2

Frame and Work

Max J. Friedländer once wrote that Altdorfer invented not landscape painting, but rather the landscape painting.1 This book is about that material object: the painted panel and the watercolour painting on paper, but also the pen-and-ink drawing and the etching. Altdorfer’s wooded places look empty precisely because they appear on detached surfaces surrounded by frames. They are places physically severed from the figures and stories that would make them useful again. The independent landscape is an object defined by what it includes and excludes, and it is the frame that performs that selection. But the frame also cuts the picture off from the physical environments that would ordinarily legitimate its ineloquence. We need to bring the physical properties and historical coordinates of this object into clearer focus.

The German artist’s career

Most German painters at the beginning of the sixteenth century earned their livings painting pictures of Christ, the Virgin and the saints. The public appetite for sacred images was voracious. The Swiss reformer Huldreich Zwingli, who liked pictures but felt compelled to condemn them,2 lamented in 1525 that ‘a reasonably old man may remember that there once hung in the temples not the hundredth part of the idols which we have in our times’.3 Yet the repertory of subjects was still nearly as meagre as it had been two generations earlier. How was a painter to win more than a merely local reputation painting sacred images? The most conspicuous setting for painting and the most profitable artistic enterprise was the altarpiece. On the largest altarpieces, the huge retables with one or more pairs of hinged shutters and towering crowns of carved wood, the painter and the sculptor worked alongside one another, surrounded by carpenters, cabinetmakers, ironsmiths, locksmiths and sundry lesser painters, apprentices and shop-hands. The successful artist was the one who managed to control such projects: he subcontracted, he kept his own workshop busy and solvent, and he earned the confidence of the community or the church officials. At first it was the painters who tended to oversee such projects; later, as the retables became more complex, the sculptors began to dominate. Most powerful were the great sculptor-painters, such as Hans Multscher, Michael Pacher and Veit Stoss.4

Under these circumstances it was difficult to build a super-regional reputation. News about successful altarpieces travelled slowly and randomly, along rivers and trade routes. Eventually, the artist-entrepreneur would win another commission in a different city. But the big retable projects lasted for years, as long as a decade, and in the meantime a reputation might stagnate. Moreover, a reputation was likely to be one-dimensional. The ability to build huge and materially splendid altarpieces frequently reflected no more than economic buoyancy and organizational talent. Clients may have known outstanding painting and sculpture when they saw it, but they did not necessarily know how to talk or write about it. It was easier to explain how a complicated retable worked – how the shutters opened and closed, what story was told in the central section, or shrine – or to marvel at audacities of scale, than to tell what a painting looked like, how it was beautiful, why it told the story so effectively. A reputation travelling by word of mouth alone, dependent on brittle and poorly articulated memories, would soon evaporate.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, consequently, the south German landscape was fragmented into local artistic dominions. In Nuremberg, Dürer’s teacher Michael Wolgemut oversaw the largest workshop and garnered the major commissions. Hans Holbein the elder, father of a more famous son but an acute observer of the physical world in his own right, dominated Augsburg. The outstanding figure in prosperous Ulm was Bartholomäus Zeitblom, a blandly austere, and now completely neglected, painter. The leading Bavarian altar painters were Jan Polack in Munich and Rueland Frueauf the elder in Passau and Salzburg. The horizons of most painters and sculptors ended with their city walls. Court artists, meanwhile, were either anonymous manuscript illuminators, or – like Emperor Maximilian’s artistic factotum Jörg Kölderer – competent but uninspired handymen, variously responsible for designing festivals, organizing collective projects, illustrating genealogical treatises and decorating princely residences.

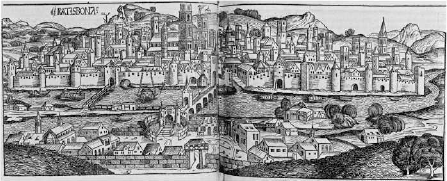

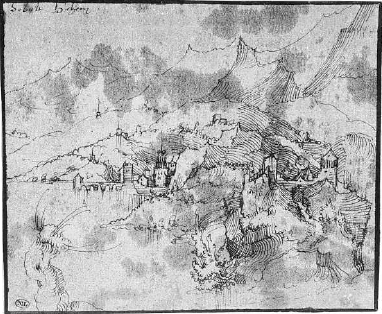

Altdorfer’s Regensburg, ‘Ratisbon’ in Latin, roughly equidistant from Munich and Nuremberg, was an episcopal see and free Imperial city with a grand medieval past. In the twelfth century Regensburg had been the leading trading centre in southeast Germany. The Dominican Albertus Magnus, mentor of Aquinas, held the bishopric in the 1260s. Book painting had flourished in the local monastic workshops. Aeneas Silvius, in his ingratiating survey of German lands and customs, written in 1458 immediately before he was elected Pius II, called attention to the magnificent stone bridge across the Danube, built in the mid-twelfth century and even today carrying two lanes of traffic; to Regensburg’s many churches, especially the cathedral; and to the Benedictine monastery of St Emmeram, which reputedly sheltered the bones of St Denis, piously stolen from the abbey in Paris.5 Prestige earned Regensburg its own two-page spread in the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 (illus. 36).6 The city is thick with church spires and patrician defensive towers. The cathedral, accurately enough, is shown still under construction.

But in recent decades the city had fallen into debt and political disarray. Regensburg fell far behind Nuremberg, Strasbourg, Ulm and Augsburg, the Imperial cities to the west, each of which was four or five times as populous. In a schematic image of the Imperial cities in the Nuremberg Chronicle, Regensburg was classed, together with Cologne, Constance and Salzburg – all ecclesiastical cities that had seen better days – among the Rustica, and represented as a cluster of shabby farm buildings. Old buildings in heavy grey stone were infrequently replaced by modern structures, and indeed Regensburg remains today one of the best-preserved Romanesque cities in Europe. Around 1500 it had 10,000 inhabitants, but no major panel painting workshop. The wing panels on the high altar of the cathedral had been painted in the 1470s by an outsider, possibly Rueland Frueauf of Salzburg.7 The biggest local painting workshop belonged to the manuscript illuminator Berthold Furtmeyr.8 It is possible that the Regensburg manuscript painters were powerful enough to resist the introduction of the press. For apart from a missal published in 1485 by a Bamberg printer who had moved his equipment temporarily to Regensburg, not a single book was printed in the city before 1521.9

36 Workshop of Michael Wolgemut, View of Regensburg, woodcut, from the Liber chronicarum, 1493, 19.2 × 53.5. Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University, New Haven.

It is assumed that Altdorfer was actually born in Regensburg, and not in one of the numerous villages in Germany and Switzerland called Altdorf, because his Christian name and those of his siblings Erhard and Aurelia were associated in various ways with the city’s past. Their father was almost certainly the painter Ulrich Altdorfer, who was inscribed as a citizen in 1478 but then in 1491 was forced to quit the city in poverty. Albrecht Altdorfer later returned to Regensburg. In 1505, probably in his early twenties, he was entered in the books as a citizen, described as a ‘painter from Amberg’. Amberg was a court city thirty miles to the north, the capital of the Upper Palatinate, and Ulrich may have settled there after he left Regensburg. Yet neither father nor son is recorded as a citizen of Amberg at any point between 1491 and 1505. Perhaps Albrecht was working temporarily in Amberg shortly before he returned to Regensburg to claim his citizenship.10

Albrecht and his brother Erhard were undoubtedly trained first by their father. Although Altdorfer’s works have little in common with Berthold Furtmeyr’s frank and imperturbable miniature style, the brothers may well have studied under Furtmeyr as well. Among the most appealing possibilities is a Prayer Book in Berlin commissioned probably by the Bishop-Administrator of Regensburg, Johann III of the Rhineland Palatinate, and painted in 1508 or shortly thereafter.11 The full-page miniatures, based on Dürer’s prints, must have been executed under Altdorfer’s direct impact, or even supervision. And yet no early example of Altdorfer’s own miniature work has ever been found.12 The best argument for his origins as an illuminator is not documentary but deductive: he is too facile with the smallest brushes, and too comfortable on parchment, to be self-taught. Moreover, it seems highly unlikely that the Emperor Maximilian and his historian Johann Stabius would later have commissioned the Triumphal Procession miniatures from Altdorfer if he had no professional credentials at all (illus. 137).13 These were not the only miniatures produced by Altdorfer’s shop for Maximilian. The full-page hunting scene and the marginal portraits of Habsburg rulers on a copy of the so-called ‘house privileges’ are dated 1512 and signed ‘A.S.’ by an artist under the direct influence of Altdorfer.14

Altdorfer’s earliest surviving works are not book illuminations. His verifiable output before 1510 consists of four small panel paintings, fifteen engravings, and ten drawings. Yet already before the end of that decade, Altdorfer had begun working for the Emperor, and had earned a commission to paint a large altarpiece for the abbey church of St Florian near Linz, some days’ journey down the Danube from Regensburg. By 1512 his drawings were already being imitated and copied by a flock of pupils. Doubtless there were smaller altar projects in those early years, now lost or even, perhaps, unrecognized. The scaffolding of Altdorfer’s success was nevertheless amazingly impalpable. This fragility is deceptive. The lesson of Dürer’s career, which was proceeding ten or fifteen years in advance of Altdorfer’s, was that a reputation is more efficiently broadcast by signed sheets of paper than by a huge, immobile and labour-intensive altarpiece, or by a time-consuming illuminated manuscript that would be shut up in a library for years.15

