5

The Published Landscape

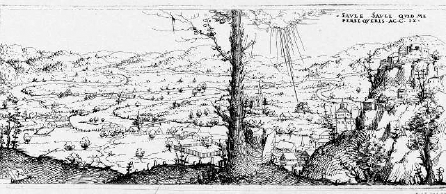

One of the cornerstones of the new secular culture of pictures was the print. Altdorfer trumped Huber when he discovered a way to reproduce his landscape drawings mechanically. Altdorfer made nine landscape etchings, seven of which are horizontal in format, the other two vertical (illus. 171–9).1 All are monogrammed, none are dated. A tenth etching, horizontal in format, is monogrammed by Altdorfer’s brother Erhard (illus. 180).2 These etchings had low print runs, a limited direct audience, and almost certainly no international audience. They were revolutionary landscapes, but they ignited no revolution. German printmakers were imitating Altdorfer’s invention as early as the 1530s; most important were the landscape etchings of Augustin Hirschvogel and Hanns Lautensack of the 1540s and 1550s. Any influence that Altdorfer’s landscapes exerted was indirect, through the agency of these epigones. In Antwerp in the 1550s and 1560s, notably, the cunning printmaker and publisher Hieronymus Cock published entire albums of landscape prints, capitalizing on Patenir and the Flemish world-landscape. Cock hired an artist recently returned from Italy, Pieter Bruegel, to design his landscapes. Titian and some of his followers, meanwhile, had been publishing landscape woodcuts in Venice since the late 1520s. The Venetian prints had their own independent impact on Cock’s production. Landscape rapidly became one of the major categories of collectable prints. This landscape was no longer green. Greenness had been the primary epithet of the lost outdoors; even Erasmus had seen the wisdom of God manifested in ‘greening’ nature (naturae vernantis).3 But humanists reflexively mistrusted painted colour. Erasmus, when he eulogized Dürer’s black lines, spoke for the most rigorous and suspicious of them. The print stripped the landscape down to its skeleton. It detached the representation of landscape from the putative psychological function of real landscape. The black-and-white landscape thus opened a gap – or revealed a gap – between the critical amateur and the beholder who sought a memory or a promise of recreation in a surrogate nature.

Altdorfer’s public

Who was the first audience for Altdorfer’s landscapes? By the early 1520s, the years of the etchings, Altdorfer was firmly established in Regensburg. Since 1517 he had been a member of the Outer Council; in 1518 he bought a second house (which he sold in 1522). In 1519 he played a central role in the management of the sensational local cult, the pilgrimage to the Schöne Maria. From 1520 to 1525 he directed the office of the Hansgrafenamt, which oversaw the city’s craftsmen. In 1525 he was appointed director of a charitable institution in Ingolstadt. By 1520 or so, after he had completed his great altarpiece at St Florian and his various projects for the Emperor, Altdorfer may well have dissolved his workshop – just as Dürer did at a comparable point in his career – and retreated to more manageable and private projects.

Hans Tietze once said that Altdorfer painted for sophisticated amateurs, and that the first among them was the painter himself.4 Artists were in fact the earliest collectors of drawings, and not merely as models or practical examples. Dürer owned and inscribed pen drawings by Schongauer. Samuel von Quiccheberg, the Antwerp physician who organized the Wittelsbach art collections along systematic lines, reported in 1565 that Hans Burgkmair had collected drawings.5 One has to reckon with the possibility that Altdorfer’s most eccentric pictures stayed in his shop, or migrated no further than another artist’s shop.

Only one landscape by Altdorfer can be linked even tentatively with a historical person: the watercoloured drawing, dated 1524, of Schloss Wörth on the Danube, one of the residences of the Regensburg Bishop-Administrator Johann III von der Pfalz (illus. 187). Doubtless Altdorfer had all the contact he wanted with Johann, who held his office from 1507 until his death in 1538, and whose career in Regensburg thus overlapped almost to the year with the painter’s. Old portraits of Johann, like the one by Hans Wertinger reproduced here (illus. 170), used to be attributed to Altdorfer. Altdorfer did make portraits – a pair survive – and may well have made one of the Bishop-Administrator.6 Johann probably commissioned the Prayer Book of 1508 now in Berlin, which was executed by an artist close to Altdorfer. But there is no reason to believe that Johann took any special interest in landscapes and other portable pictures. His tastes ran, apparently, to more conspicuous luxuries. In 1535 Altdorfer painted an ingeniously prurient suite of frescoes in the baths of the episcopal residence in Regensburg. The painted architecture appears to emulate a contemporary addition to the Residenz in Trent – the best evidence yet that Altdorfer visited Italy.7

170 Hans Wertinger, Portrait of Johann III von der Pfalz, 1520s, oil on panel, 70 × 47.5. Bayerische Staatsgemälde-sammlung, Munich. |

|

More important for the development of the first independent landscapes were probably the urban circles centred on humanist poets and antiquaries: the friends, acolytes, patrons and publishers surrounding men such as Conrad Celtis, Konrad Peutinger, Johann Cuspinian and Willibald Pirckheimer. Dürer, the son of a goldsmith, penetrated to the core of such a circle. Although many of the urban humanists had studied in Italy – at Padua or Bologna – they did not necessarily maintain academic ties. Celtis and Cuspinian held university posts, but Pirckheimer, a thorough patrician, practiced diplomacy and war alongside his philological pursuits. Celtis shaped several such circles into ‘sodalities’, German versions of the Italian neo-Platonic academies, which sponsored publications and devised fantastic, symbolic political ‘programmes’.8 The pattern held in Germany for no more than a generation, until the Reformation and the attendant crisis of the Holy Roman Empire began absorbing attention and energy.

171 Albrecht Altdorfer, Small Fir, c. 1521–2, etching with watercolour, 15.5 × 11.5. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The humanist societies flourished especially in the wealthy Imperial cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg and Strasbourg, which were unburdened by local potentates maintaining expensive courts. Elite culture in Bavaria, for example, was dominated – indeed somewhat stifled – by the Wittelsbach courts at Munich and Landshut.9 The only major southern German painter to join the household of a prince was Cranach in Saxony. Martin Warnke has argued that Renaissance courts gave artists unprecedented freedom and thus prepared them for modern self-reliance. The humanists hovering around the courts provided a conduit to the open market, and they began to surround art with critical writing and conversation.10 Altdorfer’s Regensburg, saddled with an unlettered Bishop-Administrator, offered nothing of the sort. But many of the best artists in southern Germany did enjoy the best of both worlds: they made forays into court service, but maintained residences, and their independence, in the cities. Wolf Huber in Passau, for example, at one point Altdorfer’s virtual colleague, eventually found an audience among the humanists at the court of Bishop Wolfgang von Salm in Passau.11 This flexibility was possible because urban painters’ guilds in this period remained weak. Of course the guilds were weak precisely because the outstanding painters were too wilful and refused to cooperate. Indeed, in Nuremberg there was no guild at all until 1596.12

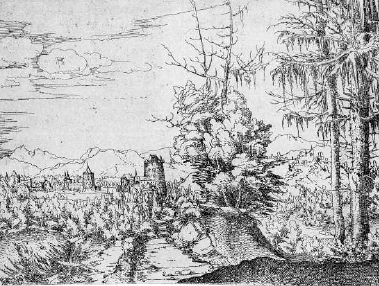

172 Albrecht Altdorfer, City on a Coast, c. 1521–2, etching with watercolour, 11.5 × 15.5. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

173 Albrecht Altdorfer, Large Fir, c. 1521–2, etching with watercolour, 22.5 × 17. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

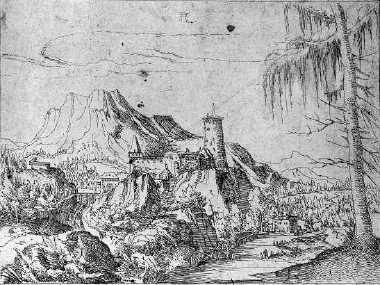

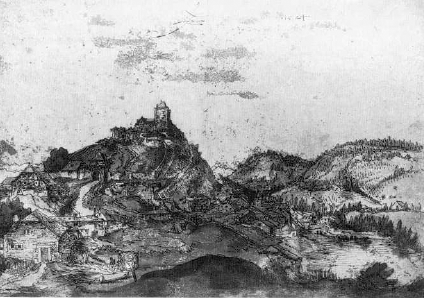

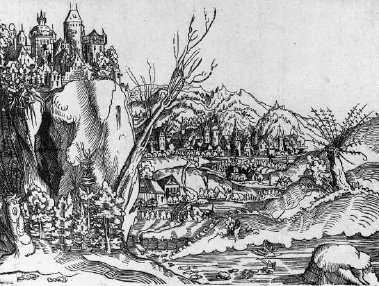

174 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Large Castle, c. 1521–2, etching, 10.8 × 14.9. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

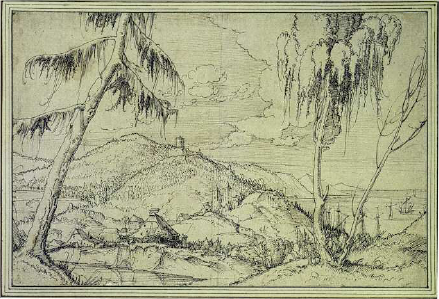

175 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Fir and Willows, c. 1521–2, etching, 11.5 × 15.5. City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth, Cottonian Collection.

