Chapter 3. Elements That Are New in HTML5

HTML5 provides us with new and mostly semantic elements; it redefines

some existent elements and makes other elements obsolete (think of

“obsolete” as the new, politically correct version of “deprecated”). As we

saw in Chapter 2, we have the root <html> element, document metadata described

in the <head> section, and

scripting elements. HTML5 provides us with sectioning elements, heading

elements, phrase elements, embedded elements, and interactive elements.

Interactive form elements are covered in Chapter 4.

The media-related embedded elements will be discussed in Chapter 5. We won’t discuss table

elements, since, for the most part, they haven’t changed in HTML5. The other

elements are discussed in the next section.

In prior specifications, elements were described as being either inline, for text-level semantics, or block, for flow content. HTML5 doesn’t use the terms block or inline to describe elements anymore. The HTML5 authors correctly assume that CSS is responsible for the presentation, and all browsers, including all mobile browsers, come with stylesheets that define the display of elements. So, while HTML5 no longer defines elements in terms of block or inline, the default user-agent stylesheets style some elements as block and others as inline, but the delineation has been removed from the specification.

With HTML5, we have most of the HTML 4 elements and the addition of a few new ones. HTML5 also adds several attributes and removes mostly presentational elements and attributes that are better handled by CSS. In Chapter 2, we covered the new global attributes. In this chapter, we cover many of the new elements of HTML5, and some of the existent elements that have had major changes. Other elements such as form and embedded content elements will be discussed in their own, separate chapters.

Sectioning Elements in HTML5

The sectioning root is the <body>

element. Other HTML 4 sectioning elements included in the HTML5 spec are

the rarely used <address> element

and the leveled headings from <h1> to <h6>. HTML5 adds several new sectioning

elements, such as:[21]

sectionarticlenavasideheaderfooter

It also maintains support for these older sectioning elements:

bodyh1–h6address

The new sectioning elements encompass content that defines the scope

of headings and footers. The new sectioning elements, like <footer>, <aside>, and <nav>, do not replace the <div> element, but rather create semantic

alternatives. Sectioning elements define the scope of headings and

footers: does this heading belong to this part of the page or the whole

document? Each sectioning content element can potentially have its own

outline. A sectioning element containing a blog post, for example, can

have its own header and footer. You can have more than one header and

footer in a document. In fact, the document, each section, and even each blockquote can have its own footer. Because each section has its own scope

for headings, you are not limited to a single <h1> on a page, or even limited to six

heading levels (<h1> through

<h6>). Let’s cover the new

sectioning elements.

The authors of HTML5 scanned billions of documents, counting each

class name, to determine what web developers were calling the various

sections of their page. Opera repeated the study, including the names of

IDs in addition to class names. Due to Dreamweaver and Microsoft Word,

style1 and MsoNormal were very, very popular. Ignoring the

software-generated classes and obviously presentational class names like

left and right, they discovered that web developers were

using semantic sectioning names like main, header,

footer, content, sidebar, banner, search, and nav almost as if they were included in a default

Dreamweaver template (they weren’t).

Reflecting what developers were doing, more than 25 new elements

have been added to HTML5. Originally missing was the “main” or “content”

elements. The reason? Anything that is not part of a navigation, sidebar,

header, or footer is part of the main content. The <main> element is a late addition to the

specification, and is described .

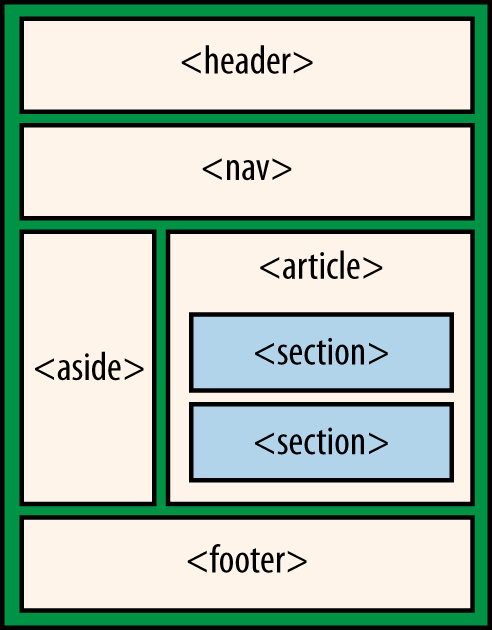

Using the new elements, like <header> and <footer>, which replace and make more

semantic the semantically neutral <div

id="header"> and <div

id="footer">, we can create the standard web layout in a more

semantic way. These new elements, shown in Figure 3-1 in what is a common

page layout, enable including semantics to the layout of a

document.