Dürer’s pre-eminence as a model has been slightly underrated in the Altdorfer literature of our own century. In 1675, Joachim von Sandrart, the German academician and biographer, made no mention of any connection between the two artists.16 Back in 1609, however, Matthias Quad von Kinckelbach, an engraver and historian, had described ‘Adam Altdörffer’ of Regensburg as Dürer’s pupil. Granted, this was a connoisseurial judgement. Quad von Kinckelbach mainly knew the late engravings, for he grouped Altdorfer together with Jacob Binck, Sebald Beham, Georg Pencz and Heinrich Aldegrever: ‘Their work, in which one still perceives clearly the Dürerian vestigia, leads one to believe that they were his apprentices.’17 But in 1831 Joseph Heller, the biographer of Dürer, recorded a drawing in red chalk of a sleeping old woman that, according to an ‘old’ inscription on it, had been given by Dürer to Altdorfer in 1509.18 That drawing is lost; it may have been a copy of one of two extant pen drawings by Dürer of sleeping old women (or men) with covered heads.19 We ought to keep in mind this shard of evidence, however exiguous, and in addition remember that the executors of Altdorfer’s estate found among his possessions a panel painted by Dürer.20 An encounter between Altdorfer and Dürer in 1509 is entirely credible. There is no need to insist on a face-to-face meeting. Altdorfer knew Dürer’s prints by heart. In 1509, for example, he made an engraving of a standing Madonna and Child based closely on an engraving by Dürer of 1508.21 Dürer was, in these years, overwhelmingly the outstanding silhouette in the fields of vision of ambitious German painters. Indeed, Dieter Koepplin, impatient with unnecessarily circumstantial explanations of the sources of Altdorfer’s style, once protested that the towering figure of Dürer would suffice; beyond that, the only preconditions were that Altdorfer ‘have good brushes and pens at his disposal and get enough to eat’.22

Dürer offered a new model of the painter’s career. He demonstrated that a reputation was most effectively disseminated by signed and dated pieces of paper. The practice of signing pictures with initials or monograms was more elaborately developed in southern Germany than anywhere else in Europe because of the example of engravings. The German engravers of the fifteenth century regularly used monograms. Martin Schongauer of Colmar monogrammed all his engravings. Schongauer was also the first German artist to build a national reputation. He did this by capturing the attention of literary humanists, who transformed his colloquial epithet Hüpsch, or beautiful, first into Schön, evidently with mnemonic or alliterative reference to the surname, and then into Latin.23 For at least a generation Schongauer remained, for many people, a legendary figure, perhaps the only non-local artist known to them by name.24 The young Dürer pursued that reputation in 1492 only to arrive in Colmar too late, a year after Schongauer’s death. Later in the decade, after his first Italian journey, Dürer began building his own reputation through monogrammed prints. The famous monogram ‘AD’ appears on an engraving for the first time around 1495, on the Virgin with the Dragonfly (B.44). Dürer was the first engraver to nest one initial inside the other. He must have done this to distinguish his monogram formally from all the others, much as Schongauer had distinguished himself by using antiqua capitals in his monogram and by separating the initials with a cross. Around 1496 or 1497 Dürer began monogramming his woodcuts. This was an entirely new step. Many fifteenth-century book illustrations had been marked with single, or sometimes two, initials. These almost surely identified the cutter and not the designer, and probably meant nothing outside the trade.25 Other wood-cuts were signed with full names, indeed earlier and more often than engravings were. These, apparently, designated the artist responsible for the drawing.26 Until the 1480s, ambitious painters scarcely got involved in woodcut book illustration. The pioneer was Dürer’s teacher Wolgemut.27 But Dürer went a step further when he began monogramming woodcuts printed on separate sheets of paper. He was offering them as works of art, alongside his engravings and even his painted panels.

Dürer immediately attracted the attention of literary humanists and antiquaries who wanted a contemporary German cultural hero, a rival figure to the Italians.28 Conrad Celtis, for example, wrote a series of Latin epigrams on Dürer before 1500.29 The result of the combination of self-inscription in prints and the efficient distribution of prints was that Dürer’s early fame was quite uncoupled from his painting. Like Schongauer, he caught the attention of humanists with prints; but in Dürer’s case the reputation actually addressed the prints, and in some circles, no doubt, even the drawings. Erasmus, for example, praised Dürer’s ability to depict even meteorological phenomena and the human character with black lines alone.30 Dürer had found his ideal audience. The humanists themselves, with whom he enjoyed manifold personal contacts, convinced him of the urgency of fashioning a reputation. In his drafts for the treatise on painting, Dürer initially insisted on the disinterestedness of artistic activity: ‘Painting is useful’, he wrote, ‘even when no one thinks so, for one will have great pleasure occupying oneself with that which is so rich in pleasure’. But then he quickly conceded the attractions of fame: painting is also useful because ‘one wins great and eternal remembrance [Gedächtnis] with it, if one applies it right’.31 Other enterprising artists took Dürer’s career as a model. The field of activity for painters – the subject-matter they could treat, the kinds of objects they could make – had become too narrow and limiting. Talent was abundant, and appreciative beholders and buyers scarce. A generation of painters born between 1470 and 1485 imitated Dürer by launching their careers with small private paintings and graphic work, by going over the heads of the large workshops, so to speak, directly to a public. Success came quickly. In 1502, the year Lucas Cranach was first documented in Vienna, Altdorfer, Matthias Grünewald and Hans Baldung Grien were still unheard from, and Hans Burgkmair had produced only insignificant works. But only a decade later these five figures, alongside Dürer, dominated German painting. By that time Dürer had already received and completed his great commissions and had more or less retreated from altar painting into graphic work and theoretical writing. The others had all established conspicuous public careers. Baldung had completed his stint with Dürer in Nuremberg and set up shop in Strasbourg; in 1513 he was to begin work on a high altarpiece at Freiburg. Cranach presided over a vast workshop at the court of the Elector of Saxony in Wittenberg. Burgkmair supervised a huge painting and graphic industry in Augsburg. Grünewald had begun work on his altarpiece at Isenheim probably in 1509.

By the early years of the second decade, moreover, Dürer, Burgkmair, Cranach and Altdorfer were all working for the Emperor. They could do this without taking up residence in Innsbruck or Vienna, for Maximilian was merely one of many clients. What was the source of their sudden stature? The great German painters of that generation, with the exception of Grünewald,32 all emerged on the strength of their graphic work and in general their smaller, portable works. They all monogrammed their prints and small paintings. Their early success in this new market won them still more lucrative traditional commissions and granted them a psychological margin for formal and intellectual experimentation. They earned reputations among literary humanists who had influence with the Emperor. They even built up workshops based on their graphic practice: young artists came to Dürer and Burgkmair and were put to work designing woodcuts. In the decade of the 1510s, the years of their mature fame, these artists consistently distinguished themselves from contemporaries such as Martin Schaffner and Bernhard Strigel, who produced no small-scale works at all that we know of, or Jörg Breu, Hans Schäufelein, Hans Kulmbach, Leonhard Beck, Hans Springinklee and Wolf Traut, whose graphic work consisted mostly of book illustrations.

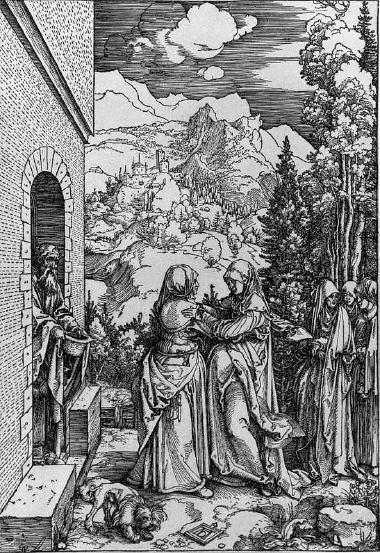

Dürer provided this generation not only with the example of his career, but also with a new set of criteria for discriminating among works and among artists. These criteria were ultimately formal and intimate; they were aspects of execution rather than invention. But they were given breathing space, room to unfold and display themselves, in the new realms of subject-matter, the new formats and media, and the new compositional formulas opened up by Dürer. Together with the nomadic Venetian Jacopo de’ Barbari, Dürer introduced pagan subject-matter to the German engraving. He initiated a massive extension of the artist’s activity beyond the altarpiece, into private and portable objects. He inspired even journeyman artists to monogram their works. He advanced the techniques of engraving and woodcut until they were capable of displaying the most inimitable and distinctive attributes of a draughtsman’s hand and registering broad ranges of authorial tone. Finally, he introduced new narrative tactics and an unprecedented attentiveness to the tension between subject-matter and setting, including landscape.

