Diseases of the Jill

Estrogen-Induced Anemia

Etiology

Aplastic anemia is a clinical pathologic finding associated with prolonged estrus in female ferrets. Given the high percentage of jills that are neutered at a young age, the clinical condition has correspondingly decreased. If the jill is not bred, she will usually remain in estrus for the duration of the breeding season, develop anemia, and may die. The bone marrow depression is attributed to prolonged exposure of hematopoietic tissue to estrogens [1–3]. Investigators have speculated on the mechanisms by which estrogens may suppress the myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic cell lines [2,4]. Severe bone marrow depression was experimentally produced by administering high levels of exogenous estrogen. The treatment produced suppression of all blood cell populations in ferrets, regardless of gender or ovariohysterectomy [1].

Epizootiology and Prevention

Female ferrets staying in estrus longer than 1 month are at risk of developing estrogen-induced anemia. The incidence of aplastic anemia is highest during the breeding season, occurring in 50% of females experiencing prolonged estrus [5]. The loss of 30% of estrous females in a colony was reported during one breeding season [1]. Aplastic anemia may be avoided by spaying nonbreeding females at 6–8 months of age. Commercial breeders spay and neuter ferrets at 6 weeks prior to their sale. If females become estrus, they may be induced to ovulate by the injection of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), as described earlier [1,4] (see Chapter 8). The injection may be repeated when a female returns to estrus 40–60 days later. Jills should not be allowed to remain in estrus for longer than 1 month. The use of vasectomized hobs is another option for preventing prolonged estrus in ferrets [6]. Breeding of estrous ferrets will also prevent aplastic anemia.

Clinical Signs

Initially, there is a leukocytosis followed by leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. There is also coagulopathy, distinct from the attendant thrombocytopenia, that involves hepatic dysfunction [2].

Although ferrets are considered to be highly susceptible to the effects of estrogens [2], surviving experimental females were found to be less sensitive [1]. The neutropenia may predispose females to bacterial infections such as pyometra, vaginitis, and bronchopneumonia [1,3].

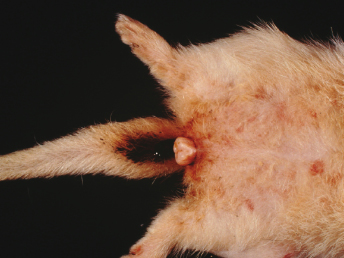

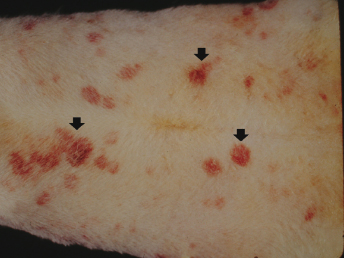

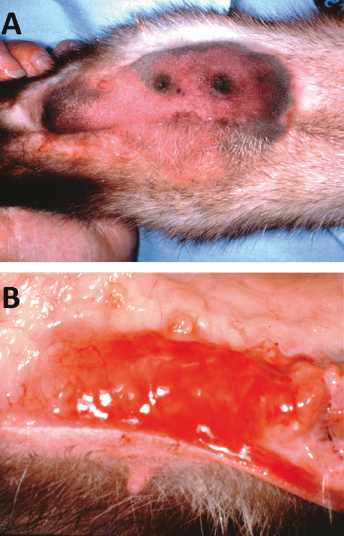

The clinical signs of bone marrow suppression in ferrets are combined with those seen during estrus. Ferrets have a bilateral symmetric alopecia of the ventral abdomen and tail area, weight loss, vulvar enlargement with a serous to mucopurulent discharge, and possibly a superficial perivulvar dermatitis. Jills experience anorexia, depression, and lethargy, and may also have pneumonia, pyometra, systemic bacterial infection, posterior paralysis, or melena (Fig. 15.1). Examination reveals pale mucous membranes and possibly a systolic murmur, consistent with anemia [3]. Hemorrhage is the most common cause of death, and coagulopathy is manifested as petechiae or ecchymoses of the skin, buccal mucosa, and conjunctiva, or as melena from gastrointestinal hemorrhage (Fig. 15.2). Subdural hematoma of the spinal cord or brain may result in posterior paralysis or ataxia and depression [1,4]. Ferrets are typically in estrus for 2 months before death occurs [4].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bone marrow depression is based on the history and clinical presentation of an estrous female (an enlarged, edematous vulva), with a packed cell volume (PCV) less than 20%. Vaginal cytology of female ferrets in prolonged estrus consists of cellular debris, numerous neutrophils and bacteria, and occasional erythrocytes [7]. Secondary bacterial infections, such as pyometra and pneumonia, as well as central nervous system (CNS) signs, may confuse the diagnosis of the primary disease.

Clinical Pathology

Sherrill and Gorham [4] studied alterations in the hematologic parameters of ferrets in prolonged estrus. They recorded initial thrombocytosis and neutrophilia followed by thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, anemia, and hypocellular bone marrow. Females maintained platelet counts of 50,000/μL, with some counts decreasing to 20,000 platelets/μL and less. Hemorrhage occurred when platelet counts fell below 20,000/μL. Authors have noted platelet counts less than 50,000/μL in ferrets given exogenous estrogens [1]. Others reported decreased platelet numbers in all six pet ferrets they examined [3]. One had a thrombocyte count of less than 7000/μL. Another was euthanatized but the remaining jills died, despite treatment.

At some point in estrus, all female ferrets will have at least a mild anemia. Initially, it is normocytic normochromic, and may progress to a macrocytic hypochromic anemia. Reticulocyte counts provide evidence of attempted bone marrow regeneration and an assessment of the degree of anemia present; nucleated red blood cells (RBCs) also have been reported as a response to regenerate RBCs [3]. Clinical signs are not apparent until the PCV falls below 20% and/or the platelets below 50,000/μL; PCVs of less than 10% have been recorded in fatal cases. The low hematocrit, with concurrent low platelets, is accompanied by a decrease in the total serum protein concentration, even in cases with significant dehydration [3]. Mild anemia is attributed to erythroid hypoplasia, but severe anemia results from a combination of hypoplasia plus hemorrhage caused by the thrombocytopenia.

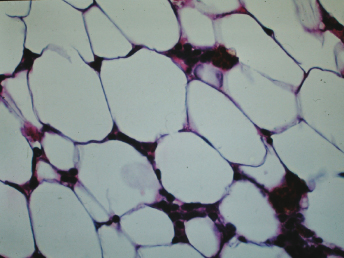

In severely affected animals, bone marrow cytology reveals decreased erythroid, granulocytic, and megakaryocytic precursors. The hypocellular bone marrow of ferrets in prolonged estrus is composed of 10–20% hematopoietic cells, with the remainder being adipocytes, lymphocytes, RBCs, and hemosiderin-containing macrophages [4].

Pathology

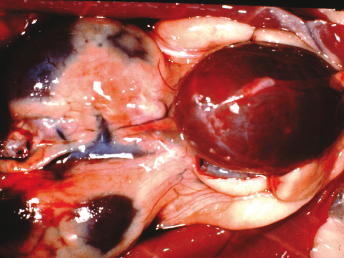

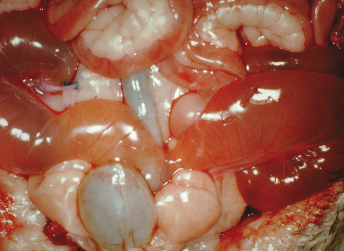

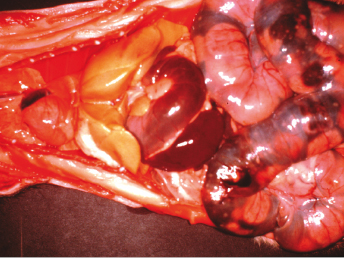

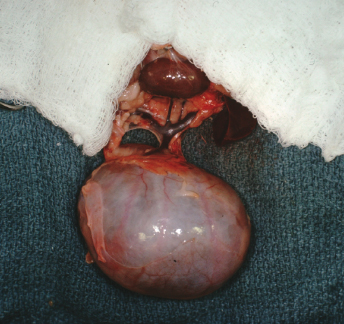

The most consistent necropsy findings of ferrets with aplastic anemia are pale tissues and hemorrhages in various tissues. The bone marrow is light tan to pale pink or light red. The liver and mucous membranes are markedly pale. Body weight is generally below normal. The blood is thin and watery, and there is evidence of hemorrhage in various tissues. Frank blood may be found in the lumen of the stomach and in the small and large intestines. Subcutaneous (SQ) and subendocardial ecchymoses and petechiae are common findings. Hemorrhage has also been observed in the omentum, urinary bladder, uterus, and periovarian adipose tissue, (Fig. 15.3). Subdural hematoma or hematomyelia is observed at the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels of the spinal cords of animals with neurologic signs. Uterine changes from hydrometra (Fig. 15.4) to pyometra (e.g., Escherichia coli) or mucoid to mucopurulent vaginitis (e.g., Corynebacterium sp.) have been reported [1]. A suppurative bronchopneumonia caused by Klebsiella sp. has also been diagnosed [3].

