what is a case study?

what is a case study?Case studies |

CHAPTER 14 |

Case studies are important sources of research data, either on their own or to supplement other kinds of data. This chapter sets out key areas for attention in case studies, and it addresses:

what is a case study?

what is a case study?

generalization in case study

generalization in case study

reliability and validity in case studies

reliability and validity in case studies

what makes a good case study researcher?

what makes a good case study researcher?

examples of kinds of case study

examples of kinds of case study

why participant observation?

why participant observation?

planning a case study

planning a case study

data in case studies

data in case studies

recording observations

recording observations

writing up a case study

writing up a case study

The intention here is to provide researchers with an overview of key issues in the planning, conduct and reporting of a case study.

A case study is a specific instance that is frequently designed to illustrate a more general principle (Nisbet and Watt, 1984: 72), it is ‘the study of an instance in action’ (Adelman et al., 1980); it is the study of a ‘particular’ (Stake, 1995). Whilst Creswell (1994: 12) defines the case study as a single instance of a bounded system, such as a child, a clique, a class, a school, a community, others would not hold to such a tight defi-nition, for example Yin (2009: 18) argues that the boundary line between the phenomenon and its context is blurred, as a case study is a study of a case in a context and it is important to set the case within its context (i.e. rich descriptions and details are often a feature of a case study). A case study can be both: sometimes tightly bounded and other times less so; as Verschuren (2003: 123) argues, it is ambiguous.

A case study provides a unique example of real people in real situations, enabling readers to understand ideas more clearly than simply by presenting them with abstract theories or principles. Indeed a case study can enable readers to understand how ideas and abstract principles can fit together (Yin, 2009: 72–3). Case studies can penetrate situations in ways that are not always susceptible to numerical analysis.

Case studies recognize and accept that there are many variables operating in a single case, and, hence, to catch the implications of these variables usually requires more than one tool for data collection and many sources of evidence. Case studies can blend numerical and qualitative data, and they are a prototypical instance of mixed methods research (see Chapter 1); they can explain, describe, illustrate and enlighten (Yin, 2009: 19–20).

Verschuren (2003: 124) reports a range of authors who argue that a distinguishing feature of case study research is ‘holism’ rather than ‘reductionism’. Whilst for Yin (2009) ‘holism’ refers to conducting the research at the single ‘unit of analysis’ chosen (discussed below), which may be an individual, a group, an organization, etc., for Verschuren the term ‘holism’ is ambiguous, as it may not necessarily mean looking at a whole subject, person, group, organization but only at the relevant areas of interest.

Case studies can establish cause and effect (‘how’ and ‘why’); indeed one of their strengths is that they observe effects in real contexts, recognizing that context is a powerful determinant of both causes and effects, and that in- depth understanding is required to do justice to the case. As Nisbet and Watt (1984: 78) remark, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Sturman (1999: 103) argues that a distinguishing feature of case studies is that human systems have a wholeness or integrity to them rather than being a loose connection of traits, necessitating in- depth investigation. Further, contexts are unique and dynamic, hence case studies investigate and report the real-life, complex dynamic and unfolding interactions of events, human relationships and other factors in a unique instance. Hitchcock and Hughes (1995: 316) suggest that case studies are distinguished less by the methodologies that they employ than by the subjects/objects of their enquiry (though, as indicated below, there is frequently a resonance between case studies and interpretive methodologies). They further suggest (p. 322) that the case study approach is particularly valuable when the researcher has little control over events, i.e. behaviours cannot be manipulated or controlled. They consider (p. 317) that a case study has several hallmarks:

it is concerned with a rich and vivid description of events relevant to the case;

it is concerned with a rich and vivid description of events relevant to the case;

it provides a chronological narrative of events relevant to the case;

it provides a chronological narrative of events relevant to the case;

it blends a description of events with the analysis of them;

it blends a description of events with the analysis of them;

it focuses on individual actors or groups of actors, and seeks to understand their perceptions of events;

it focuses on individual actors or groups of actors, and seeks to understand their perceptions of events;

it highlights specific events that are relevant to the case;

it highlights specific events that are relevant to the case;

the researcher is integrally involved in the case, and the case study may be linked to the personality of the researcher (cf. Verschuren, 2003: 133);

the researcher is integrally involved in the case, and the case study may be linked to the personality of the researcher (cf. Verschuren, 2003: 133);

an attempt is made to portray the richness of the case in writing up the report.

an attempt is made to portray the richness of the case in writing up the report.

Case studies, they argue (Hitchcock and Hughes, 1995: 319): (a) are set in temporal, geographical, organizational, institutional and other contexts that enable boundaries to be drawn around the case; (b) can be defined with reference to characteristics defined by individuals and groups involved; and (c) can be defined by participants’ roles and functions in the case. They also point out that case studies:

will have temporal characteristics which help to define their nature;

will have temporal characteristics which help to define their nature;

have geographical parameters allowing for their definition;

have geographical parameters allowing for their definition;

will have boundaries which allow for definition;

will have boundaries which allow for definition;

may be defined by an individual in a particular context, at a point in time;

may be defined by an individual in a particular context, at a point in time;

may be defined by the characteristics of the group;

may be defined by the characteristics of the group;

may be defined by role or function;

may be defined by role or function;

may be shaped by organizational or institutional arrangements.

may be shaped by organizational or institutional arrangements.

Case studies have the advantage over historical studies of including direct observation and interviews with participants (Yin, 2009: 11). They strive to portray ‘what it is like’ to be in a particular situation, to catch the close- up reality and ‘thick description’ (Geertz, 1973) of participants’ lived experiences of, thoughts about and feelings for, a situation. They involve looking at a case or phenomenon in its real- life context, usually employing many types of data (Robson, 2002: 178). They are descriptive and detailed, with a narrow focus, and combining subjective and objective data (Dyer, 1995: 48–9). It is important in case studies for events and situations to be allowed to speak for themselves, rather than to be largely interpreted, evaluated or judged by the researcher. In this respect the case study is akin to the television documentary.

This is not to say that case studies are unsystematic or merely illustrative; case study data are gathered systematically and rigorously. Indeed Nisbet and Watt (1984: 91) specifically counsel case study researchers to avoid:

journalism (picking out more striking features of the case, thereby distorting the full account in order to emphasize these more sensational aspects);

journalism (picking out more striking features of the case, thereby distorting the full account in order to emphasize these more sensational aspects);

selective reporting (selecting only that evidence which will support a particular conclusion, thereby misrepresenting the whole case);

selective reporting (selecting only that evidence which will support a particular conclusion, thereby misrepresenting the whole case);

an anecdotal style (degenerating into an endless series of low- level banal and tedious illustrations that take over from in- depth, rigorous analysis); one is reminded of Stake’s (1978) wry comment that ‘our scrapbooks are full of enlargements of enlargements’, alluding to the tendency of some case studies to overemphasize detail to the detriment of seeing the whole picture;

an anecdotal style (degenerating into an endless series of low- level banal and tedious illustrations that take over from in- depth, rigorous analysis); one is reminded of Stake’s (1978) wry comment that ‘our scrapbooks are full of enlargements of enlargements’, alluding to the tendency of some case studies to overemphasize detail to the detriment of seeing the whole picture;

pomposity (striving to derive or generate profound theories from low- level data, or by wrapping up accounts in high- sounding verbiage);

pomposity (striving to derive or generate profound theories from low- level data, or by wrapping up accounts in high- sounding verbiage);

blandness (unquestioningly accepting only the respondents’ views, or only including those aspects of the case study on which people agree rather than areas on which they might disagree).

blandness (unquestioningly accepting only the respondents’ views, or only including those aspects of the case study on which people agree rather than areas on which they might disagree).