The first German artist to compete with Dürer on his own terms was his exact contemporary, Lucas Cranach. Cranach was born in 1472 in Kronach in Upper Franconia, fifty miles north of Nuremberg. Nothing is known of his activities before the first years of the new century, when he surfaced in Vienna. There he painted a pair of wedding portraits for the poet, physician and university professor Johann Cuspinian and his wife Anna Putsch, daughter of an Imperial chamberlain and sister of a cleric (illus. 37). Cranach painted another pair of portraits, dated 1503, for an unidentified man, possibly a jurist, and his wife.33 He placed all four sitters in outdoor settings among symbolically charged flora and fauna. The outdoor setting itself is not unprecedented. A portrait of a long-haired young man with landscape visible over each shoulder, for example, is often attributed to Dürer, and is dated to the late 1490s.34 But Cranach has set his landscapes vibrating. He embeds astrological and alchemical symbols in terrain, and naturalizes them as diminutive figures and animals. The combat of eagle and swan above the head of Anna Putsch signifies a conjunction between Jupiter and Apollo: a favourable complement to her husband’s melancholic temperament. The red parrot associates Anna Putsch with the sanguine. The women in the backgrounds of both portraits – one linked with fire and the other with water in the female pendant – incarnate a purifying proximity to elemental nature. Nature serves as inspiration to Cuspinian, the neo-Platonic poet. Cosmic harmony is both precondition and object of his writing.35

37 Lucas Cranach, Portrait of Anna Putsch, c. 1502, oil on panel, 59 × 45. Collection Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur, Switzerland. |

|

The same people who commissioned Cranach’s Viennese portraits very likely also took an interest in Cranach’s independent sacred images, such as the astounding Rest on the Flight into Egypt of 1504 (illus. 38).36 The painting is a simplification of Dürer’s woodcut Holy Family with Three Hares (B.102). But unlike in a print or a drawing, Cranach’s figures detach themselves instantly from their ground. The figures are all pale flesh, hair, and warm, manifold fabrics, completely unlike the earth that supports and shelters them. Nevertheless, the bough of the fir-tree probes forward into the animated circle, half human and half divine, and alights on Joseph’s shoulder. This physical overlapping of setting and subject-matter at the very centre of the picture is one of the boldest passages of the German Renaissance.

By 1505, when he was called to the court of the Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony, Cranach had already produced a considerable body of graphic work and independent painted panels.37 He quickly gained a reputation among literary humanists. Christoph Scheurl, the Nuremberg humanist and jurist, praised him for painting ‘with wonderful speed’; Cranach’s tomb remembered him as pictor celerrimus.38 In his Elementa rhetorices of 1531, the erudite reformer Philipp Melanchthon, Luther’s deputy, invoked Cranach to illustrate the humble style; Dürer and Grünewald occupied the two higher ranks.39

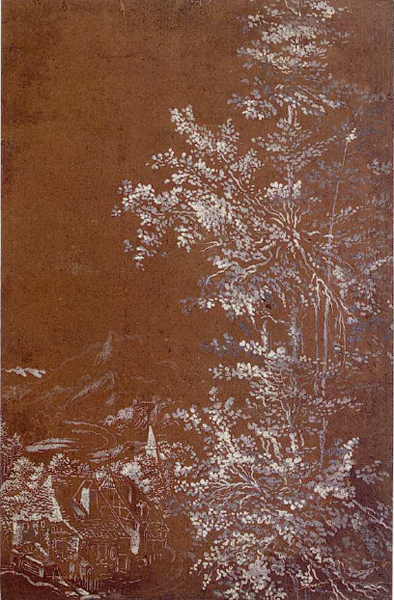

Cranach’s early drawings on coloured grounds – the John the Baptist in Lille of around 1503 (illus. 39)40 and the St Martin and the Beggar in Munich, monogrammed and dated 150441 – were among the first autonomous drawings in the history of Western art. They were drawn with pen and ink and finished with touches of opaque white pigment, on paper coated with chalky grounds, usually in earth tones. These drawings, neither reproductions of existing works nor preparatory studies for future works, were offered as works in their own right. Paper prepared with coloured ground was first used as a drawing support in Tuscan painting workshops of the fourteenth century.42 The ground provided a middle tone between the darker outlines and shading and the heightening in opaque white. The technique proved ideal for working out tonal values in life drawing or in direct preparation for painting. It flourished in Italy until the early sixteenth century, when it was replaced by chalk drawing. At this very moment, however, the German coloured-ground drawing broke out of the workshop. Partly because the ground masked the physical support of the drawing, partly because its triple tonality of ground, black pen and opaque white heightening simulated some of the effects of painting, the coloured-ground drawing stood more easily on its own than the ordinary pen drawing. The earliest dated and indisputably independent coloured-ground drawing is Bernhard Strigel’s Death and Amor of 1502.43 The idea was seized upon immediately by Cranach, and within the next years by Altdorfer, Huber, Baldung, and especially the Swiss artists Leu, Manuel Deutsch and Graf. By 1508 the independent coloured-ground drawing was so well established in Germany that it was in turn imitated by the chiaroscuro woodcut (see p. 288).

The coloured-ground drawing became one of the great theatres for personal style. The pen slid easily on the smooth coloured ground. The ground encouraged swifter outlines, broad, looping modelling strokes, even gratuitous flourishes of the pen. Rapid execution of the sort admired by the humanists became an aspect of personal style. Some of the drawings were no doubt executed within a matter of minutes, perhaps even under the eyes of the patron. The initials or monogram that appeared on nearly all coloured-ground drawings, finally, guaranteed the authenticity of those pen-strokes: the drawing was the product of an unrepeatable set of creative gestures and a particular moment in time.

In the drawing of John the Baptist, Cranach created a wilderness of opaque heightening coarsely brushed on a streaked brown ground. The subject-matter – the seated saint together with his attribute, the lamb – is outlined with black pen and self-contained. Nevertheless, the work is more like a print than a painting, for the setting is created out of the same substance as that of the figure. The white heightening serves several different functions at once. In the drapery it makes areas of lighter tone, even an effect of sheen on the cloth. On the Baptist’s fur tunic and in the wool of the lamb it describes individual curled hairs. Along the edge of the cliff above the saint’s head it traces a tense and quivering profile of rock. The background is described almost entirely with rude, white brushstrokes. In the distant mountain and in the tree at the right, white is outline, substance and tone all at once. This confusion of descriptive tasks was to become a central theme in Altdorfer’s work. Lines this versatile were eventually to detach themselves from their representational function.

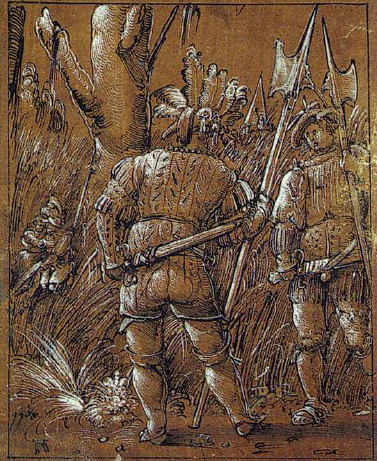

Altdorfer, following Cranach, began making autonomous drawings on coloured ground at the very start of his career. Altdorfer’s earliest known work is a pen drawing on white paper in Berlin, dated 1504 and unsigned, a comic Loving Couple (illus. 40).44 Echoes of Cranach’s woodcuts are found in the figure and especially the face of the youth, the rough drapery of the woman, the wild mood. But Cranach’s line was never so fine and tremulous. Cranach never had the patience to vary the length and intensity and density of his pen-strokes in the way in which they are varied here. The drawing proceeds more fundamentally from Dürer. Four drawings by Altdorfer on coloured ground are monogrammed and dated 1506, all depicting subjects outside the familiar territory of New Testament iconography: Samson and Delilah,45 Witches’ Sabbath,46 Pax and Minerva,47 and Two Lansquenets and a Couple.48 These are all finished works, as complete and as self-sufficient as prints. The Two Lansquenets in Copenhagen (illus. 41), on a red-brown ground, plants a pair of over-stuffed, plumed foot-soldiers before a wide band of rough pen slashes, a wall of grass. Like the other four drawings of 1506 – and unlike all but a very few later sheets – the drawing is framed by a black pen-line.49 Hanna Becker thought that the Copenhagen sheet was a copy because the border cuts off the arm and leg of a soldier.50 But a frame that cuts off a figure is also a more assertive and conspicuous frame. It enhances the effect that the scene has been fortuitously captured, a slice of real life. Hans Mielke, too, reads the borders as proof that the compositions were determined in advance and not spontaneously invented. Indeed, he believes that all of Altdorfer’s finished drawings were Reinzeichnungen, or fair copies: copies after himself, as it were. Mielke did prove that pupils made close copies of Altdorfer’s drawings in the shop, by showing that both the Samson and the Lion and its copy were drawn on paper cut from the same sheet.51 It is true that the appeal of these drawings was that they did not look copied or premeditated, but spontaneous. But spontaneity could be affected or imitated. Wolf Huber seems to have copied his own landscape drawings. Nevertheless, although we have copies by pupils and followers after drawings by Altdorfer, we have no pairs of drawings both by Altdorfer that would verify Mielke’s hypothesis. And, in fact, these drawings are generally far from ‘fair’: they are thick with overlappings, second thoughts, blunders. The black border was a way of asserting the finished quality of the drawing in these early years of the autonomous drawing; it imitated the border of woodcuts and engravings. Later it became unnecessary.

38 Lucas Cranach, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1504, oil on panel, 70.7 × 53. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

39 Lucas Cranach, St John the Baptist in the Wilderness, c. 1503, pen with white heightening on brown grounded paper, 23.5 × 17.7. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille.

