In the years since the end of World War II, and especially since the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, no aggregate group has benefited more from the changes in American immigration law than have Asian Americans. Many, if not most, of the Latin Americans who came, it can be argued, would have come anyway, and Cold War mandates dictated the acceptance of Cuban refugees. Asian Americans also were beneficiaries of the general trend toward a more egalitarian society, at least in terms of race and ethnicity, that peaked in the mid-1960s. As we saw in chapter 11, shifting attitudes toward our Chinese ally during the war triggered the first positive change in the law in 1943. Two other factors helped bring about the changes. The belated admission of Hawaii to statehood in 1959 has meant the presence of Asian American senators and representatives providing political clout in Washington. In addition, the juxtaposition of these so-called model minorities with the perceived nonachievement of black internal migrants and most of the “Hispanic” population, hastened the increased acceptance of Asians, especially vis-à-vis other contemporary newcomers.

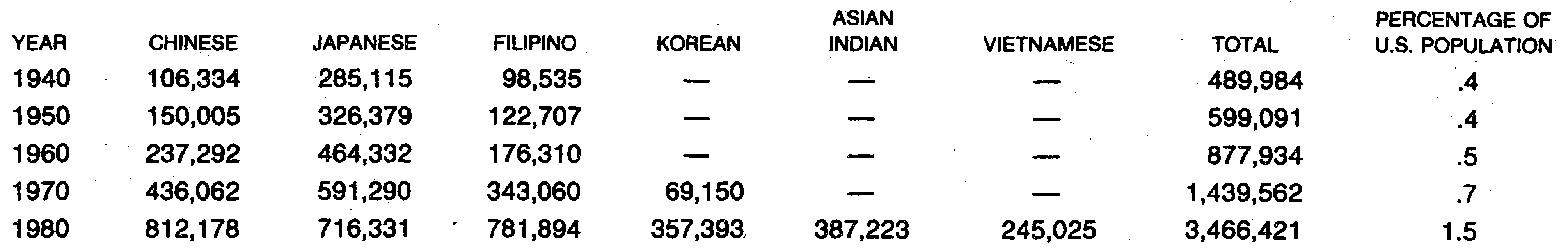

In demographic terms the growth of Asian American population has been startling. In 1940 Asian Americans were less than four-tenths of 1 percent of the American people: This incidence increased to half of 1 percent in the next twenty years. By 1980 Asians were 1.5 percent, and one responsible projection for the year 2000 has hypothesized Asian Americans as 4 percent of the population. This would represent a tenfold increase in incidence in sixty years. Table 14.1 ignores projections and shows Asian American population by major ethnic group at each census beginning in 1940.

If one looks only at the aggregate data, Asian Americans are younger than the average American. They also have fewer children, are less likely to be unemployed or in jail, and are more likely to get higher education than the average American. These and other characteristics have led to Asian Americans being called the model minority, a conception that takes certain middle-class norms as the ideal. But if one looks at the various ethnic groups, one sees all kinds of differences, both between and within groups. Taking the simplest and least value-laden category, we find the aging Japanese American population, which is overwhelmingly native born, with a median age of 33.5 years as opposed to a U.S. median of 30.0. Although recent immigrants tend to be much younger, Asian Indians are slightly above the national norm at 30.1. Other Asian groups range downward from Chinese at 29.6 to Vietnamese at 21.5. By comparison, black Americans have a median age of 24.9, while Hispanics were at 23.2. To understand these and other differences, it will be necessary to encapsulate briefly the history of each Asian ethnic group, something Harry H. L. Kitano and I have done at greater length in Asian Americans: Emerging Minorities (2001).1

Table 14.1

Asian American Population, by Major Ethnic Group, 1940–1980

NOTE: The data here include Hawaii, so they are not directly comparable to the data in tables 9.1 and 9.2.

There were a few thousand Koreans and Asian Indians in the United States prior to their appearance in the national census data in 1970 and 1980, respectively, going all the way back to the first decade of this century. There may have been 75,000 Asian Indians in 1970, most of them recent immigrants. There were only handfuls of Vietnamese before 1960. Other groups enumerated in 1980 included Laotians, 47,683; Thai, 45,279; Kampuchean, 16,044; Pakistani, 15,792; Indonesian, 9,618; Hmong, 5,204, and 26,757 others.

Japanese and Chinese

Sparked by a heavily female immigration in the years after 1952, Japanese American population growth, which had slowed perceptibly in the 1920s and 1930s—it actually declined in the latter decade in the contiguous United States—has been significantly more rapid than that of the United States, but much less steep than that of other Asian ethnic groups. Despite an annual quota of just 185 annually until 1965, some 45,000 Japanese immigrated to the United States between 1952 and 1960. About 40,000 of them (85.9 percent) were female and a majority of them were married to non-Japanese soldiers and former soldiers. After the early 1960s, immigration slowed. When the 1965 Immigration Act, which opened the door for so many Asian ethnic groups, was passed, few Japanese wished to emigrate. Had its provisions been on the books immediately after the war, undoubtedly emigration from war-devastated Japan would have been heavy. But, by 1965, as was also true for most Western Europeans, the economic motive to emigrate was no longer urgent for most Japanese. Japanese immigration slowed, absolutely and relatively, after 1960, and so did Japanese American population growth, most of which, in recent years, has been due to natural increase, the excess of births over deaths. The group’s population growth was 14 percent in the 1940s, 42 percent in the 1950s, 27 percent in the 1960s, and 21 percent in the 1970s. (Comparable figures for the whole population were, 14 percent, 18 percent, 13 percent, and 11 percent.) There is every reason to believe that the slowing of Japanese American growth will continue. Japanese were the largest Asian American ethnic group from 1910 to 1970, by 1980 they were third, and one projection for the year 2000 puts them sixth, after Filipinos, Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Asian Indians.

