Introduction

FOOD MEMORIES OF THE COBBLER OF MONTEPULCIANO

Since 2001, Virio Neri, the calzolaio (cobbler) of Montepulcian, has been part of our family in a case of mutual adoption. He not only fills the role of grandfather for my daughter, but he has also brought Italian culture to life for us in an intimate way, sharing personal stories and remembrances of his life in our small hill town. The smell of a ciambellone (a simple cake) fresh from the oven can send him into a reverie about his mother’s stufa economica, the wood stove that she rose early every day to light with twigs and hay and hard wood that Virio cut exactly to size for her.

“Oh! The fava beans, fresh with a bit of marzolino [the first sheep’s milk cheese of the season], the chestnuts, and the chickpeas! We survived on these. Do you know how many figs I ate? Sometimes my mother would put an almond or a walnut in a dried fig and warm it in the wood oven. Heaven.

“The best,” he continued, “the very best, was the pan’ santo. We would dip some dry bread in broth, then put boiled cavolo nero [dinosaur or lacinato kale] on top, and a blessing of oil. We’d have that for dinner, and sometimes also for lunch. My mother would say, ‘Corpo pieno, anima consolata,’ which means

‘If your stomach is full, your spirit will be calm.’”

Virio, now in his late seventies, practically swoons when he talks about this food. It makes you wonder about his exceptionally positive memories, because he grew up in a time of poverty and intense hunger. Perhaps desire made the food taste better. Perhaps those simple, pure flavors are harder to find now.

Cucina Buona in Tempi Brutti

GOOD FOOD FOR HARD TIMES

Italy, a country now recognized for its excellent food, has a disturbing history of malnutrition and hunger, mainly sustained by the now-abolished class and sharecropping system known as mezzadria. While the landowners consumed a greater variety of food and nourishing proteins, the working class subsisted on what they could glean from their meager rations and gather from the land.

From these hard times came recipes that have endured and have even become exalted. More than the recipes, la cucina povera, “the cooking of the poor,” or “peasant cooking,” is based on the philosophy of not wasting anything edible and using a variety of simple techniques to make every bite as tasty as possible. It is a cuisine of ingenious creativity in using next to nothing while maintaining a reverence for everything. This lifestyle is not limited to Italy, of course: It has touched every culture that has ever been affected by war, famine, poverty, or natural disaster.

Our adopted nonno (grandfather), Virio, lived through hard times in the late 1930s and the 1940s, when, like his fellow Tuscan countrymen, he survived by foraging, hunting, and living off the land. The period before, during, and after World War II was a time of great poverty in Italy. Stomachs were only ever full then on the rare special occasion of a wedding or a funeral. Very little meat was available, and the preservation of food was more than an art, it was a prerequisite for survival.

Virio recalls that on the way to school every day, he would stop in front of the alimentari, the tiny neighborhood grocery store, and grab a handful of chestnut flour from the bag that was open for customers to scoop out their desired amount. “The owner would look the other way . . . that bit of flour was my breakfast, so sweet and satisfying.”

In Tuscany, many people survived on chestnut flour in those times. The chestnuts from wild trees are a food that can be gathered and preserved by drying. Once dried, the shelled chestnut is ground. The flour is sweet, and while it doesn’t have enough gluten to make bread with, it was used for polenta on a daily basis. Even though poor in protein, chestnuts provide carbohydrates for energy, along with some vitamin C. By contrast, field corn, imported from North America, created nutritional devastation in northern Italy in the 1800s in the form of a disease called pellagra, which is caused by a deficit of niacin in a corn-intensive diet. Unlike the Mayans and ancient American cultures, the Italians had not learned to treat corn with lime, a process that alleviates the niacin deficiency.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most people lived in the countryside in case coloniche, farmhouses that sheltered extended families consisting of as many as ten to fifteen people. In these homes, the focal point was the kitchen, the room with the fireplace, which was not only a source of heat for cooking but also for warmth. At the end of a hard day of work, the family gathered on benches around the fire for conversation and story telling.

Il Focolare

THE HEARTH, CENTER OF THE PEASANT KITCHEN

In many homes, the cooking was done in the fireplace in large pots suspended by blackened chains that could raise or lower the pots to control the cooking temperature. Women stirred wheat, chestnut, or corn polenta in a copper pot over the wood fire, being careful not to lose one bit of precious food sticking to the pot. Virio remembers that the occasional ashes in the pot added a particular flavor, along with the fragrance of wood smoke.

“My mother had a madia, a large wooden chest where flour was kept, and where dough was kneaded and left to rise. On Thursdays, she took the loaves to the communal oven to be baked, and that lasted us the whole week.”

Tuscan bread is not made with salt because up until a few years ago, salt was heavily taxed and was used only for the things that were absolutely necessary such as curing meat and making cheese; none was spared for bread. In any event, bread was baked only once a week, and bread made without salt dries out within a day, as salt is what holds the moisture in the bread. From these simple facts come the many classic Italian recipes that use dry or day-old bread, such as ribollita, panzanella, and pappa al pomodoro. Virio remembers: “We loved the bread fresh from the community oven. My mother would take the dough there in the morning and put her mark on it. At noon, she would go back to pick it up. She would only let us have one piece because the bread had to last all week, and the next day it was already dry. We sometimes soaked it in water, milk, or even wine.”

La Prima Colazione

BREAKFAST, A LADLE OF MILK, AND A PRAYER

Breakfast was often a piece of dry or day-old bread softened in hot milk (or water, if there was no cow) and sometimes a few grains of sugar. In the winter, when there was more time to stir and to spoil the children a bit, there was sometimes sweet polenta with milk. In the summer and fall, however, on the days when there was wheat to harvest or thresh and no time to even start the fire, a simple panino of salume would give energy. At the height of summer, when there was an abundance of garden produce that couldn’t be preserved, such as potatoes, cabbage, or other greens, the leftover soup from the night before would be reheated for breakfast.

Le Quattro Stagioni

THE FOUR SEASONS, COOKING AND EATING IN SEASON

Today, we know that the best produce is local and seasonal. In Virio’s youth, it was the only produce available. Each month had its specialty, and just as now, people looked forward to strawberries in the spring, peaches in the summer, and porcini in the fall.

For the contadino (farmer), the agricultural year followed a fixed schedule, and seasonal dishes were the result. In January, after months of fattening, the pig was slaughtered. Days of labor were needed to turn the animal into salume, sausages, and cooked soppressata. The prime cuts went to the property owner. The hind legs became prosciutto, the front legs became spalla. Other large whole pieces, such as the loin (lombo), belly (pancetta), and neck (coppa) also needed to be salted and massaged and hung to dry. Small pieces of meat and fat were chopped to be fresh sausage or dried to be salame. In any case, there was always some fresh meat to roast or grill, and this was a real treat in the winter.

This was also the time that the drying grapes were pressed to make vin santo. In the cold winter months, when there wasn’t work in the fields, meals were made from the garden produce that had been dried, smoked, or preserved in vinegar, salt, or oil. Soup with dried beans and a piece of pancetta or the usual polenta was a staple, warming and filling.

As early as March, the men went out to plow the land to prepare it for the new crops. With the coming of spring, fava beans, peas, and artichokes graced the table. Eggs were abundant, and soon asparagus and strawberries arrived. Work intensified with the planting. Although the work was hard, it was welcome after the months inside. The colors of the countryside turned from the lilac of wisteria and wild iris to the fiery red of poppies. The women planted summer seeds and scared away the birds as the seedlings came up.

