foundations of naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic enquiry (theoretical bases of these kinds of research)

foundations of naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic enquiry (theoretical bases of these kinds of research)Naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic research |

CHAPTER 11 |

The title of this chapter indicates that a wide range of types and kinds of qualitative research are addressed here. The chapter addresses several key issues in planning and conducting qualitative research:

foundations of naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic enquiry (theoretical bases of these kinds of research)

foundations of naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic enquiry (theoretical bases of these kinds of research)

planning naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic research

planning naturalistic, qualitative and ethnographic research

features and stages of a qualitative study

features and stages of a qualitative study

critical ethnography

critical ethnography

some problems with ethnographic and naturalistic approaches

some problems with ethnographic and naturalistic approaches

There is no single blueprint for naturalistic, qualitative or ethnographic research, because there is no single picture of the world. Rather, there are many worlds and many ways of investigating them. In this chapter we set out a range of key issues in understanding these worlds. It is important to stress, at the outset, that, though there are many similarities and overlaps between naturalistic/ethnographic and qualitative methods, there are also differences between them. Here the former connotes long-term residence with an individual, group or specific community (cf. Swain, 2006: 206), whilst the latter, often being concerned with the nature of the data and the kinds of research question to be answered, is an approach that need not require naturalistic approaches or principles. That said, there are sufficient areas of commonality to render it appropriate to consider them in the same chapter, and we will tease out differences between them where relevant. The intention of this chapter is to provide guidance for qualitative researchers who are conducting either long-term ethnographic research or small-scale, short-term qualitative research.

There are many varieties of qualitative research, indeed Preissle (2006: 686) remarks that qualitative researchers cannot agree on the purposes of qualitative research, its boundaries and its disciplinary fields, or, indeed, its terminology (‘interpretive’, ‘naturalistic’, ‘qualitative’, ‘ethnographic’, ‘phenomenological’, etc.). However, she does indicate that qualitative research is characterized by a ‘loosely defined’ group of designs that elicit verbal, aural, observational, tactile, gustatory and olfactory information from a range of sources including, amongst others, audio, film, documents and pictures, and that it draws strongly on direct experience and meanings, and that these may vary according to the style of qualitative research undertaken.

Qualitative research provides an in-depth, intricate and detailed understanding of meanings, actions, non-observable as well as observable phenomena, attitudes, intentions and behaviours, and these are well served by naturalistic enquiry (Gonzales et al., 2008: 3). It gives voices to participants, and probes issues that lie beneath the surface of presenting behaviours and actions.

The social and educational world is a messy place, full of contradictions, richness, complexity, connectedness, conjunctions and disjunctions. It is multilayered, and not easily susceptible to the atomization process inherent in much numerical research. It has to be studied in total rather than in fragments if a true understanding is to be reached. Chapter 1 indicated that several approaches to educational research are contained in the paradigm of qualitative, naturalistic and ethnographic research. The characteristics of that paradigm (Boas, 1943; Blumer, 1969; Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Woods, 1992; LeCompte and Preissle, 1993) include:

humans actively construct their own meanings of situations;

humans actively construct their own meanings of situations;

meaning arises out of social situations and is handled through interpretive processes;

meaning arises out of social situations and is handled through interpretive processes;

behaviour and, thereby, data are socially situated, context-related, context-dependent and context-rich. To understand a situation researchers need to understand the context because situations affect behaviour and perspectives and vice versa;

behaviour and, thereby, data are socially situated, context-related, context-dependent and context-rich. To understand a situation researchers need to understand the context because situations affect behaviour and perspectives and vice versa;

realities are multiple, constructed and holistic;

realities are multiple, constructed and holistic;

knower and known are interactive, inseparable;

knower and known are interactive, inseparable;

only time-and context-bound working hypotheses (idiographic statements) are possible;

only time-and context-bound working hypotheses (idiographic statements) are possible;

all entities are in a state of mutual simultaneous shaping, so that it is impossible to distinguish causes from effects;

all entities are in a state of mutual simultaneous shaping, so that it is impossible to distinguish causes from effects;

enquiry is value-bound:

enquiry is value-bound:

enquiries are influenced by enquirer values as expressed in the choice of a problem, evaluand or policy option, and in the framing, bounding and focusing of that problem, evaluand or policy option;

enquiries are influenced by enquirer values as expressed in the choice of a problem, evaluand or policy option, and in the framing, bounding and focusing of that problem, evaluand or policy option;

enquiry is influenced by the choice of the paradigm that guides the investigation into the problem;

enquiry is influenced by the choice of the paradigm that guides the investigation into the problem;

enquiry is influenced by the choice of the substantive theory utilized to guide the collection and analysis of data and in the interpretation of findings;

enquiry is influenced by the choice of the substantive theory utilized to guide the collection and analysis of data and in the interpretation of findings;

enquiry is influenced by the values that inhere in the context;

enquiry is influenced by the values that inhere in the context;

enquiry is either value-resident (reinforcing or congruent) or value-dissonant (conflicting). Problem, evaluand or policy option, paradigm, theory and context must exhibit congruence (value-resonance) if the enquiry is to produce meaningful results;

enquiry is either value-resident (reinforcing or congruent) or value-dissonant (conflicting). Problem, evaluand or policy option, paradigm, theory and context must exhibit congruence (value-resonance) if the enquiry is to produce meaningful results;

research must include ‘thick descriptions’ (Geertz, 1973) of the contextualized behaviour; for descriptions to be ‘thick’ requires inclusion not only of detailed observational data but data on meanings, participants’ interpretations of situations and unobserved factors;

research must include ‘thick descriptions’ (Geertz, 1973) of the contextualized behaviour; for descriptions to be ‘thick’ requires inclusion not only of detailed observational data but data on meanings, participants’ interpretations of situations and unobserved factors;

the attribution of meaning is continuous and evolving over time;

the attribution of meaning is continuous and evolving over time;

people are deliberate, intentional and creative in their actions;

people are deliberate, intentional and creative in their actions;

history and biography intersect – we create our own futures but not necessarily in situations of our own choosing;

history and biography intersect – we create our own futures but not necessarily in situations of our own choosing;

social research needs to examine situations through the eyes of the participants – the task of ethnographies, as Malinowski (1922: 25) observed, is to grasp the point of view of the native [sic], his [sic] view of the world and in relation to his life;

social research needs to examine situations through the eyes of the participants – the task of ethnographies, as Malinowski (1922: 25) observed, is to grasp the point of view of the native [sic], his [sic] view of the world and in relation to his life;

researchers are the instruments of the research (Eisner, 1991);

researchers are the instruments of the research (Eisner, 1991);

researchers generate rather than test hypotheses;

researchers generate rather than test hypotheses;

researchers do not know in advance what they will see or what they will look for;

researchers do not know in advance what they will see or what they will look for;

humans are anticipatory beings;

humans are anticipatory beings;

human phenomena seem to require even more conditional stipulations than do other kinds;

human phenomena seem to require even more conditional stipulations than do other kinds;

meanings and understandings replace proof;

meanings and understandings replace proof;

generalizability is interpreted as generalizability to identifiable, specific settings and subjects rather than universally;

generalizability is interpreted as generalizability to identifiable, specific settings and subjects rather than universally;

situations are unique;

situations are unique;

the processes of research and behaviour are as important as the outcomes;

the processes of research and behaviour are as important as the outcomes;

people, situations, events and objects have meaning conferred upon them rather than possessing their own intrinsic meaning;

people, situations, events and objects have meaning conferred upon them rather than possessing their own intrinsic meaning;

social research should be conducted in natural, uncontrived, real-world settings with as little intrusiveness as possible by the researcher;

social research should be conducted in natural, uncontrived, real-world settings with as little intrusiveness as possible by the researcher;

social reality, experiences and social phenomena are capable of multiple, sometimes contradictory interpretations and are available to us through social interaction;

social reality, experiences and social phenomena are capable of multiple, sometimes contradictory interpretations and are available to us through social interaction;

all factors, rather than a limited number of variables, have to be taken into account;

all factors, rather than a limited number of variables, have to be taken into account;

data are analysed inductively, with constructs deriving from the data during the research;

data are analysed inductively, with constructs deriving from the data during the research;

theory generation is derivative – grounded (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) – the data suggest the theory rather than vice versa.

theory generation is derivative – grounded (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) – the data suggest the theory rather than vice versa.

