See Juglans

At one time or another, most of us have experienced a water shortage. We couldn’t wash our cars, water our lawns and gardens, or let the children play in the sprinkler. The restrictions lasted maybe a few weeks; then it rained and life returned to normal. But demand for water continues to out-pace supply, and running on empty is becoming a way of life in regions across the United States and in countries around the world.

The world has lots of water, but only 3 percent of it is fresh; the rest is salt water. Although fresh water is a renewable resource, human demand is exceeding the capacity of both natural systems and water-treatment systems to supply it.

In the 1980s, many cities adopted water conservation standards for the first time in response to prolonged droughts. By the 1990s, some regions reported that their water table was dropping significantly—as much as 4 feet a year.

This problem isn’t limited to the United States. Population growth has led to increased water consumption worldwide as well. Between 1900 and 1995, global water consumption increased at more than double the rate of the world population and it continues to rise, creating water demands that cannot be met with existing supplies and delivery systems. Even if new reservoirs and pipelines are built, there is no guarantee of enough water to fill them, especially if climate change leads to significant disruptions of rainfall. According to a United Nations study of the world’s supply of fresh water, as many as seven billion people in 60 countries could be out of water by 2050.

Water quality is also an increasing concern. In the past decade, stormwater runoff has emerged as the number one water quality problem in the United States. Water that runs off roofs, parking lots, roads, driveways, and landscapes into storm-water collection systems often ends up contaminated with sediment, pesticides and other toxic substances, invasive organisms (such as seeds and aquatic creatures), excess nutrients (from lawn fertilizers), road deicing salts, and even pathogens when municipal sewage facilities overflow during heavy rains.

The good news is that stormwater runoff is a problem that nearly every home gardener can help to solve in some small way. That’s because soil and plants are great filters; they absorb lots of water and capture pollutants. When rain falls on (or is channeled into) planted surfaces, less of the bad stuff goes down the storm drains and into lakes or groundwater.

To learn more about water-conservation techniques and wise water use for home gardens, see the entries for Graywater, Rain Gardens, Rain Barrels, Watering, Water-Wise Landscaping, and Xeriscaping.

There are lots of small things you can do to protect water quality.

Read labels. This includes labels on organic fertilizers and pest-control products, paint, and cleaning products. Choose least-toxic options and apply according to label directions. Follow the guidelines for use and disposal. Never pour these products down the sink or toilet or into storm drains or sewers.

Separate hazardous waste from your trash. Find out where and when there are hazardous waste collections, and spread the word in your community to dispose of hazardous products properly.

Prevent runoff and soil erosion. Keep your yard planted and bare areas mulched. Use lots of organic matter (typically in the form of compost) in your soil. Organic matter increases the soil’s capacity to hold water and keep it where the plants can use it. (See the Soil entry for more on this.)

Try mulch or gravel. Instead of concrete or blacktop, consider a mulch, brick, flagstone, or gravel surface that lets water percolate through. For a casual outdoor living area, pavers and gravel can get very hot, so consider shredded bark mulch, which is much cooler underfoot.

Use permeable paving. Ask your contractor or look in hardware stores for permeable paver systems that have a honeycomb-type structure that gives you space to grow plants, allows water to flow through, and also provides a framework that lets you drive or walk on pavers without damaging plants.

Stockpile manure carefully. Gardens love compost made with manure, but rainwater that runs through a pile of fresh manure and then into drainage systems can carry pathogens and excess nitrogen. Keep manure covered, on a level site, and out of the path of surface runoff. Ideally, don’t stockpile manure at all—mix it into compost as soon as you procure it.

Plant the banks of your pond or stream. Ask the staff at your local soil and water conservation organization for recommendations for waterside planting in your region. A lawn is the worst thing to plant near water; willows (Salix spp.), dogwoods (Cornus spp.), or buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) might be the best. (Even if your lawn is organic, grass clippings add undesirable nutrients to the water.)

Water is calming and refreshing—the most magical garden feature. It’s possible to have a water garden in even the smallest yard, especially now that almost all garden and home centers sell water garden and pond supplies. You can choose a wall fountain, barrel or other container, pool, or pond. Water gardens can be formal or informal. Formal pools have geometric shapes like squares, rectangles, or circles, and can be made of precast fiberglass liners or concrete. Concrete pools require a professional for proper construction, so most gardeners use fiberglass for formal pools.

But for most backyard gardeners, an informal, do-it-yourself water garden is more practical and better suited to today’s yards and lifestyles. Informal water gardens can be kidney-shaped or really any shape that pleases you. You can even shape the water garden to suit your site. Most container gardens are considered informal as well, even if they’re round like a half barrel.

If you are starting a water garden from scratch, your first task is to choose a site. Select a level spot that receives at least 6 hours of sun daily. (You can create a water garden in a shaded spot, but you won’t be able to grow water lilies.) Water gardens under trees are beautiful, but clearing out dropped leaves can be a maintenance nightmare.

An informal pool looks best set against a background. Site a large pool where plantings of shrubs and flowers will serve as a backdrop. You can site smaller pools against a wall or fence. If you want a waterfall, blend it into the landscape with background plantings. Avoid vigorous fountains; most water plants prefer still water.

When planning your water garden, you can choose a flexible liner made of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) plastic or butyl rubber, or a rigid fiberglass liner for the pool. All three types are available from water-garden supply companies. A PVC or butyl rubber liner will adapt to any shape pool you want to dig; fiberglass pools are preshaped, so you have to dig a hole that’s the same shape as your liner. Both flexible liners and rigid liners are easy to install.

If you opt for a flexible liner, consider its lifespan when ordering, and choose the best liner you can afford. Butyl rubber liners are stretchy and last longest—up to 30 years—but are also the most expensive. The thicker a PVC liner, the better it is. PVC liner thickness is measured in mils. A 32-mil PVC liner will last 15 to 20 years and is the next best choice, followed by 20-mil PVC, which must be replaced every 7 to 10 years. Imagine emptying your whole pond to replace the liner, and choose accordingly!

Plastic and rubber liners: First, draw the shape and dimensions of your garden pool on graph paper. Make the pool as large as you can to set off the water plants—3 by 5 feet is a nice minimum size. Give the pool a natural shape, with smooth, flowing curves; avoid tight angles. Keep it simple, like a kidney or amoeba shape. Make your pool 1½ to 2 feet deep if you want to grow water lilies and lotuses.

To determine the size liner to buy, add the width of the pool to two times the depth, and then add 2 more feet for the edges. (So, if your pool is 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep, multiply 2 by 2 feet = 4 feet, add 3 feet = 7 feet, plus 2 feet = 9 feet for the liner width.) Do the same, substituting length for width, to get the overall dimensions.

Use a tape measure and a garden hose to re-create your chosen shape on the garden site. Strip the sod inside the marked area with a flat-bottomed shovel. Excavate the hole 20 to 24 inches deep, sloping the side gradually and keeping the bottom as flat as possible. Pile the excavated soil on a tarp. Make shelves about 9 inches wide along the pool sides to accommodate shallow-water plants. A good shelf depth is 9 to 12 inches, depending on the plant and pot size. Check to make sure the pool sides are level by placing a two-by-four over the opening. Use a builder’s level on the board to check for high spots. Remove or add soil as necessary to make the rim even.

Remove rocks, sticks, and other sharp objects, then line the entire hole with 1 to 2 inches of builder’s sand, packed down firmly. Cover the sand layer with a piece of old carpet pad or, better yet, purchase underlayment from a water garden supplier. (Underlayment prevents sharp objects from piercing the liner.) Then gently place the pool liner over the hole, with the center at the deepest point. Let the liner sink into the hole and check to make sure it will reach the edges on all sides, then slowly add water to the new pool. The liner will be pushed snug against the sand or carpet-pad lining as the pool fills. The liner is very difficult to move and readjust once you’ve started to add water, but watch as the pool fills and adjust the liner to remove wrinkles and reshape the sides.

Give the filled pool a day to settle, then cut off the excess liner, leaving at least a 6-inch lip along the level edge. Disguise the rim with flagstones, bricks, rocks, or plants. Bury any edges that aren’t covered by the border stones.

