A productive system can be fancifully described as a huge box: certain things flow in one side and other things flow out the other side. What flows in, we call input, and what flows out, we call output.

Input is made up of heterogeneous elements called factors of production. Traditionally economists group the innumerable and heterogeneous factors of production under three broad headings, called, respectively, labor, capital, and natural resources (the last category including land as well as water supply, iron ore, coal deposits, and so forth). Like most classifications, the tripartition is arbitrary and oversimplifies matters, but as it has proven useful for analytical purposes, we adopt it in the historical analysis below. However, it is essential to sound a warning.

One of the major difficulties in historical reconstruction is that, in order to express ourselves, we must make use of the current language. Unfortunately, the words we use daily evoke in our minds pictures of the contemporary world. Expressions such as labor and capital automatically evoke in our minds the picture of the factory, with its high concentration of managers, wage laborers, and complex machinery. An effort of the imagination is required to recapture, behind the modern spoken expression, the very different reality of the past. In this attempt, one must be careful not to go to the other extreme, to fall victim to stereotyped, fanciful typologies.

The factory in the modern sense did not exist; instead there was the small workshop. The equivalent of the modern businessman was the merchant, but he was not what we now mean by the word merchant. Specialization had not yet developed to the degree that characterizes industrial societies, and a merchant was very often the head of a manufacturing enterprise, a money lender, and a trader, all at the same time. As a trader he generally dealt in a variety of products, in cloths as well as spices, cereals as well as metals. Even the distinction between wholesale and retail trade did not exist. The one recognizable difference among merchants was that some operated on an international scale with substantial capital, while others were petty, local merchants of limited means and horizons.

Similarly, for the term labor we must try to recapture a different reality from that which we associate with the term today. Wage labor did exist in preindustrial Europe, but it was not as preponderant as in the modern world. In agriculture, sharecropping was quite common and in most parts of Europe it was the predominant form of compensating agricultural labor. As for the manufacturing sector, all textbooks emphasize that, before the Industrial Revolution, the artisan was the most common type of worker. This is true, but the artisan was far from being a stereotype. There were many craftsmen who worked with the help of an apprentice. There were workshops with a number of artisans joined in a company. And there were even more complex units in which craftsmen actually employed both wage-earners and apprentices and, we can now see, functioned as proto-capitalists.

All members of a population are consumers, but not all of them are producers. Apart from parasites and the infirm, the youngest and oldest members of a population consume but do not produce. In any society, once population totals have been established, it is important to identify (a) the economically active population (those who produce and consume), (b) the dependent population (those who consume but do not produce), and (c) the relation between the two (dependency ratio).1

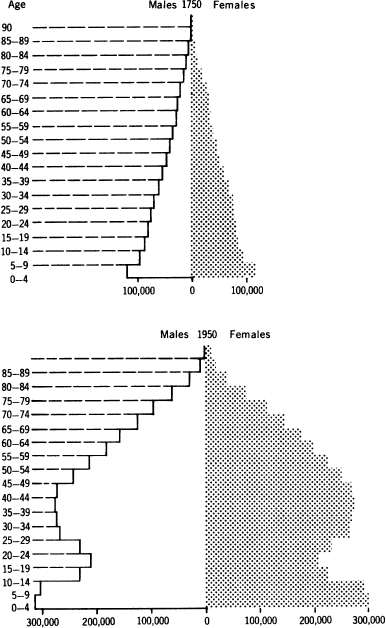

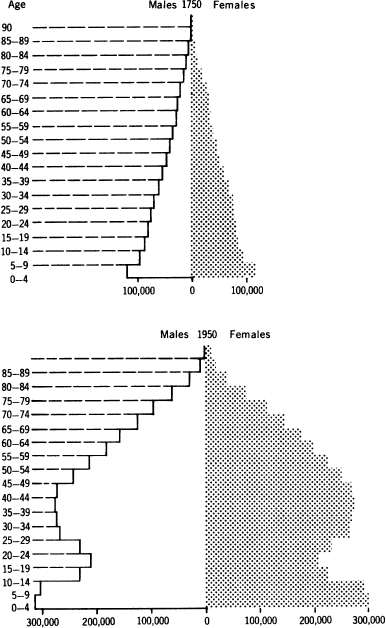

Prevailing birth and death rates and, in cases of significant migratory movements, immigration and emigration, determine the age structure of a given population. Preindustrial European societies were characterized by high fertility and high mortality rates. Consequently, the so-called age pyramid of European preindustrial populations normally presents a relatively wide base as against an acutely angled apex (see Figure 2.1). Consider the structure of two populations when both were at a preindustrial stage, namely, the Swedish population in the second half of the eighteenth century and the Italian population soon after the middle of the nineteenth century – the one Nordic and Protestant, the other Mediterranean and Catholic. The percentage distribution of the two populations divided into broad age groups is shown in Table 2.1.

Despite wide differences in latitude, climate, color of eyes and hair, food, religion, and culture, in both cases the population in the fifteen to sixty-four age group represented little more than 60 percent of the total while the group under age fifteen made up almost a third. Before the nineteenth century, national censuses were not taken in Italy but data available on the population of various Italian cities confirm that the population under fifteen years of age always made up a third or more of the total population (see Table 2.2).

Before proceeding, it may be useful to make a comparison with the structure of industrial populations. Table 2.3 contains data relating to the Swedish and English populations in 1950–51. As one can see, in an industrialized society, the population in the fifteen to sixty-four age group represents about two-thirds of the total population, that is, little more than in the preindustrial society. The most striking difference between the societies of preindustrial Europe and those of contemporary Europe lies in the composition of the dependent population. While in modern Europe children of zero to fourteen years make up from 65 to 70 percent of the dependent population, in preindustrial Europe they represented about 90 percent. In other words, the burden of dependence in preindustrial Europe was almost totally represented by children. The gravity of the problem is measured by the number of abandoned children.

Figure 2.1 Age and sex structure of the population of Sweden in 1750 and 1950.

Source: Historisk Statistik för Sverige, Stockholm, 1955, vol. 1, Appendix fig. 4 (1750) and fig. 5 (1950).

Table 2.1 Percentage age distribution of two preindustrial populations, Sweden (1750) and Italy (1861)

| Age groups | Sweden 1750 % | Italy 1861 % |

| 65 and over | 6 | 4 |

| 15–64 | 61 | 62 |

| 0–14 | 33 | 34 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Table 2.2 Adolescents as percentage of total population in selected Italian areas, 1427–1642

| City | Year | Age group | Percent of total population |

| Arezzo and surrounding countryside | 1427–29 | 0–14 | 32 |

| Pistoia and surrounding countryside | 1427–29 | 0–14 | 37 |

| Parma (city) | 1545 | 0–14 | 32 |

| Parma (countryside) | 1545 | 0–14 | 41 |

| Brescia | 1579 | 0–18 | 40 |

| Siena | 1580 | 0–10 | 23 |

| Vicenza | 1585 | 0–15 | 42 |

| Milan | 1610 | 0–9 | 24 |

| Carmagnola | 1621 | 0–15 | 41 |

| Padua | 1634 | 0–15 | 30 |

| Venice | 1642 | 0–18 | 46 |

In Venice in the sixteenth century, the Ospedale della Pietà usually cared for an average of 1,300 foundlings, which, out of a total population of 130,000 to 160,000, represented almost 1 percent.2 In Florence in 1552, in the Ospedale degli Innocenti there were 1,200 foundlings; out of a total population of about 60,000 the foundlings made up 2 percent. In Prato (Italy) in 1630 the Ospedale della Misericordia cared for 128 young girls, 54 boys, and 98 babies, a total of 280 foundlings. Prato then had a population of approximately 17,000, and the foundlings were, therefore, about 1.6 percent of the total population.3 It must be noted that values of the order of 1 or 2 percent of total population meant, in a preindustrial society, some 3 to 7 percent of the children in the age group zero to fourteen. It must also be remembered that the figures above refer in large measure to the number of foundlings who survived. According to a Venetian estimate in the sixteenth century, 80 to 90 percent of the foundlings died in their first year of life.4 If one relates the number of those “admitted to the Ospedale della Pietà” to the number of births in the city, one finds that in Venice, in the second half of the eighteenth century, foundlings represented 8 to 10 percent of all births (see Table 2.4). In Milan at the end of the seventeenth century the number of foundlings was on average 450 per year (Table 2.5), and this figure represented more than 12 percent of the estimated births in the city.5

Table 2.3 Percentage age distribution of two industrial populations, Sweden (1950) and England (1951)

| Age groups | Sweden 1950 % | England 1951 % |

| 65 and over | 10 | 11 |

| 15–64 | 66 | 67 |

| 0–14 | 24 | 22 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Such high percentages must be viewed with caution. We know from various sources that those who wished to rid themselves of newly born babies often came from far away to abandon them in the city. The number of foundlings, therefore, ought to be related to a larger population than the local one. This would lower the percentages mentioned above, but even so, it would be difficult to deny that the practice of abandoning newborn babies was tragically widespread.

