Memory is used in almost any everyday activity. But as soon as we learn something, we immediately start to forget it.

Ah, memory. I (Yana) am feeling dreamy as I type this, because memory is my greatest love. Memory is the reason why I’m a cognitive psychologist. Both of us (Yana and Megan) are passionate about memory, and have dedicated most of our adult lives so far to examining how our human memory works. But why?

Well, think about your life. Think about how you define yourself, who you are. Maybe you see yourself as a hard worker. That might be because for many years you have proven yourself through working hard, and you remember working hard a lot.

Maybe you think of yourself as a parent. That conjures up memories of your child’s birth, or adoption, or first bruise that you blamed yourself for, or first day at school when you couldn’t believe they were already that old.

Maybe you think of yourself as kind and helpful to others, and immediately remember that time you drove over to your best friend’s house in the middle of the night to deal with an emergency.

Your very identity is most likely full of things you remember yourself doing. Maybe you also have an identity that is aspirational, partly projected into the future, full of lofty goals – “I will get my bachelor’s degree,” “I will start my own business,” “I will retire and live in Florida” – but what do we do when we imagine this future? There has been a flurry of research into “future mental time-travel,” and the leading theory is that it involves more or less the same processes as remembering (Szpunar, Watson, & McDermott, 2007). What we’re actually doing when we’re envisaging our future might involve taking bits and pieces of things we’ve experienced – be it in our own lives, in books, or in movies – and splicing them together to form a new imagined situation (Botzung, Denkova, & Manning, 2008).

But our self-concept is not the only thing we need our memory for. Actually, we would argue that everything you do requires memory in some form or another.

Everything you do requires memory in some form or another.

That might seem like an extreme statement, but here are some examples. Note that these are just a few specific examples, and in no way do they encompass all of the ways in which we rely on memory!

And yet, despite this rich variety of functions, memory has recently come under fire. Some claim that now that we have the internet, we no longer need to worry about memory. While there’s a lot of hype about the internet replacing our memory, humans have actually been relying on external memory systems for years. Books contain a wealth of information and have been around for centuries, and we’ve been writing memos for ourselves (notes, lists, and reminders) for many, many generations; one does not need to be a “digital native” in order to use external memory resources adaptively (Loh & Kanai, 2016).

Having said that, a fascinating line of research is now examining the cognitive consequences to these behaviors, called “cognitive offloading” (Risko & Gilbert, 2016). For example, one set of studies showed that in some situations, we are more likely to forget something we took a picture of than something we just looked at (Henkel, 2014).

We recently came across the following question, which alludes to the declining importance of human memory: “Ask yourself, why don’t I just use my computer?” The answer to that question should be obvious: because you can’t use a computer without using your memory first. We might be adapting from remembering information to remembering how to obtain that information from external sources (Sparrow, Liu, & Wegner, 2011) – but that still requires memory!

So, if almost everything we do requires memory, then most certainly this is going to be an important concept to understand with regards to learning. With that in mind, let’s take a look at what is currently known about memory.

Memory is not like a library (or a computer); memory is reconstructive.

Early on, before cognitive psychologists started researching the processes involved, memory was often described with a “library” analogy. This is the idea that memories are put down in our minds as though they were written down in books and stored away neatly in organized locations. If we wanted to retrieve a memory, we would go down the relevant aisle and select the appropriate book. If we can’t quite retrieve the memory, the words printed in the books may have faded with time, and if we can’t find the memory at the specified location, perhaps it was like a library book getting misplaced.

But many studies have shown that this is not at all the way memory functions. We don’t lay down objective, definitive memory traces that are later retrieved verbatim. Instead, memory is reconstructive (Schacter, 2015).

We speak of storing memories, of searching for and locating them. We organize our thoughts; we look for memories that have been lost, and if we are fortunate, we find them. (1980, p. 232)

We speak of storing memories, of searching for and locating them. We organize our thoughts; we look for memories that have been lost, and if we are fortunate, we find them. (1980, p. 232)

Henry Roediger

We don’t lay down objective, definitive memory traces that are later retrieved verbatim.

