Afterword to the Second Edition

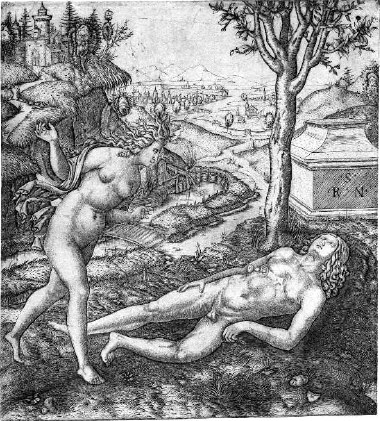

Altdorfer’s forests are often theatres of violence. One pen drawing gives us a dead man mourned by a tree (illus. 44); another, a harrowing encounter between a family of forest-dwellers and a murderous intruder (illus. 46). We witness brigands binding a man to a tree (illus. 94); the lonely tournament between St George and the Dragon (illus. 96); and the body of the suicidal Pyramus, reckless interpreter of signs (illus. 42). To venture beyond the walls of the town and into the leafy tangle, the artist suggests, is to risk deception and self-loss and to invite the bite of claw or blade. Altdorfer revisited the Pyramus and Thisbe story in a woodcut dated 1518 (illus. 204). According to Ovid (Metamorphoses 4:55–166), the maiden Thisbe, alone in the forest and awaiting her paramour, fled from a lioness; in her haste she lost her veil. When the lover Pyramus came upon the paw prints and the veil, stained by the blood of the lion’s earlier, furry victims, still fresh on his teeth, he drew a false conclusion and took his own life. Thisbe returned to the spot, found the corpse, and in despair followed Pyramus into death. Here she leans in taut prayer over the body sprawled on a tomb-like slab. The dagger stands upright in the belly. Forest growth presses heavy from above, crawling over the arched lip of the royal tomb that served as their meeting-point. By forsaking family and convention in favour of a forbidden assignation in the wild, the lovers exposed themselves to malignant forces.

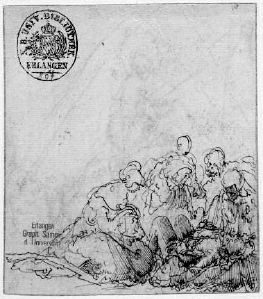

In a pen drawing, a preparatory study for the woodcut, Altdorfer described the dark mouth of the tomb, Ovid’s ‘dreadful place’ (loca plena metus, 4:111), an emblem of the unknowability of the forest (illus. 205). Here the two bodies are knit together by trembling, contour-obscuring lines. The pause between the two suicides will be brief. Again the trees and the foliage above, described in shorthand, comment on the episode in mute, furious cycles.

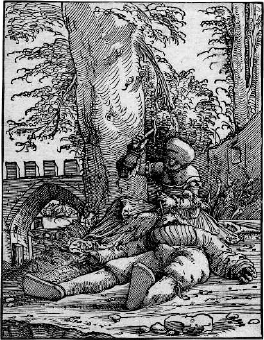

The principle of the forest in such works was disorder. Sight-lines screened, paths obscured, movement confounded: this was the anti-garden. The garden in Christian myth was an orderly system and a refuge. The garden was both the lost origin and, in images of the Virgin Mary seated in a grassy, flowered enclosure, symbol of the promised destination: Paradise. Altdorfer was more interested in the tangled places we fall into when we stray from the straight path that leads from the origin to the destination. The martial St George, in defence of the principle of purity, ventured into the wild growth and faced the beast. According to the legend transmitted from the Holy Land by the Crusaders, a bloodthirsty dragon blocked access to a spring. The community, requiring water, appeased the dragon by offering him their maidens. When the princess herself drew the fateful lot, St George came to her defence. A pen drawing, made more obscure by trimming on all four sides, depicts a stiffly mounted George, in pleated skirt and billowing sleeves, at closest quarters with the dragon (illus. 206). The beast’s spiked head coils back over its own rump. The dripping trees lean inward. The scene is confusing; the horse would grasp it no better, perhaps, if he were unblinkered.

205 Albrecht Altdorfer, Pyramus and Thisbe, c. 1518, pen and ink with grey wash, 13.4 × 10.6. University Library, Erlangen.

The present book, which was first published in 1993, interprets such scenes as allegories of iconoclasm. Religious reformers in Altdorfer’s day, in his Germany, exhorted the pious to banish meaningless cult images from their houses of worship as well as to obliterate the false ideals hidden in their own hearts. Altdorfer’s elliptical, mordant narratives figured this assault on the centre by overwhelming – laying flat or entangling – the protagonists of the stories and instead favouring the picture’s margins. His eviscerations of the traditional narrative picture rhymed with, perhaps even ratified, the scepticism of the reformers toward religious images, including eventually the Protestants who were ready to break with the Church. For the reformer, the image was a distraction and a falsehood. Altdorfer, in some drawings, prints and even paintings, took the unexpected step of removing subject-matter altogether. The vacuum in the picture-field was filled by teeming nature and by the artist’s unmistakable personal style, his handwriting. This was the origin of the independent or entirely subject-less landscape. The sacred body of the cult image reappeared in the depopulated landscape inside other forms. Strange bending trees half-remembered the subject-matter of the cult image. They were parodic surrogates for the banished saints, now twisted into bizarre, meaningless attitudes.

Landscape begins as the empathetic accompaniment to secret violence, and ends as its aftermath.