Fiberglass liners: Follow a similar procedure for a rigid fiberglass pool. Many shapes and sizes of these comparatively inexpensive, preshaped, portable pools are available. The best have two or three levels—a deep center and at least one or possibly two shallower ledges for marginal (shallow-water) plants. Dig a hole larger than the pool, shaping it to fit the pool’s levels, and line it with 1 to 2 inches of sand. Place the liner into the hole, leaving the rim just above ground level. Place a builder’s level across the top and make any necessary adjustments so the pool edge is absolutely level. Fill the pool slowly, backfilling with sand as the liner settles into the hole. Disguise the rim the same way you would for a flexible liner.

In the design shown here, a bog garden forms a natural transition between a lovely water garden and the surrounding landscape. Rocks go beautifully with water, and this rock garden frames the pool and bog garden.

Water Garden

1.Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera or N. lutea)

2.Water lily (Nymphaea hybrid)

3.Yellow flag (Iris pseudacorus)

Bog Garden

4.Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata)

5.Pink turtlehead (Chelone lyonii)

6.Japanese primrose (Primula japonica)

7.Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris)

8.Marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris)

Rock Garden

9.Harry Lauder’s walking stick (Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’)

10.Creeping juniper (Juniperus horizontalis)

11.Common beardtongue (Penstemon barbatus)

12.‘Vera Jameson’ stonecrop (Hylotelephium ‘Vera Jameson’)

13.Heartleaf bergenia (Bergenia crassifolia)

14.Yellow-flowered dwarf daylily (Hemerocallis ‘Happy Returns’ or ‘Bitsy’)

15.Golden hakone grass (Hakonechloa macra ‘Aureola’)

16.Lady’s mantle (Alchemilla mollis)

17.Candytuft (Iberis sempervirens)

18.Cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea)

19.Lavender (Lavandula spp.)

20.Thyme (Thymus spp.)

21.Carpathian harebell (Campanula carpatica)

22.Maiden pinks (Dianthus deltoides)

23.Hens and chickens (Sempervivum spp.)

24.‘Autumn Joy’ sedum (Hylotelephium ‘Herbstfreude’)

25.Purple moor grass (Molinia caerulea)

26.Dwarf goldenrod (Solidago ‘Peter Pan’ or ‘Goldenmosa’)

The amount of water a plant requires or tolerates determines where you can grow it. Moisture-loving plants such as cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) and Siberian iris (Iris sibirica) prefer to grow on the land around a pond, with their roots penetrating into the wet soil. See the information in the sidebar Plants for Water Gardens for more plants to grow in or around your water garden.

You can create an exciting landscape around your water garden, but use restraint when choosing plants for the pool itself. One of the chief pleasures of water gardening is enjoying reflections in the water, so you don’t want to completely cover the surface with water plants. Strive for a balance of one-third open water to two-thirds plant cover. Consider the mature spread of the plants you plan to order. Plant water lilies 3 to 5 feet apart to give them room to spread out in their typical bicycle-spoke pattern, and make sure you position them in full sun (they need at least 6 hours of sunlight daily).

Wait at least a week after filling your pool before adding plants or fish, so the chlorine can evaporate and the water can warm up. If your community uses chloramines (a chlorine-ammonia compound) to treat its water, it won’t evaporate. Use a product such as DeChlor or AquaSafe to neutralize the chloramines before adding plants or fish.

Plant water plants in containers before placing them in the water garden. Use black or brown plastic tubs or pails. You can find special containers designed for water garden plants at water garden and pond specialty stores and Web sites and at many garden centers that carry water garden supplies. Plants like water lilies need sizeable containers; plant them in a 5- to 30-quart (1 to 4 feet wide and about half that deep) bucket, tub, or basket-type container.

The best soil is heavy garden loam, with some clay mixed in for stability, and well-rotted (not dried) cow manure added for fertility. (Mix one part cow manure for five parts soil.) Do not use commercial potting mixes with lightweight peat and perlite that will float to the water’s surface. There are many types of fertilizer pellets for water garden plants as well, but most of these contain synthetic chemical fertilizers. Ask specifically for pellets that contain only organic ingredients if you want to try this approach instead of using manure.

Fill containers one-half to two-thirds of the way with soil, depending on the size of the rootstock. Position the roots around a cone of soil with the crown 2 inches below the rim of the pot. Fill the remainder of the container with soil up to the crown of the plant. Cover the top of the soil with 1 inch of pea gravel. Do not bury the growing points. Fill the container with water and allow it to settle. Refill and allow a gentle stream of water to run over the rim of the container until it runs clear. Sink the pots to the proper depth in the pool. (For water lilies, depending on the cultivar, the pots should be sunk so there are 6 to 18 inches of water above the crown.) In 2 to 4 weeks, your plants will have adjusted and be growing vigorously.

Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) is a lovely water garden plant that floats serenely on the surface of the water, forming large clumps and sending up beautiful lavender flowers. But unfortunately, it has escaped in Florida and other mild-winter areas and become a major invasive in canals, lagoons, and other bodies of fresh water, covering the surface of the water and choking out native plants. Unless you live in the North and your water garden is isolated from natural bodies of water, including streams and ponds, choose from the many other attractive water garden plants instead.

Water gardens need routine maintenance. To avoid the buildup of decaying plant material, remove yellowing leaves and spent flowers of water garden plants. Weed the banks and edges regularly, too. Divide plants every 2 to 3 years; pot-bound plants will quickly lose vigor.

Winter protection is important. If you live in a moderate climate, you can leave hardy plants in the pool over winter. (In severe climates, where the water may freeze to the bottom of the pool, store hardy plants indoors as you would tropical ones.) Make sure the pots are below the ice at all times. You can use a stock tank deicer (available from water garden specialists or farm stores), which floats directly in the pool, to keep the water from freezing if you like. Lift tropical water lilies each fall and store them in a frost-free place. Place the containers in a cool spot and keep the soil evenly moist throughout the storage period. A cellar or cool greenhouse is ideal.

Maintaining a balanced environment is essential to prevent algae from covering the pond with green scum. Algae need nitrogen and sunlight to grow. Grooming water plants will reduce the buildup of excess nitrogen in winter, while shade from their foliage will reduce sunlight.

You should treat water plants like any garden plant during the season as well, removing yellow and damaged leaves and dead flowers. If aphids infest the leaves, submerge the plants, leaves and all, to dislodge the pests, or hose them off with a jet of water. Keep an eye on the plants; you may need to repeat this procedure several times before the plants are aphid-free.

Plants that grow entirely underwater are good natural filters. They absorb excess nitrogen and are important for maintaining a balanced pool. Freshwater clams, which are filter feeders, and black Japanese or trapdoor snails, which are scavengers, are available from water garden suppliers and will also help keep your water clear. So will the tadpoles that may appear in spring.

Goldfish and koi add color and movement to the water garden. Though they may stir up the pond bottom in search of food, they’ll keep the water free of mosquito larvae. Fish are also great biological controls for plant pests—if your water plants are bothered by aphids or caterpillars, hose the pests into the water and the fish or frogs will finish them off.

If the water becomes cloudy despite your best efforts, or if you have fish in your pool, you may need to install a recirculating pump and filtering system to aerate the water. A recirculating pump will enable you to lift water to a height from which it can fall, adding oxygen (which the fish need) to the water while also adding the lovely sound of moving water. Pumps and filters are available from garden centers, home stores, and Web sites, catalogs, and companies specializing in water gardening. You can find many models of pumps and waterfalls that are solar powered, a great convenience if your water garden is located far from power sources or if you’re trying to reduce dependence on nonrenewable energy sources.

There are plants for the shallow edges of a water garden as well as the deeper water in the center. Here are some of the best hardy plants for your water garden along with information on water depth preferences.

You can choose from many plants for growing along the water’s edge or in up to 6 inches of water. Blue flag (Iris versicolor) and copper iris (I. fulva) have clumps of sword-shaped leaves and showy flowers. Sweet flag (Acorus calamus), arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), golden club (Orontium aquaticum), and pickerel weed (Pontederia cordata) are other fine plants for the pool’s edge.

Other aquatics need deeper water—3 to 12 inches—and will float their foliage on the water surface. These include plants such as water clover (Marsilea spp.), parrot’s-feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum), and water snowflake (Nymphoides indica). Grow them along the pond edges or with pots set on bricks in the center of the pool.

Lotuses (Nelumbo spp.) are hardy perennials that grow in about 4 inches of water. They bloom in summer and hold their leaves above the water’s surface. Prop the tubs in which they are growing on bricks to provide them with the proper depth.