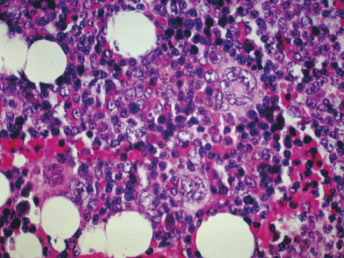

The most striking histopathologic change is the hypocellularity of the bone marrow (Fig. 15.5 and Fig. 15.6) [1]. There is no significant hematopoiesis of either the erythroid or granulocytic cell series, and megakaryocytes may be absent. The changes in the bone marrow reflect those in the peripheral blood. There are numerous adipocytes and variable numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

Hemosiderosis, indicative of hemorrhage, is seen in the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, and lung. Suppurative bronchopneumonia may be diagnosed [3]. There is mild hepatic lipidosis to significant centrilobular fatty degeneration and possibly diffuse small areas of extramedullary hematopoiesis [3,4]. Examination of splenic tissue reveals either diminished or no evident extramedullary hematopoiesis.

As mentioned earlier, hydrometra, mucometra, or pyometra may be present. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia may be diagnosed frequently [4,8]. Multiple follicles can be found in the ovaries.

Treatment

By the time of clinical presentation, jills are often too severely affected to survive, even with therapy. The prognosis must remain guarded, because the ferret's response to any procedure correlates with the length of estrus before beginning treatment. The first objective is to remove the source of endogenous estrogens, with the condition of the animal dictating whether this is done by medical or surgical means, or by both. Unless the animal is intended for use in breeding, an ovariohysterectomy is the most expedient method of removing the estrogenic activity. If the jill's PCV and platelet count are low, blood replacement may be necessary to stabilize the animal for surgery. Care must also be taken to ensure minimal blood loss or hemorrhage during the surgical procedure. It has been determined that ferrets have no discernible blood groups, and therefore ferrets can receive multiple (at least three and probably more) blood transfusions from the same donor without untoward effects [9].

One female with a PCV of 7% was spayed and then transfused with 10 mL fresh whole ferret blood containing 1 mL sodium citrate via a 23-gauge jugular catheter [5]. This female had been in estrus for more than 4.5 months prior to presentation. The ferret eventually recovered after extensive therapy involving anabolic steroids, corticosteroids, amoxicillin, a high-calorie diet, B vitamins, an attempted femoral intramedullary bone marrow transplant, and a total of 13 blood transfusions over a 5-month period. Signs of nonregenerative anemia persisted for over 3.75 months in this jill [5].

The prognosis and need for blood replacement therapy can in part be judged by the hematocrit of the affected ferret at the time of presentation. Ferrets with a PCV of 25% or more can usually be treated to cycle out of estrus and further therapy is not required. If the PCV is 15–25%, then blood replacement may be required and the prognosis is less favorable. If the PCV drops below 15%, the prognosis is guarded to poor and multiple blood transfusions are required.

Ferrets with less severe anemia may be cycled out of heat by administering an intramuscular (IM) injection of either 20 μg GnRH (Cystorelin®, Merial, Duluth, GA) or 50–100 IU hCG. These agents may be used 10 or more days after the onset of estrus, with ovulation occurring 35 hours later. Vulvar swelling and turgidity should diminish within 1 week of the injection, and signs of estrus should disappear by 20–30 days post injection [1,4]. A jill will remain anestrus for a pseudopregnancy of 40–45 days. If the jill remains in estrus, the injection of either hCG or GnRH may be repeated. Multiple injections of GnRH in ferrets, during one or over several consecutive or subsequent estrous periods can, in our experience, sensitize the ferret to the drug. The sensitized ferret can therefore develop anaphylaxis shortly after administering GnRH. Clinical signs consist of rapid pulse, panting, cyanotic mucous membranes, and lateral recumbency. Immediate treatment with an antihistamine (Benadryl, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) SQ ameliorates clinical signs within minutes (See also Chapter 11). Megestrol acetate has been used to delay estrus [10], but its use is discouraged because of the risk of pyometra. The use of tamoxifen citrate, an antiestrogenic drug for women, may be contraindicated, because it has purported estrogenic activity in ferrets [1]. Supportive care in the form of corticosteroids, anabolic steroids, B vitamins, antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections, and blood transfusions is an important adjunct to the removal of endogenous estrogens. Ovariohysterectomy is indicated after the jill is out of estrus and no longer severely anemic.

Ovarian Remnant Syndrome

Etiology

The syndrome occurs with incomplete removal of the ovary during a routine ovariohysterectomy of jills.

Epizootiology and Control

The syndrome is due to inadequate surgical exposure of the ovarian pedicles, resulting in improper placement of clamps and ligatures. The risk is higher in younger ferrets (<8 weeks) due to inadvertent loss of the ovary in the abdominal cavity [11].

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs may be more evident during breeding season. During the breeding cycle, the ovarian remnant is more active in secreting sex hormones. If the secretion of estrogen-related hormones is of sufficient quantity and duration, bone marrow suppression and severe anemia may result. Vulvar enlargement and alopecia may be evident [12]. The primary differential diagnosis in affected ferrets is adrenal disease [13]. An adrenal panel, ultrasonography, or exploratory laparotomy are useful in establishing an accurate diagnosis [14].

Treatment

Several treatment modalities have been described to suppress estrus in ferrets. These include proligestone (a progesterone) given 50 mg SQ; repeat in 7 days if no clinical response with 25 mg SQ. hCG is administered at 100 IU IM; repeat in 14 days if no response. GnRH (Cystorelin®) is administered at 20 μg SQ or IM. A synthetic GnRH, Buserelin, can also be used: 0.25 mL IM, which is repeated in 14 days if initial treatment doesn't abate estrus. Caution is advised with repeated treatment with hCG because of increasing the likelihood of antibody to the hormone, which decreases the effectiveness of treatment and may increase the possibility of allergic reactions with subsequent treatments. There is some concern that repeated treatments with this drug may predispose to ovarian tumor development. Surgical removal of the ovarian remnant is the treatment of choice. If possible, surgery should be performed when the jill is under estrogenic stimulation (i.e., breeding season), allowing easier visualization of ovarian tissues. Examination of the entire abdomen is recommended because of possible seeding of ovarian tissue [11].

Mastitis

Acute mastitis in the jill is a common cause of constant restlessness and crying in a young litter. Acute mastitis may occur at any time during lactation, but is most common the first few days after whelping. Mastitis can be caused by various bacteria, including hemolytic E. coli, other coliforms, or gram-positive cocci, including Staphylococcus aureus.

Epizootiology and Control

Organisms inducing mastitis in cattle (and probably ferrets) are generally acquired from the area around the teat canal [15]. In an outbreak of hemolytic E. coli mastitis in ferrets, isolation of the organism from rectal swab specimens from clinically normal ferrets suggests that the E. coli is part of the normal bacterial flora of the ferret colon [16]. The high level of coliform contamination in the perineal area may have contributed to the early involvement of the inguinal glands reported in this study. Hemolytic E. coli (of the same serotype, O4:K23:H5, from the mammary gland, rectal area, and blood) isolated from the oral cavity of suckling kits may also serve as another mode of transmission to unaffected glands and to other jills via cross-fostering [16]. Coliform mastitis is not highly contagious in cattle, and infection usually results from environmental contamination such as organisms in sawdust bedding [17,18]. In a large epizootic of mastitis associated with food poisoning in mink resulting from S. aureus and E. coli, the suspected cause was meat from a septicemic bovine carcass fed prior to the epizootic [19]. Humans can also carry E. coli and S. aureus, and may be considered as a possible source of infectious microorganisms [20].

Cows are most susceptible to coliform mastitis at or shortly after parturition [21,22]. Similarly, in ferrets, affected jills are usually in the early stage of lactation. Bovine milk contains an iron-binding protein, lactoferrin, which inhibits multiplication of bacteria with high iron requirements. Lactoferrin activity is highest in the nonlactating cow and is lost just before parturition [23]. The udder is resistant to coliform infection during the nonlactating period, which coincides with the period of highest lactoferrin activity. This same activity may be present in ferret milk, and may be a factor in determining the time of onset of infection.

Clinical Signs

Swelling, discoloration, firmness, and tenderness of affected mammary glands are initially observed (Fig. 15.7A,B). The swelling of affected tissue progresses rapidly, and adjacent glands frequently become involved. Affected jills become anorectic and lethargic, and no longer nurse their young; if the kits are left unattended, many will die. Systemic signs in jills are often seen and include pyrexia, diarrhea, nasal discharge, pulmonary rales, fulminant septicemia, and death. The rapid progression of the disease may be attributable to the rapid multiplication of E. coli in tissues, with the release and dissemination of endotoxin. At least two toxins are involved in the pathogenesis of E. coli infection in the cow [24].