<section>

The <section> element

can be used to thematically group content, typically with

a heading. The <section>

element represents a generic document or application section, but is not

a generic container element: it has semantic value. If you are simply

encompassing elements for styling, use the nonsemantic <div> instead:[22]

<section>

<header>

<h1>Mobile Web Applications with HTML5 and CSS3 </h1>

</header>

<h2>HTML5</h2>

<p>Something about HTML5.</p>

<h2>CSS3</h2>

<p>Something about CSS3.</p>

<footer>Provided by Standardista.com</footer>

</section><article>

The <article> element is

similar to <section>, but like a news article, it

could make sense independent of the document or site in which it is

found. The <article> is a

component of a page that consists of a self-contained composition in a

document, page, application, or site that is intended to be

independently distributable or reusable, such as for syndication:

<article>

<header>

<h1> Mobile Web Applications with HTML5 and CSS3 </h1>

<p><time datetime="2013-11-11T12:31-08:00">11.11.13</time></p>

</header>

<h2>HTML5</h2>

<p>Something about HTML5.</p>

<h2>CSS3</h2>

<p>Something about CSS3.</p>

<footer>

<p>Provided by Standardista.com</p>

</footer>

</article>Originally, the HTML5 specifications included a Boolean pubdate attribute, but that has been removed

from the specification, as microdata vocabulary can be used to provide

such information.

<section> Versus <article>

There is some debate in the spec-writing community that these two

elements are too similar. You should use <article> versus <section> when the encapsulated content

is a discrete item of content. It is often a judgment call. The only

difference in the two code snippets given in the previous two sections

is that I’ve added an optional <time> to the <article> example.

In terms of explaining the similarities, differences, and functionalities of these two elements, use the analogy of the Sunday newspaper (for those of you too young to remember what a newspaper is, it’s that thing you recycle or start chimney fires with). The Sunday newspaper has several sections: the front page, news, real estate, classified, weekly magazine, comics, and so on. Each of these sections has articles. Those articles have headers, and some, especially in-depth news reports, have nested sections. Similar to the Sunday paper, articles and sections can be nested within each other and within themselves.

An <article> can be a

forum post, a magazine or newspaper article, a blog entry, a

user-submitted comment, an interactive widget or gadget, or any other

independent item of content.

The general rule is that the <section> element is appropriate only if

the element’s contents can be listed explicitly in the document’s

outline, such as saying “the ‘<section> versus <article>’ section is in this book.” The

HTML5 sections grouping you are reading right now would be in a <section> tag if it were online.

Examples of sections would be chapters, the various tabbed pages in a tabbed dialog box, or the numbered sections of a thesis. A website’s home page could be split into sections for an introduction, news items, and contact information.

Authors are encouraged to use the <article> element instead of the

<section> element when it makes

sense to syndicate the contents of the element.

<nav>

The <nav> element

is used for major navigational blocks within a document,

providing for a section of a page that links to other pages or to parts

within the page. By major or main navigation, think drop-down menus or

other large groups of links that a visitor to your site using a screen

reader may want to skip listening to on their way to hearing the main

content of your page.

Small groups of links, like legalese and other links often found

in the footer, can be encapsulated in the <footer>. If your <footer> has a large navigational

section, you can nest a <nav>

in it.

By encapsulating your site navigation in the <nav> element, you are telling sightless

readers (think visually impaired, but also think searchbots like

Google’s spiders) that this is the navigation to your site. When the

<nav> element becomes well

supported by screen readers, we will be able to stop including “skip

navigation” links that we’ve been using for accessibility. If you want

to provide for additional accessibility right now, use the WAI-ARIA

role="navigation":

<nav role="navigation">

<ul>

<li><a href="/">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="/css/">CSS3</a></li>

<li><a href="/html/">HTML5</a></li>

<li><a href="/js/">Javascript</a></li>

<li><a href="/access/">Accessibility</a></li>

</ul>

</nav><aside>

The <aside> contains

content that is tangentially related to the main content:

related enough to be taken out of the flow, but not actually part of the

content. The <aside> content is

separate from the main content, and can be used for typographical

effects like pull quotes or sidebars, for advertising, for groups of

navigational elements, and for other content that is considered separate

from, including tangentially related to, the main content of the page.

Basically, if you can pull the <aside> out of the page, and the main

content still makes sense, you’re using the element correctly.

<aside> content does not

need to be relegated to the sidebar. For example, when the bottom

section of your document contains more than footer-type content,

creating what is called a fat footer, you can put

your <aside> at the bottom of

the page instead of or in addition to a <footer>:

<section>

<h1>......</h1>

<!-- main content of page -->

<section>

<aside>

<dl>

<dt>HTML5</dt>

<dd>The next major revision of the HTML standard.</dd>

</dl>

</aside><header>

The <header> groups

introductory or navigational aids and contains the

section’s heading (an <h1>–<h6> element), but this is not required.

The <header> element can also

be used to wrap a section’s table of contents, a search form, or any

relevant logos: basically, anything that makes up a header.

There can be more than one <header> on a page: the main <header> for the document, containing

the logo, the main navigation, and the titles of your site and login,

and separate <header> elements

for each <section> and/or

<article> code blocks. For

example, your blog may have a document header with logo, search,

tagline, and main navigation in the main <header>, with a separate <header> element for each blog post for

the post title, author, and publication date.

Note

Think of the <header>

as a semantic replacement for the main <div id="header"> and the multiple

section headings <div

class="heading"> of yore.

<footer>

The <footer> element

typically contains information about its section or

article, such as who wrote it, links to related documents, copyright

data, and more. Like the <header>, you can have more than one

<footer> in a document: one

representing the global footer, and other <footer> elements for each individual

<section> and/or <article>, such as social networking

links and a link to comments at the bottom of each post in a

blog.

The <footer> element

should encompass the footer for the nearest ancestor sectioning content.

