, on the tree at the lower left (illus. 54). Oettinger thought he saw A and A intertwined in the flourish, and wondered whether Altdorfer was experimenting with a new signature. Erhard Altdorfer, finally, on a woodcut title-page in the Lübeck Bible of 1531–4, wedged his own monogram among the loops of just such a flourish.78

Signatures fulfil their purpose by being inimitable. What makes the scribbled grass in the foreground of the Willow Landscape inimitable? It is not absolutely random, for like any signature it is grounded in a representational code, in this case what might be called the orthography of vegetation. Individual curves and flourishes may respect an ornamental logic, by tapering or diverging according to some abstract or geometrical principle. And yet the entire cluster of pen marks gives an impression of randomness. The individual line, on close examination, represents nothing. The lines are juxtaposed meaninglessly and adventitiously. This crypto-signature cannot be reduced to any single rule or proposition.

|

167 Albrecht Altdorfer, Saint, c. 1517–18, pen on paper, 11.1 × 9.8. University Library, Erlangen. |

The random line, then, is fundamentally an unpredictable and unrepeatable line. The effective guarantor of these qualities is the speed of the draughtsman’s hand. The hand moves faster than the mind; the pen stroke cannot be broken down into a series of component decisions. The word ‘random’, indeed, derives from the Old French randir, meaning ‘to run’. The haphazard happens quickly; it is the movement of a horse running loose, out of control. The horse makes its decisions on the run, shifting direction instantaneously, although not necessarily irrationally. This is the sort of impetuous movement Goethe was seeing when he made these notes about Dürer and his contemporaries: ‘They all have, more or less, this meticulousness [etwas Peinliches], in that when confronted with monstrous objects they either lose their freedom of action, or assert it, insofar as their spirit is great and has grown toward those objects.’ Goethe conveys precisely the precariousness of a fastidious description. ‘Thus in all their observations of nature, even in the imitation of it, they pass over into the adventurous [ins Abenteuerliche], indeed become mannered.’79

168 Albrecht Dürer, St Anthony, 1519, engraving, 9.6 × 14.3. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The adventurous draughtsman exploits the quill pen. The quill leaves a margin of ‘play’ or ‘give’ between hand and paper that permits great sensitivity but also great freedom, including the freedom to wander or err. The minute tremors of the quill-drawn line can register the contours of a leaf or the vagaries of a physiognomy. In the same instant, the quill can slide just out of control, slightly beyond the radius of intention. The antithesis of this equilibrium between singularity and accuracy is the earthy, emotional chalk stroke of Grünewald. Although he was the only outstanding figure of his generation not to stake his career on graphic work, Grünewald was nevertheless a superlative draughtsman. His chalk is attentive exclusively to surface, to the muted broadcast of light on surface. This is not to say that line is absent; on the contrary, his quavering drapery hems and spiralling rows of pleats are among the comeliest linear effects of the High Renaissance. But these contours are by-products of the reverence for surface, and have nothing to do with the undisciplined play of the drawing instrument.

Altdorfer’s two black-and-white landscapes hover just on either side of this ideal equilibrium between sensitivity and freedom. The quill of Sarmingstein is tightly gripped and registers contours like the needle of a scientific instrument, in a fuzzy vibrato. The pen passes over into the adventurous only in the interiors of the mountains, as a diversion from the monotony of modelling, or in the sky, where there are no contours at all. The Willow Landscape, by contrast, begins to surrender to the momentum of the random. The bent tree is itself a calligraphic singularity writ large. Here Altdorfer takes the liberty of haste. His distant forests are scribbles. His ad hoc procedure leads him into culs-de-sac, like the row of trees that overlaps the modelling strokes in the cliff behind, just to the left of the base of the bent tree, or the icy mountain profiles at the upper-left that failed to meet and were instead, expediently, joined by a diffident and unconvincing vertical drop. The corollary of the freedom to bend lines is the freedom to omit lines. The wide blankness of the mountains would be inconceivable in Sarmingstein, where an obsession with transcription and a horror vacui combined forces to fill the sheet to its edges.

The adventurous line eventually abolishes the existential distinction between one object and the next. Once line is read as a trace of a manual gesture, its reference to an empirical signified is weakened. The trace is present and persuasive, whereas one absent signified is as good as another. Once subjected to such treatment, even terrain can spill upward over the horizon and flood the sky. This happened in Altdorfer’s Battle of Alexander, but also in the furrowed, pulsating skies of Huber’s drawings (illus. 200).80 Style converts sky into upside-down landscape. The human figure is equally vulnerable. Wölfflin first called attention to the visual rhyme between the hunched figure of St Anthony and the hill-town in the background of Dürer’s engraving of 1519 (illus. 168).81 Dürer petrifies his subject-matter. He means to evoke by this device the monumental, imperturbable gravity of the saint’s person. But the device also bleaches out the distinction between setting and subject. The power of the visual rhyme – the signifier – seduces the beholder into experiencing the engraving on another level; seeing prevails over knowing. The engraving becomes all setting, like a landscape.

Altdorfer made a man-mountain of his own in a fine-spun pen drawing of a saint in Erlangen (illus. 167).82 This is the exact opposite of a landscape with anthropomorphic trees or cliffs. A cliff becomes a person when its random contour all at once resolves into a meaningful profile. The silhouette of the human figure is so distinctive that when it emerges in a landscape it dispels randomness; meaning adheres to the profile. The loose or arbitrary landscape motif will all at once look overdetermined. The human figure that starts to look like a mountain, on the other hand, dissolves back into randomness. It is a human contour whose distinctively human lumps and excrescences have all collapsed inwards, toward the finitude of the monolith. Altdorfer’s pen then begins to create its own excrescences, as if reanimating the statue. The pen circles in upon itself, performing hundreds of licks and feints within the body. The halo is an obvious object to describe with a clean sweeping stroke; instead the line dances. Huber, meanwhile, in a portrait drawing of 1517, described a face with the very lines he ordinarily used to describe terrain. The face is modelled with curved rows of interior contours (illus. 169).83 The pen moves around the face and the garment as if it were still inside the Golgotha landscape (illus. 200). Once one has seen this face-landscape, it is hard to look back at Huber’s real landscapes in the same way.

169 Wolf Huber, Portrait of a Man, 1517, pen on paper, 14.4 × 11. Guildhall Library, Corporation of London. |

|

Such examples spell out an alternative to a theory of early landscape grounded in content or the absence of content. They question the very category ‘landscape’. Why study landscapes separately from other kinds of pictures? Why indeed, if the real story being told is the genesis of the historical category ‘work of art’? When an artefact is experienced as a presence rather than as the sign of an absent object, distinctions of content fade in importance. This is no anachronism. The power of the phenomenal image to disrupt its own reading shadowed the entire history of Christian art. Fear of this disruption lies at the source of the iconoclastic impulse. Over the course of the sixteenth century this experience was domesticated and institutionalized in aesthetic doctrine, in prints, in collecting, in the entire secular culture of images. This culture was of course not so indifferent to content. It actually protected the landscape. The empty landscape became the emblem of the new legitimacy of the phenomenon, and of its new authority over subject-matter. Landscape as a work of art, curiously, had no trouble absorbing the re-introduction of story and time. Landscape would survive the loss of its strict independence from subject-matter. For from this point on, the genre ‘landscape’ stood for the institutional independence of the framed image, any framed image.