As we have seen, Japanese were, by 1980, an aging population, slightly older than the American population as a whole or than any of its major aggregates, and since they had had fewer children and a slightly higher life expectancy than the general population, that aging process will almost certainly continue. Japanese American population predictions are complicated by the increasing amount of out marriage, mostly with Caucasians, for the third and subsequent generations. Data for Los Angeles County show such marriages there at or above 50 percent of all marriages involving Japanese since the 1970s. Japanese Americans, in 1980, were more likely to finish high school and to go on to college than were white Americans, something that was true for most Asian American groups. Japanese American income was not as high as the group’s educational profile might suggest, but it was higher than that of most Americans. The median income of full-time Japanese American workers in 1979 was $16,829 as opposed to $15,572 for whites. But since so many Japanese Americans lived in the West (80 percent) where living costs are higher than average, the difference is even smaller than it seems. At the other end of the scale only 4.2 percent of Japanese American families lived in officially defined poverty, while 7 percent of white families did. The profile is very much of a largely middle- and lower-middle-class group, which is what Japanese Americans have become.

The Chinese American experience has been quite different. Population growth and immigration have increased in every decade. Population grew by 41 percent in the 1940s, 58 percent in the 1950s, 85 percent in the 1960s, and 86 percent in the 1970s; it is no longer possible to say exactly how many Chinese have immigrated in any one period, as Chinese come from many places: Taiwan, Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and China itself are the major sources. Many who came in under the Vietnamese refugee programs were, in fact, ethnic Chinese, and now identify themselves as such. A substantial proportion of the more-than-half-million increase in the Chinese American population between 1960 and 1980 represents immigrants, and they and their children represented an absolute majority of that population.

When compared to Japanese Americans, Chinese Americans are younger (median age 29.6 years), less concentrated in the West (52.7 percent), have a slightly lower median income per full-time worker ($15,753), and more than twice as high a percentage of families in poverty (10.5 percent). It is clear that the presence of large numbers of recent immigrants depresses the income figures and adds to the poverty percentage. The 1979 income data for full-time workers who migrated from Taiwan or Hong Kong show much lower incomes, with the amount being directly proportional to the time spent in the country. Those who came after 1975 had median incomes of $9,676 and a family poverty rate of 22.8 percent; those who came between 1970 and 1974 had incomes of $12,392 and a poverty rate of 6.2 percent, while those who came before 1970 had incomes of $13,692, and a poverty rate of only 2.8 percent. The seeming paradox that persons, such as pre-1970 immigrants, earn less money but have a lower poverty rate than do all Chinese Americans is easy to explain. First of all, immigrant households tend to be larger and contain more unrelated individuals and fewer old persons and thus more wage earners. Second, the median for all Chinese is raised by having large numbers of relatively affluent persons. Third, there are obviously large numbers of native-born American Chinese with low incomes who are in poverty in spite of their model minority status.

A further difference between Japanese Americans and Chinese Americans can be seen in the education data. Using the 1970 census, Chinese and Japanese Americans seemed to present a similar educational profile. Looking at those persons who were twenty-five and older, 68.1 percent of Chinese Americans were high school graduates as opposed to 68.8 percent of Japanese Americans; median years of schooling completed were all but identical, 12.4 for the former and 12.5 for the latter. This similarity in overall data masked great communal differences. More than a quarter of the Chinese adults had not gone beyond the seventh grade, and more than a quarter were college graduates. For Japanese Americans the comparable figures were about a tenth not going beyond the seventh grade and almost a sixth graduating from college.

This and other data clearly show the bifurcated nature of the Chinese American community, a community that, despite great achievement, still contains considerable poverty and deprivation. Dr. Ling-chi Wang, a San Francisco community activist and chair of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, testified before a U.S. Senate committee about the “silent” Chinese of San Francisco and presented data that showed conditions in San Francisco’s inner-city Chinatown that were anything but model. Unemployment was almost double the citywide average, two-thirds of the living quarters were substandard, and tuberculosis rates were six times the national average.

Although many Chinese Americans speak of two kinds of Chinese—the ABCs (American-born Chinese) and FOBs (fresh-off-the-boat recent immigrants, although almost all arrive by plane)—the immigrant/native born dichotomy does not explain all of the differences. There is, however, a greater tendency for recent immigrants to be poorly educated, deficient in English, and to work in the low-paid service trades, such as laundries, restaurants, and the sweatshop enterprises typical of the inner city. Conversely more and more of the ABCs tend to be college educated, have middle-class occupations, and live in integrated or relatively integrated housing outside the inner-city Chinatowns that, until recently, were home for the vast majority of Chinese. Manhattan’s Chinatown has become so crowded that satellite Chinatowns have developed in Queens, once the domain of white ethnics for whom Archie Bunker became the stereotype. To be sure, the dichotomy is not polar. Many immigrants are well-to-do, more than a few wealthy. The computer magnate An Wang was more than a billionaire, according to Forbes magazine’s list in 1983, and was reported to be the largest single contributor to philanthropic causes in Boston. The world-reknowned architect I. M. Pei was probably the most famous Chinese American immigrant.