The book sought negative explanations for the empty landscapes. It defined the landscapes by what they were not, or what they were against. Positive accounts of the landscapes’ meanings were set aside or postponed. Now is the moment to reconsider meaning.

The artist himself would seem to be a good place to start; his view of the world, his sensibility. The artist, however, is as elusive as his subjects. His graphic mannerisms never come to rest. The virtual iconoclasm of Altdorfer’s works was never realized, for he did not abandon religious imagery but rather went on making paintings, drawings and prints of Christian subjects. Many of these works are marked by irony. They say one thing but mean another; and don’t seem ever to ‘settle’. This quality of Altdorfer’s art is difficult to describe and none of his modern commentators has focused on it. Altdorfer’s damaged narratives, the aftermaths and the pauses, the obscurities, raise the most basic questions about who the artist is, who an artist is. What is his point of view? Do his works give us any access to his convictions or his sensibility?

Altdorfer’s characteristic enlongated figures can stake out a narrative scene with dignity: recall for example the Christ Taking Leave of His Mother (illus. 13), in the National Gallery, London, where a poised, monumental Christ, about to head off for the last time to Jerusalem, addresses his misgiving mother. Such a painting, one of his largest, supports comparison with the oneiric compositions, populated by lithe sleepwalkers, of the Tuscan Mannerists Domenico Beccafumi (1486–1551) and Jacopo Pontormo (1494–1557), near contemporaries of Altdorfer. But a comic shadow falls on the German artist’s painting. Heads are too small. The elderly women who tend to the Virgin are stretched to preposterous lengths. The relentless energy of the surroundings diminishes the majesty of the statuesque Christ and John.

Overdeveloped landscape settings, here and elsewhere in Altdorfer, ironize subject-matter. The artist seems always to be suspending questions about content: what did the story mean, what was its import? He rebuffs the beholder’s emotional participation by withholding his own participation in his subject-matter.

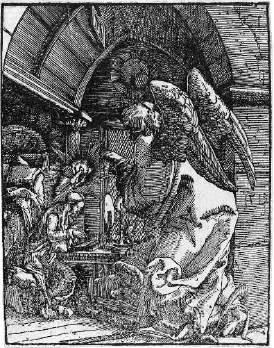

The long-limbed figure in Altdorfer is often a mildly mocked figure. An example is the astonishing figure of the angel Gabriel in the woodcut of the Annunciation, a lumbering, tousle-haired youth barging into Mary’s chamber (illus. 207). He looks like a farm boy in an ill-fitting theatrical costume. Altdorfer’s gentle travesty – the word does strictly, or at least etymologically, mean ‘cross-dressing’ – reminds us of the husband Joseph’s tearful protests, recorded in the Infancy Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew: ‘Would you have me believe that an angel of the Lord impregnated her? It is indeed possible that someone dressed up as an angel and tricked her. With what aspect am I to go to God’s Temple?’ Joseph’s anxieties about cuckoldry restore the basic strangeness of the story. For the myth of a non-violent insemination, communicated by a divine emissary, hides a more plausible, straightforward explanation of the pregnancy. By de-androgynizing his angel, Altdorfer tests that realistic hypothesis. No doubt that hypothesis was made available by the religious theatre of the day. The story of the Annunciation invites its own humanizing retellings that hint at a demystifying realism. This bringing down to earth is the essence of comedy. The entire story of the Holy Family is comic in the sense that it is familiar and familial.

206 Albrecht Altdorfer, St George and the Dragon, c. 1508, pen and ink on red-brown ground, 15.5 × 10.7. University Library, Erlangen.

Fair game for mock-heroics was the Old Testament champion Samson, the dupe of his own desires. In Altdorfer’s drawing of 1506, the bulky cavalier, sated after plein-air love-making, codpiece swollen, limp arm outstretched, reclines on the knee of his treacherous Philistine lover, Delilah (illus. 208). This practical personage has just pulled a pair of scissors from the sheath at her belt and is on the point of separating Samson from his remaining hair (he is already bald on top). She beckons to her accomplices arriving from the rear. Delilah is outfitted like the fancy lady of a modern military man: towering headdress, exposed shoulders, slashed sleeves, a string of beads. The biblical scene is translated into the idiom of contemporary depictions of lansquenets and meretricious camp-followers.

The woodcut of the Beheading of John the Baptist is a mighty convex composition (illus. 209). Architectural weight bears down from above onto the headless body. Herod’s palace rises on the right out of a massive ruined wall and vault. A great pointed arch, now overgrown, straddles the street leading to town. The double row of courtiers inspects the corpse, their bent bodies replicating the curve of the stone arch. Altdorfer generates comedy by taking us behind the scenes to the site of the execution: he has moved the feast out of the palace’s back door – still ajar – and into what appears to be a public space. The onlookers in their finery peer down at the body as if they had witnessed a traffic accident.

As in so many of his images of the fallen, Altdorfer seems unwilling to open a path forward to redemption. The spectre of meaningless sacrifice looms.