Lincoln and Guba (1985: 39–43) tease out the implications of these axioms:

studies must be set in their natural settings as context is heavily implicated in meaning;

studies must be set in their natural settings as context is heavily implicated in meaning;

humans are the research instrument;

humans are the research instrument;

utilization of tacit knowledge is inescapable;

utilization of tacit knowledge is inescapable;

qualitative methods sit more comfortably than quantitative methods with the notion of the human-as-instrument;

qualitative methods sit more comfortably than quantitative methods with the notion of the human-as-instrument;

purposive sampling enables the full scope of issues to be explored;

purposive sampling enables the full scope of issues to be explored;

data analysis is inductive rather than a priori and deductive;

data analysis is inductive rather than a priori and deductive;

theory emerges rather than is pre-ordinate. A priori theory is replaced by grounded theory;

theory emerges rather than is pre-ordinate. A priori theory is replaced by grounded theory;

research designs emerge over time (and as the sampling changes over time);

research designs emerge over time (and as the sampling changes over time);

the outcomes of the research are negotiated;

the outcomes of the research are negotiated;

the natural mode of reporting is the case study;

the natural mode of reporting is the case study;

nomothetic interpretation is replaced by idiographic interpretation;

nomothetic interpretation is replaced by idiographic interpretation;

applications are tentative and pragmatic;

applications are tentative and pragmatic;

the focus of the study determines its boundaries;

the focus of the study determines its boundaries;

trustworthiness and its components replace more conventional views of reliability and validity.

trustworthiness and its components replace more conventional views of reliability and validity.

Qualitative research can be used in systematic reviews (Dixon-Woods et al., 2001) to:

identify and refine questions, fields, foci and topics of the review, i.e. to act as a precursor to a full review;

identify and refine questions, fields, foci and topics of the review, i.e. to act as a precursor to a full review;

provide data in their own right for a research synthesis;

provide data in their own right for a research synthesis;

indicate and identify the outcomes that are of interest, and for whom;

indicate and identify the outcomes that are of interest, and for whom;

complement and augment data from quantitative reviews;

complement and augment data from quantitative reviews;

fill out any gaps in quantitative reviews;

fill out any gaps in quantitative reviews;

explain the findings from quantitative reviews and data;

explain the findings from quantitative reviews and data;

provide alternative perspectives on topics;

provide alternative perspectives on topics;

contribute to the drawing of conclusions from the review;

contribute to the drawing of conclusions from the review;

be part of a multi-methods research synthesis;

be part of a multi-methods research synthesis;

suggest how to turn evidence into practice.

suggest how to turn evidence into practice.

Whilst the lack of controls in much qualitative research renders it perhaps unattractive for research syntheses, this is perhaps unjustified, as it suggests that qualitative research has to abide by the rules of the game of quantitative approaches. Qualitative methods have their own tenets, and these complement very well those of numerical research. As with quantitative studies, qualitative studies have to be weighted, downgraded, upgraded or excluded according to the quality of the evidence and sampling that they contain. They also have to overcome the problem that, by stripping out the context in order to obtain themes and key concepts, they destroy the heart of qualitative research – context (Dixon-Woods et al., 2001: 131).

LeCompte and Preissle (1993) suggest that ethnographic research is a process involving methods of enquiry, an outcome and a resultant record of the enquiry. The intention of the research is to create as vivid a reconstruction as possible of the culture or groups being studied (p. 235). There are several purposes of qualitative research, for example, description and reporting, the creation of key concepts, theory generation and testing. LeCompte and Preissle (1993) indicate several key elements of ethnographic approaches:

phenomenological data are elicited (p. 3);

phenomenological data are elicited (p. 3);

the world view of the participants is investigated and represented – their ‘definition of the situation’ (Thomas, 1923);

the world view of the participants is investigated and represented – their ‘definition of the situation’ (Thomas, 1923);

meanings are accorded to phenomena by both the researcher and the participants; the process of research therefore is hermeneutic, uncovering meanings (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 31–2);

meanings are accorded to phenomena by both the researcher and the participants; the process of research therefore is hermeneutic, uncovering meanings (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 31–2);

the constructs of the participants are used to structure the investigation;

the constructs of the participants are used to structure the investigation;

empirical data are gather in their naturalistic setting (unlike laboratories or in controlled settings as in other forms of research where variables are manipulated);

empirical data are gather in their naturalistic setting (unlike laboratories or in controlled settings as in other forms of research where variables are manipulated);

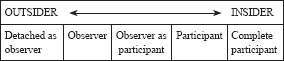

observational techniques are used extensively (both participant and non-participant) to acquire data on real-life settings;

observational techniques are used extensively (both participant and non-participant) to acquire data on real-life settings;

the research is holistic, that is, it seeks a description and interpretation of ‘total phenomena’;

the research is holistic, that is, it seeks a description and interpretation of ‘total phenomena’;

there is a move from description and data to inference, explanation, suggestions of causation and theory generation;

there is a move from description and data to inference, explanation, suggestions of causation and theory generation;

methods are ‘multimodal’ and the ethnographer is a ‘methodological omnivore’ (p. 232).

methods are ‘multimodal’ and the ethnographer is a ‘methodological omnivore’ (p. 232).

Hitchcock and Hughes (1989: 52–3) suggest that ethnographies involve:

the production of descriptive cultural knowledge of a group;

the production of descriptive cultural knowledge of a group;

the description of activities in relation to a particular cultural context from the point of view of the members of that group themselves;

the description of activities in relation to a particular cultural context from the point of view of the members of that group themselves;

the production of a list of features constitutive of membership in a group or culture;

the production of a list of features constitutive of membership in a group or culture;

the description and analysis of patterns of social interaction;

the description and analysis of patterns of social interaction;

the provision as far as possible of ‘insider accounts’;

the provision as far as possible of ‘insider accounts’;

the development of theory.

the development of theory.

Lofland (1971) suggests that naturalistic methods are intended to address three major questions:

What are the characteristics of a social phenomenon?

What are the characteristics of a social phenomenon?

What are the causes of the social phenomenon?

What are the causes of the social phenomenon?

What are the consequences of the social phenomenon?

What are the consequences of the social phenomenon?

In this one can observe: (a) the environment; (b) people and their relationships; (c) behaviour, actions and activities; (d) verbal behaviour; (e) psychological stances; (f ) histories; (g) physical objects (Baker, 1994: 241–4).