Similar to the <header>, each

<footer> will be associated

with the nearest ancestor <article>, <section>, or <body>. If the closest parent sectioning

content is <body>, then the

<footer> represents the footer

for the whole document, replacing the formerly ubiquitous <div id="footer">, and adding semantic

meaning.

Author contact information belongs in an <address> element (described

momentarily), which can be in a <footer>. Footers don’t have to be at

the end of a document or article, though they usually are. Footers can

also be used for appendixes, indexes, and other such content:

<footer>

<p>Copyright 2013

<address>estelle@standardista.com</address>

</p>

</footer>Note that the footer and aside are slightly different sectioning

elements: the headers of your <footer>s and <aside>s will not be included in the

outline for your document.

CubeeDoo Header and Footer

With games on mobile devices, we want to provide as much room as possible for the board. However, if our users have a desktop screen, we have all this extra room! So, depending on browser size, we include a header and footer above and below the game in larger screens:

1 <article> 2 <header> 3 <h1>CubeeDoo</h1> 4 <h2>The Mobile Memory Matching Game</h2> 5 </header> 6 <section id="game" class="colors"> 7 <div id="board" class="level1"> 8 <!-- game board goes here --> 9 </div> 10 <footer> <!-- footer for the section --> 11 <div class="control scores">Scores</div> 12 <div class="control menu" id="menu">Menu</div> 13 <ul> 14 <li id="level">Level: <output>1</output></li> 15 <li id="timer"> 16 <div id="seconds"></div> 17 </li> 18 <li><button id="mutebutton">Mute</button></li> 19 <li id="score">Score: <output>0</output></li> 20 </ul> 21 </footer> 22 </section> 23 <footer><!-- footer for the article --> 24 <ul> 25 <li><a href="about/estelle.html">About Estelle</a></li> 26 <li><a href="about/justin.html">About Justin</a></li> 27 </ul> 28 </footer> 29 </article>

We’ve contained our page in an <article> with the game (lines 6–22) a

<section> nested within that

article. The document has a <header> (lines 2–5) and <footer> (lines 23–28). In the article

header, we have a title and a subtitle marked up as an <h1> and <h2>. The page has two footers. In

addition to the document footer that is relevant and is visible in all

the pages on our site, there is also a <footer> (lines 10–21) for the game’s

main screen that is encapsulated in a <section>.

Not New, but Not Often Used: <address>

The <address> element is

not new to HTML5. It’s been around for a while, and is well

supported, being rendered in italic by most user agents. Almost no

developers implement it, so I’m reminding you about its existence here.

And, no, the <address> element

is not for your contact information.

Unlike many elements, the semantics of <address> aren’t completely obvious.

Actually, it’s quite nuanced. The <address> element represents the

“contact information for its nearest article or body element ancestor.”

If that is the <body> element,

then the contact information applies to the document as a whole. If it

is an <article>, then the

address applies to that article only. Basically, it’s not meant for your

street address on your contact page, which would seem to make

sense.

Grouping Content: Other New HTML5 Elements

Most of the formerly block-level elements have been divided into sectioning and

grouping elements. The grouping set of elements includes lists, <p>,

<pre>, <blockquote>, and <div>. We have three new elements,

<main>, <figure>, and <figcaption>. The <hr> element has been provided with semantic meaning in HTML5, so has been

included under the new category because the old <hr> had no semantic meaning and didn’t

group anything (see Table 3-1).

New grouping elements | Older grouping elements |

|

|

We’ll only cover the new grouping elements and changes to the older grouping elements, as you should already be familiar with the existent ones.

<main>

The <main> element

defines the main content of the page. Because it’s the main

content of the page, the <main>

must be unique to the page. The <main> element is not sectioning content

like the elements just described, and therefore has no effect on the

document outline. <main> should

encompass the content that is unique to the page and exclude site-wide

features like the site header, footer, and main navigation.

Being the main content, it can be the ancestor but not the

descendant of articles, asides, footers, headers, and navigation

sections. No, I did not just contradict myself. Using the example of a

blog, the <main> would

encompass the blog posts, along with the post’s header and footer, but

would not encompass the site-wide header, footer, navigation, and

aside.

<figure> and <figcaption>

The <figure> element

encompasses flow content, optionally with a <figcaption> caption, that is

self-contained and is typically referenced as a single unit from the

main flow of the document.

OK, that was totally W3C-speak. Lay terms? You know how you’re always struggling with how to include an image with a caption? You now have a semantic way to do it.

The <figure> element

should be used on content that, if removed, would not affect the meaning

of the content. For example, most of the chapters in this book have had

tables and figures with captions. Had we removed those images, this

content might be more difficult to digest, but the flow of the text

would not be affected. Those figures would be perfect candidates for the

<figure> element:

<figure>

<img src="madeupstats.jpg" alt="Marketshare for chocolate

in the USA is 27% dark chocolate, 70% milk chocolate,

and 3% white chocolate." />

<figcaption>Browser statics graph by chocolate type</figcaption>

</figure>In the preceding example we used both <figure> and <figcaption>, and bogus

statistics.

Only found as the first or last child of a figure element, the

<figcaption> is a caption or

legend for the rest of the contents of the <figure> it’s nested in. The inline

contents of the <figcaption>

provide a caption for the contents of its associated <figure>.