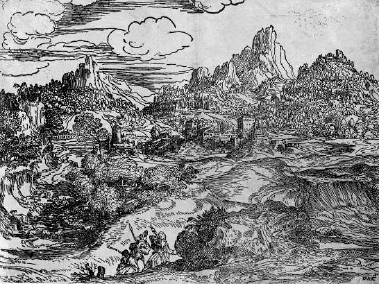

176 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Two Firs, c. 1521–2, etching, 11 × 15.5. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

177 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Double Fir, c. 1521–2, etching, 11 × 16. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

All the earliest collectors of small secular panels and prints must have had experience of northern Italian engravings. German antiquaries were decidedly literary-minded. Their curiosity about classical artefacts ran to coins, medals, inscriptions, maps. Deciphering iconography was a ‘readerly’ exercise, just as it is for modern art historians. Konrad Peutinger in Augsburg, for example, who was Maximilian’s iconographical adviser, and who designed hieroglyphs and the programme of the Triumphal Arch, betrays in his writings little real interest in pictures. The real public for the new secular images must surely have held opinions on contemporary art. They had to know something about the ordinary devotional image, and about the functions it had been expected to perform; they must also have had some notion, garnered from travel or from conversations with travelled artists, of the recent history of German and Flemish painting, and also, perhaps, a feel for the best engravings or manuscript illumination. They had to be attentive to medium and technique, and be capable of isolating and judging pictorial devices and strategies. This was the sort of audience that was looking at Dürer’s early engravings, Altdorfer’s engravings that imitated nielli and his coloured-ground drawings, Baldung’s esoteric and erotic painted panels, and the wood reliefs of Hans Leinberger or the Master I.P. Some must have begun collecting systematically – seeking out an impression of every print by Dürer, for example – although there is no hard evidence of systematic collecting at this date. The oldest print and drawing cabinets were assembled by the heirs to artists’ workshops. Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol compiled his massive collection of Netherlandish and German prints only at the end of the sixteenth century.13 The oldest collection still intact today belonged to Hartmann Schedel, the author of the Nuremberg Chronicle, dean of Nuremberg humanists from the 1480s, and close friend of Pirckheimer’s father. Schedel, who died in 1514, used to paste woodcuts and engravings, and even some drawings, into his books.14 There must have been a transitional stage, now vanished and thus untraceable, between Schedel’s method of preservation and the proper albums of the later sixteenth century: prints and drawings kept loose in portfolios and cabinets, for example. Thus one imagines the patrons and friends of Dürer and Altdorfer putting down the first layer of a recognizably modern, lay culture of collecting and connoisseurship.

178 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Cliff, c. 1521–2, etching, 11.5 × 15.5. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. |

|

|

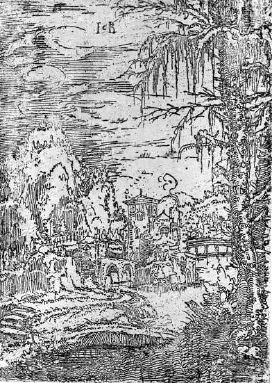

179 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Watermill, c. 1521–2, etching, 17.6 × 23.6. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund. |

180 Erhard Altdorfer, Landscape with Fir, c. 1521–2, etching, 11.7 × 16.2. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund. |

|

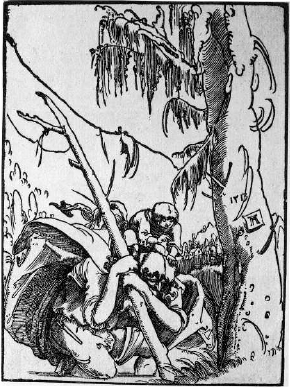

The new learned taste for small pictures frequently overlapped with a taste for sheer colour or texture, for example in Altdorfer’s St George panel. Humanism, in Fedja Anzelewsky’s phrase, generally tempered a prevailing asceticism.15 Humanist elitism and anti-ecclesiasticism was often translated into a contempt for everyday devotional images and their dreary subjects. After all, the old culture of secular imagery – above all the courtly and domestic murals and tapestries – had been more carnal and worldly than it was erudite. And after the Reformation, the fleshly impulses came to dominate again. Altdorfer’s late engravings and the prints of the so-called Little Masters – the Behams, Georg Pencz, Heinrich Aldegrever, all pupils of Dürer and followers of Altdorfer – were often frankly pornographic.16 Ostendorfer, Altdorfer’s pupil in Regensburg, was sympathetic to the Reformation. He made his way in the 1530s by painting profane and worldly Old Testament subjects: Lucretia, Judith, Bathsheba. Presumably he lived off a local market primed by Altdorfer.17

Nevertheless, the essence of the humanist culture of pictures was not its worldliness. What was really new was the critical attentiveness to the practical problems of picture-making. This implied a willingness on the part of beholders to work backwards from the picture to the artist, to reconstitute, in the imagination, the process of creation. The idea of style – the mark on the picture surface read as the trace of the artist’s hand – began with the artist’s desire to assert a public presence. But the success of this gesture depended on a public open to this presence. The humanist public was eager for manifestations of virtuosity. Perhaps they had read Pliny’s anecdotes about the Greek painters, or perhaps they were simply chauvinists looking for a counter-argument to the assumption of Italian cultural supremacy.

A humanist education was fundamentally rhetorical and philological. Literary humanists of Altdorfer’s and Dürer’s generation not only edited and published the corpus of classical lyric, but also composed huge quantities of neo-Latin verse. The subculture of humanist lyric provided models, historical and living, for the self-conscious and self-promoting artist. For the crucial formative decades, the last two before the Reformation, there is little evidence of a learned pictorial culture apart from the artefacts themselves. Judgements and hypotheses must have been honed in conversations. But they rarely made it onto paper. German humanists were, on the other hand, constantly apologizing for pagan literature. The poet Hermann von dem Busche, for example, complained of the anti-humanist sentiment among the faculty at the University of Cologne. ‘One criticizes the extravagances of mythological fables’, he wrote in 1518; ‘another rails against the seductions of language, and another criticizes certain supposedly improper aspects’.18 Would the humanists not have had to defend secular paintings against a comparable hostility? In conversation they must have developed a repertory of critical terms – like the terms increasingly clinging to poetic and rhetorical practice – well beyond the technical problems discussed in the workshop and the commercial formulas of altarpiece contracts. Some of the humanists must have seen the treatises and written dialogues on art circulating in northern Italian courts or in Florence. The German circles were, after all, the self-styled rivals of the humanist societies of Venice or Bologna.

All this surely made little sense to most artists. The various treatises which German artists published in the sixteenth century addressed methodical and technical problems, especially perspective.19 Even Dürer, who visited Venice twice, and probably Bologna as well, in some ways never escaped the mentality of the workshop. The critical revolution has to be inferred, for example from the documented enthusiasm of the most sophisticated historians and literary humanists for Schongauer, Dürer and Cranach. Pirckheimer’s remarkable friendship with Dürer, the intellectual energy he brought to bear on the artist’s project, is attested in letters, writings and works. The lost conversation even echoes in the artists’ own self-representations. Dürer portrayed himself in a humanist’s fur-lined robe, flanked by a Latin inscription. Burgkmair, mindful of Pliny’s anecdote about Apelles and Alexander, showed himself in a woodcut designing hieroglyphs for an attentive Emperor Maximilian. Ambitious artists found their own images in humanist discourse and in Antique texts as if in a mirror. But rarely did a humanist say anything in writing about pictures.

Altdorfer is actually the most interesting artist of the period who is not mentioned in a humanist text. Regensburg, although a free Imperial city like Nuremberg, was arid ground for literary culture. The city did not even have a printing-press until 1521. There was no visible society of humanists in Regensburg. The intellectual centre of the town was the Benedictine monastery of St Emmeram. Altdorfer painted the Two St Johns for St Emmeram, and possibly the Christ Taking Leave of His Mother as well (illus. 12, 13). Humanists often stopped in Regensburg to use the library: Hartmann Schedel in the 1480s and 1490s; the poet laureate Jacob Locher (Philomusus) in 1503; Johann Cuspinian. Conrad Celtis discovered the works of Hrosvitha of Gandersheim at St Emmeram in 1493. The historian Aventinus worked systematically through the library in 1517; he eventually settled in Regensburg in 1528 and died there in 1534.20 The monastery sponsored no particular school or intellectual tendency in this period, but it did house several notable personalities. The sub-prior and librarian Erasmus Daum (Australis) was intimate with both Celtis and the mathematician and Imperial historian Johann Stabius. The abbot of St Emmeran from 1493 to 1517, Erasmus Münzer, cultivated antiquarian scholarship and numismatism. It was presumably Münzer who commissioned Altdorfer’s Two St Johns, which was by no means a conventional devotional painting. The monk and chronicler Christophorus Hoffmann (Ostofrancus), an erudite opponent of Luther and an apologist for the anti-Semitic instigators of the Regensburg pilgrimage, wrote poems to his humanist friends.21 The Dominican abbey of St Blasius, Albertus Magnus’s base, also kept its library up to date with humanist editions of the Church Fathers and recent Italian historical writings.22

The Emperor had two men in Regensburg: Joseph Grünpeck, secretary, astrologer and composer of the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani, who founded a Latin school in 1505; and Stabius, who was given a house in Regensburg in 1512, presumably to supervise the work on the Triumphal Procession miniatures in Altdorfer’s shop. Some of the cathedral canons might have taken an interest in pictures: Johannes Tröster, a bibliophile with pagan and Stoic leanings, and Johannes Tolhopf, the friend who accompanied Celtis on his Druid expedition; both were dead, however, by Altdorfer’s time. Celtis himself was rector of the cathedral school in 1493. The Regensburg clerics doubtless had contacts with canons in Passau or Eichstätt, some of whom had university training or held professorships at Ingolstadt. Well-travelled Regensburg merchants were other possible clients.