In our industrial societies, we consider as economically active the population in the age group fifteen to sixty-four. It is an arbitrary assumption based on the rationales that (a) in many countries compulsory education for the young continues to the age of fifteen and (b) the age of sixty-five is, in many professions, the limit for retirement. In reality, however, there are individuals who start working long after their fifteenth year of age and others who start earlier. There are people who retire before sixty-five and others who are still working at a later age. There are adults who have never worked and there are people who collect a regular salary but whose inclusion among the active population is the result of gentle violence wrought by statistics upon reality. To consider as active all those in an industrial society who fall in the fifteen to sixty-five age group and as dependent all the remainder, probably overestimates the percentage population which is effectively productive and thus underestimates the real dependency ratio. Productivity in industrial societies is so high that it is not difficult for such societies to afford dependency ratios of 50 to 65 percent. In fact, it is high industrial productivity that has allowed the introduction of compulsory education up to fifteen years, allows many to continue their education until the age of twenty-five or twenty-eight, allows most people to retire at sixty-five, and allows many to figure in statistics of active population while doing nothing more than keep their chairs warm.

Table 2.4 Foundlings in Venice, 1756–87

| Foundlings | ||||||

| Year | M | F | MF | No. births | % Foundlings over births |

|

| 1756 | 199 | 210 | 409 | 5246 | 7.8 | |

| 1759 | 204 | 201 | 405 | 5172 | 7.8 | |

| 1765 | 192 | 233 | 425 | 5090 | 8.3 | |

| 1776 | 230 | 248 | 478 | 5243 | 9.1 | |

| 1782 | 229 | 238 | 467 | 5166 | 9.0 | |

| 1783 | 235 | 244 | 479 | 5077 | 9.4 | |

| 1785 | 228 | 233 | 461 | 5074 | 9.1 | |

| 1787 | 231 | 250 | 481 | 5220 | 9.2 | |

Source: Beltrami, Popolazione di Venezia, p. 143, n. 18.

Table 2.5 Foundlings in Milan, 1660–1729

| Decade | M | F | MF |

| 1660–69 | 1967 | 2090 | 4057 |

| 1670–79 | 1802 | 1913 | 3715 |

| 1680–89 | 1774 | 1816 | 3590 |

| 1690–99 | 2616 | 2699 | 5315 |

| 1700–09 | 2697 | 2610 | 5307 |

| 1710–19 | 2479 | 2625 | 5104 |

| 1720–29 | 2250 | 2172 | 4422 |

Source: Buffini, Ospizio dei Trovatelli, vol. 1, Appendix, tables 1 and 2.

The conditions prevailing in preindustrial Europe were vastly different. Those who were economically “active” worked from dawn to dusk, but given the low average of productivity they could not support many dependants. It followed that normally the few old people had to work until the end of their days (which, incidentally, was psychologically good for them), and the young people had to be set to work long before the age of fifteen.

In general, child labor is described as a ghastly by-product of the Industrial Revolution. The truth is that in preindustrial society, children were as widely employed as at the time of the Industrial Revolution. An English royal statute of 1388 mentions the boys and the girls who “use to labor at the plough and cart or other labour or service of husbandry till they be of the age of twelve years.” There was a difference, however. In preindustrial society, the mass of children was employed in the fields and, therefore, only during the summer months (hence the tradition of long school holidays during summer). With the development of the factory system, the children were employed instead the whole year around. Life in the fields was perhaps not so unhealthy as in the factories of the early Industrial Revolution, but the hardships to which children were subjected were not more tolerable. A Lombard ordinance of the late sixteenth century pointed out:

At the time when the weeds are pulled from the rice patches, or other work is performed in the rice fields, some individuals called “foremen of the rice workers” manage in various ways to bring together a large number of children and adolescents against whom they practice barbarous cruelties. Having brought the children with promises and inducements to the chosen place, the foremen then treat them very badly, do not pay them, do not provide these poor creatures with the necessary food, and make them labor as slaves by beating them and treating them more harshly than galley slaves are treated, so that many of the children, although originally healthy, die miserably in the farms or in the neighboring fields. As His Excellency the Governor does not want these foremen of the rice workers to act in the future as they did in the past or to continue to slaughter children, he orders this traffic to be stopped.6

In the eighteenth century the Austrian physician J. P. Frank wrote that:

In many villages the dung has to be carried on human backs up high mountains and the soil has to be scraped in a crouching position; this is the reason why most of the young people are deformed and misshapen.7

Preindustrial Europe also made widespread use of female labor in areas other than domestic service. First of all, women produced many commodities at home which today are produced industrially and exchanged on the market (bread, pasta, woollens, socks, and so on). Miniatures of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries show us, however, that women were also regularly employed in agricultural work, and documents show that, in the major manufacturing centers, women were widely employed in spinning and weaving in the workshops. In Florence, among wool weavers, women workers made up 62 percent of the labor force in 1604 and 83 percent in 1627.8

Textile manufactures were often organized on the basis of the putting-out system; that is, a merchant gave out raw wool, for example, to workers who worked in their own homes, and later collected the product from them for sale or for further processing. This system facilitated the employment of women who, between one task and another at home, busied themselves with work for the merchants. In 1631, when plague struck San Lorenzo a Campi, in Tuscany, and many houses were quarantined, a health inspector reported that he had “found a greater amount [of wool] than anticipated” and provided his superiors with a list of twelve houses in each of which a woman was working wool for some merchant.9

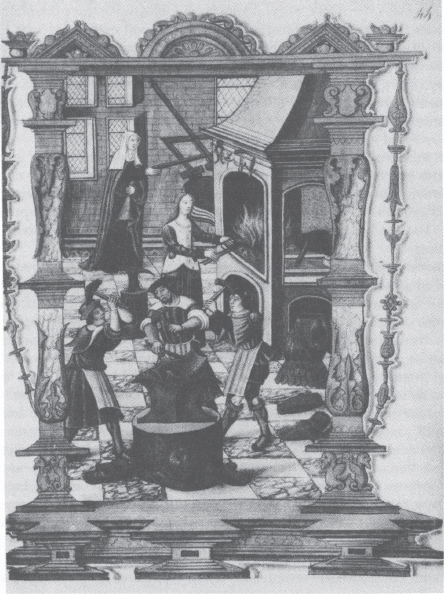

Women were also employed in work which we usually consider to be the preserve of men. In Toulouse, between 1365 and 1371, in the building yard of the Périgord College, men and women were employed in almost equal numbers, and the women carried stones and bricks in baskets, which they placed on their heads.10 The French miniature reproduced opposite depicts women employed in metallurgical works. In Venice women were largely employed in the arsenal in the manufacturing of sails.11

For a correct evaluation of female employment in the preindustrial era, one must also take into account wet nurses. The wet nurse is a person who, for a monetary reward, sells food (mother’s milk) and a service (care of the infant). The economic and social importance of wet nurses in preindustrial Europe compares with the importance of the baby-food industry in our contemporary society.

The “active” population can be usefully analyzed in relation to its distribution by productive activity.

Generally speaking, statisticians and economists like to distinguish between three broad categories of occupations, corresponding to the three sectors of activity respectively termed primary, secondary, and tertiary. The primary sector normally includes agricultural activities and forestry. Sometimes fishing and mining are also included. The secondary sector consists of manufacturing. The tertiary sector includes the “remainder.” Like all residual categories, this one is a source of ambiguity and confusion. In industrialized societies, the tertiary sector is mainly represented by the production of services such as transport, banking, insurance, the liberal professions, advertising, and the like. Some years ago, an Australian economist, Colin Clark, put forward the theory of a highly positive correlation between the general level of development of an economy and the relative size of the tertiary sector. But other economists with firsthand knowledge of certain primitive societies have shown that in a preindustrial society, the tertiary, or “residual” group, is also fairly large, with the difference that, instead of including bankers and insurance agents, it includes a picturesque variety of people with trades ranging from dealers in stolen goods to gatherers of used items.