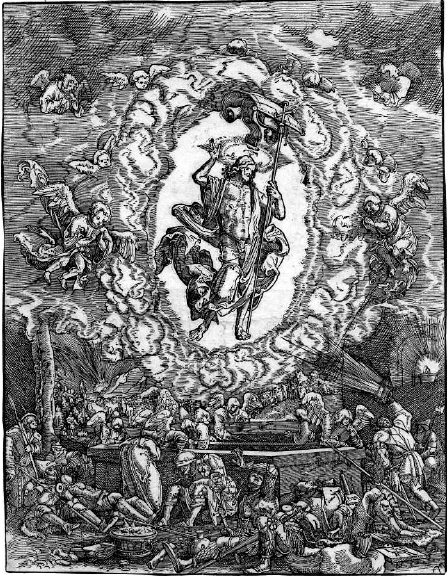

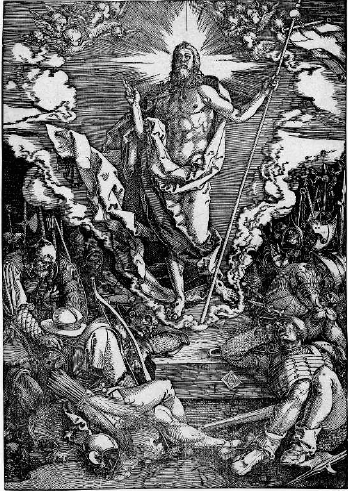

There is latent comic potential throughout the Christian myth, especially at its ragged legendary margins. St Christopher, a folkloric figure, today no longer even regarded as a saint by the Church, was an invitation to burlesque. This was a gentle giant, a simpleton, bent under the growing weight of the child – the weight of the world – whom he ferries on his back across a river. In Altdorfer’s drawing in Vienna (illus. 139) the porter is toppled backwards into the shallow waters. More innovative, and harder to recognize, is the comic approach to the Resurrection of Christ in the woodcut dated 1512 (illus. 210). It is revealing to compare this image to Dürer’s woodcut of 1510, its model (illus. 211). Altdorfer’s Resurrected Christ, hovering above the open tomb, is a direct quotation of Dürer’s. The older artist pictures transcendence and classical poise. Dürer contrasts the heavenly light enveloping Christ with the shadowy realm where the soldiers sleep. Like Michelangelo’s slumbering slave in the Louvre, which dates from 1513–1516, the tomb-watchers are earthbound, drugged by creaturely existence. But Altdorfer cannot bring himself to take all this too seriously. He draws Dürer’s soldiers, a dozen in all, out of the shadows and into the space around the giant-sized tomb. Now we clearly see at least eight sleepers and three more awake, including a figure at the right who casts the beam of a lantern upward as if to supplement the divine light radiating from Christ’s person. Although Altdorfer’s print is only about two-thirds the size of Dürer’s, it is denser with incident. A candle in a basin at the far right offers further manmade competition with the aureole. Altdorfer propagates mundanity throughout the mythic corpus. He borrows Dürer’s bodiless angels but adds a team of stagehands fussing with the tomb lid, bending awkwardly into the tomb, conversing with the lantern-bearer; as well as a pair of heavy-bottomed child-angels suspended on the left and right hand of Christ. We saw, in his incomplete forest stories, how iconographically frugal Altdorfer could be. Now suddenly he is prolix. But this is prose, not poetry: the link between the music and the sense has been broken.

207 Albrecht Altdorfer, Annunciation, 1513, woodcut, 12.2 × 9.5. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. |

|

Altdorfer tells a serious story but in a slightly mocking tone. In her book Other People’s Myths (1988), Wendy Doniger called attention to traditions of performance of shadow-plays in Indonesia and Bali involving two levels, a heroic story and a simultaneous demystifying commentary: ‘In front of the puppet theater stands a human figure . . . a clown who speaks in the vernacular or in a low dialect. He mocks the hero and expresses the audience’s cynical rejection of the noble ideal.’

208 Albrecht Altdorfer, Samson and Delilah, 1506, pen and ink on brown ground, 17 × 12. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

209 Albrecht Altdorfer, Beheading of John the Baptist, 1512, woodcut, 20.3 × 15.5. British Museum, London. |

|

To some extent Altdorfer was simply mocking the high-minded piety of Dürer, the looming exemplar and rival for every German artist of the period. His Resurrection woodcut is a parody of Dürer’s: a counter-song, a derisive repetition of another work whose full negative charge is not released unless the recipient knows that targeted work. But Altdorfer could not count on every viewer knowing Dürer’s Resurrection, even if everyone knew his style and manner. His comedy had to have greater reach. He had to bring out what everyone agreed was the comic potential locked in the stories.

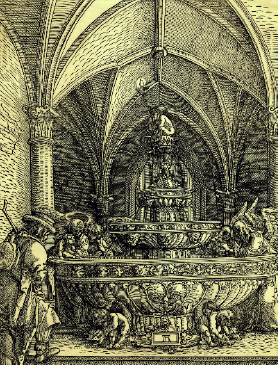

According to the Apocrypha, Mary and Joseph refreshed themselves at a spring en route from Bethlehem to Egypt. The scene was often painted – by Altdorfer, too (illus. 53) – because it was a pretext for a depiction of landscape. In the woodcut Holy Family at the Fountain he renounces this opportunity and displaces the fleeing family’s traditional oasis hiatus to a vaulted chamber (illus. 212). The fountain is now expanded: a triple-tiered extravaganza with foliate carvings – the forest condensed and fitted to an artefact – and crowned by a sulking nude idol. The outsized basin has pushed the Holy Family themselves to the margins. There will barely be room for Joseph when he steps onto the platform. The real tension of the image is between the indecorous, clamorous pomp of the fountain and the prosaic family. In structural terms the fountain plays the same role that empty space plays in the landscapes: it displaces subject-matter. The fountain competes with the Holy Family. The stage prop has become the focal point.