<hr>

The empty <hr> element

has garnered new semantic meaning in HTML5. Whereas it used to

be defined purely in presentational terms, a horizontal rule, it has

been given the semantic purpose of representing a “paragraph-level

thematic break” or “hard return.” The <hr> is useful to delineate scene

change, or a transition to a new topic within a section of a

wiki.

The element-specific attributes of the <hr/> element have all been

deprecated.

<li> and <ol> Attribute Changes

In addition to the global and internationalization changes described in Chapter 2, the value attribute on list items and the type

attribute on ordered lists, deprecated in previous specifications,

have returned. In addition, the Boolean reversed

attribute has been added to ordered lists, reversing the order of the

numbers and enabling descending order.

Text-Level Semantic Elements New to HTML5

There are more than 20 text-level semantic elements in HTML5. Some of these

elements are new, some have been repurposed, some have attribute changes,

some have remained the same, and a very few, like <acronym>, have been removed from the specification altogether. The elements

are shown in Table 3-2.

New | Changed | Unchanged | Obsolete |

|

|

|

|

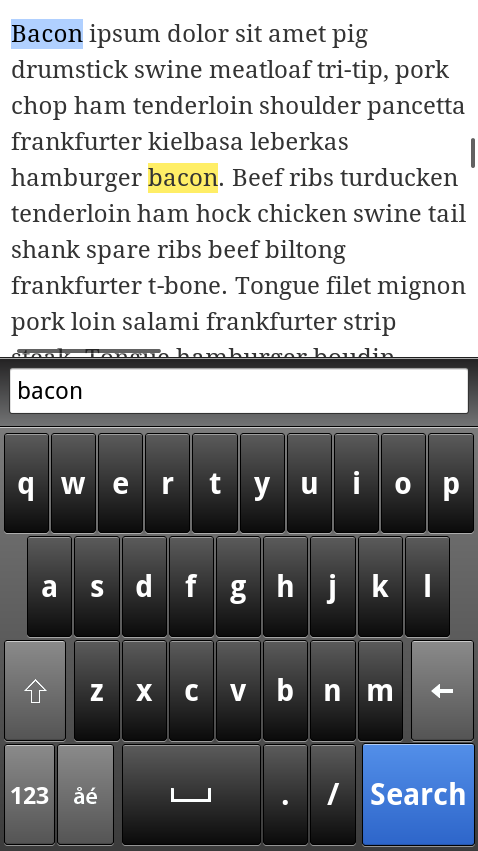

<mark>

The <mark> element is

used to mark text due to its relevance in another context.

“Huh?” you may ask. Think of <mark> as “marking text,” rather than

giving strong or emphasized importance to it. A good use is highlighting

search terms in search results, or text in one block that you reference

in the next.

Have you ever used native search in Safari desktop? You know how it grays out the page, highlighting occurrences of the term you were seeking?

Were you to create that effect, or the effect of viewing a cached

page in Google search, it would be correct to use <mark> for all the results that were

found, with:

mark {background-color: yellow;}

mark:focus {background-color: blue;}in your CSS. This would give you an effect similar to the results shown in Figure 3-2.

While presentational in explanation, it does have semantic meaning. Text that is marked gets semantically (and with CSS, visually) highlighted to bring the attention to a part of the text that might not have been considered important in its original unmarked presentation.

<mark> can be used to

indicate a part of the document highlighted due to its current, though

not necessarily permanent, relevance. For example, when searching for

“HTML5,” to highlight the search term in the resulting page, the most

semantic method would be to code it as follows, styling <mark> with CSS:

<p><mark>HTML5</mark> is currently under development as the next major revision of the HTML standard. Like its immediate predecessors, HTML 4.01, and XHTML 1.1, <mark>HTML5</mark> is a standard for structuring and presenting content on the World Wide Web.</p>

You can add scripts to your search functionality to encapsulate

search term results with the <mark> tags, and then you can style the

marks with CSS to show how many search results were found and where

they are.

<time>

The <time> element

is used to define a specific time or date, providing a

precise, machine-readable time that may get parsed by user agents to be

reused for other purposes, such as entry into a calendar. In your

average game, appropriate uses of the <time> element would be the date and

time that high scores were achieved, and even the duration of the game

or time left.

The datetime attribute enumerates the date. If

the datetime attribute is present, then its value must be a valid date

string.[23] If the datetime attribute is not

present, then the element’s text content must be a valid,

machine-readable date.

“I play CubeeDoo on Saturday mornings” would not be a good

candidate for inclusion of the <time> element. “Let’s play next

Saturday at 11:00 a.m. (I like to sleep in)” would be a better place to

include the element, since it is an exact date and time that can be

specified:

<time datetime="2013-11-30T11:00-8:00">next Saturday at 11:00 a.m.</time>

In CubeeDoo, we could use the <time> element to encapsulate the times

that the highest scores were achieved if you list the dates: while the

user sees a human-readable time, the datetime attribute provides a machine-readable

time.

<rp>, <rt>, and <ruby>

The <ruby>, or ruby

annotation, element allows spans of phrasing content to be

marked with ruby annotations. This has nothing to do with the Ruby

programming language. Rather, ruby annotations are notes or characters

used to show the pronunciation of East Asian characters (Figure 3-3).

The <rp>, or ruby

parenthesis, element can be used to provide parentheses around a ruby

text component of a ruby annotation, to be shown by browsers that don’t

support ruby annotations, hidden when the browser does support it. The

<rt>, or ruby text, element

marks the ruby text component of a ruby annotation.

