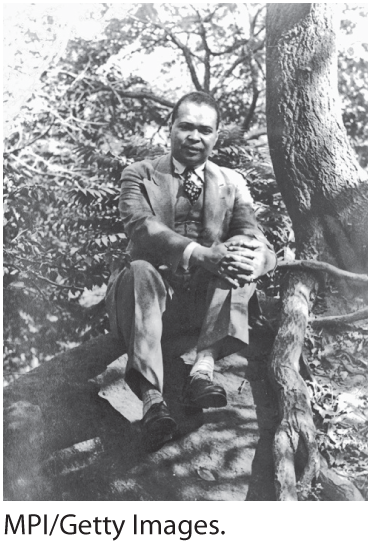

Countee Cullen (1903–1946)

Little is known about Countee Cullen’s early life. Although he claimed to have been born in New York City, various sources who were close to him have alternately indicated that he was born in Louisville, Kentucky, or Baltimore, Maryland. In any case, Cullen, always a private person, never definitively resolved the question. Raised by his paternal grandmother as Countee Porter, Cullen was apparently adopted by the Reverend Frederick A. Cullen after she died when he was around fifteen. Reverend Cullen was an activist pastor of the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church, which was home to a large congregation in Harlem. He eventually became head of the Harlem chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, so Cullen found himself living at one of the focal points of the black cultural and political movements near the very beginning of the Harlem Renaissance.

Cullen published his first book of poems, Color, in 1925, the year he graduated from New York University. This edition included a number of what were to become his major poems, some of which were simultaneously featured in Alain Locke’s The New Negro. This remarkable success transformed an extraordinarily talented student into an important poet whose literary reputation was celebrated nationally as well as in Harlem. In 1926, he earned a master’s degree in English and French from Harvard and subsequently began writing a column for Opportunity, the publication of the National Urban League, in which he articulated his ideas about literature and race. After publishing two more volumes of poetry in 1927, Copper Sun and The Ballad of the Brown Girl, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship to write poetry in France, one of many literary prizes he was awarded. His fourth collection of poetry, The Black Christ and Other Poems, appeared in 1929. Having achieved all of this, he was only twenty-six years old.

By the end of the decade, Cullen was considered a major poet of the black experience in America. Owing to his early interest in Romantic writers — John Keats was a favorite inspiration — he was also read for his treatment of traditional themes concerning love, beauty, and mutability. As he made clear in his 1927 anthology of verse showcasing black poets, he was more interested in being part of “an anthology of verse by Negro poets, rather than an anthology of Negro verse.” In a poem titled “To John Keats, Poet, at Spring Time (1925),” he pledges his allegiance to a Romantic poetic tradition; consider this excerpt:

“John Keats is dead,” they say, but I

Who hear your full insistent cry

In bud and blossom, leaf and tree,

Know John Keats still writes poetry.

Though Cullen habitually wrote about race consciousness and issues related to being black in an often-hostile world, he insisted on being recognized for his credentials as a poet rather than for his race, and he did so writing in traditional English forms such as the sonnet and other closed forms that he had studied in college and graduate school. He was critical of the free verse that writers like Langston Hughes coupled with the blues and jazz rhythms, as they moved away from conventional rhyme and meter (see the Perspective “On Racial Poetry” by Cullen). Refusing to be limited by racial themes, he believed that other blacks who allowed such limitations in their work did so to their artistic disadvantage. The result was that his poetry was popular among whites as well as blacks in the 1920s.

As meteoric and brilliant as Cullen’s early writing career had been, it faded almost as quickly in the 1930s. Despite publication of a satiric novel, One Way to Heaven (1932); The Media and Some Poems (1935); two books for juveniles in the early 1940s; and several dramatic and musical adaptations, his reputation steadily declined as critics began to perceive him as written out, old-fashioned, and out of touch with contemporary racial issues and the realities of black life in America. His conservative taste in conventional poetic forms was sometimes equated with staunch conservative politics. There can be no question, however, that his most successful poems are firmly based in an awareness of the social injustice produced by racism. Cullen was offered a number of opportunities teaching at the college level, but his overall influence waned as he chose in 1934 to teach French and creative writing at Frederick Douglass Junior High School in Harlem, where he worked until his poor health resulted in an early death in 1946.