LIVING WITH CHINA: CANADA FINDS ITS WAY

Canada’s relationship with China was transformed in 2018–19 following a period of drift and China’s rejection in late 2017 of Canada’s progressive trade agenda for bilateral free trade negotiations. China-US tensions had been rising as a bipartisan consensus formed that China was no longer a partner to engage with, but an assertive adversary that does not play fair. Huawei Technologies became the public face of techno-nationalist complaints about the role of the state in Chinese business. Canada entered the spotlight as the United States requested the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s chief financial officer, under the terms of their bilateral extradition treaty. Canada’s legal obligations counted for little, however, in the eyes of China’s leaders, who were reportedly angered by this mistreatment of one of their elite. The Canada-China relationship plunged into a diplomatic deep freeze when Chinese authorities arrested two Canadians working in China, imposed a death sentence on a third charged with drug trafficking, blocked imports of canola, a grain that in 2017 accounted for 17 per cent of Canada’s exports, and restricted other agricultural imports as well.

These developments underlined for Canadians several realities of life with China. First, they are not like us. China has great power aspirations and historical grievances. It punishes countries, particularly smaller ones, whose governments displease it, as with the arrests in 2014 of Canadians Kevin and Julia Garratt, and with Norway for awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo in 2010. Second, Canada’s bilateral options with China are influenced by the state of the China-US relationship, as became apparent in the 2018 US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA, the renamed NAFTA), to which the United States added an article imposing conditions on free trade negotiations with planned economies, such as China’s, by any of the three signatories.1 Third, restoring the relationship with China is a priority. In short, Canada needs a China strategy. Taking a comprehensive approach to the relationship argues against the current exclusive focus on the “comprehensive” free trade agreement that the United States has taken off the table and that likely would have taken many years to negotiate even if it had been possible. In this chapter, I begin by defining the China-US strategic context. I then propose a pragmatic, multipronged strategy that includes trade, investment, security, and engagement – a strategy based on mutual respect, accommodation, and willingness to discuss and manage deep differences in Canadian and Chinese values and institutions.

THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT

Their relationship with the United States dominates the strategic context in both Canada and China, but in different ways. Where Canada and the United States have many similar institutions and policies and their economies are deeply integrated, China and the United States are deeply different. Each views itself as exceptional. Even their sense of time differs, as might be expected when one country is a relative newcomer and the other a civilization dating back thousands of years. Chinese think in centuries, Americans in the short term. Their governance and conduct of relationships differ: Confucian philosophy prioritizes order and harmony; institutions of governance emphasize hierarchies and obligations. Americans’ views, in contrast, are more transactional. Americans see their democratic capitalist system based on the rule of law, individual freedom, open markets and the separation of church and state as the best model for all countries. Views of government and the role of the state also differ. Americans tend to tolerate government as a necessity, but less is better; Chinese regard the state as essential to maintain harmony and order and to provide good governance.2

Both China and the United States have significant domestic economic and political challenges that are central policy priorities. Each is tackling these challenges, but in problematic ways that add to global uncertainty. In China the major economic reform agenda put forward at the Third Plenum in 2013 aimed to give the market a central role and produce a more sustainable, greener, services-oriented economy. The blueprint adopted at that time was subsequently superseded by other political priorities until 2018, when Xi Jinping’s address to the Boao Forum signalled a return to economic reform and a commitment to innovation-driven growth and further market opening.3 In contrast, since the 2016 election, the US administration’s domestic priorities have focused on improving employment in manufacturing and a simplistic preoccupation with reducing bilateral trade deficits. Informal accounts by Western visitors meeting with senior Chinese officials in the first half of 2018 reported considerable confusion about US strategic objectives as possibly symptomatic of the decline of the United States and of the Western order. Others voiced concerns about US zero-sum thinking, observing that the United States’ goal is to dominate – to isolate and contain China, promote internal divisions, and sabotage China’s leadership.

Looking back, as the United States moved in 1972 to normalize relations and in 1979 to establish diplomatic relations, the rationale was that, despite their different systems, engaging China as it reformed and opened up would generate greater benefits than costs. That calculus has now changed with the proliferating evidence of China’s ambition to pursue innovation-driven growth using technologies that might contain someone else’s intellectual property. China-US economic ties are fraying as the long-standing benefits of trade and investment are undermined by the costs to national security of such practices as China’s forced technology transfers and the targeting of US technology firms by SOEs for investment and the theft of intellectual property. In response the United States is now attempting to isolate China through such measures as the aforementioned USMCA article, increased CFIUS scrutiny of Chinese investors, and increased export restrictions on strategically important technologies.4 In short, Americans now believe Chinese are stealing their future, while Chinese believe Americans aim to contain China.

This zero-sum view dominated both the December 2017 release of the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy and Vice President Mike Pence’s hard-hitting speech in October 2018.5 These statements define China as a revisionist power seeking to challenge US influence, values, and interests.6 Mistrust of China as a strategic rival is expressed across the political spectrum. In February 2019 a report by the Asia Society’s Task Force on US-China Policy concluded that the two giants are on a collision course as the foundation of goodwill built up over many years erodes. As noted in Chapter 1, some dismiss such characterizations as stereotypical, maintaining that the real challenge comes from China’s peacefully confronting the United States on its own terms – from its bid for greater influence and economic advantage in East Asia, a region that the United States has taken for granted. The real challenge also comes from China’s promoting its own economic model while accepting global diversity, from pursuing its international interests within the existing order, but with governance reforms to increase its clout in the conduct of foreign policy.7

Standing back from the increasingly tense relationship, it is important to recall that zero-sum thinking is only one of several possible alternatives. As Graham Allison argues,8 accommodation is one possibility, based on a serious search for an adjusted relationship and a new balance of power without military confrontation. Another option is to negotiate a long peace, along the lines of the Cold War détente, recognizing the importance of domestic priorities to both countries’ leaders. A third option is to redefine the existing relationship of competition and cooperation to emphasize common global interests. For example, the United States could counter China’s version of a new great power relationship with its own version, such as one that promotes cooperation on four great common threats: nuclear war, nuclear anarchy, terrorism, and climate change. Only one of these options is hostile, based on a strong US critique of the contradictions in communist ideology and its interest in undermining the regime and fomenting domestic instability.

Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs commentator for the Financial Times, has emphasized the institutional advantages for Western nations that underpin the existing global order. He argues that the world is still “wired through the West” in its control of interbank financial telecommunications and stable and secure Internet operations,9 through the “wiring” provided by similar legal systems and common laws, and by the dollar as the world’s main reserve currency. Unfortunately Western power has also been used to China’s disadvantage. The long delay in reforming IMF governance to reflect China’s increasing economic size and influence is a prominent example. China has pushed back, creating such alternative international financial institutions as the BRICs bank and the AIIB.

Sinologist Susan Shirk has argued that the two governments must work out a new modus operandi based on current realities. By 2030 China will have the world’s largest economy; its total trade already outstrips that of the United States; and China is the de facto hub of the increasingly integrated economies of Asia, the world’s fastest-growing region. China must also face the fact of the Party’s fragile grip on power in the context of slowing growth and the risk of a financial crisis triggered by indebted SOEs and local governments. Shirk challenges China’s triumphalism at escaping the global financial crisis, amid evidence of stalling SOE reforms, rising discrimination against foreign firms, and the clampdown on non-governmental activities and academic exchanges. Instead of cooperative leadership, we have seen China impose its sovereignty on its neighbours through its maritime claims.

Shirk focuses on living with China as it is. She counsels the United States to maintain and honour its alliances, be prepared to push back against discriminatory Chinese actions and laws, and recognize that China is not a unitary state. She emphasizes the importance of regular intergovernmental communication, and counsels Americans not to stoke antagonisms but to stand firm on China’s advances in the South China Sea and insist on observance of international law. China, on the other hand, should address more effectively its ongoing discrimination against US investment by completing the long-delayed Bilateral Investment Treaty.

These expert insights and prescriptions are relevant to Canada’s deeper engagement with China. As a middle power, Canada’s choices for engagement are pragmatic ones with their own complexities. Given the depth of North American economic integration, evolving US perspectives of the China challenge will shape Canadian interests to some extent. Accommodation and cooperation with China is the preferred option. Under any scenario, Canada should emphasize the potential complementarities in the two countries’ bilateral trade and investment. David Mulroney, former Canadian ambassador to China, argues that Canadians can respect China yet reject its discriminatory policies and contest its differing institutions and values.10

As a February 2019 poll of Canadians by the University of British Columbia School of Public Policy and Global Affairs revealed, however, many Canadians are confident the relationship can be managed even as negativity towards China grows. The poll revealed an even larger decline in favourable views of the United States. Respondents identified expanding trade and investment as the top Canadian policy priority in the China relationship, with 64 per cent supporting a free trade agreement despite the decline in China’s public image. Sixty-five per cent of respondents thought the current disputes would be managed and relations would revert to normal.11

CANADA’S NEED FOR A CHINA STRATEGY AND A NARRATIVE

Relations, however, might not return to normal. Canada needs a China strategy, one that incorporates these elements and is realistic and forward looking. Reducing dependence on the US market by diversifying trade and investment currently ranks high among Canada’s national objectives. Yet it should be part of a more comprehensive strategy, one based on Canada’s interests and long-term economic and security objectives. These strategic elements include careful definition of Canada’s interests to be pursued in the China relationship, more emphasis in Canada on public learning about China, safeguarding Canada’s national security and participating more actively in Asia’s security order, widening and deepening bilateral economic engagement through trade and investment, and managing the long-term relationship with a more assertive China.12

Pursue Canada’s Interests and Long-Term Goals

Leadership at the highest official levels is essential to build the long-term relationships with Chinese and other Asian leaders, as is customary in the region, that will serve Canada’s interests. The two governments have pursued strategic links actively since 1970, when Canada recognized China’s Communist government. In 2005 leaders agreed on a strategic partnership. Other official agreements facilitate tourism, financial services, transportation, and science and technology, while Memoranda of Understanding exist on the environment and nuclear cooperation. In 2014 the two governments signed a Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA).

In 2016 the two leaders launched an Annual Dialogue between the Prime Minister of Canada and the Premier of China that began with each country’s leader visiting the other. When Premier Li Keqiang visited Ottawa on 23 September 2016, a number of agreements were signed encouraging new areas of cooperation and establishing working groups and a renminbi trading hub in Canada. They also agreed to launch an Economic and Financial Strategic Dialogue at the vice-premier level. Attempts to initiate negotiations on a free trade agreement, however, failed to bear fruit in 2017. Complementing these economic initiatives were others in science, health, and public safety. Later in September, Beijing convened the inaugural meeting of the Canada-China High-Level Dialogue on National Security and the Rule of Law, where discussions began on improving bilateral cooperation.

Promote Public Learning about China

One goal for Canadian leaders’ increased attention should be to deepen public knowledge about China and to address the reservations and concerns about China that have been voiced in recent opinion polls and in presentations to the Trudeau government’s extensive 2017 public consultations on negotiating a free trade agreement.13 Overall there is growing public support for a deeper economic relationship, but alarm about Chinese military activities and China’s growing presence in Canada. Polling revealed public anxiety about cyber espionage and other issues seen as potential threats to jobs and the Canadian way of life. In the government’s 2017 trade consultations, presenters called for engagement on human rights, cyber security, and regional security issues as expressions of Canadian values. They supported the emphasis on gender, environment, and labour standards in the progressive trade agenda – both as values and as differentiators between Canadians and their competitors in China.

The consultations attracted significant support from businesses and consumers in recognition of the substantial opportunities in the Chinese market and the realization that competitors in Australia and New Zealand are gaining strategic advantages, having already completed bilateral free trade agreements with China. Business presenters also called for greater predictability in China’s trade restrictions in order to reduce the transactions costs they face in the Chinese market. Commercial and other stakeholders expressed concerns about the rule of law, and questioned China’s willingness to adhere to its obligations negotiated in a comprehensive free trade agreement. Intellectual property protection was seen as improving, but the enforcement of rules as still problematic, suggesting the desirability of both a formal dispute settlement mechanism and mechanisms for dialogue. Concerns were also voiced about the complexities of doing business in a state-run economy populated by powerful SOEs.

These polls and consultations underline the need to address the outdated policy assumption that, as China develops and integrates into the world economy, it will become “more like us.” China will be itself. Canadians should adjust their expectations by learning about it and living with it as it evolves. China’s growing international presence and assertiveness with its Asian neighbours raises both hope and alarm. China insists it is pursuing what it defines as its core interests, but geopolitics clearly will be the central factor in the region’s future.