A French metallurgical works. This sixteenth-century French miniature shows that women were employed also in metallurgical works where the skills they practiced in the kitchen were put to use in operating small furnaces.

Because of the lack of statistical data, no one will ever know with any degree of accuracy what percentage of the European population was employed in the primary sector at various times before the eighteenth century. Only for the middle of the eighteenth century are there some reasonable estimates relating to England, France, Sweden, and the Republic of Venice (see Table 2.6). They are still far from precise, but they can be taken as broad indications.

On this basis it does not seem far-fetched to maintain that in the centuries preceding 1700, in every European society, the percentage of the population actively employed in agriculture varied, as a rule, between 65 and 90 percent, reaching minima of 55 to 65 percent only in exceptional cases. The reason for this concentration lay in the low productivity of agriculture.

Seven or eight peasants succeeded with difficulty in producing (over and above what was necessary to maintain themselves and their families) the surplus necessary to maintain two or three other people. In particularly favorable circumstances, especially when water routes made the supply of cereals from abroad economical, a country could reduce the percentage of population actively employed in agriculture to below traditional levels. A typical case is that of Venice, which regularly imported grain from Lombardy, southern Italy, and the Black Sea, while the local population was engaged in everything but agriculture. A document dating from the end of the tenth century described the Venetians with amazement: et illa gens non arat, non seminat, non vindemiat (that nation does not plow, sow, or gather vintage). Venice’s case was exceptional, but between 1400 and 1700, marked developments in maritime transport made it possible for some countries with favorable geographical positions to depend considerably on the supply of grain from abroad. This was certainly the case with seventeenth-century Holland, which imported large quantities of cereals from eastern Europe via the Baltic-Sund-North Sea, not only for her own consumption, but also for re-export. Undoubtedly seventeenth-century Holland employed a much lower percentage of its population in agriculture than other European countries did, but even in the case of the Dutch Republic it is doubtful that the percentage ever fell below 50 percent. On the other hand, if the imports of the Dutch contributed to reduce the fraction of those employed in the primary sector in certain areas of western Europe, they favored an increase of the same fraction in the countries of eastern Europe. For every ten who ate bread, seven or eight had to produce wheat, and if these seven or eight were not all in one geographical area, they had to be in another.

Table 2.6 Estimates of population employed in agriculture as percentage of total labor force, about 1750

| Country | Percent |

| England | 65 |

| France | 76 |

| Sweden | 75 |

| Republic of Venice | 75 |

The large percentage of the population employed in the primary sector can easily lead one to overestimate the percentage of effective labor put into this sector. For a more precise assessment of the labor input, one has to take into account the fact that, for climatic reasons, during long periods of the year the peasant did not work; he was there, but he was not active, while most handicraftsmen were active all months of the year. Furthermore, peasants’ wives, normally regarded as being employed in agriculture, in addition to their agricultural activities generally contributed to the manufacturing sector (especially in weaving) and to the services sector (as domestic servants or as wet nurses) during the winter months.

It would be a mistake to imagine that the rural population coincided with the population employed in agriculture. Country villages were home not only to peasants, but to tailors, blacksmiths, carpenters, cobblers, and sometimes barber-surgeons and schoolteachers. Borrowing Louis Malassis’s classification, in the rural world we can distinguish between the agricultural sub-set, consisting of farmers, the agro-food sub-set, consisting of agricultural workers, a manufacturing and trading superstructure that processed and distributed farm products, and lastly the rural sub-set, covering all other activities of whatever type performed in the countryside or in country villages. In the middle of the sixteenth century, in the completely rural parish of Myddle in Shropshire which had a population of about 350 souls, roughly 11 percent of the adult male population were craftsmen – smiths, carpenters, tailors, cobblers, and coopers.12

Table 2.7 shows the occupational distribution of the population in selected European cities. The first thing to emphasize is the correlation between what emerges from these figures and what has been said in the preceding chapter about the structure of demand. The bulk of demand was concentrated on food, clothing, and housing. The structure of demand influences the price structure, which, in turn, determines the structure of production. It is, therefore, not at all surprising that in Table 2.7 the three sectors – food, textiles, and construction – account for the greater part of the active population under consideration – that is, broadly, from 55 to 65 percent. Those employed in the food sector represent a relatively small percentage because the data refer to urban populations, and the bulk of those employed in the production of food lived in the country. For Gloucestershire, in 1608, a census is available that includes not only three major cities (Gloucester, Tewkesbury, and Cirencester), but also the surrounding rural areas.13 Putting together both townsmen and country dwellers, one sees (Table 2.8) that those employed in the production and distribution of food represented by far the largest group (46 percent) and that the combined group of those employed in the three sectors of food, clothing, and construction represented about 73 percent of the working male population. However high the subtotals, a + b + c in Table 2.8 and a + b + c + d in Table 2.9, they still underestimate the relative importance of the mixed food-clothing-construction group, because, for example, many of those included in the category “leather” produced shoes and sandals and therefore should be added to the “clothing” sector, and many of those in the category “woodwork” produced goods and services connected with housing and therefore should be added to the “building” sector.

Table 2.7 Occupational distribution of the population of selected European cities, fifteenth to seventeenth centuries

| Verona 1409 | Como 1439 | Frankfurt 1440 | Monza 1541 | Florence 1552 | Venice 1660 | |||

| a. Food distribution and agriculture | 23 | 21 | 21 | 39 | 13 | 17 | ||

| b. Textiles and clothing | 37 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 41 | 43 | ||

| c. Building | 2 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | ||

| Subtotal: a + b + c | [62] | [55] | [59] | [65] | [60] | [64] | ||

| d. Metalwork | 5 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 5 | ||

| e. Woodwork | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 8 | ||

| f. Leather | 10 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 | |||

| g. Transport | 2 | 3 |  | 22 |  | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| h. Miscellaneous | 6 | 17 | 21.5 | 21 | 2 | |||

| i. Liberal professions | 10 | 6 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Sources: For Verona: Tagliaferri, Economia Veronese; for Como: Mira, Aspetti dell’Economia Comasca; for Frankfurt: Bucher, Die Bevölkerung von Frankfurt; for Monza: Cipolla, Per la Storia della Popolazione Lombarda; for Florence: Battara, Popolazione di Firenze; for Venice: Beltrami, Composizione Economica e Professionale. Domestic servants were not always included in the censuses on which the table is based.

In the discussion of the level and structure of demand, it was mentioned that the great disparity between the wealth of a few and the low average level of wages logically stimulated demand for domestic services. Kings were not the only ones to have a retinue of servants. In England in the thirteenth century the household of the Earl and Countess of Leicester counted sixty servants. The household of a minor baron like the Lord of Eresby included a steward, a wardrober, a wardrober’s deputy, a chaplain, an almoner, two friars, a chief buyer, a marshal, two pantrymen and butlers, two cooks and larderers, a saucer, a poulterer, two ushers and chandlers, a baker, a brewer, a potter and two farriers, and each had their own boy helpers. In the monastery of Evesham, in England in 1096, there were fifty-two servants for sixty-six monks and the former figure did not include gardeners, a blacksmith, a mason and other laborers of various kinds. In the monastery of Meaux (England) in 1393, twenty-six monks were served by forty domestics. Domestic service was abundantly available also to the middle and lower-middle classes. A Florentine census of 1551 shows that only 54 percent of the families of Florence were without domestic servants living with them (see Table 2.9).

Table 2.8 Occupational distribution of males, aged 20–60, in Gloucestershire, by percentages, 1608

| Cities | Countryside | Cities and countryside together | |

| a. Agriculture | 4 | 50 | 46 |

| b. Food and drink | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| c. Textiles and clothing | 26 | 23 | 23 |

| d. Building | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Subtotal: a + b + c + d | [39] | [77] | [73] |

| e. Metalwork | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| f. Woodwork | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| g. Leather | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| h. Transport | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| i. Professionals and gentry | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| j. Servants | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| k. Miscellaneous | 32 | 3 | 7 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: Tawney, “An Occupational Census,” p. 36.