Water lilies (Nymphaea spp.) grow in up to 2 feet of water and float their rounded or heart-shaped leaves on the water’s surface. Flowers rest on or above the water and come in a wide variety of colors, including white, pink, yellow, and purple. They may be hardy or tropical. Hardy water lilies can overwinter in your water garden, but tropicals must be overwintered indoors or replaced annually. Give water lilies plenty of room; their floating, rounded leaves (lily pads), often beautifully splashed with red or purple, can spread out in a 6-foot circle, covering the water surface. Divide plants every 2 to 3 years for renewed vigor and abundant bloom.

Specialty water garden catalogs, Web sites, and nurseries carry many lovely water lily cultivars. Usually the less expensive cultivars and those with Latin-sounding names are older tried-and-true plants, such as yellow ‘Chromatella’ (a good choice for small pools and barrels), pink ‘Fabiola’, and white ‘Virginalis’. Make sure to choose miniature water lily plants for smaller water gardens (remember that 6-foot spread for standard sizes!).

Every pond should also contain submerged plants that help trap debris in the leaves and compete with algae for dissolved nutrients in the water, thus helping to keep the water clear. These include anacharis (Egeria densa), Carolina fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana), elodea (Elodea canadensis), and American eelgrass (Vallisneria americana).

Hardy water garden plants—plus many tropical water plants—are available from companies specializing in water gardening.

Barley straw has been shown in numerous tests to prevent algae growth. For a small or container water garden, you can buy a plastic “barley ball” via garden centers, home stores, or water garden specialty suppliers and catalogs. Float this barley-straw-filled ball in your water garden to keep algae at bay. For a large in-ground water garden or pond, bales of barley straw will keep your water garden sparkling clean and algae-free.

When you bring your new fish home, don’t just dump them into your water garden. Being cold-blooded, they need time to adjust to the difference in water temperature. Float their plastic, water-filled bag on the surface of the water to give their air bladders a chance to adjust, then release them into their new homes. You’ll be glad you took this extra step—your new fish will thrive.

Another enjoyable garden project that can turn a low, wet spot into a landscape asset is a bog garden. With a little effort, you can turn an unused area into a garden feature. A bog garden is also a natural companion for a water garden, as shown in the design.

Even if you don’t have a low wet spot, you can still have a bog garden. All you need to do is to excavate a hole and line it with a plastic pool liner. The larger you make your bog garden, the better, since small excavations dry out quickly. Choose a level spot in sun or shade, depending on the plants you wish to grow. Excavate a bowl-shaped hole 1½ to 2 feet deep at the center. Line the hole with a commercial pool liner or a sheet of 6-mil plastic.

Unless you have sandy soil, don’t use the soil you dig out for your future bog garden. The best mix for a bog is 50 percent sand and 50 percent compost or peat. Fill the excavation with soil mix until it mounds in the center, packing it down as you go. Fill your new bog garden with water. Wait at least a month before planting to let the soil settle. Keep the soil wet at all times.

Natural bogs contain plants that are adapted to wet, acid soils. Perennial bog plants you can grow include water arum (Calla palustris), creeping snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula), twinflower (Linnaea borealis), and bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata). Woody plants for backyard bogs include winter-berry (Ilex verticillata), sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), rhodora (Rhododendron canadense), and blueberries and cranberries (Vaccinium spp.). Many bog plants, such as pitcher plants (Sarracenia spp.) and sundews (Drosera spp.), are becoming rare in the wild. If you choose to plant them, buy only from reputable dealers who propagate their plants.

If your soil is neutral rather than acid or if you’d like to grow a more colorful collection of plants, your choices are wider than if you’re duplicating true bog conditions. There are quite a few plants that enjoy wet feet. Perennials that grow well in wet garden soils in full sun include swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), spotted joe-pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum), rose mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos), Siberian iris (Iris sibirica), blue flag (I. versicolor), rodgersias (Rodgersia spp.), and globeflowers (Trollius spp.). Perennials for a partially shaded bog site include jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), turtleheads (Chelone spp.), ligularias (Ligularia spp.), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), water forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpioides), and Japanese primrose (Primula japonica). Woody plants for soggy soils include red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), willows (Salix spp.), swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum), and blueberries.

The most important maintenance job for a bog garden is watering, especially if it is an artificial bog. Never allow the soil to dry out. Dry soil is sure death for water-loving plants. If you’re re-creating an acid-soil bog, grow a living mulch of sphagnum moss (available from biological supply houses). Mulch your bog garden with pine straw or oak leaves in winter to protect delicate plants. Remove the mulch in spring to allow the sphagnum to grow. If you don’t have sphagnum, leave the mulch in place to rot into the soil. Remove weed seedlings before they become a problem. Since bogs are naturally low in nutrients, bog plants don’t need fertilizing.

It sounds strange, but water is the best fertilizer you can give your plants. Adequate water is simply essential for plant growth, because plant cells are made up largely of water. Without sufficient water, plant cells can’t enlarge, and that results in weak, stunted plants. You can have the best soil, seed, and intentions in the world, but without water, nothing will grow.

The need to supply water is an ever-increasing concern for gardeners because the world’s supply of clean water is ever more threatened. Your goal in planning and planting your garden is to minimize the need for supplemental watering. Fortunately, there are many ways to reduce water use in the garden. To learn more about the threats to the world’s water supply and about water-wise landscaping techniques that help conserve water and minimize water use, see the entries on Water Conservation and Water-Wise Landscaping.

Plants use—and lose—water continuously. Roots absorb water, which is drawn upward to the leaves. Leaves have microscopic pores in their surfaces called stomates, which can be open or closed. Much of the time, stomates are open, which allows carbon dioxide to enter the leaves. That’s a good thing, because through the process called photosynthesis, plants use carbon dioxide and energy from the sun to make food (sugars) that fuel their growth. Unfortunately, when stomates are open, water escapes out of the leaves. (This process, called transpiration, has a purpose: It cools the leaves and prevents them from overheating in the sun.)

Since plants are continuously losing moisture, roots need to keep drawing water from the soil. Thus, our goal as gardeners is to make sure the soil can hold plenty of water. How much water the soil can hold depends on its texture and organic matter content. The best way to increase your soil’s water-holding capacity is to add organic matter. You can learn how to do this by consulting the Soil entry.

As you continually build your soil with organic matter, you can use other gardening practices that help protect soil water and encourage plants to make the best use of it. For example, in deep, rich soil protected by mulch, plants find it much easier to develop the strong, deep root systems necessary to find water during dry periods. This won’t “droughtproof” your plants, but research has shown that crops grown in organically managed soils withstand drought much better than those in unimproved soil. Lightly cultivating the soil between row crops also helps water filter into the soil.

One important skill to develop is assessing when it’s necessary to water. If you’re waiting until you see your plants wilt, then you’re waiting too long (although it is natural for many kinds of plants to wilt briefly during the hottest part of a summer day).

Instead of relying on wilting as a cue to water, learn how to check your garden’s soil moisture instead. An easy way to do this is to stick your index finger into the soil of your garden beds. The top 2 to 3 inches of the soil may feel dry, so be sure you push down at least 3 inches. You should be able to feel the difference when you hit moist soil. If the soil is dry at the 3-inch level, it’s time to water, unless rain is in the forecast that day.

An exception to this rule is for seeds and seedlings. Since they are just starting to grow, they need moisture right in the top inch of soil. Keep them constantly moist.

In warm weather, water in the morning to avoid hot sun or strong winds that cause water to evaporate faster. If that’s not feasible, then wait until late afternoon, but not too late, as you want foliage to dry off before nighttime to reduce the chance of diseases developing.

For those situations where you have to water, always strive for the most efficient method. When you water with the hose or an overhead sprinkler, some of the water is immediately lost to evaporation from plant surfaces, through surface runoff, or by falling in areas that don’t need water, such as a street or walkway.

Drip irrigation is the most efficient watering method. You can design a system for nearly any part of your landscape, including trees and shrubs, container gardens, and flower gardens. Also called “trickle” or “weep” irrigation, drip systems are as beneficial for dryland gardeners in the arid Southwest as for those in the northern, eastern, and southern parts of the country. They more than make up for the cost and effort involved in design and installation in water savings and increased plant growth. For details on drip irrigation, see the Drip Irrigation entry.