210 Albrecht Altdorfer, Resurrection of Christ, 1512, woodcut, 23 × 18. British Museum, London.

211 Albrecht Dürer, Resurrection of Christ, 1510, woodcut, 39.1 × 27.8. British Museum, London.

Altdorfer is a realist about human nature; he is unwilling to affirm anything; he is sceptical about virtue and high ideals; he allows stories to collapse back into the local if they cannot fulfil their pretensions to universality. Every story is told as if it were familiar, proximate, homely. He is unwilling to beautify. This is an aesthetic of renunciation. His drawings – among the first pen drawings by any artist to be signed and dated and offered to a public as finished works of art – should be compared to the unpainted wood sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider and others. Such works no longer relied on the blandishments of colour or the thrill of illusionism. Altdorfer punctures solemnities, flouts decorum, mocks pretension, ornament, costume and rank. There is an implicit populism.

This is confusing to historians. Is he a ‘popular’ artist? He was one of the elites of his town. But where did he come from? Where did his sympathies lie? The waters are muddied by Altdorfer’s ambiguous reception in twentieth-century German scholarship and culture, where he often figured as an exponent of an authentic ‘folk’ mentality and so a foil to the ambitious cosmopolite Albrecht Dürer. The terms ‘Danube Style’, coined in 1892 by Theodor von Frimmel, and ‘Danube School’, in use at least since the 1920s, were and are loose designations of a constellation of artists working in southern Germany in the first decades of the sixteenth century – Altdorfer and Wolf Huber most prominent among them – whose art was supposedly rooted in the local landscape. Whether these artists understood themselves as a constellation, a school or a style is doubtful. But in art history the terms became code words for sympathy for the local over the cosmopolitan, and for nature over civilization.

In the National Socialist exhibition Schaffendes Volk (Creative People) staged in Düsseldorf in 1937, a reproduction of Altdorfer’s Battle of Alexander (illus. 8) was the centrepiece of the section dedicated to ‘the German Lebensraum’. The picture, synthesizing a natural attachment to the land with a striving towards infinity, was held to symbolize struggle as the ‘principle of life’. Completely unknown in the nineteenth century, Altdorfer was suddenly ubiquitous. In 1939 Hans Watzlik published a historical novel about Altdorfer, Der Meister von Regensburg: Ein Albrecht-Altdorfer-Roman (1939), one of the many popular biographies of German Renaissance artists published in the Nazi period. On the last page the painter on his deathbed raises his arm

toward a glowing cloud; there may never have been in the world a more noble color than its purple.

He appeared to be praying to the cloud.

With this gesture he expired, obedient to his destiny, together with the dissolving cloud, and his divine eye sank into the twilight of eternity.1

In the same year the prominent art historian Wilhelm Pinder, a venomous anti-Semite and a leader among scholars sympathetic to National Socialism, matched Watzlik by closing his Deutsche Kunst der Dürerzeit: Geschichtliche Betrachtungen über Wesen und Werden deutscher Formen (1939) with a hymn to the pure landscapes of Altdorfer, ‘one of the few who survived [the end of the Dürerzeit, or ‘age of Dürer’, with its unwholesome curiosity about Italian art] unscathed. While the others cooled off, he remained warm. He did so, because he was a devoted man. Three hundred years later Philipp Otto Runge saw in landscape the last possibility of the European. Altdorfer was the first to conquer it.’2

212 Albrecht Altdorfer, Holy Family at the Fountain, c. 1512–15, woodcut, 23.1 × 17.5. British Museum, London. |

|

An antidote to this poison was Erwin Panofsky’s great monograph of 1943, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, where he presented Dürer as the exponent of a pan-European and humanistic culture. After Panofsky, it was no longer possible to claim Dürer as a Germanic culture-hero. Altdorfer, however, whose involvement with Italian art was easier to overlook, persisted as a symbol of a regional or völkisch genius. Alfred Stange, for example, who held the chair of art history in Bonn from 1935 to 1945 and was active in National Socialist politics, characterized Altdorfer and Paracelsus, the physician, alchemist and natural philosopher, as kindred souls, motivated by the same joyous piety, warm sympathy for creation and love of simple people (Malerei der Donauschule, 1964). Franz Winzinger, meanwhile, the author of the three-volume standard monograph and catalogue raisonné, described the painter’s Two St Johns in Regensburg, as late as 1975, as ‘an overwhelming testimony to a deep nature-piety, numbering among the most illuminating expressions of the German spirit, seldom so purely revealed in a work of art’. The sequence of panel paintings illustrating the legend of St Florian, according to Winzinger, is valuable in part because its supposed depictions of the common people of Altdorfer’s time preserve for us bajuwarische Volkstypen, ‘Bajuwarian ethnic types’. (Bajuwarian is an archaic term meaning ‘Bavarian’, implying that Altdorfer was delivering the physiognomies not just of his contemporaries but of the ancient Germanic tribes described by the sixth-century historians Jordanes and Venantius Fortunatus.) To be fair, Winzinger in his monograph was mostly interested in describing form and stabilizing attributions and dates. His scrupulous scholarship in many ways drew the curtain on the generation of sentimental, regionalist and racist writing about the artist. Nevertheless, he and others of his generation looked to Altdorfer as a compass of authenticity, providing orientation among the bewilderment and, let us say, moral ‘layering’ of the post-Second World War decades. These scholars reproduced the very fallacies that had led their civilization astray in the first place.

