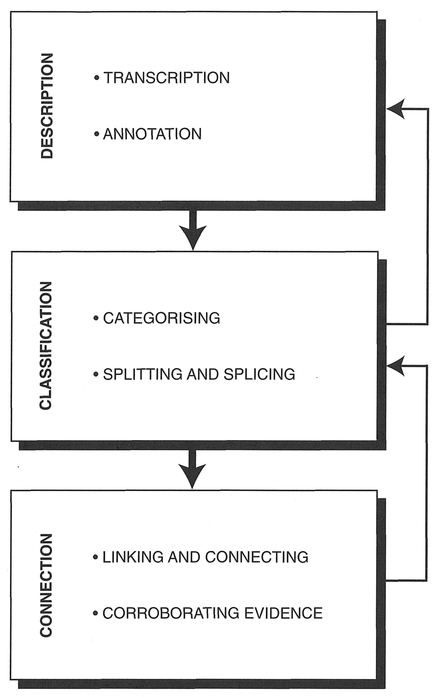

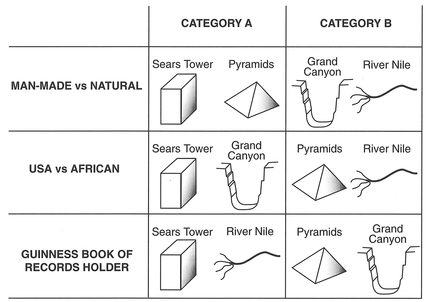

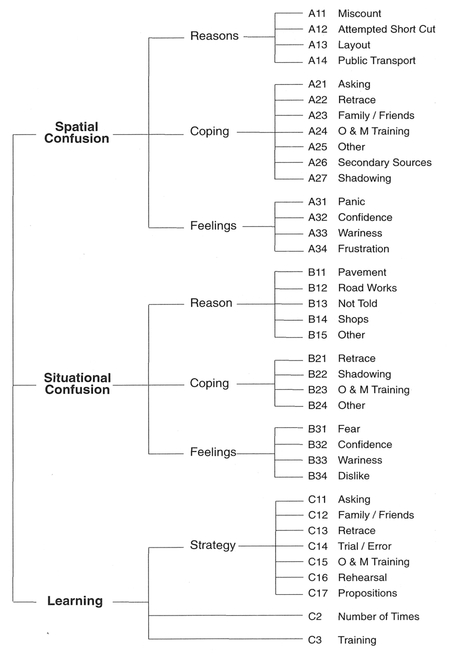

Figure 8.1 Description, classification and connection.

As detailed in the last chapter, there are different ways to approach the task of producing qualitative data. Similarly, there are different ways to approach the analysis of the data produced. For example, Patton (1990) uses an interpretative approach which emphasises the role of patterns, categories, and basic descriptive units; Strauss and Corbin ( 1990) use a 'grounded theory' approach which emphasises dif ferent strategies of coding data; Miles and Huberman (1992) use a quasi-statistical approach which seeks to minimise interpretative analysis and introduce an objective, prescriptive approach to analysis. As Silver man ( 1993) notes, these approaches are often utilised in analysing different sorts of data. When writing this chapter we had to make a decision as to how to proceed. There were two very different routes open to us. We could choose to discuss either methods to analyse interview, observational and secondary data separately (as with Cresswell, 1998), or a universal approach which can be applied to study all types of qualitative data. We have chosen the latter. As Dey (1993) argues, despite differences in emphasis, the various approaches to qualitative analysis all seek to make sense of the data produced through categorisation and connection. In our discussion of qualitative analysis we follow Dey's (1993) approach which seeks to combine different aspects of various other approaches to gain a deeper understanding of qualitative data. It must be appreciated that different commentators might, therefore, approach the data we present in a different manner and you are encouraged to read beyond our prescription. This is not to say that we have not drawn from alternative sources. Although the method of analysis we present follows Dey's prescription, we do incorporate the advice of other researchers.

Some researchers might be unhappy about following a prescriptive approach to qualitative data analysis. They would argue that the analysis of qualitative data is an art rather than something that can be undertaken through prescription (as with quantitative analysis, where you generally put in your data and get out a result). There is a degree of truth in this statement; qualitative data are not as rigidly defined as quantitative data and analysis lacks the formal rigour of standardised procedures. In an introductory text such as this, however, we feel that a prescriptive approach is the most appropriate. It provides you with a clear set of guidelines for analysing your data. Trying to practise qualitative data analysis as an art before you know how to draw is, in our view, a recipe for disaster. We therefore recommend that, until you are comfortable with the basics of qualitative analysis, you follow our prescriptive approach. While fairly systematic in nature we have endeavoured not to slip into the quasi-scientific approach to qualitative data analysis as practised by Miles and Huberman (1992) and Yin (1989). In other words, while we recognise that qualitative data analysis is largely an inductive, open-ended process that is not easily captured by a mechanical process of assembly-line steps (Lofland and Lofland, 1995), formal guidelines are useful in a learning context. Our main concern is to give you a practical insight in how to analyse qualitative data for the purposes of your study. Once you are familiar with these processes we encourage you to explore different approaches.

Dey (1993) describes his approach to qualitative data using an omelette analogy. He suggests that just as you cannot make an omelette without breaking and then beating the eggs, you cannot undertake data analysis without breaking down data into bits and then 'beating' the bits together. He suggests that the core of qualitative analysis consists of the description of data, the classification of data, and seeing how concepts interconnect. As we noted for quantitative data, analysis is more than just describing the data we want to be able to interpret meanings, and explain or understand the data generated. Description lays the basis for this deeper analysis, but then we need to progress beyond this stage to try to determine the interconnections and relationships between data, and to tease out the ways in which to reconceptualise our constituent bits. Each section of this chapter is designed to guide you through qualitative data analysis using Dey's approach. While the following prescription has been written as if all the data are generated before any analysis starts, it can equally be used to start making sense of data as they are generated. That is, you can start to describe, classify and connect data before you have a full data set. This will help you make sense of the data being generated and to also guide further data generation. In this chapter, we describe the process of analysis and interpretation by hand. In the next chapter, we describe the analysis of qualitative data using a computer.

In order to illustrate how to analyse and interpret qualitative data, four example data sets will be used (Boxes 8.1-8.4). These data were generated as part of a large international study which concerned how blind people interact with and learn urban environments (see Kitchin et al., 1997). The study consisted of three different stages:

The data presented were taken from the interview in stage 1. The interview consisted mainly of closed questions designed to elicit quantitative data concerning levels of blindness and mobility. These closed questions were complemented by questions styled in an interview guide approach, asked after the questionnaire was completed. The data presented were recorded during the interview. The interviews were conducted by Dan Jacobson between March and May 1997 in the Belfast Urban Area. Interviewees were paid £10 for their time. People and place names have been changed. A number of factors should be noted. First, these data are the results of Dan's first-ever interviews. Second, Dan is not visually impaired. Third, prior to the interview both he and the interviewee had never met before. Therefore, a strong research relationship had not yet been forged. Fourth, the interviews were recorded on video as well as tape. As part of his own PhD project, after the interviewees had completed the various stages of the research, Dan reinterviewed some of the respondents. By this stage he had spent quite a long time in the company of each respondent (at least two full days interviewing and retracing routes). In the second set of interviews he found that the respondents were more open and frank about their lives and their experiences of interacting with urban environments. His interviewing skills had also developed and he found that he could probe the respondents more effectively.

While these data are not from a purely qualitative study they are sufficient to demonstrate how qualitative data can be analysed. It should be possible for you to substitute whatever data you have produced, whether from primary or secondary sources, and undertake a similar analysis. For example, you should be able to analyse notes from an observation study or to perform an analysis of secondary, documentary data using this approach. The example data have been chosen for two main reasons. First, one of us has personal experience of the whole study. Second, the data are likely to reflect those generated by first-time interviewers with missing data, leading questions (see if you can

Box 8.1 Interview with respondent A

INT: How do you approach and resolve problems encountered en route?

