There is nothing righteous about dopefiends. They’re assholes; they’ll screw you. There is nothing enjoyable about this life.—Max

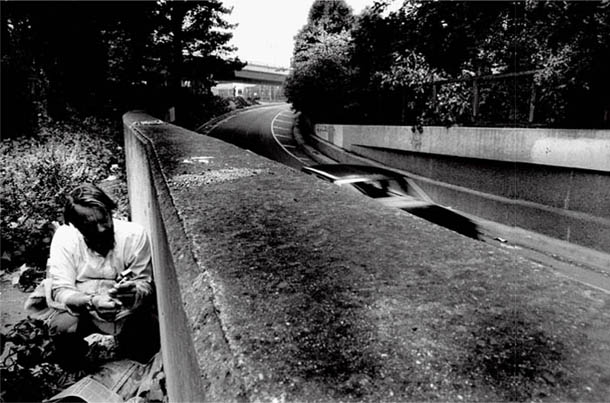

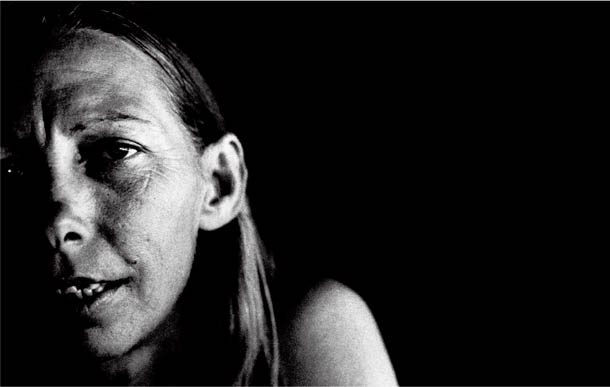

Cars shoot one by one around the blind curve of the exit ramp as they descend from the freeway without reducing their speed. Frank is the first to cross. He strains to listen, but the background roar of rush hour traffic above us drowns out the sound of oncoming cars. He takes a deep breath, jumps off the curb, and sprints safely past the DO NOT ENTER sign onto the median. Felix follows, crossing carefully but more confidently. Now it is my turn. I timidly stick out one foot as though testing the temperature of water, hold my breath, and dash to the other side. I have driven past this spot weekly for the last ten years, but when I feel it for the first time below the rubber sole of my shoe, and when I grab the iron guardrail to hoist myself onto the median, I feel as if I am stepping onto foreign soil.

We are approaching a shooting gallery known as “the hole,” a recessed V-shaped space beneath the juncture of two major San Francisco freeways. To enter it, we have to sidestep along a six-inch-wide cement beam for another ten yards, with cars rushing by on either side.

A discarded metal generator sits at the far end of the space. Three catty-corner, earthquake-reinforced concrete pylons support the double-decker freeways high above us and also shield us from the view of passing cars. My foot sinks into something soft just as Felix warns, “Careful where you step.” I move more cautiously now to avoid the other piles of human feces fertilizing the sturdy plants that were selected by freeway planners to withstand a lifetime of car exhaust. The ground is also littered with empty plastic water bottles, candy wrappers, brown paper bags twisted at the stem containing empty bottles of fortified wine, the rusted shards of a metal bed frame, and a torn suitcase brimming with discarded clothing. Behind the generator, a sheet of warped plywood rests on a milk crate; on top of the plywood, a Styrofoam cup half full of water and the bottom half of a crushed Coke can sit ready for use.

Frank and Felix eagerly hunch over the plywood table and prepare to “fix” a quarter-gram “bag” of Mexican black tar heroin. They are running partners, which means they share all their resources, including this twenty-dollar sticky pellet of heroin the size of a pencil eraser that has been carefully wrapped and knotted in an uninflated red balloon. Felix earned this bag as payment from his supplier. He gets one for free for every ten that he sells. Frank makes his money painting signs for local businesses, and it will be his turn to pay for the next bag that they will need to share five to eight hours from now to stave off heroin withdrawal symptoms.

Frank holds his syringe up to the light so that Felix can see exactly how much water he has drawn into its chamber from the Styrofoam cup. Frank nods, and Felix drops the heroin pellet into the crushed Coke can that is about to serve as their “cooker.” Frank squirts the water into the cooker and lifts it above the flame of a lit match cupped in the palm of his right hand to shield it from the wind. He moves the cooker back and forth over the flame to make sure it is evenly heated. A ribbon of smoke with the slightly sweet smell of burnt milk rises between us as the mixture erupts into a quick boil, prompting Frank to jerk the cooker out of the flame.

He stirs the sludge in the cooker with the flat top handle of the syringe, scraping the sides and bottom of the cooker until all the lumps have fully liquefied into a smooth broth. Satisfied, he licks the plastic handle so as not to waste a precious drop. The plunger has twisted slightly and turned black in the heat of the heroin concoction.

Frank calls out for “a cotton,” and Felix tears at a cigarette filter with his teeth. The white fiberglass strands splay with static. He rolls a clump of fibers into a tight ball between his thumb and forefinger and drops it into the cooker. Frank gently nudges the ball into the center of the puddle of heroin with the tip of his needle. It immediately absorbs the precious liquid, expanding and matting. Frank pierces the center of the swollen cotton with his needle and pulls back on the plunger to fill the syringe chamber with a bubbly rush of heroin solution. The cotton goes from a chocolate brown to an ashen gray.

“Hey, man! That’s more than half!” Felix shouts.

“Bullshit!” Frank retorts, but he obligingly squirts some of the heroin solution back into the cooker on top of the cotton, swelling it slightly. Satisfied, Felix eagerly draws the remaining heroin solution into his own syringe.

Frank pinches the back of his hand to search for a functional vein and then begins poking with the needle. Each time he punctures his skin, he pulls back gently on the plunger to see if blood is drawn into the syringe chamber, confirming that the tip of the needle is safely inside the tiny walls of a vein. On his third attempt, Frank finally registers blood and flushes all the heroin solution into his body at once. Flooded by an instant rush of heroin pleasure, he sits back and lets his chin drop onto his chest, sighing and bobbing in the euphoric state of relaxation called “nodding.”

Felix “muscles” his heroin without trying to probe for a vein. He jabs the needle up to its hilt directly into his biceps and slowly pushes the heroin into his fatty tissue. It takes him a couple of minutes to feel the effects, but soon he too is in a deep nod.

They are awakened from their nods by Max, who enters sweating and panting, his nose dripping. He has spent the day carrying furniture on a moving job, but he will not receive payment until tomorrow, when the job is finished, and he has no money to cover this evening’s injection. From several blocks away he must have spied us entering the hole because he has run over, hoping to receive a “taste” of heroin. Max expects Felix and Frank to treat him to the residue from their cotton filters at least once a day as “rent,” because they have moved into his encampment a quarter mile down the freeway embankment after being evicted from their camp by the police last week.