This is a key concept in long-term memory: the idea that every time you retrieve a memory, you are actually changing it.

Every time you tell the same story, it comes out a little more polished, with a few embellishing details added, or a few boring ones removed. The memory itself – not just the story – is changing, so that the next time you retrieve the memory of that event, it will be more like the story you last told, rather than the way it really was. Memory is reconstructive in nature, and every time a memory is activated, it is altered.

Every time you retrieve a memory, you reconstruct it, activate it, and may alter it.

Here’s a concrete example of memory reconstruction, first demonstrated almost 100 years ago (Bartlett, 1995 [1932]).

In this demonstration, one person was shown an ambiguous drawing (in the top left of the picture). This person was then asked to try to reproduce the drawing from memory. Because we like to classify things into categories rather than dealing with unknown objects (Smith & Medin, 1981), the person who was trying to draw the ambiguous original drawing from memory drew it to look kind of like an owl. Their drawing was then shown to another person, who again was asked to reproduce it from memory, and this cycle continued. As you can see, the drawing gradually evolved from an owl to a cat! Each time someone re-drew the picture from memory, they changed it, and eventually even the animal itself changed.

The fact that memory is reconstructive necessarily means that memory is not objective. Our memories are a lot more approximate and less accurate than you might like to believe. In particular, we are prone to having “false” memories – these are memories of things that never happened or happened quite differently to the way we remember them (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). In addition, since we see the world through our own unique filter – our world view – we tend to remember things in a way that fits our “schema,” or pre-determined categorizations of the world and how objects and people behave (Tversky & Marsh, 2000).

The idea that we can have memories that are “false” gained credibility starting in the 1970s and was a topic of hot debate for decades after that. The leader of this field is Dr. Elizabeth Loftus, who demonstrated that eyewitness testimony can be inadvertently affected by information encountered after the event (“misleading post-event information”). Imagine you are a witness to a crime. It was dark, but you think you saw a tall man in a mask, holding something in his hand. After this event, you are questioned repeatedly by the police, and you also discuss the event over and over with your friend who was standing next to you when this happened.

The fact that memory is reconstructive necessarily means that memory is not objective.

Elizabeth Loftus revolutionized our understanding of how eyewitness testimony works. She demonstrated in numerous experiments that by the time you’ve had all those conversations with the police and your friend, your memory of the crime in the above story will have become a mixture of (a) what you actually saw, (b) what you told people you saw, and (c) what other people told you they saw or think you should have seen.

Memory works a little bit more like a Wikipedia page: You can go in there and change it, but so can other people. (2013, TEDGlobal)

Memory works a little bit more like a Wikipedia page: You can go in there and change it, but so can other people. (2013, TEDGlobal)

Elizabeth Loftus

So, for instance, if you were asked over and over about a weapon, you might come to imagine one and believe that the suspect really was carrying a weapon, even if your original memory of the event did not include a weapon. The details from your imagination will become part of the new memory for the event.

Similar reconstructive memory effects can also occur in an educational context. Often, we will remember the information itself along with the source it came from. But, according to the Source Monitoring Framework (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993), it is possible to misattribute memories to incorrect sources. For example, if your friend tells you something, you later might believe you heard it from your teacher, or another reliable source.

Details from your imagination can become part of your memories.

I (Megan) have a false or distorted memory of burning my hand when I was a child. It did happen, but I do not remember it accurately: I picture it in the house I grew up in and remember, whereas this actually happened in the house we lived in up until I was four, and I can’t remember that house at all.

Even details from our dreams can make it into our memories of real-life events (Johnson, Kahan, & Raye, 1984). When I was 11, I (Yana) once dreamed that my chamber music lesson was canceled, and didn’t bring my music to school that day because I had confused the dream with real life. I am not sure my teacher believed my excuse at the time.