RES: Such as?

INT: Well, how about detours?

RES: I'm OK with them. But I got lost once. It tends to knock you sideways a bit. I crossed one too many streets and I ended up going in the opposite direction. Well, I would first of all - if I didn't know the area - I would ask someone. Or I would go back on myself and retrace, and maybe get a taxi or some other transport. Or maybe I would go to a friend's house nearby.

INT: How about if you found yourself off-route?

RES: I don't really like finding myself in this situation. If I was caught in a security scare or something like that, I would wait until someone came along, or I would go to the door of a house. Or I would retrace.

INT: Do you come across any specific hazards?

RES: Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there's a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way. When two or three things happen at once, it can be really confusing. The only thing you can do is to backtrack.

INT: Do you think environmental modifications might make navigating easier?

RES: There is a conflict between dropped .kerbs and flush pavements. I can't tell the difference. If you go from Castle Street, from Castle Court, the place where the pavement should be, it just isn't there. There is nothing to tell you where it is, it is all flush. Those bobbly tiles - I don't like those.

INT: How do you find out about new routes?

RES: By asking people. I haven't been down in the town for a while, but I knew there was work done on this part of the road. I didn't realise the Westlink went under the Falls Road. Nobody had ever told me that. I was walking across towards Divis Street, and suddenly I heard the roaring of a heavy thundering truck. 'Shit, this one 's going to get me', I thought. Then it went underneath and I was OK.

INT: How often do you learn a new route?

RES: Very rarely, once or twice a year, most places I go, I go regular.

INT: How do you prepare for learning a new route?

RES: If I can get the information in advance I may go over it beforehand. If I can get detailed instructions, 'cross three roads, turn left, on the up kerb, turn right', it's a great help.

INT: Have any route learning strategies proved to be particularly successful or disastrous?

RES: No.

spot them) and a lack of probing. It should be clear from these interviews that some people are a lot more forthcoming than others! A paper discussing analysis of all the interviews is Kitchin et a!. (1998).

As noted, Dey's approach, like most other qualitative analysis methodologies, consists of the description, classification, and making of connections between the data. Before we detail how you might go about undertaking these tasks, each will be discussed briefly. While presented in turn, it should be noted that the three do not always follow in a strict linear order. The process is more iterative than linear (Dey, 1993). That is, while classification cannot precede description, and the making of connections cannot precede classification, we can go back to modify the previous task and to take a new route into the next task (see Figure 8.1 on p. 235).

Description is central to any study, whether using qualitative or quantitative data. It permeates all levels of enquiry. Description concerns the portrayal of data in a form that can be easily interpreted. For example, a description might be a verbal or written account of the data or a graphical illustration. Description can be either thin or thick in nature. In describing quantitative data we were seeking what has been termed 'thin'

Box 8.2 Interview with respondent B

INT: How do you approach and resolve problems encountered en route?

RES: Say I arrived in town and I wanted to go to a department store, I would get off the bus at the appropriate stop to find that the road had been dug up. The noise of the men working lets me know that they are working, but it is then off-putting as you can't find other sound clues to get around that. I would, perhaps ... if in town, I try to follow the flow of people - use them as guides even though they don't know it. The same is true for crossing roads, rather than asking each time, I would find somebody who I think is reasonably competent and then follow them.

INT: How about off-route?

RES: Generally I don't like this. I can get anxious. Sometimes it is OK though, but especially . .. if I'm not familiar with it I may panic a bit and wonder 'am I where I want to be?', 'Is this where I want to be?' This can happen. One day a few weeks ago I was in big hurry, I was taking my daughter to the opticians, and we had to come back in half an hour. We had a few other things to do so we left the shop to do those. They were in another part of town and then we had to get back to Castle Court shopping centre. Our normal route would be up Royal Avenue and Castle Court would then be on your left. But we found ourselves around Queen Victoria Street and I found myself thinking, 'I wonder if I can cut through these streets?', 'will it bring me out at Castle Court?' Very much a guessing game to head in the right direction. We did get there in the end, but I had my sighted child with me. If I had been there on my own I probably would have gone the long way around.

INT: How do you cope with being lost?

RES: I don't like it, I hate being 'out of control'. It is not a good feeling. It can be an anxious feeling. It's also quite a confidence downer. All of a sudden you are not where you think you are and you feel a bit stupid. You think any other adult could manage this and maybe you can't so you feel inadequate in some way. How I would resolve it would be to ask somebody. This has, believe it or not, taken me nearly 42 years to reach the point where I can ask somebody. You get a whole range of answers that you need emotional strength for, like the 'are you blind?' question.

INT: Are there specific hazards that you encounter?

RES: A lot of shops now have huge amounts of pavement clutter. Sometimes I can see these, pick them out OK. But if it is bright and there are lots of people then I will bump into things.

INT: How do you learn a new route?

RES: By trial and error and by talking to friends. Ifl am going alone I try to remember the way I have been and to fo llow it back.

INT: Do you learn many new routes?

RES: One a month. I would be open to trying out new routes.

INT: How do you prepare for a new route?

RES: Friends, an A to Z with a magnifying glass, and generally try to get as much information as possible to be prepared before I go. Last year I was told I was going away for the weekend but I wasn't told where I was going, it was to be a surprise, and the person I was going with was completely blind. Then I panicked totally. 'How will we ever find our way around?', 'What will we do?', 'How will we manage?' Just total panic really. We flew to Edinburgh and by basically asking people where to get the bus etc. we made our way to the town. Once in town we asked for the street with the hotel on, where we were staying. The first thing we did was to get a map of Edinburgh, I was able to see some of this with my magnifier, although I had trouble translating that into my surroundings. The person I was with could translate this much easier, by not looking for visual cues as he can't see.

INT: Have any route learning strategies proved to be particularly successful or disastrous?

RES: The trip to Edinburgh, it was just one weekend, at the time we came back I felt fairly confident about finding my way. This was news to me, as if somebody beforehand had told me you would go to Edinburgh and be able to find your way about and that you'll manage to do all the things that we did, I would not have believed them. It was a confidence booster and it did prove successful. Another one was unsuccessful. I went to Westport for the day. It was such a small place compared to Edinburgh, but I didn't manage too well. It was built on a square, but I never knew what section of the square I was at. I could have been three-quarters of the way around, when I needed to only go back a quarter, but I would go around. There was a river and a bridge and everyone seemed to go by these, but they didn't mean anything to me. It was frustrating and I was quite disorientated.

Box 8.3 Interview with respondent C

INT: How do you approach and resolve problems encountered en route?

RES: I do have a cane, and I suppose I would use it at night, but not during the day. ' Watch that puddle, watch that kerb, watch that car'. If I could watch the kerb I wouldn't need you to tell me to watch the kerb. I've had 3 months of O&M [orientation and mobility] training with the long cane about 2 years ago for 2 hours a week. If Alison is there, it is a lot easier, picking out the gaps in the wall, or going into shops. When I do go into shops everything just brights out for a moment. So you stand there and look like a wally, everybody looking at you. So it is a lot easier with someone to guide me.

INT: How do you cope with more specific problems, such as crossing roads?

RES: I tend to cloak people, wait on somebody that's going across and then shadow them.

INT: How about attempting detours?

RES: They can be awkward. Generally Alison, my partner, would be with me. If it was left to me I would be in for a lot of trouble, so I would probably ask.

INT: How about if you were off-route or lost?

RES: I would ask somebody. A few times I've been, not lost, but mislaid. Recently, when I was on a course I got the wrong bus one morning. There were two buses leaving Lis burn, one was an express to the back of the City Hall in Belfast and the other one went to Newry - somewhere. I soon knew the bus I was on wasn't going to the right place and I started sort of panicking, and then it was more really of a mental panic; 'I'm in deep shit'. Although in the end I recovered easily enough.