There are several key differences between the naturalistic approach and that of the positivists to whom we made reference in Chapter 1. LeCompte and Preissle (1993: 39–44) suggest that ethnographic approaches are concerned more with description rather than prediction, induction rather than deduction, generation rather than verification of theory, construction rather than enumeration, and subjectivities rather than objective knowledge. With regard to the latter the authors distinguish between emic approaches (as in the term ‘phonemic’, where the concern is to catch the subjective meanings placed on situations by participants) and etic approaches (as in the term ‘phonetic’, where the intention is to identify and understand the objective or researcher’s meaning and constructions of a situation) (p. 45).

Woods (1992), however, argues that some differences between quantitative and qualitative research have been exaggerated. He proposes, for example (p. 381), that the 1970s witnessed an unproductive dichotomy between the two, the former being seen as strictly in the hypothetico-deductive mode (testing theories) and the latter being seen as the inductive method used for generating theory. He suggests that the epistemological contrast between the two is overstated, as qualitative techniques can be used both for generating and testing theories.

Indeed Dobbert and Kurth-Schai (1992) urge that ethnographic approaches become not only more systematic but that they study and address regularities in social behaviour and social structure (pp. 94–5). The task of ethnographers is to balance a commitment to catch the diversity, variability, creativity, individuality, uniqueness and spontaneity of social interactions (e.g. by ‘thick descriptions’ (Geertz, 1973)) with a commitment to the task of social science to seek regularities, order and patterns within such diversity (Dobbert and Kurth-Schai, 1992: 150). As Durkheim (1982) noted, there are ‘social facts’.

Following this line, it is possible, therefore, to suggest that ethnographic research can address issues of generalizability – a tenet of positivist research – interpreted as ‘comparability’ and ‘translatability’ (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 47). For comparability the characteristics of the group that is being studied need to be made explicit so that readers can compare them with other similar or dissimilar groups. For translatability the analytic categories used in the research as well as the characteristics of the groups are made explicit so that meaningful comparisons can be made to other groups and disciplines.

Spindler and Spindler (1992: 72–4) put forward several hallmarks of effective ethnographies:

Observations have contextual relevance, both in the immediate setting in which behaviour is observed and in further contexts beyond.

Observations have contextual relevance, both in the immediate setting in which behaviour is observed and in further contexts beyond.

Hypotheses emerge in situ as the study develops in the observed setting.

Hypotheses emerge in situ as the study develops in the observed setting.

Observation is prolonged and often repetitive. Events and series of events are observed more than once to establish reliability in the observational data.

Observation is prolonged and often repetitive. Events and series of events are observed more than once to establish reliability in the observational data.

Inferences from observation and various forms of ethnographic enquiry are used to address insiders’ views of reality.

Inferences from observation and various forms of ethnographic enquiry are used to address insiders’ views of reality.

A major part of the ethnographic task is to elicit sociocultural knowledge from participants, rendering social behaviour comprehensible.

A major part of the ethnographic task is to elicit sociocultural knowledge from participants, rendering social behaviour comprehensible.

Instruments, schedules, codes, agenda for interviews, questionnaires, etc. should be generated in situ, and should derive from observation and ethnographic enquiry.

Instruments, schedules, codes, agenda for interviews, questionnaires, etc. should be generated in situ, and should derive from observation and ethnographic enquiry.

A transcultural, comparative perspective is usually present, although often it is an unstated assumption, and cultural variation (over space and time) is natural.

A transcultural, comparative perspective is usually present, although often it is an unstated assumption, and cultural variation (over space and time) is natural.

Some sociocultural knowledge that affects behaviour and communication under study is tacit/implicit, and may not be known even to participants or known ambiguously to others. It follows that one task for an ethnography is to make explicit to readers what is tacit/implicit to informants.

Some sociocultural knowledge that affects behaviour and communication under study is tacit/implicit, and may not be known even to participants or known ambiguously to others. It follows that one task for an ethnography is to make explicit to readers what is tacit/implicit to informants.

The ethnographic interviewer should not frame or predetermine responses by the kinds of questions that are asked, because the informants themselves have the emic, native cultural knowledge.

The ethnographic interviewer should not frame or predetermine responses by the kinds of questions that are asked, because the informants themselves have the emic, native cultural knowledge.

In order to collect as much live data as possible, any technical device may be used.

In order to collect as much live data as possible, any technical device may be used.

The ethnographer’s presence should be declared and his or her personal, social and interactional position in the situation should be described.

The ethnographer’s presence should be declared and his or her personal, social and interactional position in the situation should be described.

With ‘mutual shaping and interaction’ between the researcher and participants taking place (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 155) the researcher becomes, as it were, the ‘human instrument’ in the research (p. 187), building on her tacit knowledge in addition to her propositional knowledge, using methods that sit comfortably with human enquiry, e.g. observations, interviews, documentary analysis and ‘unobtrusive’ methods (p. 187). The advantage of the ‘human instrument’ is her adaptability, responsiveness, knowledge, ability to handle sensitive matters, ability to see the whole picture, ability to clarify and summarize, to explore, to analyse, to examine atypical or idiosyncratic responses (pp. 193–4).

The main kinds of naturalistic enquiry are (Arsenault and Anderson, 1998: 121; Flick, 2004a, 2004b):

case study (an investigation into a specific instance or phenomenon in its real-life context);

case study (an investigation into a specific instance or phenomenon in its real-life context);

comparative studies (where several cases are compared on the basis of key areas of interest);

comparative studies (where several cases are compared on the basis of key areas of interest);

retrospective studies (which focus on biographies of participants or which ask participants to look back on events and issues);

retrospective studies (which focus on biographies of participants or which ask participants to look back on events and issues);

snapshots (analyses of particular situations, events or phenomena at a single point in time);

snapshots (analyses of particular situations, events or phenomena at a single point in time);

longitudinal studies (which investigate issues or people over time);

longitudinal studies (which investigate issues or people over time);

ethnography (a portrayal and explanation of social groups and situations in their real-life contexts);

ethnography (a portrayal and explanation of social groups and situations in their real-life contexts);

grounded theory (developing theories to explain phenomena, the theories emerging from the data rather than being prefigured or predetermined);

grounded theory (developing theories to explain phenomena, the theories emerging from the data rather than being prefigured or predetermined);

biography (individual or collective);

biography (individual or collective);

phenomenology (seeing things as they are really like and establishing the meanings of things through illumination and explanation rather than through taxonomic approaches or abstractions, and developing theories through the dialogic relationships of researcher to researched).

phenomenology (seeing things as they are really like and establishing the meanings of things through illumination and explanation rather than through taxonomic approaches or abstractions, and developing theories through the dialogic relationships of researcher to researched).

The main methods for data collection in naturalistic enquiry are (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1983):

participant observation;

participant observation;

interviews and conversations;

interviews and conversations;

documents and field notes;

documents and field notes;

accounts;

accounts;

notes and memos.

notes and memos.