So, we have seen that recalling information in a reconstructive way can potentially introduce errors. On the other hand, understanding that memories are reconstructed each time we retrieve them is important as it underpins some of the strategies we discuss in Part 3 of the book. In particular, recalling information correctly actually strengthens memory (see Chapter 10).

Aside from being reconstructive and subjective, memory is also not a unitary process. Instead, multiple processes are thought to make up the rich experience that we call memory. In a guest post on our blog, James Mannion (2016) discussed various dichotomies and distinctions that frequently come up in memory research, but here we focus on two that are particularly relevant to education.

Multiple processes are thought to make up the rich experience that we call memory.

Have you heard people referring to how they can never find stuff they’ve left around the house, and following this with “my short-term memory is really bad”? That would be a scientifically inaccurate use of that term. When cognitive psychologists talk about short-term memory, they are really just talking about a very brief (roughly 15–30 seconds) period of time. The reason why cognitive psychologists believe that there is something truly special about the 15–30 second range that can be separated from all other memory beyond that time frame is that patients who present with apparently total memory loss are still able to keep things in memory for 15–30 seconds.

William James wrote a book in 1890 – Principles of Psychology – which, unlike cognitive psychology, was based entirely on his own intuitions – or, more formally, introspections – rather than experiments and data. Even before any data were gathered to support the idea of a distinction between short- and long-term memory, William James proposed it – although he referred to the two types of memory as primary memory (things that you are holding in your memory right now) and secondary memory (everything else, stuff that you remember for longer than just in the moment).

When cognitive psychologists talk about short-term memory, they are talking about a very brief (15–30 seconds) period of time.

The first patient to demonstrate a profound loss of long-term memory along with perfectly intact short-term memory was called H.M. He was treated for epilepsy when he was in his 20s; since this was the 1950s and they didn’t know any better, the doctors removed part of his brain as an attempt to cure him of his seizures. This did result in improvement in terms of epilepsy, but with huge consequences: H.M. also lost the ability to form new long-term memories – at least, those that he could report (i.e., declarative memories). For the 40 years that he lived after his surgery, he didn’t form any meaningful new memories about his life.

If asked what he ate for breakfast that day, H.M. didn’t know, and if asked when he started suffering from memory loss (yes, he knew that something was wrong), he would say maybe a year ago, regardless of how many decades had passed. Each time he saw the researcher that would test him probably at least once a week for those 40 years, he introduced himself anew.

This is all to say that despite how severely his long-term memory was affected, his short-term memory remained just as good as mine, or yours. That is, if you read out a phone number to H.M., he could repeat it back to you just as well as the next person. This also explains why H.M. was actually able to hold relatively normal-seeming conversations, as long as the subject did not extend beyond the present situation.

H.M. died in 2008, and the researcher who had studied him for his entire post-operative life has published a book about him. In this book, Corkin describes memory as if it were a hotel, with short-term memory represented by the lobby, and long-term memory represented by the guest rooms.

Information passes through short-term memory, but it doesn’t stay for long, and there’s a limit to the amount of information that can fit in.

Here is what Corkin says about H.M.:

The information could be collected in the hotel lobby of Henry’s brain, but it could not check into the rooms. (2013, p. 53)

The information could be collected in the hotel lobby of Henry’s brain, but it could not check into the rooms. (2013, p. 53)

Suzanne Corkin

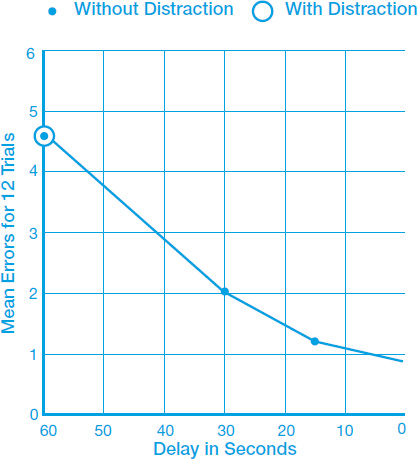

To illustrate how sensitive H.M.’s memory is to this distinction between short- (15–30 seconds) and long-term memory, consider the following experiment (Prisko, 1963). H.M. was shown two shapes, one after the other, and his job was to indicate whether the shapes were the same, or different. The length of time between presentation of the two shapes varied between 15 and 60 seconds. Here are examples of same and different shape pairs:

We will first describe how control participants (i.e., those without memory loss) would perform on this task. Imagine that there are 12 trials in the experiment: six where the pairs are the same, and six where they are different. If you were randomly guessing, you might expect to get about half of them correct. A typical adult will only get on average one of the 12 trials wrong (getting 11/12 correct) when the first and second shapes are presented 60 seconds apart.

Now, what about H.M.? His data appear on the graph below.

The dot to the far right, above the 0, demonstrates that when the shapes were presented at the same time (as they are in the example above!), H.M. was pretty good at determining whether they were the same or different. He only made one error in 12 trials. When the shapes were presented 15 seconds apart, he was still pretty good at the task (the mean error displayed on the graph is between one and two trials, because these data were aggregated across five different versions of the task).

But once the delay was increased beyond 30 seconds, there was a sharp rise in the number of errors H.M. made, and by the time the delay was 60 seconds, it was as if he was randomly guessing. Recall that the average normal participant only makes one error when the shapes are 60 seconds apart; this is not a difficult task. What this shows is that while H.M. could keep the first shape in his memory for about 15–30 seconds, beyond that the memory faded away, and he was no longer able to compare it to the second shape and make an accurate decision about whether they were the same or different.

The kind of memory that we usually think of when we talk about memory in everyday life is declarative memory. This refers to memories that we can directly access, voluntarily report the contents of, and are aware of remembering. After his operation, H.M. wasn’t able to do many of the things we described at the beginning of the chapter: learning a new person’s name, remembering whether he had taken a pill, or where he had placed an object.

However, it is not exactly accurate to say that H.M. was unable to form long-term memories. In fact, H.M. did have a partially intact long-term memory! This is evidenced by the fact that he was able to learn to use a walker, able to do the myriad cognitive tasks that researchers subjected him to for decades, and more generally, able to rely on his memory as long as he was not explicitly asked to report its contents (Corkin, 2013).

Procedural memory is demonstrated in your actions, and does not involve directly reporting the contents of one’s memory. Examples of procedural memory include things that you can do without thinking about how to do them, such as walking; and things you can do without being able to explain how you did them, such as finding your way home from a certain location without being able to tell me the directions. H.M. still had access to this memory process after his operation.

The following task cleverly demonstrates the difference between procedural and declarative memory. In the first version of the task, H.M. would be shown a list of words, such as CLAY, CALCIUM, ROUGH, etc. Then (at least 30 seconds later, once short-term memory had been cleared, because – remember – he had an intact short-term memory), he would be presented with “word stems.” These word stems were the first three letters of each studied word, such as “CLA-,“ “CAL-,“ and “ROU-.“ His job was to complete the word stems with words he had just seen.

Note that these instructions described above explicitly referred H.M. back to the study phase of the experiment. H.M. performed very poorly on this task, because it required him to report on the contents of his memory.

In the procedural version of the task, everything was exactly the same except the test instructions. This time, instead of being asked to complete the word stems with previously studied words, H.M. was simply asked to come up with any random word that started with those letters. Now, all of a sudden, he performed like a healthy control participant: he was much more likely to complete the word stems with words he had studied than other (unstudied) words that could fit, even though he had no awareness that he was actually relying on his memory to perform this task.

In order for memory to be recallable later, it needs to go from short-term to long-term memory (checking into the hotel, in Corkin’s analogy above). Whether something makes it from short- to long-term memory depends on a number of factors, some of which may not yet have been pinned down. However, a very important factor is whether information is encoded in a deep or meaningful way (Craik & Lockhart, 1972), so that connections can be made and understanding can be achieved. In Chapter 9, we discuss why making connections and achieving understanding is so important to learning.