Simons (1996) has argued that case study needs to address six paradoxes; it needs to:

reject the subject–object dichotomy, regarding all participants equally;

reject the subject–object dichotomy, regarding all participants equally;

recognize the contribution that a genuine creative encounter can make to new forms of understanding education;

recognize the contribution that a genuine creative encounter can make to new forms of understanding education;

regard different ways of seeing as new ways of knowing;

regard different ways of seeing as new ways of knowing;

approximate the ways of the artist;

approximate the ways of the artist;

free the mind of traditional analysis;

free the mind of traditional analysis;

embrace these paradoxes, with an overriding interest in people.

embrace these paradoxes, with an overriding interest in people.

There are several types of case study. Yin (1984) identifies three such types in terms of their outcomes: (i) exploratory (as a pilot to other studies or research questions); (ii) descriptive (providing narrative accounts); (iii) explanatory (testing theories). Exploratory case studies that act as a pilot can be used to generate hypotheses that are tested in larger scale surveys, experiments or other forms of research, e.g. observational. However Adelman et al. (1980) caution against using case studies solely as preliminaries to other studies, e.g. as pre-experimental or pre-survey; rather, they argue, case studies exist in their own right as a significant and legitimate research method.

Yin’s (1984) classification accords with Merriam (1988) who identifies three types: (i) descriptive (narrative accounts); (ii) interpretive (developing conceptual categories inductively in order to examine initial assumptions); (iii) evaluative (explaining and judging). Merriam also categorizes four common domains or kinds of case study: ethnographic, historical, psychological and sociological. Sturman (1999: 107), echoing Stenhouse (1985), identifies four kinds of case study: (i) an ethnographic case study – single in- depth study; (ii) action research case study; (iii) evaluative case study; and (iv) educational case study. Stake (1994) identifies three main types of case study: (i) intrinsic case studies (studies that are undertaken in order to understand the particular case in question); (ii) instrumental case studies (examining a particular case in order to gain insight into an issue or a theory); (iii) collective case studies (groups of individual studies that are undertaken to gain a fuller picture). Because case studies provide fine grain detail they can also be used to complement other, more coarsely grained – often large- scale – kinds of research. Case study material in this sense can provide powerful human- scale data on macro- political decision making, fusing theory and practice, for example the work of Ball (1990), Bowe et al. (1992) and Ball (1994a) on the impact of government policy on specific schools.

Robson (2002: 181–2) suggests that there are: an individual case study; a set of individual case studies; a social group study; studies of organizations and institutions; studies of events, roles and relationships. All these, he argues, find expression in the case study method. He adds to these the distinction between a critical case study and an extreme or unique case. The former, he argues, is:

when your theoretical understanding is such that there is a clear, unambiguous and non- trivial set of circumstances where predicted outcomes will be found. Finding a case which fits, and demonstrating what has been predicted, can give a powerful boost to knowledge and understanding.

(Robson, 2002: 182)

One can add to the critical case study the issue that the case in question might possess all, or most of, the characteristics or features that one is investigating, more fully or distinctly than under ‘normal’ circumstances, for example a case study of student disruptive behaviour might go on in a very disruptive class, with students who are very seriously disturbed or challenging, rather than going into a class where the level of disruption is not so marked.

By contrast, Robson (2002: 182) argues that the extreme and the unique case can provide a valuable ‘test bed’. Extremes include, he argues, the situation in which ‘if it can work here it will work anywhere’, or choosing an ideal set of circumstances in which to try out a new approach or project, maybe to gain a fuller insight into how it operates before taking it to a wider audience (e.g. the research and development model).

Yin (2009: 46ff.) identifies four main case study designs:

1 The single- case design can focus on a critical case, an extreme case, a unique case, a representative or typical case, a revelatory case (an opportunity to research a case heretofore unresearched, e.g. Whyte’s Street Corner Society: see Chapter 11), a longitudinal case.

2 The embedded, single- case design, in which more than one ‘unit of analysis’ is incorporated into the design, e.g. a case study of a whole school might also use sub- units of classes, teachers, students, parents, and each of these might require different data collection instruments, e.g. a survey questionnaire, interviews, observations, etc.

3 The multiple- case design, e.g. comparative case studies within an overall piece of research, or replication case studies. Indeed Campbell (1975: 180), in arguing against single- case studies, suggests that having two case studies, for comparative purposes, is more than worth having double the amount of data on a single-case study! Here, for example, akin to a quasi- experiment, a regional education authority may want to see the effects of a new innovation, let us say in mathematics teaching, in three circumstances (conditions): one where teachers are given in-house staff development for the new mathematics, the other where they attend externally provided courses on the new mathematics, and the other where the teachers receive both kinds of staff development; here the case studies might look at the effects in the schools concerned (cf. Yin, 2009: 54–5).

4 The embedded multiple- case design, in which different sub- units may be involved in each of the different cases, and a range of instruments (e.g. a survey questionnaire, interviews, observations, archival records, etc.) might be used for each sub-unit, and each is kept separate to each case.

A single case may be part of a multiple- case study design, and, by contrast, a particular data collection instrument (e.g. a survey) may be part of a cross- site case study. In considering multiple case studies, it is important to decide how many are required; typically, the more subtle is the issue under investigation, the more cases might be required (Yin, 2009: 58) in order to be able to rule out rival explanations. Yin also counsels caution in conducting a single- case design, in that this overlooks the possible benefits of multiples cases, e.g. replication and the avoidance of the criticism of being a unique, single case, and the researcher is ‘putting all the eggs in one basket’, which may be risky: an ‘all- or-nothing’ risk.

Case studies have several claimed strengths and weaknesses. These are summarized in Box 14.1 (Adelman et al., 1980) and Box 14.2 (Nisbet and Watt, 1984).

Shaughnessy et al. (2003: 290–9) suggest that case studies often lack a high degree of control, and treatments are rarely controlled systematically, yet they are applied simultaneously, and with little control over extraneous variables. This, they argue, renders it diffi-cult to make inferences to draw cause and effect conclusions from case studies, and there is potential for bias in some case studies as the therapist is both the participant and observer and, in that role, may overstate or understate the case. Case studies, they argue, may be impressionistic, and self- reporting may be biased (by the participant or the observer). Further, they argue that bias may be a problem if the case study relies on an individual’s memory.

Dyer (1995: 50–2) remarks that, reading a case study, one has to be aware that a process of selection has already taken place, and only the author knows what has been selected in or out, and on what criteria, and, indeed, the participants themselves may not know what selection has taken place. Indeed he observes (pp. 48–9) that case studies combine knowledge and inference, and it is often difficult to separate these; the researcher has to be clear on which of these feature in the case study data.