Sometimes drip irrigation isn’t practical or convenient, such as when you sow a small patch of seeds in your vegetable or flower garden or add a single new perennial or shrub to an island bed. In those cases, old-fashioned hand watering is the way to go. A soaker hose represents a compromise between watering by hand and installing drip irrigation. A soaker hose has pores that let the water seep out of its sides, letting it leak gradually into the soil where the hose lays. Think of a soaker hose as a temporary drip irrigation system that you can place next to newly planted seeds or seedlings and use to water them slowly and gently. You can also position a soaker hose in a perennial border or landscape planting and leave it in place all season. Of course, a soaker hose lacks the precision of drip irrigation, but it is much more efficient in terms of both your time and water use than a sprinkler. You can even put a timer on a soaker hose at the tap to turn it on and off when you’re away.

Be gentle with seeds: For watering newly seeded areas, always use a watering can with a rose-type nozzle, or a hose nozzle that has a mist setting. You want to water the soil surface as gently as possible, with small droplets of water, to avoid washing out the newly planted seeds.

Add a cover-up: Newly sown vegetable and flower seeds will germinate fastest and best if the soil is constantly moist. Some seeds, such as carrots, are very sensitive to moisture, and if the soil dries out at all during the germination process, it will reduce the germination percentage significantly. One way to ensure the soil stays moist is to cover the seeds with compost instead of soil, because compost is better at retaining water. Or you can sprinkle a light layer of grass clippings over the well-watered seedbed, or cover it with a small piece of row cover or burlap. For slow-to-germinate seeds, try an even heavier cover, such as a piece of scrap plywood, suspended just above the soil surface (use stones at the corners to prop up the wood).

Try using a wand: A spray wand is a watering nozzle with a long handle that attaches to a garden hose. With a wand, it’s easy to direct water right to the base of a plant. They’re also handy for watering containers and hanging baskets.

Make a reservoir: Gallon-size plastic juice jugs work well for this purpose. They’re made of tougher plastic than milk or water jugs, so they last longer. Fill the jug with water, screw on the lid, and take it to the newly planted tree or shrub. Use a large safety pin to poke one or two holes in the bottom of the jug and then nestle the jug beside the plant. Then loosen the lid slightly to allow water to drip slowly through the holes and into the soil. Just remember to remove the jug when it’s empty so it doesn’t blow away. You can also “install” watering reservoirs more permanently in the vegetable garden, as shown in the illustration at left.

A reservoir at the ready. An upturned soda bottle buried partway in the soil serves as a handy watering reservoir that wicks water directly to plant roots and encourages plants to develop a deeper root system.

See Melon

With some ingenuity and retooling, nearly every gardener and homeowner can have a beautiful yard and garden while watering less often and more efficiently. This is especially important for gardeners in arid areas, where they may adopt a system of landscaping called xeriscaping. Xeriscaping reduces water use by improving the soil’s water-holding capacity, relying on plants (often native) that thrive in a region’s natural climate conditions, grouping plants together according to their water needs, and using efficient watering systems. You can read more about this approach in the Xeriscaping entry.

Even if you don’t live in a dry climate, it’s important to cut down on water use in the garden. You can start right away with small changes and over time make the bigger landscape conversions that help to save water. Here’s a list of water-wise techniques you can start using today.

Mulch trees, shrubs, and other plants with up to 3 inches of mulch. See the Mulch entry for suggestions of materials to use.

Mulch trees, shrubs, and other plants with up to 3 inches of mulch. See the Mulch entry for suggestions of materials to use.

Water less frequently, but water deeply, until you saturate the soil to the depth of the plant’s roots. In the case of a lawn, that might be 4 inches, but it’s 14 inches for a shrub or a tomato plant. Daily watering encourages lazy, shallow root systems.

Water less frequently, but water deeply, until you saturate the soil to the depth of the plant’s roots. In the case of a lawn, that might be 4 inches, but it’s 14 inches for a shrub or a tomato plant. Daily watering encourages lazy, shallow root systems.

Avoid using a sprinkler as much as possible. Water small plants (vegetables, perennials, annuals, small shrubs) at their base with a watering wand to supply water directly to the root zone. If the root area is small or extremely dry, you may have to go back to the same plant more than once in a watering cycle.

Avoid using a sprinkler as much as possible. Water small plants (vegetables, perennials, annuals, small shrubs) at their base with a watering wand to supply water directly to the root zone. If the root area is small or extremely dry, you may have to go back to the same plant more than once in a watering cycle.

If your time or water supply are limited, and you have to choose what to water, choose whatever you’ve planted most recently. Trees and shrubs that were planted in the last 2 or 3 years are at risk of dying if they do not get adequate water. If you’re choosing among thirsty plants, keep in mind that the trees are a big investment; annuals like petunias last one summer.

If your time or water supply are limited, and you have to choose what to water, choose whatever you’ve planted most recently. Trees and shrubs that were planted in the last 2 or 3 years are at risk of dying if they do not get adequate water. If you’re choosing among thirsty plants, keep in mind that the trees are a big investment; annuals like petunias last one summer.

Recycle household wastewater from the kitchen sink, bath, or dishwasher. See the Graywater entry for more on this.

Recycle household wastewater from the kitchen sink, bath, or dishwasher. See the Graywater entry for more on this.

If you garden in an arid climate, there may be little to no rainwater to catch for weeks at a time. You’ll have to provide supplemental water for food crops and some other plants. To make the most of that water, take extra steps to conserve moisture. For example, you can create recessed beds that are several inches deeper than the surrounding soil by digging down several inches and using the removed soil to create raised sides around the garden bed (as you do this, set aside the first few inches of topsoil to return to the recessed area). This shelters the soil surface from drying winds and slows moisture loss from the soil. If you’ve already planted a garden with level beds, then put up mulch berms made of hay bales or layers of soil and mulch alongside the beds to block the wind.

Once you’ve adopted water-wise maintenance techniques, think about planting projects that can ultimately help you reduce the amount of water you use. The single most important one for most situations is to start converting your lawn to other uses. That doesn’t mean you have to cover your yard with cement, asphalt, or stones. You can add a new measure of beauty and enjoyment to your yard with groundcovers, mulches, and shade trees to help you and your yard keep cool. The Lawns and Groundcovers entries include many suggestions for lawn alternatives.

Here are other water-wise planting practices to keep in mind.

Whenever you plant, add some compost or other organic matter to the soil.

Whenever you plant, add some compost or other organic matter to the soil.

Select native plants that require less water. The Native Plants entry offers many tips on using natives in your yard.

Select native plants that require less water. The Native Plants entry offers many tips on using natives in your yard.

Plant more perennials (especially those labeled drought tolerant) and fewer annuals.

Plant more perennials (especially those labeled drought tolerant) and fewer annuals.

Cut back on container plantings during water shortages. If you love those constantly blooming annuals in hanging baskets, try planting them in the soil instead. Trailing petunias, for example, will drape their flowers lavishly over the soil and need only occasional watering compared to the same plant in a little plastic pot.

Cut back on container plantings during water shortages. If you love those constantly blooming annuals in hanging baskets, try planting them in the soil instead. Trailing petunias, for example, will drape their flowers lavishly over the soil and need only occasional watering compared to the same plant in a little plastic pot.

Garden more in the shade. Create more shade by putting up pergolas, awnings, and trellises. Water evaporates less there, and plants don’t dry out so quickly. Most garden centers now offer a full range of shade-tolerant plants.

Garden more in the shade. Create more shade by putting up pergolas, awnings, and trellises. Water evaporates less there, and plants don’t dry out so quickly. Most garden centers now offer a full range of shade-tolerant plants.

Add a walkway, deck, or patio to help reduce water consumption by expanses of turfgrass while adding more enjoyment to your yard.

Add a walkway, deck, or patio to help reduce water consumption by expanses of turfgrass while adding more enjoyment to your yard.

Gardeners have always been interested in the weather, and with the advent of major media coverage of climate change, weather is an almost daily concern for people everywhere. Weather is especially critical to those of us who grow plants because the weather affects not only the health and growth rates of our crops but also determines to a large extent which plants we can grow well in the first place.

When you’re choosing plants and designing gardens, keep in mind that there are climatic variations within a geographic region and even within each garden. Your garden’s immediate climate may be different from that of your region overall. Factors such as altitude, wind exposure, proximity to bodies of water, terrain, and shade can cause variations in growing conditions by as much as two hardiness zones in either direction. It is also important to realize that your area’s climate can change over time.