Summer was a time of bounty, but also of work, including for the women who did the cooking. Often, lunch consisted of a hearty panino (sandwich), sometimes with a piece of cheese and some garden vegetables marinated in vinegar. During snail season in June and July, the creatures were captured and kept in a cage supplied with fresh greens every day for forty days to purge and clean them before they were cooked.

In the fall, weather permitting, porcini mushrooms might be foraged on Sundays to grace the top of the polenta. At harvest time, a goose was often roasted and consumed over several meals: The intestines, liver, and stomach were served as toppings for bruschetta (toasted bread), the feet for pasta sauce, and the bones for soup to give the men strength and protein for the trebbiatura (wheat harvest and threshing).

Once the grapes were harvested in the fall, field work slowed down and it was time for hunting birds and rabbits and larger game such as wild boar and deer. The chestnuts ripened and fell from the trees; there was jam to be made from figs; and there were walnuts to gather. After some rain followed by a couple of days of sun, mushrooms were begging to be picked for grilling, sautéing, or preserving in oil.

Starting in November, the olives were harvested and ground into precious oil. The raccolta (olive harvest) was a time of celebration, not only of the new oil, but of the end of the hard work for the year.

OLIVE OIL

In the twenty years that I have been studying olive oil production, and even in the ten that I have been making my own olive oil, I have seen the season and the technique of making olive oil change drastically.

In the past, farmers waited until the last possible minute to harvest, allowing the olives to mature as much as possible, and harvesting them just before temperatures turned to freezing, sometimes as late as December or early January. The oil may have been fruitier, but it wasn’t as fresh tasting as it is now.

The trend these days is to pick earlier, striving for a pizzico, the burn in the back of the throat that is an acquired taste and a prized characteristic of Tuscan oil. The pizzico is present in a variety of olive called coreggiolo, but can also be achieved from an immature olive of any variety, hence the earlier picking.

Extraction methods have changed as well. The stone-ground olive paste is no longer stacked on straw mats and pressed; instead more hygienic methods are used to macerate and extract the oil under conditions that inhibit oxidation. This processing lowers the acidity and produces a fresher oil that tastes better and lasts longer.

As it is today, the raccolta (olive harvest) in the past was a time of celebration because the hardest work was done for the year. A lighted fire, toasted bread, new oil drizzled on top—it doesn’t get much better than that.

Le Memorie

MEMORIES

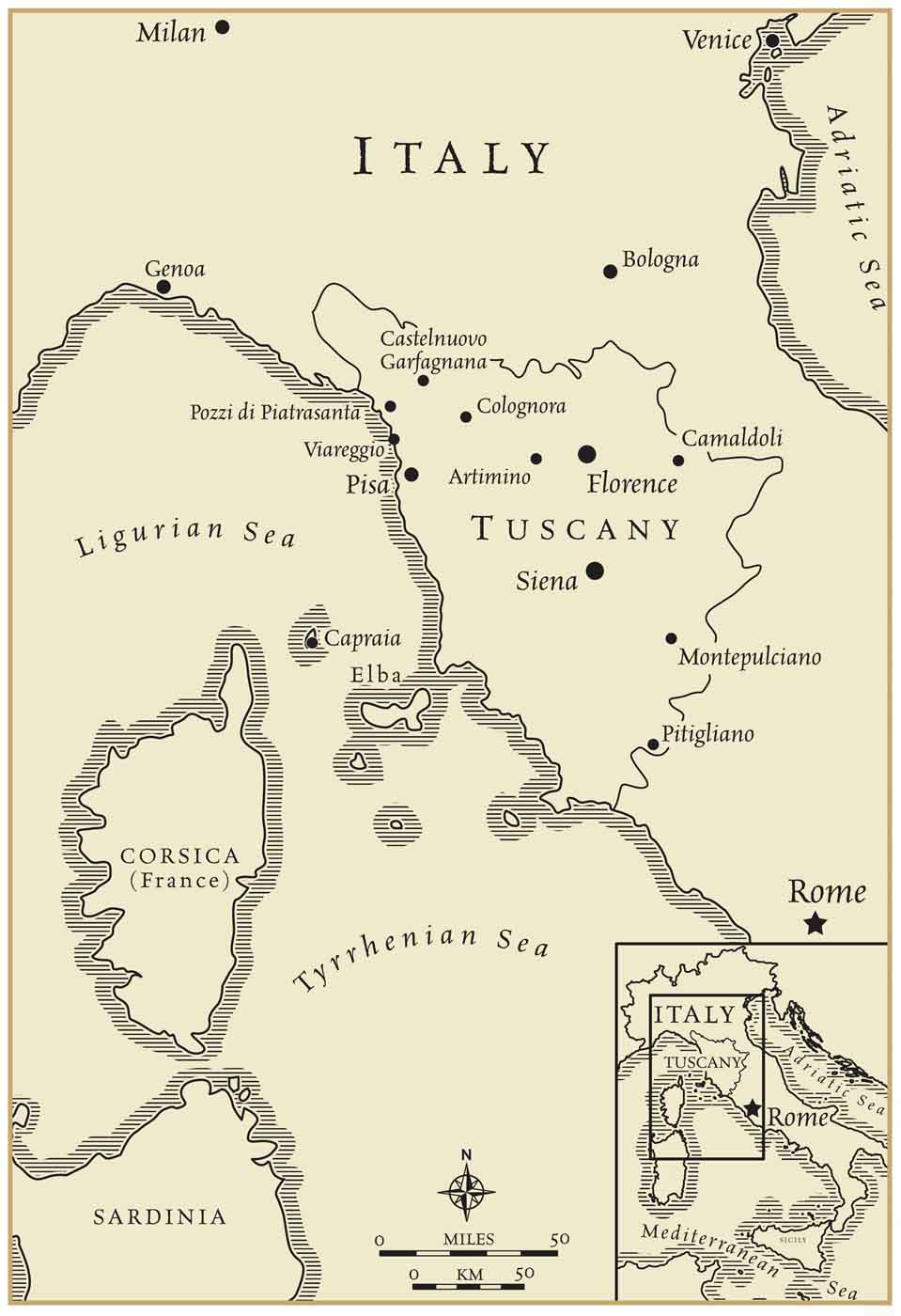

Following are stories from some of my other Tuscan friends about how they managed in hard times. We begin with the rolling hills where I live, then a city visit, then up into the Apennine and Apuane Mountains, then down to the sea, south to the Maremma, and finally back home to Montepulciano. Each area had a different experience in hard times, but throughout Italy the story was the same: making do with inexpensive local foods.

Artimino

COOKING AND ECONOMIA RURALE

Our first stop is in Artimino, just northeast of Florence, to visit chef Carlo Cioni, my original icon of cucina povera. I met Carlo at his restaurant Da Delfina in 1992 and learned for the first time about the peasant cooking of the past. At that time, Carlo’s mother, Delfina, was still alive, shelling peas and ironing tablecloths for the restaurant. She died last year, at the age of 101.

Delfina was not only the namesake of the restaurant, she was the original chef, starting at the nearby Medici hunting lodge, then eventually opening her own establishment. She was the inspiration for the kind of cooking that Carlo has masterfully carried on, a cuisine based on the careful use of ingredients, an attention to flavor, and a respect for tradition. Something that Carlo told me when I first met him still holds true: “Today’s choice of simple foods is not out of necessity as it was in the past. Now, in addition to considering economy, we are seeking quality and purity of flavor.”