Domestic personnel are not always easily pinpointed in the demographic and fiscal records of the time, because either the listings in the documents were limited to heads of families, or the service staff was mixed in with members of the family. In some urban censuses, however, domestic servants were listed separately. Whenever the available figures allow some calculations, the result is that in the European cities of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries domestic servants represent about 10 percent of the total population, which means about 17 percent of the population in the age group fifteen to sixty-five (see Table 2.10).

Table 2.9 Percentage distribution of families in Florence (Italy) according to number of servants, 1551

| % families | |

| With more than 5 servants | 5 |

| With 2 to 5 servants | 18 |

| With 1 servant | 23 |

| Without servants | 54 |

Source: Battara, La Popolazione di Firenze, p. 70.

Table 2.10 Domestic servants as a percentage of total population in selected European cities, 1448–1696

| City | Year | % |

| Freiburg | 1448 | 10 |

| Bern | 1448 | 9 |

| Nuremberg | 1449 | 19 |

| Basel | 1497 | 18 |

| Ypres | 1506 | 10 |

| Parma | 1545 | 16 |

| Florence | 1551 | 17 |

| Venice | 1581 | 7 |

| Bologna | 1581 | 11 |

| Rostock | 1594 | 19 |

| Bologna | 1624 | 10 |

| Florence | 1642 | 9 |

| Venice | 1642 | 9 |

| Münster | 1685 | 15 |

| Lille | 1688 | 4 |

| Ypres | 1689 | 7 |

| London (40 parishes) | 1695 | 20 |

| Dunkirk | 1696 | 6 |

Devoutness and superstition strengthened each other in creating and supporting the demand for religious services. On the other hand, widespread devoutness led many individuals of both sexes into the ranks of the clergy. Other factors also favored the increase in the ecclesiastical population. The institution of the dowry was an incubus for most families and a danger to the integrity of the family inheritance. In Europe to solve the problem the well-to-do frequently confined their daughters to a convent.

Table 2.11 provides some data on the ecclesiastical population in selected European cities from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. Viewing a region as a whole, one finds that in 1745 the Great Duchy of Tuscany had 890,605 inhabitants, including

Clerics: 3,955

Priests: 8,095

Monks: 5,482

Hermits: 168

Nuns: 9,736

The 27,436 ecclesiastics represented about 3 percent of the total population.14 Beloch has estimated that, at the middle of the eighteenth century, in all of Italy the ecclesiastical population represented about 2 percent of the total population.15 In 1591, Spain, with a total population of about 8.5 million people, had about 41,000 priests, 25,000 friars, and 25,000 nuns.16 Thus the clergy represented about 1.1 percent of the total population. About France we know that in Alsace and the area of Alençon, at the end of the seventeenth century, of a total of 409,822 inhabitants the clerical population numbered 4,609 individuals, or about 1.1 percent. In Brittany in 1696, the ecclesiastical population amounted to 18,889 in a total population of 1,654,699 – again about 1.1 percent. In the area of Caen, out of 609,203 inhabitants, the clergy totaled 5,225 – that is, nearly 1 percent.17 In England and Wales in 1377 the priests numbered about 24,900 and the monks and nuns about 10,600. In a total population of some 2.2 million people the clergy represented about 1.5 percent. In the first decades of the sixteenth century in England and Wales there were about 9,300 monks and nuns in a population of approximately 3.5 million inhabitants.18 In Poland around 1500 there were about 6,900 monks and nuns and about 15,000 priests. The population of Poland numbered about 4.5 million, thus the clergy represented about 0.5 percent.19 In considering these figures one has to bear in mind that, given the age composition of preindustrial populations, 1 or 2 percent of the total population meant respectively 1.5 or 3 percent of the population above age fifteen.

From an economic point of view the clergy can be seen as producers of a particular type of service, and, inasmuch as there is a demand for this service (a demand which, like all other producers, the clergy does its best to stimulate) the clergy have the right to be considered part of the economically active population. In most respects the contribution of the clergy to a community is not different from that of psychiatrists in modern societies, and it has been observed that in countries where people have no recourse to the confessor, they end up by having recourse to the psychiatrist (with the disadvantage that individually they pay much more for the service). In addition, in preindustrial Europe, and especially in rural areas, the parish priest often also performed those functions which we now regard as belonging to the schoolteacher and the doctor.

Table 2.11 Ecclesiastical population in selected European cities, 1400–1700

| Total Population (thousands) (a) | No. of priests (b) | No. of monks & nuns (c) | Total no. of priests monks & nuns (d) | Clergy as %of total population | ||||

| City | Date |  |

|

| ||||

| Toulouse | c. 1400 | c.23 | c. 1,000 | 4.3 | ||||

| Frankfurt | 1440 | 10 | 225 | 2.3 | ||||

| Nuremberg | 1449 | 20 | 250 | 1.3 | ||||

| Bologna | 1570 | 62 | 3,310 | 5.3 | ||||

| Venice | 1581 | 135 | 586 | 3,553 | 4,139 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| Naples | 1599 | 233 | 5,702 | 2.4 | ||||

| Besançon | c. 1600 | 11 | 600 | 5.5 | ||||

| Rome | 1603 | 105 | 1241 | 4,512 | 5,753 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| Cremona | 1621 | 40 | 150 | 1,852 | 2,002 | 0.4 | 4.6 | 5.0 |

| Florence | 1622 | 66 | 4,917 | 7.5 | ||||

| Pisa | 1622 | 15 | 951 | 6.3 | ||||

| Bologna | 1624 | 62 | 138 | 3,431 | 3,569 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 5.7 |

| Venice | 1642 | 120 | 735 | 4,171 | 4,906 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 4.1 |

| Siena | 1670 | 16 | 1,755 | 10.9 | ||||

| Pistoia | 1672 | 8 | 726 | 9.1 | ||||

| Besançon | 1709 | 17 | 275 | 571 | 846 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 5.0 |

One of the major drawbacks of traditional textbooks is that they identify the active population of preindustrial Europe with merchants, craftsmen, landlords, and peasants and they neglect professionals, in particular notaries, lawyers, and physicians. There was considerable demand from the private sector as well as from the public sector for the services of professionals, and this aspect of the problem has been discussed above in Chapter 1. Tables 2.12 and 2.13 provide some data relating to the size of the major professions in selected European cities. The Italian cities of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries stand out for the size of the professional group and especially for the size of the notarial profession. Between the tenth and the fourteenth centuries the notaries constituted the bulk of the bureaucracy of the Italian cities. Table 2.13 shows also that the number of physicians was generally relatively higher in Italian cities than in other European towns, at least until the end of the seventeenth century. Whether this was beneficial to people’s health is another matter altogether. Most likely it was harmful,20 but if people were prepared to pay for doctors’ services, the supply of such services satisfied psychological needs, and, therefore, the availability of doctors, regardless of what they were able to do, must be put on the same plane as that of priests and hermits.

From the economic and social points of view, the importance of notaries, lawyers, and doctors can hardly be exaggerated and most certainly it was far out of proportion to their numbers. To begin with, members of the medical, legal, and notarial professions usually belonged to the small circle of the well-to-do, many of them as affluent as the rich merchants. Enjoying high incomes, physicians, lawyers, and notaries originated a demand for distinctive clothing, beautiful houses, and land, as well as for books, entertainment, and educational services for their children. Moreover, physicians, lawyers, and notaries gave the middle class a strength, respectability, and prestige that affluence alone could never have procured.21

Table 2.12 Number of notaries, lawyers, and physicians in relation to total population in selected Italian cities, 1268–1675

| Per 10,000 inhabitants | ||||

| City | Year | Notaries | Lawyers | Physicians |

| Verona | 1268 | 124 | ||

| Bologna | 1283 | 212 | ||

| Milan | 1288 | 250 | 20 | 5 |

| Prato | 1298 | 278 | ||

| Florence | 1338 | 55 | 9 | |

| Verona | 1409 | 70 | 6 | 3 |

| Pisa | 1428 | 90 | ||

| Como | 1439 | 17 | 12 | 2 |

| Verona | 1456 | 54 | 4 | 9 |

| Verona | 1502 | 40 | 6 | 5 |

| Verona | 1545 | 26 | 7 | 5 |

| Verona | 1605 | 8 | 17 | 4 |

| Carmagnola | 1621 | 21 | 14 | 3 |

| Florence | 1630 | 5 | ||

| Pisa | 1630 | 9 | ||

| Rome | 1656 | 12 | ||

| Rome | 1675 | 13 | ||

Source: Cipolla, “The Professions,” p. 43.