American-born Chinese are also making important contributions to American culture, most notably in literature. Particularly important has been the work of two women, Maxine Hong Kingston (1940– ) and Jade Snow Wong (1922– ). The former’s magnificent first two novels—The Woman Warrior (1976) and China Men (1980)—although difficult, are must reading for anyone interested in the nature of Chinese life in America. The latter’s two memoirs—Fifth Chinese Daughter (1950) and No Chinese Stranger (1975)—are more accessible, and, when read together, can show the increase in confidence of Chinese Americans in the quarter century that separates them.

The projection, noted above, that Chinese Americans would drop behind Filipinos in number by the year 2000 was called into question by the traumatic events in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989. In the short run, at least, larger numbers of well-educated and well-to-do Chinese from Hong Kong are likely to emigrate than one would have expected initially, and some in Congress quickly moved to increase the number from Hong Kong eligible to come. Whether or not that happens, the Chinese American population can be expected to continue to grow significantly faster than the general population for the foreseeable future.

Filipinos

Three distinct increments of Filipinos have come to America. Shortly after the American annexation of the Philippines in 1898 came groups of students, with and without government support, some of whom stayed on and founded the Filipino American community. They settled chiefly in the Midwest and East. Then, in the 1920s and early 1930s, came farm workers who filled the same kinds of jobs in Far Western agriculture that Chinese and Japanese had pioneered. As American nationals, Filipinos could not be prevented from migrating to the United States although they, too, were aliens ineligible to citizenship until 1946. Most of these Filipinos were in Hawaii and California. In 1930 there were more than sixty thousand in the former, where they were 17 percent of the population, another thirty thousand in California, and perhaps fifteen thousand more in the rest of the United States. In California male Filipinos outnumbered females by fifteen to one. The current migration of Filipinos, coming largely after 1965, has been educated and consists of upwardly mobile professionals and would-be entrepreneurs, similar in occupational profile to many other recent Asian immigrant groups. Unlike most other “new” Asian immigrant groups, the majority of newcomers have been female. In 1960 just 37 percent of Filipino Americans were female; by 1980 nearly 52 percent were. No Filipinos have been in refugee programs, but a few elite Filipinos have been in political exile in the United States—most notably Corazon and Benigno Aquino and, after the Aquinos returned to the Philippines, Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos. The majority of each increment, like most Filipinos, have been Roman Catholics (hardly any Muslims from the Southern Philippines have come to America), but religion does not seem to play a major institutional role in the lives of most Filipino Americans.

The students were so few in number that they created hardly a ripple in the American consciousness. One scholar, Benicio T. Catapusan, a Filipino who earned a Ph.D. at the University of Southern California in 1940, estimated that between 1910 and 1938 some fourteen thousand Filipinos were enrolled in American schools. Most did not graduate, but many of those who did became leaders in government and business after returning to the Philippines. Many of those who did not finish stayed in the United States, usually plying the low-paying dead-end jobs that employed most Filipino Americans in those years. A number of Filipino intellectuals came to and lived in America. The most notable of them, the writer Carlos Bulosan (1911–56), wrote of the tension between the democratic ideals they learned about in the American-style school system in the Philippines and the harsh realities of American life. As Bulosan wrote to a friend:

Do you know what a Filipino feels in America? . . . He is the loneliest thing on earth. There is much to be appreciated . . . beauty, wealth, power, grandeur. But is he part of these luxuries? He looks, poor man, through the fingers of his eyes. He is enchained, damnably to his race, his heritage. He is betrayed, my friend.2

Like the Japanese before them, Filipino laborers first migrated to Hawaii, where the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–8 had cut off new supplies of Japanese labor. According to Mary Dorita Clifford, between 1909 and 1934 the Hawaiian Sugar Planter’s Association arranged for nearly 120,000 Filipinos to come to Hawaii: 86.6 percent were men, 7.5 percent women, and 5.9 percent children. On the expiration of their contracts, some went back to the Philippines, others stayed in Hawaii, and still others moved on to the West Coast of the United States. As Filipino population grew in California in the 1920s, an anti-Filipino movement flourished, fed by the same forces that had attacked Chinese and Japanese. By 1928 the national convention of the American Federation of Labor resolved that:

Whereas, there are a sufficient number of Filipinos ready and willing to come to the United States to create a race problem . . . we urge exclusion of the Filipino race.

Persistent discrimination, including a change in the antimiscegenation laws of California and three other Western states to include “members of the Malay race,” and a good deal of violence directed against Filipinos, made the anti-Filipino movement similar to the anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese movements which preceded it. One added theme was a persistent tendency to depict Filipinos as savages, a tendency that probably stemmed from the exhibitions of Igorot and other tribal peoples from the islands at American world’s fairs in the years following annexation. In fact, most immigrants were not “primitive” but modernized Filipinos who spoke two European languages, Spanish and English, as well as a Philippine language such as Tagalog, Visayan, or Ilocano. But one California judge, in 1930, declared from the bench that Filipinos were but ten years removed from savagery while another, after the depression had set in, gave his opinion:

It is a dreadful thing when these Filipinos, scarcely more than savages, come to San Francisco, work for practically nothing and obtain the society of white girls. Because the Filipinos work for nothing, decent white boys cannot get jobs.