Another pair of coloured-ground drawings by Altdorfer are monogrammed and dated 1508: the St Nicholas Calming the Storm at Oxford52 and the Wild Man in London (illus. 106). The Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane and the St Margaret, both in Berlin, are monogrammed and dated 1509.53 It is hard to overstate the significance of these signatures. More than anything else it was the monogram and the date, inscribed on small tablets or cut stones, that sealed off the autonomous drawing. There is no indubitably authentic signature or monogram on any German pen-drawing before Dürer.54 Most, and perhaps all, of the monograms on Schongauer’s drawings, for instance, were applied by later owners, among them Dürer himself.55 Dürer began initialling his own drawings before 1495. In 1497 he first used the nested monogram, D inside A, on a drawing, the Lute-playing Angel in Berlin.56 But most of the early drawings that Dürer signed merited initials only by virtue of their proximity to more formal media: some copied Italian engravings, others were painted on parchment like miniatures. Even Dürer did not simply begin by monogramming ordinary pen-drawings, although he would do so frequently later on.57

Dürer was the only important artist of his century or even for several centuries who regularly signed his drawings. He was more of a loner than a pioneer. The impact of his innovation was short-lived and local, but intense. Every German artist of the sixteenth century who monogrammed a pen-drawing was directly or indirectly following Dürer’s lead. Altdorfer’s monogram itself, with its A nested within a larger A, directly emulated Dürer’s. The initials on fifteenth-century engravings, by contrast, were never nested or entwined. Dürer’s pupils and direct associates – Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Kulmbach, Hans Schäufelein, Hans Springinklee, Hans Leu the younger – all entwined or nested their initials on drawings.58 But there is no proof that Altdorfer had ever seen a drawing by Dürer before 1506, signed or unsigned. Altdorfer may actually have imitated not the monograms on Dürer’s drawings but those on his engravings, as well as the monograms on his own engravings, thus negotiating the transition from the reproductive medium to the drawing all on his own. Indeed, when Altdorfer framed his monograms and dates in little boxes, as he did in three of the 1506 drawings (all but the Copenhagen Lansquenets), he was certainly imitating Dürer’s prints and not his drawings. There were virtually no precedents for framed or ‘motivated’ dates or monograms on drawings. In fifteenth-century German engravings, initials and dates appeared anywhere on the surface; Schongauer was the first to place his monogram consistently at the lower centre. Dürer began framing the monogram only after the turn of the century. And, indeed, Altdorfer never again dated or monogrammed a pen-drawing in this way.59

40 Albrecht Altdorfer, Loving Couple, 1504, pen on paper, 28.3 × 20.5. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. |

|

41 Albrecht Altdorfer, Two Lansquenets and a Couple, 1508, pen and white heightening on red-brown grounded paper, 17.6 × 13.7. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

Under the aegis of the signature, such pictures began to distance themselves from other pictures, and from the functions that most pictures ordinarily fulfilled. The trace of an absent artist transformed the merely physically independent painting or drawing into a ‘work’. Dürer actually wrote explicitly about the manifestation of the artist’s personality in the work, in the passage from his treatise on proportions, the so-called ‘Aesthetic Excursus’, quoted earlier. First, Dürer describes imagination or inventiveness as a ‘power’ granted by God to the great artist. Then he admits that this artist’s essential ambition is to reveal himself in his works, within the customary boundaries of function, iconography and decorum: ‘He that desires to make himself seen in his art must display the best he can, so far as it is suitable for this work.’ Power reveals itself, miraculously, in the most negligible vestige of the hand’s movement.

An artist of understanding and experience can show more of his great power and art in crude and rustic things, and this in works of small size, than many another in his great work. Powerful artists alone will understand that in this strange saying I speak truth. For this reason a man may often draw something with his pen on a half-sheet of paper in one day or cut it with his little iron on a block of wood, and it shall be fuller of art and better than another’s great work whereon he has spent a whole year’s careful labor, and this gift is wonderful.60

The value of the work is independent of the quantity of labour lying behind it. The trace of the artist’s divine gift permits the frame to close off the picture and pronounce it finished. The clean cut of this external frame was in turn the prerequisite for any really adventurous tinkering with the internal structure of the narrative picture.

Subject and setting

Altdorfer’s Dead Pyramus in Berlin is a good example of a narratological experiment made possible by this new enfranchisement of the drawing. The sheet is unsigned – or has lost its signature – but must date from c. 1510 (illus. 42, 43).61 It was executed in black ink and opaque white heightening on paper coated with a deep blue ground. This drawing stages a direct conflict between setting and subject-matter. The scene opens on a still forest space and a scattering of brittle, fleshless trees, etiolated by an unseen moon. At the foot of the tallest tree, at the mouth of an arched tunnel, on stony ground rimmed with underbrush, lies a man in the costume of a soldier. This figure is not easily identified. If the drawing is still a narrative, then it has become antagonistic to its own pretext. But the figure does resemble figures from other pictures, in particular the dead Pyramus in a woodcut by Altdorfer.62 The story of the lovers Pyramus and Thisbe was told by Ovid in book IV of Metamorphoses; today it is best remembered from the version clownishly performed in Act V of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Frustrated by their elders, the couple planned a nocturnal tryst outside the walls of Babylon, at the tomb of Ninus, near a mulberry tree and a spring. Thisbe, arriving early, encountered a lioness and fled, leaving behind her veil, which the lioness tore and marked with bloody jaws. Pyramus found the veil and, assuming the worst, killed himself with his sword; Thisbe then returned to the scene, discovered the corpse, and also killed herself. The story was absorbed into profane iconography as early as the twelfth century. Most recently, in 1505, it had been engraved by the Bolognese Marcantonio Raimondi (illus. 213). Still other pictures encourage the identification of the figure by showing that Pyramus sometimes wears the slit tunic of a lansquenet and that the arched cave can stand as the tomb.63 But where are the spring, the lion and, above all, Thisbe? (Is she cowering behind one of the trees to the left of the tomb,64 or is the beholder of the picture cast as Thisbe?) The best clue to the identity of the recumbent figure is the slender dagger fixed in his chest.

The ekphrasis or description of this picture was impeded by the supine lansquenet. The story he belongs to has been torn apart. One is tempted instead to remain in the upper three-quarters of the picture and continue describing the firs, their bark and branches and thinning foliage, the pendulous mosses, the fragment of remote mountain profile, and even the sky between and behind the trees. Setting does not merely fail to contribute to subject-matter, but also pulls us away from it. On the other hand, the very obscurity of setting’s commentary on subject-matter can become another sort of contribution. The arch appeal of this drawing consists precisely in its iconographic frugality. By omitting components of an established narrative, it rejuvenates that narrative. The drawing places the beholder between two suicides, the one attested to by the corpse and the other merely anticipated. The beholder is forced to recognize the story from the inside out, and is made to wonder, perhaps for the first time: how impetuous was Pyramus’ suicide? how long did he wait? where is Thisbe and when will she return? The drawing has delivered the story back into the hands of the beholder. It has surrendered control over the temporal structure of the story; now the story stretches forward and backward in the beholder’s mind. The last indications of narrative time within the drawing are the raised knee, implying a fairly recent fall to earth, and the radiating ringlets of hair, perhaps a survival from Marcantonio’s version, recapitulating the violence of passion. All the rest have vanished. Like any narrative image, this drawing represents a static moment, a configuration of bodies in space, in such a way that the immediate temporal antecedents and consequences of that moment are called to mind. The static image is physically incapable of reproducing continuous time; instead it demands that the beholder extend the action forward and backward in the mind. The image dramatizes the contrast between the intense fullness of the single described moment and the emptiness of all the ghostly and imagined moments before and after. An image is more disorderly and gratuitously informative than a written text can ever be. The painter or draughtsman, unlike the writer, is virtually obliged to include more information than the subject requires. For the painter has to fill a frame; the writer simply stops when he is finished, and the edge of his text becomes his frame. Thus pictorial narrative turns a necessity into a virtue. The subject-matter of a narrative image is always partially absent: the beholder’s attention is always displaced toward something adjacent to the represented moment. Altdorfer’s drawing carries this displacement to an extreme.

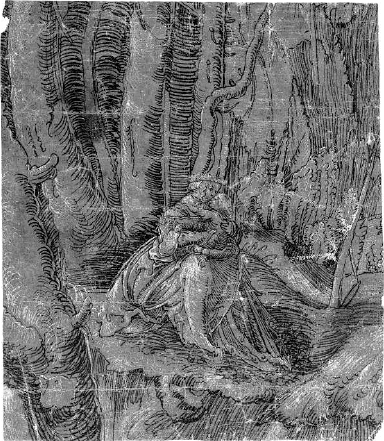

But this rejuvenation of narrative is ultimately hazardous to narrative. The laconic narrative lives on the fringes of intelligibility. It is in danger of falling entirely silent, as it has in a strange drawing by Altdorfer in Frankfurt where an anonymous prostrate man, sharply foreshortened, sprawls (again with raised knee) beneath a monstrous cluster of fir-trunks (illus. 44).65 Moreover, setting begins to generate its own independent meanings, probably not narrative at all, possibly quite inadvertent. Setting, which has been described and not ‘told’ by the draughtsman, which is so susceptible to and even inviting of the beholder’s secondary description, installs alternative temporal structures. Altdorfer’s Dead Pyramus precipitates temporality down to an elemental state, to the quivering of foliage and to the imperceptible pace of vegetative growth. Setting betrays subject-matter by broaching themes in its own right. Description in this drawing cannot simply be classified as either functional or decorative.

