Chapter 12

Establish Continuing Education

Abstract

Depending on the context of an incident or investigation, there can be a broad range of different people throughout the organization involved. Regardless, all staff throughout the organization must be trained based on their respective roles in the incident or investigation so that they have the knowledge necessary to perform their duties.

Keywords

Awareness; Certifications; Education; Specialization; TrainingThis chapter discusses the eighth step for implementing a digital forensic readiness program as the need to implement and ensure that stakeholders throughout the organizations are provided with continuous training and education to ensure they are knowledgeable in how they contribute to the success of the digital forensic readiness program. Based on the stakeholder’s respective role within the digital forensic readiness program, organizations must ensure that all individuals are properly and adequately trained so that they have the knowledge necessary to perform their duties.

Introduction

Organizations cannot implement an effective digital forensics readiness program without ensuring that all stakeholders involved have an adequate knowledge of how they contribute to its overall success. Once stakeholders have established how they contribute to digital forensics readiness, the level of educational training and professional knowledge required will vary for each individual.

Without proper training and education, the people factor, not technology, becomes the weakest link of a digital forensic readiness program. Knowing this, it is essential that organizations implement a comprehensive and well-designed program to ensure that all those who have any involvement with digital forensic readiness are knowledgeable and experienced.

Education and Training

Much like other components of a digital forensic readiness program, a successful education and training program also starts with the implementation of organizational governance that reflects the need for (1) informing stakeholders of their responsibilities, (2) providing the appropriate level of training and education, and (3) establishing processes for monitoring, reviewing, and improving their level of knowledge.

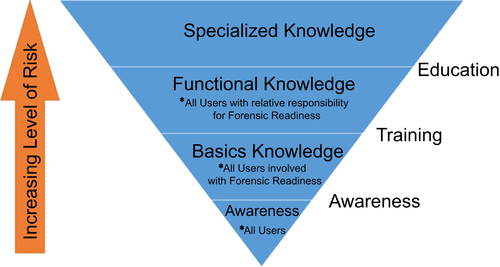

Having different education and awareness programs in place for all stakeholders, depending on their involvement, is an effective way of distributing information about the benefits and value of digital forensic readiness throughout the organization. Illustrated in Figure 12.1 below, the following sections describe the difference between awareness, training, and education curriculums that organizations should consider as part of their overall continuing education for digital forensic readiness program.

Within each education and training curriculum illustrated above, organizations must ensure that the information is adapted according to the stakeholder’s role (job function). As an example, a simplified concept for grouping the education and training information for applicable stakeholders has been placed into the following three categories:

• All personnel have a perspective that recognizes the importance of information security enough to positively contribute to the digital forensic readiness program.

• Functional/specialized roles emphasize the importance of performing their job duties to support the organizations digital forensic readiness program.

• Management needs to understand the functional, operational, and strategic value of the digital forensic readiness program so they can communicate and reinforce it throughout the organization.

Awareness

As the first stage of education and training, this general awareness is intended to change the behaviors of individuals and reinforce a culture of acceptable conduct. The objective here is not to provide users with in-depth or specialized knowledge, rather it is designed to provide stakeholders with the knowledge they need to recognize what the organization defines as unacceptable behavior and take the necessary steps from occurring.

With one of the business risk scenarios for implementing digital forensics readiness being to investigate employee misconduct against the organization’s policies, this type of education and training will reduce the likelihood that an incident will occur requiring a formal forensic investigation.

The information provided at this level is generic enough that it can be provided to all stakeholders without being adapted according to their job function. Examples of topics and subject areas that should be included as part of general awareness education and training includes, but is not limited to:

• Policies, standards, guidelines

• Social engineering (ie, phishing)

• Privileged access

• Data loss prevention

Organizations should consider making it a mandatory requirement that all stakeholders complete the general awareness program as part of their employment condition. At a minimum, organizations should require existing stakeholders to complete the general awareness education and training annually. Alternatively, when new stakeholders are identified they should be expected to complete the general awareness program immediately.

Basic Knowledge

As the next stage of education and training, the need for basic knowledge of digital forensic readiness provides stakeholders with the fundamental knowledge that is essential to ensuring they are competent. The distinction between basic knowledge and general awareness is that this level of education and training is designed to teach stakeholders the basic skills they will need to support a digital forensic readiness program.

The education and training provided at this level provides stakeholders with particular skill sets that continue to build off the foundations of the general awareness information. Creating in-house training courses can, for the most part, be designed to contain the same quality of information that could be obtained by enrolling in a formal college or university course.