Hardiness is the ability of a plant to survive in a given climate. In the strictest sense, this includes not only a plant’s capacity to survive through winter but also its tolerance of all the climatic conditions characteristic of the area in which it grows. Still, most gardeners refer to a hardy plant as one capable of withstanding cold and to a tender plant as one that’s susceptible to low temperatures and frost.

To help growers determine which plants are best for their regions, in 2006 the National Arbor Day Foundation, using data from 5,000 National Climatic Data Center stations, released an updated version of the 1990 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map. The USDA released an updated map in 2012. Hardiness zone maps divide the United States into 12 climatic zones, based on the average annual minimum temperature for each zone. Zone 1 is the coldest, most northerly region (in Alaska), and Zone 12 is the warmest, most southerly (in Hawaii). If you live somewhere in Zone 6 and a plant is described as “suitable for Zones 5–9" or “hardy to Zone 4,” you can expect the plant to do well in your area. If you live in Zone 3, on the other hand, you should select a more cold-tolerant plant. You can find out which zone you live in by referring to the map. If you access the map online, you can make use of its interactive capabilities to zoom in very specifically on the area in which you live to precisely identify the hardiness zone.

In addition, recognizing that hot weather can also limit plant growth, the American Horticultural Society (AHS) released its AHS Plant Heat-Zone Map, based on 12 years of climatic data ending in 1995. On this map, the United States is divided into 12 zones based on the number of days the region experiences temperatures above 86°F (“heat days”). Zone 1 experiences less than one heat day; Zone 12, over 210 heat days. Use this map the same way you would the Hardiness Zone Map.

You can view the Arbor Day Foundation map and the Heat Zone map at the Web sites of the respective organizations; see Resources.

Natural rainfall is an important factor in which crops you can grow and how to take care of those you do grow. Keep track of the rainfall in your garden with a rain gauge. You can buy a gauge, or simply use an empty tin can—or any straight-sided container—and a ruler. An inch of rain in the can equals an inch of rain on the garden.

Many food and ornamental plants are native to warm climates and can’t withstand freezing temperatures. Others go dormant for winter. Thus, the primary growing season for most North American gardeners is between the last frost in spring and the first killing frost of fall.

Air temperature is only one of the factors that determine whether or not plants will be damaged by a frost. Sometimes when the temperature dips a little below freezing, the air is sufficiently moist for water vapor to condense (in the form of ice crystals) on the ground and on plants. When water condenses, it gives off heat and warms the air around plants, protecting them from extensive damage. On clear, windless, star-filled nights when the forecast calls for near- or below-freezing temperatures, it’s wise to protect plants. Heat is lost rapidly under these conditions, and frost damage often occurs. When temperatures fall more than a few degrees below freezing, frost damage to growing leaves and shoots is likely no matter how humid conditions are.

Frost damages plants when the water in the plant’s cells freezes and ruptures the cell walls. Different plants and parts of plants have different freezing points. Plants that are native to northern regions have many ways of protecting themselves from the cold. Many perennials die down each fall. The roots buried in the insulating soil remain alive to sprout again the next season. Some plants such as kale have cold-tolerant leaves that will survive unharmed under a blanket of snow, but not when exposed to drying winds. Deciduous shrubs and trees drop their leaves each fall and form leaf and flower buds that stay tightly wrapped in many layers and go dormant until spring comes again. Or, like cold-hardy evergreens, they may have a natural antifreeze in their sap that helps prevent them from cold injury.

Frost heaving of soil can also cause problems for gardeners. Soil moves as it freezes, thaws, and refreezes. This action can push newly planted perennials, shrubs, or other plants that don’t have established root systems out of the soil. Mulch heavily around these plants after (not before) the soil freezes to prevent thawing during sudden warm spells in winter or early spring.

Our ancestors understood the role weather played in growing food. They saw that nature gave ample warning of approaching rain, storms, and frost. The sky is filled with weather indicators, especially cloud formations. For example, “When ye see a cloud rise out of the west, straightway cometh the rain” (Luke 12:54) refers to the fact that weather fronts usually move from west to east.

“Rainbow at night, shepherd’s delight. Rainbow in morning, shepherd’s warning” refers to the same phenomenon. A rainbow seen in the evening to the east is caused by the setting sun shining from the west, indicating fair weather in that direction. A morning rainbow, caused by the rising sun from the east, indicates rain to the west, heading your way.

“If the sun goes pale to bed, ’twill rain tomorrow, it is said” is another saying that involves cloud patterns. High cirrus clouds in the west give the setting sun a veiled look. When appearing as bands or mares’ tails, they signal an approaching storm.

Finally, who among us will argue with “Clear moon, frost soon”? Cloud cover acts like a blanket over the earth, keeping temperatures from dipping as low as they would on a clear night.

The skies are not the only aspect of nature filled with weather signs. Animal and plant behavior also indicates changes. Here belong all the sayings about the thickness and color of an animal’s coat, the bark on a tree, or the skin of a vegetable, such as “When the corn wears a heavy coat, so must you.” A related saying is “The darker the color of a caterpillar in fall, the harder the winter.”

Certain animals and plants do respond in a consistent way to a change from a high- to a low-pressure system, which often brings rain. This is why a saying such as “When the sheep collect and huddle, tomorrow will become a puddle” is reliable. “The higher the geese, the fairer the weather,” a saying that applies to all migratory birds, also refers to this phenomenon.

Many plants are sensitive to drops in temperature and to high humidity. “When the wild azalea shuts its doors, that’s when winter temperature roars” refers to the fact that azaleas and rhododendrons draw their leaves in when the temperature drops.

Cold weather lore often merges weather phenomena with common sense. Snow, for example, is known as “the poor man’s fertilizer,” which may be because it acts as mulch, protecting plants and keeping nutrients in the soil that rain would otherwise wash away. Frost is “God’s plough” because it breaks up the ground and kills pests.

Going beyond folk wisdom is phenology, the study of the timing of biological events and their relationships to climate and to one another. Such events include bird migration, animal hibernation, and emergence of insects, and the germination and flowering of plants.

Phenologists have found that many plants and insects within the same region or climate pass through the stages of their development in a consistent, unified sequence. The budding of a given plant, for example, may correlate with the hatching of a particular pest insect. Variations in weather from one year to the next affect the timing of such events, but the order in which they occur tends to remain the same.

As a result, it’s possible to foretell when conditions are right for a crop to germinate or an insect to appear by learning to read the various growth stages of indicator plants. You may want to experiment with phenology in your own yard. For example, you could plant a variety of perennials as indicators that will provide a steady succession of blooms throughout a season. Then observe and record the indicators’ growth phases, along with weather data, the appearance of insects or diseases in your garden, and the progress of food crops.

Sooner or later, patterns will emerge. You may notice that daffodils always begin to bloom when the soil becomes warm enough to sow peas, or that Mexican bean beetle larvae appear at about the same time foxgloves open. You can then use that information in subsequent years to help you decide when to plant peas or when to start handpicking beetle larvae. Your observations may also help you discern if and how the local climate in your area is changing over time.

Melting glaciers and rising sea levels are large-scale outcomes of a changing climate, but what about climate change on a smaller scale? Does climate change affect how plants grow in home gardens?

The answer is yes. Some of the shifts are subtle, but others could be dramatic, depending on where you live. For example, you may find that you can plant zinnias and other tender annuals a week or two earlier in spring than you used to. In many areas, gardeners are enjoying a longer season of garden-ripe tomatoes and delaying the time when they move houseplants back indoors in fall. Perhaps you’ve noticed that local garden centers are now selling trees and shrubs that once were considered too tender to survive through the winter in your area.

These are changes we can celebrate, but the slow-and-steady rise in temperatures has its downside, too. For example, insect pests such as army-worms may become more frequent problems because they can survive winters farther north than in the past, allowing them an earlier start at feeding on your crops in the spring or summer. Climate change may mean that new types of weeds and insect pests will appear in your garden, and new invasive species will infiltrate the woodlands, wetlands, and other natural areas in your community. One example is kudzu, a nonnative vine that has overrun many areas in the South and is now predicted to take hold as far north as southern Canada within the next 10 years.