Long-term memory is often talked about in terms of a four-stage model: encoding, consolidation, storage, and retrieval (Nader & Hardt, 2009). If a memory is never encoded, then it was never created in the first place, so there is nothing to retrieve (for example, imagine holding a piece of paper with a string of numbers on it right in front of your face, but with your eyes completely shut the whole time the paper is in front of you).

Just because a memory is encoded, however, does not mean that it will be recallable later; it needs to be consolidated. And, consolidation of a memory is not a one-off event. When the memory is retrieved, it is reconstructed, reactivated, and re-consolidated (Sara, 2000).

As we discussed in Chapter 2, the majority of this book is focused on understanding learning on a cognitive level – that is, how learning takes place in the mind, rather than pin-pointing specific biological processes in the brain that lead to learning. However, I (Yana) recently had coffee with Efrat Furst, who was trained as a cognitive neuroscientist, and now translates this research for educators.

In Furst’s opinion, there are some basics that all learners and teachers should understand about how memory functions – not just on the cognitive level, but also on the neuroscientific level. Current research is moving us closer and closer to connecting these levels (Hardt, Einarsson, & Nader, 2010), though it’s important to note that for now, these two levels are not completely integrated (Coltheart, 2006).

From a neuroscientific perspective, memory is everything that one has ever experienced and is represented in the neuronal networks of the brain: simple or complex, conscious or unconscious, facts, events, procedures, and so on. In educational contexts, however, memory is sometimes disregarded as “just memory” in contrast to other, more sophisticated forms of knowledge. But for brain scientists, there are no other forms of knowledge: everything that is learned is memory. The important questions to ask are “how is memory represented?” and” how might this influence future behavior?” Our unique and enormous long-term memory store is what makes each of us an individual. However, the principles of how memory is stored in the brain are common among us all, and therefore valuable to everyone – and to educators in particular.

Here are the basic neuroscientific principles, as they are currently understood, that guide my thinking about learning and memory:

Putting it all together (and extending the scientific findings to create a full picture): it is crucial to remember that construction and reconstruction processes are dependent on simultaneous activity: neurons that “fire together wire together” (e.g. Hebb, 1949; Tse et al., 2007). When we learn a new concept, its retention depends on constructing the engram and on forming associations with existing engrams. This, in turn, depends on our ability to retrieve the existing engrams and create the connections actively when learning.

These principles are valuable as a basis for considering several strategies that are known to be effective for learning, on the basis of work from the cognitive sciences. In a way, the neuroscientific evidence allows us to think more concretely about the possible underlying mechanisms and understand the benefits of spacing out practice (Chapter 8), creating meaningful connections between new and prior knowledge (Chapter 9), and retrieving prior knowledge (Chapter 10). These strategies allow new information to be integrated with retrieved prior knowledge, and then consolidated. This effortful reconstruction process is the key to an effective learning experience.

Arguably, one of the most important features of memory is actually the opposite of remembering: forgetting. This fundamental concept has been explored for well over 100 years (first starting with Ebbinghaus (1913), whom you will encounter in Chapter 8), yet researchers have still not reached a consensus on the exact definition of the term.

An extreme form of forgetting would be the total obliteration of any memory trace; no evidence of this pure form of forgetting has yet been found (Davis, 2008). More realistically, we might think about forgetting as the inability to remember something that you once knew (Tulving, 1974).

Have you ever studied something – for example, learned some vocabulary in a foreign language – and reached a certain level of proficiency, only to find yourself completely incapable of remembering the words you thought you had once mastered? What has happened to this knowledge that you had before? You might say that you have “forgotten” it – but what does that really mean?