The information provided at this level becomes more specific that it must be adapted to meet the knowledge required of each category of stakeholder. Examples of topics and subject areas that should be provided to each stakeholder group include, but are not limited to:

• Audit logging and retention

• Development life cycle security

• Incident handling and response

• Logical access controls

Completion of these basic knowledge courses can be positioned as either elective, where stakeholders can enroll themselves at their leisure to improve their professional development relating to digital forensic readiness, or mandatory, where stakeholders must complete the training in order to maintain their supporting role of digital forensics readiness.

Functional Knowledge

Taking education and training another level higher, there is a need for specific stakeholders to have a working and practical knowledge of the digital forensic discipline. Essentially, these individuals must have the skills and competencies necessary to ensure that digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques are upheld in support of the organization’s digital forensic readiness program.

Digital forensics requires individuals to have a significant amount of specialized training and skills to thoroughly understand and consistently follow the established scientific fundamentals. The information provided at this level of training is specific to the digital forensic discipline and requires stakeholders to have strong working and practical knowledge. Appendix B: Education and Professional Certifications provides a list of higher/postsecondary institutes that offer formal digital forensic education programs.

Professional Certification

Following completion of formalized education, there are several recognized industry associations that offer professional certifications in digital forensics. It is important to keep in mind that professional certifications are designed to test and evaluate an individual’s knowledge and experience; they do not provide individuals with in-depth training on digital forensics and information technology (IT) as obtained through formalized education. Professional certifications, or professional designations, provide assurance that an individual is qualified to perform digital forensics.

Appendix B: Education and Professional Certifications provides a list of higher/postsecondary institutes that offer formal digital forensic education programs as well as recognized industry associations offering digital forensic professional certifications.

Specialized Knowledge

It was not too long ago that digital forensics was considered niche and now if you practice digital forensics you are recognized as somewhat of a generalist in the discipline. However, with the continuing advancements in technology and how it is being used to support business operations, simply being a digital forensic generalist is no longer practical for most individuals.

Having gained the necessary functional knowledge, the next level of education and training is to become a specialist or professional in a particular subject area of digital forensics profession. For this reason, it is common for individuals to expand their knowledge of digital forensics and how it can be integrated and applied to other disciplines throughout the organization. The following are examples of areas where digital forensic specialization can be achieved:

• Cybercrime which emphasizes applying investigative techniques and methodologies of digital forensics to subject areas including, but not limited to, the following:

• Network forensics and analysis which relates to the monitoring and analysis of network traffic for the purposes of using it as digital evidence.

• Memory forensics which relates to the gathering and analysis of digital information as digital evidence contained within a system’s Random Access Memory (RAM).

• Cloud forensics which, as a subset of network forensics, relates to the gathering and analysis of digital information as digital evidence from cloud computing systems.

• Information assurance which emphasizes applying investigative techniques and methodologies of digital forensics to subject areas including, but not limited to, the following:

• Incident handling and response which relates to reducing business impact by managing the occurrence of computer security events; discussed further in chapter “Map Investigative Workflows.”

• Threat modeling builds appropriate countermeasures that effectively reduce business risk impact through the identification and understanding of individual security threats that have potential to affect business assets, operations, and functions; discussed further in Appendix H: Threat Modeling.

• Risk management is an examination of what, within the organization, could cause harm to assets so that an accurate decision of how to manage the risk can be made; discussed further in Appendix G: Risk Assessment.

• Security monitoring applies analytical techniques to identify unacceptable behavior patterns in the organization’s systems and assets to detect potential threats in a more effective and timely manner; discussed further in chapter “Enable Targeted Monitoring.”

Digital Forensic Roles

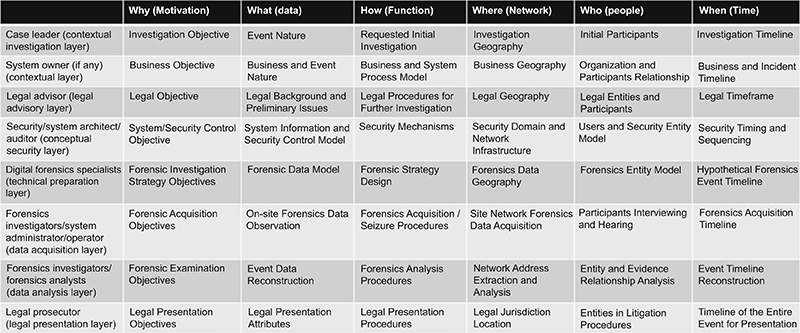

Illustrated in Figure 12.2, the FORZA—digital forensic investigation framework was developed as a mean of linking the multiple practitioner roles with the different procedures and processes they are responsible for throughout for the investigative workflow. Details on the roles described in the FORZA process model below have been described in Appendix A: Process Models.