BOX 14.1 POSSIBLE ADVANTAGES OF CASE STUDY

Case studies have a number of advantages that make them attractive to educational evaluators or researchers. Thus:

1 Case study data, paradoxically, is ‘strong in reality’ but difficult to organize. In contrast, other research data is often ‘weak in reality’ but susceptible to ready organization. This strength in reality is because case studies are down to earth and attention- holding, in harmony with the reader’s own experience, and thus provide a ‘natural’ basis for generalization.

2 Case studies allow generalizations either about an instance or from an instance to a class. Their peculiar strength lies in their attention to the subtlety and complexity of the case in its own right.

3 Case studies recognize the complexity and ‘embeddedness’ of social truths. By carefully attending to social situations, case studies can represent something of the discrepancies or conflicts between the viewpoints held by participants. The best case studies are capable of offering some support to alternative interpretations.

4 Case studies, considered as products, may form an archive of descriptive material sufficiently rich to admit subsequent reinterpretation. Given the variety and complexity of educational purposes and environments, there is an obvious value in having a data source for researchers and users whose purposes may be different from our own.

5 Case studies are ‘a step to action’. They begin in a world of action and contribute to it. Their insights may be directly interpreted and put to use; for staff or individual self- development, for within- institutional feedback; for formative evaluation; and in educational policy making.

6 Case studies present research or evaluation data in a more publicly accessible form than other kinds of research report, although this virtue is to some extent bought at the expense of their length. The language and the form of the presentation is hopefully less esoteric and less dependent on specialized interpretation than conventional research reports. The case study is capable of serving multiple audiences. It reduces the dependence of the reader upon unstated implicit assumptions . . . and makes the research process itself accessible. Case studies, therefore, may contribute towards the ‘democratization’ of decision making (and knowledge itself ). At its best, they allow readers to judge the implications of a study for themselves.

Source: Adapted from Adelman et al., 1980

BOX 14.2 NISBET’S AND WATT’S (1984) STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF CASE STUDY

Strengths

1 The results are more easily understood by a wide audience (including non- academics) as they are frequently written in everyday, non- professional language.

2 They are immediately intelligible; they speak for themselves.

3 They catch unique features that may otherwise be lost in larger scale data (e.g. surveys); these unique features might hold the key to understanding the situation.

4 They are strong on reality.

5 They provide insights into other, similar situations and cases, thereby assisting interpretation of other similar cases.

6 They can be undertaken by a single researcher without needing a full research team.

7 They can embrace and build in unanticipated events and uncontrolled variables.

Weaknesses

1 The results may not be generalizable except where other readers/researchers see their application.

2 They are not easily open to cross-checking, hence they may be selective, biased, personal and subjective.

3 They are prone to problems of observer bias, despite attempts made to address reflexivity.

From the preceding analysis it is clear that case studies frequently follow the interpretive tradition of research – seeing the situation through the eyes of participants – rather than the quantitative paradigm, though this need not always be the case. Its sympathy to the interpretive paradigm has rendered case study an object of criticism. Consider, for example, Smith (1991: 375) who argues that not only is the case study method the logically weakest method of knowing, but that studying individual cases, careers and communities is a thing of the past, and that attention should be focused on patterns and laws in historical research.

This is prejudice and ideology rather than critique, but signifies the problem of respectability and legitimacy that case study has to conquer amongst certain academics. Like other research methods, case study has to demonstrate reliability and validity. This can be dif-ficult, for given the uniqueness of any situation, a case study may be, by definition, inconsistent with other case studies or unable to demonstrate this positivist view of reliability. Even though case studies do not have to demonstrate this form of reliability, nevertheless there are important questions to be faced in undertaking case studies, for example (Adelman et al., 1980; Nisbet and Watt, 1984; Hitchcock and Hughes, 1995):

What exactly is a case?

How are cases identified and selected?

What kind of case study is this (what is its purpose)?

What is reliable evidence?

What is objective evidence?

What is an appropriate selection to include from the wealth of generated data?

What is a fair and accurate account?

Under what circumstances is it fair to take an exceptional case (or a critical event – see the discussion of observation in Chapter 23)?

What kind of sampling is most appropriate?

To what extent is triangulation required and how will this be addressed?

What is the nature of the validation process in case studies?

How will the balance be struck between uniqueness and generalization?

What is the most appropriate form of writing up and reporting the case study?

What ethical issues are exposed in undertaking a case study?

A key issue in case study research is the selection of information. Though it is frequently useful to record typical, representative occurrences, the researcher need not always adhere to criteria of representativeness. For example, it may be that infrequent, unrepresentative but critical incidents or events occur that are crucial to the understanding of the case. For example, a subject might only demonstrate a particular behaviour once, but it is so important as not to be ruled out simply because it occurred once; sometimes a single event might occur which sheds a hugely important insight into a person or situation (see the discussion of critical incidents in Chapter 29); it can be a key to understanding a situation (Flanagan, 1949).

For example, it may be that a psychological case study might happen upon a single instance of child abuse earlier in an adult’s life, but the effects of this were so profound as to constitute a turning point in understanding that adult. A child might suddenly pass a single comment that indicates complete frustration with or complete fear of a teacher, yet it is too important to overlook. Case studies, in not having to seek frequencies of occurrences, can replace quantity with quality and intensity, separating the significant few from the insignificant many instances of behaviour. Significance rather than frequency is a hallmark of case studies, offering the researcher an insight into the real dynamics of situations and people.

In designing a case study Yin (2009: 27) provides a valuable set of five components that need to be addressed:

The case study’s questions (it was suggested earlier that case study is particularly powerful in answering the ‘how’ and ‘why’ type of questions, and Yin (2009: 29) argues that the more specific are the questions that the case study should answer, the stronger is the likelihood of the case study staying on track and within limits).

The case study’s questions (it was suggested earlier that case study is particularly powerful in answering the ‘how’ and ‘why’ type of questions, and Yin (2009: 29) argues that the more specific are the questions that the case study should answer, the stronger is the likelihood of the case study staying on track and within limits).

The case study’s propositions (if there are any) (e.g. a hypothesis to be tested).

The case study’s propositions (if there are any) (e.g. a hypothesis to be tested).

The case study’s ‘unit(s) of analysis’ (this relates to the key issue in case study, which is defining what constitutes the case, and this can comprise an individual, a group, a community, an organization, a programme, a piece of innovation, a decision and its ramifications, an industry, an economy, etc.). What constitutes the case should be clear from the research questions that are asked (Yin, 2009: 30), as these should specify the ‘unit of analysis’. Yin (2009: 32) suggests that the ‘unit of analysis’ should be concrete (a real- life phenomenon) rather than abstract (e.g. an argument or topic). Identifying the ‘unit of analysis’ can be used to identify the tricky question of what constitutes a case. Verschuren (2003: 126) provides a neat example of this: in a case study of a single business organization in which a sample of 500 employees is taken, this does not constitute a case study but, rather, a survey, as the unit of analysis is each of the individual 500 employees. For it to be constituted as a case study the unit of analysis here would have to be the whole organization.