One form of climate change that many of us can notice in our own gardens and neighborhoods is a shift in seasonal and temperature patterns. This change is verified in data collected nationally including average annual minimum temperature, the basis for determining plant hardiness zones. This climatic data show that most of North America has become significantly warmer in the past 30 years—so much so that portions of many states could now be rated as a warmer zone. Updated hardiness zone maps from the Arbor Day Foundation and the USDA reflect recent data (see Resources and the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map).

A phenological study that compared the date of first bloom of plants in Washington, DC, showed that, over a 30-year period, 89 out of 100 species of plants—including common garden plants such as lilacs and honeysuckle—bloomed earlier in spring (by 4.5 days on average). Other studies indicate that apples and grapes are blooming earlier in the Northeast than they did 50 years ago.

If the area where you garden has a change in hardiness zone or other temperature patterns, is that a good thing or a problem? The answer depends on the region and on what you’re trying to grow. For example, an earlier spring is a boon to northeast veggie gardeners eager to sow their peas and spinach, but for California gardeners and farmers, it means the hot, dry summer will start even sooner—forcing them to irrigate more than ever. And warming can be bad news for anyone who grows perennials such as hostas that require a few weeks of winter cooling (below 40°F) as a rest period in their annual cycle.

Some areas may benefit from warming because they won’t have any frost periods at all, or fewer incidents of unexpected freezes—in Florida, for instance, where the orange crop is sometimes devastated. (Of course, global climate change also means extreme fluctuations, so this benefit could also backfire.) And in the grand scale of things, if seasonal plants live a week or two longer each year, they will do an even better job of consuming carbon dioxide, which could help counteract global warming.

In broad terms, for agriculture worldwide, the warming trend will probably increase yields in colder climates for a while and damage those in warmer regions. It’s a mixed bag of good and bad news.

Back in the home garden, what if you can now grow a crape myrtle, formerly considered a southern beauty, in Pennsylvania or Connecticut? A previously unavailable plant may be a horticultural delight, but responsible gardeners should look carefully at whatever we introduce, whether exotic (from another country) or native, to other areas of this country. When you bring in a new plant, watch that it doesn’t pop up in a nearby field or spread into the woods. Look for insects you may not have seen before that came with it and may now affect other plants. One gardener’s intriguing new groundcover could turn out to be the next Japanese knotweed, kudzu, or giant hogweed.

Windstorms, snowstorms, floods, and other kinds of bad weather have always been with us, but never as fully tracked, recorded, and reported as in the past 100 years. And all of that data shows that weather patterns are tending toward more rapid and extreme changes, including more frequent tornadoes and severe thunderstorms, and also record-breaking cold temperatures at unusual times. While freeze damage to plants may not seem logically connected to global warming, it’s all related. For example, consider what happened in the spring of 2007, when the East Coast hit some record warm spring temperatures much earlier than normal. The plants broke dormancy, began to leaf out, and buds swelled. Then in April an abnormally deep freeze killed plants over a wide area. In preceding decades, a late freeze like that one wouldn’t have done much harm, but in 2007, the plants were way ahead of themselves. Many plants died, became stunted, or produced fewer leaves, flowers, or fruit. For some gardeners, that meant no flowers on the rhododendron or magnolia. For others—and for many commercial orchardists—it meant no apple crop.

As we experience global climate change, or even simple weather extremes from one season to the next, smart gardeners observe and adapt. Use these three basic guidelines to help guide your gardening and landscaping decisions.

Don’t discount the potential for a cold year. Be cautious about plant choices. A trend to milder winters is not necessarily the signal to start planting marginally hardy species in your windy front yard, because occasional harsh winters may still occur. Perhaps it’s a good time to start a log of weather patterns in your own yard, a record that will be more meaningful as years go by. Meanwhile, if you are going to bet on a warming trend, prepare to protect that “iffy” plant with a winter shelter. Or, for your first experiments with tender specimens, choose sheltered spots on the protected side of your house.

Count on extremes, and prepare. Most scientists predict more droughts, harder rains when they come (leading to flooding), and windstorms—if not hurricanes. For a gardener, that means planning water-wise gardens (see the Water-Wise Landscaping entry), designing for drainage and stormwater runoff, keeping the soil covered, and figuring out how to stake or cover large plants before storms occur.

Stick with good gardening principles. They’re even more important in harder times. Take care of the soil first, recycle yard waste and use organic matter, match the plants to the site, and provide the care they need. Since climate change may also bring new pests and diseases to your area, avoid putting all your bets on any one food crop or a long hedge of a single species of tree or shrub. Instead, diversify. Plant a mixed hedge, and sow small plots of many different crops in your vegetable garden. That way, when a new pest or disease strikes, it won’t cause a crisis in your garden.

In 2007, the US Geological Survey (USGS) and the University of Arizona initiated a nationwide program to begin collecting data that will help federal and university scientists analyze how climate change is affecting the timing of key stages of plant development, such as the date when dandelions or Virginia bluebells start to bloom, or when the native trees in a region start to leaf out. “Citizen scientists” (home gardeners, schoolchildren, and others) across the country are the key to this project, collecting phenological data on nearly 4,000 species of plants. Participation is free and easy to do: Simply register at the Project Bud-Burst Web site and begin submitting periodic reports. The data collected will help USGS scientists track climate variation at the local, regional, and national level, and analyze the impact of climate change by comparing the Project Bud-Burst data to historical records.

Fast, tough, and common—that’s all it takes to earn a plant the name weed. But any plant growing in the wrong place—especially if it’s growing there in abundance—is a weed. Maple tree seedlings that sprout between your rows of lettuce and radishes are weeds. So is the Bermuda grass that keeps invading your perennial beds from your lawn.

Some weeds can be useful as well as a nuisance. For example, purslane is a weed that often sprouts in vegetable gardens, yet you can eat the leaves of this weed in salads. The cultivated species of purslane—known as rose moss (Portulaca grandiflora)—has large, colorful flowers and is prized as a bedding plant for warm, sunny places. And while honeysuckle vines can cause considerable damage as they twine around tree trunks and branches, they might serve well as a groundcover for a bank that’s too steep to mow.

Weeds make a lawn, garden, or landscape look untidy and neglected. But aesthetics aside, there are other important reasons for keeping your weeds in check. Weeds compete for water, nutrients, light, and space. The competition can weaken your plants and reduce your harvest. They grow fast, shading out less vigorous plants. Weeds serve as alternate hosts or habitats for insects and diseases. For example, aphids and Japanese beetles on smartweed can move from the weeds onto your food and landscape plants.

Some weeds have poisonous parts, such as pokeweed berries or poison ivy leaves, stems, and roots. A few weeds secrete chemicals from their roots that are toxic to other plants. Garlic mustard falls in this category, which contributes to its ability to outcompete wildflowers and other native plants in eastern and midwestern woodland habitats.

Just like flowers, weeds may be annuals, biennials, or perennials. Annual weeds, the easiest to control, complete their life cycles in a year or less. Summer annuals sprout in spring and go to seed in fall; winter annuals sprout in fall, live over winter, and go to seed by spring or summer. Summer annuals such as crabgrass, giant foxtail, pigweed, and lamb’s quarters will be your biggest weed problem in the vegetable garden. Winter annual weeds, such as chickweed and henbit, will sprout along with fall plantings of crops like lettuce and radishes. It’s easy to hand-pull or cultivate these weeds in late fall or even on a warm winter day so they won’t have a chance to go to seed the following season.

Biennial weeds, such as Queen Anne’s lace, form only roots and a rosette of leaves the first year, then flower and set seed the second year. Perennial weeds, which live for more than 2 years, reproduce not only by seed but also by roots, stems, and stolons. Gardeners dread perennial weeds such as quackgrass or ground ivy, which spring into new life from an overlooked fragment of stem or root.

A single weed can produce as many as 250,000 seeds. Though some seeds are viable for only a year, others can lie dormant for decades, just waiting for their chance to grow. Buried several inches deep, the lack of light keeps them from germinating. But bring weed seeds to the surface, and they’ll germinate right along with your flower and vegetable seeds.

Even if you’re diligent at hoeing and pulling weeds, more seeds arrive—by air, by water runoff, and in bird droppings. You may accidentally introduce weeds by bringing seeds in on your shoes, clothing, or equipment or in the soil surrounding the roots of container-grown stock. Even mulches spread on garden beds or straw that’s spread to protect a newly seeded lawn area may be contaminated with weed seed. Grass seed itself, unless certified as weed-free, may contain seeds of undesirables.