Find a Narrative

An important contribution to the process of learning about China will be a narrative for deeper engagement that attracts public support. The narrative should reflect at least three realities. First, there are fundamental differences in the two countries’ values and institutions. Deeper interaction will entail risks and frictions that must be recognized and managed. Editorials urge Canada’s leaders, as they deepen economic and security ties, to be realistic about whom they are dealing with and not to ignore fundamental differences, as Chinese officials do. Second, Canadians need to be clear about the potential implications for their country’s relationship with the United States as Canada diversifies its trade and deepens integration with what the United States now officially sees as a strategic rival. Third, although China might be a major US competitor and might wish to rewrite the rules, it has become a player in the larger objective of a peaceful and cooperative world order, to which Xi Jinping has emphasized his commitment.

A narrative for deeper engagement with China should therefore accept that China is different, but cooperation is possible and differences can be acknowledged and managed. Canada’s permanent reality is its location and deep integration with the US economy, but diversifying trade and foreign relationships serves Canada’s long-term interests. The Chinese market is a logical focus but should not become a new source of dependence.

Canadians could learn from Australia’s bilateral relationship with China, developed over four decades, aided by public leadership, education, learning about how to deal with a different governing system, advocacy, and exchanges of people. A key differentiating factor, of course, is that China is Australia’s largest neighbour and economic partner, not the United States, with which Canada’s economy is so deeply integrated.

Canada could also increase the opportunities for learning about China by expanding exchanges among members of civil society and by funding study programs for students, along the lines of the US-based “100 Thousand Strong” initiative to raise the number of students studying abroad. In Canada, Global Education for Canadians, published in November 2017 by the University of Ottawa and University of Toronto, provides a blueprint for similarly equipping Canadians to function in a globalized world.14 Such exchanges should be backed by the deeper connections between leaders suggested above.

Finally, care should be taken to recognize and integrate other key dimensions of the bilateral relationship, particularly in security, in recognition of the new realities of China-US geostrategic tensions and of China’s growing influence in the rest of the world.

Safeguard National Security and Participate in Asia’s Security Order

Security has two main dimensions: the safeguarding of Canada’s own national security, and Canada’s potential contribution to the nascent security order in the Asian region.

The implications for national security policy of a deeper Canada-China economic relationship are becoming more apparent as Chinese firms pursue mergers and acquisitions transactions in Canada. Cyber security and telecommunications infrastructure are two particular concerns. Canada and China have signed a cyber security agreement that prohibits state-to-state attacks, but two recent transactions in the telecommunications sector raise questions about the security implications of the acquisition of Canadian assets by Chinese enterprises. One transaction was the successful bid in 2017 for Norsat, a satellite communications supplier, by Chinese communications giant Hytera. This transaction was completed despite opposition from US lawmakers who argued against allowing a Canadian supplier to the US Defense Department to be acquired by a Chinese firm that is partly owned by the Chinese government and is an instrument of the Chinese state. The second transaction was the bid by SOE China Communications Construction Co. to acquire Aecon, a large, publicly listed Canadian construction firm, a transaction that the Canadian government blocked in 2018 on national security grounds. Since certain Aecon assets are part of the telecommunications infrastructure in both Canada and the United States, it was feared that transferring them to a Chinese-owned enterprise risked leakage of defence technology to the Chinese state.

Both Huawei Technologies, a privately owned company, and ZTE, its state-owned competitor, have been banned by Australia, New Zealand, and the United States from supplying equipment to 5G wireless networks. Canada is being pressed to do the same.15 Public safety minister Ralph Goodale initiated a government-wide evaluation of the security of supply chains, as have other members of the so-called Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance consisting of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Both Canada and the United Kingdom have agencies tasked with conducting security tests. In Canada the Communications Security Establishment has tested Huawei’s telecommunications equipment for such supply chain cyber threats as software vulnerabilities that can be exploited or pre-installed as malware in equipment or software. The UK government has permitted Huawei to undertake a limited range of activities, excluding it from supplying the 5G network “core” and government activities and subjecting it to continuous system monitoring.

As noted, Huawei in Canada has been caught up in the intensifying adversarial China-US relationship. The United States aims to exclude Chinese firms from US business, and is pressing Canada to do likewise. Canadian telecom firms BCE and Telus, however, depend heavily on Huawei equipment in their networks, and argue that a ban on such procurement would reduce their options – leaving only Nokia and Ericsson to choose from – and raise their costs. Their argument is that US demands are based primarily on US security arguments that ignore the economic issues, and they question the US case for the ban as protectionist and politically motivated. They argue that security concerns about Huawei’s 5G switching systems can be dealt with by requiring its compliance with national regulations, as Germany has reportedly done, and by limiting Huawei connections to core voice and data networks.16 Others disagree, sometimes vehemently, arguing, for example, that using Huawei equipment would be “giving the Chinese Communist Party the power to spy on our daily lives on Canadian soil.”17

Huawei also figures in growing concerns about cyber security and protection of intellectual property in a digital world. Huawei’s support for Canadian research in 5G wireless technology has attracted public scrutiny on the grounds that Canadian researchers who transfer intellectual property to Huawei as a quid pro quo for research funding are creating national security concerns. Critics assert that research institutions that receive such funding are likely to become dependent on a technology firm that could be required to transfer technologies used in national and Five Eyes networks to the Chinese state, thereby undermining the security of Western networks. Canadian universities claim they are actively managing intellectual property issues, noting that Canada’s lack of large, innovative firms of Huawei’s size leaves Canadian researchers few choices for participating in developing cutting-edge technology if they wish to remain in Canada, while not facilitating such research could harm Canada’s own long-term interests. Concerns should also be allayed by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s conclusion that Canada has a robust system to test for and prevent security breaches.18