In many ways the issues in naturalistic research are not exclusive; they apply to other forms of research, for example: identifying the problem and research purposes; deciding the focus of the study; identifying the research questions; selecting the research design and instrumentation; addressing validity and reliability; ethical issues; approaching data analysis and interpretation. These are common to all research. More specifically Wolcott (1992: 19) suggests that naturalistic researchers should address the stages of watching, asking and reviewing, or, as he puts it, experiencing, enquiring and examining. In naturalistic enquiry it is possible to formulate a more detailed set of stages that can be followed (Hitchcock and Hughes, 1989: 57–71; Bogdan and Biklen, 1992; LeCompte and Preissle, 1993). These are presented in Figure 11.1 and are subsequently dealt with in the later pages of this chapter.

One has to be cautious here: Figure 11.1 suggests a linearity in the sequence; in fact the process is often more complex that this, and there may be a backwards-and-forwards movement between the several stages over the course of the planning and conduct of the research. The process is iterative and recursive, as different elements will come into focus and interact with each other in different ways at different times. Indeed Flick (2009: 133) suggests a circularity or mutually informing nature of elements of a qualitative research design. In this instance the stages of Figure 11.1 might be better presented as interactive elements as in Figure 11.2.

Further, in some smaller-scale qualitative research not all of these stages may apply, as the researcher may not always be staying for a long time in the field but might only be gathering qualitative data on a ‘one-shot’ basis (e.g. a qualitative survey, qualitative interviews). However, for several kinds of naturalistic and ethnographic study in which the researcher intends to remain in the field for some time, the several stages set out above, and commented upon in the following pages, may apply.

These stages are shot through with a range of issues that will affect the research, e.g.:

personal issues (the disciplinary sympathies of the researcher, researcher subjectivities and characteristics, personal motives and goals of the researcher). Hitchcock and Hughes (1989: 56) indicate that there are several serious strains in conducting fieldwork because the researcher’s own emotions, attitudes, beliefs, values, characteristics enter the research; indeed, the more this happens the less will be the likelihood of gaining the participants’ perspectives and meanings;

personal issues (the disciplinary sympathies of the researcher, researcher subjectivities and characteristics, personal motives and goals of the researcher). Hitchcock and Hughes (1989: 56) indicate that there are several serious strains in conducting fieldwork because the researcher’s own emotions, attitudes, beliefs, values, characteristics enter the research; indeed, the more this happens the less will be the likelihood of gaining the participants’ perspectives and meanings;

the kinds of participation that the researcher will undertake;

the kinds of participation that the researcher will undertake;

issues of advocacy (where the researcher may be expected to identify with the same emotions, concerns and crises as the members of the group being studied and wishes to advance their cause, often a feature that arises at the beginning and the end of the research when the researcher is considered to be a legitimate spokesperson for the group);

issues of advocacy (where the researcher may be expected to identify with the same emotions, concerns and crises as the members of the group being studied and wishes to advance their cause, often a feature that arises at the beginning and the end of the research when the researcher is considered to be a legitimate spokesperson for the group);

role relationships;

role relationships;

boundary maintenance in the research;

boundary maintenance in the research;

the maintenance of the balance between distance and involvement;

the maintenance of the balance between distance and involvement;

ethical issues;

ethical issues;

reflexivity.

reflexivity.

Reflexivity recognizes that researchers are inescapably part of the social world that they are researching (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1983: 14), and, indeed, that this social world is an already interpreted world by the actors, undermining the notion of objective reality. Researchers are in the world and of the world. They bring their own biographies to the research situation and participants behave in particular ways in their presence. Qualitative enquiry is not a neutral activity, and researchers are not neutral; they have their own values, biases and world views, and these are lenses through which they look at and interpret the already-interpreted world of participants (cf. Preissle, 2006: 691). Reflexivity suggests that researchers should acknowledge and disclose their own selves in the research, seeking to understand their part in, or influence on, the research. Rather than trying to eliminate researcher effects (which is impossible, as researchers are part of the world that they are investigating), researchers should hold themselves up to the light, echoing Cooley’s (1902) notion of the ‘looking glass self’. As Hammersley and Atkinson say:

He or she [the researcher] is the research instrument par excellence. The fact that behaviour and attitudes are often not stable across contexts and that the researcher may play a part in shaping the context becomes central to the analysis. . . . The theories we develop to explain the behaviour of the people we study should also, where relevant, be applied to our own activities as researchers.

(Hammersley and Atkinson, 1983: 18 and 19)

Highly reflexive researchers will be acutely aware of the ways in which their selectivity, perception, background and inductive processes and paradigms shape the research. They are research instruments. McCormick and James (1988: 191) argue that combating reactivity through reflexivity requires researchers to monitor closely and continually their own interactions with participants, their own reaction, roles, biases and any other matters that might affect the research. This is addressed more fully in Chapter 10 on validity, encompassing issues of triangulation and respondent validity.

Lincoln and Guba (1985: 226–47) set out ten elements in research design for naturalistic studies:

1 Determining a focus for the enquiry.

2 Determining the fit of paradigm to focus.

3 Determining the ‘fit’ of the enquiry paradigm to the substantive theory selected to guide the enquiry.

4 Determining where and from whom data will be collected.

5 Determining successive phases of the enquiry.

6 Determining instrumentation.

7 Planning data collection and recording modes.

8 Planning data analysis procedures.

9 Planning the logistics:

a prior logistical considerations for the project as a whole;

b the logistics of field excursions prior to going into the field;

c the logistics of field excursions while in the field;

d the logistics of activities following field excursions;

e the logistics of closure and termination.

10 Planning for trustworthiness.

These elements can be set out into a sequential, staged approach to planning naturalistic research (see, for example, Schatzman and Strauss, 1973; Delamont, 1992). Spradley (1979) sets out the stages of: (i) selecting a problem; (ii) collecting cultural data; (iii) analysing cultural data; (iv) formulating ethnographic hypotheses; (v) writing the ethnography. We offer a fuller, 12-stage model earlier in the chapter.

Like other styles of research, naturalistic and qualitative methods will need to formulate research questions which should be clear and unambiguous but open to change as the research develops. Strauss (1987) terms these ‘generative questions’: they stimulate the line of investigation, suggest initial hypotheses and areas for data collection, yet they do not foreclose the possibility of modification as the research develops. A balance has to be struck between having research questions that are so broad that they do not steer the research in any particular direction, and so narrow that they block new avenues of enquiry (Flick, 2004b: 150).

Miles and Huberman (1994) identify two types of qualitative research design: loose and tight. Loose research designs have broadly defined concepts and areas of study, and, indeed, are open to changes of methodology. These are suitable, they suggest, when the researchers are experienced and when the research is investigating new fields or developing new constructs, akin to the flexibility and openness of theoretical sampling of Glaser and Strauss (1967). By contrast, a tight research design has narrowly restricted research questions and predetermined procedures, with limited flexibility. These, the authors suggest, are useful when the researchers are inexperienced, when the research is intended to look at particular specified issues, constructs, groups or individuals, or when the research brief is explicit.

Even though, in naturalistic research, issues and theories emerge from the data, this does not preclude the value of having research questions. Flick (1998: 51) suggests three types of research questions in qualitative research, namely those that are concerned with: (a) describing states, their causes and how these states are sustained; (b) describing processes of change and consequences of those states; (c) how suitable they are for supporting or not supporting hypotheses and assumptions or for generating new hypotheses and assumptions (the ‘generative questions’ referred to above).