Carlo calls his cooking economia rurale, “rural economy,” an approach that emphasizes local, natural, and seasonal foods. He is just as happy foraging in the fields around his restaurant as he is cooking what he finds. A bright smile flashes in his tanned face as he grabs a handful of wild borage or fennel. “We can eat the borage flowers in a salad and dry the fennel flowers to sprinkle on roasted meats. The land has a lot to give; you just have to look.” In his kitchen garden, he grows the essential aromi (flavors) of the Tuscan kitchen: carrots, celery, and onions. Herbs, cultivated and wild, abound, as does seasonal produce like cavolo nero, which he will use in the fall for ribollita. Carlo’s ribollita is a classic example of the economy of this cuisine. Ribollita literally means “reboiled,” and is a traditional Tuscan dish that exemplifies the frugality and resourcefulness of Tuscan cooks in using leftover ingredients.

Il Casentino

THE SIMPLE LIFE

The Casentino is an area in the Apennines above Arezzo. Long the domain of woodcutters, charcoal-makers, and shepherds, the land provides highly acclaimed cultivated foods, cured meat products, and foraged and hunted delicacies. The potatoes, tomatoes, and corn are exceptional. Mushrooms, boar, and hare are traditional seasonal fare; trout, eel, and frog are appreciated as well. The local pork breed called Casentinese, which is raised on the wild forage of oaks and chestnut trees, is transformed into treasures such as rigatino (pancetta), migliaccio (blood sausage), and prosciutto.

The prosciutti are salted and air-dried for several months; these hams are unique for their spice blend, which contains the usual salt, garlic, and pepper, but also peperoncino (red pepper), nutmeg, and ground juniper berries. After about fifty days of cleaning and salting, the prosciutti are then hung in a room with a fireplace to lightly smoke for a few months.

The old ways are still evident in these mountains. Many ancient water mills have survived the ages, and several are still working. At the heart of it all is a religious sanctuary that also has not changed much in five hundred years.

When your life is based on simple premises, influences from the outside world don’t alter it greatly. Tucked in the mountains of the Casentino above Arezzo, at the border of Tuscany and Romagna, is the source of the Arno, one of Tuscany’s principal rivers. Nearby, an order of monks has found sanctuary since the year 1012. In the solitude of this faraway place, they have raised food to a higher order for the glory of God, by honoring their own well-being and that of the local people in frugal ways that are genuine and natural, always respecting tradition. The Camaldoli monks find spirituality in the environment and in nature, using healing combinations of plants and herbs in recipes dating back to 1510. In that year, the monastery’s botanical garden began providing material for the pharmacy, which is still equipped with its original distillery, mortars, stoves, and antique documents.

The Casentino valley is the site of an immense forest of maple, ash, elm, fir, beech, and chestnut trees. Considered a sacred place in Etruscan times, the forest has been tended by the Camaldoli monks for centuries. For the monks, the forest was and is a natural temple. Their codex, a sixteen-thousand-page document spanning seven hundred years, is on file in the State Archives in Florence and used by modern agronomists as a natural forestry guide. The Casentino, now a national park, is where Dante wandered while writing The Divine Comedy during the first years of his exile. It was also a retreat for St. Francis, who, in 1224, received the stigmata at nearby La Verna. Today, the forest is a lush habitat for deer, wild boar, wolves, and many different species of birds, including the golden eagle.

Between the Camaldoli and the Franciscans, this has long been a religious destination, with pilgrims passing through and very likely bringing with them plants to add to the monastery garden. Today, as in the past, the monks produce distilled liqueurs and cordials that have been infused without heating and can be sipped or added to sparkling water after a meal to aid digestion and improve health. All infusions are made with organic plants and herbs grown and gathered from the monastery garden. Over the centuries, the monks have learned that certain plants have healing properties, such as rosemary for vision, eucalyptus for coughs, verbena for depression, echinacea for allergies, chamomile for relaxation, and dandelion root for digestion. Bee propolis and honeys are produced for their antibiotic and antibacterial properties, and are recommended for respiratory problems, sore throats, and colds.

HERBAL REMEDIES

For more than five hundred years, the Camaldoli monks of the Casentino have been cultivating organic herbs and plants for remedies designed to restore equilibrium to the body. Here are some of the combinations used to make teas or liqueurs that aid insomnia, indigestion, and other physical maladies, accompanied by their words of wisdom regarding the ailments.

THE ARTICHOKE BLEND (liver)

“Not everything you eat is always tolerated by the liver.” Artichoke, combretum (bushwillow), elder, rapontico (rhubarb), karkadè (hibiscus flower), smaller centaurea (cornflower), sweet-smelling asperula (woodruff ), elicriso (curry plant), rosemary, chicory, licorice, and sweet orange.

MELISSA BLEND (sleep)

“Even if you sleep well without this herb tea, you will sleep better with it.” Melissa, linden, hawthorn, chamomile, sweet-smelling verbena, sweet-smelling asperula (woodruff ), hops, orange, and poppies.

FENNEL BLEND (digestion)

“After a meal that was too plentiful, or in case of heaviness, a good digestive is noteworthy.” Fennel, mint, linden, licorice, sweet orange, bellflower, rosemary, melissa, hyssop, orange, karkadè (hibiscus flower), centaurea (cornflower), and lavender.

OAK BLEND (overweight)

“It pleases no one to travel the road with a very heavy backpack, with kilos in excess.” Oak, ash, mountain rhamnus (buckthorn), sage, quinine, birch, licorice, equiseto (horsetail), fennel, mint, achillea millefoglie (yarrow), red grapes, juniper berries, asparagus, sweet orange, and lemon.

EUCALYPTUS BLEND (sleep/cough)

“For the desperate sleep of one who coughs.” Eucalyptus, chamomile, licorice, fennel, mint, malva (mallow), coltsfoot, pine, lichen, verbasco (mullein), centaurea (cornflower), primrose, poppy, and broom.

WILD GRASS BLEND (constipation)

“In nature there exists the solution to the problem of constipation: healthy nutrition, movement, and a good herb tea.” Cassius obtusifolia (cassia seed), wild grass, mint, bardana (burdock), parietaria, chamomile, coriander, fennel, melissa summit, sarsaparilla, and star anise.

Colognora

CASTAGNO SACRO, THE SACRED CHESTNUT

High in the sparsely populated mountains above the town of Collodi, in the province of Lucca, the winding road called la via delle cartiere meanders through lush woods to arrive at the tiny village of Colognora. Via delle cartiere means “the road of the paper makers” and is lined with paper mills. In the 1700s, this area was a thriving source of paper made from straw. Now, some of the structures are in ruin, their large grinding stones left abandoned, but some are still active, with mountains of recycled paper waiting to be processed by modern machinery.

Colognora is eighteen hundred feet above sea level and quite distant from big-city life. There is a complete sense of stepping back in time, from the demeanor of the residents to the lack of twenty-first-century trappings.

To the mountain dwellers of the past, the chestnut tree was a gift in every aspect of their existence. Nothing was wasted; it could be considered the symbol of cucina povera. The nut was eaten fresh or dried and ground for flour; the shells were used for fuel to dry the chestnuts. The dark, pungent honey from the chestnut flowers was eaten with the fresh local ricotta. The best wood of the tree was used for building, barrels, furniture, and hand tools. Lesser-quality wood was used for fencing and posts, thin shaved pieces became baskets, and the leftover bits of wood were turned into slow-burning charcoal used in the forging of knives and sharp tools. The tannins extracted from the wood were employed to tan leather. The fresh leaves, along with old chestnuts and acorns, were used for animal feed, and in the autumn the fallen leaves were used to line the stalls in place of hay, which was used in the paper mills.

There are several varieties of the castagno, as the chestnut tree is called in Italian, but the farina dolce, or sweet flour, in this area comes from the Carpinesi variety. These wild trees were pruned and tended as if they were part of an orchard.