These cases illustrate the importance of Canada’s ability to manage the relationships among security, international trade, and investment. They also raise questions about US strategy with respect to Huawei. If the goal is to destroy the company, rather than reform it, the US push to exclude China could have the opposite effect: China could double down on technological innovation and its entry into markets where the United States is relatively absent, creating through time two competing and technologically differentiated “blocs.” This is particularly possible in telecommunications, where Huawei is a world leader. Experienced voices, including those of Singapore’s Kishore Mahbubani and Geoff Mulgan of NESTA, the UK Innovation Foundation, are among those who argue that, since the rest of the world will adapt and make room for China, a more effective strategy would be to push for a multilateral governance framework that China would be interested in joining. Such an institution should address the need for internationally accepted boundaries for cyber warfare and multilateral rules of conduct.19

The second security dimension is regional security in Asia.20 Here Canada has a window of opportunity to play a constructive role as Asians search for the leadership and institutions needed to address the risks and tensions of China’s rising profile. Until recently, China regarded international institutions and norms created by Western countries in the post-war period as generally in accordance with its interests. China has been a responsible player in international efforts to address climate change and in responding to natural disasters and pandemics. It has complied with the treaties it has signed, and has been active in all of the Asia-Pacific regional institutions. It has signed a number of free trade agreements with its neighbours, and has initiated an APEC-led process that could lead to a Free Trade Area of the Asia and the Pacific.

China is not out to overturn the existing order. As President Xi has emphasized in his speeches at Davos and elsewhere since he chaired the 2016 Hangzhou G20 summit, we live in an increasingly interdependent world. But as he also made clear at the 19th Party Congress in 2017, China will be more assertive in influencing the rules of international institutions. In the past, China has been a participant in these institutions, but not a leader. Xi has extolled the virtues of Chinese socialist democracy, and has reacted to the inertia in global institutions by projecting China’s influence through its own institutions, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the New Development Bank, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

At the same time, the regional conversation is shifting from the design of individual institutions to questions about the structure of the regional security order and the leadership required. These questions are of particular interest to the region’s middle powers, including Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Anticipating increased China-US tensions, they are asking what adjustments are needed by the great powers to maximize accommodation, show restraint, and offer reassurance to others in the region. What are the right venues for working out the norms, rules, and practices of a new security order? Non-traditional security through cooperation on humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and search and rescue are priorities as well. Canadian civil society has the reputation, credibility, and domestic resources to be a leader in working with China and other countries on such matters as water management, climate change adaptation and mitigation, infectious disease prevention, and the management of geopolitical tensions, including in the Arctic.

Yet Canada’s recent record has been one of strategic silence – a spectator in these regional discussions even though the consequences of a direct military clash between the region’s great powers or a new China-US cold war would be devastating for global supply chains and for Canada’s commercial interests. Unless Canada is a multidimensional player, it will not be accepted as a participant in regional initiatives to dampen geopolitical rivalry or to set the region’s cooperative framework and rules. Even if Canada chooses a reactive approach, that should be articulated so that partners know what to expect.

Canadians believe their interests are best served by a rules-based order and open regional institutions, rather than by competing regional structures. Competing regionalisms could lead to exclusive blocs led by either the United States or China, and make sense to those who still think in narrow terms of strategic rivalry and balance of power. But such competition would miss a historic opportunity to generate collective benefits of deepening regional economic integration. Canada, working with others, should be prepared to prevent miscalculations and accidents or rivalry that could spill over into conflict. As a middle power, Canada’s past role was to bridge great power differences whenever possible, not to exacerbate them. Accommodation to find common ground requires judicious decisions in the search for ways to adjust rules and institutions to reflect the views and interests of Asia’s rising powers, and China.

Widen and Deepen Economic Engagement

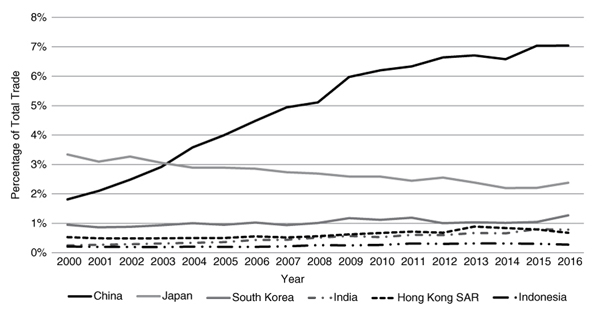

In contrast to its relative silence on security issues, Canada has been active in economic and commercial relationships with China and its Asian neighbours. China now accounts for 18 per cent of global nominal GDP and 40 per cent of Asia’s GDP (in terms of purchasing power parity). China is also now Canada’s second-largest national trading partner,21 accounting for 7 per cent of its total trade (Figure 6.1), 4 per cent of its exports, and nearly 12 per cent of imports – in contrast, the US market accounts for 65 per cent of Canada’s total trade and 75 per cent of its exports. Unlike Canada’s trade with the United States, however, with its intense competition and deep integration through supply chains, Canada’s trade with China is largely complementary and provides the basis for long-term collaboration.

Figure 6.1 Canada’s Total Trade with Selected Asian Economies, 2000–16

Sources: Merchandise trade data: adapted from Canada, “Trade Data Online,” available online at https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/scr/tdst/tdo/crtr.html?productType=NAICS&lang=eng, accessed 14 September 2018; service trade data: adapted from Statistics Canada, “International Transactions in Services, by Selected Countries, annual (x 1,000,000),” table 36-10-0007-01, available online at http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=3760036&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=-1&tabMode=dataTable&csid=, accessed 14 September 2018.

The potential benefits of building on these complementarities were recognized in the Canada-China Economic Complementarities Study,22 published in 2012. China relies on imports of food, energy, and natural resources; Canada’s comparative advantage lies in its rich natural endowments. China’s strategic industries include clean energy sources, conservation, and renewables, where Canadians are becoming innovators. The two governments have a chance to build upon these complementarities if they negotiate a trade-liberalizing agreement. Restrictions on free trade with China imposed by the USMCA do not have to be an inhibiting factor because in this case there are alternative – and more appropriate – approaches and agreements than comprehensive free trade.

Making the Chinese market a Canadian priority is desirable for at least three reasons. One is the uncertain future of the bilateral relationship with the United States under President Trump’s zero-sum, protectionist approach. Second, new competitors are lined up to supply China with food, energy, and natural resources; China’s free trade agreement with Australia, for example, grants concessional market access for Australian meat, wine, and seafood, which provides Australian competitors price advantages over Canadian suppliers. Third, the MIC 2025 strategy encourages import substitution to help Chinese enterprises move up global value chains in manufacturing and services. The implication is that Chinese producers in such industries as advanced rail transport equipment expect to do what Canadians already do well.