Keeping weeds from getting started is easier than getting rid of them. Here’s how.

After preparing garden soil for planting, let it sit for 7 to 10 days. Then slice off newly emerged weeds with a hoe, cutting them just below the soil surface and disturbing the soil as little as possible. If you have time, wait another week or so and weed again. This tactic puts a considerable dent in the reservoir of surface weed seed that could germinate and cause problems later in the season.

After preparing garden soil for planting, let it sit for 7 to 10 days. Then slice off newly emerged weeds with a hoe, cutting them just below the soil surface and disturbing the soil as little as possible. If you have time, wait another week or so and weed again. This tactic puts a considerable dent in the reservoir of surface weed seed that could germinate and cause problems later in the season.

Cover the soil with black plastic to kill existing weeds and stop seeds from germinating. (Don’t leave plastic in place for more than a few months; soil needs air and water to remain healthy.)

Cover the soil with black plastic to kill existing weeds and stop seeds from germinating. (Don’t leave plastic in place for more than a few months; soil needs air and water to remain healthy.)

Use weed-free mulches like pine bark or shredded leaves. See the Mulch entry for more information on mulches.

Use weed-free mulches like pine bark or shredded leaves. See the Mulch entry for more information on mulches.

Use vertical barriers, such as wood or metal edgings, between lawn and garden areas to prevent grass from infiltrating.

Use vertical barriers, such as wood or metal edgings, between lawn and garden areas to prevent grass from infiltrating.

Be a good housekeeper in your garden by pulling weeds before they set seed. Police nearby areas, too, or weed seeds from those spots may blow onto your freshly prepared seedbeds.

Be a good housekeeper in your garden by pulling weeds before they set seed. Police nearby areas, too, or weed seeds from those spots may blow onto your freshly prepared seedbeds.

Switch to drip irrigation. By directing water right to plant roots and leaving the areas between rows or plants unwatered, this type of watering discourages weed seed germination and weed growth.

Switch to drip irrigation. By directing water right to plant roots and leaving the areas between rows or plants unwatered, this type of watering discourages weed seed germination and weed growth.

Let the sun’s heat weed your vegetable garden by solarizing the soil. Covering bare soil tightly with clear plastic for several weeks can kill weed seeds in the top few inches of the soil. For details on this technique, which also helps reduce soilborne diseases and pests, see Soil Solarization.

Let the sun’s heat weed your vegetable garden by solarizing the soil. Covering bare soil tightly with clear plastic for several weeks can kill weed seeds in the top few inches of the soil. For details on this technique, which also helps reduce soilborne diseases and pests, see Soil Solarization.

The bigger your weeds get, the more difficult they are to control. Get into the habit of a once-a-week weed patrol to cut your weed problem down to size. Using the right tools and techniques also will help to make weeding a manageable—maybe even enjoyable—task.

Hand-pulling weeds is simple and effective. It’s good for small areas and young or annual weeds such as purslane and lamb’s quarters. Using your hands allows you to weed with precision, an important skill when sorting the weeds from the seedlings. For notorious spreaders like ground ivy, the only choice for control is to patiently hand-pull the tops and sift through the soil to remove as many roots as you can find.

Short-handled tools such as dandelion forks (sometimes known as asparagus knives), pronged cultivators, and mattocks are good for large, stubborn weeds, especially in close quarters such as among perennials. Use these tools to pry up tough perennial weeds. Hand weeders come in all shapes, and everybody has a favorite. If one type feels awkward, try another.

If the weeds you pull haven’t yet set seed, recycle them: Leave the weeds upside down on the soil to dry, then cover with soil or mulch. If they have gone to seed, add them to the compost pile only if you keep the pile temperature high (at least 160°F). Otherwise the weed seeds will survive the composting process, and you’ll spread weed problems along with your finished compost. See the Compost entry for instructions on keeping a compost pile hot.

A hoe is the best tool for weeding larger areas quickly and cleanly. Use it to rid the vegetable garden of weeds that spring up between rows. When you hoe, slice or scrape just below the soil surface to sever weed tops from roots. Don’t chop into the soil—you’ll just bring up more weed seeds to germinate. There are hoes designed for many purposes other than weeding. Use an oscillating hoe, circle hoe, or other hoe that’s especially designed for weeding, and keep the hoe blade sharp. Hoeing kills most annual weeds, but many perennial weeds will grow back from their roots. Dig out these roots with a garden fork or spade. See the Tools and Equipment entry for help in choosing the right tools.

A rotary tiller is not helpful for weeding, because tilling has detrimental effects on soil structure and will bring up more weed seeds in the process. Also, tilling perennial weeds chops their rhizomes into small pieces, each of which will then sprout into life as a new weed.

One of the best low-effort ways to beat weeds is to block their access to light and air by covering the soil surface with mulch. A 3- to 4-inch layer of mulch smothers most weeds, and weeds that manage to poke through are easy to pull.

Black plastic mulch can practically eliminate weeding in the vegetable garden. Spread the plastic tightly over the soil surface and bury the edges. Cut small slits through the plastic so you can slip transplant roots through into the soil below. Remove the plastic at the end of the growing season to let the soil breathe. You can use biodegradable materials such as newspaper or corrugated cardboard to temporarily suppress weeds, tilling them into the soil at the end of the season. See the Mulch entry for more information on organic and black plastic mulches.

A living mulch of a low-growing grass or legume crop seeded between rows of plants in your vegetable garden can keep down weeds and improve the soil’s organic matter content at the same time. See the Cover Crops entry for suggestions on planting living mulches in your garden.

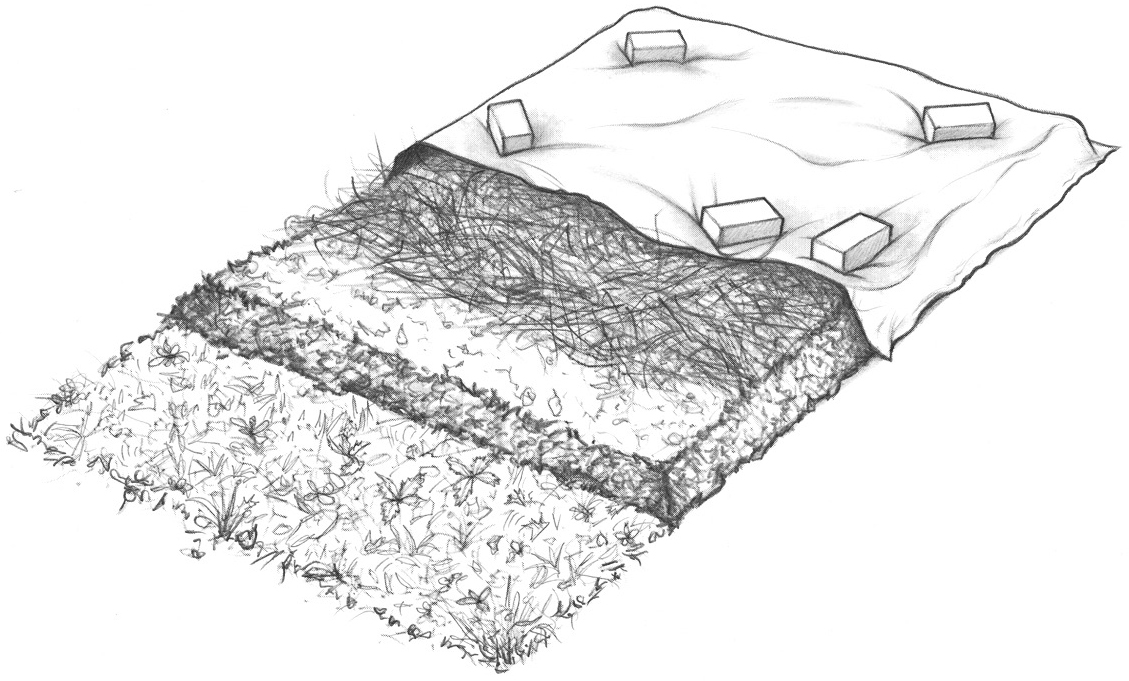

Even stubborn perennial weeds such as poison ivy or field bindweed will succumb to being smothered by a multilayered mulch treatment, as shown in the illustration below. Start by using a mower or string trimmer to cut the weeds as close as possible to the soil surface (but skip this step for poison ivy). Leave the cut material in place and cover it with 2 to 3 inches of compost or manure. Next, spread a thick layer of dry organic mulch such as hay, wood chips, or shredded leaves. Top the mulch with an opaque, impenetrable cover: Black plastic, old carpeting, or a 2-inch-thick layer of newspaper work well. Leave the mulch and heavy cover in place for the season. The following spring, pull back one corner of the cover and dig down to the soil to check for weed roots. If the roots aren’t dead yet, recover the area. Two years under this kind of cover will kill virtually any weed.