The case study’s ‘unit(s) of analysis’ (this relates to the key issue in case study, which is defining what constitutes the case, and this can comprise an individual, a group, a community, an organization, a programme, a piece of innovation, a decision and its ramifications, an industry, an economy, etc.). What constitutes the case should be clear from the research questions that are asked (Yin, 2009: 30), as these should specify the ‘unit of analysis’. Yin (2009: 32) suggests that the ‘unit of analysis’ should be concrete (a real- life phenomenon) rather than abstract (e.g. an argument or topic). Identifying the ‘unit of analysis’ can be used to identify the tricky question of what constitutes a case. Verschuren (2003: 126) provides a neat example of this: in a case study of a single business organization in which a sample of 500 employees is taken, this does not constitute a case study but, rather, a survey, as the unit of analysis is each of the individual 500 employees. For it to be constituted as a case study the unit of analysis here would have to be the whole organization.

The logic that links the data gathered to the propositions set out in the case study (i.e. how the data will be analysed, for example by looking for patterns, explanations, analysis of events as they unravel over time, cross- site and cross- case analysis (Yin, 2009: 34).

The logic that links the data gathered to the propositions set out in the case study (i.e. how the data will be analysed, for example by looking for patterns, explanations, analysis of events as they unravel over time, cross- site and cross- case analysis (Yin, 2009: 34).

The ‘criteria for interpreting the findings’ from the case study (which includes a clear indication of how the interpretation given is better than rival explanations of the data).

The ‘criteria for interpreting the findings’ from the case study (which includes a clear indication of how the interpretation given is better than rival explanations of the data).

Yin (2009: 35) also adds that theory generation should be included in the research design phase of the case study, as this assists in the focusing of the case study, and such theories might be of the behaviour of individuals, groups, organizations, communities, societies (e.g. there are several levels of theory).

It is often heard that case studies, being idiographic, have limited generalizability (e.g. Yin, 2009: 15). Of course, the same could be said of single experiments (p. 15). However, just as the generalizability of single experiments can be extended by replication and multiple experiments, so, too, case studies can be part of a growing pool of data, with multiple case studies contributing to greater generalizability. However, more pertinent is the claim by Robson (2002: 183) and Yin (2009: 15), that case studies opt for ‘analytic’ rather than ‘statistical’ generalization.

In statistical generalization the researcher seeks to move from a sample to a population, based on, for example, sampling strategies, frequencies, statistical significance and effect size. However, in analytic generalization, the concern is not so much for a representative sample (indeed the strength of the case study approach is that the case only represents itself ) so much as its ability to contribute to the expansion and generalization of theory (Yin, 2009: 15), which can help researchers to understand other similar cases, phenomena or situations, i.e. there is a logical rather than statistical connection between the case and the wider theory. A case is not a sample. Yin (2009: 43) makes the telling point that to assume that generalization is only from sample to population/universe is simply incorrect, irrelevant, inappropriate and inapplicable in respect of case studies. Rather, he makes the point (pp. 38–9) that case studies can help to generalize to a broader theory, in that the theory can be tested in one or more empirical cases (akin, in this respect, to a single experiment or quasi- experiment), and can be shown not to support rival, even if plausible, theories.

Generalization requires extrapolation, and the case study researcher, whilst not necessarily being able to extrapolate on the basis of typicality or representativeness, nevertheless can extrapolate to relevant theory (Macpherson et al., 2000: 52) and, by implication, to the testing of that theory.

Case studies can make theoretical statements, but, like other forms of research and human sciences, these must be supported by the evidence presented. This requires the nature of generalization in case study to be clarified. Generalization can take various forms, for example:

from the single instance to the class of instances that it represents (for example a single- sex selective school might act as a case study to catch significant features of other single- sex selective schools);

from the single instance to the class of instances that it represents (for example a single- sex selective school might act as a case study to catch significant features of other single- sex selective schools);

from features of the single case to a multiplicity of classes with the same features;

from features of the single case to a multiplicity of classes with the same features;

from the single features of part of the case to the whole of that case;

from the single features of part of the case to the whole of that case;

from a single case to a theoretical extension or theoretical generalization.

from a single case to a theoretical extension or theoretical generalization.

A more robust defence of generalization from case studies than those mentioned above is made by Verschuren (2003: 136). First he argues that statistical generalization is made on the basis of the homogeneity (or variability) of the population and the sample, together with the level of certainty required in the sample (see Chapter 8). So, for example, if the population is highly standardized and invariant (he uses the example of a factory that makes the same, uniform, standardized machines) the sample used for quality control could well be very small, whereas in a very variable population (with many variables) the sample size would have to be large. He then turns to the number of case studies which might be required for generalizability to be secure, and he argues that, in fact, a very small number of case studies could be used, each of which embraces the range of variables in question, thereby reducing the number of overall cases required; this is because ‘complex issues in general have a much lower variability than separate variables’ (p. 137), i.e. the researcher can generalize from a small number of case studies that represent the complex issues in general. It is a sophisticated argument: case studies include many variables; multi-variable phenomena are characterized by homogeneity rather than high variability; therefore if the researcher can identify case studies that catch the range of variability then external validity – generalizability – can be demonstrated.

Whilst case studies may not have the external checks and balances that other forms of research enjoy or require, nevertheless they still have to abide by canons of validity and reliability, for example:

construct validity (through employing accepted defi-nitions and constructions of concepts and terms; operationalizing the research and its measures/criteria acceptably);

construct validity (through employing accepted defi-nitions and constructions of concepts and terms; operationalizing the research and its measures/criteria acceptably);

internal validity (through ensuring agreements between different parts of the data, matching patterns of results, ensuring that findings and interpretations derive from the data transparently, and that causal explanations are supported by the evidence (alone), and that rival explanations and inferences have been weighed and found to be less acceptable than the explanation or inference made, again based on evidence);

internal validity (through ensuring agreements between different parts of the data, matching patterns of results, ensuring that findings and interpretations derive from the data transparently, and that causal explanations are supported by the evidence (alone), and that rival explanations and inferences have been weighed and found to be less acceptable than the explanation or inference made, again based on evidence);

external validity (clarifying the contexts, theory and domain to which generalization can be made);

external validity (clarifying the contexts, theory and domain to which generalization can be made);

concurrent validity (using multiple sources and kinds of evidence to address research questions and to yield convergent validity, e.g. triangulation of data, investigators, perspectives, methodologies, instruments);

concurrent validity (using multiple sources and kinds of evidence to address research questions and to yield convergent validity, e.g. triangulation of data, investigators, perspectives, methodologies, instruments);

ecological validity (fidelity to the special features of the context in which the study is located);

ecological validity (fidelity to the special features of the context in which the study is located);

reliability (replicability and internal consistency);

reliability (replicability and internal consistency);

avoidance of bias (e.g. the case study simply being an embodiment or fulfilment of the researcher’s initial prejudices or suspicions, with selective data being gathered or data being used selectively, i.e. a circular argument (Yin, 2009: 72), or with the researcher’s bias being inevitable if the researcher is a participant observer whose personality may affect the research process (Verschuren, 2003: 122). This can be addressed by reflexivity, respondent checks or checks by external reviewers of the data and inferences/conclusions drawn).

avoidance of bias (e.g. the case study simply being an embodiment or fulfilment of the researcher’s initial prejudices or suspicions, with selective data being gathered or data being used selectively, i.e. a circular argument (Yin, 2009: 72), or with the researcher’s bias being inevitable if the researcher is a participant observer whose personality may affect the research process (Verschuren, 2003: 122). This can be addressed by reflexivity, respondent checks or checks by external reviewers of the data and inferences/conclusions drawn).