Use together with the <rt> and/or the <rp> tags: the <rp> element provides information, an

explanation, and/or pronunciation of the <ruby> contents. The optional <rp> element defines what to show

browsers that do not support <ruby>. We don’t use this in CubeeDoo

and ruby is only partially supported on mobile devices. If you are

interested in more information, there is a link to a good explanation of

these three elements and their implementations in the online

chapter resources.

<bdi>

The <bdi> element

(in contrast to the existing <bdo> element, which overrides the direction of text) isolates a

particular piece of bidirectional content. It is needed because of the

way the Unicode bidirectional algorithm deals with “weak” characters.

<bdo dir="rtl"> will invert a

whole line even if only a span is encompassed. <bdi> ensures that only the contents

between the opening and required closing </bdi> tag are reversed. The CSS3

Writing Modes specification has added some properties, like text-combine-horizontal, to help move

presentational aspects of content out of the HTML content layer and into

CSS, where it belongs.

<wbr>

The <wbr> element

represents a line break opportunity within content that

otherwise has no spaces. For example, sometimes URLs can be very, very,

very long. Too long to fit in the width of your column:

<p> <a href="http://isCubeeDoo.partofhtml5.com/">Is<wbr/>CubeeDoo.<wbr/> Part<wbr/>Of<wbr/>HTML5.com</a>? </p>

To ensure that the text can be wrapped in a readable fashion, the

individual words in the URL are separated using a <wbr> element. Add the <wbr> element to indicate where the

browser can break to a new line. The <wbr> is an empty element with no

element-specific attributes.

Changed Text-Level Semantic Elements

A few elements from HTML have been modified in HTML5, including a, small,

s, cite, i,

b, and u.

<a>

As you well know, the <a>

element represents a hyperlink. While not new, we include a

description here since there are changes to the element in HTML5, and

there are special mobile actions depending on the value of the

now-optional href attribute.[25]

First, note that some attributes of the <a> element are now obsolete, such as

the name attribute. To create an

in-page anchor, put the id attribute

on the closest element to your target in the document and

create a hyperlink to that element using the id. For example, <a href="#anchorid"> is an anchor link

that targets the element with an id

of anchorid. Also obsolete are the

shape, coords, charset, methods, and rev attributes.

The target attribute of

<a>, which was deprecated in XHTML Strict, is back. There are a few new

attributes, including download,

media, and ping.[26] The download attribute

indicates the hyperlink is intended for downloading. The

value, if included, is the name the filesystem should use in saving the

file. The media attribute takes as its value a media query list for which the

destination of the hyperlink was designed. The ping attribute accepts a space-separated list of URLs to be pinged when a

hyperlink is followed, informing the third site that an action was

taken, without redirecting through that site.

Also different in HTML5 is that the <a> element can encompass both inline

and block-level content, or in HTML5 parlance, sectioning and phrase

elements. For example, this is now a valid HTML5 hyperlink:

<a href="index.html" rel="next" target="_blank">

<header>

<h1>This is my title</h1>

<p>This is my tagline</p>

</header>

</a>Mobile-specific link handling

Mobile devices have a few link types that receive special treatment when displayed in a browser or in the mobile device’s email client.[27]

You’re likely familiar with mailto: links.

When clicked, it opens your computer’s or mobile device’s email

application, creates a new message, and addresses it to the target of

the link. You can also include the subject and

content for the email.

The tel: link will open the mobile device’s calling application and calls

the number used as the link’s target. In iOS, a confirmation dialog pops up before redirecting to

the phone application and dialing the number for you. When a tel: link is clicked in Android, users are brought directly to the phone

application with the telephone number from the link pre-entered, but

doesn’t dial for you. Similarly, the sms: link will open up messaging.

If you are unfamiliar with SMS links, the syntax is:

sms:<phone_number>[,<phone-number>]*[?body=<message_body>]

Clicking on the following hyperlink will open an alert that asks if you want to call the number in the link or cancel in iOS, and brings up the key pad with the number pre-populated on Android. The SMS link opens up the messaging application. Remember that not all devices have SMS capabilities:

<a href="tel:16505551212">1 (650) 555-1212</a> <a href="sms:16505551212">Text me</a>

Telephone number detection is on by default on most devices. For example, Safari on iPhone automatically converts any number that takes the form of a phone number of some countries to a phone link even if it isn’t a link, unless you explicitly tell the device not to (see format-detection in Chapter 2).

Other links handled differently are Google Maps, YouTube links, iTunes links, and Google Play. When a regular link to a Google Maps page is included in a web page or an email, some mobile devices will open the device’s map application, rather than opening the map in the current or new browser window. Recognizing the link, the phone will launch the Maps application instead:

<a href="http://maps.google.com/maps?q=san+francisco,+ca"> Map of SF</a>

Links to YouTube and to the iTunes store (in iOS) will launch the YouTube widget and iTunes respectively. Links on Android for Android applications will open a pop-up that asks if you want to follow the link or open the link in Google Play.

There are examples of these link types in the online chapter resources.

Text-Level Element Changes from HTML 4

We all thought the presentational elements of <i>, <b>, <s>, <u>, and <small> were destined to become

deprecated, or made obsolete. Instead, they have newfound glory with

semantic meaning.