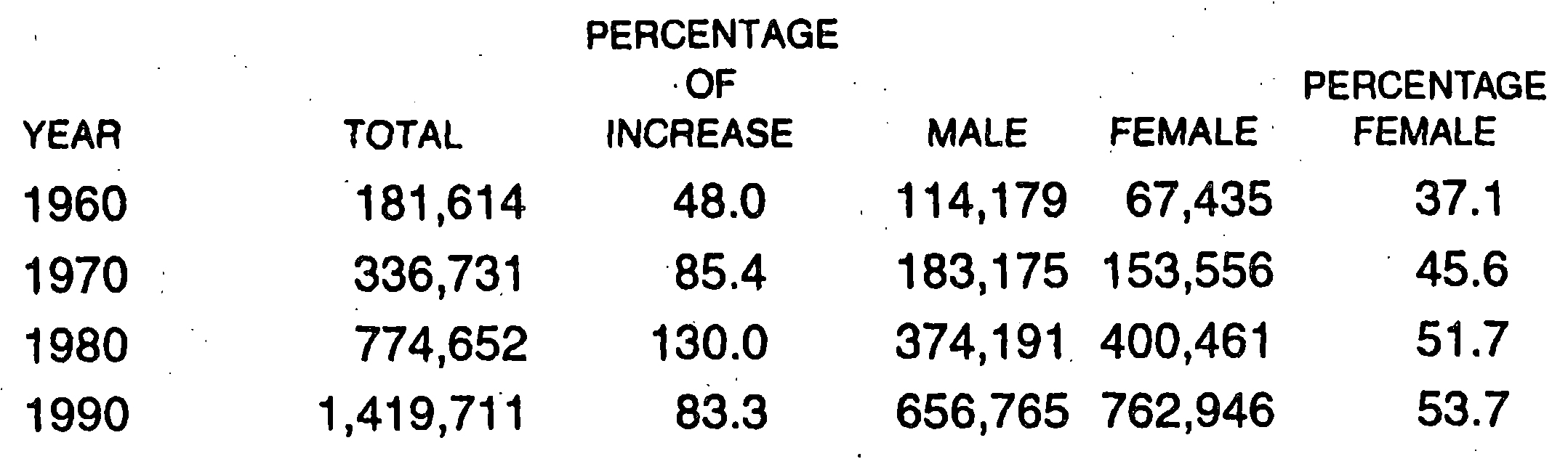

The special status of Filipinos as American nationals caused the political side of the anti-Filipino movement to become, at least superficially, anti-imperialist, since Filipinos could be excluded only if the Philippines were independent. In 1934 the Tydings-McDuffie Act promised the Philippines independence in 1945 and gave a quota of fifty persons per year, half of the previous minimum for any quota nation. Devout exclusionists, such as California’s senior senator, Hiram W. Johnson, had wanted total exclusion. Filipinos still remained “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Between 1934 and the end of World War II, Filipino population in the United States aged and dwindled, but the war years changed the image of the Filipinos to that of loyal allies against the Japanese while wartime prosperity in the United States somewhat improved their economic status. In 1946 Filipinos were made eligible for naturalization and the islands’ quota was doubled to one hundred annually. Although Filipino immigration was not large in the immediate postwar years, it was much larger than the quota would suggest. During the thirteen years of the McCarran-Walter Act, when there were a total of 1,300 quota spaces, the INS recorded 32,201 Filipino immigrants, most of them, obviously, nonquota immigrants. In 1963 for example, 3,618 Filipino immigrants were recorded. They were outnumbered by 13,860 “nonimmigrants”—tourists, businesspeople, students, and the like—many of whom were eventually able to change their status to immigrant. In addition, one category of Filipinos was given special status: Those who had served in the American armed forces—including the militialike Philippine Scouts—during World War II could become American citizens while still in the Philippines and thus enter the United States with their immediate family members. The United States Navy, which had traditionally recruited Filipinos as messmen and to perform other menial tasks, continued to do so even after the Philippines became independent. In 1970, for example, there were some 14,000 Filipinos serving in the American navy, more than in the Filipino navy. Thus, between 1950 and 1960, Filipino population in the United States increased 50 percent, most of it on the mainland. After the passage of the 1965 act, Filipino immigration increased sharply—in many years since 1965 Filipinos have been the largest or second largest nationality immigrating—and the population zoomed, as table 14.2 indicates.

The post-1965 migration, although it continued trends already manifested in Filipino immigration, was in many ways different from that which had gone before. The geographical distribution of Filipino shifted east and south. Whereas in 1950 about half of all Filipinos lived in Hawaii, in 1980 only about a sixth did. California had become the home of nearly 46 percent of Filipinos. Southern states, where previously few Filipinos had lived although a handful had been reported in Spanish New Orleans in the late eighteenth century, now contained about a tenth of Filipino Americans, as did the Midwest and Northeast.