The list of sectors in which complementarities provide opportunities for collaboration is a long one.23 The energy sector could be a game changer for the bilateral relationship. China is the world’s largest net importer of petroleum and other liquid fuels, and seeks to tap Canada’s generous endowments of these products. In addition, with the priority accorded non-fossil fuels as China pursues a cleaner environment, Canadian firms can offer expertise and products ranging from hydroelectric and nuclear to uranium production to oil and natural gas. Canada also has expertise in energy conservation, renewables, clean tech, and managing the environmental effects of energy production. The challenge is to link this expertise to Asian supply chains.

Food security in China provides another complementary opportunity given Canada’s abundant food-supply capabilities. China is in transit from traditional to modern agriculture, while Canada has made large investments in innovation, technology, and practices to increase agricultural productivity. Pork is already a fast-growing export, as is cooperation on pig genetics.

The Belt and Road Initiative offers further opportunities for cooperation in infrastructure and transportation. Canadian firms have globally recognized expertise in land- and marine-based transportation technologies, in construction and construction machinery, and in building materials. China’s large air services industry and Canada’s record of exporting aerospace products and technical and management skills are another complementarity.

Beyond these sectors are other services industries, including tourism and education. The China Outbound Tourism Research Institute reports that by 2017 Chinese tourists were making 145 million cross-border trips annually. Canada is already an education destination as parents prepare their children for the highly competitive national tests in China and for possible futures in international businesses and organizations. Recent clampdowns on academic freedom can only add to the advantages of educating children abroad.

With the growth of China’s middle class, we can also expect rising demand for health care, environmental services, transportation, and financial services, all of which Canadians do well. Canada has a strong reputation for successful management of the effects of the global financial crisis and for the diverse investments by its large pension funds around the globe, including in China. As noted, Canada was also a first mover in establishing the first renminbi hub in the Western hemisphere to facilitate financial transactions between the US dollar and the Chinese currency in low-risk trade and investment.

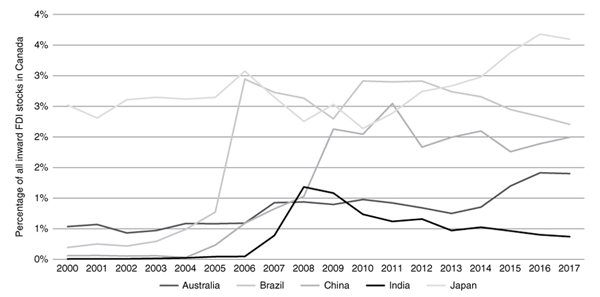

The other significant complementarity is in cross-border investments in productive assets. Major Canadian investors in large, well-established companies in China include Manulife, Sun Life, Bank of Montreal, Bombardier, and SNC-Lavalin, which have created Chinese affiliates over the years. More recently pension funds have acquired Chinese and other Asian assets in public and private equities and real estate. Even so, the stock of Canadian investment in China pales in comparison with investments in the United States – and in comparison with Chinese inflows to Canada. The latter have grown rapidly since 2008 (Figure 6.2) and have stimulated a policy debate that is discussed below.

Figure 6.2 FDI Stocks in Canada, by Investing Country, 2000–17

Source: Statistics Canada, “International Investment Position, Canadian Direct Investment Abroad and Foreign Direct Investment in Canada, by Country, Annual (× 1,000,000,” table 36-10-0008-01, available online at http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=3760051&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=-1&tabMode=dataTable&csid=, accessed 10 May 2019.

As a scene setter, a question can be asked about the potential fate of Canadian trade and investment in sectors where Canadians have developed new technologies, such as clean tech, energy conservation, transportation services, and agri-foods. What should be Canada’s strategy with respect to MIC 2025’s alleged emphasis on acquiring foreign technologies and forcing technology transfers? These threats might diminish in response to intense US pressure at the China-US trade talks in early 2019 to abandon such practices.

Negotiate Bilateral Investment and Trade Regimes with China

Investment: Although FDI inflows from China in recent years have included large numbers of small investments by privately owned Chinese enterprises – up to 2007 almost all investments were from large SOEs – industry players remain concerned about the steep learning curve Chinese investors face, even when their commercial objectives are similar to those of other investors. Differences in regulatory regimes and rules of the road are not fully appreciated or addressed.

In 2014 Canada and China agreed to a Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA). Initially hailed as a big step forward in ensuring investors in each country are treated as well as domestic investors, the FIPA also provides a comprehensive dispute resolution mechanism and protects foreign investors’ ability to repatriate capital and income. But weaknesses in the agreement have generated criticism. On the Canadian side, the Investment Canada Act imposes restrictions on Chinese investments above specified monetary thresholds. On the Chinese side, potential Canadian investors are not protected from discrimination in the pre-establishment phase of business development. China’s proposed new law on foreign investment would address such issues by introducing new standards, greater transparency, and a more open and predictable environment for investors.

Over the 2008–14 period, the small stock of Chinese FDI in Canada grew rapidly, and was the subject of an ongoing policy debate on three issues. Of these, ownership was the most contentious because of the predominance of Chinese SOEs and the concern that SOE investment decisions are based on political, rather than commercial, criteria. A second issue was reciprocal market access for Canadians in China, who do not have access comparable to that enjoyed by Chinese investors in Canada. A third issue was national security. SOEs are a source of particular concern. Since 2008 most prominent Chinese investments and acquisitions in Canada have been carried out by SOEs in the energy and mining sectors. Privately owned enterprises have invested mainly in minerals and coal, chemicals, solar power, and telecommunications equipment. But as we saw in Chapter 4, much merger and acquisitions activity is once again dominated by SOEs as China’s regulators move to reduce systemic risks in the financial system and strengthen SOEs by forcing their consolidation.

FDI has a number of benefits, not least because investments are long-term decisions requiring deeper engagement than cross-border trade. But there are also the risks of transferring control of strategic assets and technologies and of cyber espionage. Canada, the United States, and Australia screen inbound FDI and mergers and acquisitions to ensure such transactions do not pose a national security threat. The European Union is more open, although this is now changing in response to rising Chinese inflows and growing Chinese interest in acquiring advanced technologies.