We mentioned in Chapter 1 that positivist approaches typically test pre-formulated hypotheses and that a distinguishing feature of naturalistic and qualitative approaches is its reluctance to enter the hypotheticodeductive paradigm (e.g. Meinefeld, 2004: 153), not least because there is a recognition that the researcher influences the research and because the research is much more open and emergent in qualitative approaches. Indeed, Meinefeld, citing classic studies like Whyte’s (1955) Street Corner Society, suggests that it is impossible to predetermine hypotheses, whether one would wish to or not, as prior knowledge cannot be presumed. Glaser and Strauss (1967) suggest that researchers should deliberately free themselves from all prior knowledge, even suggesting that it is impossible to read up in advance, as it is not clear what reading will turn out to be relevant – the data speak for themselves. Theory is the end point of the research, not its starting point.

One has to be mindful that the researcher’s own background interest, knowledge and biography precede the research and that though initial hypotheses may not be foregrounded in qualitative research, nevertheless the initial establishment of the research presupposes a particular area of interest, i.e. the research and data for focus are not theory-free; knowledge is not theory-free. Indeed Glaser and Strauss (1967) acknowledge that they brought their own prior knowledge to their research on dying.

The resolution of this apparent contradiction – the call to reject an initial hypothesis in qualitative research, yet a recognition that all research commences with some prior knowledge or theory that gives rise to the research, however embryonic – may lie in several fields. These include: an openness to data (Meinefeld, 2004: 156–7); a preparedness to modify one’s initial presuppositions and position; a declaration of the extent to which the researcher’s prior knowledge may be influencing the research (i.e. reflexivity); a recognition of the tentative nature of one’s hypothesis; a willingness to use the research to generate a hypothesis; and, as a more extreme position, an acknowledgement that having a hypothesis may be just as much a part of qualitative research as it is of quantitative research.

An alternative to research hypotheses in qualitative research is a set of research questions, and we consider these below. For qualitative research, Miles and Huberman (1994: 74) also suggest the replacement of ‘hypotheses’ with ‘propositions’, as this indicates that the qualitative research is not necessarily concerned with testing a predetermined hypothesis as such but, nevertheless, is concerned to be able to generate and test a theory (e.g. grounded theory that is tested).

An effective qualitative study has several features (Creswell, 1998: 20–2), and these can be addressed in evaluating qualitative research:

It uses rigorous procedures and multiple methods for data collection.

It uses rigorous procedures and multiple methods for data collection.

The study is framed within the assumptions and nature of qualitative research.

The study is framed within the assumptions and nature of qualitative research.

Enquiry is a major feature, and can follow one or more different traditions (e.g. biography, ethnography, phenomenology, case study, grounded theory).

Enquiry is a major feature, and can follow one or more different traditions (e.g. biography, ethnography, phenomenology, case study, grounded theory).

The project commences with a single focus on an issue or problem rather than a hypothesis or the supposition of a causal relationship of variables. Relationships may emerge later, but that is open.

The project commences with a single focus on an issue or problem rather than a hypothesis or the supposition of a causal relationship of variables. Relationships may emerge later, but that is open.

Criteria for verification are set out, and rigour is practised in writing up the report.

Criteria for verification are set out, and rigour is practised in writing up the report.

Verisimilitude is required, such that readers can imagine being in the situation.

Verisimilitude is required, such that readers can imagine being in the situation.

Data are analysed at different levels; they are multilayered.

Data are analysed at different levels; they are multilayered.

The writing engages the reader and is replete with unexpected insights, whilst maintaining believability and accuracy.

The writing engages the reader and is replete with unexpected insights, whilst maintaining believability and accuracy.

Maxwell (2005: 21) argues that qualitative research should have both practical goals (e.g. that can be accomplished, that deliver a specific outcome and meet a need) and intellectual goals (e.g. to understand or explain something). His practical goals (p. 24) are: (a) to generate ‘results and theories’ that are credible and that can be understood by both participants and other readers; (b) to conduct formative evaluation in order to improve practice; and (c) to engage in ‘collaborative and action research’ with different parties. His intellectual goals (pp. 22–3) are: (a) to understand the meanings attributed to events and situations by participants; (b) to understand particular contexts in which participants are located; (c) to identify unanticipated events, situations and phenomena and to generate grounded theories that incorporate these; (d) to understand processes that contribute to situations, events and actions; and (e) to develop causal explanations of phenomena.

Maxwell (2005: 23) suggests that, whilst quantitative research is interested in discovering the variance – and regularity – in the effects of one or more particular independent variables on an outcome, qualitative research is interested in the causal processes at work in understanding how one or more interventions or factors lead to an outcome, the mechanisms of their causal linkages. Quantitative research can tell us correlations, how much, whether and ‘what’, whilst qualitative research can tell us the ‘how’ and ‘why’ – the processes – involved in understanding how things occur.

Maxwell also argues that qualitative research should be based on a suitable theoretical or paradigmal basis. Quoting Becker (1986), Maxwell (2005: 37) argues that if a researcher bases his or her research in an inappropriate theory or paradigm it is akin to a worker wearing the wrong clothes: it inhibits comfort and the ability to work properly. Maxwell cautions researchers to recognize that theoretical premises may not always be clear at the outset of the research; they may emerge, change, be added to and so on over time as the qualitative research progresses. We have discussed theories and paradigms in Chapter 1. Theory, Maxwell avers (p. 43) can provide a supporting set of principles, world view or sense-making referent, and it can be used as a ‘spotlight’, illuminating something very specific in a particular event or phenomenon. He advocates a cautious approach to the use of theory (p. 46), steering between, on the one hand, having it unnecessarily constrain and narrow a field of investigation and being accepted too readily and uncritically, and, on the other hand, not using it enough to ground rigorous research. Theories used in qualitative research should not only be those of the researcher, but also those of the participants. He suggests that theory can provide the conceptual and justificatory basis for the qualitative research being undertaken, and it can also inform the methods and data sources for the study (p. 55).

Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 2) suggest that research questions in qualitative research are not framed by simply operationalizing variables as in the positivist paradigm. Rather, research questions are formulated in situ and in response to situations observed, i.e. that topics are investigated in all their complexity, in the naturalistic context. The field, as Arsenault and Anderson (1998: 125) state, ‘is used generically in qualitative research and quite simply refers to where the phenomenon exists’.

In some qualitative studies, the selection of the research field will be informed by the research purposes, the need for the research, what gave rise to the research, the problem to be addressed, and the research questions and sub-questions. In other qualitative studies these elements may only emerge after the researcher has been immersed for some time in the research site itself.

Research questions are an integral and driving feature of qualitative research. They must be able to be answered concretely, specifically and with evidence. They must be achievable and finite (cf. Maxwell, 2005: 65–78) and they are often characterized by being closed rather than open questions. Whereas research purposes can be open and less finite, motivated by a concern for ‘understanding’, research questions, by contrast, though they are informed by research purposes, are practical and able to be accomplished (Maxwell, 2005: 68–9).

Hence instead of asking a non-directly answerable question such as ‘how should we improve online learning for biology students?’ we can ask a specific, focused, bounded and answerable question such as ‘how has the introduction of an online teacher–student chat room improved Form 5 students’ interest in learning biology?’. Here the word ‘should’ (as an open question) has been replaced with ‘has’, the general terminology of ‘online learning’ has been replaced with ‘an online teacher–student chat room’, and the open-endedness of the first question has been replaced with the closed nature of the second (cf. Maxwell, 2005: 21).