INT: Do you come across many hazards?

RES: I keep bumping into a lot of them such as when I come across them outside shops and the like. Very often I'd be kicking things. And people tend to think, what's up with him, it is a bit early in the day to be drinking.

INT: Do you think improved training would help?

RES: Really it's not the training, the training I had was fine, but for me it was a bit of a let down. I was expecting something a little different, like fai lsafe, or a guide dog. What you think it is about and what it actually is are two different things. My expectations and reality didn't match.

INT: Do you think environmental modifications might make navigating easier?

RES: Some changes are definitely needed. Those wiggly pavement bobbles are good for totals, but for me they are a menace - it throws you. Some places in the shopping centres you have to go up and grope the shopfront looking for the door. You don't know if it is a window or a door. There are just so many things we have to put up with. But for me definitely the likes of kerbstones being painted helps.

INT: How do you find out about new routes?

RES: I don't think I would get maps or anything like that. I would just learn by walking around with a friend. I only need to do something a couple of times and then I've got it. Probably a couple of times a year.

INT: How do you prepare for learning a new route?

RES: Every time, if I was going by myself, I would always have it mentally well worked out. For the first couple of times I would go with my wife. That helps me build up a lot of confidence.

INT: Have any route learning strategies proved to be particularly successful or disastrous?

RES: No, not really.

description - a clear statement of facts; how many, in what form, etc. The description of qualitative data is usually more 'thick' in nature. Thick description seeks to provide a more thorough and comprehensive description of the subject matter. It includes information concerning the situational context, the intentions and meanings associated with an act, and the process in which the situation is embedded. Essentially the thick description consists of the descriptive observations listed in Box 7.8 (in Chapter 7).

A description of the situational context consists of a detailed account of the social settings (e.g., home), social context (e.g., paid interview), and spatial arena (e.g., place) within which an action or phenomenon occurs, and the time frame within which the data were generated. This information is important because it provides a detailed account in which to situate the analysis. It is well known that the social, spatial and temporal context can all significantly affect the data generated. We must, therefore, be able to take into account any factors which may have influenced the nature of the data when conducting our analysis. This information also allows us to compare data generated under different circumstances.

The intentions and meanings of the actors (i.e., people being interviewed) similarly provide us with

Box 8.4 Interview with respondent D

INT: How do you approach and resolve problems encountered en route?

RES: Such as?

INT: Detours, for example?

RES: Well, most obstacles are small and in areas that I'm familiar with it certainly wouldn't be a problem - I would just take an automatic route to bypass them. For example, I was on the Antrim Road, lines of shops, traffic and there was CableTel digging holes. There were pneumatic drills going, it was really disorientating - I couldn't use the traffic noise to work out which way I was facing. So I turned, took the dog to the kerb to reorientate myself, turned back and walked through the parallel streets that I know.

INT: How about if you were off-route?

RES: It doesn't usually happen, but if I was unsure I would retrace my steps. I've never been totally lost, but disorientated, for sure. One time another dog came up and we got entangled and spun around, there was no traffic to orientate myself so again I had to take my dog to the kerb and get my bearings.

INT: Do you thi11k ellvirollmelltal modijicatio11s might make 11avigati11g easier?

RES: Yes. Tactile pavements need to be standardised and there need to be more of them. Shopfronts with baskets and stalls are a nightmare, but you can't outlaw that.

INT: How do you ji11d out about 11ew routes?

RES: With some difficulty, but mainly when I come across them.

INT: How oftell do you /eam a 11ew route?

RES: Not very often, but for example I've learned a new route for a course I am attending.

INT: How do you prepare for a 11ew route?

RES: I'd walk over it with someone from Guide Dogs 'down kerb to up kerb, keeping the traffic on my right'.

INT: Have any route learning strategies proved to be particularly successful or disastrous?

RES: No.

contextual information. However, unlike situational context factors, these data are more difficult to record and unless stated by the interviewee require some interpretation. In our data, the intentions and meanings of the actors when navigating an environment are recorded in some of their answers. In an observational study it would be difficult to insinuate (imply) some of their responses purely on the basis of observing their actions. However, it must be remembered that what is said in an interview is not always the same as what the interviewee actually believes or what they would actually do. As noted in Chapter 7, an interviewee will sometimes give the answer they think you want to hear, rather than their own opinion. We therefore cannot always rely on interviewees giving truthful and rational statements concerning their intentions or meanings.

Qualitative data generation rarely consists of snap shot studies. Interviews and observation are often the product of several encounters over a period of time. As such, data generation is usually part of an ongoing process of social relations. Another type of description then concerns the extent to which situational context, intentions and meanings remain stable or change over various encounters. Further, a focus on process allows us to examine the consequences of action and subsequent alterations in thought or behaviour. This descriptive data can relate to both the people or phenomena under study but also to the researcher. As the research has progressed, so will the researcher's thinking and possibly her/his approach. The researcher's own field notes can therefore become a useful source for contextualising the progress and process of the research. These field notes should be analysed in the same manner as described below.

Classification is where you move beyond data description to trying to interpret and make sense of data. By undertaking interpretative analysis you are seeking to understand the data generated more fully and make the data meaningful to others. The classic way to start to make sense and interpret qualitative data is to 'break up' the data into constituent parts and then place them into similar categories or classes. In this process we start to identify which factors are important or more salient; to draw out commonalities and divergences. By classifying the data we can start to make more effective comparisons

Figure 8.1 Description, classification and connection.

between cases. While we naturally or implicitly classify objects in our daily lives (e.g., types of shop or transport), classification within the research process is more systematic and explicit. Implicit classifications help us make sense of our world. In contrast, systematic classifications help the researcher under stand the thoughts and actions of several people. As such, different classification classes do not have to be defined by the actors or their actions within the research but can be imposed by the researcher. For example, it might seem logical to classify our visually impaired interviewees into:

Alternatively we could use something less tangible like interviewees' answering style, whether they are positive or negative in their responses, etc. In other words, classification is more than the identification of the most logical or implicit classes within the data. Which classification we choose to impose is dependent upon what we wish to examine. Clearly, there are some data that do seem to classify themselves. The majority, however, need to be purposively sorted and a carefully selected order imposed. Undertaking classification, effectively 'breaking up' your data and collecting like-with-like against some standard, means that your data lose their original format (e.g., interview transcript). What is gained is an organisation which will aid further analysis and the process of interconnection. We will examine the process of classification in more detail in Section 8.5.

Classification is concerned with identifying coherent classes of data. Connection is concerned with the identification and understanding of the relationships and associations between different classes. This consists of more than just identifying the similarity or difference between categories. Instead we are more interested in the interactions between classes. Dey (1993), using a building analogy, suggests that whereas classification concerns putting all the bricks, frames, glass panes and beams in separate places (and classifying these according to type, size, etc.), making connections concerns how they fit together and relate to one another as a structure such as a house. In other words, our data generation may lead to a building yard full of material. Our analysis consists of describing the yard's material so that we know what we have and why, classifying the various data forms into relevant building materials, and connecting the classes together to construct a coherent and stable structure. Clearly if analysis is occurring as an ongoing process our structure might undergo several modifications and extensions as the building material is refined and classed more effectively. If you have started from the position of testing a theory then the structure built should generally conform to some sort of plan (theory). If, however, you are inductively building a theory then your final construction will provide the blueprint of your theory.

Figure 8.2 Interrogating data.