Canada’s investment screening regime is risk oriented and ranked by the OECD as restrictive and more opaque relative to those of other OECD countries (but less so than China’s). A decision by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in December 2012 to restrict SOEs from owning controlling stakes in Canadian oil sands companies – except in (undefined) “exceptional circumstances” – added a third test to an already-opaque net benefits test and national security screen. Although the intent was to address the risk of (SOE) investors’ applying political, rather than market-based, criteria in their decisions, the policy change had a chilling effect on investment that disadvantaged the energy industry in a period of unusually low oil prices. Rather than influence SOEs’ behaviour, it risked sending a message to privately owned enterprises that they are not welcome in Canada.

Rationalizing Canada’s three investment screens into a single, more transparent national security test likely would tighten export controls over some technologies while reducing the transaction costs of the current uncertain approval process. Existing restrictions also discourage private equity players, who look to large companies for exit strategies from risky but innovative investments in small companies, and who in turn lack access to large players’ global supply chains.24

In summary, Canada’s investment screening regime should focus mainly on national security issues. It should be transparent and target investors’ behaviour, rather than ownership.

Trade: The public consultations in 2017 described earlier focused on negotiations on a bilateral free trade agreement. In 2015 Chinese officials had suggested a quick negotiation that might closely follow the China-Australia agreement signed in June that year. But standards for agreements have shifted since then, with Canada’s signing both the Comprehensive Trade and Economic Agreement (CETA) with the European Union in 2016 and the renamed Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017. Both agreements include services and investment, with more sophisticated coverage than the China-Australia deal – which itself is considered to be a “living” agreement requiring periodic upgrading.

When they met in September 2016, Canadian and Chinese leaders committed to regular high-level contact as the foundation for deeper economic and security relationships. They identified twenty-nine areas of agreement and cooperation, the fourth of which was “to launch exploratory discussions for a possible Canada-China Free Trade Agreement.”25 The 2014 FIPA is a useful precedent and a potential building block for any agreement. But a comprehensive free trade agreement is an ambitious goal: China has only a few such agreements with developed economies, and none was negotiated overnight. In decade-long negotiations with South Korea and Australia, major issues included differing regulatory, legal, and institutional factors and the scale of adjustment burdens that labour in less-competitive sectors likely would face. The South Korean negotiation was completed by temporarily setting aside investment in order to liberalize trade in goods and services in a timely fashion.

Canada’s interests would be served by moving forward promptly in recognition of increased competition in the Chinese market as the China-Australia agreement is phased in. With tariff removals agreed to on 95 per cent of goods exports, Australians expected the deal to add the equivalent of C$20 billion to bilateral trade in four years, particularly in agriculture, natural resources, energy, manufacturing, and services.26 Without comparable concessions, Canadians are at a disadvantage.

A bilateral negotiation will be neither easy nor straightforward because of the differences in economic systems and the range of trade and non-trade issues involved. Canada should be prepared for negotiations influenced by unique Chinese practices and concerns about Canadian policies. For example, Canadians are familiar with Chinese criticisms of their inability to find consensus among various interest groups around adding more pipeline capacity to transport Alberta’s oil and natural gas to world markets beyond the United States. Criticism can also be expected of Canada’s investment screening policies and the prohibition in 2012 of future acquisitions by SOEs of Canadian firms in the oil sands sector. Although the policy applies to all SOEs regardless of nationality, criticism of the opacity of Canada’s overall regime continues.

Trade Negotiating Options: In theory Canada has several options for structuring negotiations, but not all would accommodate the progressive trade agenda and its non-trade issues. This is likely true of the option suggested by Chinese officials who favour a largely goods-only agreement similar to the agreement with Australia. The second option, to seek a “high-standard” version of Canada’s negotiations in the CETA and TPP talks, would be a better fit. This route would be challenging for both parties to negotiate, however, as it would require detailed knowledge of each country’s institutions and policies. Either of these alternatives would also be an outright free trade agreement, and therefore subject to the conditions on free trade negotiations with planned economies imposed by the USMCA. A third option would be to embark on a phased, longer-term sectoral approach. This option would be time consuming, but it would give both sides needed opportunities to learn about the other, and it would avoid USMCA strictures.

The first option provides the clearest and simplest way to proceed, and, in the absence of the USMCA, likely would avoid most difficult regulatory and institutional issues. As in the 2015 China-Australia agreement, tariffs could be reduced in agriculture, natural resources, and manufacturing, trade in services could be facilitated, and barriers to Chinese private investment in Canada lowered.27 Australia committed to phase in tariff reduction beginning with 85 per cent removal, increasing to 95 per cent of goods exports upon full implementation of the agreement. China committed to eliminating tariffs on 10–25 per cent of such products as meat, wine, and seafood, and to improving Australian firms’ access to the Chinese market. But China also insisted on exclusions of products important to food security and the protection of wood and paper products. In addition China “paid” for continued protection of some other sensitive sectors by dropping demands for investment.28

The second approach would be similar to the first in that it would seek to eliminate Chinese tariffs and improve market access for Canada’s goods and services by applying the principle of national treatment. Canada’s goal presumably would be to achieve concessions similar to those agreed in the CETA and TPP negotiations.29 This would involve negotiating a “high-standard” agreement along the lines of the TPP, and would require extensive cooperation among officials in “Canada-China FTA committees” in which officials would engage on regulatory cooperation and problem solving during the negotiations and afterwards during implementation. CETA and TPP chapters could also be used as models in such sectors as sanitary and phytosanitary measures (CETA, Chapter 5; TPP, Chapter 14 for e-commerce and digital trade, Chapter 18 for intellectual property protection, and Chapter 16 for competition policy). Canada should also be prepared to deal with Chinese demands for a more transparent and less discriminatory investment screening regime and access to government procurement, and to accord China market economy status.

The third option would be a step-by-step approach resembling the Economic Partnership Agreements that are often used among East Asian nations. Unlike a free trade agreement, which aims to remove substantially all trade barriers, an Economic Partnership Agreement is less demanding, but is a flexible vehicle that facilitates ongoing liberalization and deeper economic cooperation. Such an agreement also allows for exceptions – as Canada experienced in negotiations with Japan, where agricultural sensitivities on both sides were potential roadblocks to a comprehensive approach. China is also familiar with Economic Partnership Agreements as a participant in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a major economic negotiation – mainly concerning goods – that is ongoing among the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and six countries with which ASEAN has free trade agreements.