Table 2.13 Number of physicians in relation to total population in selected European cities, 1575–1641

| City | Year | Physicians | Population (thousands) | Doctors per 10,000 inhabitants |

| Palermo | 1575 | 22 | 70 | 3.1 |

| Florence | 1630 | 33 | 80 | 4.1 |

| Pisa | 1630 | 12 | 13 | 9.2 |

| Pistoia | 1630 | 5 | 9 | 5.5 |

| Rome | 1656 | 140 | 120 | 11.6 |

| Rome | 1675 | 164 | 130 | 12.6 |

| Antwerp | 1585 | 18 | 80 | 2.2 |

| Rouen | 1605 | 16 | 80 | 2.0 |

| Lyons | 1620 | 20 | 90 | 2.2 |

| Paris | 1626 | 85 | 300 | 2.1 |

| Amsterdam | 1641 | 50 | 135 | 3.7 |

Source: Cipolla, Public Health, Chapter 2.

Economic history, if it is to make sense, must include social history, taking account of values and factors which cannot be measured in solely economic terms. The history of the professions is an essential part of the story of “intangible” values. Scholarly prestige, restrictive practices through the enforcement of licensing, relatively high personal income – all these factors individually reinforced each other and in combination made possible the social ascent of the professionals. In this respect medieval and Renaissance Europe stands out as a unique example in world history. In other parts of the world, such as China, the providers of medical and legal services never succeeded in asserting themselves socially as well as economically. In certain other societies they did, but as members of a priestly caste. Only in western Europe, during the Middle Ages, did the professionals clearly separate themselves from the clergy and still move to the higher steps of the social ladder. The preeminence acquired in medieval western Europe by the professionals is at the origin of many institutions and characteristics of our industrial societies.

Obsessed with merchants, craftsmen, landowners, and peasants, economic historians have usually ignored the representatives of “the oldest profession in the world.” Medieval canonists were more realistic: Thomas de Chobham had no doubts – the prostitutes work, he maintained, even if their work is ignominious. A distinction must obviously be made between general prostitution and legalized prostitution. As regards the first, one cannot hope to have adequate information, but as regards the second, enough is known to justify the statement that, squalid though it may be, this sector always had great economic relevance. Moreover, it is easy to show that there is some positive correlation between the economic development of a given center and the presence of women of easy virtue. The fairs that were held in the province of Scania (southern Sweden) between August 15 and November 9 in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (the famous nundinae Schanienses) were well known not only for the number of merchants and fishermen who met there, but also for the number of fahrende Frauen.22

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the two major centers of prostitution in Europe were Venice and Rome, a primacy which, with the Industrial Revolution, was to be taken over by London and Paris. The game-some ladies of Venice, called courtesans, were famous for their refinement and culture and, as Thomas Coryat wrote, “the name of a Cortezan of Venice is famous all over the Christendome.”23 In the sixteenth century, Montaigne, who was a great gossip as well as a great mind, relates that the Cardinal d’Este regularly traveled to Abano for the baths, but even more to visit the “lovelies” of the Serenissima.24 In fact, the courtesans were one of Venice’s main attractions for tourists and traders, and the English travelers of the early seventeenth century have left valuable information on the subject.

To establish numbers of prostitutes is a difficult task. First of all, the occupation does not lend itself to an exact definition, because between the two extremes of “honest woman” and “common prostitute” there is a vast range of intermediate conditions with blurred outlines. Second, anyone wishing to make a survey of the subject inevitably finds himself faced with reticence of every possible kind. Finally, the topic is such as to lend itself easily to the most fanciful tales. In Florence in the sixteenth century it was held that “about 8,000 courtesans” plied their trade,25 but the 1551 census recorded only three.26 The first figure is certainly an exaggeration, but the second does not reflect the truth, as witnessed by a poem of 1533 that lists forty women of easy virtue, describing them by name, surname, and noting their various qualities.27 In sixteenth-century Venice, those interested in “all that the brigand apple brought” could buy at little expense a booklet containing the “tariff of all prostitutes in which one finds the price and the qualities of all courtesans of Venice.” According to two chroniclers of the early sixteenth century, there were then in Venice about 12,000 official prostitutes, but the figure is probably an exaggeration.28

In Rome, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was said that there were 10,000 to 40,000 prostitutes.29 Possibly this figure too was an exaggeration. Official figures are of course, as Table 2.14 indicates, much lower, ranging from 7 to 9 per thousand of total population. In assessing such figures, however, one has to bear in mind that in Rome, with its exceptional preponderance of priests, monks, and cardinals, women were under-represented. In 1600, out of 109,729 inhabitants, there were only 46,596 females, and the women in the fifteen to sixty-five age group must have numbered approximately 30,000; thus the 604 women of easy virtue listed in the census of that year represented about 2 percent of the adult female population of Rome. For a holy city, the percentage looks high, especially if one considers that the figures refer only to those prostitutes who were officially recognized as such.

The economic importance of this social group was more than proportional to its numerical size. Thomas Coryat, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, wrote of Venice:

Some of them [the courtesans] having scraped together so much pelfe by their sordid facultie as doth maintaine them well in their old age: for many of them are as rich as ever was Rhadope in Egypt, Flora in Rome or Lais in Corinth. One example whereof is Margarita Aemiliana that built a faire monastery of Augustinian monkes.30

About the same time, Fynes Moryson wrote:

Each cortizan hath commonly her lover whom she mantaynes, her balordo or gull who principally mantaynes her, besydes her customers at large, and her bravo to fight the quarrells. The richer sorte dwell in fayre hired howses and have their owne servants but the common sorte lodge with bandes called ruffians, to whome in Venice they pay of their gayne the fifth parte, as foure shillings in twenty, paying besydes for their beds, linnen and feasting, and when they are past gayning much, they are turned out to begg or turne bandes or servants.

Table 2.14 Number of officially recognized prostitutes in relation to total population of Rome, 1598–1675

| Year | Total population | Prostitutes | Prostitutes per 1,000 inhabitants |

| 598 | 97,743 | 760 | 8 |

| 1600 | 109,729 | 604 | 6 |

| 1625 | 115,444 | 940 | 8 |

| 1650 | 126,192 | 1,148 | 9 |

| 1675 | 131,912 | 889 | 7 |

Source: Schiavoni, “Demografia di Roma.”

Since official prostitutes were taxed for their trade, in the larger towns they represented an important source of income for the public finances. According to Robert Dallington, at the end of the sixteenth century the Grand Duke of Tuscany “hath an income out of the brothel stewes which is thought at the least thirty thousand crownes a yeare in Florence onely.”31 In Rome, the attempt made by Pius V in 1566 to expel prostitutes from the Holy City failed because, in the words of the Venetian ambassador, Paolo Tiepolo,

to send them away would be too big a thing, considering that, between them and others who for various reasons would follow them, more than 25,000 people would leave this city; and tax-farmers in Rome let it be understood that (if the prostitutes were expelled) they would either renounce their contracts or ask for a compensation amounting to 20,000 ducats a year.32

Italy has always been the country of the oddest compromises. We have already seen in the passage by Coryat that a monastery of the Augustinians in Venice was built with funds provided by a prostitute. In Rome, prostitutes were under obligation to bequeath part of their possessions to the Monastery of the Converted. When Pius V dedicated himself to the building and beautifying of the Civitas Pia, one of the expedients to which he had recourse in order to raise funds was to release the prostitutes from the obligation to bequeath part of their possessions to the monastery as long as they contributed at least 500 scudi toward his holy building.33