Not a single contact between Altdorfer and any of these men is documented.23 Altdorfer did not leave any portraits comparable to the impressive and iconic image of the geographer, astronomer and historian Jakob Ziegler, painted by Huber in the late 1540s when Ziegler was sojourning at the episcopal court in Passau.24 There is, however, some evidence from his pictures that Altdorfer profited from contact with philologists and university men. Bernhard Saran infers from the Berlin Rest on the Flight of 1510, for example, that Altdorfer knew Virgil’s Messianic Eclogue and Ficino’s commentary on it (illus. 53).25

Of course, scholars, poets and artists were constantly on the road, and there is no need to seek Altdorfer’s contacts exclusively in Regensburg. Vienna was one intellectual centre of gravity, Nuremberg another. Celtis had formed a group around him when he arrived in Vienna in 1497, the ‘Sodalitas literaria Danubiana’, which included Cuspinian, Stabius, and the astronomer and antiquarian Johann Fuchsmagen. Cuspinian succeeded Celtis as leader of the society after his death in 1508. In 1501 Maximilian founded the ‘Collegium poetarum et mathematicorum’ at the University in Vienna and named Celtis and Stabius, and later Cuspinian, as professors. The neo-Platonist poet Vadian, editor of Pomponius Mela’s geography, was their student. This was the world that Cranach found in Vienna in the early years of the century, when he painted the portraits of Cuspinian and his wife Anna Putsch (illus. 37).26 Koepplin has suggested that Cranach was in Regensburg in 1504; this may have provided Altdorfer’s initial link to Vienna. The situation in Nuremberg is more familiar. Altdorfer had the attention and the patronage of the Emperor and his advisers, if Hans Mielke is right about the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani, even before 1510. This contact alone would have sufficed to make Altdorfer’s reputation in Nuremberg, although Dürer must have known his work, at least his engravings, even earlier. Ingolstadt, finally, forty miles upstream from Regensburg, a university town since 1472, was the prime magnet for humanists in Bavaria. Celtis, while teaching at Ingolstadt in 1491, founded the first of his sodalities, and that society was revived in 1516 under Aventinus.

This sort of circumstantial evidence is hardly a basis for a prosopography of Altdorfer’s patrons and public. It can be said, at least, that the circle of amateurs supporting his work did not need to be large. The best guess is that Altdorfer made most of his wider contacts early in his career, between 1506 and 1515. Thereafter he turned inwards and concentrated on local affairs and court commissions. In 1526 the Alsatian humanist Beatus Rhenanus left Altdorfer off his list of the outstanding German painters. Evidently there were enough local amateurs to sustain Altdorfer in Regensburg. The career of Michael Ostendorfer, his pupil, also suggests this. But that local public remains completely anonymous to us.

‘Printed drawings’

Print technology in this period was amazingly quick to adapt to shifts in taste. Only a few years after the invention of the autonomous drawing on coloured ground, the German amateur could buy a mechanical imitation. The chiaroscuro woodcut, with its multiple blocks of black lines and broad areas of colour, was invented by Jost de Negker of Augsburg in 1508, although Cranach claimed precedence by backdating some of his own chiaroscuro woodcuts to 1506.27 The chiaroscuro woodcut reproduced many of the coloured-ground drawing’s most distinctive attributes: the negative effect of white lines on dark ground, and the way in which the white heightening strokes freely detached themselves from representational tasks. But since the woodcut could not deliver the direct trace of the artist, it made no pretence of competing with drawings. The chiaroscuro woodcut was no hoax or cheap substitute; the technical achievement was a component of its value. It stood alongside the drawing, just as the Italian chiaroscuro woodcut stood alongside the wash drawing with white heightening.28 Technology exempted the woodcut from the critical judgements that would ordinarily be brought to bear on a drawing. The movement of the pen on the blank woodblock and the final product were separated by a layer of technology. The empty surfaces on the block had to be chipped away – an almost mechanical process – and the block then had to be printed. Mechanical reproduction set the question of authenticity to one side. The amateur recognized the hand of Burgkmair or Cranach, for example, frozen, fixed by technology. But the print’s difference from the missing drawing – its blatantly mechanical mimicry of the trace – only enhanced the drawing’s prestige. The woodcut enshrined the drawing.

Altdorfer’s landscape etchings stood in an analogous relationship to landscape drawings. The etching was Altdorfer’s answer to Huber’s cottage industry of landscapes. The corpus of pen-and-ink landscape drawings around Huber is a thicket of overlapping copies and variations. The basic conditions of production are not yet fully understood. It is unclear, for example, whether Huber copied his own originals, whether he permitted pupils or subordinates to copy them, or whether most of the copies were done by later followers or imitators no longer under his supervision. Some copies are actually dated to the second half of the century, or even to the seventeenth century. But most date from Huber’s own lifetime. Huber made a big impression on other Bavarian and Austrian artists, and it is possible that all these landscape drawings were merely circulating from workshop to workshop. But no such corpus of copies after any other group of drawings by any other artist, including Dürer, survives. The monograms and dates make it likely that Huber was targeting a lay public. One even imagines him putting his apprentices to work producing landscape drawings, and so satisfying a market for landscapes that he himself had created with his initial experiments of the first decade of the century. Well over a hundred such drawings have survived, and there must once have been many more. But it is extremely difficult to discriminate between originals, Huber’s own copies, and the copies of pupils or followers without knowing how important it was to Huber himself to simulate or preserve the attributes of the original in those copies. Did he relax the linear tension in the copies, or blur the trace of the original act of creation, confident that wider circles of beholders would not regret the loss? Certainly he did not permit his monogram to be used indiscriminately. The dates refer to the date of the copy and not the date of the original, and this is consistent with the practice of those pupils or imitators who copied Altdorfer’s coloured-ground drawings in the 1510s.

|

181 Titian, Two Goats at the Foot of a Tree, c. 1530–5, chiaroscuro wood-cut, 49.3 × 21.7. British Museum, London. |

182 Domenico Campagnola, Landscape with Travellers, late 1530s, woodcut, 33 × 44.4, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

183 Albrecht Altdorfer, St Christopher, 1513, woodcut, 16.5 × 11.6. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection.

Since Giorgione, Venetian painters had also produced landscape drawings, or rather landscapes with pastoral or mythological accessories. Neither Giorgione nor Titian signed his drawings. This in itself is no proof that the drawings were meant to remain in the shop, as sources of ideas or even as direct models for paintings. These drawings are highly finished and were surely meant for the eye of the Venetian amateur. Perhaps they were given away as gifts. But Titian’s pupil Domenico Campagnola – a Venetian of German parentage – began in the late 1520s to produce numbers of landscape drawings. Some of these he did sign, but the rest are extremely uneven in quality, and it is unlikely that he drew them all himself. In the 1530s and 1540s Campagnola, with the assistance of copyists, was evidently producing landscapes for a market. In 1537 Marcantonio Michiel saw some ‘large landscapes in gouache on canvas and others in pen on paper’ by Domenico in the home of Doctor Marco in Padua.29 Domenico Campagnola certainly knew German work; perhaps he was aware of what Huber was doing.30

Some landscape drawings by Titian and Campagnola were made into woodcuts. Titian’s designs had been disseminated in woodcut since 1510 or 1511, but it is not clear that Titian drew any of his landscapes with the intention of publishing them. It looks as if the cutters were adapting their technique to his graphic manner rather than the other way around. The Two Goats at the Foot of a Tree, printed in both black and white and chiaroscuro versions, is a landscape motif without the landscape (illus. 181).31 It is impossible to imagine this woodcut as a painting or even as an engraving. Trunk and goats twist and spiral like an elaborate figure composition pressed flat in the front plane. The printed lines imitate a pen’s light touch, or short strokes. Some impressions were even printed in brown ink so as to better imitate pen lines. Like the German chiaroscuro woodcut, the Venetian woodcut immediately settled into coexistence with its putative original. Domenico Campagnola certainly did design his own landscape woodcuts. He made woodcuts even as he continued to draw landscapes. The Landscape with Travellers, from the late 1530s, derives its panoramic structure from Netherlandish landscape and its woodcut line from Dürer (illus. 182).32 Prints like this in turn exerted an impact on the mid-century Alpine landscapes of Bruegel.