Diagnosis and Pathology

Many E. coli-associated extraintestinal diseases, including gangrenous mastitis, pyometra, vaginitis, pyelonephritis, omphalophlebitis, and septicemia, have been reported in the ferret [25]. Most common among these is a severe mastitis characterized histopathologically by coagulative and liquefactive necrosis of the mammary tissues and adjacent fat, muscle, and skin [16]. During the course of clinical investigations, our laboratory archived E. coli isolates from diarrheic feces and diseased tissues (mammary gland, uterus, and brain) from ferrets over a 10-year period. Fifteen hemolytic E. coli isolates were collected from the following sites: milk (n = 5), feces (n = 5), vagina (n = 2), urine (n = 1), blood (n = 1), and brain (n = 1). All 15 isolates were beta-hemolytic E. coli and contained α-hemolysin (hlyA), cnf1, and the P pilis (pap1). Seven of the cfn1-positive isolates were tested and shown to have a cytopathic effect on HeLa cell monolayers. Isolates were negative for several other virulence factors, including heat-labile enterotoxin, st, cnf2, and eae. Serotypes included O2:H4 (five isolates), O6:H− (six isolates), O4:H− (three isolates), and O4:H5 (one isolate) [26]. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1) is a 115-kDa protein toxin produced by uropathogenic and some other E. coli strains which have been designated necrotoxigenic E. coli (NTEC) strains [27–29]. In humans, CNF1-producing E. coli isolates have been implicated in extraintestinal infections, especially urinary tract disease and meningitis. NTEC strains cause at least 80% of uncomplicated urinary tract infections and most nosocomial urinary tract infections [30]. A distinct set of virulence determinants distinguish these strains from commensal strains of E. coli found in the colon and feces; additional factors such as ibeA (invasion of brain endothelium) may be required to produce meningitis [31]. Strains belonging to a limited number of O serogroups possess P fimbriae, iron acquisition systems, toxins such as hemolysin (Hly) and CNF1, capsule formation, and serum resistance [32,33]. These factors presumably allow NTEC to evade host urinary tract and/or mammary gland defense mechanisms. In animals, cnf1-positive E. coli strains have been isolated from dogs with diarrhea and urinary tract infections [34,35], cats with urinary tract infections [36], piglets with diarrhea and edema disease [25], cattle with both extraintestinal infections and diarrhea [37,38], and healthy animals of the aforementioned species. The ferret may be a promising model for evaluations of the contribution of cnf1 and other genetic factors to E. coli-associated virulence.

In mastitis caused by hemolytic E. coli, the histopathologic findings vary in severity from case to case, but the basic pathology is similar [16]. The primary lesion is characterized by large areas of coagulative and liquefactive necrosis that involve the glandular tissue, as well as the adjacent adipose tissue and muscle. Extensive congestion and edema, with focal areas of hemorrhage, are in the intralobular and perilobular tissue, as well as the adjacent SQ tissues. A moderate leukocytic infiltrate, composed primarily of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, concentrates at the perimeter of the necrotic areas, and permeates lobules with minimal evidence of necrosis. Large numbers of bacteria are in the affected tissues. Thrombosis and necrosis of vessels within and immediately adjacent to areas of inflammation are common findings.

With S. aureus mastitis described in mink, the mammary glands are suppurative, with lactiferous ducts distended with purulent exudate, marked inflammatory edema of connective tissue, cellular debris, inflammatory cells, and desquamation of alveolar cells [19]. Cocci are readily observed in affected tissues. This condition can also be seen in ferrets.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and on isolation of the causative agent. When mastitis occurs in a colony, milk from affected glands of several jills should be submitted for culture and sensitivity to guide selection of appropriate antibiotics. Serotyping or phage typing of the organism may be helpful in establishing the source and spread of the organism in an affected colony of animals.

Treatment

Immediate and aggressive therapy is warranted if E. coli mastitis is to be successfully treated. Antibiotics, amoxicillin with clavulanate (Clavanox Drops, SmithKline Beccham Animal Health, Exton, PA; 18.75 mg per jill BID), combined dosage of both drugs; equal to 0.3 mL of the oral suspension), can be used if the disease is recognized early. Also, chloramphenicol 50 mg/kg IM or SQ every 12 hours can be used. Gentamicin treatment should not be used because of renal toxicity and/or ototoxicity, particularly if ferrets are dehydrated. Antibiotic therapy combined with wide surgical resection of the involved glands was formerly considered the most effective treatment of the disease. The affected glands and adjacent tissues are widely excised; the skin is closed over 1/4-in. Penrose drains with a simple interrupted pattern of nonabsorbable suture material. Protective bandages are applied to the surgical site. Our more recent experience shows that use of enrofloxacin (Baytril, Bayer Animal Health, Leverkusen, Germany) 5 mg/kg BID IM or per os (PO), in combination with flunixin meglumine, and early debridement and lesion care precludes the need for mastectomy. Broad-spectrum antibiotics injected SQ or IM are used to treat mastitis caused by gram-positive cocci. Flunixin meglumine (2.5 mg BID IM as required) or Carprofen (1–2 mg/kg orally once or twice daily) can be used an adjunct to antibiotic therapy to reduce inflammation. Supportive therapy is often needed as well. Palatable moistened food is provided as well as high-caloric food supplements.

If a single gland is affected, the jill may recover relatively quickly; however, the kits must be fed in the meantime, as the severe systemic illness greatly reduces milk production. Fostering the kits risks infecting the foster mother. When fostering is necessary because of severe systemic illness in the dam, wash the kits in antibacterial soap, treat them orally with the same antibiotic used in their dam, and keep them warm for an hour or two before placement with the foster mother. The foster mother may also be treated with antibiotic and should be checked several times daily for signs of mastitis. If the affected jill is still eating, her kits may be left with her, but are likely to require supplemental hand feeding. It is very difficult to hand feed neonatal kits if this is their sole source of nutrition, as they do not efficiently digest anything other than ferret milk [9]. However, supplementing them with puppy milk replacer will help sustain them rather than leaving them to depend entirely on a jill that is producing very little milk. When the kits are removed from a dam with mastitis, she is unlikely to sustain milk production, but if the kits are left with her, and she recovers within a few days, the constant stimulus of the kits trying to nurse maintains lactation, and the jill may be able to raise the litter normally when treatment has been successful.

Chronic Mastitis

Chronic mastitis is usually present but undetected in the jill before she whelps, or may not be apparent until the kits are approximately 3 weeks old, when the jill should be reaching the peak of her lactation. In affected jills, the growth rate of the litter slows and the kits become long and lean, growing in stature, but with very little body fat. Without human intervention, these kits will starve to death, as the jill becomes unable to meet their increasing need for milk. Chronic mastitis is usually caused by Staphylococcus species. It is an insidious disease, replacing the mammary tissue with nodules of scar tissue, greatly diminishing milk production. As a result, the kits make greater efforts to nurse and the teat ends become hyperemic and fibrous. This can initiate acute mastitis as the teat sphincter is damaged. The mammary glands appear full but will be firm instead of soft and pliable, and hard nodules will be palpable. Several glands are usually affected. It is tempting to move the litter of thin kits to a better-producing jill, but microbially induced chronic mastitis is very contagious. If kits are fostered from affected jills, eventually, the whole colony will be affected, and it will become very difficult to raise kits that reach their potential body weight at 6 weeks of age, even with supplemental feeding. Treatment with antimicrobials is not beneficial, as permanent damage has already occurred when chronic mastitis becomes detectable. The affected jills must be either be culled or isolated to protect the remainder of the colony. The infection is transmitted between jills housed next to each other either by direct contact through a nonsolid divider or by the hands of technicians caring for the litters, as well as by contact with kits from an infected dam's litter. If the jill is isolated, the kits may remain with the jill to keep warm, but they must be hand fed.

Pyometra

Pyometra in the ferret has many clinical and pathologic features similar to those documented in the dog and cat. It is uncommon in pet ferrets, given that most ferrets have been spayed at a young age before being sold as pets. However, stump pyometra may occur, particularly in ferrets with adrenal disease.

Epizootiology and Control

The disease is often documented in breeding colonies of ferrets or colonies in which ferrets are used for biomedical research [39–41], and is also recognized in nonneutered pet ferrets [42]. Pyometra was undoubtedly more prevalent prior to the recognition that prolonged estrus in the ferret produces aplastic anemia [3] (see discussion on aplastic anemia).

Clinical Signs and Pathology

It is important to ascertain whether the animal with pyometra is suffering from estrogen-induced bone marrow depression. Signs of hyperestrogenism include pancytopenia, enlarged vulva, purpuric hemorrhages, and melena. Animals with pyometra are depressed, lethargic, and sometimes febrile. Purulent discharge from the vagina may be present, and enlarged uterine horns may be diagnosed by abdominal palpation and radiography. Various microorganisms may be cultured from infected uteri, including E. coli, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., (including Streptococcus group C), and Corynebacterium spp. Affected enlarged uteri have the lumen filled with purulent exudate. Endometrial glands are dilated and cystic. Cells lining glands are desquamated, and lumens of glands are engorged with polymorphonuclear cells. The endometrial stroma also contains a mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate, often with focal abscess formation.