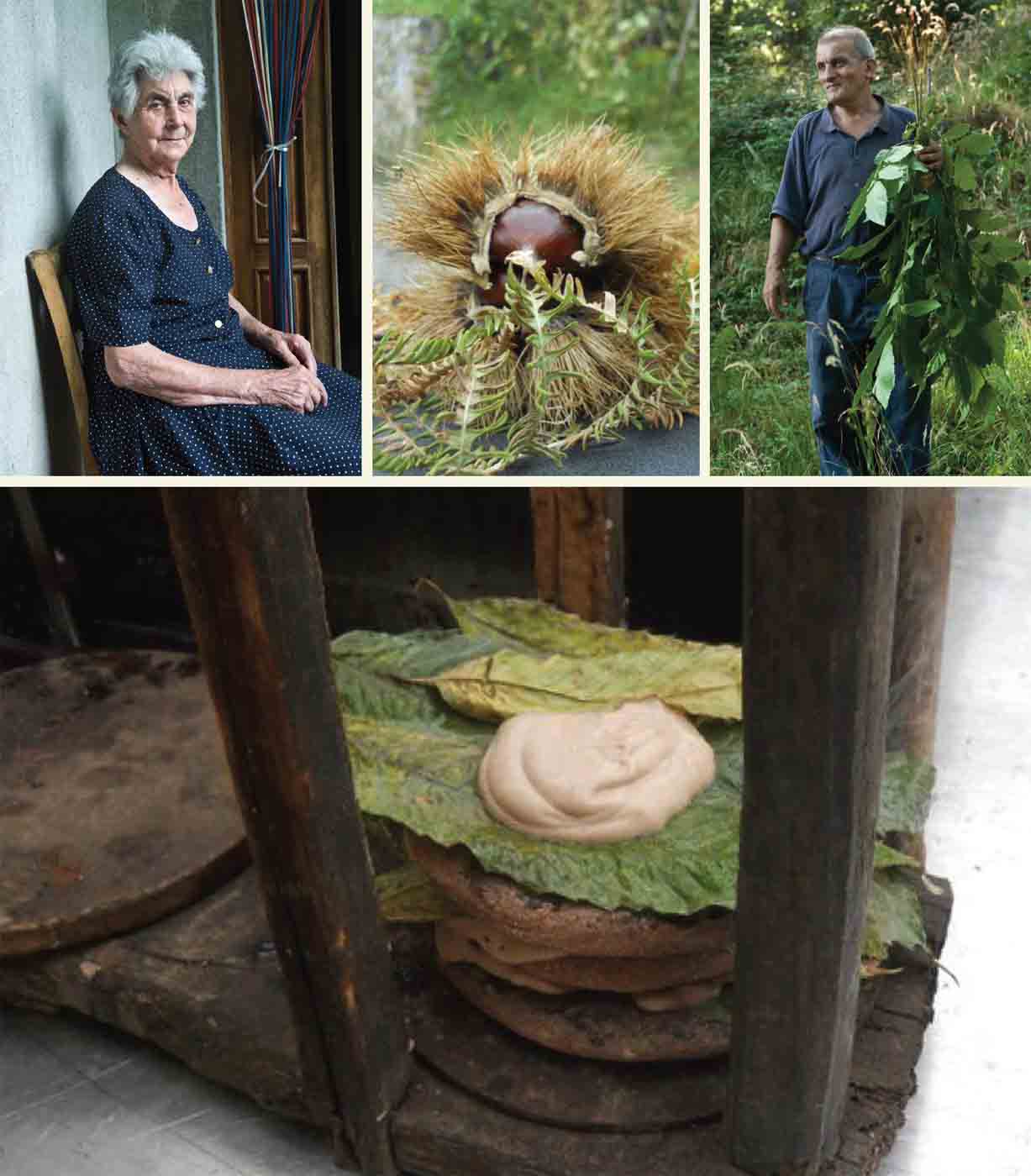

I met with three elderly women who grew up in these mountains, Eni Fiorini Marcucci (born in 1921), her cousin, Meri Franceschi (born in 1932), in Colognora; and Lucia Andreotti (born in 1936) from Piteglio in the mountains above Pistoia. All three endured difficult times, especially after the war, but with the chestnut they always had food to eat. Foraging was and is a way of life, with an abundance of mushrooms and game found in the woods. At home, they cultivated beans and potatoes, and made pecorino and ricotta cheese from the milk of their hardy mountain sheep.

Their peaceful life was disrupted by the war. Signora Lucia recalls seeing white bread, chewing gum (cingomma), and chocolate for the first time in her life when the American soldiers arrived. At that time, local bread was made from chestnut flour only, except in the short spring season for marzolo, a wheat planted in small amounts in March. And though there was wheat grain (farro, in fact), just a few kilometers away in the Garfagnana, that was too far: “You would have to take a mule over there, and it just wasn’t practical.”

Signora Eni, who lives forty kilometers from Piteglio, remembers that the Germans brought flour for her and her mother to make bread. If they brought five kilos of flour, they expected five kilos of bread in return. “But everyone knows that five kilos of flour makes more than five kilos of bread, because you add the weight of the water to it—so we always had some bread left over for ourselves.”

The daily food was necci, a type of crêpe made with chestnut flour. Signore Lucia and Eni may be the last two women who still make them in the traditional way on stone disks heated in a fireplace, though one man has taken it upon himself to carry the tradition on.

Sauro Petroni was born in Colognora in 1957. In his life, he has seen many changes in the way people eat and how food is handled. The traditional process of working with chestnuts has become mechanized and distant. To hear him reminisce about his childhood with his neighbor Signora Eni, you might think that much of the past was spent working with the chestnuts and dancing. “We danced a lot,” Signora Eni says and smiles, “and when my husband got tired, I still danced with my friends.” It was a good release from the hard work.

In the summer, the women wove bags of hemp to be used for gathering the chestnuts. Supplies were procured from the Pescia market, fifteen kilometers distant, and bartered for with chestnut products or the money earned by the men working in the paper mills. In the late summer, using a scythe, the men would prune the trees and clean the forest floor to prepare for the harvest of the nuts, which took place in October. Leaves would also be gathered and dried for later use in making necci in the winter.

After the backbreaking work of gathering the nuts from the ground, the chestnuts were taken to dry in the metato, a stone-walled room or small building with two levels, typically with a roof made of chestnut beams and with thin strips of chestnut wood dividing the two rooms. Inside smoldered a small, slow fire of chestnut husks saved from previous harvests. The fire was kept stoked for two to three months, and as the chestnuts dried on the upper floor, they would shrink inside the shell, making it easy to remove the shell. At this point, the nuts were taken to the miller, who ground them with millstones to a fine flour.

Sauro has become an expert necci maker under Signora Eni’s tutelage. He lights a fire in his hearth with small pieces of dry wood—not chestnut wood, however, as he needs a fast, hot fire. Next to the fireplace is a wooden tower, the reggipiastre, that holds the testi, round stones about six inches in diameter and an inch thick. These stones are put over the fire to heat, held by two horizontal metal rods. While the stones are heating, Sauro blends the chestnut flour with water in a wooden bowl to a paste the consistency of thick pancake batter. Signora Eni recommends a tiny pinch of salt in a year when the chestnuts are not as sweet as usual. “Too much salt lifts the sweetness, but when the chestnut flour isn’t so sweet, you need it.”

When Sauro is ready to make the necci, he puts the first heated stone back in its tower and places a chestnut leaf on the stone. In the summer, the necci are made with fresh chestnut leaves; in the winter, the dried leaves are soaked in water for a few hours to soften them, then patted dry. A large spoonful of the batter is placed directly on the leaf and covered with another leaf. At once, Sauro places another hot stone on top and repeats the process until the stones are stacked in a tower with the necci in between. After a few minutes, the necci have cooked and the leaves are peeled off. Their sweet smell is redolent of the forest, and when the crêpes are wrapped around fresh ricotta cheese, the taste is sublime.