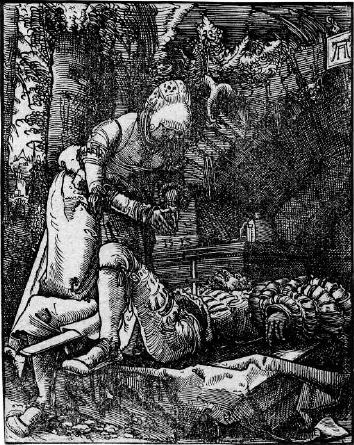

Woodcut was closely related to the pen drawing – much more so than engraving. A woodcut began with a drawing on a block. The wood between the drawn lines was then cut away with chisel and knife, normally by a professional cutter. Finally the lines left standing were inked and printed, exactly as in letterpress technique. The lines of an engraved print, by contrast, were ploughed directly into a soft copper plate. They were produced not with the light touch of hand and pen, but with a firmly gripped engraving tool, or burin. The grooves produced by the burin were then filled with ink. The lines of an engraving hardly resembled drawn lines at all. Some engravings, to be sure, tried to imitate some aspects of drawing. The dry-points of the Housebook Master, for example, with their burr of iron filings clinging to either side of the engraved line, simulated the coarse warmth of the artist’s own pen stroke. The stippled engravings of Giulio Campagnola, Domenico’s adoptive father, imitated the smoky strokes of chalk. Altdorfer, like Dürer, made both woodcuts and engravings. In one woodcut, the St Christopher of 1513, he particularly strove for the look of a loosely handled pen line (illus. 183).33 The long, isolated string of the mountain profile and the free-floating loops of foliage along the tree-trunk are citations from Altdorfer’s drawings; they are monstrosities in a woodcut.

Instead of competing with Huber by copying his own pen-and-ink landscape designs in quantity, Altdorfer had them printed. This time he passed over woodcut and turned to the absolutely novel technique of iron etching. Etching is closest of all to pen drawing. The design is scratched directly into a layer of wax spread on an iron plate. When the plate is submerged in acid, only those areas of the plate no longer protected by wax are eaten away. After the wax is scraped away, the grooves and marks left in the plate are filled with ink. Because the design is drawn in wax, the print pulled from the etched plate registers the artist’s hand far more sensitively than an engraving does. Whereas the engraver pushes the burin with the palm of his hand, the etcher holds the needle like a pen, with his fingers. The scratches in the wax simulate the ductus of the finest drawn lines. Vasari, in his life of Giovanni Battista Franco, described etchings as disegni stampati, or printed drawings.34

Vasari neglected to say who he thought invented the technique. The first dated etching is Urs Graf’s Woman Washing her Feet of 1513, although Daniel Hopfer of Augsburg, who was etching designs on iron armour in the 1490s, was probably the real pioneer.35 Marcantonio Raimondi may have been making etchings as early as 1515, but this cannot be proven. Dürer’s first dated etchings are the Man of Sorrows and the Agony in the Garden of 1515.36 The bizarre Landscape with Cannon of 1518, with Dürer’s self-portrait as a Turk, was one of the immediate models of Altdorfer’s landscape etchings (illus. 184).37 The foreground drops precipitously to a shelf of middle ground that is filled by a huge barn. A wayfarer mounts the next incline and approaches a Bildstock. The level landscape, depopulated but for a tiny figure on the road and an enormous horse in a field, reproduces the silverpoint drawing that Dürer made the previous year at Reuth near Bamberg (illus. 155). The only follower of Dürer to try his hand at etching was Sebald Beham. Although the aims of etching were at the start very different, in practice it seems to have been associated with engraving. Artists like Cranach, Baldung and Huber, who produced woodcuts but few engravings, left no etchings at all.38

The etching did not supplant either the engraving or the woodcut. Because the etched line neither swelled nor tapered, it lacked vigour and drama. The etched line often looked weak and spidery. Etching did not demand the same manual control and discipline that engraving did. Vasari, who mistrusted etching, did condescend to describe the process in his life of Marcantonio, and he praised, faintly, the etchings of Parmigianino as ‘cose piccole, che sono molto graziose’.39 The facility of the technique also invited unorthodox experiments. Dürer’s so-called Desperate Man (B.70), a jumble of dimly related figures and motifs, is little more than a printed sketch sheet. The medium seems to have served in part as a semi-private record of ideas, a kind of modernization of the workshop model-book. Etching in the first half of the sixteenth century remained a marginal technique, despite all its pungent successes in the hands of Parmigianino, Schiavone and the Fontainebleau masters.40

184 Albrecht Dürer, Landscape with Cannon, 1518, etching, 21.7 × 32.2. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

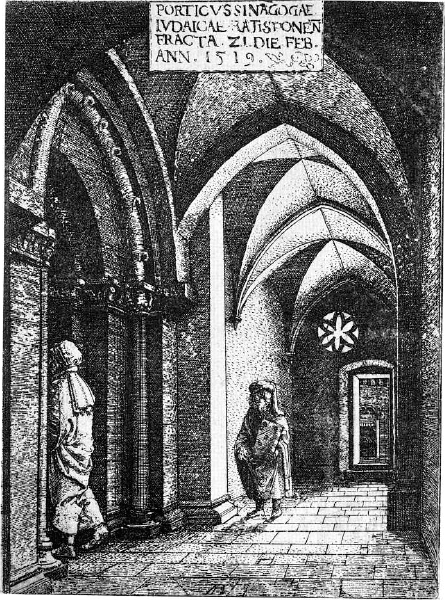

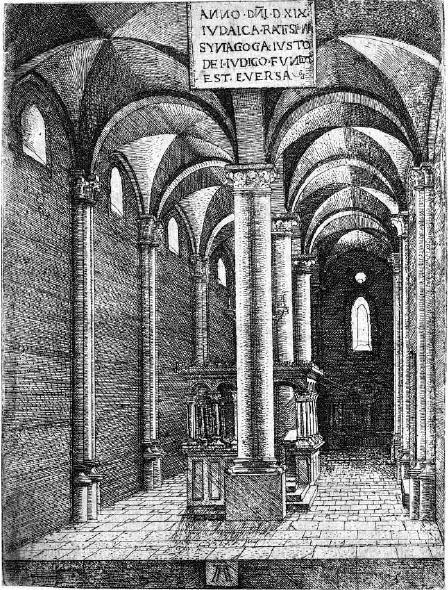

185 Albrecht Altdorfer, Regensburg Synagogue, 1519, etching, 16.4 × 11.7. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

Altdorfer’s only dated etchings are two views of the interior of the Regensburg synagogue (illus. 185, 186).41 The inscription on one of these extraordinary prints records the day of its destruction, 21 February 1519. The Jews of Regensburg, a community about 500-strong, had long been protected by the Emperor. Within weeks of Maximilian’s death in January 1519, the city turned against them. The Jews were given two hours to clear the synagogue and five days to gather their movable property and leave the city. During the demolition of the synagogue a workman was gravely injured. Two days later he reappeared at the worksite. This miracle was attributed to the Immaculate Virgin, who was supposedly the special target of the blasphemies of the Jews and thus the particular beneficiary of their expulsion. News of the miracle spread, and in this way Regensburg became the focus of the massive pilgrimage of the Schöne Maria.42

One of the etchings shows an elder standing in the porch of the synagogue holding a book, while another figure crosses the threshold. The inscription, on a panel superimposed on the scene, reads ‘Porch of the Jewish synagogue in Regensburg, demolished 21 February 1519’. The other etching shows the empty double-aisled interior. Fragments of a column and several arcades from the lectern or bima shown in this etching, incidentally, were excavated in 1940 and are on exhibit in the Stadtmuseum in Regensburg. What is not immediately clear is whether the prints are meant to represent the evacuation itself, or whether they only describe the building as it had once looked. On the one hand, contemporary sources report that the evacuation was accompanied by laments and dirges, and that the Jews chose to desecrate the building with their own hands. The scene must have been chaotic and emotional. Nothing of the kind is described in the prints. On the other hand, the inscriptions refer to the destruction. The most plausible purpose of such a publication was to record the event, not the features of the building. The etchings seem comparable in function to illustrated commemorative or polemical broad-sheets, like Michael Ostendorfer’s slightly later woodcut of the pilgrimage itself (illus. 134). However he might have chosen to edit the scene, Altdorfer almost certainly made the drawings for these etchings on the very day of the demolition. It can be presumed that few Gentiles had enjoyed access to the early thirteenth-century building before that day. This is most important. If it is true that the sketches had to be made on that particular day, then most viewers of the etchings would have known this. The etchings, in effect, published the drawings that Altdorfer made on the site. The medium itself, because it refers to drawing, spoke for the credibility of the reportage. The synagogue views demonstrate more clearly than any other piece of evidence that the early etching was meant to be read as the reproduction of a drawing.