Felix obligingly pushes the crushed Coke can with the cotton sitting in the bottom toward Max. “Take the cotton; it’s a wet one.” Max eagerly pulls a syringe from his sock, squirts some extra water onto the cotton, and proceeds to “pound” it by squashing it repeatedly with his plunger handle, hoping to wring out every last drop of heroin residue. He is relieved because this will stave off full-blown heroin withdrawal symptoms until morning, when he anticipates being able to scrounge another cotton. In real dollar terms, a wet cotton like this can be purchased for two dollars or less, and two dollars can normally be panhandled in a couple of hours, even on a bad day.

From November 1994 through December 2006, we became part of the daily lives of several dozen homeless heroin injectors who sought shelter in the dead-end alleyways, storage lots, vacant factories, broken-down cars, and overgrown highway embankments surrounding Edgewater Boulevard (not its real name), the main thoroughfare serving San Francisco’s sprawling, semi-derelict warehouse and shipyard district.

The maze of on-ramps and off-ramps surrounding the shooting gallery nicknamed the hole is part of the commuter backbone servicing the dot-com and biotech economies of Silicon Valley and downtown San Francisco. These freeways connect some of the highest-paying jobs in the United States to some of the nation’s most expensive residential real estate. By building freeways all across the nation since the 1950s, granting generous mortgage tax breaks, and pursuing monetarist policies to stem inflation and lower interest rates, the U.S. government has effectively subsidized wealthy, segregated suburban communities, draining wealthy and middle-class residents from inner cities (Davis 1990; Self 2005). The hole was merely one of the many accidentally remaining nooks and crannies at the margins of this publicly funded freeway infrastructure where the homeless regularly sought refuge in the 1990s and 2000s. It was a classic inner-city no-man’s-land of invisible public space, out of the eye of law enforcement.

Frank and Felix chose to inject in a filthy, difficult-to-access spot like the hole rather than in Max’s nearby camp, where they were sleeping, not only out of fear of the police but also to avoid having to share a portion of their bag of heroin with Hogan, another one of their campmates, who had been complaining all day of being “dopesick.” They did not mind treating Max to a “wet cotton shot” because they knew he would be receiving money from his moving job the next day and he was likely to reciprocate their gift should they need it some time in the future. Hogan, in contrast, had a reputation for being lazy and perennially broke.

At any given moment, the core social network we befriended usually consisted of some twenty individuals, of whom fewer than a half dozen were women. They usually divided themselves up into four or five encampments, which frequently shifted locations to escape the police. All but two of these injectors were over forty years old when we began our fieldwork, and several were pushing fifty. All but the youngest had begun injecting heroin on a daily basis during the late 1960s or early 1970s. In addition to the heroin they injected every day, several times a day, they also smoked crack and drank large quantities of alcohol—primarily inexpensive, twelve-ounce bottles of Cisco Berry fortified wine (each one equivalent, according to a denunciation by the surgeon general of the United States, to five shots of vodka [Dallas Observer 1994, November 17]). According to national epidemiological statistics, the age and gender profile of our social network of homeless men and women was roughly representative of the majority of street-based heroin injectors in the United States during the late 1990s and early 2000s (Gfroerer et al. 2003; Golub and Johnson 2001; Hahn et al. 2006).

A separate generational cohort of younger heroin or speed injectors also existed in most major U.S. cities, but they maintained themselves in entirely separate spaces from older heroin addicts. Most of these youthful injectors were whites fleeing distressed and impoverished families, and they represented a smaller proportion of their generation than those who had been attracted to heroin in the 1960s and 1970s (Bourgois, Prince, and Moss 2004). Hip-hop youth culture in the 2000s actively discouraged injection drug use or crack smoking despite its celebration of drug selling. Consequently, those African-American and Latino youth who used drugs primarily smoked marijuana and drank alcohol, even when they sold heroin or crack on the street (Bourgois 2008).

Addiction is a slippery and problematic concept (Keane 2002). The American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual does not have an entry under the word addiction, and its criteria for identifying substance abuse refer primarily to maladaptive social behaviors caused by “recurrent substance use,” including, among others, the political-institutional category of “recurrent legal problems” (American Psychiatric Association 1994:182–183). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that within a couple of weeks of daily use, heroin creates a strong physiological dependence operating at the level of basic cellular processes.

The Edgewater homeless embrace the popular terminology of addiction and, with ambivalent pride, refer to themselves as “righteous dopefiends.” They have subordinated everything in their lives—shelter, sustenance, and family—to injecting heroin. They endure the chronic pain and anxiety of hunger, exposure, infectious disease, and social ostracism because of their commitment to heroin. Abscesses, skin rashes, cuts, bruises, broken bones, flus, colds, opiate withdrawal symptoms, and the potential for violent assault are constant features of their lives. But exhilaration is also just around the corner. Virtually every day on at least two or three occasions, and sometimes up to six or seven times, depending on the success of their income-generating strategies, they are able to flood their bloodstreams and jolt their synapses with instant relief, relaxation, and pleasure.

The central goal of this photo-ethnography of indigent poverty, social exclusion, and drug use is to clarify the relationships between large-scale power forces and intimate ways of being in order to explain why the United States, the wealthiest nation in the world, has emerged as a pressure cooker for producing destitute addicts embroiled in everyday violence. Our challenge is to portray the full details of the agony and the ecstasy of surviving on the street as a heroin injector without beatifying or making a spectacle of the individuals involved, and without reifying the larger forces enveloping them.

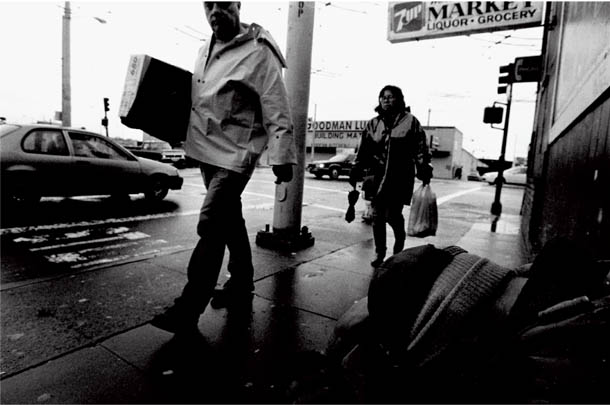

Begging, working, scavenging, and stealing, the Edgewater homeless balance on a tightrope of mutual solidarity and betrayal as they scramble for their next shot of heroin, their next meal, their next place to sleep, and their sense of dignity—all the while keeping a wary eye out for the police. Following the insights of the early twentieth-century anthropologist Marcel Mauss on the way reciprocal gift-giving distributes prestige and scarce goods and services among people living in nonmarket economies (Mauss [1924] 1990), we can understand the Edgewater homeless as forming a community of addicted bodies that is held together by a moral economy of sharing (Bourgois 1998b). Most homeless heroin injectors cannot survive as solo operators on the street. They are constantly seeking one another out to exchange tastes of heroin, sips of fortified wine, and loans of spare change. This gift-giving envelops them in a web of mutual obligations and also establishes the boundaries of their community. Sharing enables their survival and allows for expressions of individual generosity, but gifts often go hand in hand with rip-offs.