Diagnosis

Pyometra is diagnosed by clinical signs, determination of prolonged estrus, and demonstration of enlarged uterus. Purulent exudate caused by various microorganisms is often present within the vaginal canal. A neutrophilia may be present in cases of pyometra, uncomplicated by estrogen-induced aplastic anemia. In cases of pyometra with concurrent hyperestrogenism, however, pancytopenia may be observed. Pyometra can also be associated with adrenal disease and elevated sex steroids. Removal of the diseased adrenal glands is recommended, along with surgical removal of the uterus or uterine stump [8].

Treatment

If hyperestrogenism is diagnosed, conservative treatment for the hyperestrogenism should be initiated, along with antibiotic therapy to treat the pyometra. Once the animal has cycled out of estrus after hCG treatment, or by breeding, ovariohysterectomy is indicated. Blood transfusions and intensive supportive care may be required if the animal is pancytopenic [1,43].

Eclampsia

Eclampsia (pregnancy toxemia) occurs in some pregnant jills before whelping, and can kill unborn pups as well as the pregnant jill [44]. Pregnancy toxemia may develop during the last week of gestation in jills that either have very large litters (12 or more kits) or that are deprived of food when they are carrying normal to large litters. It is a disease caused by negative energy balance [45]. In jills with large litters, the uterus takes up most of the room in the jill's abdomen, requiring her to eat small amounts very frequently to maintain her caloric intake. If the diet is inadequate (i.e., too low in fat or protein or both), her intake will be inadequate and she will be in a negative energy balance. Jills on high-quality diets may also develop toxemia if something interferes with intake; for example, if the feed hopper is blocked and there is no other source of feed, or if drinking water becomes unavailable. Jills must be observed frequently to ensure that such accidents are quickly corrected. Two sources of drinking water should be available to the jill during mid to late pregnancy and during lactation. Most jills will drink more from a dish than from a water nipple or water bottle, but dishes may become contaminated or spill and must be cleaned and filled twice daily. During the last week of gestation, a moist diet provided in a bowl may be offered to the jill twice daily, ensuring that feed is available even if the feed hopper becomes blocked. The disease may be similar to the condition in guinea pigs, in which diet and stress may precipitate toxemia.

Clinical Signs

Affected jills become anorectic, lethargic and dehydrated, often have black tarry stools, and shed their coats profusely. If not treated aggressively, the toxemic jill and her litter will be lost. Serum glucose is initially low (usually below 50 mg/dL) but terminally may rise above normal to 150 or more. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is often over 100 mg/dL. Despite clinical dehydration, the hematocrit is usually below 30%; normal for a pregnant jill is over 40%.

Epidemiology and Control

Pregnancy toxemia is caused by a negative energy balance during the last week of gestation. This is a common condition in research jills acquired late in pregnancy, and in primiparous jills with litters of 10 or more. Any jill that is accidentally deprived of food during late gestation is susceptible. A sudden change to a different type or flavor of food may cause self-deprivation. A change to a less concentrated diet during the last week of gestation induces toxemia in most jills carrying more than seven kits. Even 24 hours of restricted intake will lead to toxemia.

Prevention of pregnancy toxemia is more rewarding than treatment. When pregnant jills are acquired by shipment from commercial sources close to term, sudden changes in the base diet must be avoided. Ferrets often will refuse to eat a new diet the first few times it is offered. Jills on dry diets will not eat if they are unable to drink enough water, and may have trouble using sipper tubes. A water dish should always be provided for a pregnant jill. Jills that are acquired early in gestation or are bred at the animal facility should be on a high-quality diet containing over 35% crude protein of animal origin, and at least 20% fat, primarily of animal origin. This dietary regimen will result in a high conception rate, as well as prevent toxemia and encourage maximum lactation.

Treatment

Treatment of pregnancy toxemia must begin immediately. Specific therapy depends on the stage of gestation. Cesarean delivery will often save the life of the jill, but the kits will not survive at less than 40 days gestation. A jill that becomes toxemic more than 24 hours before parturition must be nourished and rehydrated until delivery of viable kits. Administer electrolytes either intravenously (IV) or SQ, with glucose when necessary. Oral administration of high-protein, high-caloric supplements is indicated. Most ferrets will accept concentrated, malt-flavored cat nutritional supplements. Ferret-specific supplements are now available (see Chapter 11). These should be offered or force-fed at least four times daily. The jill requires at least 200 kcal a day for her own maintenance, and the requirements of the litter must also be supplied. If a change in diet induced toxemia, the ferret's original diet should be offered mixed with warm water to make a porridge, which increases palatability. Premium quality canned cat food may also be offered, but its high water content prevents this being a suitable single source of nutrition for pregnant jills. It is useful to improve palatability of the pelleted diet. Fresh food should be offered several times daily to maximize intake.

If a mildly toxemic jill is within 24 hours of her due date, she may be treated with prostaglandin and oxytoxin to induce parturition. In severely affected jills, a Cesarean section is indicated. Parental fluids and glucose hasten recovery and encourage lactation. Gas anesthetics such as isoflurane are ideal for sick jills, as fatty degeneration of the liver prevents rapid metabolism of injectable anesthetic agents. If toxemia is recognized early, most jills will survive the surgery but may not lactate, even when supplied with palatable, nutritious foods. Hand feeding kits under 1 week of age is very difficult. Fostering is the only realistic option for orphaned neonates [9]. Kits left with the jill after she has fully recovered from the anesthetic may be fed a supplement of puppy or kitten milk replacer administered six times daily by a fine-tipped pipette. This will keep them nourished for 24 hours, until it is clear whether the jill is lactating. Their presence in the nest and attempts to suckle will help induce proper lactation.

Recovering jills must be fed by hand for the first day and sometimes longer, until they are strong enough to look after themselves. Force-feed concentrated nutritional supplements hourly when the jill has recovered from anesthesia, and maintain hydration with IV or SQ electrolytes until she begins to eat and drink on her own. Good management will prevent pregnancy toxemia except for cases where the litter size is extremely large (e.g., 15 to 20 kits).

Pathology

The only characteristic lesion noted on postmortem is an excessively fatty, pale tan, or yellow liver (Fig. 15.8). There can be noticeable lack of body fat. Helicobacter mustelae-associated gastritis and/or ulcers can be seen and accounts for the melena seen clinically [46].

Vaginitis

Vaginitis, a result of irritation from foreign bodies, can occur, particularly in estrous females, because of mucous secretion and adherence of bedding material to the vulva.

Epizootiology and Control

The disease is sporadic but may occur frequently if estrous females are maintained on hay or straw, particularly if the bedding contains grass awns or seeds. It may also be seen in ferrets maintained on wood-based bedding. Streptococci and enteric organisms (e.g., hemolytic E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae) can establish a secondary bacterial infection. Control of the disease depends on removal of offending contact bedding from the ferret's enclosure, commencing 3 weeks pre-estrus and continuing until after mating. Alternate bedding could include shredded newspaper, cage board, or cloth or cotton matting.

Clinical Signs

Females have a yellow mucopurulent vulvar discharge. Physical examination often reveals the presence of foreign material (usually bedding) within the vagina. Streptococci or enteric bacteria are sometimes isolated on bacterial culture. Occasionally, ferrets also have a metritis and are febrile.

Nursing Sickness (Agalactia)

A condition known as nursing sickness occurs in dams before the fifth or sixth week of lactation. Affected females show signs at about the time of weaning, and sometimes after the kits are removed. Clinical signs include inappetence, weight loss, weakness, and incoordination [44,47]. Death follows an interval of coma. In some cases, the liver of affected jills is yellow, with a greasy texture. A hemolytic anemia may also be seen. Females should be watched closely for signs of emaciation and dehydration during lactation. The cause is unknown, but evidence on some ferret farms in New Zealand suggests that peroxidative stress associated with diets rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids predispose jills to this disease [48]. Another report noted that it is more common in jills during the first part of the breeding season, particularly when estrus was induced outside the normal breeding season [49]. Providing the kits with food and water at 2 weeks of age may preclude the onset of nursing sickness. Care must be exercised, however, to monitor supplemental food intake in the kits; overeating and an inability to digest food properly can result in diarrhea and rectal prolapse.

Milk Fever (Hypocalcemia)

This condition was reported in one commercial ferret farm in New Zealand [48]. It occurred in primiparous jills 3–4 weeks post parturition. Signs included posterior paresis, hyperesthesia, and convulsions. A rapid clinical response was achieved with an intraperitoneal injection of calcium borogluconate. The condition can be controlled by the use of a calcium supplement in the diet.

Pseudopregnancy

If implantation is not successful after mating, pseudopregnancy can develop. Pseudopregnancy can occur if there is an improper hormonal balance in the ferret caused by reduced light intensity 1 month before the initiation of breeding. It is important, therefore, to verify the light intensity of artificial lighting in breeding units or the light intensity during the spring on commercial farms. If breeding ferrets is continued in late summer, artificial light can extend the number of hours of light.