Canadian and Chinese officials laid some significant groundwork for this kind of approach in the 2012 Complementarities Study, which selected seven sectors for analysis of trade patterns and existing trade and investment barriers, as well as for complementarities and opportunities for growth.30 In 2018 the Public Policy Forum further developed this approach with its proposal for a strategic framework for deepening bilateral integration in its report, Diversification not Dependence: A Made-in-Canada China Strategy.31

Such an approach, however, would take time to negotiate. In several sectors, both parties would face tariff and non-tariff barriers to various goods or services – for example, in the treatment of vegetable oils and seeds, in which Canada has an interest. In some sectors, the parties could cooperate around common interests, such as by removing intra-sectoral barriers; in other instances, removal of barriers would have to be addressed through inter-sectoral negotiations, where tradeoffs would be possible. This analytic approach would help to identify areas of common interest, where the mutual confidence necessary to conclude a more comprehensive arrangement could be developed with carefully sequenced cooperation in chosen sectors. Obviously the necessary mutual learning would be facilitated if the process began with a focus on sectors where bilateral cooperation is already under way. Clean tech and environmental goods and services would be an obvious candidate; agriculture and agri-food would be another, although tariffs would be an obstacle, as the following sectoral summaries illustrate.32

Sectoral Examples: Clean tech and environmental goods and services would be a leading candidate for an Economic Partnership Agreement approach given the two countries’ existing level of bilateral cooperation, the sector’s high importance to China, and Canada’s growing commitment to it. Beginning the formal process with a cooperative agreement in this sector could establish the mutual confidence and trust needed to deal with more difficult issues such as agriculture, where there are competing interests. In clean tech and environmental goods and services, both parties have demonstrated their interest in addressing domestic and global challenges. Trade in goods is small but growing fast. China imports clean tech goods from Canada – particularly parts and components for wind power generators and smart grids – while Canada imports solar cells. Cooperation takes the form of science and technology partnerships and initiatives to match Canadian capacity to Chinese needs.

Company size is a potential barrier to growth in this cooperation, in that Canadian companies are often small and medium-sized enterprises that operate on a small scale relative to the solutions Chinese customers seek. Intellectual property protection is an additional concern. Since 2016, however, clean tech has become a policy priority for both parties, with financial commitments to innovation, R&D, support for project finance, working capital, and equity investments, and assistance to commercialize clean technologies. In recognition of the relatively small size of many Canadian firms, a number of government departments have contributed to a Clean Growth Hub to provide one-stop services.

This high level of mutual interest implies the possibility of an agreement on environmental cooperation, perhaps as a side agreement similar to the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation in NAFTA in which both parties committed to enforce their own domestic laws. A council on environmental cooperation might also be created to foster partnerships between Canada’s clean tech firms and Chinese firms in the effort, among others, to facilitate inputs into the global supply chains of original equipment manufacturers’ international operations.

The agriculture and agri-food sector is also high on the list in the Complementarities Study, yet there are good reasons to discuss this sector later in the overall sequence of negotiations. Although there is ongoing cooperation in international forums, as well as bilateral mechanisms and agreements covering biotechnology, sustainable agriculture, and food safety, there are significant barriers to trade. Tariffs are still high in both countries (China’s are 15.6 per cent, Canada’s 11.3 per cent), and exceptions exist in certain product areas such as dairy, where Canada’s protection of its market prevents exports of any significance. Concessions made in the CETA and TPP negotiations would loosen this restrictive regime somewhat. Regulatory obstacles exist, with both sides identifying sanitary and phytosanitary measures and differing standards that raise uncertainties and trade costs. Negotiating tariff reductions and addressing product exceptions from negotiations, as Canada did with softwood lumber in the NAFTA negotiations – “paying” for the agreement’s dispute resolution compromise by opening energy to regional free trade – would be a high-stakes affair. Tradeoffs across sectors likely would be necessary, and therefore better dealt with as the negotiations mature.

Sequencing: These sectoral initiatives could be first steps in a sequenced or ‘living’ agreement that is renegotiated and modernized through time. Sequencing should be guided by a clear set of principles: that bargaining is consistent with the WTO and observes the principles of non-discrimination and national treatment. The goal should be to reduce and eventually eliminate barriers to trade in goods, services, and investment. Indeed a larger framework for the end game would be essential to allow the inevitable tradeoffs involved in inter-sectoral bargaining. For example, tariffs in one sector could be reduced by one of the parties in exchange for reductions by the other party in another sector.

In 2016 the two governments created a cooperative context when they agreed to double two-way visits and bilateral trade by 2025 and to improve the environment for cooperation in agriculture, energy, manufacturing, financial services, and infrastructure. Aviation, air transport, educational, and health care services were also included. To ensure the sequencing process is forward looking, talks might be structured to provide a platform for defining new rules if needed as new technologies emerge, such as those in biotechnology, robotics and digitalization, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. Further, if the agreement included a separate chapter on investment, as in the TPP, provisions for the settlement of investor-state disputes could be improved. Provisions should allow governments the right to regulate to achieve public policy objectives, while transparency standards should be required for documents filed with cases, and rosters of arbitrators should be subjected to strict standards to prevent conflicts of interest.

China would be a unique partner in such a negotiation. Rules for implementation would need to make explicit that neither party will impose ad hoc regulatory restrictions after negotiations are completed – as happened in the China-Australia agreement, where China reinterpreted some features when the deal took effect during a period of market price volatility. In the event that China failed to honour or reinterpreted its commitments, Canada should consider adopting special reciprocal measures to hold both parties accountable.

In summary, China will remain different even as its global economic and political prominence grows. Trade liberalization, which tends to dominate the debate about deeper economic integration, is now about much more than reducing tariffs and quotas on goods. With the proliferation of services trade and investment in global value chains, trade negotiations now include a number of formerly “behind the border” domestic policies, such as competition and investment policies, that call for ways to address regulatory differences and transparency and reduce administrative burdens of trade in China. More sensitive issues could also be addressed through cooperative discussions and the use of side letters to an Economic Partnership Agreement.