The next generations of German scholars, coming of age either with the new mood of sobriety and methodological responsibility of the immediate post-war period or with the newly critical, usually Marxist, art history of the 1970s, dissociated themselves not only from this tradition of writing, but also from German art generally as a research topic. German scholarship on Altdorfer lagged in the 1970s and ’80s.

American and British scholars, meanwhile, unburdened by history, turned to German Renaissance art with all the fervour of discovery. In 1970 the field was still terra nova for English-speaking art historians. The German image, registering with urgency the religious upheavals, the class and gender warfare, the persecution of witches and the texture of everyday life was the perfect laboratory for a contextual, politically progressive history of art. Woodcuts, engravings and illustrated books and broadsheets were easily recognized as the early forms of the modern mass media. Rough-hewn German art had been neglected by elite collectors and American museums. The historian of German art, unlike the historian of Italian art, did not have to fight through layers and layers of scholarly commentary on attribution, dating and condition.

In the last decade younger German scholars have returned to the art of fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Germany. Archival research has given us a clearer picture of Altdorfer’s ties to local politics and patronage. Two outstanding monographs, by Magdalena Bushart and Thomas Noll, both published in 2004, portray an artist who adapted traditional religious imagery to the expectations of a newly sophisticated public. Noll interprets Altdorfer’s innovative framings, croppings and foreshortenings not as signs of creeping secularization, but as intensifications of the devotional attitude. Bushart interprets Altdorfer’s works as pictorial commentaries on an array of devotional and extra-biblical narrative texts.

We still know little about Altdorfer. Yet he seems omnipresent in his works, in his style. He marked many drawings, prints and paintings with his monogram AA, a variation on Dürer’s famous AD. Even those works that do not bear the monogram are signed in the sense that the entire work is a graphic signature. The artist’s signature offers a new myth of the origin of the work of art. But Altdorfer also held up his strong personal style – the graphology but also the distorted figures – like a mask, a persona, concealing his face. He gives his publics no choice but to defer their curiosity about the beliefs and the identity of the artist. This unknowability has earned the artist a twilit reputation. How does Altdorfer measure up to his contemporaries: Dürer, Lucas Cranach, Matthias Grünewald; or, among the great Italians who seem closest to him in sensibility, Correggio, Dosso Dossi and Parmigianino, as well as Beccafumi and Pontormo? It is not clear. Was he naive or sophisticated? Cut free from convention, experimental with medium and format, his works on paper were addressed to limited private circles. These works disorient. It is difficult today to get any critical grip on them because they were originally enveloped in conversation. They court but elude judgment.

According to Aristotle, a speech persuades through pathos, the expression of emotion, and logos, rational argument. But it is also the moral character of the speaker that inspires confidence in the speech: this is ethos. ‘Persuasion is achieved by the speaker’s personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him credible. We believe good men more fully and more readily than others’ (Rhetoric 1356a). Ideally, this character is not simply known to the listeners in advance but is revealed by the speaker’s words. Altdorfer’s works give us little access to a stable moral being who might underwrite their content. One might hesitate before stating, as Franz Winzinger did, that the bloody head of Christ in the Crucifixion with Virgin and St John (illus. 11) ‘can only have emerged out of the master’s deep spiritual agitation’. In any case, Altdorfer was not an orator. His contemporaries, if asked how to connect a painting to a person, might have said that the painter had every right, perhaps even an obligation, to conceal himself behind his works. Most of Altdorfer’s contemporaries would simply not have understood the question. The orator was an established social role that implied a certain relation between person and words. But the relation of an artist to his work was by no means established. The German artist now for the first time, in Altdorfer’s lifetime, felt emboldened to compare himself to the poet, the scholar, the natural scientist. Meanwhile, religious reform, leading finally to the schism of the Church, was inviting ordinary people to put their own beliefs into words; to test the depth of their convictions; to calibrate their personal beliefs against public creeds or ‘confessions’. Many artists and artisans were drawn to the Lutheran project of reform, with its double message of return to the pure doctrinal sources of Christianity as revealed in scripture, and liberation from the oppressive Roman Church. German painters and sculptors plunged into confessional and class politics. The sculptor Riemenschneider was a member of a city council that formed an alliance with the revolutionary peasants. He was imprisoned for two months and his hands were broken. The artists Sebald Beham, Barthel Beham and Georg Pencz were tried in Nuremberg in 1525 for their associations with socially radical Protestants. They were banished from the city. The painter Lucas Cranach was a close friend and ally of Martin Luther. Together they designed a new Protestant iconography. But in the 1520s Cranach nonetheless continued to work for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, an imperial elector and one of Luther’s most steadfast opponents, delivering almost 180 paintings for his church and residence in Halle, no more than three days’ ride from Luther’s Wittenberg. It would be meaningless to accuse Cranach of hypocrisy. He was working in a period when expectations about the coordination between an artist’s production and his convictions were shifting.