At first, we felt overwhelmed, irritated, and even betrayed by the frequent and often manipulative requests for favors, spare change, and loans of money. We worried about distorting our relationships by becoming patrons and buying friendship to obtain our research data. At the same time, we had to participate in the moral economy to avoid being ostracized from the network for being stingy and antisocial.

Homeless heroin users hustle everyone with whom they interact, fooling even themselves and betraying even their own bodies and desires. They are amazingly effective hustlers; if they were not, they could not continue to survive on the street. We had to learn, therefore, not to take their petty financial manipulations personally, and to refrain from judging them morally. Otherwise, we could not have entered their lives respectfully and empathetically. With time, we realized that there was nothing substantially different between how they extracted money from us and how they hustled everyone else in their network who had more resources than they at any particular moment. Gifts of money, blankets, and food were the primary means—aside from sharing drugs—they used to define and express friendships, organize interpersonal hierarchies, and exclude undesirable outsiders.

Participating in the moral economy allowed us to understand its importance on an embodied and intuitive level and revealed its social structural and public health implications. We had to become sufficiently immersed in the logics of hustling to be able to recognize, through an acquired common sense, when to give, when to help, when to say no, and when to be angry. We had to learn when to be spontaneously generous and when simply to walk away despite cries for help or curses of rage. Dogmatic rules for researchers with respect to giving money or doing favors for research subjects are out of touch with practical realities on the street. We, like the Edgewater Boulevard homeless, found ourselves more generous to those who reciprocated. The brute fact of the matter, however, is that homeless addicts are desperate for money, and, comparatively, we were rich. Nevertheless, they never took serious advantage of our generosity and our lack of “street smarts”; nor did they steal from us. Jeff occasionally left camera equipment in their camps. They had our phone numbers and addresses, and although Philippe lived only a few blocks from Edgewater Boulevard, they rarely contacted him or Jeff at home to ask for money or help.

Our approach to scenes such as the one presented in the fieldnotes and the photographs that follow is premised on anthropology’s tenet of cultural relativism, which strategically suspends moral judgment in order to understand and appreciate the diverse logics of social and cultural practices that, at first sight, often evoke righteous responses and prevent analytical self-reflection. Historically, cultural relativism has been anthropology’s foundation for combating ethnocentrism. For us, it has also been a practical way to gain access to the difficult or shocking realities of drugs, sex, crime, and violence. Unfortunately, public opinion on the subject of illegal drugs is so polarized in the United States that applying cultural relativism as a heuristic device to document the lives of drug users is often misconstrued as celebrating drug use. As will be evident, this is not the case in the pages that follow. Nevertheless, learning about life on the street in the United States requires the reader to keep an open mind and, at least provisionally, to suspend judgment.

It is sunrise, and Sonny comes by Hank’s camp to ask him for a favor: “Hit me in the neck.” Hank has a good reputation for administering jugular shots painlessly. On cold mornings like today, Sonny is unable to inject into the scarred, shrunken veins of his arms, hands, and legs. He refuses to inject into fatty or muscle tissue for fear of causing an abscess, so he seeks help. Although Sonny has woken him up, Hank agrees to fix him because he anticipates that Sonny will give him a taste of his heroin, and he has no money set aside for his own “morning wake-up shot.” Hank’s nose is already running, indicating that full-blown withdrawal symptoms are on their way.

Hank, consequently, eagerly takes out two syringes, teasing Sonny for being “up to no good” because Sonny has no needle, no cooker, no water, and no cotton filter in his possession. Hank is right. Sonny never carries injection paraphernalia for fear of police frisks when he goes out scavenging at night to burgle and/or recycle.

Sonny places his thumb in his mouth as if to suck it, but he blows on it instead in order to swell up his jugular vein. He puffs up like a blowfish, eyes bulging from their sockets, with his entire body shivering from the pressure on his thumb. Hank tells Sonny to stay still and probes the needle slowly into his neck. He has to be careful not to spear through the jugular into the artery located just behind it. Sonny whispers nervously: “Steady now; that’s right; you’re in. Go ahead! Come on!” Hank pulls back gently on the plunger, wiggling the syringe between attempts, causing Sonny to wince. Finally, on the third try, a plume of blood registers into the syringe chamber. Hank chuckles, “Moby Dick!” Sonny cautiously pulls his thumb out of his mouth, keeping it safely poised in front of his lips, and whispers, “Thar she blows!” But he does not smile. If Hank’s needle starts to slip while flushing the syringe into his jugular, Sonny will need to puff back up instantly.

The injection completed, Sonny massages his neck and rasps a soft thanks. His voice is already husky from the effects of the initial rush of heroin and he closes his eyes to appreciate it more fully. He points in slow motion toward the blackened bottle cap that served as their cooker. “The cotton is all yours, Hank.”

The liquid residue left over in the cotton filter from Sonny’s jugular injection fills only a tiny corner of Hank’s syringe chamber—less than ten of the units marked on the barrel of the syringe. Determined to suck out every last drop, Hank pinches the cotton between his nicotine- and dirt-stained fingers onto the tip of his needle as he gently pulls back on the plunger. This gives him five extra units.

Hank does not probe for a vein. Instead, he unbuckles his belt, lowers his pants, and jams his needle into the scarred cheek of his left buttock.

A police siren wails from two blocks away. We sit up nervously and Hank stashes the needles behind a bush, kicking the cooker into the dirt. But the siren passes and we relax. Sonny gives Hank two hugs.

Viewed on their own and out of context, jarring photographs of a jugular injection or of a cotton being pinched by filthy fingers on the tip of a syringe might confirm a negative stereotype or fuel a voyeuristic pornography of suffering that obscures the fuller context and meaning of what is occurring between Hank and Sonny. An analysis of the photograph together with the fieldnotes enables us to understand the pragmatic rationality for what at first sight may appear to be entirely self-destructive or immoral. More important, embedding the photograph in text allows an appreciation of the effects of social structural forces on individuals (Schonberg and Bourgois 2002). For example, the event can be interpreted as a moment of cross-ethnic solidarity in the moral economy. Hank is doing Sonny the favor of injecting him in the neck so that he can benefit from the more intense pleasure of the initial rush of a heroin high. Sonny is reciprocating Hank’s favor by treating him to the residue of his cotton, saving him from the pain of early-morning heroin withdrawal symptoms. In its opening and closing paragraphs, the preceding fieldnote excerpt also highlights the larger, systemic effect of law enforcement, revealing how fear of arrest exacerbates risky injection practices: discouraging possession of syringes, encouraging injectors to hide paraphernalia in unsanitary locations, and relegating the injection process to filthy hidden locales without running water. The note also documents preferences for injecting heroin either directly into a vein or into fatty tissue—an often-racialized phenomenon that we explore in chapter 3.