Most, perhaps two-thirds, of recent Filipino immigrants have been professionals, most notably nurses and other medical personnel. During the 1970s, for example, the fifty nursing schools in the Philippines graduated about two thousand nurses annually. At least 20 percent of each year’s crop of graduates soon migrated to the United States, where shortages of trained nurses, especially those willing to work the long and uncomfortable hours demanded by public hospitals, provided instant employment. Many hospitals recruit nurses in the Philippines, and hospital administrators have testified that many of our urban medical treatment facilities could not continue to operate if all the foreign medical personnel were removed. Almost seven out of ten foreign-born Filipino women over sixteen were in the labor force in 1980, a higher proportion than that of any other Asian ethnic group. Nonmedical professionals, however, often are employed at jobs well below their skill levels, a phenomenon common among immigrant professionals generally, except at the very highest levels. (Albert Einstein and other Nobel Prize winners got appropriate academic employment even in the 1930s, but many well-qualified refugee academics of that era were never able to secure positions appropriate to their training and expertise.) Filipino lawyers may find work as clerks, teachers as office workers, dentists as dental technicians, and engineers as mechanics. However, they do find work, and the lower-status jobs in the United States often pay better than do higher-status jobs in the Philippines.

Table 14.2

Filipinos in the United States, 1960–1990

Assuming that the immigration laws do not change, there is no reason to expect that Filipino immigration will slacken, as economic instability in the Philippines seems endemic. And should political oppression again occur there, a number of refugees might seek to claim asylum privileges provided by the 1980 Refugee Act.

Asian Indians

Although some Asian Indians came to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all but a few thousand of the more than six hundred thousand Asian Indians in the United States at the end of the 1980s are post–World War II immigrants and their children, and the vast majority of these are persons who have come since 1965. The awkward term Asian Indian was adopted by the Census Bureau for the 1980 census at the urging of the immigrant community: This was to avoid confusion with Amerindians on the one hand and Pakistanis and Bangladeshis on the other. Previously the government—and the HEAEG—used the term East Indian.3

The early migrants, ten thousand or so, may be divided into two groups: poor laborers in the American West who comprised the bulk of the migrants, and several small elite groups distributed across the country. The former were almost all Sikhs; the latter were a cross section of India’s elite groups, including many Sikhs and a few Muslims.

The Sikhs, from the fertile Punjab, first came to the United States around the turn of the century from Western Canada and worked in lumber mills and on railroad gangs in the Pacific Northwest and California. In addition to the previously mentioned mob attack on them in Bellingham, Washington, they were persistently discriminated against: The polite, if inaccurate, term for them was Hindu or Hindoo, although they were commonly called “ragheads,” for the turbans their religion demanded they wear. Most who stayed, perhaps five thousand at most, found niches in two California localities: the Imperial Valley, near the Mexican border, and the northern Sacramento Valley, where the more successful of them became farmers.

There were three distinct groups of elite migrants: swamis, students, and merchants. The swamis, Hindu missionaries to America, began to come in the late nineteenth century. Historians of religion in America say that the most important of these was the Swami Vivekananda, who spoke at the World’s Parliment of Religions, part of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Vivekananda stayed for two years, founded the Vedanta Society, and returned in 1899, bringing two monks with him to preside over societies in New York and San Francisco. The second most important missionary was the Swami Yogananada who first came in 1920 to attend the Pilgrim Tercentenary Anniversary International Conference of Religious Liberals. He, too, stayed to found a religious organization, the Togoda Satsanaga Society in Los Angeles. Both groups emphasized the philosophy and practice of yoga, including posture and breath control. Both groups appealed mostly to middle- and upper-middle-class Protestants and had attracted some 35,000 adherents by the 1930s. The latter, which evolved into the Self Realization Fellowship, was the most extensive nonethnic “Hindu” organization in the United States until the appearance of the Hare Krishna movement in the 1960s.4

The early Indian students in the United States were largely rebels with at least emotional ties to the Indian Freedom movement. The natural place for Indians and other British colonials to study was at the seat of empire in England. Har Dayal, for example, resigned a fellowship at Oxford to come to the United States to do revolutionary work and, although he was primarily interested in freedom for India, had time to become an official of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Some students, mostly at Berkeley, where there may have been as many as thirty-seven in the World War I era, became part of the quixotic and fatal Gadar Movement.

Gadar, which may be translated as “revolution” or “mutiny,” was an attempt by Indian exiles in the United States to overthrow the Raj by sending revolutionaries and arms back to India. They were financed by the German government. The movement, betrayed by informers within its ranks, was nipped in the bud. No arms reached India: The revolutionaries who did were arrested, and some were killed. Since the unmasking of the conspiracy took place before the United States had entered the war, those who were caught (35 of 123 indicted were tried and convicted in a San Francisco court) were given only minor prison terms ranging from 30 days to 22 months for violating American neutrality laws. About half were Asian Indians: The others were Germans and Irish Americans.

Before this happened, the migration of poor Indians had been largely stopped by stringent application of the LPC clause. In 1917 the so-called “Barred Zone” act made the immigration of Indians impossible, although students, scholars, ministers of religion such as Yogananada, and merchants could come in and sometimes stay.

Among the small merchant elite, clustered on both coasts, the outstanding figure was Jagjit Singh who led the successful fight for Asian Indian citizenship discussed in chapter 13. The 1946 statute and other relaxations of immigration law and regulations before the passage of the 1965 act led to a regeneration of the existing Asian Indian communities. Fewer than seven thousand East Indians entered the United States as immigrants in the period 1948–65, almost all of them nonquota immigrants. But the individual who seems to have benefited the most from the change in the law was a man who had been here since 1920.