Altdorfer’s unapproachability tantalizes because he was a public figure. He served on the city council and as the city’s architect or director of public works (see p. 18). At the heart of the question is his co-responsibility in the city’s attack on the liberties and property of the Jewish population. The 500 Jews of Regensburg, deprived by the death of the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian of legal protection, were expelled from the city in 1519. As a city councillor Altdorfer was implicated in this decision. He published two etchings based on eyewitness drawings that document the evacuation of the synagogue on the eve of its destruction (illus. 185–6). His attentive description of the doomed building, furnishing modern historians with valuable archaeological data, encourages some scholars to discern a measure of sympathy for the Jews. But the inscription on the etching describing the synagogue’s vaulted interior is clear: ‘In the year 1519 the Jewish Synagogue in Regensburg, according to God’s righteous judgement, was destroyed from the ground up.’ Altdorfer produced paintings and prints promoting the profitable pilgrimage of the Schöne Maria of Regensburg, a cult of the Virgin that crystallized when a labourer injured during the demolition of the synagogue was miraculously healed. In 1519 Altdorfer was paid for illuminating the parchment certificate of indulgence, acquired at the papal court by the town’s agents in Rome, that launched the pilgrimage. Protestantism made inroads into Regensburg, but there is no evidence that Altdorfer strayed from the old faith. From 1534 he occupied the post of provost of the Augustinian convent of St Salvator in Regensburg.

A ‘man of the people’? Altdorfer’s literate art implies that he was in easy converse with the educated elites of his community, clerical and lay. His satire lacks a political edge: it is never carnivalesque or subversive. His interest in picaresque soldier-folk or rustic manners does not imply humble origins. There were plenty of precedents for his comic tone in the pictorial tradition. The theme of the wily women mastering gullible sensuous men was well established in engravings, a medium that broadcast the profane themes of courtly wall paintings and tapestries. The iconography of soldiers and camp followers, the colourful mercenary tribe traversing the fields and the imagination of the Germans, was entrenched in prints. Rude or savvy vernacular subject-matter was ubiquitous, in public fountains and statues, in carvings in the margins of buildings, in the decoration of boxes, chests, furniture, weapons.

But there is a crucial difference: Altdorfer enframes this material in an artist’s career. The emergent institution of the work of art, signalled by monogram and date but also by conventions of pricing and display invisible to us today, offered subject-matter accompanied by a framing message: namely, that this subject-matter has been chosen by an artist from an array of possibilities. Take the subject of Pyramus and Thisbe. Here Altdorfer was guided by the Italian printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi, whose engraving depicts the figures in the nude (illus. 213). Marcantonio’s Thisbe, still trailing a fragment of her veil but otherwise nude, arrives at the fatal scene. Pyramus sleeps the sleep of death. The nudity sends the message that the Ovidian story is a mere pretext for the classicizing nudes (or for that matter the landscape, modelled on Dürer’s prints). Marcantonio’s engraving provided Altdorfer with a basic composition. But the German artist was unwilling to adopt the abstracting convention of nudity, perhaps finding it nonsensical. In his own prints and drawings of the subject he reverted to clothed figures, just as one found them in earlier manuscript illuminations. This allowed him to re-enter the story. But then by giving his lovers not the timeless robes of romance but modern fancy garments, he introduced that story into yet another stylistic sphere. The dissonance between Marcantonio’s classical treatment – at least for those who knew the Italian print or others like it – and Altdorfer’s familiarizing, desublimating treatment created the humour. With Altdorfer, a vernacular, comic mode becomes one of the tools in the toolbox of an author. Altdorfer’s choice between modes in turn becomes an aspect of meaning. The ‘how’ is folded – by the beholder – back into the ‘what’.

213 Marcantonio Raimondi, Pyramus and Thisbe, 1505, engraving, 23.6 × 20.5. British Museum, London.

It was no different when he approached traditional religious image-types. A painting of the Crucifixion in Budapest, for example, reactivates two archaic conventions more characteristic of a painting of the 1470s than a painting of 1520: the crowd of onlookers engulfing the Cross, and the gold ground. The painting addresses two layers of beholders at once: a less-informed worshipper who doesn’t pose himself any questions about when the work was painted, and a better-informed amateur of the art of painting who sees the old-fashioned image-type, as it were, in quotation marks.

In a basic economic sense Altdorfer’s wry drawings were not popular at all: they were not sold on an open market but were meant for collectors, insiders; whether sold or given as gifts it is hard to say. The intimate address of the graphic arts licensed a rhetoric of nonchalance. A painting was another matter. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt mentioned earlier (illus. 53) was a votive image: a painting offered to the Virgin, presumably displayed near a shrine or altar, as a public attestation of piety. The inscription reads: ‘Albrecht Altdorfer, painter of Regensburg, dedicates this gift to you, divine Mary, with a faithful heart, towards his own salvation’. No other German artist of the period left such a relic. Few religious paintings of the epoch achieve the saturated intensity of the great The Two St Johns in Regensburg, an image of the pair of visionaries seated side-by-side, as if in conversation, before a vast landscape (illus. 12).

The panels depicting the legend of St Florian, the ones described by Winzinger as a mirror of racial types, include an image of a popular miracle-cult that emerged at a spring (illus. 214). Seven panels survive, in four different collections, remnants perhaps of an altarpiece. St Florian was martyred in Upper Austria in 304, under the emperor Diocletian. According to the legend, composed probably in the ninth century, the sudden appearance of a spring revealed to a pious woman where she ought to bury the saint’s body. The healing water became a destination for pilgrims. The painting portrays a real church, the site of the spring, St Johannes in the town of St Florian, consecrated in 1116. Altdorfer depicts not an event but a timeless activity repeated by local worshippers over centuries. The painting suggests sympathy for the popular cult. A dozen and a half figures of all ages cluster at the spring, but without confusion or contest. The bodies of the pilgrims intertwine; they clamber like putti, symbols of the sensual, affective life. The picture’s space curves inward, the stairs at the left bend, cupping and containing the human activity. The seated woman with the child in the lower-right anchors the picture. The composure and firm footing of the woman in white standing on the ledge at the right seem to register the artist’s confidence in the meaningfulness, if not the efficacy, of the cure.