Pseudopregnancy can also result from using immature males younger than 6 months of age. It is advisable to ensure sperm viability in breeding males and to ensure that males have fully descended testes [50]. After mating, the vulval swelling recedes, the abdomen enlarges, and the jill will remain pseudopregnant for 41–43 days. The corpus luteum in the pseudopregnant ferret usually functions as long as those in pregnant animals. Nesting behavior and mammary enlargement will be variable. A lack of palpable fetuses establishes the diagnosis.

Cystic Urogenital Anomalies

Various urogenital anomalies have been described in other mammalian species and humans [51–57]. Clinically, most of these anomalies are found incidentally, whereas others may present clinically as distinct pathologic entities. The anomalies may be misdiagnosed as neoplastic [58–60]. Cystic urogenital anomalies on the dorsal aspect of the urinary bladder in ferrets have been described [61]. Prostatic cysts have also been reported in male ferrets with adrenal disease [62,63].

Epizootiology and Control

Many urogenital organs or ducts have distinctive histologic or ultrastructural morphology and express different proteins. The majority of these urogenital anomalies when finally detected are advanced and various secondary changes have occurred [58,59,64–71]. Based on the history, clinical presentation, cystograms, and pathologic findings, cystic urogenital anomalies can be seen in both sexes. The cystic structures are similar in terms of their anatomic location and/or histologic features [62,63].

Cystic structures in male ferrets are often suggestive of prostatic cysts. Several types of prostatic cysts have been described in other species, but their precise origin is unclear [54,72]. True prostatic cysts should be of epithelial origin and are often located within the prostate. The prostate gland in the ferret is a fusiform enlargement around the proximal urethra near the bladder neck and consists of tubuloalveolar glands surrounded by a fibromuscular capsule and divided by fibrovascular septa [65] (see Chapter 3). The glandular epithelial cells are cuboidal to columnar and have basal nuclei and intracytoplasmic periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive material. Prostatic cysts may be congenital or secondary to inflammation, hyperplasia, or neoplasia [54,72–74]. Estrogens and/or androgens have been suspected as predisposing factors for prostatic hyperplasia and neoplasia [73]. Periprostatic or paraprostatic are terms that often refer to various cystic anomalies around or adjacent to the prostate, including the prostatic cysts themselves and other glandular or ductal cysts [54,59,72,74]. Thus, the terms periprostatic cyst or paraprostatic cyst should be avoided when the nature and/or the origin of the cysts are unknown.

The location of the cysts on the dorsal aspects of the urinary bladder and/or proximal urethra in affected ferrets of both sexes suggests that the cysts might have originated from the mesonephric or paramesonephric duct remnant. Embryologically, the distal mesonephric duct that connects both the ureters and proximal mesonephric duct to the urogenital sinus, also known as trigone precursor, is resorbed into the dorsal wall of the urinary bladder, the trigone mucosa, and the proximal urethra in both males and females [51,55–57,75].

Adrenal cortical lesions are usually present in ferrets with cystic urogenital lesions. In mice, early gonadectomy results in adrenal cortical hyperplasia or tumors and other endocrine-associated lesions [76,77]. Ferrets with adrenal cortical and cystic lesions are often neutered, although their ages at neutering are not always known. It is common, however, for ferrets to be neutered at 4–6 weeks of age, prior to their shipment to pet stores. Normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic adrenal cortical cells produce both androgens and estrogens in humans and other animals [78–84]. In ferrets, hyperplastic or neoplastic cells of the adrenal cortex can produce estrogens and androgens, and high levels of serum estradiol have been reported with adrenal cortical neoplasia in ferrets [81,83,84]. Cystic enlargement of the prostate and prostatitis were also observed in some affected ferrets [81,83,84]. The hyperplastic or neoplastic adrenal cortical cells should be considered as a potential endogenous source of estrogen, androgen, or the related sex hormones in affected ferrets [61]. Sex hormones are known to affect the development of the urogenital system both prenatally and postnatally, especially the mesonephric duct and paramesonephric duct [85,86]. An axis of neutering-adrenal cortical neoplasia-estrogen/steroid hormone elevation could thus play a role in cyst development and/or growth under certain circumstances.

Clinical Signs

Ferrets present with dysuria and/or hematuria as well as tenesmus. Ferrets may also have alopecia and females may have vulvar swelling, both of which are compatible with an endocrinologic disorder. Males with cystic prostatic disease presenting with dysuria can have prostatomegaly resulting from elevated sex steroids, commonly seen in ferrets with adrenal disease [62,63]. On palpation, the cysts are interpreted as caudal abdominal masses, and are often suspected initially to be a tumor of the urinary bladder. Other clinical findings in six ferrets with cystic urogenital anomalies are summarized in Table 15.1 [61].

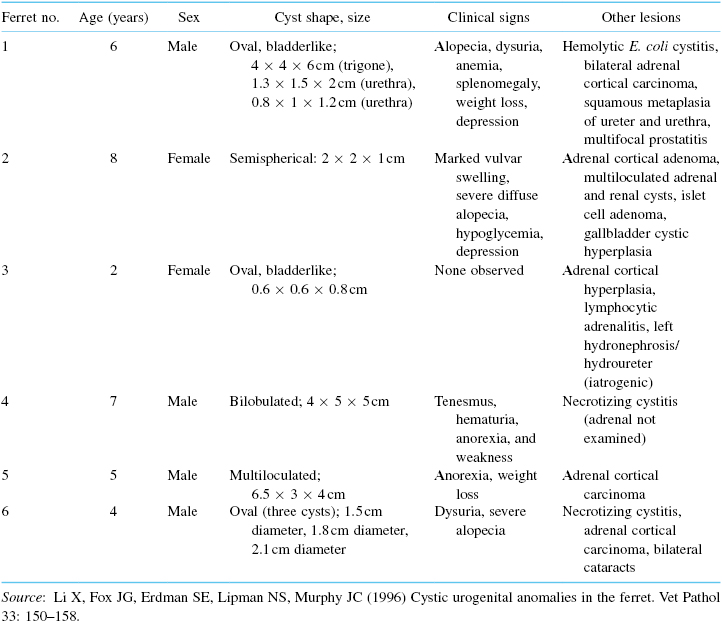

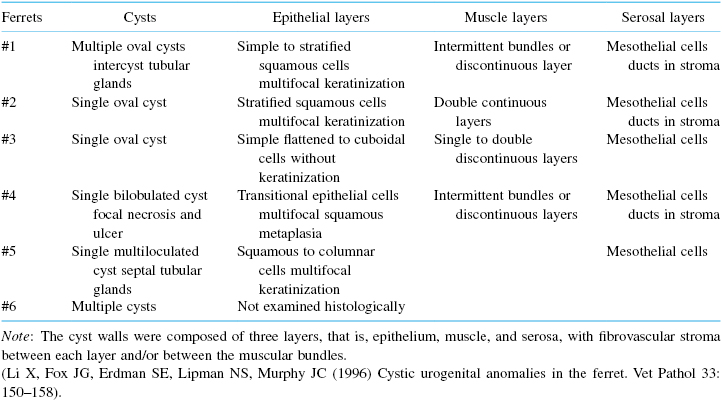

Table 15.1. Clinical Signs and Lesions in Six Neutered Ferrets with Cystic Urogenital Anomalies

Diagnosis and Pathology

A presumptive diagnosis is often made by digital palpitation of a posterior abdominal mass. Radiographically, the mass appears as a single or multiple masses dorsal to the bladder. Depending on the size of the cystic structures, they may displace the bladder ventrally. If urethral obstruction is present, it must be differentiated from urolithiasis caused by renal or cystic calculi. A cystocentesis and urine analysis will often assist in making a correct diagnosis. A diagnosis of accompanying adrenal disease is strongly supportive of urogenital cystic disease.