If our approach to the homeless is relativistic in the anthropological sense, we are nonetheless accutely aware of coercive forces and recognize the practical impossibility of cultural relativism in the “real world.” From a political perspective, law enforcement was our most immediate ethical concern. Initially, we feared that our mere presence might inadvertently draw police attention to our social network. In all our years on Edgewater Boulevard, however, this never occurred. We would have stopped the project immediately and desisted from publishing Jeff’s photographs had we thought we might significantly augment anyone’s risk of arrest or harassment.

The question of the personal privacy of our research subjects is more complicated than the immediate practical risk of legal sanctions against them, however. It involves the imperative to respect personal dignity and to avoid essentializing difference. The major characters in this book wanted to be part of our photo-ethnographic project. They gave Jeff permission to photograph and encouraged us to use their real names when they signed the bureaucratic informed consent documents required by our university’s internal review board overseeing research ethics. Arguably, however, this official “protection of human subjects” paperwork safeguards institutions from lawsuits rather than safeguarding the dignity and interests of socially vulnerable research subjects. Most important, the Edgewater homeless do not want to be treated as public secrets or hidden objects of shame. They struggle for self-respect and feel that their stories are worth telling.

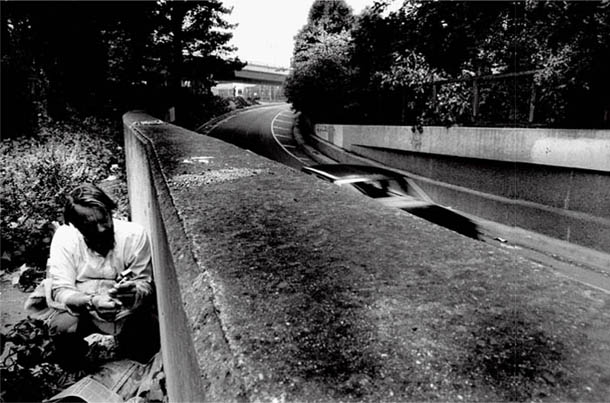

We ultimately decided to use pseudonyms but to reveal faces in our publications. Nickie provided the most succinct and eloquent argument for showing faces. We asked her how she felt about our displaying a photograph of her preparing an injection, with Petey in the foreground skin-popping into an abscess scar on his rear. She responded without hesitation: “If you can’t see the face, you can’t see the misery.”

There are surprisingly few examples of co-authored collaborative ethnographies in the history of anthropology, with the notable exception of works by married couples that too frequently have not acknowledged the intellectual contribution of the wife (for a critical review, see Ariëns and Strijp 1989; see also Mead 1970:326). The experience of the solo fieldworker in an exotic hamlet emerged as a rite of passage for anthropologists in the 1930s and 1940s (Gupta and Ferguson 1997; Stocking 1992). Collaborative fieldwork, however, can greatly improve ethnographic technique and analysis. Participant-observation is by definition an intensely subjective process requiring systematic self-reflection. Collaborators have the advantage of being able to scrutinize one another’s contrasting interpretations and insights.

In our case, we often purposefully conducted fieldwork together and wrote fieldnotes side by side in order to compare what we had seen, heard, and felt. Working together was also more fun and safer. We each developed a range of different kinds of relationships with the Edgewater homeless, allowing broader access to more people and generating distinct perspectives on the same individuals and events. Over the years, seven additional ethnographers (named in the acknowledgments) also assisted us for more limited periods, further diversifying our access to individuals and interpretations of events.

With the exception of the final half dozen drafts of text editing and tightening, we wrote the book sitting side by side. To maintain the intimacy of first-person ethnography and to communicate the significance of the effects of personalities and positionalities on social dynamics, we present several distinct voices throughout our text. In addition to our jointly written narrative and analysis, we identify our fieldnote excerpts in the first person (with occasional references to members of the “ethnographic team”). We also, of course, include the words and extended conversations of the homeless themselves. Conveying these distinct voices required a range of different grammatical and punctuation styles.

The photographs were all taken by Jeff. The composition of the images recognizes the politics within aesthetics; they are closely linked to contextual and theoretical analysis. Some photographs provide detailed documentation of material life and the environment. Others were selected primarily to convey mood or to evoke the pains and pleasures of life on the street. Most refer to specific moments described in the surrounding pages, but at times they stand in tension with the text to reveal the messiness of real life and the complexity of analytical generalizations. On occasion, the pictures themselves prompted the writing. Jeff never deliberately staged the actions portrayed in the photographs.

Jeff’s photography further integrated both of us into the scene. Many of the Edgewater homeless decorated their encampments with his pictures, and they often introduced Jeff to outsiders as “my photographer.” They usually introduced Philippe as “my professor” and would often comment to Philippe when he was alone with them, “Too bad Jeff isn’t here to take a picture of this.” When they viewed pictures of themselves, they were often shocked by their appearance—unhealthy, skinny, old, wrinkled, dirty, tired. This usually precipitated self-reflective conversations about the state of their lives (cf. Collier and Collier 1990). When Jeff showed Hank the photo of him standing with his American flag, Hank responded, “Ain’t that a shame! A goddamned Vietnam vet. Damn, look at how skinny I am. I look like Viet Cong. Y’know, when I put myself back together, I’m gonna help the homeless.”

Ethnography is an artisanal practice that involves interpretive and political choices. On the one hand, the researcher merges into the environment, relaxing into conversations, friendships, and interactions and participating in everyday activities. On the other hand, the observer is mentally racing to register the significance of what is occurring and to conceptualize strategies to deepen that understanding. We steered our conversations with the Edgewater homeless toward specific themes. When a particular topic or story appeared significant, we returned to it several times over the course of the years to obtain more substantive content and poetic depth.

“Truth” is, of course, socially constructed and experientially subjective; nevertheless, we did our best to seek it out. We reexplored important stories, statements, and topics, varying the surrounding conditions and the interviewers, using different members of the ethnographic team to triangulate for meaning and contextual or personal biases. We also controlled for differing states of intoxication and mood. Our fieldnotes and transcripts came to several thousand pages. Some of the dialogues presented in the text are, consequently, combinations of excerpts from multiple conversations with more than one ethnographer spread out over time. Whenever possible, we fact-checked official records for births, deaths, marriages, military service, employment, and incarceration; we also consulted newspaper articles and public archives to confirm the veracity of accounts of past events. When we documented notable discrepancies, we discuss their significance.