What you are experiencing is an inability to retrieve information after it was once learned – in other words, a retrieval failure. As such, we should be able to overcome retrieval failure by providing hints or “retrieval cues.” Tulving and Pearlstone (1966) demonstrated the effectiveness of providing hints by having participants try to remember a list of 48 words – two words from each of 24 categories, such as “articles of clothing: blouse, sweater” and “types of birds: blue jay, parakeet.” On the later test, participants were either just asked to write down as many words as they could remember, or they were provided with hints or cues in the form of the category names (e.g., “articles of clothing: ?). Providing these retrieval cues increased memory output from 40 percent of the words to 75 percent, suggesting that most of the words that appeared to be “forgotten” could still be retrieved with additional cues.

One thing we do know about forgetting is that it starts immediately after encoding, and happens quite rapidly before slowing down.

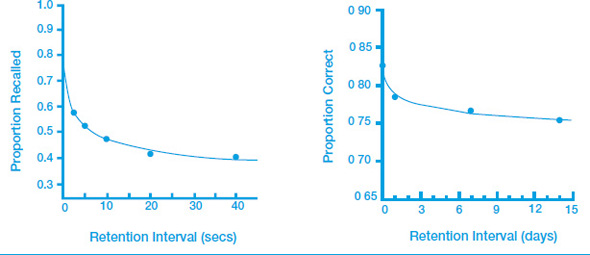

The graphs on the following page, often called “forgetting curves,” demonstrate how much information is retained when people are tested on it at different amounts of time post-learning (technically, these are actually retention curves as they show the amount of information decreasing; see Roediger, Weinstein, & Agarwal, 2010). Regardless of what window of time we are interested in, the forgetting function is always going to look similar. On the following page you will find two examples of “forgetting curves” from different time frames.

As soon as you encode something, you immediately start to forget it.

The rest of this book is dedicated to mitigating against forgetting in an academic context. In Chapter 8, we will learn about how to space studying over time in order to interrupt the steep forgetting curve. In Chapter 9, we will discuss how to deepen understanding, which is essential for learning. And finally, in Chapter 10 we will discuss how bringing information to mind from memory can stimulate the re-consolidation process and strengthen learning

Early on, before cognitive psychologists started researching the processes involved, memory was often described with a “library” analogy. This is the idea that memories are put down in our minds as though they were written down in books, and stored away neatly in organized locations. If we wanted to retrieve a memory, we would go down the relevant aisle and select the appropriate book. If we can’t quite retrieve the memory, the words printed in the books may have faded with time, and if we can’t find the memory at the specified location, perhaps it was like a library book getting misplaced. But is this analogy a good one? In this chapter, we discuss how human memory really works, and why this is important for teachers to know.

These graphs represent the proportion of information retained either over the course of 40 seconds (word recall) or two weeks (face recognition). Based on Experiments 1 and 2 of Wixted and Ebbesen (1991).

Bahrick, H. P., Bahrick, P. O., & Wittlinger, R. P. (1975). Fifty years of memory for names and faces: A cross-sectional approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104, 54–75.

Bartlett, F. C. (1995 [1932]). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Botzung, A., Denkova, E., & Manning, L. (2008). Experiencing past and future personal events: Functional neuroimaging evidence on the neural bases of mental time travel. Brain and Cognition, 66, 202–212.

Brandimonte, M., Einstein, G. O., & McDaniel, M. A. (Eds.) (1996). Prospective memory: Theory and applications, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Coltheart, M. (2006). What has functional neuroimaging told us about the mind (so far)? Cortex, 42, 323–331.

Corkin, S. (2013). Permanent present tense: The unforgettable life of the amnesic patient, H.M. New York: Basic Books.

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671–684.

da Costa Pinto, A. A. N., & Baddeley, A. D. (1991). Where did you park your car? Analysis of a naturalistic long-term recency effect. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 3, 297–313.

Daneman, M., & Merikle, P. M. (1996). Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 422–433.

Davis, M. (2008). Forgetting: Once again, it’s all about representations. Science of Memory: Concepts, 317–320.

Dudai, Y. (2004). The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu. Rev. Psychol., 55, 51–86.