Of note here is Yin’s (2009: 41, 122–4) call for a ‘chain of evidence’ to be provided, such that an external researcher could track through every step of the case study from its inception to its research questions, design, data sources, instrumentation, data (evidence and the circumstances in which they were collected, e.g. time, place and functional interconnections of people, places, etc.) and conclusions. It is important to note the time and place in which case study data are collected, as, not only are many actions and events context- specific and are part of a ‘thick description’, but this will enable any replication research to be planned (Macpherson et al., 2000: 56).

A case study requires in- depth data, a researcher’s ability to gather data that address fitness for purpose, and a researcher’s skills in probing beneath the surface of phenomena. These requirements imply that the researcher must be an effective questioner, listener (through many sources), prober, able to make informed inferences (‘to read between the lines’ (Yin, 2009: 70)) and adaptable to changing and emerging situations. Given that a case study uses a range of methods for data collection (e.g. observation, interview, artefacts, documents, survey), and that it may use different methodologies within it (e.g. action research, experiment, ethnography) the effective case study researcher must be versed in each of these, know how to draw on them at the most appropriate moment, able to keep a clear sense of direction in the data collection, so that the case study is kept on track rather than being side- tracked, and have a clear grasp of the issues for which the case study is being conducted (and keep to these). Clarity of focus, issues and direction are important elements here.

Further, the effective case study researcher will need to possess the ability to collate and synthesize data from different sources, to make inferences and interpretations based on evidence, to know how to test inferences and conclusions (and how to test them against rival explanations).

The case study researcher is often privy to confidential or sensitive material. Hence the researcher must be clear on: the ethics of the research; on his/her own stance in respect of disclosing private or sensitive data; how to protect people at risk or vulnerable groups; how to address matters of justified covert research; whether to report people anonymously or to identify them; how to address non-traceability and non-identifiability of participants, non-attributability of particular comments to individuals; and how to incorporate specific, important features into a cross- site analysis.

It is important for the case study researcher to have the subject knowledge and research expertise required to conduct the case study, to be highly prepared, to have a sense of realism about the situation being researched (as case study is a ‘real- life’ exercise), to be an excellent communicator (which may require training), and to have the appropriate personality characteristics that will enable access, empathy, rapport and trust to be built up with a diversity of participants. Not every researcher has all of these, yet each is vitally important.

Unlike the experimenter who manipulates variables to determine their causal significance or the surveyor who asks standardized questions of large, representative samples of individuals, the case study researcher typically observes the characteristics of an individual unit – a child, a clique, a class, a school or a community. The purpose of such observation is to probe deeply and to analyse intensively the multifarious phenomena that constitute the life cycle of the unit with a view to establishing generalizations about the wider population to which that unit belongs.

Antipathy amongst researchers towards the statistical- experimental paradigm has led to much case study research. Gangs (Patrick, 1973), dropouts (Parker, 1974), drug- users (Young, 1971) and schools (King, 1979) attest to the wide use of the case study in contemporary social science and educational research. Such wide use is marked by an equally diverse range of techniques employed in the collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data. Case studies are methodologically eclectic (i.e. embedded within them may be more than one kind of research such as ethnography, experiment, action research, survey, illuminative research, observational research, documentary research); they can use a range of methods of data collection, and indeed data types (quantitative and qualitative) and ways of analysing data (statistically and through qualitative tools), and they can be short term or long term. In short, case study is a hybrid (cf. Verschuren, 2003: 125). That said, at the heart of many case studies lies observation.

In Figure 14.1 we set out a typology of observation studies on the basis of which our six examples are selected. (For further explication of these examples, see the accompanying website.)

Acker’s (1990) study is an ethnographic account that is based on several hundred hours of participant observation material, whilst Boulton’s (1992) work, by contrast, is based on highly structured, non- participant observation conducted over five years. The study by Wild et al. (1992) used participant observation, loosely structured interviews that yielded simple frequency counts. Blease and Cohen’s (1990) study of coping with computers used highly structured observation schedules, undertaken by non- participant observers, with the express intention of obtaining precise, quantitative data on the classroom use of a computer program.

This was part of a longitudinal study in primary classrooms, and yielded typical profiles of individual behaviour and group interaction in students’ usage of the computer program. Antonsen’s (1988) study was of a single child undergoing psychotherapy at a Child Psychiatric Unit, and uses unstructured observation within the artificial setting of a psychiatric clinic and is a record of the therapist’s non- directive approach. Finally Houghton’s (1991) study uses data from structured sets of test materials together with focused interviews with those with whom an international student had contact. Together these case studies provide a valuable insight into the range and types of case study.

There are two principal types of observation – participant observation and non- participant observation. In the former, observers engage in the very activities they set out to observe. Often, their ‘cover’ is so complete that as far as the other participants are concerned, they are simply one of the group. In the case of Patrick, for example, born and bred in Glasgow, his researcher role remained hidden from the members of the Glasgow gang in whose activities he participated for a period of four months (see Patrick, 1973). Such complete anonymity is not always possible, however. Thus in Parker’s (1974) study of downtown Liverpool adolescents, it was generally known that the researcher was waiting to take up a post at the university. In the meantime, ‘knocking around’ during the day with the lads and frequenting their pub at night rapidly established that he was ‘OK’. The researcher was, in his own terms, ‘a drinker, a hanger- arounder’ who could be relied on to keep quiet in illegal matters.

Cover is not necessarily a prerequisite of participant observation. In an intensive study of a small group of working- class boys during their last two years at school and their first months in employment, Willis (1977) attended all the different subject classes at school – ‘not as a teacher, but as a member of the class’ – and worked alongside each boy in industry for a short period.

Non- participant observers, on the other hand, stand aloof from the group activities they are investigating and eschew group membership – no great difficulty for King (1979), an adult observer in infant classrooms. King recalls how he firmly established his non-participant status with young children by recognizing that they regarded any adult as another teacher or surrogate teacher. Hence he would stand up to maintain social distance, and deliberately decline to show immediate interest, and avoided eye contact.

The best illustration of the non- participant observer role is perhaps the case of the researcher sitting at the back of a classroom coding up every three seconds the verbal exchanges between teacher and pupils by means of a structured set of observational categories.

Often the type of observation undertaken by the researcher is associated with the type of setting in which the research takes place. In Figure 14.1 we identify a continuum of settings ranging from the ‘artificial’ environments of the counsellor’s and the therapist’s clinics (cells 5 and 6) to the ‘natural’ environments of school classrooms, staffrooms and playgrounds (cells 1 and 2). Because our continuum is crude and arbitrary we are at liberty to locate studies of an information technology audit and computer usage (cells 3 and 4) somewhere between the ‘artificial’ and the ‘natural’ poles.