Editing street-based tape recordings is a literary and practical challenge with political and scientific implications. Oral discourse is a performative art, and written transcriptions lose the inflections and body language that punctuate speech (Gates 1988). The full meaning of colloquial language is lost when it is written down, and poetic passages often appear inarticulate when transcribed verbatim. Transcribing accents and pronunciation is especially problematic because a phonetic representation of language can distance readers from “cultural others.” Accents, however, convey important sociostructural differences with respect to class, ethnicity, education level, and segregation. In order to communicate patterns of cultural/symbolic capital without turning individuals into caricatures, we maintained some of the significant grammatical distinctions verbatim in our transcription, but we only selectively documented accents. To retain original meaning, clarity, and intensity of expression, we sometimes deleted redundancies and clarified syntax (see discussion of editing in Bourgois 2003b:354n.20). We were careful, however, to maintain what we believe was the original sense as well as the emotion of what was spoken and performed. (We did not use ellipses in quoted speech to indicate deleted words. Rather, ellipses indicate that the speaker is struggling to find the right word or is pausing to make a point or change the subject. We did, of course, use ellipses conventionally when quoting selectively from publications and archives.)

Our fieldnotes contain descriptions of more than two hundred core and peripheral individuals, and our understanding of the street scene draws from this larger array of relationships. However, to keep the text to a manageable length and to avoid a confusing array of names, we excluded most of the peripheral characters. Similarly, to preserve the flow of a conversation or a narrative and to avoid redundancy, we have sometimes moved characters around in time and space and abbreviated sequences of events. We have on occasion separated incidents and passages from long conversations or extended episodes into different thematic chapters when they illustrate distinct analytical points. Once again, we made these changes carefully (and hesitantly) to respect the integrity of human character and to maintain the full contextual meaning.

Ethnographers and photographers are conduits for power because they carry messages through different worlds and across class and cultural divides, but they also develop relationships of trust with individuals who generously let them into their everyday lives. Published accounts of those relationships inevitably risk objectifying and betraying this intimacy. Understandably, ethnographers generally desire to present positive images of the people they study. The stakes around negative images are especially charged when one explores the subject of drugs, crime, race, sexuality, poverty, and suffering in the United States; and we paid attention to those stakes when making our editorial choices, but we did not sanitize or distort (see Bourgois 2003b:355n.24). For example, comic aggressive teasing, role-playing, and posturing are performances in street settings that can translate into negative or mocking portrayals when they are converted verbatim into written text. Consequently, we have omitted some interactions that appeared excessively cruel or outrageously shocking and would have distracted from the analysis or misrepresented the fuller character of an individual. Most commonly, we deleted interpersonal insults and sexually explicit bravado. Harsh curses and racist and sexist epithets abound in the language of the Edgewater homeless. We omitted repetitive curses and epithets, but we included enough brutal material to convey the strong, and sometimes abusive, emotions surrounding the hierarchical power categories that organize interpersonal interactions on the street, most notably ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and physical appearance. We hope readers will not be distracted from analytical points when they are documented by graphic text, and we hope they will appreciate the acerbic, often comic, poetry of streetwise dialogues.

The camera, the tape recorder, and the written word are technologies that have historically lent themselves to surveillance and social engineering as well as to art and projects of solidarity. Documentary photography has an especially long and mixed record. It emerged out of social activism, journalism, fine arts, science, and pseudoscience—including phrenology, physiognomy, and eugenics—as well as out of public health and criminology (Sekula 1989; Tagg 1988).

Photography’s strength comes from the visceral, emotional responses it evokes. But the capacity to spark Rorschach reactions gives photography both its power and its problems (Harper 2002). Interpretation, judgment, and imagination move to the eyes of the beholder. The personality, cultural values, and ideologies of the viewer, as well as the context in which the images are presented, all shape the meaning of pictures (Berger 1972). The multitude of meanings in a photograph makes it risky, arguably even irresponsible, to trust raw images of marginalization, suffering, and addiction to an often judgmental public. Letting a picture speak its thousand words can result in a thousand deceptions (see Sandweiss 2002:326–333; Schonberg and Bourgois 2002). For this reason, we insist that without our text much of the meaning of the photographs we present could be lost or distorted. (For the classic critical portrayal of U.S. poverty combining photographs and text without captions, see Agee and Evans [1941] 1988; for different strategies of combining photographs and text depicting the U.S. inner city, see Duneier 1999; Goldberg 1995; Maharidge 1996; Richards 1994; Vergara n.d.; for a review of visual anthropology and “race,” see Poole 2005; see Barthes 1981 and Mitchell 1994:ch. 9 on the productive tension between denotation and connotation in photography and text.)

Like photography, ethnography has a mixed record of uses and abuses. It is saddled with cultural anthropology’s foundational predilection for community-based studies of exotic and dehistoricized others in a vacuum of external power relations (for a critique, see Wolf 1982). The discipline came of age in the twentieth century as a stepchild of colonialism and world wars and matured under the Cold War (Asad 1973; Nader 1997; Price 2004; Said 1989; Wolf and Jorgensen 1970). Participant-observation, however, has an inherently anti-institutional transgressive potential because, by definition, it forces academics out of their ivory tower and compels them to violate the boundaries of class and cultural segregation. Although it is framed by the unequal relationship of “investigator” and “informant,” ethnography renders its practitioners vulnerable to the blood, sweat, tears, and violence of the people being studied and requires ethical reflection and solidary engagement. At the same time, the all-encompassing vagueness of anthropology’s culture concept tends to essentialize difference and to obscure causal forces and negative consequences. The term culture is often applied sloppily across power gradients, inadvertently masking structures of inequality (Bourgois 2001a; Said 1989; Wolf 1982) and politically imposed physical suffering (Farmer 1992).

By arguing that social truth is an artifact of power, postmodern theory has humbled the totalizing enlightenment discourses that claim the moral authority to know what is best for others in the name of progress, science, and civilization. Our terms and categories of analysis and even our conceptions of reality are historical constructs. Consequently, there can be no transcendental solution to the contradictory tensions at the heart of both photography and ethnography. As representational practices they are torn between objectifying and humanizing; exploiting and giving voice; propagandizing and documenting injustice; stigmatizing and revealing; fomenting voyeurism and promoting empathy; stereotyping and analyzing. This book is especially vulnerable to ideological projections, because it confronts the social suffering of cultural pariahs through explicit text accompanied by images that expose socially taboo behaviors (drugs, sex, crime, and violence) and because it documents the politically and emotionally charged themes of race, gender, and indigent drug use (Schonberg and Bourgois 2002; see critique of the “bourgeois gaze” on the slums of Victorian England in Stallybrass and White 1986:ch. 3).

Silencing, censoring, and sanitizing photo-ethnographic critiques of suffering and inequality are not productive alternatives. Representing the Edgewater homeless solely as worthy victims for the sake of a positive politics of representation misrepresents the painful effects of marginalization, poverty, oppression, addiction, and violence. Following anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes’s call for a “good-enough ethnography” (Scheper-Hughes 1989) that critically engages the violence of everyday life despite a concern with the politics of representation, we advocate a “good-enough photo-ethnography” (Bourgois 1999). Photo-ethnography has the potential to effectively portray unacceptable social phenomena because it is more than the sum of its parts. It draws emotion, aesthetics, and documentation into social science analysis and theory and strives to link intellect with politics. Nonetheless, it is important to remain critically reflexive: What are we imposing? What are we missing? What are the stakes of exposure to a wider audience? Most important, however, there is urgency to documenting the lives of the Edgewater homeless. They survive in perpetual crisis. Their everyday physical and psychic pain should not be allowed to remain invisible.