As we will discuss in Section 8.6, making connections is not always a simple process. One common method is to search for recurring patterns within the data. This is achieved by identifying whether individuals with a particular characteristic also possess other common features. For example, do all guide dog users utilise the same procedures for reorientating themselves? The question now, if the answer is 'yes', is why? Is there some evidence within the data to suggest why this might be the case? Do they share other characteristics such as the same training? Again, if 'yes', does this lead to similar experiences when navigating? If the answer is 'no', then why? If these interviewees share so many characteristics in terms of training and procedure when navigating, why do they have different experiences when navigating? Again are there any clues within the data? At this point we are shifting from examining the relationships as if they are external and contingent. That is, we are moving beyond identifying whether there are relationships between data to trying to find a reason why any relationship apparently exists. A useful way to do this is to visualise the process as a flowchart (see Figure 8.2). By interrogating data in this way we are slowly building up a picture of the experiences of visually impaired people when interacting with an environment. In order to explain some of the connections it might also be necessary to draw on evidence from beyond your data, for example the findings of others.

The first stage after you have generated your data is to transcribe your notes or interviews into coherent transcripts. This should be done as soon after data generation as possible. If the data are from a secondary source the relevant sections should be transcribed. There are two main methods of transcribing your data. The first is to transcribe all the data provided within one data generation session onto a single script (e.g., as in Box 8.1). This has the advantage that the whole script can be read as a coherent text. An alternative would be to transcribe and collate the responses to each question separately (e.g., as in Box 8.5). This has the advantage that the responses to each question can be viewed together easily, but makes the reading of one interview difficult. We recommend that the first strategy be used, as once transcribed as a full text, it is relatively easy to divide the transcript up into individual question responses. In addition to the transcription of the data, it is important that you also fully transcribe the 'thick' description to accompany the data. In our example, we have transcribed inter view data. If you have undertaken an observational study or examined secondary sources you should simply substitute your entries for ours.

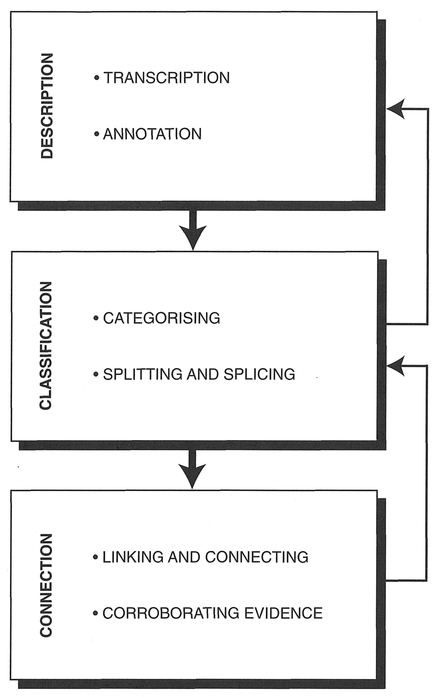

There are also two main ways in which you can transcribe your data. First, as we have done, you can just copy out what was said using a minimum of codes (e.g., ' . . .'means a pause). An alternative is to use a much more rigorous method of transcription. In general, the more rigorous method is applied only to interview data, although it could be applied to other data. We suggest that unless necessary (e.g., you are interested in speech patterns) you transcribe your data using a minimum selection of codes (see Box 8.6). This will save unnecessary data preparation and valuable time. Remember, the transcription of data is very time consuming. A one-hour interview can easily take up to 6-9 hours to fully transcribe and annotate. In order to try to minimise time and effort we recommend that you follow some general rules (see Box 8.7).

Box 8.5 Transcribing each question or theme separately

(Details of each interviewee held on master cards)

INT: How about if you found yourself off-route?

RES: I don't really like finding myself in this situ ation. If I was caught in a security scare or something like that, I would wait until someone came along, or I would go to the door of a house. Or I would retrace.

INT: How about off-route?

RES: Generally I don't like this. I can get anxious. Sometimes it is OK though, but especially ... if I'm not familiar with it I may panic a bit and wonder 'am I where I want to be?', ' Is this where I want to be?' This can happen. One day a few weeks ago I was in big hurry, I was taking my daughter to the opticians, and we had to come back in half an hour. We had a few other things to do so we left the shop to do those. They were in another part of town and then we had to get back to Castle Court shopping centre. Our normal route would be up Royal Avenue and Castle Court would then be on your left. But we found ourselves around Queen Victoria Street and I found myself thinking, 'I wonder if I can cut through these streets?', 'will it bring me out at Castle Court?' Very much a guessing game to head in the right direc tion. We did get there in the end, but I had my sighted child with me. If I had been there on my own I probably would have gone the long way around.

INT: How do you cope with being lost?

RES: I don't like it, I hate being 'out of control'. It is not a good feeling. It can be an anxious feeling. It's also quite a confidence downer. All of a sudden you are not where you think you are and you feel a bit stupid. You think any other adult could manage this and maybe you can't so you feel inadequate in some way. How I would resolve it would be to ask somebody. This has, believe it or not, taken me nearly 42 years to reach the point where I can ask somebody. You get a whole range of answers that you need emotional strength for, like the 'are you blind?' question.

INT: How about if you were off-route or lost?

RES: I would ask somebody. A few times I've been, not lost, but mislaid. Recently, when I was on a course I got the wrong bus one morning. There were two buses leaving Lis burn, one was an express to the back of the City Hall in Belfast and the other one went to Newry - somewhere. I soori knew the bus I was on wasn't go ing to the right place and I started sort of panicking, and then it was more really of a mental panic, 'I'm in deep shit'. Although in the end I recovered easily enough.

INT: How about if you were off-route?

RES: It doesn't usually happen, but if I was unsure I would retrace my steps. I've never been totally lost, but disorientated, for sure. One time another dog came up and we got entangled and spun around, there was no traffic to orientate myself so again I had to take my dog to the kerb and get my bearings.

Effective transcribing consists of more than just accurately writing down an interview or observation. While transcribing you should be thinking carefully about what is being transcribed, trying to get a feel for the data, and starting to develop ideas about specific lines of enquiry. As such, while transcribing your inter views you should jot down ideas and memos relating to the transcription. You should try to distinguish between ideas and memos. Ideas relate to your own thoughts about the data. Memos are notes about the data. It is here that you have started the process of description. You should jot down notes immediately, before your inspiration disappears. Once you have finished the complete transcription you should then thoroughly annotate the transcript. Start annotating your data immediately after transcribing it, while both the interview and transcription are still fresh in your mind. In this way your annotations will be fully situated within the context of the data. While transcribing and annotating might seem like a boring chore, they have their utility. Transcribing requires you to study each interview, and annotating forces you to think about the data. Your annotations, in particular, open the data up and start the process of analysis in earnest. Annotating your data now will make subsequent categorisation and connecting easier. Annotations are also extremely useful guides to future data generation.

There are a number of strategies you can use to aid the process of annotating your transcripts. Box 8.8 provides a description of each. Each strategy makes you think about your data in a slightly different way. Using a combination of these strategies will allow you to examine different possibilities and will shed light on your data that you might not otherwise have thought of. To illustrate the transcription process Box 8.9 (on p. 240) details the initial annotation notes for

We recommend that you use only a sample of these codes (the first five listed). The ones we would avoid, unless necessary, are those which concern speech patterns and timings. While these codes might, at first, seem tedious to use, they are quick to learn and soon become natural additions to your transcriptions. Adding these codes will provide a richness to your transcript that will aid subsequent analysis.

Source: Adapted from Silverman 1993: 118.

Box 8.7 General rules for transcription

Respondent A's transcript. Box 8.10 (on p. 241) illustrates the full annotation notes once transcription has been completed. The full annotated notes for the other three data sets are listed in Appendix B. Note how the initial annotation has been used as pointers to aid full annotation. We have also detailed whether the annotation is a memo (m) or idea/thought (i) to illustrate the difference between the two. Information in square brackets is presented only to help you understand abbreviations or specialised terms. These annotated notes (and the notes accompanying the other transcriptions) will now be used to help focus analysis and identify categories. Equally they could be used as a reference for subsequent data generation.