It is not so easy to say what else the etchings are about. Altdorfer did tend to aestheticize empty space; one is reminded of the Munich Birth of the Virgin (illus. 52) or even the Church on a City Street drawing in Haarlem (illus. 56), not to mention the landscapes. But it would be imprudent to associate this emptiness with the pathos of expulsion and injustice. Nor, unfortunately, can we read irony in Altdorfer’s assertion, in the inscription on the view of the interior, that the synagogue was ‘completely demolished according to the righteous judgement of God’. Altdorfer was, after all, a member of the municipal delegation that delivered the expulsion order. This is not to say that everyone at the time would have applauded the city’s initiative. The Jews did not hesitate to challenge the expulsion. They addressed an appeal to Luther in the form of a psalm (in German, but in Hebrew script) even though the Reformer was not yet in any position to assist them. Their formal protest at the next Imperial Diet was at least partially acknowledged, and the city of Regensburg was penalized. According to an old story, Altdorfer used gravestones from the cemetery as pavement in his own house in Regensburg, whether to blaspheme them or preserve them we cannot say. A nineteenth-century author reported that abandoned headstones were used as pavement in his own parish in England.43 This implies that the practice is not necessarily disrespectful. Indeed, Altdorfer’s archaicizing version of the icon (illus. 121, 122) suggests that his interest in old local monuments was at least in part antiquarian.

The synagogue etchings are so accomplished that Altdorfer must have made other etchings before them. The only early survivor, none the less, is the feeble Lansquenet, a unicum in Berlin.44 Probably dating from the 1520s is a series of etchings of ornamental vessels and a pair of column parts, several of which served as models for contemporary goldsmiths.45

186 Albrecht Altdorfer, Regensburg Synagogue, 1519, etching, 17 × 12.5. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

One imagines the two Altdorfer brothers, Albrecht and Erhard, undertaking the landscape etching project together, during one of Erhard’s visits from the northern provinces. At the start of their careers they had worked together in Regensburg. Erhard’s engraving of the Lady with Coat of Arms is monogrammed and dated 1506.46 His engraving manner is a smooth and hollow version of his brother’s. Two more early engravings and a number of pen drawings on white paper have been attributed to Erhard and, despite slim justification, have adhered to his name.47 By 1512, possibly after a stint in Cranach’s shop, Erhard was working for Duke Heinrich of Mecklenburg in Schwerin, near the Baltic Sea. He remained based in north Germany as court painter and architect until his death in 1562. Erhard did return to Regensburg in 1538 to sell the house he had inherited from his brother. But he must have made other trips south before then.48

It is difficult to form an idea of Erhard’s career for the years when he was not in direct contact with his brother. The only certain works from the long Schwerin period are book illustrations, above all the woodcuts for Ludwig Dietz’s Low German Lutheran Bible, published in Lübeck between 1531 and 1534 (and thus actually preceding by six months the first complete Bible in Luther’s own High German). It is inconceivable that Erhard Altdorfer made an initial landscape etching all by himself in distant Schwerin. He must have learned the technique directly from his brother.

The two surviving drawings closest to the landscape etchings are the Coastal Landscape in the Albertina and the View of Schloss Wörth, dated 1524, formerly in Dresden but missing since the War. Both drawings measure several centimetres taller and wider than the largest of the etchings, and cannot be directly linked to them. The Dresden landscape, which is coloured with brown, blue, olive-green and red washes, is a topographical drawing (illus. 187).49 It describes a hilltop castle at Wörth on the Danube, a residence of Johann III von der Pfalz, Bishop-Administrator of Regensburg and one of Altdorfer’s patrons. Very likely Altdorfer presented the drawing to Johann on the completion of renovations to the castle in 1524. The drawing conscientiously and stiffly surveys the sweep of buildings at the base of the hill. In structure it is closest to the etching Landscape with Watermill (illus. 179); they even share a two-wheeled wagon, in the left and right foregrounds. But the Dresden landscape is a rhetorically chastened landscape. The slope of the castle hill is exaggerated, but the surrounding country has been protected from the depredations of Goethe’s poetic and ‘vertical’ imagination. The Dresden landscape has no bombastic foreground noise and it has no posturing tree; every one of the etchings has such a tree. The pen line never swings, leans, or lurches; the ductus is resolutely and soberly vertical.50

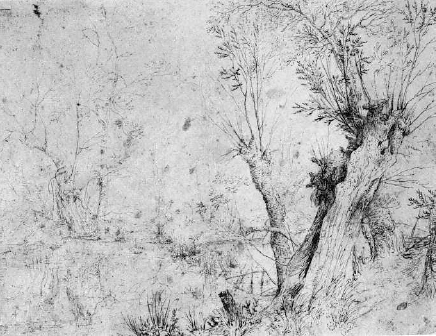

The Albertina Coastal Landscape is, curiously, the best-known and the most durable attribution to Erhard Altdorfer (illus. 188).51 The attribution was based exclusively on Erhard’s landscape etching, which is a weak piece of work, inferior to all nine of Albrecht’s etchings and quite unlike the Albertina drawing (illus. 180). The unwillingness to see Albrecht’s hand in the Albertina drawing is based on the differences between this drawing and the View of Sarmingstein of 1511 (illus. 165) and the Willow Landscape (illus. 166). But the Coastal Landscape perfectly embodies the qualities that the etchings were trying to publicize, even if it was not a direct model or study for an etching. The Albertina landscape is actually one of Altdorfer’s most remarkable drawings. In no other landscape is a formal theme so persistently worked out and so tightly controlled. The graphic module or cell of this drawing is the collision of two angled strokes, a lively convergence that produces a wedge or splay. This module is recapitulated at every level of the drawing’s structure: in the twitches of foliage, the odd angles of branch against trunk, trunk against earth, the masts and spars of the ships, the ridges of earth in the scooped-out river-bank, and finally in the broadest compositional strokes – mountain profiles, the leaning tree, the receding row of ships, the arc of the cloud. This look of ‘splay’ makes the drawing as a whole feel precarious, high-strung, oversensitive. The look is encapsulated in the thatched farm buildings of the middle-ground, which have an animal-like presence and appear to be on the verge of shifting their stance. By a perspectival liberty, the right tower of the church in the dead centre of the composition is higher than the left tower, as if the building were about to topple or rear back on its hind legs. The landscape etchings try to replicate exactly this degree of graphic control.

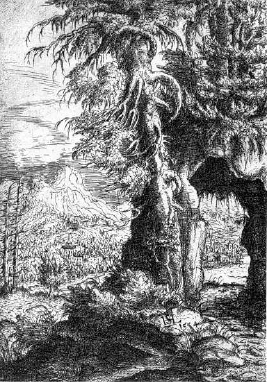

It is hard to believe that Altdorfer would ever have brushed over lines like these with watercolour. Yet the Albertina in Vienna has a set of eight landscape etchings, including all but the Landscape with Watermill, as well as an impression of Erhard’s etching, that have been coolly and expertly coloured with green, brown, red and blue washes. (There are only two other surviving coloured impressions.52) This raises the possibility that the etchings were printed as the skeletons of watercolour landscapes, to be fleshed out with layers of wash by Altdorfer or an assistant before they left the shop; that is, they were meant to remind beholders of Altdorfer’s own painted landscapes. The etchings do share many ideas with the water-colour and gouache paintings on paper, such as the Landscape with Church from the Koenigs collection and the landscapes in Berlin and Erlangen. Altdorfer’s two etchings in vertical format, for example, the Small Fir (illus. 171) and Large Fir (illus. 173), resemble in structure his own watercolours more than they do any of Huber’s pen drawings in vertical format. But the watercolour paintings were not merely coloured drawings, as some have thought, but paintings built upon pen underdrawings. The underdrawings in the Berlin, Erlangen and Koenigs sheets are neither as forceful as the true autonomous drawings, nor as fastidious and intense as the etched lines. It is true that the underdrawings in these watercolours did not need to be concealed – their visibility is part of the effect of the works. But they could never have stood alone. A sketch on the verso of the Erlangen sheet gives an idea of how one of those landscapes may have started out (illus. 190).53

187 Albrecht Altdorfer, View of Schloss Wörth, 1524, pen and watercolour on paper, 21.2 × 30.5. Missing since 1945.

We have seen three watercolour and gouache landscapes by Huber: the Alpine Landscape in Berlin, the Mountain Landscape from the Koenigs collection, and the Landscape with Golgotha in Erlangen (illus. 140, 141). None of these works can be considered to be a coloured pen drawing; the underdrawings are well buried.

But what about the pen drawing with a light, translucent coat of coloured washes? Huber’s Landscape with Footbridge in Berlin would look good even without its colours (illus. 189).54 It resembles his plain pen-and-ink landscapes, even to the ironic prominence of the bridge, blocking the view of the town. Two watercoloured pen drawings can be attributed to Altdorfer: the Milan Cliff of 1509 (illus. 72) and the View of Schloss Wörth. There were several reasons a draughtsman might colour a pen drawing. First, accurate topographical memoranda were frequently coloured, for example the ‘Katzheimer’ group of views of Bamberg (illus. 149). Second, even invented landscape motifs which might later figure in the backgrounds of paintings were coloured with washes or opaque gouaches. The Milan Cliff derives from this tradition. A third type of watercoloured drawing was the composition study for a panel or glass painting. Examples by Cranach and Dürer survive. Finally, an artist sometimes coloured a highly finished pen drawing, perhaps a drawing meant for one reason or another for presentation to a patron. A famous example is Dürer’s Madonna of the Many Animals.55 Altdorfer’s View of Schloss Wörth falls in both the first and last of these categories.