The destructive manner in which the Edgewater homeless administer drugs to themselves and the central role of violence and manipulation in their interpersonal relationships raise the question of individual responsibility. On a practical level, we had to pay close attention to individual character traits while conducting fieldwork because we depended on the goodwill and cooperation of the homeless for protection. We had to figure out who to trust and who to avoid (as well as when to run). The homeless were also constantly evaluating one another’s personality traits in order to take advantage of individual weaknesses and to protect themselves from victimization. In short, interactions in everyday life operate on the basis of what academics call “agency.” The conventional theoretical distinction between structure and agency, however, is too binary a conception to explain why people do what they do. It equates incommensurable units of analysis in a moral calculus that reflects ideological debates rather than offering insight into complex historical and contemporary outcomes. To avoid the theoretical impasse of conventional structure-versus-agency debates, we have framed this book around a concept that we call “lumpen abuse.”

In popular parlance, the term abuse generally refers to interpersonal relations or actions that contravene the norms of social interaction and violate an individual’s human rights. The word abuse implies outrageous suffering—emotional, psychological, and/or physical. The definition in the Oxford English Dictionary includes, among other historical synonyms, “wronged,” “worn out, consumed by use . . . obsolete,” “chronic corrupt practice,” “deceit, delusion,” “violation.” The entry also makes reference to “drug abuse.” Finally, the dictionary definition specifies that, in modern use, the term refers “esp[ecially to] sexual or other maltreatment.” The index of the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual (1994: 875) lists two primary sets of entries for abuse: one is grouped around substance abuse, and the other is divided into several subheadings that include neglect as well as physical and sexual mistreatment of children and adults.

The medical and popular resonances of the word abuse are useful analytically because they call attention to the misuse of power in intimate relations that conjugates victims with perpetrators in a trauma of betrayal over an extended time period. Our theorization of abuse sets the individual experience of intolerable levels of suffering among the socially vulnerable (which often manifests itself in the form of interpersonal violence and self-destruction) in the context of structural forces (political, economic, institutional, cultural) and embodied manifestations of distress (morbidity, physical pain, and emotional craving). Close ethnographic explorations of suffering must address its social distribution (Kleinman, Das, and Lock 1997; Kleinman and Kleinman 1991). The suffering of homeless heroin injectors is chronic and cumulative and is best understood as a politically structured phenomenon that encompasses multiple abusive relationships, both structural and personal. Our exploration of drug consumption, domestic violence, sexual predation, interpersonal betrayals, and interpersonal hierarchies examines these abusive phenomena in their relationship to political-economic, cultural-ideological, and institutional forces, such as the restructuring of the labor market, the “War on Drugs,” the gentrification of San Francisco’s housing market, the gutting of social services, the administration of bureaucracies, racism, sexuality, gender power relations, and stigma.

Linking suffering to power through a theory that analyzes the multiple levels of lumpen abuse coincides with redefining violence as something more than a directly assaultive physical and visible phenomenon with bounded limits. Violence operates along a continuum that spans structural, symbolic, everyday, and intimate dimensions (Bourgois 2001b; Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois 2004). Structural violence refers to how the political-economic organization of society wreaks havoc on vulnerable categories of people (Farmer 2003). Scheper-Hughes began using the term everyday violence to call attention to the social production of indifference in the face of institutionalized brutalities. She reveals, for example, how the “invisible genocide” of infants dying of hunger in the Brazilian shantytown where she was living was routinized and legitimized by the rituals of bureaucracies, the banal procedures of medicine, and the religious consolation of the mothers who were her neighbors and friends (Scheper-Hughes 1996). We extend her concept to call attention to the effects of violence in interpersonal interactions and routine daily life. Recognizing the phenomenon of everyday violence and documenting how intimate violence interfaces with structural violence counteracts the marxist tendency toward linear economic determinism. But participant-observation of everyday interpersonal violence presents a theoretical problem. Ethnography is attuned to fine-grained observations of individuals in action; it tends to miss the implications of structures of power and of historical context because these forces have no immediate visibility in the heat of the moment.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence links immediate practices and feelings to social domination (Bourdieu 2000). It refers specifically to the mechanisms that lead those who are subordinated to “misrecognize” inequality as the natural order of things and to blame themselves for their location in their society’s hierarchies. Through symbolic violence, inequalities are made to appear commonsensical, and they reproduce themselves preconsciously in the ontological categories shared within classes and within social groups in any given society. Symbolic violence is an especially useful concept for critiquing homelessness in the United States because most people (including the Edgewater homeless themselves) consider drug use and poverty to be caused by personal character flaws or sinful behavior. We hope to deconstruct the generalized misrecognition of the ways everyday, intimate, and structural violence generate (and are legitimized by) symbolic violence. In summary, we are combining and reshaping the approaches to power of Marx, Bourdieu, and Foucault in order to weave the concepts of politically structured suffering and the continuum of violence into a theory of lumpen abuse.

As a political economist critiquing capitalism, Karl Marx considers the economic relations that organize social classes to be key to explaining power relations, and he identifies class struggle as the motor force of history (Marx and Engels [1848] 2002). Accordingly, he would have summarily dismissed the Edgewater homeless as members of the lumpen proletariat. Marx defines the lumpen as a residual class: the historical fall-out of large-scale, long-term transformations in the organization of the economy. Members of the lumpen have no productive raison d’être. Expelled from engagement with the means of production, they become drop-outs from history. They are too marginal to be part of what Marx calls “the reserve army of the unemployed” that factory owners draw upon to undermine unions and lower wages. In one of his more polemical passages, Marx refers to the lumpen as the “scum, offal, refuse of all classes” (Marx [1852] 1963:75). (For discussions of Marx’s attitude toward the lumpen, see Bovenkerk 1984; Bussard 1987; Draper 1972; Parker 1993; see Stallybrass 1990 on bourgeois representations and fantasies of the lumpen.) To understand the human cost of neoliberalism in the twentieth century, we are resurrecting Marx’s structural sense of the lumpen as a vulnerable population that is produced at the interstices of transitioning modes of production. We do not, however, retain his dismissive and moralizing use of the term lumpen.