Once your data are transcribed and you have decided specifically what to focus your analysis upon, you need to start categorising and then connecting your data. It is to this that we now turn.

In many respects categorising quantitative data is relatively straightforward. Numeric data are easily grouped into ordinal, nominal, interval and ratio categories

Box 8.8 Strategies to aid annotation

Source: Adapted from Dey 1993: 83-88.

and the relationships between data in these categories are logical (e.g., 1 < 2). Categorising qualitative data is not so simple. Because the data consist of non-numeric information there can be few logical relationships between the data. Placing qualitative data into meaningful categories, then, can be a tricky task. Your annotated notes, however, should make this task much easier. This is because, in part, your annotations represent informal coding strategies.

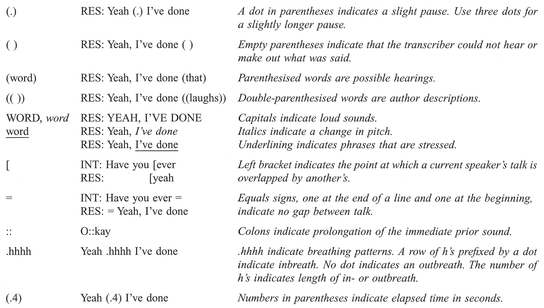

The task now is to log the data within the transcripts into formal categories to aid further analysis. While your annotations might have provided you with a pretty good feel for your data, categorisation will allow further and deeper insights. The main question you need to ask yourself at this point is: 'on what basis are data going to be assigned to categories?'. Generally speaking, you are seeking to identify the similarities and differences between data. This is not always an easy task and is part of a creative process. As we described in Section 8.2, there are any number of ways we can categorise the same data. We can demonstrate this with a small example. Sears Tower (Chicago), the Grand Canyon, the River Nile and the Pyramids might be classified into three different clas sifications (Figure 8.3 on p. 242).

All three classifications lead to different pairings. The decision as to which scheme to use really centres upon what you interested in and the quality of your data. Remember that there are many different ways of seeing the same data. None are right or wrong, but some are more appropriate than others.

The easiest way of classifying your data, if you have carried out a systematic interview or observation study, is to group the answers to specific questions or observations. While this might seem logical, it does not always make the best line of enquiry. Our suggestion is to think carefully about the focus of your analysis - what you really want to know about - and then using your annotated notes devise a series of master categories. If, after you have started to code your transcripts, you change your mind about the categories you wish to use, you can always go back one or several stage(s) and modify or extend a category (or categories) or devise a new one (or set). Creating categories is a continual process of development as you refine your ideas. When starting and throughout the process, remember you are seeking to group like-with-like, creating a series of category levels that work from the general to the specific. To do this effectively each category must be easy to identify and clearly distinguishable from others. That is, you must have a well-developed set of criteria for placing data into different categories. This does not mean that all categories must be mutually exclusive - in some cases the same data can belong to more than one category. These criteria should be conceptually and empirically grounded. That is, criteria should relate to the overall focus of analysis but should also have some empirical basis (the data can be easily classed in this way). In general, if you have to force your data into categories then you need to think of a new classification. Dey (1993) thus suggests that categories should have an internal aspect (they must be meaningful in relation to the data - i.e., they should not be arbitrary) and an external aspect (they must be meaningful in relation to other categories). Categories then should not be created in isolation from other categories within the analysis. They should relate to each other in meaningful ways.

Figure 8.3 Categorising data.

After studying our data (Boxes 8.1-8.4), we de cided that the three things we were most interested in were:

We have chosen these three categories as they most directly relate to the main aspects of the overall study. In our project, we were interested in how visually impaired people interact with and learn urban environments. These then are our master categories. They are clearly defined and easily distinguishable (see Box 8.11 ). However, as they stand, these categories are very broad in nature. Just assigning the relevant portions of data to these categories will not provide sufficient disaggregation to make analysis easier. This would especially be the case if we were categorising the data from all 20 interviews rather than just four. We therefore need to disaggregate (refine) our data further by devising some sub-categories. This means examining the data more closely by carefully sifting through the transcripts to identify possible sub-categories. One possible way to make this process easier is to undertake the next two steps (assigning codes and sorting data) and then follow the process through once more, treating each of the four main categories as separate data sets. Following this iterative process, however, we must be careful to ensure that data from within the main categories is still coded in any appropriate sub-categories that may have grown out of another main category. In other words, this process is no substitute for sifting through data. Category development, if done properly, requires you to become thoroughly familiar with the data. Taking short-cuts will lead to deficiencies in your analysis. Admittedly this may be necessary, given time constraints, but be aware of potential shortcomings.

Box 8.11 Criteria of inclusion in master categories

| Spatial confusion: | include data about spatial behaviour, getting lost, confused or disorientated. |

| Situational confusion: | Include data about specific hazards or situations. |

| Learning strategies: | Include data about how people learn new routes, specialised training. |

Note how these categories relate to each other.

There is no limit to the number of categories you can develop. However, while the list needs to be comprehensive, you need to find a balance between depth and breath. With not enough categories, the data will be difficult to compare. With too many categories, it will be difficult to assign data to categories because of similarities and overlaps. It will also be difficult to relate categories and develop links further on in the analysis. We suggest progressing with categorisation up to the point where the data within categories seem to sit naturally with one another and no further divi sion is immediately obvious. The categories you do determine must be exhaustive. All useful data must be able to reside in an appropriate category. In addition, we recommend that you are also careful to record why you have chosen your category choices over others. This will be useful at a later stage if you are trying to remember why you have assigned data in certain ways. Figure 8.4 illustrates all the categories identified for the purpose of our study and how they relate to each other.

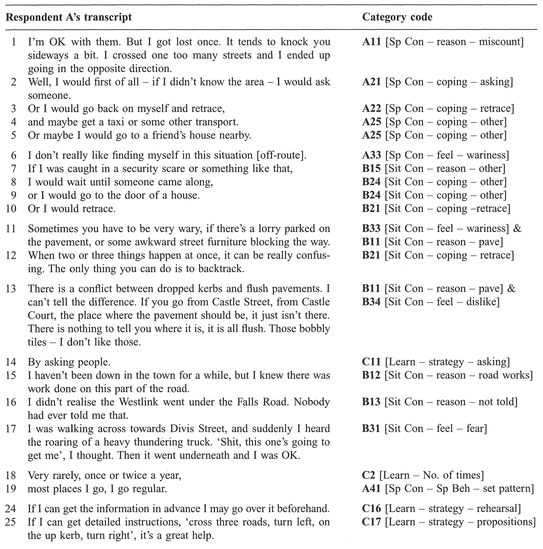

Once you have decided how the data are to be categorised you need to assign data within your transcripts to specific categories. This process is known as coding. The easiest way to code your transcripts is, using a photocopy, to work your way through each of the transcripts, placing a specific code next to each relevant piece of data, termed a databit. A relevant section of data might consist of a phrase, or a sentence, or even a whole passage. As we have discussed, this is an ongoing process as you refine your choice of categories. The codes you use should be recorded on a master sheet. Remember that your data may well belong to more than one category. It should be coded as such, otherwise a salient point might be missing from some categories. When assigning codes to your data you should also do the same with your memos and ideas. Linking together relevant data and annotation through coding will help further analysis. Although it is probably sensible to work through the data in a sequential manner, you should by this stage be sufficiently familiar with the data to use a selective path of coding. Remember, you are sorting your data only into the categories at the bottom of the category tree (see Figure 8.4). The upper levels exist only to show you the pathway and links between the categories. In terms of analysis these are redundant as there is no point in replicating the data at all different levels. Box 8.12 illustrates the codes assigned to Respondent A's transcript. To aid your analysis we suggest that you adopt a similar format. The coded transcripts of Respondents B, C 'and D are provided in Appendix B.