The landscape etchings, then, did not need to be coloured in, any more than did Altdorfer’s or Huber’s finished pen drawings. But Altdorfer would not have been astonished to learn that some subsequent owner had put a brush to them, and he may even have overseen the colouring of the Albertina set. Many impressions of the landscape etchings by Altdorfer’s follower Augustin Hirschvogel, from the late 1540s, are also hand-coloured. Colouring prints was an old practice. Fifteenth-century woodcuts often left the workshop already coloured.56 Altdorfer’s Schöne Maria woodcut – a chiaroscuro woodcut with multiple coloured tone-blocks – imitated in turn the finest of these hand-coloured woodcuts; it was like a pre-coloured woodcut (illus. 122). This was also the procedure of the Briefmaler or ‘paper-painters’, who made simple devotional outlines with stencils and then coloured them in. Engravings were never coloured by their artists; nor, it is safe to say, were the fine, monogrammed woodcuts produced in Dürer’s wake. However, many fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century owners coloured, or had coloured, their woodcuts and book illustrations. For instance, there are the tiny ‘Mondsee Seals’, which have been attributed to the young Altdorfer;57 the fiery Cranach Crucifixion woodcuts preserved in Vienna, Munich and Dresden;58 and many Dürer woodcuts, such as the Bearing of the Cross from the Large Passion in Boston.59 Most of the prints in Hartmann Schedel’s collection, including the engravings, are coloured. Even some much later collectors persisted in adding colour. Perhaps as late as the seventeenth century, a group of engravings by Dürer and Cranach in the Veste Coburg were treated to a lush coat of tempera.60

188 Albrecht Altdorfer, Coastal Landscape, c. 1521–2, pen on paper, 20.6 × 31.2. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The coloured landscape etchings in the Albertina entered the collection as a group. Konrad Oberhuber has recently called attention to the uniform black borders around all the Albertina etchings, and has argued that they are equivalent to the borders on certain other works: the coloured etching of a Large Fir at the Veste Coburg; the uncoloured Landscape with Watermill in Washington; and the Berlin and Erlangen watercolour landscapes.61 If the borders were not applied in Altdorfer’s shop, then presumably they were applied by a single collector. The Erlangen landscape, Oberhuber points out, has a seventeenth-century provenance. The core of the collection of the Margrave of Ansbach-Bayreuth was acquired from the engraver and publisher Jakob von Sandrart, nephew of Joachim von Sandrart and director of the Academy in Nuremberg from 1662. Perhaps all these sheets stem from his collection.

Extremely few impressions of Altdorfer’s landscape etchings, coloured or plain, have survived. There are only three known impressions of the Small Fir and four of the Landscape with Watermill. The most common is the Landscape with Two Firs, with fourteen impressions. The etchings must have been rare even in the early seventeenth century, since there are none in the Peuchel Album in Munich, a nearly comprehensive collection of Altdorfer’s prints completed by 1651.62 Even more important, there are two impressions of Erhard’s landscape etching, but none of Albrecht’s, in the massive collection of Archduke Ferdinand in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which was assembled near the end of the sixteenth century.63 Altdorfer was not reaching for the broadest possible market. He probably released no more than a few dozen impressions of each landscape, and then gave them or sold them individually rather than putting them on an open market. These were highly refined and eccentric experiments in a novel medium. It seems most unlikely that their owners, as Hans Mielke suggested, would have pinned them to the wall.64

The landscape etchings certainly travelled quickly. The Landscape with Two Firs was closely copied in a pen drawing in Frankfurt, dated 1522 and monogrammed I.H.65 A drawn copy after the Large Fir is dated 1522.66 Narziss Renner adapted the right side of the Landscape with Fir and Willows in the background of his large Geschlechtertanz watercolour of 1522.67 In his Prayer Book in Vienna dated 1523, finally, Renner used both the City on a Coast, in his Lamentation, and the Large Fir, in his Visitation (illus. 191).68

189 Wolf Huber, Landscape with Footbridge, c. 1521–2, pen with watercolour on paper, 13.7 × 21.2. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

190 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape, c. 1522, pen on paper, 20.2 × 13.3. University Library, Erlangen.

191 Narziss Renner, Visitation, 1523, miniature from a Prayer Book. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

These adaptations provide a terminus ante quem for the landscape etchings. The dates on the drawn and painted landscapes by Altdorfer and Huber suggest a sudden concentration of interest in landscape in the early 1520s, perhaps exactly in 1522. Altdorfer’s Rotterdam watercolour (illus. 102), Huber’s Alpine Landscape (illus. 140), and Huber’s Rotterdam watercolour are all dated 1522. Four of Altdorfer’s etchings – as well as Huber’s Landscape with Footbridge – are attested in copies or adaptations dated 1522 or 1523. The Dresden View of Schloss Wörth is dated 1524; the Vienna Landscape with Tree and Town, a copy, once bore the date 1525. Only two different sizes of plate were used among the ten etchings. They were conceivably done all at once in 1521 or 1522, the product of a single burst of activity.69 Wolf Huber in his watercolour or gouache landscapes moved steadily away from the graphism and resistant surfaces of the first two decades of the century and instead toward cosmic settings. His drawings increasingly offer themselves as vertical transparent planes, like windows or theatrical frames. With their wide bowed horizons they are again the settings for events, and can summon up the pathos of emptiness. They take up ideas that Huber had already developed in his panel paintings; the bowed horizon line was almost a signature device. These features even invade his pure pen-and-ink landscapes of the 1530s to the 1550s.

Altdorfer too turned back to the scene of the world in his Landscape with Castle in Munich and his Berlin Allegory. But he resisted this temptation in the landscape etchings. It is true that here landscape space spreads outward from the tree, filling volume, and overwhelming the figures it contains. Behind the Small Fir – a huge and prickly tree, as histrionic as the tree in the Berlin Landscape with Woodcutter – a pedestrian crosses a bridge; another passes in a skiff; a wayside cross marks the path to the castle (illus. 171). A tiny wanderer moves into the middle distance of the Large Fir, another figure climbs a staircase from the river bank at the lower left (illus. 173). A traveller skirts the base of the mountain in the Landscape with Cliff (illus. 178). The most suggestive fiction of all is the Landscape with Double Fir, where a pair of enormous trunks, shadowed by a cluster of deciduous trees, sprawls out and takes over the surface of a horizontal panorama (illus. 177). These are colossal trees, already seventy feet high at the upper margin, to judge from the size of the figures at the lower right. A shock of foliage at the upper left, descending from beyond the frame, implies a tree that spreads as well as climbs. This is also the wildest sky among all the etchings. The dark parallels behind dry white mountains – evocative of Dürer’s woodcuts – can be read either as darkest blue or as sunset (in the Albertina’s impression the clouds are coloured pink-orange and the sky is blue, especially nearer the top). This etching expands the Berlin Landscape with Woodcutter outward into space. The same broad path, this time with a pair of wayfarers, loops around the pair of trees and isolates them from the world. The tree-shrine, on the path below and to the left of the trees, has become a proper Bildstock; it is accompanied – just as in the Housebook Master’s print or in the view of Erfurt in the Nuremberg Chronicle – by a cross.

None of the figures in the etchings does anything other than walk or pole a boat. Nobody hunts or ploughs a field. Six of the ten landscape etchings (including Erhard’s) are purged entirely of human life; they are as absolutely silent as the Albertina Coastal Landscape. There are no animals, wild or domestic, in any of these works. In some, like the Landscape with Large Castle, the tableau fades back into air, as if struggling for life after the evacuation of story (illus. 174). In the Landscape with Willow and Fir, dishevelled trees have advanced forward and repelled the figures, taking over the picture surface by main force. The scale of the staffage matters enormously. The sheer magnitude of cliff and tree crushes any human pretension to significance. These are not merely the settings for absent histories. They are negative histories, representations of the inconsequence of human purpose. Suddenly Altdorfer is treading on familiar thematic ground, familiar to us, at least. The etchings, especially the horizontal ones, start to resemble seventeenth-century landscapes. They are far less recalcitrant and demanding than the earlier handmade works, where the ‘folded’ structure of the picture had resisted the spread of the horizon and the impulse to describe terrain. The etchings achieve their spaciousness, and the concomitant elevation of tone, at the cost of a certain intimacy and unpredictability.

And yet in the etchings the linear web retains a powerfully graphic character. The works resist being raised to the perpendicular plane. These are still flat surfaces with no pretensions to transparency. The technique of etching offered a way of bringing the print back to this state of flatness. Because they are made with a round needle rather than the bevelled burin, etched lines have a homogeneous character, especially in these earliest examples of the medium. Depth and colour were elusive. All this impeded the slide back toward theatrical illusion.

Space in the etchings opens up around the tree. Yet the tree lingers at the front, rooted stubbornly in the foreground. This opening of the space is not a grand retreat of the point of view, generously embracing wider swaths of terrain. It is really just an inflation of the picture surface, a lateral extension. The notional standpoint remains fixed, and the symbol of this is the brutal truncation of the foreground trees. The trees are not diminished in order to fit them within the frame, nor are they shunted to the side.