Although in theory each of the six examples of case studies in Figure 14.1 could have been undertaken either as a participant or as a non- participant observation study, a number of factors intrude to make one or other of the observational strategies the dominant mode of enquiry in a particular type of setting. Bailey (1994: 247) explains that it is hard for a researcher who wishes to undertake covert research not to act as a participant in a natural setting, as, if the researcher does not appear to be participating, then why is he/she there? Hence, in many natural settings the researchers will be participants. This is in contrast to laboratory or artificial settings, in which non- participant observation (e.g. through video recording) may take place.

What we are saying is that the unstructured, ethnographic account of teachers’ work (cell 1) is the most typical method of observation in the natural surroundings of the school in which that study was conducted. Similarly, the structured inventories of study habits and personality employed in the study of Mr Chong (cell 6) reflect a common approach in the artificial setting of a counsellor’s office.

The natural scientist, Schutz (1962) points out, explores a field that means nothing to the molecules, atoms and electrons therein. By contrast, the subject matter of the world in which the educational researcher is interested is composed of people and is essentially meaningful to them. That world is subjectively structured, possessing particular meanings for its inhabitants. The task of the educational investigator is very often to explain the means by which an orderly social world is established and maintained in terms of its shared meanings. How do participant observation techniques assist the researcher in this task? Bailey (1994: 243–4) identifies some inherent advantages in the participant observation approach:

1 Observation studies are superior to experiments and surveys when data are being collected on non- verbal behaviour.

2 In observation studies, investigators are able to discern ongoing behaviour as it occurs and are able to make appropriate notes about its salient features.

3 Because case study observations take place over an extended period of time, researchers can develop more intimate and informal relationships with those they are observing, generally in more natural environments than those in which experiments and surveys are conducted.

4 Case study observations are less reactive than other types of data- gathering methods. For example, in laboratory- based experiments and in surveys that depend upon verbal responses to structured questions, bias can be introduced in the very data that researchers are attempting to study.

Further, direct observation is faithful to the real- life, in situ and holistic nature of a case study (Verschuren, 2003: 131).

In planning a case study there are several issues that researchers may find useful to consider (e.g. Adelman et al., 1980):

The particular circumstances of the case, including: (a) the possible disruption to individual participants that participation might entail; (b) negotiating access to people; (c) negotiating ownership of the data; (d) negotiating release of the data.

The particular circumstances of the case, including: (a) the possible disruption to individual participants that participation might entail; (b) negotiating access to people; (c) negotiating ownership of the data; (d) negotiating release of the data.

The conduct of the study including: (a) the use of primary and secondary sources; (b) the opportunities to check data; (c) triangulation (including peer examination of the findings, respondent validation and reflexivity); (d) data collection methods – in the interpretive paradigm case studies tend to use certain data collection methods, e.g. semi- structured and open interviews, observation, narrative accounts and documents, diaries, maybe also tests, rather than other methods, e.g. surveys, experiments. Nisbet and Watt (1984) suggest that, in conducting interviews, it may be wiser to interview senior people later rather than earlier so that the most effective use of discussion time can be made, the interviewer having been put into the picture fully before the interview; (e) data analysis and interpretation, and, where appropriate, theory generation; (f ) the writing of the report – Nisbet and Watt (1984) suggest that it is important to separate conclusions from the evidence, with the essential evidence included in the main text, and to balance illustration with analysis and generalization.

The conduct of the study including: (a) the use of primary and secondary sources; (b) the opportunities to check data; (c) triangulation (including peer examination of the findings, respondent validation and reflexivity); (d) data collection methods – in the interpretive paradigm case studies tend to use certain data collection methods, e.g. semi- structured and open interviews, observation, narrative accounts and documents, diaries, maybe also tests, rather than other methods, e.g. surveys, experiments. Nisbet and Watt (1984) suggest that, in conducting interviews, it may be wiser to interview senior people later rather than earlier so that the most effective use of discussion time can be made, the interviewer having been put into the picture fully before the interview; (e) data analysis and interpretation, and, where appropriate, theory generation; (f ) the writing of the report – Nisbet and Watt (1984) suggest that it is important to separate conclusions from the evidence, with the essential evidence included in the main text, and to balance illustration with analysis and generalization.

The consequences of the research (for participants). This might include the anonymizing of the research in order to protect participants, though such anonymization might suggest that a primary goal of case study is generalization rather than the portrayal of a unique case, i.e. it might go against a central feature of case study. Anonymizing reports might render them anodyne, and Adelman et al. (1980) suggest that the distortion that is involved in such anonymization – to render cases unrecognizable – might be too high a price to pay for going public.

The consequences of the research (for participants). This might include the anonymizing of the research in order to protect participants, though such anonymization might suggest that a primary goal of case study is generalization rather than the portrayal of a unique case, i.e. it might go against a central feature of case study. Anonymizing reports might render them anodyne, and Adelman et al. (1980) suggest that the distortion that is involved in such anonymization – to render cases unrecognizable – might be too high a price to pay for going public.

Nisbet and Watt (1984: 78) suggest three main stages in undertaking a case study. Because case studies catch the dynamics of unfolding situations it is advisable to commence with a very wide field of focus, an open phase, without selectivity or prejudgement. Thereafter progressive focusing enables a narrower field of focus to be established, identifying key foci for subsequent study and data collection. At the third stage a draft interpretation is prepared which needs to be checked with respondents before appearing in the final form. Nisbet and Watt (p. 79) advise against the generation of hypotheses too early in a case study; rather, they suggest, it is important to gather data openly. Respondent validation can be particularly useful as respondents might suggest a better way of expressing the issue or may wish to add or qualify points.

There is a risk in respondent validation, however, that they may disagree with an interpretation. Nisbet and Watt (1984: 81) indicate the need to have negotiated rights to veto. They also recommend that researchers: (a) promise that respondents can see those sections of the report that refer to them (subject to controls for confidentiality, e.g. of others in the case study); (b) take full account of suggestions and responses made by respondents and, where possible, to modify the account; (c) in the case of disagreement between researchers and respondents, promise to publish respondents’ comments and criticisms alongside the researchers’ report.

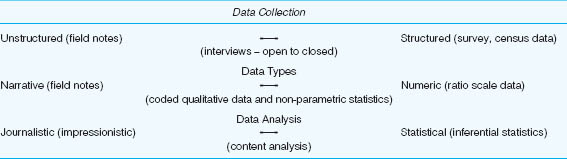

Sturman (1997) places on a set of continua the nature of data collection, types and analysis techniques in case study research. These are presented in summary form (Table 14.1).

At one pole we have unstructured, typically qualitative data, whilst at the other we have structured, typically quantitative data. Researchers using case study approaches will need to decide which methods of data collection, which type of data and techniques of analysis to employ.

We mentioned earlier that case studies are eclectic in the types of data that are used. Indeed many case studies will rely on mixed methods and a variety of data. Whilst observation and participant observation are often pre- eminent in case studies, they are by no means the only sources of data. For example Yin (2009: 101) identifies ‘six sources of evidence’:

Documents (p. 103): e.g. letters, emails, memo -randa, agendas, minutes, reports, records, diaries, notes, other studies, newspaper articles, website uploads, etc.

Documents (p. 103): e.g. letters, emails, memo -randa, agendas, minutes, reports, records, diaries, notes, other studies, newspaper articles, website uploads, etc.