The <i> element

should be used instead of a <span> to offset text from its

surrounding content without conveying any extra emphasis or importance,

such as when including a technical term, an idiomatic phrase from

another language, a thought, or a ship name.

The <b> element

represents a span of text to be stylistically offset

without conveying any extra importance, such as keywords in a document

abstract, product names in a review, or other spans of text whose

typical typographic presentation is bold.

The <s> element

encompasses content that is no longer accurate or relevant

and is therefore “struck” from the document. The <s> element has been around for a long

time, but before HTML5 only had a presentational definition. HTML5

provides <s> with semantic

value.

Similarly, the <u>

element has been given semantic value. The <u> element represents text offset from

its surrounding content without receiving any extra emphasis or

importance, and for which the typographic convention dictates

underlining, such as misspelled words or Chinese proper names.

The <small> element

should be used to represent the “fine print” part of a

document. While <small> text

doesn’t need to be displayed in tiny print, it should be reserved for

the fine print, such as legalese in a sweepstakes or side effects in a

pharmaceutical ad (which, if you think about it, should really be in a

huge font).

While I didn’t think <cite> was heading for the realm of distant memories, it too has

acquired new meaning. The <cite> element now solely represents the

cited title of a work; for example, the title of a book, song, film, TV

show, play, legal case report, or other such work. In previous versions

of HTML, <cite> could be used

to mark up the name of a person: that usage is no longer considered

conforming.

Unchanged Elements

While you likely know the usage of all the text elements that preceded HTML5 and haven’t had any semantic updates, some may be used less often. Table 3-3 shows a quick summary.

There are also the <ins>

and <del> elements, which are considered editing elements, representing

insertion and deletion, respectively.

Embedded Elements

The 12 embedded elements include six new elements and six old elements. The new elements include the following:[28]

embedvideoaudiosourcetrackcanvas

And these are the existing elements:

imgiframeobjectparammaparea

The embedded elements include the media elements, <video>, <audio>, <source>, <track>, and <canvas>, which we will discuss in Chapter 5. The other “new”

element is <embed>, which has been implemented for years but was never part of

the HTML 4 or XHTML specifications. We’ll discuss this new element and

visit the previously existent elements, as some attributes have been made

obsolete.

Changes to Embedded Elements

<iframe>

The <iframe> element is

not new to HTML5, but it does have different attributes than

before. <iframe> lost

longdesc, frameborder, marginwidth, marginheight, scrolling, and align attributes, and gained srcdoc, sandbox, and seamless.

The srcdoc attribute

value is HTML that is used to create a document that

will display inside the <iframe>. In theory, any element that

can be used inside the <body>

can be used inside the srcdoc. You

should escape all quotes within the srcdoc value with " or your value will end

prematurely. If a browser supports the srcdoc attribute, the srcdoc content will be used. Browsers that

do not support the srcdoc attribute

will display the file specified in the src attribute instead:

<iframe srcdoc="<p>Learn more about the <a href="http://developers.whatwg.org/the-iframe-element.html #attr-iframe-srcdoc">srcdoc</a> attribute." src="http://developers.whatwg.org/the-iframe-element.html #attr-iframe-srcdoc"></iframe>

The sandbox attribute

enables a set of extra overrideable restrictions on any

content hosted by the <iframe>. The effect of adding the

attribute is to embed the externally sourced content as if it were

served from the same domain, but with severe restrictions. Plug-ins,

forms, scripts, and links to other browsing contexts within the

<iframe><iframe>sandbox attribute that conforms to a

specific syntax.

The allow-same-origin keyterm

allows the content to be treated as being from the same origin instead

of forcing it into a unique origin. The allow-top-navigation keyword allows the

content to navigate its top-level browsing context; and the allow-forms, allow-pointer-lock, allow-popups, and allow-scripts keywords re-enable forms, the

pointer-lock API, pop-ups, and scripts, respectively. Include zero or

more space-separated values depending on your needs, but realize that

each value can create a security risk:

<iframe sandbox="allow-same-origin allow-forms allow-scripts"

src="http://maps.google.com" seamless></iframe>The seamless attribute

makes the <iframe><iframe>

<img>

The empty <img> element

lost the border,

vspace, hspace, align, longdesc and name attributes. There is discussion around

adding a srcset attribute to

provide for alternative images based on width, height, or pixel

density.

Unless an image is part of the content of your page, and necessary for context, you will want to use background images instead. We cover background images, and how to serve different background images for different screen sizes and devices of differing DPIs in Chapter 9.

If you do want to support responsive foreground images, until

browsers natively support the srcset attribute, the

<picture> element, or client hints, the

Clown Car Technique[29] <object> tag

can be employed to serve SVG files (discussed in Chapter 5) that provide a

single raster image based on media queries.

<object>

The <object> element

requires the data and type attributes. Several attributes,

including align, hspace, vspace, and border were made obsolete in favor of CSS.

Also obsolete are the archive,

classid, code, codebase, and codetype, which should be set in the

<param> instead. Instead of

using the old declare attribute,

repeat the <object> at each

occurrence. Instead of using the now-obsolete standby attribute, optimize the resource so

it loads quickly, and incrementally if applicable. While not often

used, <object> is well

supported.