Today in the Apennines, many people still make necci over a fire using testi di ferro, long-handled metal disks oiled with a piece of pork fat, but they are also made in a nonstick pan on the stove. Instructions for making necci on the stovetop can be found here.

Throughout these beautiful mountains, in view of the Apuan peaks that hold precious marble quarries, there are many interpretations of hearth breads and their variations. Some use chestnut flour, while others use wheat or corn. In the far northwest part of Tuscany, in an area called Lunigiana, the specialty is testaroli, a wheat flour crêpe cooked on a flat terra-cotta or iron pan called a testo; the cooked testarolo is cut into strips, then boiled, and served as a pasta. Besides necci and breads, dishes using chestnuts and chestnut flour are numerous and are still an essential part of the mountain table: castagnaccio, a dense pudding-like cake seasoned with rosemary and pine nuts; mondine, fresh roasted chestnuts; ballocciori, dried chestnuts soaked in milk overnight, then boiled with bay leaves and wild fennel for two hours (locally called tullore); vinata, a kind of polenta made with watered-down wine pressings and chestnut flour; and finally polenta. Chestnut polenta was eaten every day during hard times, as Signora Eni remembers: “Polenta at night and polenta the next morning for breakfast.”

ANTICO MOLINO DI SOTTO

In the past, each community in Italy had its own grain mill. In the village of Pieve Fosciana in the Garfagnana, the Molino di Sotto, or lower mill, was built in the 1700s by the municipality. At the time, there were two mills, one above (sopra), and one below (sotto). The upper mill was turned into accommodations for the millers. Since the early 1800s, four generations of the Regoli family have operated the mill, starting with Regolo Regoli, the great-grandfather of Ercolano, the current miller, who has worked in the mill since he was fifteen years old.

The current mill has four grinding stones: two arenaria for chestnuts and two focaia for corn and farro. The wheels are powered by a strong stream and fitted with wooden paddles that can be regulated to control the amount of water entering the mill, and therefore the speed of the grinding wheel.

First, the grains are dried; the chaff is then removed by use of the ventola, the same hand-cranked tool used one hundred years ago. The cleaned grain is then stored until ready to grind. When an order comes in for freshly ground meal, Ercolano’s wife, Maria Assunta Raffaelle, spreads the grains out on a large piece of fabric under the sun to eliminate any moisture.

La Garfagnana

A TRADITION OF CORN AND FARRO

Working our way through the mountain passes, westward-bound toward the sea, we pass through the Garfagnana, a zone unique for the richness of its food. One of the products that thrives here is called formenton di otto file, a red or yellow corn with eight rows of kernels, similar to the Indian corn of the United States. Corn in the Americas is one of the most manipulated foods in the world. What we find in the little valley of the Serchio River of the Garfagnana, and in a few other areas of northern Italy, is probably very much like the original corn that arrived from Mexico in the 1500s. This type of corn produces only 12 percent of the yield of today’s hybridized corn crops, which have been modified to have a higher yield. The aroma and flavor of the freshly ground formenton is rich with the essence of corn, unlike the finely machine-ground degerminated cornmeal found in supermarkets today.

Formenton is not a sweet corn to be eaten fresh; instead it is a field corn that is dried and stone ground to make a number of dishes, especially polenta. Corn is not indigenous to Italy, and even though chestnut flour polenta preceded corn polenta by centuries, corn polenta has become iconic in Italian cuisine. Other dishes are made as well, including mana fregoli, a creamy cooked cornmeal served with milk or cream for breakfast; frittele, or cornmeal fritters; cookies; and vinata, made with wine pressings.

Every step of the formenton production process is organic and hands on. The corn is air-dried, the cobs are degrained by hand, and the grain is stone ground slowly with a water-driven mill so that the grain doesn’t heat up, which guards both flavor and nutrition.

The Garfagnana is also famous for farro, an ancient strain of wheat, Triticum dicoccum, which at one time was near extinction. An important food source even in Etruscan times, this grain is high in protein and has a rich, nutty flavor. A typical meal in the past might have included farro boiled in milk or water with fennel, but today the most well-known dishes are zuppa di farro, a soup made with white beans and sometimes potatoes, and insalata di farro, a salad of farro and garden vegetables. In Garfagnana, farro is also used to make bread, pasta, beer, and even necci.

Pozzi di Pietrasanta

BETWEEN THE MOUNTAINS AND THE SEA

The drive down to the Ligurian Sea is stunningly beautiful. The road parallels the Via del Sale, the Salt Road, once a simple path for people coming to trade salt for chestnut flour. Many of the villages here have been nearly abandoned as people have sought less difficult lives and work in the cities. The visitor can sense an eerie presence of the not-so-long-ago war that devastated the simple quality of life in this area, which became the linea gotica (the Gothic Line), the front lines of the last battles of World War II.

Pietrasanta is at the foot of the Apuane Alps, in the center of coastal Versilia. When I asked if people with access to the riches of the sea fared better than others during the war, Ilvana Corsi Tognocchi, born in 1925, straightened me out right away: “We were forbidden to go to the water or out in boats for military security reasons. The best we could do was an occasional bucket of sea water to boil down for the salt.”

Signora Ilvana’s cousin Ivano Leonardi (born in 1934) was just ten years old during the war, but it left him with enduring memories. “The Nazis were encamped at a neighbor’s farm. They took a walk every night past our door and asked for a glass of wine in trade for cigarettes. We had to sip the wine first to show that it hadn’t been poisoned.” Ivano’s wife, Renza del Bianco (born in 1938), was just a child, but she remembers that the Germans slaughtered a cow and left the head behind: “We were hungry at home; I started dragging the head down the road, and a couple of big boys tried to take it. A German officer saw what was happening and ran them off. I made it home with the head, and my mother made soup.”

Signora Ilvana’s father was a butcher, but they rarely had more than a bit of meat to flavor their soup. “I remember we first ate polenta with plenty of olive oil and Pecorino cheese . . . then we ate it with just oil . . . and then just polenta, sometimes cooked in milk for the kids. Polenta. Polenta every day. We had to work all day to get our daily ration of two hundred grams of bread,” she said. “We ate carob beans . . . horse food! I remember eating spaghetti and beans a lot. My mother told me to be thrifty with the oil. I had to drizzle it on sparingly in a figure eight instead of the usual amount.” They were creative, using bossole, or empty bomb casings, for cooking pots and secretly burying demijohns of grain to hide it. Some demijohns had to be left out to avoid suspicion. “ The Germans didn’t like corn. We would fill the demijohns with grain, then put some corn on top to make it appear as if it were full of corn.”

Signora Ilvana’s good friend Diana Menchini Puccetti, born in 1922, vividly remembers the Nazi presence. She was frequently asked to bring grapes from her family’s small vineyard to the German officers. One day, she was given two hundred lire for the grapes, and she ran all the way home to give it to her mother. “The Nazis were printing money, but it was a precious amount all the same. The officer was so kind! Then, a few days later, we heard about the strage, the massacre, at Sant’ Anna di Stazzema, ten kilometers away, that left the entire village dead.”

Signora Diana said, “We made wine with our grapes. I remember harvesting them in a heavy wooden container, the bigoncia, which I carried on my back. Or, we carried the grapes on our heads, balanced on the cerdine, a rag twisted in a circle to balance the basket better. When the wine started to ferment, the smell would draw the partisans out of the hills, and we would give them wine and food.” They saved the seeds from the pressings, and roasted and ground them to make a hot drink.