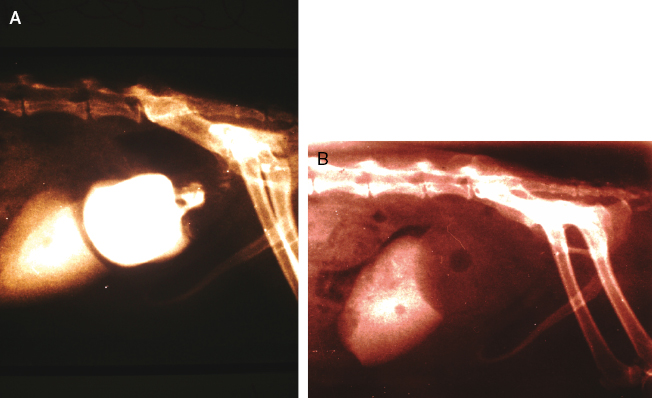

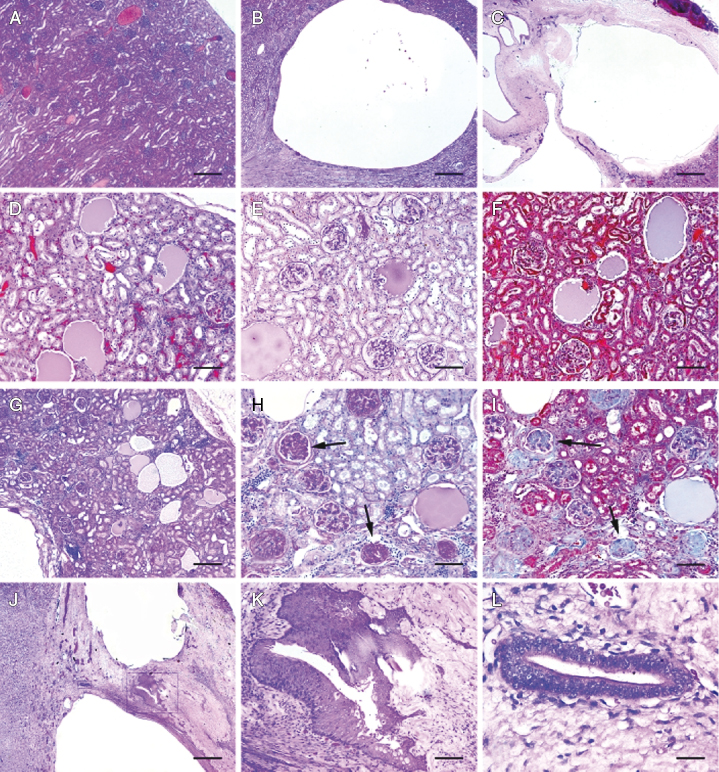

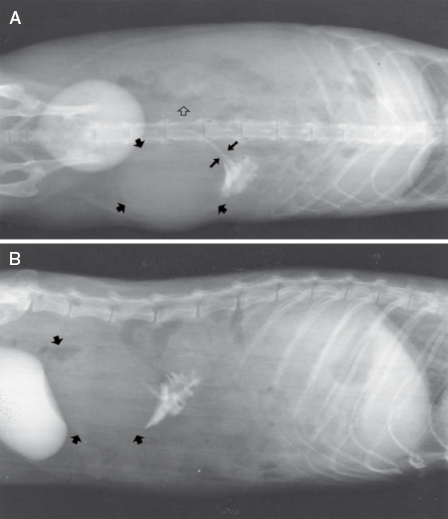

A cystogram may reveal that both the cyst and urinary bladder fill with contrast medium, but only the cyst retains the medium after bladder voiding (Fig. 15.9A,B). The cystogram may depict an image of a triple bladder, that is, both the bilobulated cyst and urinary bladder fill with the contrast medium.

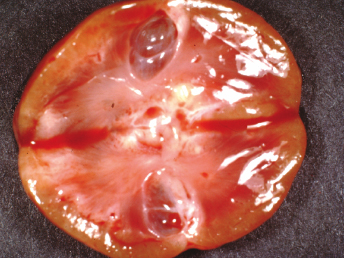

Macroscopically, affected ferrets have single or multiple semispherical to bilobulated fluctuant cystic structures of various sizes located on the dorsal aspects of the urinary bladder (Table 15.1; Fig. 15.10). The cysts are thin walled and smooth and contain clear to yellowish and odiferous urine-like fluid observed in five ferrets and white to yellow mucoid fluid. In some ferrets, the fluid contains debris, degenerating cells, and/or bacteria. The posterior aspect of the cysts are adjacent and/or attached to the trigone or neck of the bladder. Serosal adhesions to adjacent pelvic soft tissues may also be observed. The anterior aspect of the cysts project dorsally if small, or empty or dorsocranially if large or distended into the caudal abdominal cavity. Ferrets may have multiple or single cysts which can be bilobulated or multiloculated. A direct intraluminal connection between the cysts and urinary bladder or urethra is common.

Cranial cysts can be three times the size of the urinary bladder and extend dorsocranially 4 cm beyond the bladder apex (Fig. 15.11). Ultrasonography can also be performed to confirm the presence of cysts [8]. Cysts can be located on the dorsal aspect of the pelvic urethra and project into or from the dorsal prostatic parenchyma. Cysts attached to the trigone can resemble the urinary bladder, and may attach to the trigone, with intraluminal connection to the bladder. Alternatively the cyst can be located on the trigone and/or around the dorsal junction between the bladder neck and the urethra, with the long axis perpendicular to that of the bladder neck.

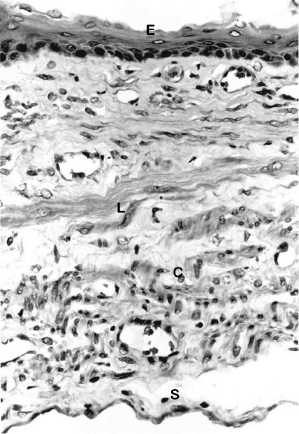

Histopathologically, the cyst walls are composed of three distinct layers, epithelium, muscle, and serosa, with fibrovascular stroma between the layers and/or between the muscular bundles (Table 15.1). The cysts can be lined with squamous epithelium with variable keratinization (Fig. 15.12), lined with a single layer of flattened to cuboidal epithelium without keratinization, or lined with transitional epithelium with multifocal squamous metaplasia. Occasionally, the multiloculated cyst is lined with cuboidal to columnar, keratinized or nonkeratinized squamous epithelial cells, in different chambers and even within a single chamber. The columnar epithelial cells may have basally located nuclei and contained PAS-positive material in the apical cytoplasm. Keratinization of the squamous epithelium is often associated with a fibrous cyst wall that is poorly vascularized, and the subjacent abutting stroma consists of dense collagen bundles. The muscle layer consists of intermittent bundles or single to double, discontinuous layers of smooth muscle in large or markedly distended cysts, or double continuous layers of smooth muscle in small or empty cysts.

Urethral cysts consist of fibrotic walls lined with stratified squamous epithelium, with abundant intraluminal keratin debris. Multifocal ulceration and necrosis with full-thickness infiltration of predominantly neutrophils, some lymphoid cells, and macrophages can be seen. Necrotic debris, bacteria, and degenerating cells are also noted is some cases [61].

Mild to moderate, focal to multifocal epithelial erosions, ulcerations, and infiltration of a mixed population of inflammatory cells can be observed in the urinary bladder mucosa.

Adrenal cortical cell hyperplasia or neoplasia is commonly observed in affected ferrets (Table 15.1) (see Chapters 17 and 24). The hyperplastic cortical cells resemble the normal cortical cells and present as nodules or in a more diffuse arrangement. The neoplastic cells consist of irregular cords, nests, or lobules, with fibrovascular stroma of variable abundance. The adrenal architecture is effaced to variable degrees. The cells are predominantly polyhedral and have round nuclei, single nucleoli, and eosinophilic to basophilic cytoplasm. Smaller and darker cells are also interspersed between the polyhedral cells.

Treatment

Initial treatment of urogenital cystic disease in ferrets should concentrate in relieving urethral obstruction, establishing hydration, and prescribing treatment for secondary urogenital bacterial infections. After confirming the presence of underlying adrenal disease, adrenalectomy is warranted. If the cystic disease is not advanced, atrophy of involved tissue may be sufficient to result in clinical remission of the disorder. With advanced cases, surgical intervention with drainage or removal of cystic structures is sometimes required (see Chapter 13). Given the common occurrence of secondary bacterial infection, bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing are routinely required in these cases, followed by aggressive antibiotic therapy as an adjunct to postoperative care.

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis has been encountered in ferrets maintained in our laboratory, and diagnosed at necropsy by others [87]. Infections of the kidney, in our experience, are associated with ascending urinary infections (with or without calculi) or septicemia. Hemolytic E. coli is often isolated from diseased kidneys and incriminated as the etiologic agent (Fig. 15.13). Other enterobacteria present in fecal flora can also cause infection of the urinary tract, similar to urinary tract infections in other species.

Diagnosis

The condition is diagnosed by the presence of blood, leukocytes, renal tubular or white blood cell casts, and bacteria in urine collected by sterile techniques. It must be differentiated from lower urinary tract infections, which is sometimes difficult. Acute onset may be noted clinically by anorexia, fever, and depression.

Treatment

Supportive fluid therapy is essential because the animals are often anorexic and have reduced fluid intake. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated to treat the infection. Use of parenteral trimethoprim–sulfa combinations (5 mg/kg once daily) and ampicillin or amoxicillin (10 mg/kg twice daily) to treat urinary tract infections, including pyelonephritis, is often successful. Treatment for 7–10 days is essential.