<param>

The empty <param>

element lost the type and

valuetype attributes in favor of

the name and value attributes.

<area>

The empty <area>

element lost the nohref

attribute, and gained the rel, ping (see the section <a>

for a description), media, and hreflang attributes.

<embed>

The <embed/> element is

likely not new to you. It’s just new to the

specifications. The <embed>

element is an integration point for content that will be displayed

with a third-party plug-in (e.g., Adobe Flash Player) rather than a

native browser control like <video> and <audio>. Like the <img> element, it is an empty element

and should be self closing. Include the URL of the embedded source

with the src

attribute and MIME-Type of your source with the type

attribute.

Interactive Elements

The interactive elements currently include form elements, the changed

<menu> element, the new <detail>, <summary>, and <command> elements.

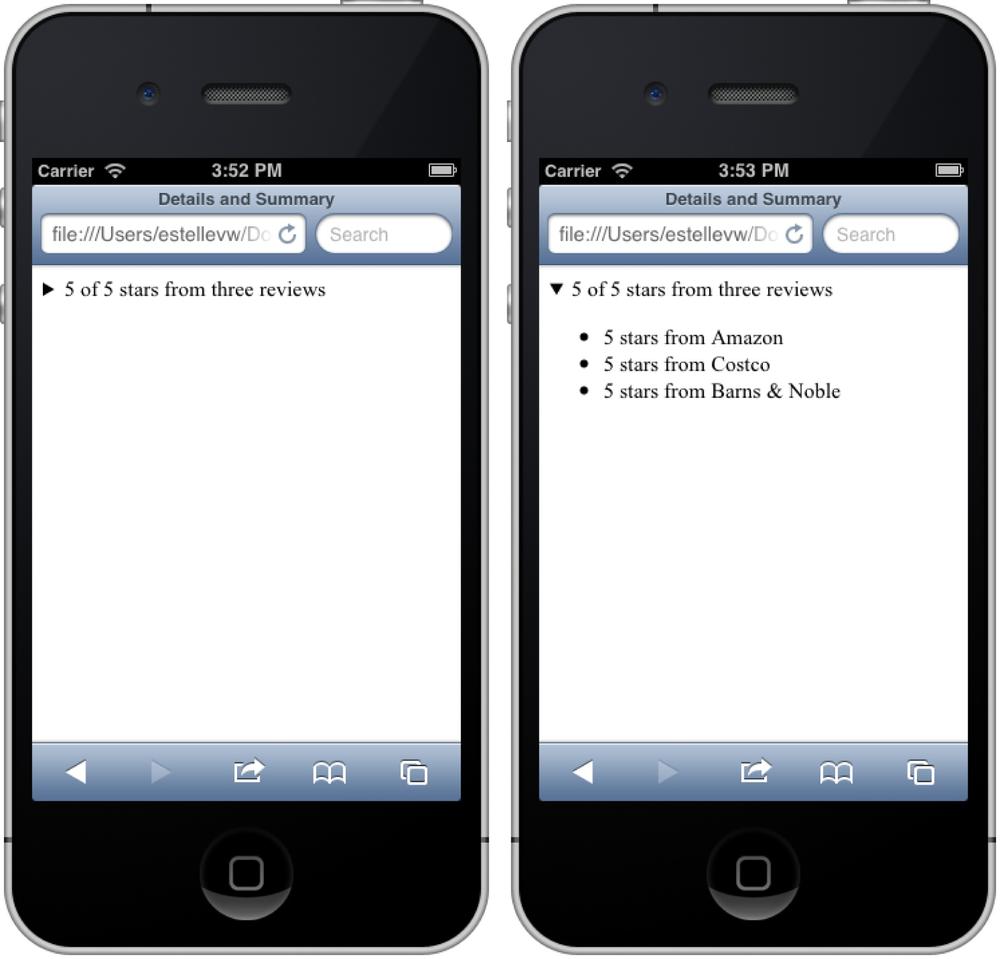

<details> and <summary>

Have you ever created a node that, when clicked on, opens up more details about

the content of the node? And, when clicked on again, the details

disappear? When supported, the <details> and child <summary> enable doing this natively in

HTML5 without any JavaScript (Figure 3-4).

The <details> element can

be used to encompass a disclosure widget from which the user can obtain

additional information or controls, such as content that may best fit

into footnotes, endnotes, and tooltips. The <details> element has an open attribute that is also new in HTML5. With

the open attribute, the content of

the <details> will initially be

visible. Without the open attribute,

the details will be hidden until the user requests to see them.

The <summary> element

should be included as a child element of the <details> element, with its text node

providing a summary, caption, or legend for the rest of the contents of

the <summary> element’s parent details element.

The contents of the <summary>

show by default whether the open attribute is set or

not. By clicking on the <summary>, the user can show and hide

the rest of the content of the <detail> element. This interactivity is

a default behavior of the <details>/<summary> element combo and, when

supported, requires no JavaScript:

<details>

<summary>5 of 5 stars from three reviews</summary>

<ul>

<li>5 stars from Amazon</li>

<li>5 stars from Costco</li>

<li>5 stars from Barns & Noble</li>

</ul>

</details>When supported, the contents of <details> (except for the <summary>) are hidden, as the optional

open attribute is not included (the

default is to hide everything other than the summary). The rest of the

contents should display when the <summary> is clicked. The <summary>, not to be confused

with the summary attribute

of the <table> element, a child

of the <details> element, is

the control that toggles the rest of the <details> content between visible and

hidden (as if display: none; was

set). The <summary> element

represents a summary, caption, or legend for the rest of the contents of

the parent <details>

element.