Archival records (p. 105): e.g. public records, organizational records and reports, personal (maybe medical or behavioural) and personnel data stored in an organization (with due care to privacy legislation), charts and maps.

Archival records (p. 105): e.g. public records, organizational records and reports, personal (maybe medical or behavioural) and personnel data stored in an organization (with due care to privacy legislation), charts and maps.

Interviews (p. 106): in- depth, focused, and formal survey interviews (see Chapter 21).

Interviews (p. 106): in- depth, focused, and formal survey interviews (see Chapter 21).

Direct observation (p. 109): i.e. non- participant observation of the natural setting and the target individual(s): groups in situ, artefacts, rooms, décor, layout.

Direct observation (p. 109): i.e. non- participant observation of the natural setting and the target individual(s): groups in situ, artefacts, rooms, décor, layout.

Participant observation (p. 111): in which the researcher takes on a role in the situation or context featured in the case study.

Participant observation (p. 111): in which the researcher takes on a role in the situation or context featured in the case study.

Physical artefacts (p. 113): e.g. pictures, furniture, decorations, photographs, ornaments.

Physical artefacts (p. 113): e.g. pictures, furniture, decorations, photographs, ornaments.

True to the principle of mixed methods research, the multiple sources of evidence can provide convergent and concurrent validity on a case, and they demand of the researcher an ability to handle and synthesize many kinds of data simultaneously. This, in turn, advocates the compilation of a case study database of evidence (Yin, 2009: 118) that comprises two main kinds of collection: the actual data gathered, recorded and organized by entry, and the researcher’s ongoing analysis/report/comments/narrative on the data.

TABLE 14.1 CONTINUA OF DATA COLLECTION, TYPES AND ANALYSIS IN CASE STUDY RESEARCH

Source: Adapted from Sturman, 1997

Not only do the diverse data provide the evidence needed for the researcher to draw conclusions, but they provide the evidential ‘chain of evidence’ that gives credibility, reliability and validity to the case study (Yin, 2009: 122). When writing the report, the researcher must allude – by direct reference – to the actual evidence that supports the point being made, and it is to the writing of the case study report that we turn below.

The researcher gathers data; this is only one stage of the case study, as those data still have to be analysed. Whilst the analysis is the task of the researcher, there are several computer- assisted software tools that can process the data ready for analysis, for example NVivo, NUD*IST, Ethnograph, ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH. These can group, retrieve, organize and search single and multiple data sets, and return these ready for analysis and presentation in such forms as, for example (Miles and Huberman, 1984):

matrices and arrays of data;

matrices and arrays of data;

patterns, themes and configurations;

patterns, themes and configurations;

narratives;

narratives;

data displays;

data displays;

flowcharts;

flowcharts;

within- site and cross- site analyses;

within- site and cross- site analyses;

cause- and-effect diagrams and chains (e.g. where an effect becomes a subsequent cause);

cause- and-effect diagrams and chains (e.g. where an effect becomes a subsequent cause);

networks of relationships or linked events (i.e. rather than linear models of cause and effect (Morrison, 2009: chapter 7));

networks of relationships or linked events (i.e. rather than linear models of cause and effect (Morrison, 2009: chapter 7));

chronologies and causal sequences;

chronologies and causal sequences;

time- series and critical events;

time- series and critical events;

key issues and subordinate issues;

key issues and subordinate issues;

explanations;

explanations;

tabulations;

tabulations;

grounded theory.

grounded theory.

We return to these in Part 5. Yin (2009: 143) makes the point that the analysis of data is an iterative process, i.e. the researcher has to go back through the data several times to ensure that all the data fit the interpretations given or conclusions drawn, i.e. without unexplained anomalies or contradictions (the constant comparison method), that all the data are accounted for (p. 160), that rival interpretations are considered (p. 160) and that the significance features of the case are highlighted (p. 161).

I filled thirty- two notebooks with about half a million words of notes made during nearly six hundred hours [of observation].

(King, 1979)

The recording of observations is a frequent source of concern to inexperienced case study researchers. How much ought to be recorded? In what form should the recordings be made? What does one do with the mass of recorded data? Lofland (1971) gives a number of useful suggestions about collecting field notes:

Record the notes as quickly as possible after observation, since the quantity of information forgotten is very slight over a short period of time but accelerates quickly as more time passes.

Record the notes as quickly as possible after observation, since the quantity of information forgotten is very slight over a short period of time but accelerates quickly as more time passes.

Discipline yourself to write notes quickly and reconcile yourself to the fact that although it may seem ironic, recording of field notes can be expected to take as long as is spent in actual observation.

Discipline yourself to write notes quickly and reconcile yourself to the fact that although it may seem ironic, recording of field notes can be expected to take as long as is spent in actual observation.

Dictating rather than writing is acceptable if one can afford it, but writing has the advantage of stimulating thought.

Dictating rather than writing is acceptable if one can afford it, but writing has the advantage of stimulating thought.

Typing field notes is vastly preferable to handwriting because it is faster and easier to read, especially when making multiple copies.

Typing field notes is vastly preferable to handwriting because it is faster and easier to read, especially when making multiple copies.

It is advisable to make at least two copies of field notes and preferable to type on a master for reproduction. One original copy is retained for reference and other copies can be used as rough draught to be cut up, reorganized and rewritten.

It is advisable to make at least two copies of field notes and preferable to type on a master for reproduction. One original copy is retained for reference and other copies can be used as rough draught to be cut up, reorganized and rewritten.

The notes ought to be full enough adequately to summon up for one again, months later, a reasonably vivid picture of any described event. This probably means that one ought to be writing up, at the very minimum, at least a couple of single space typed pages for every hour of observation.

The notes ought to be full enough adequately to summon up for one again, months later, a reasonably vivid picture of any described event. This probably means that one ought to be writing up, at the very minimum, at least a couple of single space typed pages for every hour of observation.

The sort of note- taking recommended by Lofland (1971) and actually undertaken by King (1979) and Wolcott (1973) in their ethnographic accounts grows out of the nature of the unstructured observation study. Note- taking, confessed Wolcott, helped him fight the acute boredom that he sometimes felt when observing the interminable meetings that are the daily lot of the school principal. Occasionally, however, a series of events would occur so quickly that Wolcott had time only to make cursory notes which he supplemented later with fuller accounts. One useful tip from this experienced ethnographer is worth noting: never resume your observations until the notes from the preceding observation are complete. There is nothing to be gained merely by your presence as an observer. Until your observations and impressions from one visit are a matter of record, there is little point in returning to the classroom or school and reducing the impact of one set of events by superimposing another and more recent set. Indeed, when to record one’s data is but one of a number of practical problems identified by Walker, which are listed in Box 14.3 (Walker, 1980).