As has already been said, it would be wrong to identify the rural population wholly with the agricultural population, and the urban population entirely with the active population in the secondary and tertiary sectors. In the suburbs of the cities lived laborers who grew vegetables or performed other essentially agricultural activities. On the other hand, one encountered artisans and a few professional people also in small rural and semi-rural communities. As Christopher Dyer pointed out, the frequent finds of spindle whorls in excavations on village sites show that spinning yarn with a distaff was an almost universal practice among peasant women. Large-scale industrial employment was often localized, like the tin-mining and smelting which occupied as many as one in ten of the population of Cornwall. The woods themselves provided an environment for a wide range of crafts, for potters, glass-makers, coopers, turners, wheelers, cartwrights, arrow-makers, bow-makers, and charcoal burners. In the village of Lomello (Lombardy) around 1435, out of a population of about 500 or 600, there were at least two tailors, one weaver, a schoolteacher, and other artisans.34 In 1541 in the area of Monza (Lombardy), in the rural centers numbering fewer than 200 inhabitants each, those engaged in agriculture made up about 75 percent of the population; the remaining 25 percent consisted of craftsmen, traders, cart drivers, boatmen, and the like.35 In the wholly rural Shropshire parish of Myddle (England) with a total population of around 350 in the mid-sixteenth century, about 11 percent of its adult male population were craftsmen – blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, tailors, shoemakers, though, as was normal, many such men were small husbandmen as well.36 In the small rural parish of Ealing in Middlesex (England) in 1599, out of 426 inhabitants there were three tailors, one smith, one carpenter, one wheelwright, and four clerks.37 In France in 1691 in the small rural parish of Laguiole, among 990 people were found one lawyer, six barber-surgeons, one schoolteacher, five master cobblers and eight journeyman cobblers, four master tailors and three journeyman tailors, one architect, three master masons and three journeyman masons, two carpenters, eight weavers, one glazier, three lock-smiths, one wool-draper, and other craftsmen.38

The presence of skilled labor both in the cities and in the countryside was a decisive factor for the success of manufacturing activity. Current economic analysis tends to stress the importance of human capital, but this is not a modern discovery. If anything, it is a rediscovery. In the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance, the relevance of human capital to economic prosperity was taken for granted. Governments and princes were active in trying to attract artisans and technicians and in preventing their emigration. We shall return to this point in Part II, when dealing with the spread of technology. Here, however, it is worth mentioning a significant example.

In 1230, the Commune of Bologna launched a definite policy of economic development. The idea was to encourage the setting up and development of textile manufactures, particularly wool and silk. To achieve its aim, the Commune announced that those artisans who would move to Bologna and start an enterprise would enjoy the following advantages:

a. they would receive free, from the city, a tiratorium (or the equivalent value of 4 lire) and two looms (or the equivalent value of 2 lire each)

b. a loan of 50 lire for five years free of interest, to cover the expenses for the initial installation, the cost of raw materials, upkeep of the family, and so forth

c. exemption from all taxes for fifteen years

d. immediate grant of citizenship

In the two years 1230–31, 150 artisans with their families and their assistants settled in Bologna. (At that time Bologna numbered at most 25,000 inhabitants.) In its undertaking, the Commune of Bologna freely distributed some nine thousand lire of the time, a very large sum.39 The operation was repeated in 1385 and between 1385 and 1389 more than 200 craftsmen (not counting their relatives) migrated to Bologna.

Bologna’s case is particularly interesting because of the early period in which it took place, because of the size of the operation in both human and monetary terms, and for the excellent documentation which has survived but, as we shall see in Chapter 6, one encounters many similar cases in the following centuries. They show that everywhere in Europe public powers were very much aware of how important the availability of skilled labor was to economic progress.

The number employed in a particular sector of the economy tells us something, but not everything, about the effective quantity and quality of the labor in that sector, both in an absolute sense and in relation to labor inputs in other sectors. A lot depends on the number of working days actually put in, the number of working hours per working day, the physical and psychological condition of the workers, and the workers’ level of education and technical training.

A Lombard document dated 1595 recorded that

the year consists of 365 days, but 96 are holy days, and thus one is left with 269. Of these, a great many are lost, mostly in wintertime and even at other times, because of rain and snow. Another part of the year is lost because everyone does not always find work, except in the three months of June, July and August.40

The document in question refers to agricultural labor and points out that religious festivities and climatic and seasonal conditions had a marked effect on the amount of labor actually put into productive activities. The holidays were traditionally numerous. The above document cites a total of ninety-six a year in Lombardy. They numbered eighty to ninety a year in sixteenth-century Venice, eighty-seven in sixteenth-century Florence, and one hundred and forty in Prato.41 In Protestant Europe the Reformation noticeably reduced their number.42

Climatic conditions and seasonal fluctuations in demand hit agricultural and building activities especially hard. Consequently, the percentages of those employed in agriculture and construction tend to overestimate the proportion of labor inputs in these sectors in relation to labor inputs in other sectors of the economy.43

We know very little about the physical and psychological conditions of the labor force before the Industrial Revolution. We do know that the mass lived in a state of undernourishment. This gave rise, among other things, to serious forms of avitaminosis. Widespread filth was also the cause of troublesome and painful skin diseases. To this must be added in certain areas the endemic presence of malaria, or the deleterious effects of a restricted matrimonial selection, which gave rise to cretinism. As late as 1835 L. R. Villermé wrote that in France out of 343 recruits from the lower orders, only 100 were fit for military service.44 To all this one should add the effects of occupational diseases due to the appallingly unhealthy conditions under which certain trades were conducted and to the handling of toxic substances.

Separately or together, these factors had a negative influence on the quantity and quality of effective labor inputs. On the other hand, the beauty and perfection of many products of European preindustrial craftsmanship give the inescapable impression that the craftsman of the time found in his work a satisfaction and a sense of dignity which are, alas, foreign to the alienating assembly lines of the modern industrial complex.

Little or nothing is known of the level of education of the masses before the Industrial Revolution. The urban revolution of the eleventh and twelfth centuries ushered in a new era with the introduction of public schools, and many a city witnessed a noticeable development of elementary education. In Florence, around 1330, Giovanni Villani recorded: “There are from 8,000 to 10,000 boys and girls who are at school learning how to read and from 1,000 to 1,200 boys who learn abacus and arithmetic” in the schools.45 We know from other sources that Florentine youths went to school to learn reading and writing at the age of five or six. At the age of eleven, those who were both willing and able continued their education in one of the six schools of arithmetic where they remained for two to three more years. About 1338, Florence had a population of roughly 90,000 inhabitants. Given the age structure of populations in those days, the age group between five and fourteen must have consisted of about 23,000 children. If Villani’s data are correct, more than 40 percent went to school. A document dated 1313 shows that in Florence it was taken for granted that an artisan should be able to “write, read, and keep accounts,” and it is known that a good many humble Florentine artisans wrote extremely readable, and, for us, instructive, family histories.46

Florence was in the vanguard of Europe in the fourteenth century. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, one city after another followed her example, but the spread of elementary education among the masses long remained a typically urban characteristic. In the Protestant countries the Reformation succeeded in spreading the rudiments of reading and writing among the rural population, but in Catholic countries the bulk of the peasants remained illiterate until the modern era. About the middle of the seventeenth century, less than 50 percent of the adult population of the major western European cities were illiterate; elsewhere, the figure ranged from 50 to 95 percent.47

These observations lead us to discuss education and professional training in an economic context.

To raise and educate a child costs money. If the young person is of working age and is instead sent to school, the person also costs the economy what he does not produce. That which the young person could produce if he were sent to work and does not because he is at school is income forgone for the economy and represents an opportunity cost.

These costs are borne by the family and the society, in expectation of future incomes. What is spent in raising and educating a person is a form of investment, which is directly comparable to the building of a factory. While it is being built, the factory, too, does not produce and the cost of construction is borne in expectation of future incomes. In the training of a person, as in the building of a factory, the investment can be a good one or a bad one. A student who studies little and badly during his school years is the equivalent of a factory which is badly built: the defects will become evident when production starts.

The poverty of preindustrial societies did not allow for large investment in human capital. A few years at school were a luxury that not many could afford, especially in the country. Apprenticeship offered the advantage that the young people produced while they learned; thus the opportunity cost of their education was practically eliminated. In fact, all professional and technical training was given by way of apprenticeship.

In Venice, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the ages for acceptance into apprenticeship in certain trades varied from ten to twelve years (see Table 2.15). The average duration of apprenticeship varied according to trades; for instance:

victualling and sale of products of the soil:

5 years production of clothing or personal services:

3 years other trades: 5 years

Table 2.15 Age limits for acceptance into apprenticeship in selected trades in seventeenth-century Venice

| Age limit | ||

| Trade | Minimum | Maximum |

| Tinkers | 16 | |

| Dyers | 20 | |

| Weavers | 12 | 17 |

| Stonecutters | 11 | 13 |

| Caulkers | 10 | 20 |

| Painters | 14 | 16 |

| Goldsmiths | 7 | 18 |

| Sausage makers | 16 | 18 |

Source: Beltrami, Popolazione di Venezia, pp. 198–99.