Figure 8.4 Category codes for example data

When you have completed the coding process on your data, the next task is to sort the data into the relevant categories. This consists of a cut-and-paste process. When completing the task using a word-processor or by literally cutting up and pasting photocopies of your transcripts together, good data management really comes to the fore. Before you cut-and-paste you must devise a suitable filing system. If you cut up your transcripts and paste them back together again without labelling your pastings with master codes relating to the source of the data, you will soon become confused as to where a piece of data originated. Similarly you should keep a master record of where all the pastings of a source have been copied to. This housekeeping, whiie time consuming and tedious, will improve the efficiency and level of analysis at a later date. It will also stop your analysis from falling into disarray. Box 8 .13 is an example of a sorted category.

Box 8.12 Coded transcript for respondent A

Note that this is an edited transcript- only the data that have been coded are present. The annotations have also been removed. The transcript has been placed into blocks and numbered phrases. Each block represents what was a passage in the original transcript. Each numbered phrase is a piece of coded data ( databit). The relevant code is listed on the same line. To help you understand the coding system, we have provided a summary code rather than just an abbreviation. Usually you would just use an abbreviation, referring to your master sheet for full details. In places we have provided brief context annotation within the transcript (e.g., [off-route]).

At this point, your data should be in two different forms: the original transcripts and as sorted categories. While our attention, up until now, has focused upon annotating, categorising and coding the original transcripts, we are now about to shift our focus to the sorted categories. Splitting and splicing is concerned with reassessing the organisation and data management

Note that this contains both data and annotations. Also, there are two identifying labels, e.g., RES A (respondent A) and (8) (number of line in transcript the databit came from), so that all the data and annotations can be traced back to their original sources. Remember that these data are drawn from only four interviews. With more interviews the richness of this category would improve.

CATEGORY B11 [Situational confusion - reasons pavement]:

i) RES A: (II) Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there 's a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way.

ii) RES A: (13) There is a conflict between dropped kerbs and flush pavements. I can't tell the difference. If you go from Castle Street, from Castle Court, the place where the pavement should be, it just isn't there. There is nothing to tell you where it is, it is all flush. Those bobbly tiles - I don't like those.

iii) RES B: (12) A lot of shops now have huge amounts of pavement clutter. Sometimes I can see these, pick them out OK.

iv) RES C: (11) I keep bumping into a lot of them [hazards] such as when I come across them outside shops and the like. Very often I'd be kicking things.

v) RES C: (14) Those wiggly pavement bobbles are good for totals, but for me they are a menace - it throws you.

vi) RES D: (7) Tactile pavements need to be standard ised and there need to be more of them.

of data within sorted categories. Just as we carefully sorted through our original transcripts, we now turn to sorting through our reorganised data. This stage then has two purposes. First, we consider ways of refining or focusing analysis in the light of any revelations while categorising the data. 'Playing' with the data in various ways (annotating, categorising, sorting) will probably have led to insights that just reading the transcripts alone will have failed to highlight. Second, this acts as a cross-checking phase. Some of our categories may be large and cumbersome, needing further refinement, and some, while seeming valid and important during categorisation, are small · and need to be merged and integrated to be viable.

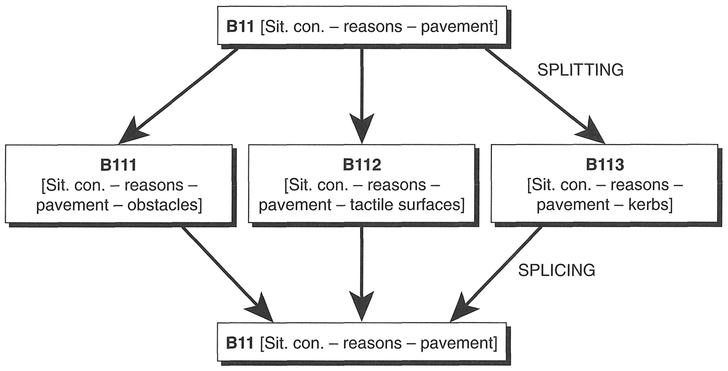

During the process of creating, modifying and extending our categories we have created a number of databits (coded pieces of text). These have been assigned to sorted categories (see Box 8.13). By categorising the data and placing them into sorted categories we have removed the data from their original context. In return, we have gained a new way to think about our data. It is now easy to compare data relating to a similar theme (e.g., pavement-based hazards). In order to refine our analysis and also compare data within a category, Dey (1993) suggests that the data should be categorised further. Splitting refers to the task of refining the analysis of the data by sub-categorising databits within a sorted category (Figure 8.5). Clearly, we have already 'split' our data several times to categorise the original data. However, in the last stage (categorisation) we divided up our transcripts into separate databits which were then placed into categories. Here, we are not trying to create new databits, just to categorise existing databits into relevant sub-categories. These sub-categories should be internally consistent (e.g., the data within each should refer to the same things), be conceptually related to each other (e.g., all categories are variations on a theme), and be analytically useful (e.g., they relate to the aims of the study). The aim here is to identify the various dimensions of the data and to start establishing the associations and relationships between data. Not all sorted categories will merit splitting. In some, the data will be relatively consistent, in others the data might be more complex. Also some categories will be of more interest than others. For example, in our analysis we may have become particularly interested in confusion caused by situational hazards. We

Figure 8.5 Splitting and splicing data.

therefore might decide to further analyse data within those categories by seeing whether we can split the data further. Box 8.14 illustrates the splitting of subcategory B II [pavement-based confusion]. By splitting the data within this category we are seeking to identify particular hazards or annoyances that visually impaired people encounter when navigating along pavements.

Splicing, alternatively, concerns the interweaving of related categories (Figure 8.5). While we split categories for greater resolution and detail, we splice categories for greater integration and scope. Splicing categories together is a search for understanding how different themes intertwine and relate to each other. In its simplest form, splicing just takes the form of re-merging categories together. For example, if we had originally classified our pavement sub-categories as full categories (e.g., B 111 [Sit Con - reason- pavement - obstacles], B112 [Sit Con- reason - pavement - tactile], B 113 [Sit Con - reason- pavement - kerbs]) we might want to splice these together to get an inte grated picture of the role of pavements in situational confusion. Similarly we might want to splice together situational coping strategies or learning strategies to try to gain a greater understanding of these processes. Alternatively we might splice together categories in different parts of our category schema, for example all the data concerning coping strategies regardless of whether they relate to spatial or situational confusion. Dey (1993) suggests that splicing provides a greater intelligibility and coherence to analysis through the informal linking of associated data. Splicing should also be seen as a method of integrating, and not ignoring, relevant data that sit in more marginal (less central) categories. That is, splicing is used to re-sort data in a process of bringing marginal or small categories to the centre through integration. This creates a smaller number of stronger and more central categories. As we can see by looking through the categories we assigned data to, many of them are small in size. By merging them together we ensure that the relevance of these data is not ignored through a concentration on the 'richer' categories. For an example of splicing, return to Box 8.14. Instead of identifying sub-categories, imagine a reversal of the process so that these sub-categories are merged to create a univtersal pavement category (our original B11 category).

Splicing, like splitting, is time consuming and should be undertaken only after careful consideration of which data are to be spliced together and whether the resultant category will be strongly related to the central themes of the study. The processes of splitting and splicing should not, however, be avoided as they do provide quite powerful tools to gain further insight into your data. It should be noted that while splitting and splicing provide further depth to the process of categorisation and allow better comparison between data, they do not identify the nature of the relationships between data. It is to this that we now turn.