BOX 14.3 THE CASE STUDY AND PROBLEMS OF SELECTION

Among the issues confronting the researcher at the outset of his case study are the problems of selection. The following questions indicate some of the obstacles in this respect:

1 How do you get from the initial idea to the working design (from the idea to a specification, to usable data)?

2 What do you lose in the process?

3 What unwanted concerns do you take on board as a result?

4 How do you find a site which provides the best location for the design?

5 How do you locate, identify and approach key informants?

6 How they see you creates a context within which you see them. How can you handle such social complexities?

7 How do you record evidence? When? How much?

8 How do you file and categorize it?

9 How much time do you give to thinking and reflecting about what you are doing?

10 At what points do you show your subject what you are doing?

11 At what points do you give them control over who sees what?

12 Who sees the reports first?

Source: Adapted from Walker, 1980

The writing up of a case study abides by the twin notions of ‘fitness for purpose’ and ‘fitness for audience’. Robson (2002: 512–13) and Yin (2009: 176–9) suggests six forms of organizing the writing- up of a case study:

In the suspense structure the author presents the main findings (e.g. an executive summary) in the opening part of the report and then devotes the remainder of the report to providing evidence, analysis, explanations, justifications (e.g. for what is selected in or out, what conclusions are drawn, what alternative explanations are rejected) and argument that leads to the overall picture or conclusion.

In the suspense structure the author presents the main findings (e.g. an executive summary) in the opening part of the report and then devotes the remainder of the report to providing evidence, analysis, explanations, justifications (e.g. for what is selected in or out, what conclusions are drawn, what alternative explanations are rejected) and argument that leads to the overall picture or conclusion.

In the narrative report a prose account is provided, interspersed with relevant figures, tables, emergent issues, analysis and conclusion.

In the narrative report a prose account is provided, interspersed with relevant figures, tables, emergent issues, analysis and conclusion.

In the comparative structure the same case is examined through two or more lenses (e.g. explanatory, descriptive, theoretical) in order either to provide a rich, all- round account of the case, or to enable the reader to have sufficient information from which to judge which of the explanations, descriptions or theories best fit(s) the data.

In the comparative structure the same case is examined through two or more lenses (e.g. explanatory, descriptive, theoretical) in order either to provide a rich, all- round account of the case, or to enable the reader to have sufficient information from which to judge which of the explanations, descriptions or theories best fit(s) the data.

In the chronological structure a simple sequence or chronology is used as the organizational principle, thereby enabling not only cause and effect to be addressed, but also possessing the strength of an ongoing story. Adding to Robson’s comments, the chronology can be sectionalized as appropriate (e.g. key events or key time frames), and intersperse (a) commentaries on, (b) interpretations of and explanations for, and (c) summaries of, emerging issues as events unfold (e.g. akin to ‘memoing’ in ethnographic research). The chronology becomes an organizing principle, but different kinds of contents are included at each stage of the chronological sequence.

In the chronological structure a simple sequence or chronology is used as the organizational principle, thereby enabling not only cause and effect to be addressed, but also possessing the strength of an ongoing story. Adding to Robson’s comments, the chronology can be sectionalized as appropriate (e.g. key events or key time frames), and intersperse (a) commentaries on, (b) interpretations of and explanations for, and (c) summaries of, emerging issues as events unfold (e.g. akin to ‘memoing’ in ethnographic research). The chronology becomes an organizing principle, but different kinds of contents are included at each stage of the chronological sequence.

In the theory- generating structure, the structure follows a set of theoretical constructs or a case that is being made. Here, Robson suggests, each succeeding section of the case study contributes to, or constitutes, an element of a developing ‘theoretical formulation’, providing a link in the chain of argument, leading eventually to the overall theoretical formulation.

In the theory- generating structure, the structure follows a set of theoretical constructs or a case that is being made. Here, Robson suggests, each succeeding section of the case study contributes to, or constitutes, an element of a developing ‘theoretical formulation’, providing a link in the chain of argument, leading eventually to the overall theoretical formulation.

In the unsequenced structures the sequence, e.g. chronological, issue- based, event- based, theory based, is unimportant. Robson suggests that this approach renders it difficult for the reader to know which areas are important or unimportant, or whether there are any omissions. It risks the caprice of the writer.

In the unsequenced structures the sequence, e.g. chronological, issue- based, event- based, theory based, is unimportant. Robson suggests that this approach renders it difficult for the reader to know which areas are important or unimportant, or whether there are any omissions. It risks the caprice of the writer.

Some case studies are of a single situation – a single child, a single social group, a single class, a single school. Here any of the above six approaches may be appropriate. Some case studies require an unfolding of events, some case studies operate under a ‘snapshot’ approach (e.g. of several schools, or classes, or groups at a particular point in time). In the former it may be important to preserve the chronology, whereas in the latter such a chronology may be irrelevant. Some case studies are divided into two main parts (e.g. Willis, 1977): the data reporting and then the analysis/interpretation/explanation.

Yin (2009: 133) makes the important point that a case study report should consider rival explanations of the findings and indicate how the explanation adopted is better than its rivals. Such rival explanations might include, for example (cf. Yin, 2009: 135):

the role of chance/coincidence;

the role of chance/coincidence;

experimenter effects or situation effects (reactivity);

experimenter effects or situation effects (reactivity);

researcher bias;

researcher bias;

other influences on the case;

other influences on the case;

covariance or the influence of another variable, i.e. a cause other than the intervention or situation reported explains the effects;

covariance or the influence of another variable, i.e. a cause other than the intervention or situation reported explains the effects;

alternative explanations of what the data show;

alternative explanations of what the data show;

the process of the intervention, rather than its contents, explain the outcome;

the process of the intervention, rather than its contents, explain the outcome;

a different theory can explain the findings more fully and fittingly;

a different theory can explain the findings more fully and fittingly;

the intervention was part of a much bigger intervention that was already taking place at the time of the case study, so is subsumed by that bigger intervention;

the intervention was part of a much bigger intervention that was already taking place at the time of the case study, so is subsumed by that bigger intervention;

observed changes might have happened anyway, without the intervention from the case study.

observed changes might have happened anyway, without the intervention from the case study.

The different strategies we have illustrated in our six examples of case studies in a variety of educational settings suggest that participant observation is best thought of as a generic term that describes a methodological approach rather than one specific method.1 What our examples have shown is that the representativeness of a particular sample often relates to the observational strategy open to the researcher. Generally speaking, the larger the sample, the more representative it is, and the more likely that the observer’s role is of a participant nature.

Macpherson et al. (2000: 57–8) set out several principles to guide the practice of case study research. With regard to purpose, they suggest a collaborative approach between participants and researcher in order to address contextuality. With regard to place, they suggest sensitivity to the place (akin to ecological validity). With regard to both purpose and process, they suggest authenticity (fitness for purpose), applicability (thinking large but starting small) and growth (ensuring development and social transformation). With regard to product, they suggest communicability of the findings through networking (which they also apply to purpose and process).

Yin (2009: 185–9) suggests that an ‘exemplary’ case study must be ‘significant’, ‘complete’, considering of ‘alternative perspectives’, careful to include ‘sufficient evidence’ and ‘engaging’. These precepts, surely, can provide a useful guide for researchers.

For examples of case studies, see, for example, Macpherson et al.’s (2000) study of schooling in Australia, and the accompanying website.

Companion Website

Companion WebsiteThe companion website to the book includes PowerPoint slides for this chapter, which list the structure of the chapter and then provide a summary of the key points in each of its sections. In addition there is further information in the form of case study examples. These resources can be found online at www.routledge.com/textbooks/cohen7e.