Dalip Singh Saund was born into a family headed by an illiterate but prosperous contractor just outside the Sikh holy city of Amritsar. Shocked by the massacre there in 1919 when—as shown in the film Gandhi—soldiers of the Indian army machine-gunned a nonresisting crowd that failed to disperse when ordered, Saund decided to leave India. Already possessed of a degree in mathematics, he continued his studies at Berkeley, earning three more degrees—an M.A. and a Ph.D. in mathematics, and, more practically, an M.S. in food processing.

Despite his qualifications—which he could have used had he returned to India—he concluded that “the only way that Indians in California could make a living” was to join with compatriots who were successful in farming. He settled in the Imperial Valley Sikh enclave, worked first as a foreman on an Indian-run cotton ranch, and then became a rancher and businessman. He acculturated with a vengeance—he had begun shaving and stopped wearing a turban shortly after emigrating—and in 1928 he married a woman from an upper-middle-class Czech American family. He and his wife, besides being successful and prosperous ranchers, became civic activists for a whole range of causes, including freedom for India and citizenship for Asian Indians in the United States.

Soon after he became a citizen Saund was elected to a judgeship, and in 1956 he was elected to Congress as a Democrat. He was the first Asian American elected to Congress and to this day the only one born in Asia.5 (The only other foreign-born Asian American congressperson, the one-term Republican senator from California, S. I. Hayakawa, was born in Canada.) Saund’s election was a mild if quickly forgotten sensation, and he was sent to India by the United States Information Agency to advertise ethnic democracy. Twice reelected, he was defeated in 1962 after a stroke confined him to a hospital bed.

The 1965 Immigration Act spurred a renewal of Indian immigration and has created a thriving and diverse community that has few obvious links, other than nationality, with the earlier settlers. Most are not Sikhs, few are in California or the West, and almost none of the newcomers are in agriculture. The recent population data are shown in table 14.3.

The vast majority have been well-educated and trained professionals who have quickly found comfortable employment niches in American society albeit, like most immigrants, they tend to be overqualified for the positions they hold. Many others have become entrepreneurs—sari shops and tandoori restaurants are the most visible enterprises—and they have found other idiosyncratic occupations. These include motel operation, with most of the operators sharing a common surname, Patel, and hailing from the state of Gujarat. Another set of entrepreneurs gained the contract to run and staff all the newspaper kiosks in the New York subways. What these operations have in common is a need for large numbers of low-paid employees, which is often filled by newly arrived relatives who enter as chain migrants. In the United States, Indian immigrants have not specialized in convenience food stores, as have Indians in London and Pakistanis in Copenhagen, but large numbers of newspaper kiosks in London have been owned and staffed by Indians.

The statistical profile presented by the available data from the 1980 census shows a reasonably well-off middle-class community. The median income of a full-time worker was $18,707—almost $2,000 higher than that of the next highest Asian American group, Japanese. But 7.4 percent of all Indian families were below the poverty level, as opposed to 4.2 percent of Japanese families. Characteristically, the more recent immigrants were less well off. Those who immigrated after 1975 earned much less—about $11,000 per full-time worker—and more than one post-1975 family in ten was in poverty.

Table 14.3

Asian Indians in the United States, 1970–1990

YEAR |

TOTAL |

PERCENTAGE OF INCREASE |

1970 (est.) |

75,000 |

— |

1980 |

387,223 |

416 |

1990 |

815,447 |

111 |

Asian Indian households were quite small, averaging 2.9 persons, as opposed to 3.4 for Koreans, 3.6 for Filipinos, and 4.4 for Vietnamese. The families that made those households were remarkably cohesive: 92.7 percent of all Asian Indian children under eighteen lived in a two-parent home, the highest for any Asian ethnic group. All of the other Asian groups, save Vietnamese, have figures in the eighteenth percentile, higher than the white American rate of 82.9 percent, and well above the Hispanic rate of 70.9 percent and the black rate of 45.4 percent.

Although many Indian women are well educated and have professional positions, they are less likely to be in the labor force than other Asian American women and have markedly less education than Asian Indian men. Whereas white, black, and Hispanic women were slightly more likely to be high school graduates than were men of the same groups, in all six of the most numerous Asian American groups the men were more likely to have diplomas. In some ethnic cohorts the difference was marginal (among Japanese Americans aged twenty-five–twenty-nine the gender gap was 0.1 percent); in many instances the differences were sizable. The widest gap revealed in the data published by the Population Reference Bureau was between Asian Indian men and women aged forty-five to fifty-four: 87.9 percent of the men but only 62 percent of the women had diplomas.

The data we have suggest a conservative middle-class community, but large numbers of that community have been here such a short time that it is dangerous to make other than tentative conclusions about it. Indian temples are probably proliferating more rapidly than Islamic mosques, though with less publicity and without the foreign subsidies that the latter enjoy, as Japanese Buddhist temples once did. In Cincinnati, for example, a community of some four hundred largely well-to-do middle-class families has pledged to raise seven hundred thousand dollars in three years to build a temple that will serve as a community center as well. Like most other Asian immigrants from the Third World to the United States, Indians represent a talent and capital drain from India, a talent and capital infusion for the United States.