Bourdieu considers social class and the economic field of power to be of paramount importance, but he is most concerned with the way hidden forms of symbolic power maintain and legitimize hierarchy and oppression through everyday “practice.” He develops the concept of “habitus” to show how social structural power translates into intimate ways of being and everyday practices that legitimize social inequalities. Habitus refers to our deepest likes, dislikes, and personal dispositions, including those of our preconscious bodies. It is grounded historically in the collective frameworks of culture and society, misrecognized as “instinct,” “common sense,” or “character,” which becomes the basis for how we feel things and why we act. Most important, although every individual’s habitus is unique, modulated by serendipity and individual charisma and constantly changing over the course of a lifetime, it also contains biographical and historical sediments filtered through past generations (Bourdieu 1977, 2000; Wacquant 2005).

We draw on Michel Foucault’s understanding of power and normativity in order to better understand how the structural phenomenon of lumpenization is enmeshed in symbolic violence. According to Foucault, the locus of state power in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shifted from a logic of “sovereignty,” which exacts obedience through bloody repression, to one of “biopower,” which promotes the health and well-being of citizens (Foucault 1978:140–144). The mechanisms of control shifted from coercive terror and torture to an internalized self-disciplinary gaze that responsible individuals impose on their bodies and psyches as a moral responsibility. In Foucault’s conception, power is not wielded overtly, but rather “flows” through the very foundations of what we recognize as reason, civilization, and scientific progress. It operates through processes of governmentality that may continue to include physical repression but are primarily organized around monitoring and regulating large population groups through broad interventions such as vaccination campaigns and censuses. Individuals are disciplined purposefully and explicitly through institutions, but also subtly and unconsciously through the “knowledge/power” nexus. The applied academic, medical, and juridical scientific disciplines (such as public health, criminology, social work, and psychiatry) emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to define modernity, progress, truth, and ultimately self-worth: the docile bodies of healthy and “normal” citizens are shaped through responsible scientific knowledge and progress.

Nothing can escape the effects of power as conceived by Foucault. Capillary-like, these effects infuse our bodies and minds to set the agendas of our lives and to shape even our most oppositional thoughts. Distinct “subjectivities” emerge as patterns of historically situated ways of perceiving and engaging with the world. Unlike the term identity, the concept of subjectivity does not imply individual agency or self-ascription. It treats taken-for-granted characteristics such as demographic profile or psychological temperament as discursive products of modernity rather than innate categories. The French terms for subjectivity, assujetissement and subjectification, carry the clear implication of the “process of becoming subjected to a power” (see Deleuze 1995:81–118 on “subjectification”; see also Butler 1997:83 on “subjectivation”). For Foucault, subjectivity is a “soul that imprisons the body” (Butler 1997:86, citing Foucault 1995; see also Pine 2008:12–14, 17). It emerges through the knowledge/power nexus and is part of the disciplinary and security processes of governmentality (Foucault 1978, 1981a, 1995). Foucault did not examine illegal drug use, but the topic of “substance abuse” is ideal terrain for a critical application of biopower, governmentality, and the deconstruction of knowledge/power discourses.

Our theory of lumpen abuse highlights the way structurally imposed everyday suffering generates violent and destructive subjectivities. The version of punitive, corporate neoliberalism that has been spreading unevenly across the globe in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries as the dominant mode of production is producing growing numbers of lumpenized populations (see Ferguson 2006:39–40 on “Afrique inutile”). Biopower as a form of governmentality that is productively internalized by citizens may have characterized social democracy and capitalist fordism, but violent coercion (including state and parastate terrorism and war) increasingly characterizes neoliberal forms of governmentality. Bringing Foucault to bear on Marx, we are redefining the class category of lumpen as a subjectivity that emerges among population groups upon whom the effects of biopower have become destructive (Bourgois 2005a). The term lumpen, consequently, is best understood as an adjective or modifier rather than as a bounded class category. The lumpen subjectivity of righteous dopefiend that is shared by all the Edgewater homeless embodies the abusive dynamics that permeate all their relationships, including their interactions with individuals, families, institutions, economic forces, labor markets, cultural-ideological values, and ultimately their own selves.

The autobiographical literature created by Holocaust survivors provides exceptional insight into how state coercion can make monsters of the meek. Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi developed the concept of the “Gray Zone” to capture the ethical wasteland imposed by the Nazis on concentration camp inmates struggling to stay alive under genocidal conditions (Levi 1988). In the Gray Zone, survival imperatives overcome human decency as inmates jockey desperately for a shred of advantage within camp hierarchies, striving to live just a little bit longer. The Nazis purposefully engineered the Gray Zone of the death camps to force inmates to self-administer to one another, with excruciating cruelty, the logistics of everyday life in the camps. As a contemporary ethical imperative, Levi urges readers to recognize the less extreme gray zones that operate in daily life, “even if we only want to understand what takes place in a big, industrial factory” (1988:40).

As with the concept of violence, we find it useful to think of gray zones in contemporary society as operating along a continuum of insupportable, structurally imposed settings. This perspective renders more visible the complex interaction between intimate behavior and larger coercive constraints. The homeless encampments along Edgewater Boulevard are obviously not equivalent to Nazi death camps. The Edgewater homeless sometimes quip, “No one put a gun to my head and made me shoot heroin.” Their lives also often contain camaraderie, humor, and the joy of living. Nevertheless, addiction under conditions of extreme poverty and concerted police repression creates a morally ambiguous space that blurs the lines between victims and perpetrators. By extending the boundaries of the Holocaust’s Gray Zone to the everyday world around us, we can understand the Edgewater homeless as surviving along an especially coercive and desperate swath of the gray zone continuum.

Levi and other survivors assert that we do not have the right to judge the actions of inmates in the concentration camps because the Gray Zone was omnipotent (Levi 1988; Steinberg 2000). He implicitly contradicts himself, however, by devoting much of his writing to eloquently dissecting the moral dilemmas of human agency at Auschwitz through detailed descriptions of individual behaviors, decisions, and interpersonal betrayals (see discussion in Bourgois 2005b). Following Levi, we explore the agency and moral responsibility of the homeless addicts we befriended without obscuring the structural forces that impose a gray zone. We examine in detail the micro-level mechanisms through which externally imposed forces operate on vulnerable individuals and communities.

Levi’s insistence that we learn from the Holocaust in order to recognize the structural injustices that pass for business as usual in normal times is consistent with anthropologist Michael Taussig’s reading of Walter Benjamin’s theory of history. Benjamin was also a victim of Nazi repression for being a Jew (and a marxist). Shortly before committing suicide while trapped on the French border with Spain at the outbreak of World War II, he warned that most people fail to see the everyday “state of emergency” in which the socially vulnerable are forced to live (Benjamin [1940] 1968:257; see also detailed analysis by Taussig [1984, 1992] of the “space of death” and the “culture of terror” created by the Argentinean and Colombian states in the 1970s and 1990s and by the international rubber trade in the Amazon in the late nineteenth century).