214 Albrecht Altdorfer, The Miraculous Spring of St Florian, c. 1518–20, oil on panel, 81.3 × 67.3. Private collection.

Some of the best writing on this artist in the last decades has tried to describe the underlying formal structure of the pictures. Karl Möseneder, Andreas Prater and Margit Stadlober have all stressed the power of shapes, lines and light to bind the landscapes and the pictures together. The Miraculous Spring of St Florian achieves exactly this centripetal weave, but with little help from landscape as such. Here it is done with bodies and with space. The lesson is that pictorial form can work to either end in Altdorfer: it can disintegrate, as we have seen, or it can integrate.

In The Miraculous Spring of St Florian, the forces that bind are human emotions. How does one square such a pictorial profession of compassio with the iconoclastic gestures and the intellectual detachment and self-concealment, the dissimulatio or dissembling, of the graphic work? Is there a centre of gravity somewhere in this oeuvre, a point between the ready-made piety of the folk, which may after all be just another of Altdorfer’s masks, and the tragicomedy of conflict and missed appointments in the forest?

A pair of images framing death provides clues. A drawing in Erlangen depicts a Lamentation over the Dead Christ (illus. 215). This is not a finished or collectible drawing but a preparatory study for some unknown composition. It is related stylistically to the Pyramus drawing discussed earlier (illus. 205). This Lamentation is a ripe meditation on death. The four mourning figures have been ‘grown’ from the same substance as the corpse. The pen line is palpating, softly stroking, additive, as if burgeoning out of the humus. It is an image of forest undergrowth, life emerging from decay; an image of the continuity of death and life. The empty upper part of the sheet will eventually be colonized by life and growth. Here is redemption as an ecological principle.

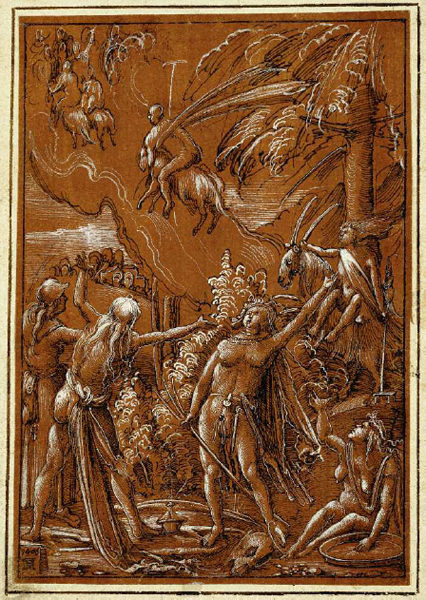

Contrast this to the woodcut depicting Jael and Sisera (illus. 216): again, a supine man tended by a woman. This one is about to drive a tent spike through the man’s head. Jael is the temptress who delivered the Jews from submission to an alien king, Jabin; Sisera was his military chief (Judges 4: 17–21). Altdorfer makes no effort to historicize. They are in modern costume. Instead of a biblical war camp we are with modern lovemakers on the margins of a familiar-looking arched and crenellated city gate. The gentleman has fallen into post-coital or at least post-picnic slumber. Jael is a heroine and a type for the Virgin, but she is also a symbol of the dangerous threat that women pose to desiring men. The scene was familiar from illuminated manuscripts and simple woodcut book illustrations. The surplus of information that creates the comedy in Altdorfer’s work is the setting: the public road just beyond the city gate seems the wrong place to commit this gruesome murder.

The sexuality of the encounter between Jael and Sisera shines through the sardonic, demystifying realism. The crouching, hollowed form of Jael is placed in contrast to the verticality and solidity of the tree and the irreversible horizontality of the man. The web of rhyming images – the versions of Pyramus and Thisbe, the Beheading of the Baptist, the Lamentation over Christ – brings out the ambiguity of the women’s gestures and postures, their crouching, convex forms. Tending and menacing are pulled close to one another. One is reminded of the hint of threat in the serpent-like St Anne as she watches over her daughter and the Christ Child in Leonardo da Vinci’s cartoon, or full-scale preparatory drawing, in London. The continuity between generation and destruction was already present in Ovid’s report on the miscommunicating lovers: despairing Thisbe falls on the knifeblade, ‘still warm from the slaughter’ (adhuc a caede tepebat, 4:163), that she has extracted from her lover’s body.

It is Jael’s garment that identifies her attentiveness to the man as predatory. The clothing – his, too – binds, divides, partitions the body. Contrast this to the formless robes of the mourning women in the Lamentation drawing (illus. 215). Instead of ecological generation there is sex with its pantomimes of violence. Parody is driven by travesty. The changes of clothing that drive the comic translations from sphere to sphere prevent meaning from ever settling in the way that it appeared to do in the The Miraculous Spring of St Florian.

And it will be nudity, finally, that steadies Altdorfer’s approaches to subject-matter, draining away the comic potential. The soft and stable cores of Altdorfer’s enigmatic vignettes of wild families – the small panel in Berlin dated 1507 (illus. 45) and the drawing in Vienna mentioned earlier (illus. 46) – are the broad-backed mothers, their nakedness threatened by spiky vegetation not to mention the passions of men. Absorbed in thought is the Bathing Woman, a minuscule engraving (illus. 217). Her left hand clutches a scraper, a bathhouse implement. Her abundant hair is gathered under a bonnet. The column, vase and mask-spout suggest a semi-public space. She pauses, broods, is suddenly vulnerable. Perhaps this is Bathsheba preparing herself for the royal assignation: the very moment chosen a little over a century later by Rembrandt in his famous Louvre painting. Her curved back and dropped shoulder, supporting a tumbling tress, read as the indices of an interiority, the inner resource that compensates for the loss of privacy implied by the apparent openness to the sky between column and wall.