Koreans

Almost all of the eight hundred thousand contemporary Korean Americans are either post–Korean War immigrants or their descendants. Early in this century a few thousand Koreans migrated to Hawaii and the American mainland: As late as 1930 there were fewer than nine thousand, with about three-quarters in Hawaii. After the Korean War, a significant number of Korean women came to the United States as war brides, almost all of them married to non-Asian-American servicemen. During the 1960s, for example, some 70 percent of all Korean immigrants were female, and women outnumber men significantly in almost every age cohort. The 1965 immigration law set off the same kinds of Korean immigration chains as have been commented upon for other groups. The figure for overall Korean American population are shown in table 14.4.6

One unique aspect of the early Korean immigrants is that most of them, traditionally Buddhist, were recent converts to Christianity, usually Protestant Christianity. The role of American—and to a lesser degree Canadian—missionaries in stimulating and facilitating this emigration is very important. After the occupation of Korea by Japan following the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) and total Japanese annexation, announced in 1910, the government in Tokyo made emigration very difficult. Some political refugees did manage to get to the United States where an exile movement was kept alive. Like the Asian Indians of Gadar, or various Irish American organizations harking back to the Fenian movement of the post–Civil War era, the Koreans were sometimes violent.

In 1908, Durham W. Stevens, a Caucasian American adviser to the Japanese administration in Korea, made a number of statements belittling Korean nationalism and supporting the Japanese takeover. He was assassinated in the lobby of San Francisco’s Palace Hotel by a Korean patriot, Chang In-hwan. The latter was convicted and sentenced to twenty-five years in prison. Released in 1919, he died in California in 1930. In 1975 his remains were flown to Seoul, and he was reinterred as a hero in the national cemetery.

The most significant of the Korean exiles was Syngman Rhee (1875–1965). A converted Christian who had been in prison from 1897 to 1904 for political activity in Korea, Rhee came to the United States to try to persuade President Theodore Roosevelt to protect Korea from the Japanese, as had been vaguely promised in an 1882 treaty between Korea and the United States. Roosevelt was not amenable to this; later he noted privately to his secretary of state that “We cannot possibly interfere for the Koreans against Japan. They couldn’t strike one blow in their own defense.”

Table 14.4

Koreans in the United States, 1970–1990

YEAR |

TOTAL |

PERCENTAGE OF INCREASE |

1970 |

69,150 |

— |

1980 |

354,593 |

417 |

1990 |

798,849 |

125 |

Rhee stayed in the United States, except for one brief visit to Korea in 1912 under the protective aegis of the YMCA, for the next four decades. He took three degrees from American universities, culminating in a 1910 Ph.D. in international relations from Princeton, and in 1919 was chosen by some Hawaiian exiles as the first (and only) president of the provisional government of Korea. After the end of World War II, Rhee returned to Korea with American occupation forces and became the first president of the Republic of Korea in 1948. He was forced into a second exile in 1960—again to the United States—where he died in 1965. Some other, less exalted exiles also returned after World War II, but most of the few thousand Koreans in Hawaii and California, who came as sojourners, had by then put down permanent roots.

Between the end of the war and the passage of the 1965 immigration act, four separate categories of Koreans came to the United States. Most numerous were the war brides married to servicemen, Peace Corps volunteers, and other American citizens. One count found more than twenty-eight thousand such persons before 1975. These, in Harry Kitano’s phrase, “assimilated before they acculturated” and often have little contact with the larger Korean American community, particularly those whose husbands are still in military service or who settle away from the major centers of Korean American population. A smaller group of Koreans have been orphans or other children adopted by American citizens, most of whom are not Koreans. One study found over six thousand such adoptions between 1955 and 1966: Almost 60 percent had non-Korean fathers, (46 percent white, 13 percent black). These Korean Americans tend to have even less contact with the Korean American community than do the brides. Of the thousands of Koreans who have come to the United States on student visas—there are perhaps five thousand here at present—some have not returned to Korea but have, in one way or another, been able to change their visas from student to immigrant or long-term visitor. And, finally, there were a few, after 1952, who came as regular quota immigrants—Korea had, as we have seen, an annual quota of 100—or as the relatives of American citizens. All these groups combined (including the old settlers and their children) certainly numbered fewer than twenty-five thousand when the 1965 law changed the rules of the game.

As the data in table 14.4 show, the Koreans have played the new game very well. The communal profile provided by the 1980 census figures shows the same kind of “model minority” performance as many other Asian groups. The Koreans were young (median age 26 years), well-educated (over 90 percent of males twenty-five-twenty-nine and forty-five-fifty-four were high school graduates), with full-time workers having a median income of $14,224, lower than that of Japanese or Chinese, higher than that of Filipinos or Vietnamese. Korean families seem quite stable: Almost 90 percent of all children under eighteen live in two-parent households. As is true for all Asian groups except the Indians, Koreans are concentrated in the American West (42.9 percent, 28.7 percent in California), but nearly a fifth lived in the Northeast, the South, and the Midwest. One conspicuous economic niche that Koreans have filled, particularly in New York City and Philadelphia, is that of operating small fruit-and-vegetable stores that stress high quality and personal service. Others have become professionals: Koreans are probably overrepresented on the faculties of American colleges and universities: More than a quarter of the employed native born and more than a fifth of the employed foreign born in 1980 were “managers, professionals, executives.” Among Asian Indians in the same census, 23 percent of the native born and a startling 47 percent of the foreign born, were in that category.