Significantly, Benjamin was also excited about the potential of photography to foster a “politically educated eye” by provoking a “salutary estrangement” from one’s surroundings. He distrusted the “free-floating contemplation” of pictures, however, and was worried by the capacity of a sentimental use of photography and film in fascist Europe to seduce viewers with pretty pictures of a modernity that was increasingly brutal (Benjamin [1931] 1979:251). He admired Eugene Atget’s photographs of everyday Paris—deserted, hard, and ordinary, nothing like the city’s “exotic romantically sonorous” name. Consistent with his awareness of living in a perpetually misrecognized state of emergency, he noted, “Not for nothing have Atget’s photographs been likened to those of the scene of a crime. But is not every square inch of our cities the scene of a crime? Every passer-by a culprit?” (Benjamin [1931] 1979:257; see also [1936] 1968:226). Ultimately, he argued, the way a photograph is “inscribed” in text and context or circulated as an object determines whether it will function as a reactionary “journalistic tool” or as a means to expose social relations: “Won’t inscription become the most important part of the photograph?” (Benjamin [1931] 1999:527; see also discussions in Edwards and Hart 2004).

The book is written as a chronological narrative of the everyday lives of a dozen main characters (and another half dozen additional peripheral individuals) whom we followed for over a decade. We have organized the chapters around analytical themes related to the power relations and historical and institutional forces that shape their lives. Chapter 1, “Intimate Apartheid,” addresses ethnic polarization and introduces most of the core members of our social network on the street. It also documents the ambiguous process of becoming homeless. We use the concept of “intimate apartheid” as a way to understand the enforcement of a racialized micro-geography of homeless encampments. Hostile social boundaries arise through intense interpersonal multiethnic proximity and forced mutual dependence rather than through the neighborhood-wide patterns of segregation that predominate in most of the urban United States.

The second chapter, “Falling in Love,” explores gender relations on the street and the continuum between romantic love and sex work. It features the life of a charismatic woman, Tina, who grew up in poverty and violence with an unstable mother and no support from her father. In her middle age on Edgewater Boulevard, Tina attempts to carve out autonomy in her outlaw partnerships with Carter, but instead reproduces patriarchal arrangements through her search for romance, trust, and dignity.

The next five chapters address the body, childhood socialization, the legal labor market, experiences of parenthood, and male sexuality. Chapter 3, “A Community of Addicted Bodies,” traces how physical and emotional dependence on heroin creates a morally bounded social network that allows clearly demarcated interpersonal hierarchies and personal agency in the construction of self-respect. From a social structural perspective, we examine how race and social marginalization become painfully inscribed on the bodies of homeless drug users and alcoholics. We critique public health and emergency hospital services and present explicit details of the painful and gruesome experience of everyday filth and infection among indigent heroin injectors. Most important, we emphasize the many ways in which the government’s War on Drugs has exacerbated the physical and psychological harms of drug use and the overarching pain of the pariah homeless status. The chapter concludes with a close look at the routine experience of chronic physical and emotional suffering, ranging from hunger, cold, and filth to everyday interpersonal and institutional violence.

Chapter 4, “Childhoods,” explores the ongoing kinship relations and diverse childhood experiences of the members of our social network, from violent and/or sexually predatory to neglectful or nurturing. The families of the African-American, Latino, and white men and women we befriended have dealt with addiction and homelessness in very different ways. We also set the Edgewater homeless in their historical epoch: they came of age in a working-class San Francisco neighborhood of single-family homes in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the epicenter for a youth culture that revolved around drugs, sex, rock ’n’ roll, opposition to the Vietnam War, and rejection of middle-class values.

Chapter 5, “Making Money,” examines income-generating strategies. We begin by analyzing the disappearance of industrial jobs in San Francisco and document the impact of this economic restructuring on men and women who did not adapt to the new service-based and high-tech economy that has made the San Francisco Bay Area one of the richest and most expensive regions in the United States. We show how the homeless survive in this wealthy environment through constantly shifting combinations of manual labor, panhandling, scavenging, welfare, and petty crime.

Chapter 6, “Parenting,” describes the relationships of the Edgewater homeless with their children and explores the limits of identifying moral responsibility for long-term patterns of traumatic transgenerational relationships. The notion of a continuum between victim and perpetrator permeates much of the book (especially chapters 2 and 4), but it is portrayed most vividly here, along with an understanding of the patriarchal channeling of psycho-affective trauma around domestic violence.

Chapter 7, “Male Love,” follows a long-term male running partnership to explore the phenomenon of homosocial love relationships among resolutely homophobic men. This chapter further documents the harmful effects of law enforcement on bodies and psyches and offers a detailed critique of the dysfunctional U.S. medical system, driven by market forces and retrenchment of public services. We revisit the painful topic of decaying bodies (explored in chapter 3) and raise the ante by confronting the large-scale phenomenon of premature aging among the homeless in the United States as a result of lifetimes of poverty and chronic drug, alcohol, and cigarette consumption. In this case, the county hospital in San Francisco provides excellent, expensive, high-tech medical services and has a dedicated, politically progressive medical staff. Unfortunately, the medical care is delivered in the glaring absence of community-based, low-tech social support services for the chronically infirm.

The last two chapters continue the narrative of the outlaw romantic couple described in the opening two chapters, Tina and Carter. Chapter 8, “Everyday Addicts,” is written in an experimental style as a series of extended fieldnotes and conversations in order to convey, with greater texture and intimacy, the serendipity of daily life on the street. We evoke the passage of real time, showing how anxiety, excitement, fun, violence, and banality are interwoven. We also provide a glimpse of the wider range of peripheral characters in the Edgewater scene. The Bonnie-and-Clyde love affair between Tina and Carter ends in chapter 9, “Treatment,” with an account of their attempts to quit heroin. This final chapter also describes experiences of treatment and recovery by other core members of our social network.

In our conclusion, “Critically Applied Public Anthropology,” we propose short-term pragmatic policy recommendations and discuss the structural political and economic changes necessary for the longer-term improvement of the lives of the indigent poor in the United States. We end with a theoretical discussion of our current moment in history, at the turn of the twenty-first century, when people like the Edgewater homeless represent the all-American tip of an iceberg, overshadowing an ever-larger proportion of the world’s population who, beginning in the early 1980s, have been politically and economically excluded by the imposition of U.S.-style neoliberal policies across the globe (Harvey 2005). In a nutshell, services for vulnerable populations have been dismantled in favor of a punitive model of government that has expanded investment in prisons, police forces, and armies while promoting income inequality and corporate subsidies.

Abuse in all its inevitably intertwined forms—institutional, political, structural, psychological, and interpersonal—is ugly. We present the full controversial range of behaviors and beliefs of the Edgewater homeless in these pages in order to convey the urgency of addressing their suffering pragmatically and humanely. Most important, we provide a critical means for theorizing the effects of power in our neoliberal era. The intellectual debates addressing poverty, addiction, and individual responsibility in the United States need to break out of the confines of moral judgment. The Edgewater homeless deserve to be taken seriously for who they are and not for who we want them to be. We believe that they tell us a great deal about the United States, and they alert us to the challenges the world faces in the early twenty-first century.