Cystic Renal Disease

Characterization of renal disease has been limited in ferrets in comparison to other domestic species. Renal cysts are frequent findings at necropsy or incidental findings during routine physical examination [88–90] (Fig. 15.14). Approximately 10–15% of ferrets had renal cysts in two separate studies [91,92]. In one survey, cystic kidneys were observed at necropsy in 5 of 50 animals. The cysts had a maximum diameter of 3 mm, and were located in the juxtamedullary region [91]. In another more recent study in 1994, 22 of 27 ferret cases studied were affected by some type of renal disorder including membranoproliferative glomerulonephropathy and cortical cysts [93]. There are two separate case reports of polycystic kidney disease in ferrets: In one case, a 3-year-old ferret presented with a history of multiple seizures over the preceding 12 months. Radiographically, the abdomen had a diffuse ground-glass appearance indicative of peritoneal effusion. The animal was euthanatized and necropsied. Fluid was present in the abdomen, and both kidneys were enlarged, with multiple cysts present in the cortex and medulla. Histologically, the kidney contained cystic spaces of various sizes lined with cuboidal epithelium. There was fibrosis of intervening renal tissue, with multifocal infiltration of lymphocytes. The relationship between seizures and renal disease could not be firmly established. The episodes of seizures may have been caused by uremic encephalopathy, but the brain was unavailable for examination. In another 3-year-old ferret with seizures, weakness, and ataxia, the ferret at necropsy had renal cysts [94,95].

We recently performed a 17-year, case-control, retrospective analysis of the medical records of 54 ferrets housed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) between 1987 and 2004, to determine the prevalence and morphotypes of cystic renal diseases in this species [96]. Histologic sections of kidneys were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, or PAS, and statistical analyses of hematologic and serum chemistry values were correlated with morphologic diagnosis. Of the 54 cases, 37 (69% prevalence) had documented renal cysts, and 14 of the 54 ferrets (26%) had primary polycystic disease consisting of either polycystic kidney disease affecting renal tubules or, more commonly, glomerulocystic kidney disease (Table 15.2). Kidneys later identified as having primary polycystic disease had a spectrum of gross lesions including cysts of various sizes (diameter, 1–25 mm; n = 6), pitted surface, wedge-shaped area of discoloration, foci of cortical pallor, and renal congestion.

Table 15.2. Histopathologic Findings in the Cystic Anomalies in the Ferrets

Primary polycystic diseases were subdivided into either polycystic kidney disease (PKD; tubular origin) or glomerulocystic kidney disease (GCKD). Because only one ferret met our criteria for PKD, this ferret was combined with the GCKD group to form a single, primary polycystic kidney disease cohort for statistical analysis. PKD was characterized by numerous large cysts of presumptive tubular origin associated with destruction of surrounding kidney structures and absence of evidence for an underlying renal disease in the remaining functional nephrons (Fig. 15.15). An important feature distinguishing primary GCKD from secondary glomerular cysts was the absence of basement membrane thickening or fibrosis of intact glomeruli.

Renal cysts were defined as secondary if they were clearly associated with a predisposing condition (Fig. 15.15). Kidney diseases predisposing to secondary cyst formation were heterogeneous in presentation, but they generally comprised one of two groups: developmental or chronic-end-stage kidney disease. Developmental nephropathies were usually segmental and defined by three histopathologic criteria: (1) cystic or microcystic dilatation of glomeruli, tubules, or both, (2) loose expansion of interstitial matrix associated with loss of preexisting glomeruli and tubules, and (3) thickening or splitting of glomerular and tubular basement membranes. This histologic presentation closely resembled canine familial nephropathies and polycystic kidney syndrome of New Zealand white rabbits, both presumed to be heritable conditions [97–99]. Cystic renal dysplasia displayed elements of developmental nephropathy, as well as retention of primitive, ciliated metanephric-type ducts (Fig. 15.15). Chronic renal failure with end-stage kidney disease was manifest by pitting of the renal capsule associated with segmental loss of underlying parenchyma, multifocal glomerular and tubular fibrosis with dilatation and atrophy, frequent protein and waxy tubular casts, and multifocal interstitial fibrosis. Cysts associated with end-stage kidney disease rarely exceeded 1 mm in diameter. The most common underlying lesion associated with end-stage kidney was membranous glomerulonephropathy characterized by basement membrane thickening and fibrosis of hypocellular glomerular corpuscles (Fig. 15.15).

Ferrets with primary polycystic lesions showed a trend toward lower hematocrit (34%), hypocalcemia (7.8 mg/dL), and hypoalbuminemia (2.2 g/dL) when compared with published normal values and all other groups. However, these differences failed to achieve statistical significance. Two serum chemistry values typically elevated in renal disease, BUN and phosphorus, were the only analytes that differed statistically (P < 0.05) between groups.

Secondary polycystic lesions were identified in 11 ferrets (20%), and 12 ferrets (22%) exhibited focal or isolated tubular cysts only as an incidental necropsy finding. Ferrets with secondary renal cysts associated with other developmental anomalies, mesangial glomerulopathy, or end-stage kidney disease had hyperphosphatemia and elevated BUN, in comparison with those with primary cystic disease, and elevated BUN compared with those without renal lesions (P < 0.05). Three ferrets with secondary cystic disease had clinical signs, clinical pathology, and histopathology findings highly suggestive of renal failure as a primary etiology. All three ferrets had decreased appetite and weight loss of 1–5 weeks duration; one presented with dehydration. Two of the three were anemic; all had azotemia and hyperphosphatemia.

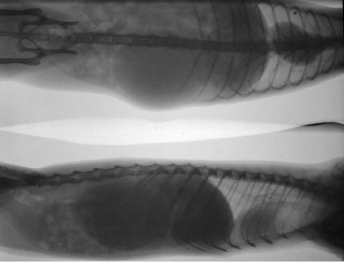

Although statistical significance was not achieved, all of the ferrets with cystic renal disorders had hypoalbuminemia, presumably the result of enhanced renal loss or inappetance. When compared with published normal values, hypoalbuminemia also existed in those ferrets without renal lesions. Importantly, this group controlled only the existence of renal lesions and not intercurrent, extrarenal conditions, or experimental use. In contrast to the difference in BUN concentrations, the difference in mean concentrations of creatinine between the secondary and primary cystic disease groups approached, but did not achieve, significance (P = 0.0502), presumably because of limitations in numbers available for statistical comparison. Alternatively, creatinine elevation during renal disease in ferrets may be more modest than that seen in other species, and elevations in BUN in the ferret may not be accompanied by increases in serum creatinine that are commensurate with those observed in other domestic animals [93,100]. For example, one ferret with secondary cystic disease in the MIT study population had a BUN concentration of 135 mg/dL and a creatinine concentration of 1.5 mg/dL. Creatinine concentrations in the ferret have a lower mean and narrower range than those in other carnivores, for example, the dog or cat [93]. This difference could be misleading to clinicians accustomed to normal creatinine concentrations over 1 mg/dL. Renal tubular excretion or enhanced enteric degradation of creatinine are potential mechanisms for its low normal concentration in the ferret. Despite the use of different reference laboratories for evaluation of the concentration of serum chemistry analytes, laboratory methodologies for all analytes except calcium were identical. Although reflecting institutional bias, these results implicate primary and secondary cystic renal diseases as highly prevalent and underreported in the domestic ferret. Diagnosis can be made with ultrasound and/or radiography (Fig. 15.16).

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis is occasionally reported in the ferret [101,102]. The ferret usually presents with progressive distention of the abdomen and no other clinical signs. Often, there is a recent history of ovariohysterectomy in a young female ferret. The most probable cause of the hydronephrosis is inadvertent ligation of the ureter. Radiography and/or ultrasound along with urinanalysis, clinical chemistry, and complete blood count (CBC) will help establish whether secondary bacterial infection of the urinary tract is present (Fig. 15.17). A unilateral nephrectomy is indicated and prognosis is favorable if the remaining kidney is functioning normally (Fig. 15.18).

Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Ferrets, like dogs and cats, can suffer from chronic interstitial nephritis. Older pet ferrets are susceptible to the disease. Clinical signs and prognosis are similar to those described for the dog and cat. Polydipsia, polyuria, and weight loss may be observed in advanced cases. Clinically, ferrets can also present with signs compatible with those of glomerulonephropathy; in some cases, this is caused by Aleutian disease (see Chapter 20).

Urolithiasis

Although ferret urinary disorders are infrequently encountered [103], there is an exception: urolithiasis may occur most commonly in pregnant jills fed a diet too low in meat protein or in those with ascending bladder infections secondary to retention of the placental membranes after whelping. The physiological processes involved with the jill's metabolism of minerals during late pregnancy makes nutritional urolithiasis most common in jills the week before their due date. This disease can be essentially eliminated in a colony by improving the diet, that is, feeding a diet high in meat protein and with minimal plant protein. The list of ingredients in a diet suitable for ferrets should not begin with ground yellow corn or any other plant material such as rice or wheat. The first ingredient should be chicken or other poultry, and for a breeding colony, it is ideal for the second ingredient also to be meat or fish. This can be achieved using either diets specifically formulated for ferrets or premium quality cat foods (see Chapter 6).

Diagnosis

The condition is diagnosed clinically by frequent urination, licking of the genital area, difficult urination, and occasionally complete urinary blockage in male ferrets. Urinary blockage can also occur in male ferrets with prostatic pathology associated with adrenal disease. Urethral calculi can be encountered secondary to bacterial infection. RBCs, leukocytes, and urinary crystals also are noted on urinalysis. When urolithiasis occurs in a pregnant jill, the calculi may be very large or there may be many small calculi. In either case, stranguria may be severe enough that the vagina is prolapsed. The jill may then mutilate the prolapsed tissue. The vulva and hair in the surrounding area will be damp, and calculi are readily palpable.