The most visible group of Koreans in America are the residents of the bustling Koreatown in Los Angeles, a vast and growing enclave just north of the central city, with Olympic Boulevard as its axis. Unlike the contemporary enclaves of Central Americans in Los Angeles, not to speak of the long-established Mexican American barrios or black neighborhoods such as Watts, Koreatown exudes an air of prosperity and growth, although it must be noted that the 1980 poverty rate for Korean American families—13.1 percent—was almost twice that of whites. In addition to innumerable business enterprises, the Los Angeles Korean community has, in a very few years, erected an impressive number of community institutions: newspapers, schools, churches—215 Korean Christian churches in Southern California by 1979 according to one count—and a number of cultural organizations including a Korean American Symphony orchestra.

Korean parents are much concerned with the education of their children. A celebrated example is the parents of the brilliant Korean American musician, Myung-Whun Chung, recently appointed conductor of the Opéra Bastille in Paris. Convinced that their children could get a better musical education in the United States, the family migrated for that reason. The results justify the move: The eldest child, violinist Kyung-Wha Chung was until recently better known than her brother; and, with a second sister, cellist Mung-Wha, the three have performed as a well-regarded piano trio.

Vietnamese

The Vietnamese are different from all the other major groups of recent immigrants from Asia. Rather than self-selecting immigrants reasonably well-qualified for success in America, Vietnamese, or many of them, have been poorly equipped for life in an urban society. To use the vocabulary of Ravenstein, they are mostly “push” rather than “pull” immigrants. Had they not been refugees—and refugees about whom the United States, with good reason, had a guilty conscience—most could not have qualified for admission.

Vietnamese have no long history of immigration to the United States: The few who left Asia usually went to France, including, for a time, the man known to history as Ho Chi Minh. Only after the United States took over from the French responsibility for resisting communism in Southeast Asia in the mid-1950s did a trickle of Vietnamese come here, chiefly as students. As American participation in Vietnam grew, so did Vietnamese migration to the United States, although as late as 1970 there were probably not even 10,000 Vietnamese in America and few of those had immigrant status. As the war went badly, more refugees began to arrive, and after the final debacle in 1975 the numbers became quite large. The 1980 census counted 245,000 Vietnamese, almost all of whom were post-1974 arrivals. In addition there were increasing numbers of Laotians and Kampucheans (Cambodians) who are also refugees from Southeast Asia and, essentially, from the Vietnam War and its aftermath. An estimate for 1985 put their numbers at 218,000 and 160,000 respectively. When smaller groups such as the Hmong, are added the total number of Vietnamese War refugees and their children in the United States by 1990 will exceed 1.25 million.7

The 1980 census data give an entirely different statistical profile for Vietnamese and other refugees from the Vietnam War than for other large Asian groups. They resemble not so much a model minority as the more traditional disadvantaged minority groups. They are very young (median age 21.5 years), not well-educated, and very poor. The median wage for a full time worker was $11,641 in 1979: more than a third of all Vietnamese families were below the poverty line, and more than a quarter of all Vietnamese families received some form of public assistance. Despite a determined attempt by the United States government to distribute Vietnamese evenly across the country, the 1980 census showed a clustering in the West (46.2 percent) and especially in California (34.8 percent). Within California the greatest area of concentration is Orange County, just south of Los Angeles, and the 1990 census will probably show an even greater concentration in those places. A federal refugee official in 1988 estimated that the percentage in California had risen to 39. Another reason some California officials give for the increased internal migration to California is the state’s more liberal welfare system. In California, for example, a family may receive welfare payments under the federal Aid to Families With Dependent Children program even though both parents live at home, but this is true in twenty-five other states and not true in Texas, where many Vietnamese live. Most of the rest of the Vietnamese were in the South, particularly along the Gulf Coast, where some fisherfolk were resettled and equipped with modern gear by the federal government. The conflict that this created between the newcomers and established fishermen has been sensitively treated in Louis Malle’s film, Alamo Bay (1985).

Those who have read the success stories that the press loves to run—the Vietnamese girl who wins the spelling bee—will wonder about the bleak statistics. Those statistics mask the fact that there is a very successful segment of the Vietnamese population here. One employed foreign-born Vietnamese in eight was a “manager, professional or executive.” Most of these, to be sure, were proprietors of small businesses, and most were from the more Europeanized sector of Vietnamese society. Former Air Vice Marshal Ky is representative of this group. Large numbers of high-ranking Vietnamese officials came here and to Canada, where a number are established in Montreal and other parts of Quebec, with significant amounts of capital. The same thing happened when the Nationalist Chinese government was driven from the mainland in 1949 and occurred in the late 1980s when many of the Nicaraguan contra leaders took up permanent residence in and around Miami.

But most Vietnamese refugees come with no significant amount of money, and many of the so-called boat people who continue to flee are stripped of what little they have by pirates and/or venal officials in the countries of first asylum. These are the persons who are now in poverty. Even poorer, as groups, are the Laotians, the Cambodians, and such premodern peoples as the Hmong. Few Laotians and Cambodians and no Hmong were really equipped to cope with modern urban society before they left Southeast Asia, and the transition has been quite painful and difficult. If the isolated success stories become more representative is something that only time can tell, but many of those most directly involved with these refugees fear that they, or most of them, will become a permanent part of that other America where poverty and deprivation are the rule rather than the exception.

Table 14.5

Southeast Asians in the United States, 1990

Vietnamese |

614,547 |

Laotians |

149,014 |

Cambodians |

147,411 |

Thai |

91,275 |

Hmong |

90,082 |