Whereas in quantitative research, a typical research question asks ‘what’ and ‘how much’ (e.g. ‘how much do male secondary students prefer female teachers of mathematics, and what is the relative weighting of the factors that account for their preferences?’), a qualitative research question often asks more probing, process-driven research questions (e.g. ‘how do secondary school students in school X decide their preferences for male or female teachers of mathematics?’).

Maxwell (2005: 75) suggests that qualitative research questions are suitable for answering questions about: (a) the meanings attributed by participants to situations, events, behaviours and activities; (b) the influence of context (e.g. physical, social, temporal, interpersonal) on participants’ views, actions and behaviours; and (c) the processes by which actions, behaviours, situations and outcomes emerge.

Whilst in quantitative research, the research questions (or hypotheses to be tested) typically drive the research and are determined at the outset, in qualitative research a more iterative process occurs (Light et al., 1990: 19). Here the researcher may have an initial set of research purposes, or even questions, but these may change over the course of the research, as the researcher finds out more about the research setting, participants, context and phenomena under investigation, i.e. the setting of research questions is not a once-and-for-all affair. This is not to say that qualitative research is an unprincipled, aimless activity; rather it is to say that, whilst the researcher may have clear purposes, the researcher is sensitive to the emergent situation in which she finds herself, and this steers the research questions. Research questions are the consequence, not the driver, of the situation and the interactions that take place within it. Indeed, in Chapters 6 and 7 we noted that the research questions are the consequence of the interaction between the goals, conceptual framework, methods and validity of the research (Maxwell, 2005: 11). It is important for the qualitative researcher to ask the right questions rather than to ask about what turn out to be irrelevancies to the participants. As Tukey (1962: 13) remarked, it is better to have approximate, inexact or imprecise answers to the right question than to have precise answers to the wrong question. The qualitative researcher has to be sensitized to the emergent key features of a situation before firming up the research questions.

Deyle et al. (1992: 623) identify several critical ethical issues that need to be addressed in approaching the research: How does one present oneself in the field? As whom does one present oneself? How ethically defensible is it to pretend to be somebody that you are not in order to: (a) gain knowledge that you would otherwise not be able to acquire; (b) obtain and preserve access to places which otherwise you would be unable to secure or sustain?

The issues here are several. First, there is the matter of informed consent (to participate and for disclosure), whether and how to gain participant assent (see also LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 66). This uncovers another consideration, namely covert or overt research. On the one hand there is a powerful argument for informed consent. However, the more participants know about the research the less naturally they may behave (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 108), and naturalism is self-evidently a key criterion of the naturalistic paradigm.

Mitchell (1993) catches the dilemma for researchers in deciding whether to undertake overt or covert research. The issue of informed consent, he argues, can lead to the selection of particular forms of research – those where researchers can control the phenomena under investigation – thereby excluding other kinds of research where subjects behave in less controllable, predictable, prescribed ways, indeed where subjects may come in and out of the research over time.

Mitchell argues that in the real social world access to important areas of research is prohibited if informed consent has to be sought, for example in researching those on the margins of society or the disadvantaged. It is to the participants’ own advantage that secrecy is maintained as, if secrecy is not upheld, important work may not be done and ‘weightier secrets’ (Mitchell, 1993: 54) may be kept which are of legitimate public concern and in the participants’ own interests. He makes a powerful case for secrecy, arguing that informed consent may excuse social scientists from the risk of confronting powerful, privileged and cohesive groups who wish to protect themselves from public scrutiny. Secrecy and informed consent are moot points. The researcher, then, has to consider her loyalties and responsibilities (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 106), for example what is the public’s right to know and what is the individual’s right to privacy (Morrison, 1993; De Laine, 2000: 13).

In addition to the issue of overt or covert research, LeCompte and Preissle (1993) indicate that the problems of risk and vulnerability to subjects must be addressed; steps must be taken to prevent risk or harm to participants (non-maleficence – the principle of primum non nocere). Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 54) extend this to include issues of embarrassment as well as harm to those taking part. The question of vulnerability is present at its strongest when participants in the research have their freedom to choose limited, e.g. by dint of their age, by health, by social constraints, by dint of their lifestyle (e.g. engaging in criminality), social acceptability, experience of being victims (e.g. of abuse, of violent crime) (p. 107). As the authors comment, participants rarely initiate research, so it is the responsibility of the researcher to protect them. Relationships between researcher and the researched are rarely symmetrical in terms of power; it is often the case that those with more power, information and resources research those with less.

A standard protection is often the guarantee of confidentiality, withholding participants’ real names and other identifying characteristics. The authors contrast this with anonymity, where identity is withheld because it is genuinely unknown (Bogdan and Biklen, 1992: 106). The issues are raised of identifiability and traceability. Further, participants might be able to identify themselves in the research report though others may not be able to identify them. A related factor here is the ownership of the data and the results, the control of the release of data (and to whom, and when) and what rights respondents have to veto the research results. Patrick (1973) indicates this point at its sharpest, when as an ethnographer of a Glasgow gang, he was witness to a murder; the dilemma was clear – to report the matter (and, thereby, also to ‘blow his cover’, consequently endangering his own life) or to stay as a covert researcher.

Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 54) add to this discussion the need to respect participants as subjects, not simply as research objects to be used and then discarded. Mason (2002: 41) suggests that it is important for researchers to consider the parties, bodies, practices that might be interested in, or affected by, the research and the implications of the answer to these questions for the conduct, reporting and dissemination of the enquiry. We address ethics in Chapters 2 and 5 and we advise readers to refer to these.

In an ideal world the researcher would be able to study a group in its entirety. This was the case in Goffman’s (1968) work on ‘total institutions’ – e.g. hospitals, prisons and police forces (see also Chapter 31). It was also the practice of anthropologists who were able to explore specific isolated communities or tribes. That is rarely possible nowadays because such groups are no longer isolated or insular. Hence the researcher is faced with the issue of sampling, that is deciding which people it will be possible to select to represent the wider group (however defined). The researcher has to decide the groups for which the research questions are appropriate, the contexts which are important for the research, the time periods that will be needed, and the possible artefacts of interest to the investigator. In other words decisions are necessary on the sampling of people, contexts, issues, time frames, artefacts and data sources. This takes the discussion beyond conventional notions of sampling.

In several forms of research, sampling is fixed at the start of the study, though there may be attrition of the sample through ‘mortality’ (e.g. people leaving the study). Mortality is seen as problematic. Ethnographic research regards this as natural rather than irksome. People come into and go from the study. This impacts on the decision whether to have a synchronic investigation occurring at a single point in time, or a diachronic study where events and behaviour are monitored over time to allow for change, development and evolving situations. In ethnographic enquiry sampling is recursive and ad hoc rather than fixed at the outset; it changes and develops over time. Let us consider how this might happen.

LeCompte and Preissle (1993: 82–3) point out that ethnographic methods rule out statistical sampling, for a variety of reasons:

the characteristics of the wider population are unknown;

the characteristics of the wider population are unknown;

there are no straightforward boundary markers (categories or strata) in the group;

there are no straightforward boundary markers (categories or strata) in the group;

generalizability, a goal of statistical methods, is not necessarily a goal of ethnography;

generalizability, a goal of statistical methods, is not necessarily a goal of ethnography;

characteristics of a sample may not be evenly distributed across the sample;

characteristics of a sample may not be evenly distributed across the sample;

only one or two subsets of a characteristic of a total sample may be important;

only one or two subsets of a characteristic of a total sample may be important;

researchers may not have access to the whole population;

researchers may not have access to the whole population;

some members of a subset may not be drawn from the population from which the sampling is intended to be drawn.

some members of a subset may not be drawn from the population from which the sampling is intended to be drawn.