42 Albrecht Altdorfer, Dead Pyramus, c. 1510, pen and white heightening on blue grounded paper, 21.3 × 15.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

The internal boundary that the naming of subject-matter drew between setting and subject turns out to be permeable, even unstable. The narratologist Gérard Genette has shown how verbal narration enjoys a temporal coincidence with its object that verbal description cannot share: narration itself mimics the temporal succession of events, whereas description must struggle to account for static or spatial properties in a temporal medium.66 In the image, which offers a spatial analogy to phenomenal reality, this imbalance is reversed. The pictorial historia is constantly drifting back toward description, toward a report on the physical attributes of things in the world. The text, at least, has the option of saying either ‘a man stabbed himself and fell to the ground’, or ‘a man lies on the ground with a dagger in his chest’. The former statement narrates; the latter describes a state and only implies an event. The image can only make the latter sort of statement. It can only represent movement by showing a ‘still’, as it were, and hoping that the beholder will extrapolate backward and forward. Description can only offer circumstantial evidence; indeed it can only show (evidentia means ‘showing clearly’) and never tell. It turns out that everything in the picture, even the corpse, is a description. Is narrative ever embodied in an image? The real subject-matter of narrative is not the human figure, but the event. Narrative describes events; it accounts for change through time. But because only verbs can accomplish this with authority, the image is reduced to describing the premises or the results of events. In the image, description is perpetually encroaching on the story. It overwhelms even the human figures, until everything has become setting and until the story is disembodied. Description brings to bear on the image a levelling power: it disassembles the hierarchy between action and stasis, eventually social hierarchies, also perhaps the hierarchy of the historical and the natural, or the animal and the vegetal.67 And this is what the Dead Pyramus represents: the body is in the process of being absorbed back into the forest, reclaimed by coils of calligraphy. Line here is the spokesman for the organic, for process. The forest advances on the remains of narrative.

44 Albrecht Altdorfer, Dead Man, c. 1515, pen and white heightening on olive-brown and orange grounded paper, 17.8 × 14.2. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt.

Altdorfer was exploiting an intrinsic ambiguity of setting. Setting, the zone of accessories or parerga enveloping the movement at the centre, was the zone within the picture most independent of prescription and convention. The morphology of the human figure was severely constrained by workshop tradition, by the knowledge and expectations of beholders, and by fundamental principles of anatomical verisimilitude. Setting, on the other hand, could unfold and diversify in any direction without necessarily foiling the purpose of the picture. Setting was the least resistant part of the picture. Any number of conceivable settings could effectively host a given event. An outdoor setting could accumulate geographical or meteorological attributes, or pockets of authentic topographical data. A tree or a mountain could assume new contours almost ad libitum and still be recognized as a tree or a mountain. Dürer had demonstrated this already in his woodcuts and engravings of the 1490s.

45 Albrecht Altdorfer, Satyr Family, 1507, oil on panel, 23 × 20.5. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

This is the process that led Altdorfer to the independent landscape. The analysis of the process has taken the Dead Pyramus as a starting point in order to unearth the roots of landscape within the narrative image. The descriptive line tends to dissipate solid bodies. Substance in the Dead Pyramus is at the mercy of Altdorfer’s rampant and ambitious pen. The protagonist of the drawing is caught in a web of line; he bleeds into the earth, overwhelmed by the canopy of calligraphy closing in over the space where he once stood. He is drained of substance, becomes one with the dark blue ground. Line erodes matter; it etches matter away. The eye, instead of lighting on and gauging bodies, can actually leaf through the layers of overgrown penmanship: first the white scribbles and the long dripping flourishes, then the black scribbles, then the shading in black and white, finally the tenuous outlines, only to arrive at nothing, a blank ground, pure colour. And when line contests the presence of physical substance, it also contests subject-matter. It ridicules the illusion that subject-matter, and certain kinds of meaning, inhabit measurable bodies. Instead, it leaves those meanings in the custody of an artist. When Dürer rebuked the artist who departs from nature, imagining vainly that he will find better on his own (see p. 14), he may have been thinking precisely of Altdorfer.

46 Albrecht Altdorfer, Wild Family, c. 1510, pen and white heightening on grey-brown grounded paper, 19.3 × 14. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The settings of many of Altdorfer’s early drawings are contentious in just this way. Their subject-matters belong to the repertory of the quasi-narrative hagiographical or profane print. But they approach these subjects from an oblique angle. Their freshness and appeal is grounded in the strange sense of humour, the ad hoc iconoclasm, of the draughtsman. Altdorfer twists every theme into burlesque. He lets a layer of unruly new growth spread over the old subjects. Altdorfer’s predecessor here was the Housebook Master, the late-fifteenth-century Rhenish engraver and painter who had cultivated a similarly dishevelled and disrespectful tone. In some of Altdorfer’s drawings, like the Paris Witches’ Sabbath (illus. 219) and the Oxford St Nicholas Calming the Storm, the turmoil and indiscipline of the setting are built into the subject-matter. More profoundly unbalanced are those drawings where subject-matter seems almost arbitrarily beleaguered by its surroundings. The Two Lansquenets and a Couple in Copenhagen (illus. 41), for instance, offered a reverse perspective on the loving couple familiar from fifteenth-century engravings. Here the couple vanishes into an ocean of grass, while the bulky comrades in the foreground, one turning a bulging back to the beholder, spy on the lovers, stand guard, or wait their turn with the woman. The Dead Pyramus belongs to this latter category of drawing.

Altdorfer was allergic to bombast and heroic equipoise. In these drawings he intrudes clumsily and disingenuously on narrative by rattling the hierarchy of subject and attributes, or by inflating attributes into false subjects or decoys. Altdorfer followed both Dürer and Cranach, for example, in exploiting the tree. The tree is the ideal parodic double of the human subject. It is anthropomorphic in structure, but elastic in size; it is naturally immobile, and so mocks the artificial immobility of the depicted human figure; it can appear almost anywhere without special iconographic justification and is thus largely exempt from conventions of decorum or narrative verisimilitude. There are many examples of the exempted tree among Altdorfer’s drawings on coloured ground. In a drawing in Braunschweig, another excellent copy, the Virgin and Child are framed entirely by trees (illus. 47).68 The drawing hyperbolizes a familiar iconography, the Madonna and Child in the open air: part Madonna of Humility, part excerpt from the Flight into Egypt. They are framed by trees, but also by a curtain of modelling lines, literally hundreds of blunt parallel strokes in black and feathery white coils, a foil so dense that it almost loses its representational value.

47 After Albrecht Altdorfer, Madonna and Child in a Forest, c. 151o(?), pen and white heightening on olive-brown and orange grounded paper, 17 × 14.7. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig.

48 Albrecht Altdorfer, St Francis, 1507, oil on panel, 23.5 × 20.5. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

49 Albrecht Altdorfer, St Jerome, 1507, oil on panel, 23.5 × 20.4. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

Once the tree is perceived as an element of pictorial structure, architecture, too, can come to look like mere setting, with its ties to iconography unravelling. In the panels of the St Florian altarpiece, landscape and architecture perform comparable structural functions. In the Arrest of Christ (illus. 50) Altdorfer painted a forest that encloses the actors like a constructed interior;69 the interior architecture of the Trial of St Sebastian (illus. 51), meanwhile, arches and twists like a forest.70 Architecture also enters easily into a competitive relationship with subject-matter. Italian painters had for decades been constructing cities and palaces at the expense of narrative, and not only in model drawings like those in Jacopo Bellini’s sketchbook. Later on, Altdorfer made this rivalry a theme of some of his most ambitious panel paintings: the Birth of the Virgin (illus. 52), with its enormous celebratory angelic chain weaving hazardously among the pillars, the unlikeliest possible setting for a birth;71 and the Susanna and the Elders (illus. 54) of 1526, with a triumphant and exotic palace that looks like it is still growing, upward and outward.72

50 Albrecht Altdorfer, Arrest of Christ, from the St Sebastian altarpiece, c. 1515, oil on panel, 129.5 × 97. Augustiner-Chorherrenstift, St Florian, Austria.

51 Albrecht Altdorfer, Trial of St Sebastian, from the St Sebastian altarpiece, c. 1515, oil on panel, 128 × 93.7. Augustiner-Chorherrenstift, St Florian, Austria.

52 Albrecht Altdorfer, Birth of the Virgin, c. 1520, oil on panel, 140.7 × 130. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. |

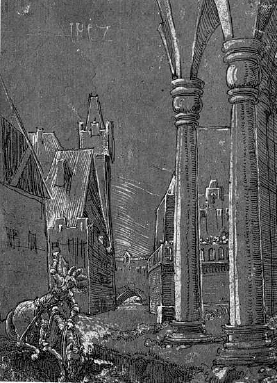

What would an independent landscape look like if it were made out of architecture? In a drawing of the Death of Marcus Curtius dated 1512 (illus. 55), the hero bears the same structural relationship to the city that Pyramus bore to the forest.73 The drawing was inspired by a Cranach woodcut of c. 1507, which itself followed a small northern Italian bronze relief, where a tempietto and a row of half-clothed figures stood for the Roman forum and the populace, the site of the hero’s self-sacrifice and its witnesses. In Altdorfer’s drawing, the tempietto has become a pair of massive columns. Rome is now a deserted Gothic nightmare in imperial proportions. Marcus Curtius is about to drop out of the picture altogether. After such a disappearance, the picture would be pure urban setting. Within the rhetorical analysis carried out here, this setting would be indistinguishable from a woodland, pastoral or marine setting. If ‘landscape’ is the disappearance of subject-matter, then such a picture would be a landscape.