The tasks of categorising, sorting, splitting and splicing data have allowed us to analyse our data through

Box 8.14 Splitting sorted data

B11 [Situational confusion- reasons- pavement]:

i) RES A: (11) Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there's a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way.

ii) RES A: (13) There is a conflict between dropped kerbs and flush pavements. I can't tell the difference. If you go from Castle Street, from Castle Court, the place where the pavement should be, it just isn't there. There is nothing to tell you where it is, it is all flush. Those bobbly tiles - I don't like those.

iii) RES B: (12) A lot of shops now have huge amounts of pavement clutter. Sometimes I can see these, pick them out OK.

iv) RES C: (11) I keep bumping into a lot of them [hazards] such as when I come across them outside shops and the like. Very often I'd be kicking things.

v) RES C: (14) Those wiggly pavement bobbles are good for totals, but for me they are a menace - it throws you.

vi) RES D: (7) Tactile pavements need to be standard ised and there need to be more of them.

RES A: (11) Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there's a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way.

RES B: (12) A lot of shops now have huge amounts of pavement clutter. Sometimes I can see these, pick them out OK.

RES C: (11) I keep bumping into a lot of them [hazards] such as when I come across them outside shops and the like. Very often I'd be kicking things.

RES C: (14) Those wiggly pavement bobbles are good for totals, but for me they are a menace - it throws you.

RES D: (7) Tactile pavements need to be standardised and there need to be more of them.

RES A: (13) There is a conflict between dropped kerbs and flush pavements. I can't tell the difference. If you go from Castle Street, from Castle Court, the place where the pavement should be, it just isn't there. There is nothing to tell you where it is, it is all flush. Those bobbly tiles - I don't like those.

While the initial category (B11 is small) and the sub -categories contain only a couple of entries each, remember that these data have come from only four short interviews. If all 20 interviews had been included each of these sub-categories would increase in size.

comparison. When undertaking these tasks we have been involved in a process of deciding how similar or dissimilar pieces of data are. We have formulated a basic understanding of data within specific categories and identified some common links between categories. As such, by this stage we have got a pretty good 'feel' for the data. However, the common links identified need to be explored further, their existence ratified and their nature determined. Further, as we have already noted, by breaking up the data and reorganising it in sorted categories we have taken the data out of context and lost information regarding the relationships between individual databits. In other words, we have lost information concerning how the data 'hang together'. Linking and connecting concern the process of trying to identify how the reorganised data 'hang together' within the context of the original transcripts. Rather than just being able to say how alike or similar the data are, we are trying to identify and understand the nature of relationships between data: how things are associated and how things interact. There is a difference between association and interaction. In association, separate events occur together (when one thing happens so does another; A → B). In interaction, there is an engagement between the two events (A ← → B).

Clearly, things that are associated or interact with each other need not be similar (e.g., a person is very different from a pavement but there is clearly a link as people use pavements). Whereas categorisation and comparison concerned the identification of formal connections (similar/different), finding associations and links concerns the identification of substantive connections. There are two different types of substantive connections (see Sayer, 1992). Internal relations are necessary; one does not exist without the other. For example, without sight you are blind (conversely if you did have sight you would not be blind). There are no alternatives. External relations are contingent or non-necessary; a substantive relationship may exist but need not do so. For example, a blind person can, but does not need to, use a guide dog to navigate. Many of the approaches within the social sciences seek to identify substantive relations (laws) between social entities: those things that are necessary for certain things to happen. Of course, most social relations are extremely complex, consisting of a series of contingent measures. Here, many social scientists try to work out what happens when some contingent relations exist and others are absent. This is the same whether the researcher is from a quantitative or qualitative background, is seeking understanding or explanation, or is using deductive or inductive approaches: the researcher is trying to figure out how data are substantively linked (internally or externally).

So far, we have not attempted to identify substantive links between our data. We have not, for example, examined whether there is a link - internal or external - between a certain type of spatial confusion and a certain type of coping strategy. If a visually impaired person becomes disorientated by miscounting streets, do they necessarily undertake a retracing coping strategy (that is, all visually impaired people in this situation will retrace) or is the choice more contingent (that is, they undertake a coping strategy but this varies from person to person)? The next stage, then, is to try to identify the links between data and the nature of those links (internal/external). As we have stated, these links do not need to be causal (e.g., X causes Y) but can take any form (e.g., X dislikes Y, X scares Y, X supports Y, etc.).

The best place to start is by going back to our original transcripts and seeing what links we can identify within the text (Box 8.15). The links we find within the transcripts will provide the basis for exploring wider connections between the data now stored within the sorted categories. Some of these links will be intuitive and may have formed the basis of categorisation (e.g., AI [reasons for spatial confusion] and A2 [coping strategies]), but it is best to go formally through each transcript so that some of the less obvious links are established.

It is clear from Box 8.15 that there are clear links between spatial and situational confusion, personal emotions and feelings (e.g., wariness, fear, disorientation), coping strategies and learning strategies. Having established this in an informal manner we now move on to explore the nature of these links more fully. At present, we do not know how these links operate or the relationships between links - just that they seem to exist.

To try to connect the bones of our skeleton together we can use a few different techniques. At a simple level we can use a matrix to compare associations between individual transcripts (see Table 8.1). This matrix reveals all the categories an individual has databits assigned to (identified by an 'x' in the appropriate cell). By looking for similar patterns we can try to establish how the data relate to each other. Unfortunately, from our data, little clear pattern is emerging. This is in part because we have used only four data sets, but it may also be because the links between our data are contingent and therefore things like coping strategy can differ between individuals. What is clear is that coping strategies do seem to differ slightly for spatial and situational confusion. While three of the respondents said that they would ask for help when spatially confused, none would do so when situationally confused. There are also a wide range of coping strategies.

A second strategy would be to categorise the links identified within the transcript, placing the linked data into new sorted categories. For example, Box 8.16 contains all the link data between situational confusion and coping strategies. Nearly the same effect could be produced by splicing together all the coping category data (e.g., B21- B24). However, the data would not be as rich in nature, as not all the databits presented in Box 8.16 would be present (see next strategy). Looking at these data it is clear that there are very strong links, as might be expected, between situational confusion and the use of coping strategies. This substantive link is internal, in that without situational confusion there would be no need for coping strategies; however, the link is also contingent, as the particular coping strategy employed is not determined. If we were to look now at the links between situational confusion and people's feelings, we would see that there is also a strong link between them (Box 8.17 on p. 251 ). It would therefore be reasonable to suggest that coping strategies are employed in times of situational confusion because of fear, anxiety and wariness. However, people also worry about these situations because they feel that they make them look silly, and such situations make them feel embarrassed. The link be-tween coping strategies and anxiety/fear is rarely stated in the data. The link, although inferred, has been determined through lateral thinking by examining two related data categories. Although intuitive, it has taken extensive data analysis through description, categorisation and linking to provide sufficient evidence to support this claim.

A third strategy builds upon the last strategy but relies exclusively upon the sorted data. This approach, rather than searching for explicit links and identifying some implicit connections, focuses solely upon investigating possible implicit links. As such, this strategy involves lateral rather than literal thinking.

Table 8.1 Using a matrix to identify links.

Linking situational confusion (italics) and coping strategies (underlined)

RES A: Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way. When two or three things happen at once, it can be really confusing. The only thing you can do is to backtrack.

RES B: Say I arrived in town and I wanted to go to a department store, I would get off the bus at the appropriate stop to find that the road had been dug up. The noise of the men working lets me know that they are working, but it is then off-putting as you can 't find other sound clues to get around that. I would, perhaps ... if in town, I try to follow the flow of people - use them as guides even though they don't know it. The same is true for crossing roads, rather than asking each time, I would find somebody who I think is reasonably competent and then follow them.

RES C: I tend to cloak people, wait on somebody that's going across and then shadow them.

RES D: Well, most obstacles are small and in areas that I'm familiar with it certainly wouldn't be a problem - I would just take an automatic route to bypass them. For example, I was on the Antrim Road, lines of shops, traffie and there was CableTel digging holes. There were pneumatic drills going, it was really disorientating - I couldn't use the traffic noise to work out which way 1 was facing. So I turned, took the dog to the kerb to reorientate myself, turned back and walked through the parallel streets that I know.