Ivano recalls the day Pietrasanta was liberated, September 19, 1944. When the church bells began pealing to announce the liberation, Ivano and many members of his family had been in hiding in a narrow space behind a wall in the cantina for five days, surviving on bread and dried chestnuts. The light of day was a most welcome sight.

Viareggio

CITY BY THE SEA

Farther down the coast of Versilia is the quaint seaside city of Viareggio, with a population of about sixty thousand. The city took a severe beating in the war, and residents had great difficulty obtaining food. Maria Aurelia Oriente (born in 1915), whose nickname is Marelia, was a young mother at the time. Her husband was a brave underwater diver for the Italian military. Left alone in her apartment in the city, she didn’t have the foraging resources of those in the mountains or countryside. She did have peas. “We ate peas every day; they were part of our ration, and we had to make do with them. I invented a dish with eggs and peas, just to have something different; peas with an egg cracked in them and baked.”

If I could use only one word to describe Signora Marelia, it would be alive. At ninety-five, her joy in life belies the hardships she suffered: “We had nothing. No sugar, very little oil. My mother would dip the anchovies in bread crumbs twice to make them more filling for us.” Sometimes she would go out to the nearby empty lots and gather crescione (watercress), rosemary and other herbs, and acorns to grind for flour. With the bread provided by the rationing, she made pancotto zuppa: bread soaked in water and simmered with garlic, tomato, and basil. “It was povera e buona, both poor and good.” In better times, she made lo sfritto, a Versilian version of soffritto with lardo (lard) or prosciutto, garlic, onion, and sage, which she mixed in with the minestra (soup).

Other mainstays were salted cod and dried cod, inexpensive sources of protein; sbroscia, a soup made with squash and borlotti beans; and intruglia, a creamy corn polenta made with red beans, cavolo nero, and broth. Today, clams are called vongole verace, true clams, because in those days dishes were made with vongole finte, fake clams made with pieces of potatoes.

Isola di Capraia

FORAGING THE LAND AND THE SEA

On most days, there is only one ferry from Livorno to the remote island of Capraia, located in the northern Tyrrhenian Sea, not far from Corsica. Rocky Capraia is one of the seven islands of the Tuscan Archipelago, which peaks at Cala Rossa, a 1,475-foot volcanic cone now filled with a small lake. Legend holds that when Venus came out of the sea, seven pearls came unstrung from her necklace and formed the islands. In fact, fifty thousand years ago the islands were part of the greater landmass of Italy. At the end of the Ice Age, the level of the sea rose, separating the seven high points and creating the islands of Gorgona, Capraia, Elba, Pianosa, Montecristo, Giglio, and Giannutri.

The Greeks were the first to discover the island, around 1000 b.c. They named it Aegylon, which means “place of the goats,” while the name Capraia, which sounds like capra (goat), is derived from Latin/Etruscan capraria, meaning “rocky,” calling up the land’s volcanic origins. The Phoenicians, Etruscans, and Romans followed with the first human settlements. The Saracen pirates that roamed the coastline and islands in search of goods and slaves challenged the early settlers. Eventually, the Romans subdued them, and in 67 b.c. assumed control of this important military and commerce stop. Even in the twentieth century, governance of the island was contested by Genoa and Pisa, with the final dominion going to Genoa, which established an agricultural penal colony that finally closed in 1986.

In 1996, the region of Tuscany designated sixty thousand hectares of the archipelago to be environmentally protected, the largest marine park in Europe. Today, Capraia has approximately 380 inhabitants living on a mere 11.4 square miles (19 square km). The oldest native resident of the island, the serene Signora Anna Bessi, was born here in 1925 and is the last person to speak the Capraian dialect. When I mentioned my interest in learning about what people ate in hard times, Signora Anna took on the same expression I had seen on others I had interviewed, a sweet, suffering look that says, “It was hard, but I am still here.” She remembers well the year 1943, when no one came or went from the island. “There were mines completely surrounding the island. The Germans put them there, and we couldn’t go out to fish for fear of setting one off. We lived completely off the land and the coastal fish that we could catch from the rocks, especially totani (squid), crab, urchins, octopus, and little mollusks.”

Once covered in lush woods like the mainland, today Capraia’s isolation in the salty sea has created a classic Mediterranean landscape with some oak, umbrella pines, wild oleander, and a few cork trees. The prevalent scrub is the aromatic mirto (myrtle), used to make a digestive liqueur, and corbezzolo (Arbutus unedo), from whose flowers a curative bitter honey is produced. Wild celery, wild artichokes, and a mythic herb called sammule, a wild garlic chive with a strongly pungent aroma, also grow here. The wild goats that roam the island today are called muflone (Ovis musimon), and were introduced from Sardinia and Corsica in the 1980s.

“We also set traps for wild rabbits,” Signora Anna remembers of the war years, “and we had some chickens. We grew beans and ceci [chickpeas], and saved the seeds to replant them. We collected many kinds of greens from the campo, including asparagus and the wild garlic that we used in a savory cake, in fritters, and in frittatas. Every house had a cistern to collect the rainwater for drinking and cooking, but sometimes we added seawater to give the cooked food some salty flavor.”

Naturally, the recipes were simple, and Signora Anna, spry and bright at eighty-five, thinks her youthful aspect may have something to do with her natural diet. The island itself sparkles with an organic glow, and its crystalline water and pure air can only be good for the health.

After 1943, the year of solitude, commerce returned, even though there were many skirmishes between the Germans and the Americans. Sometimes, the island changed hands daily. But at least there was some access to ingredients such as flour and sugar. One of the classic Capraianese dishes, feculina, in fact, is a sweet cake made with potato starch, sugar, eggs, lemon zest, and vanilla powder. “It has no leavening,” explains Signora Anna, “but the eggs are worked very hard—even the children had to take turns beating the eggs—and the cake rises very tall.”

Today, the cuisine has evolved, as has the population. Capraia has always been frequented by ships from the mainland, bringing new ingredients and new ideas. Nearby Corsica has had a strong influence on the cuisine, and even the dialect. With two-thirds of the island protected as a national park, there won’t be any danger of big changes. There is currently a small movement to bring back the more traditional dishes. The one island winery, La Piana, makes a stunning Aleatico, and another small farm produces organic honeys and jams.

Back to the mainland and heading south from Livorno, we arrive in the southern area of Tuscany called the Maremma. The Maremma exudes an untamed spirit, with its wild horses, butteri (cowboys), tales of pirates, flamingos, wild boar, and the amazing horned Maremmana cattle. The clustered hill towns and tiny fishing villages still seem untouched, and the seaside pristine, at least after the summer rush is over.

Pitigliano

TOLERANCE AND SURVIVAL

Arriving in Pitigliano from the coast, the first view of the hill town from the curve in the road by the sanctuary of the Madonna delle Grazie is breathtaking. The village, carved from a high outcropping of volcanic tufo, seems to hang suspended in an unending expanse of blue sky. Here in this southernmost part of Tuscany, Pitigliano’s roots are prehistoric. It has been home, through time, to the Etruscans, Romans, and the noble Aldobrandeschi family, whose tolerance created a refuge for Jews in medieval times.

During the Renaissance, the Orsini family built a palace here, anchored by a fortress that dates back to 862. They continued the Aldobrandeschi tradition of religious tolerance, making Pitigliano and some neighboring fiefdoms havens for Jews when, in 1555, the Papal State, just across the border in Lazio, placed restrictions on them. This, along with the Inquisition in Spain, and intolerance in other areas, increased the numbers of resident Jews in Pitigliano and its surroundings. This long history of rapport between Jewish and Christian residents gave the town its nickname, Piccola Gerusalemme, or Little Jerusalem.