In the narrative and devotional images that immediately preceded the independent landscape, the depicted tree stood in a supplementary relationship to subject-matter. It filled a void at the centre of the narrative picture, and at the same time it brought something unanticipated to narrative: a superfluity of information about setting. The supplementary tree had the character of a parergon: it was indispensable to the proper work of the painting – telling a story – and yet stood outside that story and did not belong to it. Now, in the landscape etching, the centring of the supplement is complete. The public arrival of landscape as the sole iconographical justification for a picture – as subject-matter – marks the end of the tree’s destabilizing liminal role within the picture. Landscape in the first two decades of the century still had a dynamic, two-faced structure. An artistic personality in the world, a real historical actor and the physical manipulator of a pen or brush, could take up residence in landscape, and from that vantage-point control the exchange between the beholder and the picture.

Kant, in the passage in the Critique of Judgement singled out by Derrida and discussed earlier, offered three examples of supplements or parerga: a frame around a painting, a garment on a statue, and a column on a building. In the course of this book, the tree has appeared in all three of these guises, and in each case, in turn, it was translated to the heart of the picture. The foreground tree at the right or left edge of the picture was a parergon when it served the function of a frame. It protected the event at the centre from the outside world, particularly in drawings or prints, which had no natural or architectural frame around them. The gaze rolled around the trunk and into the fictive space. The branch and the vine had already insinuated themselves into this position in German altarpieces. But in Altdorfer’s independent landscapes – the Rotterdam and Berlin water-colours, the London panel, the Willow Landscape in Vienna, the etchings – this framing tree abandoned its post at the margin. In these pictures there is nothing left to frame, nothing between the frame and the background. The tree moved to fill the lack by mimicking, with anthropomorphic postures and gestures, the human subject. But in doing so it upset its own parergal equilibrium, for now it filled a lack completely and participated fully in the work of the picture; there was no longer anything gratuitous about its contribution.

The tree was also a parergon when its foliage hung on the picture like a garment. The leaves of the framing tree adhered like a fringe to the sides of the picture and climbed across the upper edges. Passages of foliage could appear anywhere else within the picture too, virtually unmotivated, in any scale and at any distance. Foliage distracted, and it determined mood. But in the Munich St George, the garment overwhelmed and smothered the body, or rather, the story. In the Berlin watercolour, the garment clung to and became one with the body; it was indistinguishable from its sculptural skeleton. This was no longer the sort of statue which Kant had in mind.

The tree was, finally, a parergon when it stood like a decorative column before or within the architecture of the scene, imitating a structural element but in fact performing merely rhetorical tasks. Later it abandoned the pretence to structural utility. The tree moved into the open, cleared space around itself, and solicited attention. In the etching of a Landscape with Double Fir and in the Berlin watercolour, the tree actually monopolizes attention. The detached column, the column which supported no weight, was for Christians a clear danger signal, since it usually bore an idol. Pagan idols in illuminations and panel paintings were always represented mounted on free-standing columns. The Golden Calf stood on an open-air column. Solomon himself once fell under the spell of such an idol; the subject was engraved by the Housebook Master and drawn by Altdorfer on coloured ground.70 The medieval Church abhorred the free-standing column, and many churchmen were appalled by the stone Virgin erected in Regensburg in 1519 to attract pilgrims (illus. 134). Perhaps that is why Altdorfer so often lops off the crowns of his trees.

In the etchings, even the mountains are brought in close, in the sense that they are presented as experienced terrain, as massive and muscular obstacles to movement, as sites of terror and somatic ordeals. These are no longer the fanciful, bearded cliffs of the Netherlandish or German background, the interchangeable stage-flat lifted from the workshop modelbook. Instead, they point forward to the Battle of Alexander and to Bruegel. The mountains are also the markers of the local, for they attest to a specifically Alpine experience. They belong to the first generation of images that do so. With their trees, blank mountains, scored skies and castles they are like catalogues of German motifs – drawn both from the land itself and from Dürer’s prints. They have become the counterparts to the Flemish visual landscape catalogues.

But unlike the Flemish landscapist, Altdorfer does not marshal all his pictorial means to the goal of perspicuous planar presentation, to display. Instead the key concept is ‘splay’, a bending, wrenching and distortion of matter that results from pulling it forward and pressing it against the front plane. This bending produces a new pattern for composition, based neither on the principles of two-dimensional symmetry or organic order, nor on the rational projection of the spatial continuum and its contents onto the plane. All the force, power, violence and difficulty of the landscape smashes against the plane and produces the twisted branch, the exploding bush, the scooped sandbank and the arcing pen line.

All these landscapes are fictions. The new frame isolates the picture from the world and establishes it as the zone of the hypothesis. Fictions serve many purposes, many of which emerge out of direct comparison with the empirical world. But the relationship between the fiction and the empirical world is not constant, and cannot be diagnosed from the fiction itself. In one crucial sense, however, Altdorfer’s drawn and painted landscapes were not complete fictions. Line and brushstroke were still understood in those pictures as the indexes of an authorial hand. They established a link to the absent author that was at least consistent and reliable. That claim is swept away in the landscape etchings. The etching tries to replicate the pen line, and indeed it succeeds more fully than an engraved or woodcut line ever could. But it falls just short. In the City on a Coast or the Landscape with Watermill, the light touch often translates in the etching into a weak and broken line, an insubstantial sequence of dots and dashes (illus. 172, 179). And the swift or truly thoughtless pen stroke can never be rendered in etching at all.

Altdorfer’s etchings also betray their remoteness from the hand in one drastic way: they all lean toward the left. All the tree-loops on mountain-sides and blades of grass in foregrounds slope backwards, to the left. Trees, too, tilt to the left, most strikingly in the Small Fir and the Landscape with Large Castle (illus. 171, 174). The filaments of hanging moss swing with the trees, parallel to the trunks, as if carried by a breeze from the left. Shading lines run from upper-left to lower-right. Buildings and even entire mountains list to the left. Reversal of the image in the printing process has a devastating effect. Once perceived, it dominates the experience of the etchings. One becomes aware, all at once, that Altdorfer’s drawings had been leaning in a comparable way toward the right, and that this leaning had failed to interfere with the experience of the landscape. In the Albertina Coastal Landscape, the buildings pitched wildly to the right; in an etching they would have pitched wildly to the left (illus. 188). And yet in the drawing, if noted at all, they were perceived as contributions to the illusion of a homogeneous space, not as disruptions. There is no lateral symmetry, clearly, in the beholder’s mind. The tilt to the right is absorbed into the experience of the drawn landscape because the beholder reads it as a sign of the manual origins of the picture. This tilt is a common phenomenon in landscape. In fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Franco-Flemish manuscripts, or in Sienese panel paintings, ranges of hills often tilt in unison to the right. The July fresco at Trent is a good example (illus. 16). In early seascapes, waves usually lean to the right, for example in Bruegel’s Naval Battle in the Port of Naples, in the Galleria Doria-Pamphilj in Rome, or in his pen drawing of a Seascape with a View of Antwerp in the Seilern Collection. The forward-leaning pen or brush stroke, from lower-left to upper-right (or vice versa), is the natural stroke of the right-handed artist. In the drawing or the painting, the pitch to the right was a direct index, a trace, of the natural movement of the hand. The rightward tilt ought to ruin the picture’s iconic claim to resemble the empirical world. (Whereas the index, in Peirce’s familiar typology, is fabricated by the very object or event that it refers to, the icon merely resembles that object or event.) But it does not ruin the illusion, because the beholder accepts, and may even prize, the handmade character of the picture.

In the etching, the pitch is mechanically reversed. Tilt can no longer pass itself off as an index. It is not an icon of anything either. It only reminds the beholder again that the picture is not hand-drawn. Because the etching expels the trace of the artist, it is a more complete fiction than the hand-made work. The landscape drawing and painting evicted subject-matter, but installed a style in its place, replacing one claim to presence with another. The etching carries out a more thorough supplanting of existence by depiction. This book has tried to demonstrate the inadequacy of the earliest landscape drawings and paintings to any physical or created nature, to a natura naturata. The etchings are in turn inadequate to a secondary nature, to the creative imagination that had fashioned itself in the likeness of a creative nature, a dynamic natura naturans. Moreover, the etchings disclose, retrospectively, a complex and hidden aspect of the handmade works’ inadequacy. The etchings reveal a surreptitious coincidence and alliance between the left-to-right pen stroke, an index of the act of creation, and the normal left-to-right trajectory of narrative, an icon of temporal movement. Because the installation of the artist’s personality in the picture was dependent upon the indexical quality of the pen stroke, even the empty landscape retained a vestigial tie to narrative. The full extent of landscape’s structural roots in narrative is revealed only when it is reversed in the etchings. Once it is perceived, the left-to-right compositional structure of the early landscape sabotages any pretence to adequacy to nature. The primary experience of nature which landscape, at some level, promises to reproduce is nowhere to be found. A technological innovation inadvertently unmasks a representational convention, and the entire process ends up demonstrating the apriority of the picture.