Hence other types of sampling are required. A criterion-based selection requires the researcher to specify in advance a set of attributes, factors, characteristics or criteria that the study must address. The task then is to ensure that these appear in the sample selected (the equivalent of a stratified sample). There are other forms of sampling (discussed in Chapter 8) that are useful in ethnographic research (Bogdan and Biklen, 1992: 70; LeCompte and Preissle, 1993: 69–83), such as:

convenience sampling (opportunistic sampling, selecting from whoever happens to be available);

convenience sampling (opportunistic sampling, selecting from whoever happens to be available);

critical-case sampling (e.g. people who display the issue or set of characteristics in their entirety or in a way that is highly significant for their behaviour);

critical-case sampling (e.g. people who display the issue or set of characteristics in their entirety or in a way that is highly significant for their behaviour);

extreme-case sampling (the norm of a characteristic is identified, then the extremes of that characteristic are located, and finally, the bearers of that extreme characteristic are selected);

extreme-case sampling (the norm of a characteristic is identified, then the extremes of that characteristic are located, and finally, the bearers of that extreme characteristic are selected);

typical-case sampling (where a profile of attributes or characteristics that are possessed by an ‘average’, typical person or case is identified, and the sample is selected from these conventional people or cases);

typical-case sampling (where a profile of attributes or characteristics that are possessed by an ‘average’, typical person or case is identified, and the sample is selected from these conventional people or cases);

unique-case sampling, where cases that are rare, unique or unusual on one or more criteria are identified, and sampling takes places within these. Here whatever other characteristics or attributes a person might share with others, a particular attribute or characteristic sets that person apart;

unique-case sampling, where cases that are rare, unique or unusual on one or more criteria are identified, and sampling takes places within these. Here whatever other characteristics or attributes a person might share with others, a particular attribute or characteristic sets that person apart;

reputational-case sampling, a variant of extreme-case and unique-case sampling, is where a researcher chooses a sample on the recommendation of experts in the field;

reputational-case sampling, a variant of extreme-case and unique-case sampling, is where a researcher chooses a sample on the recommendation of experts in the field;

snowball sampling – using the first interviewee to suggest or recommend other interviewees.

snowball sampling – using the first interviewee to suggest or recommend other interviewees.

Patton (1980) identifies several types of sampling that are useful in naturalistic research, including

sampling extreme/deviant cases. This is done in order to gain information about unusual cases that may be particularly troublesome or enlightening;

sampling extreme/deviant cases. This is done in order to gain information about unusual cases that may be particularly troublesome or enlightening;

sampling typical cases. This is done in order to avoid rejecting information on the grounds that it has been gained from special or deviant cases;

sampling typical cases. This is done in order to avoid rejecting information on the grounds that it has been gained from special or deviant cases;

snowball sampling. This is where one participant provides access to a further participant and so on;

snowball sampling. This is where one participant provides access to a further participant and so on;

maximum variation sampling. This is done in order to document the range of unique changes that have emerged, often in response to the different conditions to which participants have had to adapt. It is useful if the aim of the research is to investigate the variations, range and patterns in a particular phenomenon or phenomena (Guba and Lincoln, 1989: 178; Ezzy, 2002: 74);

maximum variation sampling. This is done in order to document the range of unique changes that have emerged, often in response to the different conditions to which participants have had to adapt. It is useful if the aim of the research is to investigate the variations, range and patterns in a particular phenomenon or phenomena (Guba and Lincoln, 1989: 178; Ezzy, 2002: 74);

sampling according to the intensity with which the features of interest are displayed or occur;

sampling according to the intensity with which the features of interest are displayed or occur;

sampling critical cases. This is done in order to permit maximum applicability to others – if the information holds true for critical cases (e.g. cases where all the factors sought are present), then it is likely to hold true for others;

sampling critical cases. This is done in order to permit maximum applicability to others – if the information holds true for critical cases (e.g. cases where all the factors sought are present), then it is likely to hold true for others;

sampling politically important or sensitive cases. This can be done to draw attention to the case;

sampling politically important or sensitive cases. This can be done to draw attention to the case;

convenience sampling. This saves time and money and spares the researcher the effort of finding less amenable participants.

convenience sampling. This saves time and money and spares the researcher the effort of finding less amenable participants.

One can add to this list types of sample from Miles and Huberman (1994: 28):

homogenous sampling (which focuses on groups with similar characteristics);

homogenous sampling (which focuses on groups with similar characteristics);

theoretical sampling (in grounded theory, discussed below, where participants are selected for their ability to contribute to the developing/emergent theory);

theoretical sampling (in grounded theory, discussed below, where participants are selected for their ability to contribute to the developing/emergent theory);

confirming and disconfirming cases (akin to the extreme and deviant cases indicated by Patton (1980), in order to look for exceptions to the rule, which may lead to the modification of the rule);

confirming and disconfirming cases (akin to the extreme and deviant cases indicated by Patton (1980), in order to look for exceptions to the rule, which may lead to the modification of the rule);

random purposeful sampling (when the potential sample is too large, a smaller subsample can be used which still maintains some generalizability);

random purposeful sampling (when the potential sample is too large, a smaller subsample can be used which still maintains some generalizability);

stratified purposeful sampling (to identify subgroups and strata);

stratified purposeful sampling (to identify subgroups and strata);

criterion sampling (all those who meet some stated criteria for membership of the group or class under study);

criterion sampling (all those who meet some stated criteria for membership of the group or class under study);

opportunistic sampling (to take advantage of unanticipated events, leads, ideas, issues).

opportunistic sampling (to take advantage of unanticipated events, leads, ideas, issues).

Miles and Huberman make the point that these strategies can be used in combination as well as in isolation, and that using them in combination contributes to triangulation.

Patton (1980: 181) and Miles and Huberman (1994: 27–9) also counsel researchers on the dangers of convenience sampling, arguing that, being ‘neither purposeful nor strategic’ (Patton, 1980: 88), it cannot demonstrate representativeness even to the wider group being studied, let alone to a wider population.

Maxwell (2005: 89–90) indicates four possible purposes of ‘purposeful selection’:

to achieve representativeness of the activities, behaviours, events, settings and individuals involved;

to achieve representativeness of the activities, behaviours, events, settings and individuals involved;

to catch the breadth and heterogeneity of the population under investigation (i.e. the range of the possible variation: the ‘maximum variation’ sampling discussed above);

to catch the breadth and heterogeneity of the population under investigation (i.e. the range of the possible variation: the ‘maximum variation’ sampling discussed above);

to examine critical cases or extreme cases that provide a ‘crucial test’ of theories or that can illuminate a situation in ways which representative cases may not be able to do;

to examine critical cases or extreme cases that provide a ‘crucial test’ of theories or that can illuminate a situation in ways which representative cases may not be able to do;

to identify reasons for similarities and difference between individuals or settings (comparative research).

to identify reasons for similarities and difference between individuals or settings (comparative research).