The guilds regulated professional education in every detail, and in some cases, to the benefit of the children of their own members, they even organized school courses to teach the rudiments of reading and writing.48

Originally, training for the higher professions – jurisprudence, medicine, and notarial art – also took place through various forms of apprenticeship. But from the end of the twelfth century, and more decidedly in the thirteenth century, special schools were created, from which the universities emerged.

The main trouble with employment statistics is that they encourage us to regard people as if they were potatoes. Taking account of a worker’s education and his psychological and physical conditions is a step in the right direction, but a very small one. In any statistics on employment, Michelangelo would figure as “sculptor: 1.” Or if the statistics were fairly advanced, he might be slotted into the category of “artisans (or artists) with more than 10 years’ education.” And that would be the end of it. The statistics we possess leave out the most important feature of work, i.e. the human element, the most profound meaning of which cannot be measured in quantitative terms – or, if it can, we have not yet found out how. Michelangelo is an extreme case but there is a world of difference between work that is prepared and executed with care and efficiency and work that is slapdash and aimless. We take work to cover not just unskilled laboring but any and every kind of productive activity. Anyone who has had the opportunity to compare developed and underdeveloped societies will readily acknowledge that the difference between the two lies in the value of “human capital” in both the upper and the lower classes. The trouble that besets an underdeveloped country is not so much the lack of capital or the backwardness of technological knowledge as the poor quality of the human component: an underdeveloped country has entrepreneurs who are of little value, workers worth even less, teachers who are incompetent, students who laze around, rulers who don’t know how to rule, and citizens devoid of any civic sense. This is why a country remains underdeveloped. A country’s shortage of capital and its technological and administrative backwardness are more a consequence than a cause of its underdevelopment.

Education plays an important part in any upgrading of human capital. But education is not enough. For a society to function properly, psychological and ethical qualities are also essential: a spirit of co-operation, a sense of honesty, tolerance, self-sacrifice, initiative, perseverance, intellectual curiosity, a willingness to experiment, etc. The analysis of these factors is one of the most difficult and neglected areas in the social sciences. Econometric techniques are particularly ill-suited to this kind of investigation. And other types of analysis tend to be terribly vague and inconclusive.

One of the fundamental characteristics of the urban societies of preindustrial Europe was the tendency toward association, which manifested itself increasingly from the end of the twelfth century. If in the preceding centuries men had sought protection and the safeguard of their own interests in a relationship of subordination to the powerful (feudalism), with the emergence of urban societies the safeguard of personal interests was sought mainly in associations among equals. This was the essence of the urban revolution. The commune was initially nothing more than the sworn association of citizens – the super-association, above and beyond the particular associations which took the name of Arti, guilds, companies, confraternities, societies, or universities.

Class and group conflicts played a fundamental part in determining who could and who could not form a guild, and the dominance or decline of a group signified the opportunity (or lack of it) for rival groups to unite in a legally recognized guild. Within the guilds, a definite order of precedence faithfully reflected the distribution of power. For the whole of the thirteenth century, merchant guilds remained unchallenged in dominating the European scene. In the ensuing centuries, various occupational categories gradually acquired the right to constitute themselves into autonomous associations, and the craft guilds became increasingly influential.

The guilds satisfied a number of requirements. Among the various tasks of the guilds, there was usually that of collective organization of religious ceremonies, charity, and mutual assistance. These tasks were not a smoke-screen. For a craftsman of the time, participation by his own guild in the town’s procession in honor of the patron saint or the Virgin Mary was as important as, if not more important than, a discussion of wages and production. And the guilds played an important role in providing social assistance to their own members and education for their members’ children as well as in setting and enforcing quality controls in production.

All these functions should not be underestimated. But neither should one underestimate the fact that one of the fundamental aims of all guilds was to regulate and reduce competition among their own members. With regard to the supply of labor, a guild aimed at exercising strict control over the admission of new members and their entry into the labor market. On the other hand, when competition among employers was in question, the corporate body always served to control and strictly regulate competition among its members as far as demand for labor was concerned. Consequently, in any study of the level and structure of employment and wages in centuries preceding the eighteenth, the action of the guilds must occupy a salient position.

Physical capital is represented by goods which are produced by people and are not consumed, being either used as productive inputs for further production or stored for future consumption. Capital can be usefully divided into fixed capital and working capital

Fixed capital consists of those economic goods produced by people which are repeatedly used in the course of a number of productive cycles. Machine tools are the classical type of fixed capital, but the shovel, the plow, and the barrel, as well as the ship, the cart, and the bridge are also fixed capital.

Sir John Hicks wrote a few years ago:

What is the essential mark by which we are to distinguish modern industry from the handicraft industry? ... This is a clue to the distinction between the two kinds of industry for which we are looking.

The capital of a merchant is, mainly, working or circulating capital – capital that is turned over. A particular merchant may indeed employ some fixed capital, an office, a warehouse, a shop or a ship; but these are no more than containers for the stock of goods on which his business centres. Any fixed capital that he uses is essentially peripheral.

As long as industry remained at the handicraft stage the position of the craftsman or artizan was not so very different. He did indeed have tools, but the tools which he used were not usually very valuable; the turnover of his material was the centre of his business. It is at the point when fixed capital moves, or begins to move, into the central position that the revolution occurs. In the days before modern industry, the only fixed capital goods that were being used, and which absorbed in their production any considerable quantity of resources, were buildings and vehicles (especially ships).49

The thesis that fixed capital acquired a degree of importance only with the Industrial Revolution and, even then, only in the final stages of the Revolution, has never been questioned and has, indeed, been reasserted emphatically by a number of scholars.50 However, even as a first and rough approximation, the statement needs qualifications.

Fixed capital was admittedly of negligible importance before the eleventh century when all forms of capital were in any case in painfully short supply. Documents of the eighth century clearly suggest that large estates suffered from a shortage of livestock.51 In the ninth century, of the twenty-nine farms of the Abbey of St Germain des Prés outside Paris, only eight had water mills (though these totaled fifty-nine); and at the beginning of the tenth century, the records of the Abbey of St Bertin referred to the construction of a mill as an exceptional and admirable event.52

From the eleventh century onward, however, things changed considerably. Water mills and windmills proliferated and became a common feature of the rural landscape. Toward the end of the eleventh century in England, more than 5,600 mills were in operation and in some areas, such as Surrey, there was a mill for every thirty-five recorded families.53 In 1350, in the territory of Pistoia (Italy), there was approximately one mill for every twenty-five recorded families.54 In the course of time, not only did the number of mills continue to increase, but their average power per unit also increased. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, more than half a million water mills operated in western Europe, and many of them had more than one wheel.

Besides water mills and windmills, other buildings related to agriculture grew both in number and in size in the centuries following the year 1000. Barns deserve special mention because many of them not only represented a sizeable investment (see Table 2.16) but were built so beautifully that they are no less relevant to the history of architecture than castles and cathedrals.55

As buildings grew in number and in size, tools were improved and were produced in larger quantities.56 Most important of all, livestock became more abundant. Horses, cattle, and sheep were a special kind of fixed capital. (I call it “a special kind of capital” because livestock can be consumed as food whenever necessary or convenient.) On nine Ramsey Abbey manors in eastern England, draft animals increased by 20 to 30 percent between the end of the eleventh and the mid-twelfth century.57 At the end of the thirteenth century in the territory of Chieri (Piedmont) over an area of about 20,000 acres, there were four cattle and six sheep for every 100 acres.58 In 1336 on about 1,900 acres owned by Merton College (England), of which about two-thirds were arable land, there were four horses, twelve cattle, and sixty sheep for 100 acres.59 In 1530 six country parishes in Brianza, north of Milan (Italy), there were 11,058 persons above seven years of age, 762 children below seven years of age, and 1,823 animals. For every 100 persons older than seven, there were, therefore, about seven children and sixteen animals.60 In 1574 on property belonging to the Hospital at Imola (Italy), there were 96 persons. Of these, 33 were workingmen who made use of fifty-one head of cattle and thirty-seven sheep, with a ratio of cattle to laborers of about 1.5 to one.61 An inquiry made in 1471 in the regions of Grasse, Castellane, Guillaume, and Saint-Paul-de-Vence in Haute-Provence (France) yielded the following results:62