The etching was supposed to reproduce the special qualities of the pen drawing. It registered with unprecedented sensitivity the unique trajectories of the hand. But the product itself, the new work, was no longer unique. It was no longer a relic of the artist. The print enshrined the creative gesture as the new foundation of the work of art. And yet in that reproduction the gesture itself was lost. At the very moment that paintings and drawings were first collected because they were original, prints began to be collected as if they were original. Together with bronze sculptures – casts of ‘lost’ wax or clay originals – or casts of prestigious antiquities, themselves copies of lost Greek originals, engravings and etchings were among the collector’s items par excellence of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The compulsion to assemble a complete corpus of prints by a single artist, or to subject a collection to various taxonomic logics, led to the modern disciplines of connoisseurship and the catalogue raisonné. The print, by dissociating the value of the work from any claims to physical contiguity with the artist’s hand, dematerialized that value. The attributes of the successful and desirable work were increasingly nameable and describable.

Order and disorder

In her remarkable book on the classical landscape of the seventeenth century, Margaretha Rossholm Lagerlöf characterized earlier landscape as a genre suspended in ‘a state of amazement’. The painter or draughtsman opened his eyes to the terrain and tree before he wielded any concepts for ‘eliciting, elucidating, controlling’.71 In 1520 there were still no rules. The publication of the landscape over the course of the next generation brought both loss and gain. Under the gaze of an increasingly knowing public, perpetually overcoming its own amazement, some of the oblique momentum of the original experiment petered out.

The direct trace of personality in the work was replaced by a fictional personality, an absent and more durable authorial ego. As Altdorfer grew in worldly stature, he disappeared from his works. Just like Dürer, Altdorfer is increasingly elusive in the last decade of his life. In 1526 he was elected to the Inner Council; in 1528 he was elected to the mayorship for a term, an honour he had to decline in order to finish the Battle of Alexander (illus. 8). What was he producing in these years? Slick, densely-wrought engravings, mostly pagan and erotic, and an eclectic handful of panel paintings, each more unorthodox and adventurous than the last. Altdorfer’s artistic personality dissipates in a welter of cosmopolitan references and a centrifugal impulse to experiment. In these works, beneath all the extravagances of iconography and presentation, landscape has reverted to older modes. In the Battle of Alexander, narrative is toppled from the foreground and pushed into a vast background. This is the opposite of paintings by Raphael or Michelangelo, which magnify the heroic and pull it forward, compressing the background. The Battle of Alexander is the apotheosis of the ‘world-landscape’: a fictional assemblage of natural and constructed components of the world, that is, in effect, a visual catalogue of the world. The world-landscape began as an idea, and was originally represented only in shorthand, summarily, as in the Tomb of Darius or on Pisanello’s medal. The Netherlanders transferred the idea to the painted panel, where they could tilt the surface of the earth backward into space. Landscape was gathered together under the force of a fixed gaze. It became spatial rather than experiential. In Altdorfer’s Allegory (dated 1531) in Berlin, a dimly intelligible proverb – Pride and Poverty? – becomes staffage within a hazy, sparkling panoramic landscape, Netherlandish in character (illus. 192).72 By this time Altdorfer must have seen landscapes by Joachim Patenir, perhaps the Assumption of the Virgin commissioned by Lucas Rem of Augsburg around 1516–17, now in Philadelphia.73 This was one of Patenir’s earliest works and in its atmosphere and almost plausible hilly terrain it particularly resembles Altdorfer’s Allegory. Yet in the Allegory the spaciousness is closed on the right by a true forest landscape, an impenetrable stand more ominous than any of Altdorfer’s own earlier thickets, indeed more like a forest landscape by the later Flemings Bruegel or Coninxloo. Lot and His Daughters in Vienna, dated 1537, a year before Altdorfer’s death, depicts an incestuous unequal couple: a leering male nude, life-size, lying with his own daughter, forms a horizontal sward of flesh that is almost unbearable to look at (illus. 193).74 Part of the background is apparently a paraphrase of a little-known northern Italian panel, a nude in a landscape (illus. 194).75 This modest picture was attributed by Berenson to the young Lorenzo Lotto and dated to c. 1500. The figure and setting are both derived from Dürer and Jacopo de’ Barbari. The flow of influence thus came full circle when the picture found its way into Altdorfer’s hands. Altdorfer has set his story in a wooded landscape, and at the same time nested a second landscape within the picture, just as in a fifteenth-century Netherlandish or Italian painting.

192 Albrecht Altdorfer, Allegory, 1531, oil on panel, 28.9 × 41. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

Altdorfer’s lasting impact in the German tradition – witness the comments of Quad von Kinckelbach and Sandrart – was felt in the graphic media. The so-called ‘Little Masters’, imitators of Altdorfer and Dürer, supplied the amateurs and collectors with dozens of tiny engravings, some hardly larger than postage stamps, which illustrate arcane and often lascivious curiosities of mythology and ancient history. But other Germans followed Altdorfer and Huber into landscape. One empty woodcut landscape is almost completely ignored in the literature (illus. 195).76 The initials NM that appear on some impressions of this work refer to Niklas Melde-mann, a Briefmaler in Nuremberg who published the print. But the design is attributed on stylistic grounds to Niklas Stoer, a painter active in Nuremberg from the 1530s until the 1560s. The black borders at the right and lower edges have led nearly every commentator to place the sheet in a lost sequence of woodcuts illustrating a battle or a parade, something like the Triumphal Procession Altdorfer designed for Maximilian (illus. 136).77 But structure and motifs are derived from the independent landscape, etched and drawn. It is not impossible that Stoer was experimentally extending the medium of woodcut into the iconographic territory opened up by Altdorfer and Huber.78

193 Albrecht Altdorfer, Lot and His Daughters, 1537, oil on panel, 107.5 × 189. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

194 Northern Italian master, Nude in Landscape, c. 1500–10, oil on panel. Whereabouts unknown.

195 Niklas Stoer, Landscape, c. 1530s, woodcut, 28.2 × 40.4. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

The first etched landscapes were already being produced in Altdorfer’s lifetime by a German master who used the initials P.S. This artist made and signed pen drawings that are very close to Wolf Huber’s. An etching of a fortified city on a coast, a unicum in Königsberg (Kaliningrad), is dated 1536.79 The landscape etchings of Jakob Binck, an artist born around the turn of the century and trained in Nuremberg, may date from the 1530s or even earlier. His Landscape with Castle published an idea that was really Huber’s, if not Huber’s actual drawing (B.97; illus. 196).80

The most enterprising students of Altdorfer’s and Huber’s landscapes were Augustin Hirschvogel and Hanns Lautensack, who made hundreds of landscape drawings and etchings in the 1540s and 1550s. Hirschvogel, the son of a successful Nuremberg glass-painter, was born in 1503. He travelled widely – stopping in Regensburg, perhaps, in the 1530s – before settling in Vienna between 1544 and his death in 1553.81 Hirschvogel made thirty-five landscape etchings, some with small biblical scenes, dated 1545 to 1549. The Conversion of St Paul provides the text of the Lord’s query (Acts 9:4) in the upper right (illus. 197).82 But without the heavenly ray one would never find the figure of Saul himself, an indistinguishable lump, out of scale, lost in the flat landscape. Three of Hirschvogel’s etchings directly follow landscape drawings by Huber.83

Hanns Lautensack was born around 1520 and also ended up in Vienna working for King Ferdinand.84 He, too, was the son of a painter, Paul Lautensack of Bamberg. And like Hirschvogel, Hanns Lautensack was at least as familiar with Huber’s landscape drawings as with Altdorfer’s prints. In 1553 and 1554 he published a series of etchings in both horizontal and vertical formats, like this swarming Landscape with a Natural Stone Arch (illus. 198).85 Many etchings by Hirschvogel and Lautensack ended up in the print collection of Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol (the son of their patron King Ferdinand), alongside the landscape prints published by Hieronymus Cock in Antwerp and the pastoral woodcuts of Titian and Campagnola.

|

196 Jakob Binck, Landscape with Castle, c. 1530, etching, 11 × 8.1. British Museum, London. |

The earliest possible evidence of an international reception of the German prints is the series of etched landscapes set in elaborate frames by Antonio Fantuzzi, one of the Italians working for Francis I at Fontainebleau. Fantuzzi’s prints have great documentary value because they reproduce Rosso Fiorentino’s ornamental stuccoes at Fontainebleau, not all of which survive. But in the centre of these etched cartouches, in place of the mythological or allegorical scenes of Rosso’s original scheme, Fantuzzi inserted landscapes of his own design (illus. 199).86 Where did he get such an idea? He knew the Venetian woodcuts, and he may have known Netherlandish landscape drawings in the wake of Patenir, for example those of Cornelis Massys. But had Fantuzzi seen any etchings? One of his landscapes looks particularly German: a vertical wooded scene with a church and travellers.87 Zerner dates Fantuzzi’s prints to about 1543; the earliest dated landscape etching by Hirschvogel is 1545. Perhaps Fantuzzi saw something even older by Binck, the Master P.S., or even Altdorfer. Rosso’s frame works the same effect on landscape as a text. The frame has nothing to do with the picture inside. It is imposed upon landscape from the outside, an emblem of the affectionate but condescending Italian taste for Northern landscape. This is landscape’s mock independence. The frame is really the work, for it persists from Rosso’s original to Fantuzzi’s reproduction. The landscape in the centre is interchangeable.