Because the <summary> is

the control to open and close the <details> element, it is always visible

(in both the details open and not open states). Until all browsers

support this functionality, it’s easy to replicate with JavaScript.

Simply add an event listener to the summary element that adds and

removes the open attribute on the parent <details> element, and add the

following styles to your CSS:

details * {display: none;}

details summary {display: auto;}

details[open] * {display: auto;}If that last line doesn’t make sense to you yet, don’t worry! We cover attribute selectors in Chapter 8.

<menu> and <menuitem>

The <menu> element,

deprecated in HTML 4.01 and XHTML, has resurfaced.

Originally, it was defined as a “single column menu list.” In HTML5, the

<menu> element has been

redefined to represent a list of commands or controls.

The <menu> element has

been redefined in HTML5 to list form controls. The value of the <menu>’s id attribute can be included as the value of a <button>’s

menu or <input>’s menuitem attribute to provide a menu or context menu for a form control. A

menu can contain <menuitem>

elements that cause a particular action to happen. The type attribute set to toolbar should be

used when using <menu> to mimic

a toolbar or when using context to

create a content menu. The value of the label attribute determines the menu’s label. They can be nested to provide

multiple levels of menus.

<menuitem>

The <menuitem> element,

found only inside the <menu>, defines a command button or

context menu item. The type of command is defined by the type attribute, which can have as its value radiobutton for selecting one from a list of

items, checkbox for options that

can be toggled, or command to

create a button upon which you can add an action. Though it sounds

like a typical form control, it is not intended for the submission of

information to a server. <menuitem> is an interactive element

included to enable interactivity with the current contents of a web

page.

The <menuitem> is an

empty element with no closing tag. You should make sure to include a

label attribute whose

value is what will be displayed to the user. Other attributes include

icon, disabled,

checked,

radiogroup,

default, and

command. The

command attribute’s value is the command definition. The title

attribute, if included, should describe the command.

When implemented, you can create menu controls similar to the right-click menu controls that display in the Windows environment. So far, there is only experimental support for this on desktop, and no support on mobile.

All of XHTML Is in HTML5, Except...

Almost all of the elements from XHTML are still available and valid in HTML5. The elements that are obsolete include the following:

basefontbigcenterfontstrike(use<del>)ttframe(<iframe>is still valid)framesetnoframesacronym(use<abbr>)applet(use<object>).isindexdir

As mentioned earlier, a few elements, instead of being made

obsolete, have gained more semantic meaning. <b>, <hr>, <i>, <u> and <small>, while completely presentational

in prior specs, now have semantic meaning and are defined beyond their

appearance. <menu> has gained a

purpose to be useful for toolbars and context menus.

<strong> now means “important” rather than “strongly emphasized.”

<a> can now encompass blocks

instead of just inline content, and doesn’t need to have the href attribute present.

Some attributes are now obsolete. Some attributes have been added. Most of the changes are in web form elements, which we’ll cover in great detail in Chapter 4. Otherwise, a few things to note that have not been previously detailed include:

<table>no longer has thewidth,border,frame,rules,cellspacing, andcellpaddingattributes.<col>and<colspan>lost all their element-specific attributes except forspan.<td>and<th>had their attributes narrowed down toheaders,rowspan, andcolspan, obliteratingabbr,axis,width,align, andvalign. Scope was removed for<td>but remains for<th>.<tr>and<thead>are attribute-less other than the global attributes.

In Conclusion

The HTML5 spec is huge. This section has introduced you to the syntax and semantics of HTML5, and to some of the new elements. This chapter was intended as a quick (or not so quick) explanation of the new elements in HTML5.

We’re not done with HTML5. We are going to cover some wonderful features of web forms in Chapter 4, and show you how the Web Form features of HTML5 can help you quickly develop fantastic user interfaces with minimal JavaScript.

[21] The hgroup element that was

originally added to HTML5 was made obsolete. It has not yet been

removed from the WHATWG spec, but has been removed from the W3C HTML5

and W3C HTML5.1 specifications.

[22] Because of its semantic value, screen readers announce the

beginning and end of each <section>. Unless

your page is comprised of semantic sections of content, use the

nonsemantic <div>, which is not called out

by the screen reader.

[23] Date values must be machine-readable dates. Date strings are defined at http://www.w3.org/TR/NOTE-datetime.

[25] If the href attribute is

not specified, the <a>

represents a placeholder hyperlink.

[26] The media, ping, and download attributes are under discussion,

but are expected to be included in the specifications.

[27] Skype can also be launched from the browser. Check out http://dev.skype.com/skype-uri for more details.

[28] The <picture> element

for responsive images is currently under consideration. The draft

specification is at http://www.w3.org/TR/html-picture-element/.

[29] The Clown Car Technique is described in full detail at http://github.com/estelle/clowncar/.

![<ruby> and <rt> used to write Japanese (Translation: [Confucius says] One must draw the line somewhereFrom ULINK WITHOUT TEXT NODE..)](httpatomoreillycomsourceoreillyimages1862107.png)