That urban landscape does exist, and it is one of the most curious works in Altdorfer’s œuvre. A drawing on a dark brick-red ground in the Teylers Museum in Haarlem represents nothing but a church on a city street and a handful of random passers-by (illus. 56).74 Just as for the empty landscape, there are precedents for the street-scene in marginal spaces. One of the bas-de-page calendar scenes in the Turin Hours, Flemish work of the mid-fifteenth century, represents a low frieze of urban house-fronts and passers-by, both smart and shabby.75 The margins of the page offered a safe house for the subject-less vignette. But Altdorfer’s Teylers drawing shares its technique, its format, and its degree of finish with ordinary single-scene narratives. The drawing is dated 1520 and is falsely inscribed with Dürer’s monogram. Beneath that monogram are traces of an Altdorfer monogram. There are really no barriers to accepting the drawing as autograph, even if the date is correct. Since Altdorfer had by that time largely given up drawing on coloured ground, there are no proximate standards by which we can judge the style, no morphological niche in which to insert it. Nevertheless, there is great refinement and the aura of exploration and novelty in the speckled glow of the church walls, in the smudges of white at the horizon, in the flared and dramatic contour lines in black. The drawing has been associated with the plans to build a new chapel for the miraculous image of the Schöne Maria of Regensburg, the cynosure of the pilgrimage of 1519–21. But it would make no sense to bury an architectural projection in this darkest of coloured grounds or to surround it with aimless pedestrians in archaic robes.76 There is no fundamental difference between such a drawing and a picture of an empty forest. The independent landscape is what remains not when ‘culture’ has been subtracted from the scene of narrative – leaving ‘nature’ behind – but when subject-matter is subtracted.

53 Albrecht Altdorfer, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1510, oil on panel, 57 × 38. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

54 Albrecht Altdorfer, Susanna and the Elders, 1526, oil on panel, 74.8 × 61.2. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

55 Albrecht Altdorfer, Marcus Curtius, 1512, pen and white heightening on olive-green grounded paper, 19.5 × 14.4. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig. |

Of course it is madness to read drawings in this way. The forest enveloping the Braunschweig Virgin and Child is no mere pretext for penmanship. The forest powerfully inflects subject-matter. It shelters the holy refugees from a hostile pagan culture; it links them to a pristine and pre-ecclesiastical cult. Marcus Curtius will never really disappear from the city. The Teylers street-scene must have had a meaning. And yet there is a place for the perversely anti-iconographic reading. Such a reading serves a heuristic purpose: one needs to ignore the referential workings of the image, provisionally, in order to penetrate to a level of pictorial structure that underlies reference and makes reference possible. Such an analysis – like the rhetorical analysis of a text – can reveal affiliations and distinctions among images that were otherwise invisible. More important, the structural analysis opens up the possibility of a historical exegesis of the work. It makes it conceivable to write about images and about other aspects of culture in com-mensurate terms. Not before the analysis arrives at the level of structure will it have a chance of improving upon the approximations of ‘contextual’ art history.

56 Albrecht Altdorfer, A Church on a City Street, 1520, pen and white heightening on dark brick-red grounded paper, 17 × 14.7. Teylers Museum, Haarlem. |

|

It is not obvious that such a mode of reading is an anachronistic imposition upon the historical material. Circumstantial and textual evidence alike suggests that beholders were capable of looking through subject-matter long before the establishment of an art-critical discourse. Assignation of value and discriminations made among works and artists were largely governed by judgements about how images worked, not what they said. To read a forest as a pattern of pen strokes, in other words, is not to break with a tradition of interpretation, but rather to rejoin that tradition.

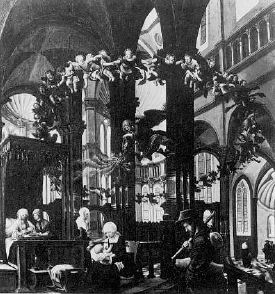

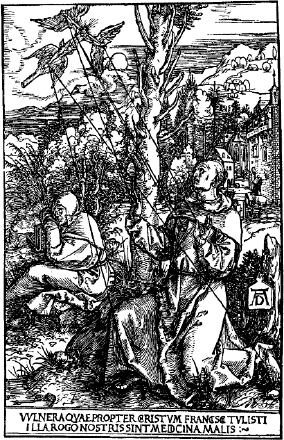

In Altdorfer’s time, the most conspicuous platform for structural experiments was the portable painted panel. The panel, the descendant of the ancient icon, was in these very years overtaking the manuscript illumination as the format par excellence of the private devotional image. Independent panels commonly showed figures and scenes extracted from familiar narrative sequences, sometimes incorporating dramatic references to the iconic roots of the format. The painted panel became a basic calling-card of the ambitious artist and a much favoured collector’s item. Altdorfer’s immediate models were again Dürer and Cranach. His earliest dated paintings were independent panels: the Nativity in Bremen, the Satyr Family in Berlin, and the St Jerome and St Francis in Berlin, all of 1507.77 The three in Berlin at least were certainly meant for domestic spaces; they are already ‘cabinet’ pictures of some sort.

Altdorfer signed all four of the 1507 panels with his monogram. The largest is the Nativity in Bremen, measuring 42 × 32 centimetres, or a few centimetres larger than the woodcuts of Dürer’s Apocalypse.78 The other three are much smaller. The Satyr Family (illus. 45), only 23 × 20.5 centimetres,79 tells an unintelligible story related to a drawing of a Wild Family (illus. 46) in Vienna.80 In the panel, Altdorfer lets the material slide toward burlesque. He refuses to maintain a decorous tone, rejecting both Dürer’s brimming poise in his engravings of Hercules at the Crossroads (B.73) and the Satyr Family (B.69, illus. 99), and the still seriousness of Jacopo de’ Barbari in his own Satyr Family engraving.81 Altdorfer’s loutish satyr cocks an eyebrow and reaches for his club; his mate restrains him with one hand as she hoists their child with the other. The exchange between the nude man and the alarmed woman in red, in the background, is incomprehensible. The difficulty in reading the narrative is inseparable from the incompleteness and impertinence of the setting: coarse, sandy earth and deep green foliage, topped with gleaming highlights but with few transitional tones in between, all in the rude tonality of Cranach’s early paintings. The flailing trees and the cliff impend over the wild family and fill two-thirds of the picture. The nineteenth-century art historian G. F. Waagen saw this painting in the Kränner collection in Regensburg. As if in answer to Schlegel’s question about the Battle of Alexander, he simply described it as an example of ‘how early this painter cultivated landscape as a genre its own right’. Waagen dismissed the satyr family itself as mere ‘staffage’, ‘as tasteless in invention as it is weak in drawing’.82

57 Albrecht Dürer, St Francis, c. 1500–05, wood-cut, 21.8 × 14.5. British Museum, London. |

|

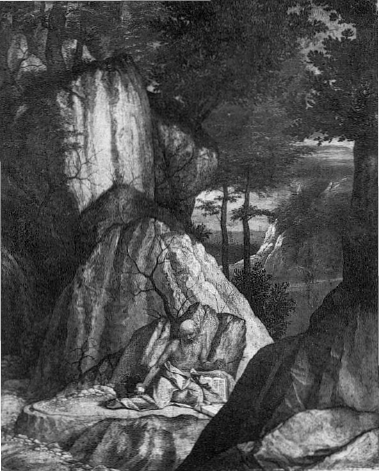

Identical in size to the Satyr Family are the pair of panels in Berlin representing St Francis and St Jerome (illus. 48, 49).83 They may have been pendants, although surely not a hinged diptych, for Altdorfer would not have monogrammed and dated both panels. The St Francis is hardly larger than its model, a woodcut by Dürer (illus. 57).84 Altdorfer has extended the composition to the sides, added a foreground tree, and pushed Brother Leo to a distant middle-ground. He preserves the posture of Francis, his cocked, oblique skull, and his gaping mouth. Perhaps the St Jerome reproduces, with comparable fidelity, a lost woodcut.85 Both pictures obey a tighter discipline than the coloured-ground drawings. Trees grow straight and refrain from anthropomorphic behaviour. These are sincere and stolid compositions, remote in mood from the affable, tousled, mock-magic Satyr Family. They are built of simple elements (trees at the left edges, middle-ground masses at the right) and animated by long, clean diagonals of gaze (and in the St Francis, of drawn lines as well). There is information everywhere on these surfaces, far more information than, for example, in Dürer’s woodcut. Altdorfer has thickened Dürer’s woodcut landscape with paint. Paint twists around a tree-trunk, drips from the end of a branch, piles up in bright flecks on the outer surface of a sombre deciduous crown, frosts a wild flower or a weed, fills the last hole of a composition with a two-tone vista of silky mountains. Paint can glue the elements of a picture together with colour. This had not happened in Cranach’s paintings or in Altdorfer’s Satyr Family. The two hagiographical paintings move entirely within a range of green and gold.