Dudai, Y., Karni, A., & Born, J. (2015). The consolidation and transformation of memory. Neuron, 88, 20–32.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (No. 3). University Microfilms.

Gabrieli, J. D., Milberg, W., Keane, M. M., & Corkin, S. (1990). Intact priming of patterns despite impaired memory. Neuropsychologia, 28, 417–427.

Gilboa, A., & Marlatte, H. (2017). Neurobiology of schemas and schema-mediated memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21, 618–631.

Hardt, O., Einarsson, E. Ö., & Nader, K. (2010). A bridge over troubled water: Reconsolidation as a link between cognitive and neuroscientific memory research traditions. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 141–167.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behavior. New York: Wiley.

Henkel, L. A. (2014). Point-and-shoot memories: The influence of taking photos on memory for a museum tour. Psychological Science, 25, 396–402.

Insel, K., Morrow, D., Brewer, B., & Figueredo, A. (2006). Executive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, 102–107.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 1). New York: Holt.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28.

Johnson, M. K., Kahan, T. L., & Raye, C. L. (1984). Dreams and reality monitoring. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 329–344.

Leahy, W., & Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory, modality of presentation and the transient information effect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 943–951.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 720–725.

Loh, K. K., & Kanai, R. (2016). How has the Internet reshaped human cognition? The Neuroscientist, 22, 506–520.

Mannion, J. (2016, December). GUEST POST: Learning is multidimensional — Embrace the complexity! The Learning Scientists. Retrieved from www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/12/6-1

Nader, K., & Hardt, O. (2009). A single standard for memory: The case for reconsolidation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10, 224–234.

Prisko, L. H. (1963). Short-term memory in focal cerebral damage, PhD Thesis, McGill University, Quebec. Canada.

Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20, 676–688.

Roediger, H. L. (1980). Memory metaphors in cognitive psychology. Memory & Cognition, 8, 231–246.

Roediger, H. L., Weinstein, Y., & Agarwal, P. K. (2010). Forgetting: Preliminary considerations. In S. Della Sala, (Ed.), Forgetting (pp. 1–34). Brighton, U.K.: Psychology Press.

Sara, S. J. (2000). Retrieval and reconsolidation: Toward a neurobiology of remembering. Learning & Memory, 7, 73–84.

Schacter, D. L. (2015). Memory: An adaptive constructive process. In D. Nikulin (Ed.), Memory in recollection of itself. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, E. E., & Medin, D. L. (1981). Categories and concepts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776–778.

Squire, L. R. (1987). Memory and brain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Szpunar, K. K., Watson, J. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2007). Neural substrates of envisioning the future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 642–647.

TED. (2013, June 11). Elizabeth Loftus: The fiction of memory [Video file]. Retrieved from: https://protect-us.mimecast.com/s/J6-7COYEZrupwqnMpsELrWz?domain=blog.ted.com” https://blog.ted.com/tk-elizabeth-loftus-at-tedglobal-2013/

Tonegawa, S., Liu, X., Ramirez, S., & Redondo, R. (2015). Memory engram cells have come of age. Neuron, 87, 918–931.

Tse, D., Langston, R. F., Kakeyama, M., Bethus, I., Spooner, P. A., Wood, E. R., ... & Morris, R. G. (2007). Schemas and memory consolidation. Science, 316(5821), 76–82.

Tulving, E. (1974). Cue-dependent forgetting: When we forget something we once knew, it does not necessarily mean that the memory trace has been lost; it may only be inaccessible. American Scientist, 62, 74–82.

Tulving, E., & Pearlstone, Z. (1966). Availability versus accessibility of information in memory for words. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5, 381–391.

Tversky, B., & Marsh, E. J. (2000). Biased retellings of events yield biased memories. Cognitive Psychology, 40, 1–38.

Wixted, J. T., & Ebbesen, E. B. (1991). On the form of forgetting. Psychological Science, 2, 409–415.