Regardless of an individual’s role in the investigative workflow, there are different activities and steps performed that require either general or specialized knowledge in order to maintain digital evidence admissibility and credibility. It is essential that all persons involved, at any phases of the investigative workflow, diligently follow the rules of evidence and thoroughly apply digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques to all aspects of their work.

The need for distinct roles, as described by FORZA process model, is subjective to the overall size of the organization and the arrangement of the digital forensic team. For example, organizations that are smaller or localized to a specific geographic location might only employ a few individuals that are responsible for all aspects of digital forensics. Alternatively, organizations that are larger, distributed in geographic location, or have clearly defined structures might employ multiple individuals who are each responsible for a particular aspect of digital forensics.

In any case, what remains consistent is the need for individuals who have strong IT knowledge as well as formalized training of digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques. These are essential and fundamental to ensuring that the integrity, relevancy, and admissibility of digital evidence are maintained. While not comprehensive, the following roles are commonly employed in support of digital forensics:

• Forensic technicians gather, process, and handle evidence at the crime scene. These individuals need to be trained in proper handling techniques, such as the order of volatility discussed in chapter “Understanding Digital Forensics,” to ensure the authenticity and integrity of evidence is preserved for potential admissibility in a court of law.

• Forensic analysts or examiners, use forensic tools and investigative techniques to identify and, where needed, recover specific electronic information. Leveraging their technical skills, these individuals most often are the ones who are performing the work to process and analyze ESI as part of an investigation.

• Forensic investigators work with internal (ie, IT support teams) and external (ie, law enforcement agencies) entities to retrieve evidence relevant to the investigation. In some environments, these individuals might also perform the duties of both/either the forensic technician and the forensic analyst. It is important to note that in some jurisdiction, use of the term “investigator” requires individuals to hold a private investigator license that involves meeting a minimum requirement for both education and experience.

• Forensics managers oversee all actions and activities involving digital forensics. Within the scope of their organization’s digital forensic discipline, these individuals can be accountable for ensuring their organization’s digital forensic program continues to operate through activities such as leading a team, coordinating investigations and reporting, and ensuring the daily operations. Even though these individuals do not perform hands-on activities, it is expected that they are educated and knowledgeable of how digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques must be applied and followed.

While not typically a role within the digital forensic discipline, the terms specialist and professional are typically used to describe individuals who have been extensively trained, gained significant amounts of experience, and are recognized for their skills.

Balancing Business Versus Technical Learning

Those individuals who are directly involved with practicing digital forensics cannot solely rely on their technical education and training to support them through an investigation. While formal education is great and should be obtained where needed, there is a business side to digital forensics that must be accounted for and recognized as equally important as the technical skill sets. The following subject areas should be considered important to develop and continuously improve upon to be recognized as a digital forensic professional.

• Analytical skills are about extracting meaning and finding the hidden patterns and unexpected correlations among the masses of data. It is not about knowing everything; it is about identifying what is relevant and getting closer to the meaningful pieces of information. To do this requires that a level of objectivity is maintained throughout the investigation by setting aside personal and professional influences or biases to focus in on the facts.

• Communication and technical writing skills involve translating the technical techniques, methodologies, and findings into a natural language that can be effectively communicated across business, civil, or criminal court settings. This can be an overwhelming task for a technical individual who, depending on their level of experience, has had limited involvement in the business aspects of digital forensics. Further discussion on how to formulate evidence-based reports for communicating information about an investigation can be found in chapter “Maintain Evidence-based Reporting.”

• Time management and task prioritization are typically acquired through practical experience in dealing with investigations. Depending on the size and complexity of an investigation, there are certain processes and/or techniques that will produce results quickly or may take more time to execute. Deciding on the appropriate amount of time that will be required to complete the tasks is important to ensure that the investigation is not impact as a result of evidence being released or destroyed.

• Interpersonal skills are focused on building strategic relationships with key stakeholders to gain their confidence and cooperation. Regardless of whether the stakeholders are individuals with technical background, attorneys, or management, in the context of conducting an investigation there is a common goal to which everybody is striving to complete.

• Critical thinking can be developed through any number of workshops, sessions, or simulations using real-life case studies from a variety of security incidents. By analyzing real-life security incidents, skills can be obtained that are not focused on how to perform a task (ie, seizing evidence) but rather on how to identify relationships (ie, cause and effect).

Summary

Over the course of an investigation, there can be a wide range of individuals involved at any given time. Through the implementation of different levels of education and training programs, organizations can prepare stakeholders for the various roles they may play before, during, or after an investigation.