You start by asking whether a link could possibly exist between two categories (e.g., X1 and Y1) and what the form of this link might be. Then by looking through the data in Xl and Yl you try to determine if there is any evidence to suggest that such a link might exist even if the data do not explicitly state such a link. Within the sorted categories, any explicit links have often been removed by categorising the

Linking situational confusion (italics) and feelings (underlined)

RES A: Sometimes you have to be very wary, if there's a lorry parked on the pavement, or some awkward street furniture blocking the way. When two or three things happen at once, it can be really confusing. The only thing you can do is to backtrack.

RES A: By asking people. I haven't been down in the town for a while, but I knew there was work done on this part of the road. I didn't realise the West/ink went under the Falls Road. Nobody had ever told me that. I was walking across towards Divis Street, and suddenly I heard the roaring of a heavy thundering truck. 'Shit, this one's going to get me', I thought. Then it went underneath and I was OK.

RES B: I keep bumping into a lot of them [hazards] such as when I come across them outside shops and the like. Very often I'd be kicking things. And people tend to think, what's up with him, it is a bit early in the day to be drinking.

RES C: When I do go into shops everything just brights out for a moment. So you stand there and look like a wally, everybody looking at you. So it is a lot easier with someone to guide me.

data into separate, distinctive databits. It is at this point that we really start to interpret qualitative data - to try to make inferences in the light of annotating, categorising and sorting the data. This stage is probably the most difficult as it relies on the ability of the researcher to think laterally and connect data together in meaningful ways, despite the lack of explicit links.

There are two ways of trying to negate the problem of missing links and make informed inferences. First, we can compare the data assigned to different categories, and look for evidence of possible connections between them. It may be the case that some of the data might have been assigned to both categories. If so then obviously there is a link between the two. If not, is there evidence to link the categories? Using our example, in Box 8.18 a spliced situational confusion category (all the reasons for situational confusion spliced together) is compared with a spliced coping strategies category (all the strategies for coping with situational confusion spliced together). Note that we do not need to use spliced categories - we have done so only to provide sufficient data for comparison given our small data set. It is clear from comparing these spliced categories that there is an integrative link between situational confusion and coping strategies: when a blind person encounters a confusing situation they employ coping strategies to try to minimise the confusion (situational confusion ←→ coping strategies). This becomes increasingly evident if we compare the sequence of line numbers between respondents - coping statements almost invariably follow statements of confusion. However, just from the difference between the number of entries, it is clear that many of the confusion statements were not accompanied by coping statements. We therefore have to infer that coping strategies did occur in all these other situations - they were just not articulated in the interview. This might seem a reasonable conclusion to draw. You should, however, be careful of drawing definitive, universal conclusions from inferences. It is highly probable that coping strategies are used when confusing situations occur - from our data we do not know whether this happens on all occasions. There might be exceptions that we do know about.

A second approach to dealing with missing links might be to look through a single sorted category to try to infer any associations or links. If any connections are identified then we can look through other sorted categories for more evidence. For example, looking through the entries in the sorted category Bll (Box 8.13), it is clear that there are a number of issues which hinder visually impaired people's use of pavement areas. The implied tone within the statements is that something needs to be done to improve the planning and building of these areas. There is an implied link between situational confusion and better planning. This link is, however, only implied. To strengthen our claims we need either to find an explicit link or to corroborate our evidence. It is to corroboration we now turn.

The corroboration of conclusions is an extremely important part of qualitative data analysis. The processes of qualitative analysis is much like being a detective. You have the accounts from a number of sources which you then need to piece together and try to determine what is going on. Since the qualitative analysis · is interpretative and relies on your ability to

Box 8.19 Corroborating conclusions

Source: Adapted from Dey 1993: 219- 236.

make informed and impartial judgements, the process is open to abuse. Evidence can be fabricated, discounted and misinterpreted. The first two practices are generally undertaken maliciously in an attempt to get the data to 'say' what you want. Understandably, such practices are seriously frowned upon within academia. If your project is an assessed piece of work, the detection of such practices may well lead to a poor mark and depending upon the rules of the institution, disqualification. Remember that, unless your data are highly confidential, in general researchers are meant to share data upon request so that the results can be verified.

Misinterpreting evidence is not a deliberate attempt to fabricate the results of a study. It is quite easy to get the 'wrong end of the stick' with some data. Corroborating evidence concerns the cross-checking of conclusions to try to avoid 'genuine' errors in analysis and interpretation. One of the main criticisms of qualitative data analysis is that it is subjective, relying on the ability of the researcher to make subjective judgements concerning categorisation, to place value on and interpret data, and to think laterally. Corroboration is aimed at avoiding some of these criticisms by strengthening the claims made from qualitative data; it is concerned with integrity and validity. There are two main ways to corroborate your conclusions (see Box 8.19). The first is to try to think of possible alternative conclusions and then check whether these are more likely or valid. The second is to check the quality of the data and to compare the conclusions to those drawn from other studies. Both of these strategies should be undertaken before you write up your results. It is important that you are confident about the validity of your claims and that you are prepared to stand by your conclusions.

So far we have concerned ourselves with analysing qualitative data through interpretative techniques. We can, however, also analyse some aspects of qualitative data using quantitative techniques. This necessarily involves the conversion of the qualitative data into a numeric format. This conversion can take the form of counts and tallies and will be nominal or ordinal in character (see Section 4.7). Once in a numeric format we could then apply statistical tests to describe and compare data (see Chapter 5). For example, one of us (Kitchin, 1997) has used this approach to help analyse 'talk-aloud protocol' data. Talk-aloud protocols are where respondents detail what they are doing as they do it. In our case, respondents described verbally what they were thinking about and doing while trying to complete various tests designed to measure their cognitive map knowledge of the Swansea area. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using the strategy detailed in this chapter. Eight different strategies of spatial thought (ways to think about geographical concepts) were identified. These results were then mapped into matrices (see Tables 8.2 and

8.3). An ANOVA test (see Chapter 5) was then used to determine if there was a relationship between the common strategies of spatial thought adopted and the quantitative results. The ANOVA tests indicated that the adoption of certain strategies of thought did not lead to more accurate results on any of the tests (projective convergence test, F = 0.55, p = 0.791; orientation specification test, F = 0.40, p = 0.804). In addition, the number of strategies adopted by respondents does not differ across the tests, that is, certain tests do not increase the likelihood of adopting more strategies of thought (one-sample chi-square test, χ2 = 2.97, p < 0.95). It was clear from the AN OVA tests that respondents adopt a range of common strategies, but that these strategies are equally likely to provide a solution to the task set.

Depending upon your point of view, analysing qualitative data quantitatively can be a useful tool in determining the similarity or difference between data. Of course, some qualitative researchers would suggest that such an approach reduces the richness of the data to just numbers. Others would argue that, although this richness is not lost, as it is still used to illustrate why data sets differ or are similar, quantitative data just add a certain degree of confidence to interpretative findings. While we ourselves are happy to analyse qualitative data quantitatively, it is really up to you to decide whether you agree with such an approach.

After reading this chapter you should:

In this chapter we have presented a prescriptive approach to analysing qualitative data. We divided our discussion into a number of related themes centred around description, classification and connection. By following the prescription of transcribing and annotating your data, categorising the data, splitting and splicing categories where necessary, linking and connecting data, and corroborating evidence, you should ensure that your data have been rigorously examined. Where appropriate, quantitative analysis of qualitative data should be considered. Each step within the process needs to be carefully executed to ensure validity when interpreting the findings. In the following chapter we describe how to perform the same analysis using NUD-IST, a computer package specifically designed to aid qualitative data analysis.

Dey, I. (1993) Qualitative Data Analysis: A User Friendly Guide for Social Scientists. Routledge, London.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1992) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage, London.

Patton, M. (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd edition. Sage, London.

Silverman, D. (1993) Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. Sage, London.