Table 2.16 Volume of selected barns built in the thirteenth century

| cubic ft | |

| Cholsey (Berkshire) | 482,680 |

| Beaulieu-St Leonard (Hampshire) | 526,590 |

| Vaulerand (France) | 869,980 |

Source: Horn and Born, The Barns, p. 41.

| No. of localities | No. of household | No. of donkeys, mules and horses | No. of sheep and goats | Head of cattle | |

| Totals | 70 | 3,167 | 2,494 | 114,837 | 5,498 |

| Averages: | |||||

| Per locality | 45 | 36 | 1,641 | 78 | |

| Per household | 0.8 | 36 | 2 |

For the period 1560–1600, the following estimates have been calculated for various parts of England:63

| Percentage of peasant laborers possessing | |||

| cows, calves heifers, | other cattle | No. of cattle per 100 laborers | |

| Northern Lowlands | 74 | 26 | 227 |

| Northern Highlands | 84 | 16 | 197 |

| Eastern England | 82 | 18 | 122 |

| Midland Forest Area | 92 | 8 | 142 |

As one can see from the figures quoted above, the ratios of animals to land, of animals to laborers, and of animals to population varied greatly from one area to another and from one period to another. But always and everywhere, animals were a form of fixed capital which was far from being “peripheral” to the productive system. Toward the end of the seventeenth century, William Petty calculated that, if the value of all agricultural land in England could be estimated at about £144 million, the animals could be valued at a quarter of that sum, that is, at about £36 million.64 In many areas, livestock was much more abundant in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance than in modern times. For six of the seventy localities in Haute-Provence covered by the aforementioned inquiry of 1471, the following comparison has been made:65

| No. of households | No. of sheep and goats | Head of cattle | |

| in 1471 | 863 | 25,050 | 1,451 |

| in 1956 | 12,834 | 471 | 407 |

Horses, cattle, and sheep were capital not only for agriculture. Sheep provided the raw material for the woollens industry. Horses and oxen were indispensable for transport. Also, the military sector relied heavily on this sort of capital. From the fifteenth century onward, armies tended to move with greater speed as horses and mules gradually replaced oxen as a means of transport in military operations. As late as the second half of the nineteenth century in several European countries, the census tabulations included not only people, but also horses and mules; and the object of the enumeration was essentially military. Toward 1845, the number of horses and mules available in the major European nations was estimated as shown in Table 2.17.

As mentioned above livestock as a form of capital has the advantage that when necessary or advisable it can be killed and consumed as food: its cost is not all sunk cost. On the other hand, livestock as a form of capital had the disadvantage of being highly vulnerable. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, epizootic diseases were no less frequent or disastrous than epidemics.66 At times, these diseases assumed international political significance, as when in Pannonia, in 791, nine-tenths of Charlemagne’s horses died and the Frankish king found himself in great military difficulties.67 More often, an epizooty was of purely local significance, but not infrequently it brought tragedy to entire regions. In 1275, “A rich man of France brought into Northumberland a Spanish ewe, as big as a calfe of two yeares, which ewe being rotten infected so the country that it spread over all the realme; this plague of murrain continued for 28 years”68 Between 1713 and 1769 in Frisia, major epizootics caused the following losses:69

December 1713-February 1715: 66,000 head of cattle

November 1744-August 1745: 135,000 head of cattle

November 1747-April 1748: 23,000 head of cattle

May 1769-December 1769: 98,000 head of cattle

When cattle died, the consequences for the economy of the time were comparable with the consequences of large fires which would destroy machines and power stations in a modern industrial economy. Moreover, replacement was made difficult by the fact that among horses, cattle, and sheep, sterility was very widespread. For the territory of Montaldeo (Italy), a survey of forty-nine cows during the period 1594–1601 shows an index of sterility of about 50 percent, with only twenty-five calves born; the sterility of sheep in Montaldeo was even higher, about 70 to 75 percent.70

Table 2.17 Number of horses and mules in selected European countries, about 1845

| Country | Horses and mules |

| Austria (Empire) | 2.7 million |

| France | 2.7 million |

| England | 2.3 million |

| Italy | 1.0 million |

| Prussia | 1.5 million |

| Russia | 8.0 million |

Source: Balbi, L’Austria, p. 165 and Annuario Statistico Italiano, 1857, p. 554.

Despite being small, hungry, and often sterile, horses, oxen, and sheep were an extremely valuable form of capital. Supply was limited and demand was high. In Montaldeo in the seventeenth century, one had to accumulate the wages of 100 ten-to-twelve-hour work days to buy one cow. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, it was necessary to sell over 50 liters of wine to buy one small pig.71

The value of this form of capital was a temptation to the mass of the poor. Fernand Braudel wrote that “... in England at the beginning of the nineteenth century, thieves and horse-thieves were a class of their own.72 The fact is that cattle thieves were a thriving and numerous class not only in England, but in all European countries.

Contrary to what one would expect, fixed capital was not peripheral, even in areas of the tertiary sector. A study of fifteenth-century Lombard pharmacies shows that their working capital amounted to only 30–35 percent of the investment; fixed capital in the form of furniture, vases, pestles and mortars, glasses, distillers, condensers and the like amounted to 65–70 percent.73

In the transport sector, one must distinguish between waterborne transport and overland transport, and for the latter between long-distance and local transport. In waterborne transport, boats and ships were fixed capital. In long-distance overland transportation until the sixteenth century, horses and mules were the predominant form of fixed capital employed – not until the second half of the sixteenth century were there enough roads to allow the extensive use of carts and carriages for long-distance travel. On the other hand, carts were used very early for local overland transport, especially for agricultural products. From whatever point of view one looks at things, fixed capital, in the form of draft animals, beasts of burden, ships, boats, carts and carriages, was not peripheral in transport services.

The thesis that fixed capital had a purely peripheral importance in the productive process before the Industrial Revolution is most valid for the manufacturing sector. As discussed above, when, in 1230–31 the Commune of Bologna invited a number of foreign artisans to set up manufactures of silk and wool, the city administration provided each artisan with a tiratorium worth 4 Bologna lire of the time and two looms worth 2 lire each. The fixed capital considered necessary for a productive unit was, therefore, valued at 8 lire. At the same time, the Commune loaned each artisan 50 lire for the expense of setting up and starting the plant, for raw materials and for the upkeep of his family. The artisans undertook to repay the 50-lire loan over a period of five years. This fact suggests that, under normal conditions, the fixed capital necessary to an enterprise, valued as we have seen at 8 lire, could be amortized in less than a year. Other examples of this kind can be easily assembled, but only with some qualifications. In the case of the textile manufactures of Bologna, the productive process was not entirely completed in the houses of the artisans. From an early date, mills were used for the fulling of cloth, and they represented a considerable investment in fixed capital. Over the centuries in Bologna itself, special mills were built for the manufacture of silk. By the seventeenth century these mills had reached an exceptional level of mechanical sophistication and represented an important investment. The mill set up in early eighteenth-century England by Sir Thomas Lombe in imitation of the Bologna silk mills consisted of 25,586 wheels and 97,746 pieces and could produce 73,726 yards of silk yarn for every revolution of the enormous driving wheel.74 In the mining sector, machines were needed for pumping water and for lifting and carrying ore; during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, this machinery often attained notable dimensions. In a lead mine in Poland about one hundred horses were employed to operate a pumping contraption, and in the second half of the sixteenth century 32 kilometers of galleries for drainage were excavated when the cost of excavating one kilometer equalled the price of about fifteen homes in the center of the mining town of Olkusz. In the shipbuilding sector, basins, docks, workshops, implements, and cranes represented considerable fixed capital. The Arsenal of Venice was deservedly famous throughout the later Middle Ages and the early modern periods for its size, its installations, and its stocks of materials. In England at the end of the seventeenth century, the fixed assets of Kentish shipyards at Chatham, Deptford, Woolwich, and Sheerness, were valued at about £76,000 (Table 2.18). If we accept Gregory King’s estimates of the English national income for 1688 (£43.5 million, according to Table 1.5) the sum of £76,000 was equivalent to almost 0.2 percent of the annual English national income.