58 Lorenzo Lotto, St Jerome in the Wilderness, 1506, oil on panel, 48 × 40. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

The St Francis and the St Jerome are the overgrown ruins of devotional images. The aura of the human figures has been dispelled by the vegetation. Altdorfer’s panels are exact contemporaries of Lorenzo Lotto’s St Jerome in the Wilderness (illus. 58) in Paris.86 Lotto’s hermit, seated on a natural platform like the Madonna in Altdorfer’s Braunschweig drawing, is inert, overwhelmed by the rock faces massing behind him. Bernard Berenson wondered whether Lotto’s panel had not once been attached to a humanist portrait, just like the Allegory and the Dream. Such unbalanced pictures stand at the threshold of the independent landscape.

There are few documentary footholds for Altdorfer’s biography in these early years. In 1509 he was paid by the city for a painted panel in the choir of the cathedral. By 1513 he was able to buy a house in the Oberer Bachgasse; this house still stands today. His financial anchor was the commission for the massive winged altar at St Florian, which he finished by 1518 but may have begun as early as 1509 or 1510. In 1510 he made a donation of one of his own small paintings, presumably to a local church or chapel. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (illus. 53) in Berlin is piously inscribed, on a panel propped against the base of the fountain, ‘Albrecht Altdorfer, painter of Regensburg, dedicates this gift to you, divine Mary, with faithful heart, towards his own salvation’.87 Christian angels swarm among their stone counterparts, the pagan victories on the column supporting the idol. The fountain itself is inspired by Mantegnesque prints. One of the stone children, apparently converted, brandishes a cross. The basin crawls with detail but is unstable, as if the weight of the Christ Child is about to topple it. The Virgin, who somehow has found a chair, accepts cherries from Joseph. Mountains, coast, decaying roofs and isolated ruins are compressed into an airless compost. The panel is a little too high, as if the towering idol has imposed an unreasonable standard.

Prosperous merchants were not yet extinct in Regensburg. In 1508 Johannes Mosauer of Regensburg rented the largest vault in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice, freshly decked with Giorgione’s baffling frescoes. The city rented a vault as well.88 Altdorfer, too, was looking far afield. His encounters with Italian prints are directly legible in his early works. The figure of Pax in the coloured-ground drawing in Berlin, for example, is based on one of the Muses in Mantegna’s Louvre Parnassus, transmitted probably by an engraving of Zoan Andrea. The fountain in the Rest on the Flight also derives from northern Italian engravings.89 Altdorfer established contact with the humanists surrounding Maximilian. Joseph Grünpeck, an astrologer, dramatist and Imperial secretary, opened a Poetenschule, or Latin school, in Regensburg in 1505, and resided in the city periodically until at least 1511. At some point between 1508 and 1515 Grünpeck composed for the benefit of the Emperor’s grandson, the future Charles V, a chronicle of the lives of Maximilian and his father, the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani. The manuscript was illustrated with coloured pen-drawings, possibly as models for woodcuts in a planned publication. These illustrations have only very recently – and convincingly – been reattributed to Altdorfer.90 In 1512 Maximilian gave a house in Regensburg to his court historian Johann Stabius, who designed the iconographic programme for the imaginary Triumphal Procession, and hired Altdorfer to illustrate it. Through Stabius, Altdorfer could easily have extended his contacts with humanists and with sophisticated artists like Dürer and Burgkmair, if he did not enjoy such contacts already. It was here, among the antiquaries and literary humanists, who had studied in Italy or looked to Italy for guidance, who were familiar with pagan stories and medieval romances alike, who all knew Dürer and his work, that one seeks the original audience for Altdorfer’s singular prints, drawings and panel paintings.

The landscape study

The concomitant of the frame is composition. A picture is ‘composed’ when its contents acknowledge, through their disposition, the edges of the surface they occupy. Such a picture will have trouble upholding the pretence of being a mere arbitrary excerpt from a plane of infinite extension. It becomes a visual ‘field’ unified by the presence of a fixed beholder. This is a picture that – true to Hegel’s normative diagnosis of the ‘ac-commodating’ modern work of art – manifestly exists for its beholders, ‘for us’.91 The literal frame – a drawn or painted border, a wooden brace – simply confirms a state of affairs that the surface data have already conceded.

What were the components of a landscape composition? Horizontal bands of earth, water and sky inside a circle, a shorthand for the view obtained from an ordinary earthbound standpoint, once sufficed to represent the entire sublunary realm. We saw an example in the sarcophagus of Darius painted by Apelles, in the fifteenth-century Dutch manuscript (illus. 30). Later, the standard repertory of terrestrial features expanded. An inscription on the tomb of the French miniaturist Simon Marmion reveals that the painter’s genius was legible as much in his accessories as in his figures. The list reads in part like a description of a background landscape: ‘Sky, sun, fire, air, ocean, visible earth, metals, beasts, red, brown, and green draperies, woods, wheat, fields, meadows; in short, I represented by my art all sensible things.’92 The landscape in a picture by Simon Marmion served, like the inscription itself, as a catalogue of the painter’s mimetic talents.

How was such a catalogue consolidated on the picture surface? Accessories, ‘sensible things’ strewn randomly across the plane, lay vulnerable to the contempt of classicists such as Michelangelo. A full-page woodcut in a Book of Hours printed in Paris in 1505 scatters Marian emblems and inscriptions around the figure of the Virgin (illus. 59).93 Christian exegesis of the Song of Songs read the garden, the olive tree, the fountain, the portal, the city and the fortified castle as emblems of the Virgin. These interpretations penetrated the hymnal literature in the High Middle Ages and were common coin by the fifteenth century. This woodcut page is pure composition: the emblems float in equilibrium, evenly distributed, exclusively for ‘our’ benefit. The emblems do not reproduce any conceivable disposition of objects in the physical world. Eugenio Battisti has shown how Venetian devotional panels naturalized such symbols by embedding them in a background landscape.94 In Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow (illus. 60) in London, for example, the Marian symbols are plausibly planted in foreshortened terrain.95 They are disguised as random objects embraced by the painter’s vision, the objects that simply happened to be found behind this open-air Madonna and Child. Nevertheless, they are evenly distributed on the picture plane and perfectly legible, and indeed are no less perspicuously presented than the floating symbols on the printed page. The Venetian background is both setting and composition: spatial illusion that fails to disrupt planar organization.

This synthesis of two-dimensional pattern and three-dimensional illusion, grounded in terrain or floor, is fundamental to the post-Renaissance idea of a pictorial work. Disconnected botanical studies, like Dürer’s watercolour blossoms or the beautiful and only recently identified sheet of peonies by Martin Schongauer, play no part in the history of the pictorial landscape.96

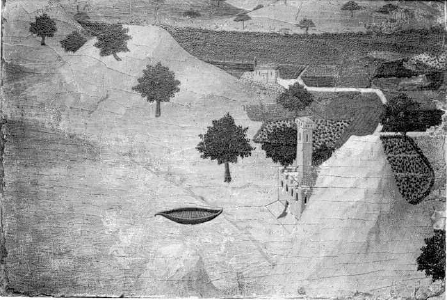

Bellini’s background was a picture within a picture, rimmed by an invisible internal frame. In principle, the coherent background landscape ought to pass for an independent composition even after it is extracted from its matrix. This actually happened with a famous pair of landscapes in Siena, a view of a city and a view of a castle by a sea (illus. 61).97 These panels are confusing because they are composed like pictures. Landscape backgrounds, no less than complete pictures, were subjected to conventions of symmetry and asymmetry, balance and imbalance. The arc of the coast, for example, linking one edge of the picture to a perpendicular edge, was a device that would be picked up by the early topographical draughtsmen as well, to help mould their reports into pictures. The Sienese panels are not in fact fourteenth-century independent landscapes, as many have argued, or even topographical descriptions. They are, instead, fragments cut out of a larger, lost composition, probably fifteenth-century.98 Painters copied modular background landscapes like these and repeated them from one picture to another. They could count on beholders to see the invisible frame. Painters saw them: the Italian eye quickly isolated the Flemish landscape from its context (see illus. 25, 26). When the two frames – the interior frame around the view within the composition and the exterior frame around the physically independent panel or drawing – were finally resolved into one, the result was an independent landscape.

The obvious frame for a landscape within a composition was the window. Windows frequently opened onto composed views both in the backgrounds of portraits, such as Dürer’s Madrid Self-portrait of 1498,99 and in narratives, such as Giovanni Bellini’s Annunciation in the Accademia, a pair of canvases that once served as organ wings in Santa Maria dei Miracoli.100 In one curious instance a painted view was inserted into a sculpted altarpiece. On the rear wall – a real wooden panel – behind the Annunciation in a late fifteenth-century altarpiece in Meersburg on Lake Constance, a painted landscape masquerades as a window (illus. 62).101 The painter has, in effect, painted an independent landscape that is legitimated only by its participation in the fiction of the carved room.