Maxwell (2005: 91) is clear that methods of data collection are not a logical corollary of, nor an analytically necessary consequence of, the research questions. Research questions and data collection are two conceptually separate activities, though, as we have mentioned earlier in this book, the researcher needs to ensure that they are mutually informing, in order to demonstrate cohesion and fitness for purpose. Methods cannot simply be cranked out, mechanistically, from research questions. Both the methods of data collection and the research questions are strongly influenced by the setting, the participants, the relationships and the research design as they unfold over time.

We discuss below two other categories of sample: ‘primary informants’ and ‘secondary informants’ (Morse, 1994: 228), those who completely fulfil a set of selection criteria and those who fill a selection of those criteria respectively.

Lincoln and Guba (1985: 201–2) suggest an important difference between conventional and naturalistic research designs. In the former the intention is to focus on similarities and to be able to make generalizations, whereas in the latter the objective is informational, to provide such a wealth of detail that the uniqueness and individuality of each case can be represented. To the charge that naturalistic enquiry, thereby, cannot yield generalizations because of sampling flaws the writers argue that this is necessarily though trivially true. In a word, it is unimportant.

Patton (1980: 184) takes a slightly more cavalier approach to sampling, suggesting that ‘there are no rules for sample size in qualitative enquiry’, with the size of the sample depending on what one wishes to know, the purposes of the research, what will be useful and credible, and what can be done within the resources available, e.g. time, money, people, support – important considerations for the novice researcher.

In much qualitative research, it may not be possible or, indeed, desirable, to know in advance whom to sample or whom to include. One of the features of qualitative research is its emergent nature. Hence the researcher may only know which people to approach or include as the research progresses and unfolds (Flick, 2009: 125). In this case the nature of sampling is determined by the emergent issues in the study; this is termed ‘theoretical sampling’: once data have been collected, the researcher decides where to go next, in light of the analysis of the data, in order to gather more data in order to develop his or her theory (Flick, 2009: 118).

Ezzy (2002: 74) underlines the notion of ‘theoretical sampling’ from Glaser and Strauss (1967) in his comment that, unlike other forms of research, qualitative enquiries may not always commence with the full knowledge of whom to sample, but that the sample is determined on an ongoing, emergent basis. Theoretical sampling starts with data and then, having reviewed these, the researcher decides where to go next to collect data for the emerging theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 45). We discuss this more fully in Chapter 33.

In theoretical sampling, individuals and groups are selected for their potential – or hoped for – ability to offer new insights into the emerging theory, i.e. they are chosen on the basis of their significant contribution to theory generation and development. As the theory develops, so the researcher decides whom to approach to request their participation. Theoretical sampling does not claim to know the population characteristics or to represent known populations in advance, and sample size is not defined in advance; sampling is only concluded when theoretical saturation (discussed below) is reached.

Ezzy (2002) gives as an example of theoretical sampling his own work on unemployment (pp. 74–5) where he developed a theory that levels of distress experienced by unemployed people were influenced by their levels of financial distress. He interviewed unemployed low-income and high-income groups with and without debt, to determine their levels of distress. He reported that levels of distress were not caused so much by absolute levels of income but levels of income in relation to levels of debt.

In the educational field one could imagine theoretical sampling in an example thus: interviewing teachers about their morale might give rise to a theory that teacher morale is negatively affected by disruptive student behaviour in schools. This might suggest the need to sample teachers working with many disruptive students in difficult schools, as a ‘critical case sampling’. However, the study finds that some of the teachers working in these circumstances have high morale, not least because they have come to expect disruptive behaviour from students with so many problems, and so are not surprised or threatened by it, and because the staff in these schools provide tremendous support for each other in difficult circumstances – they all know what it is like to have to work with challenging students.

So the study decides to focus on teachers working in schools with far fewer disruptive students. The researcher discovers that it is these teachers who experience far lower morale, and she hypothesizes that this is because this latter group of teachers has higher expectations of student behaviour, such that having only one or two students who do not conform to these expectations deflates staff morale significantly, and because disruptive behaviour is regarded in these schools as teacher weakness, and there is little or no mutual support. Her theory, then, is refined, to suggest that teacher morale is affected more by teacher expectations than by disruptive behaviour, so she adopts a ‘maximum variation sampling’ of teachers in a range of schools, to investigate how expectations and morale are related to disruptive behaviour. In this case the sampling emerges as the research proceeds and the theory emerges; this is theoretical sampling, the ‘royal way for qualitative studies’ (Flick, 2004b: 151). Schatzman and Strauss (1973: 38ff.) suggest that sampling within theoretical sampling may change according to time, place, individuals and events.

The above procedure accords with Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) view that sampling involves continuously gathering data until practical factors (boundaries) put an end to data collection, or until no amendments have to be made to the theory in light of further data – their stage of ‘theoretical saturation’ – where the theory fits the data even when new data are gathered. Theoretical saturation is described by Glaser and Strauss (1967: 61) as being reached when any additional data collected do not advance, amend, refine or lead to the adjustment of the theory or its categories. That said, the researcher has to be cautious to avoid premature cessation of data collection; it would be too easy to close off research with limited data, when, in fact, further sampling and data collection might lead to a reformulation of the theory.

An extension of theoretical sampling is ‘analytic induction’, a process advanced by Znaniecki (1934). Here the researcher starts with a theory (that may have emerged from the data as in grounded theory) and then deliberately proceeds to look for deviant or discrepant cases, to provide a robust defence of the theory. This accords with Popper’s notion of a rigorous scientific theory having to stand up to falsifiability tests. In analytic induction, the researcher deliberately seeks data which potentially could falsify the theory, thereby giving strength to the final theory.

We are suggesting here that, in qualitative research, sampling cannot always be decided in advance on a ‘once and for all’ basis. It may have to continue through the stages of data collection, analysis and reporting. This reflects the circular process of qualitative research, in which data collection, analysis, interpretation and reporting and sampling do not necessarily have to proceed in a linear fashion; the process is recursive and iterative. Sampling is not decided a priori – in advance – but may be decided, amended, added to, increased and extended as the research progresses.

Whilst sampling often refers to people, in qualitative research it also refers to events, places, times, behaviours, activities, settings and processes (cf. Miles and Huberman, 1984: 36). Many researchers will be concerned with short-term, small-scale qualitative research (e.g. qualitative interviews) rather than extended or large-scale ethnographic research, perhaps because they only have access to a small sample (too small to conduct meaningful statistical analysis) or because ‘fitness for purpose’ requires only a short-term qualitative study. In this case, it is important for careful boundaries to be drawn in the research, indicating clearly what can and cannot legitimately be said from the research.

For example, a fundamental question might be for the researcher to decide how long to stay in a situation. Too short, and she may miss an important outcome, too long and key features may become a blur. For example, let us imagine a situation of two teachers in the same school. Teacher A introduces collaborative group work to a class, in order to improve their motivation for, say, learning a foreign language. She gives them a pre-test on motivation, and finds that it is low; she conducts the intervention and then, at the end of two months, gives them another test of motivation, and finds no change. She concludes that the intervention has failed. However, months later, after the intervention has finished, the students tell her that in fact their overall motivation to learn that foreign language had improved, but it took time for them to realize it after the intervention. Teacher B tries the same intervention, but decides to administer the post-test one year after the intervention has ended; she finds no change to motivation levels of the students, but had she conducted the post-test sooner, she would have found a difference. Timing and sampling of timing are important (cf. Maxwell, 2005: 33).