In 1598, a Jewish synagogue was built in Pitigliano, but within a short time, Cosimo di Medici declared further restrictions on the Jews of Florence and Siena, and restrictions were initiated here as well. Jews were forced to wear a red badge and were shut in the ghetto at night; they were also restricted from property ownership and commerce, and were subjected to high taxes.

Not until the second half of the eighteenth century were many of these restrictions lifted throughout Tuscany by the relatively liberal Grand Dukes of Tuscany, Leopoldo and Ferdinando de' Medici. This liberal atmosphere changed again in 1938, when strict racial laws, le legge laziale, were instituted by Mussolini, who created a number of concentration camps in Italy for political prisoners, partisans, and Jews.

At that time, one of the residents was eight-year-old Elena Servi (born in 1930). She recalls, “In 1938, my father came home one day and told me that I could no longer go to the state school. I asked him what I had done wrong. My father, with his head bowed, told me I had not done anything wrong, but I could no longer go to school.”

Signora Elena remembers that many Jews left the town. “We began to feel that we were different, and rejected. It was especially difficult for my father, as he was very patriotic, decorated in the First World War.” After a few years, the persecution worsened, and at the urging of their Catholic friends, Elena Servi and her family fled Pitigliano on November 11, 1943. For the next eight months, local farmers and friends sheltered them. Signora Elena remembers, “The last three months we lived in a grotto, where a farmer took us under his protection. They brought us food, and some locals even came on foot from Pitigliano to see us.”

Many Jews were saved by their Christian neighbors, but at the end of the war, none remained in Pitigliano. A large group gathered in Florence, and there Signora Elena was able to resume her schooling. After she was married, she passed almost ten years in Israel, and then finally she returned to Pitigliano. Three Jews now reside in Pitigliano: Elena Servi, her son, Enrico, and her grandson, Massimo.

Among the other Pitigliano survivors was Azelio Servi, the former acting rabbi who settled in Florence after the war. He made an extraordinary effort to keep the synagogue alive, returning to hold services, until it collapsed in 1960. Azelio’s daughter Edda Servi Machlin (born in 1926), moved to the United States and authored several excellent books on Italian Jewish cuisine and memories of growing up in Pitigliano. There were seven branches of the Servi family, and quite probably Azelio and Edda are distant relations of Elena Servi.

Before her family was forced into hiding, their diet was typically simple, Signora Elena reports. “Our food was Italian, with the exception of the foods for religious celebrations. Of course we didn’t eat pork; we followed our dietary rules. Instead of flavoring foods with pork fat and lardo, we used olive oil, garlic, and onion. We ate a lot of beans and vegetables and baccalà [salted cod].” The Maremma is known for a simple soup called acquacotta, but Signora Elena remembers her mother’s zuppa di agnello, made with the neck bones of a lamb and vegetables and served over a slice of bread. “Sometimes my mother would put an egg in it like they do with acquacotta, but I didn’t like the egg very much. My father hated rice because he had eaten so much of it in his military service, but he adored what he called zuppeta, a slice of bread covered in vegetable broth and sprinkled with sheep’s milk cheese. One of my favorite dishes was tortelli filled with spinach and ricotta, with cheese and cinnamon on top.”

Until 1939, there was a community oven that was used only once a year, during the eight days of pesach (Passover), when the families ate unleavened pane azzimo, or matzo, made with just flour and water. The women worked at a stone bench, pinching the dough to create the lattice design. “My mother was creative; one of my favorite things was when she would soak pieces of the azzimo in milk or water for a day, then squeeze it somewhat dry. She added a few eggs and some salt and cooked it slowly with some oil over a low flame, then sprinkled it with sugar and cinnamon.” Sfratti, another sweet dish, was traditionally served for the Jewish New Year in Pitigliano.

Pitigliano celebrated a rebirth in 1990 when the restoration of the synagogue was completed. In 1996, Elena Servi, her sister, and her son created an association called La Piccola Gerusalemme, over which she still presides.

Florence

VICTORY GARDENS AND ROOFTOP CHICKENS

Miriam Serni Casalini (born 1928) is a poet, writer, and philosopher who grew up in Florence during the war, under circumstances much different from those who lived in the countryside. Most city people didn’t have the option of foraging for food or growing their own. “We had the fortune to have family in the countryside,” Signora Miriam told me. “My mother would ride eighteen kilometers and back on her bike twice a week to get bread from our family’s house in Greve.” The rationing was strictly controlled by the Vigili di Annona, governors of the food supply, who would stop citizens and search them. “It was risky for my mother,” she remembers, “but the 150 grams of bread per person per day allowed by the rationing didn’t go far. In any case, the bread they gave us was made of whole grains and seeds, heavy and dark. It might be more appreciated today, but we called it pigeon food. The tessera/carta annonaria [ration card] allowed a meager amount of bread, dried pasta, sugar, butter, cheese, and meat. Laborers who did heavy work got more; their tessera was a different color. Of course there was the black market . . .” However, black market salt from Volterra was full of pebbles: one of Signora Miriam’s jobs at home was to pick them out. Some peasant farmers came into the Sant’Ambrogio market and sold a few vegetables, and the fish seller roamed the streets carrying a giant yellow squash hollowed out and filled with fish, calling out his wares in a loud voice. She also recalls the buzzurro (chimney sweep) who sold polenta and ficattole, a fried bread snack.

Many people had orte di guerra, what we would call victory gardens, on the bank of the Arno River. Small pleasures included tondone a sorpresa, a flat bread Signora Miriam’s grandmother made on top of the stove. “We had gas, but my nonna preferred to use coal. The sorpresa, or surprise, in the tondone was a spoonful of jam, a real treat.” Signora Miriam had a neighbor with a pollaio, a chicken coop, on his rooftop terrace, so they were able to enjoy frittate often.

Meat was rare, and when it appeared it was usually a minor part of a dish. The classic Sunday lunch of stufato, braised or stewed meats, was a thing of the past. In fact, Signora Miriam remembers a rhyme from that time:

Lo stufato del Signor Pelliccia—tutti patate niente ciccia.

The stewed meats of Signor Pelliccia—all potatoes, no meat.

Her mother occasionally made lesso, boiled meats, on Sunday, and sometimes bracciole in umido, braised meat, but the main protein was what is called the quinto quarto, the fifth quarter (5/4), or offal. After the animal is quartered, these are the parts that remain: stomach, lungs, organs, and even the udder. Prepared properly, these meats are delicious. (See Trippa alla Fiorentina.)

Even in Florence, chestnuts figured prominently in the diet. The local rosticceria had castagnaccio, polenta dolce, and necci, all made with chestnut flour and water, with very little sugar, due to the sweetness of the chestnut flour. Signora Miriam’s favorite was pattona, a cross between castagnaccio and necci, topped with ricotta cheese. Even better were the carts at Carnevale, with schiacciata (a thin focaccia), bruscolata (salted pumpkin seeds), and lupini, large, yellow protein-rich legumes that lost favor after the war, as they really were associated with animal feed. Now, you often see them in markets next to candies and roasted nuts.

REBUILDING AND REEDUCATION

The end of the war was a relief, but it left behind major destruction and the need to rebuild not only buildings and infrastructures, but also the society itself. Under the Truman Doctrine, a number of humanitarian and relief efforts were funded by the United States, one of which was the Marshall Plan, also known as the European Recovery Program. In a speech given by George Marshall in 1947, he said, “It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health to the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is not directed against any country, but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.” Critics claim it was a move to fight communism, but regardless of the viewpoint, help was desperately needed and provided. The idea was to strengthen individual countries under their own governance. Grants and loans were given to industries to provide jobs, and other moneys went to agricultural rehabilitation, education, medical and sanitation needs, and to provide the basics of food and clothing to devastated countries.