Addressing Non-trade Issues: Increasingly, political pressures are being brought to bear in trade negotiations to include non-trade issues and find ways to engage that bridge differences in values and institutions. The Canada-China negotiation is no exception, as the Trudeau government discovered in December 2017 when the Chinese leader showed no interest in its progressive trade agenda’s proposals for gender equality, environmental protection, and labour standards. Such agenda items do not fit readily into negotiations structured to deal with the usual trade issues of tariffs, quotas, and other trade restrictions. Instead alternative cooperative approaches have been developed, such as CETA’s policy dialogues, which provide channels to exchange information and find ways to cooperate on non-trade issues of common interest, such as peace and security, counterterrorism, human rights, migration, and sustainable development. Canadians have considered proposing a bilateral forum on human rights to highlight the importance of international obligations on human rights standards and to address specific concerns, such as China’s treatment of its Uighur minority.33 Other options include linking labour standards and environmental protection to the negotiations through separate Memoranda of Understanding or through dialogues intended to exchange views on current and potential policies and practices. Australia has long experience with alternative forums for such exchanges.

Manage the Relationship with an Increasingly Assertive China

China has punished Canada for acting under the terms of Canada’s bilateral extradition treaty with the United States and arresting Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. Meng’s case will wind its way through the Canadian judicial system; in its wake, Canadians will need to push patiently and persistently for normalizing the relationship with China.

Reactions have been mixed. The 2018/2019 Canada-China Business Survey of businesses in the respective countries reported that 20 per cent of respondents had been negatively affected by the dispute. Respondents from both countries had changed their business plans and cancelled investments.34 But not all Chinese are angry with Canada. Chinese consumers set new records during the 2019 spring festival in their demand for Canadian products – notably seafood, but also tourism. Chinese visa applications to Canada reportedly increased in 2018, with December being the second-busiest month in two years.35 A Canadian company reportedly has won a procurement contract with the AIIB, and others are bidding for contracts as well.36

As noted earlier, the Asia Society’s task Force on US-China Policy reports a changing US view of China towards one in which China observes the rules of world order when it is in its interest to do so. But, as the Task Force emphasizes, replacing engagement with an adversarial relationship is in no one’s interest. Some assert that Xi Jinping’s goal is global dominance; others argue that he is diversifying the available “portfolio” of international institutions and systems, thereby increasing his options.37 Those who argue his goal is global dominance point to China’s use of “sharp” power abroad through influence on the diaspora exerted by the United Front Work Department of the CCP.38 Evidence that China is moving beyond the exercise of soft power appears in reports of the purchase of political influence and support for political candidates in certain countries.39 Confucius Institutes, once welcomed, now face accusations of restraining or shaping countries’ national debates about China. In Australia, New Zealand, and at the United Nations, there are rising concerns about Chinese political pressures on politicians and participants in policy debates. Australia has passed sweeping national security legislation banning foreign interference and making it a crime to damage Australian economic relations with another country.40 In February 2019 the relationship reached a new level of pushback when the Australian government revoked a Chinese businessman’s residency and denied him citizenship as penalties for political activities and buying influence in Australia.41 Evidence of intimidation of Chinese students and of their reporting on one another has surfaced on US campuses as well. Creeping censorship threatens academic and journalistic freedom, with one university press facing blockage of online access in China to politically sensitive articles from a China-focused journal.42

This evidence of increasing assertiveness and opportunism underlines the significance of balancing engagement and accommodation with pushback by alliances among governments and coalitions among civil society and the media. The evidence suggests that China’s commitment to accommodation is conditional on its compatibility with the Party’s compact with the people. There are sceptics, however, such as former ambassador David Mulroney, who has called for “smart” engagement that reduces dependence on Chinese demand for Canada’s agricultural products and adds more value in Canada. He argues for greater selectivity in civil exchanges and tourism and for adopting a firmer stance towards sources of Chinese influence. Such measures are likely to attract criticism from Beijing and require determined responses.43

CONCLUSION

In early 2019 the future of Canada’s relationship with China is uncertain. In a complex policy environment, Canada needs a China strategy based on long-term economic and security objectives.

As the Chinese economy approaches parity in size with that of the United States, Xi Jinping has abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s “hide and bide” strategy for an assertive posture and messages that appear to challenge US pre-eminence and to support more state intervention in the economy. Calm voices in China counselling that the smart response to US pressures is to “double down on opening up” have little effect, even though such a strategy could avoid a costly and self-defeating trade war, and support China’s long-term growth objectives.

China’s mix of state intervention and market forces has caused tensions evident throughout the analysis in this book. Tensions among policymakers arise because of the increasing official intervention in “made-in-China” innovation, despite evidence that such top-down direction is likely to inhibit the risk-taking necessary to develop innovative ideas – and despite evidence that Chinese state-owned enterprises are less productive than their privately owned competitors. Tensions with the US government increased in early May 2019 when what appeared to be a trade deal broke down. Officials on both sides, under intense political pressures to be tough, reached an impasse. Chinese officials sought a deal between equals, while Americans, who now regard China as a strategic rival, were using tariff threats to press for changes in China’s economic system, something colonial powers had sought in the past. At the same time, China’s leaders had short-term concerns to modernize the financial system and improve the business environment, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises and for the private sector. Without such changes, China’s short-term prospects are mixed. The return of the state, politicization of markets, and increased repression have sent mixed messages to key sectors, reduced China’s long-term growth prospects, and might weaken the implicit social contract between the Party and the people.

Although China has penalized Canada harshly for participating in the US government’s moves against Huawei, Canada, like other trading partners of both the United States and China, stands to benefit from the liberalizing effect of the new Chinese law on FDI once the regulations have been issued. As Canada finds its way as a middle power, its long-term interests will be best served by a strategy that recognizes China-US geopolitical uncertainty, shifting power relationships, and China’s growing global prominence and assertiveness. Bilateral liberalization of trade and investment are key priorities, but the Huawei saga illustrates how national security has increased significantly in importance in this age of cyber security and digitalization. Multilateral pressures on China to adopt laws consistent with global standards are likely to be more effective than resorting to bilateral pressures to address differences in values and institutions. As long as Beijing refuses to engage in diplomatic exchange, its antagonism towards Canada in 2019 will prove difficult to manage in any but a step-by-step manner. Canada should also rely on international coalitions to press for normalization. All of these strategic elements will take time to develop and follow through; as other middle power partners have found, living with China requires focus, patience, and determination.