215 Albrecht Altdorfer, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c. 1512, pen and ink, 11.1 × 9.8. University Library, Erlangen. |

|

216 Albrecht Altdorfer, Jael and Sisera, c. 1518, woodcut, 12.2 × 9.5. British Museum, London. |

|

The tiny format was Altdorfer’s invention. At first he was imitating Italian niello prints, images pulled from metal artefacts whose decorative incisions had been filled with a black metallic powder. The first such prints were meant simply to record the designs engraved in the metal. Altdorfer adopted the small scale of the niello print, possibly not fully aware of the material origins of his Italian models, and invested it with a new visual rhetoric. In Italian prints generally, as we have seen, he found the unmotivated nudity that became the emblem of a modern art liberated from its traditional settings and expectations. In the Bathing Woman he suspends the sympathetic figure between a motivated nudity (she is in a bath) and an ideal nudity (she recalls a classical Venus).

Altdorfer’s small engravings mask out the world and reveal heroes and heroines in their aloneness, exposed to ironization or to their own reflections. The works are intimate, wry, complicit. They were much imitated by other German artists, for example Pencz and the Behams, the rebels expelled from Nuremberg in 1525. Here is an engraving representing another nude woman, isolated, curved in upon herself; the virtuous Lucretia, evidently (illus. 218). She is an apparition of whiteness against the dense cross-hatching. The long blade touches her chest. The figure is an adaptation of a Venus extracting a thorn from her foot, a design by Raphael published in an engraving by Marco Dente. Nowhere else does Altdorfer strike quite this note of sensuality and tragedy, and indeed the engraving is no longer usually credited to him but rather to a follower, perhaps Sebald Beham. It bears no signature. Still, it is worth comparing the print to the Bathing Woman and reconsidering the attribution.

Sex is the theme of so many works by this artist, and yet the depicted bodies seldom incite desire. See, for example, the painting of Susanna and the Elders (illus. 54). In the small engravings it is as if Altdorfer’s diffidence about desire disappears. The Italian or classical material provided space for desire, clearing out distance from his own tradition. There was suddenly no need to divert subject-matter into satire.

Landscape, anthropomorphized by Altdorfer’s projective imagination, seemed a ‘sympathetic’ field, a place where the estrangements of civilization might be overcome. That was what landscape painting of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would later offer. But Altdorfer’s forests so often tend toward the zoomorphic, the teramorphic. These places are indifferent or worse, projections of fears that dissipate only when they tip over into comic exaggeration. The only sure path offered through the outdoor pictures is the way of dissimulatio, irony: the very opposite of empathy. The principle of compassio belongs to the interior space and the reflective woman.

The unreflective woman, without conscience, is the witch: a comic character in art who masked a real social tragedy. With Altdorfer’s drawing, Witches’ Sabbath, a flurry of pen lines on an orange ground, we are at the edge of the forest, the launching point for the witches’ midnight journey to their assignation with their lover, the Devil (illus. 219). The site of that gathering, the innermost recess of the forest, remains unpictured and hidden from the eyes of men; the emblem of a core of unknowability in the woman that the Bathing Woman and the Lucretia figure with sympathy, and the Witches’ Sabbath – or rather the myth it lampoons – figures with apprehension. This drawing makes the witches’ activities visible for the first time; from this point on there is an iconography of witches. The myth of the sabbath was assembled from folkloric elements by clerical prosecutors, Dominicans, authors of a handbook on witchcraft published in 1486, the Malleus maleficarum or Hammer of Malefactors. The handbook credited reports of nocturnal gatherings of women, the maidens initiated by the wives, involving child sacrifice, preparation of potions and eventually an airborne journey – distaffs, brooms and goats being the preferred vehicles – to Satan himself. This profound fantasy captured the imagination of prosecutors and, bewilderingly, accused alike, for there is ample evidence of freely offered female confession involving elaborate narration. Such confessions, and many more extracted under duress, licensed tens of thousands of senseless executions across two centuries. At this point, early in the sixteenth century, persecution of alleged witches was still sporadic and an urbane artist could easily mock the folkloric material. The artist Hans Baldung, the pupil of Albrecht Dürer, followed Altdorfer’s lead and developed a ribald sabbath iconography. Altdorfer’s frenzied witches are ridiculous in their fervour. The housewife, stripped for her rendezvous with the Devil, her unsuspecting husband asleep at home, still wears homely purse and shears around her naked waist. Lumpish, disshevelled, the women are anything but seductive; nor do they appall. The drawing casts a spell. The artist is ubiquitous. But the drawing also breaks the spell of the forest.

217 Albrecht Altdorfer, Bathing Woman, c. 1520, engraving, 3.8 × 3. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

218 Albrecht Altdorfer(?), Lucretia, c. 1520, engraving, 4.8 × 2.8. British Museum, London.

219 Albrecht Altdorfer, Witches’ Sabbath, 1506, pen and ink with white heightening on pale brown ground, 18.0 × 12.5. Musée du Louvre, Paris.