Dr. Evelina Modigliani Rossi, born in 1917, created and managed one such program in Italy from 1950 to 1973. Having already earned a doctorate in agriculture at the Giuseppina Alfieri Cavour Women’s Farming and Domestic Science Institute, Signora Evelina recalls, “I replaced my father, who was serving in the war, as assistant professor at the Institute of Agronomy in Florence. I was very pleased when I was selected to administer a new program funded by the Marshall Plan to educate rural women.

“Many people have the misconception that all peasant women were expert at managing a household, preserving foods, and dealing with domestic medical situations. The fact is that life spans were shortened drastically by a lack of such knowledge, particularly with regard to sanitation and diet,” she explains. At the turn of the century, there were few schools for women, and most were not in the rural areas, which sorely needed them. Education under early Fascist rule had suffered, except education for the privileged. Some programs slowly grew outside the public school sector, led by traveling lecturers teaching new agricultural techniques, but these were designed for boys and young men.

By the early 1930s, the Fascists assigned itinerant educators to provide training in agricultural and domestic skills for rural women, with the goal of keeping families on the farm rather than moving to urban and industrial areas. Techniques such as beekeeping, animal husbandry, and silk farming were taught, with the goal of making women more efficient at home while not threatening the livelihood of men. The Fascist propaganda of the time celebrated women as “mothers of the nation and guardians of the rural world,” but they were, in fact, overworked and quite poor. World War II did not improve the situation.

Signora Evelina describes her rural education program: “We selected thirty women from deprived areas, brought them to Florence for a nine-month residential program, and then sent them home to share what they had learned with their peers. Under the Marshall Plan, I was brought to the United States for three months to study with home demonstration agents,” a program begun in the early 1900s in the States to help educate people on the farm. The program disseminated information about preserving foods through brining, canning, drying, and curing. Later, subjects such as sewing, nutrition, sanitation, and home nursing were introduced. Signora Evelina explains, “In Italy, the same program was used as a model to teach women horticulture, agriculture, healthful eating, first aid, food preservation, and the care of children.”

Montepulciano

BACK HOME IN THE TUSCAN HILLS

At my table, Virio says, “If my mother could see this meal, how I live, she wouldn’t believe it. Heat in every room. Running water, a soft bed, and all of this good food.”

Even when we experience changes in our lives with fluctuating economies and priorities, it’s important to remember how good our lives are, and to reflect on the simple pleasures.

One thing that impressed me about almost every person that I interviewed for this book was that even though they had lived through difficult times and sometimes unimaginable experiences, they remain positive and appreciative of the smallest things in their lives today.

Take joy in small pleasures and eat well.

The Recipes

Italy is made up of twenty regions that have been united for only the past 150 years. Each region has maintained a unique cultural and agricultural identity based on a specific climate, geography, economy, and history of foreign influence. Even within one region, especially one as large as Tuscany, there are many variations on a theme. When these recipes originated, travel between communities was limited, and dishes were developed largely in isolation. A dish from two different areas can have the same name, but be prepared in a very different way, or the same recipe may also have a different name. Farinata, for example, can be made with different flours (corn, chickpea, wheat, and so on), and it can be prepared in diverse modes. In Liguria, it is a thin cake made with chickpea flour and baked in a wood-burning oven; in Tuscany, that same dish is called cecina, or sometimes torta di ceci (chickpea cake). In the recipe here, it is a soup thickened with flour—in this case—corn flour.

Within a village there can be as many variations as there are cooks. Pappa al pomodoro is a good example. It is basically bread and tomatoes; however, one person toasts the bread and another uses dry bread. One crumbles the bread or uses bread crumbs, another chunks it, and someone else slices. For some people, it’s an after-school snack; for others, it’s a whole meal. I have selected my favorite way to make a recipe; you should adjust it and make it your own as well.

The bread used in these recipes should ideally be wood-fired saltless bread. Since that is hard to find outside Tuscany, I’ve given a recipe, but you can also use a country-style bread from your market or baker.

Appetizers were not necessarily part of the peasant table. What we enjoy as an appetizer today might have sufficed for an entire meal in the past. A crust of leftover bread was often topped with a salted anchovy or, as many people told me, the anchovy was passed around the table for each person to rub the bread with it for a bit of aroma. There is a phrase, pane e companatico, that means “bread and something to go with the bread.” Sometimes that “something” was more bread.

In the past, except for special occasions, meat was considered a condiment rather than a main course, and was used to flavor pastas, rice, or soups. The main focus was on grains and seasonal vegetables that could be cultivated or foraged. Soups and pastas were a means of using up leftover bits of food. When there was time, or the means to obtain it, game was part of the fare. Apart from the season when the animals were butchered, fresh pork and beef were rarely seen on the table. I have included several meat dishes because we have more access to meats, but also to illustrate how cooking methods can transform an economical cut of meat into something delectable.

Desserts were relegated to special occasions. Sugar was expensive, so any daily sweet was fruit or jams made from fruit. This may be one of the reasons Tuscany is not known for elaborate desserts. On holy days and for birthdays, the favorites were ciambellone, a simple cake; panforte and panettone; and a variety of cookies. Each area has a special cookie: Pisa makes the wafer-like brigidini, first created by nuns; from Prato come the cantucci, or biscotti di Prato; and in Siena, you find cavallucci and ricciarelli. Most of these cookies are quite hard and dry so that they will keep for a while; a nice glass of vin santo (sweet wine) or vin brulé (warmed wine) is perfect for dipping and softening them.

In any case, the following recipes are descendants of harder times. Now we have access to the basic ingredients that then were not always available, so I have updated the recipes to reflect that. We may use stock or wine instead of water for cooking, we can use more meat and a greater range of vegetables, and we probably have fewer people to feed, so our portion sizes are larger. The principles of an economic and flavorful kitchen are the same, however, starting with food in season.

Today, we see a renewed interest in seasonal and local foods, an ancient concept that is the basis of peasant cuisine. Eating foods produced close to home supports local farmers and producers, and lessens the economic and environmental impact of transporting food.

I hope that the recipes in this book, which were born in frugality and innovation, will help you to make use of your own local foods in season, allowing these ancient dishes to live again in your own kitchen.

ERBE E SOFFRITT O: SEASONINGS

Tuscan cooks have two fundamental seasonings: erbe aromatiche al sale, aromatic herbs with salt, and the vegetable mixture soffritto. Both mixtures are traditionally minced using a mezzaluna, a half-moon-shaped double knife.

ERBE AROMATICHE AL SALE:

AROMATIC HERBS MINCED WITH SALT

This handy blend sits by most Tuscan stoves, ready to be sprinkled over a roast or grilled vegetables, or to season a sauce. Each cook has his or her own combination of flavors: rosemary, thyme, parsley, and sage are some favorites. A handful of fresh herbs are minced with an equal amount of salt. The salt adds flavor, but it also draws the essential oils that are left on the cutting board back into the mixture. This blend is wonderful used fresh but will keep for several days; the salt preserves the herbs, drying them and concentrating the flavor.

SOFFRITTO:

CARROT, CELERY, AND ONION FOUNDATION

I call soffritto the holy trinity of the Tuscan kitchen, a finely chopped mixture of equal parts carrot, celery, and onion (the aromatic vegetables, or odori) that is cooked until golden in olive oil to become the foundation of most soups, sauces, and stews. As the onion cooks, the sugars start to caramelize, the carrot sweetens, and the celery releases its unique flavor. Cooks may have their own variations according to local tradition and personal choice; some may add pancetta or lardo, or vary the proportions of the vegetables.