Treatment

Treatment is generally the same as that for cats suffering from feline urolithiasis syndrome. Patency of the urinary system is required to prevent electrolyte imbalance and uremia. Difficulty may be encountered, however, in catheterizing male ferrets because of the os penis. Sedation or anesthesia is routinely required, and urethrostomy may be necessary (see Chapter 11). Transcutaneous cystocentesis to relieve bladder distension can be used as a temporary measure. Antibiotics and urinary acidifiers may also be used. Renal function must be monitored closely. Salting of food may be used to increase fluid intake. Dietary management may also be similar to that used to treat the disease in cats—for example, reduction of the amount of ash in the diet. It is not known whether ferrets are susceptible to herpesvirus-induced urolithiasis, as suggested in cats [104].

Jills may also develop urolithiasis during lactation secondary to retention of placental membranes and endometritis, causing ascending cystitis. The organisms involved are usually staphylococci or E. coli. Prevention of ascending bladder infections includes palpation of jills post whelping to make sure all placentas have been expelled, and treatment with prostaglandin (0.1 mL IM) and antibiotics if placentas are still present. However, surgery to remove placental membranes is the most expedient therapy and prevents stranguria which, if severe enough, can cause a uterine prolapse. Potentiated sulfa drugs may be given on the day of surgery, but the bladder should be cultured to identify the antimicrobial most likely to be effective. Antimicrobial therapy should continue for at least 10 days. Most jills will continue to nurse their kits after surgery, but if the kits are 5 weeks old or more, weaning is advisable to prevent their chewing or clawing at the jill's sutures.

Urinary Calculi

Prevalence and Control

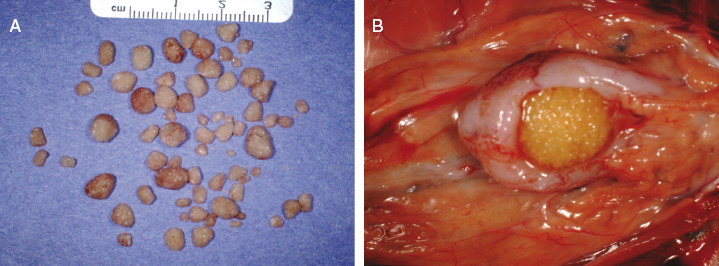

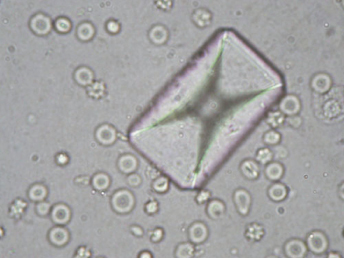

In one study, which reviewed 43 necropsies on ferrets dying from various causes, 6 of 43 (14%) of the animals were found to have urinary calculi [105]. Renal calculi up to 0.8 cm in diameter were found in three cases, and cystic calculi up to 1.5 cm in diameter were noted in four cases. The maintenance of these ferrets on dog food with a probable lower animal-based protein content then required for ferrets may have predisposed these ferrets to urolithasis [105]. Similar cases have been observed infrequently in ferrets maintained in our colony (Fig. 15.19). Two of the calculi were composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite), which is formed in alkaline urine and is often considered to be produced by urea-splitting bacteria [106] (Fig. 15.20). An outbreak of struvite urolithiasis was diagnosed in a colony of commercially reared, pregnant jills. A 5–10% incidence was recorded after the colony had been placed on a diet where protein in the diet was mainly in the form of ground yellow corn. The metabolism of the organic acids in plant protein promoted struvite crystallization because it produces alkaline urine (pH 6–7). Control of this disease was achieved in this colony by mixing several high-quality foods containing animal protein with the original diet. A rapid removal of the plant-based protein diet was not possible because a drastic change in diet may have precipitated pregnancy toxemia, particularly in those jills in late gestation. The jills' diets were supplemented with high caloric products that included amino acids or with milk that contained cream and egg yolk. A final fat concentration of 20% fat is optimum [107]. Urinary acidifiers are therefore recommended in treatment of these calculi as well as treatment of the underlying bacterial infection. In cats, however, dietary ingredients are increasingly cited as contributing significantly to urolithiasis and calculi formation. For ferrets maintained on commercial cat rations, it is conceivable that diets and mineral metabolism that predispose cats to urolithiasis may also have the same effect in ferrets [108]. Cystine bladder calculi are also reported [109–111].

In a recent published survey of uroliths in ferrets, 70 cases of cystine uroliths out of a total of 435 (16%) were diagnosed tabulated in the medical records of uroliths submitted to the Minnesota Urolith Center [111]. Controls consisted of 6426 ferrets without urinary tract disorders admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals during 1992–2009. Cystine uroliths were more common in males (54) than in female (16) ferrets. All the cystine uroliths were retrieved from the bladder or urethra, with the exception of three which were voided. Between January 2010 and September 2012, uroliths from an additional 69 ferrets were submitted for analysis (Table 15.3). Of these, 44 of 69 (64%) were cystine uroliths. In the later survey of 41 ferrets with cystine uroliths and known reproductive status, 36 of 41 (88%) were neutered males and 5 of 41 (12%) were neutered females. Although genetic predisposition to cystine stones has been documented in humans and dogs, genetic factors underlying the disease in ferrets has not been elucidated.

Table 15.3. Mineral Composition of 435 Ferret Uroliths Evaluated from 1992 to 2009 and 69 Ferret Uroliths Analyzed from 2010 to 2012

Source: Adapted from Nwaokorie, et al. (2013) Epidemiological evaluation of cystine urolithiasis in domestic ferrets (Mustela putorius furo): 70 cases (1992–2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc 242: 1099–1103.

| Mineral compositiona | No. (%) of uroliths (1992–2009) | No. (%) of uroliths (2010–2012) |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium ammonium phosphate 6 H20 (struvite) | 277 (64) | 12 (17) |

| Magnesium hydrogen phosphate trihydrate | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Cystine | 70 (16) | 44 (64) |

| Calcium oxalate monohydrate and dehydrates | 50 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Calcium phosphate | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Calcium carbonate | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Ammonium urate | 8 (1.8) | 3 (4) |

| Miscellaneous material | 6 (1.4) | 1 (<1) |

| Mixedb | 8 (<1.8) | 1 (<1) |

| Compoundc | 6 (<1.4) | 1 (<1) |

| Silica | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 4 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Total | 435 (100) | 69 (100) |

aAnalyzed by polarizing light microscopy or infrared spectroscopy.

bUroliths contained <70% of a single material component; no nucleus or shell detected.

cUroliths contained an identifiable nucleus and one or more surrounding layers of a different mineral type.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Clinical signs include dysuria, stranguria, and hematuria. Straining can sometimes lead to rectal and/or vaginal prolapse, particularly in pregnant jills with urinary calculi [107]. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, careful palpation and if necessary, radiology and ultrasound analysis. The type of calculi is determined by chemical analysis and demonstration in same cases of characteristic urinary crystals.

Treatment

With bladder calculi or urethral calculi (or crystals) in males causing obstruction, a cystotomy or perineal urethrostomy may be required. A cystotomy follows basic surgical techniques used for dogs and cats. During surgery, a careful search should be made for small calculi near or in the urethra, as these will cause severe stranguria during recovery from anesthetic, with possible tearing of abdominal sutures (see Chapter 13). The organism is usually Staphylococcus species or members of Enterobacteriaceae, but follow-up antibacterial therapy should be based on urine culture results. Oral trimethoprim sulfa combinations are often effective and may be administered until culture results are known. Pregnant jills requiring cystotomies heal well and are able to deliver their kits normally, even though surgery may have to be performed within a few days of the jill's due date.

It is important to note that in near-term (24 hours before delivery) pregnant jills with urinary calculi requiring cystotomy that a Cesarean section be performed prior to the cystotomy. This will prevent jills from dehiscing because of straining during parturition. Jills with adequate postoperative care nurse their kits normally [107]. However, a perineal urethrostomy in a male ferret must account for the os penis, which extends from near the tip of the penis caudal to the ventral rim of the pelvis (see Chapter 2). The urethrostomy should therefore be located between the pelvic urethra and the distal end of the os penis [112] (see Chapter 13).

Ectopic Ureter

An ectopic ureter has been diagnosed recently in a 6-month-old ferret. The ferret presented with urinary inconsistence and urine scalding of the perineal and inguinal area [113]. Excretory urography revealed a left ectopic ureter. A left nephroureterectomy was performed and an uneventful recovery was noted. Phenylpropanolamine administered to treat suspected urethral dysfunction improved the animal's incontinence; however, minor incontinence continued 3 months postoperatively [113]. Given that ectopic ureter is a common reported cause of congenital urinary incontinence in cats and dogs, it will be interesting to ascertain if additional cases of this congenital anomaly in ferrets will be reported in the literature.