Some gardeners attempt to avoid weed problems around trees and shrubs by spreading landscape fabric over the soil surface under the plants, but this can create as many problems as it solves. The usual practice is to cover landscape fabric with an attractive organic mulch, but weed seedlings can take root in the mulch. Also, roots of desirable plants may grow up into the fabric, reaching for the loose mulch on top; then, in times of drought, these plants suffer. Ultimately, these materials do degrade and need to be replaced, so if tree or shrub roots have grown through the fabric, it can be very difficult to dislodge. Before you decide to use landscape fabric for weed control and prevention, experiment with it in one small area—where it won’t be too hard to remove if it doesn’t work out.

When weeds overwhelm you, and your aching back says it never wants to see another wheelbarrow of mulch, think of the good side of weeds.

•Weeds produce quick cover for land that’s been laid bare by fire, flood, or construction.

•Weedy areas provide a haven and an alternate food source for many of the beneficial insects that prey on garden insect pests.

•Songbirds and other wildlife depend on weed seeds as a food source.

•Weeds are sources of drugs and dyes. Ragweed produces a green color; dock and smartweed, yellow. Colts-foot is used for cough syrup, castor bean for castor oil. Oil from jewelweed soothes poison ivy rash.

•Dried flowers, seedpods, and stems of many weeds, especially weedy grasses, make attractive fall and winter bouquets.

Mulching perennial weeds. Covering a weedy area with organic matter, mulch, and a heavy opaque cover weighted with bricks or rocks will eventually solve even the toughest weed problems.

One way to reclaim an area that is covered with tough weeds like quackgrass is to smother them out over the course of a year with dense plantings of buckwheat. This cover crop grows so quickly and thickly that it can out-compete almost any weed when it’s carefully managed.

Here’s one case where you may want to till a weed-covered site to prepare an even seedbed for the buckwheat seed. Starting in spring, sow buckwheat at a rate of 3 to 5 ounces per 100 square feet. Several weeks later, once you see flowers on the buckwheat plants, cut them down close to the soil surface. Let them dry out for a day or two, then till or dig them in and replant in the same way. Continue growing, cutting, and replanting buckwheat until frost kills off a crop. At that point you can plant the area with your desired plants, such as wildflowers or perennials. Or if it’s a vegetable garden, sow a winter cover crop that you can turn under in early spring, and plant your vegetables after that.

Just as weeds compete with your garden and landscape plants for water, food, and growing space, you can encourage your desirable plants to crowd out weeds. For example, spacing vegetable and flower plants closely in beds decreases the time until the leaves form an effective light-blocking canopy, and that means fewer bouts of weeding for you.

Reduce weed growth in your lawn by setting your lawn mower blade a notch or two higher. Taller grass is generally healthier and lets less light reach the soil.

One important development in organic weed control is corn gluten meal. Corn gluten meal, a by-product of corn processing that’s often used to feed livestock, inhibits the germination of seeds—bear in mind, once the weeds have gone beyond the sprout stage, corn gluten will not affect them. Also, corn gluten doesn’t discriminate between seeds you want to sprout and those you don’t want, so avoid using corn gluten meal where and when you’ve sown seeds. It works best in established lawns and perennial beds. You can find corn gluten meal for sale at almost any garden center. Follow package instructions when applying.

There are a few types of weed-killing sprays that are acceptable for use in organic gardens. The active ingredients in these products are fatty acids or vinegar; you can find these products at some garden centers or through mail-order companies that specialize in organic gardening supplies. These herbicides provide effective spot control for annual weeds and grasses but probably won’t work well for controlling tough perennial weeds. Always follow label safety precautions and application instructions when you use these herbicides. Some vinegar-based herbicides contain a higher percentage of acetic acid than household vinegar, and contact with these products can burn eyes and skin.

Some organic gardeners have traditionally relied on salt to kill weeds. However, salt will affect soil balance and can harm your garden plants as well. Only use salt in areas where you don’t want any plants to grow, such as between cracks in a patio.

Two heat-based methods also offer organic gardeners ways to deal with weeds. For those cracks in the sidewalk or driveway, pouring boiling water on weeds can be enough to scald them out of existence—just be careful not to scald yourself while applying this technique.

Flame weeders use a propane torch with a long nozzle to scorch weeds and can be an effective way to stop young weeds before they get out of control. The key to flame weeding is to simply scorch weeds until they wilt—there’s no need to burn them completely. Flame weeding should only be done on a calm (not windy) day and with water close at hand to douse any stray flames that pop up. Never use a flame weeder in dry conditions or where there is lots of dry tinder. And don’t use flames on poison ivy or its kin—smoke can carry the volatile oils to skin, eyes, and lungs!

Wildflowers bring casual good looks and sturdy dispositions to the garden, linking the cultivated landscape to the natural environment around it. Wildflowers are at home in informal shade gardens, sunny meadows, and formal borders, and many stars of the perennial garden are tamed and cultured versions of their wilder kin. Some native wildflowers, such as garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), bee balm (Monarda didyma), and purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), have grown in gardens for years. But others weren’t commonly cultivated in this country until recently, although they were widely grown and hybridized in Europe. Ironically, today we grow European-produced cultivars of many American wildflowers, such as goldenrods and asters.

Wildflowers are available as containerized or bare-root plants from nurseries across the country. While reputable nurseries propagate the plants they sell, a few less-scrupulous dealers offer plants collected from the wild. If you buy collected wild-flowers, you could be depleting the population of these plants in the wild.

Fortunately, the growing popularity of wild-flowers and their cultivars as garden plants has brought these plants into mainstream nursery production, and the outcry among gardeners against wild-collected plants means that this problem is not as common as it once was. Use this checklist to make sure you’re buying nursery-propagated plants.

Cultivars, such as Echinacea purpurea ‘Leuchtstern’ (sold as Bright Star), are always nurserypropagated. To be safe, buy the cultivar (rather than the species) if one is offered.

Cultivars, such as Echinacea purpurea ‘Leuchtstern’ (sold as Bright Star), are always nurserypropagated. To be safe, buy the cultivar (rather than the species) if one is offered.

Don’t buy plants that look like they were just dug out of the ground and stuffed into nursery pots. Battered or wilted leaves, leaves growing in unlikely directions, and plants that are too big for their pots but are not pot bound are a few telltale signs. Before you buy such a plant, verify its source.

Don’t buy plants that look like they were just dug out of the ground and stuffed into nursery pots. Battered or wilted leaves, leaves growing in unlikely directions, and plants that are too big for their pots but are not pot bound are a few telltale signs. Before you buy such a plant, verify its source.

Beware of the phrase “nursery-grown.” It doesn’t necessarily mean that the plants are nursery-propagated; they may have been collected, then grown on in the nursery for a couple of years.

Beware of the phrase “nursery-grown.” It doesn’t necessarily mean that the plants are nursery-propagated; they may have been collected, then grown on in the nursery for a couple of years.

Wildflowers that take a long time to propagate are the most likely victims of collection from the wild. Be especially careful to determine the source of trilliums, trout lilies, and other spring woodland wildflowers.

Wildflowers that take a long time to propagate are the most likely victims of collection from the wild. Be especially careful to determine the source of trilliums, trout lilies, and other spring woodland wildflowers.

Don’t buy native orchids such as ladyslipper unless they’re from a reputable nursery that guarantees they’re nursery propagated. One clue is that they’ll be quite pricey, since it’s challenging to propagate native orchids in commercial quantities.

Don’t buy native orchids such as ladyslipper unless they’re from a reputable nursery that guarantees they’re nursery propagated. One clue is that they’ll be quite pricey, since it’s challenging to propagate native orchids in commercial quantities.

Be wary of inexpensive wildflowers or quantity discounts offered by mail-order nurseries.