59 French master, Emblems of the Virgin, woodcut, from a Book of Hours, Paris, 1505. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. |

|

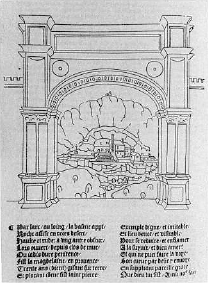

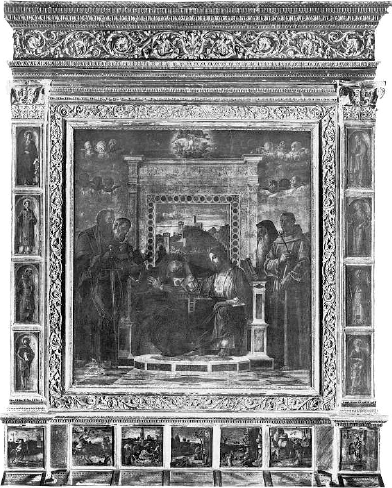

Windows were easy to justify or motivate within a picture; most rooms had them. The most ingenious embedded landscapes were those framed not simply by a window but, more slyly, by a fortuitous conjunction of architectural or geological elements. In an antiquarian engraving of c. 1507 of the equestrian monument of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, Nicoletto da Modena simply punched a rectangular hole in a rear wall and filled it with a cliff landscape (illus. 63).102 Jean Pélerin-Viator, the learned cleric of Toul and the first Northern theorist of perspective, introduced a woodcut view of Sainte-Baume in Provence, a pilgrimage site, in the second edition of his treatise De artificiali perspectiva of 1509 (illus. 64).103 He framed and rhymed the hill with an Italianate triumphal arch that had been printed alone and empty in the first edition. In Giovanni Bellini’s St Jerome in Washington, dated 1505, a natural stone bridge unevenly frames a landscape.104 But Bellini had constructed the finest of all landscape frames already in his Pesaro altarpiece of the early 1470s (illus. 65).105 The square aperture in the back of the throne, behind the heads of Christ and the crowned Virgin, frames a view onto a fortified city. That landscape would also be visible if the throne were absent altogether; but then it would be mere background, as in Bellini’s Madonna of the Meadow. The device of the Pesaro altarpiece is more radical than a mere window, for the throne does not need the aperture to function as a throne. The throne is perversely transformed into a picture frame that actually resembles the real frame of the altarpiece.106

60 Giovanni Bellini, Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1505, oil on canvas (transferred from panel), 67.3 × 86.4. National Gallery, London.

61 Sienese master, Landscape Fragment, 15th century, tempera on panel, 22 × 33. Pinacoteca, Siena.

62 German masters, Annunciation altar with landscape painted on inside wall of shrine, c. 1480s (sculpture), c. 1500–10 (painting). Unterstadtkapelle, Meersburg am Bodensee. |

Fifteenth-century workshops commonly kept stocks of drawings of standard landscapes to be inserted into the backgrounds of narrative paintings. In fact, Bellini reused the framed landscape of the Pesaro altar in his Madonna Barbarigo of 1488, now in San Pietro Martire in Murano. Another landscape with a fortified hill and buildings in brush and white heightening on coloured paper, tattered and worn after long use, was reincarnated in the backgrounds of paintings by Bellini, Bartolommeo Veneto and others.107 Both Pisanello and Jacopo Bellini, Giovanni’s father, had compiled modelbooks with samples of landscapes.108

Early Netherlandish landscape backgrounds were also assembled from a few simple elements. But no shop drawings survive. A late-fifteenth-century German scribe called Stephan, from Urach in the Swabian Jura, copied what looks like a standard cliff pattern from a Netherlandish painting or miniature into his own modelbook (illus. 66).109 Stephan’s book is an anthology of amateurish sketches and copies, mostly of ornamental motifs, from French, Burgundian and Italian sources, probably for eventual use in manuscript illuminations. The cliffs on the right of this page, bearded, tree-topped, menacing, were staples in Netherlandish manuscripts and panels. The towering cliff became one of the chief compositional schemas of the early empty landscapes in manuscripts – the illustration to the Swabian Chronicle, for example (illus. 18, 19), or the travel descriptions in Schedel’s manuscript.

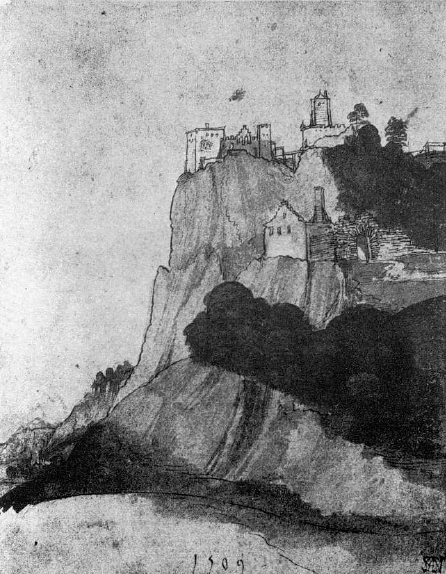

Cliffs became a German predilection. Sheer cliffs, often topped off with castles, commonly filled the windows in the backgrounds of narratives and, increasingly, portraits.110 In a drawing in Erlangen, a brightly water-coloured cliff, an imaginary precipice sprouting spindly trees, towers over a castle and a dock (illus. 67).111 The view is primly framed – the thin grey borders on the sides and the lower edge certainly precede the drawing – and large enough to be inserted directly into a background window. This is the compositional convention that provoked the young Dürer to draw fanciful cliffs, such as the flinty Cliff Landscape (illus. 68) in Vienna, with a ghostly wanderer visible at the lower centre, arm outflung.112 This drawing is based on a workshop formula from Wolgemut’s shop, perhaps specifically the Landscape with Wanderer (illus. 69) in Erlangen, with its colonnade of ghoulish, beetling monoliths.113 The tree splits the landscape between wilderness and civilization. The wanderer, with a drawing-board on his back, hunts for views. Wolgemut’s workshop, however, left no relics of such sketching tours. Even Dürer, at the start, was content to draw indoors. In his Vienna landscape he converted the cliffs into an open field for free play of the pen; his curving modelling strokes create rock that is alternately frothy, knobby, metallic. Only later would he attempt to depict real cliffs.

63 Nicoletto da Modena, Marcus Aurelius, c. 1507, engraving, 21.2 × 14.4. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

64 Jean Pélerin-Viator, La Sainte Baume, from his De artifιciali perspectiva, published in Paris in 1509 (2nd edition), woodcut. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

65 Giovanni Bellini, Coronation of the Virgin, early 1470s, oil on panel, central panel 106 × 84. Museo Civico, Pesaro.

66 Stephan von Urach, Landscape Study, from his modelbook, late 15th century, pen and watercolour. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

67 German master, Cliff Landscape with River, late 15th century, watercolour and gouache on paper, 20.1 × 10.6. University Library, Erlangen.

In the 1490s, on his first Alpine crossings and at home in Nuremberg, Dürer made a series of watercolour studies of outdoor scenes and motifs.114 These watercolours were his private notations of potential pictorial motifs. About thirty survive. They served as memoranda for future works, and indeed many were reincarnated in the backgrounds of his prints (see p. 138, illus. 83, 84). Dürer did not bother signing them (all the monograms and dates were added by followers or later owners). Some represent swatches of unprepossessing mountainous terrain, corners of the landscape too negligible and obscure to serve any topographical purpose. A study in Berlin of a quarry or a cliff-face with dead branches, for example, seeps across the sheet of paper with little regard for the edges (illus. 70).115 The motif is not positioned in space or attached to the earth. The sheet says little about scale or distance. It looks like a fragment, and at the time would have held little interest for anyone outside a painter’s workshop. But many of the surviving landscape watercolours look more like finished pictures: views of cities, buildings, local landmarks, some tree studies (illus. 152–3). In other cases Dürer assembled impromptu compositions out of the natural material. The Pond in the Woods (illus. 74) in London, for example, is built on a grid of two stands of firs and a band of clouds.116 Evidently Dürer chose to leave the trees on the left unfinished in order not to mask the clouds. The horizon, not a line but the edge of the wash, is bent in an arc.117

68 Albrecht Dürer, Cliff Landscape with Wanderer, c. 1490, pen on paper, 22.5 × 31.6. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

69 Nuremberg master, Cliff Landscape with Wanderer, c. 1490, pen on paper, 21.1 × 31.2. University Library, Erlangen.

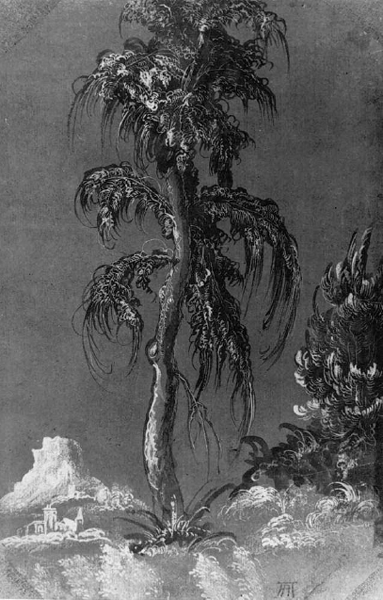

This becomes a pattern, then, in the first years of the new century: model drawings and life studies increasingly resemble complete and self-sufficient pictures. They are detached from their workshop usefulness. They start to exhibit bravura effects of colour and line, strong style. The cliff in particular served as a template for some of the earliest independent landscape drawings. Urs Graf, a Swiss follower of Altdorfer, transformed a cliff, in a drawing dated 1514, into a wild anti-gravitational fiction (illus. 71).118 Hans Leu and Niklaus Manuel Deutsch made similar landscapes, and frequently signed and dated them (see illus. 163–4). Functionally, these drawings have nothing in common with the modelbook studies: they are not pointing toward any future work. And yet their spirit of fantasy and hyperbole is not alien to the old pragmatic cliff studies.